Autonomous Navigation for Efficient and Precise Turf Weeding Using Wheeled Unmanned Ground Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Formulation

2.1.1. Problem Description

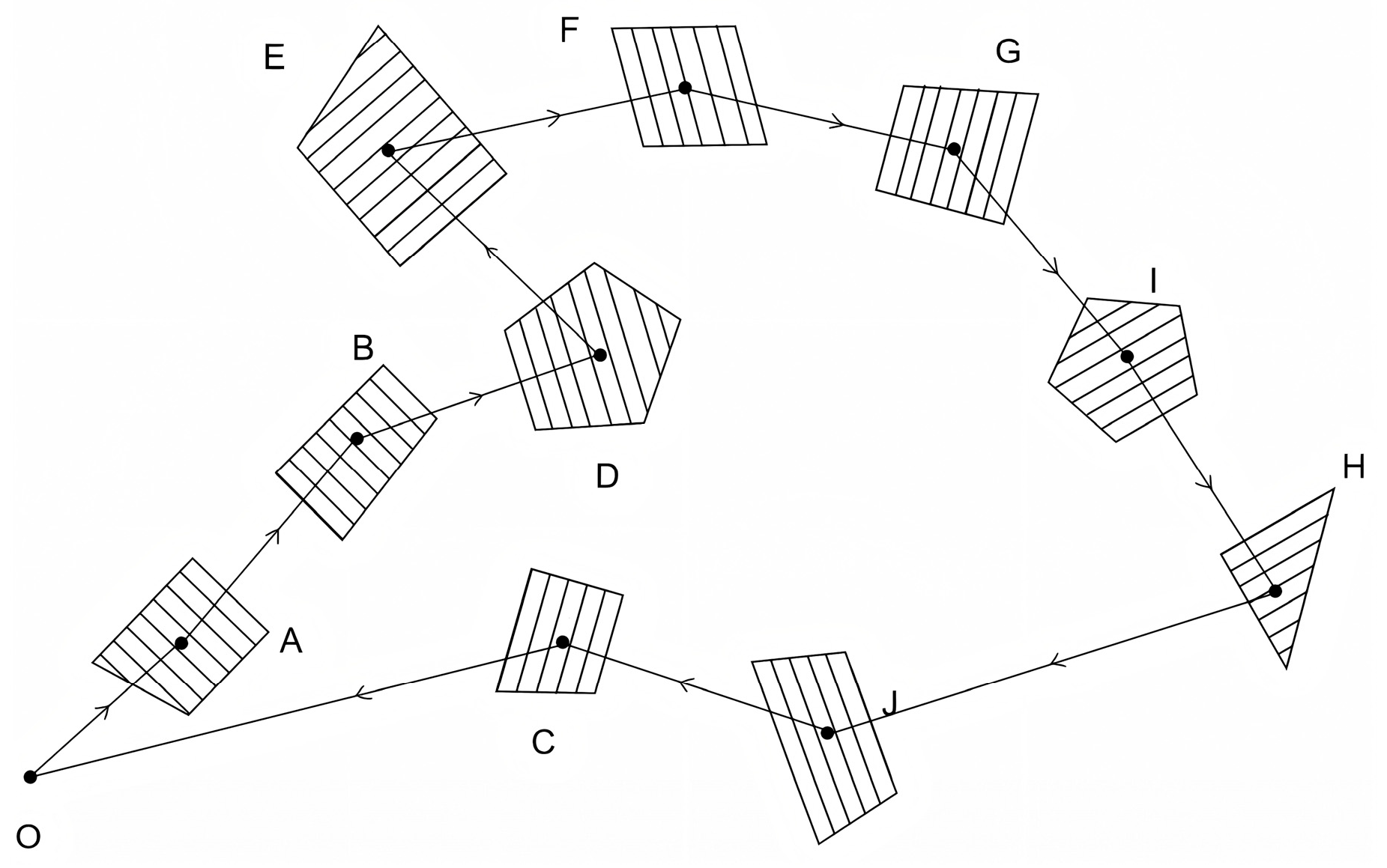

2.1.2. Traveling Salesman Problem and Genetic Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Genetic Algorithm | |

| Input: | |

| Output: | |

| 1 | Initialization population: ⊳ Generate popSize |

| 2 | for do |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | while do |

| 6 | ⊳ |

| 7 | if then |

| 8 | ⊳ Generate offspring individuals |

| 9 | else |

| 10 | |

| 11 | end if |

| 12 | if then |

