Abstract

The germination rate of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seeds is a key indicator of their vitality, which is complexly regulated by genetic and environmental factors. This study aims to elucidate the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the differences in germination rates among different pepper germplasm resources and identify the key genes regulating this trait. Three representative pepper materials (‘22HL6’, ‘22HL14’, ‘22HL2’) with significantly different germination rates were selected for this study. Key physiological and biochemical parameters during their germination process were systematically evaluated, including germination rate, vigor index, water absorption characteristics, amylase activity, antioxidant enzyme activity, and soluble sugar and protein content. Based on this, candidate genes related to germination rate were screened through transcriptome sequencing, and core candidate genes were preliminarily functionally validated using the Arabidopsis thaliana heterologous overexpression system. Materials with fast germination rates (‘22HL6’, ‘22HL14’) exhibited higher water absorption efficiency, amylase activity, antioxidant protection (such as lower MDA content and higher POD activity), and more active material metabolism (soluble sugar and protein) during the critical 72-h period. Transcriptome analysis successfully identified seven candidate genes closely related to germination rate. Among them, gene Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 had extremely high expression levels in fast-germinating materials but was almost not expressed in slow-germinating materials, and was identified as a core candidate gene. Heterologous overexpression of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 in A. thaliana significantly promoted seed germination, with transgenic lines exhibiting earlier germination initiation, more developed taproot and lateral root systems, larger rosette diameter, and earlier bolting and flowering compared to wild-type plants. This study reveals the basis for the differences in germination rates of pepper seeds from the physiological and biochemical to molecular mechanism levels, and for the first time links the function of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 gene to promoting seed germination and early seedling development. This gene provides valuable genetic resources for improving the germination uniformity and seedling vitality of pepper and even other crops through molecular breeding in the future.

1. Introduction

Seeds are the unique reproductive structures of seed-bearing plants, developed through a complete sexual reproduction process that includes flowering, pollination, and fertilization. They not only carry the genetic information of the parent plant but also serve as the origin of progeny and the onset of new plant development. Seeds thus play a pivotal transitional role in the plant life cycle [1,2,3]. Among seed traits, germination speed is a key indicator of seed vigor, governed by the complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors [4]. Genetic determinants define the inherent potential for germination, while environmental conditions influence the degree to which this potential is realized. Seed vigor is generally considered to be highly heritable, allowing parent plants to transmit traits such as germination speed to their offspring [5,6].

The internal determinants of seed germination speed are primarily associated with intrinsic seed characteristics. These include genetic background, seed size, degree of maturation, seed coat thickness and structure, color, and biochemical composition. Together, these factors modulate germination potential through integrated regulatory networks [7,8]. Among them, endogenous plant hormones are central to the regulation of seed dormancy and germination. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the interactions among hormones such as auxin (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellic acids (GAs), and cytokinins (CTKs) play critical roles in maintaining dormancy and promoting germination [9].

Pepper cultivation generally relies on seedlings and exhibits a longer germination period compared to other vegetable crops [10]. Low seed viability causes reduced germination, delay, heterogeneous seedling establishment, and decreased survival during seedling transportation [11]. Oti et al. found that Neem (Azadirachta indica) and Shea butter (Vitellaria paradoxa) have inhibitory effects on the germination and growth of pepper seeds [12]. X-rays, exogenous salicylic acid application, and 24-epibrassinolide pretreatment have also been proven to promote pepper seed germination [13,14,15]. Wei et al. that using melatonin solution could induce the germination and growth of Chaotian pepper seeds under drought stress [16].

Through genome-wide and expression analysis of the pepper B-box gene family, Ma et al. found that CaBBX19 may play an important role in seed morphogenesis and development [17]. Functional studies using the WRKY6 mutant have revealed that ABA regulates seed germination and early seedling growth in A. thaliana through its interaction with PHO1 and WRKY6 [18]. The AtRALFL32 gene in A. thaliana encodes the signaling peptide RALFL32, which participates in ABA-mediated control of germination under stress conditions [19]. Similarly, AtDGA1 encodes a protein kinase that plays a role in ABA signaling; ABA interferes with signal transmission by facilitating the binding of ABI4 to DGA1, thereby affecting chlorophyll biosynthesis and contributing to ABA-mediated regulation of seed germination and photomorphogenesis [20]. Clerkx et al. employed recombinant inbred lines (RILs) of A. thaliana to identify QTLs associated with seed vigor traits such as germination speed and rate [21]. The FLOE1 gene encodes the FLOE1 protein, which undergoes specific dissociation during seed imbibition, enabling the embryo to perceive external water potential signals and initiate germination under favorable conditions [22]. Bewley et al. demonstrated that GAs promote germination via GA signaling pathway genes such as SLY1 and GID1 [23]. Ethylene-induced overexpression of MADS26 in A. thaliana has also been shown to enhance germination capacity. Furthermore, methionine synthase 1 (AtMS1) is responsible for L-methionine (L-Met) biosynthesis, which in turn facilitates germination by upregulating AtGLR3.5-mediated calcium signaling, thereby counteracting ABA inhibition [24]. The gene AtGSTU7, encoding glutathione S-transferase U7 (GSTU7), contributes to ABA-regulated germination by modulating the balance between reduced glutathione (GSH) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [25].

Wu et al. reported that the OsGA20ox1 gene in rice (Oryza sativa) seeds influences germination speed by regulating gibberellin biosynthesis [26]. Additionally, the OsMADS29 gene modulates α-amylase activity through the ABA signaling pathway, thereby facilitating endosperm starch degradation and participating in the germination process [27]. The OsMybcc-1 gene regulates α-amylase expression via the gibberellin signaling pathway, accelerating the mobilization of seed storage reserves and ultimately promoting both germination and seedling morphogenesis [28]. The OsHXK9 gene encodes hexokinase HXK9, which contributes to early seed germination by modulating ROS levels during the germination phase [29]. Yu et al. highlighted the role of ABI5, a key transcription factor within the ABA signaling cascade, in regulating dormancy, germination, vegetative growth, and flowering time [30]. The SOMNUS gene acts as a crucial dormancy-promoting regulator by activating ABA biosynthetic genes and repressing gibberellin biosynthetic genes [31]. Li et al. demonstrated that the OsOMT gene primarily affects seed vigor through modulation of amino acid concentrations, sugar metabolism, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [32]. Zhai et al. found that overexpression of ZmMYB59 in maize (Zea mays) suppresses gibberellin and cytokinin biosynthesis while significantly enhancing ABA biosynthesis, thus playing a negative regulatory role in seed germination [33]. Fujino et al. identified the tissue-specific expression of qLTG3-1 during maize seed germination, particularly in the aleurone layer of the seed coat and the upper embryo layer overlying the coleoptile. This gene is hypothesized to promote cell vacuolization and tissue loosening, enhancing seed vigor under low-temperature conditions [34]. In tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), the recently characterized gene MAPK11 was found to phosphorylate SnRKs, thereby influencing ABA signal transduction and affecting seed germination [35]. Overexpression of NcEXPA8, which encodes an expansion protein from Neolamarckia cadamba, significantly accelerated seed germination in Arabidopsis, enhanced gibberellin sensitivity, and reduced ABA sensitivity [36]. Similarly, heterologous overexpression of the cytokinin receptor gene GhCRE1 from upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) in Arabidopsis positively regulated germination initiation and significantly increased the germination rate [37,38].

