Abstract

Managed disturbances and their consequences for plant community structure, productivity, and foliar nutrients in the habitat of the endangered Eld’s deer remain inadequately characterized. We assessed the effects of prescribed fire (PF), mechanical mowing (MM), and their combination (PF_MM) on plant communities in the Datian National Nature Reserve of Hainan, China. Our findings demonstrated that the PF_MM treatment produced the greatest number of species (38 species, representing increases of 26.6% and 72.7% compared to PF and MM, respectively) and diversity indexes, indicating enhanced structural stability relevant to ecological conservation. In contrast, MM yielded the highest aboveground biomass (AGB) and the highest foliar nitrogen (N, 14.28 g kg−1), phosphorus (P, 2.08 g kg−1), and potassium (K, 3.61 g kg−1) concentrations, but concurrently promoted shrub dominance, potentially risking long-term nutrient depletion and functional group imbalance. Legume (Fabaceae) richness was negatively associated with foliar P and K, which is consistent with the nutrient dilution effect often observed in more diverse plant communities. Structural equation modeling indicated that treatment effects on AGB were mediated by the importance value of Fabaceae, whereas treatment effects on foliar N and P were expressed both directly and indirectly via the richness of Fabaceae and other families. Consequently, no single management approach can simultaneously enhance all desired metrics or indices. New management strategies or technologies should be explored to balance biodiversity conservation with improved pasture quality, thereby further supporting the recovery of Eld’s deer habitat while maintaining ecosystem health.

1. Introduction

Global savanna ecosystems are experiencing increasingly intense natural and anthropogenic disturbances, manifested as shifts in fire regimes, grazing pressure, and land use [1,2,3]. As two common grassland management practices, fire and mowing strongly shape successional trajectories and the nutritional functioning of plant communities by regulating light availability and the nutrient cycling [4,5]. The Datian National Nature Reserve in tropical Hainan, China, provides critical habitat for the Hainan Eld’s deer (Rucervus eldii), a nationally protected species whose survival depends directly on vegetation for food and shelter [6]. The structural attributes of plant communities (e.g., species composition, biomass allocation) together with their nutritional characteristics (e.g., foliar nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations) jointly determine habitat quality for Eld’s deer and regulate their foraging behavior [7]. Multiple studies have shown that pre-grazing plant diversity influences herbivore foraging patterns and, in turn, vegetation dynamics [8,9]. Herbivore foraging is also closely tied to forage nutritional composition [10]; for instance, food intake in the forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii) is positively correlated with leaf N and K concentrations [11].

Prescribed fire is widely used to remove surface litter, suppress shrub encroachment, and reduce wildfire risks [12]. Its effects on grassland ecosystems are dual: on one hand, by altering soil moisture–temperature conditions and enhancing nutrient availability, fire can promote vegetation recovery and often increase species diversity and productivity [13,14]; on the other hand, outcomes are strongly contingent on timing (e.g., autumn burns), frequency (e.g., repeated applications), and ecosystem context. Inappropriate use can reduce species diversity, lower soil water content, and even diminish long-term soil nitrogen storage [15,16]. Mowing modifies community structure by directly removing aboveground biomass (AGB), disrupting light competition, suppressing tall plants, promoting low-growing species, and ultimately enhancing both species diversity and ecosystem productivity [17,18]. Moderate mowing not only maintains high species richness but can also improve overall ecological functioning [19,20]. When combined, fire and mowing may produce non-linear effects, generating more complex drivers of community structure and nutritional functioning [21].

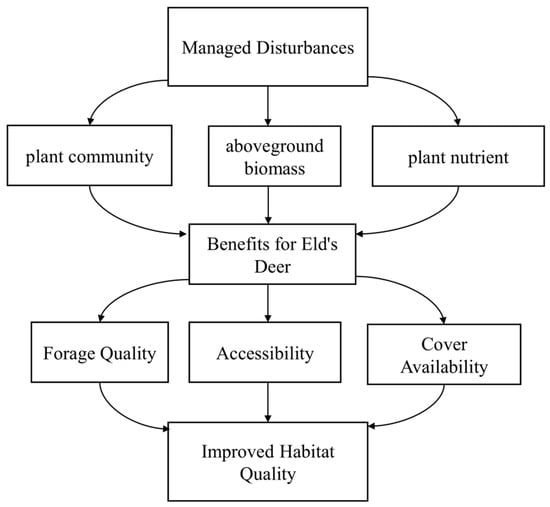

The limited area of the Datian Nature Reserve, combined with its unique peripheral conditions and habitat modifications, has facilitated the invasion of various alien plant species, which have formed extensive monodominant communities. Some of these invasive plants release allelochemicals that inhibit the growth of native vegetation, leading to reduced plant diversity [22,23]. This degradation of the habitat quality is notably manifested in the significantly diminished accessibility of plants favored by the Hainan eld’s deer, such as Grona reticulata and Grewia biloba, which are widely distributed and key dietary components for the species [24]. Since the 1990s, the Datian National Nature Reserve has employed prescribed fire, mowing, and their combination as primary grassland management measures to optimize forage resources and habitat conditions for Hainan Eld’s deer. However, the mechanisms by which these three treatments differentially influence key ecological indicators, including plant species composition, biomass structure, and nutrient status (e.g., N, P), remain unclear (Figure 1). We therefore address three questions: (1) How do the three management treatments affect plant community structure? (2) How do they influence aboveground biomass in the subsequent growing season? (3) What are their effects on plant nutrient concentrations?

Figure 1.

