Abstract

Soil aggregates, which form the basic framework of soil structure, exert significant control over soil quality and crop yield. However, the influence of organic amendments on the relationships between aggregate formation and crop yield are still unclear. To investigate this issue, a long-term field experiment was established including four fertilizer treatments: control without fertilization (CK), chemical fertilizer (NPK), NPK combined with straw (NPKS), and NPK combined with organic manure (NPKM). Soil aggregates were fractionated into >2 mm (LMA), 2–0.25 mm (MMA), 0.25–0.053 mm (SMA), and <0.053 mm (MIC) fractions. NPKS and NPKM treatments increased the proportion of large macroaggregates (LMAs) by 8–12% and significantly elevated soil organic carbon (SOC) and nutrient levels relative to CK. NPKS and NPKM significantly increased the soil quality index (SQI) of LMA and MIC by 45.5–116.7% and 21.1–32.1%, compared with CK and NPK. Random forest (RF) analysis revealed that among the nutrient variables across the four aggregate fractions, the SOC content in LMA and the total phosphorus (TP) content in MIC contributed the highest to soybean yield. Partial least squares modeling further confirmed that the SQI of LMA was the dominant factor influencing soybean yield. Therefore, long-term organic amendments improve soybean yield mainly by enhancing soil quality at the aggregate scale, providing a practical pathway for sustaining soil quality and crop productivity.

1. Introduction

Soil aggregates are key determinants of soil quality and ecosystem performance in farmlands [1], serving as major pools of soil organic carbon and nutrients [2]. Aggregate composition strongly affects soil carbon and nitrogen contents, as the disintegration of aggregates releases protected organic matter and enhances its mineralization and loss [3]. The stability of soil organic matter is enhanced because its biological accessibility is significantly limited in the 0.25–0.053 mm aggregate fraction, which could be related to mineral-sorbed carbon and recalcitrant by-products of plant or microbial origin [4]. The >0.25 mm soil aggregate fraction contains more labile organic matter derived from fresh litter, fine roots, and fungal hyphae [5] and also provides physical protection for soil organic matter through occlusion within aggregates [6,7]. Because aggregate-mediated physical and biochemical processes jointly control soil functionality, understanding how management affects aggregate distribution and composition is essential for maintaining soil quality. Such improvements in soil physical structure are particularly important for soybean, whose yield formation strongly depends on root proliferation, nutrient uptake, and nodulation efficiency in well-aggregated soils.

Application of organic amendments can improve soil aggregate formation and increase soil organic carbon (SOC) and nutrients [8]. Improved aggregation not only enhances soil fertility but also creates a more favorable structural environment for soybean root growth and pod formation [9]. According to Tian et al. [10], long-term application of organic manure enhanced the concentrations of C, N, and P in large macroaggregates (>2 mm, LMAs) and simultaneously increased their relative abundance in soil. Similarly, Li et al. [11] observed that straw incorporation elevated SOC levels in LMA by 11–14%. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [12] found that combining organic manure with straw markedly promoted the formation of LMA by 24.5–59.1% and enriched phosphorus contents in both LMA and medium macroaggregates (2–0.25 mm, MMAs). Although numerous studies have investigated how organic manure or straw affect soil aggregation and nutrient distribution [13,14], the specific aggregate fractions that respond most strongly to organic amendments remain poorly understood. Clarifying these responses is critical, as different aggregate fractions provide contrasting physical environments that may differentially influence soybean yield. Moreover, previous studies mainly focused on topsoil or bulk soil, whereas the functional role of subsoil (20–40 cm) aggregates—which contribute significantly to deep rooting and nutrient capture—has received limited attention.

As a quantitative measure integrating physical, chemical, and biological attributes of soil, the soil quality index (SQI) provides an effective tool for assessing soil function [15]. Enhancements in the SQI are often achieved through the joint use of organic and inorganic fertilizers, which modify key properties such as aggregate structure and SOC content. Increases of 15.0–19.0% in the SQI within 0–40 cm soils were reported under organic fertilizer treatment [11], with SOC, TN, and TP acting as the main driving factors. Similarly, Huo et al. [16] documented a 22.2–40.7% improvement in the SQI following long-term straw return in the 0–20 cm layer. However, most previous studies have focused on bulk soil SQI, whereas the effects of organic amendments on the SQI at the aggregate scale remain largely unexplored. Consistent with previous syntheses, Song et al. [17] found that the use of organic amendments generally promoted crop yield and soil quality, resulting in mean increases of 14% and 6%, respectively. Likewise, Mi et al. [18] demonstrated that both organic manure and straw application improved the SQI and yield, with the SQI showing a strong positive correlation with sustainable productivity. These findings suggest that the SQI can serve as a bridge linking soil structural improvement with crop performance, but the contribution of the SQI at different aggregate scales to soybean yield is still unclear. For soybean, improvements in structural stability and aggregate-associated nutrient availability are key drivers of yield resilience and overall productivity.