This study aims to investigate the physiological mechanisms underlying differences in seed germination rates among various Capsicum genotypes, identify and clone key genes associated with germination speed, and analyze their functional roles. The ultimate goal is to facilitate the breeding of Capsicum cultivars with optimized germination profiles, promoting uniform seedling emergence. These findings are expected to contribute to improved seed propagation strategies, scientifically guided seedling cultivation, and enhanced crop management practices in modern agricultural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

A total of 15 Capsicum annuum germplasm accessions were used in this study. These were provided by Xiangyan Seed Industry Co., Ltd. (Peppera Seed), Changsha, China. Based on a comprehensive consideration of data results and literature findings (Table S1), three representative accessions—‘22HL14’ (abbreviated as H14), ‘22HL6’ (H6), and ‘22HL2’ (L2)—were selected as the primary materials for detailed physiological and transcriptomic analysis.

2.2. Physiological and Biochemical Index Determination

The germination test of pepper seeds was conducted using the Petri dish filter paper method. The seeds were disinfected with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, rinsed with distilled water three times, and the surface moisture was absorbed. Each Petri dish was lined with two layers of moist filter paper, and 100 seeds were placed inside, with three replicates. The seeds were cultured in the dark at 28 °C, and the filter paper was regularly replenished with water to keep it moist. The germination was assessed based on the emergence of the radicle through the seed coat (seedling emergence). The number of germinated seeds was recorded daily, and on the seventh day, the root length was measured, and the germination rate (number of germinated seeds/total number of seeds × 100%) and germination index (GI = Σ(Gt/Dt), where Gt represents the number of seeds that have sprouted on day t and Dt denotes the corresponding number of days. Additionally, seeds of each variety were soaked in room temperature water, wiped dry with filter paper at 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, and weighed (100 seeds per measurement, accurate to 0.0001 g) until they reached saturation to determine the water absorption capacity.

Among the samples used to determine the water absorption capacity of seeds, samples collected at five different time points (0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h) were selected for measuring the activities of α-amylase and β-amylase, as well as the contents of soluble sugar and soluble protein. Three replicates were set up for each measurement. The activities of α-amylase and β-amylase, as well as the contents of soluble sugar and soluble protein, were determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method, anthrone colorimetric method, and Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining method, respectively.

Samples were taken at 24 h and 72 h after seed imbibition, with three biological replicates for each time point. The thiobarbituric acid colorimetric method, guaiacol method, and nitroblue tetrazolium method were used to measure malondialdehyde (MDA) content, peroxidase (POD) activity, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, respectively.

The experimental data were statistically analyzed, processed, and charted using Excel 2016, IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0, and GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software. Significant differences were tested overall using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and multiple comparisons were conducted using the Waller-Duncan test (significance level α = 0.05).

2.3. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

A germination test was performed using the Petri dish filter paper method. Seeds of H14, H6, and L2 were surface-sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, rinsed three times with sterile distilled water (ddH2O), and then dried on sterile filter paper. Two layers of moistened filter paper were placed in 9-cm sterile Petri dishes, and 50 seeds per accession were evenly distributed in each dish. Three biological replicates were set up for each accession. The dishes were incubated in the dark at 28 °C in a constant-temperature incubator, with water added regularly to maintain consistent moisture levels. Tissue samples were collected at two developmental stages: 24 h after imbibition (designated as Stage I) and 72 h after imbibition (Stage II). For each time point, three biological replicates were collected. The samples were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction, transcriptome sequencing, and qRT–PCR validation.

Total RNA was extracted using a modified TRIzol method developed in our laboratory. RNA integrity was confirmed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Purity (OD260/OD280 ratio) and concentration were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA samples that met the quality criteria were stored at −80 °C. Library construction was performed using qualified RNA samples, and transcriptome sequencing was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform by Biomarker Technologies Corporation (Beijing, China) [39].

2.4. Transcriptome Data Assembly, Functional Annotation, and Classification

Raw sequencing reads underwent stringent quality control. First, adapter sequences were removed. Next, reads containing more than 10% undetermined bases (n) were filtered out. Lastly, low-quality reads—those in which more than 50% of bases had a Q-score < 10—were discarded. The resulting high-quality clean reads were aligned to the C. annuum reference genome (Capsicum_annuum. Ca_59.genome.fa) using HISAT2. Successfully aligned reads were assembled into transcripts using StringTie (v 2.2.3) and subjected to downstream analyses, including differential gene expression and functional annotation.

To assess reproducibility among replicates, PCA and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) were employed. PCA reduces multidimensional gene expression data into principal components and clusters samples based on expression similarity.

2.5. Screening and Functional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 package (v1.48.1). Genes with a fold change ≥ 2 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 were designated as DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using appropriate R packages to identify biological processes and pathways significantly associated with the DEGs. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to explore gene expression variation and clustering among samples, and the results were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R. Expression levels of unigenes were calculated using the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) method. The FPKM formula is:

In the formula, cDNA Fragments represents the number of fragments aligned to a specific transcript; Mapped Fragments (Millions) indicates the total number of fragments mapped to all transcripts; Transcript Length (kb) is the length of the corresponding transcript in kilobases.

2.6. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was performed using the R software (v1.0) and the WGCNA package on the BMKCloud platform (www.biocloud.net. date: 17 October 2024). The minimum expression threshold for genes was set to 1. The module similarity threshold was set to 0.25, and the minimum module size was defined as 30 genes. Biological replicates were merged to enhance the accuracy of network construction and ensure reliable classification of gene modules. The primary objective was to identify highly correlated gene modules and investigate their relationships with seed germination speed [40].

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT–PCR)

To validate the transcriptome data, six candidate genes were randomly selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT–PCR). Each gene was assessed using three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Gene-specific primers were designed using the Primer-BLAST tool (v 2.17.0) available on the NCBI website and synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The Actin gene was used as an internal reference.