A conceptual model illustrating the proposed pathway by managed disturbances influence habitat suitability for Rucervus eldii.

Answering these questions will clarify how alternative disturbance regimes shape plant community structure and nutritional functioning. Moreover, shifts in these indicators are likely to regulate Eld’s deer foraging behavior and population health, underscoring the need for evidence-based, targeted habitat management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

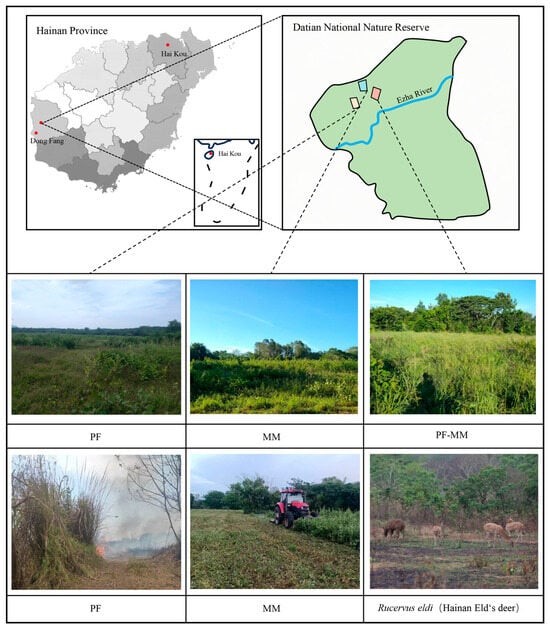

The Datian National Nature Reserve is located in Dongfang City, western Hainan Island, China (108°47′–108°49′ E, 19°05′–19°17′ N), and has a typical tropical monsoon climate (Figure 2). The reserve (1216 ha) has a mean annual temperature of 24.6 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1019 mm, most of which falls between July and October; the dry season can last up to eight months. Soils were generally acidic (pH = 5.89) and contained moderate levels of total organic carbon (22.76 g kg−1) and total nitrogen (1.12 g kg−1), while available phosphorus (3.94 mg kg−1) was relatively low, reflecting the weathered tropical conditions. Vegetation is classified into five types: lowland tropical savanna, psammophytic shrub thicket, deciduous monsoon forest, artificial pasture, and plantation forest. We focus on tropical savanna, the habitat most frequently used for foraging by the Hainan Eld’s deer (Rucervus eldii). The current population within the reserve is ~360 individuals, concentrated mainly north of the Ezhua River [25,26], corresponding to the three sampling areas shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study area in the Datian National Nature Reserve (Hainan, China), showing the location, major habitat types, and the distribution of implemented management treatment (PF, MM, PF_MM), and the Hainan Eld’s deer (Rucervus eldii) foraging in the reserve.

2.2. Experimental Design

Based on management practices maintained since the 1990s (Figure 2), we considered three grassland treatments:

- (1)

- Prescribed fire (PF): conducted in February (the driest period) to renew grassland vegetation;

- (2)

- Mechanical mowing (MM): carried out in September or October (end of the rainy season) with a stubble height of 20 cm;

- (3)

- Combined treatment (PF_MM): PF in February followed by MM in September or October.

Within each treatment, we delineated a 200 m × 200 m sampling zone. We then randomly placed six 1 m × 1 m quadrats (replicates) per treatment, with a minimum spacing of >50 m between any two quadrats, yielding a total of 18 quadrats. All field data collection (e.g., on plant community structure and soil properties) was uniformly conducted in the following August. This timing means the data for the PF treatment represent the regrowth approximately six months post-fire; data for the MM treatment represent the plant community state before the annual mowing event; and data for the PF_MM treatment capture the effect of fire but do not include the immediate effect of the subsequent mowing.

2.3. Data Collection

Community survey. During the peak growing season (August 2023), all vascular plant species within each quadrat were recorded, and plant height, cover, and abundance were measured simultaneously.

Diversity indices: For each quadrat we computed standard indices using species counts and relative abundances: species richness (S). Shannon-Wiener index (H), Simpson index (D), Margalef index (M), and Pielou evenness index (E) were used to assess the species diversity of plant communities [27,28]. These indices were calculated using the following formulas:

where S is the total number of species in the sample; is the total number of individuals in the sample; is the relative importance value of species i, calculated as the IV of species i divided by the sum of the IVs of all species in the quadrat [27,28]. The IV was calculated as (plant height + plant density + plant coverage)/3.

Functional group. Species were assigned to Poaceae, Fabaceae, or other families. For each functional group, the average height (Po.H, Fa.H, Ot.H), importance value (Po.IV, Fa.IV, Ot.IV), and richness (Po.R, Fa.R, Ot.R) were calculated.

Biomass and nutrients. Aboveground biomass (AGB, g/m2) was obtained by harvesting all aboveground material in each quadrat, oven-drying, and weighing [28]. Milled plant samples were analyzed for total N content (g/kg) (Kjeldahl method), total P content (g/kg) (molybdenum–antimony colorimetry), and total K content (g/kg) (flame photometry) [29]. Plant nutrient stocks (g/m2) were calculated as AGB multiplied by nutrient mass fraction (i.e., concentrations in g kg−1 converted to g g−1 before multiplication.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were compiled in Microsoft Excel 2021 and analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics 26, with a significance level of p = 0.05. One-way ANOVA tested treatment effects (PF, MM, PF_MM) on diversity indices, functional group traits, AGB, nutrient concentrations, and nutrient stock). When ANOVA was significant (p < 0.05), Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was applied, where different letters in figures/tables indicate significant differences. Pearson correlations among continuous ecological indicators were visualized via as heatmaps. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted in Amos 28.0 using maximum likelihood, and model fit was evaluated with χ2/df, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA [30]. The model fit was deemed acceptable if it met the standard thresholds of CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90, and RMSEA < 0.08, with values of CFI > 0.95, TLI > 0.95, and RMSEA < 0.06 indicating an excellent fit. Where applicable, model assumptions (normality, homoscedasticity) were checked and variables were transformed as needed.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Treatments on Aboveground Vegetation Community Structure

