Abstract

In recent years, the acceleration of climate change and the growing demand for higher-quality food to meet the needs of an expanding population have become pressing challenges. Nanotechnology has emerged as a promising tool in agriculture, particularly through the application of nanoparticles (NPs). Recent studies highlight their potential to enhance plant performance, improve resistance to environmental stresses, and act as eustressors—stimuli that activate beneficial adaptive responses. Nanoparticles have been shown to stimulate plant defense systems (elicitation), promote growth and productivity, and improve crop quality by modulating physiological and biochemical pathways. Their role in enhancing adaptive capacity under diverse stress conditions makes them valuable candidates for sustainable agricultural strategies. However, a critical knowledge gap remains: the definition of eustress dose intervals. Establishing these thresholds is essential for maximizing the positive effects of NPs while minimizing risks. Finally, the need to define safe eustress dose intervals is highlighted as a critical step toward maximizing agricultural benefits while minimizing ecological and health risks.

1. Introduction

In 2023, the world population was about 8 billion people, and it is expected to increase to almost 10 billion by 2050 [1]. This trend of population growth necessarily implies a higher demand for food production. Therefore, to ensure sufficient food production, agriculture faces several challenges. One of them is plant stress; defined as any unfavorable condition or substance that affects or blocks the metabolism, growth, and development of a plant [2]. Stress can arise from abiotic factors such as heat, salinity, drought, or nutrient deficiency, and from biotic factors such as pathogens and pests. The consequences include reduced germination, impaired development, and lower yields, representing a major challenge for global food security [3]. Not all stress responses are detrimental; a proposed subdivision of distinguished between “eustress” as agreeable or healthy or “distress” as disagreeable or pathogenic stress [4]. In this context, eustress increases an organism’s adaptive capacity [5].

An eustressor enhances plant performance by stimulating physiological responses that improve both production and quality. Eustressors are typically classified as physical, chemical, or biological in origin [6]. When applied at appropriate levels, they activate multiple physiological pathways, which may or may not include defense mechanisms. However, the outcome depends on the dose: exposure to the same factor can trigger either eustressing or distressing effects, a phenomenon known as hormesis [7,8]. Hormesis allows plants to develop a form of “stress memory,” preconditioning them to face dynamic environments more effectively [9]. For instance, zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles at low concentrations have been shown to enhance germination and photosynthetic performance in canola under salinity stress, while higher doses led to oxidative damage [10]. This highlights the critical importance of identifying safe and effective dose ranges of nanomaterials for agricultural use.

Nanotechnology (NT) is a promising area of research that opens pathways in several disciplines, such as medicine, pharmaceuticals, electronics, and agriculture [11]. The use of NT to formulate nano-inputs in agriculture offers the possibility of improving the use and efficiency of the used products [12]. NT offers options to maintain the sustainable development of agroecosystems through the use and application of nanomaterials (Singh [13]). In addition, the use of certain nanomaterials has shown significant potential in the promotion of plant growth and/or the induction of the defense system of various cultivated species [14].

Nanomaterials (NM) can be materials with at least one dimension smaller than 100 nanometers (nm) [15]. NM include nanoparticles (NPs) with a size range between 1 and 100 nm. They can be classified into different classes based on their properties, shapes, or nature; the different groups include metallic, metal oxide, and carbon-based NPs [16]. NPs possess unique physical and chemical properties due to their large surface area and nanoscale size [17]; these can cross-cellular barriers and show effects on living organisms [18]. In fact, some NPs have shown antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [19]. When NPs are applied to the plants, they can generate a positive, neutral, or negative response; the responses depend on several factors, some of which include the applied concentrations, the physicochemical properties of the NPs, and the plant species to which they are applied [20].

When NPs are exposed to plant cells, they are taken up by plasmodesmotic or endocytosis pathways and translocated by apoplastic and/or symplastic pathways generating effects in plant metabolism. If NPs are beneficial to plants, they increase photosynthetic rate, biomass, chlorophyll content, sugar content, osmolyte accumulation, nitrogen (N) metabolism, chlorophyll and protein content [18], root elongation, redox potential, plant growth, and development [21]. However, the latter is not always the case; the application of NPs to plants can generate abiotic stress, which induces the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [22]. ROS are oxygen-containing signaling molecules with a higher chemical reactivity than O2 [23]. These molecules are a by-product of normal cellular metabolism in plants; however, under stress conditions, the balance between their production and elimination is disturbed. Thus, under these conditions, ROS are able to rapidly inactivate enzymes, damage vital cellular organelles in plants, and destroy membranes by inducing the degradation of pigments, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that ultimately lead to cell death [24]. However, the reduction in damage generated by ROS production is associated with the amplification of the stress signal that activates the plant defense system [17], and thus the production of secondary metabolites.

Secondary metabolites—such as terpenoids, phenolics, alkaloids, and sulfur-containing compounds—are key to plant adaptation and human nutrition [25,26,27,28]. Their production is tightly regulated by environmental and genetic factors, and exposure to NPs has been shown to alter their biosynthesis [29]. Thus, the use of NPs as chemical eustressors represents an innovative and sustainable strategy not only to mitigate stress effects but also to enhance crop quality and nutraceutical value.

This review therefore focuses on the potential of nanoparticles as eustressors in plants. It synthesizes evidence of their effects on plant growth, stress tolerance, and metabolite production, while also addressing the importance of defining safe dose intervals and understanding environmental implications for broader agricultural adoption.

2. Literature Search Strategy

This review synthesizes recent advances on the effects of nanoparticles (NPs) in plants, with particular focus on yield, quality, and stress resilience. Special attention was given to studies evaluating the hormetic role of NPs as potential eustressors. A comprehensive literature search was performed across multiple scientific databases, including Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and ResearchGate chosen for their comprehensive coverage of agricultural, biological, and material science literature. To ensure relevance and novelty, the search was restricted to publications from 2017 to 2025, a period that reflects the surge in nanotechnology applications in agriculture. The following keywords and their combinations were applied: “nanoparticles,” “plants,” “crops,” “hormesis,” “green synthesis,” “eustress,” “distress,” “biotic,” “abiotic,” “dose–response,” “biostimulant,” “elicitor,” and “secondary metabolites.” Boolean operators (AND/OR) and truncations were used to maximize retrieval efficiency. Additionally, to synthesize information from the selected studies, the data extraction process contemplated key information points such as nanoparticles time of application (seed/seedling or plant live stage), plant stress conditions, nanoparticle type, plant species, doses applied, and their observed effects. Figure 1 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the selection of the material.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selected literature in this review.

3. Mechanisms of Nanoparticles-Mediated Eustress: From Priming to Stress Alleviation

Stress conditions impair germination, growth, and yield, and therefore represent a key bottleneck for sustainable agriculture. Nanoparticles (NPs) have been proposed as innovative tools to counteract these negative effects, either by directly priming plant responses or by enhancing nutrient and agrochemical delivery. Their effectiveness depends on the mode of application, which influences uptake, physiological response, and long-term impact.

3.1. Nanopriming (Seed and Seedling Priming)

Nanopriming involves exposing seeds or seedlings to NPs prior to germination, functioning as a controlled initial stressor that induces stress memory and cross-tolerance [30,31]. Selenium (Se) NPs improved tomato germination by 32.5%, total antioxidant capacity by 38.9%, and chlorophyll by 21% [32]. On the other hand, priming tomato seeds with 75 ppm Se NPs markedly improved shoot and root fresh weight (+11.2% and +13.9%), chlorophyll, antioxidative enzymes, reduced drought stress markers (H2O2, MDA), and enhanced redox balance and antioxidant metabolism [32,33]. Another study found seed priming with Se NPs boosted germination rate by ~16.6% at 10 ppm, but higher doses (50 ppm) suppressed germination, underscoring hormetic effects [34].

