Abstract

Agricultural water resources face growing pressure from rising food demand and environmental changes. In large agricultural irrigation areas, water and land use is closely linked to energy consumption, carbon emissions, and food production. Therefore, regulating the water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus under multiple external changes is essential for achieving sustainable agriculture. This study aims to optimize water and land allocation in large agricultural irrigation areas to enhance yields and reduce carbon emissions under different external environments and production conditions. A spatial–temporal synergistic optimization and regulation model for water and land resources in large agricultural irrigation zones is developed. Based on 191 representative irrigation districts in Heilongjiang Province, multiple scenarios are constructed, including water-saving irrigation, climate change and low-carbon irrigation energy transitions. Optimal solutions are identified using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III. The results indicate that, after optimization in the current scenario, crop production increased by 2.13%, carbon emissions decreased by 1.23%, and irrigation energy productivity rose by 9.33%. Concurrently, water-saving irrigation should be prioritized in western regions. This study provides an efficient water management pathway for major food production regions.

1. Introduction

Ensuring food security amid accelerating social processes and rapid population growth is one of the greatest global challenges [1]. Since 2000, global crop production has increased by 56% due to farmland expansion and technological advancements, at the cost of rising water resource demands [2]. The intensifying competition for agricultural water use has emerged as a critical constraint on the sustainability of the global food system. Agriculture is the largest water-consuming sector, with irrigation accounting for over 70% of global freshwater consumption [3]. However, agricultural irrigation currently relies predominantly on fossil fuel-based energy for water supply, resulting in significant greenhouse gas emissions. This resource consumption pattern further exacerbates the vulnerability of agricultural systems under climate change [4].

The global sustainable development agenda provides a clear direction for resolving this contradiction. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a systematic framework, with Zero Hunger (SDG2), Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG6), Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG7), and Climate Action (SDG13) closely linked to the agricultural sector. The Paris Agreement’s net-zero emissions roadmap highlights the need for enhanced multi-resource coordination in the agricultural sector to meet the 2050 emission reduction target [5]. Consequently, balancing the interactions among water resources, land use, food production, energy consumption, and carbon emissions has emerged as a central challenge for sustainable agricultural development.

In agricultural systems, water, land, energy, food, and carbon emissions are not independent elements but constitute an interdependent and mutually constraining five-dimensional nexus (water–land–energy–food–carbon system) [6]. This nexus perspective enables the precise identification of cross-system linkages among agricultural natural resources and provides essential support for developing integrated regulation strategies [7,8]. Irrigation districts, as spatial units where the water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus is intricately intertwined, play a crucial role in strategies for food security and agricultural carbon reduction [9,10].

Although existing studies have considered such multi-factor interconnections, they still face significant limitations. They are typically confined to individual irrigation districts or focus on river basins/administrative regions, overlooking the regulatory needs of large agricultural irrigation areas that lie between these scales [11,12]. Large agricultural irrigation areas are formed through the integration of multiple contiguous irrigation districts that collectively face shared resource constraints. They play an irreplaceable role in coordinating the key trade-offs between productivity improvement and carbon emissions within the five-dimensional nexus, and in enabling large-scale optimization of water and land resource allocation across aggregated irrigation districts. Such integrated clusters help overcome the fragmented resource scheduling challenges characteristic of dispersed irrigation districts and allow coordinated regulation of multiple nexus elements from a scaled, district-integration perspective, providing a more operable regulatory carrier for safeguarding agricultural productivity and advancing the low-carbon transition.

Carbon emissions in the agricultural sector are becoming increasingly prominent and are gradually emerging as a significant constraint on agricultural development. Carbon emissions in agriculture reach as high as 7.1 Gt CO2 annually [13], with energy consumption and related emissions from irrigation systems accounting for 15% of the total [14]. Traditional irrigation methods not only exacerbate water scarcity but also lead to significant carbon emissions due to fossil fuel-powered pumping equipment [15]. However, the application of water-saving irrigation measures also exhibits considerable complexity. On one hand, these measures reduce water consumption per unit area and play a critical role in water allocation and land planning in large agricultural irrigation areas [16]. On the other hand, the associated increase in energy consumption for water lifting, fluctuations in carbon emission intensity, and high construction costs constrain their large-scale promotion [17]. Climate change has increased the uncertainty in the spatiotemporal distribution of water resources and crop water demand, further amplifying the need for water conservation in agriculture [18]. Meanwhile, the low-carbon transition of the irrigation energy structure (with an increased share of clean energy sources such as photovoltaic power, hydropower, and nuclear power) can effectively reduce carbon emissions, but faces constraints from rising energy costs that limit the scale of irrigation districts [19,20,21]. The superimposition of multiple constraints renders the construction of a multi-factor coupled optimization decision-making system imperative.

Based on the above background and identified challenges, this study proposes the following hypotheses: (1) the five-dimensional nexus in large agricultural irrigation areas exhibits quantifiable synergies and trade-offs, which can be finely managed to simultaneously achieve stable food production, efficient resource utilization, and carbon reduction; (2) under the constraints of climate change, energy transition, and various water-saving measures, multi-objective optimization can be employed to maximize comprehensive benefits. The core objective of this study is to develop a spatiotemporally coordinated optimization framework for the five-dimensional nexus in large agricultural irrigation areas, providing scientific support for the green transformation of agriculture.

To achieve these objectives, the following technical pathway is designed. First, a five-dimensional multi-objective decision-making model integrating food production, resource use, carbon emissions, and economic activities is established to optimize the fine-scale, decadal irrigation regimes and crop planting structure in large agricultural irrigation areas. Second, a coupled scenario system incorporating climate change, water-saving measures, and low-carbon energy is constructed to reveal the mechanisms through which multiple changing conditions influence crop water consumption and planting patterns in irrigation districts. Finally, a comprehensive assessment is conducted across dimensions including water use efficiency, adaptability of cropping structures, carbon reduction potential, energy input–output, and cost–benefit of water-saving infrastructure, leading to the identification of optimal construction pathways for irrigation districts. By decoupling conflicts among multiple objectives, this framework aims to provide a practical optimization paradigm for the coordinated management of large agricultural irrigation areas.

2. Materials and Methods

This study, based on the analysis of multi-factor coupling and spatiotemporal heterogeneity, developed a multi-objective optimization model framework for the coordinated management of the five-dimensional nexus. Building on this, three major scenarios were constructed: climate change, upgrading of water-saving irrigation, and the low-carbon transformation of irrigation energy structure. A hybrid solution strategy combining the third-generation Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III) [22] and the dynamic entropy-weighted TOPSIS method [23] was employed to select the optimal configuration plan that balances multiple objectives. Additionally, the net present value and investment payback period under the scenario of irrigation water-saving construction in irrigation districts were analyzed to reveal the contribution of different scenarios to shortening the investment payback period.

