Synthesis, Antibacterial Properties, and Physiological Responses of Nano-Selenium in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Nano-Se

2.2. Antibacterial Activity of Nano-Se

2.3. Plant Material and Experimental Designs

2.4. Plant Growth, Biomass, and Element Determination

2.5. Photosynthetic Pigment Content and Photosynthetic Parameters

2.6. Lipid Peroxidation, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.7. Carbohydrate Measurement

2.8. Total Flavonoids, Phenols, and Proline Measurement

2.9. Amino Acid and Soluble Protein Evaluation

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

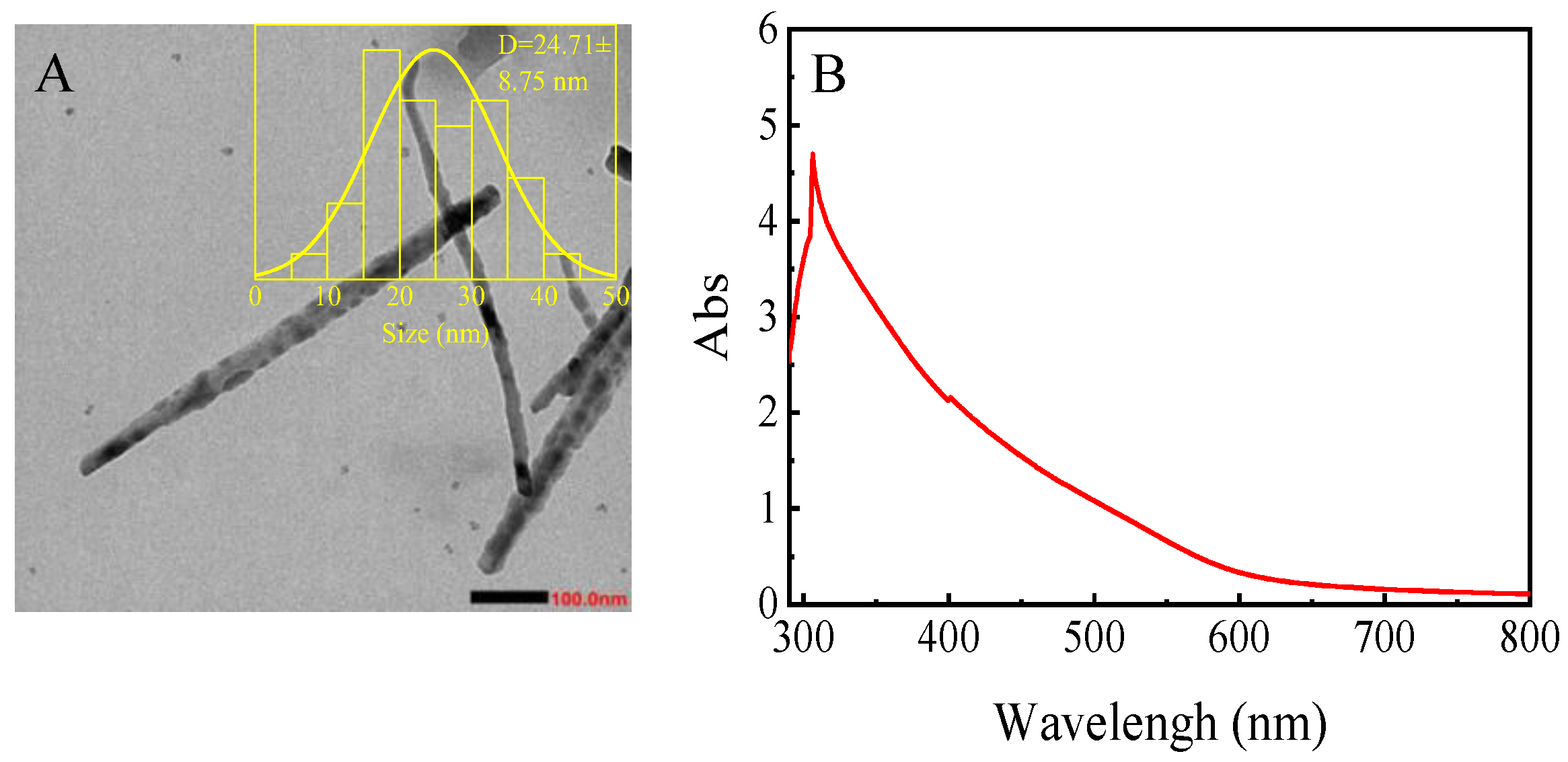

3.1. Characterization of Nano-Se

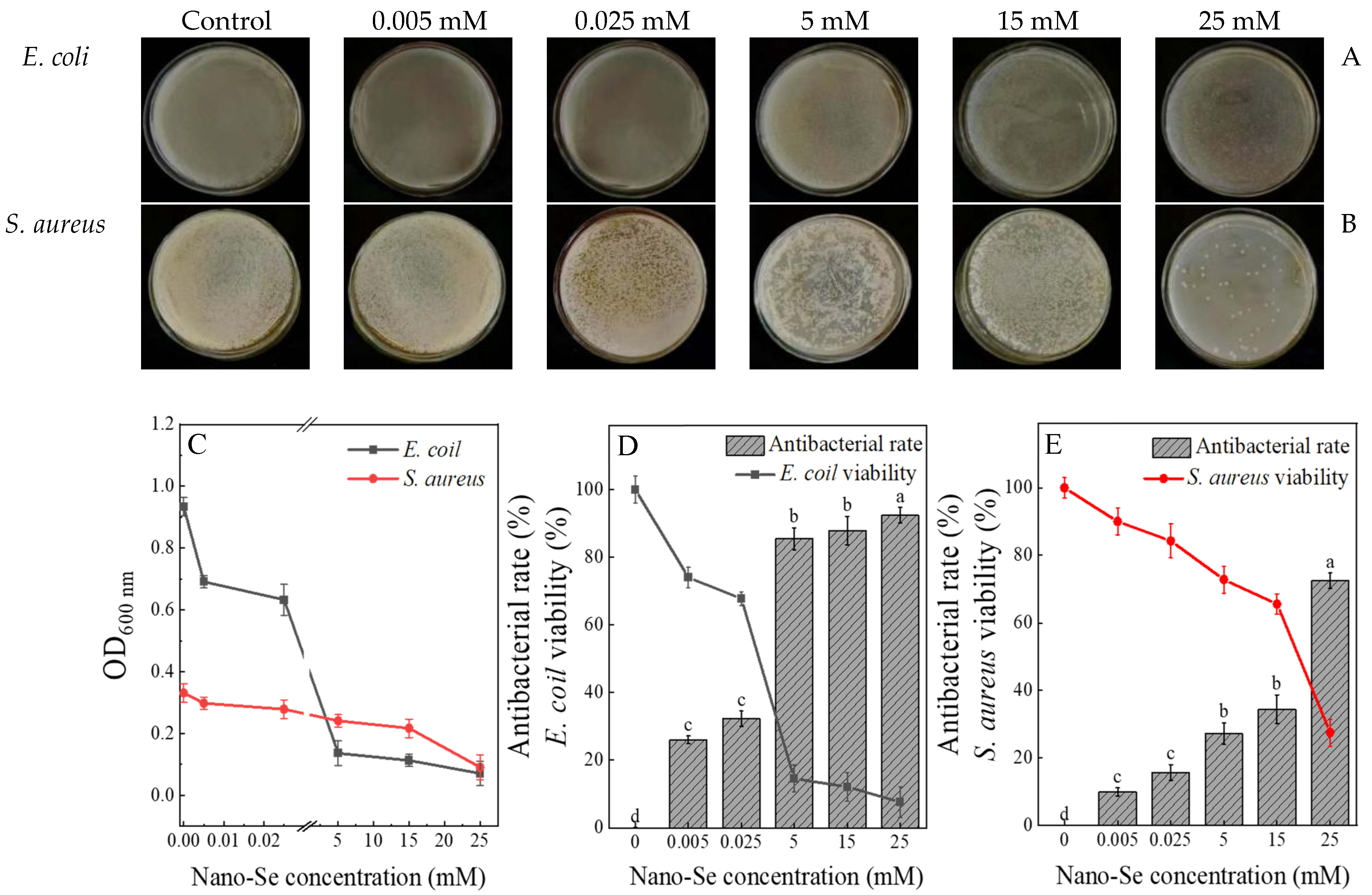

3.2. Analysis of the Antibacterial Activity of Nano-Se

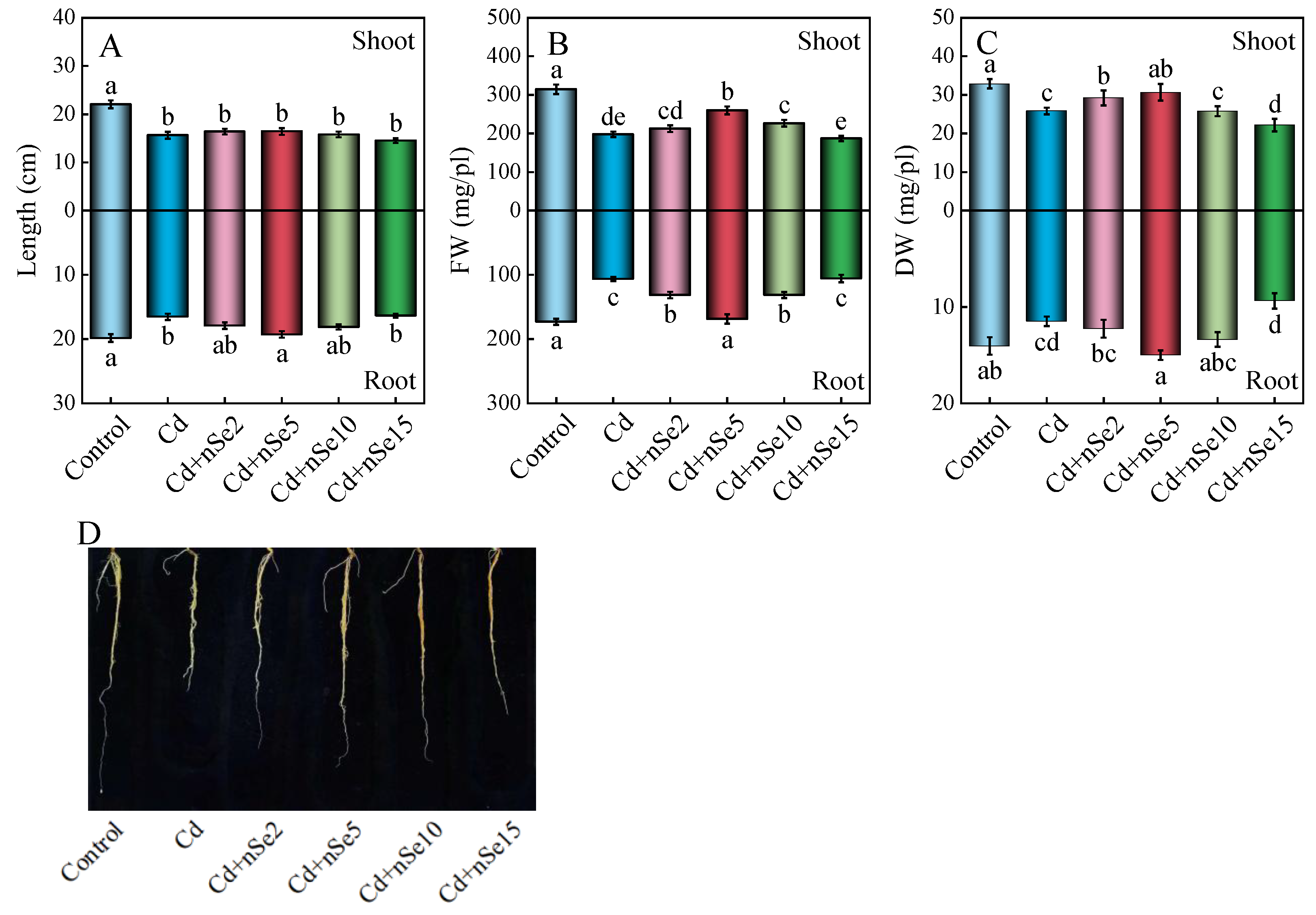

3.3. Plant Growth Parameters

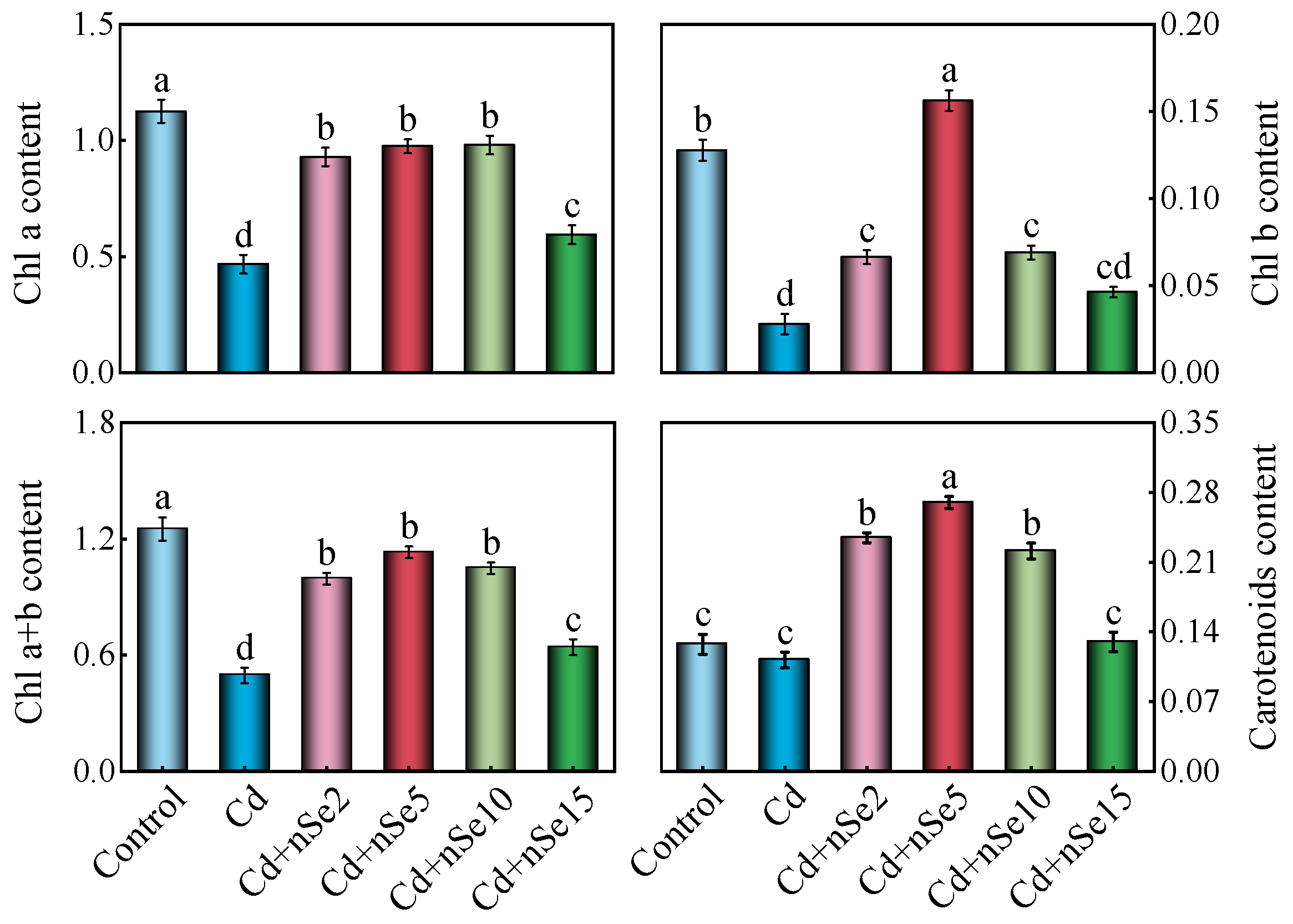

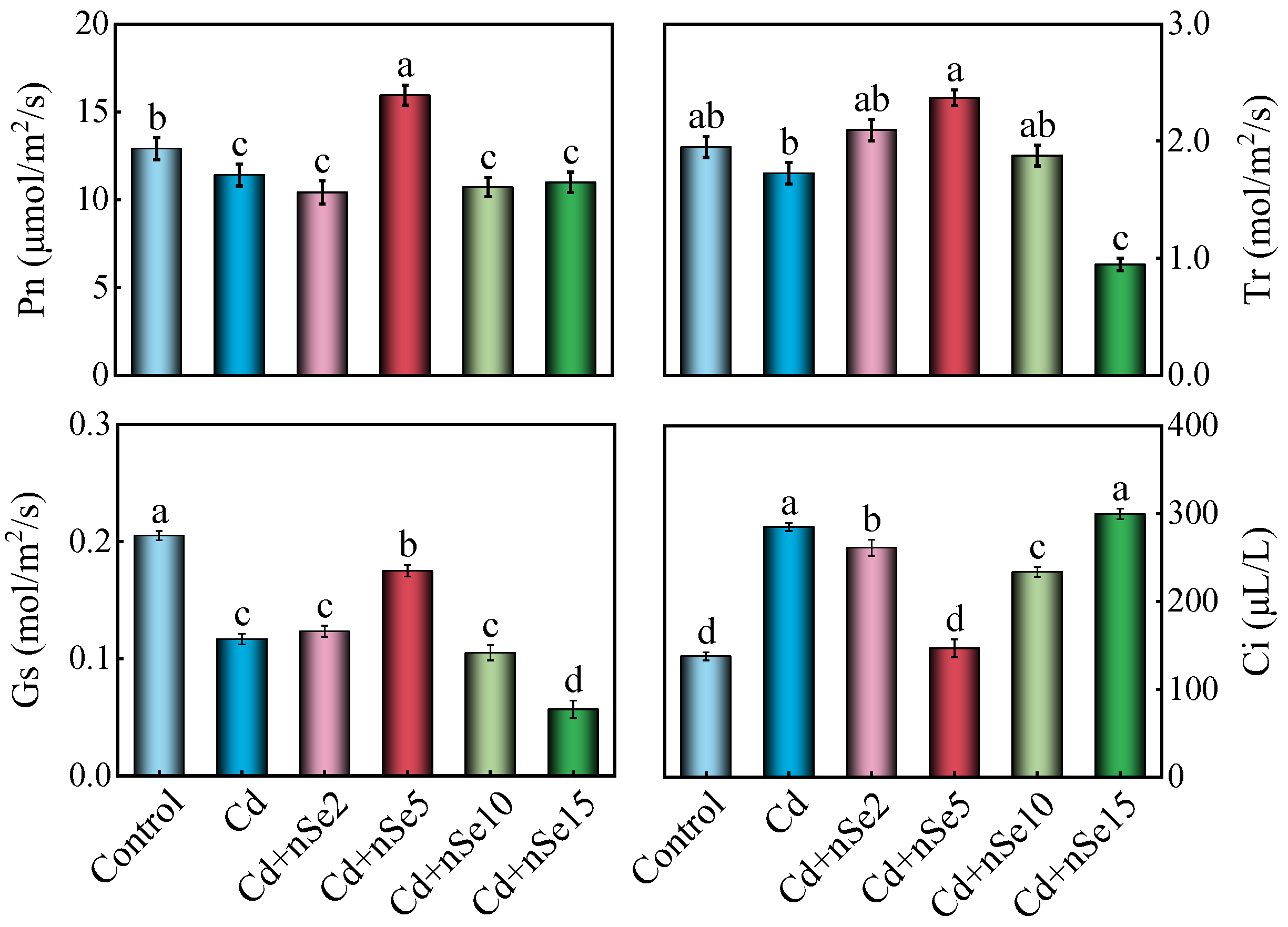