Other NPs, such as iron oxide (Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 NPs) enhanced maize drought tolerance, wheat mineral uptake (Fe, P, K), and strawberry seedling survival under water stress. These effects translated into greater plant growth, associated with improved photosynthetic performance mediated by Calvin cycle enzymes and increased nutrient availability (Fe and P) supplied by the NPs. Importantly, no toxic effects were observed, as indicated by stable malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and photosystem II (PSII) activity [35,36,37]. Furthermore, in drought-stressed wheat, nanopriming improves relative water content, osmolyte accumulation (proteins, proline, sugars), and antioxidant defenses, contributing to stress tolerance [38]. Magnesium oxide (MgO) NPs in mustard increased carotenoids, phenols, and flavonoids [39]. Phenols and flavonoids are associated with multiple protection modes ranging from toxicity and stress tolerance to signal transduction activities. Although phenolic compounds have little involvement in plant growth, they are important in how plants interact with their environment [40]. Calcium oxide (CaO) NPs improved canola germination by 30% and yield by 35% under drought [41].

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) seeds germinated and grown for 21 days in soil amended with CuO NPs exhibited significantly enhanced growth and nitrogen (N) assimilation at low doses. This improvement was reflected in the increased activities of N-associated enzymes and the accumulation of N compounds. Interestingly, while Cu content in plants remained unaffected, Cu accumulation in the soil increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner [42]. Size-dependent effects of CuO NPs further highlight their influence on nitrogen uptake efficiency in soybean [42,43]. Additionally, nanopriming with CuO NPs has been shown to boost plant resilience by activating stress-response pathways, improving seedling root development, germination, and tolerance to drought and [43].

However, studies with cuprous oxide nanoparticles (n Cu2O) in soybean reveal that high concentrations can induce adverse effects on photosynthesis, though the damage lessens as the plants mature. These treatments also elevated antioxidant enzyme levels and altered grain nutrition, reducing protein while modifying P, K, Mg, and Ca contents [44].

In a recent study, green Pd NPs applied to Pterocarpus santalinus L. seeds (an endangered species) induced variations in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), suggesting molecular alterations and potential mutations. At the same time, Pd NPs improved morphological traits, enhanced growth rate and chlorophyll content, reduced climate-related stress, and promoted greater stability of the plants in their natural [45]. In Abelmoschus esculentus, a vermicompost enriched with biogenically synthesized Cu/Ni/Co oxide nanoparticles (using Moringa oleifera extract) markedly improved seed germination (167%), germination velocity (67%), and vigor index (95%), while reducing mean germination time by 41% compared to controls; metal content remained below the World Health Organization threshold [46].

In rape seed (Brassica napus cv. Punjab canola), treatment with CaO NPs under drought stress significantly improved germination percentage and seedling fresh weight by 30% and 34%, respectively. Nanopriming also enhanced the number of leaves (16%), total chlorophyll content (28.9%), pods per branch (29.99%), seeds per pod (73.08%), 100-seed weight (35.13%), and overall yield (35.18%). Moreover, antioxidant enzyme activities increased, while stress indicators declined significantly [41].

Recent studies revealed that smaller-sized ZnO10 NPs enhance seed germination, metabolic activation, and antioxidative defense in A. tricolor: antioxidant enzymes increased significantly, malondialdehyde decreased up to 89.3% at 400 ppm, and phenolic/flavonoid contents rose considerably [47]. Moreover, machine learning analysis of multiple nanopriming treatments (including ZnO) in maize under salinity or combined heat-drought stress demonstrated elevated stress resistance indices and regulation of key metabolic pathways (amino acids, secondary metabolites, carbohydrates) [38]. On the other hand, a pioneering study applied Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles (GONPs) for priming soybean seeds to mitigate arsenic stress, demonstrating effective alleviation of arsenic toxicity and promoting plant safety under contaminated conditions [48].

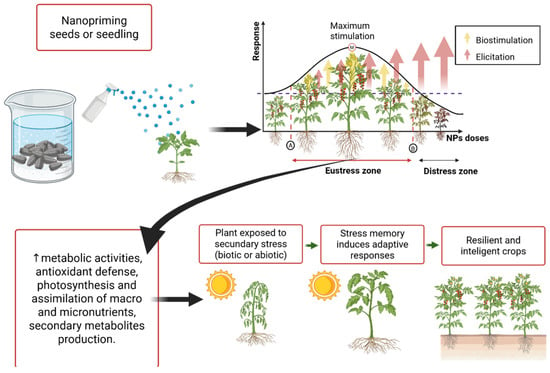

Figure 2 shows the demonstrated positive effects when nanopriming seeds/seedlings with doses within the eustress zone in a controlled primary stress environment, representing a potential and novel strategy to improve plant performance and resilience to stress due to seed priming—or exposing seeds/seedlings to controlled primary stress—can also confer benefits when plants later encounter secondary abiotic or biotic stresses, a phenomenon known as cross-stress tolerance. Such “rewired plants” with stress memory represent a promising strategy to stimulate adaptive responses, safeguard crop reproduction, and engineer climate-smart crops for the future [49]. Therefore, nanopriming can enhance seed vigor, germination, biomass, early growth, yield, photosynthetic performance, antioxidant defense, phytohormonal modulation, salinity tolerance, disease resistance, and mitigation of heavy-metal toxicity [50]. Consequently, further research is required to determine the most effective NP types and dosages, since depending on the concentration, NPs may act as stress promoters or inhibitors in plant systems [7,51].

Figure 2.

Nanopriming utilizing eustressic doses as a strategy to generate stress memory in order to improve plants’ performance and resilience to stress.

Several other examples of seed and seedling nanopriming are summarized in Table 1. The key findings from the studies include nanoparticle type and concentration, plant species, and the resulting eustress effects. Collectively, these findings suggest that NPs in an adequate dose can function as controlled primary eustressors, enhancing plants’ ability to cope more efficiently with future environmental challenges.

Table 1.

Nanoparticles applied on seeds or seedlings.

3.2. Nanoparticles as Abiotic/Biotic Stress Alleviators

Crop growth and yield are negatively impacted by increased abiotic/biotic stress in the agricultural sector due to increasing global warming and changing climatic patterns. The host plant’s machinery is exploited by stress, resulting in nutrient deprivation, increased ROS and disturbances in physiological, morphological, and molecular processes [66,67]. Nevertheless, different NPs used in plants previously subject to abiotic/biotic stress have shown potential as stress alleviators when used in eustressic doses benefiting mechanisms that promote growth, yield, the induction of the antioxidant system and secondary metabolites production contributing to plant resilience.

3.2.1. Growth and Yield Promoting of Plants

NPs can biostimulate plant growth and development at certain doses and inhibit these characteristics in others [68]. The effects will depend on several factors such as the concentration, sizes and types of NPs, crop species, phenological plant stages at the application moment [69], NPs’ physicochemical properties, factors such as the dopant and synthesis method, in addition to the interaction between those factors [70]. To illustrate the effects of NPs’ application in growth and yield, silicon (Si) NPs obtained from a green synthesis of rice husk, applied to eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) crops subjected to water stress. The highest dose used in the research (300 ppm) reduced the adverse effects on crop growth and yield and increased the content of Ca (53%), Mg (38%), K (63%), and Si (48%), suggesting other factors such as stress type instead of dose concentration would be influencing. In addition, a significant increase in plant growth and yield was detected compared to plants not treated with Si NPs [71]. Furthermore, foliar application of 50 ppm of Fe2O3 NPs to soybean (Glycine max) infested with Fusarium oxysporum significantly increased root biomass (54.28%) and chlorophyll a (31.6%), decreasing up when using 500 ppm, suggesting Fe2O3 NPs’ use at low doses as root rot mitigator utilizing multiple mechanisms including the increased levels of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and amino acid metabolites to provide energy for soybean response [72].