2.1. Model Framework

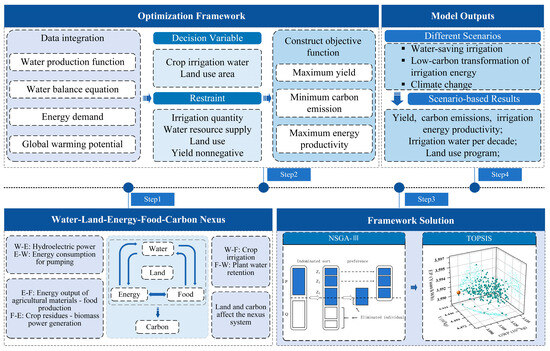

This study developed a multi-objective optimization model based on the interlinked relationships among water, land, energy, food, and carbon. The specific procedures and their correspondence to research objectives are as follows:

- Data preprocessing: Integrate multi-source data, including crop coefficients, meteorological data, energy structure data, etc., and standardize the spatiotemporal units (temporal scale: ten days; spatial scale: irrigation district unit).

- Correlation function construction: Fit correlation functions between water–energy (pumping energy consumption), water–grain (water productivity), soil–carbon (total carbon emissions), and energy–carbon (carbon emissions per unit energy input) using least squares methods.

- Model Development: Establish decision variables (irrigated area, surface/groundwater irrigation volume per unit area) and constraints (upper/lower limits of irrigation water per unit area, land area variation range, water resource supply) to align model objectives with core research goals: reducing carbon emissions, enhancing irrigation energy productivity, and increasing crop yields.

- Model Solution: Employ the NSGA-III algorithm for multi-objective optimization, generating a Pareto solution set. Subsequently, rank the solutions using the Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS method (where weights are determined by objective data entropy values) to identify optimal configuration schemes.

- Result Output: Based on different scenario settings, output core indicators such as yield, carbon emissions, and irrigation energy productivity, along with corresponding ten-day irrigation plans and crop planting structure schemes. The specific framework of the model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research framework.

Figure 1. Research framework.

2.1.1. Objective Function

- (1)

- Maximum crop production

Crop production is the core element of a regional food security system, playing a decisive role in ensuring the sufficiency and stability of food supply. The crop yield per unit area is obtained through effective rainfall during the growing season, irrigation water (decision variable), and the water productivity function. The regional yield is then calculated by combining the crop irrigation area (decision variable). The total yield is the sum of the yields across all regions.

- (2)

- Maximum irrigation energy productivity

Agricultural irrigation activities are highly energy-dependent, with their energy consumption constituting a significant portion of the overall energy demand in the agricultural sector. This is primarily reflected in the consumption of electricity and fossil fuels. This is primarily reflected in the consumption of electricity and fossil fuels. The study considers energy consumption from pump-powered irrigation as the direct energy expenditure associated with crop cultivation. Minimizing energy consumption while ensuring irrigation efficiency helps reduce the energy dependence of irrigation districts and lowers carbon emissions resulting from energy use. Energy units are converted into a unified thermodynamic unit, joules (J), and combined with net crop production revenue to represent irrigation energy productivity.

The economic benefits are composed of crop production revenue, planting material costs, water costs, and energy costs. The revenue is generated through crop production:

The cost of planting materials consists of fertilizers, pesticides, agricultural films, machinery, and labor costs used in the agricultural production process:

Water costs refer to the price of water used for irrigation, which is influenced by irrigation water volume, irrigation water use efficiency, and irrigated area. The specific formula is as follows:

Irrigation energy consumption refers to the energy expended by water pumps during pumping operations, which is directly related to the water source location, pump head, and water conveyance losses. The relevant formula is referenced from the articles by Li et al. [24] and Correa-Cano et al. [25], as shown below.

Irrigation energy costs refer to the composition of energy supplied for irrigation and the associated energy prices. The specific formula is as follows.

Irrigation energy economic productivity is represented as the ratio of net agricultural revenue to the energy consumption of the irrigation system.

- (3)

- Minimum carbon emissions

Agricultural carbon emissions are calculated using the emission factor method [26]. The sources of carbon emissions in this study are divided into two parts: one generated from agricultural planting [27], and the other from irrigation energy consumption. The actual irrigation energy consumption was estimated based on the relevant study by Liu et al. [28], combined with the electricity-to-heat conversion ratio in energy generation. Methane in agricultural production is primarily generated from rice fields; therefore, this study considers only methane emissions from rice fields. The specific formula is as follows:

In practical research, the Global Warming Potential (GWP) is commonly used to measure and compare the impact of different greenhouse gases on global warming relative to carbon dioxide over a specified time period [29]. The greenhouse gases discussed in this study include CO2, CH4, and N2O generated from energy production and crop cultivation, with the specific formulas outlined below.

2.1.2. Model Constraint

The model takes into account the irrigation water usage per unit area, changes in land area, and regional water availability constraints.

- (1)

- Irrigation water per unit area

Crop yields are closely related to irrigation water volume. As irrigation water increases, crop yields typically follow a quadratic function pattern, first rising and then declining. A slight water deficit can enhance water productivity while maintaining yield levels [30]. By integrating different irrigation methods, the allowable range of irrigation water per unit area is defined based on crop water requirements.

- (2)

- Changes in land area

Under the premise of considering the economic benefits and food security of irrigation districts, adjust the cropping areas within these districts to address situations where climate change exceeds the limits of irrigation water regulation. It is stipulated that changes in the land area of the irrigation district shall not exceed the allowed range.

- (3)

- Regional water availability

The regional water resource consumption shall not exceed the available water supply.

2.1.3. Parameter Meaning

To clearly illustrate the meaning of each objective function and constraint, Table 1 presents the definition of each parameter.

Table 1.

The definition of the model parameters.

2.1.4. Model Solution

NSGA-III is a multi-objective optimization algorithm based on spatial reference points. Compared to conventional genetic algorithms, it ensures a wide distribution of solutions on the Pareto front through non-domination sorting and reference-point-based induction mechanisms. NSGA-III typically performs well in handling high-dimensional objective optimization problems (often with ≥3 objectives) and complex constraint-based design scenarios.

TOPSIS is an evaluation method that calculates the proximity of solutions in a solution set to the most ideal result and ranks them accordingly. While TOPSIS clearly highlights the strengths and weaknesses of different solutions, its results are highly dependent on the weights assigned to each evaluation criterion. The entropy weight method objectively assigns weights to each evaluation criterion based on the data itself. Combining TOPSIS with the entropy weight method effectively enables decision-making on the Pareto solution set.

