Abstract

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) is a traditional and economically important crop in Bulgaria. The cultivated areas are primarily planted with seven Bulgarian varieties: ‘Hemus’, ‘Druzhba’, ‘Sevtopolis’, ‘Yubileina’, ‘Raya’, ‘Hebar’, and ‘Karlovo’. Except for ‘Karlovo’, these cultivars are widely grown due to their proven agronomic performance and adaptability across different regions of the country. However, their genetic diversity and relationships have not been deeply examined. In this study, 13 Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) markers were used to assess the genetic diversity of those seven Bulgarian cultivars. This research provides the first report on the application of SCoT markers in lavender accessions. The results revealed considerable polymorphism, confirming the effectiveness of the SCoT marker system for L. angustifolia. The obtained data indicate moderate genetic diversity among the cultivars, supported by the effective number of alleles and polymorphic information content. Cluster analysis (UPGMA) and Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) demonstrated clear genetic differentiation, grouping the cultivars according to their genetic proximity. These findings provide valuable baseline information for future selection, conservation, and genetic evaluation of Bulgarian lavender.

1. Introduction

As one of the most important essential oil crops, Lavandula angustifolia Mill. holds a leading position in the production of high-quality lavender oil, distinguished by the specific characteristics of Bulgarian cultivars. The primary use of lavender essential oil is in perfumery and cosmetics. The secondary metabolites identified in lavender include well-documented antiseptic and bactericidal properties, which support its broad application in medicine, pharmacy, and aromatherapy [1,2]. In recent years, both science and industry have recognized new opportunities for the application of lavender oil in various industrial sectors [3]. In Bulgaria, fifteen cultivars of L. angustifolia have been officially developed and approved by the State Variety Commission. Among them, ‘Aroma’, ‘Svezhest’, ‘Venets’, ‘Kazanlak’, and ‘Karlovo’ are the oldest Bulgarian varieties, created in the 1950s and 1960s. These cultivars are now excluded from large-scale cultivation due to their lower economic performance and inability to meet modern market requirements. The cultivars ‘Hemus’, ‘Druzhba’, ‘Yubileina’, ‘Sevtopolis’, ‘Raya’, and ‘Hebar’ are the result of long-term selection work carried out by researchers at the Institute of Roses and Essential Oil Crops (IREMK). They demonstrate proven agronomic stability and are widely represented in commercial lavender fields across the country. Due to their excellent combination of chemical composition and consistent yield of fresh biomass, Bulgarian cultivars have maintained the country’s leading position in the global lavender oil market for more than six decades. Each cultivar possesses distinct botanical and agronomic traits [4]. The chemical composition of lavender oil shows a wide range of variation [5,6,7], primarily influenced by the cultivar, cultivation region, harvest time, processing method, and applied agronomic practices [8,9].

Assessment of genetic diversity is a key aspect contributing to the conservation and effective utilization of genetic resources. Molecular markers provide essential information on variations within the plants’ genome and the structure of their populations. Studies on the genetic diversity of Lavandula species are relatively limited, with only a few investigations using markers such as EST-SSR, SRAP, RAPD, ISSR and SSR [10,11,12,13]. Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) polymorphism is a gene-based molecular marker system that amplifies genomic regions flanking the ATG translation initiation codon, using conserved primers [14]. SCoT markers are recognized for their simplicity, efficiency, high polymorphism, and reproducibility. Furthermore, compared with RAPD and ISSR markers, SCoT markers have demonstrated higher reproducibility and discriminatory power when evaluating genetic variation and population structure across diverse plant varieties [15,16]. SCoT markers have also been extensively applied to evaluate genetic diversity and population structure in numerous Lamiaceae species, both wild and cultivated, serving as an important complementary tool for selection strategies and the characterization of genetic resources. The first SCoT-based assessment of genetic diversity and relationships among 36 global Ocimum accessions demonstrated their strong efficiency, expressed through higher mean values for percentage polymorphism (%PB), polymorphic information content (PIC), and resolving power (RP) compared with ISSR markers [17]. In contrast, another study on five Ocimum species reported greater polymorphism using ISSR markers; however, the SCoT profiles generated more species-specific fragments than ISSR and SRAP markers, which may be particularly valuable for trait improvement in Ocimum [18].