In this study, the long-term field experiment was designed to assess the influence of organic amendments in combination with chemical fertilizers on soil aggregate distribution, nutrient status, aggregate-scale SQI, and soybean yield at depths of 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm. Random forest analysis was used to quantify the contributions of SOC and nutrient contents, as well as the SQI at each aggregate scale, to soybean yield, following the method of Liu et al. [19]. We hypothesized that (1) SOC and nutrient contents in LMA at 0–20 cm and in MIC at 20–40 cm contribute highest to soybean yield and (2) SQI at the LMA scale would have a greater overall impact on soybean yield.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

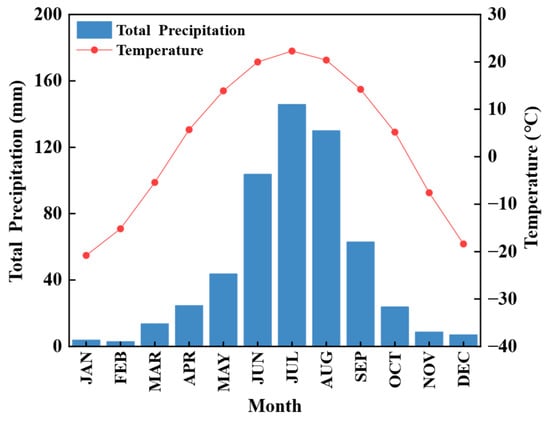

Located in Heilongjiang Province, China (47°27′ N, 126°55′ E), the study site is based at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Hailun Agroecosystem National Field Observation Station, founded in 1990. The experimental site is characterized by a temperate continental monsoon climate, with warm and humid summers and long, dry winters. The mean annual temperature is 1.5 °C, varying from −23 °C in January to 21 °C in July, and the annual precipitation averages 550 mm, about 65% of which occurs from June to August. The climatic conditions from January to December 2022 are shown in Figure 1. The soil was classified as a Mollisol according to the USDA Soil Taxonomy [20], is predominantly formed from sedimentary parent materials and possesses a loess-derived, loamy texture.

Figure 1.

Monthly total precipitation and mean air temperature in the experimental area from January to December 2022.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

The field experiment followed a randomized complete block design with four treatments and three replicates. Each plot (12 m × 5.6 m) received one of the following treatments: CK (no fertilizer), NPK (chemical fertilizer), NPKS (NPK + straw, 4.5 Mg ha−1 yr−1), and NPKM (NPK + organic manure, 3.75 Mg ha−1 yr−1). Fertilizer application rates were 30 kg N ha−1 (urea), 36 kg P ha−1 (ammonium hydrogen phosphate), and 30 kg K ha−1 (potassium sulfate). The field was managed under a maize–soybean rotation, with soybean grown in the sampling year. Fertilizers and amendments were applied before sowing, and soils were sampled at maturity. The pig manure (pH 7.3) contained 265 g C, 21 g N, 2.6 g P, and 2.4 g K per kg dry matter. The basic soil properties of the experimental soils are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The soil’s basic physical and chemical properties in 1990.

2.3. Soil Sampling, Aggregate Separation, and Analysis

In August 2022, composite soil samples were obtained by mixing subsamples collected from three randomly chosen points in each plot at two depths (0–20 cm and 20–40 cm). Aggregate fractionation was carried out using the wet-sieving method described by Six et al. [21] and Puget et al. [22]. Specifically, 100 g of air-dried soil was slowly moistened for 5 min with 15–20 mL of distilled water sprayed through a fine mist to achieve uniform wetting. The sample was subsequently soaked in approximately 500 mL of distilled water for another 5 min to complete the pre-wetting step. After hydration, the soil was transferred onto a nest of sieves (2.0, 0.25, and 0.053 mm) and shaken in water for 10 min at 32 rpm with a 3.8 cm oscillation. Aggregates were divided into four size fractions: LMA (>2 mm), MMA (2–0.25 mm), SMA (0.25–0.053 mm), and MIC (<0.053 mm). Subsamples from each aggregate size class were analyzed for soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), available nitrogen (AN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), total potassium (TK), available potassium (AK), and pH. Measurements of AN, AP, and AK followed the analytical protocols of Zhang et al. [23]. Soil pH was determined potentiometrically in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil-to-water mixture. SOC and TN were measured using a Vario EL CHN elemental analyzer (Elementar, Hanau, Germany).

2.4. Evaluating Soil Quality Index (SQI) and Soybean Yield

To evaluate overall soil quality, the SQI was computed by integrating multiple soil indicators through a weighted summation of their normalized scores and assigned weights:

Here, Wi is the assigned weight for the i-th soil parameter, Si is its standardized score, and n denotes the total number of soil indicators considered. Following Mei et al. [24], eight key variables describing soil physicochemical conditions were identified, and the MDS-based soil quality index (SQI) was developed using principal component analysis (PCA) in combination with a normalization procedure. The normalized score for each parameter was calculated using the following formula [24]:

Nik denotes the summed contribution of the i-th variable to the first k principal components (eigenvalues ≥ 1), μik is the loading of that variable on component k, and λk represents the proportion of variance described by component k. From this analysis, TK and AN were identified as the optimal indicators for constructing the final MDS-SQI. Soybean plants were harvested on 29 September 2022, and yields were assessed by hand-harvesting three 2 m2 subplots randomly selected within each treatment.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Random forest (RF) models identified the key aggregate-related nutrients influencing soybean yield. Partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) further clarified the direct and indirect effects of organic amendments on aggregate-scale SQI and yield, with path coefficients estimated using the “plspm” package in R [10]. Statistical analyses were conducted in R 4.3.2; data normality and variance homogeneity were tested with the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests (car v3.1-2); and treatment effects were evaluated by two-way ANOVA.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Aggregate Fraction and Soybean Yield

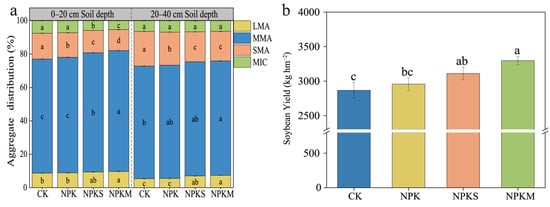

Across both the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers, the incorporation of organic manure or straw alongside chemical fertilizers markedly altered the distribution of soil aggregate fractions (Figure 2). In the 0–20 cm layer, the share of LMA under NPKM exceeded that of CK and NPK treatments by 11.6% and 9.8%, respectively (Figure 2a). Compared with CK, NPK, and NPKS, the fraction of MMA under the NPKM was significantly higher by 6.5%, 5.3%, and 1.2%, respectively. The combined use of organic manure or straw with chemical fertilizer markedly affected aggregate distribution. In the 0–20 cm layer, both NPKS and NPKM treatments reduced the SMA fraction relative to CK and NPK, with a 6.3% lower value under NPKM than under NPKS. MIC displayed a consistent pattern with SMA. In the 20–40 cm layer, the proportions of LMA and MMA were higher under NPKM by 4.6% and 0.3% compared with NPKS (Figure 2a). Overall, SMA declined by 9.7–14.1% under NPKS and by 10.9–15.3% under NPKM compared with CK and NPK. Soybean yield under NPKM increased significantly by 15.0% and 11.5% compared with CK and NPK and by 6.0% relative to NPKS (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Soil aggregate fractions (a) and soybean yield (b) under different fertilization regimes in 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers. CK, unfertilized control; NPK, chemical fertilizer; NPKS, NPK plus straw; NPKM, NPK plus organic manure. LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. Distinct lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05), and error bars show standard deviations (n = 3).

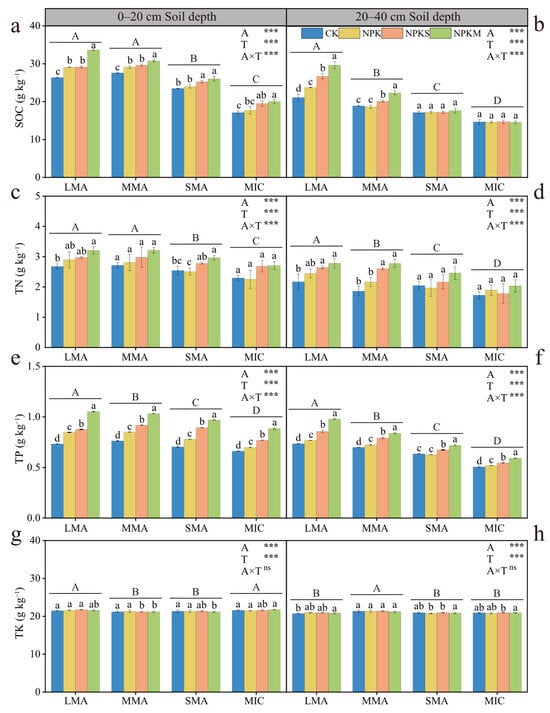

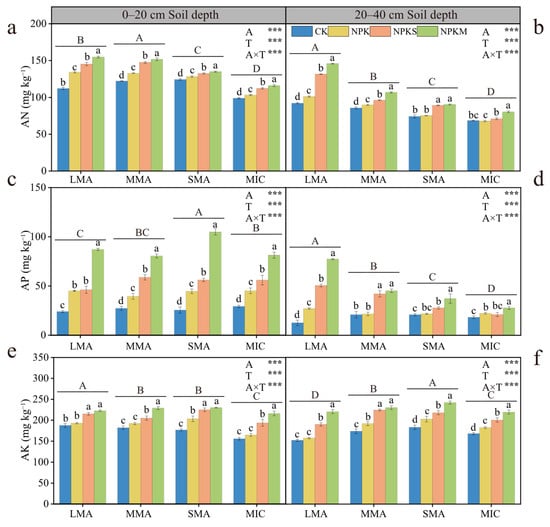

3.2. SOC, Nutrient Contents, and Soil Quality at the Aggregate Scale

The application of organic amendments markedly influenced SOC and nutrient distributions among aggregate fractions (Figure 3 and Figure 4). In the 0–20 cm layer, SOC levels within LMA and MMA were considerably greater than those in SMA and MIC (Figure 3a). Under the NPKM, the SOC contents in LMA and MMA were the highest, at 33.7 and 30.8 g kg−1, respectively. Similarly to SOC, TN content was highest in LMA under the NPKM treatment (3.2 g kg−1) (Figure 3c). The TP content was highest in LMA and, across all aggregate sizes, followed the order NPKM > NPKS > NPK > CK (Figure 3e). Under the NPKM, the AN content in MMA and the AP content in SMA were the highest, at 151.8 mg kg−1 and 105.0 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 4a,c). The AK content was highest in LMA, with NPKM and NPKS showing significantly higher content than NPK by 10.2% and 6.6%, respectively (Figure 4e).

