Abstract

The genus Trifolium comprises numerous species that serve as globally important forage and ornamental crops. However, phenotypic difference between species were difficult to define in many cases because of the wide range of diversity caused by primary polymorphism. To effectively identify and differentiate Trifolium species, a total of 5288 candidate EST-SSR molecular markers were developed based on Trifolium repens transcriptome sequencing results, and 132 EST-SSRs that produced clear, reproducible, and highly polymorphic bands were verified after random selection and initial screening. Finally, 202 different bands were amplified by the 28 pairs of SSR primers, and variety identification and DNA fingerprinting were constructed for 16 Trifolium varieties mainly cultivated in China. The polymorphism information index (PIC) ranged from 0.117 to 0.432, with an average of 0.311. Cluster analysis and principal component analysis demonstrated that white clover clustered into a separate group, suggesting a relatively distant genetic relationship with the other 12 Trifolium materials. The DNA fingerprint map of Trifolium species constructed using highly polymorphic markers can effectively distinguish 16 different Trifolium materials. Notably, these markers developed from T. repens show high interspecific transferability, providing a powerful tool for further dissecting genetic diversity within the Trifolium genus, accelerating marker-assisted breeding programs, and reconstructing species domestication trajectories.

1. Introduction

Clover (Trifolium L.) is a distinct group of forage legumes within the family Fabaceae, subfamily Faboideae []. The genus Trifolium is widely distributed, with about 290 species, mainly distributed in Eurasia (150–160 species), North America (60–65 species) and Africa (25–30 species). More than half of them originate from the Mediterranean basin []. Among these, twenty species (10%) are well known forage crops of several regions to feed animals [,]. In addition, it also serves as green-manure crops that enhances soil fertility and promotes sustainable grassland management. However, phenotypic difference between species were difficult to define in many cases because of the wide range of diversity caused by primary polymorphism. Consequently, a comprehensive genetic characterization and the development of molecular tools for diversity assessment, variety identification and marker-assisted breeding are essential prerequisites for crop improvement []. Hence, the study of inter- and intraspecific variation, species identification and DNA fingerprinting of Trifolium will be beneficial in gaining insight into the species relationships of clover.

Genomic SSR development is typically limited by high developmental costs, the occurrence of non-functional marker–trait associations, and instability in polymorphic expression. Furthermore, for the genus Trifolium, genomic information is only available for Trifolium repens, Trifolium pratense, and Trifolium subterraneum, while the remaining species lack sufficient genomic data [,]. EST-SSRs are derived from expressed sequence tags, which are part of the transcribed region of the genome and are directly associated with functional genes. The use of EST-SSRs as functional targets can help in identifying genes involved in specific biological processes. Overall, EST-SSR markers are more conserved among taxa, more transferable among related species, and significantly less expensive to develop than genomic SSRs [,]. Consequently, they provide an efficient tool for multi-species breeding programs, germplasm characterization and conservation, and DNA fingerprinting [,,]. Previous studies demonstrated that EST-SSRs reliably quantified genetic diversity and differentiate cultivars in Trifolium species such as white clover [,], red clover [,], and subterranean clover [], as well as in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) []. Furthermore, 90 stable EST-SSR markers were screened from 100 synthesized primer pairs, and 51 randomly selected markers revealed greater genetic diversity in Inner Mongolia accessions and landrace-wild groups of erect milkvetch (Astragalus adsurgens Pall.), providing a key resource for its germplasm improvement and genetic diversity analysis [].

Trifolium repens originated as an allotetraploid in the Mediterranean 15 to 28 kya resulting from the hybridization of its diploid progenitors, Trifolium occidentale and Trifolium pallescens [,]. It is widely distributed across temperate and subtropical high-altitude regions, and owing to its high nutritional value, palatability, and yield, serves as the primary leguminous forage in temperate mixed-grassland systems that support 80% of global milk and 70% of beef production []. As the most widely distributed species within the genus Trifolium, white clover exhibits high levels of heterozygosity and frequent genetic exchange [], with markers developed from it showing high transferability and broad applicability. Early foreign efforts concentrated on large-scale development of gSSRs using genomic library construction and enrichment technique []. These genomic SSRs (gSSRs) have subsequently been extensively utilized for genetic linkage map construction, population structure analysis, and cultivar fingerprinting [,], thereby becoming the principal molecular tools for white clover genetic research. In contrast, EST-SSRs—functional markers linked to expressed genes—have been largely overlooked in white clover research, despite their extensive development in related legumes such as Medicago sativa [] and Trifolium pratens []. For white clover, a species characterized by complex allopolyploid genetics and high heterozygosity, EST-SSRs could complement gSSRs by targeting genes related to adaptive and agronomic traits—thereby addressing a key limitation of gSSRs, which are often derived from non-coding regions and lack functional relevance. The current scarcity of EST-SSR resources has significantly impeded advancements in functional genetic diversity studies, trait-marker association analyses, and molecular breeding for key agronomic traits (e.g., forage quality, stress tolerance) in T. repens.