| 13 | ⊳ Perform mutation on the individual |

| 14 | end if |

| 15 | ⊳ |

| 16 | end while |

| 17 | ⊳ Update current population |

| 18 | |

| 19 | end for |

| 20 | |

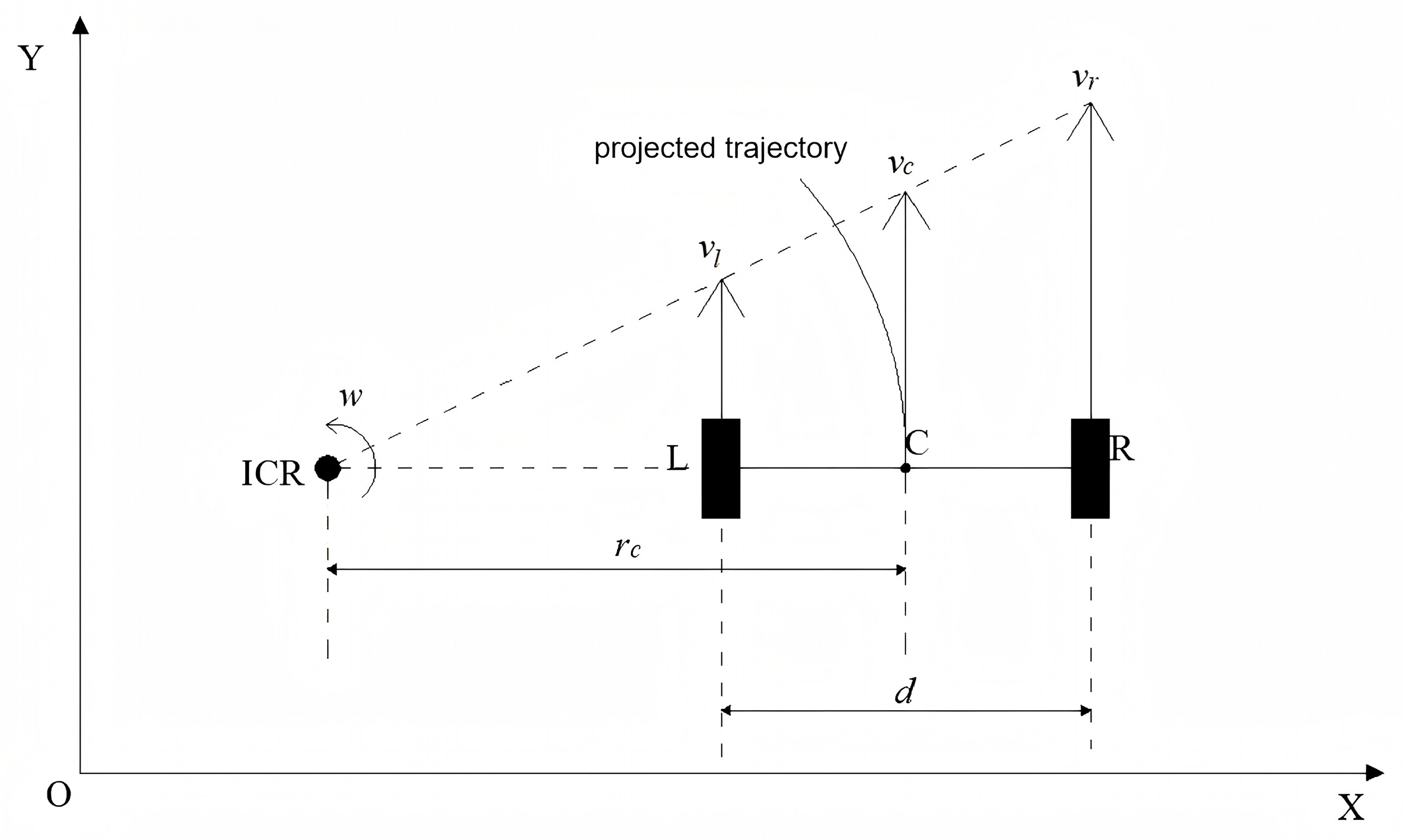

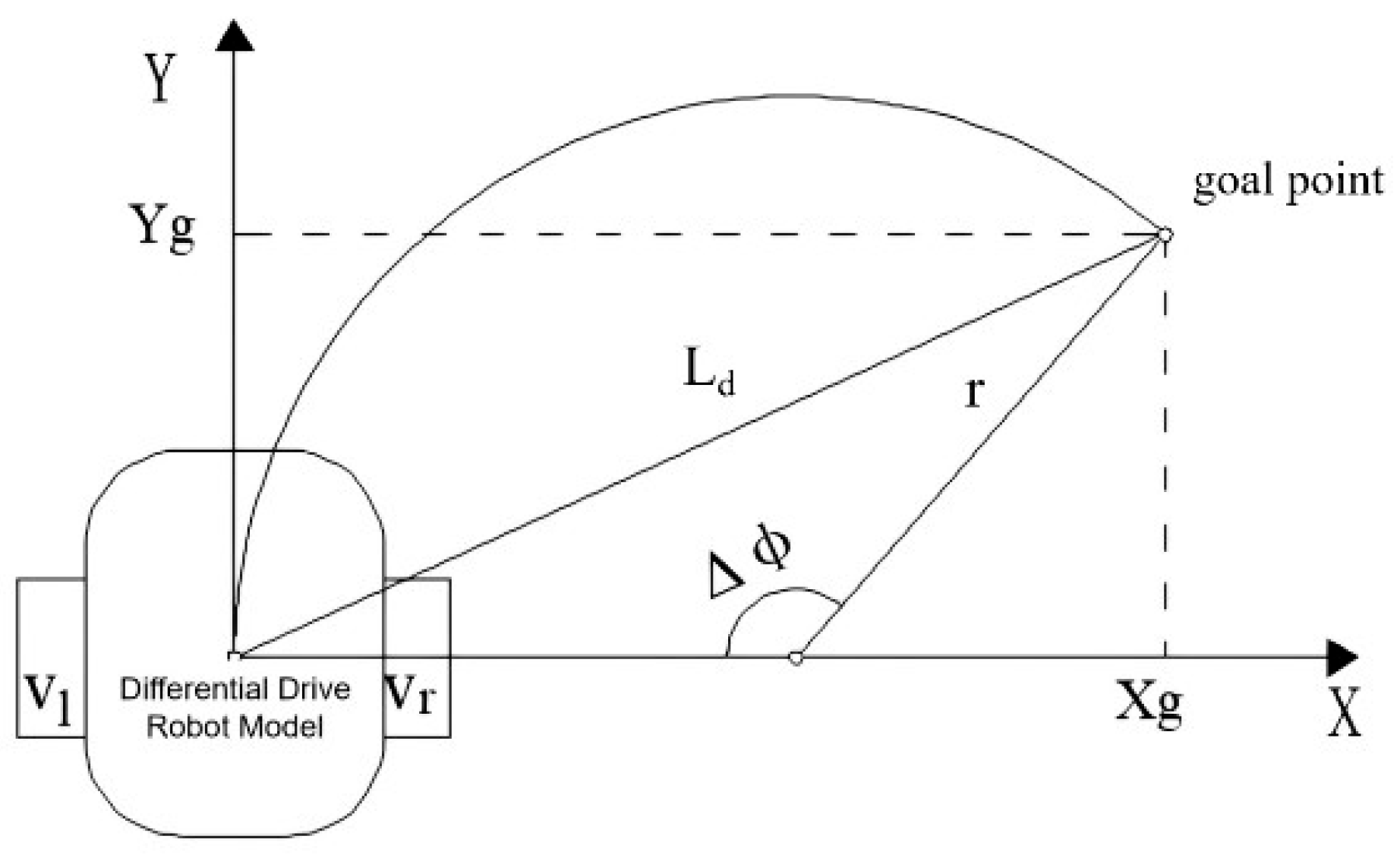

2.1.3. Pure Pursuit

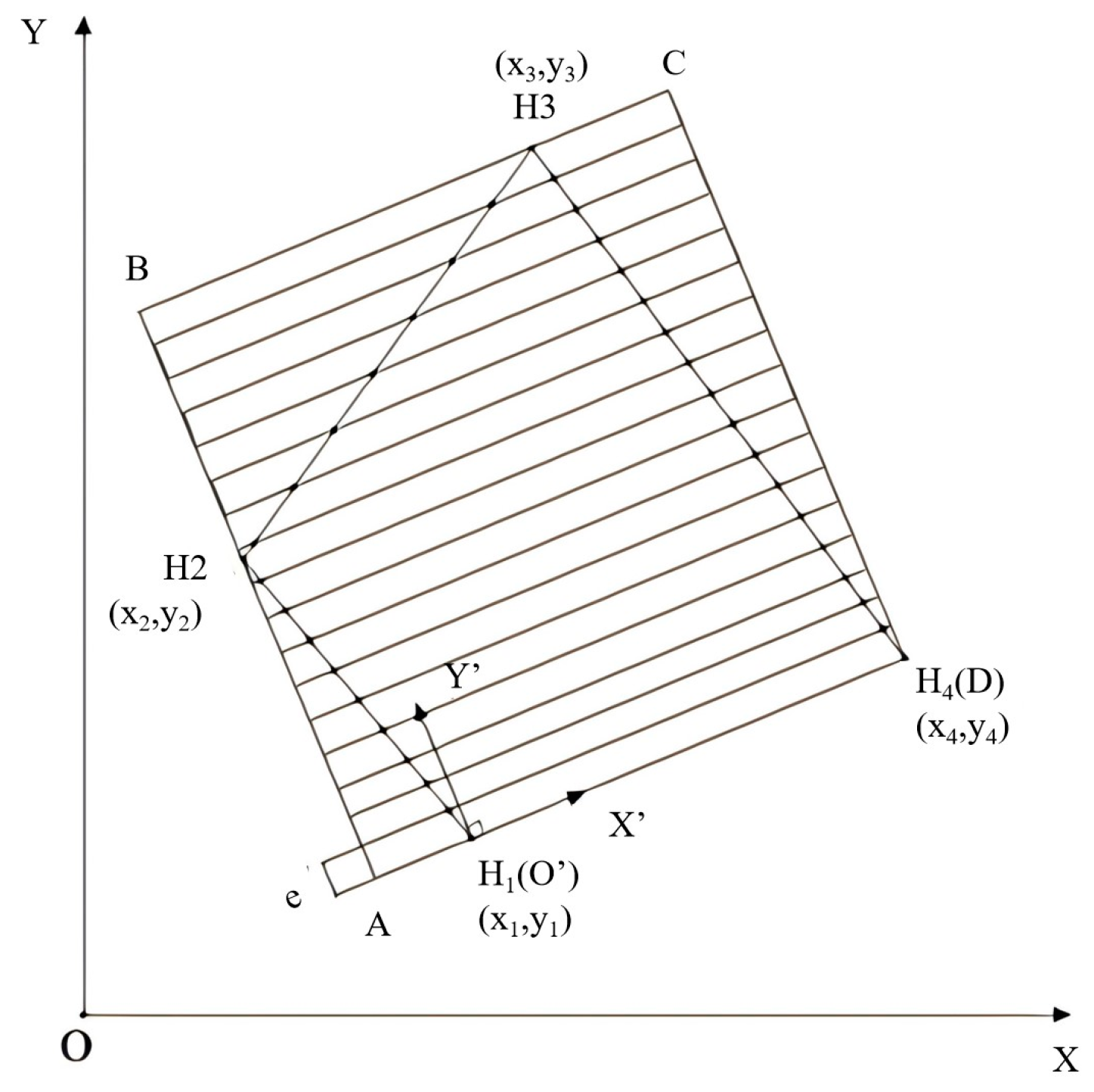

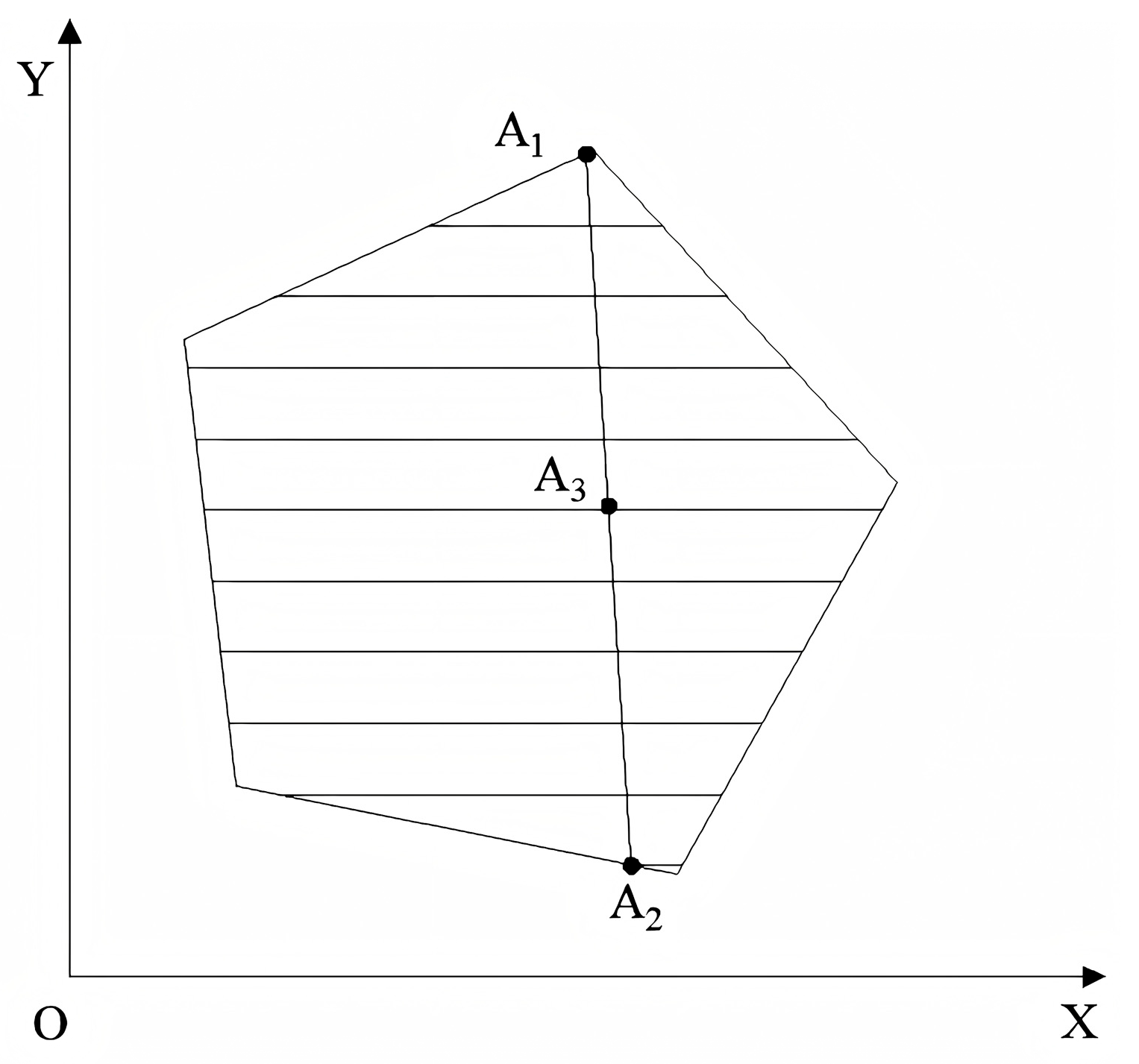

2.2. Efficient Weeding Path Planning

2.2.1. Complete Coverage of a Single Sub-Region

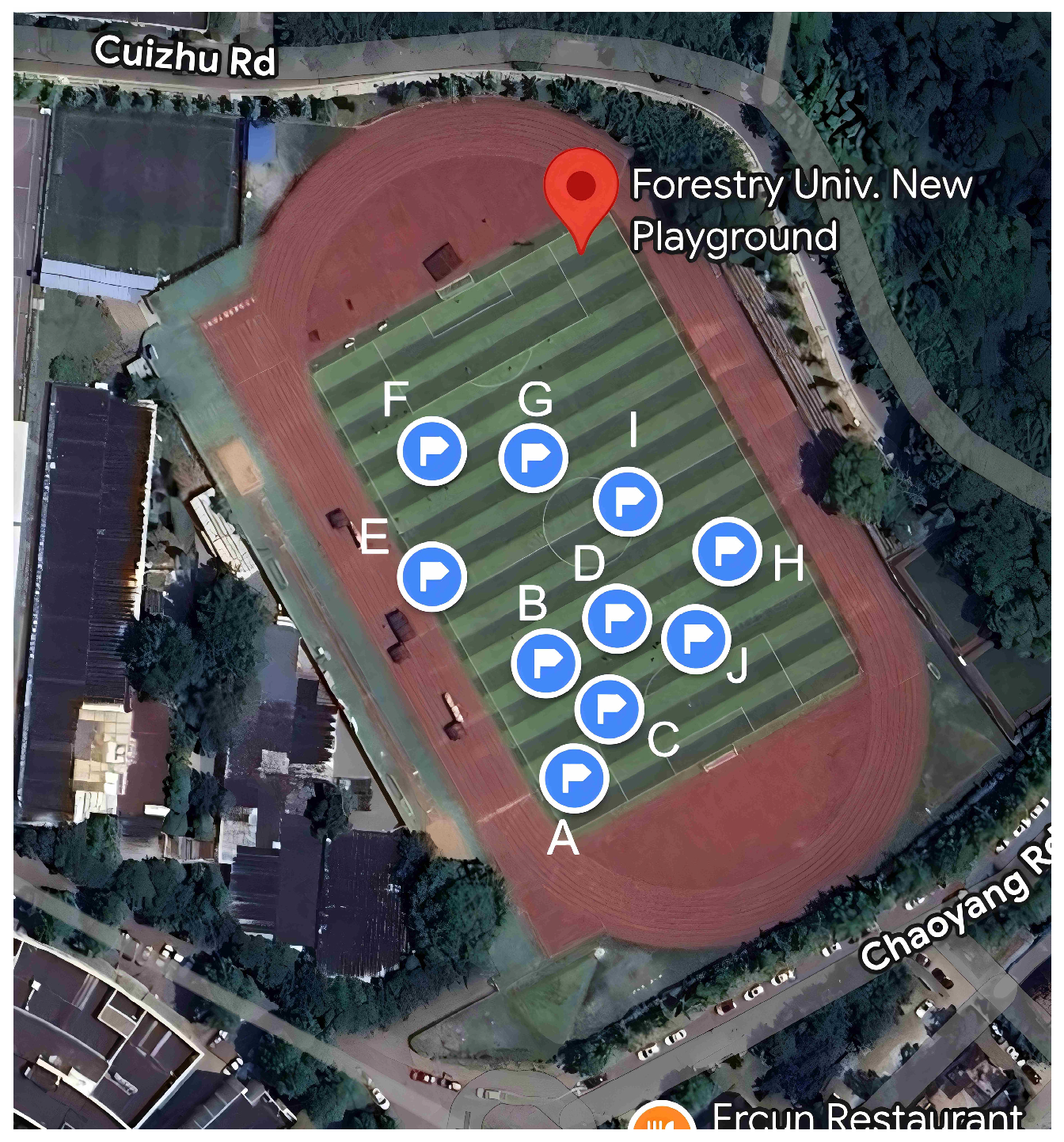

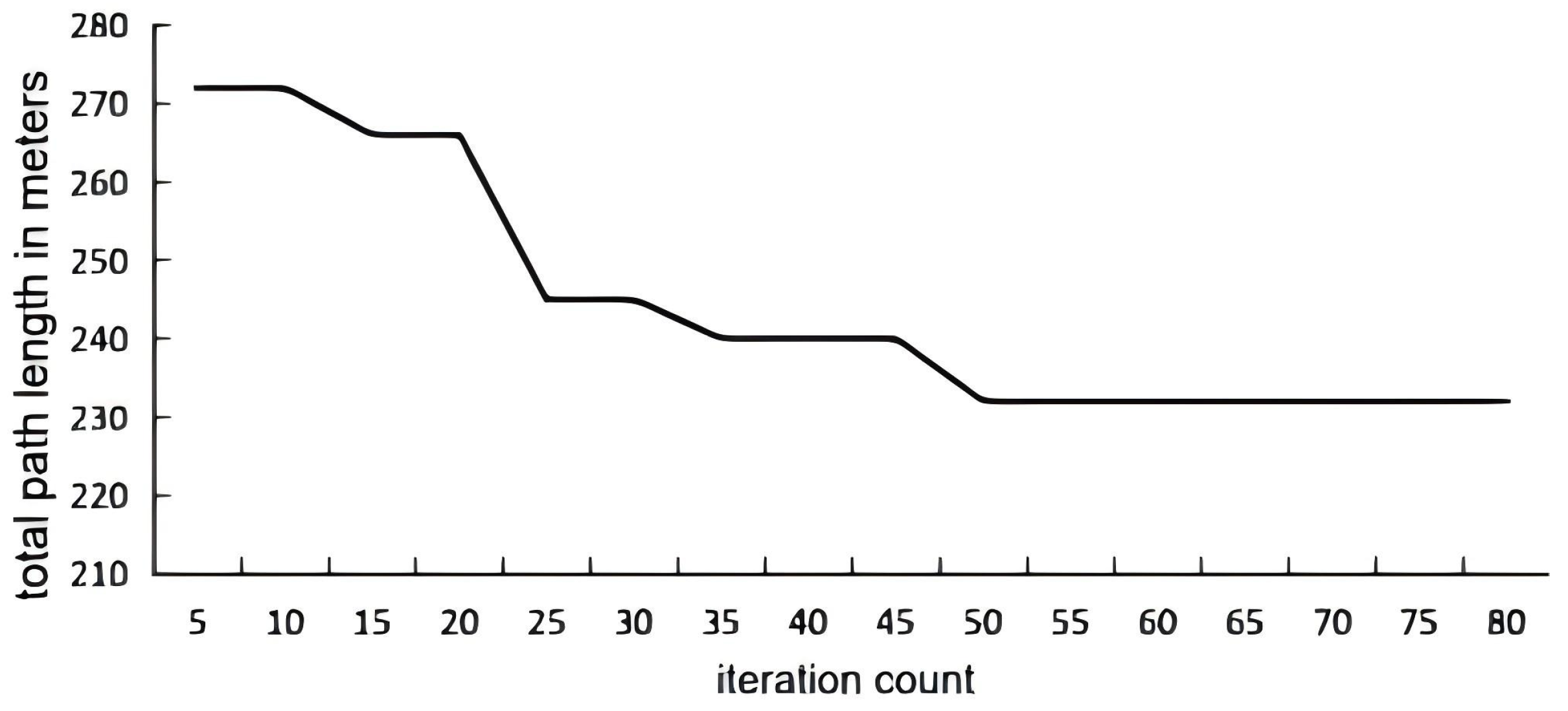

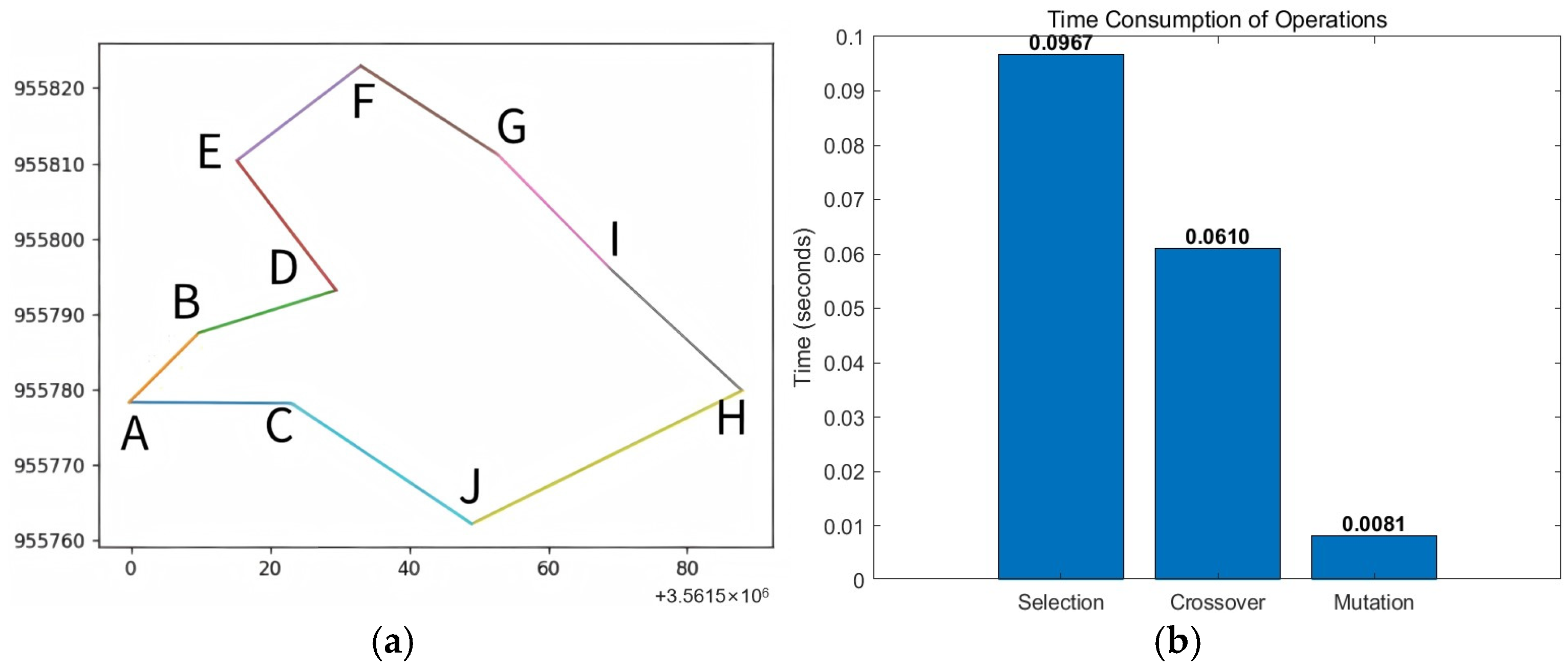

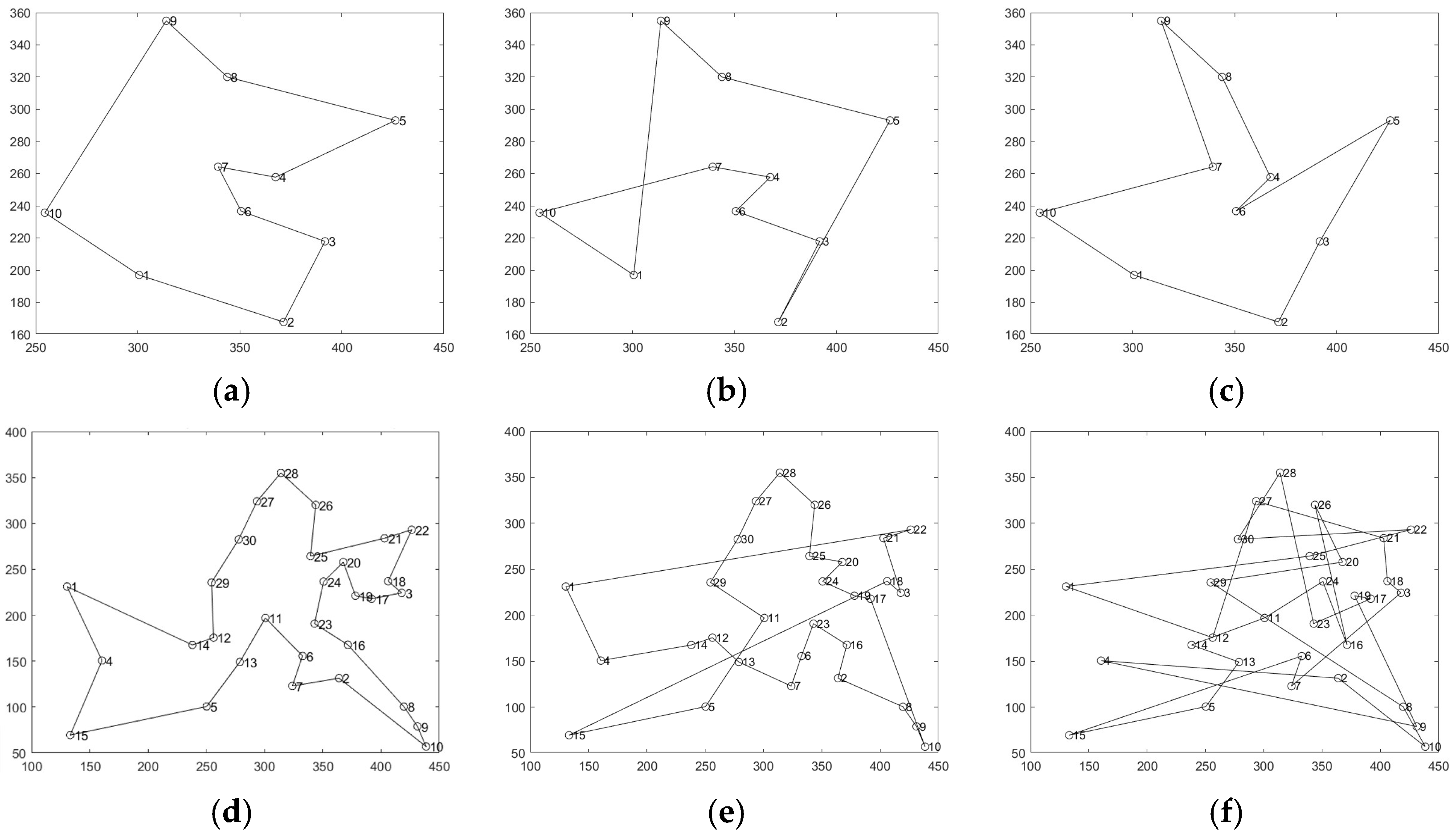

