From Microbial Functions to Measurable Indicators: A Framework for Predicting Grassland Productivity and Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

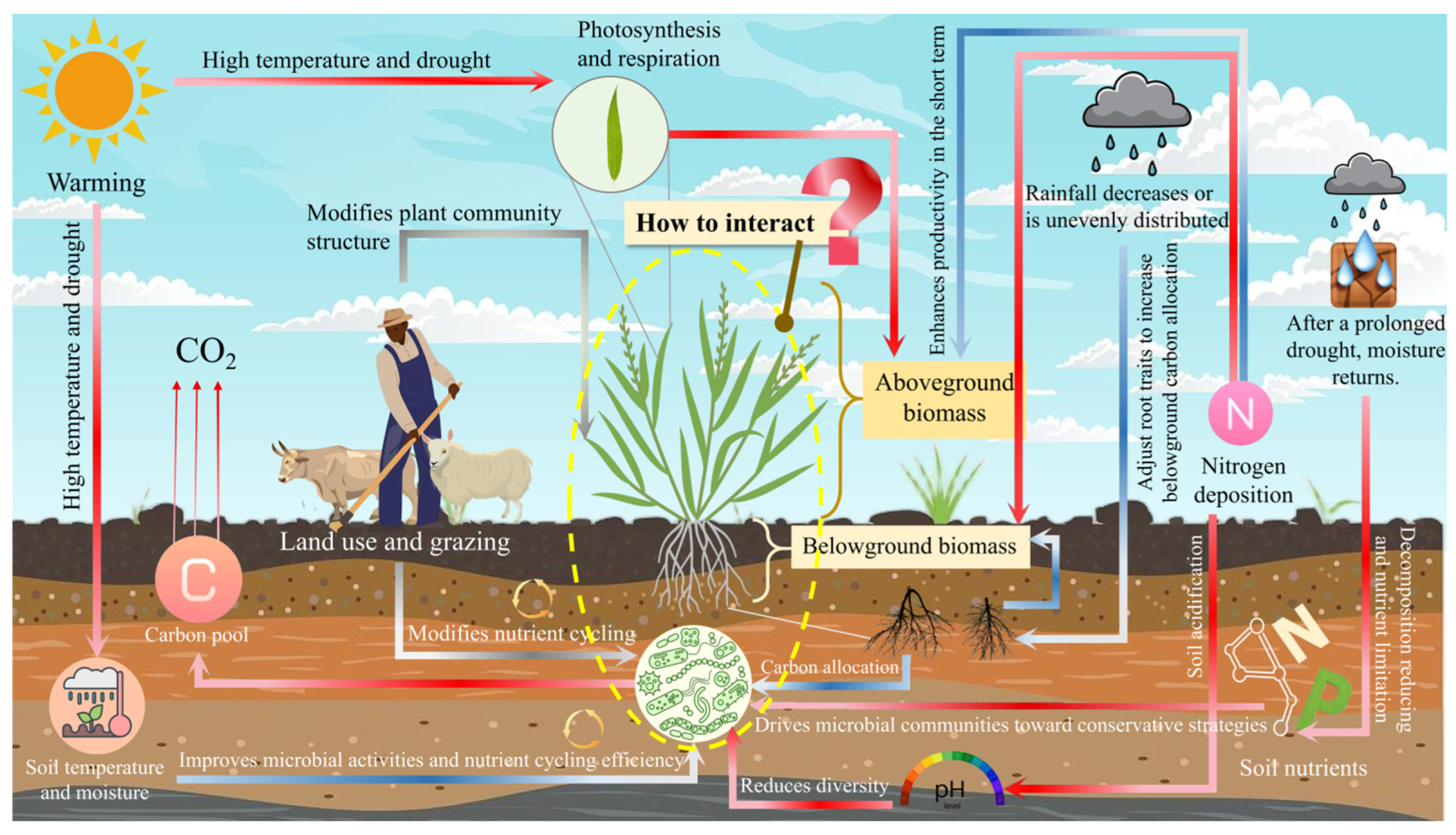

2. Regulatory Factors of Grassland Productivity

2.1. Climatic Factors: The Ultimate Environmental Filters

2.2. Soil Nutrient Availability: The Elemental Building Blocks

2.3. Anthropogenic Disturbances: The Overlying Human Imprint

2.4. The Unexplained Variance and the Path Forward

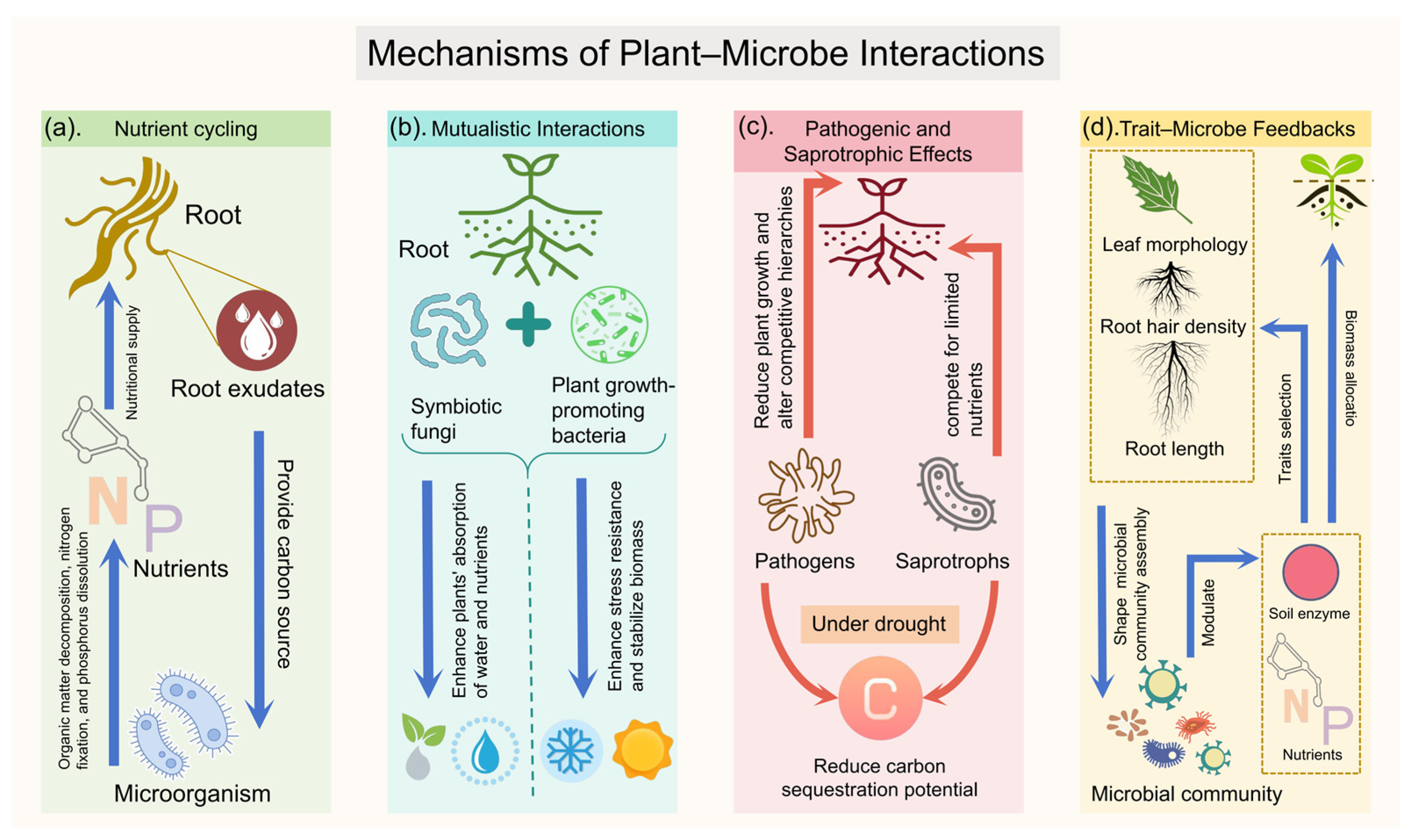

3. Core Mechanisms of Plant–Microbe Interactions in Regulating Grassland Productivity

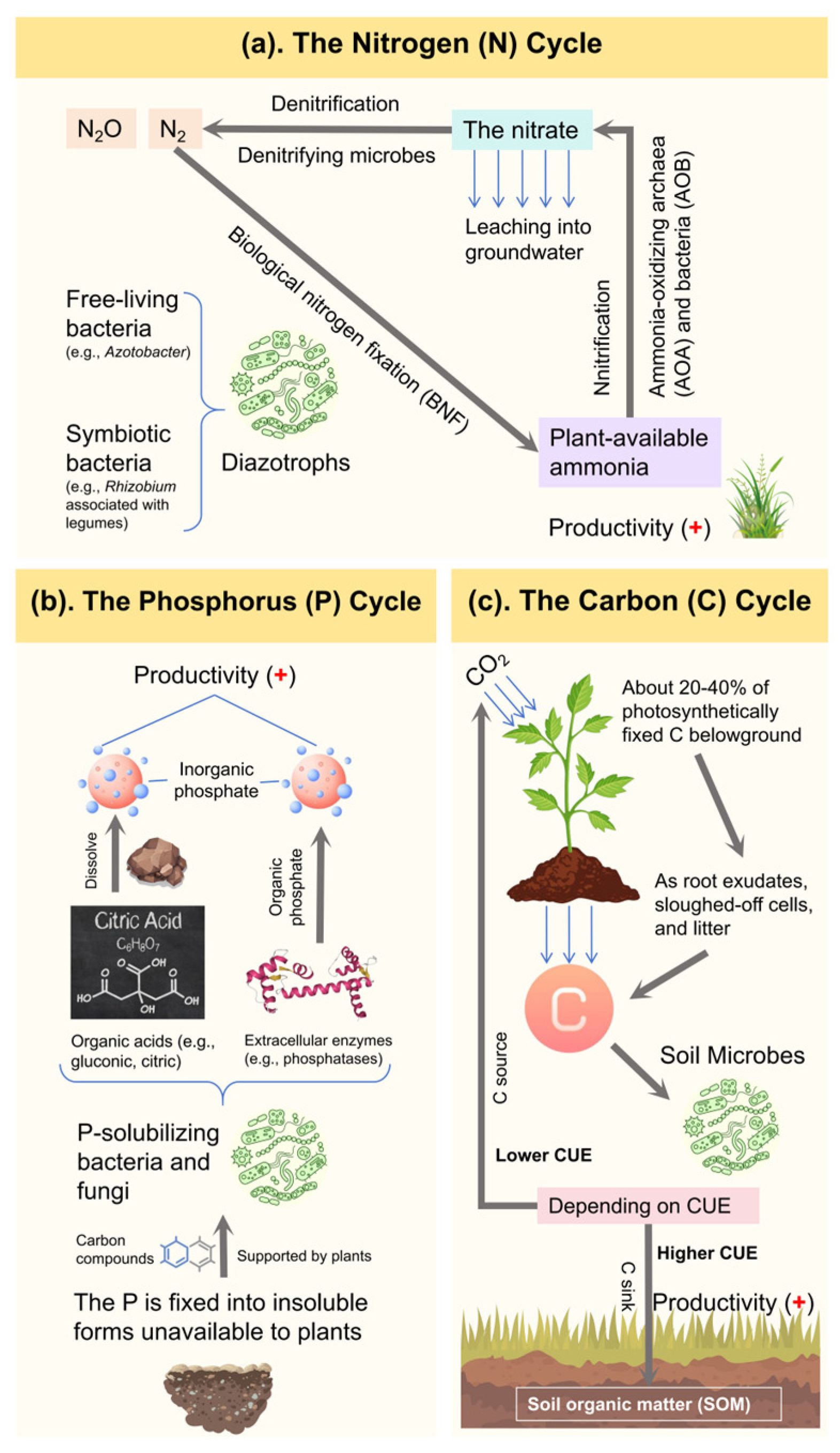

3.1. Nutrient Cycling and Resource-Use Efficiency: The Microbial Metabolic Engine

3.1.1. Nitrogen (N) Cycle

3.1.2. Phosphorus (P) Cycle

3.1.3. Carbon (C) Cycle

3.2. Mutualism and Symbiosis: Forging Strategic Alliances

3.2.1. Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Extended Root System

3.2.2. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and Endophytes: The Bio-Stimulants and Bodyguards

- (i)

- (ii)

- Phytohormone modulation: PGPR that produce auxins (IAA), cytokinins, and gibberellins can enhance root length and branching by about 20–40%, thereby improving water and nutrient uptake [113].

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Stress tolerance amelioration: By synthesizing osmoprotectants (proline, glycine betaine) and antioxidants, PGPR and endophytes enhance drought and heat tolerance. Epichloë in cool-season grasses produces alkaloids that deter herbivores and reduce evapotranspiration losses [116].

3.2.3. The Carbon Cost of Mutualism: A Dynamic Trade-Off

3.3. Pathogenic and Saprotrophic Effects: The Antagonistic and Competitive Forces

3.3.1. Pathogenic Effects: The Regulators of Plant Fitness and Diversity

3.3.2. Saprotrophic Effects: The Decomposers and Competitors

3.4. Plant Functional Trait–Microbe Feedbacks: Shaping the Ecosystem from the Bottom Up

3.4.1. Root Traits as the Primary Filter for the Rhizosphere Microbiome

3.4.2. Leaf Traits and the Afterlife Effects on Decomposition

3.4.3. Biodiversity-Stability Feedback Loops

3.5. Interactions at the Community and Network Level: The Emergence of System-Level Properties

3.5.1. Network Complexity as a Predictor of Ecosystem Stability

3.5.2. Microbial Indicators as Proxies for Network Function and Productivity Trends

4. Regional and Global Case Studies: Context-Dependent Manifestations of Plant-Microbe Interactions

4.1. Chinese Grasslands: A Natural Laboratory Along Environmental Gradients

4.1.1. Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (Alpine Meadow): Cold and Nitrogen-Limited Dynamics

