Abstract

Leaf photosynthesis plays an important role in maize growth and yield components due to its involvement in dry matter partitioning and organ formation. Nevertheless, how varying planting patterns affect maize leaf photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and subsequently maize yield remains poorly understood, particularly at various nitrogen rates. A two-season field experiment was performed on rainfed maize in 2021 and 2022 to explore the responses of photosynthetic physiological characteristics, leaf N and chlorophyll contents, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, grain yield and water productivity to various planting patterns and N rates. The experiment included six planting patterns, i.e., flat planting without mulching (CK), flat planting with straw mulching (SM), ridge mulched with transparent film and furrow without mulching (RP1), flat planting with full transparent film mulching (FM1), ridge mulched with black film and furrow without mulching (RP2), and flat planting with full black film mulching (FM2). Additionally, there were two nitrogen rates, i.e., 0 kg N ha−1 (N0) and 180 kg N ha−1. The results showed that nitrogen application significantly improved leaf physiological characteristics. Under various planting patterns, leaf photosynthetic pigments, leaf area duration, leaf nitrogen content, QYmax and ΦPSII ranked as RP2 > RP1(FM2) > FM1 > SM(CK) in 2021, and RP2(RP1) > FM1(FM2) > SM(CK) in 2022. No significant variations were observed in water productivity (WP) among different film colors, with overall performance of RP2(FM2) > RP1(FM1) > SM > CK. WP significantly improved by 36.14% and 25.15% under N1 compared to N0 in 2021 and 2022, respectively. This pattern paralleled the fluctuation in water consumption intensity. Compared to CK, RP significantly increased leaf nitrogen content (29.3%), total Chl content (16.0%), QYmax (6.39%), ΦPSII (32.01%), and net photosynthesis rate (14.2%), thereby significantly improving grain yield (46.35%) and WP (27.69%), while reducing evapotranspiration (6.84%). Yield performance ranked as RP2 > (RP1 and FM2) > FM1 > SM > CK in 2021 and RP2 > RP1 > (FM1 and FM2) > SM > CK in 2022. Overall, RP2N1 obtained the highest principal component scores in both years, suggesting great potential to improve leaf photosynthetic physiological characteristics, thereby increasing grain production and ensuring food security in rainfed maize cultivation areas.

1. Introduction

Approximately 41% of the world’s arable land is located in the arid and semi-arid regions, producing 44% of the global food supply and sustaining nearly 2.5 billion people who rely directly on these agro-ecosystems [1]. However, the increasing severity of extreme climatic conditions and the frequent occurrence of droughts in these regions pose significant challenges. Global climate change, primarily driven by human activities, has resulted in erratic precipitation patterns and a mismatch between precipitation and crop water storage across various parts of the world [2]. Consequently, food production instability has heightened, particularly in semi-humid but drought-prone regions. In China, dryland areas constitute approximately 60% of the total cultivated land, playing a critical role in ensuring national food security [3]. This situation presents a considerable challenge for dryland agriculture to implement effective management measures successfully. To achieve consistently high crop yields and secure the long-term food security in China, it is essential to address these challenges, especially in semi-humid but drought-prone regions.

Field management practices such as film mulching and planting patterns are vital in this regard [4]. Film mulching has gained wide acceptance due to its advantages, such as reducing soil evaporation, increasing soil temperature, and enhancing crop yield and water use efficiency (WUE). Additionally, it facilitates seed germination and protects the crop against low-temperature freezes [5]. Film mulching creates a favorable microclimate at the soil surface, enhancing the photosynthetic capacity of crops by increasing air resistance and sunlight reflectivity [6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that film mulching significantly boosts chlorophyll content [7], Rubisco enzyme activity, and the photosynthetic rate compared to non-mulched conditions [8]. In arid and semi-arid regions, both ridged-furrow mulching (RF) and flat mulching have been employed to improve runoff efficiency, facilitate soil infiltration, reduce soil evaporation, and enhance precipitation utilization and crop yield [9]. Different mulching practices and planting patterns yield distinct photosynthetic capacities and resource use efficiencies compared to traditional flat planting without mulching, as these techniques provide crops with varying levels of soil moisture, temperature, and other field environmental conditions [10].

Nitrogen fertilization plays a vital role in crop management, significantly enhancing both growth and yields. This practice is directly associated with improved leaf photosynthetic efficiency and can positively influence chlorophyll fluorescence metrics, including Fv/Fo, ΦPSII, the maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), and the photochemical quenching coefficient (qP) [11,12]. Nonetheless, research examining the interplay between nitrogen fertilization, irrigation, and their effects on maize photosynthesis and chlorophyll levels has primarily targeted broader trends, often neglecting the critical variations in how these parameters respond to nitrogen and water stress across different growth phases. Consequently, it is essential to investigate how diverse planting strategies and nitrogen application rates affect photosynthesis and chlorophyll content at various stages of maize development to better inform practices in rainfed maize production.

Leaf photosynthesis is essential for the development and yield components of crops, as it plays a critical role in the partitioning of dry matter and the formation of plant organs [13]. Chlorophyll is integral to the effective process of photosynthesis in plants, with chlorophyll fluorescence measurements acting as important indicators of photosynthetic activity, particularly in terms of how photosystem II (PSII) utilizes excitation energy [14]. The ability of chlorophyll to efficiently transfer absorbed light energy to PSII significantly affects the assimilative capacity of maize, which is influenced by the dynamics of electron transfer and photochemical processes, as revealed by various fluorescence metrics [15,16]. Environmental stresses related to water availability and temperature markedly affect both leaf photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence [17]. Previous investigations have demonstrated that water scarcity can hinder maize growth, diminish the accumulation of photosynthetic yield, and lead to substantial declines in overall crop yields [18]. Moreover, water shortages restrict photosynthetic processes, causing reductions in chlorophyll levels (Chl), net photosynthetic rates (Pn), transpiration rates (Tr), and the efficiency of PSII photochemistry [19]. Understanding the mechanisms behind photosynthetic physiological responses is crucial for deciphering maize’s physiological reactions, improving water management strategies, and optimizing various planting patterns. Prior research on different mulching and planting patterns has mainly focused on soil utilization practices, nutrient uptake mechanisms, and the effects of soil hydrothermal conditions [20]. However, there remains a lack of research that examines how combining soil mulching with planting patterns and nitrogen application affects the photosynthetic physiological responses of rainfed maize. This study aims to (1) evaluate the effects of varying planting patterns and nitrogen fertilization on leaf growth and physiological characteristics during varying stages of maize development, (2) explore the relationships between nitrogen content in maize leaves and their physiological and functional traits across various planting patterns and nitrogen rates, and (3) identify the most effective practices for enhancing both water use efficiency and grain yield in rainfed maize systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Experimental Site

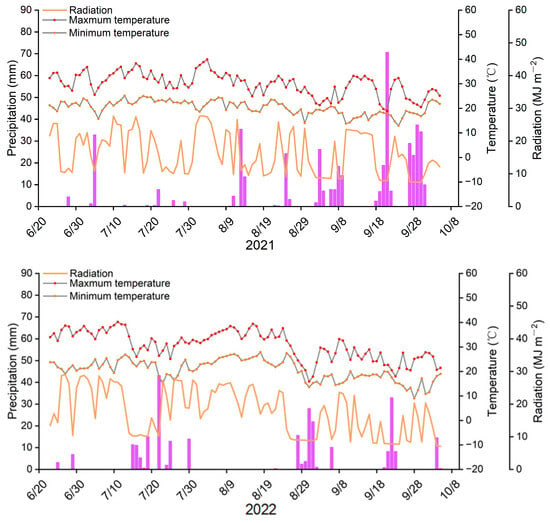

The experiment was conducted from June to September in both 2021 and 2022 at the Water-saving Irrigation Experimental Station, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China. The experimental station is situated in a typical semi-humid but drought-prone area at coordinates 108°24′ E, 34°20′ N, with an elevation of 524.7 m. Precipitation in this region has shown significant year-to-year variations from 1995 to 2020, with a mean annual precipitation of 595 mm. On average, 61% of the annual precipitation occurred between July and September. The soil in the experimental area was loamy clay, with a water-holding capacity of 21% (gravimetric) in the 0–100 cm soil layer, a wilting coefficient of 8.5% (gravimetric), a mean dry bulk density of 1.58 g cm−3 and a soil pH of 8.14. The concentrations of NO3−-N, NH4+-N, available phosphorus, and available potassium were 20.06 mg kg−1, 7.70 mg kg−1, 20.9 mg kg−1, and 160.8 mg kg−1, respectively. During the maize-growing seasons of 2021 and 2022, the total rainfall was 460.5 mm and 275.1 mm, respectively (Figure 1). The summer maximum temperatures in both years were around 30 °C, and the minimum temperatures remained at approximately 20 °C. However, in 2022 the overall fluctuations were more stable, with certain periods slightly higher than those in 2021, especially from late July to mid-to-late August. In contrast, 2021 showed more frequent fluctuations, with multiple instances of sudden rises or drops. Considering the mean seasonal rainfall of 340.7 mm recorded from 1995 to 2014, the maize growing season in 2021 was classified as a wet year (35.2%), while 2022 was classified as a dry year (−19.3%). And both years’ meteorological data are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Daily maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation during the growing seasons of dryland summer maize in 2021 and 2022. The planting dates for both years were 20 June, and the harvest dates were 2 October.

