Abstract

Climate change or even the natural occurrence of periods of low suitability for the production of forage species are obstacles to maintaining adequate animal nutrition. Indoor green fodder production is an alternative to this problem; however, advances in technologies capable of improving this system still need to be studied in depth. The objective of this study was to evaluate the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of hydroponic green fodder production of millet and sorghum under varying monochromatic light supplementation and nicotinamide application. Eight treatments were defined by lighting (LS—Led Full Spectrum; LS + Ultraviolet LED; LS + Red LED; LS + Blue LED), and combined with the application of nicotinamide (with and without) at a concentration of 200 mg L−1. Cultivation under conditions of light supplementation with UV radiation or monochromatic lights results in increased light intensity by modifying the wavelength spectrum received by the plant, modification of the quality of photons received in relation to the energy level that leads to luminous stress and, consequently, lower green fodder development concerning height and fresh mass. Nicotinamide acts as a bioprotectant, attenuating the stressful effects and enabling greater productive efficiency in the production of hydroponic green fodder, particularly in vertical cultivation, which provides increased height and fresh mass for millet and sorghum green fodder. In contrast, the stress resulting from light supplementation can be used as a tool to increase carotenoid levels in plants and may be indicated for production systems that have this objective for biofortification of forages with bioactives with antioxidant effects.

1. Introduction

Hydroponic green fodder have gained traction in the food market for animal production, particularly in temperate countries where animals are housed indoors for extended periods [1,2]. However, these foods have also proven beneficial in tropical conditions, as large portions of territories in this climate experience periods of unfavorable weather for maintaining pastures, creating a need for supplementary feeding.

The most commonly used species for hydroponic green fodder production are those adapted to mild temperatures, such as alfalfa, wheat, oats, and barley, due to the conditions present in countries where this production technique is widespread, as well as corn, which is an alternative for higher temperatures [3]. Regarding field cultivation, hydroponic production is observed to allow greater efficiency of physical space and resources, including fertilizers, while also reducing water consumption by up to 97% [4]. Furthermore, the technification of production environments has been a focal point of interest, aiming to enhance sustainability in food production [5].

The use of systems with partial or total control for the production of hydroponic green fodder also enables the implementation of techniques that enhance plant performance and quality, such as biofortification through light supplementation [6]. Light energy can be reflected, transmitted, or absorbed by plants, primarily in the spectrum of photosynthetically active radiation, which ranges from 400 to 700 nm. Light supplementation in red and orange (610–720 nm), blue and purple (400–510 nm), and yellow and green (510–610 nm) wavelengths can alter plant physiology and morphology [7,8].

In this context, applying different wavelengths can lead to changes in the composition of beneficial elements or bioactive compounds, such as carotenoids [9]. However, excessive light supplementation can induce stress responses and result in photoinhibition, consequently decreasing physiological and productive activities [10]. To reverse potential damage to the physiological system and its components, nicotinamide can be used—a vitamin with biostimulant and bioprotective properties that has been successfully applied to various species grown under stressful conditions, whether in controlled environments or the field [11,12]. When applied as a foliar spray, this vitamin helps maintain the physiological activities of plants by stimulating the production of the enzymes NADH and NAPH, which are involved in numerous oxidative-reductive biological reactions, thus enabling the maintenance of energy transfer in cells [13].

This study investigated the hypothesis that applying vitamins can positively influence the performance of hydroponic green fodder production based on millet and sorghum under conditions of light supplementation. The objective was to evaluate the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of hydroponic green fodder production of millet and sorghum under varying monochromatic light supplementation and nicotinamide application.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Characterization

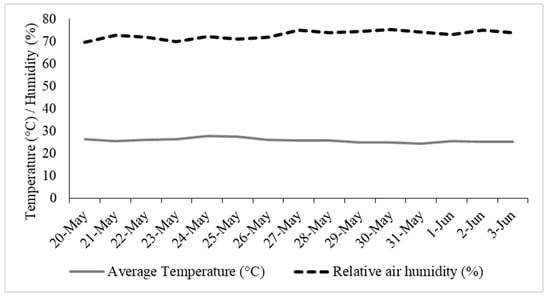

The experiment was conducted in a growth room at the Microalgae and Biotechnology Laboratory, located at the State University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UEMS) in Cassilândia, MS, Brazil (19°05′46″ S and 51°48′50″ W, with an altitude of 521 m). During the experiment, temperature and relative humidity conditions were recorded using a datalogger. The average temperature throughout the experimental period was 27 °C, and the relative humidity was approximately 72% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average temperature and relative humidity conditions during the experiment.