Figure 3.

Soil nutrient contents in different aggregate size classes in 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers: (a) SOC in 0–20 cm; (b) SOC in 20–40 cm; (c) TN in 0–20 cm; (d) TN in 20–40 cm; (e) TP in 0–20 cm; (f) TP in 20–40 cm; (g) TK in 0–20 cm; (h) TK in 20–40 cm.; NPK, chemical fertilizer; NPKS, NPK plus straw; NPKM, NPK plus organic manure. LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium. A, aggregate size; T, treatment; A × T, interaction between aggregate size and treatment. Uppercase letters indicate differences among aggregate size fractions, and lowercase letters denote significant treatment effects (p < 0.05). Bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). ns, p > 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Soil nutrient contents in different aggregate size classes in 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers: (a) AN in 0–20 cm; (b) AN in 20–40 cm; (c) AP in 0–20 cm; (d) AP in 20–40 cm; (e) AK in 0–20 cm; (f) AK in 20–40 cm. CK, unfertilized control; NPK, chemical fertilizer; NPKS, NPK plus straw; NPKM, NPK plus organic manure. LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. AN, available nitrogen; AP, available phosphorus; AK, available potassium. A, aggregate size; T, treatment; A × T, interaction between aggregate size and treatment. Uppercase letters indicate differences among aggregate size fractions, and lowercase letters denote significant treatment effects (p < 0.05). Bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001.

In the 20–40 cm soil layer, the SOC content in the LMA fraction was significantly higher than other aggregate fractions. Under the NPKM, the SOC content in the LMA fraction was significantly higher than CK, NPK, and NPKS by 40.4%, 24.9%, and 11.0%, respectively (Figure 3b). The TN and TP contents showed similar trends across different aggregate fractions (Figure 3d,f). The MMA fraction contained significantly greater TK levels compared with LMA, SMA, and MIC (Figure 3h). Conversely, AN and AP concentrations were significantly elevated in LMA relative to the other aggregate fractions (Figure 4b,d). Compared with CK, the AN content under NPK, NPKS, and NPKM was significantly higher by 9.8%, 42.9%, and 58.3%, respectively. Similarly, under the NPKM, the AP content was highest at 77.3 mg kg−1.

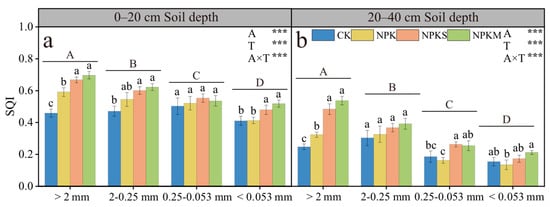

In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the SQI in large aggregates (LMA-SQI) was significantly higher than that in MMA, SMA, and MIC (Figure 5a). Under NPKM, the LMA-SQI was elevated by 52.2% and 18.6% relative to CK and NPK and by 4.5% relative to NPKS. A comparable trend in SQI was also observed in the 20–40 cm soil layer (Figure 5b). The LMA-SQI at 0–20 cm was 29.6% higher than that at 20–40 cm under NPKM treatment.

Figure 5.

SQI in aggregate scale in 0–20 cm (a) and 20–40 cm (b) soil layers. CK, unfertilized control; NPK, chemical fertilizer; NPKS, NPK plus straw; NPKM, NPK plus organic manure. LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. SQI, soil quality index; A, aggregate size; T, treatment; A × T, interaction between aggregate size and treatment. Uppercase letters indicate differences among aggregate size fractions, and lowercase letters denote significant treatment effects (p < 0.05). Bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001.