2.2. Study Area

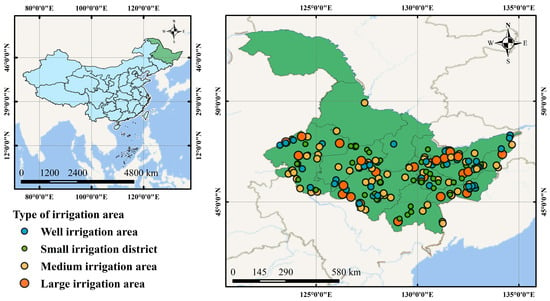

Heilongjiang Province is located at the northernmost tip of China, spanning 121°11′ to 135°05′ east longitude and 43°26′ to 53°33′ north latitude. Situated in the cold–temperate and temperate continental monsoon climate zone, it boasts abundant black soil resources that provide excellent growing conditions for staple crops such as rice, corn, and soybeans, making it a vital grain production base. While achieving high grain yields, Heilongjiang faces significant water resource constraints. Agricultural irrigation accounts for 87.3% of the province’s total water consumption, far exceeding the national average of 62.2%. Irrigation districts serve as the core support for the province’s grain production capacity and are the key link for the sustainable development of cold-region agriculture. Therefore, this study focuses on Heilongjiang’s extensive agricultural irrigation system—comprising 25 large-scale, 70 medium-scale, 44 small-scale pipe irrigation districts, and 52 well irrigation districts (Figure 2)—to implement precision regulation of water and soil resources based on the water–land–energy–grain–carbon linkage. Meanwhile, the average irrigation water utilization coefficient across typical districts ranged from 0.401 to 0.946, indicating substantial water-saving potential. Guided by resource efficiency enhancement, water-saving irrigation scenarios were developed for large-scale agricultural irrigation districts. By integrating external shifts in irrigation energy structures and climate change impacts, these scenarios effectively alleviate agricultural resource pressures, achieving synergistic development in water conservation, yield increase, and emission reduction.

Figure 2.

Overview map of the study area.

2.3. Scenario Setting

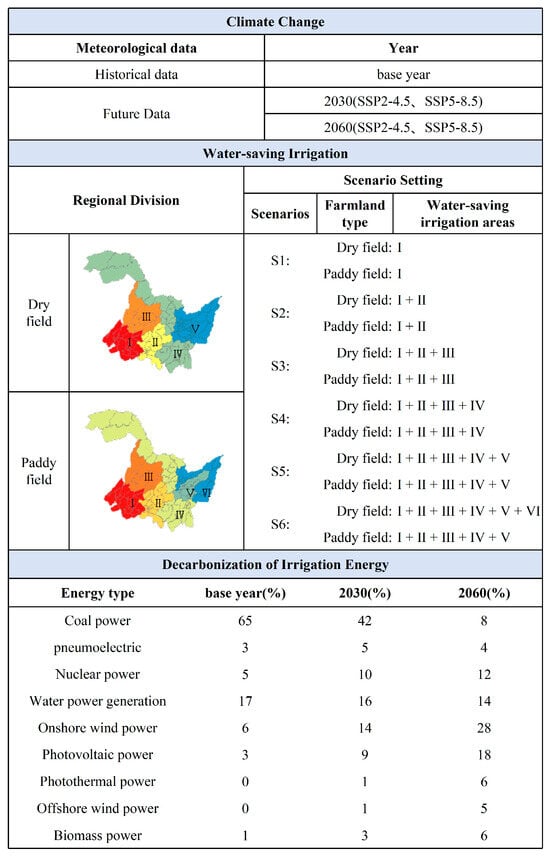

This study established multiple coupled scenarios integrating climate change projections, low-carbon irrigation energy transitions, and water-saving irrigation modes to quantify their impacts on decision-making within the water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus in large agricultural irrigation areas. Details are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Scenario model: I–VI denotes regions implementing water-saving irrigation.

- (1)

- Climate change scenarios

This study considered multi-scenario simulation data based on current and future scenarios. The current scenario corresponds to 2018, while future scenarios include the SSP2-4.5 medium forcing scenario and the SSP5-8.5 high forcing scenario under the 2030 carbon peak year and 2060 carbon neutrality year. Meteorological data under different climate scenarios were obtained to calculate crop water requirements and yields under climate change scenarios. Since the irrigation district data for the current year is derived from the 2018 statistical report, the irrigation district data for future scenarios will also be simulated based on the 2018 baseline.

Crop water requirements were determined using the single crop coefficient method. The reference evapotranspiration (ET0), which is highly influenced by meteorological factors, was calculated for each 10-day period at irrigation district locations based on data from 24 meteorological stations across Heilongjiang Province, using the Penman–Monteith equation.

where is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve, kPa/°C; is the net radiation at the crop surface, MJ; is the soil heat flux, MJ/(m2·day); is the Humidity Calculation Constant, kPa/°C; is the mean daily air temperature at 1.5–2.5 m height, °C; is the wind speed at 2 m height, m/s; is the saturation vapor pressure, kPa; is the actual vapor pressure, kPa.

Crop coefficients refer to the basic crop coefficients recommended in the Crop evapotranspiration—Guidelines for computing crop water requirements (FAO-56), published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Crop water consumption is determined using the crop coefficient method:

where represents the crop coefficient (dimensionless). This coefficient is segmented according to crop growth stages and characterizes the variability in water uptake by crops at different developmental phases. The actual crop coefficient for each irrigation district is obtained by applying meteorological data to the crop coefficient adjustment formula:

where is the initial crop coefficient (dimensionless); is the daily minimum relative humidity, %; is the mean crop height, m.

The effective rainfall required for model operation is obtained through the coefficient method [31]:

where represents effective rainfall; represents the rainfall coefficient; represents total rainfall. When ≤ 2 mm, = 0; when 2 mm < ≤ 50 mm, = 0.8; when > 50 mm, = 0.7.

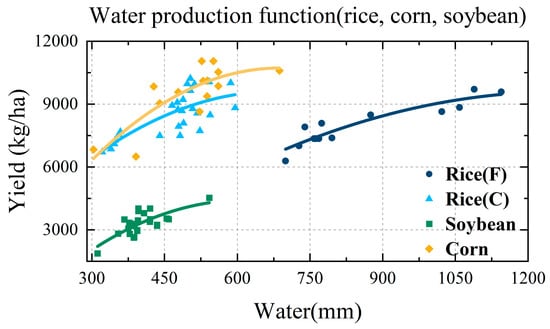

Crop yield is derived from a water production function. A quadratic water production function effectively captures the diminishing marginal water productivity effect, wherein yield declines once irrigation exceeds optimal levels. Accordingly, this study uses crop yield and water consumption data from Heilongjiang Province and applies the least squares method to fit a quadratic water production function, quantifying the relationship between irrigation water and crop yield. The detailed data is provided in the Supplementary Materials, Table 2 and Figure 4.

where represents the crop yield per unit area, kg/m3; is the sum of crop water consumption and rainfall, with seepage accounted for in rice field flooding [32], m3, , , are dimensionless coefficients.

Table 2.

Parameters related to the water production function.

Figure 4.

Water production function; F denotes flood irrigation, while C denotes controlled irrigation.

- (2)

- Water-saving irrigation scenarios

The water-saving irrigation scenarios are based on regional crop planting practices and economic development conditions. Using the Heilongjiang Province Local Water Use Quota Standards, rice fields are divided into six regions, and dryland fields into five regions. Priority is given to implementing water-saving irrigation in the economically developed but relatively arid southwestern region of Heilongjiang (rice fields: controlled irrigation, dryland fields: sprinkler (S), drip irrigation (D)), followed by implementation in the eastern regions, which are characterized by a humid climate and abundant water resources. The specific setup is shown in Figure 3.