To address this critical gap, we conducted comprehensive mining of the T. repens transcriptome with three core objectives: (1) to characterize the frequency, genomic distribution, and putative functional associations of SSR motifs within unigenes; (2) to develop novel EST-SSR markers and rigorously examine their polymorphism; (3) to analyze the cross-species transferability of the polymorphic EST-SSRs. The EST-SSR marker resource will facilitate population-genetic analyses, accelerate trait-linked marker discovery, and enhance molecular-assisted breeding programs not only for T. repens but also for related Trifolium species, leveraging the high cross-transferability of EST-SSRs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of EST-SSR Markers Derived from Transcriptome of Trifolium repens

In our previous work, paired-end cDNA libraries of T. repens were constructed and sequenced based on SBS (Sequencing by Synthesis). Raw reads were deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession RJNA771135 [] and subsequently processed on the BMKCloud pipeline (www.biocloud.net). Transcripts ≥ 500 bp were screened with MISA (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/ (accessed on 14 September 2022)) using minimum repeat thresholds of 10, 6, 5, 5, 5, and 5 for mono- to hexa-nucleotide motifs, respectively. EST-SSR primer pairs were then batch-designed with Primer3.0 (https://primer3.org/ (accessed on 21 June 2023)) based on the MISA output.

2.2. Plant Materials and DNA Extraction

Nine Trifolium varieties (T. repens, T. pratense, T. incarnatum, T. vesiculosum, T. resupinatum, T. fragiferum, T. subterraneum, T. hybridum and T. alexandrinumI) mainly cultivated in China were analyzed (Table 1). Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh young leaves using a commercial kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to its accompanying instructions. After DNA concentration and quality were assessed, the DNA was diluted to 50 ng/µL, and stored at −20 °C until further use.

Table 1.

Materials of Trifolium used in this study.

2.3. PCR Amplification and Electrophoresis

From the 5288 candidate EST-SSR loci, 300 primer pairs were randomly chosen and synthesized. All primer pairs were used for amplification of 6 Trifolium materials (each clover materials include three biological replicates) with obvious morphological differences, of which 132 primer pairs produced clear, reproducible (with more than two replicates appeared), and highly polymorphic bands were retained for cross-species transferability tests across 9 Trifolium species. PCR amplification and electrophoresis were performed according to Ma et al. []. Gel-Pro Analyzer 4.0 software was used to estimate the band sizes.

2.4. Functional Annotations of EST-SSRs

To determine the predicted function, all unigene transcripts were annotated by searching against eight public databases: Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), Gene Ontology (GO) [], Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [], Clusters of eukaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG) [], Protein family (Pfam) (https://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 27 July 2023)), Swiss-Prot [], Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (egg-NOG) and Non-Redundant Protein Sequence Database (NR) [].

2.5. Data Analysis

All amplified bands using EST-SSR markers were scored as a binary matrix (1 = presence, 0 = absence). The total number of bands, the number of polymorphic bands, and the percentage of polymorphic bands (PPB) were recorded. Polymorphism information content (PIC) for each marker was calculated as PICi = 2 fi (1 − fi), where fi is the frequency of the amplified allele. Genetic similarity coefficients were obtained with NTSYSpc, and clustering was performed using the UPGMA algorithm (SAHN module) []. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was also executed in NTSYSpc (https://www.appliedbiostat.com/ntsyspc/update_NTSYSpc.html (accessed on 2 December 2023)). Allelic data were finally exported to Excel 2016 to visualize DNA fingerprints for the 16 clover materials.

3. Results

3.1. Frequency Distribution and Development of EST-SSR Markers

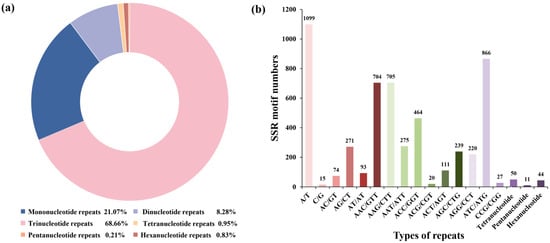

Mining 37,638 high-quality transcripts (69.68 Mb) with MISA revealed 5288 EST-SSRs (14.05%) encompassing mono- to hexa-nucleotide repeats in T. repens (Figure 1). Tri-nucleotide motifs dominated (3631; 68.66%), followed by mono-nucleotide (1114; 21.07%) and di-nucleotide (438; 8.28%) repeats; tetra-nucleotide (50, 0.95%), hexa-nucleotide (44, 0.83%), and penta-nucleotide (11, 0.21%) motifs were rare (Figure 1a). Notably, 821 unigenes (15.53%) harbored multiple SSRs, and 390 loci occurred in compound configurations. Among the motif types, A/T mononucleotide repeats dominate (1099; 20.78%) and are approximately 73-fold more frequent than C/G repeats (15). The most frequent trinucleotide motifs were ATC/ATG (16.38%), AAG/CTT (13.33%), and AAC/GTT (13.31%), collectively accounting for the majority of motif diversity in the T. repens transcriptome (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of identified in T. repens SSR loci. (a) Characteristics of identified SSR. (b) different types of tandem repeats considering sequence complementary.

3.2. SSR Annotation and Classification

To infer the putative functions of SSR-containing unigenes, we queried all 5288 sequences against eight reference databases (COG, GO, KEGG, KOG, Pfam, Swiss-Prot, eggNOG, and NR). Annotation rates ranged from 23.46% (COG, 1149 unigenes) to 89.10% (NR, 4362 unigenes) (Table 2). Overall, 4396 unigenes (89.75%) received at least one functional annotation, 658 (13.43%) were annotated in all eight databases, and 502 (10.25%) lacked any match. These non-annotated sequences may represent transcripts specific to T. repens growth and development.

Table 2.