2.2. Experimental Design

Two trials were conducted simultaneously: one with millet and the other with sorghum. For both, a completely randomized design was employed, consisting of eight treatments defined by lighting (LED) with different wavelength spectrum. The cultivation environment featured standard lighting with LS—Led Full Spectrum LED Grow Light, red LEDs 620–630 nm, blue 440–445 nm, white LEDs 5500–6500 k and 2500–3300 k, infrared 730 nm, ultraviolet 380–410 nm, and photosynthetically active radiation of 67 μmol m−2 s−1. In each treatment, additional light (LED) was added in conjunction with standard lighting (LS), as described below: (L1—LS + Led Full Spectrum LED Grow Light, 50 W power, red LEDs 620–630 nm, blue 440–445 nm, white LEDs 5500–6500 k and 2500–3300 k, infrared 730 nm, ultraviolet 380–410 nm, and photosynthetically active radiation of 156 μmol m−2 s−1; L2—LS + Ultraviolet LED, spectral wavelength: 395–400 nm, 50 W power, and photosynthetically active radiation of 73 μmol m−2 s−1; L3—LS + Red LED—spectral wavelength: 620–660 nm, 50 W power, photosynthetically active radiation of 124 μmol m−2 s−1; L4—LS + Blue LED—spectral wavelength: 440–480 nm, power of 50 W, photosynthetically active radiation of 137 μmol m−2 s−1), combined with the application of nicotinamide (with and without) at a concentration of 200 mg L−1 [13]. In total, three replicates per treatment were utilized, with each replicate consisting of a black plastic tray measuring 17 × 12 cm and 2 cm in height.

2.3. Plant Material and Management

The plant material used was millet seed (Panissetum glaucum), cultivar BRS 1501, with a minimum of 80% germination and 95% purity, and sorghum seed “BRS Ponta Negra”, which has a minimum of 75% germination and 98% purity. The seeds were cleaned by washing them in running water three times to remove impurities. Subsequently, they were disinfected with a 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution, keeping the seeds submerged for 5 min before rinsing them to eliminate excess chlorine. Finally, they were soaked for 6 h in deionized water. Sowing was carried out in plastic trays, in which the seeds were arranged to form a uniform layer, using 80 g of seeds for both millet and sorghum, each with a moisture content of 40%.

Irrigation was performed with fresh water daily, paying attention to the moisture content of the roots. After the fourth day, irrigation was supplemented with a nutrient solution (18% N, 8% P, 30% K, 15% Ca, 3% S, 3% Mg, 0.14% Fe, 0.04% B, 0.04% Mn, 0.03% Cu, 0.019% Mo, 0.006% Ni, and 0.002% Co) at an EC of 1.2 dS m−1, applied via foliar application every two days, in a volume of 10 mL per tray.

During the first three days, the trays were kept in a dark environment to stimulate the germination process and the initial development of the plants’ aerial parts. Afterward, the plants were exposed to light (14 h of light and 10 h of darkness), and supplementation, according to the treatments, was performed in the last four hours of the light period. Following the light exposure, nicotinamide was applied daily as a foliar spray, using a volume of 10 mL per tray.

2.4. Evaluations Performed

2.4.1. Absolute Spectrum

The intensity distribution of light radiation at different wavelengths (nm) was verified, measured in W/m2/nm of the standard lighting (LS) of the cultivation environment. In each treatment, the intensity of light radiation at different wavelengths (nm) of supplementary lighting (LED) was verified in conjunction with standard lighting (LS), using a spectroradiometer (Y21B7W10034CCPD, Torch Bearer, Hangzhou, China) with a range of 240 to 1000 nm.

2.4.2. Growth and Production Assessment

Fifteen days after sowing, the height of the aerial parts of the plants was measured using a ruler graduated in millimeters, taking the corresponding value between the base and the apex of the aerial part at three points per tray. Then, the plant material was divided into two portions: the aerial part and the set of roots and seeds. These portions were weighed separately on a semi-analytical balance to determine the fresh mass, after which they were packed in paper bags and placed to dry in a forced ventilation oven at 65 °C for a period of 72 h. They were weighed again to obtain the dry mass.

2.4.3. Leaf Pigments

The chlorophyll, carotenoid, and pheophytin contents in leaves were determined. The extractions of chlorophyll (a and b), carotenoids, and pheophytin (a and b) were performed following the methodology of [14]. A total of 0.5 g of fresh plant material was weighed, 5 mL of 80% acetone was added, and the mixture was stored in 14 mL test tubes for 48 h in a refrigerator at 25 degrees. After this period, the test tubes were centrifuged for 15 min at 4000 rpm, and then the extract supernatant was diluted in a ratio of 0.3 mL of extract to 1.7 mL of 80% acetone. Measurements were performed in a spectrophotometer (IL-226-NM, Kasuaki, Tokyo, Japan) at wavelengths of 470 nm, 647 nm, 653 nm, 663 nm, and 665 nm.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using analysis of variance, and the means were compared with the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

