Abstract

Lead (Pb) contamination severely threatens plant health and biodiversity, particularly in mining-affected ecosystems. The phytohormone, salicylic acid (SA), plays a crucial role in regulating plant stress responses. Here, the effect of SA supplementation on the in vitro response of Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis, a critically endangered Mediterranean shrub, to Pb stress (50 μM Pb(NO3)2) was evaluated. SA dose pretreatment (100 μM) was selected based on phenolic accumulation in leaf tissues. Physiological and biochemical parameters—including mineral content, photosynthetic performance, total phenolics, and antioxidant activity—were quantitatively analyzed. SA pretreatment markedly reduced Pb accumulation (25%) while promoting Fe (73%), K (29%), and Mn (15%) uptake. It also alleviated Pb-induced photosynthetic impairment, preserved chloroplast integrity, increased chlorophyll content, and reduced the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products. Furthermore, SA promoted the accumulation of phenolic compounds—such as flavonoids, (+)-catechin, gallic acid, and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives—in Pb-treated shoots, resulting in increased antioxidant capacity, as reflected by DPPH and FRAP assays, and protection against lipid autooxidation. However, no differential effect of SA pretreatment on DNA protection against oxidative damage was observed. Overall, SA acted as an effective priming agent, maintaining mineral homeostasis, photosynthetic stability, and antioxidant defense under Pb stress. These findings highlight its potential for enhancing plant resilience to Pb toxicity and for supporting the conservation and reintroduction of C. heterophyllus in contaminated habitats.

1. Introduction

The loss of biological diversity driven by human activities has become a global threat with far-reaching ecological and human health consequences [1,2]. Climate change is expected to further intensify this crisis, particularly in climate-sensitive regions [3,4]. Notably, the Mediterranean basin, one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots [5], is especially vulnerable due to the combined effects of extreme weather events and increasing anthropogenic pressures [6]. Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis, commonly known as the Cartagena rockrose, is an esthetically striking endemic species of the Western Mediterranean basin. Formerly abundant in the Sierra Minera of Cartagena, its population declined drastically in the 1960s following extensive mining activities and habitat destruction [7]. Today, the species is listed as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2024), ranking among the most endangered plants in Spain [7,8].

For critically endangered species, biotechnology tools such as in vitro culture techniques provide essential strategies for preserving genetic resources and producing healthy plant material, thereby ensuring the long-term conservation of pathogen-free individuals [9,10]. Additionally, the optimization of culture conditions and elicitation strategies can enhance the accumulation of bioactive metabolites that reinforce plant defense mechanisms [11,12]. Among the most widely used elicitors, salicylic acid (SA) is known to promote the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites both in planta and in vitro systems. SA treatments have been shown to stimulate the production of alkaloids [13], terpenoids [14], and, most notably, phenolic compounds [15,16,17,18,19]. Moreover, SA has also been reported to enhance plant vigor, biomass production, and stress tolerance through cross-talks with other phytohormones, particularly under abiotic stress conditions such as heavy metals (HMs) [20,21,22]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that SA alleviates HM toxicity by modulating metal uptake and/or sequestration in plant organs [23,24,25]. SA contributes to cellular redox homeostasis by activating both antioxidant enzymes and low-molecular-weight metabolites responsible for reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, thereby protecting membrane stability and integrity [23,24,25]. Additionally, SA enhances photosynthetic efficiency, promotes stomatal regulation, and inhibits chlorophyll-degrading enzymes [23,24,25]. Emerging evidence further suggests that SA influences plant–microbiome interactions under HM stress, thereby contributing to enhanced HM-tolerance [24].

Lead (Pb) is one of the most toxic and widespread pollutants in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [26]. In the Cartagena–La Unión Mining District, Pb levels can reach up to 8000 mg kg−1 [27], posing a severe threat to plant survival. Despite being a non-redox metal, Pb exerts its toxicity mainly through the production of ROS, which overwhelm cellular antioxidant defenses. The oxidative stress induced by Pb exposure in plant cells can damage vital macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA [26,28].

We previously demonstrated that SA induces changes in phenolic metabolism in in vitro shoots of C. heterophyllus [29]. Phenolic compounds play a central role in plant stress protection, primarily due to their antioxidant activity [30]. Moreover, it is widely reported that plants with higher phenolic levels exhibit improved acclimation and ecological fitness under environmental stress conditions, which is particularly relevant for conservation strategies [30].

However, no study has addressed how SA modulates phenolic metabolism under Pb stress in C. heterophyllus. Therefore, this study aimed to assess whether SA-induced phenolic accumulation could alleviate the phytotoxic effects of Pb exposure. Given the dose-dependent nature of SA responses [16,18,19], the specific objectives were as follows: (i) to evaluate the effects of different SA doses on phenolic accumulation and subcellular distribution and (ii) to test whether SA pretreatment contributes to the alleviation of Pb-induced oxidative stress in relation to phenolic accumulation. The study will assess changes in mineral content, photosynthesis performance, antioxidant activity, and the profile of bioactive phenolic compounds. From a practical perspective, this work explores the potential application of SA treatments in conservation programs for this threatened plant species. The goal is to enhance its vigor and facilitate successful reintroduction into natural habitats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Culture Conditions

Explants of C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis were obtained from in vitro cultures previously established in our laboratory (Figure S1) [29]. Shoots were grown on Driver and Kuniyuki (DKW) medium [31] supplemented with casein hydrolysate (250 mg L−1), sucrose (3% w/v), and 0.8% Difco Bacto agar, and maintained by bimonthly subcultures. Cultures were kept at 25 °C under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and a photon flux density of 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Sanyo, versatile environmental test chamber, MLR-351H, Osaka, Japan).

2.2. SA Pretreatment and Pb Exposure

Explants were cultured on freshly prepared agar-solidified media as described above and were adjusted to pH 6.0 with 3 mM MES-KOH before autoclaving (121 °C for 20 min). After sterilization, filter-sterilized hydroalcoholic SA solutions (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands, S1367, purity > 99%) were added to obtain the final concentrations of 0, 10, and 100 μM. Shoots were grown for 8 weeks under the previously described light and temperature conditions and subsequently used for microscopy analyses (see Section 2.3).