Total RNA was extracted from pepper seeds at different germination stages using the TRIzol method. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the HiScript® II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA Wiper; Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Synthesized cDNA was stored at −20 °C until further use. qRT–PCR reactions were conducted using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) in a 10 μL reaction volume. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, normalized to the internal reference gene. Statistical comparisons between qRT–PCR results and transcriptome data were performed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

2.8. Target Gene Sequence Acquisition and Cloning

The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from the NCBI database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi accessed on 1 October 2025) was used to identify homologous protein sequences of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 in tomato, potato, and other related species. The corresponding amino acid sequences were retrieved and downloaded.

Primers (Table S2) were designed based on the target gene sequence using SnapGene (v8.0.3). Gene amplification was conducted using Phanta® Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), with all operations performed on ice to preserve enzyme activity. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the PCR system was prepared by adding high-fidelity polymerase, forward and reverse primers, template cDNA, and ddH2O in sequence, to a final reaction volume of 25 μL. PCR amplification products were resolved by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The band corresponding to the target gene was excised and purified using a 2.0 mL centrifuge tube.

2.9. Construction of Overexpression Vector

The coding sequence (CDS) of the target gene and the vector pCAMBIA1300S were loaded into SnapGene (v8.0.3) for in silico cloning. Specific primers with suitable restriction sites were designed based on the vector sequence. The target gene was ligated into the pCAMBIA1300S vector and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. Colony PCR was performed to identify positive clones, which were then verified by sequencing. Confirmed recombinant clones were used for plasmid DNA extraction. The purified recombinant plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Successfully transformed cultures were preserved in 20% glycerol at −80 °C. Transformation of A. thaliana was carried out using the floral dip method mediated by A. tumefaciens. Transgenic seedlings were selected on 1/2 MS medium containing kanamycin, followed by PCR and qRT–PCR to confirm gene integration and expression.

2.10. Genetic Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana

Wild-type A. thaliana Col-0 seedlings were transplanted into sterile soil and grown in a climate chamber until bolting. Primary inflorescences were removed to promote axillary formation. After secondary inflorescences initiated bolting, plants were watered before transformation. Agrobacterium tumefaciens glycerol stock was cultured in YEP medium with antibiotics to OD600 ≈ 0.8, diluted, and grown to OD600 = 0.6. The suspension was centrifuged, washed, and adjusted to OD600 = 0.4 in infection buffer with sucrose and Silwet L-77. Selected plants had inflorescences dipped in the solution for 15 s, covered with humidity, and incubated in the dark for 24 h. Dipping was repeated once or twice. After silique maturation, T1 seeds were harvested, sterilized, and sown on kanamycin-MS medium. Resistant seedlings were transplanted, and RNA was extracted for PCR and qRT-PCR to confirm transgene negation and expression.

3. Results

3.1. Early Physiological and Biochemical Parameters

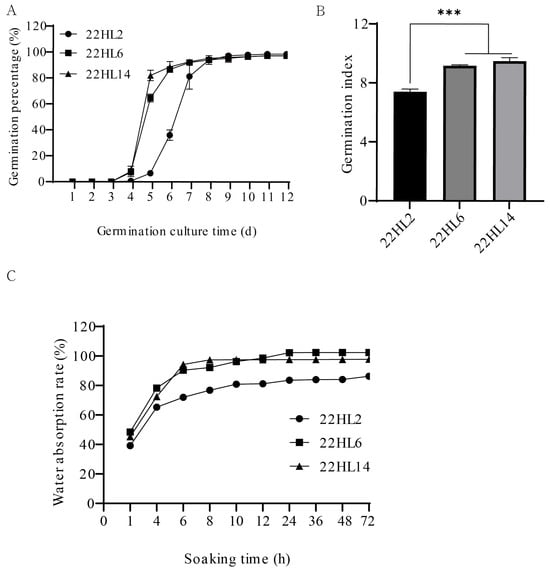

During the 72-h germination culture period, significant differences in germination speed were observed among the varieties (Figure 1A,B). ‘22HL6’ and ‘22HL14’ began to germinate on the third day, whereas ‘22HL2’ did not germinate. By the fourth day, the germination rates of ‘22HL14’ and ‘22HL6’ reached 86.00% and 70.66%, respectively, which were significantly higher than that of ‘22HL2’ (8.00%). The germination index of ‘22HL14’ was 1.35 times that of ‘22HL2’. This indicates that the germination speed and ability of ‘22HL6’ and ‘22HL14’ are stronger than that of ‘22HL2’, and 72 h is the critical period for the difference.

Figure 1.

Physiological indicators related to seed germination. (A): Germination percentage of three pepper varieties; (B): Germination index of three pepper varieties (***: p ≤ 0.001); (C): Water absorption of seeds of three pepper varieties.

The water absorption process of seeds follows an “S” curve (Figure 1C), which is divided into three stages: rapid (0–6 h), slow (6–24 h), and gradual (24–72 h). During the rapid water absorption stage, the water absorption of both ‘22HL14’ and ‘22HL6’ increases faster than that of ‘22HL2’.

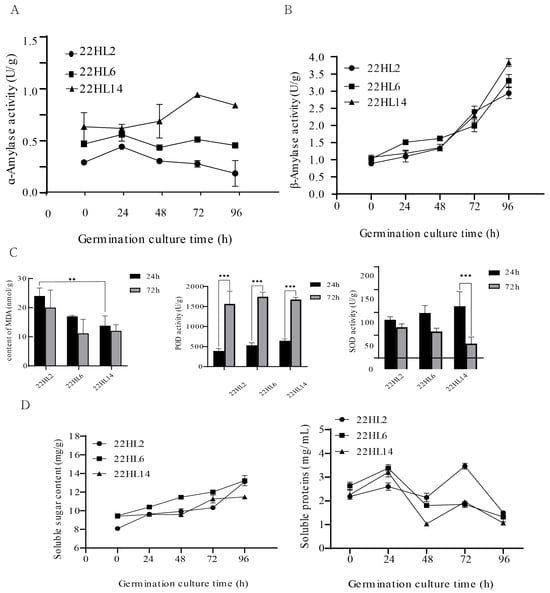

The analysis of amylase activity (Figure 2A,B) revealed that from 24 to 72 h, the α-amylase activity of ‘22HL14’ continuously increased, whereas that of ‘22HL2’ decreased. By 96 h, the α-amylase activity of the variety with faster germination was ultimately higher than that of ‘22HL2’, indicating a positive correlation between enzyme activity and germination speed.

Figure 2.

Physiological indicators related to seed germination. (A,B): Changes in amylase activity in seeds of three pepper varieties; (C): MDA content and antioxidant enzyme activity in seeds of three pepper varieties (**: p ≤ 0.01, ***: p ≤ 0.001); (D): Soluble sugar and soluble protein contents of seeds of three pepper varieties.