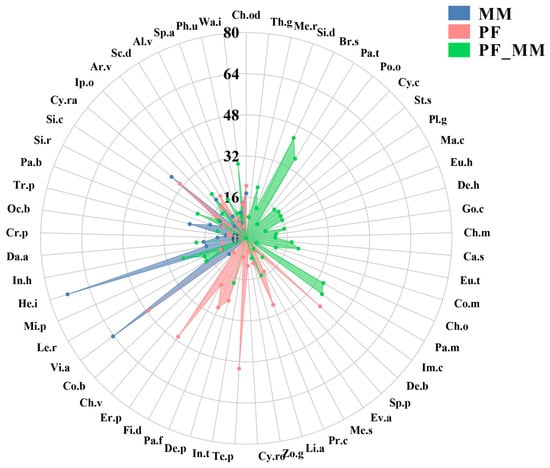

Across all treatments, we recorded 57 plant species (Figure 3). Regarding species richness among treatments, 22 species were in MM, 30 in PF, and 38 in PF_MM. Vegetation was dominated by species in Poaceae, Fabaceae, and Malvaceae. Dominant species in MM included Vitex agnus-castus, Helicteres isora, and Cynodon radiatus; in PF, V. agnus-castus, Eragrostis pilosa, and Tephrosia purpurea; and in PF_MM, Brachiaria subquadripara, Imperata cylindrica, and Paspalum thunbergii (Figure 3). V. agnus-castus was the only species that remained dominant under both the MM and PF treatments, indicating its high resilience to either individual disturbance. The PF_MM combined treatment led to a complete shift in the dominant plant community. The species that were dominant under the single-factor treatments (MM or PF) were replaced by a new set of species (B. subquadripara, I. cylindrica, P. thunbergii), suggesting a synergistic effect of the combined management practice.

Figure 3.

Radar chart comparing multi-dimensional community characteristics under three treatments. Lines indicate MM (blue), PF (red), and PF_MM (green). The 57 axes around the circumference correspond to species (Latin abbreviations; full names in Appendix A Table A1). The radial scale (0–80) represents species importance value (IV), calculated as the mean of relative height, relative density, and relative cover.

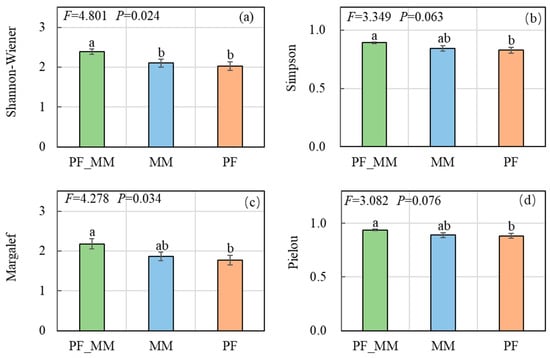

The Shannon-Wiener (H) differed among treatments (p = 0.024; Figure 4): PF_MM exceeded both MM and PF (p < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was found between the MM and PF. Although the overall effect on the Simpson (D) was not significant (p = 0.063), PF_MM was significantly higher than PF (p < 0.05). The Margalef (M) differed among treatments (p = 0.034), with PF_MM > PF (p < 0.05). The Pielou evenness (E) did not differ overall (p = 0.076), but PF_MM was higher than PF (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of treatments on plant diversity indices. (a) Shannon-Wiener index, (b) Simpson index, (c) Margalef index, (d) Pielou evenness index. Values represent mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments for each index (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). The F and p-values above each panel refer to the main effect of treatment from one-way ANOVA.

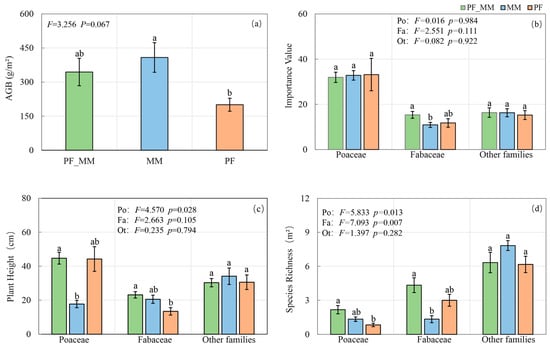

3.2. Effects of Treatments on Plant Functional Groups and Productivity

AGB was higher in MM than PF (p < 0.05), whereas PF_MM did not differ from either treatment (Figure 5a). Treatment had no significant effect on the importance values of Poaceae, Fabaceae, or other families (Po.IV, Fa.IV, Ot.IV; Figure 5b), although PF_MM was significantly higher than MM (p < 0.05). For plant height, Po.H differed among treatments (p = 0.028), with PF_MM > MM (p < 0.05). Fa.H did not differ overall, but PF_MM > PF (p < 0.05). Ot.H showed no treatment effect (Figure 5c). For species richness, Po.R differed among treatments (p = 0.013), with the PF_MM > PF (p < 0.05). Fa.R differed strongly (p = 0.007), with PF_MM > MM (p < 0.05). Ot.R did not differ among treatments (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Effects of treatments on plant functional groups and productivity. (a) Aboveground biomass (AGB); (b) Importance Value (IV); (c) Plant Height; (d) Species Richness. Plant functional groups: Poaceae (Po), Fabaceae (Fa), other families (Ot). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). The F and p-values denote one-way ANOVA results for the treatment effect in each panel.