SCoT markers were also effectively applied in the characterization of 25 local Ocimum cultivars in Egypt, where the authors emphasized their capacity to discriminate among closely related species and cultivars [19]. They were likewise the preferred method for evaluating eight Ocimum species in Nigeria [20]. Conversely, a recent study on four Egyptian Ocimum cultivars challenged the higher efficiency of SCoT markers, reporting that RAPD markers exhibited superior discriminatory power [21]. These contrasting findings highlight the necessity of evaluating and combining different marker systems across genera, species, and even cultivars of economically important plants.

Another important representative of the Lamiaceae family, Thymus, has also been effectively studied using four SCoT markers, all of which exhibited polymorphism and successfully distinguished 13 wild and one cultivated genotype from Romania [22]. A more recent investigation confirmed this efficiency in 32 accessions of Thymus vulgaris L. collected from the Divriği district of Sivas Province, Turkey [23].

For endemic species, determining the degree of threat they face is essential, and genetic diversity is a direct indicator of their vulnerability. In Origanum acutidens L., a total of 70 genotypes from natural habitats across different regions of Turkey were effectively evaluated using the polymorphism generated by 10 SCoT markers. Based on these markers, the authors reported comparatively high genetic variation within the species [24]. The accuracy of SCoT markers has also been demonstrated in assessments of genetic diversity, species identification, and phylogeny in Mentha and Salvia [25,26].

Therefore, we carried out the first study on Lavandula accessions using SCoT markers. The aim of the study was to establish the efficiency of SCoT markers in the assessment of genetic diversity and distinguishing Bulgarian lavender varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The source material for this analysis was obtained from certified plants in the mother plantations of IREMK in February 2025, where the cultivars are grown according to established methods and schemes for maintenance and selection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bulgarian lavender varieties and their origin.

2.2. DNA Isolation

Fresh leaves from an individual plant of the seven cultivars—‘Hemus’, ‘Druzhba’, ‘Sevtopolis’, ‘Yubileina’, ‘Raya’, ‘Hebar’, and ‘Karlovo’—were used for DNA extraction using the Disruptor Genie homogenizer (Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA) and the Quick-DNA Plant/Seed Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and yield of the extracted DNA were verified using a NanoVue Plus spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare UK Limited, Amersham Place, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.3. SCoT Analysis

We selected 13 SCoT primers (Table 2) due to their effectiveness in other essential oil-bearing plants and used them for amplification with all cultivars [27,28]. The PCR amplifications were performed in a total volume of 20 μL, containing 1 μL (50 ng) genomic DNA, 10 μL Red Taq DNA Polymerase 2 × Master Mix, 1 μL (10 pmol) Primer (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), and 8 μL nuclease-free ddH2O. Amplification was performed on a Doppio Gradient 2 × 48 well thermal cycler (VWR®, Darmstadt, Germany), using the following program: initial denaturation at 94 °C/5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C/45 s denaturation, 54–61 °C specific primer annealing for 45 s, extension at 72 °C/90 s; and final extension at 72 °C/10 min. Gels were stained with GelRed® (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) and comprised 10 μL of product mixed with 2 μL loading buffer and NZYDNA Ladder VI (50–1500 bp). SCoT-PCR amplified products were detected through horizontal electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel with 1 × TBE buffer for 90 min at 110 V/cm. Band detection and photography were carried out using an imaging analysis system (Bio-Imaging System, Modi’in-Maccabim-Re’ut, Israel).

Table 2.

The SCoT primers used, Specific annealing temperature (sTa°), Total bands (TB), Polymorphic bands (PB), Monomorphic bands (MB), Effective multiplex ratio (EMR), Polymorphic information content (PIC), Resolving power (RP), Marker index (MI).

2.4. Data Analysis

The SCoT-PCR amplified products were converted into a binary data matrix, with presence of a band, or its absence. The primer efficiency was evaluated by the following parameters: polymorphic information content (PIC) [29], effective multiplex ratio (EMR) [30], marker index (MI) [31], and resolving power (RP) [32].

The polymorphism information content (PIC) for each locus was calculated as:

where i denotes the locus, fi is the frequency of the amplified fragments, and (1 − fi) represents the frequency of the non-amplified fragments. Fragment frequency was computed as the proportion of genotypes showing an amplified fragment at a given locus, relative to the total number of genotypes. The average PIC value across all loci generated by each primer was considered the PIC of that primer.

PICi = 2fi(1 − fi)

The effective multiplex ratio (EMR) was calculated as:

where n represents the mean number of fragments amplified per primer (multiplex ratio), and β is derived from the number of polymorphic loci (PB) and monomorphic loci (MB):

EMR = n × β

β = PB/(PB + MB)

The marker index (MI) was calculated as:

characterizing the ability of each primer to detect polymorphic loci among the evaluated genotypes.

