Abstract

Brassinazole-resistant (BZR) gene is a key transcription factor in the brassinosteroid signaling pathway and plays a critical role in regulating plant growth, development, and environmental stress responses. However, systematic studies on the BZR gene family in grape remain limited. In this study, eight BZR genes were identified in the grape genome, which were unevenly distributed across seven chromosomes and classified into four subfamilies. Bioinformatics analysis was performed to characterize their physicochemical properties, conserved motifs, chromosomal locations, and expression across tissues and in response to hormones. Further experimental results showed that VvBZR7 expression is induced by brassinosteroid and its inhibitor. Subcellular localization confirmed that VvBZR7 is localized in the nucleus. Transient overexpression assays demonstrated that VvBZR7 promotes the degradation of cell wall components, which reduces fruit firmness and consequently accelerates softening. These findings establish a foundation for elucidating the functional roles and regulatory mechanisms of the BZR gene family in grapevine.

1. Introduction

Plant hormones are critical regulators of plant growth, development, and stress adaptation. Brassinosteroids (BRs), a class of plant growth regulators, participate in multiple cellular signaling pathways. They are recognized as the sixth naturally occurring plant hormone, following auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, abscisic acid, and ethylene [1]. Although present at significantly lower concentrations than the other five major plant hormones, BRs exhibit greater efficacy in modulating growth and developmental processes [2]. Studies have shown that BRs are involved in a range of physiological processes, including cell elongation, stomatal development, flowering regulation, seed morphology determination, leaf senescence, and stress resistance [3,4,5,6,7]. In recent years, the integration of molecular genetics, biochemistry, genomics, and proteomics has enabled the systematic elucidation of the BR signaling pathway and its associated regulatory networks [8].

BZR transcription factors serve as core components and downstream regulators in the brassinosteroid (BR) signaling cascade [9]. They modulate plant growth and development under abiotic stress by controlling the expression of BR-responsive genes [10]. The BR signaling pathway is initiated when BR signals are perceived by the plasma membrane-localized receptors BRI1 (Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1) and its co-receptor BAK1 (BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1). This recognition triggers the activation of the phosphatase BSU1 (BR-Suppressor 1), which subsequently dephosphorylates and inactivates the kinase BIN2 (BR-Insensitive 2). Inactivation of BIN2 leads to the accumulation of dephosphorylated transcription factors BZR1 (Brassinazole Resistant 1) and BES1 (BRI1-EMS-Suppressor 1) in the nucleus. These transcription factors then bind to specific cis-acting elements—BRRE (CGTGT/CG) and E-box (CANNTG)—in the promoters of target genes, ultimately regulating the expression of BR-responsive genes [11,12,13,14,15].

BZR is a plant-specific transcription factor and the only identified TF in the BR signaling pathway, first discovered in Arabidopsis thaliana. The AtBZR gene family consists of six members: BZR1, BES1, and four BES1/BZR1 homologs (BEH1–BEH4) [14]. BES1 is the closest homolog to BZR1, sharing 88% overall amino acid sequence identity. The DNA-binding domain of BZR proteins typically contains an atypical basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) structure [16]. With advancing research, the functional characterization of BZR transcription factors has become increasingly comprehensive. Model plants such as A. thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum have made major contributions to dissecting BR signaling and BZR-mediated transcriptional networks, providing a conceptual framework for extending BZR functional studies to horticultural crops and other non-model species. For instance, in A. thaliana, AtBZR1 upregulates PAP1 expression and directly interacts with the PAP1 protein to enhance the transcription of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes [17]. In pear, PuBZR1 indirectly suppresses the transcription of PuACO1 and PuACS1a by modulating PuERF2, thereby reducing ethylene biosynthesis and delaying fruit ripening [18]. In maize, ZmBES1/BZR1-5 interacts with the casein kinase II subunit ZmCKIIβ4 and the ferredoxin protein ZmFdx2. By binding to AP2/EREBP gene promoter elements and repressing their transcription, it positively regulates kernel size [19]. BZR transcription factors also play essential regulatory roles in fruit development and ripening. In tomato, SlBZR1.7 promotes fruit elongation through positive regulation of SUN gene expression [20], whereas SlBZR1.3 acts as a master regulator that integrates BR signaling with epigenetic control, coordinating both transcription and chromatin remodeling to determine fruit size [21]. In persimmon, DkBZR1 and DkBZR2 regulate fruit ripening by controlling cell wall degradation and ethylene biosynthesis [22]. In loquat, EjBZR1 binds to the BR response element (CGTGTG) in the EjCYP90A promoter and downregulates its expression, thereby suppressing cell proliferation and fruit growth [23]. Despite these findings, the functional roles of the BZR gene family in most plant species remain poorly characterized, with research currently limited to only a few model and horticultural species.

Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) is a perennial vine and an economically important fruit crop widely cultivated throughout China, with high nutritional and commercial value [24]. The growth and development of grapevine are influenced by various internal and external factors, among which plant hormones play a critical regulatory role in both developmental processes and fruit quality formation. Previous studies have established that BZR transcription factors function as crucial components of the BR signaling pathway. However, systematic investigation of the BZR gene family in grapevine remains limited, necessitating further exploration of its functional characteristics. In this study, we identified eight VvBZR gene family members from the grape genome using bioinformatics approaches. Comprehensive analyses were conducted on their phylogenetic relationships, conserved protein motifs, chromosomal distributions, and promoter cis-acting elements. Furthermore, we examined their expression profiles across different tissues and in response to various hormone treatments. The biological function of VvBZR7 in grape fruit was experimentally investigated, providing important insights for further functional characterization of VvBZR genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The ‘Yinhong’ grapevine materials were obtained from Dicuiyuan Farm in Zhenhai District, Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province (120°32′ E, 29°52′ N). During July 2025, samples including stems, leaves, tendrils, seeds, fruit peel, and pulp were collected. Callus tissue was induced from Yinhong stem segments for 60 days. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently cultured and stored at −80 °C in ultra-low temperature freezers for subsequent analysis. Three independent biological replicates were prepared for each sample type to ensure the reliability of expression profiling for VvBZR gene family members across different tissues.