- (3)

- Low-carbon transformation of irrigation energy structure scenarios

Low-carbon transformation refers to the process of transitioning the energy system from reliance on fossil fuels to a clean energy-dominated structure through technological optimization, policy guidance, and changes in consumption patterns. The scenario settings in this study refer to the power generation structure provided by the China Energy and Electricity Outlook and the Report On China’s Electric Power Development, which includes energy generation from coal, gas, nuclear, hydropower, onshore wind, photovoltaic, concentrated solar power, offshore wind, and biomass. Based on this, two scenarios were constructed: one for maintaining the status quo and another for the Low-carbon transformation of irrigation energy structure.

By combining two climate change scenarios, two low-carbon transformation of irrigation energy structure scenarios, and thirteen water-saving irrigation distribution scenarios, data were constructed for three time points: the base year (without climate change and low-carbon transformation of irrigation energy structure), 2030, and 2060, resulting in a total of 117 scenarios. The relevant scenario settings are shown in Figure 3.

2.4. Data Acquisition

The data required for model construction primarily come from various statistical yearbooks, water resource bulletins, and relevant literature. Data on the consumption of fertilizers, seeds, pesticides, and plastic film, as well as crop prices, labor, machinery, and the prices of fertilizers, seeds, pesticides, and plastic film, were sourced from the Compilation of National Agricultural Product Cost-Benefit Data. Water pricing data were referenced from the study by Li et al. [33]. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with crops, fertilizers, and pesticides were derived from the studies by Fan et al. [34], Shang et al. [35], and Wang et al. [36]. Data on the net calorific value of energy, carbon content, and carbon emission coefficients were obtained from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [37]. The composition of irrigation energy sources was derived from the study by Wang et al. [38], the Report on China’s Electric Power Development, and the China Energy & Electricity Outlook. Data on energy conversion efficiency and pump efficiency were sourced from the study by Li et al. [24]. Data on pump operating head and head loss were derived from the study by Zhang et al. [39]. Water resource supply data were obtained from the Heilongjiang Water Resources Bulletin; crop planting structure data were sourced from the Heilongjiang Statistical Yearbook.

2.5. Calculation of the Construction Payback Period

Based on Zou et al. [40] this study defines the construction and maintenance costs for sprinkler and drip irrigation systems. The investment payback period for water-saving irrigation infrastructure is then calculated from net benefits and construction costs to assess its feasibility. The formula is presented below.

where represents the construction and maintenance costs of water-saving facilities.

3. Results

3.1. Coordinated Optimization of the Water–Land–Energy–Food–Carbon Nexus in Irrigation Districts Under Climate Change

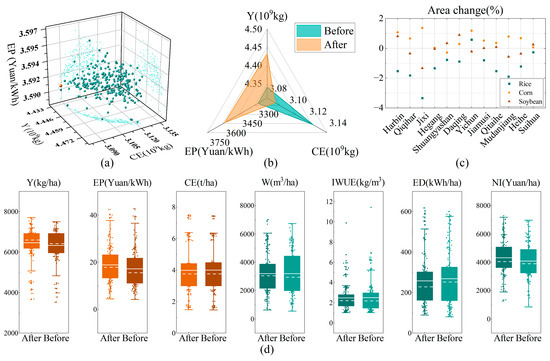

This section analyzes the coordinated optimization results of the water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus in the irrigation districts for both the base year and future projection years. The results for the base year scenario are presented in Figure 5. The optimization produced favorable outcomes, including a 2.13% increase in grain yield, a 1.23% reduction in carbon emissions, and a 9.33% improvement in irrigation energy productivity, while maintaining nearly unchanged cropland area and irrigation water consumption. Changes in yield were primarily driven by variations in crop planting scale (total output) and water application rate per unit area (unit yield). Figure 5c illustrates the post-optimization changes in crop planting areas at the municipal level: rice field areas generally decreased (by up to 3.34%), whereas maize areas increased (by up to 1.37%). This shift is attributable to maize having the highest yield per unit of water consumed, thereby effectively boosting grain production. Irrigation energy productivity, which is strongly influenced by energy demand and realized revenue, was enhanced by resizing gravity-fed and pumped irrigation districts. This adjustment yielded a 5.19% increase in net benefits and a 2.8% reduction in energy consumption, and indirectly reduced greenhouse gas emissions. As shown in Figure 5d, these outcomes correspond to the observed changes in irrigation energy productivity.

Figure 5.

Base year optimization results. (a) Pareto front and selected optimal solution following optimization (the red dot represents the optimal solution); (b) Comparison of crop production (Y), carbon emissions (CE), and irrigation energy productivity (EP) before and after optimization; (c) post-optimization changes in crop planting structure; (d) Changes in crop production (Y), irrigation energy productivity (EP), carbon emissions (CE), average water consumption (W), irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE), energy demand (ED), and net benefits (NI) before and after optimization. Solid lines denote mean values; dashed lines denote median values.

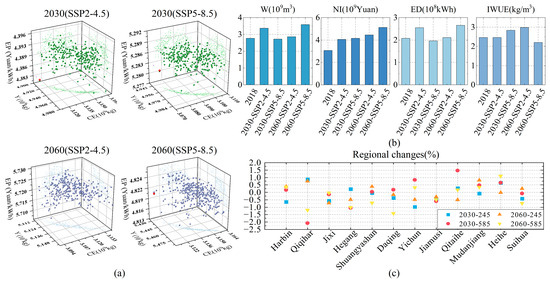

Figure 6 presents the optimization outcomes for 2030 and 2060 under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 climate change scenarios. Under climate change, increased thermal resources in Heilongjiang Province enhanced crop water demand and yields. As shown in Figure 6a, yields in 2030 under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 are 4.91 × 109 kg and 4.95 × 109 kg, respectively, rising to 5.13 × 109 kg and 5.43 × 109 kg in 2060, indicating substantial improvements. Typical irrigation districts’ net benefits increased by 67% as a result of the yield gains (Figure 6b). Greenhouse gas emissions and irrigation energy productivity exhibited considerable fluctuations due to the tight coupling between pumping energy consumption and irrigation volume: in years with abundant rainfall, reduced irrigation leads to lower energy demand and consequently lower GHG emissions. Figure 6b depicts irrigation water use efficiency under different climate scenarios, showing an inverse trend to energy demand. This is primarily because pumped irrigation districts—characterized by efficient conveyance systems with minimal transmission losses but high pumping energy consumption—are constrained in irrigation volume and scale by carbon reduction objectives, resulting in variability in water use efficiency.

Figure 6.

Optimization results for 2030 and 2060 under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 climate change scenarios; (a) shows the optimized Pareto distribution and optimal solutions (the red dot represents the optimal solution); (b) illustrates the changes in irrigation water use (W), energy demand (ED), net benefits (NI), and water use efficiency (WUE) under different climate scenarios; (c) depicts changes in irrigation district scales across regions under climate change.

The increase in crop production is associated with adjustments to the crop planting structure. Under future climate scenarios, the trends in crop planting structure mirror those of the base year, characterized by declines in rice field areas and expansions in maize and soybean cultivation. Although the total land area remained essentially constant, pronounced regional disparities emerged (Figure 6c): irrigation areas in western semi-arid districts of Heilongjiang—such as Qiqihar and Daqing—declined markedly by 0.89–1.19% and 0.18–1.42%, respectively. This indicates that crop cultivation in the western semi-arid districts is highly sensitive to climatic changes and necessitates timely adjustments to planting strategies based on prevailing climate conditions.