MI = EMR × PIC

The resolving power (RP) was calculated as:

where Ib denotes the band informativeness value and was computed using:

with pi representing the proportion of genotypes showing the presence of the fragment (ith band).

RP = Σ Ib,

Ib = 1 − (2|0.5 − pi|),

Genetic distances for all cultivars were calculated by GenALEx 6.5 for Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) [33]. The eigenvalues were exported and subsequently visualized using GraphPad Prism 10.6.1. Nei’s [34] gene diversity (H), presented as expected heterozygosity (He), and Shannon’s Information Index (I) for all primers was analyzed in PopGen32. The genetic relationships from the Nei genetic distance obtained in PopGen32 were illustrated by UPGMA clustering in MEGA 12 [35].

3. Results

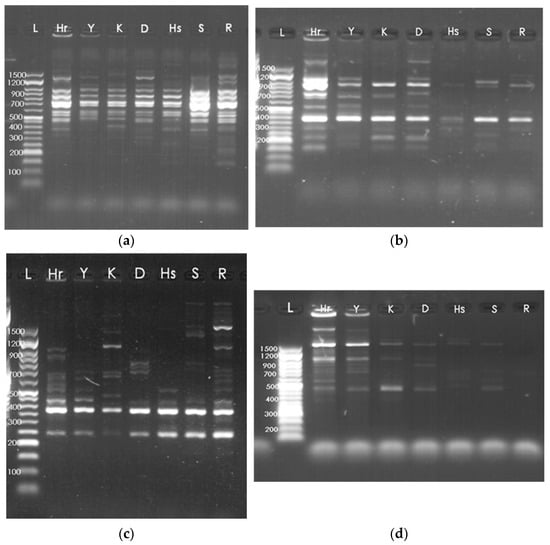

In the present study, thirteen SCoT markers generated a total of 135 amplification products across seven Bulgarian lavender cultivars. Among these, 83 bands were polymorphic and 52 were monomorphic, corresponding to a polymorphism percentage ranging from 33.33% for primers SCoT 24 and SCoT 17 to 100% for SCoT 5, SCoT 8, and SCoT 26, with an average of 63.9% (Table 2). The total number of amplified fragments varied from six (SCoT 26 and SCoT 17) to sixteen (SCoT 12). Representative SCoT-PCR amplification profiles for all cultivars are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

SCoT-PCR amplification patterns of lavender cultivars: (a) SCoT 11, (b) SCoT 12, (c) SCoT 3, (d) SCoT 9. Cultivar IDs are shown in Table 1: ‘Hebar’ (Hr), ‘Yubileina’ (Y), ‘Karlovo’ (K), ‘Druzhba’ (D), ‘Hemus’ (Hs), ‘Sevtopolis’ (S), ‘Raya’ (R); L—NZYDNA Ladder VI (50–1500 bp).

The polymorphic information content (PIC) values of the primers ranged from 0.11 (SCoT 14) to 0.85 (SCoT 26), indicating differences in the discriminatory capacity of the respective markers. The average PIC value of 0.45 reflects a moderate level of genetic diversity among the investigated cultivars. The effective multiplex ratio (EMR) exhibited an average value of 2.74, with the highest value obtained for SCoT 4 (3.78) and the lowest for SCoT 14 (0.79). The resolving power (RP) values ranged from 3.43 (SCoT 26) to 23.04 (SCoT 11), with an average of 14.46, indicating substantial variation in marker efficiency. The highest marker index (MI) was reported for SCoT 3 (2.26), whereas the lowest was observed for SCoT 14 (0.09) (Table 2).

For all primers used, the amplified fragments ranged in size from approximately 150 bp to 1500 bp, with average allele frequencies of 0.33 and 0.67, respectively. The effective number of alleles (Ne) varied from 1.18 for SCoT 14 to 1.70 for SCoT 7 and SCoT 8, with an average value of 1.50. Evidence of considerable genetic diversity was detected among the studied genotypes, with an average value across all loci and cultivars of I = 0.39. The highest Shannon’s information index (I = 0.58) was recorded for primers SCoT 5, SCoT 8, and SCoT 9, whereas the lowest value (I = 0.17) was observed for SCoT 14. The expected heterozygosity (He) ranged from 0.11 for SCoT 14 to 0.42 for SCoT 5, with an overall average of 0.27 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genetic diversity indices of used SCoT markers: p and q (allele frequency), different (Na) and effective (Ne) number alleles, Shannon’s Information Index (I) and expected heterozygosity (He).

