Abstract

Seed dormancy and germination traits of Campanulaceae species in relation to ecological factors remains unclear. Hence, we clarified the seed germination characteristics of five Campanulaceae species (Adenophora triphylla (Thunb.) A.DC., Asyneuma japonicum (Miq.) Briq., Campanula punctata Lam., Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., and Lobelia sessilifolia Lamb.) native to Korea. Seeds were subjected to varying temperatures, cold stratification (CS) durations, and gibberellic acid (GA3) concentrations. Seeds of all species imbibed water readily, suggesting the absence of physical dormancy. For A. triphylla, A. japonicum, and L. sessilifolia, suitable seed germination occurred under elevated temperature conditions: 74.0 ± 6.2%, 37.0 ± 1.0%, and 26.0 ± 3.5% germination, respectively, at 25 °C, and 79.0 ± 3.8%, 38.0 ± 3.5%, and 62.0 ± 8.4% germination, respectively, at 25/15 °C (day/night) after 7 weeks after incubation. Germination of C. punctata and C. pilosula was consistently low across all temperatures. CS treatment resulted in significant final germination improvement to ~70.0% in four species, excluding C. pilosula. GA3 application significantly enhanced seed germination by ~60.0% across all species, with the most notable effects observed at 1000 mg∙L−1. Overall, Campanulaceae species seeds are permeable, and pre-treatment with CS and GA3 is required for effective seed germination.

1. Introduction

Seed germination, the process by which a seed develops into a new plant, plays a vital role in the life cycle of plants. This process typically begins when the seed absorbs water, triggering metabolic activities that lead to the growth of the embryonic plant. However, seed germination is a complex physiological process regulated by multiple environmental signals. Successful germination requires that these factors, such as moisture, oxygen, and temperature, are present at optimal levels to break dormancy and initiate growth [1,2]. In natural environments, seed germination is essential for establishing and propagating seedlings, yet it is often influenced by seed dormancy [3,4,5]. Dormancy, shaped by genetic factors and environmental conditions, serves as an adaptive strategy that enables plant species to survive in diverse habitats. One of the key challenges in the domestication and cultivation of wild plant species is their propagation, with low and inconsistent germination percentages being a major obstacle to successful seed production [6]. This issue is largely attributed to seed dormancy, which complicates efforts to cultivate these species [7]. However, overcoming dormancy and improving seed germination in wild plants holds significant potential for various applications, including agriculture, horticulture, and the extraction of valuable resources [5,8,9]. Additionally, from the perspective of forest restoration, it is essential to understand the ecology of wild plants and the propagation methods of seeds with high genetic diversity to facilitate effective restoration [10]. Successfully addressing these challenges would allow for the more effective cultivation and utilization of wild species for various purposes.

Seed dormancy is crucial to plant survival by ensuring that germination occurs only under optimal environmental conditions for seedling survival [11]. Thus, seed dormancy is a crucial adaptive trait that enhances plant fitness by enabling wild plants to withstand diverse environmental stresses and adapt to varying ecological conditions [12]. Ecologically, seed dormancy prevents premature germination, reducing intraspecific competition and enhancing survival under adverse conditions. Thus, seed dormancy and germination are diverse physiological processes that can be classified into five distinct classes: physiological dormancy (PD), where germination is inhibited by physiological factors within the embryo; morphological dormancy (MD), characterized by an underdeveloped embryo; morphophysiological dormancy (MPD), a combination of both PD and MD; physical dormancy (PY), in which a water-impermeable seed or fruit coat prevents water uptake; and combinational (PY + PD), which involves both PY and PD [4]. In addition, freshly matured seeds with conditional dormancy (CD) germinate within a relatively narrow range of temperature conditions. However, this range expands after dormancy-breaking treatment. CD is particularly important as it represents an intermediate state where seeds can transition between dormancy and non-dormancy (ND) depending on environmental conditions [13]. Seeds in this state are highly sensitive to temperature, germinating only within a narrower temperature range than non-dormant seeds [4,14]. Seed dormancy characteristics can vary widely, and some species may display dormancy exhibiting more than two types depending on the species. They may display dormancy polymorphism as an evolutionary strategy to survive in diverse stress environments. In natural conditions, seed dormancy is primarily broken by seasonal environmental cues, particularly prolonged exposure to low winter temperatures [15].

Consequently, a more complex experimental process, including careful observations and evaluations of germination under varying temperature conditions, is essential for accurately classifying and breaking dormancy status. Based on previous studies, mature seeds of the Campanulaceae species are classified into one of four dormancy classes at dispersal from the mother plant: ND, MD, PD, or MPD [10,16,17,18,19,20].

Campanulaceae (the bellflower family) is distributed worldwide in temperate and subtropical regions. This family includes approximately 80 genera and over 2400 species [21]. Notable genera include Campanula, Phyteuma, and Codonopsis, with a predominant distribution in the Northern Hemisphere, although some species are also found in certain areas of the Southern Hemisphere. These plants typically grow as perennial herbs or shrubs, and some species are utilized for their medicinal properties. They thrive in well-drained soils and require ample sunlight for healthy growth. These plants produce flowers in various colors and possess significant ornamental value, making them popular in gardens and parks. Understanding seed dormancy and germination traits in relation to ecological factors is essential for the conservation and ornamental utilization of genetic resources in the Campanulaceae species.

