Abstract

Paddy field leveling is the foundation of high-yield rice cultivation. In response to the current issues of low leveling accuracy and the lack of efficient multi-operation machinery, an Integrated Multi-operation Paddy Field Leveling Machine was designed in this study. This machine can complete soil crushing, stubble burying, mud stirring, and leveling in a single pass. Combined with an adaptive control system based on Global Navigation Satellite System—Real-Time Kinematic (GNSS-RTK) technology, it enables adaptive and precise paddy field leveling operations. To verify the operational performance of the equipment, field tests were conducted. The results showed that the machine achieved an average puddling depth of 14.21 cm, a surface levelness of 2.16 cm, an average stubble burial depth of 8.15 cm, and a vegetation coverage rate of 89.33%, demonstrating satisfactory leveling performance. Furthermore, to clarify the feasibility and superiority of applying this equipment in actual rice production, experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of different field leveling methods on early rice growth, yield, and its components. One-way analysis of variance was employed to examine the differences in agronomic indicators between the different field leveling treatments. The results indicated that using this equipment for paddy field leveling, compared to traditional methods and dry land preparation, can improve the seedling emergence rate, thereby laying a solid population foundation for the formation of effective panicles. It also promoted root growth and development and increased the total dry matter accumulation at maturity, thereby contributing to high yield formation. Over the two-year experimental period, the rice yield remained above 9.8 t·hm−2. This research provides theoretical support and practical guidance for the further optimization and development of subsequent paddy field preparation equipment, thereby promoting the widespread application of this technology in rice production.

1. Introduction

Rice, as a major global food crop, relies on full mechanization of its production process as a key factor in ensuring food security and agricultural sustainable development [1,2]. Paddy field leveling is the foundation of high-yield rice cultivation. High-quality land preparation helps create a favorable seedbed and seedling bed environment for aerial seeding and mechanical transplanting operations [3,4], promotes root growth and development [3], and also serves as a prerequisite for achieving uniform irrigation and water layer management, contributing to a more coordinated water–fertilizer environment [5,6,7]. Furthermore, the land preparation process can remove weeds, incorporate crop residues from the previous season, and facilitate the thorough integration of base fertilizer with the soil, thereby improving fertilizer utilization efficiency [8].

However, traditional paddy field leveling involves multiple labor-intensive steps, including plowing, rotary tillage, soil crushing, puddling, and leveling [6,9]. The quality of each operation heavily relies on the operator’s experience, leading to issues such as low efficiency, inconsistent leveling precision, and inadequate stability [3,10,11]. This often results in poor field surface leveling, which can cause uneven rice growth environments and unequal distribution of water and fertilizers, making it difficult to meet the demands of modern agriculture for large-scale and standardized production. Therefore, Zuoxi Zhao et al. [12] developed a leveling control system based on micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) inertial sensors, which effectively improved the attitude control accuracy of the leveler in complex field conditions but failed to adequately address the leveling precision issue. Building upon this work, Hao Zhou et al. [13] designed a laser-controlled paddy field leveler and puddler. By integrating laser transmission/reception and a hydraulic control system, they achieved automatic elevation adjustment of the leveling blade, significantly improving the leveling precision in paddy fields. İrsel G. et al. [14] successfully adapted an automated tilt adjustment and tracking force system to laser levelers, enhancing the equipment’s autonomous capability to cope with undulating terrain.

While laser leveling technology delivers satisfactory leveling precision, its implementation entails substantial operational costs. Furthermore, the system’s accuracy remains constrained by the deployment of ground reference points and proves vulnerable to degradation under adverse weather conditions such as precipitation and fog. These limitations have consequently directed contemporary land leveling equipment toward satellite navigation systems, which have gained widespread adoption owing to their exceptional accuracy, elimination of ground reference requirements, and extensive applicability [15]. For example, Gaolong Chen et al. [16] designed a GNSS-supported paddy field leveler. This system utilizes a GNSS receiver to monitor the real-time height of the leveling blade and controls a hydraulic system to adjust the blade height. It incorporates a support rod to reduce the amplitude of height variation, effectively enhancing the reliability of high-speed precision leveling operations. Zhou Jun et al. [17] developed an integrated paddy field rotary tillage and leveling machine. This machine relies on dual-antenna RTK GNSS technology to acquire the implement’s elevation and tilt angle information, achieving a leveling accuracy of approximately 3 cm. Furthermore, other systems such as the Field Level from the United States and the GNSS leveling control system from Switzerland have also been widely applied [18,19].