2.2.2. Sequence Planning for Multiple Subregions

- (1)

- Population Initialization: In the genetic algorithm, the traversal order of subregions serves as the encoding, with path length defined as the objective function. Due to the use of integer encoding, each chromosome undergoes a validity check to ensure the absence of duplicate nodes. Subsequently, the population (i.e., the set of chromosomes) is initialized as the initial solution. The chromosome count is set to , where represents the number of subregions.

- (2)

- Selection: This paper employs a roulette wheel selection strategy to determine the probability of an individual being selected for the next generation in the genetic selection process. Assuming there are a total of individuals, with the fitness value of the individual denoted as , the probability of the individual being selected is given by

- (3)

- Crossover: The crossover probability is critical to algorithm performance. If its value is too low, the algorithm may become trapped in local optima. Conversely, if the value is too high, convergence slows, resulting in an increased number of iterations. To achieve a balanced solution, we propose an adaptive crossover probability function defined as follows:

- (4)

- Mutation: In traditional genetic algorithms, the performance of mutation operations largely depends on the setting of the mutation probability . However, is typically set quite low, which increases the likelihood of the algorithm becoming trapped in local optima. This paper proposes an adaptive mutation probability function that adjusts based on an individual’s fitness value: when an individual’s fitness is poor, the mutation probability is increased, and it is gradually decreased throughout the algorithm’s iterations, thereby enhancing optimization efficiency. The adaptive mutation probability function realizes the adaptive adjustment of by