3. Results

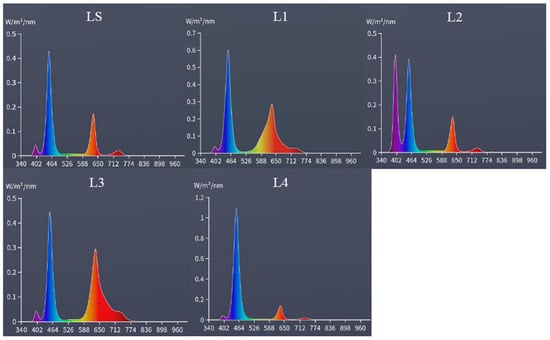

It was found that the standard lighting (LS) used in all cultivation environments presented peaks of light radiation intensity at wavelengths of 460 (blue) and 630 nm (red), with secondary peaks at 400 nm (ultraviolet) and 730 nm (infrared), characteristic of LED lighting for plant cultivation. L1, presents an intensity increase in the standard lighting (LS), that together with LED Grow Light (full spectrum) presented peaks of light radiation intensity at wavelengths of 460 (blue) and 630 nm (red), presenting secondary peaks at 400 nm (ultraviolet) and 730 nm (infrared), with greater intensity compared to LS (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wavelength spectrum (340–1000 nm) of treatments: LS—Led Full Spectrum LED Grow, in the cultivation environment, presenting photosynthetically active radiation of 67 μmol m−2 s−1; L1—LS + Led Full Spectrum LED Grow Light, with photosynthetically active radiation of 157 μmol m−2 s−1; L2—LS + Ultraviolet LED, with photosynthetically active radiation of 73 μmol m−2 s−1; L3—LS + Red LED, with photosynthetically active radiation of 124 μmol m−2 s−1; L4—LS + Blue LED, with a photosynthetically active radiation of 137 μmol m−2 s−1.

In treatment L2, which is composed of LS and Ultraviolet LED, there were verified peaks of light radiation intensity at wavelengths of 400 (ultraviolet), 460 (blue), and 630 nm (red), presenting a secondary peak at 730 nm (infrared), increasing the ratio of ultraviolet to blue and red compared to LS. For L3, which combined the standard lighting (LS) with Red LED, we observed peaks of light radiation intensity at wavelengths of 460 (blue) and 630 nm (red), presenting secondary peaks at 400 nm (ultraviolet) and 730 nm (infrared), increasing the range of light radiation intensity in the red and infrared region (at lower intensity) compared to LS. Also, in L4 treatment, which combined (LS) together with Blue LED, peaks of light radiation intensity at wavelengths of 460 (blue) and 630 nm (red) were observed, presenting secondary peaks at 400 nm (ultraviolet) and 730 nm (infrared), increasing the intensity of light radiation in the blue region at the peak of 460 nm compared to LS (Figure 2).

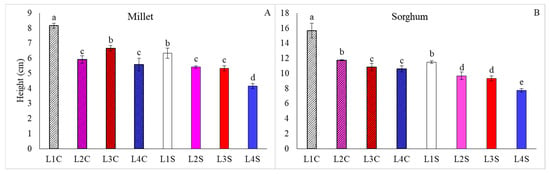

It was observed that, for the height of plants of both species, nicotinamide contributed to an increase in all treatments, except for L2 for millet (Figure 3). L1C and L4S were, respectively, the treatments that yielded the highest and lowest averages for this characteristic.

Figure 3.

Plant height of millet (A) and sorghum (B), grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters above the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

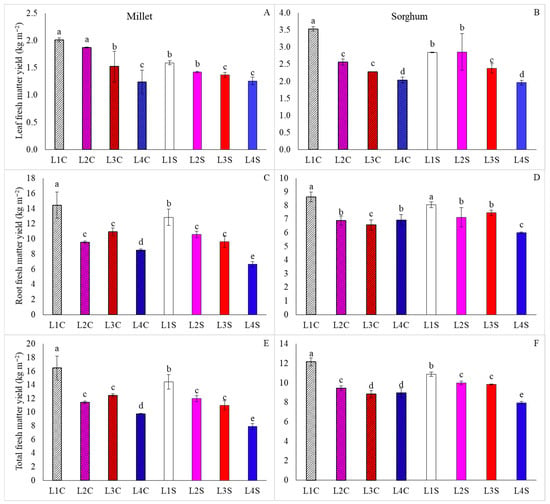

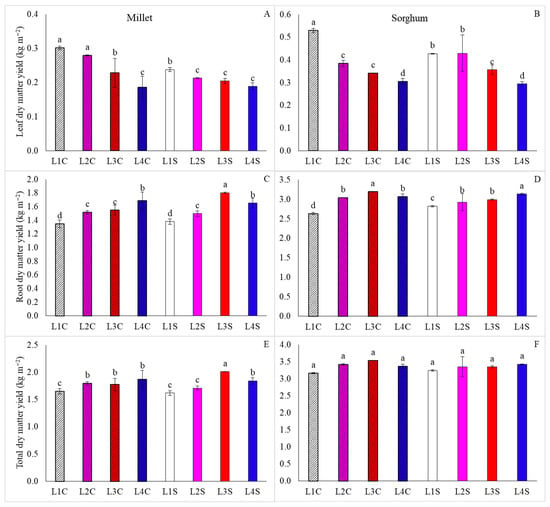

For leaf matter yield, the use of treatments L1C and L2C for millet, as well as L1C for sorghum, resulted in superiority (Figure 4A,B). However, it was found that for millet, the application of the vitamin also led to improved performance of plants subjected to L3 (Figure 4A), while for sorghum, the absence of nicotinamide resulted in gains when cultivation was carried out under L2 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Fresh leaf matter yield, fresh root matter yield, and total fresh matter yield of millet (A,C,E) and sorghum (B,D,F), grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters on the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

For fresh root matter yield, L1C was superior for millet and L1C and L1S for sorghum, and for both species, the lowest averages were obtained under L4S. These results were similar for total fresh matter yield, in which L1C was superior for both species and L4S was inferior (Figure 4E,F). Additionally, it was found that the application of nicotinamide was effective in increasing the total fresh matter yield when plants of both species were grown under L1 and L4 conditions.