Previous research has verified the feasibility and superiority of applying GNSS-RTK technology to paddy field leveling and has also made numerous optimizations and improvements to paddy field leveling mechanisms [20,21]. However, with the recent rise of the unmanned farm concept, multiple combined operations have become a trend. Existing paddy field leveling equipment suffers from significant technological limitations, being capable only of performing single leveling operations or basic two-operation combined tasks such as “rotary tillage + leveling” [22,23]. They are unable to synchronously complete the four core land preparation processes: soil crushing, stubble burying, mud stirring, and leveling. This not only requires multiple field passes, increasing operational costs and time, but also risks over-compacting the soil structure of the field. Consequently, these machines struggle to meet the high-efficiency operational demands of unmanned farms, representing a major technological gap that urgently needs to be addressed in the current field of paddy field preparation equipment. Furthermore, existing research has focused primarily on measuring and optimizing the engineering performance parameters of land preparation equipment (such as levelness and puddling depth). It has failed to establish quantitative threshold relationships between these parameters and key agronomic indicators like early-stage seedling emergence rate and root development in rice. Nor has it elucidated the underlying mechanisms through which different levels of land preparation accuracy affect dry matter accumulation during the rice growth period and yield components. This oversight hinders the high-quality advancement of paddy field preparation technology towards “engineering–agronomy synergy.” To address these issues, this paper designs an Integrated Multi-operation Paddy Field Leveling (IMPFL) machine. This implement consolidates the functions of soil crushing, stubble burying, mud stirring, and leveling into a single unit, enabling the completion of multiple land preparation processes in one pass. Coupled with an adaptive control system based on GNSS-RTK technology, it achieves adaptive and precise land leveling operations. The objectives of this study are: (1) to develop paddy field preparation equipment that integrates the four functions of soil crushing, stubble burying, mud stirring, and leveling, thereby overcoming the limitation of single-operation processes in existing machinery; (2) to construct an adaptive land preparation control system based on GNSS-RTK technology, realizing the precision and automation of land preparation operations; and (3) to systematically evaluate the equipment’s operational quality indicators—such as puddling depth, surface levelness, stubble burial depth, and vegetation coverage rate—through field experiments. Furthermore, to analyze its effects under different land preparation methods on rice seedling emergence rate, root development, dry matter accumulation, and yield components, thereby clarifying its practical applicability in rice production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Design and Working Principle of IMPFL Machine

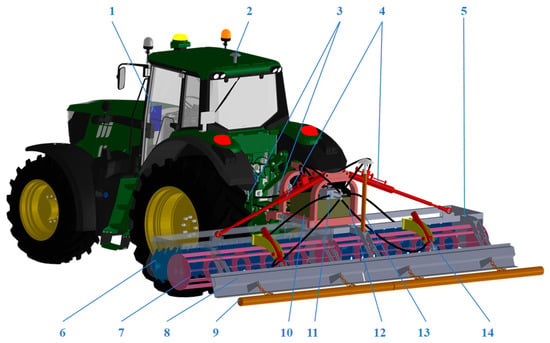

The IMPFL is an original and newly designed implement. Its overall structure is shown in Figure 1. It primarily consists of vehicle-mounted control terminal, differential signal antenna, GNSS-RTK receiver, frame, left and right lifting cylinders, left and right folding cylinders, scraper plate adjustment cylinder, hydraulic station, integrated valve bank, notched disc harrow, slurry roller, scraper plate, and compaction roller, among other components. The entire implement is connected to the tractor via a three-point hitch. The vehicle-mounted control terminal is installed in the tractor cabin, while the GNSS-RTK receiver is mounted on one side of the frame. The hydraulic station and integrated valve bank are positioned in the center of the frame and are connected to the various hydraulic cylinders through hydraulic hoses. The remaining operational components are symmetrically arranged along the central axis. The symmetrical folding of the implement is achieved by adjusting the extension and retraction of the folding cylinders, facilitating transport during cross-regional operations. During operation, the implement is fully deployed, with the folding cylinders maintained in a fully extended state. Its core technical parameters are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the IMPFL machine: 1: vehicle-mounted control terminal, 2: differential signal antenna, 3: left and right lifting cylinders, 4: left and right folding cylinders, 5: frame, 6: notched disc harrow, 7: slurry roller, 8: scraper plate, 9: compaction roller, 10: hydraulic station, 11: integrated valve bank, 12: hydraulic hose, 13: GNSS-RTK receiver, 14: scraper plate adjustment cylinder.

Table 1.

Product Specifications of the 1ZS-520B Beidou Satellite Paddy Field Puddling and Leveling Machine.

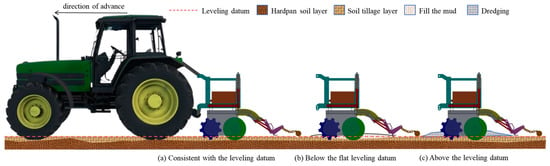

During the land preparation process, the notched disc harrow and the slurry roller rotate under the combined action of traction force and soil friction. This breaks up large soil clods, presses and buries the root systems of previous crops, and thoroughly mixes water and soil to form a uniform mud layer. The scraper plate is responsible for leveling the soil surface after puddling, moving soil from higher areas to lower areas. The compaction roller, connected via a chain at the rear, provides a final precision leveling function while moderately compacting the topsoil to prepare an optimal seedbed environment for subsequent sowing or transplanting. Throughout this process, the GNSS-RTK receiver continuously monitors the machine’s tilt angle and the scraper plate’s elevation, transmitting this data to the vehicle-mounted control terminal. The terminal performs integrated calculations based on the tractor’s attitude, pre-collected field elevation data, and the set leveling benchmark parameters. It then dynamically adjusts the extension/retraction of the left and right lifting cylinders and the scraper plate adjustment cylinder based on actual conditions. This ensures the implement remains level and maintains the scraper plate at the designated leveling benchmark. Specifically, when the tractor tilts, the vehicle-mounted control terminal sends adjustment commands to the integrated valve bank, controlling the hydraulic circuits of the left and right lifting cylinders to achieve automatic balance correction for the implement. When the scraper plate’s elevation deviates from the benchmark, the scraper plate adjustment cylinder extends or retracts, causing the blade to rise, lower, or tilt at a slight angle. This enables the movement of soil from higher to lower areas, as illustrated in Figure 2. This cyclic process ultimately enables the completion of four key operations—soil crushing, stubble burying, mud pulverization, and land leveling in a single pass, significantly enhancing operational efficiency.

Figure 2.

Working principle of the IMPFL machine.