Moreover, the application of Si (2.5 mM) and Fe (25 ppm) NPs’ combination as stress alleviators in rice cultivated in lead (Pb)-polluted soil, significantly reduced the lethal impact of Pb on roots and shoots growth parameters, by increasing shoot length (40%), shoot fresh weight (48%), roots fresh weight (31%) and reduced the Pb contents in the upper part of plants by 27% [73]. Additionally, foliar application of Se NPs combined with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) induced significant improvements, enhancing yield stability in rice. The superior performance of this nanomaterial’s combination in rice was attributed to their complementary physiological roles and their synergistic interaction [74], prompting a combination of NM as a potential tool to enhance cultivar performance.

The positive effects of NPs have been observed in unstressed plants as well. In groundnut cultivars, the foliar application of MgO and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) NPs significantly enhanced N fixation and nutrient uptake [75]. Cysteine-coated Fe3O4 NPs applied in strawberry plants in low dose (0.06 ppm) generated a significant increase in yield, Fe content, and total soluble solids [76]. NPs also show potential eliciting Growth-Promoting Microorganisms (PGPMs); these microorganisms promote N fixation, phosphorus solubilization, production or regulation of phytohormones, and plant protection against biotic and abiotic stresses [77]. This latter asseveration was demonstrated when applying SiO2 NPs on Bacillus cereus-Amazcala subsequently applied to chili pepper plants (Capsicum annuum L.), stimulating positive effects in variables such as germination percentage, height, number of leaves and fruits, crop yield, and antioxidant activity. Additionally, gibberellins and phosphate’s solubilization increased significantly as a result of the previous microorganism’s NPs’ elicitation and before their application to plants [78]. The finding revealed that NPs applied in a controlled environment to PGPMs magnify their potential when subsequently applied to plants. It may be argued as another possible strategy to improve plants’ performance subjected to diverse scenarios reducing the delivery of NPs to the environment and consequently their unexpected effects in humans and other living organisms.

3.2.2. Induction of the Antioxidant System

In plants, it is a complex and multilevel network of the antioxidative system operating to counteract harmful reactive species and maintaining homeostasis within the cell [79]. Plants, being sessile, are continuously exposed to varietal environmental stressors, which consequently induce various bio-physiological changes generating oxidative stress, and is one of the undesirable consequences in plants triggered due to imbalance in their antioxidant defense system. Biochemical studies suggest that NPs are known to boost the capacity of antioxidant systems, thereby contributing to the tolerance of plants to oxidative stress. NPs increased antioxidant potential upregulation and improved expression of stress-related genes, which are crucial for stress resilience [80]. CuO NPs increased activities of peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, and plant phenol contents in unstressed chickpea plants [81]. Green silicon (Si) NPs applied to eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) crops subjected to water stress reduces lipid peroxidation of the membranes by activating antioxidants that promote the elimination of ROS, thus reducing the adverse effects on the crop [71]. Additionally, in tobacco plants, magnetite NPs trigger immunity by activating ROS production, which significantly increases peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) enzyme activity in addition to up-regulating resistance genes and participates in phyhormone synthesis [82], while Ag NPs’ application in a wheat cultivar stressed or unstressed by salinity activated the antioxidant system and promoted plant performance [83]. All changes in plants are mediated by changes in gene expression and proteomics, resulting in abiotic stress tolerance [22]. NPs mimic calcium ions (Ca2+) or signaling molecules in the cytosol, detected by Ca2+ binding proteins or other specific proteins. Signaling molecules increase gene expression, leading to enhanced stress tolerance [17] by up-regulating the expression of abiotic stress related genes [18]. NPs’ application effects, generating plant biostimulation and immune system activation, also display effects on gene expression such as AREB, SOS2, and DDF2 genes associated with salt stress tolerance [84]. Artemisia annua L. elicited with Fe3O4 NPs resulted in the activities of CAT, POD, SOD, and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) significantly increasing, and stimulating the overexpression of AaWRKY1, AaMYB2, CYP71A1, and HMGR genes, related to marked increase in secondary metabolite production [85]. This implies the need to further explore the effects of NPs acting as eustressors also affecting gene expression providing plants with increased stress tolerance.

Foliar application of Se NPs combined with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) significantly enhanced stress tolerance in rice. This combination reinforced plant defense mechanisms and optimized physiological processes, resulting in improved resilience and yield sustainability below saline stress [74]. A similar occurrence was observed applying Si and Fe NPs in rice cultivated in lead (Pb)-polluted soil, the activity of the antioxidant system incremented in CAT, POD, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and reduced glutathione (GSH) content. Both Si and Fe NPs can suppress oxidative stress and adjust the antioxidant defense system in plants by modulating the expression patterns of metal transporters, such as OsHMA9, OsLSi1, and OsIRT2. These results indicate that the combined use of Si and Fe NPs can mitigate the harmful effects of Pb exposure on rice plants. Si and Fe NPs can be deemed favorable, environmentally promising, and cost-effective for reducing Pb deadliness in rice crops and reclaiming Pb-polluted soils [73]. Foliar application of Fe2O3 NPs to soybean (Glycine max) infested with Fusarium oxysporum disease significantly increased SOD activity and GmPAL, suggesting that Fe2O3 NPs mitigate root rot through multiple mechanisms, including augmentation of antioxidant enzyme activity to mitigate disease-induced oxidative stress and the activation of relevant defense genes to enhance resistance [72].

3.2.3. Hormetic Effects in Secondary Metabolites (SM) Production

Nanoparticle multifunctionality (biostimulant, elicitor, or stress alleviator) has been exposed in different ways in this review. Plants submitted to stress enhance SM accumulation as a natural defense mechanism [86]. For instance, a maize cultivar treated with a foliar application of zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs increased SM such as flavonoid, phenols, anthocyanins, and ascorbic acid in plants unstressed or stressed by cadmium (Cd), enhancing tolerance to Cd in maize [87]. In banana plants exposed to cold stress treated with foliar applications of chitosan NPs, phenolic and carotenoids compounds increased in addition to reducing the adverse effects of cold stress [88]. Similar results were found when applied to biosynthetized Ag NPs in a tomato crop infected or not with Alternaria solani, where total phenols significantly increased in addition to enhanced plant resistance against biotic stress [89]. In another method, cysteine-coated Fe3O4 NPs applied in strawberry plants, generated a significant increase in anthocyanins, phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity [76].

However, the positive effects of NPs have been found even in previously unstressed plants. This is the case of silver (Ag) NPs applied in a tomato crop (5, 10, 15, 25, 50 ppm), where SM such as carotenoids (65%), flavonoids (58%), and alkaloids (67%) significantly increased between 5 and 10 ppm [90]. Parallel discoveries were reported with Artemisia annua L. treated with Fe3O4 NPs, which significantly increased artemisinin levels (a pharmaceutically important secondary metabolite) by 98.5%, 76.3%, and 77% using 50, 100, and 200 ppm, respectively [85]. These enhancements in SM production may be related to plants’ possible interpretation of NPs as stress factors resulting in the increment of SM production for their own protection. The maximal SM production for both detected among low doses intervals, pointing out the importance of determination of safe eustressic intervals of application. Without doubt, plant elicitation with NPs is a remarkable approach proposal for obtaining phytochemicals to be utilized in various sectors including food, medicines, cosmetics, or agriculture, but it is essential to understand the interrelationships between NPs and plant systems [91].