2.2. Identification and Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of the Grape BZR Gene

We downloaded the whole-genome and proteome data of grape from the Ensembl Plants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html, accessed on 26 May 2025), while the protein sequences of A. thaliana BZR transcription factors were downloaded from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/, version 10, accessed on 26 May 2025). A local BLASTP alignment was performed with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5. In parallel, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) of the BES1_N domain (PF05687) obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/, accessed on 26 May 2025) was used to search against the grape proteome using HMMER v3.3.2. Redundant sequences were removed to generate a non-redundant candidate set. All candidate proteins were further verified for the presence of the BES1_N domain using NCBI-CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd, accessed on 26 May 2025) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/, accessed on 26 May 2025). The final set of validated VvBZR proteins was systematically named according to their chromosomal positions. To characterize the physicochemical properties of the identified VvBZR proteins, amino acid length, molecular weight, and theoretical isoelectric point were calculated using the Expasy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 26 May 2025). Subcellular localization was predicted with Cell-PLoc 2.0 (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/Cell-PLoc-2/, accessed on 26 May 2025). Secondary structure composition, including α-helixes, beta turns, random coils, and extended strands, was analyzed using SOPMA (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/, accessed on 26 May 2025).

2.3. Phylogenetic Tree Construction, Conserved and Gene Structure Analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of BZR protein sequences from grape, A. thaliana, rice [25], tomato [26], and maize [27], as listed with their accession numbers in Supplementary Table S1, was conducted using Clustal X 1.81. A phylogenetic tree was subsequently constructed with MEGA 11.0 software using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree was visualized and annotated using the iTOL online platform (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 27 May 2025). Conserved motifs in VvBZR proteins were identified with the MEME online tool (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 27 May 2025), configured to detect 10 distinct motifs (designated Motif 1~10). Gene structure features of the VvBZR family were analyzed in TBtools (v.2.152) based on the genomic annotation information extracted from the grape GFF file.

2.4. Chromosome Localization and Colinearity Analysis

Chromosomal locations of VvBZR genes were determined using whole-genome sequences from the grape genome database. Genome synteny analysis among grape, A. thaliana, and tomato was performed using MCScanX, with results visualized through TBtools (v.2.152).

2.5. Cis-Acting Element Analysis

Submit the 2000 bp upstream sequence of the VvBZRs coding region to the PlantCARE software (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html, accessed on 27 May 2025) to identify cis-acting elements, with results visualized using TBtools (v.2.152).

2.6. Grape RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from samples using the Rnaprep Pure polysaccharide polyphenol plant total RNA extraction kit (HuiLing, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from purified RNA using the NovoScript Plus All in one 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (gDNA Purge) reverse transcription kit (Novoprotein, Suzhou, China). Gene-specific primers for VvBZR family members were designed with NCBI Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/, accessed on 27 May 2025) (Table S2). qRT-PCR was performed using the NovoStart® SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus on a q225 fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Kubo, Guangzhou, China). Reaction system (10 μL): template cDNA 1 μL, 1 forward and 1 reverse primer each μL, 2× TransStart Tip Green qPCR SuperMix 5 μL, H2O replenishment to 10 μL. Reaction procedure: 95 °C pre-denaturation for 60 s; 95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 60 s, 45 cycles. All samples were analyzed with three biological replicates.

The relative expression levels of VvBZR genes were normalized to the reference genes VvActin and VvEF-α and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Statistical significance was determined with SPSS software 24.0 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Data visualization was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0.

2.7. Transcriptome Analysis

Based on previously obtained transcriptome data from our laboratory (PRJNA1175992, PRJNA1354666), we analyzed the expression patterns of VvBZR genes in grape pulp following treatments with brassinosteroids (BRs), brassinazole (BRZ), gibberellin (GA3), and sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Gene expression levels were quantified using FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads) values. Hierarchical clustering analysis and heatmap visualization were performed using Orange 2022 to display expression profiles across different VvBZR genes under various hormonal treatments.

2.8. Subcellular Localization Analysis

The coding sequence (CDS) of VvBZR7 was cloned and inserted into the pCAMBIA1300-35S-EGFP vector. Recombinant and empty control plasmids verified by sequencing were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 for subcellular localization analysis. Transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves was performed via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration following the method established by Hu et al. [28]. GFP fluorescence signals were observed using a Nikon A1R confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), with specific primers used for cloning listed in Table S2.

2.9. Construction of VvBZR7 Overexpression Vectors and Transient Transformation of Grapevine Berry

The VvBZR7 coding sequence was amplified and inserted into the pCAMBIA1300-35S-EGFP overexpression vector. The recombinant plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 via heat shock transformation. For transient transformation of grape berries, the method described by Chen et al. [29] was adopted with modifications. Agrobacterium cultures carrying the construct were resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM acetosyringone, 10 mM MES, pH 5.8) to OD600 = 0.6. Suspensions were injected into ‘Yinhong’ grape fruits, with sterile water injections serving as negative controls. The inoculated berry clusters were bagged and kept in darkness for 72 h before sampling. Successfully transformed berries were identified by PCR verification.