3.4. Photosynthetic Pigment Contents and Parameters

3.5. Cd and Nutrient Element Concentration

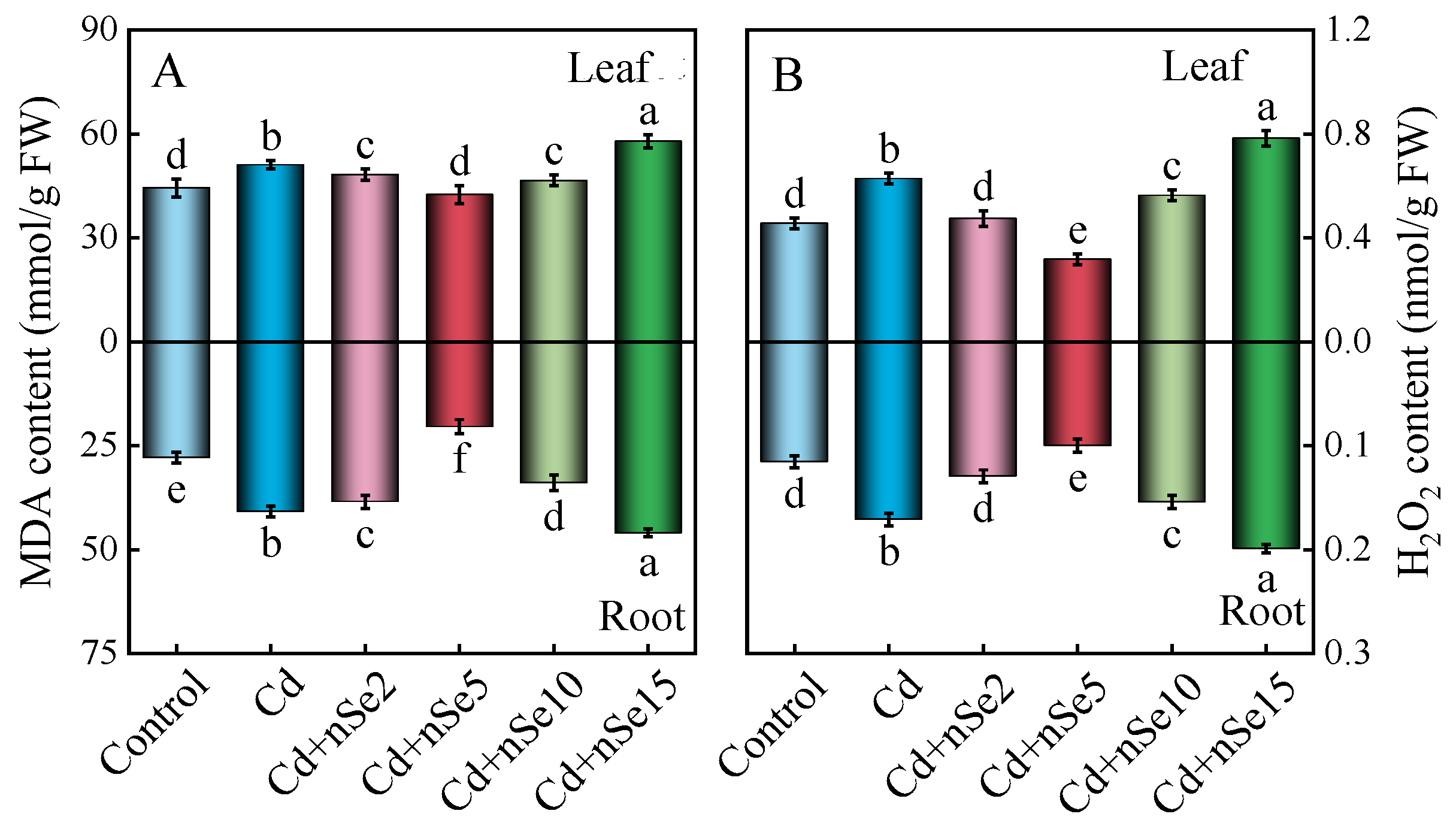

3.6. Accumulation of Lipid Peroxidation, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.7. Carbohydrate Content

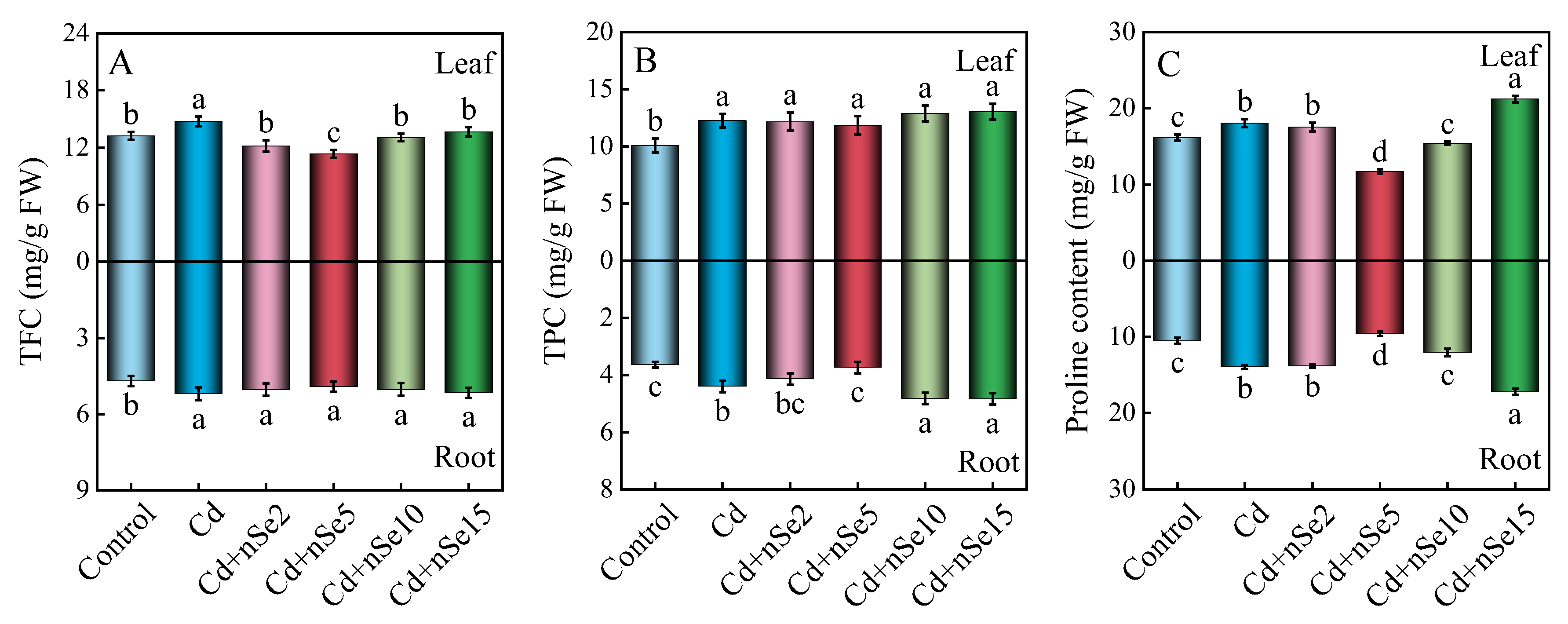