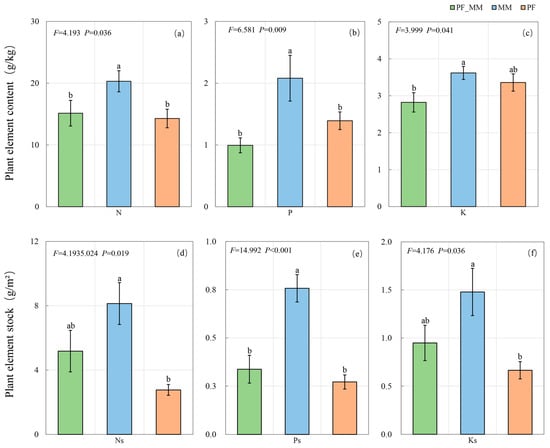

3.3. Effects of Treatments on Plant Nutrient Components

Treatments significantly affected both foliar nutrient concentrations and nutrient stocks (all p < 0.05; Figure 6). Foliar N and P concentrations were higher in MM than in both PF_MM and PF (p < 0.05). For K concentration, MM was higher than PF_MM (p < 0.05), whereas PF_MM and PF did not differ. For nutrient stocks, P stock in MM exceeded both PF_MM and PF (p < 0.05). N and K stocks in MM were higher than in PF (p < 0.05) and greater than in PF_MM, although the latter differences were not significant.

Figure 6.

Effects of treatments on foliar nutrient concentrations and stocks. (a) total nitrogen (N, g/kg), (b) phosphorus (P, g/kg), (c) potassium (K, g/kg), (d) nitrogen (Ns, g/m), (e) phosphorus (Ps, g/m), and (f) potassium (Ks, g/m). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). F and p-values indicate one-way ANOVA results.

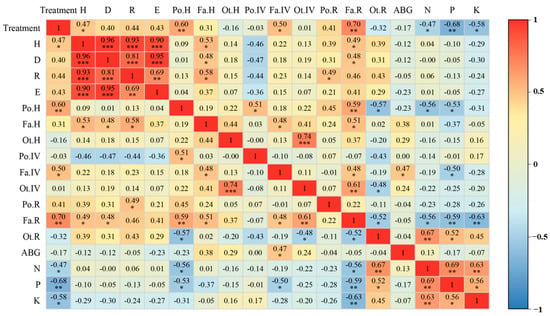

3.4. Correlation Analysis of Plant Community Structure and Plant Nutrition

Pearson correlations among plots showed positive associations of the treatment gradient with H (p < 0.05) and Fa.IV (p < 0.05), and strong positive associations with Po.H and Fa.R (both p < 0.01). In contrast, foliar N was negatively associated with treatment (p < 0.05), and foliar P and K showed strong negative associations (p < 0.01). Diversity indices (H, D, M, and E) were all strongly and positively intercorrelated, indicating concordant assessments of community diversity (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Pearson correlation heatmap among treatments, community structure, and foliar nutrients (17 indicators). Tile color encodes the correlation coefficient (r); color intensity denotes the strength of the Pearson correlation coefficient, from 1 (blue) to +1 (red). Asterisks indicate significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001); tiles without asterisks are not significant.

Regarding functional group traits, Fa.H was positively correlated with H, D, and M (p < 0.05). Po.H was strongly positively correlated with Fa.R (p < 0.01), and Ot.IV was strongly positively correlated with Ot.H (p < 0.001). Among nutrient indicators, P was negatively correlated with Fa.R (p < 0.05), and K was strongly negatively correlated with Fa.R (p < 0.01). N was negatively correlated with Po.H and Fa.R, but strongly positively correlated with Ot.R (p < 0.01). AGB was positively correlated with Fa.IV (p < 0.05) and showed weak correlations with other indicators (Figure 7).

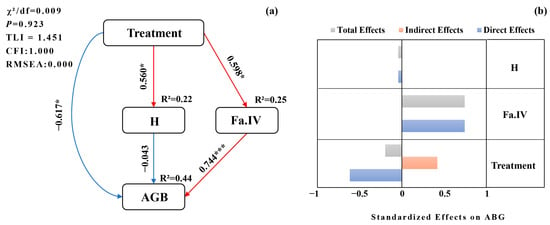

3.5. Effects of Treatments on Process of Productivity

SEM indicated that treatment had positive effects on both H and Fa.IV (p < 0.05). The effect of H on AGB was not significant (path coefficient −0.043), whereas Fa.IV had a significant positive direct effect on AGB (p < 0.05). Treatment had a negative direct effect on AGB, but a positive indirect effect via Fa.IV; because the magnitude of the direct effect exceeded that of the indirect effect, the total effect was negative. H and Fa.IV influenced AGB only through direct paths in final model. Overall, the primary pathway by which treatment affected AGB was the mediation “Treatment → Fa.IV → AGB,” identifying Fa.IV as a key mediator (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Structural equation model (SEM) of treatment on aboveground biomass (AGB). (a) Path diagram linking Treatment, H, Fa.IV, and AGB. Red arrows indicate positive paths; blue arrows indicate negative paths; values are standardized path coefficients. Significance: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. (b) Standardized effect decomposition showing total, indirect, and direct effects of each predictor on AGB. Bars: total (dark gray), indirect (light gray), direct (orange). The x-axis shows standardized effect size; the y-axis lists predictors. Model-fit indices (χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA) are reported in the panel or main text.

