Lightweight Structure and Attention Fusion for In-Field Crop Pest and Disease Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

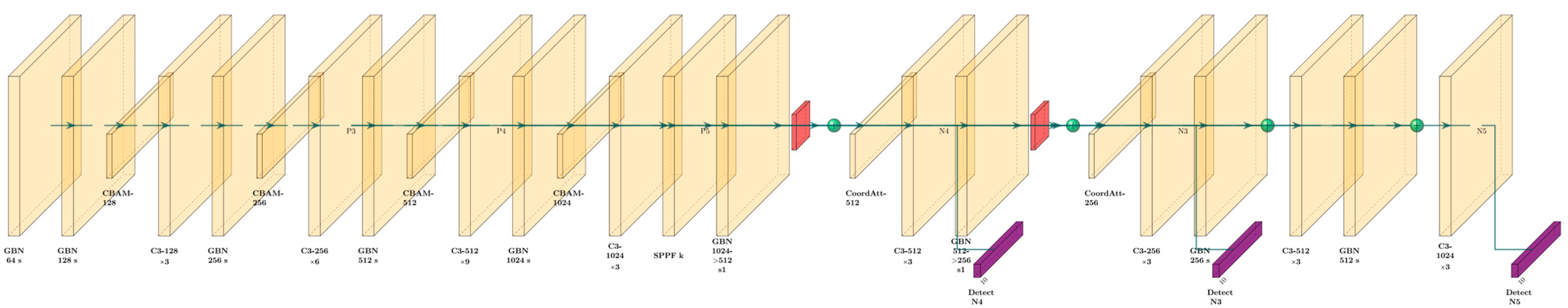

2.1. Overview of the Model Improvements

2.2. GhostConv

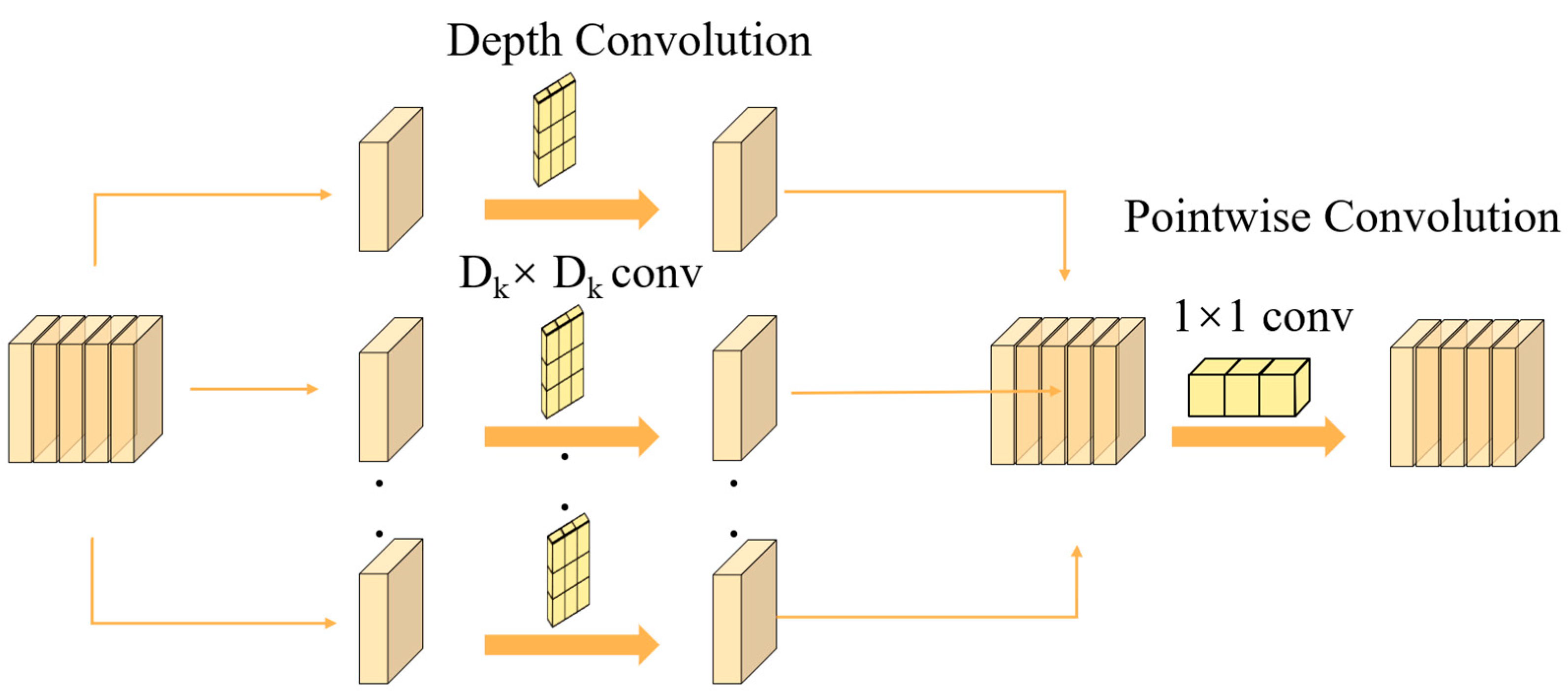

2.3. Depthwise Convolution

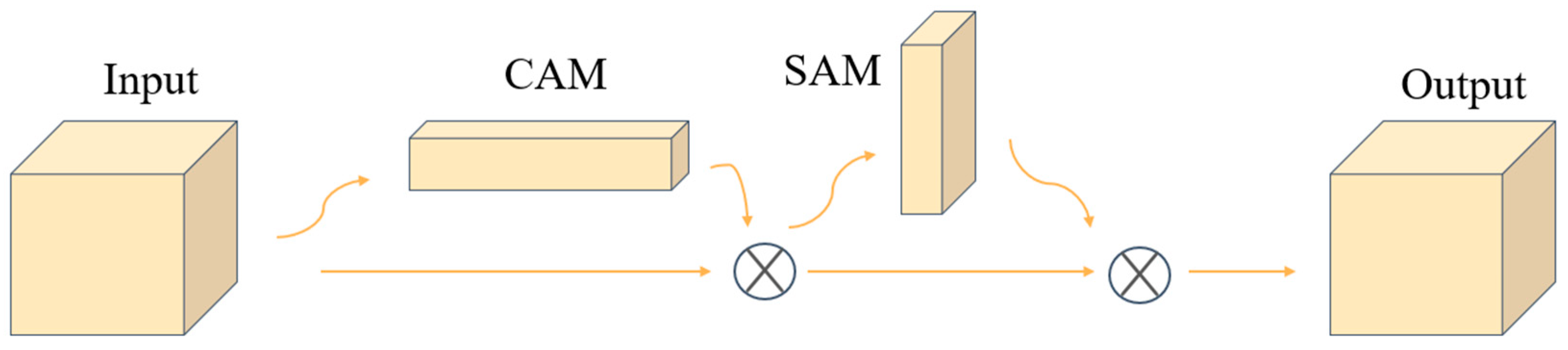

2.4. CBAM

2.5. Coordinate Attention

2.6. Dataset

2.7. Implementation Details

2.8. Evaluation Metrics

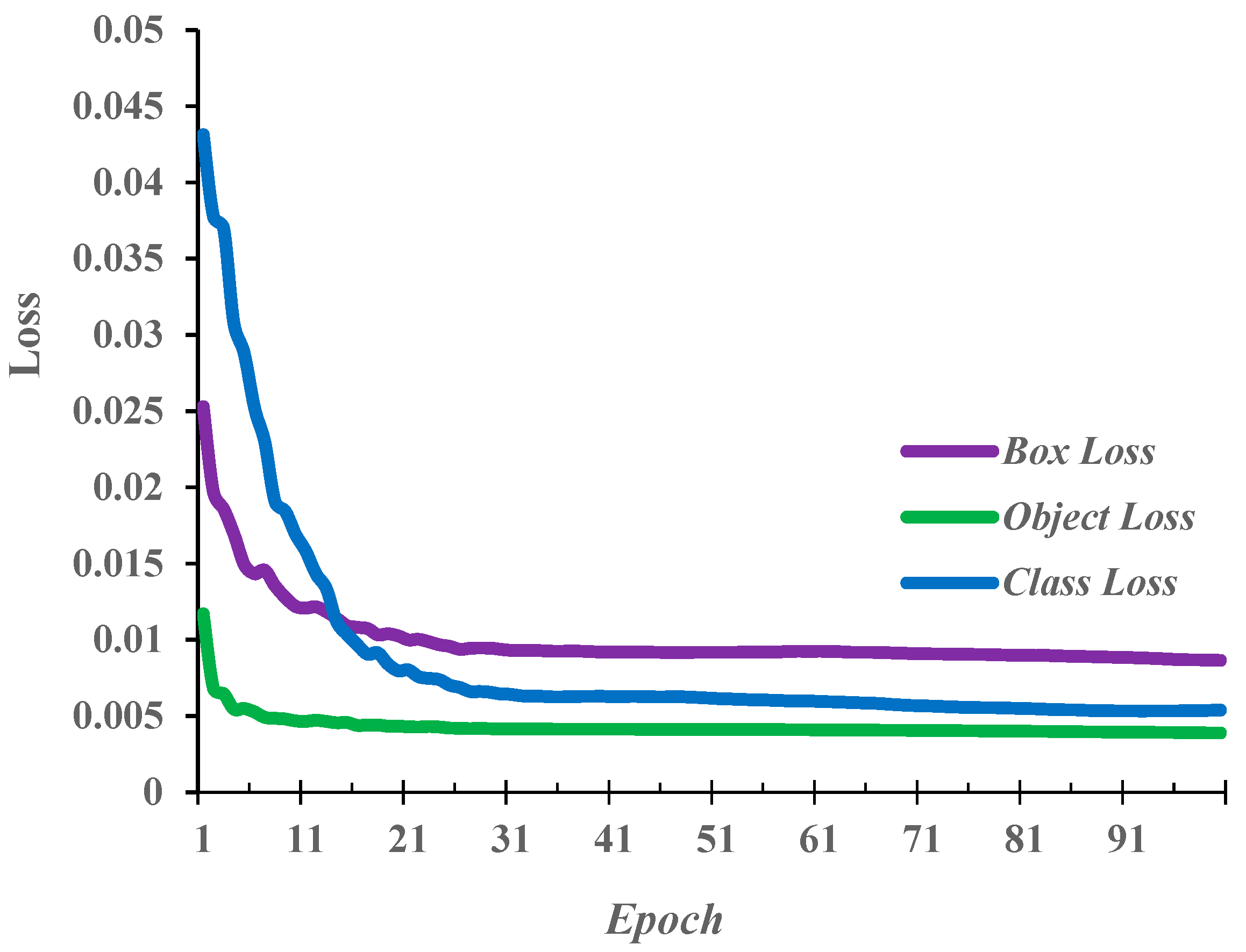

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ablation Study

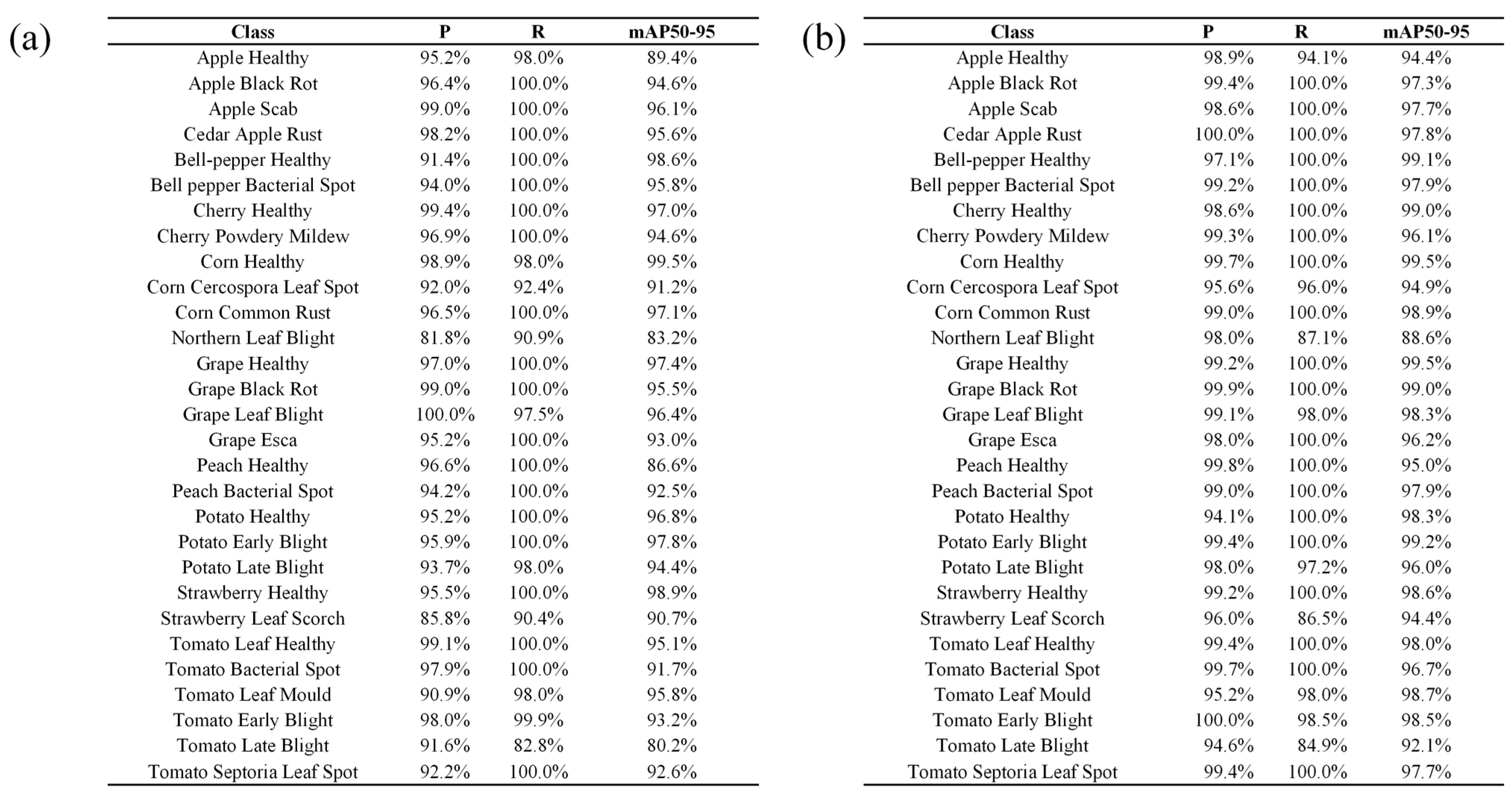

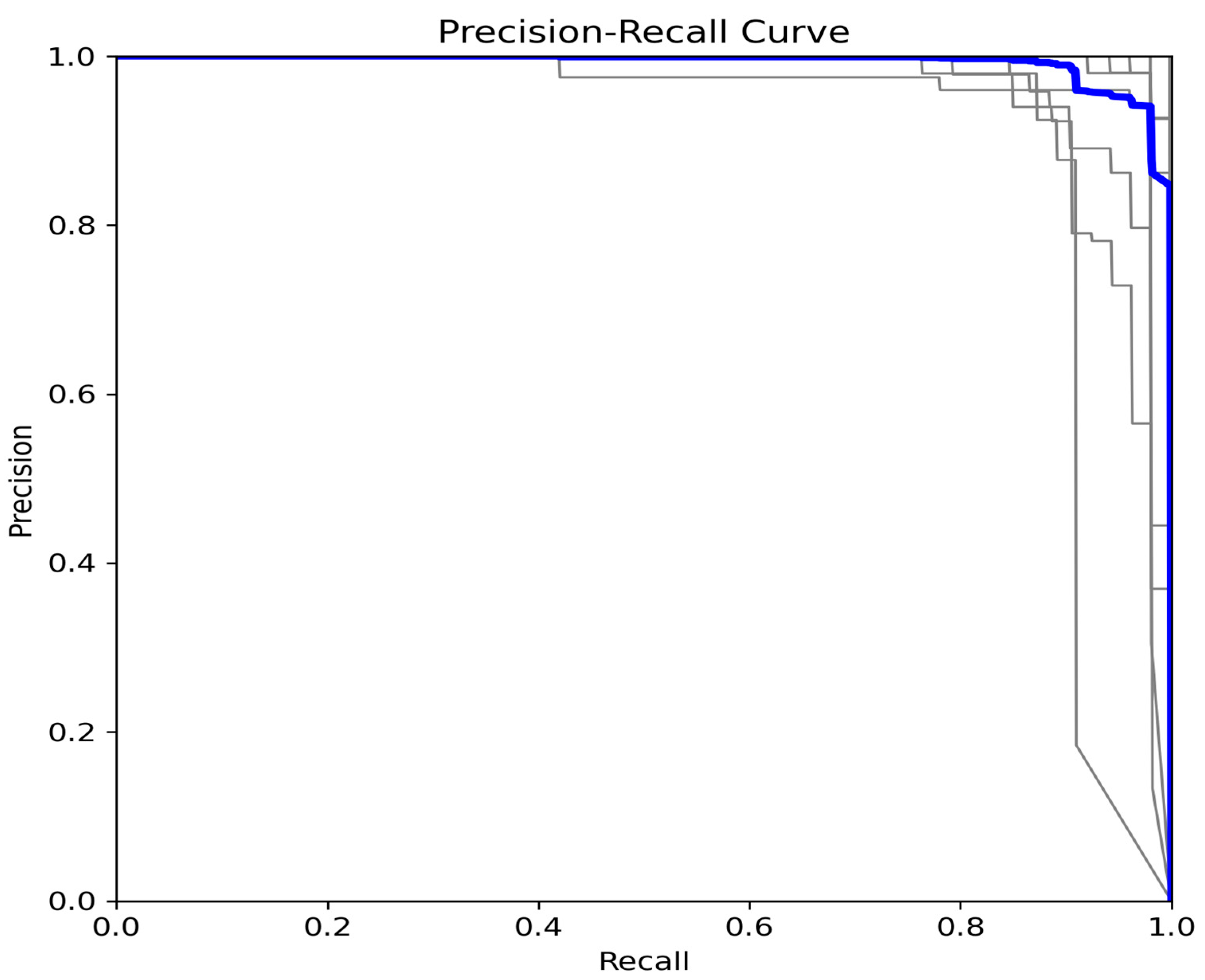

3.2. Comparison Between Baseline YOLOv5s and YOLOv5s-LiteAttn

3.3. Comparative Experiment

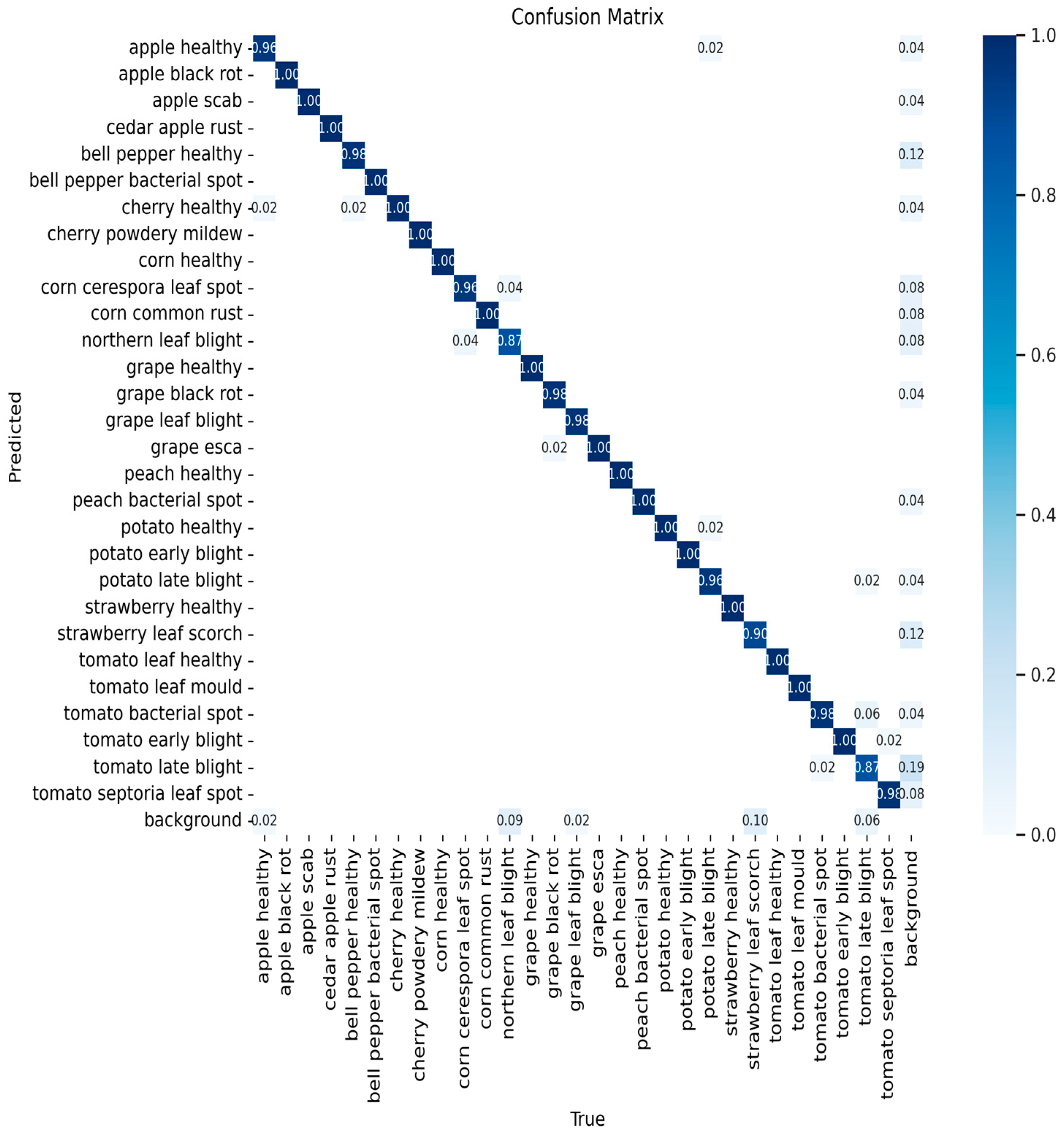