2.2. Field Experiments

To evaluate the operational performance of the IMPFL machine in actual paddy field conditions, this study referred to the standards of the People’s Republic of China, GB/T 24685-2021 [24] and GB/T 5262 [25], to measure the puddling depth, surface levelness after operation, stubble burial depth, and vegetation coverage rate. These measurements were used to quantitatively analyze its leveling accuracy and operational effectiveness. According to the standard requirements, the average puddling depth should be ≥10 cm, the surface levelness after operation should be ≤5 cm, the average stubble burial depth should be ≥5 cm, and the vegetation coverage rate should be ≥80%.

2.2.1. Experiment Time and Location

The experiment was conducted on 25 June 2023, at the southern rice cultivation base in Gu Village, Jinxi Town, Kunshan City, Jiangsu Province, China (120°52′12.671′′ E, 31°10′32.639′′ N). The soil type in the experimental area was clay, with the previous crop being rapeseed. The experimental plot measured 72 m × 72 m, exhibiting noticeable local undulations with a maximum elevation difference of approximately 29.1 cm. Prior to the experiment, the plot underwent shallow rotary tillage and was flooded for 72 h. The surface water depth was maintained at 3–5 cm, with a mud depth of 12–15 cm. The prototype of the IMPFL machine is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Prototype of the IMPFL machine.

2.2.2. Experiment Indicators and Methods

The four indicators selected in this section—puddling depth, surface levelness, stubble burial depth, and vegetation coverage rate—are all core operational performance evaluation metrics for the IMPFL machine. Their selection strictly adheres to national standards such as GB/T 24685-2021 and GB/T 5262. The aim is to quantitatively assess the land preparation capability of the IMPFL from an engineering and technical perspective, thereby establishing a qualified seedbed foundation for subsequent rice cultivation. This forms a clear distinction from the indicators used in Section 2.3, such as seedling emergence rate and root traits, which are employed for analyzing agronomic output. The specific measurement methods for each indicator are as follows.

- (1)

- Puddling depth

The puddling depth was measured during two round-trip passes. Eleven measurement points were randomly selected on each side of the implement (22 points in total). At each measurement point, a steel ruler was used to vertically measure the distance between the lowest point of the slurry roller blade end and the sedimented mud surface. This vertical distance represents the puddling depth at that measurement point. The calculation formula is as follows:

where is the average puddling depth (cm), X is the puddling depth at each measurement point (cm), and n1 is the number of measurement points, n1 = 22.

- (2)

- Surface leveling accuracy

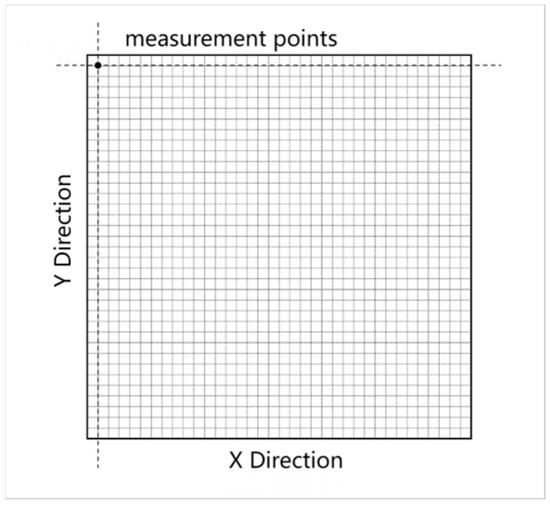

The measurement of surface levelness is based on ground elevation data. In the experiment, elevation measurement was carried out using the X15 video measurement RTK (Shanghai Huace Navigation Technology Ltd., Shanghai, China), as shown in Figure 4 below. Before the experiment, a 2 m × 2 m measurement grid comprising a total of 1296 measurement points was established in the experiment area, as shown in Figure 5. Before and after the operation, the pre-calibrated RTK rover was used to accurately measure and record the initial elevation data of all 1296 grid points point by point. The surface levelness (S) before and after the operation was then statistically analyzed and calculated using the following formula:

where aj is the elevation of the measurement point (cm), is the average height of all measurement points in the experiment (cm), and N is the number of measurement points in the field.

Figure 4.

X15 Video-based RTK Measurement.

Figure 5.

Layout of Data Collection Points.

It should be noted that the post-operation elevation measurement must be conducted no earlier than 2 h after the operation to avoid measurement inaccuracies caused by inadequate settlement of the mud slurry.

- (3)

- Stubble burial depth

The stubble burial depth was determined by randomly selecting 11 measurement points within the experimental area. At each point, a steel ruler was used to vertically measure the distance between the sedimented mud surface and the midpoint of the submerged stubble. The arithmetic mean of all 11 measurements was calculated as the average stubble burial depth, using the following formula:

where is the average stubble burial depth (cm), H is the stubble burial depth at each measurement point (cm), and n2 is the number of measurement points, n2 = 22.

- (4)

- Vegetation coverage rate

The vegetation coverage rate was determined within the experimental area using the ‘five-point sampling method’. Within the experimental area, five 1 m × 1 m quadrats were randomly selected using the ‘five-point sampling method’. All preceding crop vegetation (rapeseed stubble) within each quadrat was cut off at ground level, collected, washed, dried, and then weighed using an HZT-A2000 electronic balance (measurement range: 0–2000 g, accuracy: 0.01 g) manufactured by Fuzhou Huazhi Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The average vegetation density before operation was calculated using the following formula:

where Bb is the vegetation density before operation (g∙m−2), G is the vegetation mass at each measurement point (g), and A is the total area of the five-point sampling, A = 5 m2.

Figure 6.

Quadrat (1 m × 1 m) of previous crop vegetation.

Figure 7.

Weighing of dried vegetation.