For leaf dry matter yield, L1C and L2C resulted in higher averages for millet, with L1C also showing higher averages for sorghum. Additionally, the lowest results for millet were obtained under L4C, L2S, L3S, and L4S conditions, while sorghum exhibited the lowest averages under L4, regardless of vitamin presence (Figure 5A,B). In contrast, the highest root dry matter yields were achieved under L3S for millet and L3C for sorghum, whereas the use of L1 led to a decrease in this characteristic (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Leaf dry matter yield, root dry matter yield, and total dry matter yield of millet (A,C,E) and sorghum (B,D,F), grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters on the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

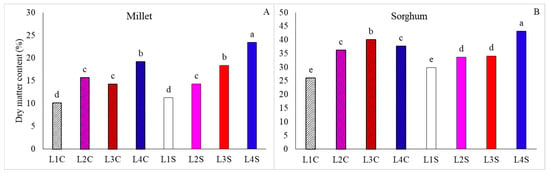

For millet, L3S resulted in the highest total dry matter yield, while L1C, L1S, and L2S indicated a reduction in these characteristics (Figure 5E). In contrast, for the total dry matter yield in sorghum, no differences were evident between treatments (Figure 5D). However, for both species, higher dry mass contents were obtained in L4S, whereas the lowest results were found for plants grown under L1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Dry matter content in millet (A) and sorghum (B) plants, grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters on the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

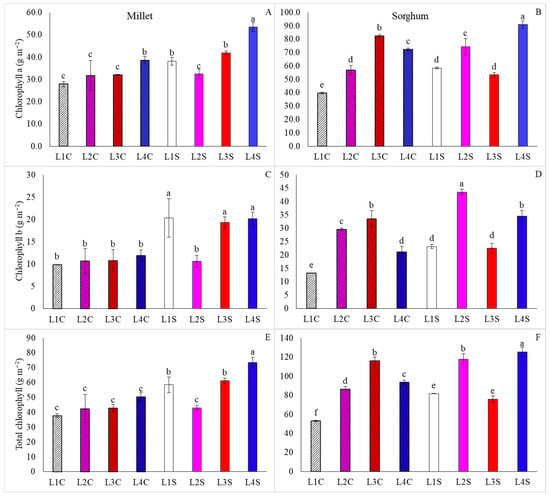

In millet, the highest chlorophyll a content was found in plants under L4S, followed by a combination of L4C, L1S, and L3S (Figure 7A). Additionally, the highest chlorophyll b and total contents in millet were observed in plants grown under L1S, L3S, and L4S, which outperformed the other treatments in both characteristics, with particular emphasis on L4S regarding total chlorophyll content (Figure 7C,E).

Figure 7.

Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll content in millet (A,C,E) and sorghum (B,D,F) plants, grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters above the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

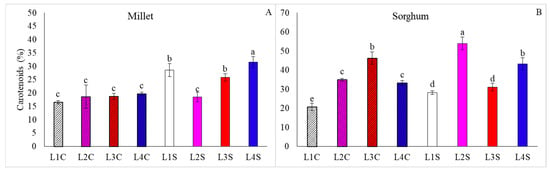

For sorghum, L4S yielded superior results for chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll contents, while L2S resulted in increased chlorophyll b contents (Figure 7B,D,F). Moreover, L1C was found to be the treatment where the plants exhibited the lowest levels of chlorophyll a, b, and total contents. In addition, only for plants grown under L3 was there no reduction in total chlorophyll content when nicotinamide was applied. These results were similar for carotenoid contents, with L4S, followed by L1S and L3S, resulting in higher levels of this pigment in millet plants (Figure 8A), while the treatments L2S, followed by L3C and L4S, promoted these levels in sorghum plants (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Carotenoid content in millet (A) and sorghum (B) plants grown as hydroponic green fodder under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters above the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

