A Novel Semi-Hydroponic Root Observation System Combined with Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation for Root Phenotyping

Abstract

1. Introduction

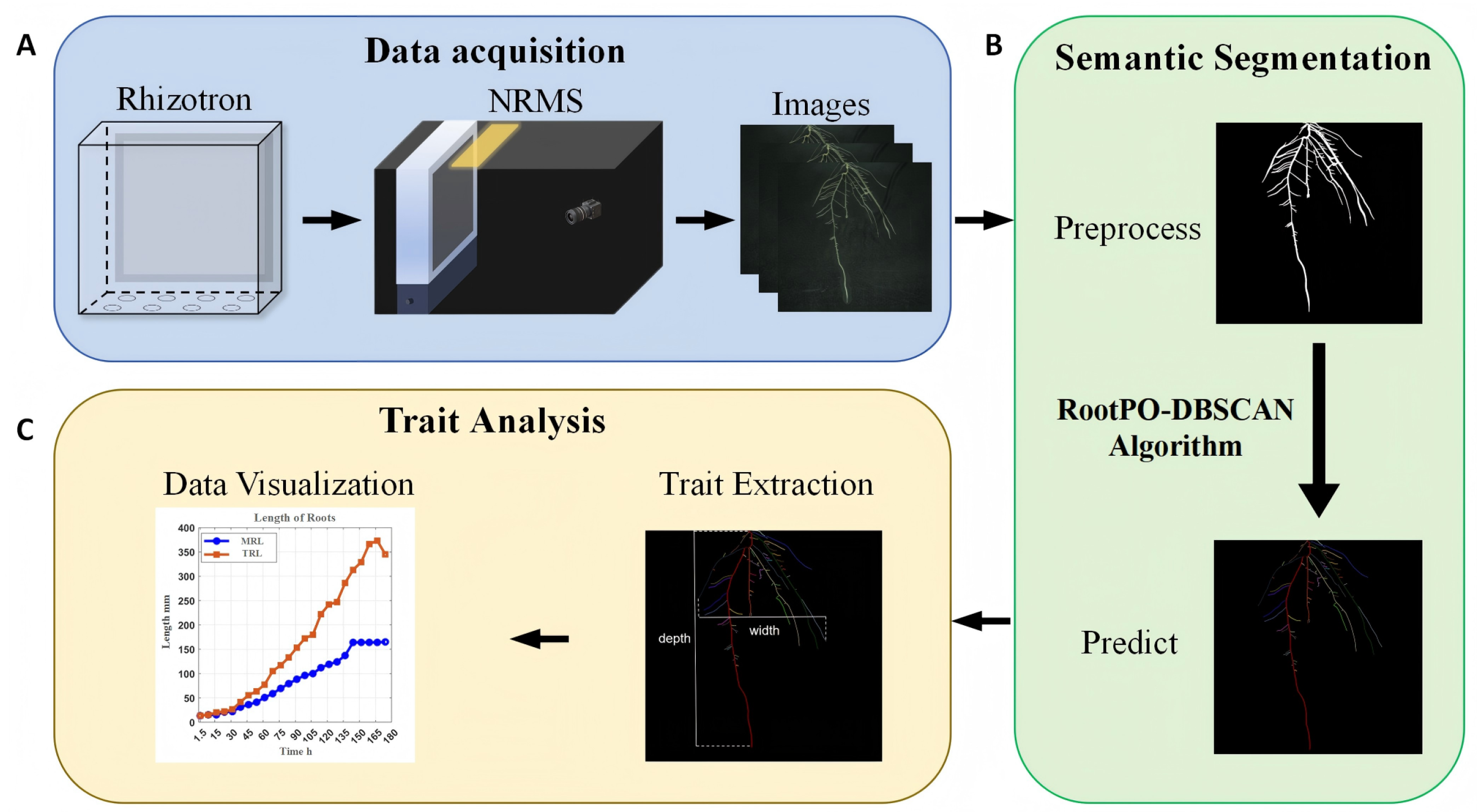

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation Method

- It physically separates the roots from the soil, which have a similar color, thereby significantly improving root image contrast and clarity.

- The permeable membrane, together with the capillary action of the black cloth, facilitates continuous water and nutrient supply from the outer substrate while preventing root penetration into the soil, thus maintaining observation quality.

- The incorporation of coconut coir into the soil mixture enhances substrate aeration and looseness, promoting natural root extension and reducing overall weight.

- The non-destructive nature of the setup allows for the dynamic quantification of root phenotypic parameters, offering a reliable platform for studying root development patterns.