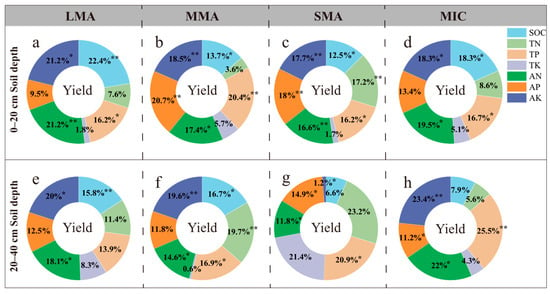

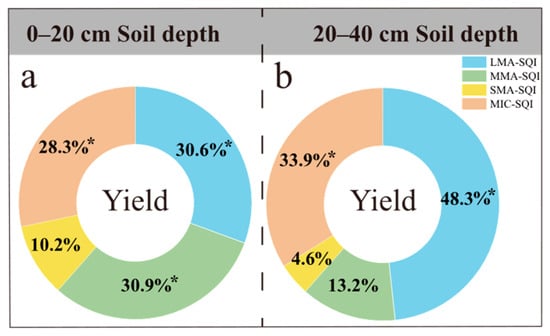

3.3. Contribution of SOC and Soil Nutrient Contents and SQI in Aggregate Scale to Soybean Yield

In the LMA fraction, soybean yield was primarily influenced by SOC in the 0–20 cm layer (22.4%) and by AK in the 20–40 cm layer (20.0%) (Figure 6a,e). For the MMA fraction, AP in the 0–20 cm soil exerted the strongest influence on soybean yield (20.7%), while TN in the 20–40 cm was the major contributing factor (19.7%) (Figure 6b,f). At the SMA fraction, the key factors showing the highest contribution to soybean yield in both the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers were consistent with those at the MMA fraction (Figure 6c,g). Within the MIC fraction, AN in the 0–20 cm layer contributed most to soybean yield (19.5%), whereas TP in the 20–40 cm layer made the greatest contribution (25.5%) (Figure 6d,h). In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the SQI at the MMA fraction showed the highest contribution to soybean yield (30.9%) (Figure 7a). In the 20–40 cm layer, the SQI at the LMA fraction had the greatest contribution, reaching 48.3% (Figure 7b).

Figure 6.

Contribution analysis of SOC and aggregate nutrients to soybean yield at the aggregate scale: (a–d) LMA, MMA, SMA and MIC in 0–20 cm; (e–h) LMA, MMA, SMA and MIC in 20–40 cm LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium; AN, available nitrogen; AP, available phosphorus; AK, available potassium. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Contribution analysis of aggregate-scale SQI to soybean yield: (a) 0–20 cm; (b) 20–40 cm. LMA, >2 mm; MMA, 2–0.25 mm; SMA, 0.25–0.053 mm; MIC, <0.053 mm. *, p < 0.05.

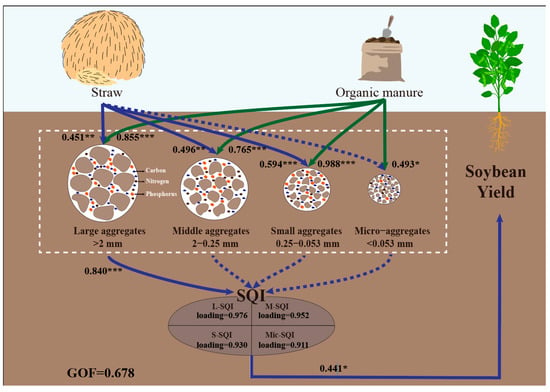

3.4. Relationship Between Soybean Yield and Aggregates

According to PLS-PM analysis, organic amendments combined with chemical fertilizers exerted significant direct and indirect effects on aggregate-associated soil attributes, the SQI, and soybean yield. (Figure 8). The effect of organic manure on the four aggregate fractions was greater than straw. At the LMA level, soil characteristics displayed a strong positive association with aggregate-scale SQI (path = 0.84). In turn, the SQI positively affected soybean yield (path = 0.441). Among the four aggregate fractions, the LMA-SQI showed the highest loading value (0.976) in representing aggregate-scale SQI. The goodness-of-fit (GOF) index of 0.678 indicated that the PLS-PM model achieved a reasonable level of overall fit.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the partial least squares path model (PLS-PM). Each box represents an observed (measured) or latent (constructed) variable. Green and blue arrows indicate positive effects. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The goodness-of-fit (GOF) model is 0.678.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Organic Amendments on Soil Aggregate Fraction and Properties

Soil aggregate composition in the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers was substantially modified by the long-term co-application of organic amendments and mineral fertilizers, leading to higher proportions of LMA and MMA and lower proportions of SMA and MIC (Figure 2). The aggregation process begins with microaggregates that subsequently coalesce to generate large macroaggregates [25]. In the 0–20 cm layer, organic manure inputs not only provided additional carbon sources but also enhanced microbial activity and fungal hyphal growth, strengthening particle binding and promoting the aggregation of MIC into LMA [26]. Similarly, polysaccharides and lignin derived from straw acted as natural binding agents, facilitating the conversion of SMA and MIC into LMA [27]. A meta-analysis further indicated that, compared with straw-derived cellulose and lignin that require microbial decomposition before acting as binding agents, organic manure directly promotes the formation of LMA through chemical cementing substances such as humic acids [28]. Compared with the CK, both NPKM and NPKS significantly increased SOC content across all aggregate fractions, with the largest increase observed under NPKM (Figure 3a). The improvement is largely driven by the more labile nature of manure-derived organic matter, which decomposes readily and releases nutrients faster than straw residues [29]. In addition, the physical protection afforded by soil aggregates effectively restricts microbial decomposition of organic matter [30], favoring the long-term stabilization of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. This mechanism also explains the higher proportion of LMA under NPKM compared with NPKS (Figure 2). Nutrient concentrations were consistently greater in LMA than in SMA (Figure 3 and Figure 4), reflecting the larger aggregate volume and lower specific surface area of LMA, which improve the physical protection and retention of organic matter and nutrients [31]. Organic amendments not only directly increase soil organic carbon and nutrient contents but also promote the formation of LMAs that serve as enrichment reservoirs for C, N, and P [13]. SOC, TN, and TP concentrations were significantly enriched in LMA and MMA compared with SMA and MIC, consistent with earlier studies (Figure 3 and Figure 4). In contrast, the highest AN and AP contents occurred in MMA and SMA (Figure 4a,c), likely because microbial immobilization of available N and P during the early stages of organic matter decomposition within LMA enhances total N and P accumulation while temporarily reducing available nutrient pools [32,33]. Similar observations were also reported by [23]. Taken together, these results indicate that the increases in LMA and nutrient-enriched MMA represent major structural pathways through which organic amendments improve soil physical and chemical functioning, suggesting that their effects extend beyond direct nutrient supply. The contrasting nutrient distributions among aggregate fractions also highlight the importance of aggregate-level analysis for understanding nutrient cycling processes relevant to soybean production. Furthermore, identifying how manure and straw affect specific aggregate fractions at different depths provides practical evidence for improving soil structure and nutrient conservation under long-term fertilization systems.