For combined SA and Pb treatments, the Pb concentration was fixed at 50 μM, following U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guidelines for permissible levels of trace elements in irrigation water [32]. Because Pb easily precipitates in the presence of phosphate in the basal media [33], Cistus shoots were first grown for 6 weeks on agar-solidified media supplemented with 100 μM SA or without SA (control). Prior to Pb exposure, shoots were individually transferred to vented tubes (80 mL; 13 × 5 cm; 14 shoots per treatment) each containing 1 mL of liquid DKW medium and cultured for 14 days to acclimatize to liquid conditions. The use of liquid medium also minimized the potential interference of agar components with Pb bioavailability and metal-related plant responses [34]. Subsequently, shoots were placed in tubes containing either 1 mL of 500 μM KNO3 or 1 mL of 500 μM KNO3 supplemented with 100 μM of SA for 3 days. Finally, shoots were exposed to Pb for 7 days by transferring them to tubes containing 1 mL of 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. The control tubes contained 1 mL of 100 μM KNO3. The pH of these solutions was adjusted to 5.0 with 3 mM MES-KOH to prevent Pb precipitation. A detailed description of the experimental setup is provided in Supplementary Figure S2. After the exposure period, shoots were removed, and the basal regions that had been in contact with the solution were excised by cutting a few millimeters above the liquid interface. The experiment was repeated twice, each time including three biological replicates, with each replicate consisting of three pooled in vitro-cultured shoots per treatment. For biochemical analyses, pooled samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Microscopic Analyses

Leaf cross sections (1–2 mm2) were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with or without 1% caffeine for 4 h at 4 °C. Samples were post-fixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in epoxy resin. Semi-thin (0.5 μm) and ultra-thin (50–70 nm) sections were cut using a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome. Ultra-thin sections were collected on formvar-coated nickel grids (200 mesh), stained with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate and examined on a Philips Tecnai 12 (FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. Semithin sections were stained with 0.1% (w/v) toluidine blue and observed using a Leica DMRB light microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were acquired using a digital camera (Leica DC 500; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) controlled by Leica IM50 software (version 1.20).

2.4. Nutrient and Pb Concentrations

Approximately 100 mg of fine dry-sample powder was incinerated at 450 °C for 8 h and subsequently digested in 1 mL of concentrated HNO3 (65% Merck, Suprapur). Concentrations of K, Ca, Mg, P, Fe, Zn, Mn, and Pb were determined by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent 7500A; Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), as previously described [35,36].

2.5. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Determination and Chlorophyll and Carotenoids Analysis

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured in Cistus leaves at the end of the experiment, between 9:00 and 11:00 h (GMT), using a PAM-210 chlorophyll fluorometer system (Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany), as previously described [29]. Briefly, leaves were dark-adapted for 25 min using leaf clips (Hansatech Instruments Ltd., King’s Lynn, UK) to determine the minimal fluorescence level (F0). A saturating light pulse was then applied to obtain the maximal fluorescence (Fm) in the dark-adapted stage. The ratio between the variable fluorescence (Fv = Fm − F0)/ and Fm (Fv/Fm) was used to determine the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry [37].

Chlorophyll a (Chla), chlorophyll b (Chlb), and total carotenoid contents were quantified by following the established routine protocols described in our laboratory [35,38]. In brief, ~100 mg of shoot samples (powdered in liquid nitrogen) was extracted twice with 0.6 mL of ice-cold 100% HPLC-grade methanol using sonication at 40 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 15,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, the resulting methanolic supernatants were pooled and used for the spectrophotometric quantification of chlorophylls and carotenoids, based on the extinction coefficients and equations previously reported [39].

2.6. Total Phenolics and Flavonoids Determinations

Methanolic extracts were also used to determine soluble total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) by following previously reported protocols [29,40,41]. In short, TPC was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, with caffeic acid as the standard, and results were expressed as caffeic acid equivalents (CAEs) per gram FW. TFC was determined using the aluminum chloride method with (+) catechin as the standard, and results were expressed as catechin equivalents (CatE) per gram FW.

2.7. HPLC Analysis

HPLC analyses were performed using a Waters 2695 HPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a 2996 Photodiode Array Detector (PDA). The separation of compounds was carried out using a LiChroCART C-18 reversed-phase column (250 mm × 4 mm i.d., 5 μm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), following the method described by [42]. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (solvent A) and 0.1% (w/v) ortho-phosphoric acid in water (solvent B), with the following gradient program: 10% A and 90% B, 0–3 min; 20% A and 80% B, 3–10 min; 35% A and 65% B, 10–12 min; 35% A and 65% B, 12–15 min; 10% A and 90% B, 15–18 min; and 10% A and 90% B, 18–22 min. The flow rate was 1 mL min−1 and the injection volume was 20 μL. Phenolic compounds were identified by comparing retention times and UV spectra with those of authentic standards [caffeic acid (assay ≥ 98%), (+)-catechin (assay ≥ 98%), chlorogenic acid (assay ≥ 95%), ferulic acid (assay ≥ 98%), gallic acid (assay ≥ 98%), p-coumaric acid (assay ≥ 98%), and salicylic acid (assay ≥ 99%) (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain)]. Quantification was based on peak-area integration at each compound’s specific absorbance maximum, using external calibration curves based on seven concentrations of each standard, ranging from 10 to 1000 μM.

2.8. Antioxidant Activity Assays

The total antioxidant capacity of the methanolic extracts was assessed using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical) and FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) assays. DPPH radical scavenging activity was expressed as micromoles of DPPH reduced per gram of fresh weight (FW), using an extinction coefficient of 12,500 M−1 cm−1 at 517 nm [43]. Reducing power was expressed as micromoles of Fe(II) per gram FW, based on a seven-point FeSO4·7H2O standard curve ranging from 0 to 150 μM [19].

The inhibitory effect on lipid peroxidation was determined by monitoring conjugated diene formation at 234 nm, using linoleic acid as the substrate [19]. The results were expressed as the difference in conjugated diene levels between the control (reaction media without extract) and extract-treated reaction media. Conjugated diene concentrations were calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 25,000 M−1 cm−1.

DNA protection capacity was evaluated using the copper–phenanthroline-dependent DNA oxidation assay [44]. Briefly, DNA damage was quantified by measuring the formation of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) (λ = 532 nm; ε = 155 mM−1 cm−1) and is expressed as micromoles of malondialdehyde (MDA) per gram FW.

2.9. Lipid Peroxidation and H2O2 Content Determination

Lipid peroxidation was estimated by quantifying MDA levels using the TBARS assay [45]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content was determined using the ferric–xylenol orange method [46], with minor modifications [29].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were obtained two independent experiments, each including three biological replicates of three pooled shoots. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and the post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test (p ≤ 0.05). Analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 28.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All graphs were performed using R statistical software version 4.3.1 (https://www.R-project.org/, accessed on 14 November 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of SA Pretreatment Dose on Foliar Phenolic Accumulation in Cistus

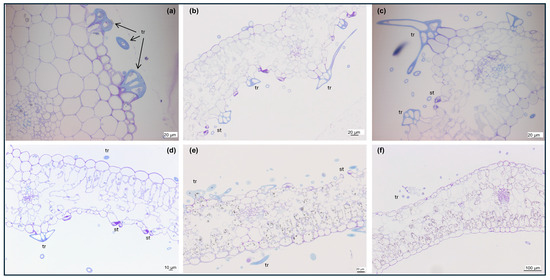

The impact of SA pretreatment on phenolic accumulation in Cistus leaves was examined using light and electron microscopy. Light microscopy observations revealed that, in the cross section, Cistus leaves showed a uni-layered epidermis with rectangular cells, covered by a smooth and thick cuticle and dendritic trichomes on both surfaces (Figure 1a–f). The adaxial epidermis cells were larger than the abaxial ones. Leaves were hypostomatic, with kidney-shaped guard cells. The palisade parenchyma consisted of a single layer of elongated cells, whereas the spongy parenchyma was composed of irregularly shaped cells. No morphological differences were observed between the control (Figure 1a,d) and the shoots pretreated with SA, either at 10 μM (Figure 1b,e) or 100 μM (Figure 1c,f). In toluidine blue-stained sections without caffeine, phenolic-rich cells exhibited cytoplasmic darkening, intensified in SA-pretreated shoots (Figure 1b,c). When caffeine was included during fixation, toluidine blue staining revealed distinct, blue-stained inclusions in phenolic-rich cells, indicating the stabilization and clearer visualization of phenolic deposits (Figure 1d–f).