Functional annotation landscape of SSR-containing unigenes in T. repens transcriptome.

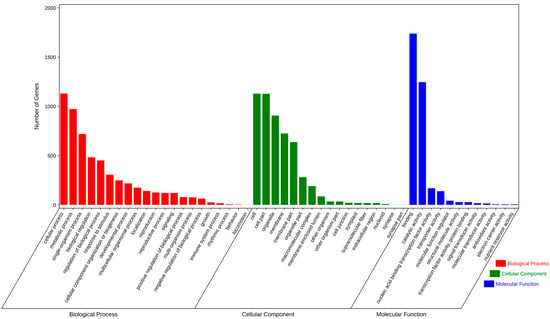

Following the Gene Ontology (GO) framework, the 5288 SSR-containing unigenes were assigned to three principal ontologies: cellular component (5199, 37.94%), biological process (5061, 36.93%), and molecular function (3445, 9.54%). These were further subdivided into 21, 17, and 12 sub-categories, respectively (Figure 2). Within biological process, “cellular process,” “metabolic process,” and “single-organism process” were the most prevalent. The cellular component ontology was dominated by “cell,” “cell part,” and “organelle,” while “binding” and “catalytic activity” were the predominant classes under molecular function.

Figure 2.

Gene ontology classifications of T. repens annotated unigenes. Numbers of genes indicate the sequences associated with the particular GO terms in different categories.

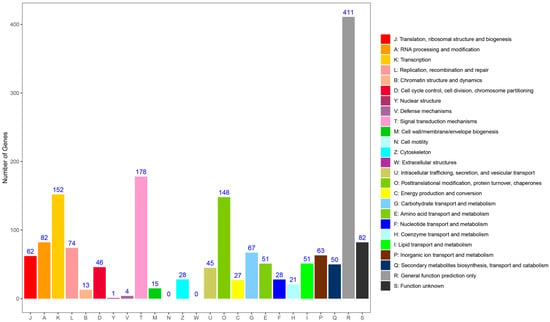

To predict gene function, the SSR-containing unigenes were queried against the KOG database and assigned to 23 functional categories (Figure 3). The largest group was “general function prediction only” (411, 24.19%), followed by “signal transduction mechanisms” (178, 10.48%), “transcription” (152, 8.95%), and “post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones” (148, 8.71%). Conversely, “nuclear structure” (1, 0.06%) and “defense mechanisms” (4, 0.24%) were the least represented.

Figure 3.

Clusters of orthologous groups for eukaryotic complete genomes (KOG) classification. The proportions were genes annotated in particular functional categories to all the annotated genes.

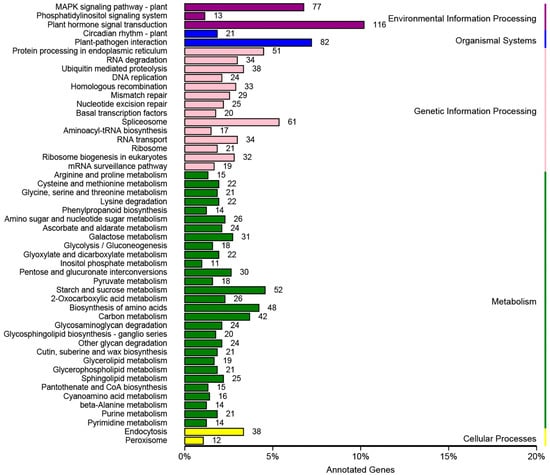

KEGG pathway annotation placed unigenes into 121 metabolic pathways, which were grouped into five primary categories: metabolism (673, 45.78%), genetic information processing (438, 29.80%), environmental information processing (206, 14.01%), organismal systems (103, 7.00%), and cellular processes (50, 3.40%) (Figure 4). The most represented pathways were plant hormone signal transduction (116 genes), plant–pathogen interaction (72), MAPK signaling in plants (66), spliceosome (61), and starch and sucrose metabolism (58). Metabolism comprising 29 subcategories was the largest functional class, whereas cellular processes and organismal systems contained only two subcategories each. The prevalence of genes in metabolism and genetic information processing provides a valuable resource for future investigations into the physiology, biochemistry, and functional genomics of white clover.

Figure 4.

KEGG Pathway Assignment of Genes Across Five Functional Categories: Environmental Information Processing, Organismal Systems, Genetic Information Processing, Metabolism, and Cellular Processes.

3.3. Development and Validation of Novel EST-SSRs Markers in Trifolium repens

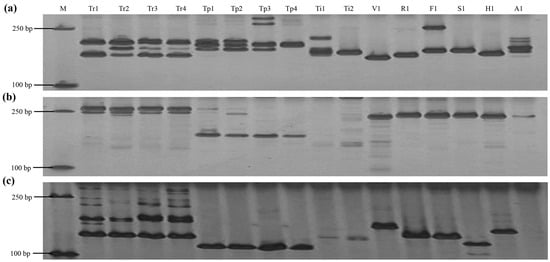

From the complete EST-SSR primer pairs, 300 primer pairs were randomly chosen for initial amplification in six Trifolium materials. A total of 132 EST-SSRs were retained; these were then evaluated across 16 Trifolium materials representing nine Trifolium species (Figure 5). Ultimately, 28 primer pairs (21.21%) generated reproducible, correctly sized amplicons in all materials, demonstrating robust cross-species transferability. Details of primer sequences, bands of expected sizes, and potential functions of EST-SSR markers are provided in Tables S1 and S2. These 28 markers collectively yielded 202 scorable fragments, of which 199 were polymorphic (97.20%). Per-marker polymorphism ranged from 66.67% to 100% (Table 3), with 25 primers (89.29%) exhibiting full polymorphism. Individual markers produced 3–15 bands (mean = 7.21), and polymorphism information content (PIC) varied from 0.117 to 0.432 (mean = 0.311). Thus, the newly developed EST-SSR set combines high discriminatory power with abundant allelic information, providing a valuable tool for genetic analyses within Trifolium.