4.1.2. Inner Mongolia Steppe (Temperate Arid and Semi-Arid): Water-Limited Resilience

4.1.3. Xinjiang Desert Grassland (Hyper-Arid): Survival Under Multiple Stresses

4.2. Global Comparative Analysis: Contrasting Responses to Global Change Drivers

4.2.1. North American Great Plains (Temperate Prairie): CUE and Management Interactions

4.2.2. Pampas of Argentina (Subtropical Grassland): Functional Simplification Under Intensive Conversion

4.2.3. African Sahel (Tropical Dry Savanna): Degradation Feedback Loops and Fire Interactions

4.2.4. Australian Drylands (Arid and Semi-Arid): Phosphorus Constraints and Partner Specificity

4.3. Synthesis: Universal Principles and Contextual Divergences

5. Methodology and Research Approaches

5.1. Multi-Omics and Isotopic Tracing

5.2. Experimental and Observational Frameworks

5.3. Data Integration, Modeling, and Scaling

5.4. Methodological Integration Framework

6. Implications for Application and Management

6.1. Microbial-Driven Grassland Restoration and Rehabilitation

6.2. Carbon Sequestration and the “Dual Carbon” Strategy

6.3. Enhancing Productivity for Livestock and Food Security

6.4. Grassland Health and Socioeconomic Benefits

7. Frontiers and Challenges

7.1. From Correlation to Causal Mechanisms

7.2. Multi-Factor Interactions Under Global Change

7.3. Microbial Tipping Points and Grassland Resilience

7.4. Cross-Scale and Cross-System Integration

7.5. Towards a Microbially Explicit Productivity Framework

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; UNFCCC. Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture: Outcomes and Recommendations; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/koronivia (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Assessing the Effects of Human Activities on Terrestrial Net Primary Productivity of Grasslands in Typical Ecologically Fragile Areas. Biology 2023, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Cotrufo, M.F. Grassland Soil Carbon Sequestration: Current Understanding, Challenges, and Solutions. Science 2022, 377, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, R.; Parmar, V.; Sankhyan, N.K.; Rana, R.S.; Mahajan, R.; Sharma, T. Grasslands in Focus: Evaluating and Monitoring Ecosystem Services. In Revealing Ecosystem Services Through Geospatial Technologies: Beyond the Surface; Mutanga, O., Pandey, P.C., Das, S., Chatterjee, U., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 59–80. ISBN 978-3-031-98048-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Ciais, P.; Gasser, T.; Smith, P.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Guenet, B.; Goll, D.S.; Li, W.; et al. Climate Warming from Managed Grasslands Cancels the Cooling Effect of Carbon Sinks in Sparsely Grazed and Natural Grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Shangguan, Z.; Bell, S.M.; Soromotin, A.V.; Peng, C.; An, S.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; et al. Carbon in Chinese Grasslands: Meta-Analysis and Theory of Grazing Effects. Carbon Res. 2023, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment. Emissions Gap Report 2024. UNEP-UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Emmett, B.; Büchi, L.; Smith, B.; Soleiman, J.; Thompson, W.; Dodsworth, J. Regenerative Agriculture in the UK: An Ecological Perspective; British Ecological Society: London, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-0369-1546-9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Yu, Y.; Malik, I.; Wistuba, M.; Guo, Z.; Lu, Y.; Ding, X.; He, J.; Sun, L.; Li, C.; et al. Time-Series MODIS-Based Remote Sensing and Explainable Machine Learning for Assessing Grassland Resilience in Arid Regions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, E.; Archibald, S.; Fidelis, A.; Suding, K.N. Ancient Grasslands Guide Ambitious Goals in Grassland Restoration. Science 2022, 377, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.T.; Malhi, Y. Carbon in the Atmosphere and Terrestrial Biosphere in the 21st Century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2002, 360, 2925–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, N.; Bond, W.; Feurdean, A.; Lehmann, C.E.R. Grassy Ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milazzo, F.; Francksen, R.M.; Abdalla, M.; Ravetto Enri, S.; Zavattaro, L.; Pittarello, M.; Hejduk, S.; Newell-Price, P.; Schils, R.L.M.; Smith, P.; et al. An Overview of Permanent Grassland Grazing Management Practices and the Impacts on Principal Soil Quality Indicators. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiao, W.; MacBean, N.; Rulli, M.C.; Manzoni, S.; Vico, G.; D’Odorico, P. Dryland Productivity under a Changing Climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwate, O.; Shekede, M.D. Chapter 6—Climate Variability and Natural Ecosystems Productivity. In Remote Sensing of Climate; Dube, T., Shekede, M.D., Shoko, C., Mushore, T.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 107–132. ISBN 978-0-443-21731-9. [Google Scholar]