For subsequent analysis, total RNA was extracted from collected samples, and hemicellulose content was quantified. Fruit tissues were homogenized and treated with 95% ethanol to remove soluble sugars and impurities. Hemicellulose levels were determined using a Hemicellulose Content Assay Kit (SolaBio, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of the BZR Gene Family in Grape

Combining local BLAST and HMM search approaches, eight VvBZR genes were identified in the grape genome. The conserved BES1_N domain in all candidates was verified through CDD and SMART databases. These genes were systematically designated VvBZR1 to VvBZR8 according to their chromosomal positions. As summarized in Table 1, the encoded proteins vary in length from 137 to 699 amino acids, with molecular weights ranging from 15.54 to 78.78 KDa and theoretical pI values between 5.58 and 9.15. All VvBZRs exhibit instability indices above 40, indicating their classification as unstable proteins, and negative grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) values, consistent with hydrophilic characteristics. Subcellular localization predictions unanimously target these proteins to the nucleus, aligning with their putative roles as transcription factors. Secondary structure analysis revealed that VvBZR proteins are primarily composed of α-helix, random coils, and extended strands. Random coils represent the predominant structural element, while no beta turns were detected in any member of the family (Table S3).

Table 1.

Basic information on the BZR family in grape.

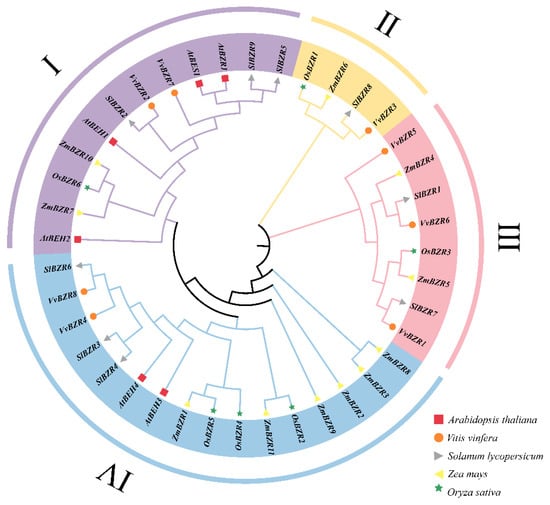

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of VvBZR Genes

To elucidate the evolutionary relationships of VvBZR genes, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using BZR protein sequences from grape, A. thaliana, tomato, rice, and maize (Figure 1). The BZR family was classified into four distinct subfamilies based on phylogenetic topology. Distribution analysis showed that subgroup III contained the highest number of VvBZR members (three), while subgroup II contained the fewest (one). Notably, VvBZR2 and VvBZR7 clustered within the same subfamily as AtBZR1 and AtBES1, which are core transcription factors in the A. thaliana BR signaling pathway. This conserved evolutionary relationship suggests that VvBZR2 and VvBZR7 may fulfill crucial regulatory functions in the BR signaling pathway of grape.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of BZR proteins from grape (Vv), A. thaliana (At), tomato (Sl), rice (Os), and maize (Zm). The tree is divided into four clades (I–IV), indicated by purple (Clade I), yellow (Clade II), pink (Clade III), and blue (Clade IV) colored branches.

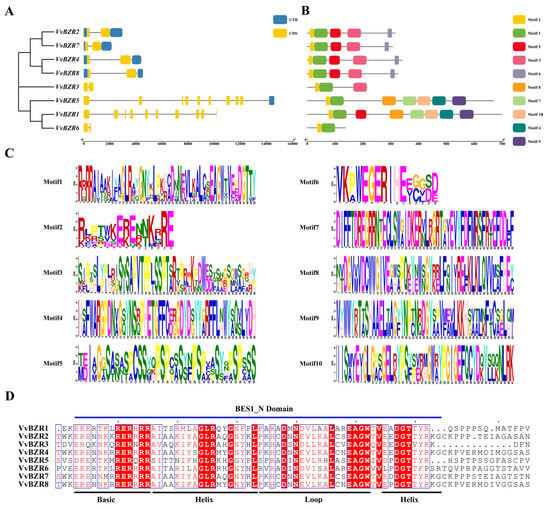

3.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of VvBZR Genes

Gene structure analysis provides important insights into functional differentiation and evolutionary relationships. All identified VvBZR genes were found to contain both exonic and intronic regions. Members within the same phylogenetic clade generally showed similar gene lengths and parallel organization of structural distributions. Specifically, all genes in subfamilies I and IV consistently contained two exons and two untranslated regions (UTRs). With the exception of VvBZR3, VvBZR1, and VvBZR6, all other family members possessed UTR sequences, reflecting evolutionary conservation within these subfamilies (Figure 2A). MEME-based motif prediction identified 10 conserved motifs across VvBZR proteins (Figure 2B,C). While motif composition and arrangement varied among different members, Motif1 and Motif2 were universally present in all VvBZR proteins. Additionally, the BES1_N domain (Figure 2D), essential for DNA binding, showed high sequence conservation across the VvBZR subfamilies, underscoring its fundamental role in BZR protein activity. Notably, proteins clustered within the same subfamily exhibited highly consistent patterns in motif type, quantity, and spatial organization, demonstrating significant structural conservation among evolutionarily related BZR members.

Figure 2.

Gene structure and conserved motifs of VvBZR genes. (A) Schematic representation of gene structures. Untranslated regions (UTRs) are shown in blue, coding sequences (CDS) in yellow, and introns are represented by lines. (B) Distribution of conserved motifs in VvBZR proteins. (C) Sequence logos of the identified conserved motifs. (D) Multiple sequence alignment of VvBZR proteins. The blue line represents the BES1_N domain, and the black line represents the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain. The symbol (·) indicates an interval of 10 amino acids.