In terms of physiological metabolism (Figure 2C), varieties with rapid germination (‘22HL14’, ‘22HL6’) exhibited lower malondialdehyde (MDA) content overall, indicating less oxidative damage to cell membrane lipids. Simultaneously, their peroxidase (POD) activity was higher at 72 h, aiding in maintaining the integrity of the cell membrane. However, the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) decreased during the germination process in varieties with rapid germination (‘22HL6’ and ‘22HL14’ decreased by 18.1% and 68.7%, respectively), potentially indicating that their reactive oxygen species clearance task had been completed in stages.

The results of substance metabolism (Figure 2D) indicate that varieties with rapid germination (‘22HL14’, ‘22HL6’) exhibit higher soluble sugar content at 72 h, providing ample energy for germination. The soluble protein content exhibits a bimodal variation between 0 and 96 h, but the peak time of protein content in varieties with rapid germination occurs earlier than in ‘22HL2’, indicating that their protein metabolism is more rapid and can provide a material basis for embryo growth earlier.

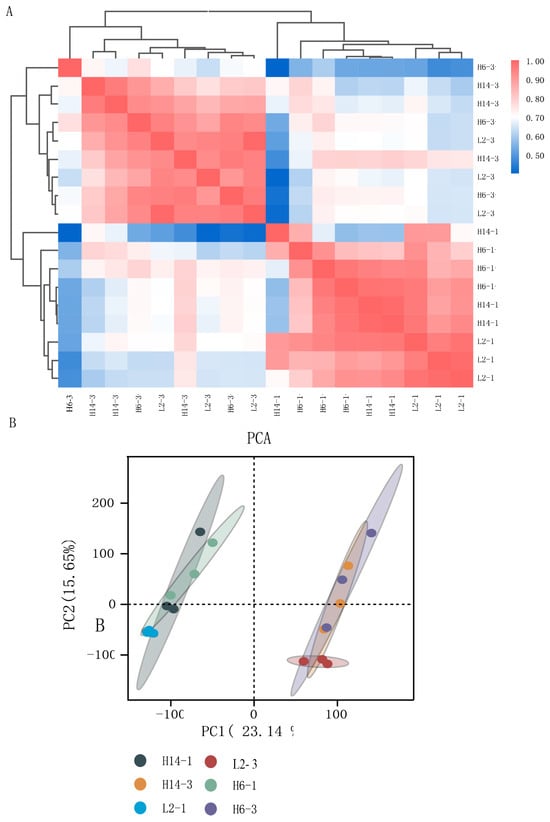

3.2. Transcriptome Data Quality Analysis

The PCA plot revealed strong clustering of biological replicates, particularly among samples collected at the same time point, with L2 showing the highest internal consistency. Pearson correlation coefficients were also calculated and visualized as a heatmap (Figure 3A,B). High r2 values indicated excellent repeatability, confirming the reliability of the transcriptome data.

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis between samples. (A) Hierarchical clustering heatmap showing sample-to-sample distances based on gene expression profiles. Red indicates higher correlation, blue indicates lower correlation; (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) showing clear separation of samples by stage and genotype, with strong clustering of biological replicates.

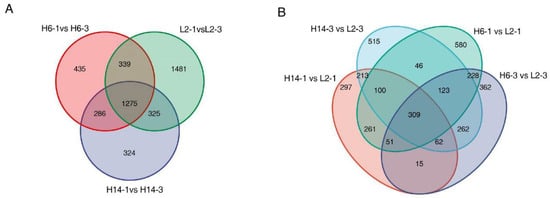

3.3. Analysis of DEGs

To identify genes associated with differences in seed germination speed among pepper varieties, comparative analyses were conducted between different germination stages and within the same germination stage across three varieties with distinct germination rates: ‘22HL6’ (H6, fast-germinating type), ‘22HL14’ (H14, fast-germinating type), and ‘22HL2’ (L2, slow-germinating type). The analysis of different germination stages (Figure 4A) showed that 2335 DEGs were identified between H6-1 and H6-3, including 1583 upregulated and 752 downregulated genes. Between H14-1 and H14-3, 2,210 DEGs were detected, comprising 1479 upregulated and 731 downregulated genes. For L2-1 and L2-3, a total of 3420 DEGs were identified, of which 2240 were upregulated and 1180 were downregulated.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of 22HL6, 22HL14 and 22HL2 during germination. (A): DEGs identified across different germination stages within each genotype (H6, H14, and L2); (B): DEGs identified from comparisons between genotypes at the same germination stage (24 h and 72 h).

An analysis of 1275 core DEGs shared among the three varieties across both germination stages was performed. Among them, H14 and L2 shared 1600 DEGs, which was similar to the 1614 DEGs shared between H6 and L2. A further comparison of DEGs between H14 and L2, and between H6 and L2 at the same germination stage (Figure 4B), revealed that 684 DEGs were common to H14 and L2 across both stages, while 711 DEGs were common to H6 and L2, indicating a high degree of genetic similarity between varieties. The intersection of DEGs common to both time points yielded a core gene set of 309 DEGs that showed significant expression differences at both germination stages.

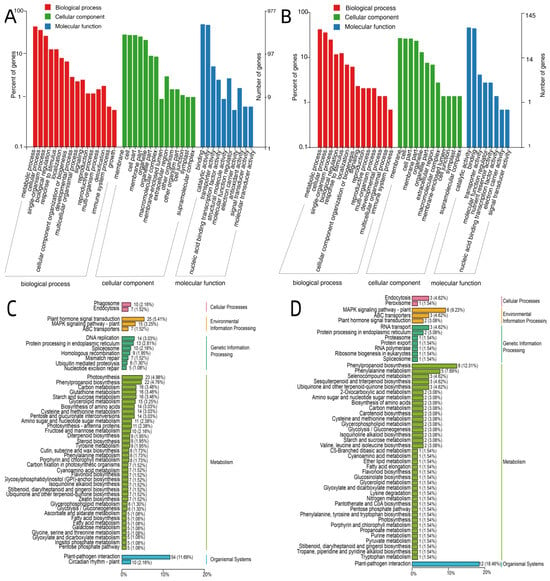

3.4. GO Enrichment Analysis and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

To further elucidate changes in gene function during different stages of seed germination, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted on the 1275 DEGs shared across the three stage-based comparison groups (H14-1 vs. H14-3, H6-1 vs. H6-3, and L2-1 vs. L2-3), using the GO database (Figure 5A,B). A total of 977 DEGs were successfully annotated and enriched in GO terms, which were categorized into three main GO domains comprising 40 functional terms: Biological Process, Cellular Component, and Molecular Function.

Figure 5.