2.2. Experimental Design

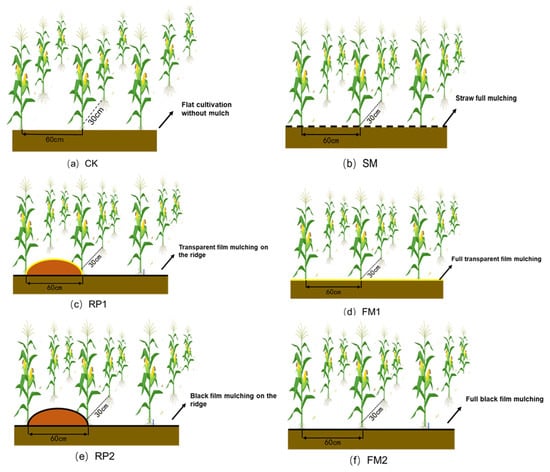

Six planting patterns were established: (1) CK: flat planting without mulching (Figure 2a); (2) SM: flat planting with straw mulching (Figure 2b); (3) FM1: flat planting with full transparent film mulching (Figure 2c); (4) RP1: ridge mulched with transparent film and furrow without mulching (Figure 2d); (5) FM2: flat planting with full black film mulching (Figure 2e); and (6) RP2: ridge mulched with black film and furrow without mulching (Figure 2f). The planting patterns are demonstrated in Figure 2. Additionally, there were two nitrogen application rates: N0: 0 kg N ha−1 and N1: 180 kg N ha−1. Previous studies at this site identified 180 kg N ha−1 as the economically optimal nitrogen rate that prevents N limitation during tasseling; accordingly, we used 180 kg N ha−1 [21]. This led to the establishment of a total of 12 experimental treatments, with each treatment replicated three times, resulting in 36 experimental plots altogether. Each plot measured 7.5 m in length and 5.4 m in width, organized in a randomized block arrangement. The ridge-furrow planting system featured an alternating pattern of ridges and furrows. Before planting, the ridges and furrows were constructed, with the ridges designed to have a width of 60 cm and a height of 15 cm, covered by plastic film. Summer maize was subsequently sown at the base of the ridges. A planting density of 56,000 plants per hectare was achieved, with rows spaced 60 cm apart and plants placed 30 cm apart within each row. Soil mulching utilized both black and transparent polyethylene film, each measuring 80 cm wide and 0.008 mm thick. Furthermore, straw mulching was implemented using sun-dried wheat straw from the previous year’s harvest, which was cut into uniform pieces measuring between 10 and 20 cm. A total mulching volume of 4500 kg per hectare was evenly distributed across the experimental plots. As basal fertilizers, urea (nitrogen content ≥ 46.0%), calcium superphosphate (120 kg P2O5 per hectare, P2O5 ≥ 16.0%), and potassium sulfate (60 kg K2O per hectare, K2O ≥ 51.0%) were utilized synchronized with sowing. Prior to planting, all experimental plots were tilled to a depth of 30 cm. Furthermore, furrows were manually formed to a depth of 15 cm to allow for the strip application of fertilizers. Maize was sown on 20 June and harvested on 2 October in both the 2021 and 2022 growing seasons. In 2021, no irrigation was provided throughout the maize growth period, whereas in 2022, an additional 30 mm of water was supplied during the seedling stage to alleviate drought conditions affecting germination. Other agronomic practices adhered to the standard management guidelines followed in the region.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the experimental planting mode for maize. (a) CK: flat planting without mulching; (b) SM: flat planting with straw mulching; (c) RP1: monopoly covered with transparent film and furrow without mulching; (d) FM1: flat planting with full transparent film mulching; (e) RP2: monopoly with black film and furrow without mulching; (f) FM2: flat planting with full black film mulching.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Leaf Nitrogen Content

Leaf samples were taken at the V3, V6, R1, R3, and R6 growth stages to analyze the nitrogen content in maize leaves. The samples were initially dried in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min, followed by drying at 75 °C until they reached a stable weight. Once dried, the samples were ground to pass through a 0.5 mm sieve and digested with H2SO4-H2O2 for nitrogen analysis. The Kjeldahl method was employed to determine the leaf nitrogen content. To calculate leaf nitrogen uptake, the total dry weight of the leaves was multiplied by the nitrogen content.

2.3.2. Chlorophyll Content

At the grain-filling stage, spike leaves were collected from each treatment, removing the large main veins. About 0.1 g of the leaves was placed in a 25 mL centrifuge tube, sealed with 20 mL of 95% ethanol, and kept in the dark for 24–36 h until the tissue turned white. Subsequently, colorimetry was performed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV2600, Shimadzu Corporation, Kanda Nishiki-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo) at wavelengths of 663 nm, 645 nm, and 470 nm. The concentrations (mg L−1) of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), total chlorophyll (Chl: Chl a + Chl b), and carotenoids (Car) were calculated based on the optical density (OD) values at each wavelength, as described by Li [22].

2.3.3. Photosynthesis Parameters

Measurements were obtained from the uppermost leaves of the canopy during the R1 period and the spike leaves during the R3 and R6 periods using the LI-6800 portable photosynthesis system (Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). And the measured leaves were fully expanded, healthy leaves at the same leaf position on each plant, which ensured similar leaf height, age, and exposure conditions across all treatments. A light intensity of 1500 μmol m−2 s−1, a leaf chamber temperature 27 °C, and a relative humidity 60% were maintained, along with a CO2 concentration set at 400 μmol m−2 s−1 on a cloudless morning (9:00–11:00). The photosynthetic parameters assessed included the rate of photosynthesis (Pn), transpiration rate (Tr), stomatal conductance (gsw), and intercellular carbon dioxide concentration (Ci). Additionally, stomatal limitation (Ls) and instantaneous water use efficiency (WUEi) were calculated using these measured parameters:

2.3.4. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

Fully expanded maize leaves were collected at approximately 20:30 after a 30-min dark adaptation. From each plot, three fully expanded leaves were sampled as biological replicates. These leaves were measured using the FluorCam Fluorescence Imaging System (PSI, Drásov, Czech Republic). Care was taken to avoid capturing the venation of the maize leaves while preserving the integrity of the leaf borders. Fluorescence measurements in the fully dark-adapted state were taken after at least two hours of dark adaptation. The leaves were irradiated with weak modulated light (light intensity of about 0.1 μmol m−2 s−1), and the resulting fluorescence was noted as Fo (minimum fluorescence). Then, the leaves were exposed to a saturated light flash (light intensity of about 3000 μmol m−2 s−1), and the fluorescence measured at this time was termed maximum fluorescence, Fm. The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were calculated as follows:

where QYmax is the maximum PSII quantum yield, ΦPSII is the effective PSII quantum yield, qP is the steady-state light-adapted photochemical quenching, NPQ is the nonphotochemical quenching coefficient, Ft is the maximum fluorescence Fm, is the minimum fluorescence under light adaptation, and is the maximum fluorescence under light adaptation.

2.3.5. Grain Yield

During the maize harvesting period in both 2021 and 2022, 20 representative maize plants were randomly selected from each plot. The plants were air-dried to a moisture content of 14% before being threshed. The weight of the kernels was measured to calculate the kernel grain yield.