2.3. Precise Path Following

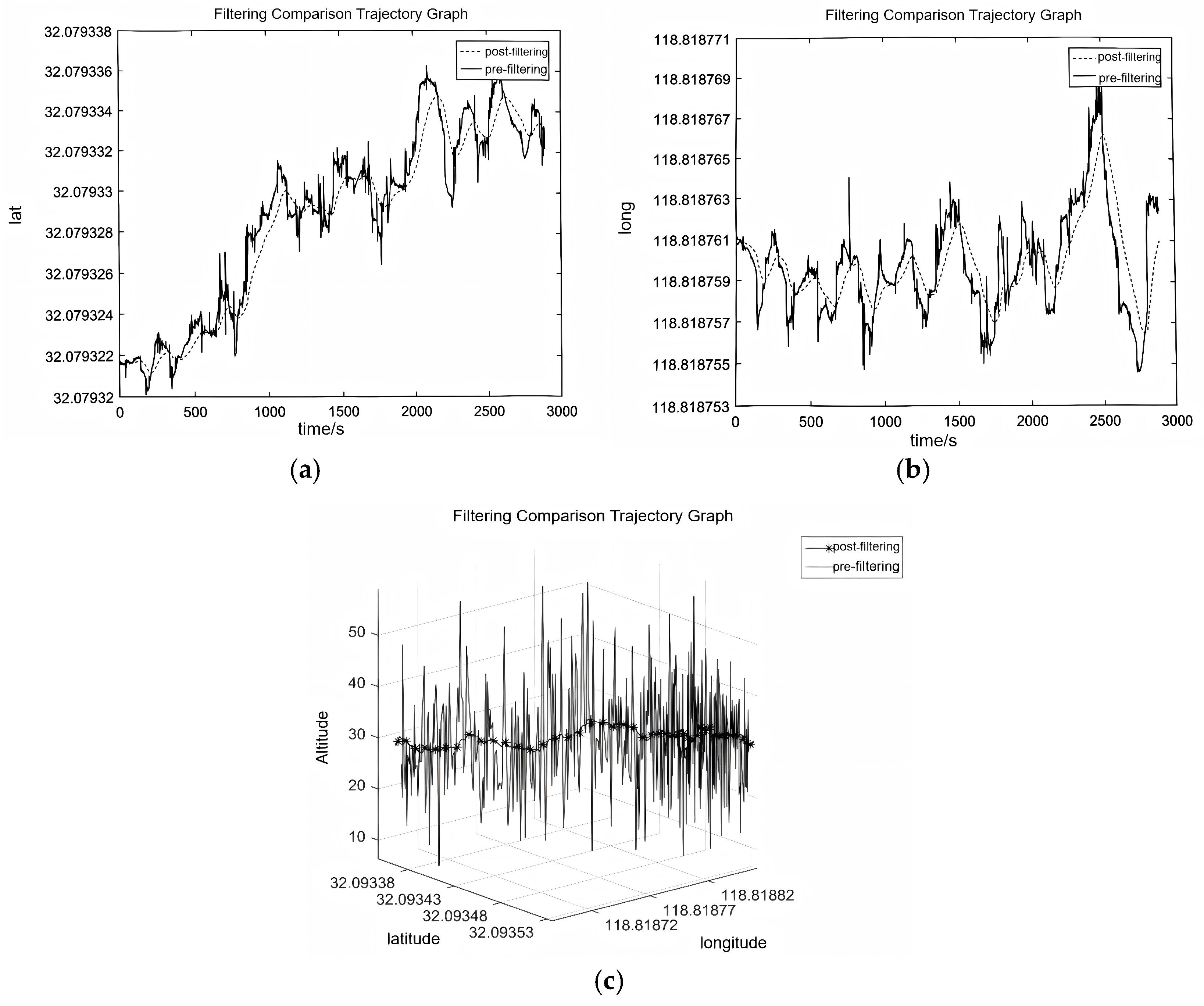

2.3.1. Sensor Fusion for Improved Localization

2.3.2. Dynamic Pure Pursuit Algorithm for Accurate Path Following

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results for Path Planning

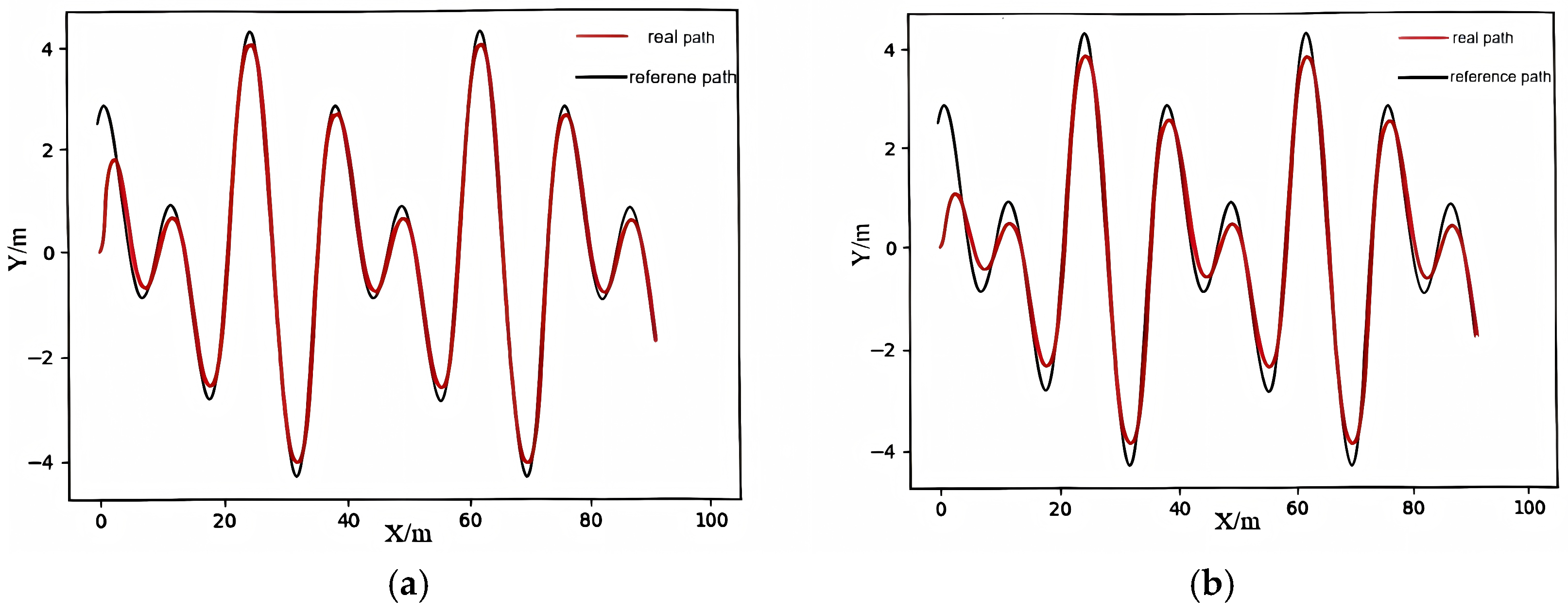

3.2. Experimental Results for Path Following

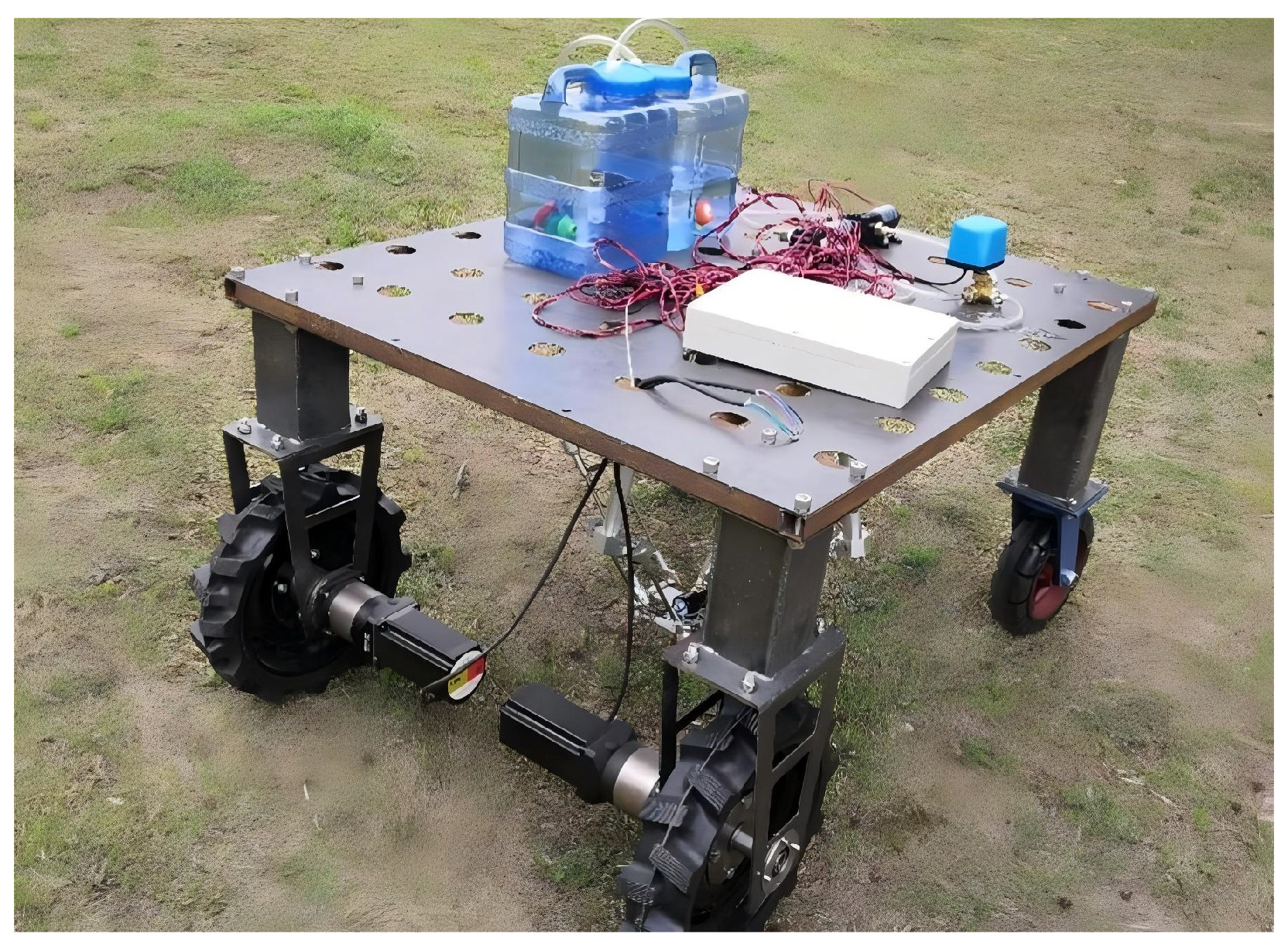

3.2.1. Hardware Development

3.2.2. Sensor Fusion

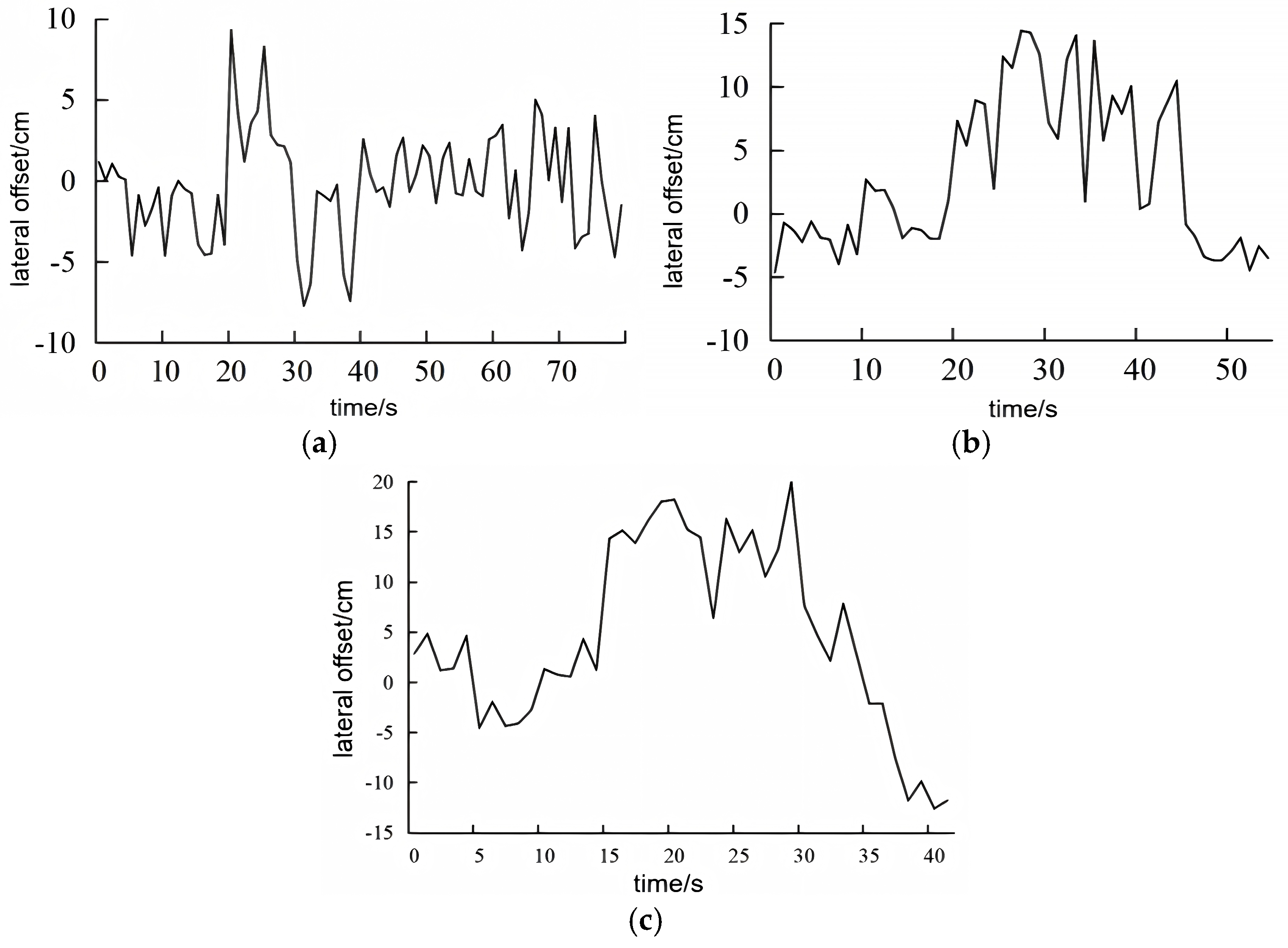

3.2.3. Dynamic Pure Pursuit

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TSP | Traveling Salesman Problem |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| RRT | Rapidly Exploring Random Trees |

| APF | Artificial Potential Field |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| KF | Kalman filter |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| UGV | Unmanned Ground Vehicle |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| IIC | Inter-Integrated Circuit |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

| NSR | Noise Suppression Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| RA | Random Algorithm |