- Huning, L.S.; Love, C.A.; Anjileli, H.; Vahedifard, F.; Zhao, Y.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Cooper, K.; Alborzi, A.; Pleitez, E.; Martinez, A.; et al. Global Land Subsidence: Impact of Climate Extremes and Human Activities. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62, e2023RG000817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Graciano, C.; Sardans, J.; Zeng, F.; Hughes, A.C.; Ahmed, Z.; Ullah, A.; Ali, S.; Gao, Y.; Peñuelas, J. Plant Root Mechanisms and Their Effects on Carbon and Nutrient Accumulation in Desert Ecosystems under Changes in Land Use and Climate. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 916–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Qiao, X.; Muhammad, M.; Yiremaikebayi, Y.; Yingying, X.; Xu, H.; Aili, A.; Wahab, A. Plant Root-Mediated Carbon Sequestration and Nutrient Cycling in Grassland Ecosystems under Land Use and Climate Change. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 393, 109865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C. Microbial Decomposition and Soil Health: Mechanisms and Ecological Implications. Mol. Soil Biol. 2024, 15, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Astapati, A.D.; Dey, S.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Singha, D.M.; Nath, S. Microbial Interactions in Soil Ecosystems: Facilitating Plant Growth, Nutrient Cycling, and Environmental Dynamics. In Microbial Allies: Understanding Plant-Microbe Interactions in Sustainable Agriculture; Babalola, O.O., Ayangbenro, A.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 21–48. ISBN 978-3-031-90530-8. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter, L.; van der Sande, M.T.; Amissah, L.; Bongers, F.; Hordijk, I.; Kok, J.; Laurance, S.G.W.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Matsuo, T.; Meave, J.A.; et al. A Comprehensive Framework for Vegetation Succession. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2024, 15, e4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Hassan, M.U.; Feng, L.; Nawaz, M.; Shah, A.N.; Qari, S.H.; Liu, Y.; Miao, J. The Critical Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Improve Drought Tolerance and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 919166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, R.B.; Dangi, S.R. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Rhizobium Improve Nutrient Uptake and Microbial Diversity Relative to Dryland Site-Specific Soil Conditions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate Change Impacts on Plant Pathogens, Food Security and Paths Forward. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.; Vernay, A.; Henneron, L.; Adamik, L.; Malagoli, P.; Balandier, P. Plant N Economics and the Extended Phenotype: Integrating the Functional Traits of Plants and Associated Soil Biota into Plant–Plant Interactions. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2015–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, R.; Cáliz, J.; Mattana, S.; Barceló, A.; Candela, M.; Elustondo, D.; Fortmann, H.; Hellsten, S.; Koenig, N.; Lindroos, A.-J.; et al. Substantial Contribution of Tree Canopy Nitrifiers to Nitrogen Fluxes in European Forests. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, N.M.; Alexander, H.; Bertrand, E.M.; Coles, V.J.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Leles, S.G.; Zakem, E.J. Microbial Ecology to Ocean Carbon Cycling: From Genomes to Numerical Models. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2025, 53, 595–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xiong, K.; Song, S.; Chi, Y.; Fang, J.; He, C. Research Progress of Grassland Ecosystem Structure and Stability and Inspiration for Improving Its Service Capacity in the Karst Desertification Control. Plants 2023, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scurlock, J.M.O.; Johnson, K.; Olson, R.J. Estimating Net Primary Productivity from Grassland Biomass Dynamics Measurements. Glob. Change Biol. 2002, 8, 736–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsamo, A.; Chen, J.M. 3.11—Vegetation Primary Productivity. In Comprehensive Remote Sensing; Liang, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 163–189. ISBN 978-0-12-803221-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tanentzap, A.J.; Coomes, D.A. Carbon Storage in Terrestrial Ecosystems: Do Browsing and Grazing Herbivores Matter? Biol. Rev. 2011, 87, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Felzer, B.S.; Nielsen, U.N.; Medlyn, B.E. Biome-specific Climatic Space Defined by Temperature and Precipitation Predictability. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnaire, F.I.; Morillo, J.A.; Peñuelas, J.; Reich, P.B.; Bardgett, R.D.; Gaxiola, A.; Wardle, D.A.; van der Putten, W.H. Climate Change Effects on Plant-Soil Feedbacks and Consequences for Biodiversity and Functioning of Terrestrial Ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaz1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Gao, J. Climate Factors Dominate the Elevational Variation in Grassland Plant Resource Utilization Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1430027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Quesada, B.; Xia, L.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Goodale, C.L.; Kiese, R. Effects of Climate Warming on Carbon Fluxes in Grasslands—A Global Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lin, Z.; Tang, S.; Peng, C.; Yao, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, H.; Liu, K.; Shao, X. Interactive Effects of Warming and Managements on Carbon Fluxes in Grasslands: A Global Meta-Analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Sheffield, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Talib, J.; Beck, H.E.; Singer, M.B.; et al. Warming Accelerates Global Drought Severity. Nature 2025, 642, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Peñuelas, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gentine, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Increasing Meteorological Drought under Climate Change Reduces Terrestrial Ecosystem Productivity and Carbon Storage. One Earth 2023, 6, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Su, Y.; Jian, S.; Guo, X.; Yuan, M.; Bates, C.T.; Shi, Z.J.; Li, J.; Su, Y.; Ning, D.; et al. Warming Effects on Grassland Soil Microbial Communities Are Amplified in Cool Months. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Heinzle, J.; Salas, E.; Kwatcho-Kengdo, S.; Borken, W.; Schindlbacher, A.; Wanek, W. Long-Term Soil Warming Decreases Soil Microbial Necromass Carbon by Adversely Affecting Its Production and Decomposition. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tan, H.; Tian, X. Soil Moisture Determines the Consistency of Organic Matter Decomposition in Field and Lab Test Patterns. CATENA 2024, 246, 108485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.; Ciais, P.; Gao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xue, J.; Qin, X.; Ros, G.H. Long-Term Climate Warming Weakens Positive Plant Biomass Responses Globally. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2420379122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Fu, Y.H.; Shi, X.; Lock, T.R.; Kallenbach, R.L.; Yuan, Z. Soil Moisture Determines the Effects of Climate Warming on Spring Phenology in Grasslands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 323, 109039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J. Climate Factors Affect Forest Biomass Allocation by Altering Soil Nutrient Availability and Leaf Traits. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Ji, Y.; Du, X.; Gao, J. Precipitation Dominates the Allocation Strategy of Above- and Belowground Biomass in Plants on Macro Scales. Plants 2023, 12, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Duan, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Guo, X. Climate Factors Affect above–Belowground Biomass Allocation in Broad-Leaved and Coniferous Forests by Regulating Soil Nutrients. Plants 2023, 12, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Cordones, M.; García-Sánchez, F.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Rubio, F.; Rosales, M.A. Coping With Water Shortage: An Update on the Role of K+, Cl-, and Water Membrane Transport Mechanisms on Drought Resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Xu, H.; Ai, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Geissen, V.; Ritsema, C.J.; Sha, X. Impacts of Extreme Weather Events on Terrestrial Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling: A Global Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; van Vliet, J.; Albert, J.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Huang, K. Rural Development Outpaces Urban Expansion in Threatening Biodiversity in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, F.; Lü, X.-T.; Ceulemans, T.; Zhao, C. Nitrogen Effects on Grassland Biomass Production and Biodiversity Are Stronger than Those of Phosphorus. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Ma, S.; Jiang, M. Co-Limitation of N and P Is More Prevalent in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau Grasslands. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1140462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, M.; Sheng, J.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, W.-H.; Bai, W. Aboveground Net Primary Productivity Was Not Limited by Phosphorus in a Temperate Typical Steppe in Inner Mongolia. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16, rtac085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; He, P.; Han, L.; Wei, X.; Feng, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Li, L.-J. Soil Nitrogen Availability and Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency Are Dependent More on Chemical Fertilization than Winter Drought in a Maize–Soybean Rotation System. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1304985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, C.; Wang, Y.; Ran, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y. Effects of Warming and Precipitation Change on Soil Nitrogen Cycles: A Meta-Analysis. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Sun, P.; Waring, B.G.; Fu, Z.; Reich, P.B. Alleviating Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Does Not Amplify Potassium-Induced Increase in Terrestrial Biomass. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Moorhead, D.L.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Mueller, C.W.; Ying, S.C.; Chen, J. Nitrogen Loading Enhances Phosphorus Limitation in Terrestrial Ecosystems with Implications for Soil Carbon Cycling. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 2845–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.Y.H. Plant Mixture Balances Terrestrial Ecosystem C:N:P Stoichiometry. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Philp, J.; Denton, M.D.; Huang, Y.; Wei, J.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q. Stoichiometric Homeostasis of N:P Ratio Drives Species-Specific Symbiotic N Fixation Inhibition under N Addition. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Tian, H.; Liao, H.; Pan, N.; Pan, S.; Ito, A.; Jain, A.K.; Kou-Giesbrecht, S.; Joos, F.; Sun, Q.; et al. Global Net Climate Effects of Anthropogenic Reactive Nitrogen. Nature 2024, 632, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Ma, F.; Quan, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Niu, S. Nitrogen Enrichment Alters Climate Sensitivity of Biodiversity and Productivity Differentially and Reverses the Relationship between Them in an Alpine Meadow. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Bahar, M.M.; Naidu, R. Diffuse Soil Pollution from Agriculture: Impacts and Remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Tian, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, S.; Guo, J.; Zhang, T. Effects of Warming and Nitrogen Addition on Soil Fungal and Bacterial Community Structures in a Temperate Meadow. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1231442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wu, H.; Zhao, A.-H.; Hao, Z.-P.; Chen, B.-D. Ecological Impacts of Nitrogen Deposition on Terrestrial Ecosystems: Research Progresses and Prospects. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2020, 44, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banegas, N.; Albanesi, A.S.; Pedraza, R.O.; Dos Santos, D.A. Non-Linear Dynamics of Litter Decomposition under Different Grazing Management Regimes. Plant Soil 2015, 393, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P.L.; Wilson, C.; Patterson, E.; Machmuller, M.B.; Cotrufo, M.F. Ruminating on Soil Carbon: Applying Current Understanding to Inform Grazing Management. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.; House, J.I.; Bustamante, M.; Sobocká, J.; Harper, R.; Pan, G.; West, P.C.; Clark, J.M.; Adhya, T.; Rumpel, C.; et al. Global Change Pressures on Soils from Land Use and Management. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 22, 1008–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qin, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z. Analysis of Characteristics of Land Use Change and Its Ecological Effects in the Datong River Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1590880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Gao, J. Precipitation and Soil Nutrients Determine the Spatial Variability of Grassland Productivity at Large Scales in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 996313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, T.W.; van den Hoogen, J.; Wan, J.; Mayes, M.A.; Keiser, A.D.; Mo, L.; Averill, C.; Maynard, D.S. The Global Soil Community and Its Influence on Biogeochemistry. Science 2019, 365, eaav0550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Qin, R.; Yang, J.; Fang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, S.; Li, F.-M. Soil Warming Decreases Carbon Availability and Reduces Metabolic Functions of Bacteria. CATENA 2023, 223, 106913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, N.A.; Songachan, L.S. Boosting Sustainable Agriculture by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi under Abiotic Stress Condition. Plant Stress. 2025, 17, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yuan, G.; Yang, X.; Fang, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wei, Z. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhance Soil Nutrient Cycling by Regulating Soil Bacterial Community Structures in Mango Orchards with Different Soil Fertility Rates. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1615694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tian, D.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; He, N.; Niu, S. Microbes Drive Global Soil Nitrogen Mineralization and Availability. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, E.; Müller, C.; Parisse, B.; Napoli, R.; Zhang, J.-B.; Rezanezhad, F.; Van Cappellen, P.; Moser, G.; Jansen-Willems, A.B.; Yang, W.H.; et al. A Global Dataset of Gross Nitrogen Transformation Rates across Terrestrial Ecosystems. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risch, A.C.; Zimmermann, S.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Schütz, M.; Frey, B.; Firn, J.L.; Fay, P.A.; Hagedorn, F.; Borer, E.T.; Seabloom, E.W.; et al. Soil Net Nitrogen Mineralisation across Global Grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, S.; Liu, J.; Song, T.; Lin, Y. Effects of Nitrogen Deposition on Microbial Communities in Grassland Ecosystems: Pronounced Responses of Archaea. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Bing, H.; Moorhead, D.L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Ye, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Guo, X.; et al. Ecoenzymatic Stoichiometry Reveals Widespread Soil Phosphorus Limitation to Microbial Metabolism across Chinese Forests. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, T.; Fu, Z.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Increasing the Nitrogen–Phosphorus Ratio on the Structure and Function of the Soil Microbial Community in the Yellow River Delta. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yang, D.; Deng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Guo, M.; Lu, Z.; et al. Phosphorus Uptake, Transport, and Signaling in Woody and Model Plants. For. Res. 2024, 4, e017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, F.; Li, Q.; Solanki, M.K.; Wang, Z.; Xing, Y.-X.; Dong, D.-F. Soil Phosphorus Transformation and Plant Uptake Driven by Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Jia, X.; Yu, N.; Murray, J.D.; Yi, K.; Wang, E. Microbe-Dependent and Independent Nitrogen and Phosphate Acquisition and Regulation in Plants. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaissoufi, W.; Khourchi, S.; Ibnyasser, A.; Ghoulam, C.; Rchiad, Z.; Zeroual, Y.; Lyamlouli, K.; Bargaz, A. Phosphate Solubilizing Rhizobacteria Could Have a Stronger Influence on Wheat Root Traits and Aboveground Physiology than Rhizosphere P Solubilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, A.; Roose, T.; Schweiger, P. Impact of Growth and Uptake Patterns of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Plant Phosphorus Uptake—A Modelling Study. Plant Soil 2008, 312, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, X.; Ludewig, U. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Colonization Outcompetes Root Hairs in Maize under Low Phosphorus Availability. Ann. Bot. 2020, 127, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yan, Y.; Dai, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Z.; Gan, F.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Response Characteristics of Dissolved Nitrogen and Phosphorus Migration to Outcrop Bedrock Pattern in Karst Slopes under Individual Rainfall. Catena 2024, 246, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargaz, A.; Elhaissoufi, W.; Khourchi, S.; Benmrid, B.; Borden, K.A.; Rchiad, Z. Benefits of Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria on Belowground Crop Performance for Improved Crop Acquisition of Phosphorus. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 252, 126842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Fang, L.; Xia, Z.; He, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Irrigation on Soil Phosphorus Fractions and Microbial Communities in Populus Euphratica Plantations. For. Res. 2023, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Asiegbu, F.O.; Wu, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, K.; Hong, L.; et al. Advances in the Beneficial Endophytic Fungi for the Growth and Health of Woody Plants. For. Res. 2024, 4, e028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, U.; Martinoia, E. Root Exudates: The Hidden Part of Plant Defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haichar, F.e.Z.; Santaella, C.; Heulin, T.; Achouak, W. Root Exudates Mediated Interactions Belowground. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Taylor, P.; Richter, A.; Porporato, A.; Ågren, G.I. Environmental and Stoichiometric Controls on Microbial Carbon-use Efficiency in Soils. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mganga, K.Z.; Sietiö, O.-M.; Meyer, N.; Poeplau, C.; Adamczyk, S.; Biasi, C.; Kalu, S.; Räsänen, M.; Ambus, P.; Fritze, H.; et al. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency along an Altitudinal Gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y. Increased Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency upon Abrupt Permafrost Thaw. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2419206122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdig, M.; Schleuss, P.M.; Biederman, L.A.; Borer, E.T.; Crawley, M.J.; Kirkman, K.P.; Seabloom, E.W.; Wragg, P.D.; Spohn, M. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency in Grassland Soils Subjected to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Additions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 146, 107815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Liu, J.; Lichtfouse, E.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, M.; Xiao, L. Soil Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency and the Constraints. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, D.; Ren, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, J. Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency of Soil Aggregates in Abandoned Grassland on the Loess Plateau of China. Forests 2022, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnecker, J.; Baldaszti, L.; Gündler, P.; Pleitner, M.; Sandén, T.; Simon, E.; Spiegel, F.; Spiegel, H.; Urbina Malo, C.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; et al. Seasonal Dynamics of Soil Microbial Growth, Respiration, Biomass, and Carbon Use Efficiency in Temperate Soils. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Jing, X.; Shen, Q.; He, J.-S.; Yang, Y.; Ling, N. Asymmetric Winter Warming Reduces Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency and Growth More than Symmetric Year-Round Warming in Alpine Soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401523121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Huang, Y.; Hungate, B.A.; Manzoni, S.; Frey, S.D.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Reichstein, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Ciais, P.; Jiang, L.; et al. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency Promotes Global Soil Carbon Storage. Nature 2023, 618, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Su, Y.; Li, X.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, P.; Gong, J.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, C.; et al. Arbuscular Mycorrhizae Mitigate Negative Impacts of Soil Biodiversity Loss on Grassland Productivity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouridis, A.; Hagen, J.A.; Kan, M.P.; Mambelli, S.; Feldman, L.J.; Herman, D.J.; Weber, P.K.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Firestone, M.K. Routes to Roots: Direct Evidence of Water Transport by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Host Plants. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuy-Velez, L.; Chakraborty, D.; Young, A.; Paudel, S.; Elvers, R.; Vanderhyde, M.; Walter, K.; Herzog, C.; Banerjee, S. Context-Dependent Contributions of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Host Performance under Global Change Factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 204, 109707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keymer, A.; Pimprikar, P.; Wewer, V.; Huber, C.; Brands, M.; Bucerius, S.L.; Delaux, P.-M.; Klingl, V.; von Röpenack-Lahaye, E.; Wang, T.L.; et al. Lipid Transfer from Plants to Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Fungi. Elife 2017, 6, e29107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Ray, R.; Halitschke, R.; Baldwin, G.; Baldwin, I.T. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi-Indicative Blumenol-C-Glucosides Predict Lipid Accumulations and Fitness in Plants Grown without Competitors. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 2159–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, B.; Chai, H.; Yang, X.; Song, W.; Li, S.; Lu, A.; Zhang, T.; Sun, W. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Alleviate Drought Stress in C3 (Leymus chinensis) and C4 (Hemarthria altissima) Grasses via Altering Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Photosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, T.