GO enrichment analysis (A,B) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (C,D) of differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

As shown in Figure 2A, 16 GO terms were enriched in the Biological Process category, primarily involving metabolic process, cellular process, and single-organism process. Physiological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and signal transduction were also actively represented. In the Cellular Component category, 14 GO terms were enriched, with key associations including membrane, cell, cell part, and membrane part. In the Molecular Function category, 10 GO terms were enriched, primarily encompassing binding activity, catalytic activity, and transporter activity.

GO enrichment analysis was also performed on the 309 DEGs shared across four variety-based comparison groups at the same germination stage (H14-1 vs. L2-1, H14-3 vs. L2-3, H6-1 vs. L2-1, H6-3 vs. L2-3) Of these, 145 DEGs were successfully enriched and classified into three major GO domains and 34 functional terms. As shown in Figure 3B, the functional categories were similar to those identified across different germination stages, with minor variations in the number of enriched terms. Specifically, 14 GO terms were enriched in the Biological Process category, 12 in the Cellular Component category, and 8 in the Molecular Function category.

To gain further insights into the biological pathways involved in seed germination, KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted on the 1275 DEGs shared by the three stage-based comparison groups (H14-1 vs. H14-3, H6-1 vs. H6-3, and L2-1 vs. L2-3). Based on KEGG pathway annotations and enrichment filtering, a total of 462 functional genes were identified and grouped into five major categories and 18 subcategories (Figure 5C). These genes were primarily involved in pathways related to plant–pathogen interaction, plant hormone signal transduction, the MAPK signaling pathway–plant, DNA replication, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Enriched metabolic pathways included carbon metabolism, glutathione metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, and amino acid biosynthesis and degradation.

To investigate regulatory differences associated with genetic background, KEGG enrichment analysis was also performed on the 309 DEGs shared across four genotype-based comparison groups during germination (H14-1 vs. L2-1, H14-3 vs. L2-3, H6-1 vs. L2-1, H6-3 vs. L2-3) A total of 65 genes were annotated and enriched into five major KEGG categories and 17 subcategories (Figure 5D). These genes were predominantly associated with pathways such as plant–pathogen interaction, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, phenylalanine metabolism, the MAPK signaling pathway–plant, ABC transporters, RNA transport, and selenocompound metabolism.

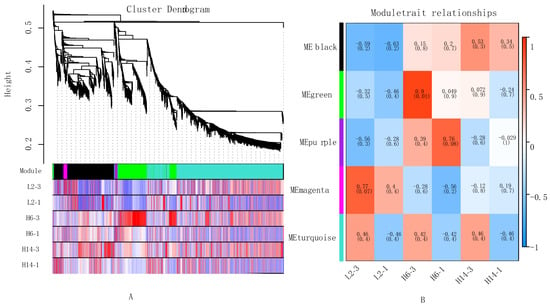

3.5. WGCNA

To further investigate the functional relationships and regulatory networks among genes involved in pepper seed germination, a weighted gene co-expression network was constructed using 1886 rigorously selected DEGs. Clustering analysis based on the FPKM values of these genes grouped those with similar expression patterns into the same module. In the resulting dendrogram, distinct branches represented different gene co-expression modules, each marked by a unique color (Figure 6A). A total of five modules were identified: black, green, purple, magenta, and turquoise. A heatmap of module–sample correlations was generated, and subsequent module–trait association analysis (Figure 6B) revealed that gene expression patterns in the black module were positively correlated with germination speed in H14 and H6 but negatively correlated in L2.

Figure 6.

Result of gene co-expression network analysis map. (A) Gene clustering tree and module partitioning; (B) Moduletrait relationships heatmap.

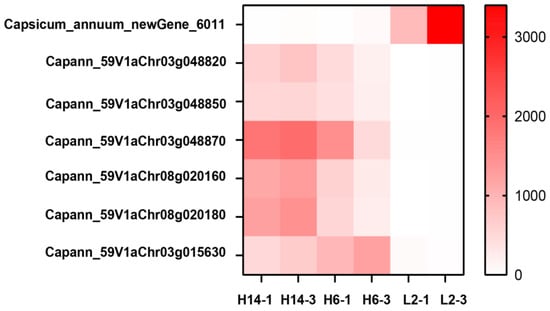

3.6. Candidate Gene Screening

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs from both key germination stages (24 h and 72 h) across the three materials (22HL14, 22HL6, and 22HL2), as well as the module analysis via WGCNA, consistently identified enrichment in pathways such as plant–pathogen interaction, plant hormone signal transduction, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. At 72 h, seeds of 22HL14 and 22HL6 showed radicle emergence earlier than those of 22HL2, marking a critical transition phase from dormancy to germination and a key point of divergence in germination speed.

In our study, at the 72 h stage, seeds of 22HL14 and 22HL6 had already broken dormancy and initiated germination, unlike those of 22HL2. Among the 1275 DEGs shared across the three materials, 26 genes were found to be associated with ABA and GA biosynthesis or signaling. Of these, 14 were related to ABA synthesis or signal activation. The ABA receptor gene PYL1 (Capann_59V1aChr06g019190) was upregulated, whereas the gene encoding an ABA- and environmental stress-induced protein (Capann_59V1aChr02g028900) was downregulated. Additionally, the ABA-insensitive protein gene Capann_59V1aChr04g005840 was upregulated, suggesting a possible downregulation of the ABA signaling pathway during germination. In contrast, 12 genes related to GA biosynthesis and signaling were identified, including six that were upregulated and one that was downregulated. The GA2ox-related genes (Capsicum_annuum_newGene_22409 and Capann_59V1aChr05g000600) and the GA3ox gene Capann_59V1aChr06g013890 were upregulated. Meanwhile, the GA13ox-related gene Capann_59V1aChr01g040280 and the GA20ox gene Capann_59V1aChr03g024430 were downregulated. These results indicate that at 72 h, a decline in ABA levels and a concomitant increase in GA biosynthetic gene expression lead to a reduced ABA/GA ratio, thus facilitating dormancy release and promoting germination.

Additionally, expression levels and functional annotations of the 309 DEGs shared across four comparison groups (H14-1 vs. L2-1, H14-3 vs. L2-3, H6-1 vs. L2-1, and H6-3 vs. L2-3) were analyzed (Figure 7). Seven genes exhibiting significant differential expression were identified. Notably, Capsicum_annuum_newGene_6011 was highly expressed in L2, with expression levels exceeding 100-fold higher than in H6 and H14. Conversely, Capann_59V1aChr03g048820, Capann_59V1aChr03g048850, Capann_59V1aChr03g048870, Capann_59V1aChr08g020160, Capann_59V1aChr08g020180, and Capann_59V1aChr03g015630 were highly expressed in H6 and H14, with expression levels more than 100-fold greater than in L2. Integrating DEG expression patterns, annotation data, and prior literature, Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 was selected as the key candidate gene for further functional validation.