Table 2 and Table 3 summarize diverse other examples of nanoparticles applied or not as plant abiotic/biotic alleviators, respectively. The key findings from the studies include nanoparticle type and concentration, plant species, and the resulting effects. Collectively, these findings suggest that NPs may act as multifunctional tools in plants, enhancing plants’ competence to cope more efficiently with stress situations’ activating mechanisms that generate improvement in growth, yield, antioxidant activity, and secondary metabolites production.

Table 2.

Nanoparticles applied either under abiotic stress or not.

3.2.4. Disease Suppression

Disease suppression is a benefit of NPs used in crops to alleviate stress, for instance, ZnO and CuO nanoparticles showed significant antifungal activity when applied to potato plants against Phytoptora infestans, demonstrating control efficacy of 70.64 and 68.8% for each [101]. While CuO, TiO2, and silica dioxide (SiO2) NPs applied to control root rot and wilt in chickpea, caused by, respectively, Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris., indicated that CuO NPs (40 ppm) achieved a 61% reduction for Rhizoctonia rot and 65% for Fusarium wilt [81]. In a recent study, titanium dioxide (TiO2) NPs applied to wheat reduced the severity of the blur caused by the pathogen Bipolaris sorokiniana. Moreover, the application of Ag NPs obtained from moringa leaves extract reduced 86.29% disease severity caused by Clavibacter michiganensis in a tomato crop acting as biostimulant and protector for plants [102]. Foliar application of Fe2O3 NPs to soybean (Glycine max) infested with Fusarium oxysporum disease indices significantly reduced (60.29%) [72]. However, Si NPs used in a rice crop infected by Magnaporthe oryzae, showed effective application regardless of the doses, the plant elicited organs determined the effectiveness, those applied by the root were preferred by the plant, since the same dose in a foliar application showed signs of phytotoxicity and caused anomalous behavior of the crop, resulting in gene expression associated with weakened resistance that aggravates the disease [103]. These findings underscore the significant potential of NPs as a disease suppression strategy promoting environmentally sustainable agriculture as well as highlighting the importance to standardize safe eustressic doses intervals, organs of application and the application method preferred by the crop since it may affect the way plants cope stress.

Table 3.

Nanoparticles applied in crops either under or not biotic stress.

Table 3.

Nanoparticles applied in crops either under or not biotic stress.

| Nanoparticle and Concentration Applied | Species | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu coated with polyethylene glycol 8000 and ZnO doped with Cu with diethylene glycol (50, 100, 200, 300, 400 μg/mL) and (200, 300, 400, 500, 600 μg/mL) | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) inoculated with S. sclerotiorum or M. javanica. | ↑ antioxidant activity and total phenols. ↓ severity index of S. sclerotiorum, galls and females per gram of root of M. javanica, infestation by fungi and nematodes. | [104] |

| TiO2 * (20, 40, 60, 80 ppm) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) infected with Puccinia striiformis f. sp. Tritici | ↑ SOD, POD, CAT, proline. ↓ total phenols and flavonoids, incidence of disease depending on doses. | [105] |

| TiO2 * (20, 40, 60, 80 ppm) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) infected with Bipolaris sorokiniana | ↑ fresh and dry plant weight, grain yield (weight and number of grains per spike) and total protein, disease resistance. ↓ soluble sugars, phenols and flavonoids, severity disease. | [106] |

| Ag * (25, 50, 75, 100 ppm) | Rice (Oryza sativa L.) infected with Aspergillus flavus | ↑ leaf area, number of leaves, fresh and dry weight. ↓ aflatoxin production. | [107] |

| Iron oxide * (Fe3O4) (0.01, 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15 μg/mL) | Tomato (Solanum Licopersicum L.) infected with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici. | ↑ PAL, POD, PPO, total phenols, PR-2, PAL, POD, PPO gene expression, plant growth (height, root and shoot length), fresh and dry weight. ↓ F. oxysporum growth and disease severity and incidence. | [108] |

| Chitosan * (1.0%) | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) infected with Fusarium solani | ↑ total phenols, flavonoids, MDA, CAT, SOD, APX, height, root length, fresh and dry weight, leaf number, total chlorophyll, transcription factors WRKY4, WRKY31 and WRKY37, as well as the other three defense-related genes: glucanase A, defensin and chitinase. ↓ protein and disease severity. | [109] |

| Si * (50, 100, 150, and 200 ppm) | Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) infected with Meloidogyne incognita | ↑ mean nematode mortality, fresh and dry weight, leaf number, stem diameter, and plant height. ↓ emerged juvenile population and final population of the nematode, number of galls and masses on plants. | [110] |

| Si (10, 100, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000 ppm) | Rice (Oryza sativa L.) infected with Magnaporthe oryzae or under water stress. | ↑ inhibition of fungal growth, gene expression related to the AS pathway: PR1A, PR1B, PR5, PR8, PR10 and PAD, root length. ↓ diseased leaf area, relative fungal growth. | [103] |

| Carbon nanotube (100 ppm) | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) infected with Alternaria solani | ↑ chlorophyll A, total chlorophyll, WUE, GPX, dry weight, fruit number and yield. ↓ disease incidence and severity. | [111] |

| Cu2O (100 µg/L) | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) infected with F. solani | ↑ CAT, POD, PPO, transcription of PR-1 and LOX-1 genes associated with defense, total chlorophyll, root length, fresh and dry weight, yield increase. | [112] |

| ZnO (50,100,150, 200 mM) | Jalapeño pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) infected or not with the pepper huasteco yellow vein virus. | ↑ weight, height and diameter of fruit, POD and SOD activity. ↓ viral severity, viral levels, infection symptoms, CAT and PAL activity. | [113] |

Own elaboration. * NPs from green synthesis. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), malondialdehyde (MDA), phenylalanine ammonium lyase (PAL), water use efficiency (WUE), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), Salicylic acid (AS), ↑ (increase), ↓ (decrease).

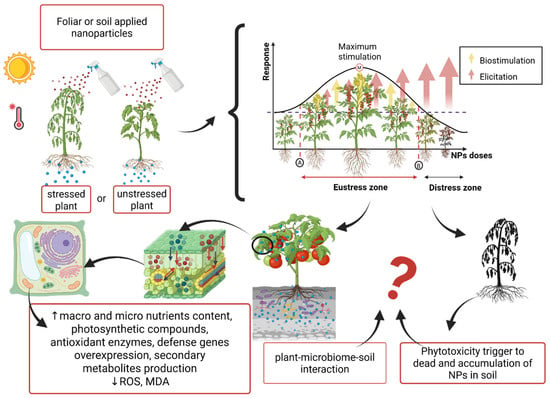

In spite of nanoparticles showing potential acting as stress alleviators displaying a series of positive effects in plants improving yield, growth, nutrient absorption, and even a reduction in the accumulation of toxic elements in tissues, most of these studies are still in the laboratory stage. The increased applicability of nanoparticles is of concern due to their unexpected effects on the environment, as well as their accumulation in edible plant organs, which pose serious risks of bioaccumulation in the food chain [80]. Figure 3 is a scheme of some positive and negative reported effects of NPs applied in plants when using doses within the eustress zone and the devastating effects when using doses within the distress zone. Additionally, it exhibits the unknown respect to their undetermined or unknown environmental and other living organisms’ effects.

Figure 3.

Expected effects of nanoparticles in plants using hormetic doses. ROS (reactive oxygen species), MDA (malondialdehyde).

4. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the promising potential of nanoparticles (NPs) as eustressors in agriculture, several challenges must be addressed before their safe and large-scale application can be carried out. These challenges extend beyond their direct effects on plants to encompass ecological, technological, and regulatory dimensions.