2.3.6. Crop Evapotranspiration and Water Productivity

Crop evapotranspiration (ET) was estimated by the water balance method:

where P is rainfall amount (mm), U is groundwater recharge (mm), I is irrigation amount (mm), R is surface runoff (mm), D is deep seepage (mm), and ∆W corresponds to the variation in soil water storage (0–200 cm) before sowing and after harvesting (mm). The experimental plot was flat, and runoff loss was prevented by ridges surrounding the entire area. It was located in a region where the groundwater depth exceeded 50 m, which resulted in no groundwater recharge. Additionally, over-irrigation was avoided, and the soil wetting depth remained less than 2 m. Consequently, U, R, and D were considered negligible. Therefore, Equation (7) was simplified to:

The crop water productivity (WP, kg kg−1) was calculated using the following formula:

The water consumption intensity (CS, mm d−1) was calculated according to the following formula:

where D is the number of days for the whole growth period (d).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Prior to ANOVA, the data were tested to ensure that they met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated using Levene’s test. When these assumptions were satisfied, a one-way or two-way ANOVA was conducted as appropriate. Duncan’s multiple range test was employed as the post-hoc procedure to compare treatment means, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Different lowercase letters in the tables and figures indicate significant differences among treatments. The ANOVA model included planting mode (P) and nitrogen rate (N) as fixed main effects, and their interaction was analyzed as P × N. Graphical representations were generated using Origin 2023 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out in Origin 2023 to evaluate the integrated effects of planting modes and nitrogen application rates on leaf nitrogen content, grain yield, total chlorophyll content (Chl), net photosynthetic rate (Pn), water productivity (WP), maximum quantum yield of PSII (QYmax), chlorophyll content per unit leaf area (CS), and stomatal limitation (Ls). Correlations among these variables were analyzed in Origin 2023 using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

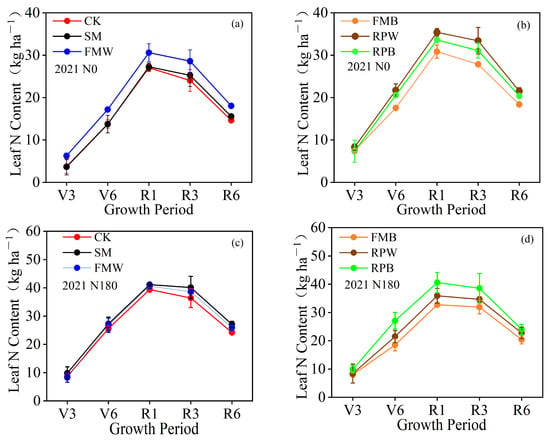

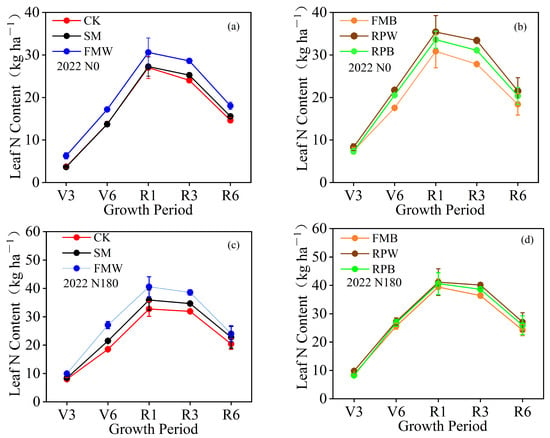

3.1. The Efffects of Different Planting Modes with Nitrogen Application on Leaf Nitrogen Content

Throughout the entire growth period, leaf nitrogen content was generally higher in 2021 compared to 2022 (Figure 3 and Figure 4). In both years, leaf nitrogen content rose initially before gradually declining, reaching its maximum levels at the R1 stage. In 2021, there was a sharp decline from R1 to R3, whereas in 2022, the decline was more gradual from R1 to R3. Nitrogen application significantly enhanced leaf nitrogen content at all growth stages (p < 0.01). Planting mode significantly contributed to leaf nitrogen content (p < 0.05), which significantly increased the maximum leaf nitrogen content by 46.0% in RP2, 57.4% in FM2 and 60.2% in FM1 in 2021, and by 12.6%, 15.2% and 11.2% in 2022, compared to CK, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effects of different mulching practices and N treatments on maize leaf N content in 2021 (a–d). Bars are the means ± standard deviation (n = 3). V3 is maize vegetative growth with three leaves. V6 is maize vegetative growth with six leaves. R1 is silking stage of maize. R3 is milking stage of maize. R6 is maturity stage of maize.

Figure 4.

Effects of different mulching practices and N treatments on maize leaf N content in 2022 (a–d). Bars are the means ± standard deviation (n = 3). V3 is maize vegetative growth with three leaves. V6 is maize vegetative growth with six leaves. R1 is silking stage of maize. R3 is milking stage of maize. R6 is maturity stage of maize.

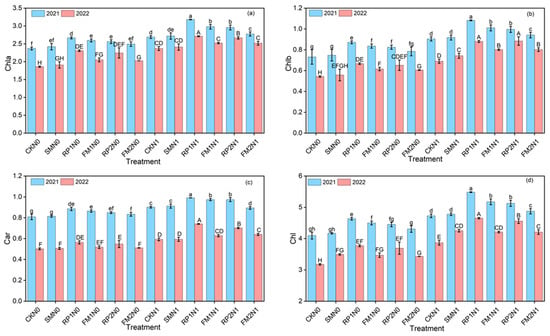

3.2. The Efffects of Different Planting Modes with Nitrogen Application on Chlorophyll Content

There were significant annual variations in Chl, Chla, Chlb, and Car, which decreased by 9.4%, 19.2%, 12.0%, and 12.5% in 2022 compared to 2021, respectively (Figure 5). Nitrogen application substantially enhanced the content of photosynthetic pigments, resulting in increases of 18.3%, 14.8%, 26.6%, and 13.45% in Chl, Chla, Chlb, and Car compared to N0, respectively. The planting mode also exhibited a significant impact on photosynthetic pigment content. The R2N1 had the highest Chl, Chla, Chlb, and Car among all treatments. In 2021, the contents of chlorophyll a (Chla), chlorophyll b (Chlb), carotenoids (Car), and total chlorophyll (Chl) were observed in the following hierarchy: RP2 > (RP1 and FM2) > FM1 > (SM and CK). This ranking shifted in 2022 to (RP2 and RP1) > (FM2 and FM1) > (SM and CK), with no significant differences found among the treatments grouped within parentheses. Compared to CK, RP2, RP1, and FM2 caused the most significant increases in Chlb content, followed by Chl content. In 2021, these treatments resulted in increases of 18.4%, 12.2%, and 10.7% in Chlb content, and 14.7%, 9.7%, and 8.6% in Chl content, respectively. In 2022, the increases were even more considerable, with Chlb content increasing by 28.2%, 14.0%, and 25.0%, and Chl content by 27.0%, 12.4%, and 23.6%, respectively.

Figure 5.

Chlorophyll a (Chla) (a), chlorophyll b (Chlb) (b), carotenoids (Car) (c), and total chlorophyll (Chl) (d) levels in different treatments in 2021 and 2022. Vertical bars represent the standard error (SE). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments in 2021 (p < 0.05), while different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments in 2022 (p < 0.05).