Figure 7.

FPKM values of differential genes related to germination rate.

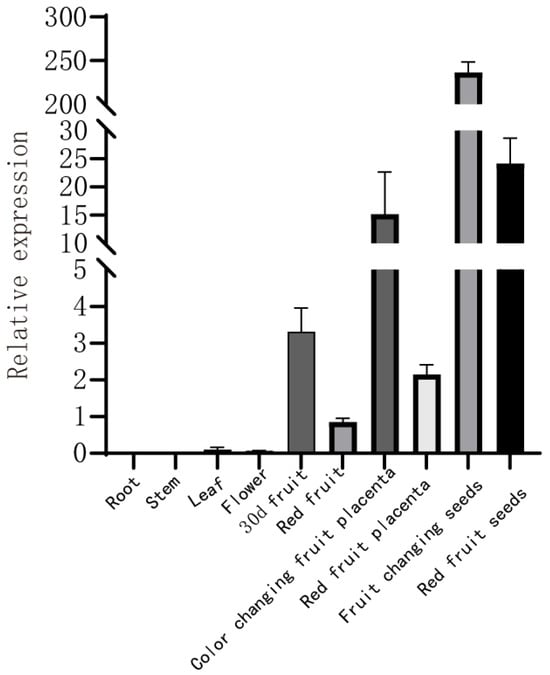

3.7. Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis

To investigate the tissue-specific expression pattern of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850, qRT–PCR analysis was performed using various tissues of ‘22HL14’ pepper plants. These included roots, stems, leaves, flowers, 30-day-old fruits, red fruits, placenta at the color transition stage, placenta at the red fruit stage, seeds at the color transition stage, and seeds at the red fruit stage (Figure 8). The results showed that Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 was most highly expressed in seeds at the color transition stage. In contrast, expression was relatively low in red fruit seeds and placenta, as well as in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and mature fruit, indicating its developmental specificity and potential role during early germination.

Figure 8.

Tissue-specific expression analysis of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850.

3.8. Phenotypic Analysis of Transgenic Arabidopsis Overexpressing the Gene

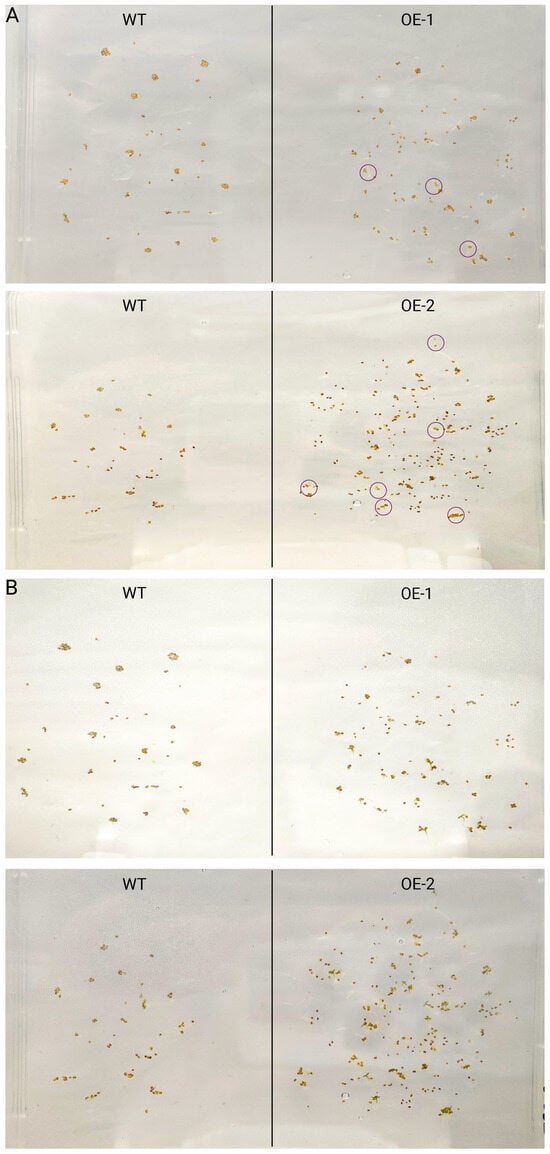

After two generations of selection on 1/2 MS medium containing kanamycin, homozygous T3 transgenic A. thaliana lines overexpressing Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 (OE) were successfully obtained. Both transgenic and wild-type (WT) seeds were surface-sterilized and sown on 1/2 MS medium to monitor germination behavior. After 2 days of cultivation, OE seeds germinated earlier than WT seeds (Figure 9), indicating that overexpression of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 in Arabidopsis can enhance germination speed.

Figure 9.

Phenotypic analysis of transgenic A. thaliana seeds. (A) Germination phenotype of Arabidopsis wild-type (WT) and overexpressed (OE) seeds in MS medium for 48 h. (B) Germination phenotype of Arabidopsis wild-type (WT) and overexpressed (OE) seeds in MS medium for 72 h.

4. Discussion

This study provides an integrated physiological and molecular perspective on the variation in germination speed among pepper (Capsicum annuum) accessions. Our findings confirm that seeds with faster germination rates exhibit enhanced physiological performance, characterized by more efficient water uptake, elevated activities of key hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., α-amylase, β-amylase) and antioxidant enzymes, and higher concentrations of soluble sugars and proteins [41,42,43,44]. These characteristics collectively facilitate rapid metabolic activation, efficient mobilization of stored reserves, and robust protection against oxidative stress, as indicated by lower malondialdehyde (MDA) content, thereby creating an optimal internal environment for rapid radicle protrusion [45].

At the molecular level, transcriptomic analysis identified a core set of 309 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) shared among accessions with contrasting germination speeds. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these core DEGs are significantly involved in critical pathways including plant hormone signal transduction, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and ABC transporters. The enrichment in plant hormone signaling, particularly the antagonistic relationship between gibberellin (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA), underscores the pivotal role of hormonal balance in initiating and sustaining the germination process [46]. Furthermore, the involvement of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis suggests contributions to cell wall fortification and antioxidant defense, while cysteine and methionine metabolism highlights the importance of amino acid supply and redox homeostasis [47,48]. The prominence of ABC transporters and RNA transport pathways further emphasizes the critical need for precise intracellular substance exchange and gene expression regulation during germination [49].