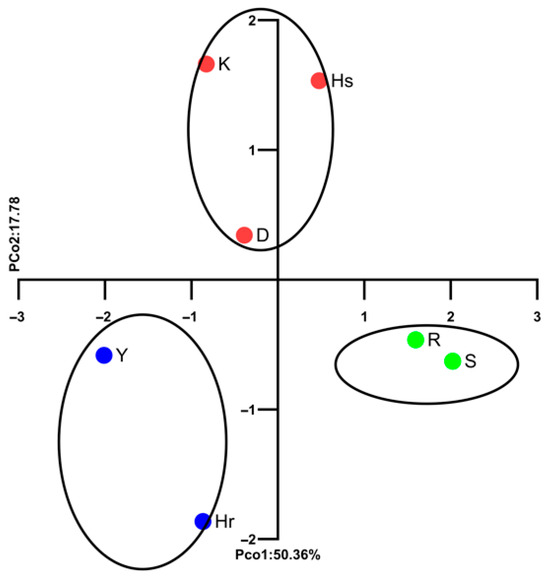

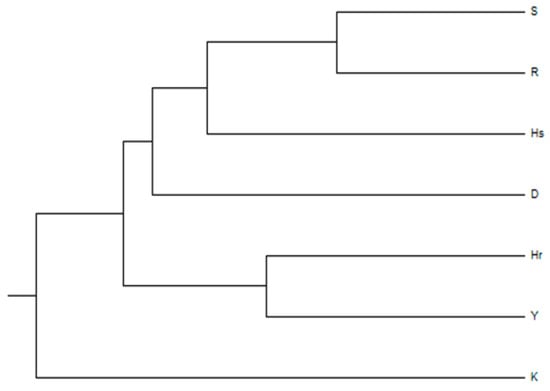

Genetic relationships among the seven Bulgarian lavender cultivars were assessed using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) and UPGMA cluster analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The PCoA clearly differentiated the cultivars into three distinct groups, explaining 50.36% of the total genetic variation across the first two axes and accounting for 68.14% of the cumulative variance (Figure 2). The UPGMA dendrogram further supports this clustering pattern, revealing the closest genetic relationship between cultivars ‘Sevtopolis’(S) and ‘Raya’(R), followed by ‘Hemus’(H). A higher degree of similarity was also observed between cultivars ‘Hebar’ (Hr) and ‘Yubileina’(Y), whereas ‘Karlovo’ (K) appeared to be the most genetically distinct from the remaining six cultivars (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

SCoT-PCoA plot, based on the genetic distances among the studied Bulgarian lavender cultivars. For cultivar abbreviations, see Table 1.

Figure 3.

UPGMA clustering based on molecular data obtained with thirteen SCoT primers. For cultivar abbreviations, see Table 1.

4. Discussion

The assessment of genetic diversity and clarification of relationships among related individuals, such as cultivars, are essential for targeted selection and the effective conservation and utilization of plant genetic resources. In the present study, we investigated seven Bulgarian Lavandula angustifolia cultivars using 13 SCoT markers and confirmed the presence of notable genetic variation among them (He = 0.27, I = 0.39). Similar findings have been widely reported in the literature, where SCoT markers have proven to be efficient, reproducible, highly informative tools for genetic characterization and diversity studies in various plant species, reliable even in advanced selection research [16,28,36,37,38]. SCoT markers were shown to be more effective than CBDP and iPBS in detecting polymorphism and differentiating genotypes among ninety-seven individuals of Clerodendrum serratum (L.) Moon from eight populations from different regions of Manipur, North-East India. All twelve SCoT markers used by the authors exhibited 100% polymorphism and produced high mean values for the effective multiplex ratio (EMR = 13.75), polymorphic information content (PIC = 0.204), and marker index (MI = 2.69). These results enabled the authors to identify the regions containing the most vulnerable populations [39]. In our investigation, the average values of the standard indices used to evaluate marker system efficiency—PIC (0.45), Rp (14.46), MI (1.3), and EMR (2.74)—demonstrated the suitability and discriminative potential of SCoT markers for cultivar differentiation in Lavandula angustifolia. The highest diversity parameters were observed for SCoT 26 (PIC = 0.85, I = 0.50, He = 0.25), SCoT 8 (PIC = 0.79, I = 0.58, He = 0.40), SCoT 9 (PIC = 0.70, I = 0.58, He = 0.40), and SCoT 5 (PIC = 0.61, I = 0.58, He = 0.42), indicating that these primers are particularly effective and informative for genetic diversity assessment in lavender genotypes. They can also be sufficiently informative and used for identifying loci, as reported in the case of Melissa officinalis L., where the discriminating power of only four SCoT markers was found to be sufficient to identify loci with potential adaptive significance [40]. The authors highlighted the high level of within-population genetic diversity across ten populations of M. officinalis, demonstrated by the high percentage of polymorphism in each population (mean = 72.54%) and by the average values of genetic diversity parameters: effective number of alleles (Ne = 1.33), Shannon’s information index (I = 0.32), and expected heterozygosity (He = 0.20) [40].