After the operation, the vegetation floating on the mud slurry and water surface within the quadrats was collected, and its mass was weighed. The vegetation coverage rate was calculated using Formula (5):

where F is the vegetation coverage rate (%), and Ba is the vegetation density after operation (g∙m−2).

2.3. Effects of Different Field Leveling Methods on Early Rice Growth, Yield and Components

To validate the superiority of the IMPFL machine in practical rice production, this study conducted a comparative experiment using aerial seeding as the application scenario to evaluate different land leveling methods. By examining rice seedling establishment in early growth stages and yield components at maturity under various leveling treatments, this research further elucidates the practical implications of paddy field leveling quality for rice production.

2.3.1. Experimental Design

This experiment was conducted from 2023 to 2024 at the aforementioned rice cultivation base. The soil type in the experimental area was clay, the previous crop was rapeseed, and the rice cultivar used in the experiment was Nanjing 9108 (a japonica rice variety). The climatic conditions during the rice-growing seasons across the two years are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of climatic conditions during the rice-growing seasons in 2023–2024.

The experiment included three field leveling treatments: traditional multi-operation leveling (CK), dry leveling (DL), and one-pass leveling using the IMPFL machine proposed in this study (OL). All three methods were based on full straw incorporation (where straw from the previous crop was crushed to approximately 10 cm and directly returned to the field during harvest). The CK treatment followed the local conventional field leveling method, which involved multiple steps, including deep plowing, soil crushing, and puddling and leveling. The experimental treatments involving different paddy field leveling methods are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental treatments for different paddy field leveling methods.

A randomized complete block design was adopted for the experiment, with three replicates per treatment. Each plot covered an area of 500 m2, and different treatments were separated by bunds. This study selected aerial seeding as the planting scenario, based primarily on the practical production context and experimental needs of the research area. On one hand, aerial seeding has become an emerging mainstream planting model in Jiangsu Province in recent years, with its application area accounting for over 30% of the region during 2023–2024, making the experimental scenario highly relevant for practical reference. On the other hand, aerial seeding eliminates the seedling nursery and transplanting stages, with rice seeds landing directly on the field surface. Insufficient field surface levelness can easily lead to uneven water depth in localized areas, causing variations in seed germination environments and interfering with the uniformity of seed distribution from UAV sowing. Therefore, this model is far more sensitive to leveling quality than traditional mechanical transplanting or manual transplanting, allowing for a more precise verification of the impact of land preparation operations on rice growth. All treatments uniformly used the XAG P100 Pro unmanned aerial vehicle (Guangzhou XAG Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) for aerial seeding, with a seeding rate set at 120 kg·hm−2. The fertilizer application was consistent across all treatments, with each hectare receiving a total of 300 kg of pure N. This was applied as a one-time basal application in the form of fast-acting urea, 40-day controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer, and 100-day controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer, blended at a ratio (by pure N) of 5:1:4. Phosphate and potash fertilizers were also applied once as a basal dressing before sowing or transplanting using a broadcast spreader, with rates of 130 kg P2O5 and 260 kg K2O per hectare. Water management, as well as pest and disease control, followed the local high-yield cultivation practices for direct-seeded rice.

2.3.2. Measurement Indicators and Methods

The indicators selected in this section—seedling emergence rate, seedling density, root traits, dry matter accumulation, and yield components—are all metrics for evaluating rice agronomic response and production efficiency. Their selection strictly adheres to classic research paradigms in the field of rice cultivation. The aim is to quantitatively assess, from an agronomic production perspective, the impact of the land preparation operations performed by the IMPFL machine on rice growth, development, and final yield. This complements the indicators used in Section 2.2.2 for evaluating the machine’s engineering performance, together forming a complete validation chain of “implement operation quality—seedbed microenvironment—rice agronomic output.” The specific measurement methods for each indicator are as follows:

- (1)

- Collection of early rice growth data

The foundational seedling density was determined at the two-leaf-one-heart stage. Within each treatment plot, representative 2 m2 areas reflecting field growth conditions were randomly selected for foundational seedling density, with five replications conducted. The number of emerged seedlings per unit area was investigated to calculate the foundational seedling density and seedling emergence rate. From each selected area, 15 uniformly growing seedlings were randomly sampled for indicator measurements. Seedling height was measured as the vertical distance from the stem base to the tip of the tallest leaf using a straight ruler. The seedlings were then separated into shoots and roots at the crown region. After deactivation at 105 °C for 30 min, the samples were dried at 80 °C until constant weight was achieved. The dry weights of shoots and roots were separately measured using an analytical balance. The washed and spread root systems were scanned using the WinRHIZO root analysis system (Beijing EcoTech Science and Technology Ltd., Beijing, China), with total root number and total root length automatically obtained through image analysis.

- (2)

- Yield and components

Prior to harvest, three survey points were selected in each plot to investigate Panicle number. At each point, five consecutive rows, each measuring 1 m, were surveyed. Based on the calculated average panicle number per plot, five sampling points (with 20 consecutive plants as one sampling point) were taken to investigate the number of grains per panicle and the seed-setting rate. A 1000-grain sample (dry seeds) was weighed, with three replicates (error ≤ 0.05 g), to calculate the 1000-grain weight. At maturity, a 10 m2 area was harvested from each plot, and the actual yield was calculated after sun-drying (adjusted to 14.5% moisture content).

- (3)

- Dry matter accumulation

At the tillering mid-stage, jointing stage, heading stage, and maturity stage, five representative hills of plants corresponding to the average tiller number in the sampling area were taken from each treatment. These samples were placed in an oven, deactivated at 105 °C for 30 min, and then dried at 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The dry weight was measured using a balance.