Figure 1.

Light micrographs of toluidine blue-stained section of in vitro C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis leaves fixed without (a–c) or with (d–f) caffeine from control (a,d), 10 μM SA (b,e), and 100 μM SA (c,f)-treated shoots. Abbreviations: tr, trichome; st, stomata.

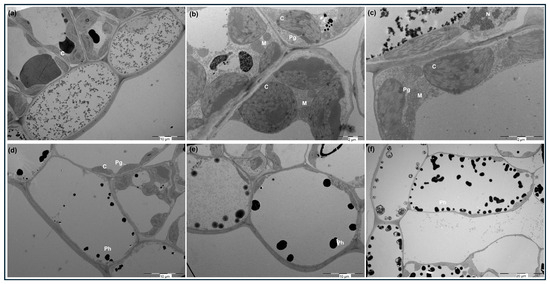

Transmission electron microscopy images of leaf cells from non-SA-treated shoots revealed oblong chloroplasts containing few granal stacks, scarce starch grains, and a low number of plastoglobuli (Figure 2a,d). In contrast, mesophyll chloroplasts from SA-treated shoots showed a markedly higher abundance of plastoglobuli (Figure 2b,c), while the overall chloroplast morphology remained comparable to that of the control. TEM images also confirmed that phenolic deposits were mainly localized in the vacuoles of epidermal and mesophyll cells (Figure 2e,f), with higher abundance in leaves from SA-treated shoots. In caffeine-fixed samples, these phenolic deposits appeared as a large, rounded electron-dense material (osmophilic bodies) positioned adjacent to the tonoplast, particularly in leaves from shoots treated with 100 μM SA (Figure 2f). These ultrastructural observations were consistent with the histochemical patterns previously described.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) of C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis leaves fixed without (a–c) or with (d–f) caffeine from control (a,d), 10 μM SA (b,e), and 100 μM SA (c,f)-treated shoots. Abbreviations: C, chloroplast; M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; Ph, electro-dense deposit of phenolic compounds; Pg, plastoglobuli.

Furthermore, dose–response curves showed that 100 μM SA induced a higher accumulation of total phenolic compounds (TPCs) in Cistus shoots (Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, this concentration (100 μM SA) was selected for subsequent analyses to investigate the potential mechanisms underlying SA-mediated protection against Pb exposure.

3.2. Effect of SA Pretreatment on Shoot Mineral Content Under Pb Exposure

Pb exposure alone had negligible effects on K, P, and Mn concentrations, but it reduced Ca, Fe, and Zn levels in shoot tissues, although only the reduction in Zn was statistically significant (Table 1). While Pb-induced changes in Zn remained unaffected by SA, Fe accumulation increased significantly both in the absence and presence of Pb. Furthermore, under Pb stress, SA not only decreased Pb accumulation (~0.75-fold), but also enhanced K (~1.3-fold) and Mn (~1.1-fold) concentrations compared with shoots exposed to Pb alone.

Table 1.

Effect of SA pretreatment (100 μM) on mineral content in C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis in vitro shoots exposed for 7 days to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. Data represent the means ± SD from two independent experiments, each one with three biological replicates of three pooled shoots (n = 6). Values followed by different letters in a row are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test. nd, not detected. Numbers in parentheses represent percentages of control values from SA-untreated shoots.

3.3. Effect of SA Pretreatment on Chlorophyll a Fluorescence, Photosynthetic Pigment Content, and Chloroplast Ultrastructure Under Pb Exposure

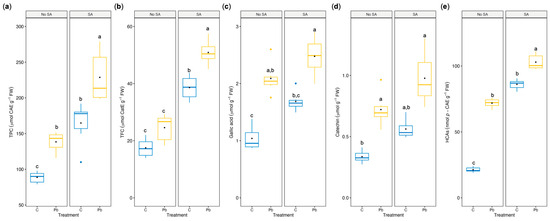

As illustrated in Figure 3a, Pb treatment reduced the Fv/Fm ratio by approximately 16% in SA-free shoots, resulting in values below the optimal range of 0.74–0.85 [47]. Pb-induced decline in the Fv/Fm ratio was effectively reversed by SA pretreatment. Furthermore, Pb exposure decreased chlorophyll a and b contents by about 30% in SA-free shoots, whereas this reduction was partially mitigated in SA-pretreated shoots (Figure 3b,c). In contrast, carotenoid concentrations did not differ significantly among treatments (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Effect of SA pretreatment (100 μM) on Fv/Fm ratio (a), chlorophyll a (b), chlorophyll b (c), and carotenoid (d) contents in C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis in vitro shoots exposed for 7 days to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), the mean (black dot), the interquartile range (box), and whiskers extending to 1.5× IQR. Data are based on two independent experiments, each with three biological replicates of three pooled shoots (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.05; Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test).

TEM images revealed that the chloroplast’s ultrastructure exhibited pronounced morphological alterations under Pb exposure. In Pb-control shoots, chloroplasts changed from oblong to enlarged spindle-like shapes, showing an increased number and size of starch grains, and clear signs of grana thylakoid degeneration (Figure 4a). In contrast, in SA-Pb shoots the internal lamellar system remained preserved, displaying a well-defined and orderly arrangement of thylakoid membranes (Figure 4b), and overall, chloroplast features closely resembled those observed in the SA controls (see Figure 2c). TEM images of caffeine-fixed samples revealed a higher number of phenolic deposits in the vacuoles of epidermal and mesophyll cells in both Pb-control (Figure 4c) and Pb-SA (Figure 4d)—treated shoots, compared with their respective untreated Pb shoots (see Figure 2d,f).

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) of in vitro Cistus leaves fixed without (a,b) or with (c,d) caffeine. Panels show Pb-treated control shoots (a,c) and shoots subjected to combined Pb and salicylic acid (SA) treatment (b,d). Abbreviations: C, chloroplast; CW, cell wall; M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; Ph, electro-dense deposit of phenolic compounds; Pg, plastoglobule; S, starch grains.