The genetic variability previously reported for Bulgarian lavender cultivars [11] was confirmed in the present study. Using 51 SRAP primer pairs, Zagorcheva et al. calculated a mean PIC value of 0.27 for the same Bulgarian cultivars, together with three superior essential-oil breeding lines and five foreign lavender varieties [11]. In contrast, the mean PIC value obtained in our study of 13 SCoT primers across seven cultivars (‘Hemus’, ‘Druzhba’, ‘Sevtopolis’, ‘Yubileina’, ‘Raya’, ‘Hebar’, and ‘Karlovo’) was 0.40, suggesting a higher polymorphic potential of SCoT markers. The genetic similarity values based on Jaccard coefficients reported earlier [11] ranged from 0.22 to 0.395, corresponding well with our Nei’s genetic distance values (0.17–0.49, Figure 3). The inclusion of foreign cultivars in their study did not significantly affect this comparison, as the authors reported only a 3.4% differentiation among cultivar groups based on AMOVA analysis.

Comparable research using dominant DNA markers has also demonstrated their potential in the assessment of genetic variation within Lavandula species. Ražná et al. evaluated twelve genotypes of Lavandula, including L. angustifolia and Lavandula × intermedia Emeric ex Loisel, using four RAPD primers [12]. Their results highlighted a cost-effective and efficient strategy for genetic diversity screening and genotype identification through digital electrophoretic DNA profiling. Likewise, another study utilized two RAPD and five ISSR markers to assess genetic stability in three Crimean lavender cultivars (‘Vdala’, ‘Sineva’, and ‘Stepnaya’) following in vitro propagation. The authors amplified 62 loci with polymorphism rates ranging from 41.7% to 88.9%, successfully verifying cultivar identity and confirming genetic stability [41]. This demonstrates that, in addition to evaluating genetic diversity among cultivars to determine their selection potential and estimating genetic distances to identify optimal parents, DNA markers can also be reliably applied for determining cultivar identity and controlling planting material. Maintaining cultivar identity is essential in lavender, as it determines the quality and chemical profile of the essential oils [42,43,44].

In the current study, we can confidently recommend the use of the SCoT marker system in lavender germplasm studies because three SCoT primers (SCoT 5, SCoT 8, and SCoT 26) achieved 100% polymorphism, while five additional primers (SCoT 3, SCoT 4, SCoT 9, SCoT 12, and SCoT 15) produced more than 50% polymorphic bands. These results highlight the robustness and informativeness of SCoT markers, supporting previous reports of their superior reproducibility and discriminatory ability compared to RAPD and ISSR systems. Given the practical need for simple, accessible, and low-cost molecular tools in crop improvement, our findings emphasize the applicability of SCoT markers for genetic characterization, varietal identification, and selection of Lavandula species.

Recent advancements in lavender genetics further reinforce the importance of molecular approaches for selection. A recent study presented the first genetic linkage map for L. angustifolia based on SSR markers in a segregating population derived from self-pollination of the cultivar ‘Hemus’ [13]. The resulting map was successfully applied to identify and localize QTLs associated with the accumulation of volatile terpenoids in flower tissues, marking a significant step forward in the molecular selection of lavender.