One of the most pressing concerns is the persistence and accumulation of NPs in soil and water systems. Their behavior depends on physicochemical properties such as size, coating, and composition, which determine transformations that may modify reactivity and toxicity. For instance, CuO NPs can enhance nitrogen assimilation in soybean at low doses but simultaneously pose a risk of long-term copper buildup in soils [42]. Likewise, ZnO and TiO2 NPs have been associated with reduced microbial diversity in the rhizosphere, potentially compromising soil fertility and ecosystem functioning [114].

In addition, NPs interact not only with plants but also with their associated microbiota, producing both beneficial and detrimental outcomes. Positive effects have been reported, such as Fe3O4 NPs enhancing beneficial rhizobacteria linked to ryegrass [115]. Conversely, other studies indicate that ZnO NPs can suppress microbial biomass and enzymatic activity, thereby impairing soil health [116].

The application of NPs in food crops further raises concerns about residues in edible tissues and potential implications for human health. Although green-synthesized NPs, such as Si or Se, tend to exhibit lower toxicity compared with chemically produced ones, standardized frameworks for assessing NP residues in food chains remain lacking. Current regulatory guidelines are fragmented, and harmonized protocols for the safe deployment of nanotechnology in agriculture are yet to be established.

A central challenge lies in defining hormetic thresholds that distinguish beneficial from harmful effects. Reported dose ranges are often inconsistent, varying according to plant species, growth stage, NP type, and environmental conditions. For example, Se NPs have been shown to improve tomato germination at 10 ppm but reduce biomass at 50 ppm [32].

Finally, the green synthesis of NPs—using plant extracts, algae, or microbial systems—emerges as a sustainable alternative that reduces environmental risks. Biologically derived NPs often demonstrate greater biocompatibility and may integrate more safely into agroecosystems. Nonetheless, issues related to scalability, reproducibility, and standardization of green synthesis methods remain insufficiently explored.

5. Concluding Remarks

Nanoparticles (NPs) have emerged as innovative tools in agriculture, acting as eustressors that can enhance plant growth, stress resilience, and nutritional quality. Evidence indicates that at low or optimal concentrations, NPs stimulate photosynthesis, activate antioxidant pathways, and promote the synthesis of secondary metabolites, thereby improving crop yield and nutraceutical value. Among the strategies explored, nanopriming and foliar application demonstrate the most substantial potential for practical implementation, whereas incorporation into nutrient media and the use of NP-based carriers remain promising but more complex approaches that require further biosafety evaluation.

A central mechanism underlying NPs action is hormesis: an effect that is positive or negative depending on the type and concentration of NPs, plant species, period exposition, etc. This biphasic effect highlights the need to define safe eustress dose ranges tailored to specific crops, environments, and nanoparticle types.

Despite encouraging outcomes, critical challenges remain. Key priorities include elucidating the environmental fate of NPs, clarifying their interactions with plant–microbiome systems, and establishing robust regulatory frameworks to safeguard food safety and ecological integrity. Emerging solutions—such as green synthesis of NPs and predictive tools including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and dose–response modeling— are expected to be integrated to support hormetic studies to establish eustress zones for crop production systems, offering safer pathways toward more sustainable agriculture implementation.

In conclusion, NPs represent a promising frontier for climate-smart and nutritionally enriched agriculture. Their successful application will rely on interdisciplinary research that balances productivity gains with ecological stewardship, ensuring that nanotechnology contributes meaningfully to global food security and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, S.R.-J.; writing—review and editing, A.A.F.-P., K.E.-E., R.G.G.-G. and H.A.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are pleased to acknowledge and thank Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) for the postgraduate scholarship of Susana Rodríguez Jurado. Moreover, authors would like to thank FONFIVE FIN202420 and FONFIVE FIN202413.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NM | Nanomaterials |

| NT | Nanotechnology |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| PSI | Photosystem I |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| APX | Ascorbate Peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione Reductase |

| GPX | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| PPO | Polyphenol Oxidase |

| PAL | Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase |

| GPOX | Guaiacol Peroxidase |

| LAA | L-Ascorbic Acid |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| IBA | Indole-3-Butyric Acid |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| AsA | Ascorbic Acid |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| DSI | Disease Severity Index |

| DON | Deoxynivalenol |

| REL | Relative Electrolyte Leakage |

| SPAD | Soil–Plant Analysis Development (Chlorophyll Index) |

| CHS | Chalcone Synthase |

| Mn-SOD | Manganese Superoxide Dismutase |

| PR | Pathogenesis-Related proteins |

| WUE | Water Use Efficiency |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid cycle (Krebs cycle) |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Pb | Lead |

| K | Potassium |

| Na | Sodium |

| Ca | Calcium |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| Fe | Iron |

| Zn | Zinc |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Cl | Chlorine |