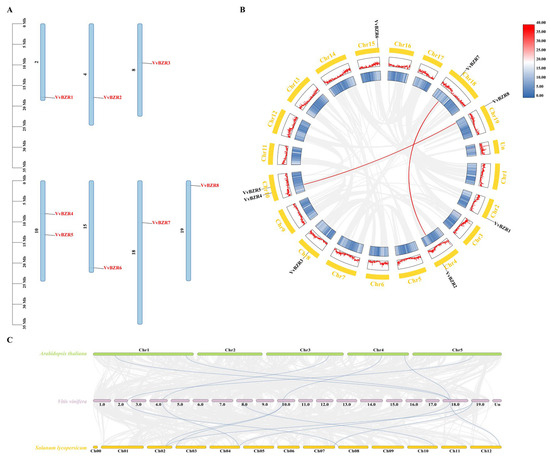

3.4. Distribution on Chromosomes and Collinear Analysis of VvBZR Proteins

Chromosomal localization analysis revealed that the eight identified VvBZR genes are distributed across seven grape chromosomes (Chr2, 4, 8, 10, 15, 18, and 19). Chromosome 10 contains the highest number of VvBZR genes (two), while the remaining six chromosomes each carry a single gene (Figure 3A). This uneven chromosomal distribution reflects the genetic diversity within the grape BZR gene family.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal distribution and synteny analysis of VvBZR genes. (A) Distribution of the VvBZR genes on chromosomes. The left scale indicates chromosome length. (B) Synteny relationships among BZR genes within grape. The gray lines indicate all syntenic pairs in V. vinifera and red lines indicate syntenic pairs in VvBZR members. (C) Synteny relationships among A. thaliana, S. lycopersicum and V. vinifera. Gray lines in the background indicate the collinear blocks within grape and other plant genomes, while blue lines highlight the syntenic BZR gene pairs.

Analysis of gene duplication events identified two collinear gene pairs (VvBZR2/7 and VvBZR4/8) within the grape genome, suggesting potential roles of both tandem and segmental duplications in the evolution of this gene family. No collinear relationships were detected among other VvBZR members (Figure 3B).

To further investigate evolutionary conservation, we constructed a synteny map of BZR genes across grape, A. thaliana, and tomato (Figure 3C). The analysis revealed six syntenic gene pairs between grape and A. thaliana, and nine pairs between grape and tomato. Notably, five VvBZR genes showed collinearity with both A. thaliana and tomato, indicating strong evolutionary conservation. Furthermore, VvBZR7 exhibited two homologous counterparts in both A. thaliana and tomato, suggesting its expansion during evolution through species-specific duplication events.

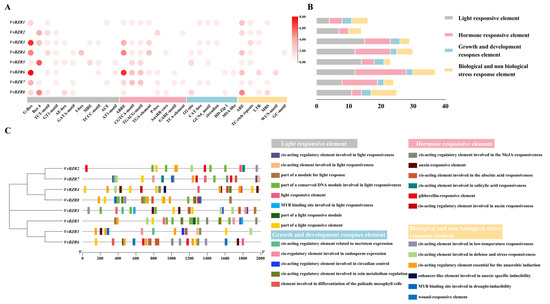

3.5. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Element in the Promoter Region of VvBZRs

To investigate the potential regulatory functions of the VvBZR gene family, we analyzed cis-acting elements in the 2000 bp promoter regions upstream of the coding sequences (Figure 4). These regulatory elements were classified into four major categories: light-responsive, hormone-responsive, growth and development-responsive, and biological and non-biological-responsive elements. Quantitative analysis revealed that light-responsive elements (41.9%) and hormone-responsive elements (30.3%) constituted the predominant types. All VvBZR promoters contained light-responsive elements, with G-box and Box-4 being the most prevalent. Hormone-responsive elements included recognition sites for multiple phytohormones: methyl jasmonate (TGACG-motif, CGTCA-motif), abscisic acid (ABRE), auxin (TGA-element, AuxRR-core), gibberellin (P-box, GARE-motif), and salicylic acid (TCA-element). Additionally, we identified elements associated with growth and developmental processes, including endosperm expression, metabolic regulation, circadian control, and meristem expression. Stress-responsive elements encompassed anaerobic induction (ARE), defense and stress response (TC-rich repeats), low temperature responsiveness (LTR), drought inducibility (MBS), and wound response (WUN-motif). These results indicate that VvBZR genes are likely involved in diverse biological processes, including hormone signaling, plant growth regulation, and stress adaptation, suggesting their crucial roles in mediating environment.

Figure 4.

Analysis of cis-acting elements in the promoters of VvBZR genes. (A) Types of cis-acting elements. (B) Number of cis-acting elements. (C) Positions of cis-acting elements within the promoter region.

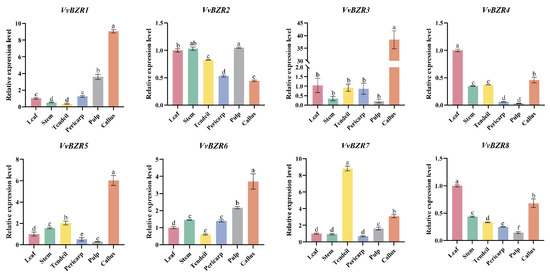

3.6. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression of VvBZRs Genes in Various Tissues

To investigate the expression patterns of the VvBZR gene family across different tissues, tissue-specific expression analysis was conducted in grape stems, leaves, tendrils, peel, pulp, and callus tissues, as shown in Figure 5. Analysis revealed significant expression differences in VvBZR genes across various tissues, likely due to their distinct functions in grapevine. VvBZR1, VvBZR3, VvBZR5, and VvBZR6 exhibited higher expression levels in callus tissue, with VvBZR3 showing the highest expression, indicating a specialized role in cell proliferation and differentiation. VvBZR2, VvBZR4, and VvBZR8 exhibited similar expression patterns with low levels across all tissues; VvBZR7 showed the highest expression in tendrils, suggesting its potential importance in meristem regulation and plant growth. In summary, these findings provide important clues for further research into the biological functions of the VvBZR gene family in grape development and adaptive regulation.

Figure 5.