3.4. Effect of SA Pretreatment on the Accumulation of Phenolic Compounds Under Pb Exposure

TEM images revealed the localization of electron-dense phenolic deposits adjacent to the tonoplast, particularly in leaves from Pb-SA-treated shoots (Figure 4d). To further investigate this observation, total soluble phenolics and flavonoids were quantified. As shown in Figure 5a,b, Pb exposure led to a marked increase in total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC), by approximately 1.9-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively. This response was further enhanced by SA pretreatment, resulting in ~2.6-fold and ~2.9-fold increases in TPC and TFC, respectively. SA alone also elevated TPC and TFC levels (~1.8-fold and ~2.2-fold, respectively) compared to the controls.

Figure 5.

Effect of SA pretreatment (100 μM) on total soluble phenols (TPC) (a), flavonoids (TFC) (b), gallic acid (c), catechin (d), and HCAs (e) in C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis in vitro shoots exposed for 7 days to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. Gallic acid, catechin, and HCA contents were determined using reverse-phase HPLC-DAD. Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), the mean (black dot), the interquartile range (box), and whiskers extending to 1.5× IQR. Data are based on two independent experiments, each with three biological replicates of three pooled shoots (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.05; Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test).

Furthermore, HPLC-DAD analysis was performed to identify and quantify specific phenolic compounds (Supplementary Figure S4). Gallic acid (GA) and (+)-catechin were clearly detected and quantified at 280 nm. In addition, at 310 nm, a group of peaks with a retention time around 14–17 min exhibited UV spectra consistent with hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (HCAs), characterized by a maximum absorption between 320 and 330 nm and a shoulder around 300 nm. Although the specific compound could not be identified, they were grouped and quantified as HCAs. As shown in Figure 5c,e, Pb exposure increased the accumulation of GA, (+)-catechin, and HCAs by ~2.0-fold, ~2.1-fold, and ~3.4-fold, respectively. These levels were further elevated in SA-treated shoots (~2.4-fold, ~2.9-fold, and ~4.8-fold, respectively). SA alone also caused a moderate increase in GA and (+)-catechin (~1.6-fold), and a substantial rise in HCAs (~4.0-fold).

3.5. Effect of SA Pretreatment on Antioxidant Activity and Biomolecule Protection Capacity Under Pb Exposure

Total antioxidant activity, measured by both the DPPH free radical scavenging and FRAP assays, significantly increased in SA-treated shoots (~2.5-fold and ~1.6-fold, respectively) and was further stimulated under Pb exposure (~4.7-fold and ~2.5-fold, respectively). In contrast, Pb alone had no significant effect on antioxidant activity (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6.

Effect of SA pretreatment (100 μM) on antioxidant activity and biomolecule protection capacity in C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis in vitro shoots exposed for 7 days to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. (a) DPPH radical scavenging activity; (b) FRAP assay; (c) inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation assessed by conjugated diene formation; and (d) DNA protection against oxidative damage assessed by the copper–phenanthroline assay. Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), the mean (black dot), the interquartile range (box), and whiskers extending to 1.5× IQR. Data are based on two independent experiments, each with three biological replicates of three pooled shoots (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.05; Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test).

To evaluate the protective capacity of Cistus methanolic extracts on biomolecules, we tested their ability to inhibit the peroxidation of linoleic acid under autooxidation conditions and to modulate copper–phenanthroline-dependent DNA oxidation. As shown in Figure 6c, lipid peroxidation inhibition remained unchanged following treatment with either Pb or SA alone but was significantly enhanced (~1.6-fold) in Pb + SA-treated shoots. Figure 6d shows that extracts from Pb-, SA-, and SA-Pb-treated shoots exhibited significantly higher protection against DNA degradation compared to the controls. Although the difference was not statistically significant, the SA-Pb treatment showed a slightly lower protective capacity (33%) than the Pb and SA treatments alone (42%).

There were no consistent correlations between the DNA oxidation method and the rest of the assays used to determine the antioxidant activity (Supplementary Figure S5). High positive correlations were found between phenolics (TPC, TFC, GA, catechin, and HCAs) and the antioxidant activity of the extracts in the DPPH, FRAP, and lipid peroxidation inhibition assays (r > 0.6, p ≤ 0.01; Supplementary Figure S5). In contrast, the DNA oxidation method showed a negative correlation with TPC and TFC (r < −0.4, p ≤ 0.05;) and even stronger negative correlations with GA (−0.56, p ≤ 0.01) and HCAs (−0.69, p ≤ 0.01; Supplementary Figure S5), indicating that higher phenolic accumulation is associated with greater DNA protection.

3.6. Effect of SA Pretreatment on H2O2 Levels and Lipid Peroxidation Under Pb Exposure

No statistically significant changes were observed in the H2O2 content in shoots exposed to Pb (i.e., Pb and SA-Pb treatments), although a slight increase was detected in shoots treated with SA alone (Figure 7a). In contrast, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, a marker of lipid peroxidation, increased by about 40% upon Pb exposure in SA-free shoots, but by less than 20% in SA-Pb-treated shoots (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Effect of SA pretreatment (100 μM) on H2O2 concentration (a) and lipid peroxidation (b) in C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis s in vitro shoots exposed for 7 days to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2. Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), the mean (black dot), the interquartile range (box), and whiskers extending to 1.5× IQR. Data are based on two independent experiments, each with three biological replicates of three pooled shoots (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.05; Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni test).

3.7. Principal Component Analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to visualize data trends and to detect possible clusters within samples. The first two PCA components (PC1 and PC2) account for 63% of the variance in the overall data sets (Figure 8). PC1, which explained 42% of the total variance, was associated positively with phenolics (GA, TPC, HCAs, and catechin) and DPPH radical scavenging activity. PC2, which accounted for 21% of the total variance, was best explained by Fe and the Fv/Fm ratio on the positive side of the Y-axis and by Pb and MDA (lipid peroxidation) on the negative Y-axis. A clear separation of all the treatments was observed, indicating the strong influence of SA pretreatment and Pb exposure on phenolic metabolism, antioxidant activity, and oxidative stress markers.

Figure 8.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot based on the correlation matrix of physiological and biochemical parameters measured in in vitro C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis shoots pretreated or not with salicylic acid (SA, 100 μM) and exposed either to 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2 or for 7 days. Groups: C, control shoots; C + SA 100, SA-pretreated control shoots; Pb, Pb-exposed shoots; Pb + SA 100, SA-pretreated, Pb-exposed shoots. Abbreviations: Car, carotenoids; Chl, chlorophyll; DNAd, DNA damage; DPPH, DPPH free radical scavenging; FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power; GA, gallic acid; HCAs, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives; MDA, malondialdehyde; TFC, total flavonoid content; TPC, total phenol content.