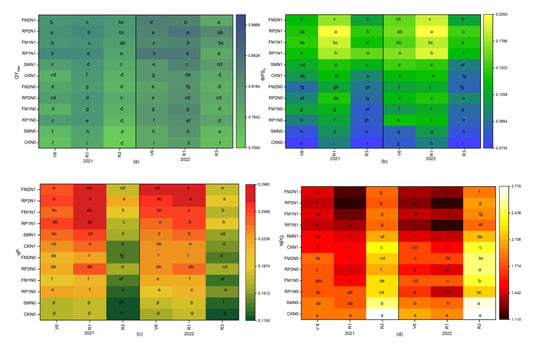

3.3. The Efffects of Different Planting Modes with Nitrogen Application on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

The maximum quantum yield (QYmax) of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry and the effective quantum yield (ΦPSII) exhibited similar patterns across both growing seasons, as illustrated in Figure 6. Over two seasons, both QYmax and ΦPSII increased initially and then declined as the growing period progressed. Nitrogen application significantly increased both QYmax and ΦPSII compared to no nitrogen application. In comparison to CK, RF (ridge-furrow planting) and FP (flat planting with film mulch) significantly increased QYmax. Additionally, both film mulching (FM) and ridge planting (RP) significantly increased QYmax compared to straw mulching (SM) and no mulching (CK), and there were no significant differences between various film color treatments. For ΦPSII, subtle differences were noted among the planting patterns during each growth period. At the main growth stages (R1 and R3), the pattern was ordered as: (RP2 and RP1) > (FM1 and FM2) > SM > CK. Compared to CK, RP2, FM1, and SM increased by 27.4%, 18.7%, and 10.2% respectively. During the R1 and R3 stages, different film colors did not lead to significant differences. In 2022, while RP2 and FM1 showed no significant difference, noteworthy disparities were identified among other treatments. The maximum QYmax, ΦPSII, and qP were obtained in the RP2N1 treatment throughout the entire growth period. In 2021, the qP at the R1 stage followed the order: RP1 > RP2 (FM1, FM2) > SM > CK. Compared to CK, the qP increased by 4.38% for SM, 20.57% for RP1, and 32.17% for RP2. Over the two seasons, NPQ exhibited a decreasing trend followed by an increasing trend throughout the growth period, reaching its lowest value at the R3 stage. The order of NPQ values was: CK > SM > FM > RP. Nitrogen application significantly reduced the non-photochemical quenching coefficient in both years. The smallest NPQ was observed in the RP2N1 treatment throughout the whole growth period.

Figure 6.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (QYmax (a), ΦPSII (b), qP (c), NPQ (d)) at the V6, R1 and R3 stages under different treatments. Data are presented as mean values ± SE (n = 3). Different lower-case letters denote significant differences at p < 0.05 among treatments.

3.4. The Efffects of Different Planting Modes with Nitrogen Application on Photosynthetic Parameters

The net photosynthetic rate (Pn) serves as a vital indicator of the physiological characteristics of maize under different planting modes and nitrogen application treatments throughout the entire growth period (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Both years demonstrated a unimodal trend in net photosynthesis rate (Pn), which initially rose and subsequently declined, peaking at the R1 stage. Notably, the net photosynthetic rate was higher in 2021 than in 2022. The nitrogen application, planting mode, and their interaction had a significant impact on Pn, gsw, Ci, Tr, and Ls throughout the entire growth period in both 2021 and 2022 (p < 0.05). The application of nitrogen and the planting mode had a significant impact on water use efficiency (WUEi) (p < 0.05), although their interaction did not significantly influence WUEi (p > 0.05). At the V6 stage in 2021, the Pn and gsw followed the order of RP1 (RP2) > FM1 (FM2) > SM > CK (Table 1). In comparison with CK, RP, FM, and SM demonstrated a significant increase in Pn by 14.2%, 7.95%, and 4.32%, and an increase in gsw by 12.9%, 10.58%, and 8.4%, respectively. In 2022, the Pn followed the order of RP1 > RP2 > FM1 (FM2) > SM > CK. In comparison with CK, RP1, RP2, FM1, and SM exhibited a significant increase in Pn by 21.3%, 17.6%, 12.1%, and 3.9%, respectively. In contrast, the Ls displayed a reverse trend to other leaf photosynthetic parameters, following CK > SM > FM1 (FM2) > RP1 (RP2). In 2021, the order of photosynthetic rates was RP2 > RP1 > (FM1 and FM2) > SM > CK, with gsw showing similar trends, while Ls showed an entirely opposite trend at the R1 stage (Table 2). The Tr and WUEi followed the order of RP2 (RP1) > FM1 (FM2) > SM > CK. In 2022, the Pn, gsw, and Tr exhibited the same pattern as in 2021, but Ls followed the order of CK > (SM and FM2) > (FM1 and RP2) > RP1 at the R1 stage. The variation in the Pn at the R6 stage in 2021 mirrored that of R3 (Table 3), with gsw and Tr following the order of RP2 (RP1) > FM1> FM2 > SM > CK, while Ls exhibited a contrasting trend. The WUEi was ordered as RP2, RP1, FM2, and FM1 > SM > CK. During R3 in 2022, the net photosynthetic rate, gsw, and Tr followed the order of RP2 > FM2 > FM1 (RP1) > SM > CK, whereas Ls showed an opposite trend.

Table 1.

Pn, Tr, gsw, Ci, WUEi, and Ls of different treatments in the V6 stage of maize in 2021 and 2022.

Table 2.

Pn, Tr, gsw, Ci, WUEi, and Ls of different treatments in the R1 stage of maize in 2021 and 2022.

Table 3.

Pn, Tr, gsw, Ci, WUEi, and Ls of different treatments in the R3 stage of maize in 2021 and 2022.

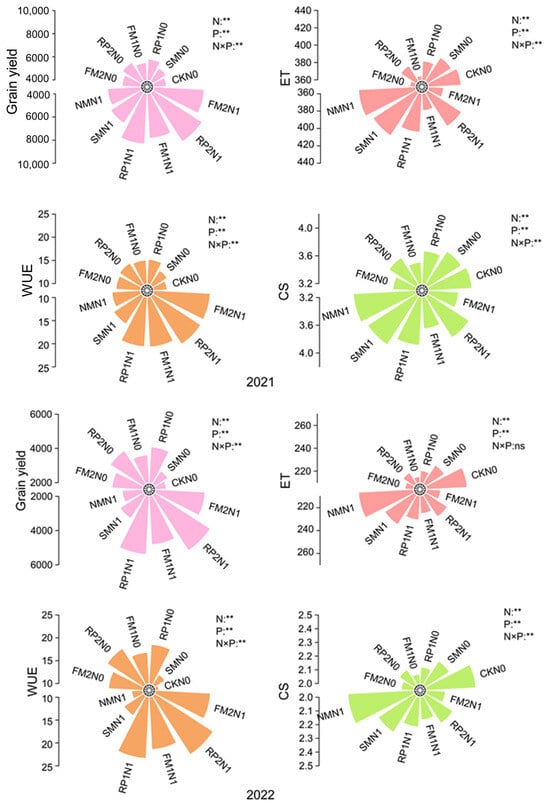

3.5. The Efffects of Different Planting Modes with Nitrogen Application on Grain Yield, ET, CS and WP

Nitrogen application and planting patterns exhibited highly significant effects on ET (p < 0.01) (Figure 7). All other planting patterns significantly reduced ET compared with CK in the same nitrogen application treatment. ET exhibited the order of CK and SM > (RP1 and RP2) > (FM1 and FM2), and there was no difference between different film colors in 2021, while in 2022, the order shifted to CK > SM > (RP1 and RP2) > (FM1 and FM2). In 2021, the ET of RP2 and FM2 decreased by 4.30% and 9.64% compared to that of CK, respectively. In 2022, the ET of SM, RP2, and FM2 decreased by 6.64%, 9.38%, and 12.73% compared to the CK, respectively. Over the two years, N1 significantly enhanced ET by 5.64% and 4.44% in 2021 and 2022 compared to N0, respectively.

Figure 7.

Influence of different treatments during the summer maize growing seasons in 2021 and 2022 on grain yield, evapotranspiration (ET), water productivity (WP), and water consumption intensity (CS). Double asterisks (**) denote significance at the 0.01 level. (ns) denotes no significant difference.