Among the core DEGs, the gene Capann59v1achr03g048850 was identified as a strong candidate gene influencing germination speed. Its annotation as a cold and drought regulatory protein coding gene suggests a potential role in stress response mechanisms during germination. This functional prediction is supported by previous studies on orthologs; for instance, overexpression of the SbCDR gene from Salicornia brachiatain tobacco significantly enhanced abiotic stress tolerance and improved seed germination rate, which was associated with reduced MDA levels, increased accumulation of osmoprotectants like proline, and enhanced expression of ROS-scavenging genes [50]. Similarly, the CcCDR gene from pigeon pea, when overexpressed in A. thaliana, conferred enhanced tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses and functioned as a transcriptional activator within the ABA signaling pathway, increasing sensitivity to ABA and modulating stress-responsive gene expression [51]. Therefore, we hypothesize that Capann59v1achr03g048850 may similarly regulate pepper seed germination speed by enhancing stress resilience, potentially through modulating ABA signaling and ROS scavenging capabilities, thus ensuring a cellular environment conducive to rapid germination [52,53].

The significant enrichment of the plant-pathogen interaction pathway among the DEGs suggests that these genes may also contribute to bolstering defense mechanisms during the critical germination phase, indirectly promoting seed vigor and speed. Additionally, the enrichment of genes related to cytoskeleton and organelle function underscores the importance of maintaining cellular architecture and enabling successful germination [54].

When contextualized with existing literature, our findings are consistent with the established model that rapid germination is a complex trait governed by the coordinated operation of physiological processes and molecular networks [55,56]. The identification of the core DEG set and the specific pathways provides a more detailed molecular landscape underlying this coordination. The association of a CDR-like gene with germination speed offers a novel insight, suggesting that genetic components conferring general abiotic stress tolerance may be intrinsically linked to the efficiency of the germination process itself in pepper.

A limitation of this study is that the functional role of the candidate gene, Capann59v1achr03g048850, and the other core DEGs, is primarily based on predictive functional annotation and expression correlation. Future work should include functional validation experiments, such as genetic transformation or gene editing, to definitively confirm the causal relationship between these genes and germination phenotypes. Furthermore, detailed investigation into the temporal dynamics of hormone levels and the specific regulatory networks interacting with these genes would provide a deeper understanding of the sequential regulatory events.

5. Conclusions

This study, by evaluating the germination characteristics of three Capsicum annuum accessions with contrasting germination speeds, preliminarily elucidated the associated physiological and biochemical mechanisms. RNA-seq analysis identified 309 core differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Through integrated analysis including GO and KEGG enrichment, WGCNA, and phenotypic traits, seven key genes were prioritized, with Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 emerging as the most promising candidate based on its significant expression differences and literature support.

Transcriptome data revealed high expression of Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 in fast-germinating lines but nearly undetectable levels in the slow-germinating line. Tissue-specific qRT–PCR further confirmed its predominant expression in seeds, particularly during fruit color transition. Functional validation via heterologous overexpression in A. thaliana demonstrated that Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 significantly promotes seed germination and enhances early seedling development, as evidenced by accelerated germination timing, advanced hypocotyl elongation, cotyledon expansion, and increased root length.

Overall, this study provides novel insights into the genetic basis of germination speed in pepper and identifies Capann_59V1aChr03g048850 as a key regulator. The findings lay a foundation for molecular breeding strategies aimed at improving seedling establishment and uniformity in Capsicum species, and it may enhance its early stress resistance in the field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122772/s1, Table S1: Protrusion rate of different pepper germplasms; Table S2: Primer sequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and L.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.H., J.Z., M.L., P.L. and L.O.; formal analysis, M.L. and P.L.; data curation M.L. and P.L.; visualization, J.Z.; funding acquisition, L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-24-A-05).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Table following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