Figure 5.

Amplification of 16 Trifolium materials by three primer pairs. (a): chr2.jg7616; (b): chr11.jg2002; (c): Tr.ng2288; M: marker; Tr1: T. repens; Tr2: T. repens; Tr3: T. repens; Tr4: T. repens; Tp1: T. pratense; Tp2: T. pratense; Tp3: T. pratense; Tp4: T. pratense; Ti1: T. incarnatum; Ti2: T. incarnatum; V1: T. vesiculosum; R1: T. resupinatum; F1: T. fragiferum; S1: T. subterraneum; H1: T. hybridum; A1: T. alexandrinum.

Table 3.

The amplification results of EST-SSR primers used in this study on clovers.

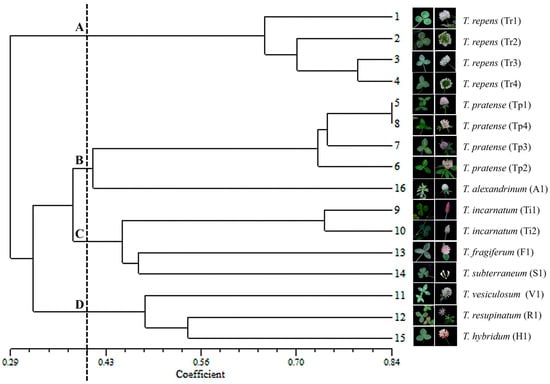

3.4. Evaluation of Genetic Relationships Among Different Trifolium Species

To clarify phylogenetic relationships among the 16 Trifolium materials, 202 EST-SSR alleles were analyzed with UPGMA and PCoA. A UPGMA dendrogram was constructed based on genetic similarities calculated with Dice’s coefficient (Figure 6). At a genetic similarity threshold of approximately 0.402, the 16 Trifolium materials formed four distinct genetic clusters. White clover comprised a separate group (Cluster A), indicating a relatively distant genetic relationship and high degree of differentiation from the other species. T. alexandrinum, a cool-season annual introduced from the eastern Mediterranean, clustered with red clover (Cluster B), corroborating previous findings of close affinity []. Notably, T. pratense cvs. “Tp1” and “Tp4” exhibited the highest genetic similarity (0.84), suggesting a very close genetic relationship. Cluster C included four materials: T. incarnatum cvs. “Ti1” and “Ti2”, T. fragiferum, and T. subterraneum. Apart from T. fragiferum, these are annual, hairy clovers. T. subterraneum has a unique morphology characterized by heart-shaped leaflets and small, axillary inflorescences of 4–6 flowers. The final cluster (D) consisted of three species: T. vesiculosum, T. resupinatum, and T. hybridum. Both T. vesiculosum and T. resupinatum are annuals originating from the Mediterranean region and Asia Minor, respectively. These results revealed a high amount of genetic diversity within the Trifolium species.

Figure 6.

UPGMA dendrogram of 16 Trifolium species based on similarity coefficient.

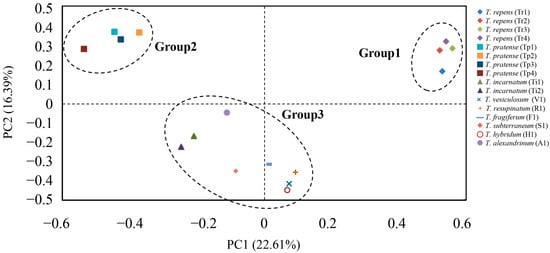

PCoA results were congruent with the UPGMA dendrogram (Figure 7). The first two axes explained 22.61% and 16.39% of the total variance, respectively. A clear genetic partition separated white clover (Group 1) from red clover (Group 2) materials, underscoring inter-specific divergence. While the remaining materials formed a distinct Group 3. These results affirm the utility of EST-SSR markers for accurate species and variety classification. Overall, the EST-SSR markers exhibit exceptional discriminatory capacity, enabling reliable differentiation of species and cultivars across the genus Trifolium.

Figure 7.

The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of 16 Trifolium materials.