Both factors also significantly affected grain yield (p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 7. Each planting pattern resulted in a marked increase in grain yield compared to the control (CK) at the same nitrogen levels. In 2021, grain yield ranged from 5044.4 to 8996.7 kg ha−1, with no significant differences in yield among different film colors at the nitrogen rate of N0. Under N1, there were no significant differences between RP1 and FM2. The grain yield ranked as RP2 > RP1(FM2) > FM1 > SM > CK. The grain yields of SM, RP1, FM1, and RP2 increased by 4.69%, 18.88%, 12.18%, and 25.70% compared to CK, respectively. In 2022, the grain yield varied from 2577.2 and 5815.3 kg ha−1. Under N0, the ranking was RP1 (RP2) > FM1 (FM2) > SM > CK, while it was RP2 > RP1 > FM1(FM2) > SM > CK under N1. The grain yields of SM, RP1, RP2, and FM2 increased by 12.46%, 64.77%, 76.10%, and 50.01% compared to the CK, respectively. A notable distinction in grain yield was observed between N0 and N1 for the same planting mode in both years. The grain yield under N1 was enhanced by 43.46% and 30.47% compared to N0 in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Nitrogen application and planting mode had a highly significant impact on WP (p < 0.01) (Figure 7). All other planting patterns substantially enhanced WP compared to CK under the same nitrogen rate. In 2021, WP exhibited no significant difference between RP and FM. However, they were considerably higher than straw mulching. Consequently, the overall performance ranking was RP2 (followed by RP1, FM1, FM2) > SM > CK under N0. No significant variations were observed in WP among different film colors, with the overall performance of RP2 (FM2) > RP1 (FM1) > SM > CK. Compared to CK, SM, RP1, FM1, RP2, and FM2 improved WP by 6.16%, 24.27%, and 31.10% under N1, respectively. In 2022, WP in RP was substantially higher than that of FM, although the differences among the mulch colors remained insignificant. Under N1, other treatments exhibited significant variations from FM1 and FM2. The SM, RP1, FM1, RP2, and FM2 improved WP by 20.38%, 83.58%, 67.41%, 95.01%, and 72.01% compared to CK, respectively. In 2021 and 2022, WP under N1 significantly improved by 36.14% and 25.15% compared to N0, respectively. This pattern paralleled the fluctuation in CS, which consistently corresponded with WP.

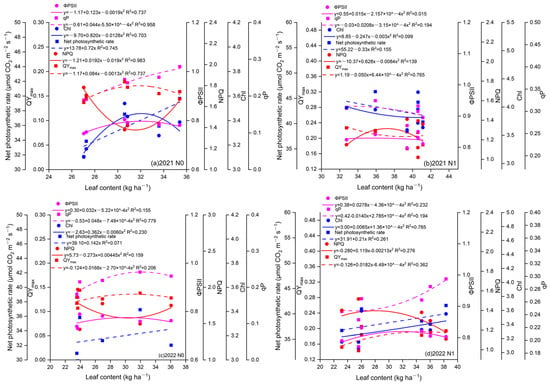

3.6. Relationships Between Leaf Nitrogen Content and Photosynthetic Performance Indicators

In 2021, the net photosynthesis rate (Pn) was positively correlated with leaf nitrogen content, showing significant correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.745 for N0 and R2 = 0.155 for N1). In 2022, however, the differences in R2 were not significant (Figure 8). In both 2021 and 2022, leaf chlorophyll content (Chl) was positively correlated with leaf nitrogen content under different nitrogen application rates, and the correlation coefficients (R2) increased with the amount of nitrogen applied (Figure 8). With increasing leaf nitrogen content, the maximum quantum yield (QYmax) initially increased and then decreased, showing a quadratic non-linear relationship in 2021 and 2022 (Figure 8). Over the two years, the R2 values for QYmax with leaf nitrogen content increased with nitrogen rate, although the difference in R2 between N0 and N1 conditions was not significant. In 2021, the R2 for QYmax with leaf nitrogen content was higher (R2 > 0.737, p < 0.05), but it was relatively lower in 2022 (R2 < 0.362, p > 0.05, Figure 8). The quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) exhibited an initial rise followed by a decline as leaf nitrogen content increased, indicating a significant quadratic non-linear relationship during both years. The coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP) increased with leaf nitrogen content, showing a significant quadratic non-linear relationship under N0 in both 2021 and 2022. As leaf nitrogen content increased, qP first increased and then decreased, showing a quadratic non-linear relationship in 2020 under W1 and W2 conditions. In 2021 and 2022 under the N1 treatment, the correlation coefficients (R2) between photochemical quenching (qP) and leaf nitrogen content were found to be insignificant. In 2021 and 2022, there was no significant correlation between non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) and leaf nitrogen content (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relationships of photosynthetic rate (Pn), chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters with leaf content under different nitrogen applications in 2021 and 2022. N0 and N1 mean nitrogen application amounts of 0 kg ha−1 N and 180 kg ha−1 N, respectively.

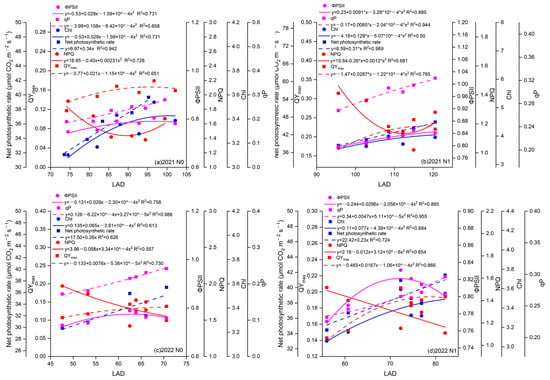

3.7. Relationships Between LAD and Photosynthetic Physiological Indicators

Over the two years, the net photosynthesis rate (Pn) under N0 and N1 showed an increasing trend with the increase of leaf area density (LAD), and there was a linear relationship between Pn and LAD. The correlation coefficient (R2) between Pn and LAD under N1 was higher than that between Pn and leaf area index (LAI) under N0. The quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) increased initially and then decreased with increasing LAD, showing a quadratic non-linear relationship in both 2021 and 2022 (Figure 9). The R2 values increased with nitrogen rate, indicating that their correlation strengthened with increased nitrogen rate, and there was a significant correlation between ΦPSII and LAD over the two years, with QYmax following the same trend as ΦPSII.

Figure 9.

Relationships of photosynthetic rate (Pn), chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters with LAD under different nitrogen applications in 2021 and 2022. N0 and N1 mean nitrogen application amounts of 0 kg ha−1 N and 180 kg ha−1 N, respectively.

The chlorophyll content (Chl) over the two years also showed a quadratic non-linear relationship with LAD, and its correlation coefficient (R2) under nitrogen application was not significantly correlated (R2 ≥ 0.613, shown in Figure 9). In 2021 and 2022, the non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) had a quadratic non-linear positive relationship with LAD (Figure 9), with the correlation coefficients between NPQ and LAI in 2021 (0.728 and 0.681) and 2022 (0.557 and 0.654) for N0 and N1 treatments being highly significant. In 2021 and 2022, the photochemical quenching (qP) showed a quadratic non-linear relationship with LAD. In 2021, the correlation coefficients (R2) between qP and LAD under N0 and N1 treatments were significant (R2 = 0.944 for N1, which was greater than R2 = 0.658 for N0); however, in 2022, there was no significant difference between the N0 and N1 treatments.

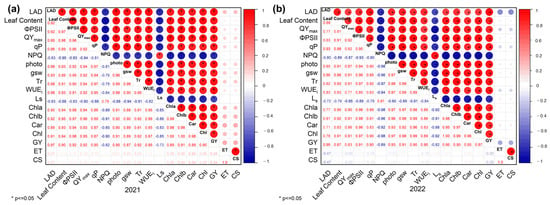

3.8. Principal Component Analysis and Correlation Matrix

Figure 10 illustrates the relationships between grain yield, ET, WP, water consumption intensity (CS), and several parameters, which include leaf nitrogen content, chlorophyll fluorescence metrics, photosynthetic traits, and pigment concentrations. Notably, leaf nitrogen content demonstrated a strong correlation with multiple indicators, including QYmax, Pn, pigment concentrations, and grain yield (GY). The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (QYmax, Pn, ΦPSII, qP) exhibited significant positive correlations with photosynthetic metrics (Pn, gsw, Tr), pigment contents (Chla, Chlb, Car, Chl), and grain yield (GY), with statistical significance at p < 0.05 and R2 values exceeding 0.82. In particular, Pn showed a highly significant positive linear relationship with QYmax, ΦPSII, and qP (p < 0.0001) and a strongly significant negative linear correlation with non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (p < 0.0001), displaying higher R2 values under the N1 treatment compared to N0 over the two years of study. Additionally, photosynthetic physiological parameters were significantly positively correlated with pigment content and grain yield (R2 > 0.90, p < 0.05). The concentration of pigments was also significantly positively linked to both grain yield and water use efficiency. Conversely, NPQ and stomatal limitation (Ls) exhibited negative correlations with other chlorophyll fluorescence metrics, photosynthetic parameters, grain yield, and pigment concentrations. It is worth noting that ET did not show any significant correlations with any of the measured parameters.