4. Discussion

4.1. SA Pretreatment Enhances Phenolic Accumulations in Cistus Leaves

In this study, we analyzed the subcellular distribution of phenolics in leaves from SA-treated Cistus shoots using light and electron microscopy. Our results revealed the presence of electron-dense phenolic deposits near the tonoplasts of epidermal and mesophyll cells, frequently forming large oval aggregates using caffeine-fixed leaf samples. Similar vacuolar localization of phenolics has been reported in various plant species, including lupin [48], Brassica napus [49], mung bean [50], bilberry [51], and Fagopyrum spp. callus cultures [52,53]. Nevertheless, phenolics may also accumulate in other plant cell compartments, such as the cell wall matrix [for a review, see [54]]. Caffeine is known to prevent the leakage of phenolics from vacuoles and allow for the visualization of catechin-like compounds [55,56]. Thus, the large phenolic deposits detected in Cistus leaves may be associated, at least in part, with vacuolar flavonoid accumulation.

Interestingly, the observations revealed the presence of non-glandular trichomes on in vitro C. heterophyllus leaves. Species within the genus Cistus typically have both non-glandular and glandular trichomes; however, some species appear to exhibit exclusively glandular trichomes, such as C. populifolius, while others like C. creticus subsp. eriocephalus, display only non-glandular trichomes [57,58]. The occurrence of trichomes in Mediterranean native plants is not unexpected, as they function as protective structures against environmental stressors, including extreme temperatures and ultraviolet radiation [59]. Furthermore, in vitro leaves of Cistus exhibited structural features such as thin cuticles, enlarged and irregular epidermal cells, and an undifferentiated mesophyll, consistent with previous reports on the anatomical adaptations of in vitro cultured plants [60].

4.2. Pretreatment with SA Mitigates Pb-Induced Disturbances in Mineral Uptake and Photosynthesis

Our findings show that 100 μM SA pretreatment substantially reduced Pb accumulation in Cistus shoots while enhancing Mn, K, and Fe contents. This protective effect of SA against Pb uptake has been previously described [21,61,62,63], although the underlying mechanisms remain unresolved. Current evidence points to potential roles for H+/ATPase activity, cell wall remodeling (e.g., pectin-mediated Pb binding), and the secretion of metal-chelating ligands [64,65,66,67]. Beyond limiting Pb accumulation, SA also promotes the uptake of essential nutrients (Mn, K, and Fe), a phenomenon that has been observed but is still not well understood [68]. Recent findings suggest that plant nutritional status is closely linked to the synthesis and accumulation of SA (for a review, see [69,70]). SA modulates nutrient uptake and utilization through its interaction with auxin, ethylene, and other phytohormone signaling pathways [69,70]. Supporting this view, SA biosynthesis-defective mutants, such as Arabidopis pad4, show a weaker response to iron deficiency [71]. Moreover, the application of exogenous SA in A. thaliana induces the expression of YSL1 and YSL3, two genes involved in iron translocation and homeostasis [72]. In addition, SA has also been reported to regulate K+ homeostasis under abiotic stress by reducing K+ loss and enhancing K+ uptake through NADPH oxidase-dependent H2O2 signaling [73]. Although less studied, some works also suggest a role for SA in Mn homeostasis [74]. The selective modulation of nutrient uptake by SA, favoring beneficial elements while restricting toxic ones, highlights its potential as a priming agent to improve plant resilience under heavy metal stress.

Pb toxicity further impaired photosynthesis performance, as evidenced by reduced chlorophyll levels and a decline in the Fv/Fm ratio below the optimal range (0.74–0.85; [47]), corroborating earlier findings [67]. Notably, SA pretreatment restored photochemical efficiency and limited chlorophyll degradation, suggesting the protection of photosystem II from oxidative damage. These results align with previous studies showing that exogenous SA enhances photosynthesis through the preservation of chloroplast membrane integrity, increased chlorophyll content, and the upregulation of photosynthetic enzymes (i.e., rubisco subunits, carbonic anhydrase, and light-harvesting proteins), as well as key enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (i.e., sucrose phosphate synthase, sucrose synthase, and amylases), (for review see [75]).

Transmission electron microscopy images revealed that Pb exposure led to chloroplast deformation and an increase in both the size and number of starch grains, likely reflecting alterations in carbon metabolism and the accumulation of reserve compounds, as previously reported [76]. In contrast, SA-pretreated shoots maintained a more regular chloroplast morphology and lamellar organization under Pb stress. Recent studies suggest that plastoglobuli-associated proteins may play a critical role in maintaining the balance of lipophilic antioxidants, thereby protecting thylakoid membranes from the oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [77]. Collectively, these results demonstrate that SA contributes to the maintenance of mineral homeostasis and photosynthetic integrity under Pb exposure, reinforcing its multifaceted role in enhancing plant resilience to heavy metal stress.

4.3. SA Pretreatment Enhances Pb-Induced Phenolic Accumulation and Antioxidant Protection

Pb stress triggered lipid peroxidation but did not alter H2O2 levels, consistent with the idea that plants maintain steady ROS concentrations to prevent uncontrolled damage while enabling redox signaling [78,79]. The absence of significant H2O2 changes after Pb exposure suggests the activation of efficient detoxification mechanisms, as also reported in SA-pretreated plants under metal stress [21,80,81]. In this study, SA pretreatment significantly enhanced antioxidant defenses by promoting the accumulation of soluble phenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids, (+)-catechin, HCAs, and gallic acid, which showed strong antioxidant and metal-chelating capacities [82]. This accumulation was reflected in increased DPPH and FRAP activities, confirming their protective role against Pb-induced oxidative stress. Indeed, the SA-induced accumulation of phenolic compounds in plants exposed to HMs is widely documented [25]. Beyond modulating antioxidant phenolics, SA also regulates the expression and/or activities of key antioxidant enzymes—including superoxide dismutase, catalase, enzymes of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, and various class III peroxidases—under HM stress [23,25,63], further reinforcing the practical use of SA for improved acclimation to environmental stress [24].

The analysis of biomolecule protection capacity revealed a strong correlation between lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity and total flavonoid content (r > 0.9; p ≤ 0.01; see Supplementary Figure S5). A statistically significant inverse correlation (r < −0.4; p ≤ 0.05) was also identified between TPC and TFC and the induced oxidative damage to DNA in the copper–phenanthroline assay. This finding is consistent with the protective role suggested for phenolics present in Cistus extracts. However, despite the fact that extracts from SA-Pb treatments exhibited the highest levels of phenolic compounds, they did not demonstrate the strongest protective effect against in vitro DNA degradation. In this assay, DNA oxidation is induced by hydroxyl radicals generated through the copper–phenanthroline system, which targets deoxyribose and produces reactive species detectable via the TBARS assay. The continuous cycling of Cu(II) to Cu(I) in the presence of a reducing agent exacerbates oxidative stress by enhancing radical formation. Many bioactive compounds can intensify DNA degradation through this mechanism, which could explain the slight, statistically non-significant, increase in DNA oxidation observed under the combined SA and Pb treatments compared with other conditions. The elevated levels of HCAs, particularly under SA-Pb conditions may contribute to this effect, as certain HCAs have been reported to exhibit prooxidant behavior [83]. Nevertheless, Attaguille et al. [84] reported the DNA-protective effects of aqueous extracts from C. incanus and C. monspeliensis, which were associated with strong superoxide and DPPH scavenging activities and attributed to both monomeric and oligomeric flavonoids. Thus, although our results indicate that SA-induced soluble phenolics may not directly correlate with DNA protection under Pb stress, the potential involvement of Cistus oligomeric phenolics in DNA integrity cannot be excluded.