3.4. Per-Class Performance Analysis

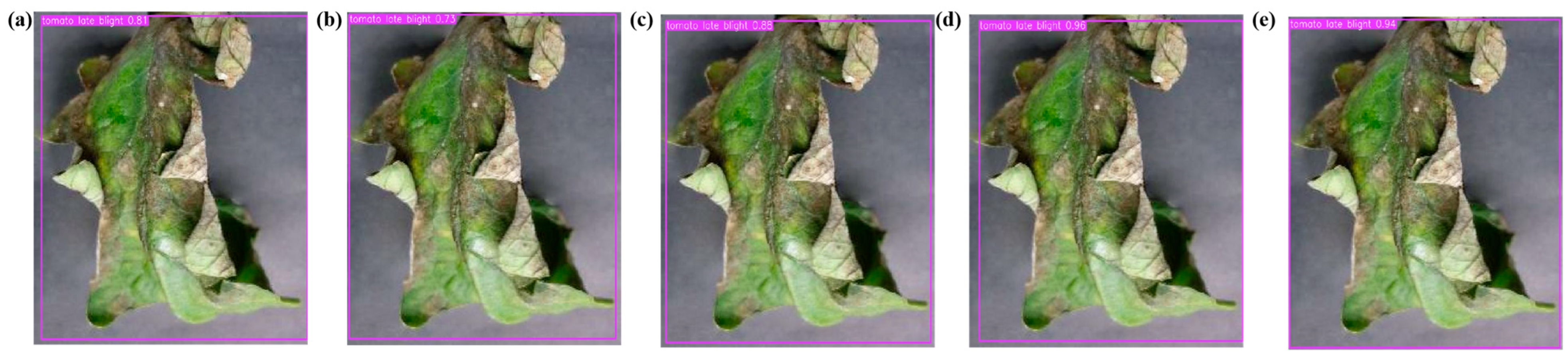

3.5. Application Evaluation Based on an Independent Test Set

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.-S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.-Y. Impact of climatic change on agricultural production and response strategies in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2010, 18, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, H.; Liao, F.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Tang, J.; Yao, Q. An intelligent monitoring system of diseases and pests on rice canopy. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 972286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerke, E.-C. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Qin, W.; Abbas, A.; Ji, R.