Figure 10.

Correlation coefficient matrix of physiological traits of maize leaves with yield, water productivity, evapotranspiration, and water consumption intensity (QYmax: maximum PSII quantum yield, ΦPSII: effective PSII quantum yield, qP: steady-state light-adapted photochemical quenching, NPQ: nonphotochemical quenching coefficients, Pn: photosynthetic rate, Tr: transpiration rate, Gs: stomatal conductance, WUEi: leaf WUE, Ls: stomatal limitation, Chla: chlorophyll a, Chlb: chlorophyll b, Car: carotenoids, Chl: total chlorophyll content, GY: grain yield, ET: evapotranspiration) in 2021 (a) and 2022 (b).

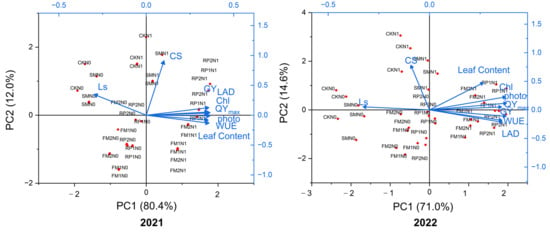

The principal component analysis method was used to comprehensively evaluate different planting modes and nitrogen application on LAD, leaf nitrogen content, grain yield, total chlorophyll content (Chl), net leaf photosynthetic rate, water use efficiency, QYmax, CS, and stomatal limitation (Figure 11). Grain yield serves as the economic foundation and is a primary concern for agricultural practitioners, while optimizing water use efficiency is a crucial objective in arid and semi-arid agricultural regions. There was a significant positive correlation between photosynthetic rate and grain yield. Following the principle of cumulative contribution exceeding 85% and eigenvalues greater than 1, two principal components were obtained by scaling down the indicators in 2021 and 2022. The variability of the eigenvalues greater than 1 for the two principal components PC1 and PC2 in 2021 and 2022 was 92.4% and 85.6%, respectively. In 2021, the photo value, Chl content, QYmax, leaf content, GY, WUE, and LAD were positively correlated with PC1, while Ls and CS were negatively correlated with PC1. In 2022, QYmax, photo value, Chl value, leaf content, CS, and Ls were positively correlated with PC1; WP, GY, and LAD were positively correlated with PC2. From the overall principal component scores, RP2N1 obtained the highest score in both years.

Figure 11.

The impacts of planting mode and nitrogen application on photosynthetic activity, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, chlorophyll content, leaf nitrogen content, leaf area duration (LAD), yield, and water productivity of summer maize in the years 2021 and 2022 were investigated using principal component analysis (PCA). The lines emanating from the center point of the biplot demonstrate the positive or negative associations between various variables. The proximity of the lines indicates the strength of the correlation with a particular treatment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Nitrogen Application and Planting Mode on Photosynthetic Pigments and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

The leaf nitrogen content is a critical parameter that reflects the nutritional status of crops and provides essential reference points for evaluating crop growth performance and estimating yield [10]. In this study, nitrogen application significantly enhanced the leaf photosynthetic rate; furthermore, the trends in transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic rate were similar, illustrating a strong causal relationship between leaf photosynthetic capacity and nitrogen content, with a correlation coefficient exceeding 0.90 (Figure 10). This enhancement is attributed to nitrogen application stimulating early leaf growth in maize, thereby improving its photosynthetic rate [23]. The photosynthetic rates (Pn) under different planting patterns were ranked as RP > FM > SM > CK. This ranking arises from changes in soil moisture conditions induced by different planting patterns, leading to varying adaptive responses in crops; the reduction of stomatal conductance acts as the primary mechanism for minimizing water loss [24].

Given that stomatal conductance affects the exchange of CO2 and H2O between leaves and the environment, the strong relationship between stomatal conductance and Pn (R2 = 0.96 in 2021 and R2 = 0.97 in 2022, Figure 10) effectively explained the variations in Pn across different treatments. During the early growth stage of maize (Table 1), ridge-furrow planting mulched with plastic film significantly increased Pn compared to flat planting. This result can be attributed to the ridge-furrow planting pattern, which inhibited soil evaporation, reduced surface wind speed, significantly decreased surface long-wave radiation, and increased rainwater collection. These factors effectively improved soil thermal conditions, significantly promoting the opening of leaf stomata (thereby increasing gsw and reducing Ls) and enhancing Tr and Pn. From a physiological perspective, the soil moisture conditions under the CK treatment were relatively dry; when crop roots sense drought stress, they induce non-hydraulic drought stress signals, such as ABA, which increase and are transmitted to the leaves, leading to a decrease in stomatal conductance [25,26].

Compared to ridge-furrow flat planting (RF), leaf nitrogen content under the CK treatment was lower, making it easier to reduce gsw and consequently inhibiting carbon assimilation, as the photosynthetic rate largely depends on the levels of the Rubisco enzyme and chlorophyll. In this study, Pn under the covered conditions increased significantly by 20.5% compared to CK and by 6.9% compared to SM, primarily due to improvements in soil water and thermal conditions from film mulching, which stimulated biochemical processes related to soil nitrogen cycling [7,8]. We observed a strong correlation between leaf nitrogen content, chlorophyll content, and leaf photosynthesis. Our study indicated that, compared to no mulching, soil mulching significantly increased WUEi, mainly because WUEi was closely related to the plant’s maximum carbon absorption concentration (i.e., high Pn) and its ability to limit water loss by regulating stomatal opening (i.e., transpiration rate, Tr) as part of drought avoidance strategies [27]. WUEi was significantly higher under black film mulching than under white film mulching, possibly due to differences in soil water retention capacity resulting from the mulching strategies employed. Compared to straw mulching and CK, film mulching significantly increased Pn, Tr, Gs, and Ci, consistent with previous studies [28].

4.2. Effect of Nitrogen Application and Planting Mode on Leaf Gas Exchange Parameters

Chlorophyll is essential for the primary processes of photosynthesis [27]. The application of nitrogen primarily delays leaf senescence, which affects the levels of photosynthetic pigments in leaves and, consequently, the photosynthetic rate [28]. In this study, ridge-furrow planting significantly boosted chlorophyll content in maize leaves compared to flat planting. This increase is linked to the strong association between chlorophyll production and water availability. Water deficiency in leaves hinders chlorophyll synthesis, promotes chlorophyll decomposition, and accelerates leaf yellowing. Ridge-furrow planting provides better soil moisture conditions than flat planting, thereby mitigating the decline in chlorophyll content caused by excessive soil moisture evaporation and drought stress [29]. The total chlorophyll content directly affects the photosynthetic capacity of plants. The results indicate that nitrogen application reduces the chlorophyll a/b ratio, increases the absorption of short-wavelength light during the summer, and induces changes in the tissue components involved in electron transfer, thereby improving assimilate synthesis during the reproductive growth stage [30,31].

This study also demonstrated a significant increase in chlorophyll content associated with mulching, possibly due to enhanced nitrogen absorption and increased leaf nitrogen content, suggesting the potential for augmented productivity in the treated plants. Nitrogen is a critical component of plant chlorophyll and proteins [11]. When nitrogen is deficient, crops struggle to absorb light energy, leading to diminished activity in the PSII reaction center. This impairment hampers the initial phases of photosynthesis and restricts the transfer of electrons from the PSII reaction center to electron acceptors, resulting in decreased Fv/Fm and ΦPSII [32], aligning with our findings. However, our study showed that nitrogen application significantly improved PSII activity, photochemical efficiency, and the ratio of open PSII reaction centers in maize leaves. These improvements enhance the effective utilization of captured light energy, thereby boosting both the quantum and photosynthetic efficiency of PSII. Our research indicates that chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were markedly higher under black plastic mulch compared to transparent mulch and no mulch.