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Glomalin Play a Crucial Role in Soil Aggregate Stability in Pb-Contaminated Soil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.; Martínez, C.E.; Kao-Kniffin, J. Three Important Roles and Chemical Properties of Glomalin-Related Soil Protein. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1418072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Kou, Y. Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: Participation in Nutrient Turnover and Community Assembly Pattern in Forest Ecosystems. Forests 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Salmerón, L.; Fernández-Boy, E.; Madejón, E.; Domínguez, M.T. Soil Legacy and Organic Amendment Role in Promoting the Resistance of Contaminated Soils to Drought. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 195, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-X.; Peng, Y.; Yang, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Dong, Q.; Li, Q.-S.; Han, X.-G.; Gao, C. Nitrogen Addition Alters Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Soil Bacteria Networks without Promoting Phosphorus Mineralization in a Semiarid Grassland. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzki, W.; Gutierrez Mañero, F.J.; Algar, E.; Lucas García, J.A.; García-Villaraco, A.; Ramos Solano, B. Bacterial Siderophores Efficiently Provide Iron to Iron-Starved Tomato Plants in Hydroponics Culture. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 104, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Medina, I.; Romero-Perdomo, F.; Molano-Chavez, L.; Gutiérrez, A.Y.; Silva, A.M.M.; Estrada-Bonilla, G. Inoculation of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria Improves Soil Phosphorus Mobilization and Maize Productivity. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 126, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papade, S.E.; Mohapatra, B.; Phale, P.S. Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter Spp. Capable of Metabolizing Aromatics Displays Multifarious Plant Growth Promoting Traits: Insights on Strategizing Consortium-Based Application to Agro-Ecosystems. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Li, C.-H.; Ali, Q.; Zhao, W.; Chi, Y.-K.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, F.; Yu, X.-Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, J.-T.; et al. Bacterial and Fungal Biocontrol Agents for Plant Disease Protection: Journey from Lab to Field, Current Status, Challenges, and Global Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.W.; Yan, W.H.; Xia, Y.T.; Tsim, K.W.K.; To, J.C.T. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Enhance Active Ingredient Accumulation in Medicinal Plants at Elevated CO2 and Are Associated with Indigenous Microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1426893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Rehman, H.M.; Ahmed, N.; Nawaz, S.; Saleem, F.; Ahmad, S.; Uzair, M.; Rana, I.A.; Atif, R.M.; Zaman, Q.U.; et al. Using Exogenous Melatonin, Glutathione, Proline, and Glycine Betaine Treatments to Combat Abiotic Stresses in Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, G.S.; Rondina, A.B.L.; Santos, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Pointing out Opportunities to Increase Grassland Pastures Productivity via Microbial Inoculants: Attending the Society’s Demands for Meat Production with Sustainability. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M.; Ballard, R.A.; Wright, D. Soil Microbial Inoculants for Sustainable Agriculture: Limitations and Opportunities. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil Microbiomes and Climate Change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, E. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis in Plant Growth and Stress Adaptation: From Genes to Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 569–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; de Jonge, R.; Liu, C.; Jiang, H.; Friman, V.-P.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Jousset, A. Rapid Evolution of Bacterial Mutualism in the Plant Rhizosphere. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Shi, X. Nitrogen-Induced Soil Acidification Reduces Soil Carbon Persistence by Shifting Microbial Keystone Taxa and Increasing Calcium Leaching. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaret, M.; Kinkel, L.; Borer, E.T.; Seabloom, E.W. Soil Nutrients Cause Threefold Increase in Pathogen and Herbivore Impacts on Grassland Plant Biomass. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Tanaka, K.; Khan, M. Biocontrol Efficacy of Pochonia Chlamydosporia against Root-Knot Nematode Meloidogyne Javanica in Eggplant and Its Impact on Plant Growth. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ruijven, J.; Ampt, E.; Francioli, D.; Mommer, L. Do Soil-Borne Fungal Pathogens Mediate Plant Diversity–Productivity Relationships? Evidence and Future Opportunities. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, J.S.; Fergus, A.J.F.; Turnbull, L.A.; Schmid, B. Janzen-Connell Effects Are Widespread and Strong Enough to Maintain Diversity in Grasslands. Ecology 2008, 89, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granjel, R.R.; Allan, E.; Godoy, O. Nitrogen Enrichment and Foliar Fungal Pathogens Affect the Mechanisms of Multispecies Plant Coexistence. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 2332–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Nie, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, S. Fungal Pathogens Increase Community Temporal Stability through Species Asynchrony Regardless of Nutrient Fertilization. Ecology 2023, 104, e4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekberg, Y.; Arnillas, C.A.; Borer, E.T.; Bullington, L.S.; Fierer, N.; Kennedy, P.G.; Leff, J.W.; Luis, A.D.; Seabloom, E.W.; Henning, J.A. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization Consistently Favor Pathogenic over Mutualistic Fungi in Grassland Soils. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, R.; Shang, P.; Wang, Y.; Nan, Z.; Duan, T. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Reshapes the Rhizosphere Microbiome of Alfalfa in Response to Above-Ground Attack by Aphids and a Fungal Plant Pathogen. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 2149–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhu, B. Patterns of Soil Respiration and Its Temperature Sensitivity in Grassland Ecosystems across China. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 5329–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhou, T.; Cao, L.; Yu, Y.; Tan, E.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y.; et al. Various Responses of Global Heterotrophic Respiration to Variations in Soil Moisture and Temperature Enhance the Positive Feedback on Atmospheric Warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, B.B.; Soper, F.M.; Nasto, M.K.; Bru, D.; Hwang, S.; Machmuller, M.B.; Morales, M.L.; Philippot, L.; Sullivan, B.W.; Asner, G.P.; et al. Litter Inputs Drive Patterns of Soil Nitrogen Heterogeneity in a Diverse Tropical Forest: Results from a Litter Manipulation Experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 108247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Zeng, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Phosphorus Dynamics in Litter–Soil Systems during Litter Decomposition in Larch Plantations across the Chronosequence. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1010458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, K.M.; Kyker-Snowman, E.; Grandy, A.S.; Frey, S.D. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency: Accounting for Population, Community, and Ecosystem-Scale Controls over the Fate of Metabolized Organic Matter. Biogeochemistry 2016, 127, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börger, M.; Bublitz, T.; Dyckmans, J.; Wachendorf, C.; Joergensen, R.G. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency of Litter with Distinct C/N Ratios in Soil at Different Temperatures, Including Microbial Necromass as Growth Component. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, F.M.; Torn, M.S.; Trumbore, S.E. Warming Accelerates Decomposition of Decades-Old Carbon in Forest Soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1753–E1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Hu, N.; Hou, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Kong, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Long-Term Overgrazing-Induced Memory Decreases Photosynthesis of Clonal Offspring in a Perennial Grassland Plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yang, J.; Dong, S.; He, F.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Grazing Intensity on Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Grassland of China: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. The Impact of Different Grazing Intensity and Management Measures on Soil Organic Carbon Density in Zhangye Grassland. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, D.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, C.; An, S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Communities and Glomalin Mediate Particulate and Mineral-Associated Organic Carbon Formation in Grassland Patches. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories—IPCC; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture. UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/agriculture/KJWA?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Wu, L.; Weston, L.A.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, X. Editorial: Rhizosphere Interactions: Root Exudates and the Rhizosphere Microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1281010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, N.; Hanzelková, V.; Dostálek, T.; Semerád, J.; Schnablová, R.; Cajthaml, T.; Münzbergová, Z. Species Phylogeny, Ecology, and Root Traits as Predictors of Root Exudate Composition. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, B.W.; Li, J.; Koch, B.J.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Dijkstra, P.; Hayer, M.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Liu, X.-J.A.; Mau, R.L.; Morrissey, E.M.; et al. Nutrients Cause Consolidation of Soil Carbon Flux to Small Proportion of Bacterial Community. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.; Rousk, J. Microbial Growth and Carbon Use Efficiency in Soil: Links to Fungal-Bacterial Dominance, SOC-Quality and Stoichiometry. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 131, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Pold, G.; Liu, X.-J.A.; Frey, S.D.; Melillo, J.M.; DeAngelis, K.M. Microbial Diversity Drives Carbon Use Efficiency in a Model Soil. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Cui, Q.; Gao, J. Latitudinal, Soil and Climate Effects on Key Leaf Traits in Northeastern China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Lv, C.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, J. Climatic Factors Determine the Distribution Patterns of Leaf Nutrient Traits at Large Scales. Plants 2022, 11, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-Y.; Li, Z.-T.; Xu, T.; Lou, A. Leaf Litter Decomposition Characteristics and Controlling Factors across Two Contrasting Forest Types. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Li, D.; Han, Y.; Hu, T.; Yang, G.; Sun, L. Changes in Above- and below-Ground Biodiversity Mediate Understory Biomass Response to Prescribed Burning in Northeast China. Plant Soil 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bhoi, T.K.; Vyas, V. Interceding Microbial Biofertilizers in Agroforestry System for Enhancing Productivity. In Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms of Arid Region; Mawar, R., Sayyed, R.Z., Sharma, S.K., Sattiraju, K.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 161–183. ISBN 978-981-19-4124-5. [Google Scholar]