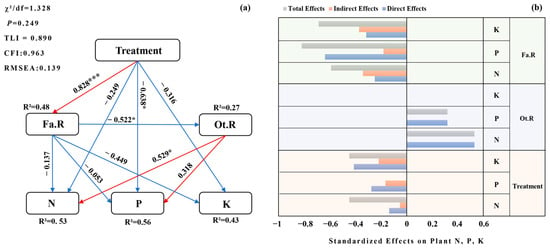

3.6. Effects of Treatments on the Process of Plant Nutrient Components

Treatment had a significant positive direct effect on Fa.R (p < 0.001). Fa.R exerted a negative direct effect on Ot.R (p < 0.05), indicating that increasing legume richness suppressed the richness of other families. Regarding foliar nutrient concentrations, Fa.R had no significant direct effects on N, P, or K, whereas Ot.R had a positive direct effect on N (p < 0.05). Treatment also had a negative direct effect on foliar P (p < 0.05; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

SEM of treatment effects on functional groups and foliar nutrients. (a) Path diagram showing direct and indirect effects of Treatment on foliar N, P, and K via Fa.R (Fabaceae richness) and Ot.R (richness of other families). Red/blue arrows denote positive/negative paths; numbers are standardized coefficients. Significance: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. (b) Standardized effect decomposition for N, P, and K showing total (dark gray), indirect (light gray), and direct (orange) effects of Treatment, Fa.R, and Ot.R. The x-axis shows standardized effect size; the y-axis lists predictors. Model-fit indices (χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA) are reported in the panel or main text.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Treatments on Aboveground Community Structure and AGB

Grassland management reshapes the community structure of savanna ecosystems by regulating disturbance intensity and resource availability, thereby driving difference in diversity indices, functional group composition, and evenness [31,32,33]. In our study, the PF_MM consistently promoted community diversity: Shannon diversity (H) was significantly higher under PF_MM than under PF or MM, while pairwise contrasts also showed higher D and E relative to PF and higher M relative to PF (Figure 4). Fire can rapidly remove accumulated litter and stimulate germination from the soil seed bank, whereas mowing maintains an open canopy and sustained light availability by repeatedly removing standing biomass [34,35]. The PF_MM likely creates spatiotemporally heterogeneous microsites that facilitate niche complementarity and the coexistence of species with contrasting life histories. Consistent with this view, experimental work has shown that reducing shrub vigor (e.g., by browsing or cutting) followed by prescribed fire can limit woody resprouting and open space for herbaceous recovery [36]. Furthermore, even decades of MM have failed to eliminate the dominant position of the shrub Helicteres isorain; this persistence is likely related to the resprouting growth characteristics of shrubs. Mowing maintains their ecological niche in the ecosystem and also helps maintain the stability of biodiversity under this treatment [37].

Functional group responses further support the reallocation of resources under combined disturbance. Relative to single treatments, PF_MM increased legume performance in multiple attributes (higher Fa.R overall; higher Fa.H than PF; higher Fa.IV than MM), indicating that resource optimization under PF_MM provided a niche advantage for Fabaceae (Figure 5b–d and Figure 9). By contrast, mowing alone suppressed grass height (lower Po.H than PF_MM), consistent with its direct removal of tall shoots [38]. Taken together, PF_MM appears to balance fire-induced germination cues with mowing-mediated control of overgrowth, establishing a “moderate disturbance—resource reallocation” state that favors diversity while limiting dominance by any single growth form [39,40].

With respect to productivity, MM produced the highest AGB, significantly exceeding PF and exceeding PF_MM without reaching significance (Figure 5a). This pattern is consistent with the high abundance of the dominant shrub Helicteres isora under MM, whose woody biomass can elevate total aboveground mass despite potential trade-offs for herbaceous layers. PF yielded the lowest AGB, with PF_MM intermediate, suggesting that fire may transiently suppress biomass of some species, whereas subsequent mowing in PF_MM may partially offset this effect by reducing competitive asymmetry and facilitating regrowth.

4.2. Effects of Grassland Treatments on Aboveground Plant Nutrient Composition

MM also conferred clear advantages for foliar nutrient concentrations and stocks. Moderate mowing can enhance nutrient concentrations in plant tissues by reducing interspecific competition and promoting litter decomposition and nutrient cycling. Yang et al. showed that mowing significantly increased plant N and P content [41]. Additionally, fire frequency can reduce N, P, and K in plants or in available pools [42], consistent with our observation of lower concentrations under PF relative to MM. That said, treatment effects on foliar chemistry are not universally consistent across systems; some studies report little sensitivity of foliar N, P, and K to management regime [43,44], highlighting the importance of community context. Here, functional-group composition emerged as a key regulator of foliar nutrients. Legume richness (Fa.R) was negatively correlated with community-level N, P, and K concentrations, implying that under certain conditions, high legume richness may not translate into higher foliar nutrient concentrations. In diverse stands, limited nutrients are partitioned among more species and individuals, potentially diluting concentrations per unit biomass [45,46,47]. Moreover, while N fixation can enlarge the soil N pool, it may also stimulate non-fixing competitors (e.g., Poaceae), intensifying demand for co-limiting P and K and reinforcing trade-offs [48]. From a management perspective at Datian National Nature Reserve, MM enhanced foliar N, P, and K concentrations, and increased nutrient stocks, aligning with goals of high-quality forage production. However, exclusive long-term reliance on mowing risks nutrient export exceeding replenishment, potentially depleting soil N and P pools. In contrast, although PF_MM was less effective at enhancing foliar nutrient concentrations, it promoted ecosystem stability and functional redundancy by maintaining higher species and functional group diversity, making it more suitable for conservation-priority management goals such as habitats for endangered species like the Eld’s deer.