This occurs because mulch cover reduces daytime soil temperatures, though each type exhibits distinct cooling effects—beneficial during hot summers when excessive heat harms corn (Zea mays L.). Transparent films risk overheating soils (>35 °C), inhibiting optimal root activity even suppressing yields where temperatures exceed tolerance thresholds [33,34,35]. In our study, the average values followed the trend of ridge-furrow planting (RP) > flat mulching (FM) > soil mulching (SM) > non-mulching (NM), highlighting a significant difference between film mulching and both SM and NM. This difference is attributed to the enhanced water retention capacity of mulching treatments, which mitigates crop drought stress, increases nitrogen absorption in leaves, and consequently elevates leaf photosynthetic pigment content, Pn, and transpiration rate (Tr). These enhancements result in improved effective PSII quantum yield (ΦPSII) and increased photochemical quenching coefficient (qP) associated with drought damage in maize. Moreover, a systematic rise in harmless dissipation of excess energy corresponds with a greater elevation in non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), reflecting reduced water stress under mulching conditions [10]. A strong correlation exists between photosynthetic parameters and chlorophyll fluorescence (Figure 10), indicating that high photosynthesis rates significantly depend on the number of electrons flowing through PSII. Thus, the increase in chlorophyll content notably enhances both chlorophyll fluorescence metrics and the photosynthetic capacity of the leaves, consistent with prior research [9].

4.3. Effects of Mulching Mode and Nitrogen Application on Water Utilization and Grain Yield

Dry matter accumulation and grain yield formation are determined by leaf area, photosynthetic duration, and photosynthetic rate [36]. The jointing and grain-filling stages are critical for maize growth, with a high photosynthetic rate being essential for achieving stable and high yields [37]. The photosynthetic rate was closely linked to variations in water and nitrogen due to different planting modes and nitrogen rates. Furthermore, changes in chlorophyll content significantly affect maize leaf photosynthesis. Yield increases are associated with improved growth, enhanced nutrient absorption, and increased photosynthesis resulting from specific planting patterns and nitrogen application. This research indicated that these planting patterns and nitrogen application notably improved maize yield by significantly increasing leaf area index and light energy interception. In this study, grain yield under different mulching patterns ranked as follows: FM > SM > NM. The possible reasons for this ranking included: (1) plastic mulching significantly increased soil moisture and temperature, optimizing crop phenology, ensuring water supply, and enhancing light reflection toward the canopy, thereby improving photosynthetic capacity and crop primary productivity [38,39]; (2) compared to straw mulching and non-mulching, plastic mulching markedly reduced soil evaporation, improved soil thermal and moisture conditions, promoted nitrogen absorption, and enhanced photosynthesis and energy transfer, resulting in increased yield; and (3) mulching enhanced photosynthetic rate and grain yield, correlating positively with chlorophyll content, leaf nitrogen levels, and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters [40].

This study showed that nitrogen application and planting practices act synergistically in the following ways: (1) improving soil moisture and nutrient conditions, thereby enabling the root system to absorb nitrogen more efficiently [34,40]; (2) reducing soil water limitation through mulching, which allows leaves to maintain higher stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rates, while appropriate nitrogen application further enhances the effectiveness of photosynthesis in carbon fixation [41]; and (3) reducing evapotranspiration (ET) [42,43], which in turn has positive effects on maize photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, thereby increasing water productivity (WP) and grain yield. This study revealed that nitrogen application boosts water productivity (WP) by enhancing grain yield and positively influencing maize photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Both ridge-furrow mulching and nitrogen application reduced evapotranspiration (ET) while increasing WUE and grain yield. Overall, these practices improved rainwater capture and utilization efficiency, minimized soil water loss, and created optimal soil temperature and moisture conditions during maize’s critical growth phase, fostering crop growth and grain yield. This system has significant potential to enhance grain yield and ensure food security globally, especially in rainfed regions [5]. Under the same cultivation mode (ridge-furrow or flat planting), grain yield with black film mulching was higher than that with transparent film mulching. However, Mbah reported the opposite result, where black film mulching produced lower grain yield [44], primarily because the lower soil temperature limited maize growth in their study area (southeastern Nigeria). From an environmental and sustainability perspective, film mulching, while effective in conserving soil moisture and improving yield, can lead to residual plastic accumulation in soils, posing risks to soil health and microbial diversity [45]. To enhance sustainability, the adoption of biodegradable films or organic mulching materials such as straw can help reduce plastic pollution while maintaining many of the agronomic benefits. Additionally, optimized nitrogen management paired with mulching can minimize nutrient leaching and greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to more climate-resilient and eco-friendly agricultural practices [46]. Integrating these approaches supports both high productivity and the protection of environmental resources essential for long-term food security.