2.4. Data Processing

Data organization and visualization were performed using Microsoft Excel 2017. Statistical analysis was conducted with DPS V7.05 software. Significant differences were indicated with letters, where groups sharing the same letter indicate no significant difference between means, while different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

This study was conducted in two phases: the first phase (2023) involved a core operational performance verification experiment of the complete machine to evaluate its basic operational indicators, while the second phase (2023–2024) comprised an agronomic effect verification experiment in rice production to investigate the actual impact of the machine on rice growth and yield.

3.1. Field Experiment Results

The corresponding field experiment in this section was the core operational performance verification experiment for the IMPFL machine. Relying on standardized field experiment methods, four key indicators after the machine’s operation—puddling depth, surface levelness, stubble burial depth, and vegetation coverage rate—were quantitatively measured. The purpose was to verify whether these indicators meet the requirements of national standards such as GB/T 24685-2021 and GB/T 5262, thereby clarifying the operational reliability and effectiveness of the implement. The specific experiment results are as follows.

3.1.1. Puddling Depth

The experiment results for puddling depth are shown in Table 4. The overall average puddling depth was 14.21 ± 1.81 cm, with a maximum value of 18.7 cm and a minimum of 9.8 cm. These values meet the standard requirements for the paddy field plow layer and effectively form a mud layer suitable for transplanting. The maximum puddling depth reached 18.7 cm, while the minimum was 9.8 cm. The overall average puddling depth was 14.21 cm, which meets the standard requirements for the paddy field plow layer and effectively forms a mud layer suitable for transplanting. Analyzing the reasons for the excessive variation in data at individual measurement points, this may be attributed to variations in the natural mud depth of the field and the presence of debris in the field. For instance, the lower puddling depth on the right side of measurement point 9 may be due to obstacles such as stones in the plow layer of that area.

Table 4.

Puddling depth measurement data.

3.1.2. Surface Levelness

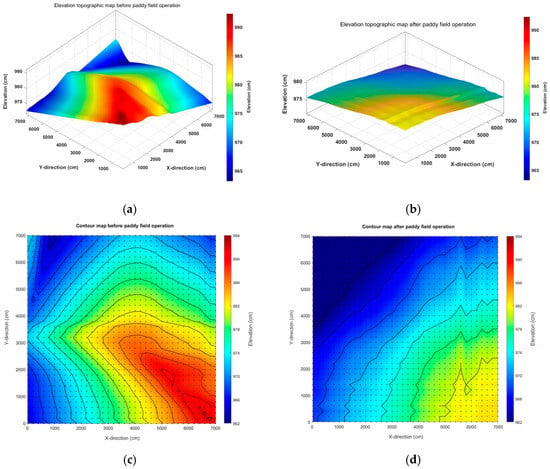

Based on the measured elevation data of the experiment area before and after the operation, the surface levelness was calculated, respectively, with specific data shown in Table 5. After processing the elevation data from 1296 measurement points before and after the operation, statistical analysis showed that the average elevation of the experiment plot before the operation was 9.782 m, with a maximum elevation difference of 29.1 cm and a surface levelness of 7.07 cm. After the operation, the average elevation of the experiment plot was 9.783 m, with a maximum elevation difference of 9.4 cm and a surface levelness of 2.16 cm. From the numerical changes alone, it can be observed that the elevation difference in the plot decreased significantly after the operation, with a reduction of 67.7%. The surface levelness after the operation was also far below the standard requirement (paddy field levelness ≤ 5 cm), with a reduction of 69.4%.

Table 5.

Summary of elevation calculation results.

To more intuitively reflect the changes in the levelness of the experiment field before and after the operation, three-dimensional visualizations and contour maps of the elevation data before and after the operation were generated and analyzed, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional terrain maps and contour maps before and after operation. (a) 3D topographic survey map before operation. (b) 3D topographic survey map after operation. (c) Contour map of elevation data before operation. (d) Contour map of elevation data after operation.

By comparing the 3D topographic maps and contour maps of the experiment field before and after the operation, it can be observed that the original terrain exhibited significant undulations from the lower-right to the upper-left direction, with pronounced elevation differences along the diagonal. After the operation, the inclined state of the terrain characterized by ‘higher in the lower-right and lower in the upper-left’ was not completely eliminated but was significantly alleviated. The maximum elevation difference within the area showed a marked reduction. Soil from the higher areas in the lower-right region was transported and redistributed to the central area by the scraper plate, resulting in a noticeable decrease in elevation, while depressions in the upper-left region were also partially filled.

3.1.3. Stubble Burial Depth

The experiment results for stubble burial depth are shown in Table 6. It can be observed that the stubble burial depth at all measurement points exceeded the standard requirement (stubble burial depth ≥ 5 cm), with the maximum stubble burial depth reaching 12.35 cm and an overall average stubble burial depth of 8.15 cm. This indicates that the stubble burial component of the equipment can effectively achieve the burial of root stubble, preventing poor root anchoring in the early stages of rice growth.

Table 6.

Stubble burial depth measurement data.

3.1.4. Vegetation Coverage Rate

The experiment results for vegetation coverage rate are presented in Table 7. Analysis of vegetation density data before and after operation shows a significant reduction in vegetation density per unit area, decreasing from the original 312.616 g∙m−2 to 33.356 g∙m−2 after operation. The overall vegetation coverage rate reached 89.33%, meeting the standard requirement of ≥80% vegetation coverage after leveling operations. These results demonstrate that the equipment can effectively pulverize and deeply incorporate residual materials from previous crops into the mud, thereby creating favorable growth conditions for subsequent crops.

Table 7.

Measurement results of vegetation density and coverage before and after operation.