4.2. Impacts of Organic Amendments on Aggregate Scale SQI

Significant increases in the SQI were observed for all aggregate fractions under the combined use of organic amendments and fertilizers (Figure 5). Similar trends were reported by Zhang et al. [23], who attributed the improvement of soil function to enhanced nutrient conservation and structural integrity. The SQI in LMA at 0–20 cm was markedly greater than in the other aggregate fractions (MMA, SMA, and MIC). This increase was mainly associated with the higher SOC and nutrient levels and with better aeration and microbial conditions within LMA [34,35]. These factors create microenvironments with high enzyme activity, where the synergistic effects of physical stability, biological activity, and chemical buffering make LMA a key determinant of topsoil quality [36,37]. According to PLS-PM analysis, LMA exhibited a strong positive effect on the SQI (Figure 8), implying that better aggregate organization and nutrient enrichment directly promote soil quality. Therefore, the formation of LMA plays a crucial role in sustaining soil quality when organic amendments are combined with chemical fertilizers.

Compared with the 0–20 cm layer, the 20–40 cm soil exhibited lower SQI values (Figure 5b), reflecting the scarcity of direct organic matter additions at depth. Although the downward movement of dissolved organic carbon and nutrients may promote aggregate formation to some extent, this passive process is less efficient than direct amendment incorporation [38]. In the 20–40 cm layer, SQI improvement depends more on physicochemical stabilization processes such as organo-mineral associations and microbial residue accumulation [39]. Reduced biological activity and slower carbon turnover weaken the coupling between nutrient availability and microbial functional diversity, ultimately resulting in a lower SQI.

4.3. Impacts of Aggregate Nutrients and Aggregate Scale SQI on Soybean Yield

SOC in the LMA fraction of the 0–20 cm soil layer exerted the strongest influence on soybean yield (Figure 6a). This finding agrees with previous studies showing that carbon protected within LMA enhances root growth and nutrient uptake by improving soil pore structure and biological activity [1,40]. LMAs serve as reservoirs of plant-available nutrients that are gradually released through microbial turnover, sustaining nutrient supply for crop growth and development [41]. Interestingly, AP in MMA and SMA, as well as AN in MIC, also showed substantial contributions to soybean yield (Figure 6). In MMA and SMA, moderate pore connectivity and high specific surface area favor P desorption and diffusion, thereby facilitating the mobilization of microbially released P and ensuring a steady AP supply when crop demand is high [42]. Similarly, the high contribution of AN in MIC likely results from its capacity to support the continuous transformation of organic nitrogen into plant-available forms, providing a stable nitrogen source for root uptake and promoting yield [43].

At 20–40 cm depth, soybean yield was primarily affected by AK in LMA, TN in MMA and SMA, and TP in MIC, each representing the dominant factor within its nutrient pool (Figure 6d,e). This indicates that LMA enhances potassium retention and sustained release, supporting root metabolic activity in the 20–40 cm soil layer [44]. The moderate porosity of MMA and SMA facilitates nitrogen transport and microbial mineralization under limited carbon input, making them important reservoirs of available nitrogen [45]. The accumulation of TP within MIC may be related to mineral-bound P and microbial residues that gradually release potential nutrients through desorption or mineral dissolution [12,23]. The LMA-SQI exhibited the strongest contribution to soybean yield in both the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers (Figure 7). This consistent pattern suggests that LMA plays a pivotal role in maintaining the integrated functionality of soil systems across depths [46]. In addition, LMA often retains a legacy of long-term organic inputs and microbial residues, allowing the persistence of favorable physical and biochemical properties in deeper soil layers. Together, these mechanisms suggest that nutrients associated with specific aggregate fractions in deeper soils provide sustained support for crop productivity. Future studies should further quantify how nutrient transformations within specific aggregate fractions regulate crop productivity under varying managements. In addition, integrating microbial functional gene analyses with aggregate-scale nutrient dynamics could help clarify the biological pathways linking soil structure to yield formation.