We hypothesized that freshly matured seeds of the five Campanulaceae species would possess PD or MPD, and that cold stratification would be required to break such dormancy and facilitate germination. Thus, we primarily aimed to investigate the conditions required to break dormancy and promote seed germination and determine the class of seed dormancy for five Campanulaceae species. Specifically, we examined the impacts of (1) water imbibition to assess PY, (2) constant and fluctuating temperature conditions during germination fresh seeds and of seeds following dormancy-breaking treatments, and (3) both cold stratification (CS) and gibberellic acid (GA3) soaking to break dormancy as well as on germination. Our findings serve as a reference for species conservation through mass propagation protocols and support horticulturists and seed ecologists in efficiently producing seedlings in the Campanulaceae species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Material

Mature seeds of five wild Campanulaceae species were collected in the Korea between August and October 2021 for use in this experiment (Table 1). At the time of collection, all mother plants were at the full fruiting stage, having completed flowering and produced fully developed capsules. Seed maturity was assessed based on standard morphological indicators, including capsule browning, natural dehiscence, and the presence of fully formed seeds exhibiting species-specific mature coloration and firmness. Only fruits showing clear signs of physiological maturity were harvested. After the seeds were cleaned, they were examined to determine seed basic characteristics, including seed size (length × width, mm) (n = 10) and 1000 seed weight (g) (n = 100). Each parameter was repeated four times, and the weight of 1000 seeds was measured using an electronic balance (ML204/01, Mettle Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA). Subsequently, the seeds were dried in a drying room (15 °C, relative humidity (RH) of 15%) for 2 weeks, sieved to remove the pericarp (part of the fruit) surrounding the seeds, sealed in a plastic bag, and stored at 4 °C until use in the experiments. Although this drying step helped standardize seed moisture prior to germination assays, the initial moisture content of the seeds was not quantified. Although the five species were collected on different dates during the 2021 season, the seeds of each species were used for germination tests immediately after the drying and cleaning process. Therefore, the storage duration at 4 °C differed slightly among species but was not long enough for physiological dormancy to be alleviated through after-ripening. Thus, the seeds tested in this study represent freshly matured material without meaningful after-ripening effects.

Table 1.

List of Campanulaceae species seeds used in this experiment.

2.2. Seed Morphology and Embryo Development

Seeds were sectioned longitudinally or transversely using a stainless razor blade (Dorco, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The cross-sections were photographed with a digital microscope (DVM6, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), and seed morphology was observed to determine the presence of morphological dormancy (MD).

2.3. Water Imbibition Test

Initial seed moisture content was not determined; therefore, water uptake was expressed as the relative increase in seed mass compared with the initial dry mass. As such, the values presented indicate relative imbibition rather than absolute moisture content after hydration. The permeability of the seeds was determined to identify the physical dormancy (PY) in the Campanulaceae seeds under laboratory conditions (approximately 23 ± 2 °C, RH of 40–50%). Four replicates of 100 seeds were initially weighed using an electronic balance. Subsequently, the Campanulaceae seeds from each replicate were individually placed on two layers of filter paper (Whatman No. 2, Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) moistened with distilled water in 90 × 15 mm plastic Petri dishes (SPL Life Sciences Co., Ltd., Pocheon, Republic of Korea). The weight of Campanulaceae seeds was determined after 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 144 h of incubation. The water absorption by seeds was calculated using the water uptake formula [4].

Ws (%) = [(Wi − Wd)/Wd] × 100

Ws is the increase in seed mass, Wi is the seed weight after a given interval of imbibition, and Wd is the original seed weight before water absorption.

2.4. Effects of Temperature Regimes on Germination

Fresh Campanulaceae seeds were tested for germination at five constant (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 °C) and three alternating (15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C) temperature regimes with a photoperiod of 12/12 h (light/dark) in a growth chamber (TGC-130H, Espec Mic Corp., Aichi, Japan). Light during the daytime across all temperature regimes was 40 ± 10 µmol·m−2·s−1 photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) using fluorescent lamps. Four replicates of 25 seeds each were placed separately on a 1% agar (Agar, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) medium in 90 × 15 mm plastic Petri dishes, which were sealed with parafilm (PM-996, Bemis Company Inc., Neenah, WI, USA) during incubation.

2.5. Effects of Cold Stratification Period on Germination

To examine the response to cold stratification (CS) on dormancy-release for germination, the Campanulaceae seeds were incubated for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks at 5 °C. For each period of CS, 4 replicates of 25 seeds were placed in plastic Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) on a 1% agar medium, which was sealed with parafilm during incubation. After the end of each CS period for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks, four replicates of all seeds were incubated for 4 weeks at the 25/15 °C with a photoperiod of 12/12 h (light/dark) in a growth chamber.