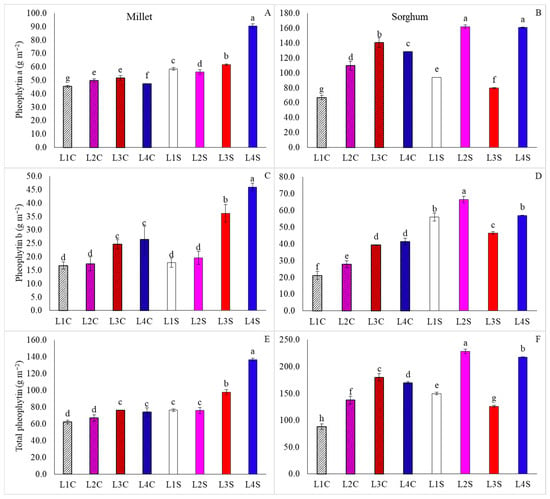

In millet, cultivation under L4S resulted in the highest levels of pheophytin a, b, and total, which was followed by the L3S treatment (Figure 9A,C,E). In addition, it was observed that the application of nicotinamide led to a reduction in total pheophytin under all light supplementation conditions (Figure 9E). For sorghum, the highest levels of pheophytin a were obtained in L2S and L4S (Figure 9B), while L2S caused an increase in the levels of pheophytin b and total for this species, followed by L1S and L4S for pheophytin b, and L4S for total pheophytin (Figure 9D,F). Thus, similar to millet, nicotinamide resulted in a decrease in total pheophytin levels, except for plants grown under L3.

Figure 9.

Pheophytin a, pheophytin b and total pheophytin content in millet (A,C,E) and sorghum (B,D,F) plants, grown as hydroponic green fodder, under different lighting conditions and nicotinamide applications. L1 = increased full spectrum LED; L2 = ultraviolet LED; L3 = red LED; L4 = blue LED; C = with nicotinamide; S = without nicotinamide; bars represent the treatment mean ± standard error; different letters above the mean bars indicate significant difference by the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Light Supplementation

Light energy is one of the indispensable factors for photosynthesis and, consequently, for the production of energy and accumulation of matter in plant organs [15]. The quality, intensity, and quantity of this light energy are involved in the regulation of growth, physiology, and other metabolic processes of plants [8]. In this sense, in indoor cultivation conditions, there is a need to adapt the system to meet the plants’ demand for light, which can be achieved using lamps with different wavelengths. Artificial lighting enables control over the intensity and quality of light energy that reaches plants, facilitating a range of morphophysiological responses, such as enhancing growth speed and the production of secondary metabolism compounds [16]. This can assist in producing materials with various characteristics, tailored to the needs of the producer or a specific market, as seen in the case of hydroponic green fodder.

As verified in the present study (Figure 4A,B), the use of monochromatic and ultraviolet lights can drastically reduce the production of fresh matter in cultivated plants, resulting from the reduced expansion of aerial organs [16]. This effect arises from the inability of plants to process all the energy received during supplementation, which implies the need to dissipate this excess energy in the form of heat, thereby reducing the quantum yield of electron transport, as well as the maximum quantum yield of primary photochemistry [17,18].

For dry mass accumulation, however, the effect of light supplementation can cause distinct responses among organs, leading to a decrease in the accumulation of dry mass in leaves (Figure 5A,B), while the dry mass of roots increases, whether from millet or sorghum, subjected to monochromatic lights and ultraviolet (Figure 5C,D). This is an adaptive response to oxidative stress, wherein the plant begins to invest in the development of resistance structures, such as roots, which optimize resource exploration, including water and nutrients, resulting from signaling for auxin production [19].

According to [20], the use of monochromatic lights also increases leaf temperature, stomatal conductance, and transpiration, reducing internal water content and increasing dry matter content, as verified in this study (Figure 6). We can highlight that the increase in light intensity leads to an increase in the biosynthesis of compounds and carbon incorporation, which leads to an increase in the dry matter of the plant [21]. However, greater light intensity leads to less water accumulation in the tissues, in addition to greater cell density and tissue compaction [22], resulting in lower water content in the plant, which causes a drop in the plant’s fresh matter.

In addition to the morphological changes, a considerable increase in chlorophyll and carotenoid levels was observed in plants grown under monochromatic supplementation (Figure 7 and Figure 8), which is accompanied by changes in pheophytin levels (Figure 9). Moreover, the accumulation of pigments is related to the occurrence of stress and the production of reactive oxygen species, as evidenced by the increase in pheophytin levels, which is associated with one of the stages of chlorophyll degradation [23].

For both species studied, supplementation with blue light increased leaf pigment levels (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9) and, according to [24], it directly stimulates the biosynthesis of chlorophylls and carotenoids through the activation of cryptochromes and phototropins. In this regard, other studies demonstrate that using wavelengths related to blue coloration promotes higher levels of secondary metabolites in plants [16]. This response relates to the activation of mechanisms associated with photosystem defense, including anatomical changes such as thickening of the leaf blade and the distribution of stomata, especially when plants are exposed to monochromatic blue lighting for extended periods [25].

Also, for long-term exposure to UV radiation, [25] showed a decrease in photosynthetic efficiency, with a significant reduction in leaf pigments, as was observed for millet (Figure 7E and Figure 8A) and, as reported by [26], this reduction indicates a lower photosynthetic efficiency, possibly due to oxidative stress induced by UV radiation that compromises the integrity of photosynthetic pigments, leading to a decrease in the photosynthetic capacity of plants. However, there is a distinct response on the part of sorghum, where the use of UV radiation considerably increases the levels of chlorophylls and carotenoids (Figure 7F and Figure 8B). This reaction is related to the adaptation of the species to the tropical climate, normally with high natural UV radiation [27], in which the increase in this type of radiation results in the increase in the levels of secondary metabolites related to plant defense, such as phenols and other compounds with antioxidant properties [28].