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Yang, J. Identification of cotton pest and disease based on CFNet-VoV-GCSP-LSKNet-YOLOv8s: A new era of precision agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1348402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T. Crop insect pest detection based on dilated multi-scale attention U-Net. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S.; Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 1943, 5, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems. Univ. Mich. Press Google Sch. 1975, 2, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Zheng, N. Weight-based ensemble method for crop pest identification. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Z. A lightweight model for efficient identification of plant diseases and pests based on deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, A.; Diepeveen, D.; Murray, D.; Jones, M.G.; Sohel, F. Multi-task learning model for agricultural pest detection from crop-plant imagery: A Bayesian approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, S. Field detection of pests based on adaptive feature fusion and evolutionary neural architecture search. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Li, H. Fruit Tree Pest Identification Method Based on MobileViT-PC-ASPP and Transfer Learning. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Mao, T.; Shi, Y.; Ren, Y. Overview of knowledge reasoning for knowledge graph. Neurocomputing 2024, 585, 127571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.G. A review of intelligent question answering research based on knowledge graphs. J. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2020, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Gamba, P.; Feng, L. GMSR: Gradient-Integrated Mamba for Spectral Reconstruction from RGB Images. Neural Netw. 2025, 193, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S. Transformer help CNN see better: A lightweight hybrid apple disease identification model based on transformers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, G. Multi-plant disease identification based on lightweight ResNet18 model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics/Yolov5: V3.1—Bug Fixes and Performance Improvements, v3.1; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Yeh, I.-H. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 390–391. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Jain, N.; Jain, P.; Kayal, P.; Kumawat, S.; Batra, N. PlantDoc: A dataset for visual plant disease detection. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM IKDD CoDS and 25th COMAD, Hyderabad, India, 5–7 January 2020; pp. 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.; Su, W.-H. YOLOV5-CBAM-C3TR: An optimized model based on transformer module and attention mechanism for apple leaf disease detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1323301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J. Vegetable disease detection using an improved YOLOv8 algorithm in the greenhouse plant environment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ruan, M.; Ke, T.; Wang, H.; Lv, C. Grape Disease Detection Using Transformer-Based Integration of Vision and Environmental Sensing. Agronomy 2025, 15, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Sun, S.; Bao, X. A Review of Computer Vision and Deep Learning Applications in Crop Growth Management. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.F.; Mao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Elmasry, G.; Awad, M.A.; Abdalla, A.; Mousa, S.; Elwakeel, A.E.; Elsherbiny, O. Emerging technologies for precision crop management towards agriculture 5.0: A comprehensive overview. Agriculture 2025, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Class | Num | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Apple Healthy | 949 | Healthy Plant |