2.6. Effects of Pre-Treatment with Gibberelic Acid (GA3) Concentration on Germination

The phytohormone gibberellic acid (GA3) has been used to dormancy-release as a characteristic for classifying the different kinds of seed dormancy [4]. To investigate the response to GA3 concentration on dormancy-release for germination, the Campanulaceae seeds were pre-treated with four concentrations of GA3 (≥90%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution (0 (control), 10, 100, or 1000 mg∙L−1). The GA3 solutions were formulated by fully dissolving GA3 powders in 1–2 mL of ethanol and adjusting the volume with distilled water. The control group was soaked in distilled water for 24 h. The seeds were soaked in the four different solutions for 24 h under laboratory conditions (approximately 23 ± 2 °C, RH of 40–50%). Subsequently, they were pre-treated with GA3 and rinsed thrice with distilled water, and 4 replicates containing 25 seeds were placed separately in plastic Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) on 1% agar medium, which were sealed with parafilm during incubation. After each GA3 soak, four replicates of all seeds were incubated for 4 weeks at 25/15 °C, as described above for a photoperiod of 12/12 h (light/dark) in a growth chamber.

2.7. Data Collection and Germination Trait Assay

Percent germination (radicle protrusion from seeds) was counted every 48 h for 7 weeks (temperature regime treatments) and 4 weeks (period of CS and pre-treatment with GA3) after sowing in a Petri dish. Each seed was considered to have germinated when the radicle protrusion reached a minimum of 2 mm, and then it was removed. To evaluate the germination process, biological parameters such as germination (G) and mean germination time (MGT) of the Campanulaceae seeds were calculated as follows [22]:

where N is the total number of seeds, T is the time in days from day 1 to the final day of the germination test, S is the total number of germinated seeds on day T, and G49 and 28 is the total number of seeds germinated on day 49 and 28 after sowing. The rate of germination was estimated using a modified Timson index (TGI) of germination velocity as follows [23]:

G (%) = G49 and 28/N × 100

MGT (days) = ∑ (T × S)/∑ S

Timson index (% day−1) = ∑ (G/t)

G is the total percentage of seeds germinated every 48 h, and t is the total germination period (28 days). A high value of the TI indicates a rapid germination velocity. The germination performance index (GPI) indicates the degree of germination uniformity. The seeds were calculated as follows [24]:

GPI = G/MGT

A high value of the GPI indicates more than uniform seed germination.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data on water absorption and germination characteristics were statistically analyzed using the SAS 9.4 software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the effect of factors on the G, MGT, Timson’s index, and GPI parameters, followed by Duncan’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05). Regression analysis and graphing were performed using SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics and Morphology of the Seed

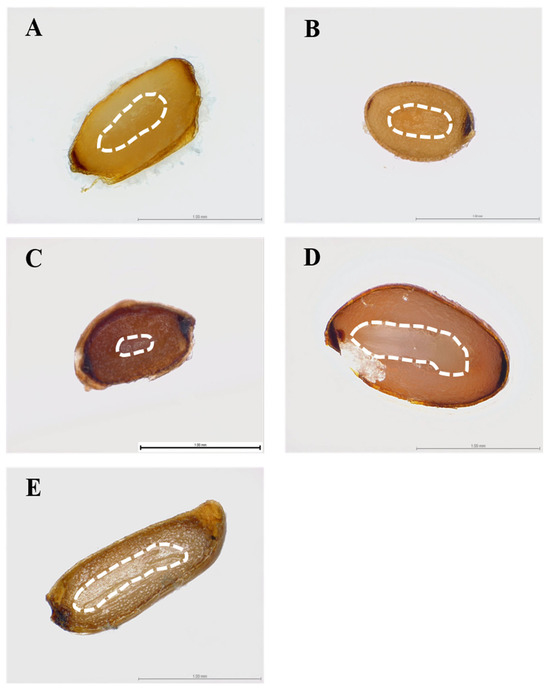

Campanulaceae seeds basic characteristics of length, width, and 1000-seed weight were as follows: A. triphylla (1.22 ± 0.03 mm, 0.73 ± 0.02, and 0.1748 ± 0.001 g), A. japonica (0.82 ± 0.02 mm, 0.63 ± 0.01 mm, and 0.1190 ± 0.002 g), C. punctata (1.05 ± 0.02 mm, 0.67 ± 0.04 mm, and 0.0577 ± 0.003 g), C. pilosula (1.37 ± 0.01 mm, 0.90 ± 0.01 mm, and 0.4803 ± 0.002 g), and L. sessilifolia (1.49 ± 0.05 mm, 0.99 ± 0.03 mm, and 0.2095 ± 0.001 g) (Table 1). During dispersal, the embryos of A. triphylla, A. japonicum, C. pilosula, and L. sessilifolia were fully developed, whereas the seeds of C. punctata had underdeveloped embryos. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Morphology and anatomy of the five Campanulaceae seed embryo. (A) A. triphylla, (B) A. japonicum, (C) C. punctata, (D) C. pilosula, (E) L. sessilifolia. Scale bar: 1.00 μm. White dotted line indicates the outline of the embryo.