Expression levels of VvBZR in different tissues. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between different tissues. Significant differences among the groups were compared based on Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

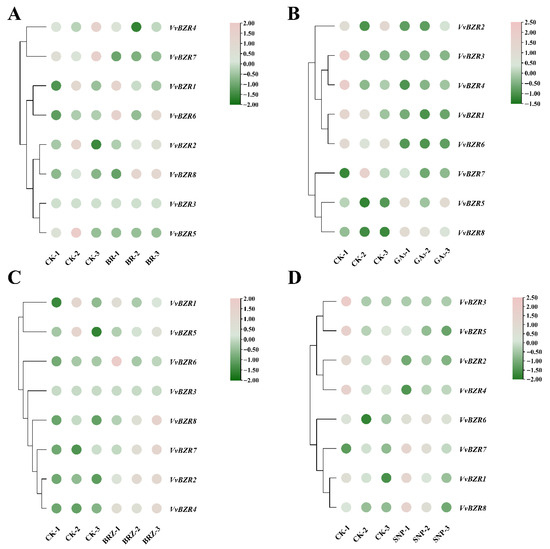

3.7. Expression Pattern of VvBZR Genes Under Hormone Treatment

Transcription factors play pivotal roles in multiple physiological processes during plant growth and development, with plant hormones acting as key signals that modulate their functional activities. Using transcriptomic data, we investigated the responses of VvBZR genes to treatments with brassinosteroids (BRs), brassinazole (BRZ), gibberellic (GA3), and sodium nitroprusside (SNP), as visualized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of VvBZR genes under different hormonal treatments. (A) Brassinosteroids (BRs). (B) Brassinazole (BRZ). (C) Gibberellin (GA3). (D) Sodium nitroprusside (SNP).

The results revealed distinct transcriptional responses among VvBZR members. VvBZR3 showed no significant expression changes under any treatment, whereas three genes (VvBZR4, VvBZR7, VvBZR8) were markedly regulated by all hormone treatments, suggesting their potential as core regulatory nodes in hormonal signaling networks. Notably, VvBZR8 was consistently upregulated across all treatments, indicating its broad responsiveness to multiple hormonal signals and a possible role in integrating their physiological effects. In contrast, VvBZR7 displayed opposing expression patterns under BR and BRZ treatments, implicating it as a specific responsive factor in the BR signaling pathway. These findings highlight the functional diversification of VvBZR genes in hormone-mediated regulatory networks and provide a foundation for further elucidating the mechanistic roles of VvBZR transcription factors in hormone signaling.

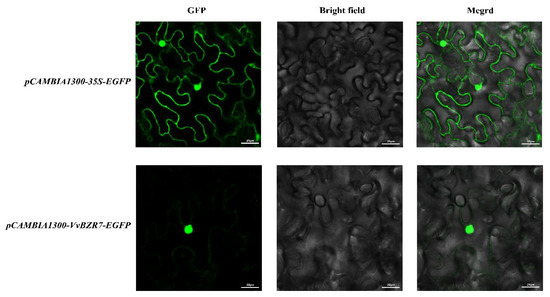

3.8. Subcellular Localization of the VvBZR7 Protein

To determine the subcellular localization of VvBZR7, the recombinant plasmid pCAMBIA1300-35S-EGFP-VvBZR7 was transiently expressed in tobacco epidermal cells via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. As shown in Figure 7, the GFP signal of the control (empty vector) was distributed throughout the cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus. In contrast, the fluorescence of VvBZR7-EGFP was exclusively localized to the nucleus. These results confirm that VvBZR7 is a nuclear protein, consistent with its predicted function as a transcription factor.

Figure 7.

Subcellular localization of VvBZR7. GFP was used as a control. Three independent experiments were performed. Scale bars = 20 μm.

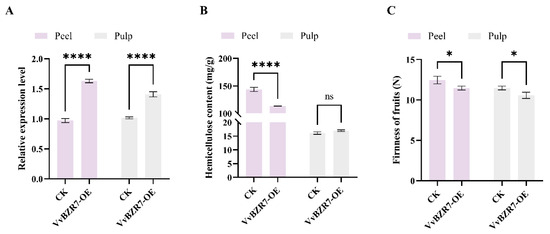

3.9. Transient Overexpression of VvBZR7 in Grapes

As a perennial fruit crop, grape lacks a well-established transgenic system due to challenges in genetic transformation and plant regeneration. Even when transformation is achieved, the process requires a relatively long cycle. To study the function of VvBZR7 in grape berries, transient overexpression was conducted in ‘Yinhong’ grape fruits during the fruit expansion stage. Expression levels of VvBZR7 in VvBZR7-OE fruit were 1.6-fold higher than those in the control, confirming successful overexpression (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Effects of transient VvBZR7 expression in grape berries. (A) Relative expression levels of VvBZR7. (B) Hemicellulose content in peel and pulp tissues. (C) Fruit firmness of grape berries. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent biological replicates. “ns”, “*” and “****” indicate differences at the levels of p > 0.05, p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively.

To investigate the role of VvBZR7 overexpression in fruit softening, hemicellulose content and fruit firmness were assessed. At 3 days post-infection, hemicellulose levels in the peel were significantly reduced compared to the control, whereas no statistically significant difference was observed in the pulp (Figure 8B). Concurrently, VvBZR7 overexpression led to a significant decrease in fruit firmness (Figure 8C). These results demonstrate that VvBZR7 promotes hemicellulose degradation, reduces fruit firmness, and is thereby implicated in the softening process of grape berries.

4. Discussion

The BZR gene family, which functions as key transcription factors in the BR signaling pathway, is involved in diverse physiological and metabolic processes in plants [30]. Members of this family regulate growth, development, and stress responses, and they play an essential role in BR signal perception and transduction. Elucidating the evolutionary history and functional roles of BZR genes is critical for deciphering the BR signaling network [31]. This gene family has been characterized in several species: six members in A. thaliana [32], nine in tomato [26], eight in potato [31], twelve in kale [33], twenty in wheat [34], and twenty-one in Brassica napus [35]. The considerable variation in BZR gene copy numbers across species likely results from the combined effects of natural selection, genetic variation, and lineage-specific gene duplications or deletions during evolution. Nevertheless, studies on the BZR gene family in grapevine remain limited. Identification of its members represents a fundamental initial step toward uncovering their biological functions.