3.8. Total Flavonoid, Total Phenol, and Proline Content

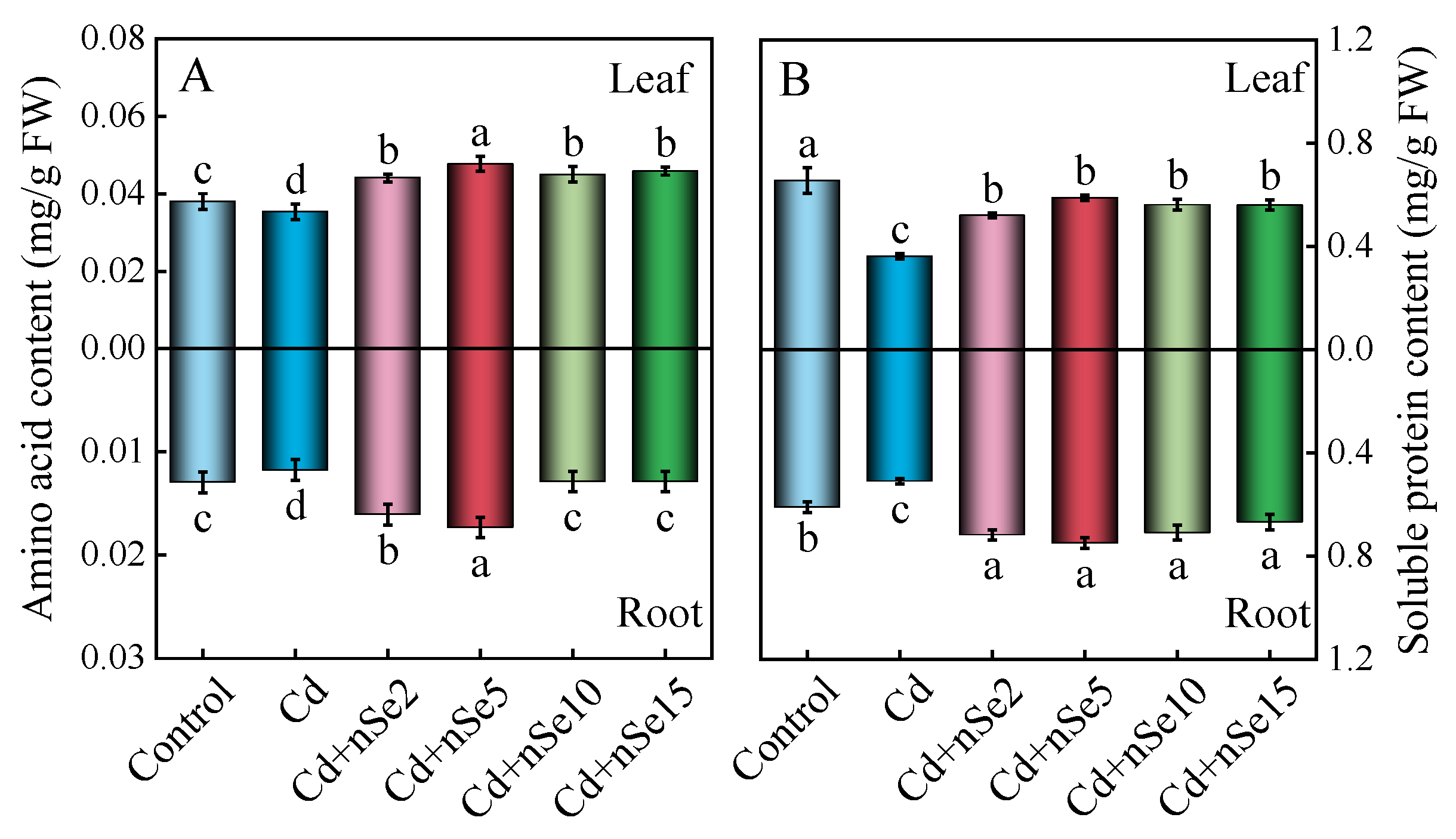

3.9. Analysis of Amino Acid and Soluble Protein Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Nano-Se

4.2. Exogenous Nano-Se Mitigates Cd-Induced Inhibition in Plant Growth, Reduces Cd Accumulation, and Counteracts Nutrient Element Changes