| P | Phosphorus |

| Si | Silicon |

| Cu | Copper |

| Ag | Silver |

| Au | Gold |

| Se | Selenium |

| TiO2 | Titanium Dioxide |

| Fe2O3 | Iron (III) Oxide |

| Fe3O4 | Magnetite (Iron Oxide) |

| CaO | Calcium Oxide |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

| CuO | Copper (II) Oxide |

| Cu2O | Cuprous Oxide |

| GONPs | Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles |

| MWCNTs | Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes |

References

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World Population Prospects. 2022, United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024. Online Edition. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/downloads?folder=Standard%20Projections&group=Most%20used (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Vegetation stress: An introduction to the stress concept in plants. Plant Physiol. 1996, 148, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Devireddy, A.R.; Sengupta, S.; Azad, R.K.; Mittler, R. Systemic signaling during abiotic stress combination in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13810–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selye, H. Forty years of stress research: Principal remaining problems and misconceptions. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1976, 115, 53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kupriyanov, R.; Zhdanov, R. The eustress concept: Problems and outlooks. World J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Hernández, M.C.; Parola-Contreras, I.; Montoya-Gómez, L.M.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Schwarz, D.; Guevara-González, R.G. Eustressors: Chemical and physical stress factors used to enhance vegetables production. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 250, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez-Mendoza, P.L.; Rico-Chávez, A.K.; Ferrusquía-Jimenez, N.I.; Carbajal-Valenzuela, I.A.; Villagómez-Aranda, A.L.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R.G. Plant hormesis: Revising of the concepts of biostimulation, elicitation and their application in a sustainable agricultural production. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. A method for assessing the frequency of hormetic trade-offs in plants. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Hormesis in plants: Its common occurrence across stresses. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2022, 30, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Badri, A.M.; Batool, M.; Mohamed, I.A.; Khatab, A.; Sherif, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Modulation of salinity impact on early seedling stage via nano-priming application of zinc oxide on rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Tripathi, D.K.; Yadav, S.; Chauhan, D.K.; Zivcak, M.; Ghorbanpour, M.; El-Sheery, N.I.; Brestic, M. Application of silicon nanoparticles in agriculture. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira-Saldivar, R.H.; Mendez-Arguello, B.; De los Santos-Villarreal, G.; Vera-Reyes, I. Potencial de la nanotecnología en la agricultura. Acta Univ. 2018, 28, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Handa, R.; Manchanda, G. Nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture: An emerging opportunity. J. Control Release 2021, 329, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-López, E.; Palos-Barba, V.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Vázquez-Hernández, M.C.; White, J.C.; Nava-Mendoza, R.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R.G. Nanostructured mesoporous silica materials induce hormesis on chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) under greenhouse conditions. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsdale, A.C.; Müllen, K. The chemistry of organic nanomaterials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5592–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramo, L.A.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Guevara, R.; Mendoza, S.; Esquivel, K. Nanoparticles in Agroindustry: Applications, Toxicity, Challenges, and Trends. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K.; AlMutairi, K.A.; Siddiqui, Z.H. Role of nanomaterials in plants under challenging environments. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Tiwari, S.; Pandey, J.; Lata, C.; Singh, I.K. Role of nanoparticles in crop improvement and abiotic stress management. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 337, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, R.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, P.A.; Pandey, A.K. Nanoparticles as modulators of oxidative stress. Nanotechnol. Mod. Anim. Biotechnol. 2019, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqeel, U.; Aflab, T.; Khan, M.M.A.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.N. A comprehensive review of impacts of diverse nanoparticles on growth, development and physiological adjustments in plants under changing environment. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Saman, H.S.; Palma, J.M.; Corpas, F.J. Influence of metallic, metallic oxide, and organic nanoparticles on plant physiology. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Labrada, F.; Hernández-Hernández, H.; López-Pérez, M.C.; González-Morales, S.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Nanoparticles in plants: Morphophysiological, biochemical, and molecular responses. In Plant Life Under Changing Environment; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 289–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszczak, C.; Carmody, M.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppanapandian, T.; Moon, J.C.; Kim, C.; Manoharan, K.; Kim, W. Reactive oxygen species in plants: Their generation, signal transduction, and scavenging mechanisms. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 709–725. [Google Scholar]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. A Comprehensive Review on the Biological, Agricultural and Pharmaceutical Properties of Secondary Metabolites Based-Plant Origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, R.; Shen, C. Environmental and Genetic Factors Involved in Plant Protection-Associated Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis Pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 877304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barket, A. Salicylic acid: An efficient elicitor of secondary metabolite production in plants. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, G.; Berni, R.; Muñoz-Sanchez, J.A.; Apone, F.; Abdel-Salam, E.M.; Qahtan, A.A.; Alatar, A.A.; Cantini, C.; Cai, G.; Hausman, J.F.; et al. Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Examples, Tips and Suggestions for Biotechnologists. Genes 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marslin, G.; Sheeba, C.J.; Franklin, G. Nanoparticles Alter Secondary Metabolism in Plants via ROS Burst. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Fu, C.; Li, J.; Tao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Khan, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Seed nanopriming: How do nanomaterials improve seed tolerance to salinity and drought? Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisha, K.C.; Vijayakumari, K.; Puthur, J.T. Seed priming for abiotic stress tolerance: An overview. Acta Physiol. Plant 2013, 35, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Locascio, E.; Valenzuela, E.I.; Cervantes-Avilés, P. Impact of seed priming with Selenium nanoparticles on germination and seedlings growth of tomato. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, M.; Mazhar, M.W.; Maqbool, M.; Hussain, T.; Hussain, S.A.; Casini, R.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; Elansary, H.O. Seed Priming with the Selenium Nanoparticles Maintains the Redox Status in the Water Stressed Tomato Plants by Modulating the Antioxidant Defense Enzymes. Plants 2023, 12, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Locascio, E.; Valenzuela, E.I.; Cervantes-Avilés, P. Selenium nanoparticles and maize: Understanding the impact on seed germination, growth, and nutrient interactions. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 11, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk Erdem, S.; Karakoyun Mutluay, M.; Karaer, M.; Gültaş, H.T. The Effect of Fe3O4 Nanoparticle Applications on Seedling Development in Water-Stressed Strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa ‘Albion’) Plants. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2025, 67, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.W.; Ishtiaq, M.; Maqbool, M.; Muzammil, K.; Mohieldin, A.; Dawria, A.; Altijani, A.A.G.; Salih, A.; Ali, O.Y.M.; Elzaki, A.A.M.; et al. Optimizing water relations, gas exchange parameters, biochemical attributes and yield of water-stressed maize plants through seed priming with iron oxide nanoparticles. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Shmarev, A.N.; Ivanov, A.A.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Kosobryukhov, A.; Yu, M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Shabala, S. Effects of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe3O4) on Growth, Photosynthesis, Antioxidant Activity and Distribution of Mineral Elements in Wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plants 2022, 11, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megahed, S.M.; El-Bakatoushi, R.F.; Amin, A.W.; El-Sadek, L.M.; Migahid, M.M. Nanopriming as an approach to induce tolerance against drought stress in wheat cultivars. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Sharma, P.; Ashokhan, S.; Yaacob, J.S.; Kumar, V.; Guleria, P. Magnesium oxide nanoparticles improved vegetative growth and enhanced productivity, biochemical potency and storage stability of harvested mustard seeds. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 116023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, Y.K.; Singh, M.; Manorama, K.; Lakra, N.; Zaid, A.; Zulfiqar, F. Plant phenolics: Neglected secondary metabolites in plant stress tolerance. Braz. J. Bot. 2024, 47, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.W.; Ishtiaq, M.; Maqbool, M.; Akram, R. Seed priming with Calcium oxide nanoparticles improves germination, biomass, antioxidant defence and yield traits of canola plants under drought stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, H.; Hao, Y.; Shang, H.; Jia, W.; Liang, A.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Ma, C. Size Effects of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles on Boosting Soybean Growth via Differentially Modulating Nitrogen Assimilation. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Aziz, K. Copper oxide-based nanoparticles in agro-nanotechnology: Advances and applications for sustainable farming. Agric. Food Secur. 