3.2. Water Consumption and Investment Payback Period for Irrigation Districts Under Climate Change and Water-Saving Scenarios

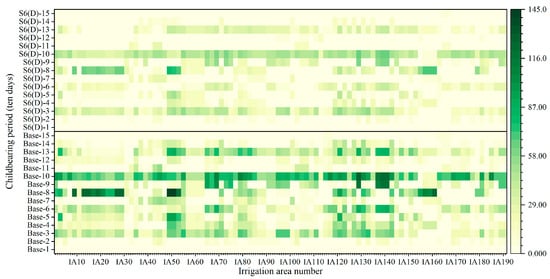

Scenario S6 (D)—in which all irrigation districts implement drip and controlled irrigation—yields the optimal outcomes in terms of yield increase, carbon reduction, and improvements in irrigation energy use efficiency. Figure 7 depicts the average water consumption per ten-day period (15 periods in total) in the irrigation districts under the base year scenario and Scenario S6 (D). Water use was mainly concentrated from late July to mid-August, coinciding with high temperatures and peak evapotranspiration in Heilongjiang Province, with relatively high consumption in some districts during mid-September. An average water-saving of 154.41 mm was achieved, with 43.96 mm saved during peak crop water demand periods (Figure 7). The effects of water-saving irrigation were evident: rice fields employed controlled irrigation to adjust both irrigation frequency and volume per event; dryland fields reduced conveyance losses by installing distribution pipelines. Although these measures incur higher irrigation costs, they result in significantly improved overall net benefits.

Figure 7.

Water-consumption optimization under the S6 (D) scenario: the vertical axis denotes growth-stage divisions in ten-day intervals (Base indicates the base year scenario); the horizontal axis denotes irrigation districts (the correspondence between irrigation districts and their designations is provided in the Supplementary Materials).

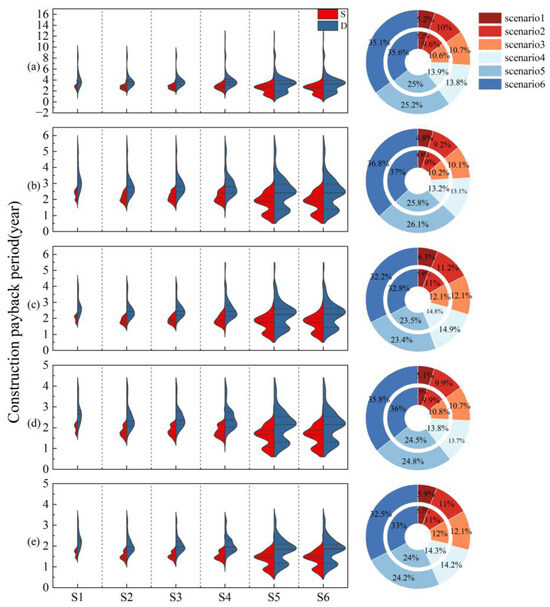

Figure 8 presents the investment payback periods for water-saving irrigation infrastructure under climate change scenarios. Under the sprinkler irrigation scenarios, payback periods for S1 (S), S2 (S), and S3 (S) generally fall within four years, whereas in S4 (S) some medium-sized irrigation districts exhibit payback periods exceeding eight years, indicating that the benefits are insufficient to offset construction costs. In the drip irrigation scenarios, payback periods are generally longer than those of sprinkler systems, with an average extension of 1.12 years in the base year (Figure 8a). Districts with payback periods exceeding five years are predominantly located in the semi-arid western region of Heilongjiang Province, over half of which are well-irrigated districts. Overall, large irrigation districts exhibit shorter payback periods than medium, small and well-irrigated districts. This is because large irrigation districts have greater construction scales and relatively low irrigation water use efficiencies (0.41–0.51), resulting in substantial cost savings from water-saving investments. In contrast, well-irrigated districts in the semi-arid western regions have higher water use efficiencies (0.64–0.95), leading to limited incremental benefits and consequently longer payback periods.

Figure 8.

Investment payback periods (in years) and water-saving performance under different climate scenarios, where the inner ring represents the water-saving ratio for drip irrigation and the outer ring represents the water-saving ratio for sprinkler irrigation. S denotes sprinkler irrigation and D denotes drip irrigation; (a) represents the base year climate scenario; (b) represents the 2030 SSP2-4.5 climate scenario; (c) represents the 2030 SSP5-8.5 climate scenario; (d) represents the 2060 SSP2-4.5 climate scenario; (e) represents the 2060 SSP5-8.5 climate scenario.

In terms of total water savings, drip irrigation performs better than sprinkler irrigation across all scenarios, with an increase of 0.3–2.9%. The contribution of sprinkler and drip irrigation to overall water savings remains comparable across scenarios, with differences ranging from only 0.1% to 0.6% (Figure 8). However, sprinkler irrigation features lower construction and maintenance costs, facilitating the rapid development of high-standard farmland and enabling faster capital recovery in the short term. Under climate change conditions, yield improvements increase economic returns, thereby shortening the payback period of water-saving infrastructure investments. This indicates that future implementation of water-saving irrigation will become increasingly favorable.

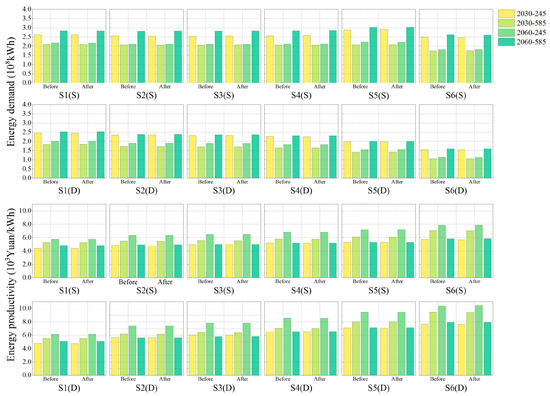

3.3. Energy Consumption Analysis Under Climate Change, Water-Saving Irrigation, and Low-Carbon Transformation of Irrigation Energy Structure Scenarios

Figure 9 illustrates the impact of low-carbon adjustments to the irrigation energy structure on system efficiency under different climate scenarios. The adoption of water-saving measures under climate change scenarios does not alter the trend in energy demand and irrigation energy productivity, and the low-carbon transformation of the energy structure has limited control over overall system energy consumption (with cross-scenario fluctuations under 1%). At the water-saving irrigation level, as the implementation scope of drip irrigation expands (from S1 to S6), energy demand gradually decreases, and energy productivity significantly improves (with an increase of 64–79% under the S6 scenario); under sprinkler irrigation scenarios S1 through S4, energy demand remains relatively stable; in scenario S5, it shows a slight increase; and in scenario S6, energy consumption decreases by 1–15% relative to the base-year scenario. The reduction in energy consumption under scenario S6 is primarily attributable to controlled irrigation in rice fields reducing deep percolation, thereby substantially conserving irrigation water. As the main rice-producing region, the Sanjiang Plain demonstrates in scenarios S5 and S6 that adjusting irrigation district scale and adopting water-saving irrigation measures for rice fields confirms the significant impact of water-saving irrigation on district water consumption, as well as the necessity of differentiated water-saving strategies for resource optimization.