Based on the experiment results and analysis of the above four indicators, after leveling operations with this equipment, the experiment field achieved an average puddling depth of 14.21 cm, a surface levelness of 2.16 cm, an average stubble burial depth of 8.15 cm, and a vegetation coverage rate of 89.33%, all of which meet the standard requirements. Compared with the actual field conditions before and after the operation, as shown in Figure 9, it can be observed that the equipment effectively pulverizes and buries the residual root systems and straw of the previous crop, delivers excellent puddling performance, and provides superior leveling effects. It effectively eliminates elevation differences on the field surface by transporting and redistributing soil from higher areas to lower areas, thereby creating a favorable seedbed environment for subsequent mechanical transplanting or aerial seeding operations.

Figure 9.

Comparison of field surface conditions before and after operation. (a) Field surface conditions before operation. (b) Field surface conditions after operation.

3.2. Effects of Different Field Leveling Methods on Early Growth, Yield and Components in Rice

The corresponding experiment in this section was the verification experiment for the agronomic effects of the IMPFL machine on rice production. Using traditional multi-operation leveling and dry leveling as controls, this experiment investigated the effects of applying the IMPFL machine for one-pass land preparation on early growth characteristics, dry matter accumulation throughout the entire growth period, and yield components of rice. The specific experiment results are as follows.

3.2.1. Rice Seedling Growth Characteristics

Table 8 summarizes the experimental data on early growth characteristics of rice under different land preparation methods. The results indicated that across both years, the seedling growth characteristics consistently followed the order OL > DL > CK. With the exception of a few instances where differences between DL and OL treatments were not statistically significant, all other indicators showed significant differences among treatments. The OL treatment demonstrated significant improvements in all early growth parameters compared to CK. Specifically, increases were observed in foundational seedling density (4.07–5.15%), seedling emergence rate (5.92–6.14%), seedling height (23.05–26.00%), shoot dry weight (20.82–22.00%), root dry weight (21.78–25.18%), and root length (8.91–9.21%). While some early growth parameters between OL and DL treatments showed significant differences across both years (particularly in seedling height, shoot dry weight, and root dry weight), no significant differences were found in foundational seedling density, seedling emergence rate, or root length. Both OL and DL treatments exhibited significantly improved early growth characteristics compared to CK.

Table 8.

Rice early growth characteristics under different field leveling methods.

3.2.2. Rice Yield and Components

Table 9 presents the experimental results of rice yield and yield components under different land preparation methods. The data demonstrated consistent yield patterns across all treatments, following the order OL > DL > CK, with slightly lower yields observed in 2024 compared to 2023. Specifically, the OL treatment showed yield increases of 0.71% and 4.18% over DL and CK, respectively, in 2023, and 1.54% and 3.89% in 2024, with all differences reaching statistical significance. Regarding yield components, significant differences were observed in effective panicles, grains per panicle, and seed-setting rate among the different land preparation methods. Both effective panicles and seed-setting rate followed the pattern OL > DL > CK, while grains per panicle exhibited an inverse relationship. The OL treatment increased effective panicles by 3.97% and 13.00% compared to DL and CK in 2023, and by 3.20% and 11.07% in 2024. Conversely, the CK treatment showed higher grains per panicle than OL, with increases of 12.00% in 2023 and 9.92% in 2024. The seed-setting rate under OL treatment exceeded that of DL and CK by 0.15–0.43% and 0.63–1.67%, respectively, across both years. For 1000-grain weight, no significant difference was observed between OL and DL treatments, though both were statistically higher than CK. Comprehensive analysis indicates that although the grains per panicle under the one-pass leveling (OL) and dry leveling (DL) treatments were lower than that of the control treatment (CK), their superior performance in effective panicle number and seed-setting rate compensated to some extent for the deficiency in grains per panicle. Consequently, this led to higher final yields compared to the CK treatment. The negative correlation observed between effective panicle number and grains per panicle can be attributed to the population density effect: a higher effective panicle number intensifies inter-plant competition for resources such as light and nutrients, thereby limiting the grain development potential of individual panicles.

Table 9.

Rice yield and components under different field leveling methods.

3.2.3. Dry Matter Accumulation

Table 10 presents the experimental data on rice dry matter accumulation under different field leveling methods. The two-year experimental data revealed consistent trends in dry matter accumulation across growth stages, generally following the order OL > DL > CK. Additionally, dry matter accumulation under all treatments was higher in 2023 than in 2024. During the early growth stages (tillering, mid, and jointing stages), significant differences were observed only between OL and CK treatments, while DL showed no significant differences with the other two treatments. As growth progressed, the differences among treatments became increasingly distinct, reaching statistical significance at maturity. In 2023, the population dry matter accumulation at maturity under OL treatment increased by 8.94% and 10.76% compared to DL and CK, respectively. Similarly, in 2024, the corresponding increases were 6.96% and 10.49%. DL treatment showed modest improvements over CK, with increases of 1.67% (2023) and 3.31% (2024).

Table 10.

Rice dry matter accumulation under different field leveling methods.

3.3. Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that appropriate field leveling methods can improve soil physical structure and the tillage layer environment and promote early seedling emergence and root development in rice, thereby establishing a foundation for robust crop populations [26,27]. Regarding the early growth characteristics of rice under the three field leveling methods examined in this study, the OL treatment, which employed multi-operation puddling and leveling under satellite leveling system control, demonstrated superior performance in puddling depth, surface leveling accuracy, stubble burial depth, and vegetation coverage compared to the CK and DL treatments, resulting in better land preparation quality. The final experimental results not only surpassed the experimental results of the GNSS leveler developed by Gaolong Chen et al. [16] but also significantly enhanced comprehensive operational efficiency. Furthermore, the yield-increasing trend observed under the OL treatment in this study aligns with the findings reported by Devkota et al. [6] in laser-leveled fields, further confirming the positive impact of precision land leveling on rice yield. Yaligar et al. [11] noted in their research that improving field surface levelness can create a more consistent soil environment for rice growth. Meanwhile, the DL treatment, which utilized a laser leveler for dry land preparation, also exhibited better preparation quality than the CK treatment. Consequently, the early growth characteristic indicators across the three treatments generally followed the order OL > DL > CK, with significant differences observed in emergence effect and root length. These variations subsequently led to significant differences in seedling dry weight.