| Apple Black Rot | 943 | Fungal Disease | |

| Apple Scab | 945 | ||

| Cedar Apple Rust | 948 | ||

| Bell-pepper | Bell-pepper Healthy | 945 | Healthy Plant |

| Bell pepper Bacterial Spot | 944 | Bacterial Disease | |

| Cherry | Cherry Healthy | 940 | Healthy Plant |

| Cherry Powdery Mildew | 941 | Fungal Disease | |

| Corn | Corn Healthy | 940 | Healthy Plant |

| Corn Cercospora Leaf Spot | 953 | Fungal Disease | |

| Corn Common Rust | 964 | ||

| Northern Leaf Blight | 1003 | ||

| Grape | Grape Healthy | 946 | Healthy Plant |

| Grape Black Rot | 945 | Fungal Disease | |

| Grape Leaf Blight | 966 | ||

| Grape Esca | 942 | Other Diseases/Conditions | |

| Peach | Peach Healthy | 941 | Healthy Plant |

| Peach Bacterial Spot | 946 | Bacterial Disease | |

| Potato | Potato Healthy | 934 | Healthy Plant |

| Potato Early Blight | 947 | Fungal Disease | |

| Potato Late Blight | 947 | ||

| Strawberry | Strawberry Healthy | 946 | Healthy Plant |

| Strawberry Leaf Scorch | 1048 | Other Diseases/Conditions | |

| Tomato | Tomato Leaf Healthy | 946 | Healthy Plant |

| Tomato Bacterial Spot | 956 | Bacterial Disease | |

| Tomato Leaf Mould | 944 | Fungal Disease | |

| Tomato Early Blight | 967 | ||

| Tomato Late Blight | 1067 | ||

| Tomato Septoria Leaf Spot | 952 |

| Model | Layers | Params (M) | FLOPs (GF) | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5–0.95 (%) | FPS | Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s Baseline | 157 | 7.12 | 16.10 | 95.1 | 96.8 | 93.8 | 121.00 | 13.90 |

| YOLOv5s-Ghost | 184 | 5.89 | 13.30 | 96.1 | 96.2 | 96.1 | 147.00 | 11.58 |

| YOLOv5s-CBAM | 185 | 6.15 | 14.10 | 94.1 | 97.2 | 91.3 | 133.00 | 12.13 |

| YOLOv5s-CoordAtt | 245 | 7.15 | 16.20 | 95.0 | 94.0 | 95.7 | 112.00 | 14.02 |

| YOLOv5s-DW | 223 | 5.09 | 11.46 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 92.6 | 167.00 | 10.00 |

| YOLOv5s-LiteAtten | 394 | 5.50 | 13.40 | 98.4 | 97.9 | 97.1 | 142.00 | 11.00 |

| Model | Params/M | FLOPs/G | mAP@0.5–0.95/% | R/% | Size/MB | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 7.12 | 16.10 | 93.8 | 96.8 | 13.9 | 121.0 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 6.12 | 13.40 | 89.2 | 91.2 | 47.1 | 105.0 |

| YOLOX-s | 8.95 | 26.84 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 68.6 | 70.0 |

| YOLOv11-s | 9.42 | 21.40 | 98.3 | 98.4 | 18.8 | 88.0 |

| SSD-MobileNetV3 large | 2.76 | 2.09 | 82.1 | 92.5 | 10.8 | 235.0 |

| Faster R-CNN(R50-FPN) | 41.55 | 182.54 | 73.8 | 85.3 | 158.0 | 12.0 |

| EfficientDet-D0 | 3.85 | 7.79 | 70.4 | 86.2 | 15.1 | 195.0 |

| YOLOv5s-LiteAttn | 5.50 | 13.40 | 97.1 | 97.9 | 11.0 | 142.0 |

| Model | Params/M | FLOPs/G | mAP@0.5–0.95/% | R/% | FPS | Size/MB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 7.12 | 16.10 | 91.2 | 95.9 | 118.0 | 13.9 |

| YOLOv5s-LiteAttn | 5.50 | 13.40 | 95.8 | 97.1 | 140.0 | 11.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, Z.; Liang, Y.; Kong, N.; Liang, L.; Peng, W.; Yao, Y.; Qin, C.; Lu, X.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Lightweight Structure and Attention Fusion for In-Field Crop Pest and Disease Detection. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122879

Luo Z, Liang Y, Kong N, Liang L, Peng W, Yao Y, Qin C, Lu X, Xu M, Zhang Y, et al. Lightweight Structure and Attention Fusion for In-Field Crop Pest and Disease Detection. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122879

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Zijing, Yunsen Liang, Naimin Kong, Lirui Liang, Wenjun Peng, Yujie Yao, Chi Qin, Xiaohan Lu, Mingman Xu, Yining Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Lightweight Structure and Attention Fusion for In-Field Crop Pest and Disease Detection" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122879

APA StyleLuo, Z., Liang, Y., Kong, N., Liang, L., Peng, W., Yao, Y., Qin, C., Lu, X., Xu, M., Zhang, Y., Lin, C., Jiang, C., Li, M., Zheng, Y., Jiang, Y., & Lu, W. (2025). Lightweight Structure and Attention Fusion for In-Field Crop Pest and Disease Detection. Agronomy, 15(12), 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122879