Figure 9.

Changes in energy demand and irrigation energy productivity before and after the low-carbon transformation of the irrigation energy structure.

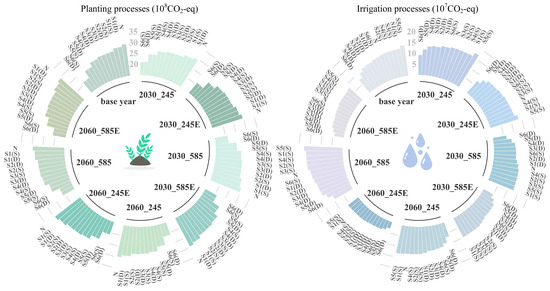

3.4. Carbon Emissions Under Climate Change, Water-Saving Irrigation, and Low-Carbon Irrigation Energy Scenarios

This study accounts for agricultural greenhouse gas emissions from both field-level direct emissions and indirect emissions generated by irrigation pumping, as shown in Figure 10. Under water-saving irrigation scenarios, carbon emission intensities vary markedly by irrigation mode: conventional irrigation (N) results in the highest emissions due to sustained rice flooding and active methane release, whereas water-saving methods reduce rice methane emissions by up to 29% through precise moisture regulation. From an energy perspective, drip irrigation (supported by low-pressure distribution and precision water delivery technologies) reduces carbon intensity by 38–46% relative to conventional systems due to lower pumping energy requirements. In contrast, the sprinkler irrigation system exhibits a water–energy trade-off: although it improves irrigation water use efficiency, the increase in energy consumption leads to higher indirect carbon emissions, with a maximum increase of 14% under the S5 scenario (Figure 10). Notably, in simulations incorporating both climate change and low-carbon irrigation energy scenarios, fluctuations in total field-level emissions remain below 1% for any given irrigation scenario, demonstrating the limited capacity of climate change and irrigation energy transitions to regulate field-level carbon emissions. The coupled analysis of water-saving irrigation and low-carbon irrigation energy reveals that an increase in clean energy penetration can reduce unit irrigation carbon emissions (by 20–22% in 2030 and 54.5–55% in 2060, Figure 10), highlighting the significant role of low-carbon energy transitions in reducing carbon emissions within agricultural irrigation systems.

Figure 10.

Annual carbon emissions at the crop-cultivation and irrigation levels under all scenarios; Planting processes: Greenhouse gases from agricultural activities (including fertilization, pesticide use, mechanical operations, etc.); Irrigation processes: Greenhouse gases generated by energy consumption for water pumping.

4. Discussion

Leveraging a multi-scenario coupling mechanism—encompassing climate change, energy transition, and low-carbon irrigation energy—and a spatiotemporal heterogeneity analysis framework, this study introduces a novel multi-objective dynamic optimization model for coordinated management of the water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus in large agricultural irrigation areas. Grounded in the large-scale adaptive characteristics of a quadratic water production function and coupled with spatial optimization of crop planting structures, the research elucidates the mechanisms by which coordinated regulation of water and land resources enhances food production.

Under the base year scenario, spatial reallocation of water and land resources increased the average grain yield in irrigation districts increased the average grain yield in the irrigation districts by 2.13% (Figure 5), validating the dual-path optimization logic of “water allocation for yield improvement and land scale adjustment for total production enhancement.”

Under the coordinated objectives of water saving and yield enhancement, the cultivated area of rice shows a decreasing trend, which is consistent with the findings of Wu et al. [41]. The spatial distribution of regional cropland changes aligns with climatic zones, with arid and semi-arid regions exhibiting more pronounced fluctuations due to stronger water resource constraints and greater sensitivity of crop water requirements to climate variability [42]. Because irrigation energy consumption is closely linked to water use, it is directly influenced by the coordinated regulation of water and land resources. Land use changes also affect carbon emissions across the irrigation districts. However, optimizing irrigation methods proves effective in emission reduction—converting all rice fields to controlled irrigation can reduce carbon emissions by up to 29%, primarily due to reduced methane emissions through precise soil moisture regulation.

In future scenarios, irrigation water demand exhibits pronounced divergence: under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, demand in 2030 changes by +21.7% and −2.1%, respectively, and by +2.9% and +29.3% in 2060 (Figure 6). These differences are primarily driven by the spatiotemporal coupling between rainfall and crop water requirements. Under SSP5-8.5, the slight increase in precipitation in 2030 partially offsets the rise in crop water demand, whereas extreme warming in 2060 intensifies evapotranspiration, making conventional irrigation insufficient to meet crop water requirements. Notably, although the adoption of water-saving irrigation technologies increases energy consumption, it enhances irrigation water productivity and improves economic returns. However, the high capital expenditure associated with water-saving infrastructure necessitates differentiated implementation rather than uniform large-scale deployment, consistent with the findings of Mishra [43]. Furthermore, although the low-carbon transition of irrigation energy has limited control over total system energy consumption (cross-scenario fluctuations < 1%) (Figure 9), it substantially reduces total carbon emissions—by 20–22% in 2030 and 54–55% in 2060 (Figure 10). This reduction results from the substitution of fossil fuels with clean energy sources, decreasing combustion-related emissions. These results refine current understandings of the irrigation energy–carbon relationship, indicating that the value of low-carbon transition lies more in reducing marginal carbon emissions than in constraining total energy consumption.

Considering the short-term construction costs and return on investment of water-saving irrigation, along with factors such as crop yield, energy consumption, and carbon emissions, it is recommended that water-saving irrigation modes—specifically controlled irrigation for paddy fields and sprinkler irrigation for dryland fields—be prioritized in irrigation districts in western Heilongjiang (including Qiqihar, Daqing, Suihua, and Harbin) during the base year and by 2030. By 2060, a province-wide implementation of controlled irrigation for paddy fields and drip irrigation for dryland fields is recommended. This provides a sound basis for the development of high-standard farmland in Heilongjiang Province.

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations remain, mainly associated with the trade-offs required for regional-scale assessment. (1) The quadratic water production function used in this study has been shown to perform well under mild deficit irrigation at the regional scale and is suitable for capturing the overall crop water–yield response under such conditions. However, under scenarios of severe water shortage, crop responses may become highly nonlinear and more sensitive to stress thresholds, in which more mechanistic models may be required to more accurately represent yield reductions; (2) The analysis focuses on irrigation district operation and water–land resource management without large-scale adjustments to land use patterns, leading to constrained optimization potential under the base year scenario. (3) Soil physical properties are represented through regional irrigation water-use efficiency indicators, a widely accepted and appropriate approach for large-scale regional assessments. At this scale, these indicators adequately reflect the dominant soil effects on irrigation performance. For fine-scale, site-specific management, however, incorporating mechanistic soil–water models would provide additional refinement.