Flavanols and gallic acid are among the predominant phenolic compounds in Cistus species [85,86], and have been widely recognized for their significant health-promoting properties [87,88]. The observed accumulation of these compounds following SA pretreatment is particularly relevant. Beyond improving Pb tolerance, this response highlights the potential of SA pretreatment to stimulate phenolic biosynthesis, which may have promising implications for phytotherapeutic and industrial applications [89,90,91].

5. Conclusions

Overall, our results demonstrate that SA pretreatment confers a dual protective effect against Pb stress in C. heterophyllus. On the one hand, SA sustains mineral homeostasis by reducing Pb accumulation while promoting the uptake of essential nutrients, which translates into the maintenance of photosynthetic efficiency. This is further evidenced by increased chlorophyll content and the preservation of chloroplast membrane integrity under Pb exposure.

On the other hand, SA enhances antioxidant capacity through the accumulation of phenolic compounds, which effectively limit lipid peroxidation and contribute to ROS detoxification. Taken together, these findings reinforce the role of SA as a priming agent that integrates nutritional, photosynthetic, and antioxidant processes, thereby strengthening plant resilience to Pb stress.

From an applied perspective, SA treatment emerges as a cost-effective strategy to support conservation programs for C. heterophyllus—a critically endangered species—by boosting antioxidant defenses and improving the prospects for successful reintroduction into natural habitats, while also creating new opportunities for the valorization of Cistus phenolics in biotechnological applications.

For this strategy to be useful, however, it must consider the environmental conditions of the area in which it will be applied. The next step is to reintroduce the SA-primed plants into their natural habitat and evaluate how they respond to combined stress and possible facilitating microorganisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122792/s1, Figure S1: Representative photos of Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis shoots grown in vitro on solid DKW medium. Figure S2: Schematic representation of the experimental design followed for growing Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis shoots under Pb exposure. Figure S3: Effect of different concentrations of salicylic acid (SA) on the content of soluble phenolic compounds (TPCs) in in vitro shoots of Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis grown on solid DKW medium. Figure S4: HPLC chromatograms recorded at 280 nm and 310 nm of methanolic extracts of in vitro C. heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis shoots pretreated or not with salicylic acid (SA, 100 μM) and exposed either to 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2 for 7 days. Figure S5: Pearson correlation coefficients among physiological and biochemical parameters measured in in vitro Cistus shoots subjected to salicylic acid (SA, 100 μM) pretreatment or left untreated, followed by exposure to either 100 μM KNO3 (control) or 50 μM Pb(NO3)2 for 7 days.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.C.; methodology, M.A.F. and A.A.C.; formal analysis and investigation, A.L.-O.; resources, M.A.F. and A.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.F.; writing—review and editing, M.A.F. and A.A.C.; visualization, A.L.-O. and M.A.F.; supervision, A.A.C.; project administration, A.A.C.; funding acquisition, M.A.F. and A.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the AGROALNEXT Program, financed by the MCIU with funding from the European Union NextGeneration EU (PRTR-C17.I1) and by Fundación Séneca with funding from the Comunidad Autónoma Región de Murcia (CARM) and by Fundación Séneca-Agencia de Ciencia y Tecnología from Murcia (project 22016/PI/22), via “Ayudas a proyectos para el desarrollo de investigación científica y técnica por grupos competitivos”, included in “Programa Regional de Fomento de la Investigación Científica y Técnica (Plan de Actuación 2022)”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially carried out at the Instituto de Biotecnología Vegetal (Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena). During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Copilot (GPT-5) for English grammar and spelling corrections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| HCAs | Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