In this study, eight VvBZR genes were identified in grapevine and designated from VvBZR1 to VvBZR8 according to their chromosomal positions (Table 1). The number of VvBZR genes is similar to that reported in species such as A. thaliana and tomato, suggesting high evolutionary conservation of this gene family in plants. Phylogenetic analysis of BZR protein sequences from grapevine and four other plant species showed that grape BZR proteins are more closely related to those from A. thaliana and tomato than to those from monocots such as maize and rice, which reflects the closer evolutionary relationships among dicot species and underscores the influence of phylogeny on plant diversification. The grape BZR family was divided into four subfamilies in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). Members within each subfamily generally share similar motif compositions, though exceptions were observed. For example, all VvBZR proteins contain Motif1 and Motif2 (Figure 2), with VvBZR6 possessing only these two motifs. Motif6 was exclusively present in subfamilies I and IV, which may reflect adaptive changes under different functional or environmental constraints. In subfamily III, Motif4 and Motifs7~10 were unique to VvBZR1 and VvBZR5, suggesting that these motifs may provide selective advantages through functional specialization or neofunctionalization. These results indicate that VvBZR proteins have evolved distinct functional specificities.

The conserved exon-intron organization observed throughout the phylogenetic tree reflects shared evolutionary trajectories among related members. The strong correlation between structural complexity and phylogenetic clustering further suggests that motif composition and gene architecture collectively serve as conserved evolutionary indicators [36]. Gene structure analysis revealed that the eight VvBZR genes maintain relatively stable exon numbers, with most containing two exons and a minority possessing 9–10 exons. Subfamilies I, II, and IV display structurally conserved gene architectures, whereas subfamily III shows considerable variation. This suggests that the expansion of the BZR gene family occurred mainly within subfamily III—a finding consistent with the phylogenetic tree, in which structurally similar VvBZR genes cluster together. Gene duplication events, including both segmental and tandem duplications, are major drivers of gene family evolution and expansion. Collinearity analysis identified two duplicated gene pairs in the VvBZR family: VvBZR2/VvBZR7 and VvBZR4/VvBZR8. These segmentally duplicated pairs share identical exon-intron structures and cluster on the same phylogenetic branches, indicating a common evolutionary origin and a role in family expansion. Furthermore, synteny analysis with A. thaliana and tomato identified 6 and 9 syntenic gene pairs, respectively, underscoring a closer evolutionary relationship among these dicot species (Figure 3). These results highlight strong genomic conservation across dicotyledonous plants and support the hypothesis of shared ancestral origins. Such conservation also allows functional predictions to be made based on gene homology.

Cis-acting regulatory elements are non-coding DNA sequences located in gene promoter regions, and their distribution patterns can reflect variations in gene regulation and function. Analysis of the VvBZR promoters identified multiple cis-elements associated with light responsiveness, hormone response, growth and development, as well as biotic and abiotic stress (Figure 4). Among these, light- and hormone-responsive elements were particularly abundant, suggesting that VvBZR genes may integrate multiple signaling pathways to precisely modulate plant physiological processes. This regulatory capacity profoundly influences plant growth, development, and stress adaptation. For instance, in the A. thaliana bzr1-1D mutant, BZR1 binds to an ABA-responsive element and inhibits the transcriptional activation of ABI5, thereby reducing ABA sensitivity [37,38]. Zhang et al. [39] reported that jasmonic acid (JA) attenuates brassinosteroid signaling by suppressing the expression of the BR biosynthetic gene DWF4 and inhibiting MYC2-mediated transcriptional activation of BZR1 during apical hook development in A. thaliana. Similarly, in pear, PpyBZR2 promotes bud dormancy release by repressing PpyDAM3 expression and participates in the gibberellin biosynthesis pathway regulated by PpyMYC2 [40]. In rice, BZR1 directly binds to the E-box in the RAmy3D promoter and positively regulates its expression, enhancing α-amylase activity and soluble sugar content to facilitate seed germination [41]. These multifaceted regulatory mechanisms illustrate that BZR family genes function as key players in cross-hormonal signaling networks across plant species.

Gene expression levels vary across plant tissues, enabling adaptation to diverse biological processes [42]. Previous research has established that transcription factors are central to the regulation of gene expression under varying environmental conditions [43]. As a key integrator of the BR signaling pathway, the BZR gene fulfills distinct roles throughout plant growth and development [44,45]. Tissue-specific expression profiling revealed that each VvBZR gene is expressed in multiple tissues, albeit with significant variation in transcript abundance (Figure 5). Among them, VvBZR3 showed the highest expression in callus, whereas VvBZR7 was most highly expressed in tendrils. In contrast, VvBZR2, VvBZR4, and VvBZR8 displayed relatively low expression levels across all examined tissues. These results establish a foundation for further investigation into their potential biological functions. Analysis of plant hormone response patterns further confirmed that VvBZR family genes are differentially expressed under various hormonal treatments, implicating their involvement in multiple hormone signaling pathways (Figure 6). Notably, VvBZR7 was identified as a potential key regulatory factor in the BR signaling pathway and was selected for subsequent functional analysis.

VvBZR7 is phylogenetically classified within the same subfamily as AtBZR1 and AtBES1, which are key transcription factors in the Arabidopsis thaliana BR signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown that heterologous expression of the dominant-active form BZR1-1D (AtBES1) in tomato enhances carotenoid accumulation, promotes fruit ripening [46], and improves fruit quality by modulating BR signaling, ethylene pathways, transcription factors, and metabolic processes [47]. Based on this functional analogy, VvBZR7 was selected for further analysis. An overexpression vector containing a GFP tag was constructed for subcellular localization, which confirmed that VvBZR7 localizes to the nucleus (Figure 7). Transient overexpression of VvBZR7 in grape berries elevated its transcript levels, concomitant with reductions in both hemicellulose content and fruit firmness, implicating its function in regulating cell wall modification during fruit development (Figure 8). Hemicellulose is one of the major components of the cell wall and interacts with cellulose microfibrils through hydrogen bonding to maintain tissue strength and provide mechanical support [48,49,50]. Thus, the decrease in hemicellulose content observed in VvBZR7-overexpressing berries is likely to weaken cell wall strength, promote cell loosening, and consequently reduce fruit firmness. The coordinated changes in hemicellulose content and fruit firmness therefore support a potential role for VvBZR7 in promoting cell wall disassembly and accelerating fruit softening. Nevertheless, transcriptional regulation in vivo involves considerable complexity, and further studies are required to identify and characterize the downstream target genes of VvBZR7.