2025, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tian, X.; Song, P.; Guo, W.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Ma, Z. The Influence of Cuprous Oxide Nanoparticles on Photosynthetic Efficiency, Antioxidant Responses and Grain Quality throughout the Soybean Life Cycle. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Thakor, A.B.; Patel, S. Palladium nanoparticles improved phenotypic characters and alter DNA content in IUCN red listed endangered plant species Pterocarpus santalinus L. Results Chem. 2025, 16, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, P.K.; Choubey, A.K. Optimizing growth performance of Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) via synergistic effects of biogenic Cu/Ni/Co oxide nanoparticles in conjunction with rice straw and pressmud-based vermicompost. Pedosphere 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremew, A.; Stovall, L.; Woldesenbet, S.; Ma, X.; Carson, L. Nanopriming with zinc oxide: A novel approach to enhance germination and antioxidant systems in amaranth. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1599192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.W.; Arshad, A.; Parveen, A.; Azeem, M.; Ishtiaq, M.; Thind, S.; Akram, R.; Maqbool, M.; Mazher, M.; Mahmoud, E.A.; et al. Interaction of arsenic stress and graphene oxide nanoparticle seed priming modulates hormonal signalling to enhance soybean (Glycine max L.) growth and antioxidant defence. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2025, 37, 2523548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Able, A.J.; Able, J.A. Priming crops for the future: Rewiring stress memory. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kasote, D.M. Nano-priming for inducing salinity tolerance, disease resistance, yield attributes, and alleviating heavy metal toxicity in plants. Plants 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, A.; Ghasemifar, E.; Shahgolzari, M. Seed Nanopriming to Mitigate Abiotic Stresses in Plants. In Interchopen Abiotic Stress in Plants–Adaptations to Climate Change; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalal, P.R.; Tomar, R.S.; Jajoo, A. SiO2 nanopriming protects PS I and PSII complexes in wheat under drought stress. Plant Nano Biol. 2022, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakham, W.; Sarmah, A.K.; Maensiri, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Nanopriming technology for enhancing germination and starch metabolism of aged rice seeds using phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venzhik, Y.; Deryabin, A.; Popov, V.; Dykman, L.; Moshkov, I. Gold nanoparticles as adaptogens increazing the freezing tolerance of wheat seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 55235–55249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, T.; Gopal, G.; Das, H.; Mukherjee, A.; Kundu, R. Nanopriming with zero-valent iron synthesized using pomegranate peel waste: A “green” approach for yield enhancement in Oryza sativa L. cv. Gonindobhog. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 163, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhalipour, M.; Mohammadi, S.A.; Esmaielpour, B.; Spanos, A.; Mahmoudi, R.; Mahdavinia, G.R.; Milani, M.H.; Kahnamoei, A.; Nouraein, M.; Antoniou, C.; et al. Seedling nanopriming with selenium-chitosan nanoparticles mitigates the adverse effects of salt stress by inducing multiple defence pathways in bitter melon plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.; Latif, S.; Saeed, F.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Alsahli, A.A.; Jan, S.; Ahmad, P. Seed priming with titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhances seed vigor, leaf water status, and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize (Zea mays L.) under salinity stress. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2021, 33, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.G.; Pelegrino, M.T.; Ferreira, A.S.; Bazzo, J.H.; Zucareli, C.; Seabra, A.B.; Oliveira, H.C. Seed priming with copper-loaded chitosan nanoparticles promotes early growth and enzymatic antioxidant defense of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Chaparro, E.H.; Patiño-Cruz, J.J.; Anchondo-Páez, J.C.; Pérez-Álvarez, S.; Chávez-Mendoza, C.; Castruita-Esparza, L.U.; Marquez, E.M.; Sánchez, E. Seed Nanopriming with ZnO and SiO2 Enhances Germination, Seedling Vigor, and Antioxidant Defense Under Drought Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairilanwar, K.A.; Yi, S.J.; Bakri, M.D.I.; Nawi, I.H.M.; Azmi, A.A.A.R.; Aik, C.K. Eco-friendly nanopriming: Zinc oxide nanoparticles derived from banana peel extract for improved germination of chili seeds. J. Seed Sci. 2025, 47, e202547006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, T.; Zhou, C.; Wan, X.; He, X.; Miao, P.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Hu, M.; et al. Nano-priming with selenium nanoparticles reprograms seed germination, antioxidant defense, and phenylpropanoid metabolism to enhance Fusarium graminearum resistance in maize seedlings. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulhassan, Z.; Yang, S.; He, D.; Khan, A.R.; Salam, A.; Azhar, W.; Muhammad, S.; Ali, S.; Hamid, Y.; Khan, I.; et al. Seed priming with nano-silica effectively ameliorates chromium toxicity in Brassica napus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombuloglu, G.M.; Aldahnem, A.; Tombuloglu, H.; Slimani, Y.; Akhtar, S.; Hakeem, K.R.; Almessiere, M.; Baykal, A.; Ercan, I.; Manikandan, A. Uptake and bioaccumulation of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.): Effect of particle-size. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 22171–22186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.M.; Noman, M.; Ahmed, T.; Ali, S.; Ulhassan, Z.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, G. Exogenous calcium oxide nanoparticles alleviate cadmium toxicity by reducing Cd uptake and enhancing antioxidative capacity in barley seedlings. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Fu, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Yue, L.; Li, J.; Khan, Z.; Nie, L.; Wu, H. Nanopriming with selenium doped carbon dots improved rapeseed germination and seedling salt tolerance. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Salam, A.; Li, G.; Iqbal, B.; Ulhassan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Azhar, W.; Liaquat, F.; Shah, I.H.; Hassan, S.S.u.; et al. Nanoparticles and their crosstalk with stress mitigators: A novel approach towards abiotic stress tolerance in agricultural systems. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1280–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Kaushal, P.; Sidhu, A.K. Harnessing biological synthesis: Zinc oxide nanoparticles for plant biotic stress management. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1432469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorobets, Y.; Gorobets, S.; Gorobets, O.; Magerman, A.; Sharai, I. Biogenic and Anthropogenic Magnetic Nanoparticles in the Phloem Sieve Tubes of Plants: Magnetic Nanoparticles in Plants. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2023, 12, e5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Zia, U.; Rehman, M.; Adrees, M.; Arshad, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ali, L.; Hussain, A.; Chatha, S.A.S.; et al. Alleviation of cadmium accumulation in maize (Zea mays L.) by foliar spray of zinc oxide nanoparticles and biochar to contaminated soil. Environ Pollut. 2019, 248, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páramo, L.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Vega-González, M.; Escobar-Alarcón, L.; Esquivel, K. Medicago sativa L. Plant Response against Possible Eustressors (Fe, Ag, Cu)-TiO2:Evaluation of Physiological Parameters, Total Phenol Content, and Flavonoid Quantification. Plants 2023, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, N.A.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Alkharpotly, A.A.; Sayed, O.A.; Dawood, A.F.; Hossain, M.A.; Abdelrhim, A.S.; Dawood, M.F. Rice-husks synthesized-silica nanoparticles modulate silicon content, ionic homeostasis, and antioxidants defense under limited irrigation regime in eggplants. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Gan, Y.; White, J.C.; Zhang, X.; Wei, D.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, C. Fe2O3 nanoparticles enhance soybean resistance to root rot by modulating metabolic pathways and defense response. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouri, F.; Sarwar, S.; Sun, L.; Riaz, M.; Haider, F.U.; Ashraf, H.; Lai, M.; Imran, M.; Liu, J.; Ali, S.; et al. Silicon and iron nanoparticles protect rice against lead (Pb) stress by improving oxidative tolerance and minimizing Pb uptake. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Joshi, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Jindal, N.; Awasthi, A.; Kaur, S. Foliar application of selenium nanoparticles, multiwalled carbon nanotubes and their hybrids stimulates plant growth and yield characters in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under salt stress. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 11, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelwamondo, A.M.; Maaza, M.; Mohale, K.C. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and nutrient acquisition of three groundnut genotypes exposed to different concentrations of magnesium oxide and calcium carbonate nanoparticles. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 59, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizkhani, S.; Javadi, T.; Ghaderi, N.; Farzinpour, A. Replacing conventional iron with cysteine-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles in soilless culture of strawberry. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 318, 112098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, P.; Puopolo, G.; Santoyo, G. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms: New insights and the way forward. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 318, 128168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrusquía-Jiménez, N.I.; González-Arias, B.; Rosales, A.; Esquivel, K.; Escamilla-Silva, E.M.; Ortega-Torres, A.E.; Guevara-González, R.G. Elicitation of Bacillus cereus-Amazcala (B.c-A) with SiO2 Nanoparticles Improves Its Role as a Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) in Chili Pepper Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanović, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Natić, M.; Kuča, K.; Jaćević, V. The significance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense system in plants: A concise overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 552969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Jadon, V.S.; Sharma, V.; Chun, S.C.; Sivanesan, I. Nanoparticles as a tool for alleviating plant stress: Mechanisms, implications, and challenges. Plants 2024, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almiman, B.; El-Blasy, S.A.; El-Gendy, H.M.; Rashad, Y.M.; Abd El-Hai, K.M.; El-Sayed, S.A. Metallic oxide nanoparticles enhance chickpea resistance to root rot and wilt. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2024, 63, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Cai, L.; Jia, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Sun, X. Foliar Exposure of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles on Nicotiana benthamiana: Evidence for Nanoparticles Uptake, Plant Growth Promoter and Defense Response Elicitor against Plant Virus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 395, 122415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, I.; Kumari, S.; Ahmad, R.; Hussain, S.J.; Alamri, S.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Khan, M.I.R. Silver nanoparticle regulates salt tolerance in wheat through changes in ABA concentration, ion homeostasis, and defense systems. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.D.; Kalita, M.C. Alleviation of salt stress complications in plants by nanoparticles and the associated mechanisms: An overview. Plant Stress 2023, 7, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoobi, A.; Saboora, A.; Asgarani, E.; Efferth, T. Iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs) elicited Artemisia annua L. in vitro, toward enhancing artemisinin production through overexpression of key genes in the terpenoids biosynthetic pathway and induction of oxidative stress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2024, 156, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, M.; Attique, I.; Zahra, M.; Khan, A.K.; Hahim, M.; Hano, C.; Anjum, S. Metal oxide nanoparticles and plant secondary metabolism: Unraveling the game-changer nano-elicitors. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2023, 155, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Kaousar, R.; Haq, S.I.U.; Shan, C.; Wang, G.; Rafique, N.; Shizhou, W.; Lan, Y. Zinc-oxide nanoparticles ameliorated the phytotoxic hazards of cadmium toxicity in maize plants by regulating primary metabolites and antioxidants activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1346427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayab, N.; Alam, M.A. Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Promising Stimulant for Augmenting Cold Stress Resistance in Safed Velchi Cultivars of Banana Plants. J. Himal. Ecol. Sustain. 2023, 18, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Narware, J.; Singh, S.P.; Ranjan, P.; Behera, L.; Das, P.; Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S. Enhancing tomato growth and early blight disease resistance through green-synthesized silver nanoparticles: Insights into plant physiology. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 166, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Ahmed, S.; Abbasi, A.; Khan, M.T.; Subhan, M.; Bukhari, N.A.; Hatamleh, A.A.; Abdelsalam, N.R. Plant mediated fabrication of silver nanoparticles, process optimization, and impact on tomato plant. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmereke, K.M.; Venkataraman, S.; Moiketsi, B.N.; Khan, M.R.; Hassan, S.H.; Rantong, G.; Masisi, K.; Kwape, T.E.; Gaobotse, G.; Zulfiqar, F.; et al. Nanoparticle elicitation: A promising strategy to modulate the production of bioactive compounds in hairy roots. Food Res. Int. 2024, 178, 113910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdallah, N.M.; Alzahrani, H.S. The potential mitigation effect of ZnO nanoparticles on [Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench] metabolism under salt stress conditions. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3132–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabian, S.; Farhangi-Abriz, S.; Zahedi, M. Efficacy of FeSO4 nano formulations on osmolytes and antioxidative enzymes of sunflower under salt stress. Ind J Plant Physiol. 2018, 23, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avestan, S.; Ghasemnezhad, M.; Esfahani, M.; Byrt, C.S. Application of Nano-Silicon Dioxide Improves Salt Stress Tolerance in Strawberry Plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkow, R.; Sękara, A.; Pokluda, R.; Smoleń, S.; Kalisz, A. Biochemical Response of Oakleaf Lettuce Seedlings to Different Concentrations of Some Metal (oid) Oxide Nanoparticles. Agronomy 2020, 10, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răcuciu, M.; Tecucianu, A.; Oancea, S. Impact of Magnetite Nanoparticles Coated with Aspartic Acid on the Growth, Antioxidant Enzymes Activity and Chlorophyll Content of Maize. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, G.; Chen, L.; Gu, J.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Cerium oxide nanoparticles improve cotton salt tolerance by enabling better ability to maintain cytosolic K+/Na+ ratio. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mokadem, A.Z.; Sheta, M.H.; Mancy, A.G.; Hussein, H.-A.A.; Kenawy, S.K.M.; Sofy, A.R.; Abu-Shahba, M.S.; Mahdy, H.M.; Sofy, M.R.; Al Bakry, A.F.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Kaolin and Silicon Nanoparticles for Ameliorating Deficit Irrigation Stress in Maize Plants by Upregulating Antioxidant Defense Systems. Plants 2023, 12, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Mohamed, G.F.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; Rady, M.M.; Ali, E.F. Foliar Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Promotes Drought Stress Tolerance in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plants 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, M.; Rajput, V.D.; Al-Khuraif, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Yu, F. Effect of Foliar Fertigation of Chitosan Nanoparticles on Cadmium Accumulation and Toxicity in Solanum lycopersicum. Biology 2021, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHarethi, A.A.; Abdullah, Q.Y.; AlJobory, H.J.; Anam, A.M.; Arafa, R.A.; Farroh, K.Y. Zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles as a potential solution for controlling Phytophthora infestans, the late blight disease of potatoes. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Meza, D.Y.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Esquivel, K.; Carbajal-Valenzuela, I.; Avila-Quezada, G.D. Green silver nanoparticles display protection against Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, B.; Zhao, T.; Xu, X.; Lin, H.; Ji, Y.; Yin, Z.; Ding, X. Silica nanoparticles protect rice against biotic and abiotic stresses. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryfon, P.; Kamou, N.N.; Ntalli, N.; Mourdikoudis, S.; Karamanoli, K.; Karfaridis, D.; Menkissoglu-Spiroudi, U.; Dendrinou-Samara, C. Coated Cu-doped ZnO and Cu nanoparticles as control agents against plant pathogenic fungi and nematodes. NanoImpact 2022, 28, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, S.H.; Raja, N.I.; Ikram, M.; Oraby, H.F.; Mashwani, Z.-U.-R.; Mohamed, A.H.; Singh, A.; Omar, A.A. Plant-based Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Trigger Biochemical and Proteome Modifications in Triticum aestivum L. under Biotic Stress of Puccinia striiformis. Molecules 2022, 27, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satti, S.H.; Raja, N.I.; Javed, B.; Akram, A.; Mashwani, Z.-u.-R.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ikram, M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles elicited agromorphological and physicochemical modifications in wheat plants to control Bipolaris sorokiniana. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejaz, M.; Raja, N.I.; Mashwani, Z.U.R.; Ahmad, M.S.; Hussain, M.; Iqbal, M. Effect of silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate on growth of rice under biotic stress. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 12, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, H.; Batool, T.; Anjum, T.; Illyas, A.; Li, G.; Naseem, S.; Riaz, S. Antifungal Potential of Green Synthesized Magnetite Nanoparticles Black Coffee–Magnetite Nanoparticles Against Wilt Infection by Ameliorating Enzymatic Activity and Gene Expression in Solanum lycopersicum L. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 754292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Ellatif, S.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Safhi, F.A.; Abdel Razik, E.S.; Kabeil, S.S.A.; Aloufi, S.; Alyamani, A.A.; Basuoni, M.M.; ALshamrani, S.M.; Elshafie, H.S. Green Synthesized of Thymus vulgaris Chitosan Nanoparticles Induce Relative WRKY-Genes Expression in Solanum lycopersicum against Fusarium solani, the Causal Agent of Root Rot Disease. Plants 2022, 11, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashry, R.M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; El-Sobki, A.E.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Al-Otaibi, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Saad, A.M.; Elshaer, N. Biological silicon nanoparticles maximize the efficiency of nematicides against biotic stress induced by Meloidogyne incognita in eggplant. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, Y.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Alpuche-Solís, Á.G.; Cabrera, R.I.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Carbon Nanotubes Decrease the Negative Impact of Alternaria solani in Tomato Crop. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.M.; Elgobashy, S.F.; Omara, R.I.; Derbalah, A.S.; Abdelfatah, M.; El-Shaer, A.; Al-Askar, A.A.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; Essa, T.; et al. Antifungal Activity of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles against Root Rot Disease in Cucumber. J. Fungi. 2022, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Montejo, S.d.J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F.; Saavedra-Trejo, D.L.; Vargas-Hernandez, M.; Palos-Barba, V.; Macias-Bobadilla, I.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.M.; Torres-Pacheco, I. Inhibition of pepper huasteco yellow veins virus by foliar application of ZnO nanoparticles in Capsicum annuum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. Impact of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles on soil bacteria and the enantioselective transformation of racemic-metalaxyl in agricultural soil with Lolium perenne: A wild greenhouse cultivation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 11242–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Iqbal, S.; Gui, H.; Xu, J.; An, S.; Xing, B. Nano-iron oxide (Fe3O4) mitigates the effects of microplastics on a ryegrass soil–microbe–plant system. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 24867–24882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F. Metagenomic analysis reveals soil microbiome responses to microplastics and ZnO nanoparticles in an agricultural soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).