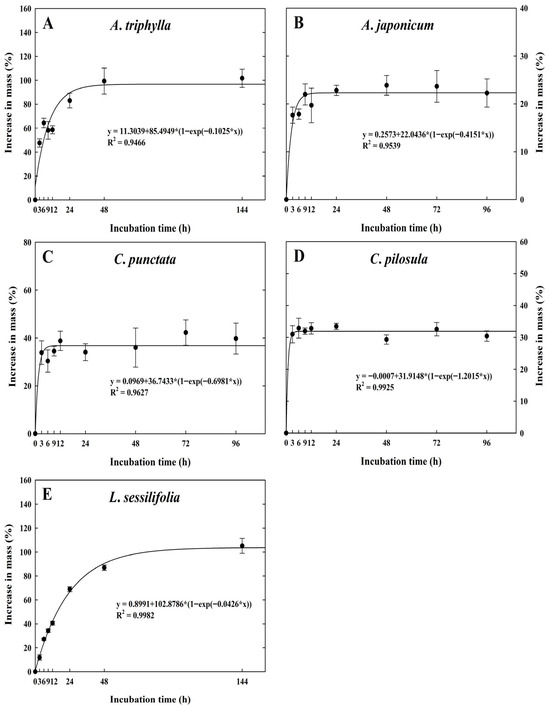

3.2. Water Imbibition Test

Campanulaceae seeds rapidly imbibed water within 24 h, with water uptake percentages relative to their initial dry seed mass as follows: A. triphylla (83.0 ± 6.2%), A. japonica (22.8 ± 1.1%), C. punctata (34.1 ± 3.5%), C. pilosula (33.4 ± 1.0%), and L. sessilifolia (68.9 ± 2.1%) (Figure 2A–E). Furthermore, the water imbibition of A. japonica (22.3 ± 2.9%), C. punctata (39.8 ± 6.4%), and C. pilosula (30.4 ± 1.6%) peaked after 96 h, with no further increase in seed mass thereafter. In contrast, the water imbibition of A. triphylla and L. sessilifolia seeds peaked at 101.7 ± 7.6% and 105.2 ± 6.3% after 144 h, respectively.

Figure 2.

Percentage increase in mass of Campanulaceae seeds during water incubation. The seeds were incubated at ambient temperature (approximately 23 ± 2 °C) on filter paper moistened with distilled water for 96 h or 144 h. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 4). (A) A. triphylla, (B) A. japonicum, (C) C. punctata, (D) C. pilosula, (E) L. sessilifolia.

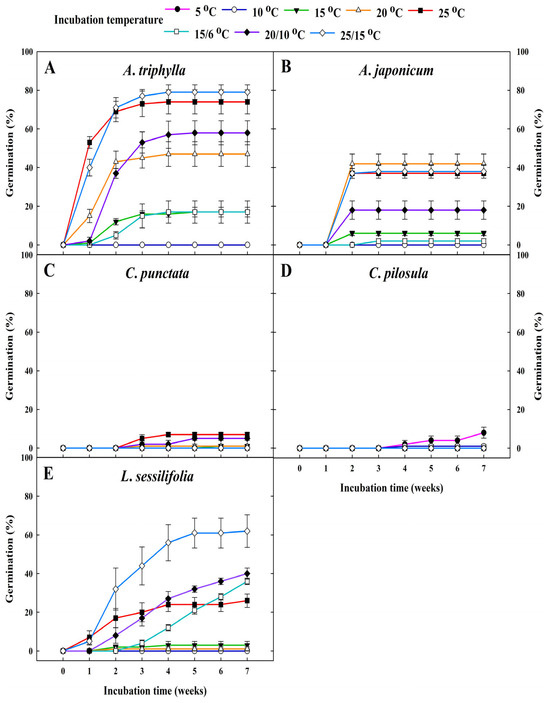

3.3. Effects of Temperature Regimes on Germinaiton

Seeds of most of the Campanulaceae species, including A. triphylla, A. japonica, and L. sessilifolia, began to germinate within 1–2 weeks (Figure 3A,B,E). Additionally, they exhibited a higher germination tendency at elevated temperatures (≥20 °C) than at lower temperatures. However, the germination of C. punctata and C. pilosula remained below 10.0% for up to 7 weeks after incubation (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Effects of constant temperature (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 °C) and fluctuating temperature regimes (15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C) on the cumulative germination of Campanulaceae seeds after 7 weeks of incubation. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 4). (A) A. triphylla, (B) A. japonicum, (C) C. punctata, (D) C. pilosula, (E) L. sessilifolia.