4.3. Exogenous Nano-Se Improves Cd-Induced Inhibition in Pigments and Photosynthesis

4.4. Exogenous Nano-Se Offsets Cd-Induced Alterations in the Antioxidant System

4.5. Exogenous Nano-Se Counteracts Cd-Induced Changes in Carbohydrate Content, Total Flavonoids, Total Phenols, and Proline Content

4.6. Exogenous Nano-Se Abates Cd-Induced Changes in Amino Acid and Soluble Protein

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Se | Selenium |

| μM | μmol/L |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Na2SeO3 | Sodium selenite |

| PCA | Plate count agar |

| DW | Dry weights |

| Pn | Photosynthetic rate |

| Tr | Transpiration rate |

| Gs | Stomatal conductance |

| Ci | Intercellular carbon dioxide concentration |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

References

- Kang, Y.; Qin, H.; Wang, G.; Lei, B.; Yang, X.; Zhong, M. Selenium nanoparticles mitigate cadmium stress in tomato through enhanced accumulation and transport of sulfate/selenite and polyamines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.D.; Zhao, D.; Ren, F.T.; Huang, L. Spatiotemporal variation of soil heavy metals in China: The pollution status and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 161768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.J.; Lian, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.J.; Yu, J.; Gao, Y.F.; Zhang, Q.M.; Sun, H.Y. Nano silicon dioxide reduces cadmium uptake, regulates nutritional homeostasis and antioxidative enzyme system in barley seedlings (Hordeum vulgare L.) under cadmium stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 67552–67564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.Y.; Zhang, B.; Rong, Z.J.; He, S.J.; Gao, Y.F.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q.M. Effects of nano-silicon dioxide on minerals, antioxidant enzymes, and growth in bitter gourd seedlings under cadmium stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2023, 45, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Mao, W.H.; Zhang, G.P.; Wu, F.B.; Cai, Y. Root excretion and plant tolerance to cadmium toxicity—A review. Plant Soil Environ. 2007, 53, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Wu, Y.L.; Zhang, J.B.; An, Q.S.; Zhou, C.R.; Li, D.; Pan, C.P. Nano-selenium enhances the antioxidant capacity, organic acids and cucurbitacin B in melon (Cucumis melo L.) plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 241, 113777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Dai, H.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, G.H. Physiological and proteomic analysis of selenium-mediated tolerance to Cd stress in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 133, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Zhou, B.; Hong, B.; Wang, X.; Chang, T.; Guan, C.; Guan, M. Application of selenium can alleviate the stress of cadmium on rapeseed at different growth stages in soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Meng, S.; Huang, J.; Zhou, W.; Song, X.; Hao, P.; Tang, P.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the mechanism of exogenous selenium in alleviating cadmium stress in purple flowering stalks (Brassica campestris var. purpuraria). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, F.; Guha, T.; Kundu, R. Exogenous selenium supplements reduce cadmium accumulation and restore micronutrient content in rice grains. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 10, 2275–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Thounaojam, T.C.; Chowdhury, D.; Upadhyaya, H. The role of selenium and nano selenium on physiological responses in plant: A review. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiros, O.; Nagy, V.; Párducz, Á.; Nagy, G.; Ünnep, R.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J.; Lisztes-Szabó, Z.; Fári, M.; Csajbók, J.; et al. Effects of selenate and red Se-nanoparticles on the photosynthetic apparatus of Nicotiana tabacum. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 139, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, F.; Bag-Nazari, M.; Azizi, A. Exogenous application of selenium and nano-selenium alleviates salt stress and improves secondary metabolites in lemon verbena under salinity stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Siddika, A.; Bardhan, K.; Hosen, M.S.; Prasad, P.V.V. Selenium and its nanoparticles modulate the metabolism of reactive oxygen species and morpho-physiology of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to combat oxidative stress under water deficit conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, R.; Ahmed, S.; Shah, A.A.; Yasin, N.A. Selenium nanoparticles reduced cadmium uptake, regulated nutritional homeostasis and antioxidative system in Coriandrum sativum grown in cadmium toxic conditions. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.R.; Cheng, T.T.; Liu, H.T.; Zhou, F.Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.Y.; Shi, W.J.; Cao, T. Nano-selenium controlled cadmium accumulation and improved photosynthesis in indica rice cultivated in lead and cadmium combined paddy soils. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 103, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, H.B.; Dang, F.; Cheng, B.X.; Cheng, C.; Ge, C.H.; Zhou, D.M. Common metabolism and transcription responses of low-cadmium-accumulative wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars sprayed with nano-selenium. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Li, X.Y.; Lu, Z.X.; Yi, S.Y.; Shang, B.J.; Li, L.; Sun, H.Y. Effect of different levels of nano-selenium on growth performance, physiological responses and antioxidative capacity of barley seedlings. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymanzadeh, R.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Habibi, G.; Ardebili, Z.O. Selenium nanoparticle protected strawberry against salt stress through modifications in salicylic acid, ion homeostasis, antioxidant machinery, and photosynthesis performance. Acta Biol. Cracov. Bot. 2020, 62, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.R.; Jing, R.; Qin, X.; Liang, X.F.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.M.; Sun, Y.B.; Huang, Q.Q. The role and transcriptomic mechanism of cell wall in the mutual antagonized effects between selenium nanoparticles and cadmium in wheat. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 472, 134549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; An, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Li, J.Q.; Pan, C. Nanoselenium integrates soil-pepper plant homeostasis by recruiting rhizosphere-beneficial microbiomes and allocating signaling molecule levels under Cd stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Li, X.Y.; Li, L.; Shang, B.J.; Yi, S.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Sun, H.Y. Preparation, characterization, and application of nano-selenium in alleviating cadmium toxicity in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 115, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Riaz, A.; Khan, A.; Ali, S.; Zhang, G. Manganese enhances cadmium tolerance in barley through mediating chloroplast integrity, antioxidant system, and HvNRAMP expression. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.R.; Feng, T.; Wang, B.; He, R.H.; Xu, Y.L.; Gao, P.P.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, L.; Fu, J.Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Enhancing organic selenium content and antioxidant activities of soy sauce using nano-selenium during soybean soaking. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 970206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyen, N.N.K.; Huy, V.K.; Duy, N.H.; An, H.; Nam, N.T.H.; Dat, N.M.; Huong, Q.T.T.; Trang, N.L.; Anh, N.D.; Thy, L.T.M.; et al. Green synthesis of selenium nanorods using Muntigia calabura leaf extract: Effect of pH on characterization and bioactivities. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments and photosynthetic biomembranes. Method. Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Huang, L.F.; Nogués, S. The relationship between CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic electron transport and water-water cycle in chill-exposed cucumber leaves under low light and subsequent recovery. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, G.; Dominy, P. Four barley genotypes respond differently to cadmium: Lipid peroxidation and activities of antioxidant capacity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2003, 50, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation and SOD, POD and CAT activities in biological system. In Research Methodology of Crop Physiology; Zhang, X.Z., Ed.; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1992; pp. 208–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.X.; Liu, L.; Liu, C.; He, S.Y.; Huang, J.; Li, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.J.; Gu, N. Physiological investigation of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles towards Chinese mung bean. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2011, 7, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Tang, M.C.; Wu, J.M. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpinc, P.; Čeh, B.; Ulrih, N.P.; Abramovič, H. Studies of the correlation between antioxidant properties and the total phenolic content of different oil cake extracts. Indian Crop Prod. 2012, 39, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I. Rapid determination of free proline for waterstress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Qin, H.S.; Jiang, D.H.; Lu, J.J.; Zhu, Z.J.; Huang, X.J. Bio-nano selenium fertilizer improves the yield, quality, and organic selenium content in rice. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 132, 106348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Chen, T.F.; Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Zheng, W.J. Facile and controllable one-step fabrication of selenium nanoparticles assisted by L-cysteine. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.Y.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Yan, Z.X.; Wei, H.Y.; Xu, D.J.; Cheng, X. Preparation of polysaccharide-conjugated selenium nanoparticles from spent mushroom substrates and their growth-promoting effect on rice seedlings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253 Pt 2, 126789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.; Cerana, R. Recent applications of chitin and chitosan-based polymers in plants. Polymers 2019, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Chen, F.; Cheng, H.; Huang, G.L. Modification and application of polysaccharide from traditional Chinese medicine such as Dendrobium officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Tian, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, D. Nano-selenium stablilized by Konjac Glucommannan and its biological activity in vitro. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 161, 113289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, H.; Khatoon, N.; Raza, M.; Ghosh, P.C.; Sardar, M. Synthesis and characterization of nano selenium using plant biomolecules and their potential applications. Bio. Nano Sci. 2019, 9, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germ, M.; Kreft, I.; Osvald, J. Influence of UV-B exclusion and selenium treatment on photochemical efficiency of photosystem II, yield and respiratory potential in pumpkins (Cucurbita pepo L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2005, 43, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, K.; Prasad, D.; Prasad, A. Selenium as a novel regulator of porphyrin biosynthesis in germinating seedlings of mung bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Biochem. Int. 1990, 22, 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Xing, S.F.; Xu, M.; Yan, Z.; Song, C.; Wang, S.G. Selenium nanoparticles ameliorate Brassica napus L. cadmium toxicity by inhibiting the respiratory burst and scavenging reactive oxygen species. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheery, N.I.; Sunoj, V.S.J.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, J.J.; Muralidharan, G.; Cao, K.F. Foliar application of nanoparticles mitigates the chilling effect on photosynthesis and photoprotection in sugarcane. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafariyan, M.H.; Malakouti, M.J.; Dadpour, M.R.; Stroeve, P.; Mahmoudi, M. Effects of magnetite nanoparticles on soybean chlorophyll. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10645–10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Fatima, M.; Sardar, R.; Yasin, N.A. Application of nano selenium alleviates Cd-induced growth inhibition and enhances biochemical responses and the yield of Solanum melongena L. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 8099–8120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Imtiaz, M.; Rizwan, M.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, H.; Tu, S. Dynamics of selenium uptake, speciation, and antioxidant response in rice at different panicle initiation stages. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, D.Y.; Gu, W.R.; Zhang, L.G.; Li, C.F.; Chen, X.C.; Li, J.; Li, L.J.; Xie, T.L.; Wei, S. Role of chitosan in the regulation of the growth, antioxidant system and photosynthetic characteristics of maize seedlings under cadmium stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 66, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Y.; Qiu, L.S.; Guo, L.P.; Jing, S.S.; Chen, X.Y.; Cui, X.M.; Yang, Y. Salicylic acid alleviates aluminum-induced inhibition of biomass by enhancing photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in Panax notoginseng. Plant Soil. 2019, 445, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.; Kappel, S.; Stärk, H.J.; Riegger, U.; Borovec, J.; Mattusch, J.; Heinz, A.; Schmelzer, C.E.H.; Matoušková, Š.; Dickinson, B.; et al. Cadmium toxicity investigated at the physiological and biophysical levels under environmentally relevant conditions using the aquatic model plant Ceratophyllum demersum. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1244–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.Y.; Song, F.B.; Zhu, X.C.; Liu, S.Q.; Liu, F.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, X.N. Nano-ZnO alleviates drought stress via modulating the plant water use and carbohydrate metabolism in maize. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosropour, E.; Weisany, W.; Tahir, N.A.R.; Hakimi, L. Vermicompost and biochar can alleviate cadmium stress through minimizing its uptake and optimizing biochemical properties in Berberis integerrima bunge. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 17476–17486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.A.A.; Dardiry, M.H.O.; Samad, A.; Abdelrady, E. Exposure to lead (Pb) induced changes in the metabolite content, antioxidant activity and growth of Jatropha curcas (L.). Trop. Plant Biol. 2020, 13, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardari, M.; Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V. Comparative study for the effect of selenium and nano-selenium on wheat plants grown under drought stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 69, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.X.; Tang, Q.; Chen, C.J.; Li, Q.; Lin, H.Y.; Bai, S.L.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, K.B.; Zhu, M.Z. Combined analysis of transcriptome and metabolome provides insights into nano-selenium foliar applications to improve summer tea quality (Camellia sinensis). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 175, 114496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Raja, N.I.; Mashwani, Z.U.R.; Omar, A.A.; Mohamed, A.H.; Satti, S.H.; Zohra, E. Phytogenic selenium nanoparticles elicited the physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant defense system amelioration of huanglongbing-infected ‘Kinnow’ mandarin plants. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moormann, J.; Heinemann, B.; Hildebrandt, T.M. News about amino acid metabolism in plant-microbe interactions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.T.; Zhangm, T.J.; Fang, Y.; Pan, C.P.; Fu, H.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Wang, J.D. Nano-selenium enhances sugarcane resistance to Xanthomonas albilineans infection and improvement of juice quality. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 254, 114759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tissues | Treatment | Element Concentration (mg/kg DW) * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Cu | Zn | Mn | Ca | Mg | ||