Future research may address these aspects through several extensions: (1) extending the modeling framework to account for more severe water-deficit conditions, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of system-wide optimization strategies under intensified water scarcity; (2) expanding the boundary of land use adjustment constraints to explore broader crop-planting structure reconfiguration pathways, thereby maximizing the synergistic benefits of coordinated water and land resource allocation; (3) integrating a broader set of CMIP6 climate scenario models to evaluate optimization outcomes under diverse future climate pathways, thereby enabling a more comprehensive exploration of irrigation and resource management strategies across multiple possible climate conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a multi-objective optimization model for large agricultural irrigation areas based on the coupled water–land–energy–food–carbon nexus, systematically assessing the potential for optimized water and land resource allocation across 191 typical irrigation districts in Heilongjiang Province under various climate change, energy transition, and low-carbon irrigation scenarios. The results indicate the following:

- (1)

- The model can quantify the interactions among water, land, energy, crop yield, and carbon emissions, providing a scientific basis for achieving the synergistic goals of yield enhancement, emission reduction, and improved energy efficiency.

- (2)

- While water-saving measures optimize water use, they may alter energy demand; therefore, irrigation planning must integrate considerations of energy structure and carbon emissions to achieve overall system optimality.

- (3)

- The model reveals spatial differences and optimization potential in intra- and inter-district water and land allocation, offering a quantitative framework for regional water resource management and sustainable agricultural development.

- (4)

- Beyond guiding high-standard farmland construction and fine-scale water resource management, the proposed approach provides a transferable analytical tool for exploring agricultural adaptation to climate change, energy transitions, and low-carbon development.