References

- Jin, X.; Bagavathiannan, M.; McCullough, P.E.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. A deep learning-based method for classification, detection, and localization of weeds in turfgrass. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 4809–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshipour, A.; Jafari, A. Evaluation of support vector machine and artificial neural networks in weed detection using shape features. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 145, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, H.; Kong, X.; Han, K.; Lei, J.; Zu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. Deep learning-based weed detection for precision herbicide application in turf. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 3597–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sharpe, S.M.; Schumann, A.W.; Boyd, N.S. Deep learning for image-based weed detection in turfgrass. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 104, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; McCullough, P.E.; Liu, T.; Yang, D.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. A smart sprayer for weed control in bermudagrass turf based on the herbicide weed control spectrum. Crop Prot. 2023, 170, 106270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bai, Y.; Diao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, B. Row detection BASED navigation and guidance for agricultural robots and autonomous vehicles in row-crop fields: Methods and applications. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.S.; Strickland, M.; Nunes, L.R.T.; Magni, S.; Fontani, M.; Fontanelli, M.; Volterrani, M. Robotic mowing technology in turfgrass management: Past, present, and future. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.M.; Sohel, F.; Diepeveen, D.; Laga, H.; Jones, M.G. A survey of deep learning techniques for weed detection from images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Han, K.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. Detection and coverage estimation of purple nutsedge in turf with image classification neural networks. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3504–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-H.; Slaughter, D.C.; Fennimore, S.A. Non-destructive evaluation of photostability of crop signaling compounds and dose effects on celery vigor for precision plant identification using computer vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, Q.; Bu, S.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L. Research on Intelligent Vehicle Path Planning Based on Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 5910503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Han, B.; Chen, Y.; Liang, G.; Zheng, K. Collision-free path planning method for robots based on an improved rapidly-exploring random tree algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, D.; Wei, Z.; Dai, J.; Pan, H. An improved A* algorithm for the industrial robot path planning with high success rate and short length. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 106, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Yun, C.; Gang, M.; Han, X. An entry-exit path planner for an autonomous tractor in a paddy field. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 191, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, B.; Lyu, W. Improved artificial potential field method applied for AUV path planning. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6523158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Qi, L.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, T. Path planning method with improved artificial potential field—A reinforcement learning perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 135513–135523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galceran, E.; Carreras, M. A survey on coverage path planning for robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1258–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Sun, M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, S. A multi-robot coverage path planning algorithm for the environment with multiple land cover types. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 198101–198117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Dai, C.; Gong, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, J.; Gu, X.D.; Wang, C.C. Energy-efficient coverage path planning for general terrain surfaces. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2584–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, A.K.; Mohan, R.E.; Ramalingam, B.; Le, A.V.; Veerajagadeshwar, P.; Tiwari, K.; Ilyas, M. Complete coverage path planning using reinforcement learning for tetromino based cleaning and maintenance robot. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Li, P.; Wang, T.; Miao, J.C.; Tian, J.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tan, J.; Wang, Z.J. Multi-area collision-free path planning and efficient task scheduling optimization for autonomous agricultural robots. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhao, J.-S.; Misyurin, S.Y.; Martins, D. Precision-Driven Multi-Target Path Planning and Fine Position Error Estimation on a Dual-Movement-Mode Mobile Robot Using a Three-Parameter Error Model. Sensors 2023, 23, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yu, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Shi, Y. Autonomous navigation system for greenhouse tomato picking robots based on laser SLAM. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 100, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J. Fuzzy Control of Self-Balancing, Two-Wheel-Driven, SLAM-Based, Unmanned System for Agriculture 4.0 Applications. Machines 2023, 11, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, Y.; Saito, H.; Tamaki, K.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Taniwaki, K. An autonomous rice transplanter guided by global positioning system and inertial measurement unit. J. Field Robot. 2009, 26, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.; Orjuela, R.; Spisser, M.; Basset, M. Positioning and attitude determination for precision agriculture robots based on IMU and two RTK GPSs sensor fusion. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.a. Real-time localization and mapping utilizing multi-sensor fusion and visual–IMU–wheel odometry for agricultural robots in unstructured, dynamic and GPS-denied greenhouse environments. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, R.; Chen, B.; Li, H.; Yin, Y. Agricultural machinery GNSS/IMU-integrated navigation based on fuzzy adaptive finite impulse response Kalman filtering algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 191, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, W. Complex trajectory tracking using PID control for autonomous driving. Int. J. Intell. Transp. 2020, 18, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshayedi, A.J.; Abbasi, A.; Liao, L.; Li, S. Path planning and trajectroy tracking of a mobile robot using bio-inspired optimization algorithms and PID control. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Virtual Environments for Measurement Systems and Applications (CIVEMSA), Tianjin, China, 14–16 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qun, R. Intelligent control technology of agricultural greenhouse operation robot based on fuzzy PID path tracking algorithm. INMATEH-Agric. Eng. 2020, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Bu, S.; Yang, J. Smart vehicle path planning based on modified PRM algorithm. Sensors 2022, 22, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.; Hussein, M.; Mohamad, M.B. A review of some pure-pursuit based path tracking techniques for control of autonomous vehicle. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2016, 135, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Li, Q.; Yang, J. An Optimal Hierarchical Control Strategy for 4WS-4WD Vehicles Using Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. Machines 2024, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Q.; Cheng, S.; Qi, J.; Xu, L.; Chen, L. An optimal goal point determination algorithm for automatic navigation of agricultural machinery: Improving the tracking accuracy of the Pure Pursuit algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 194, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldurai, L.; Madhubala, T.; Rajalakshmi, R. A study on genetic algorithm and its applications. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lambora, A.; Gupta, K.; Chopra, K. Genetic algorithm-A literature review. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COMITCon), Faridabad, India, 14–16 February 2019; pp. 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Evolutionary algorithms and neural networks. Stud. Comput. Intell. 2019, 780, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Coverage path planning method for agricultural spraying UAV in arbitrary polygon area. Aerospace 2023, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour Arab, D.; Spisser, M.; Essert, C. Complete coverage path planning for wheeled agricultural robots. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1460–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yao, S.; Li, B.; Song, A.; Jia, Y.; Mitani, J. A geometric folding pattern for robot coverage path planning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Collaborative path planning and task allocation for multiple agricultural machines. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höffmann, M.; Patel, S.; Büskens, C. Optimal guidance track generation for precision agriculture: A review of coverage path planning techniques. J. Field Robot. 2024, 41, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, G. IMU data and GPS position information direct fusion based on LSTM. Sensors 2021, 21, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.H.; Gankhuyag, G.; Chong, K.T. Navigation system heading and position accuracy improvement through GPS and INS data fusion. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 7942963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataija, M.; Pogarčić, M.; Pogarčić, I. Helmert transformation of reference coordinating systems for geodesic purposes in local frames. Procedia Eng. 2014, 69, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chakraborty, S.; Elangovan, D.; Govindarajan, P.L.; ELnaggar, M.F.; Alrashed, M.M.; Kamel, S. A comprehensive review of path planning for agricultural ground robots. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coordinate Point Number | Latitude and Longitude Coordinates | Corresponding Gaussian Plane Coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| A | 118.818791, 32.079066 | 3561501.12, 955778.31 |

| B | 118.819518, 32.079069 | 3561509.69, 955789.95 |

| C | 118.819516, 32.078846 | 3561521.90, 955778.59 |

| D | 118.818791, 32.079946 | 3561524.59, 955791.94 |

| E | 118.825709, 32.085238 | 3561518.14, 955809.36 |

| F | 118.825735, 32.085575 | 3561538.42, 955823.30 |

| G | 118.825421, 32.085903 | 3561555.40, 955811.51 |

| H | 118.825582, 32.085727 | 3561585.82, 955776.24 |

| I | 118.825850, 32.085393 | 3561562.59, 955795.72 |

| J | 118.825216, 32.085561 | 3561550.53, 955762.80 |

| Algorithm Type | Shortest Length (10 Nodes)/m | Execution Time (10 Nodes)/s | Shortest Length (30 Nodes)/m | Execution Time (30 Nodes)/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA | 630.82 | 0.17876 | 1736.4 | 20.18 |

| KNN | 733.10 | 0.00819 | 2049.0 | 0.00873 |

| RA | 702.87 | 0.02751 | 3399.7 | 0.03351 |

| Vehicle Speed/(m⋅s−1) | Collection Frequency/Piece | Minimum Tolerance/cm | Maximum Tolerance/cm | Root Mean Square Error/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 | 79 | 0.01 | 7.22 | 0.36 |

| 0.8 | 54 | 0.36 | 14.42 | 0.81 |

| 1.0 | 41 | 0.55 | 16.95 | 1.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Autonomous Navigation for Efficient and Precise Turf Weeding Using Wheeled Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122793

Yu L, Li X, Chen J, Chen Y. Autonomous Navigation for Efficient and Precise Turf Weeding Using Wheeled Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122793

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Linfeng, Xin Li, Jun Chen, and Yong Chen. 2025. "Autonomous Navigation for Efficient and Precise Turf Weeding Using Wheeled Unmanned Ground Vehicles" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122793

APA StyleYu, L., Li, X., Chen, J., & Chen, Y. (2025). Autonomous Navigation for Efficient and Precise Turf Weeding Using Wheeled Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Agronomy, 15(12), 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122793