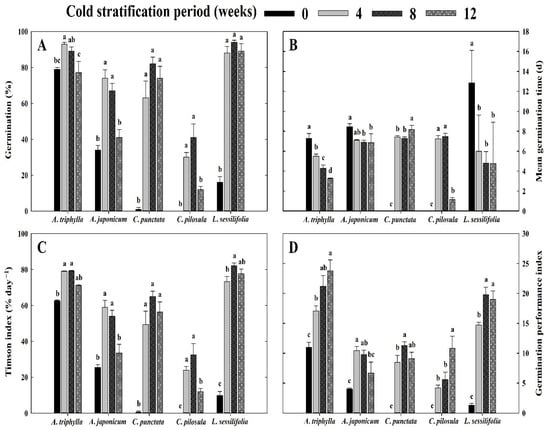

3.4. Effects of Cold Stratification Period on Germination

A significant effect of CS period (0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks) was observed on the germination of seeds incubated at 25/15 °C (Figure 4A). Seeds of A. triphylla germinated to 79.0% and 93.0% after 0 and 4 weeks of CS, respectively. Additionally, A. japonicum germinated at 34.0% without stratification when incubated at 25/15 °C, but the germination rate increased to 74.0% and 64.0% after 4 and 8 weeks of CS, respectively. Seeds of C. punctata and C. pilosula germinated to 1.0% and 0.0%, respectively, after 0 weeks of CS and to a maximum of 82.0 and 41.0%, respectively, after 8 weeks of CS, respectively. In the five species, the MGT ranged from 0 to 12.8 days, and seeds subjected to CS had lower MGT than those at 0 weeks of stratification (Figure 4B). In addition, the CS enhanced germination characteristics, such as germination velocity and uniformity across all species (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Effect of cold stratification period (0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks at 5 °C) on the germination traits of Campanulaceae seeds after 30 days of incubation at 25/15 °C. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 4). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences based on Duncan’s multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05). (A) germination, (B) mean germination time, (C) Timson index, (D) germination performance index.

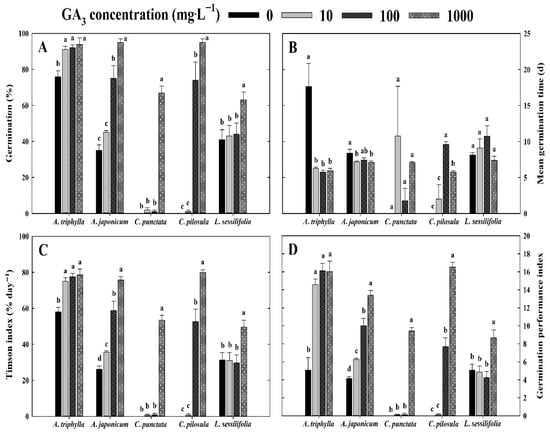

3.5. Effects of Pre-Treatment with GA3 Concentration on Germination

The germination of control seeds of A. triphylla, A. japonica, C. punctata, C. pilosula, and L. sessilifolia, soaked in distilled water for 24 h, was 76.0 ± 3.3%, 35.0 ± 3.0%, 0.0 ± 0.0%, 0.0 ± 0.0%, and 41.0 ± 5.5% under 30 days of incubation, respectively (Figure 5A). Pre-treatment with GA3 enhanced the germination of seeds of all five Campanulaceae species compared to the control group. Specifically, at a GA3 concentration of 1000 mg∙L−1, seed germination was significantly higher in four species, except in A. triphylla. The MGT of A. triphylla and A. japonicum seeds were shorter when pre-treated with GA3, compared to the control group; however, seeds of C. punctata and L. sessilifolia did not show a statistically significant difference among all treatments (Figure 5B). In addition, all species pre-treated with GA3 at 1000 mg∙L−1 had significantly enhanced germination characteristics, including germination velocity and uniformity (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Effects of gibberellic acid (GA3) pre-treatment (0, 10, 100, or 1000 mg∙L−1) on the germination traits of Campanulaceae seeds under 30 days of incubation. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 4). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences based on Duncan’s multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05). (A) germination, (B) mean germination time, (C) Timson index, (D) germination performance index.

4. Discussion

This study hypothesized that the seeds of the five Campanulaceae species would possess either PD or MPD, and that CS would be required to relieve dormancy. Our results were consistent with this hypothesis: none of the species exhibited PY, and the germination responses to temperature regimes, CS, and GA3 application supported classifications of non-deep PD or non-deep simple MPD for most species. These findings confirm that cold stratification plays a key role in dormancy release in the studied taxa.

Ecologically, physical dormancy (PY) in seeds with a thick coat or pericarp is an adaptive mechanism that regulates germination timing to coincide with favorable conditions during the plant life cycle. This dormancy type is characterized by seed coat or pericarp impermeability to water, which can be evaluated by testing water permeability—seeds showing more than a 20.0% increase in mass after 24 h of imbibition are considered water-permeable under natural conditions [25]. The seeds of the five Campanulaceae species gained over 20% in mass after 24 h of immersion in distilled water (Figure 2). Based on the presence of water-permeable seeds, we conclude that the five Campanulaceae species lack PY or combinational dormancy (PY + PD), as water-impermeable palisade layers within the seed or fruit coats typically cause PY. The substantial variation in water uptake among species likely reflects differences in testa structure, seed coat thickness, and the proportion of endosperm versus embryo tissues. Seeds with thinner or more porous testae (e.g., A. triphylla, L. sessilifolia) imbibed water rapidly and achieved higher mass increase, whereas species with denser or mechanically stronger seed coats (e.g., A. japonicum, C. pilosula) exhibited slower and lower overall imbibition. Such structural differences are frequently cited as drivers of species-specific imbibition kinetics in small-seeded taxa. Because initial seed moisture content was not determined, the values presented here represent relative mass increase rather than absolute moisture content at each time point, which is a commonly applied approach for small-seeded species in imbibition studies.