Our study contributes valuable data for future selection efforts and the improvement of lavender production by providing a molecular characterization of Bulgarian cultivars based on 13 SCoT markers and the genetic distances among them. These results expand the existing germplasm knowledge and offer practical insights for selecting parental lines in selection programs. Among the seven cultivars examined in our study, the smallest genetic distance (Nei’s distance = 0.17) was observed between ‘Sevtopolis’ and ‘Raya’. Both cultivars were obtained through mutagenesis—‘Sevtopolis’ via chemical mutagenesis and ‘Raya’ through radiation mutagenesis—and share a common progenitor, the cultivar ‘Hemus’ (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The greatest genetic differentiation was observed between ‘Karlovo’ and ‘Hemus’ (0.49), as well as between ‘Karlovo’ and the remaining cultivars (0.41–0.49). ‘Karlovo’ was developed through direct plant selection from a local lavender population established in 1967, likely derived from French germplasm, which may explain its greater genetic divergence from the Bulgarian breeding lines. Two other cultivars, ‘Yubileina’ and ‘Sevtopolis’, also displayed relatively high genetic distances (0.45). The ‘Druzhba’ variety is located between the two groups of most similar varieties—‘Hemus’, ‘Raya’ and ‘Sevtopolis’, and ‘Hebar’ and ‘Yubileina’ (Figure 3). The high degree of similarity between ‘Hebar’ and ‘Yubileina’ is further supported by their closely related morphological traits and biological characteristics. Both cultivars belong to the group characterized by dark violet inflorescences; they flower early and exhibit comparable levels of the major essential oil components. ‘Yubileina’ is among the most productive cultivars [44,45]; however, when evaluating yield stability under varying environmental conditions, it demonstrates higher stability only when growing conditions are relatively favorable. Under such conditions, ‘Hebar’ performs identical to ‘Yubileina’. In contrast, the cultivars ‘Hemuc’ and ‘Raya’ maintain consistently high yields even under suboptimal environmental conditions [45]. The cultivar ‘Hemus’ is recognized as the variety producing essential oil of the highest quality [43,44,46], which is also the reason it has served as the parental form of most subsequently developed Bulgarian cultivars. Since ‘Hebar’, ‘Sevtopolis’, and ‘Raya’ originated from ‘Hemus’, we may assume that the seeds treated to generate ‘Sevtopolis’ and ‘Raya’ might have resulted from self-pollination, whereas the seed treated to generate ‘Hebar’ may have originated from outcrossing.

The cultivar ‘Yubileina’ was developed in 1988 through hybridization, using hybrid No. 643x followed by individual selection in the first seed generation produced by open pollination. Because the hybrid was open-pollinated, the paternal parent may have belonged to any other cultivar grown nearby, whereas the maternal parent—hybrid No. 643x—has an unclear origin due to missing archival records at the Institute for Roses and Essential Oil Crops (IREMK). According to SRAP-based genetic analysis of Bulgarian lavender cultivars, ‘Hebar’ and ‘Sevtopolis’ cluster together with ‘Yubileina’ and ‘Druzhba’, while ‘Raya’ forms a separate cluster together with ‘Karlovo’ [11]. Nevertheless, different DNA marker systems often produce varying clustering patterns due to differences in the genomic regions they target, as well as the statistical approaches applied during data analysis.

The present study confirms the substantial genetic variability among Bulgarian L. angustifolia cultivars and demonstrates the effectiveness of SCoT markers in evaluating intraspecific diversity. Future research incorporating a wider range of genotypes and additional molecular markers will be a factor in further clarifying the genetic structure of Bulgarian lavender, the inter-cultivar relationships, and supporting ongoing selection and conservation efforts aimed at improving essential oil yield and quality.