- Erdenebileg, E.; Wang, C.; Yu, W.; Ye, X.; Pan, X.; Huang, Z.; Liu, G.; Cornelissen, J.H.C. Carbon versus Nitrogen Release from Root and Leaf Litter Is Modulated by Litter Position and Plant Functional Type. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, M.; Su, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Shang, J.; Gao, J. Leaf Nutrient Traits of Planted Forests Demonstrate a Heightened Sensitivity to Environmental Changes Compared to Natural Forests. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1372530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, F.; Mu, Y.; Bao, H.; Ma, Z.; Chu, C.; Yang, Y. Plant–Microbe Interactions Drive the Rhizosphere Microbial Assembly and Nitrogen Cycling in a Subtropical Forest. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 1274–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z. Meta-Analysis Shows Positive Effects of Plant Diversity on Microbial Biomass and Respiration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, J.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Ding, L.; Lu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Han, S.; et al. Biodiversity Mitigates Drought Effects in the Decomposer System across Biomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2313334121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Knops, J.M.H. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Stability in a Decade-Long Grassland Experiment. Nature 2006, 441, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Xu, K.; Qian, Y. Ecological Network Resilience Evaluation and Ecological Strategic Space Identification Based on Complex Network Theory: A Case Study of Nanjing City. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brose, U.; Hirt, M.R.; Ryser, R.; Rosenbaum, B.; Berti, E.; Gauzens, B.; Hein, A.M.; Pawar, S.; Schmidt, K.; Wootton, K.; et al. Embedding Information Flows within Ecological Networks. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 9, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S.; Liu, S.; Stirling, E.; Gilbert, J.A.; Faust, K.; Knight, R.; Jansson, J.K.; Cardona, C.; et al. Earth Microbial Co-Occurrence Network Reveals Interconnection Pattern across Microbiomes. Microbiome 2020, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Zobel, M. How Mycorrhizal Associations Drive Plant Population and Community Biology. Science 2020, 367, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifuddin, M.; Bhatnagar, J.M.; Segrè, D.; Finzi, A.C. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency Predicted from Genome-Scale Metabolic Models. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, S.; Song, M.; Wang, C.; Dou, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Zhu, C.; Wang, S. Decrease of Nitrogen Cycle Gene Abundance and Promotion of Soil Microbial-N Saturation Restrain Increases in N2O Emissions in a Temperate Forest with Long-Term Nitrogen Addition. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, O.J. Grassland Ecosystems in China: Review of Current Knowledge and Research Advancement. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tian, L.; Qu, G.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J. Precipitation Alters the Effects of Temperature on the Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Alpine Meadows. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 824296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ri, X.; Qu, S.; Li, F.; Wei, D.; Borjigidai, A. Plant Nitrogen Retention in Alpine Grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau under Multi-Level Nitrogen Addition. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Yu, M.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.; Huang, Y.; Su, W.; Xia, F.; Chang, S.X.; Brookes, P.C.; Dahlgren, R.A.; et al. Elevated Temperature Shifts Soil N Cycling from Microbial Immobilization to Enhanced Mineralization, Nitrification and Denitrification across Global Terrestrial Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 5267–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Shang, J.; Gao, J. Climate Factors Influence Above- and Belowground Biomass Allocations in Alpine Meadows and Desert Steppes through Alterations in Soil Nutrient Availability. Plants 2024, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Kreuter, U. Managing Grazing to Restore Soil Health, Ecosystem Function, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 534187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Ma, T.; Duo, L.; Zhang, X.; Fu, G. Grazing Intensity Modifies Soil Microbial Diversity and Their Co-Occurrence Networks in an Alpine Steppe, Central Tibet. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musawi, Z.K.; Vona, V.; Kulmány, I.M. Utilizing Different Crop Rotation Systems for Agricultural and Environmental Sustainability: A Review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X. Net Primary Productivity Exhibits a Stronger Climatic Response in Planted versus Natural Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 529, 120722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasar, B.J.; Kashyap, S.; Sharma, I.; Marme, S.D.; Das, P.; Agarwala, N. Microbe Mediated Alleviation of Drought and Heat Stress in Plants- Current Understanding and Future Prospects. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Togeto, B.Y. Research on Improving Degenerative Steppe and Methods for Increasing Productivity of the Steppe Region. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 1989, 13, 379. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Hu, B.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, Z.; He, Y.; Peng, J. Desert Soil Salinity Inversion Models Based on Field in Situ Spectroscopy in Southern Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.; Bowker, M.; Zhang, Y.; Belnap, J. Natural Recovery of Biological Soil Crusts after Disturbance. In Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands; Weber, B., Büdel, B., Belnap, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 479–498. ISBN 978-3-319-30214-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, O.; Deyn, G.B.D.; Ploeg, M. van der Soil Microbiota as Game-Changers in Restoration of Degraded Lands. Science 2022, 375, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Abs, E.; Allison, S.D.; Tao, F.; Huang, Y.; Manzoni, S.; Abramoff, R.; Bruni, E.; Bowring, S.P.K.; Chakrawal, A.; et al. Emerging Multiscale Insights on Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency in the Land Carbon Cycle. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Deng, L.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Peñuelas, J.; Liao, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Global Change Modulates Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency: Mechanisms and Impacts on Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetterl, S.; Berhe, A.A.; Arnold, C.; Bodé, S.; Fiener, P.; Finke, P.; Fuchslueger, L.; Griepentrog, M.; Harden, J.W.; Nadeu, E.; et al. Links among Warming, Carbon and Microbial Dynamics Mediated by Soil Mineral Weathering. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gnecco, G.; Smalla, K.; Maccario, L.; Sørensen, S.J.; Barbieri, P.; Consolo, V.F.; Covacevich, F.; Babin, D. Microbial Community Analysis of Soils under Different Soybean Cropping Regimes in the Argentinean South-Eastern Humid Pampas. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderoli, P.A.; Collavino, M.M.; Behrends Kraemer, F.; Morrás, H.J.M.; Aguilar, O.M. Analysis of nifH-RNA Reveals Phylotypes Related to Geobacter and Cyanobacteria as Important Functional Components of the N2-Fixing Community Depending on Depth and Agricultural Use of Soil. Microbiol. Open 2017, 6, e00502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.E.; Day, N.J.; DeVan, M.R.; Taylor, D.L. Wildfire Impacts on Root-Associated Fungi and Predicted Plant–Soil Feedbacks in the Boreal Forest: Research Progress and Recommendations. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 2110–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Raven, J.A.; Shaver, G.R.; Smith, S.E. Plant Nutrient-Acquisition Strategies Change with Soil Age. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-X.; Chen, S.-J.; Hong, X.-Y.; Wang, L.-Z.; Wu, H.-M.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.-Y.; Hao, G.-F. Plant Exudates-Driven Microbiome Recruitment and Assembly Facilitates Plant Health Management. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 49, fuaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; de Vries, F.T. Plant Root Exudation under Drought: Implications for Ecosystem Functioning. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Hu, J.; Peng, S.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Moorhead, D.L.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Xu, X.; Geyer, K.M.; Fang, L.; Smith, P.; et al. Limiting Resources Define the Global Pattern of Soil Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2308176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Geng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Bian, C.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Jiang, D.; Xu, X. Global Negative Effects of Nutrient Enrichment on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, Plant Diversity and Ecosystem Multifunctionality. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Dong, S.; Shen, H.; Li, S.; Wessell, K.; Liu, S.; Li, W.; Zhi, Y.; Mu, Z.; Li, H. N Addition Overwhelmed the Effects of P Addition on the Soil C, N, and P Cycling Genes in Alpine Meadow of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 860590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, J.; Ren, S. The Impact of Global Change Factors on the Functional Genes of Soil Nitrogen and Methane Cycles in Grassland Ecosystems: A Meta-Analysis. Oecologia 2024, 207, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, O.; Sardans, J.; Maspons, J.; Molowny-Horas, R.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Janssens, I.A.; Richter, A.; Ciais, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Peñuelas, J. The Effect of Global Change on Soil Phosphatase Activity. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5989–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes-Bassett, V.; Blackwell, M.S.A.; Blair, G.; Davies, J.; Haygarth, P.M.; Mezeli, M.M.; Stewart, G. A Meta-Analysis of Phosphatase Activity in Agricultural Settings in Response to Phosphorus Deficiency. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 165, 108537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Ning, D.; Zhou, X.; Feng, J.; Yuan, M.M.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Gao, Z.; et al. Reduction of Microbial Diversity in Grassland Soil Is Driven by Long-Term Climate Warming. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chang, S.X.; Liang, C.; An, S. Negative Effects of Multiple Global Change Factors on Soil Microbial Diversity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, W. Independent and Interactive Effects of Precipitation Intensity and Duration on Soil Microbial Communities in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems of China: A Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdig, M.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Schleuss, P.-M.; Guhr, A.; Borer, E.T.; Seabloom, E.W.; Spohn, M. Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Addition on Microbial Community Composition and Element Cycling in a Grassland Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.F.; Siguenza, N.; Zhong, W.; Mohanty, I.; Lingaraju, A.; Richter, R.A.; Karthikeyan, S.; Lukowski, A.L.; Zhu, Q.; Nunes, W.D.G.; et al. Metatranscriptomics Uncovers Diurnal Functional Shifts in Bacterial Transgenes with Profound Metabolic Effects. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1057–1072.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, M.; Muth, T. Integrated Multi-Omics Analyses of Microbial Communities: A Review of the Current State and Future Directions. Mol. Omics 2023, 19, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherati, S.R.; Khodakovskaya, M.V. Integration of Transcriptomics and Proteomics Data for Understanding the Mechanisms of Positive Effects of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials on Plant Tolerance to Salt Stress. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 3772–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccio, E.E.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Lafler, M.; Campbell, A.N.; Kakouridis, A.; Kimbrel, J.A.; Wollard, J.; Vyshenska, D.; Riley, R.; Tomatsu, A.; et al. HT-SIP: A Semi-Automated Stable Isotope Probing Pipeline Identifies Cross-Kingdom Interactions in the Hyphosphere of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Microbiome 2022, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Yin, C.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, A.; Wakelin, S.A.; Zou, J.; Liang, Y. Probing Potential Microbial Coupling of Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling during Decomposition of Maize Residue by 13C-DNA-SIP. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 70, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, L.B.; Sharp, E.J.; Letts, M.G. Response of Plant Biomass and Soil Respiration to Experimental Warming and Precipitation Manipulation in a Northern Great Plains Grassland. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 173, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, B.J.; Simard, S.W. Chapter 18—Mycorrhizal Networks and Forest Resilience to Drought. In Mycorrhizal Mediation of Soil; Johnson, N.C., Gehring, C., Jansa, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 319–339. ISBN 978-0-12-804312-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Dong, L.; Wang, W. Grassland Degradation Amplifies the Negative Effect of Nitrogen Enrichment on Soil Microbial Community Stability. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.M.; Glaum, P.; Valdovinos, F.S. Interpreting Random Forest Analysis of Ecological Models to Move from Prediction to Explanation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magney, T.S.; Bowling, D.R.; Logan, B.A.; Grossmann, K.; Stutz, J.; Blanken, P.D.; Burns, S.P.; Cheng, R.; Garcia, M.A.; Köhler, P.; et al. Mechanistic Evidence for Tracking the Seasonality of Photosynthesis with Solar-Induced Fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11640–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, E.P.; Shi, S.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Koch, B.J.; Probst, A.J.; Hungate, B.A.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Firestone, M.K.; Banfield, J.F. Stable-Isotope-Informed, Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Uncovers Potential Cross-Kingdom Interactions in Rhizosphere Soil. Msphere 2021, 6, e0008521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Verhoef, A.; Vereecken, H.; Ben-Dor, E.; Veldkamp, T.; Shaw, L.; Ploeg, M.V.D.; Wang, Y.; Su, Z. Monitoring and Modeling the Soil-Plant System toward Understanding Soil Health. Rev. Geophys. 2025, 63, e2024RG000836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ding, S.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, E.; Liu, T.; Duan, X. Microbial and Enzymatic C:N:P Stoichiometry Are Affected by Soil C:N in the Forest Ecosystems in Southwestern China. Geoderma 2024, 443, 116819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Cumbo, F.; Angione, C. Ten Quick Tips for Avoiding Pitfalls in Multi-Omics Data Integration Analyses. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y. Carbon Sink Potential and Contributions to Dual Carbon Goals of the Grain for Green Program in the Arid Regions of Northwest China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 220, 108355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q.; Ling, N.; Guo, J. Enhanced Carbon Use Efficiency and Warming Resistance of Soil Microorganisms under Organic Amendment. Environ. Int. 2024, 192, 109043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, N.; Lanoue, A.; Strecker, T.; Scheu, S.; Steinauer, K.; Thakur, M.P.; Mommer, L. Root Biomass and Exudates Link Plant Diversity with Soil Bacterial and Fungal Biomass. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Kumar, S.; Sheikh, I.; Kour, D.; Yadav, A.N. Microbial Consortium with Nitrogen Fixing and Mineral Solubilizing Attributes for Growth of Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Heliyon 2022, 8, e09326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Kou, T.; Cong, M.; Jia, Y.; Yan, H.; Huang, X.; Yang, Z.; An, S.; Jia, H. Grassland Degradation-Induced Soil Organic Carbon Loss Associated with Micro-Food Web Simplification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 201, 109659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Shi, L.; He, Y.; Peng, C.; Lin, Z.; Hu, M.; Yin, N.; Xu, H.; Zhang, D.; Shao, X. Grazing Intensity, Duration, and Grassland Type Determine the Relationship between Soil Microbial Diversity and Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Chinese Grasslands: A Meta-Analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.; Panhölzl, C.; Angel, R.; Giguere, A.T.; Randi, D.; Hausmann, B.; Herbold, C.W.; Pötsch, E.M.; Schaumberger, A.; Eichorst, S.A.; et al. Plant Roots Affect Free-Living Diazotroph Communities in Temperate Grassland Soils despite Decades of Fertilization. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Kuhn, T.; Lehmann, M.F.; Müller, C.; Gonzalez, O.; Eisenhauer, N.; Lange, M.; Scheu, S.; Oelmann, Y.; Wilcke, W. The Biodiversity—N Cycle Relationship: A 15N Tracer Experiment with Soil from Plant Mixtures of Varying Diversity to Model N Pool Sizes and Transformation Rates. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Picon-Cochard, C.; Augusti, A.; Benot, M.-L.; Thiery, L.; Darsonville, O.; Landais, D.; Piel, C.; Defossez, M.; Devidal, S.; et al. Elevated CO2 Maintains Grassland Net Carbon Uptake under a Future Heat and Drought Extreme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 6224–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Chiariello, N.R.; Tobeck, T.; Fukami, T.; Field, C.B. Nonlinear, Interacting Responses to Climate Limit Grassland Production under Global Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10589–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, C. Interactive Effects of Elevated Temperature and Drought on Plant Carbon Metabolism: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2824–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Gao, J.; Liu, Q.; Su, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xie, P.; Xin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wan, P.; et al. Optimizing Forest Structure for Sustainability: A Review of Structure-Based Management Effects on Stand Quality. For. Res. 2025, 5, e023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Gao, H.; Pan, H.; Qi, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Wei, G.; Jiao, S. Environmental Change Legacies Attenuate Disturbance Response of Desert Soil Microbiome and Multifunctionality. Funct. Ecol. 2024, 38, 1104–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Rong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, L. The Relationship of Gross Primary Productivity with NDVI Rather than Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Is Weakened under the Stress of Drought. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Leff, J.W.; Adams, B.J.; Nielsen, U.N.; Bates, S.T.; Lauber, C.L.; Owens, S.; Gilbert, J.A.; Wall, D.H.; Caporaso, J.G. Cross-Biome Metagenomic Analyses of Soil Microbial Communities and Their Functional Attributes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21390–21395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, J.W.; Jones, S.E.; Prober, S.M.; Barberán, A.; Borer, E.T.; Firn, J.L.; Harpole, W.S.; Hobbie, S.E.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Knops, J.M.H.; et al. Consistent Responses of Soil Microbial Communities to Elevated Nutrient Inputs in Grasslands across the Globe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10967–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.A.; Martiny, J.B.H.; Brodie, E.L.; Martiny, A.C.; Treseder, K.K.; Allison, S.D. Defining Trait-Based Microbial Strategies with Consequences for Soil Carbon Cycling under Climate Change. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | What It Captures | Recent Quantitative/Directional Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial CUE | Balance of biomass production vs. respiration; predictor of SOC retention | Global analyses: microbial CUE is a dominant control on SOC storage: a 2% increase in CUE can raise global SOC by ~10%, and CUE is at least four times as important as other evaluated factors (carbon inputs, decomposition rates, etc.) in explaining SOC variation [99,189]. |