We can point out that at the wavelength of 460 nm (blue light supplementation, Figure 2), it is absorbed by both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, but with different intensities, with chlorophyll a having an absorption peak in the blue around 430–435 nm, but still absorbing significantly up to about 460 nm. However, chlorophyll b has an absorption peak in the blue close to 455–460 nm, that is, it absorbs more efficiently at 460 nm than chlorophyll a. At the wavelength of 630 nm (red light supplementation, Figure 2), chlorophyll a has an absorption peak in the red around 662–665 nm, but still presents some moderate absorption between 630 and 650 nm. Chlorophyll b has its absorption peak in the red, and is more displaced, generally around 640–645 nm, but its absorption at 630 nm is low to moderate. Wavelengths of 400 nm (supplementation of ultraviolet light, Figure 2) are mainly absorbed by chlorophyll a.

For supplementation with monochromatic red light, [29] points to a significant increase in hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde levels, compared to combinations of blue and red light. Supplementation with monochromatic red also resulted in more harmful effects for Pistacia vera, for which necrosis was observed, as well as the maintenance of high levels of leaf pigments [30], similar to what was observed for millet (Figure 7 and Figure 9).

On the other hand, the effect of light supplementation can provide different responses in relation to the plant species, cultivar, development stage, photoreceptors, among other characteristics [8,31], as well as the intensity and time of exposure can also alter the expected effect [31]. Some studies observed an increase in the growth of micropropagated horticultural plants with supplementation of monochromatic lights, such as blue light [8,31].

Blue light can stimulate the production of cytokinins in plants, thereby inducing shoot growth [8], regulating gibberellins [32], or stimulating the production of photosynthetic pigments and stomatal conductance, which culminate in a stimulus in photosynthetic activity, leading to an increase in height and dry matter [31], as observed in cucumber [28].

4.2. Exogenous Nicotinamide Application

The application of nicotinamide resulted in the alleviation of the deleterious effects resulting from the long period of exposure of green fodders to light supplementation, increasing the height and total fresh mass production values (Figure 3 and Figure 4), mainly of plants subjected to the control treatment and to monochromatic blue light, the most harmful among those studied. Exogenous application of nicotinamide results in significant improvements in physiological performance and initial growth, in addition to increasing plant height and fresh biomass production, indicating that nicotinamide acts as an effective biostimulant, especially under environmental stress conditions [33].

In general, nicotinamide also resulted in a decrease in photosynthetic pigment levels (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). This effect results from the vitamin’s action in adapting plants to the environment, in which an increase in the efficiency of plants in increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase and peroxidase, was observed [34]. This additional activity allows the plant to maintain its photosynthetic activity without the need for new investments in the production of pigments to replace those that are degraded. Under field conditions, in a tropical environment, the application of B vitamins resulted in an increase in gas exchange activity in coffee plants, which are susceptible to high radiation, indicating better functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus [35].

Nicotinamide also plays a prominent role in energy transport activities in the photosystem, as it participates in the formation of NADP+/NADPH, acting as an electron donor in anabolic reactions and as an electron acceptor in catabolic reactions [13]. This fact implies restructuring of the photosynthetic system under stress conditions, resulting in less electron accumulation and formation of reactive oxygen species [11].

In addition to its protective properties, several studies have demonstrated the biostimulant potential of nicotinamide. In hydroponic crops, the application of the vitamin has resulted in significant gains in plant growth, especially in the root system, and in the quality of melon [36] and pumpkin [37]) fruits. Similarly, for lettuce plants, the application of nicotinamide increased the gas exchange capacity, which resulted in a greater number of leaves and fresh mass [38]. Nicotinamide can modulate the biochemical pathways for phytomass production [39].

Stimuli for the development of aerial and root organs are also related to the application of nicotinamide during cultivation. The application of vitamin B3 can mimic the overexpression of the nicotinamidase 3 gene, responsible for the conversion of nicotinamide into nicotinic acid, which is used for the biosynthesis of NAD, playing an important role during all stages of plant development [40]. In addition, the application of nicotinamide to seeds, as performed at the beginning of green fodder cultivation in this study, can act as a priming agent, stimulating other genes related to plant protection and significantly improving the self-defense capacity of these plants [41].

In addition to its ability to stimulate plant growth, nicotinamide can be used as a preventative in environments prone to different types of stress. In air-conditioned environments, for example, the occurrence of high temperatures, salinization, or incorrect radiation supply can compromise productivity on different scales, which can be mitigated by applying the vitamin.