5. Conclusions

SCoT markers proved to be an efficient molecular tool for the assessment of genetic diversity among L. angustifolia cultivars, revealing a high degree of polymorphism and clear, reproducible amplification profiles. Their accessibility, low cost, and strong discriminatory capacity make them a practical and reliable approach for the molecular characterization of lavender germplasm and for supporting selection programs. Using 13 SCoT primers, we confirmed the presence of genetic variation among seven Bulgarian lavender cultivars. Six of these cultivars are widely grown in the country (except ‘Karlovo’), emphasizing the importance of continued studies on their genetic structure. The results suggest that SCoT markers can assist in the identification and differentiation of cultivars, as well as support future selection efforts and quality control of planting material. The information obtained in this study may contribute to future selection, conservation, and genetic improvement work in Bulgarian lavender and aid in the sustainable management of this economically important crop.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to validation and writing—review and editing. Conceptualization, M.Z., V.B. and S.S.; methodology, M.Z.; software, M.Z.; formal analysis, M.Z., V.B. and S.S.; investigation, M.Z., V.B. and S.S.; resources, M.Z., V.B. and S.S. data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft, M.Z., V.B. and S.S.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, M.Z. and V.B.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science (MES) in the framework of the Bulgarian National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Component “Innovative Bulgaria,” Project No BG-RRP-2.004-0006-C02 “Development of research and innovation at Trakia University in service of health and sustainable well-being”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Science Fund grant number: KΠ 06 M61/7 15.12.22, Project: “Genetic Profile of Lavender Plantations from Different Regions of Bulgaria. Determining the Authenticity and Uniformity of the Initial Planting Material and Its Influence on the Quality of the Obtained Essential Oil.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mahmood, Z.F.; Sami, S.; Ahmed, D.M. A review about lavender importance. Russ. J. Biol. Res. 2020, 7, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajjjari, S.; Joshi, R.S.; Hugar, S.M.; Gokhale, N.; Meharwade, P.; Uppin, C. The effects of lavender essential oil and its clinical implications in dentistry: A review. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, H.M.A.; Wilkinson, J.M. Lavender essential oil: A review. Healthc. Infect. 2005, 10, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, M.; Nedkov, N. Essential Oil and Medicinal Crops. Modern Cultivation Technologies. Competitiveness. Funding; Cameo: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2004. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Shellie, R.; Mondello, L.; Marriott, P.; Dugo, G. Characterisation of lavender essential oils by using GC-MS with correlation of linear retention indices and comparison with comprehensive two-dimensional GC. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 970, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, A.; Balinova-Tcvetkova, A. Lavender: Obtaining Essential Oil Products in Bulgaria; UFT Academic Publishing House: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2019. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Kozuharova, E.; Simeonov, V.; Batovska, D.; Stoycheva, C.; Valchev, H.; Benbassat, N. Chemical composition and comparative analysis of lavender essential oil samples from Bulgaria in relation to pharmacological effects. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badzhelova, V.; Zhelyazkova, M.; Nedeva, D.; Donchev, I. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics of lavender oil from different regions of Bulgaria. J. Mt. Agric. Balk. 2025, 27, 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Stanev, S. Lavender part I. Zemed. Plus 2009, 7, 21–32. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Adal, A.M.; Demissie, Z.A.; Mahmoud, S.S. Identification, validation and cross-species transferability of novel Lavandula EST-SSRs. Planta 2015, 241, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorcheva, T.; Stanev, S.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I. SRAP markers for genetic diversity assessment of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) varieties and breeding lines. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2020, 34, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ražná, K.; Čerteková, S.; Štefúnová, V.; Habán, M.; Korczyk-Szabó, J.; Ernstová, M. Lavandula spp. diversity assessment by molecular markers as a tool for growers. Agrobiodivers. Improv. Nutr. Health Life Qual. 2023, 7, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, P.; Rusanov, K.; Rusanova, M.; Kitanova, M.; Atanassov, I. Development of SSR markers and construction of a genetic linkage map in lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). Preprints 2025, 2025011933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, B.; Mackill, D. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: A simple, novel DNA marker technique for generating gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2009, 27, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amom, T.; Tikendra, L.; Apana, N.; Goutam, M.; Sonia, P.; Koijam, A.S.; Potshangbam, A.M.; Rahaman, H.; Nongdam, P. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economically important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidyananda, N.; Jamir, I.; Nowakowska, K.; Varte, V.; Vendrame, W.A.; Devi, R.S.; Nongdam, P. Plant genetic diversity studies: Insights from DNA marker analyses. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 607–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Mishra, A.; Lal, R.K.; Dhawan, S.S. DNA fingerprinting and genetic relationship similarities among the accessions/species of Ocimum using SCoT and ISSR marker systems. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.Y.; Hussein, M.H.; El-Maaty, S.A.; Moghaieb, R.E. Detection of genetic variation among five basil species using ISSR, SCoT and SRAP markers. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 9909–9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhashem, Y.S.; Khalil, H.B.; El-Tahawey, M.A.; Soliman, K.A. Exploring the morphological and genetic diversity of Egyptian basil landraces (Ocimum sp.) for future breeding strategies. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyoola, O.I.; Ajose, T.E.; Chukwu, K.E.; Matthew, J.O.; Arogundade, O.; Akinyemi, S.O.S. Genetic diversity in Ocimum species as revealed by SCoT markers. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual Conference of HORTSON, Ogbomoso, Nigeria, 12–16 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hadi, A.H.; Habiba, R.M.; Abou El-Leel, O.F.; Ahmed, N.F. Genetic diversity of some basil varieties estimated using RAPD, SCoT and ISSR techniques. J. Agric. Chem. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beicu, R.; Popescu, S.; Neacsu, A.; Imbrea, I.M. Applicability of SCoT (Start Codon Targeted) markers in evaluation of Thymus genetic variability. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 52, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Temrel, T.M.; Çilesiz, Y. Investigation of genetic polymorphism in selected thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) accessions using SCoT molecular markers. Selcuk J. Agric. Food Sci. 2025, 39, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, H.; Hosseinpour, A.; Karagöz, F.P.; Cakmakci, R.; Haliloglu, K. Dissection of genetic diversity and population structure in oregano (Origanum acutidens L.) genotypes based on agro-morphological properties and SCoT markers. Biologia 2022, 77, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M.; Osman, E.A.; El-Tantawy, A.A. Taxonomical studies on four Mentha species grown in Egypt through morpho-anatomical characters and SCoT genetic markers. Plant Arch. 2019, 19, 2273–2286. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Khayatnezhad, M.; Minaeifar, A.A. Genetic variations and interspecific relationships in Salvia (Lamiaceae) using SCoT molecular markers. Caryologia 2021, 74, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, A.S.; Omidi, M.; Azizinezhad, R.; Etminan, A.; Badi, H.N. Genetic diversity analysis in a mini core collection of damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) germplasm from Iran using URP and SCoT markers. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminan, A.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Noori, A.; Ahmadi-Rad, A.; Shooshtari, L.; Mahdavian, Z.; Yousefiazar-Khanian, M. Genetic relationships and diversity among wild Salvia accessions revealed by ISSR and SCoT markers. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 32, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Ruiz, I.; Dendauw, J.; Vanbockstaele, E.; Depicker, A.; De Loose, M. AFLP markers reveal high polymorphic rates in ryegrasses (Lolium spp.). Mol. Breed. 2000, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, J.; Damodar, R.K.; Nagaraja, G.M.; Sethuraman, B.N. Comparison of multilocus RFLPs and PCR-based marker systems for genetic analysis of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Heredity 2001, 86, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Chabane, K.; Hendre, P.S.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Graner, A. Comparative assessment of EST-SSR, EST-SNP and AFLP markers for evaluation of genetic diversity and conservation of genetic resources using wild, cultivated and elite barleys. Plant Sci. 2007, 173, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, A.; Wilkinson, M.J. A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2006, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Deng, L.; Zhu, K.; Shi, D.; Wang, F.; Cui, G. Evaluation of genetic diversity and population structure of Annamocarya sinensis using SCoT markers. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Mo, J.; Wu, W.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Lai, T.; Zhanlun, O.; Zhenwen, Q.; Shixia, G.; Liao, J. Genetic diversity, population structure and identification of Dendrobium cultivars with high polysaccharide contents using SCoT, SCAR and nested PCR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Nazari, L.; Kordrostami, M.; Safari, P. SCoT marker diversity among Iranian Plantago ecotypes and their possible association with agronomic traits. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apana, N.; Amom, T.; Tikendra, L.; Potshangbam, A.M.; Dey, A.; Nongdam, P. Genetic diversity and population structure of Clerodendrum serratum (L.) Moon using CBDP, iPBS and SCoT markers. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 25, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohdar, F.; Sheidai, M. Genetic diversity and population structure in medicinal plant Melissa officinalis L. (Lamiaceae). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 1753–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanina, S.S.; Yegorova, N.A.; Stavtseva, I.V.; Abdurashitov, S.F. Genetic stability of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) plants obtained during long-term clonal micropropagation. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2023, 49, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, S.; Zagorcheva, T.; Atanassov, I. Lavender cultivation in Bulgaria-21 st century developments, breeding challenges and opportunities. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva, R.; Kırchev, H.; Delıbaltova, V.; Matev, A.; Chavdarov, P.; Raycheva, T. Essential oil chemical composition of lavender varieties cultivated in an untraditional agro-ecological region. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 32, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibaltova, V.; Manhart, S.; Stoychev, I.; Nedyalkov, M. Comparative research of productive and qualitative indicators in lavender varieties cultivated in Eastern Bulgaria. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2024, 67, 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Stanev, S. Evaluation of the stability and adaptability of the Bulgarian lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) cultivars’ yield. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Stanev, S.; Dzhurmanski, A. Guidelines for selection of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). Sci. Technol. I 2011, 6, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).