Seed size and embryo length can vary even within a single species, and the ratio of embryo to seed length (E:S) provides a useful measure of relative embryo size [26]. When the E:S ratio exceeds 0.5, the embryo is generally considered fully developed and linear in shape [27]. Seeds with underdeveloped or undifferentiated embryos often exhibit MD or MPD, requiring additional time for the embryo to reach the critical size necessary for radicle emergence [4,28]. Typically, this growth period can take up to approximately 30 days under favorable conditions, as reported for seeds exhibiting MD, during which embryo development and germination occur [29]. Although direct measurement of embryo size was not feasible due to Campanulaceae’s extremely small seed size, previous studies have noted that their seeds may contain either underdeveloped or fully developed embryos, often classified as miniature or micro (MA type) [17]. In the present study, four species—except for C. punctata—had fully developed embryos at dispersal, suggesting the absence of MD, whereas C. punctata had underdeveloped embryos, indicating the presence of MD.

Significant differences were observed in both the optimum temperature requirements and germination rates among the five Campanulaceae species (Figure 3). Optimal germination temperatures differ among plant species and are strongly influenced by their native habitats. In particular, seeds of wild plants from temperate regions are generally known to germinate best within the range of 24.0–30.0 °C [30]. In line with the findings of Koutsovoulou et al. [19], most Campanulaceae species germinate more effectively at relatively high temperatures, with the mean optimum germination temperature being ~20 °C. Among the five Campanulaceae species, the A. triphylla species exhibited 79.0% germination at 25/15 °C after 4 weeks of incubation, indicating the absence of dormancy in that species (Figure 3A). However, seeds of A. japonicum and L. sessilifolia exhibited approximately 40–60% germination at 20 °C and 25/15 °C after 4 weeks of incubation, indicating the presence of CD in these species (Figure 3B,E). CD represents a transitional stage within the dormancy-release continuum of seeds with non-deep PD, rather than a distinct dormancy class. In this state, seeds germinate only within a relatively narrow range of environmental conditions—most commonly temperature—before becoming fully ND. As dormancy is progressively alleviated, the temperature range permissive for germination gradually broadens until seeds reach a fully non-dormant state [31]. In the present study, L. sessilifolia seeds exhibited an increase in germination across a wider range of temperatures as time after incubation progressed, indicating a transition from dormancy to CD and finally to a non-dormant state. This pattern is consistent with the CD/ND cycle (i.e., D→CD↔ND), wherein seeds in the early stages of CD germinate to a high percentage only within a narrow temperature range. Among others, C. punctata and C. pilosula seeds exhibited low germination across all temperature regimes during 7 weeks of laboratory experiments, indicating that freshly dispersed seeds of these species are dormant (Figure 3C–D). Although C. punctata and C. pilosula were collected earlier in the fruiting season than the other species, only capsules exhibiting clear morphological indicators of full maturity—such as browning, drying, and natural dehiscence—were harvested to minimize the risk of including immature seeds. Therefore, insufficient seed development is unlikely to be the primary cause of the low germination observed under untreated temperature regimes. Nevertheless, slight interspecific differences in the timing of physiological maturity cannot be completely excluded. Importantly, both species exhibited marked improvements in germination following cold stratification and GA3 application, supporting the interpretation that physiological dormancy, rather than immaturity, was the major factor limiting germination in freshly collected seeds.

Approximately 70% of seed plants are estimated to produce dormant seeds, among which PD represents the most widespread type. Seeds with PD are water-permeable, but germination is inhibited by an internal physiological mechanism in the embryo that reduces its growth potential (or push power), thereby preventing the radicle from overcoming the mechanical resistance of the covering structures [4,32]. PD is generally divided into three levels (non-deep, intermediate, and deep) depending on the depth of dormancy and the seed’s response to dormancy-breaking treatments [29]. Seeds with non-deep PD are water-permeable, and excised embryos can produce normal seedlings; dormancy can be broken by cold or warm stratification, dry after-ripening, or chemical treatments such as GA3, ethylene, or potassium nitrate. Intermediate PD requires a longer period of CS, sometimes preceded by warm stratification, and responses to GA3 vary among species.

In contrast, seeds with deep PD do not respond to GA3, and excised embryos often fail to develop normal seedlings; in such cases, a prolonged period of cold or warm stratification is necessary to release dormancy [4,17]. In the present study, CS treatment had a positive effect on germination characteristics, including seed germination, MGT, Timson’s index (germination velocity), and germination performance index (germination uniformity), in four species except C. pilosula (Figure 4). In particular, in C. punctata, an 8-week cold stratification followed by incubation at 25/15 °C for 30 days effectively released seed dormancy, resulting in a germination percentage of 82.0%, compared with untreated seeds. In stratification experiments, the seed dispersal season in the native habitat is an important factor influencing dormancy release. Among the species used in the present study, seeds are typically dispersed during autumn and generally overcome dormancy through CS. In temperate ecosystems, seeds dispersed in autumn commonly remain dormant over winter, during which, exposure to cold and moist conditions releases dormancy, thereby allowing germination in the following spring. This seasonal dormancy–germination cycle is an adaptive strategy for synchronizing seedling emergence with favorable environmental conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated that autumn-dispersed species of Campanulaceae exhibit significantly enhanced dormancy release and germination rates following CS pre-treatment [10,20,33].