5. Conclusions

Cultivation under conditions of light supplementation with UV radiation or monochromatic lights results in increased light intensity by modifying the wavelength spectrum received by the plant, modification of the quality of photons received in relation to the energy level (UV > Blue > Red) that leads luminous (oxidative) stress and, consequently, lower green fodder development concerning height and fresh mass. Nicotinamide acts as a bioprotectant, attenuating the stressful effects and enabling greater productive efficiency in the production of hydroponic green fodder, particularly in indoor cultivation, which provides increased height and fresh mass for millet and sorghum green fodder. In contrast, the stress resulting from light supplementation can be used as a tool to increase carotenoid levels in plants and may be indicated for production systems that have this objective for biofortification of forages with bioactives with antioxidant effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.S. and E.P.V.; methodology, G.R.S. and E.P.V.; validation, S.F.d.L., C.E.d.S.O., M.C.M.T.F. and F.P.d.A.P.B.; formal analysis, F.F.d.S.B.; investigation, G.R.S., E.D.C.B. and E.P.V.; resources, E.P.V.; data curation, G.R.S., E.D.C.B., F.P.d.A.P.B. and E.P.V.; writing—original draft peparation, G.R.S. and E.P.V.; writing—review and editing, G.C., S.F.d.L., C.E.d.S.O., E.C. and M.C.M.T.F.; visualization, G.C., C.E.d.S.O., E.C. and M.C.M.T.F.; supervision, E.P.V.; project administration, E.P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES)—Financing Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the State University of Mato Grosso do Sul and to the Research Group for Innovation and Advancement of Agriculture—INNOVA, for the availability of structure and technical personnel.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouadila, S.; Baddadi, S.; Skouri, S.; Ayed, R. Assessing heating and cooling needs of hydroponic sheltered system in mediterranean climate: A case study sustainable fodder production. Energy 2022, 261, 125274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Mobtaker, H.; Sharifi, M.; Taherzadeh-Shalmaei, N.; Afrasiabi, S. A new method for green forage production: Energy use efficiency and environmental sustainability. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 363, 132562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mathur, M.; Karnani, M.; Dutt Choudhary, S.; Jain, D. Hydroponics: An alternative to cultivated green fodder: A review. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2018, 6, 791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, P.K.; Swain, B.K.; Singh, N.P. Production and utilization of hydroponics fodder. Indian J. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Peñailillo, F.; Gutter, K.; Vega, R.; Silva, G.C. New Generation Sustainable Technologies for Soilless Vegetable Production. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.S.; Sultan, M.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Aleem, M.; Balasundram, S.K. Present status and challenges of fodder production in controlled environments: A review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.S.; Felipe, S.H.S.; Silva, T.D.; Castro, K.M.; Mamedes-Rodrigues, T.C.; Miranda, N.A.; Rios-Rios, A.M.; Faria, D.V.; Fortini, E.A.; Chagas, K.; et al. Light quality in plant tissue culture: Does it matter? Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 2018, 54, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Manivannan, A.; Wei, H. Light Quality-Mediated Influence of Morphogenesis in Micropropagated Horticultural Crops: A Comprehensive Overview. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4615079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrifai, O.; Hao, X.; Liu, R.; Lu, Z.; Marcone, M.F.; Tsao, R. LED-Induced Carotenoid Synthesis and Related Gene Expression in Brassica Microgreens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4674–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Baumgardt, C.; Llewellyn, D.; Zheng, Y. Different Microgreen Genotypes Have Unique Growth and Yield Responses to Intensity of Supplemental PAR from Light-emitting Diodes during Winter Greenhouse Production in Southern Ontario, Canada. HortScience 2020, 55, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.F.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Alves, V.C.D.; Arguelho, J.C.; Pião, J.A.; de Seron, C.; Martins, M.B.; Witt, T.W.; Serafim, G.M.; Contardi, L.M. Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, E.P.; Silva Filho, M.X.; Costa, A.C.; Bortolheiro, F.P.A.; Serafim, G.M.; Lima, S.F.; Seron, C.C.; Martins, M.B.; Dantas Alves, V.C. Vitamins can ameliorate the effects of water deficit on the gas exchange and initial growth of maize. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 27, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.S.; Binotti, F.F.; Costa, E.S.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Binotti, E.D.C.; Salles, J.S.; Salles, S.S. Vitamin B3 with action on biological oxide/reduction reactions and growth biostimulant in Chlorella vulgaris cultivation. Algal. Res. 2023, 76, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Moller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Fisiologia e Desenvolvimento Vegetal; ArtMed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, M.; Agati, G.; Fini, A.; Guidi, L.; Sebastiani, F.; Tattini, M. Unveiling the shade nature of cyanic leaves: A view from the “blue absorbing side” of anthocyanins. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, L.; Arab, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Seif, M.; Lastochkina, O.; Li, T. Effects of growth under different light spectra on the subsequent high light tolerance in rose plants. AoB Plants 2018, 10, ply052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliniaeifard, S.; Seif, M.; Arab, M.; Mehrjerdi, M.Z.; Li, T.; Lastochkina, O. Growth and Photosynthetic Performance of Calendula Officinalis under Monochromatic Red Light. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2018, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A.U.; Kundariya, H.S.; Samantaray, D.; Dopp, I.J.; Allu, A.D.; Mackenzie, S.A. Short-Term High Light Stress Analysis Through Differential Methylation Identifies Root Architecture and Cell Size Responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3269–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, P.; Kong, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Liang, Z.; et al. Grapevine plantlets respond to different monochromatic lights by tuning photosynthesis and carbon allocation. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemifar, Z.; Sanjarian, F.; Naghdi Badi, H.; Mehrafarin, A. Varying levels of natural light intensity affect the phyto-biochemical compounds, antioxidant indices and genes involved in the monoterpene biosynthetic pathway of Origanum majorana L. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.Á.; Omena-Garcia, R.P.; Condori-Apfata, J.A.; Costa, P.M.; Silva, N.M.; DaMatta, F.M.; Zsogon, A.; Araujo, W.L.; de Toledo, P.E.A.; Sulpice, R. Specific leaf area is modulated by nitrogen via changes in primary metabolism and parenchymal thickness in pepper. Planta 2021, 253, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Ito, H. Chlorophyll Degradation and Its Physiological Function. Plant Cell. Physiol. 2025, 66, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, T.; Sui, J.; Wang, H. Cryptochrome-mediated blue-light signal contributes to carotenoids biosynthesis in microalgae. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1083387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huché-Thélier, L.; Crespel, L.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Morel, P.; Sakr, S.; Leduc, N. Light signaling and plant responses to blue and UV radiations—Perspectives for applications in horticulture. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, A.; Choudhary, K.K. Revisiting the role of phenylpropanoids in plant defense against UV-B stress. Plant Stress 2023, 7, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.R.; Ruhland, C.T. Ultraviolet-B Stress Increases Epidermal UV-Screening Effectiveness and Alters Growth and Cell-Wall Constituents of the Brown Midrib bmr6 and bmr12 Mutants of Sorghum bicolor. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210, e12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Kubota, C. Physiological responses of cucumber seedlings under different blue and red photon flux ratios using LEDs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartucca, M.L.; Guiducci, M.; Falcinelli, B.; Del Buono, D.; Benincasa, P. Blue: Red LED Light Proportion Affects Vegetative Parameters, Pigment Content, and Oxidative Status of Einkorn (Triticum monococcum L. ssp. monococcum) Wheatgrass. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8757–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, D.; Soufi, S.; Bettaieb, T.; Werbrouck, S.P.O. Effects of Monochromatic Light on Growth and Quality of Pistacia vera L. Plants 2023, 12, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Murad, M.; Razi, K.; Jeong, B.R.; Samy, P.M.A.; Muneer, S. Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) as Agricultural Lighting: Impact and Its Potential on Improving Physiology, Flowering, and Secondary Metabolites of Crops. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cao, K.; Hao, Y.; Song, S.; Su, W.; Liu, H. Hypocotyl elongation is regulated by supplemental blue and red light in cucumber seedling. Gene 2019, 707, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T.A.N.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Binotti, F.F.S.; Costa, E.; Lima, S.F.; Sant’Ana, G.R.; Bartolheiro, F.P.A. Nicotinamide Increases the Physiological Performance and Initial Growth of Maize Plant. Int. J. Agron. 2024, 2024, 5567314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolik, B.; Sędzik-Wójcikowska, M. Examining Nicotinamide Application Methods in Alleviating Lead-Induced Stress in Spring Barley. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, E.P.; Souza, M.I.; Bastos, A.A.; Bortolheiro, F.P.A.P.; Seron, C.C.; Martins, M.B.; de Lima, S.F.; Dantas Alves, V.C. Vitamins enhance the physiological characteristics of coffee cultivated in the Brazilian Cerrado. Vegetos 2024, 38, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Conceição, J.S.; Lima, S.F.; Binotti, F.F.S.; Bortolheiro, F.P.A.P.; de Silva Oliveira, C.E.; Costa, E.; Lafleur, L. Plant–Vitamin–Microorganism Interaction in Hydroponic Melon Cultivation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, E.P.; Sant’Ana, G.R.; Lima, S.F.; Gaete, F.I.M.; Bortolheiro, F.P.A.P.; Serafim, G.M. Biostimulant potential of Azospirillum brasilense and nicotinamide for hydroponic pumpkin cultivation. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2024, 28, e278962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, E.P.; Seron, C.C.; Leonel, E.A.S.; Lima, S.F.; Araujo, S.L.; Martins, M.B. Do vitamins affect the morphophysiology of lettuce in a hydroponic system? Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2023, 27, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Yao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zeng, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Reciprocal regulation between nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism and abscisic acid and stress response pathways in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.; Bashir, K.; Matsui, A.; Tanaka, M.; Sasaki, R.; Oikawa, A.; Hirai, M.Y.; Chaomurilege; Zu, Y.; Kawai-Yamada, M.; et al. Overexpression of nicotinamidase 3 (NIC3) gene and the exogenous application of nicotinic acid (NA) enhance drought tolerance and increase biomass in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, C.; Berglund, T.; Ohlsson, A.B. Transcriptome analysis shows nicotnamide seed treatment alters expression of genes involved in defense and epigenetic processes in roots of seedlings of Picea abies. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).