Overall, this study demonstrates the feasibility of achieving coordinated optimization of agricultural production, energy use, and environmental protection within complex coupled systems. It highlights the importance of systems-based analysis and model-driven decision-making in regional water and land resource management and offers a reference for applying multi-objective optimization methods in other agricultural regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122776/s1, Figure S1: Sensitivity analysis results; Table S1: Name of irrigation district and corresponding number [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W., H.L. and M.L.; methodology, H.L. and Y.C.; software, Z.W. and Y.C.; validation, Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W., H.L. and Y.C.; resources, M.L.; Investigation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, L.W., M.L.; visualization, X.L. and L.H.; supervision, L.H., L.W. and M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52479035) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD1502000).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the reviewers for their dedication to our article. The academic experience of reviewers has brought us great convenience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Zhuo, L.; Ji, X.; Tian, P.; Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, F.; Duan, Y.; Wu, P. Water-Saving Irrigated Area Expansion Hardly Enhances Crop Yield While Saving Water under Climate Scenarios in China. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermid, S.; Nocco, M.; Lawston-Parker, P.; Keune, J.; Pokhrel, Y.; Jain, M.; Jägermeyr, J.; Brocca, L.; Massari, C.; Jones, A.D.; et al. Irrigation in the Earth System. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.W.; Conant, R.T.; Marston, L.T.; Choi, E.; Mueller, N.D. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from US Irrigation Pumping and Implications for Climate-Smart Irrigation Policy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Wollenberg, E.; Benitez, M.; Newman, R.; Gardner, N.; Bellone, F. Roadmap for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in Global Food Systems by 2050. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Understanding the Nexus. In Proceedings of the Bonn2011 Conference: The Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus, Bonn, Germany, 16–18 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, P.; Han, C.; Gojenko, B.; Qu, B.; Jiang, E.; Muminov, S. A Comprehensive Assessment Indicator of the Water-Energy-Food Nexus System Based on the Material Consumption Relationship. J. Hydrol. 2024, 633, 130997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, J.E.; Castillo-Molar, A.; Fuentes-Cortés, L.F. A Multi-Objective Assessment for the Water-Energy-Food Nexus for Rural Distributed Energy Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 51, 101956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. A Multi-Objective Simulation-Optimization Framework for Water Resources Management in Canal-Well Conjunctive Irrigation Area Based on Nexus Perspective. J. Hydrol. 2025, 646, 132308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xia, S.; Huo, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Su, Y.; Guo, D. Two-Stage Multiobjective Decision-Making Method Based on Agricultural Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Case Study in Hetao Irrigation District, China. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2023, 149, 05023006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Huang, K.; Zhao, X. Optimizing Planting Management Practices Considering a Suite of Crop Water Footprint Indicators—A Case-Study of the Fengjiashan Irrigation District. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanipour, A.H.; Schoups, G.; Zahabiyoun, B.; Babazadeh, H. Meeting Agricultural and Environmental Water Demand in Endorheic Irrigated River Basins: A Simulation-Optimization Approach Applied to the Urmia Lake Basin in Iran. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Gabrielli, P. Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in Agriculture: A Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Duan, W.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Rosa, L. Global Energy Use and Carbon Emissions from Irrigated Agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Mushtaq, S.; Hafeez, M.; Maroulis, J. Greenhouse Gas Implications of Water Reuse in the Upper Pumpanga River Integrated Irrigation System, Philippines. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, F.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; et al. An Evaluation on the Effect of Water-Saving Renovation on a Large-Scale Irrigation District: A Case Study in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chau, S.; Bhattarai, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Connor, T.; Li, Y. Impacts of Irrigated Agriculture on Food–Energy–Water–CO2 Nexus across Metacoupled Systems. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Burney, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; et al. Climate Change Exacerbates the Environmental Impacts of Agriculture. Science 2024, 385, eadn3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Ali, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, R. Assessing Decarbonization Pathways by Weighing Carbon Mitigation Efficiency and Risks in China’s Energy System. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 114, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.; Lyden, S.; Franklin, E.; Harrison, M.T. Agrivoltaics as an SDG Enabler: Trade-Offs and Co-Benefits for Food Security, Energy Generation and Emissions Mitigation. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 19, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Z.; Du, E.; Zhang, N.; Nielsen, C.P.; Lu, X.; Xiao, J.; Wu, J.; Kang, C. Cost Increase in the Electricity Supply to Achieve Carbon Neutrality in China. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2013, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, G.; Zhang, J. Suitability Evaluation System for the Shallow Geothermal Energy Implementation in Region by Entropy Weight Method and TOPSIS Method. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, Q.; Singh, V.P.; Liu, D.; Li, T. Stochastic Multi-Objective Modeling for Optimization of Water-Food-Energy Nexus of Irrigated Agriculture. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 127, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Cano, M.E.; Salmoral, G.; Rey, D.; Knox, J.W.; Graves, A.; Melo, O.; Foster, W.; Naranjo, L.; Zegarra, E.; Johnson, C.; et al. A Novel Modelling Toolkit for Unpacking the Water-Energy-Food-Environment (WEFE) Nexus of Agricultural Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Peng, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, P. Research Progress on Carbon Sources and Sinks of Farmland Ecosystems. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 11, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Lu, X.; Zhuang, M.; Shi, G.; Hu, C.; Wang, S.; Hao, J. China’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Cropping Systems from 1978–2016. Sci Data 2021, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, F.; Deng, X. Half of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions from China’s Food System Occur during Food Production. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Jing, B.; Shi, W.; Chen, T.; Zhai, Z.; Song, J. Optimizing Root Distribution and Water Use Efficiency in Maize/Soybean Intercropping under Different Irrigation Levels: The Role of Underground Interactions. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 249, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratoglu, A.; Bilgen, G.K.; Angin, I.; Kodal, S. Performance Analyses of Effective Rainfall Estimation Methods for Accurate Quantification of Agricultural Water Footprint. Water Res. 2023, 238, 120011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.; Wassmann, R.; Sander, B.O.; Palao, L.K. Climate-Determined Suitability of the Water Saving Technology “Alternate Wetting and Drying” in Rice Systems: A Scalable Methodology Demonstrated for a Province in the Philippines. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, M.; Fu, Q.; Cao, K.; Liu, D.; Li, T. Optimization of Biochar Systems in the Water-Food-Energy-Carbon Nexus for Sustainable Circular Agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Qi, X.; Zeng, L.; Wu, F. Accounting of greenhouse gas emissions in the Chinese agricultural system from 1980 to 2020. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 9470–9482, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Yang, G.; Yu, F. Agricultural greenhouse gases emissions and influencing factors in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2015, 23, 354–364, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Liu, W.; Lei, B.; Du, L.; Xu, Z. Evaluation of Water Saving and Emission Reduction Potential of Rice in Heilongjiang Province Under Different Water-saving Irrigation Methods. Water Sav. Irrig. 2023, 11, 34–38, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme; Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Rothausen, S.G.S.A.; Conway, D.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, W.; Holman, I.P.; Li, Y. China’s Water–Energy Nexus: Greenhouse-Gas Emissions from Groundwater Use for Agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 014035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, S.; Wei, F.; Sun, H. What Did Irrigation Modernization in China Bring to the Evolution of Water-Energy-Greenhouse Gas Emissions? Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 282, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Li, Y.; Cremades, R.; Gao, Q.; Wan, Y.; Qin, X. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Water-Saving Irrigation Technologies Based on Climate Change Response: A Case Study of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhao, Z. Enhancing Agricultural Sustainability: Optimizing Crop Planting Structures and Spatial Layouts within the Water-Land-Energy-Economy-Environment-Food Nexus. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarh, G.F.; Chung, E.S.; Hamed, M.M.; Hassan, M.S.; Shahid, S. Changes in Aridity and Its Impact on Agricultural Lands in East Asia for 1.5 and 2.0 °C Temperature Rise Scenarios. Atmos. Res. 2023, 293, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Sudarsan, J.S.; Suribabu, C.R.; Murali, G. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Implementing a Solar Powered Water Pumping System—A Case Study. Energy Nexus 2024, 16, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Effect of Different Irrigation Patterns on Forming of Carbohydrate of Japonica Rice in Cold Region. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2013. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Nie, T.; Zhao, J. Uptake of Basal Application Nitrogen by Rice from Black Soil under Water-saving Irrigation in Temperate Region. J. Irrig. Drain. 2019, 38, 36–43, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Z.; Du, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Ma, R.; Cai, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Huang, C.; et al. The Impact of Irrigation Methods on Grain Yield and Water Use Efficiency of the New Japonica Rice Variety Fuhe 3. China Seed Ind. 2019, 1, 67–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J. Experiment Study of Water-Saving Irrigation Model of Rice Introduced in Hongqiling farm of Heilongjiang Province. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, P.; Shehakk; Zhang, Z. Use Efficiency of Water and Nitrogen of Soybean with Water Stress by Stable Carbon Isotope Discrimination. Soybean Sci. 2018, 37, 906–914, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. Experimental Study on Effects of Different Water and Fertilizer Managements on Water Use and Carbon Balance of Paddy Fields in Black Soil Region under Straw Returning. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2021. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Z. Experimental Study on Economic Benefits, Quality, and Water Productivity of Rice Cultivation in Cold Black Soil under Different Water and Nitrogen Coupling Modes. Water Sav. Irrig. 2016, 3, 35–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X. Effects of tillage management on soil water dynamics, yield and water use efficiency in arable black soil cropping system in Northeast China. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2012, 30, 126–131, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, H. Effects of Mulched Drip Irrigation on Water and Heat Conditions in Field and Maize Yield in Sub humid Region of Northeast China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2015, 46, 93–104+135, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, J. Modeling the Effects of Plastic Film Mulching on Irrigated Maize Yield and Water Use Efficiency in Sub-Humid Northeast China. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, P.; Zheng, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, J. Effects and Benefit Analysis of Maize Straw Mulching No-tillage Drenching Technology on Drought Resistance and Seedling Preservation in Semi-arid Area. Heilongjiang Agric. Sci. 2021, 1, 11–13, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, X.; Lamlom, S.F.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Yuan, M.; et al. Cultivation Model and Deficit Irrigation Strategy for Reducing Leakage of Bundle Sheath Cells to CO2, Improve 13C Carbon Isotope, Photosynthesis and Soybean Yield in Semi-Arid Areas. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 285, 153979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, Z. Study on soybean yield and water use efficiency in different drip irrigation amount. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2012, 43, 100–104, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Research on High-Yield Cultivation Techniques for Rice under Controlled Irrigation Conditions. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China, 2014. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Shao, D.; Li, S.; Wang, B. Response of Rice Water Requirement to Groundwater Depths and Irrigations Simulation in Cold Region of Northeast China. J. Irrig. Drain. 2020, 38, 68–77, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Fu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X. Effect of Straw Mulching Mode on Maize Physiological Index and Water Use Efficiency. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 181–186, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X. Study on the Technology of Water-Saving and Yield-Increasing of Rice in Cold Field. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2010. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Nie, T. Study on water- saving high yield and high efficiency of rice in cold region by orthogonal design. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2015, 46, 22–27+46, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, P.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, H. Study on Comprehensive Water Saving Technology of Rice in Western Heilongjiang Province. Heilongjiang Agric. Sci. 2019, 4, 1–5, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yu, K.; Ge, X.; Chi, L.; Fan, J. Effects of Different Returning Methods of Straw on Soil Physical Property, Yield of Corn. J. Maize Sci. 2018, 26, 78–84, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, Q. Study on corn laminating spray irrigation experiment in western sandy soil region of Heilongjiang. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2010, 41, 57–60, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Effects of Different Irrigations on Carbon Emission, Water Consumption and Yield of Paddy Field in Cold Regions. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 1–7, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Experimental study on coupling effect of water and nitrogen of rice in cold black soil region. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2015, 46, 49–55, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Kong, F. Relationship between Trace Greenhouse Gas Emission and Water and Nitrogen Utilization under Water Biochar Management in Paddy Fields. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 379–387, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. The Experimental Study on Furrow Irrigation Pattern of Corn in Semi-Arid Region of Western Heilongjiang Province. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2011. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Sun, A.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Du, P. Effects of Different Water-saving Irrigation Modes on Rice Tillering, Height and Yield in Cold Area. Water Sav. Irrig. 2013, 12, 16–19, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Du, P. Experiment on Regulation of Water Consumption and Water Use Efficiency of Film lrrigation Rice in Cold Region. J. Irrig. Drain. 2011, 30, 97–99, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).