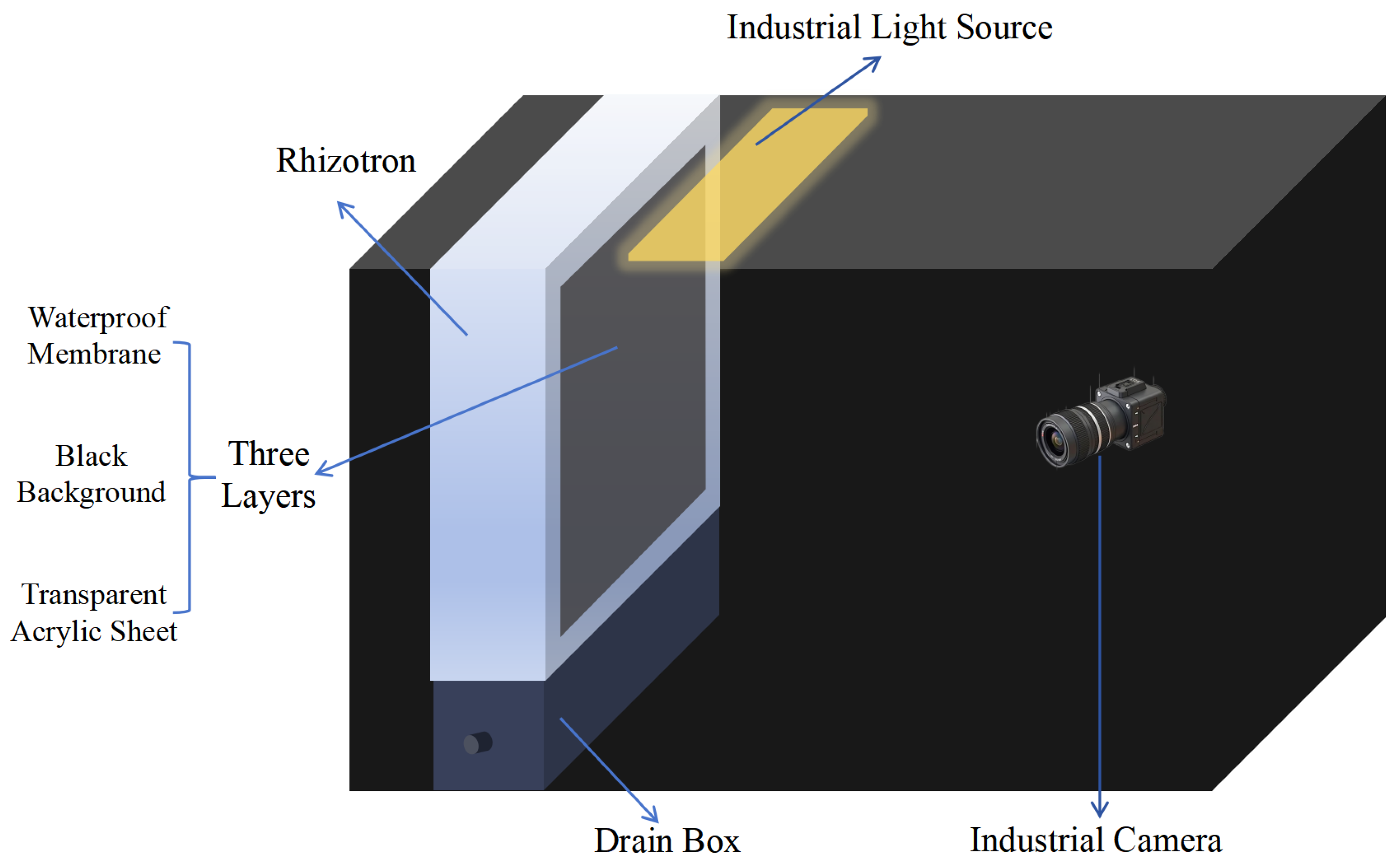

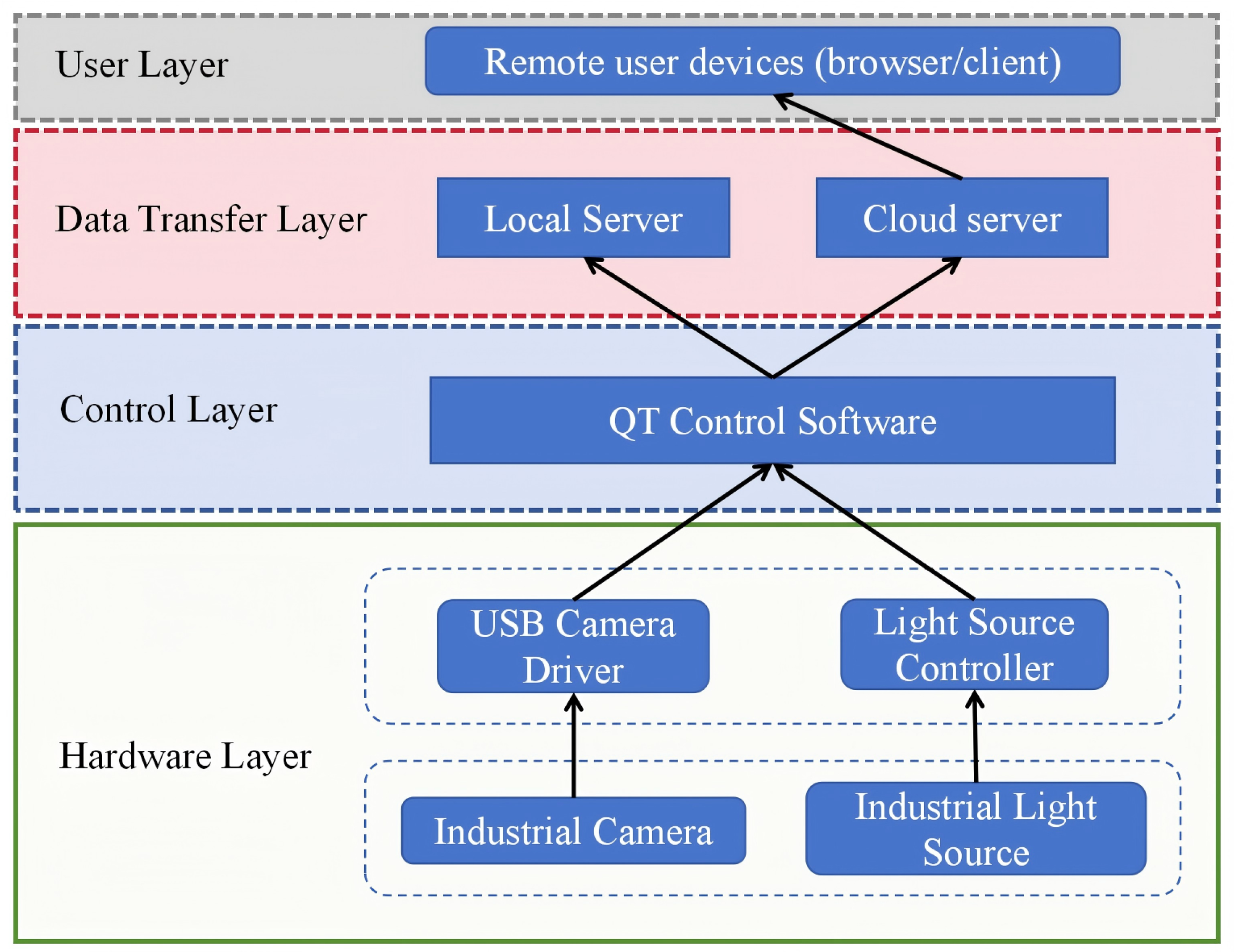

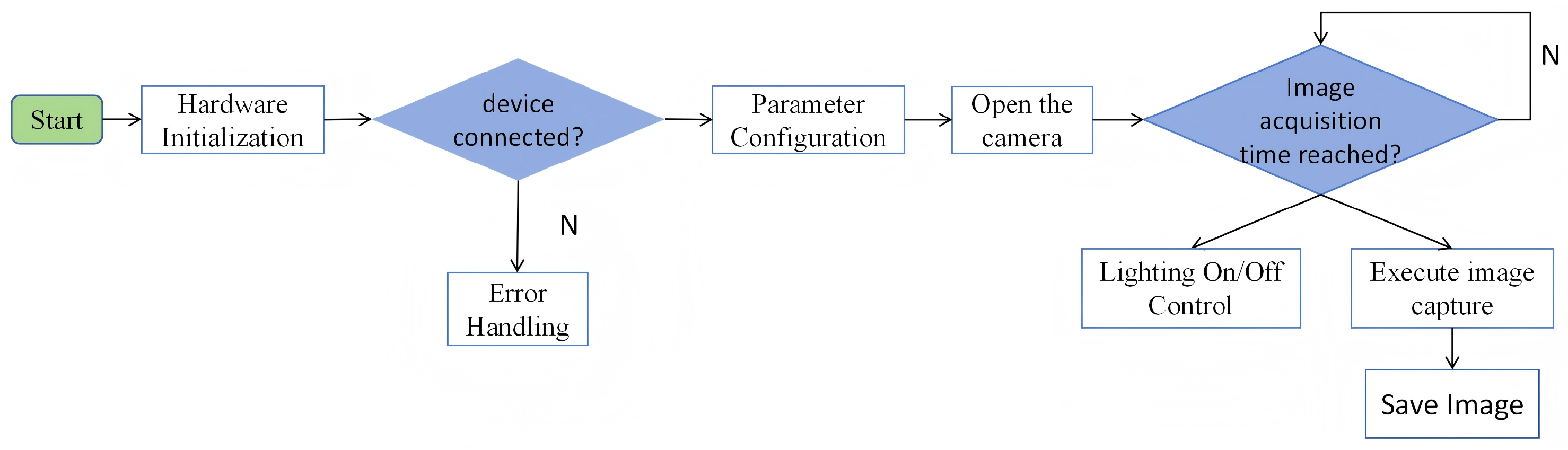

2.2. Image Acquisition Devices

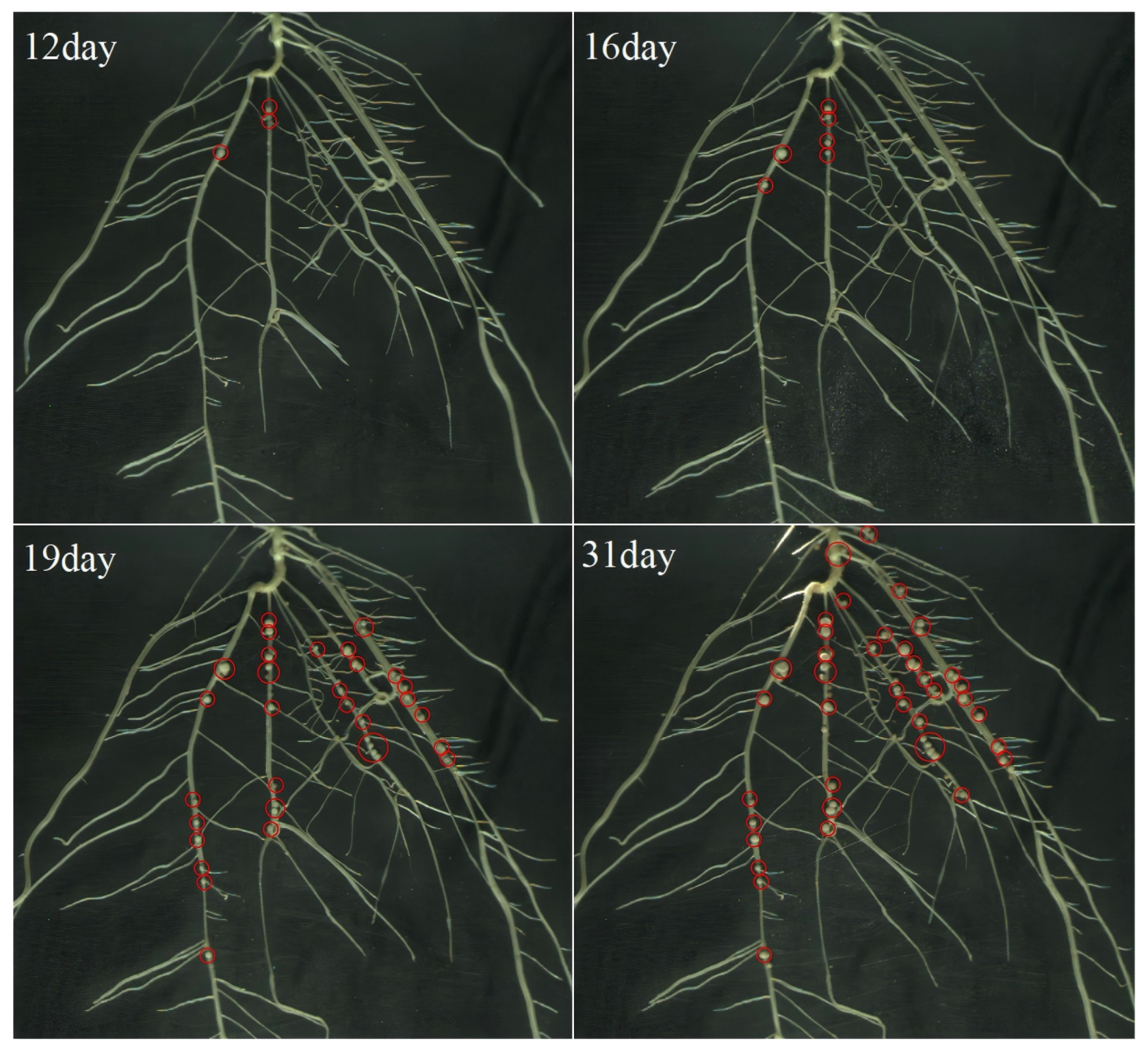

2.3. Root System Image Acquisition and Time-Series Dataset Construction

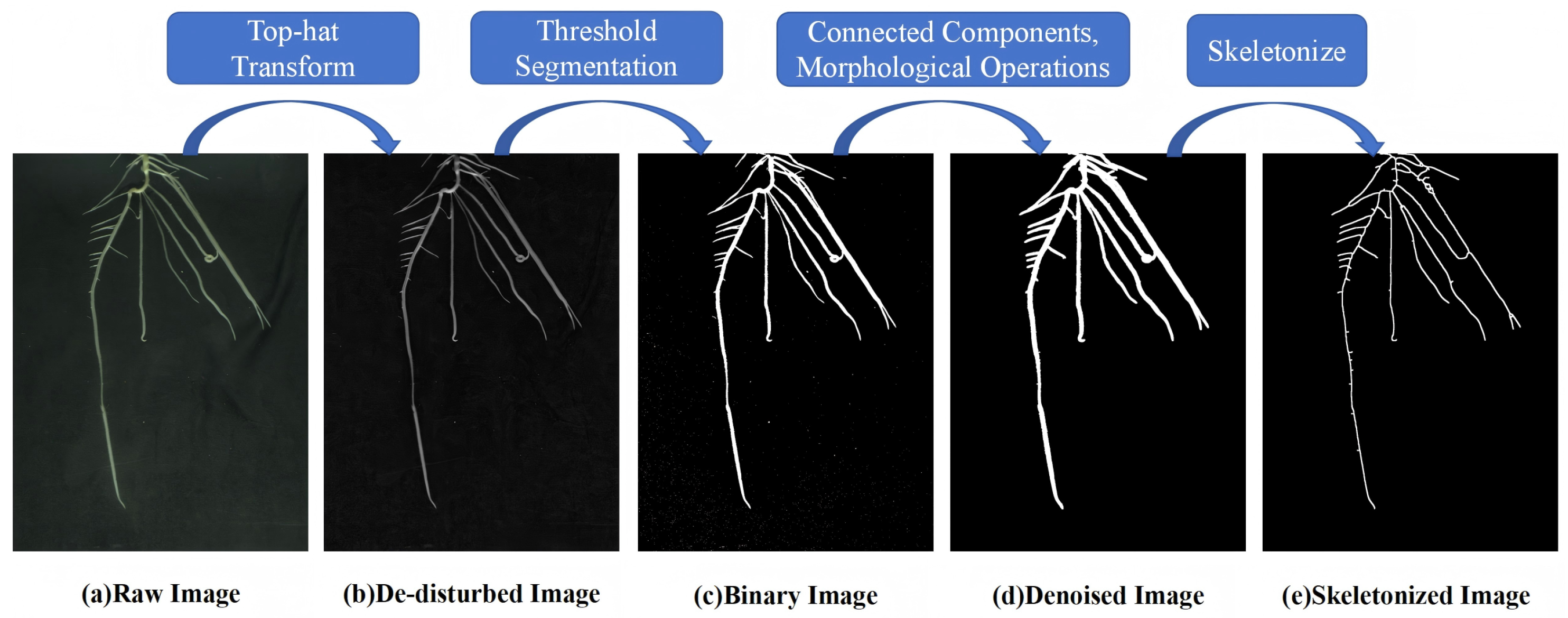

2.4. Root Image Processing

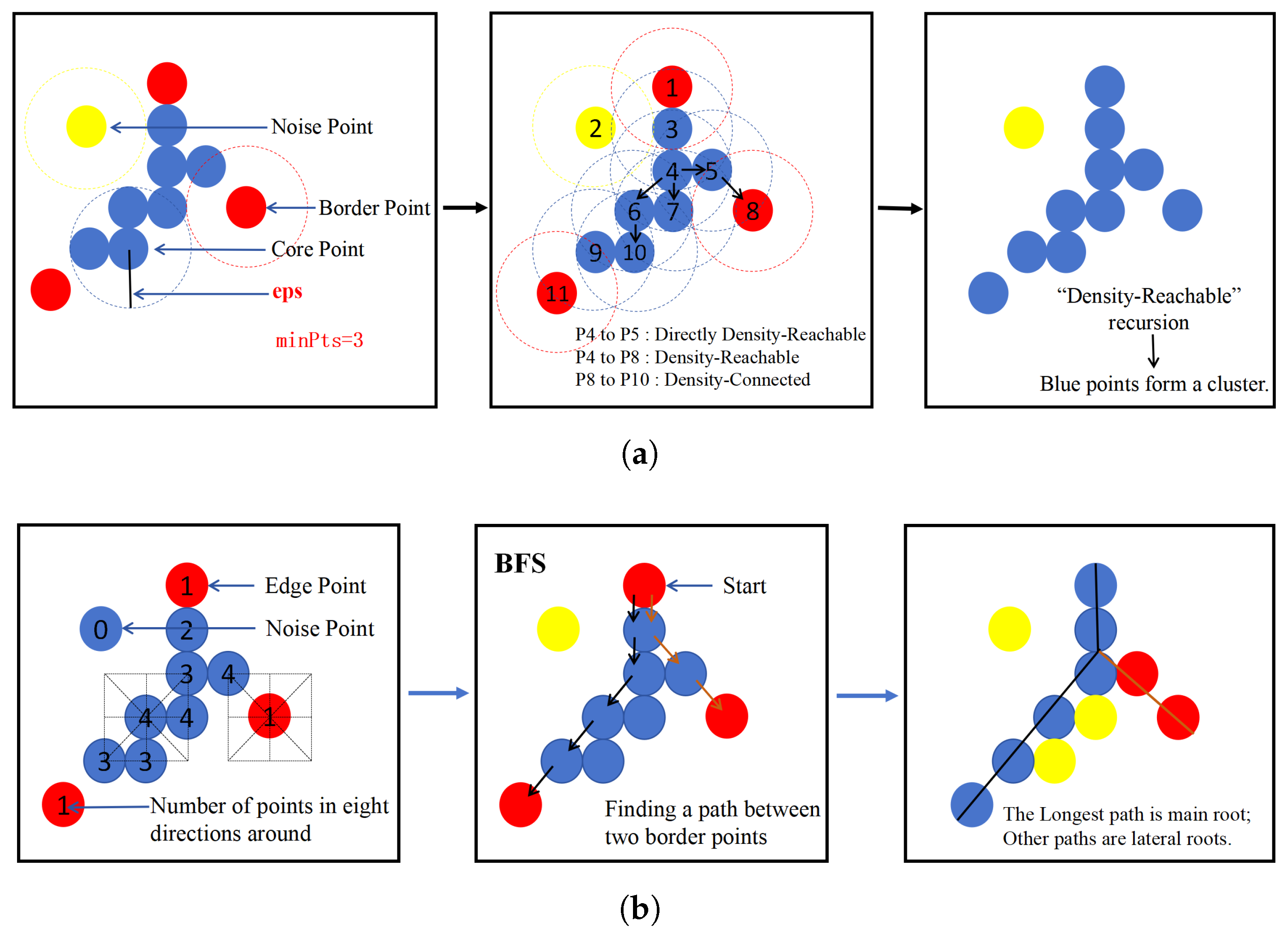

2.5. Algorithm for Semantic Segmentation of Root Systems (RootPO-DBSCAN)

2.6. Root Phenotypic Characterization

3. Results

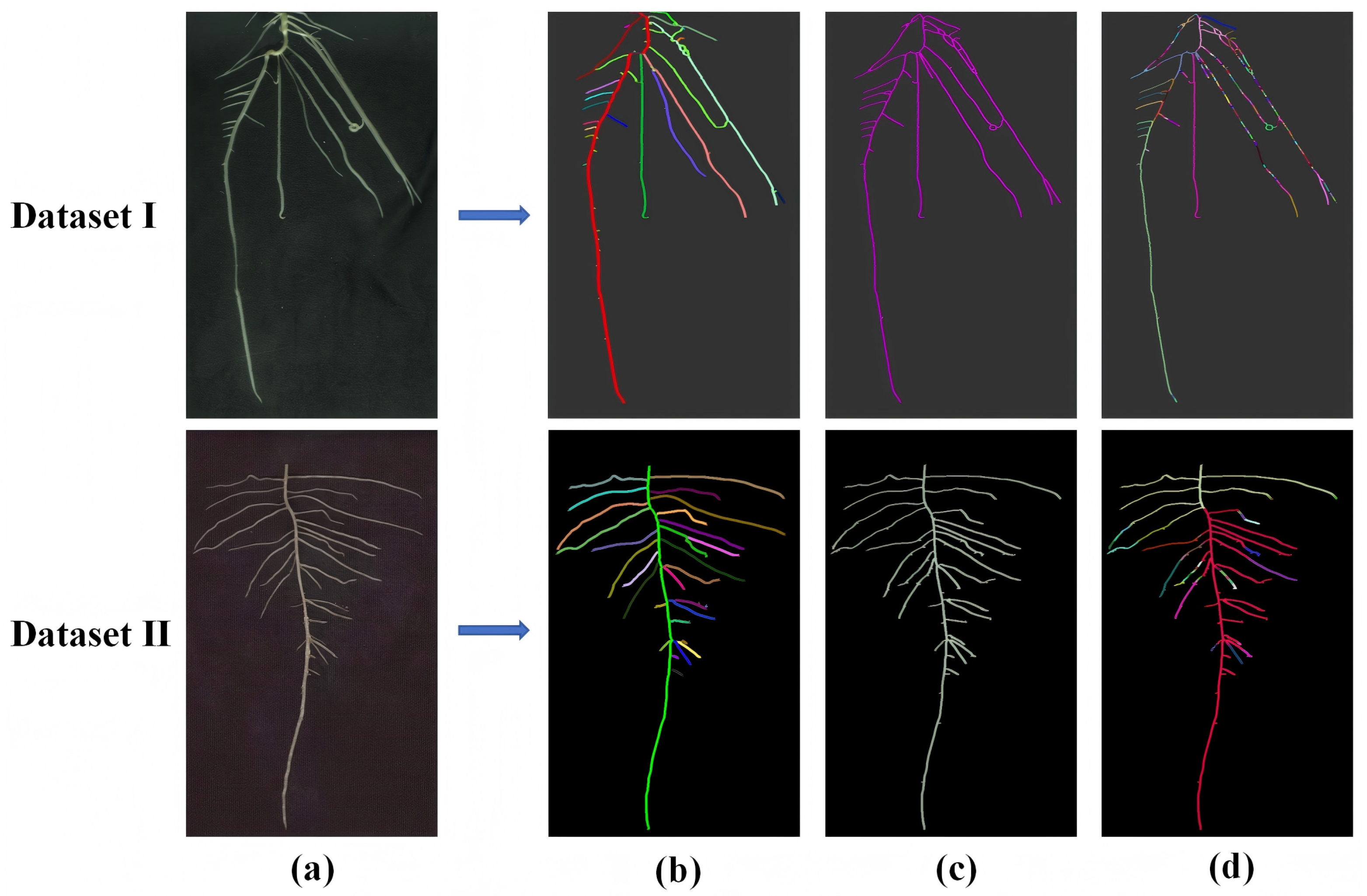

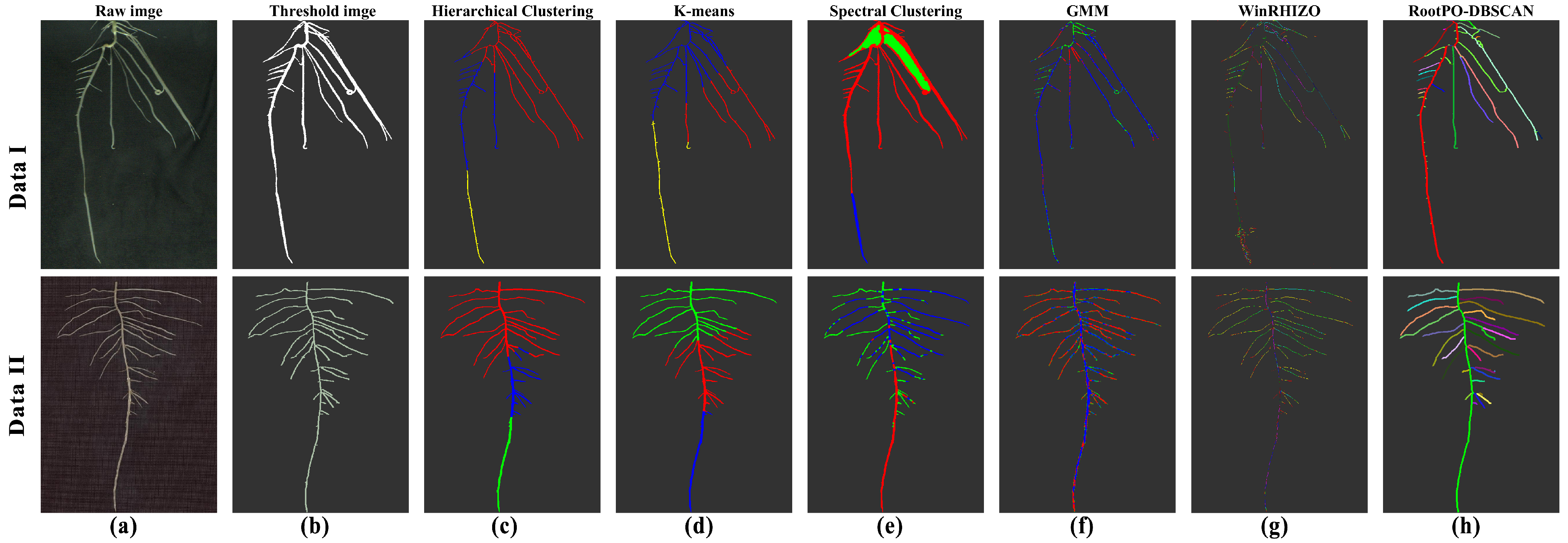

3.1. RootPO-DBSCAN Algorithm Segmentation Effect and Comparison

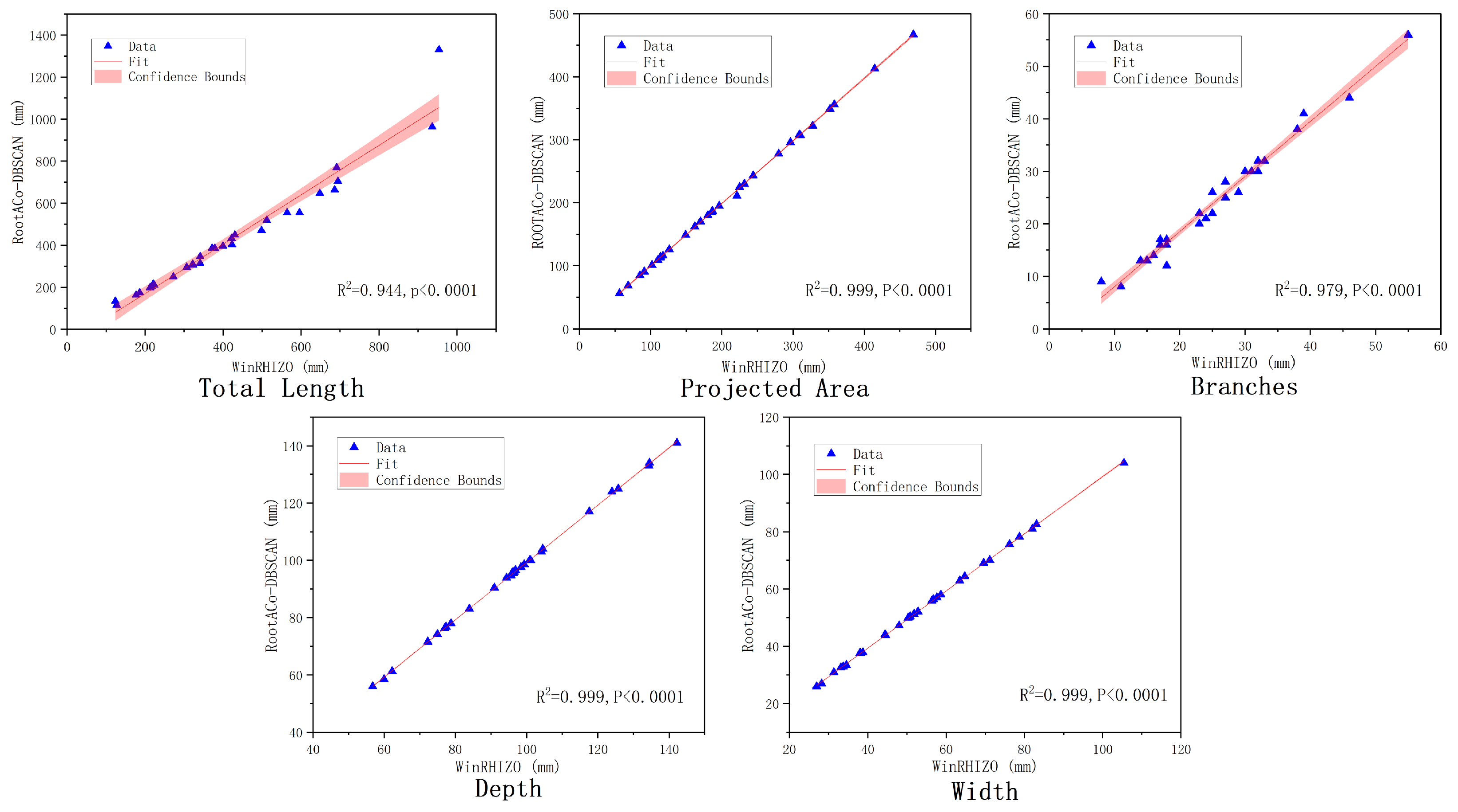

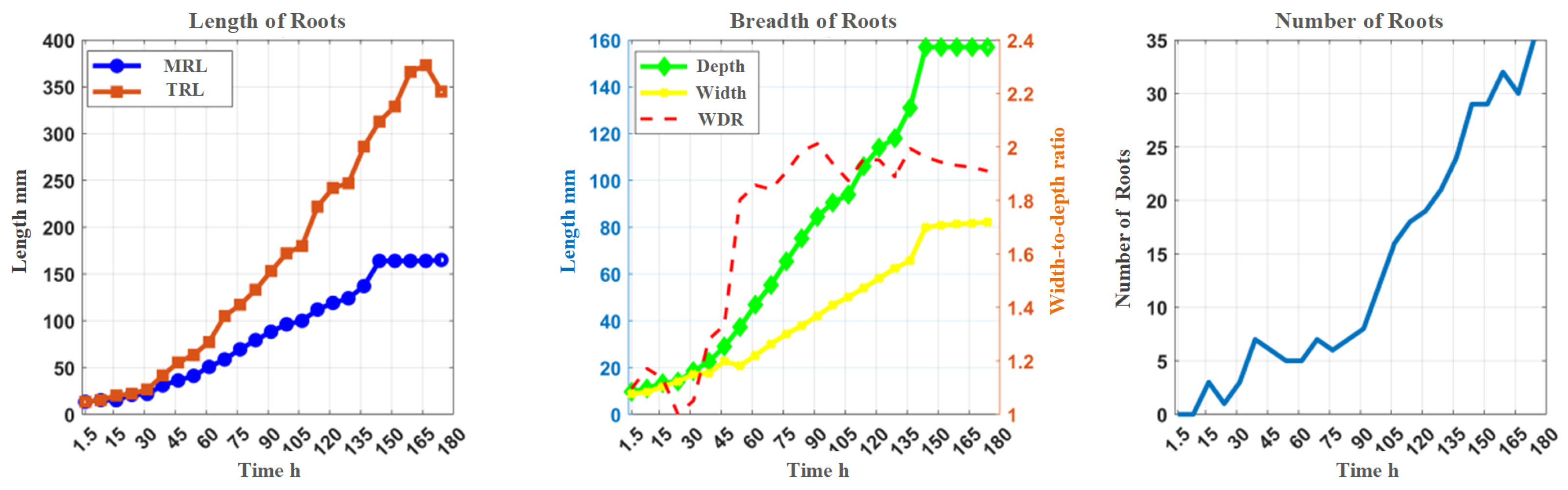

3.2. Growth Curve Plotting

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of RootPO-DBSCAN Algorithm and NMRS

4.2. Broader Implications and Future Translation

4.3. Study Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodge, A.; Berta, G.; Doussan, C.; Merchan, F.; Crespi, M. Plant root growth, architecture and function. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 153–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yung, W.S.; Gao, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.W.; Lam, H.M. From phenotyping to genetic mapping: Identifying water-stress adaptations in legume root traits. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Gemenet, D.C.; Villordon, A. Root system architecture and abiotic stress tolerance: Current knowledge in root and tuber crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqbool, S.; Hassan, M.A.; Xia, X.; York, L.M.; Rasheed, A.; He, Z. Root system architecture in cereals: Progress, challenges and perspective. Plant J. 2022, 110, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, P.; Castro, I.; Couto, P.; Leal, F.; Carnide, V.; Rosa, E.; Carvalho, M. Root Phenotyping: A Contribution to Understanding Drought Stress Resilience in Grain Legumes. Agronomy 2025, 15, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, F. Adaptive minirhizotron for pepper roots observation and its installation based on root system architecture traits. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, A.Y.P.; Pires, R.d.M.; Silva, A.; dos Sanots, L.; Matsura, E.E. Minirhizotron as an in-situ tool for assessing sugarcane root system growth and distribution. Agric. Res. Technol. 2019, 22, 10–19080. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, R.; Liu, J. Progresses in methods for observing crop root pattern system. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 2008, 36, 429–435. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, E.; Millas, R.; McNeal, W.; Faris, J.; Taheri, A. Variation analysis of root system development in wheat seedlings using root phenotyping system. Agronomy 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passot, S.; Gnacko, F.; Moukouanga, D.; Lucas, M.; Guyomarc’h, S.; Ortega, B.M.; Atkinson, J.A.; Belko, M.N.; Bennett, M.J.; Gantet, P.; et