References

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.M.; Breed, A.C.; Camargo, A.; Redvers, N.; Breed, M.F. Biodiversity and Human Health: A Scoping Review and Examples of Underrepresented Linkages. Environ. Res. 2024, 246, 118115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of Climate Change on the Future of Biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, M.S.; Din, B.H.; Tan, S.-H.; Zahid, H. Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity Loss: Global Evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurelle, D.; Thomas, S.; Albert, C.; Bally, M.; Bondeau, A.; Boudouresque, C.; Cahill, A.E.; Carlotti, F.; Chenuil, A.; Cramer, W.; et al. Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Adaptation in the Mediterranean. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Colomer, M.J.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.J. La Jara de Cartagena (Cistus heterophyllus). Una Especie En Peligro. Estado Actual de Conocimientos; Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena: Cartagena, Spain, 2018; ISBN 9788416325634. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, C.; Capó, M. First Insular Population of the Critically Endangered Cistus heterophyllus subsp. carthaginensis on Cabrera Archipelago National Park (Balearic Islands, Spain). Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pence, V.C. Evaluating Costs for the in Vitro Propagation and Preservation of Endangered Plants. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2011, 47, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulak, V.; Longboat, S.; Brunet, N.D.; Shukla, M.; Saxena, P. In Vitro Technology in Plant Conservation: Relevance to Biocultural Diversity. Plants 2022, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matkowski, A. Plant in Vitro Culture for the Production of Antioxidants—A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayani, M.; Srivastava, S. Elicitation: A Stimulation of Stress in in Vitro Plant Cell/Tissue Cultures for Enhancement of Secondary Metabolite Production. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 1227–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Firouzabadi, F.N.; Shafeinia, A.; Shirali, M.; Sadr, A.S. De Novo Transcriptome Assembly and Differential Expression Analysis of Catharanthus roseus in Response to Salicylic Acid. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraphaka, H.; Putalun, W. Stimulation of Health-Promoting Triterpenoids Accumulation in Centella asiatica (L.) Urban Leaves Triggered by Postharvest Application of Methyl Jasmonate and Salicylic Acid Elicitors. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 146, 112171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B. Salicylic Acid: An Efficient Elicitor of Secondary Metabolite Production in Plants. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasri, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Karthick, K.; Shin, H.; Choi, S.H.; Ramesh, M. Methyl Jasmonate and Salicylic Acid as Powerful Elicitors for Enhancing the Production of Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants: An Updated Review. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. PCTOC 2023, 153, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, S.M.; López-Orenes, A.; Ferrer, M.A.; Calderón, A.A. Salicylic-Acid-Regulated Antioxidant Capacity Contributes to Growth Improvement of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Cv. Red Balady). Agronomy 2022, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wan, G.; Liang, Z. Accumulation of Salicylic Acid-Induced Phenolic Compounds and Raised Activities of Secondary Metabolic and Antioxidative Enzymes in Salvia miltiorrhiza Cell Culture. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 148, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Tortosa, V.; López-Orenes, A.; Martínez-Pérez, A.; Ferrer, M.A.; Calderón, A.A. Antioxidant Activity and Rosmarinic Acid Changes in Salicylic Acid-Treated Thymus membranaceus Shoots. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Fatma, M.; Per, T.S.; Anjum, N.A.; Khan, N.A. Salicylic Acid-Induced Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Underlying Mechanisms in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Orenes, A.; Martínez-Pérez, A.; Calderón, A.A.; Ferrer, M.A. Pb-Induced Responses in Zygophyllum fabago Plants Are Organ-Dependent and Modulated by Salicylic Acid. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 84, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Able, A.J.; Able, J.A. Priming Crops for the Future: Rewiring Stress Memory. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, G.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Lin, Y.; Guo, B. Salicylic Acid, a Multifaceted Hormone, Combats Abiotic Stresses in Plants. Life 2022, 12, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, Y.M.; Heo, A.Y.; Choi, H.W. Salicylic Acid as a Safe Plant Protector and Growth Regulator. Plant Pathol. J. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Araniti, F.; Bali, A.S.; Shahzad, B.; Tripathi, D.K.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Landi, M. The Role of Salicylic Acid in Plants Exposed to Heavy Metals. Molecules 2020, 25, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Qin, A.; Zain, M.; Mushtaq, Z.; Mehmood, F.; Riaz, L.; Naveed, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, I.; et al. Pb Uptake, Accumulation, and Translocation in Plants: Plant Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Response: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, H.M.; Faz, A.; Arnaldos, R. Heavy Metal Accumulation and Tolerance in Plants from Mine Tailings of the Semiarid Cartagena-La Unión Mining District (SE Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 366, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Praveen, S.; Divte, P.R.; Mitra, R.; Kumar, M.; Gupta, C.K.; Kalidindi, U.; Bansal, R.; Roy, S.; Anand, A.; et al. Metal Tolerance in Plants: Molecular and Physicochemical Interface Determines the “Not so Heavy Effect” of Heavy Metals. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 131957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Orenes, A.; Martínez-Moreno, J.M.; Calderón, A.A.; Ferrer, M.A. Changes in Phenolic Metabolism in Salicylic Acid-Treated Shoots of Cistus heterophyllus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. PCTOC 2013, 113, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Anmol, A.; Kumar, S.; Wani, A.W.; Bakshi, M.; Dhiman, Z. Exploring Phenolic Compounds as Natural Stress Alleviators in Plants- a Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, J.A.; Kuniyuki, A.H. In Vitro Propagation of Paradox Walnut Rootstock. HortScience 1984, 19, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Guidelines for Water Reuse. (EPA/16251R-92/1004); US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Fischer, S.; Kühnlenz, T.; Thieme, M.; Schmidt, H.; Clemens, S. Analysis of Plant Pb Tolerance at Realistic Submicromolar Concentrations Demonstrates the Role of Phytochelatin Synthesis for Pb Detoxification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7552–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uraguchi, S.; Ohshiro, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Tsukioka, H.; Yoneyama, N.; Sato, H.; Hirakawa, M.; Nakamura, R.; Takanezawa, Y.; Kiyono, M. Selection of Agar Reagents for Medium Solidification Is a Critical Factor for Metal(Loid) Sensitivity and Ionomic Profiles of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Orenes, A.; Bueso, M.C.; Conesa, H.; Calderón, A.A.; Ferrer, M.A. Seasonal Ionomic and Metabolic Changes in Aleppo Pines Growing on Mine Tailings under Mediterranean Semi-Arid Climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637–638, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.A.; Cimini, S.; López-Orenes, A.; Calderón, A.A.; De Gara, L. Differential Pb Tolerance in Metallicolous and Non-Metallicolous Zygophyllum fabago Populations Involves the Strengthening of the Antioxidative Pathways. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll Fluorescence—A Practical Guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, A.A.; Almagro, L.; Martínez-Calderón, A.; Ferrer, M.A. Transcriptional Reprogramming in Sound-treated Micro-Tom Plants Inoculated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of Total Carotenoids and Chlorophylls a and b of Leaf Extracts in Different Solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Orenes, A.; Bueso, M.C.; Conesa, H.M.; Calderón, A.A.; Ferrer, M.A. Seasonal Changes in Antioxidative/Oxidative Profile of Mining and Non-Mining Populations of Syrian Beancaper as Determined by Soil Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Orenes, A.; Dias, M.C.; Ferrer, M.Á.; Calderón, A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Correia, C.; Santos, C. Different Mechanisms of the Metalliferous Zygophyllum fabago Shoots and Roots to Cope with Pb Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Gulati, A.; Ravindranath, S.D.; Kumar, V. A Simple and Convenient Method for Analysis of Tea Biochemicals by Reverse Phase HPLC. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergheen, V.S.; Soobrattee, M.A.; Bahorun, T.; Aruoma, O.I. Characterization of the Phenolic Constituents in Mauritian Endemic Plants as Determinants of Their Antioxidant Activities in Vitro. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the Thiobarbituric Acid-Reactive-Substances Assay for Estimating Lipid Peroxidation in Plant Tissues Containing Anthocyanin and Other Interfering Compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, J.M. Hydrogen Peroxide Concentrations in Leaves under Natural Conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C.; Knapp, M.; Institut, B.; Molekularbiologie, I.I.; Karlsruhe, U. How to Correctly Determine the Different Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters and the Chlorophyll Fluorescence Decrease Ratio RFd of Leaves with the PAM Fluorometer. Photosynthetica 2005, 43, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.A.; Pedreño, M.A.; Calderón, A.A.; Muñoz, R.; Ros Barceló, A. Distribution of Isoflavones in Lupin Hypocotyls. Possible Control of Cell Wall Peroxidase Activity Involved in Lignification. Physiol. Plant. 