3.5. DNA Fingerprint Construction for Clovers

Based on the electrophoretic profiles obtained with the 28 polymorphic EST-SSR markers, a binary (1/0) band matrix was compiled. From this matrix, the five most informative primer pairs were selected to establish an unambiguous DNA fingerprint (Figure 8). This combined set of markers provided unambiguous discrimination among all 16 tested clover materials; however, no single marker pair was sufficient on its own to achieve complete differentiation. Notably, the chr5.jg6570 primer, amplifying a 277 bp locus, failed to produce an amplification band exclusively in T. subterraneum, allowing its immediate identification from the other 15 materials. Thus, T. subterraneum is readily identified by both its unique phenotype and its distinct DNA profile. Congruent with PCoA and UPGMA results, cultivars “Tr2” and “Tr3” (both T. repens) could be merged into Group A; nevertheless, the 247 bp fragment produced by chr2.jg250 is unique to “Tr2”, distinguishing it from “Tr3”. Similarly, chr10.jg2633 (223 bp) distinguishes “Tr3” from “Tr4”, while “Tp1” and ‘Tp2” (T. pratense) differ via chr10.jg2633. The two T. incarnatum cultivars, “Ti1” and “Ti2”, differ not only in flower color but also in the 207 bp allele of chr2.jg7616. T. vesiculosum and T. resupinatum are separable by chr5.jg6570 (215 bp), whereas chr1.jg8919 (245 bp) distinguishes T. resupinatum from T. hybridum. Finally, T. resupinatum and T. fragiferum differ consistently in the 163 bp and 155 bp alleles of chr2.jg7616. Collectively, these results confirm that the 5 pairs of EST-SSR primers are sufficient to clearly identify all 16 Trifolium materials, highlighting the unique discriminatory ability of the developed markers.

Figure 8.

DNA fingerprint of 16 Trifolium materials based on 5 pairs of EST-SSR markers.

4. Discussion

Molecular markers are essential for both fundamental genetic research and applied breeding. However, marker-assisted selection (MAS) and molecular breeding in Trifolium repens have lagged behind those in other forage legumes due to the absence of genomic sequences. Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) offers a rapid, reliable, and cost-effective approach for identifying and developing large-scale EST-SSR markers []. These EST-SSRs are particularly valuable for detecting polymorphisms among closely related species and for advancing marker-assisted breeding programs. In this study, 37,638 transcript contigs generated 5288 putative EST-SSRs (14.05%), a frequency lower than reported for Melilotus albus (14.60%) and Medicago sativa (15.13%), but substantially higher than in Medicago truncatula (2.98%) [,,]. These discrepancies likely arose from species-specific transcript expression profiles. The observed density of one SSR per 13.18 kb is lower than the previously reported estimate of one per 4.7 kb in white clover coding regions []. Such variation can be attributed to differences in search algorithms, stringency parameters, and inherent genomic features []. In many organisms, tri-nucleotide repeats dominate in the EST-SSR landscape, a pattern consistent with selection against frameshift mutations in coding regions [,], which was also mirrored in findings from Trifolium pratense [], Medicago sativa [], Hibiscus Cannabinus [], with ATC/ATG being the most abundant motif, analogous to results in Erigeron breviscapus []. As depicted in Figure 1, mono-nucleotide A/T repeats were the most frequent, a feature indicative of poly(A) tails in retroposed sequences and processed pseudogenes []. Notably, GC dinucleotide repeats were absent, consistent with other studies [,], likely due to cytosine methylation in CpG contexts that suppresses transcription [,]. Within the genus Trifolium, interspecific differences in EST-SSR motifs are evident: T. pratense exhibits a higher proportion of tri-nucleotide repeats (62%) [], while T. repens shows a more balanced distribution of mono-, di-, and tri-nucleotide repeats []. These patterns reflect genus-specific adaptive evolution under distinct ecological pressures. The prevalence of low-order repeats in white clover’s EST-SSRs suggests an extended evolutionary history and heightened mutational dynamics [], aligning with observations of significant genetic variability in its adaptive and reproductive traits. This complements SSR-based phylogenetic studies that clarify relationships within the Trifolium genus [].

Genetically, the 5288 identified EST-SSRs significantly enrich the functional marker pool of white clover, akin to gSSRs that facilitated linkage map construction []. However, EST-SSRs confer unique advantages: their linkage to functional genes allows direct associations between genetic variation and phenotypic traits, whereas gSSRs, often derived from non-coding regions, are better suited for genome-wide mapping and population structure analysis. SSR dendrograms effectively reflect the geographical origins of white clover germplasm resources [], although the species samples selected in this study were insufficient to be geographically representative. Agronomically, such EST-SSRs are valuable for rapid hybrid identification and cultivar fingerprinting []. Moreover, the focus on metabolic pathways through KEGG annotations can guide targeted breeding for key agronomic traits, such as linking metabolic genes to high protein content or condensed tannin accumulation, which are crucial for developing high-quality forage cultivars []. Collectively, these EST-SSR resources and annotation results will expedite molecular-assisted breeding programs by enabling precise parent selection and trait screening [,].

Since ESTs originate from transcribed regions, they exhibit higher conservation across closely related taxa compared to non-coding DNA, thereby endowing EST-SSRs with superior transferability []. Species complexes and interspecific hybrids often evade precise identification through traditional morphological methods []. Intensive breeding has further narrowed genetic backgrounds, eroded diversity and produced morphologically convergent cultivars, rendering phenotype-based classification unreliable [,]. EST-SSR markers effectively bypass these limitations: their conserved flanking sequences offer exceptional cross-taxa transferability, thereby reducing primer-development costs and increasing marker density []. This advantage has been confirmed in legumes such as Pisum sativum [], Erect milkvetch (Astragalus adsurgens Pall.) [] and Vigna angularis []. Medicago eSSR markers showed high transferability in both legume (53–71%) and non-legume (33–44%) species, demonstrating utility in assessing genomic relationships between legume and non-legume species []. The genus Trifolium encompasses approximately 290 annual or perennial species native to the Middle East, Europe, the Americas, and Africa []. In this study, 28 white-clover EST-SSR primer pairs exhibited a 21.21% transferability across 9 Trifolium species, which is significantly higher than the 2–8% reported for genomic SSRs of Egyptian clover in related legumes []. Twenty-eight polymorphic markers generated 202 alleles across 16 materials, resulting in an average polymorphic-band percentage (PPB) of 97.20%, which is significantly higher than values reported for Medicago sativa (71.55%) [], Elymus breviaristatus (83.4%) [] and Lolium multiflorum (75.1%) []. Although the mean PIC (0.311) was moderate, discriminatory power is not solely determined by PIC []. The total and polymorphic band counts (TNB = 7.21; NPB = 7.11) exceeded those reported in comparable studies and were sufficient to unambiguously distinguish all 16 Trifolium materials []. In conclusion, these primers represent a valuable and robust resource for conducting genetic diversity assessments, cultivar identification, marker-assisted breeding, and comparative genomics within white clover and its closely related species.