MM supports foliar nutrient enrichment, which helps meet the species’ nutritional demands, particularly during critical life stages such as fawning and lactation. However, long-term repeated MM may lead to habitat homogenization and nutrient depletion, thereby undermining forage quality over time. By contrast, the PF_MM approach fosters heterogeneous vegetation structure, providing not only diverse forage but also cover necessary for fawn concealment. The long-term ecological outcomes of repeated PF/MM treatments, such as cumulative impacts on soil seed banks, nutrient cycling, and woody plant regeneration, warrant further study, as they are critical to designing rotational management strategies that sustain habitat quality and landscape-level heterogeneity for Rucervus eldii.

This study is subject to several limitations. The limited number of replicates (only six per treatment) may constrain the statistical power, potentially reducing the ability to detect subtle treatment effects. Furthermore, all data were derived from a single growing season (August), representing a single-year dataset. This restricts the capacity to account for interannual variability, particularly the influence of differing climatic conditions, on the outcomes of the management practices. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings needs to be corroborated by more extensive, long-term monitoring studies.

5. Conclusions

Long-term management at Datian National Nature Reserve revealed distinct trade-offs between biodiversity and forage quality. The PF_MM treatment maximized plant community diversity, with 38 species and a Shannon-Wiener index significantly higher than those in single treatments, indicating that combined disturbances better maintain community structural stability through niche complementarity. MM produced the highest AGB and foliar N, P, K concentrations, but maintained dominance of the shrub Helicteres isora, raising concerns about functional-group imbalance, and suppressed herbaceous development. Legume richness (Fa.R) was negatively associated with community-level P and K, suggesting intensified competition for limiting nutrients despite potential N inputs. SEM indicated that treatment effects on productivity were mediated primarily through Fa.IV, identifying Fa.IV as a key pathway by which disturbance regimes influence biomass. We therefore recommend adopting a spatially heterogeneous management strategy: applying the PF_MM treatment across large areas to sustain biodiversity and overall habitat structure for Eld’s deer, while implementing MM in smaller, designated zones to maintain high-quality forage patches. This approach balances conservation and production objectives while preserving ecosystem functioning.

Future studies should focus on multi-year monitoring to capture temporal variability in treatment outcomes, particularly under different climatic conditions. Research on soil nutrient feedbacks and seed bank dynamics following repeated PF/MM applications will also be critical to understanding the long-term ecological impacts of these management practices. These findings offer broader relevance for the management of tropical savannas beyond Datian, especially those facing similar pressures from shrub encroachment and foraging demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y. and Y.F.; methodology, Y.G., J.L., D.Y. and A.H.; software, J.L., Y.G., B.H. and M.F.; formal analysis, J.L., Y.F. and X.X.; investigation, M.F. and Y.F.; resources, D.Y. and X.Q.; data curation, J.L., B.H., Y.G. and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and X.Q.; writing—review and editing, J.L., D.Y. and A.H. supervision, D.Y.; funding acquisition, A.H. and D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Financial Forestry and Grassland Ecological Protection and Restoration Fund (National Nature Reserve Subsidy) Project (ZHZRHN-2025-024); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401635); the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund for Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Science (1630032025017).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author as our project is not yet finished, and the data cannot be disclosed.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Deepseek-V3.2 for the purposes of grammar and spell checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Standardized abbreviations for Latin names of vascular plant species recorded in the study.

Table A1.

Standardized abbreviations for Latin names of vascular plant species recorded in the study.

| No. | Latin Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chromolaena odorata | Ch.od |