1990, 79, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuras, M. Cytochemical Localization of Phenolic Compounds in Columella Cells of the Root Cap in Seeds of Brassica Napus—Changes in the Localization of Phenolic Compounds during Germination. Ann. Bot. 1999, 84, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafrańska, K.; Glińska, S.; Janas, K.M. Changes in the Nature of Phenolic Deposits after Re-Warming as a Result of Melatonin Pre-Sowing Treatment of Vigna radiata Seeds. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białońska, D.; Zobel, A.M.; Kuraś, M.; Tykarska, T.; Sawicka-Kapusta, K. Phenolic Compounds and Cell Structure in Bilberry Leaves Affected by Emissions from a Zn–Pb Smelter. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 181, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, R.; Pinski, A.; Milewska-Hendel, A.; Sala-Cholewa, K.; Kostecka-Gugała, A.; Petryszak, P.; Nowak, K.; Rojek, M.; Kwasniewska, J.; Betekhtin, A. Comparative Profiling of Phenolic Compounds in Callus Cultures of Fagopyrum spp.: Insights into F. esculentum, F. tataricum, and F. homotropicum. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. PCTOC 2025, 162, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyukova, Y.A. Phenolic Determination in Proembryogenic Cell Complexes of Buckwheat Morphogenic Cell Culture with Osmium Tetroxide, Toluidine Blue O Dye, and Iron Chloride. In Buckwheat: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, C.H. Phenolic-Storing Cells: Keys to Programmed Cell Death and Periderm Formation in Wilt Disease Resistance and in General Defence Responses in Plants? Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2000, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, W.C.; Greenwood, A.D. The Ultrastructure of Phenolic-Storing Cells Fixed with Caffeine. J. Exp. Bot. 1978, 29, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, W.C.; Beckman, C.H. Ultrastructure of the Phenol-Storing Cells in the Roots of Banana. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1974, 4, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülz, P.-G.; Herrmann, T.; Hangst, K. Leaf Trichomes in the Genus Cistus. Flora 1996, 191, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthimiou, D.; Papanikolaou, A.; Falara, V.; Givanoudi, S.; Kostas, S.; Kanellis, A.K. Genus Cistus: A Model for Exploring Labdane-Type Diterpenes’ Biosynthesis and a Natural Source of High Value Products with Biological, Aromatic, and Pharmacological Properties. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, C.; Meng, P.; Tan, G.; Lv, L. Analysis and Review of Trichomes in Plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Rasangam, L.; Selvam, P.; Shekhawat, M.S. Micro-morpho-anatomical Mechanisms Involve in Epiphytic Adaptation of Micropropagated Plants of Vanda tessellata (Roxb.) Hook. Ex, G. Don. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2021, 84, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.F.; Hou, J.; Qian, J. Effects of Pb Stress on Nutrient Uptake and Secondary Metabolism in Submerged Macrophyte Vallisneria natans. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh, R.; Jamei, R.; Rahmani, F. Pre- Sowing Seed Treatment with Salicylic Acid and Sodium Hydrosulfide Confers Pb Toxicity Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.B.; Chadar, H.; Wani, A.H.; Singh, S.; Upadhyay, N. Salicylic Acid to Decrease Plant Stress. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesłowska, M. The Cell Wall in Plant Cell Response to Trace Metals: Polysaccharide Remodeling and Its Role in Defense Strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S. Toxic Metal Accumulation, Responses to Exposure and Mechanisms of Tolerance in Plants. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrut, B.; Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Winterton, P.; Pinelli, E. Lead Uptake, Toxicity, and Detoxification in Plants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 213, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prasad, M.N.V. Plant-Lead Interactions: Transport, Toxicity, Tolerance, and Detoxification Mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 166, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ugurlar, F.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmad, P. Salicylic Acid Interacts with Other Plant Growth Regulators and Signal Molecules in Response to Stressful Environments in Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano-Ramírez, V.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Cross-Talk between Iron Deficiency Response and Defense Establishment in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, P.; Velozo, S.; Herrera-Vásquez, A. Salicylic Acid Accumulation: Emerging Molecular Players and Novel Perspectives on Plant Development and Nutrition. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 1950–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Sun, T.; Wang, H. Involvement of Endogenous Salicylic Acid in Iron-Deficiency Responses in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4179–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chien, W.-F.; Lin, N.-C.; Yeh, K.-C. Alternative Functions of Arabidopsis YELLOW STRIPE-LIKE3: From Metal Translocation to Pathogen Defense. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Song, L.; Zeng, L.; Guo, Z.; Ma, D.; Wei, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H. NADPH Oxidase-dependent H2O2 Production Mediates Salicylic Acid-induced Salt Tolerance in Mangrove Plant Kandelia obovata by Regulating Na+/K+ and Redox Homeostasis. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pan, J.; Najeeb, U.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Huang, Q.; Lu, H.; Xu, L.; Shi, B.; Zhou, W. Promotive Role of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid or Salicylic Acid Combined with Citric Acid on Sunflower Growth by Regulating Manganese Absorption. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, Y.; Sami, F.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salicylic Acid in Relation to Other Phytohormones in Plant: A Study towards Physiology and Signal Transduction under Challenging Environment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 175, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khattabi, O.; Lamwati, Y.; Henkrar, F.; Collin, B.; Levard, C.; Colin, F.; Smouni, A.; Fahr, M. Lead-Induced Changes in Plant Cell Ultrastructure: An Overview. BioMetals 2025, 38, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S. Get the Ball Rolling: Update and Perspective on the Role of Chloroplast Plastoglobule-Associated Proteins under Abiotic Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 4735–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox Regulation in Photosynthetic Organisms: Signaling, Acclimation, and Practical Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 861–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. Intracellular Redox Compartmentation and ROS-Related Communication in Regulation and Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, L.P.; Maslenkova, L.T.; Yordanova, R.Y.; Ivanova, A.P.; Krantev, A.P.; Szalai, G.; Janda, T. Exogenous Treatment with Salicylic Acid Attenuates Cadmium Toxicity in Pea Seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantev, A.; Yordanova, R.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Popova, L. Treatment with Salicylic Acid Decreases the Effect of Cadmium on Photosynthesis in Maize Plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.H.; Azmi, A.S.; Hadi, S.M. Prooxidant DNA Breakage Induced by Caffeic Acid in Human Peripheral Lymphocytes: Involvement of Endogenous Copper and a Putative Mechanism for Anticancer Properties. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007, 218, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaguile, G.; Russo, A.; Campisi, A.; Savoca, F.; Acquaviva, R.; Ragusa, N.; Vanella, A. Antioxidant Activity and Protective Effect on DNA Cleavage of Extracts from Cistus incanus L. and Cistus monspeliensis L. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2000, 16, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomponio, R.; Gotti, R.; Santagati, N.A.; Cavrini, V. Analysis of Catechins in Extracts of Cistus Species by Microemulsion Electrokinetic Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 990, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santagati, N.A.; Salerno, L.; Attaguile, G.; Savoca, F.; Ronsisvalle, G. Simultaneous Determination of Catechins, Rutin, and Gallic Acid in Cistus Species Extracts by HPLC with Diode Array Detection. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2008, 46, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2020, 25, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Liñán-Atero, R.; Tarahi, M.; Christodoulou, M.C.; Aghababaei, F. The Potential Health Benefits of Gallic Acid: Therapeutic and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayah, K.; Chemlal, L.; Marmouzi, I.; El Jemli, M.; Cherrah, Y.; Faouzi, M.E.A. In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Activities of Cistus salviifolius (L.) and Cistus monspeliensis (L.) Aqueous Extracts. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastino, P.M.; Marchetti, M.; Costa, J.; Juliano, C.; Usai, M. Analytical Profiling of Phenolic Compounds in Extracts of Three Cistus Species from Sardinia and Their Potential Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Hoian, U.; Czop, M.; Strzępek-Gomółka, M.; Antosiewicz, B. Characterization of Cistus incanus L. and Cistus ladanifer L. Extracts as Potential Multifunctional Antioxidant Ingredients for Skin Protecting Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).