Utilizing white clover EST-SSR markers, we analyzed 16 Trifolium materials representing 9 Trifolium species. The maximum genetic similarity coefficient among the 16 entries was 0.84, indicative of substantial genetic diversity. The red clover cultivars (Tp1 and Tp4) exhibited an 84% similarity, reflecting reduced heterogeneity likely due to domestication and directional selection. White clover, a highly heterogeneous, facultatively apomictic allotetraploid, has diploid progenitors (T. pallescens, T. occidentale) that occupy contrasting habitats (coastal and alpine) [], and have undergone multiple introductions []. The results of PCoA were consistent with the UPGMA dendrogram, clearly distinguishing white clover from the other eight Trifolium species and classifying it into a separate group. This confirms that the EST-SSR markers reliably resolve both intra- and inter-specific relationships. However, limited number of samples employed in this study restricted on marker utilization. Future research should focus on expanding germplasm sampling and leveraging high-resolution genomic technologies to refine evolutionary models, thereby enhancing germplasm conservation and marker-assisted breeding efforts across the Trifolium genus.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first systematic endeavor to develop novel EST-SSR polymorphic markers from the Trifolium repens transcriptome, with a total of 28 EST-SSR primer markers verified. The identified loci are abundant, highly polymorphic, and exhibit substantial allelic diversity. UPGMA clustering and PCoA analyses revealed that white and red clover are genetically distant from seven other Trifolium species, underscoring their significant sequence polymorphism and high heterogeneity. Additionally, five pairs of molecular markers were identified that can specifically distinguish 16 materials within the genus Trifolium. The findings of this study not only provide a valuable reference for analyzing genetic diversity within Trifolium species but also augment the arsenal of molecular markers for T. repens, serving as a resource for molecular-assisted breeding.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122764/s1, Table S1: Information list of 28 pairs of EST-SSR primers; Table S2: Functional annotation of genes containing EST-SSR markers.