References

- Bareke, T. Biology of seed development and germination physiology. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 2018, 8, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, M.W. Seed Ecology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumaraswamy, H.S.; Paul, D. Floral Biology and Pollination Systems for Hybrid Seed Production in Plants. In Hybrid Seed Production for Boosting Crop Yields: Applications, Challenges and Opportunities; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, E.; Ghaderi-Far, F.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Problems with using mean germination time to calculate rate of seed germination. Aust. J. Bot. 2015, 63, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.C.; Bradford, K.J.; Khanday, I. Seed germination and vigor: Ensuring crop sustainability in a changing climate. Heredity 2022, 128, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Debaeke, P.; Steinberg, C.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J.; Aubertot, J.N. Abiotic and biotic factors affecting crop seed germination and seedling emergence: A conceptual framework. Plant Soil 2018, 432, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrecher, T.; Leubner-Metzger, G. The biomechanics of seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Advances in the molecular regulation of seed germination in plants. Seed Biol. 2024, 3, e006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Lin, R. The role of light in regulating seed dormancy and germination. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 1310–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraf, E.A.; Al-madhagi, I.A. Comparing Effects of Priming Chili Pepper Seed with Different Plant Biostimulants, with Balancing Effects on Vegetative and Root Growths and Seedling Quality. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 1173–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Arin, L. Effect of Osmo-Priming in Naturally Aged Pepper Seeds. Agric. For. Aquac. Sci. 2025, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Oti, E.C.; Daramola, O.T. Allelopathic Effects of Azardiracta indica and Vitellaria paradoxa on the Germination and Growth of Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sahel J. Life Sci. FUDMA 2025, 3, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, A.; Pérez, M.; Steinbrecher, T.; Capozzi, F.; Kondrotas, K.; Zhang, L.; Spagnuolo, V.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Application of X-ray sorting and priming improves the germination performance of low-quality seed fractions of the Papaccella pepper landrace. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, T.O.; Iosob, G.A.; Brezeanu, C.; Brezeanu, P.M.; Bălăiță, C.; Calara, M.; Avasiloaiei, D.I. Assesment of various concentration of salicylic acid in tissue culture in vitro systems for their effect on modulating abiotic stress tolerance mechanisms in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants. Horticulture 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H. Effects of Different Seed Priming Agents for Enhancing Pepper Seed Germination, Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity Under Salt Stress. Seedl. Establ. Antioxid. Act. Salt Stress 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q.; Lin, X.; Liang, L.; Qin, Z.; Li, Y. Effects of Melatonin on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Chaotian Pepper Under Drought Stress. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 26, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Dai, J.X.; Liu, X.W.; Lin, D. Genome-wide and expression analysis of B-box gene family in pepper. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.R.; Haruta, M.; Moura, D.S. Twenty years of progress in physiological and biochemical investigation of RALF peptides. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Xu, Y. Research progress on the mechanism of GA and ABA during seed germination. Mol. Plant Breed. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Integration of ABA, GA, and light signaling in seed germination through the regulation of ABI5. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1000803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerkx, E.J.; Blankestijn-De Vries, H.; Ruys, G.J.; Groot, S.P.; Koornneef, M. Genetic differences in seed longevity of various Arabidopsis mutants. Physiol. Plant. 2004, 121, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorone, Y.; Boeynaems, S.; Flores, E.; Jin, B.; Hateley, S.; Bossi, F.; Lazarus, E.; Pennington, J.G.; Michiels, E.; De Decker, M.; et al. A prion-like protein regulator of seed germination undergoes hydration-dependent phase separation. Cell 2021, 184, 4284–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.; Hilhorst, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 23, p. 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Jing, Y.; Shi, P.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yan, J.; Chu, J.; Chen, K.-M.; Sun, J. JAZ proteins modulate seed germination through interaction with ABI 5 in bread wheat and Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Lu, J.; Xing, J.; Du, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses revealing the potential mechanism of seed germination in Polygonatum cyrtonema. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, C.; Pang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Xia, G.; Tian, Y.; He, C. OsLOL1, a C2C2--type zinc finger protein, interacts with O sb ZIP 58 to promote seed germination through the modulation of gibberellin biosynthesis in Oryza sativa. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.; Song, S.; Yin, Q.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; He, A.; Wang, W. Enhancement in seed priming-induced starch degradation of rice seed under chilling stress via GA-mediated α-amylase expression. Rice 2022, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaris, R.N.; Lin, Z.; Yang, P.; He, D. The rice alpha-amylase, conserved regulator of seed maturation and germination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Yu, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhuang, C. Hexokinase gene OsHXK1 positively regulates leaf senescence in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Q. Precise protein post-translational modifications modulate ABI5 activity. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, B.; Xu, J.; Peng, L.; Sun, S.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, X.; He, Y.; Wang, Z. A genome--wide association study reveals that the 2--oxoglutarate/malate translocator mediates seed vigor in rice. Plant J. 2021, 108, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, H.; Sun, C.; Ren, J. Overexpression of maize ZmMYB59 gene plays a negative regulatory role in seed germination in Nicotiana tabacum and Oryza sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 564665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujino, K.; Sekiguchi, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Ono, K.; Yano, M. Molecular identification of a major quantitative trait locus, qLTG3–1, controlling low-temperature germinability in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 12623–12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Shang, L.; Wang, X.; Xing, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Z. MAPK11 regulates seed germination and ABA signaling in tomato by phosphorylating SnRKs. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1677–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hu, X.; Huang, X.; Huo, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, P.; Ouyang, K.; Chen, X. Functional identification of an EXPA gene (NcEXPA8) isolated from the tree Neolamarckia cadamba. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Yan, X.; Bai, W.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, L.; Zhao, J.; Ding, X.; Liu, R.; et al. Carpel-specific down-regulation of GhCKXs in cotton significantly enhances seed and fiber yield. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 6758–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoud, C.; Ollio, I.; Solano, C.J.; Ochoa, J.; Suardiaz, J.; Fernández, J.A.; Martínez Ballesta, M.D.C. Red LED light improves pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seed radicle emergence and growth through the modulation of aquaporins, hormone homeostasis, and metabolite remobilization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, P.; Duan, J.; Huang, F.; Hou, J.; Zou, X.; Ou, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Key Genes Involved in Fruit Length Trait Formation in Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, Y. A gene module identification algorithm and its applications to identify gene modules and key genes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. Role of enzymes in seed germination. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2018, 6, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Raviv, B.; Aghajanyan, L.; Granot, G.; Makover, V.; Frenkel, O.; Gutterman, Y.; Grafi, G. The dead seed coat functions as a long-term storage for active hydrolytic enzymes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Lv, H.; Li, J.; Liang, B.; Zhou, W. Seed priming with protein hydrolysate promotes seed germination via reserve mobilization, osmolyte accumulation and antioxidant systems under PEG-induced drought stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 2173–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.; Srivastava, J.P.; Singhal, R.K.; Soufan, W.; Dadarwal, B.K.; Mishra, U.N.; Anuragi, H.; Rahman, M.A.; Sakran, M.I.; Brestic, M.; et al. Alterations of oxidative stress indicators, antioxidant enzymes, soluble sugars, and amino acids in mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern and Coss.] in response to varying sowing time, and field temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 875009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Fan, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Fan, S.; Huang, W. Green analytical assay for the viability assessment of single maize seeds using double-threshold strategy for catalase activity and malondialdehyde content. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Seng, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Yao, T.; Liang, J.; Yi, M.; Wu, J. Antagonism between abscisic acid and gibberellin regulates starch synthesis and corm development in Gladiolus hybridus. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemah, J.; Aluko, O.O.; Ninkuu, V.; Adetunde, L.A.; Anyetin-Nya, A.K.; Abugri, J.; Ullrich, M.S.; Dakora, F.D.; Chen, S.; Kuhnert, N. The Phytochemical Insights, Health Benefits, and Bioprocessing Innovations of Cassava-Derived Beverages. Beverages 2025, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.D.; Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H. Cysteine metabolism in neuronal redox homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahuja, A.; Kumar, R.R.; Sakhare, A.; Watts, A.; Singh, B.; Goswami, S.; Sachdev, A.; Praveen, S. Role of ATP--binding cassette transporters in maintaining plant homeostasis under abiotic and biotic stresses. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 171, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, J.; Udawat, P.; Dubey, A.K.; Haque, M.I.; Rathore, M.S.; Jha, B. Overexpression of SbSI-1, a nuclear protein from Salicornia brachiata confers drought and salt stress tolerance and maintains photosynthetic efficiency in transgenic tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamirisa, S.; Vudem, D.R.; Khareedu, V.R. Overexpression of pigeonpea stress-induced cold and drought regulatory gene (CcCDR) confers drought, salt, and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4769–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Lian, M.; Hou, Y.; Ge, T.; Yue, X.; Ye, Q.; Lv, H.; Dong, Q.; Yuan, F.; Jia, Z.; et al. From Seeds to Survival: The Role of polyamines for Improved Germination and Drought Resilience in Three Pepper Varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 344, 114114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Song, Z. Antioxidant activation, cell wall reinforcement, and reactive oxygen species regulation promote resistance to waterlogging stress in hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewsey, M.G.; Bassel, G.W.; Whelan, J. Dynamic and spatial control of cellular activity during seed germination. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 86, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassel, G.W.; Lan, H.; Glaab, E.; Gibbs, D.J.; Gerjets, T.; Krasnogor, N.; Bonner, A.J.; Holdsworth, M.J.; Provart, N.J. Genome-wide network model capturing seed germination reveals coordinated regulation of plant cellular phase transitions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9709–9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, F.; Damari, R.N.; Chen, X.; Lin, Z. Molecular mechanisms underlying the signal perception and transduction during seed germination. Mol. Breed. 2024, 44, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).