al. Characterization of pearl millet root architecture and anatomy reveals three types of lateral roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slota, M.; Maluszynski, M.; Szarejko, I. An automated, cost-effective and scalable, flood-and-drain based root phenotyping system for cereals. Plant Methods 2016, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer-Pascuzzi, A.S.; Symonova, O.; Mileyko, Y.; Hao, Y.; Belcher, H.; Harer, J.; Weitz, J.S.; Benfey, P.N. Imaging and analysis platform for automatic phenotyping and trait ranking of plant root systems. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, K.A.; Lenz, H.; Kastenholz, B.; Gilmer, F.; Averesch, A.; Putz, A.; Heinz, K.; Fischbach, A.; Scharr, H.; Fiorani, F.; et al. The platform GrowScreen-Agar enables identification of phenotypic diversity in root and shoot growth traits of agar grown plants. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez-Garcia, A.; Motes, C.M.; Scheible, W.R.; Chen, R.; Blancaflor, E.B.; Monteros, M.J. Root traits and phenotyping strategies for plant improvement. Plants 2015, 4, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, C.A.; Hickey, L.T.; Fletcher, S.; Jennings, R.; Chenu, K.; Christopher, J.T. High-throughput phenotyping of seminal root traits in wheat. Plant Methods 2015, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, K.A.; Putz, A.; Gilmer, F.; Heinz, K.; Fischbach, A.; Pfeifer, J.; Faget, M.; Blossfeld, S.; Ernst, M.; Dimaki, C.; et al. GROWSCREEN-Rhizo is a novel phenotyping robot enabling simultaneous measurements of root and shoot growth for plants grown in soil-filled rhizotrons. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, S.J.; Pridmore, T.P.; Helliwell, J.; Bennett, M.J. Developing X-ray computed tomography to non-invasively image 3-D root systems architecture in soil. Plant Soil 2012, 352, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cao, X.; Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Li, Y.; Luo, X. A method of 3D nondestructive detection for plant root in situ based on CBCT imaging. In Proceedings of the 2014 7th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Informatics, Dalian, China, 14–16 October 2014; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, J.; Kirchgessner, N.; Colombi, T.; Walter, A. Rapid phenotyping of crop root systems in undisturbed field soils using X-ray computed tomography. Plant Methods 2015, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A.; Wingen, L.U.; Griffiths, M.; Pound, M.P.; Gaju, O.; Foulkes, M.J.; Le Gouis, J.; Griffiths, S.; Bennett, M.J.; King, J.; et al. Phenotyping pipeline reveals major seedling root growth QTL in hexaploid wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2283–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dusschoten, D.; Metzner, R.; Kochs, J.; Postma, J.A.; Pflugfelder, D.; Bühler, J.; Schurr, U.; Jahnke, S. Quantitative 3D analysis of plant roots growing in soil using magnetic resonance imaging. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugfelder, D.; Metzner, R.; Van Dusschoten, D.; Reichel, R.; Jahnke, S.; Koller, R. Non-invasive imaging of plant roots in different soils using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Plant Methods 2017, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Chao, K.; Kim, M.S. Machine vision technology for agricultural applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2002, 36, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A.; Pound, M.P.; Bennett, M.J.; Wells, D.M. Uncovering the hidden half of plants using new advances in root phenotyping. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, R.; Kato, Y. Comparison of threshold algorithms for automatic image processing of rice roots using freeware ImageJ. Field Crops Res. 2011, 121, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, G.; Nakhforoosh, A.; Arnold, T.; Leitner, D. Hyperspectral imaging: A novel approach for plant root phenotyping. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zare, A.; Sheng, H.; Matamala, R.; Reyes-Cabrera, J.; Fritschi, F.B.; Juenger, T.E. Root identification in minirhizotron imagery with multiple instance learning. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2020, 31, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, T.T.; Willemsz, T.A.; van Kessel, G.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K. A density-based segmentation for 3D images, an application for X-ray micro-tomography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 725, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamine, B.; Nadia, B. Image segmentation using clustering methods. In Proceedings of the SAI Intelligent Systems Conference, London, UK, 21–22 September 2016; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Hao, X.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Shao, L. Real-time superpixel segmentation by DBSCAN clustering algorithm. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 5933–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.K.; Borgefors, G.; di Baja, G.S. A survey on skeletonization algorithms and their applications. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2016, 76, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M. Morphological image processing. IJCST 2011, 2, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In Proceedings of the KDD, Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; Volume 96, pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.; Rehman, S.U.; Aziz, K.; Fong, S.; Sarasvady, S. DBSCAN: Past, present and future. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on the Applications of Digital Information and Web Technologies (ICADIWT 2014), Chennai, India, 17–19 February 2014; pp. 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bundy, A. Catalogue of artificial intelligence tools. In Catalogue of Artificial Intelligence Tools; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 7–161. [Google Scholar]