| AMF status (diversity/abundance) | Strength of mutualist network | A global meta-analysis nutrient enrichment significantly reduced AMF diversity (by 12–20%) and abundance, with root colonization, spore density, and extrarhioidal hyphae decreasing by approximately 18–25%, 15–30%, and 20–40%, respectively. This negative effect was further exacerbated with longer trial durations and higher MAT and MAP [190]. |

| nifH abundance | Proxy for biological N fixation capacity | In multiple grassland fertilization experiments, especially under relatively high N inputs, N addition often reduces diazotrophic nifH gene abundance by ~30–50% [191]. However, a recent grassland meta-analysis found no consistent overall response of N-fixation genes to global change factors, suggesting strong Environmental dependence [192]. |

| Phosphatase activity | P-mineralization potential, P stress signal | Phosphatase activity rises under P limitation and declines with P addition: meta-analyses show monoesterase activity increases by ~+70% under low P but decreases by ~−20% with inorganic P fertilization [193,194] |

| Microbial network complexity (connectance/modularity) | Community robustness, multifunctionality under stress | Long-term warming experiments in grasslands show consistent losses of soil microbial biodiversity, with bacterial, fungal and protistan richness decreasing by ~8–15% under experimental warming [195], and global meta-analyses reporting average declines of 2–4% across multiple global change drivers [196]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, X.; Fan, Y.; Gao, J. From Microbial Functions to Measurable Indicators: A Framework for Predicting Grassland Productivity and Stability. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122765

Yang Y, Zhang X, Du X, Fan Y, Gao J. From Microbial Functions to Measurable Indicators: A Framework for Predicting Grassland Productivity and Stability. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122765

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yishu, Xing Zhang, Xiaoxuan Du, Yuchuan Fan, and Jie Gao. 2025. "From Microbial Functions to Measurable Indicators: A Framework for Predicting Grassland Productivity and Stability" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122765

APA StyleYang, Y., Zhang, X., Du, X., Fan, Y., & Gao, J. (2025). From Microbial Functions to Measurable Indicators: A Framework for Predicting Grassland Productivity and Stability. Agronomy, 15(12), 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122765