Author Contributions

Data curation, J.H. and L.Y.; funding acquisition, G.N. and X.Z.; investigation, J.H., R.H. and J.M.; methodology, L.Y. and R.H.; project administration, G.N. and X.Z.; resources, J.H.; software, L.Y.; validation, R.H.; writing—original draft, J.H., R.H. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.H., L.Y., J.M. and G.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the CARS earmarked fund (CARS-34), Sichuan Forestry and Grassland Technology Innovation Team (CXTD2025005) and Key project of Sichuan Science and Education Joint Fund (2025NSFSC2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ijaz, S.; Haq, I.; Nasir, B. In silico identification of expressed sequence tags based simple sequence repeats (EST-SSRs) markers in Trifolium species. ScienceAsia 2020, 46, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smykal, P.; Coyne, C.J.; Ambrose, M.J.; Maxted, N.; Schaefer, H.; Blair, M.W.; Berger, J.; Greene, S.L.; Nelson, M.N.; Besharat, N. Legume Crops Phylogeny and Genetic Diversity for Science and Breeding. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2014, 33, 43–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Chandra, A.; Roy, A.K.; Malaviya, D.R.; Kaushal, P.; Pandey, D.; Bhatia, S. Development, characterization and cross-species transferability of genomic SSR markers in berseem (Trifolium alexandrinum L.), an important multi-cut annual forage legume. Mol. Breed. 2015, 35, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrad, M.M.; Zayed, E.M. Morphological, biochemical and molecular characterization of Egyptian clover (Trifolium alexandrinum L.) varieties. Mol. Breed. 2009, 30, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Malaviya, D.R.; Roy, A.K.; Kaushal, P.; Kumar, B.; Tiwari, A. Genetic similarity among Trifolium species based on isozyme banding pattern. Plant Syst. Evol. 2008, 276, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Sang, L.; Ma, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, J.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Miao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; et al. A de novo assembled high-quality chromosome-scale Trifolium pratense genome and fine-scale phylogenetic analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, K.; Moraga, R.; Ghelfi, A.; Hirakawa, H.; Nagasaki, H.; Ghamkhar, K.; Barrett, B.A.; Griffiths, A.G.; Isobe, S.N. An improved reference genome for Trifolium subterraneum L. provides insight into molecular diversity and intra-specific phylogeny. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, T. Development and Application of EST-SSR Markers in Cephalotaxus oliveri From Transcriptome Sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 759557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Bai, Z.; Wang, F.; Zou, M.; Wang, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, F. Analysis of the genetic diversity and population structure of Monochasma savatieri Franch. ex Maxim Using Nov. EST-SSR markers. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, K. De novo transcriptomic analysis and identification of EST-SSR markers in Stephanandra incisa. Sicentific Rep. 2021, 11, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshad, U.H.; Prerna, D.N.; Meenakshi, S.N.; Kothari, S.L.; Sumita, K. Plasticity of tandem repeats in expressed sequence tags of angiospermic and non-angiospermic species: Insight into cladistic, phenetic, and elementary explorations. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 36–59. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:233628994 (accessed on 2 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Sun, H.J.; Eun, C.H.; Lee, H.Y. Morphological classification and molecular marker development of white clover (Trifolium repens L.) parents and hybrids. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 16, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ma, S.; Zhou, J.; Han, C.; Hu, R.; Yang, X.; Nie, G.; Zhang, X. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis in a large collection of white clover (Trifolium repens L.) germplasm worldwide. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerinasab, M.; Rahiminejad, M.R.; Ellison, N.W. Transferability of Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) Markers Developed in Red Clover (Trifolium pratense L.) to Some Trifolium Species. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2016, 40, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamkhar, K.; Isobe, S.; Nichols, P.G.H.; Faithfull, T.; Ryan, M.H.; Snowball, R.; Sato, S.; Appels, R. The first genetic maps for subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum L.) and comparative genomics with T. pratense L. and Medicago truncatula Gaertn. to identify new molecular markers for breeding. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoudi, L.; Hdira, S.; Cheikh, N.B.; Mahjoub, A.; Badri, M. Assessment of genetic diversity in Tunisian populations of Medicago polymorpha based on SSR markers. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 53–61. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:233825861 (accessed on 2 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Ma, L.; Gong, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G. Development and application of EST-SSRs markers for analysis of genetic diversity in erect milkvetch (Astragalus adsurgens Pall.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.G.; Moraga, R.; Tausen, M.; Gupta, V.; Bilton, T.P.; Campbell, M.A.; Ashby, R.; Nagy, I.; Khan, A.; Larking, A.; et al. Breaking Free: The Genomics of Allopolyploidy-Facilitated Niche Expansion in White Clover. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1466–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Xiong, Y.; He, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Lei, X.; Dong, Z.; Yang, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Two Important Annual Clover Species, Trifolium alexandrinum and T. resupinatum: Genome Structure, Comparative Analyses and Phylogenetic Relationships with Relatives in Leguminosae. Plants 2020, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, J.S.; Battlay, P.; Hendrickson, B.T.; Kuo, W.-H.; Olsen, K.M.; Kooyers, N.J.; Johnson, M.T.J.; Hodgins, K.A.; Ness, R.W. Haplotype-Resolved, Chromosome-Level Assembly of White Clover (Trifolium repens L., Fabaceae). Genome Biol. Evol. 2023, 15, evad146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.G.; Barrett, B.A.; Simon, D.; Khan, A.K.; Bickerstaff, P.; Anderson, C.B.; Franzmayr, B.K.; Hancock, K.R.; Jones, C.S. An integrated genetic linkage map for white clover (Trifolium repens L.) with alignment to Medicago. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Han, C.; Zhou, J.; Hu, R.; Jiang, X.; Wu, F.; Tian, K.; Nie, G.; Zhang, X. Fingerprint identification of white clover cultivars based on SSR molecular markers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 8513–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Dong, Y.; Chen, L.; Basigalup, D.; Wang, G.; Du, X. Development of SSR markers related to salinity resistance based on transcriptomic sequences in Medicago sativa. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0336528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ištvánek, J.; Dluhošová, J.; Dluhoš, P.; Pátková, L.; Nedělník, J.; Řepková, J. Gene Classification and Mining of Molecular Markers Useful in Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Fan, J.; Ye, X.; Yang, L.; Hu, R.; Ma, J.; Ma, S.; Li, D.; Zhou, J.; Nie, G.; et al. Unraveling Cadmium Toxicity in Trifolium repens L. Seedling: Insight into Regulatory Mechanisms Using Comparative Transcriptomics Combined with Physiological Analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinderer, E.W., III; Moseley, H.N.B. GOcats: A tool for categorizing Gene Ontology into subgraphs of user-defined concepts. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.M.; Oshlack, A. Corset: Enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novoassembled transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Fedorova, N.D.; Jackson, J.D.; Jacobs, A.R.; Krylov, D.M.; Makarova, K.S.; Mazumder, R.; Mekhedov, S.L.; Nikolskaya, A.N.; Rao, B.S.; et al. A comprehensive evolutionary classification of proteins encoded in complete eukaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussi, Y.C.; Magrane, M.; Martin, M.J.; Orchard, S. Searching and Navigating UniProt Databases. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, H.-Y.; Li, X.-J.; Dong, J.-G. Genetic diversity and population structure of Commelina communis in China based on simple sequence repeat markers. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 2292–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cai, C.; Cheng, F.; Cui, H.; Zhou, H. Characterisation and development of EST-SSR markers in tree peony using transcriptome sequences. Mol. Breed. 2014, 34, 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wu, F.; Luo, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Cross-species transferability of EST-SSR markers developed from the transcriptome of Melilotus and their application to population genetics research. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, T.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, P.X.; Nan, Z.; Wang, Y. Global transcriptome sequencing using the Illumina platform and the development of EST-SSR markers in autotetraploid alfalfa. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eujayl, I.; Sledge, M.K.; Wang, L.; May, G.D.; Chekhovskiy, K.; Zwonitzer, J.C.; Mian, M.A. Medicago truncatula EST-SSRs reveal cross-species genetic markers for Medicago spp. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, S.N.; Hisano, H.; Sato, S.; Hirakawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Shirasawa, K.; Sasamoto, S.; Watanabe, A.; Wada, T.; Kishida, Y.; et al. Comparative Genetic Mapping and Discovery of Linkage Disequilibrium Across Linkage Groups in White Clover (Trifolium repens L.). G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2012, 2, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, W.; Lin, X. Development and Characterization of EST-SSR Markers From RNA-Seq Data in Phyllostachys violascens. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Huang, X.; Yan, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Peng, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; et al. Transcriptome analysis in sheepgrass (Leymus chinensis): A dominant perennial grass of the Eurasian Steppe. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xie, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N.; Ntakirutimana, F.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y. EST-SSR marker development based on RNA-sequencing of E. sibiricus and its application for phylogenetic relationships analysis of seventeen Elymus species. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, S.A.; Swain, M.T.; Hegarty, M.J.; Chernukin, I.; Lowe, M.; Allison, G.G.; Ruttink, T.; Abberton, M.T.; Jenkins, G.; Skøt, L. De novo assembly of red clover transcriptome based on RNA-Seq data provides insight into drought response, gene discovery and marker identification. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Afzal, M.Z.; Yao, J.; Xu, J.; Lin, L.; Qi, J.; Zhang, L. Genome-Wide Analysis and Polymorphism Evaluation of Microsatellites Involved in Photoperiodic Flowering-time Genes in Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 8332–8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.H.; Zhang, G.H.; Zhang, J.J.; Shu, L.P.; Zhang, W.; Long, G.Q.; Liu, T.; Meng, Z.G.; Chen, J.W.; Yang, S.C. Analysis of the transcriptome of Erigeron breviscapus uncovers putative scutellarin and chlorogenic acids biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Shu, G.; Hu, Y.; Cao, G.; Wang, Y. Pattern and variation in simple sequence repeat (SSR) at different genomic regions and its implications to maize evolution and breeding. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Prasad, M. Development and characterization of genic SSR markers in Medicago truncatula and their transferability in leguminous and non-leguminous species. Genome 2009, 52, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, H.; Fu, X.; Li, X.; Gao, H. Development of simple sequence repeat markers and diversity analysis in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Liao, J.; Cai, M.; Xia, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Jin, X. De novo assembly of transcriptome from Rhododendron latoucheae Franch. using Illumina sequencing and development of new EST-SSR markers for genetic diversity analysis in Rhododendron. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Zhao, P.X.; Bouton, J.H.; Monteros, M.J. Genome-wide identification of microsatellites in white clover (Trifolium repens L.) using FIASCO and phpSSRMiner. Plant Methods 2008, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.; Griffiths, A.; Schreiber, M.; Ellison, N.; Mercer, C.; Bouton, J.; Ong, B.; Forster, J.; Sawbridge, T.; Spangenberg, G.; et al. A microsatellite map of white clover. heoretical and Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeynayake, S.W.; Panter, S.; Chapman, R.; Webster, T.; Rochfort, S.; Mouradov, A.; Spangenberg, G. Biosynthesis of proanthocyanidins in white clover flowers: Cross talk within the flavonoid pathway. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Jiang, X.B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.L.; Bo, W.H.; An, X.M.; Zhang, Z.Z.Y. Differences of EST-SSR and genomic-SSR markers in assessing genetic diversity in poplar. For. Stud. China 2012, 21, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, G.; Huang, T.; Ma, X.; Huang, L.; Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Genetic variability evaluation and cultivar identification of tetraploid annual ryegrass using SSR markers. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, J.A.; Forster, J.W.; Smith, K.F.; Spangenberg, G.C. Assessment of gene flow in white clover (Trifolium repens L.) under field conditions in Australia using phenotypic and genetic markers. Crop Pasture Sci 2012, 63, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; McPhee, K.E.; Coram, T.E.; Peever, T.L.; Chilvers, M.I. Development and characterization of 37 novel EST-SSR markers in Pisum sativum (Fabaceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 2013, 1, apps.1200249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Somta, P.; Cheng, X. Development and Validation of EST-SSR Markers from the Transcriptome of Adzuki Bean (Vigna angularis). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaviya, D.R.; Kumar, B.; Roy, A.K.; Kaushal, P.; Tiwari, A. Estimation of Variability of Five Enzyme Systems Among Wild and Cultivated Species of Trifolium. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Q.; Shi, S.-L. Genetic diversity of 42 alfalfa accessions revealed by SSR markers. Pratacultural Sci. 2015, 32, 372G381. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.Y.; Guo, Z.H.; Ma, X.; Bai, S.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, C.B.; Chen, S.Y.; Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.H.; Huang, L.K. Population genetic variability and structure of Elymus breviaristatus (Poaceae: Triticeae) endemic to Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau inferred from SSR markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2015, 58, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, U.; Pan, Y.B.; Muhammad, K.; Afghan, S.; Iqbal, J. Use of simple sequence repeat markers for DNA fingerprinting and diversity analysis of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) cultivars resistant and susceptible to red rot. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.F.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ma, X.; Huang, L.K.; Xie, W.G.; Ma, Y.M.; Zhao, Y.F. Identification of orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) cultivars by using simple sequence repeat markers. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 5111–5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).