5. Conclusions

This study identified eight members of the BZR gene family in the grape genome, offering insights into their potential functions and expression profiles. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the grape VvBZR gene family is classified into four subfamilies distributed across seven different chromosomes. Each gene contains the essential BES_N domain, which is critical for BR signal transduction. Analysis of cis-regulatory elements suggests that BZR transcription factors play key regulatory roles in grape growth and development, as well as in hormonal responses to abiotic stress. Tissue-specific expression profiling demonstrated that VvBZR genes are expressed in multiple tissues with distinct spatial specificity. Furthermore, VvBZR7 was shown to localize to the nucleus and participate in cell wall component degradation, leading to reduced fruit firmness and implicating its direct role in mediating fruit softening. These results establish a foundation for further investigation into gene functions and regulatory networks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122749/s1, Supplementary Table S1. Protein sequences of Grape, A. thaliana, Tomato, Rice and Maize, together with their corresponding gene accession numbers. Supplementary Table S2. Primers used for gene expression and vector construction. Supplementary Table S3. The secondary structure of VvBZR protein sequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and Z.Y.; methodology, Q.Z., L.H. and H.H.; data curation, L.H., Y.Z. and Y.X.; resources, C.F. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z. and Z.C.; project administration, Y.W. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Public Welfare Research Program Key Project of Ningbo (2024S016), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2021C02053), 2024 Zhejiang Provincial College Students’ Innovation and Technology Activity Program (New Talent Program) (2024R420A013) and Zhejiang Province’s First Class Discipline of Bioengineering (CX2024047).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qiao, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; He, C.; Zong, D. Genome-Wide Identification, Expression Analysis, and Subcellular Localization of DET2 Gene Family in Populus yunnanensis. Genes 2024, 15, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Quan, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Brassinosteroid Promotes Grape Berry Quality-Focus on Physicochemical Qualities and Their Coordination with Enzymatic and Molecular Processes: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lv, J.; Yu, J. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of BZR gene family and associated responses to abiotic stresses in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Zhao, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, C.; Fan, M.; Guo, H.; Bai, M.-Y. Interaction between BZR1 and EIN3 mediates signalling crosstalk between brassinosteroids and ethylene. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 2308–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, P.; Zhang, T.; Dong, H.; Jing, Y.; Yang, Z.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, M.; Liu, J.; et al. Plant-specific BLISTER interacts with kinase BIN2 and BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT1 during skotomorphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 1580–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Luo, B.; Hu, M.; Fu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Brassinosteroid Signaling Downstream Suppressor BIN2 Interacts with SLFRIGIDA-LIKE to Induce Early Flowering in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Jiang, W.-B.; Hu, Y.-W.; Wu, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Liang, W.-Q.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Lin, W.-H. BR Signal Influences Arabidopsis Ovule and Seed Number through Regulating Related Genes Expression by BZR1. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y. Genome-Wide Identification Reveals That BZR1 Family Transcription Factors Involved in Hormones and Abiotic Stresses Response of Lotus (Nelumbo). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Shawky, B.T. Enhancement of the Expression of ZmBZR1 and ZmBES1 Regulatory Genes and Antioxidant Defense Genes Triggers Water Stress Mitigation in Maize (Zea mays L.) Plants Treated with 24-Epibrassinolide in Combination with Spermine. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Weng, W.; Yao, X.; Wu, W.; Bai, Q.; Xiong, R.; Ma, C.; Cheng, J.; Ruan, J. Genome-Wide Identification, Structural Characterization, and Gene Expression Analysis of BES1 Transcription Factor Family in Tartary Buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Guan, S.; Sun, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tang, W.; Shang, J.-X.; Sun, Y.; Burlingame, A.L.; Wang, Z.-Y. Brassinosteroid signal transduction from cell-surface receptor kinases to nuclear transcription factors. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, S.D. Brassinosteroid Signal Transduction: From Receptor Kinase Activation to Transcriptional Networks Regulating Plant Development. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Zheng, H.; Tang, X.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Bai, M.-Y.; et al. The BZR1-EDS1 module regulates plant growth-defense coordination. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 2072–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mu, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.; Lyu, J.; Liu, Z.; Luo, S.; Yu, J. The BES1/BZR1 family transcription factor as critical regulator of plant stress resilience. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Han, C.; Bai, M.; Fan, M. EBF1 Negatively Regulates Brassinosteroid-Induced Apical Hook Development and Cell Elongation through Promoting BZR1 Degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, T.-K.; Tian, Y.; Yu, K.; Lee, B.-H.; Bai, M.-Y.; Cho, S.-J.; Kim, T.-W. Comparative analysis of BZR1/BES1 family transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2024, 117, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, T.-K.; Kim, Y.-P.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, T.-W. Transcription factors BZR1 and PAP1 cooperate to promote anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis shoots. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3654–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Qu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, J.; Chu, J.; Xu, M.; Su, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, A. The mechanism for brassinosteroids suppressing climacteric fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1875–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Ding, L.; Feng, W.; Cao, Y.; Lu, F.; Yang, Q.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Shabek, N.; Fu, F.; et al. Maize transcription factor ZmBES1/BZR1-5 positively regulates kernel size. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1714–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Ai, G.; Xie, Q.; Wang, W.; Song, J.; Wang, J.; Tao, J.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Z.; Lu, Y.; et al. Regulation of tomato fruit elongation by transcription factor BZR1.7 through promotion of SUN gene expression. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac121. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Liang, H.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X.; Jiang, G. The H3R2me2a demethylase JMJ10 regulates tomato fruit size through its interaction with the transcription factor BZR1.3. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, H.