| 2 | Waltheria indica | Wa.i |

| 3 | Phyllanthus urinaria | Ph.u |

| 4 | Spermacoce alata | Sp.a |

| 5 | Alysicarpus vaginalis | Al.v |

| 6 | Scoparia dulcis | Sc.d |

| 7 | Arivela viscosa | Ar.v |

| 8 | Ipomoea obscura | Ip.o |

| 9 | Cynodon radiatus | Cy.ra |

| 10 | Sida cordifolia | Si.c |

| 11 | Sida rhombifolia | Si.r |

| 12 | Panicum brevifolium | Pa.b |

| 13 | Tridax procumbens | Tr.p |

| 14 | Ocimum basilicum | Oc.b |

| 15 | Crotalaria pallida | Cr.p |

| 16 | Dactyloctenium aegyptium | Da.a |

| 17 | Indigofera hirsuta | In.h |

| 18 | Helicteres isora | He.i |

| 19 | Mimosa pudica | Mi.p |

| 20 | Lepisanthes rubiginosa | Le.r |

| 21 | Vitex agnus-castus | Vi.a |

| 22 | Commelina benghalensis | Co.b |

| 23 | Christia vespertilionis | Ch.v |

| 24 | Eragrostis pilosa | Er.p |

| 25 | Fimbristylis dichotoma | Fi.d |

| 26 | Passiflora foetida | Pa.f |

| 27 | Desmodium pulchellum | De.p |

| 28 | Indigofera tinctoria | In.t |

| 29 | Tephrosia purpurea | Te.p |

| 30 | Cyperus rotundus | Cy.ro |

| 31 | Zornia gibbosa | Zo.g |

| 32 | Lithospermum arvense | Li.a |

| 33 | Praxelis clematidea | Pr.c |

| 34 | Mesosphaerum suaveolens | Me.s |

| 35 | Evolvulus alsinoides | Ev.a |

| 36 | Spermacoce pusilla | Sp.p |

| 37 | Desmostachya bipinnata | De.b |

| 38 | Imperata cylindrica | Im.c |

| 39 | Panicum maximum | Pa.m |

| 40 | Christia obcordata | Ch.o |

| 41 | Codoriocalyx motorius | Co.m |

| 42 | Eustachys tenera | Eu.t |

| 43 | Cajanus scarabaeoides | Ca.s |

| 44 | Chamaecrista mimosoides | Ch.m |

| 45 | Gomphrena celosioides | Go.c |

| 46 | Desmodium heterocarpon | De.h |

| 47 | Euphorbia hirta | Eu.h |

| 48 | Malvastrum coromandelianum | Ma.c |

| 49 | Pleurolobus gangeticus | Pl.g |

| 50 | Stylosanthes scabra | St.s |

| 51 | Cyperus cyperoides | Cy.c |

| 52 | Portulaca oleracea | Po.o |

| 53 | Paspalum thunbergii | Pa.t |

| 54 | Brachiaria subquadripara | Br.s |

| 55 | Sida cordata | Si.d |

| 56 | Melinis repens | Me.r |

| 57 | Thunbergia grandiflora | Th.g |

References

- Williamson, G.J.; Tng, D.Y.; Bowman, D.M. Climate, fire, and anthropogenic disturbance determine the current global distribution of tropical forest and savanna. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 024032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, C.P.; Charles-Dominique, T.; Stevens, N.; Bond, W.J.; Midgley, G.; Lehmann, C.E. Human impacts in African savannas are mediated by plant functional traits. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.J.P.; Magnago, L.F.S.; Matos, F.A.R.; Mota, N.M.; Diniz, É.S.; Meira-Neto, J.A.A. Effects of anthropogenic disturbances on biodiversity and biomass stock of Cerrado, the Brazilian savanna. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 3151–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Yue, M. Deep mowing rather than fire restrains grassland Miscanthus growth via affecting soil nutrient loss and microbial community redistribution. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, F.F.; Scasta, J.D.; Overbeck, G.E. Interactive effects of fire and grazing on vegetation structure and plant species composition in subtropical grasslands. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2024, 27, 12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.H.; Mo, Y.; Chan, B.P.L. Past, present and future of the globally endangered Eld’s deer (Rucervus eldii) on Hainan Island, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, 01505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuchillo-Hilario, M.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Isselstein, J. Forage selectivity by cattle and sheep co-grazing swards differing in plant species diversity. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wam, H.K.; Hjeljord, O. Moose summer and winter diets along a large scale gradient of forage availability in southern Norway. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 745–755.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, B.J.; Buitenwerf, R.; Ruggiero, R.; Trepel, J.; Waltert, M.; Svenning, J.C. What moves large grazers? Habitat preferences and complementing niches of large herbivores in a Danish trophic rewilding area. Environ. Manag. 2025, 75, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortíz-Domínguez, G.A.; Marin-Tun, C.G.; Torres-Fajardo, R.A.; González-Pech, P.G.; Capetillo-Leal, C.M.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.d.J.; Ventura-Cordero, J.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A. Selection of Forage Resources by Juvenile Goats in a Cafeteria Trial: Effect of Browsing Experience, Nutrient and Secondary Compound Content. Animals 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; He, L.; Liu, B.; Li, L.; Wei, N.; Zhou, R.; Qi, L.; Liu, S.; Hu, D. Feeding performance and preferences of captive forest musk deer while on a cafeteria diet. Folia Zool. 2015, 64, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, D.; Tietjen, B.; Blaum, N.; Joubert, D.F.; Jeltsch, F. Prescribed fire as a tool for managing shrub encroachment in semi-arid savanna rangelands. J. Arid. Environ. 2014, 107, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Ribeiro, E. Fire and plant diversity at the global scale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, M.B.; Parra, A.; Laudicina, V.A.; Moreno, J.M. Post-fire soil functionality and microbial community structure in a Mediterranean shrubland subjected to experimental drought. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, J.L.; Girona–García, A.; Martí–Dalmau, C.; Ortiz–Perpiñá, J.O.; Armas–Herrera, C.M.; Badía–Villas, D. Changes in pools of organic matter and major elements in the soil following prescribed pastoral burning in the central Pyrenees. Geoderma 2021, 402, 115169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Rafique, R.; Ma, L.; Hu, L.; Luo, Y. Fire Alters Vegetation and Soil Microbial Community in Alpine Meadow. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wilson, G.W.; Cobb, A.B.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y. Phosphorus and mowing improve native alfalfa establishment, facilitating restoration of grassland productivity and diversity. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.J.; Lü, X.T.; Stevens, C.J.; Zhang, G.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Han, X.G. Mowing mitigates the negative impacts of N addition on plant species diversity. Oecologia 2019, 189, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shan, L.; Kong, X.; Li, D.; Kang, X.; Zhu, R.; Tian, C.; Chen, J. Effects of clipping frequency on the relationships between species diversity and productivity in temperate steppe. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2018, 20, 2325–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zheng, C.; Gao, Y.; Baskin, C.C.; Sun, H.; Yang, H. Moderate clipping stimulates over-compensatory growth of Leymus chinensis under saline-alkali stress through high allocation of biomass and nitrogen to shoots. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 92, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, C.J.; Coates, T.A.; Hagan, D.L.; Aust, W.M.; Waldrop, T.A.; Simon, D.M. Long-term effects of repeated prescribed fire and fire surrogate treatments on forest soil chemistry in the southern Appalachian Mountains (USA). Fire 2020, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.L.; Li, S.Y. Preliminary analysis of the relationship between population dynamics of captive Hainan Eld’s deer and their food resources. Acta Theriol. Sin. 1993, 3, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.L.; Wu, L.L.; Hou, R.; Lin, S.L. Investigation on alien plants in the habitat of Hainan Eld’s deer. Chin. J. Wildl. 2012, 33, 309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.F.; Teng, L.W.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, Z.G.; Pan, D.; Song, Y.L. Habitat and food selection of Hainan Eld’s deer. Chin. J. Zool. 2009, 44, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.L.; Wen, X.M.; Feng, Y.; He, B.B.; Zhang, E.B. Effects of burned grassland vegetation on the habitat of Hainan Eld’s deer in Datian Nature Reserve. J. Trop. For. 2023, 51, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Feng, Y.; Rao, X.D.; Ma, X.F.; Wang, J.J.; Tian, X.H. Simulated habitat modification at Hainan Eld’s deer exhibition area: A case study from Hainan Tropical Wildlife Park and Botanical Garden. Chin. J. Wildl. 2023, 44, 744–752, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Liang, X. Enhanced Primary Productivity in Fenced Desert Grasslands of China through Mowing and Vegetation Cover Interaction. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Ye, M.; Li, M.; Chen, W.; He, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, X.; Che, J.; Qian, J.; Lv, Y. The Influence of Three-Year Grazing on Plant CoMCunity Dynamics and Productivity in Habahe, China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkiewicz-Jasińska, A.; Stopa, W.; Barszczewski, J.; Gryszkiewicz-Zalega, D.; Wróbel, B. Nutrient Balances and Forage Productivity in Permanent Grasslands Under Different Fertilisation Regimes in Western Poland Conditions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Huang, D.; Duan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.; Huan, H. Cover legumes promote the growth of young rubber trees by increasing organic carbon and organic nitrogen content in the soil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 197, 116640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Brandt, M.; Penuelas, J.; Guichard, F.; Tong, X.; Tian, F.; Fensholt, R. Ecosystem structural changes controlled by altered rainfall climatology in tropical savannas. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandle, L.; Ticktin, T. Moderate land use changes plant functional composition without loss of functional diversity in India’s Western Ghats. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.M.; Batalha, M.A.; Cianciaruso, M.V. Influence of fire history and soil properties on plant species richness and functional diversity in a neotropical savanna. Acta Bot. Bras. 2013, 27, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Lamont, B.B. Fire-released seed dormancy-a global synthesis. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1612–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piseddu, F.; Bellocchi, G.; Picon-Cochard, C. Mowing and warming effects on grassland species richness and harvested biomass: Meta-analyses. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Taylor, J.H.; Nippert, J.B. Browsing and fire decreases dominance of a resprouting shrub in woody encroached grassland. Ecology 2020, 101, 02935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.K.; Ratajczak, Z.; Keen, R.M.; Nippert, J.B.; Grudzinski, B.; Veach, A.; Taylor, J.H.; Kuhl, A. Trajectories and state changes of a grassland stream and riparian zone after a decade of woody vegetation removal. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 33, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Nie, Y.; Xu, L.; Ye, L. Enclosure in combination with mowing simultaneously promoted grassland biodiversity and biomass productivity. Plants 2022, 11, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Jiao, F.; Li, Y.H.; Kallenbach, R.L. Anthropogenic disturbances are key to maintaining the biodiversity of grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moi, D.A.; García-Ríos, R.; Hong, Z.; Daquila, B.V.; Mormul, R.P. Intermediate disturbance hypothesis in ecology: A literature review. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2020, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Minggagud, H.; Baoyin, T.; Li, F.Y. Plant production decreases whereas nutrients concentration increases in response to the decrease of mowing stubble height. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 253, 109745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, A.; Gélin, U.; Subedi, N.; Regmi, S.; Tomlinson, K.W. Herbivory and fire influence soil and plant nutrient dynamics in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 60, 03610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Ji, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, F.Y. Divergent effects of grazing versus mowing on plant nutrients in typical steppe grasslands of Inner Mongolia. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16, rtac032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, R.G. The effects of grazing and burning on soil and plant nutrient concentrations in Colombian páramo grasslands. Plant Soil 1995, 173, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Lian, J.; Yang, H.; Li, Y. Plant community C:N:P stoichiometry is mediated by soil nutrients and plant functional groups during grassland desertification. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 162, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Ebeling, A.; Oelmann, Y.; Ptacnik, R.; Roscher, C.; Weigelt, A.; Weisser, W.W.; Wilcke, W.; Hillebrand, H. Biodiversity effects on plant stoichiometry. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, V.; Klaus, V.H.; Penone, C.; Schäfer, D.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Müller, J.; Socher, S.A.; Niinemets, Ü.; Peñuelas, J.; et al. Nutrient stoichiometry and land use rather than species richness determine plant functional diversity. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedníková, P.; Kukla, J.; Frouz, J. The Growth, Competition, and Facilitation of Grass and Legumes in Post-mining Soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 3695–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).