5. Conclusions

Various planting patterns and nitrogen rates significantly enhanced maize yield and water use efficiency by influencing leaf nitrogen content and LAD, which in turn affected leaf photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigment content, and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Additionally, there was a strong positive correlation between LAD, leaf nitrogen content, photosynthetic parameters (Pn, gsw, Ci, Tr), chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (QYmax, ΦPSII, qP), photosynthetic pigment content (Chl a, Chl b, Chl a/b), and crop yield. Both RP and N application increased Pn, Tr, Gs, WUEi (during grain filling period), QYmax, ΦPSII, qP, Chl b, Chl a, Chl, WP, and yield, except for Chl a/b, NPQ, and ET. Therefore, the results of the overall principal component scores showed that RP2N1 obtained the highest score in both years, which was thus recommended as the optimal maize planting pattern in the study area. These findings indicate that adopting the RP2 planting pattern in combination with a moderate nitrogen rate (N1) can provide farmers in the study region with a high-yield and water-efficient option, without relying on excessive nitrogen inputs. This management strategy can help improve resource-use efficiency and economic returns, while potentially reducing the environmental risks associated with over-fertilization. Future research should further evaluate the sustainability of this pattern in terms of soil fertility, root–soil interactions, and environmental impacts (e.g., nitrogen losses and greenhouse gas emissions). Such studies would help refine region-specific recommendations and support the broader adoption of maize planting and fertilization strategies that simultaneously enhance productivity, water use efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai) and J.F.; Data curation, Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai), S.P. and H.W.; Formal analysis, H.K., Z.L. (Zhenqi Liao), Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai) and H.W.; Funding acquisition, J.F.; Investigation, H.K., M.H., Z.L. (Zhenqi Liao), H.W. and S.P.; Methodology, Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai), H.K. and Z.L. (Zhenqi Liao); Project administration, Z.L. (Zhijun Li); Resources, Z.L. (Zhijun Li) and J.F.; Supervision, J.F.; Validation, S.P.; Visualization, Z.L. (Zhenqi Liao), H.W., S.P. and J.F.; Writing—original draft, Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai); Writing—review & editing, Z.L. (Zhenlin Lai), M.H. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFC0403303) and the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (No. 2452020018).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Begizew, G. Agricultural Production System in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. J. Agric. Sci. Food Technol. 2021, 7, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.P.; Cook, E.R.; Smerdon, J.E.; Cook, B.I.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Bolles, K.; Baek, S.H.; Badger, A.M.; Livneh, B. Large Contribution from Anthropogenic Warming to an Emerging North American Megadrought. Science 2020, 368, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, H.; Lu, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Changes in Dryland Areas and Net Primary Productivity in China from 1980 to 2020. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 132, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Gao, Q.; Xie, R.; Li, S.; Meng, Q.; Kirkby, E.A.; Römheld, V.; Müller, T.; Zhang, F.; Cui, Z.; et al. Grain Yields in Relation to N Requirement: Optimizing Nitrogen Management for Spring Maize Grown in China. Field Crops Res. 2012, 129, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Turner, N.C.; Li, X.-G.; Niu, J.-Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Chai, Q. Chapter Seven—Ridge-Furrow Mulching Systems—An Innovative Technique for Boosting Crop Productivity in Semiarid Rain-Fed Environments. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 118, pp. 429–476. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J.-Y.; Zhou, H.; Luo, C.-L.; Zhang, X.-F.; Li, X.-Y.; Li, F.-M.; Xiong, L.-B.; Kavagi, L.; Nguluu, S.N.; et al. Ridge-Furrow Plastic-Mulching with Balanced Fertilization in Rainfed Maize (Zea mays L.): An Adaptive Management in East African Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 236, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, F. Mulching Affects Photosynthetic and Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Characteristics during Stage III of Peach Fruit Growth on the Rain-Fed Semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 194, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Zhang, L.; Xie, B.; Dong, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, A.; Wang, Q. Effect of Plastic Mulching on the Photosynthetic Capacity, Endogenous Hormones and Root Yield of Summer-Sown Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L). Lam.) in Northern China. Acta Physiol. Plant 2015, 37, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, N.K.; Lenka, S.; Thakur, J.K.; Yashona, D.S.; Shukla, A.K.; Elanchezhian, R.; Singh, K.K.; Biswas, A.K.; Patra, A.K. Carbon Dioxide and Temperature Elevation Effects on Crop Evapotranspiration and Water Use Efficiency in Soybean as Affected by Different Nitrogen Levels. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 230, 105936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, X.; Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Dong, Z.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, P.; Han, Q. Plastic Film Mulching Stimulates Soil Wet-Dry Alternation and Stomatal Behavior to Improve Maize Yield and Resource Use Efficiency in a Semi-Arid Region. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIN, Y.; HU, Y.; REN, C.; GUO, L.; WANG, C.; Jiang, Y.; WANG, X.; Phendukani, H.; Zeng, Z. Effects of Nitrogen Application on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters and Leaf Gas Exchange in Naked Oat. J. Integr. Agric. 2013, 12, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, O.; Hlaváčová, M.; Klem, K.; Novotná, K.; Rapantová, B.; Smutná, P.; Horáková, V.; Hlavinka, P.; Škarpa, P.; Trnka, M. Combined Effects of Drought and High Temperature on Photosynthetic Characteristics in Four Winter Wheat Genotypes. Field Crops Res. 2018, 223, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramova, V.; AbdElgawad, H.; Zhang, Z.; Fotschki, B.; Casadevall, R.; Vergauwen, L.; Knapen, D.; Taleisnik, E.; Guisez, Y.; Asard, H.; et al. Drought Induces Distinct Growth Response, Protection, and Recovery Mechanisms in the Maize Leaf Growth Zone. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambussi, E.A.; Nogués, S.; Araus, J.L. Ear of Durum Wheat under Water Stress: Water Relations and Photosynthetic Metabolism. Planta 2005, 221, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Xu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Ahmad, I.; Wei, T.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P.; Din, R.; Cai, T.; Jia, Z. Cultivation Techniques Combined with Deficit Irrigation Improves Winter Wheat Photosynthetic Characteristics, Dry Matter Translocation and Water Use Efficiency under Simulated Rainfall Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; He, L.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Guo, B.-B.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Guo, T.-C. Assessment of Plant Nitrogen Status Using Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters of the Upper Leaves in Winter Wheat. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 64, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadražnik, T.; Hollung, K.; Egge-Jacobsen, W.; Meglič, V.; Šuštar-Vozlič, J. Differential Proteomic Analysis of Drought Stress Response in Leaves of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Proteom. 2013, 78, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilundo, M.; Joel, A.; Wesström, I.; Brito, R.; Messing, I. Effects of Reduced Irrigation Dose and Slow Release Fertiliser on Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Crop Yield in a Semi-Arid Loamy Sand. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 168, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis: A Guide to Good Practice and Understanding Some New Applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhang, L.; Duan, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhao, P.; van der Werf, W.; Evers, J.B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Sun, Z. Ridge and Furrow Systems with Film Cover Increase Maize Yields and Mitigate Climate Risks of Cold and Drought Stress in Continental Climates. Field Crops Res. 2017, 207, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Cai, H.; Liu, Z. Nitrogen Reduction with Supplemental Irrigation Enhances Yield by Delaying Leaf Senescence and Optimizing Grain-Filling Process for Ridge-Furrow Film Mulching Winter Wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Li, Y.; Fang, H.; Chen, P. Ridge-Furrow Mulching Combined with Appropriate Nitrogen Rate for Enhancing Photosynthetic Efficiency, Yield and Water Use Efficiency of Summer Maize in a Semi-Arid Region of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Reddy, K.R.; Kakani, V.G.; Reddy, V.R. Nitrogen Deficiency Effects on Plant Growth, Leaf Photosynthesis, and Hyperspectral Reflectance Properties of Sorghum. Eur. J. Agron. 2005, 22, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Yadollahi, A.; Arzani, K.; Imani, A.; Aghaalikhani, M. Gas-Exchange Response of Almond Genotypes to Water Stress. Photosynthetica 2015, 53, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jensen, C.R.; Shahanzari, A.; Andersen, M.N.; Jacobsen, S.-E. ABA Regulated Stomatal Control and Photosynthetic Water Use Efficiency of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during Progressive Soil Drying. Plant Sci. 2005, 168, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J. Moderate Wetting and Drying Increases Rice Yield and Reduces Water Use, Grain Arsenic Level, and Methane Emission. Crop J. 2017, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, N.; Hou, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Factors Influencing Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Natural Forests at the Biome Scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ruiz, J.; Sanz, M.; Curt, M.D.; Plaza, A.; Lobo, M.C.; Mauri, P.V. Fertigation of Arundo Donax L. with Different Nitrogen Rates for Biomass Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 133, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Ding, R.; Han, Q.; Cai, T.; Jia, Z. Ridge and Furrow Planting Pattern Optimizes Canopy Structure of Summer Maize and Obtains Higher Grain Yield. Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, O.; Linker, R.; Gitelson, A. Non-Destructive Estimation of Foliar Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents: Focus on Informative Spectral Bands. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 38, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, C.; St. Martin, S.K.; Xie, F. Effect of Shade on Leaf Photosynthetic Capacity, Light-Intercepting, Electron Transfer and Energy Distribution of Soybeans. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 83, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Xu, G.; Phonenasay, S.; Luo, Q.; Han, Z.; Lu, W. Effects of Nitrogen Application Rate on the Photosynthetic Pigment, Leaf Fluorescence Characteristics, and Yield of Indica Hybrid Rice and Their Interrelations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.G.; Guan, Z.-H.; Jia, B.; Turner, N.C.; Li, F.-M. The Effects of Plastic-Film Mulch on the Grain Yield and Root Biomass of Maize Vary with Cultivar in a Cold Semiarid Environment. Field Crops Res. 2018, 216, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M. Ridge-Furrow Mulching with Black Plastic Film Improves Maize Yield More than White Plastic Film in Dry Areas with Adequate Accumulated Temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 262, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, P.; Duan, C.; Wu, S.; Feng, H.; Zou, Y. Black Plastic Film Combined with Straw Mulching Delays Senescence and Increases Summer Maize Yield in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, A.J.; Faralli, M.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Lawson, T. Photosynthesis in Non-Foliar Tissues: Implications for Yield. Plant J. 2020, 101, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, W.; Li, K.; Qi, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, C. Understanding Physiological Mechanisms of Variation in Grain Filling of Maize under High Planting Density and Varying Nitrogen Applicate Rate. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 998946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, F.; Li, X.; Niu, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, Y. Alternating Small and Large Ridges with Full Film Mulching Increase Linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) Productivity and Economic Benefit in a Rainfed Semiarid Environment. Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Duan, A.; Qiu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Distribution of Roots and Root Length Density in a Maize/Soybean Strip Intercropping System. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Feng, H.; Dong, Q. Effects of Different Plastic Film Mulching on Soil Hydrothermal Conditions and Grain-Filling Process in an Arid Irrigation District. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yan, C.; Liu, Q.; Ding, W.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. Effects of Plastic Mulching and Plastic Residue on Agricultural Production: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheysari, M.; Loescher, H.W.; Sadeghi, S.H.; Mirlatifi, S.M.; Zareian, M.J.; Hoogenboom, G. Water-Yield Relations and Water Use Efficiency of Maize Under Nitrogen Fertigation for Semiarid Environments: Experiment and Synthesis. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 130, pp. 175–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Sainju, U.M.; Ghimire, R. Soil Water Storage, Winter Wheat Yield, and Water-Use Efficiency with Cover Crops and Nitrogen Fertilization. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, C.N.; Nwite, J.N.; Njoku, C.; Ibeh, L.M.; Igwe, T.S. Physical Properties of an Ultisol under Plastic Film and No-Mulches and Their Effect on the Yield of Maize. World J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 6, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Gao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Song, X.; Cai, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Zhao, X.; Li, C. 1The Harm of Residual Plastic Film and Its Accumulation Driving Factors in Northwest China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Sui, Q.; Dong, B.; Liao, Z.; Yang, C.; Deng, X.; Li, Z.; Fan, J. Effects of Mulching Cultivation Patterns on Grain Yield, Resources Use Efficiency and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Rainfed Summer Maize on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 315, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).