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Yin, X.; Zhu, Q.; Rao, J. Transcription factors DkBZR1/2 regulate cell wall degradation genes and ethylene biosynthesis genes during persimmon fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6437–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Shao, Z.; Wang, M.; Gan, X.; Yang, X.; Lin, S. EjBZR1 represses fruit enlargement by binding to the EjCYP90 promoter in loquat. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Qin, Y.; Si, H.; Ji, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y. Pre-harvest treatment with gibberellin (GA3) and nitric oxide donor (SNP) enhances post-harvest firmness of grape berries. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2025, 10, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, U.; Shalmani, A.; Ilyas, M.; Raza, A.; Ahmad, S.; Shah, A.Z.; Khan, F.U.; Azizud, D.; Bibi, A.; Rehman, S.U.; et al. BZR proteins: Identification, evolutionary and expression analysis under various exogenous growth regulators in plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 12039–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Wei, X. Genome-wide identification, structural analysis, and expression profiles of the BZR gene family in tomato. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, A.; Trevisan, S.; Quaggiotti, S.; Varotto, S. Identification and characterization of the BZR transcription factor family and its expression in response to abiotic stresses in Zea mays L. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Xu, T.; Cai, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, T.; Gong, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Identifying Candidate Genes for Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Fruit Firmness through Genome-Wide Association Studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 8413–8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Hu, H.; Fang, C.; Wang, L.; Hu, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y. Regulation of Cell Metabolism and Changes in Berry Shape of Shine Muscat Grapevines Under the Influence of Different Treatments with the Plant Growth Regulators Gibberellin A3 and N-(2-Chloro-4-Pyridyl)-N′-Phenylurea. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Cheng, J.; Yu, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the BZR Transcription Factor Gene Family in Leymus chinensis. Genes 2025, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Song, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Evolutionary analysis and functional characterization of BZR1 gene family in celery revealed their conserved roles in brassinosteroid signaling. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowiec, J.; Mason, G.A.; Schultz, K.; Queitsch, C. Redundancy, Feedback, and Robustness in the Arabidopsis thaliana BZR/BEH Gene Family. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.A.; Hamza, M.; Gull, R.; Shafiq, M.; Wahid, A.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmadi, T.; Rahimi, M. Genome-wide analysis of the BoBZR1 family genes and transcriptome analysis in Brassica oleracea. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesawat, M.S.; Kherawat, B.S.; Singh, A.; Dey, P.; Kabi, M.; Debnath, D.; Saha, D.; Khandual, A.; Rout, S.; Manorama Ali, A.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the Brassinazole-resistant (BZR) Gene Family and Its Expression in the Various Developmental Stage and Stress Conditions in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, R.; Geng, R.; Li, L.; Shan, Y.; Zhu, K.-M.; Wang, J.; Tan, X.-L. Genome-Wide Prediction, Functional Divergence, and Characterization of Stress-Responsive BZR Transcription Factors in B. napus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 790655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; Du, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of the Glycosyl Hydrolase Family 1 Genes in Brassica napus L. and Functional Characterization of BnBGLU77. Plants 2025, 14, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Park, C.-H.; Son, S.-H.; Youn, J.-H.; Kim, S.-K. Endogenous level of abscisic acid down-regulated by brassinosteroids signaling via BZR1 to control the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1926130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bai, Y.; Shang, J.; Xin, R.; Tang, W. The antagonistic regulation of abscisic acid-inhibited root growth by brassinosteroids is partially mediated via direct suppression of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 expression by BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT 1. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Shi, H.; Lv, M.; He, L.; Bai, W.; Cheng, S.; Chu, J.; He, K.; et al. Jasmonates regulate apical hook development by repressing brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signaling. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 1561–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, B.; Wang, P.; Alabd, A.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; Ni, J.; Bai, S.; et al. Transcription factors BZR2/MYC2 modulate brassinosteroid and jasmonic acid crosstalk during pear dormancy. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1794–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, Q.; Huang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Fan, X.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Q.-Q.; et al. Brassinosteroids regulate rice seed germination through the BZR1-RAmy3D transcriptional module. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Shin, H.-Y.; Kang, H.K.; Shang, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Jeong, D.-H.; Nam, K.H. Reciprocal inhibition of expression between RAV1 and BES1 modulates plant growth and development in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1226–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Shu, X.; Ning, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhuang, W. Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms of bHLH Transcription Factors during the Responses to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Woody Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, C. Comprehensive analysis of the BES1 gene family and its expression under abiotic stress and hormone treatment in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wei, Y.; Shen, B.; Liu, L.; Mao, J. Interaction of the Transcription Factors BES1/BZR1 in Plant Growth and Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Jia, C.; Zhang, M.; Chen, D.; Chen, S.; Guo, R.; Guo, D.; Wang, Q. Ectopic expression of a BZR1-1D transcription factor in brassinosteroid signalling enhances carotenoid accumulation and fruit quality attributes in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xia, X.; Yang, J.; Xin, J.; Chen, S.; Jia, C. Overexpression of AtBES1D in tomato enhances BR response and accelerates fruit ripening. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 312, 154563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, W.; Liu, L.; Hu, Q.; Wei, W.; Liu, J. Dissecting the Genetic Mechanisms of Hemicellulose Content in Rapeseed Stalk. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, Y.; Han, Z.; Song, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Functional analysis of the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase gene MdXTH2 in apple fruit firmness formation. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 3418–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayari, A.; Thielemans, W.; Hirn, U.; Van Vuure, A.W.; Seveno, D. Cellulose-hemicellulose interactions—A nanoscale view. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).