- Silvela, J.; Portillo, J. Breadth-first search and its application to image processing problems. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2001, 10, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, S.; Sriadhi, S.; Martiano, M.; Simarmata, J. Comparison analysis of K-means and K-medoid with Ecluidience distance algorithm, Chanberra distance, and Chebyshev distance for big data clustering. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 420, p. 012092. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Seraj, R.; Islam, S.M.S. The k-means algorithm: A comprehensive survey and performance evaluation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Contreras, P. Algorithms for hierarchical clustering: An overview. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2012, 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Crow, W.; Luc, J.; McSorley, R.; Giblin-Davis, R.; Kenworthy, K.; Kruse, J. Comparison of water displacement and WinRHIZO software for plant root parameter assessment. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 1308–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornaro, C.; Macolino, S.; Menegon, A.; Richardson, M. WinRHIZO technology for measuring morphological traits of bermudagrass stolons. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 3007–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Begum, N.; An, T.; Zhao, T.; Xu, B.; Zhang, S.; Deng, X.; Lam, H.-M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Siddique, K.H.M. Characterization of root system architecture traits in diverse soybean genotypes using a semi-hydroponic system. Plants 2021, 10, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Xi, J.; Ding, Y.; Duan, J.; Qi, B.; Yao, T.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Ding, C.; Yang, G.; et al. Research on Curing Tobacco Image Segmentation Based on K-means Clustering Algorithm. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2024, 52, 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y. An improved U-Net-based in situ root system phenotype segmentation method for plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Rostamza, M.; Song, Z.; Wang, L.; McNickle, G.; Iyer-Pascuzzi, A.S.; Qiu, Z.; Jin, J. SegRoot: A high throughput segmentation method for root image analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Dunbabin, V.M.; Diggle, A.J.; Siddique, K.H.; Rengel, Z. Development of a novel semi-hydroponic phenotyping system for studying root architecture. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phenotypic Characterization Name | Symbolic | Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| Main root length | MRL | Length of main root (mm) |

| Total root length | TRL | Cumulative length of all roots (mm) |

| Depth | DEP | Maximum vertical distance reached by the root system (mm) |

| Width | WID | Maximum horizontal width of the entire root system (mm) |

| Width-to-depth ratio | WDR | Ratio of maximum width to depth |

| Total number of roots | TNR | Number of all branches |

| Projection area | PA | Projected area of the root in a two-dimensional plane (mm2) |

| Parameter | Hierarchical Clustering | K-Means | DBSCAN | GMM | Spectral Clustering | RootPO-DBSCAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.6752 | 0.5480 | 0.6728 | 0.6141 | 0.7489 | 0.8444 |

| Recall | 0.6134 | 0.5450 | 0.6263 | 0.5939 | 0.7217 | 0.9203 |

| F1-score | 0.6229 | 0.5312 | 0.6320 | 0.5780 | 0.7248 | 0.8743 |

| MIOU | 0.5313 | 0.4588 | 0.5298 | 0.4920 | 0.6391 | 0.7921 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, K.; Xu, S.; Menz, C.; Yang, F.; Fraga, H.; Santos, J.A.; Liu, B.; Yang, C. A Novel Semi-Hydroponic Root Observation System Combined with Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation for Root Phenotyping. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122794

Li K, Xu S, Menz C, Yang F, Fraga H, Santos JA, Liu B, Yang C. A Novel Semi-Hydroponic Root Observation System Combined with Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation for Root Phenotyping. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122794

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Kunhong, Siyue Xu, Christoph Menz, Feng Yang, Helder Fraga, João A. Santos, Bing Liu, and Chenyao Yang. 2025. "A Novel Semi-Hydroponic Root Observation System Combined with Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation for Root Phenotyping" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122794

APA StyleLi, K., Xu, S., Menz, C., Yang, F., Fraga, H., Santos, J. A., Liu, B., & Yang, C. (2025). A Novel Semi-Hydroponic Root Observation System Combined with Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation for Root Phenotyping. Agronomy, 15(12), 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122794