Furthermore, studies have indicated that appropriate field leveling methods can improve root morphology and enhance root physiological activity, promoting above-ground growth in rice plants [28,29]. This enhancement subsequently increases dry matter accumulation during the middle and late growth stages, ultimately raising the total dry matter accumulation at maturity—a crucial physiological characteristic for high rice yield [30,31,32]. In our experiments, the dry matter accumulation under the OL treatment was significantly higher than that under the DL and CK treatments during the middle and late growth stages, particularly at maturity. Devkota et al. [6] found in the rice–wheat system of eastern India that laser leveling could significantly improve irrigation water productivity and tended to increase rice and wheat yields. Particularly after levelness improvement, enhanced water use efficiency promoted crop growth and dry matter accumulation. Therefore, this explains the higher yield observed under the OL treatment compared to the DL and CK treatments. Specifically, regarding yield components, the OL treatment showed higher effective panicle number and seed-setting rate compared to the DL and CK treatments. However, due to the unified fertilization management adopted in the experiment, the grain number per panicle was relatively lower under the OL treatment. Nonetheless, the superior performance in the former two components ensured the final high yield formation, reaching 9.96 t·hm−2 in 2023.

In conclusion, it can be considered that appropriate field leveling methods can promote early growth and development of rice, ensuring a sufficient number of basic seedlings and improving seedling emergence rate, thereby laying a solid population foundation for the subsequent formation of effective panicles. Simultaneously, appropriate field leveling methods create favorable soil conditions for root growth, enhance root activity, promote dry matter accumulation during the middle and late growth stages, maintain high material production capacity during the grain filling period, and ultimately increase total dry matter accumulation at maturity, consequently contributing to high yield formation.

4. Conclusions

Addressing the current issues of low precision in paddy field leveling and the lack of efficient combined operation equipment, this paper designed an IMPFL machine capable of performing soil crushing, stubble burying, mud stirring, and leveling in a single pass. Integrated with an adaptive control system based on GNSS-RTK technology, it achieves adaptive and precise paddy field leveling operations. Compared to existing paddy field preparation equipment, the core contribution of this study lies in the first-time integration of the four core land preparation processes into one implement, utilizing GNSS-RTK for precise control. This approach balances operational efficiency with leveling precision, overcoming the limitations of traditional equipment, such as single-operation processes and the need for multiple field passes. Field experiment results demonstrated that the implement effectively pulverizes and buries residual root systems and straw from the previous crop, delivers excellent puddling performance, and provides superior leveling effects by effectively eliminating surface elevation differences. Post-operation measurements showed an average puddling depth of 14.21 cm, surface levelness of 2.16 cm, average stubble burial depth of 8.15 cm, and vegetation coverage rate of 89.33%, all meeting standard requirements. Two-year comparative production experiments revealed that using this equipment for land preparation significantly enhanced early rice growth compared to traditional methods and dry land leveling, specifically through increased foundational seedling density, seedling emergence rate, and root length. This established a solid population foundation for subsequent effective panicle formation. It also promoted dry matter accumulation during the mid- to late growth stages, ensured high biomass production capacity during the grain filling period, and increased total dry matter accumulation at maturity, ultimately contributing to high yield formation. Over the two-year experimental period, rice yield remained above 9.8 t·hm−2. Therefore, this land preparation method is considered applicable and advantageous for practical rice production.