In the present study, GA3 treatment significantly promoted seed germination across all Campanulaceae species examined, demonstrating its effectiveness as a dormancy-breaking treatment (Figure 5). GAs not only promote germination by counteracting the inhibitory effects of abscisic acid (ABA) but also play a key role in alleviating seed dormancy [34]. The application of GAs, particularly GA3, has been widely employed to overcome non-deep or intermediate PD and MPD, as they can rapidly break dormancy and promote germination. In the Campanulaceae family, previous studies have similarly reported that GA3 treatment effectively enhanced germination rates and alleviated dormancy in several species. For instance, Kim et al. [20] reported that Campanula takesimana seeds exhibited significantly improved germination percentages when pre-treated with 1000 mg·L−1 GA3, indicating the presence of non-deep, simple MPD. Similarly, Paradisiotis et al. [35] found that C. pangea seeds showed increased germination across a broader temperature range following GA3 treatment, suggesting non-deep PD. Studies on Jasione supina have also indicated that GA3 application can substitute for CS, effectively breaking dormancy and promoting germination [36]. These findings collectively highlight the efficacy of GA3 in facilitating seed germination and overcoming dormancy in Campanulaceae species, underscoring its potential application in conservation and propagation efforts for these plants.

Table 2 summarizes the dormancy classes and germination responses of the five Campanulaceae species and clearly illustrates the species-specific patterns obtained in this study. In particular, the table highlights the distinct effects of temperature, cold stratification, and GA3 on germination capacity, which were central to determining the final dormancy classification. For A. japonicum, C. pilosula, and L. sessilifolia, germination increased markedly at higher temperature regimes following cold stratification or GA3 application, indicating an expansion of the upper temperature limit for germination—a diagnostic characteristic of non-deep PD Type I. In contrast, C. punctata displayed underdeveloped embryos and required dormancy-breaking treatment, supporting its classification as non-deep simple MPD. A. triphylla germinated readily under warm conditions without stratification, consistent with non-dormancy (ND). These species-level distinctions, synthesized in Table 2, provide a coherent dormancy framework for Campanulaceae and offer practical implications for propagation and conservation. Such integrative interpretation enhances our understanding of seed eco-physiology and contributes to improving restoration strategies under shifting environmental conditions.

Table 2.

Summary of seed dormancy and germination characteristics of Campanulaceae species.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that seeds of five wild Campanulaceae species possessed intact but water-permeable seed coats and did not exhibit PY. Seeds of A. triphylla possessed fully developed embryos and showed sufficient germination within 30 days at relatively high temperatures (≥20 °C), indicating the absence of dormancy. In contrast, seeds of A. japonicum, C. pilosula, and L. sessilifolia also had fully developed embryos, but their germination was promoted by short periods of CS or GA3 treatment, classifying them as type I non-deep PD. Further, seeds of C. punctata had underdeveloped embryos, and germination was promoted by short periods of CS or GA3 treatment, suggesting that this species exhibits non-deep simple MPD. This study offers important insights for the mass propagation of Campanulaceae seedlings and highlights the need for further research to classify dormancy types in unexamined species. Such knowledge will contribute to a deeper understanding of eco-physiological mechanisms under diverse environmental conditions and to establishing practical propagation protocols.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.K., J.H.K. and C.S.N.; methodology, H.M.K.; formal analysis, H.M.K. and J.H.K.; investigation, H.M.K., J.H.K., J.Y.P. and G.M.K.; resources, H.M.K., J.H.K., J.H.L. and M.H.L.; data curation, H.M.K. and J.H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.K. and J.H.K.; writing—review and editing, H.M.K. and J.H.K.; supervision, C.S.N.; project administration, C.S.N.; funding acquisition, C.S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. RS-2021-KF001796, Project No. RS-2025-02253003) provided by the Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.H.L. and M.H.L. for assistance with seed collection and observation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Cold stratification |