5. Conclusions

The long-term field study showed that adding straw or organic manure in combination with chemical fertilizers improved the aggregate-scale SQI and enhanced soybean yield. Among the two organic amendments, the manure–fertilizer combination yielded the greatest nutrient enrichment and promoted the development of LMA enriched in SOC and AN. SOC in surface LMA (0–20 cm) and TP in subsoil MIC (20–40 cm) were the dominant factors governing soybean yield, while the LMA-SQI exerted the strongest overall influence. Overall, our results highlight that improved soil structural quality—especially stable, nutrient-rich macroaggregates—plays a key role in supporting soybean yield by enhancing root growth and nutrient uptake. Practically, long-term application of organic amendments together with balanced fertilization is recommended to maintain aggregate stability and sustain soybean productivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. (Zhiqi Wang), M.S., Y.W., and Z.W. (Zhimin Wu); Data curation, Z.W. (Zhiqi Wang), M.S., Y.W., Z.W. (Zhimin Wu), and X.L. (Xinchun Lu); Funding acquisition, W.Z., and Y.Z.; Investigation, Z.W. (Zhimin Wu), X.L. (Xinchun Lu), Y.Z., and L.Y.; Methodology, M.S., Y.W., and H.F.; Software, M.S., Y.W., X.L. (Xin Liu), H.F., and L.Y.; Supervision, X.L. (Xin Liu), H.F., Y.Z., L.Y., and W.Z.; Validation, X.L. (Xin Liu) and X.L. (Xinchun Lu); Visualization, Z.W. (Zhiqi Wang), X.L. (Xin Liu), and W.Z.; Writing—original draft, Z.W. (Zhiqi Wang); Writing—review and editing, X.L. (Xin Liu), H.F., Z.W. (Zhimin Wu), X.L. (Xinchun Lu), L.Y., and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R & D Program of China (2024YFD1500904), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20632), Outstanding Youth Fund of Heilongjiang Province (JQ2024D002), and China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS04).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented during this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, W.; Tang, S.; Dengzeng, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Ma, X. Root exudates contribute to belowground ecosystem hotspots: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 937940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Liang, G.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. A global meta-analysis of the impacts of no-tillage on soil aggregation and aggregate-associated organic carbon. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 5292–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cates, A.M.; Ruark, M.D. Soil aggregate and particulate C and N under corn rotations: Responses to management and correlations with yield. Plant Soil 2017, 415, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützow, M.V.; Knabner, I.K.; Ekschmitt, K.; Matzner, E.; Guggenberger, G.; Marschner, B.; Flessa, H. Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: Mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions—A review. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2006, 57, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunmala, P.; Jindaluang, W.; Darunsontaya, T. Distribution of Organic Carbon Fractions in Soil Aggregates and Their Contribution to Soil Aggregate Formation of Paddy Soils. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plan. 2023, 54, 1350–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil Structure and Soil Organic Matter II. A Normalized Stability Index and the Effect of Mineralogy. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Feng, G.; Huang, Y.; Tewolde, H.; Shankle, M.W.; Jenkins, J.N. Cover crops and poultry litter impact on soil structural stability in dryland soybean production in southeastern United States. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2024, 88, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, Q.; Egamberdieva, D.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. A Case Study in Desertified Area: Soybean Growth Responses to Soil Structure and Biochar Addition Integrating Ridge Regression Models. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhu, B.; Yin, R.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Kardol, P.; Liu, M.; et al. Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2022, 165, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Abalos, D.; Arthur, E.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Chen, J. Different straw return methods have divergent effects on winter wheat yield, yield stability, and soil structural properties. Soil. Tillage Res. 2024, 238, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Yuan, J.; Xu, C.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ai, Y.; et al. Combined Application of Chemical Fertilizer and Organic Amendment Improved Soil Quality in a Wheat–Sweet Potato Rotation System. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xia, X.; Ding, Y.; Feng, X.; Lin, Q.; Li, T.; Bian, R.; Li, L.; Cheng, K.; Zheng, J. Changes in aggregate-associated carbon pools and chemical composition of topsoil organic matter following crop residue amendment in forms of straw, manure and biochar in a paddy soil. Geoderma 2024, 448, 116967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Yan, L.; Cai, H. Response of soil organic carbon to straw return in farmland soil in China: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G.W.; Valente, D.S.M.; Queiroz, D.M.D.; Coelho, A.L.D.F.; Costa, M.M.; Grift, T. Smart-Map: An Open-Source QGIS Plugin for Digital Mapping Using Machine Learning Techniques and Ordinary Kriging. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, T.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Long-term straw return enhanced crop yield by improving ecosystem multifunctionality and soil quality under triple rotation system: An evidence from a 15 years study. Field Crop Res. 2024, 312, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; He, X.; Fu, J.; Zheng, F.; Li, Z. Responses of crop yield and soil quality to organic material application in the black soil region of Northeast China. Soil. Tillage Res. 2025, 253, 106690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Sun, T.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.; Ma, Q.; Wu, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Q. Higher yield sustainability and soil quality by manure amendment than straw returning under a single-rice cropping system. Field Crop Res. 2023, 292, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Si, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, W. Drivers of soil quality and maize yield under long-term tillage and straw incorporation in Mollisols. Soil. Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 11th ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Aggregate and soil organic matter dynamics under conventional and no-tillage systems. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puget, P.; Chenu, C.; Balesdent, J. Dynamics of soil organic matter associated with particle-size fractions of water-stable aggregates. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2000, 51, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G.; Gao, H.; Peng, C.; Zhu, P. Phosphorus Distribution within Aggregates in Long-Term Fertilized Black Soil: Regulatory Mechanisms of Soil Organic Matter and pH as Key Impact Factors. Agronomy 2024, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, N.; Gu, Y.; Li, D.Z.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, J.C.; Liu, J.Z.; Ren, J.; Cai, H.G. Soil quality evaluation in topsoil layer of black soil in Jilin Province based on minimum data set. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, R.N.; Bach, E.M.; Hofmockel, K.S. Spatio-temporal microbial community dynamics within soil aggregates. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2019, 132, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Yuan, S.; Gao, W.; Tang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S. Aggregate-related changes in living microbial biomass and microbial necromass associated with different fertilization patterns of greenhouse vegetable soils. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 2021, 103, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ren, T.; Lei, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J. Tillage and straw-returning practices effect on soil dissolved organic matter, aggregate fraction and bacteria community under rice-rice-rapeseed rotation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 287, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Cao, Y.; Lu, J.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, X. Response of soil aggregation and associated organic carbon to organic amendment and its controls: A global meta-analysis. Catena 2024, 237, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, Z.; Hu, J.; Yaa, O.; Wu, J. Decomposition characteristics, nutrient release, and structural changes of maize straw in dryland farming under combined application of animal manure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Guzman, J.; Kovacs, P.; Kumar, S. Manure and inorganic fertilization impacts on soil nutrients, aggregate stability, and organic carbon and nitrogen in different aggregate fractions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2022, 68, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Gao, W.; Luan, H.; Tang, J.; Li, R.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S. Long-term manure and/or straw substitution mediates phosphorus species and the phosphorus-solubilizing microorganism community in soil aggregation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 378, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Shutes, B.; Hou, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. Long-term organic fertilization increases phosphorus content but reduces its release in soil aggregates. Appl. Soil Ecol. A Sect. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 203, 105684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Feng, X.; Liu, C.; Han, Y.; Long, G.; Chen, S.; Lin, Q.; Gong, J.; Shen, Y.; Mao, Z.; et al. Soil organic carbon storage, microbial abundance and pore structure characteristics of macroaggregates across a soil-landscape sequence in a subtropical hilly watershed. Catena 2024, 242, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, W.; Nottingham, A.T.; Xiao, D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, J.; Duan, P.; Tang, T.; et al. Lithological Controls on Soil Aggregates and Minerals Regulate Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency and Necromass Stability. Env. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21186–21199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Shu, H.; Hu, W.; Han, H.; Liu, R.; Guo, Z. Straw return increases crop production by improving soil organic carbon sequestration and soil aggregation in a long-term wheat–cotton cropping system. J. Integr. Agr. 2024, 23, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. Soil aggregation is more important than mulching and nitrogen application in regulating soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in a semiarid calcareous soil. Env. Sci. Technol. 2023, 854, 158790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; He, Y.; Shang, H.; Hu, C.; Duan, C.; Fu, D. Changes in plant carbon inputs alter soil phosphorus dynamics in a coniferous forest ecosystem in subtropical mountain area. Catena 2024, 247, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Han, X.; Biswas, A.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Yan, J.; Zou, W. Long-term organic material application enhances black soil productivity by improving aggregate stability and dissolved organic matter dynamics. Field Crop Res. 2025, 328, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, K.M.; Creamer, C.; Whitaker, J. Deconstructing the microbial necromass continuum to inform soil carbon sequestration. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 1396–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Kang, F.; Han, H. Dynamic characteristics of soil aggregate stability and related carbon and nitrogen pools at different developmental stages of plantations in northern China. J. Env. Manag. 2022, 316, 115283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Lin, J.; Chen, Z. Intensive input of labile carbon and mineral nitrogen enhancing the sequestration organic carbon across soil aggregates. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ai, S.; Xiao, J.; Sheng, M.; Ai, X.; Ai, Y. Characteristics and mechanisms of phosphorus adsorption-desorption in soil aggregates during cut slope restoration. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Adl, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B. Soil micro-food webs at aggregate scale are associated with soil nitrogen supply and crop yield. Geoderma 2024, 442, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Gao, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Straw return combined with potassium fertilization improves potassium stocks in large-macroaggregates by increasing complex iron oxide under rice–oilseed rape rotation system. Soil. Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chang, T.; Liu, X. Effects of Applying Organic Amendments on Soil Aggregate Structure and Tomato Yield in Facility Agriculture. Plants 2024, 13, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ding, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Gao, L.; Peng, X. Quantifying and visualizing soil macroaggregate pore structure and particulate organic matter in a Vertisol under various straw return practices using X-ray computed tomography. Geoderma 2024, 452, 117105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).