This study still has certain limitations. The experimental plots were concentrated on clay soil types in the Kunshan region, and validation has not been conducted on other soil textures, such as loam or sandy loam, or in different rice-growing ecological zones, resulting in insufficient data on the implement’s general applicability. Furthermore, the experimental period spanned only two rice seasons, lacking long-term durability monitoring of the machine’s service life, and a systematic analysis of operational costs and benefits has not been conducted. Based on this, future work could further expand the experimental regions and soil types to verify the environmental adaptation boundaries of the implement, conduct long-term field service experiments to optimize the structure of vulnerable components, simultaneously quantify its comprehensive lifecycle benefits, and explore its integrated application with precision agriculture technologies such as unmanned agricultural machinery and variable-rate fertilization. This would provide more comprehensive support for the large-scale promotion of this equipment and its adaptation to smart farms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., J.H., Q.H. and H.S.; methodology, Y.S., Q.H. and H.S.; software, J.H., X.S. and J.X.; validation, Y.S. and X.S.; formal analysis, Y.S. and Q.H.; investigation, J.H., J.X. and P.X.; data curation, Y.S., J.H. and P.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., X.X. and Q.H.; visualization, Y.S.; supervision, Y.S., X.X. and Q.H.; project administration, Y.S., Q.H. and H.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S., Q.H. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD2300502) and Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (BE2022338).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate the assistance provided by team members during the experiments. Additionally, we sincerely appreciate the work of the editor and the reviewers of the present paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Castelein, R.B.; Broeze, J.J.; Kok, M.G.; Axmann, H.B.; Guo, X.X.; Soethoudt, J.M. Mechanization in rice farming reduces greenhouse gas emissions, food losses, and constitutes a positive business case for smallholder farmers—Results from a controlled experiment in Nigeria. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 8, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, W.; Botero-R, J.C.; Luu, P.Q. Mechanization in land preparation and irrigation water productivity: Insights from rice production. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2024, 40, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Roel, A.; Faria, L.; Massey, J.; Parfitt, J. Land-forming for irrigatio (LFI) on a lowland soil protects rice yields while improving irrigation distribution uniformity. Precis. Agric. 2022, 24, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós-Vargas, J.; Romanelli, T.L.; Rascher, U.; Agüero, J. Sustainability Performance through Technology Adoption: A Case Study of Land Leveling in a Paddy Field. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Luo, H.W.; He, L.X.; Mao, T.; Lai, R.F.; Tang, X.R.; Tang, Q.Y.; Hu, L. The effect of plough tillage on productivity of ratooning rice system and soil organic matter. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 7641–7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, K.P.; Yadav, S.; Humphreys, E.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, V.; Malik, R.; Srivastava, A.K. Land gradient and configuration effects on yield, irrigation amount and irrigation water productivity in rice-wheat and maize-wheat cropping systems in Eastern India. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xing, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, H. Effects of Mechanically Transplanting Methods and Planting Densities on Yield and Quality of Nanjing 2728 under Rice-Crayfish Continuous Production System. Agronomy 2021, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zeng, F.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Hilario, P.; Ren, T.; Lu, S. Integrated rice management simultaneously improves rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency in various paddy fields. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Luo, C.; Liu, G. Multiobjective path optimization for autonomous land levelling operations based on an improved MOEA/D-ACO. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, W.; He, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhao, R.; Tang, L.; Du, P. Roll angle estimation using low cost MEMS sensors for paddy field machine. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 158, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaligar, R.; Balakrishnan, P.; Satishkumar, U.; Kanannavar, P.S.; Halepyati, A.S.; Jat, M.L.; Rajesh, N.L. Land Levelling and Its Temporal Variability under Different Levelling, Cultivation Practices and Irrigation Methods for Paddy. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 3784–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, B.; Tian, X.; Hu, L.; Li, Y. Leveling control system of laser-controlled land leveler for paddy field based on MEMS inertial sensor fusion. Trans. CSAE 2008, 24, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, L.; Luo, X.; Tang, L.; Du, P.; Zhao, R. Design and experiment of the beating-leveler controlled by laser for paddy field. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2019, 40, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İrsel, G.; Altinbalik, M.T. Adaptation of tilt adjustment and tracking force automation system on a laser-controlled land leveling machine. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 150, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hu, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, P.; He, J.; Huang, P.; Zhao, R.; Feng, D.; Tu, T. A review of global precision land-leveling technologies and implements: Current status, challenges and future trends. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, R.; Feng, D.; Tian, L.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Structural Design and Test of Supported Paddy-field Leveling Machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 252–260+274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y. Development of Paddy Field Rotary-leveling Machine Based on GNSS. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, M.; Moussa, H. Accurate Height Determination in Uneven Terrains with Integration of Global Navigation Satellite System Technology and Geometric Levelling: A Case Study in Lebanon. Computation 2024, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Li, Q.; Ye, W.; Liu, G. Development of a GNSS/INS-based automatic navigation land levelling system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, L.; Luo, X.; Tang, L.; Du, P.; Mao, T.; Zhao, R.; He, J. Design and test of laser-controlled paddy field levelling-beater. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yue, M.; Yang, L.; Luo, X.; He, J.; Man, Z.; Feng, D.; Liu, S.; Liang, C.; Deng, Y.; et al. Design and Test of Intelligent Farm Machinery Operation Control Platform for Unmanned Farms. Agronomy 2024, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, R.; Xi, X. Multiple Leveling for Paddy Field Preparation with Double Axis Rotary Tillage Accelerates Rice Growth and Economic Benefits. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Luo, H. Design and experiment of the upright cone roller active extrusion ridge and furrow shaping device for cold waterlogged paddy field. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 24685-2021; Puddling and Fertilizing Land Leveler for Paddy Field. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 5262-2008; Agricultural Machinery Testing Conditions-General Rules for Measuring Methods. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Susanti, Z.; Sakai, C.; Tafakresnanto, C.; Sasmita, P.; Abdurachman, H. Direct seeding rice: A solution to improve establishment of rice under unpredictable climate condition. BIO Web Conf. 2025, 155, 01031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jat, R.K.; Meena, V.S.; Kumar, M.; Jakkula, V.S.; Reddy, I.R.; Pandey, A.C. Direct Seeded Rice: Strategies to Improve Crop Resilience and Food Security under Adverse Climatic Conditions. Land 2022, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Liao, P.; Khan, A.; Hussain, I.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, I.; Wei, B.; Jiang, L. Smash ridge tillage strongly influence soil functionality, physiology and rice yield. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 28, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Han, S.; He, G. Smash-ridging cultivation improves crop production. Outlook Agric. 2022, 51, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, G.; Zhai, C.; Huo, Z.; Dai, Q. Analysis on production characteristics of indica rice in super hybrid. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2007, 21, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.-W.; Hua, J.; Zhou, N.-B.; Zhang, H.-C.; Chen, B.; Shu, P.; Huo, Z.-Y.; Zhou, P.-J.; Cheng, F.-H.; Huang, D.-S.; et al. Difference in yield and population characteristics of different types of late rice cultivars in double-cropping rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 2015, 41, 1220–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xing, Z.; Gong, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Q.; Huo, Z.; Xu, K.; Wei, H.; Guo, B. Study on population characteristics and formation mechanisms for high yield of pot-Seedling mechanical transplanting rice. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2014, 47, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).