| GA3 | Gibberellic acid |

| PD | Physiological dormancy |

| MD | Morphological dormancy |

| MPD | Morphophysiological dormancy |

| PY | Physical dormancy |

| PY + PD | Physical dormancy + Physiological dormancy |

| CD | Conditional dormancy |

| ND | Non-dormancy |

References

- Bano, H.; Rather, R.A.; Bhat, J.I.; Bhat, T.T.; Azad, H.; Bhat, S.A.; Hamid, F.; Bhat, M.A. Effect of pre-sowing treatments using phytohormones and other dormancy breaking chemicals on seed germination of Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. ex Griseb: An endangered medicinal plant species of north western Himalaya. Eco Environ. Cons. 2021, 27, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chahtane, H.; Kim, W.; Lopez-Molina, L. Primary seed dormancy: A temporally multilayered riddle waiting to be unlocked. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chien, C.; Chung, J.; Yang, Y.; Kuo, S. Dormancy-break and germination in seeds of Prunus campanulata (Rosaceae): Role of covering layers and changes in concentration of abscisic acid and gibberellins. Seed Sci. Res. 2007, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Walck, J.L.; Tao, J. Non-deep simple morphophysiological dormancy in seeds of Angelica keiskei (Apiaceae). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 255, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Loaiza, V.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Fernandes, E.; Custódio, L. A comparative study of the influence of soil and non-soil factors on seed germination of edible salt-tolerant species. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, B.; Ansari, R.; Flowers, T.J.; Khan, M.A. Germination strategies of halophyte seeds under salinity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Née, G.; Xiang, Y.; Soppe, W.J. The release of dormancy, a wake-up call for seeds to germinate. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 35, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.K.; Park, K.T.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Song, S.K.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, C.H.; Cho, J.S. Comparison of the seed dormancy and germination characteristics of six Clematis species from South Korea. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 307, 111488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Yoshinaga, A. Morphophysiological dormancy in seeds of six endemic lobelioid shrubs (Campanulaceae) from the montane zone in Hawaii. Can. J. Bot. 2005, 83, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, Q.; He, Z.H. Two faces of one seed: Hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Qanmber, G.; Li, F.; Wang, Z. Updated role of ABA in seed maturation, dormancy, and germination. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 35, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kildisheva, O.A.; Dixon, K.W.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Chapman, T.; Di Sacco, A.; Mondoni, A.; Turner, S.R.; Cross, A.T. Dormancy and germination: Making every seed count in restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, S256–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, K.; Soltani, E.; Arabhosseini, A.; Aghili Lakeh, M. A quantitative analysis of primary dormancy and dormancy changes during burial in seeds of Brassica napus. Nord. J. Bot. 2021, 39, e03281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, S.; King, J. Towards a systems biology approach to understanding seed dormancy and germination. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 3561–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkis, D.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Rønsted, N. Seed dormancy and germination of the endangered exceptional Hawaiian lobelioid Brighamia rockii. Appl. Plant Sci. 2022, 10, e11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienbacher, E.; Navarro-Cano, J.A.; Neuner, G.; Erschbamer, B. Seed dormancy in alpine species. Flora 2011, 206, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsovoulou, K.; Daws, M.I.; Thanos, C.A. Campanulaceae: A family with small seeds that require light for germination. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, G.M.; Lee, M.H.; Park, C.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.M.; Na, C.S. Dormancy-release and germination improvement of Korean bellflower (Campanula takesimana Nakai), a rare and endemic plant native to the Korean peninsula. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. World Flora Online. 2025. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Ellis, R.H.; Roberts, E.H. Improved equations for the prediction of seed longevity. Ann. Bot. 1980, 45, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Gul, B. High salt tolerance in germinating dimorphic seeds of Arthrocnemum indicum. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1998, 159, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, F.J.; Reader, R.B.; Edwards, R.L. Effect of seed treatment and planting method on Tabasco pepper. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1987, 112, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. When breaking seed dormancy is a problem: Try a move-along experiment. Nat. Plants J. 2003, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelook, F.; Bolle, N.; Van Assche, J.A. Seed dormancy and germination of the European Chaerophyllum temulum (Apiaceae), a member of a trans-Atlantic genus. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. A revision of Martin’s seed classification system, with particular reference to his dwarf-seed type. Seed Sci. Res. 2007, 17, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walck, J.L.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds of Thalictrum mirabile (Ranunculaceae) require cold stratification for loss of nondeep simple morphophysiological dormancy. Can. J. Bot. 1999, 77, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.T.; Kester, D.E.; Davies, F.T.; Geneve, R.L. Plant Propagation: Principles and Practices, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, E.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. A graphical method for identifying the six types of non-deep physiological dormancy in seeds. Plant Biol. 2017, 19, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. The natural history of soil seed banks of arable land. Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidou, T.N.; Anestis, I.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Krigas, N. GIS bioclimatic profile and seed germination of the endangered and protected Cretan endemic plant Campanula cretica (A. DC.) D. Dietr. for conservation and sustainable utilization. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, P.; Zhou, T.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. Exogenous gibberellin weakens lipid breakdown by increasing soluble sugars levels in early germination of zanthoxylum seeds. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisiotis, M.; Pipinis, E.; Kostas, S.; Tsoktouridis, G.; Hatzilazarou, S.; Mastrogianni, A.; Tsiripidis, I.; Krigas, N. Seed germination requirements of the threatened local Greek endemic Campanula pangea hartvig facilitating species-specific conservation efforts. Conservation 2025, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, S.; Arslan, H.; Güleryüz, E.; Güleryüz, G. Breaking of dormancy in the narrow endemic Jasione supina Sieber subsp. supina (Campanulaceae) with small seeds that do not need light to germinate. Acta Bot. Croatica 2021, 80, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. The great diversity in kinds of seed dormancy: A revision of the Nikolaeva-Baskin classification system for primary seed dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2021, 31, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).