| Leaf | Control | nd | 25.77 ± 3.5 b | 4.56 ± 0.2 c | 6.65 ± 0.6 a | 6378 ± 64.1 a | 436 ± 7.2 b |

| Cd | 16.37 ± 4.6 a | 35.26 ± 1.8 a | 3.54 ± 0.3 d | 2.53 ± 0.3 d | 3976 ± 25.4 c | 321 ± 9.3 c | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 15.27 ± 3.8 ab | 19.74 ± 2.4 c | 5.81 ± 0.4 b | 4.34 ± 0.5 b | 5525 ± 46.3 ab | 471 ± 3.2 b | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 13.19 ± 2.8 c | 17.01 ± 2.0 d | 6.93 ± 0.7 a | 6.96 ± 0.4 a | 6092 ± 60.2 a | 551 ± 5.1 a | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 14.70 ± 3.5 b | 22.01 ± 2.9 bc | 6.63 ± 0.8 a | 3.43 ± 0.2 c | 6039 ± 61.3 a | 541 ± 6.2 a | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 16.02 ± 4.0 a | 25.00 ± 3.2 b | 3.40 ± 0.5 d | 2.99 ± 0.6 d | 46.75 ± 38.0 b | 477 ± 4.1 b | |

| Root | Control | nd | 65.36 ± 3.6 b | 19.08 ± 4.7 a | 15.00 ± 5.7 a | 1531 ± 89.1 a | 2038 ± 64.1 a |

| Cd | 192.63 ± 4.8 a | 69.09 ± 3.8 a | 13.65 ± 3.6 c | 8.57 ± 2.8 c | 885 ± 42.4 c | 1167 ± 36.2 d | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 171.34 ± 4.7 b | 33.72 ± 2.3 d | 16.10 ± 4.0 b | 9.12 ± 3.5 bc | 1067 ± 51.2 b | 1318 ± 45.1 c | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 132.78 ± 3.6 c | 33.67 ± 2.4 d | 17.22 ± 4.3 b | 13.28 ± 5.4 b | 1214 ± 67.1 b | 1894 ± 59.0 b | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 182.73 ± 4.6 ab | 34.28 ± 2.9 d | 11.80 ± 3.4 d | 12.11 ± 3.8 b | 1113 ± 54.3 b | 1419 ± 51.4 c | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 190.23 ± 4.7 a | 39.65 ± 3.2 c | 11.50 ± 3.1 d | 7.77 ± 1.7 d | 712 ± 34.1 c | 1068 ± 26.3 d | |

| Tissues | Treatment | SOD (U/g) | POD (μmol/min/g FW *) | CAT (nmol/min/g FW) | APX (nmol/min/g FW) |

| Leaf | Control | 1170.2 ± 15.0 a | 20.9 ± 2.0 c | 1555.3 ± 10.3 e | 24.3 ± 2.3 c |

| Cd | 1142.3 ± 20.4 a | 45.2 ± 2.7 a | 1532.3 ± 3.4 e | 30.9 ± 4.0 b | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 1090.4 ± 38.5 a | 45.2 ± 7.2 a | 1850.3 ± 8.8 d | 34.0 ± 4.4 a | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 1147.5 ± 14.4 a | 40.5 ± 2.6 b | 2354.6 ± 3.4 a | 36.5 ± 1.6 a | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 1066.0 ± 7.6 a | 47.2 ± 5.5 a | 2061.0 ± 17.8 b | 35.1 ± 2.4 a | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 1091.7 ± 4.1 a | 48.0 ± 1.5 a | 1985.2 ± 13.0 bc | 35.2 ± 1.4 a | |

| Root | Control | 587.5 ± 14.0 d | 36.0 ± 2.4 c | 94.2 ± 5.7 e | 19.8 ± 3.2 a |

| Cd | 628.9 ± 12.4 c | 42.9 ± 2.1 a | 163.7 ± 9.5 d | 23.5 ± 1.5 e | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 641.9.1 ± 8.9 b | 42.3 ± 1.7 a | 186.6 ± 4.1 c | 30.9 ± 2.3 c | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 684.3 ± 19.8 a | 37.2 ± 3.7 c | 280.9 ± 14.0 a | 33.3 ± 1.5 b | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 628.4 ± 10.9 c | 40.1 ± 3.4 b | 212.2 ± 13.1 b | 28.3 ± 4.4 c | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 581.4 ± 12.0 d | 40.9 ± 3.1 b | 208.2 ± 2.5 b | 26.6 ± 1.6 d |

| Tissues | Treatment | Carbohydrate Content (mg/g FW *) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Souble Sugar | Reducing Sugar | Sucrose | Starch | ||

| Leaf | Control | 1.00 ± 0.06 c | 0.96 ± 0.04 b | 12.38 ± 0.5 a | 35.10 ± 2.2 d |

| Cd | 1.28 ± 0.06 b | 0.90 ± 0.05 b | 13.20 ± 0.6 a | 40.52 ± 1.2 cd | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 1.22 ± 0.05 b | 1.55 ± 0.04 a | 13.98 ± 0.5 a | 41.00 ± 1.3 cd | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 1.65 ± 0.04 a | 1.68 ± 0.06 a | 14.00 ± 0.4 a | 48.10 ± 1.5 c | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 1.19 ± 0.05 b | 0.98 ± 0.05 b | 12.08 ± 0.4 a | 51.44 ± 1.4 b | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 1.29 ± 0.07 b | 1.04 ± 0.06 b | 13.36 ± 0.3 a | 60.81 ± 1.2 a | |

| Root | Control | 0.74 ± 0.01 c | 1.03 ± 0.01 a | 5.60 ± 0.2 c | 43.12 ± 2.3 b |

| Cd | 1.01 ± 0.03 b | 0.95 ± 0.02 ab | 6.99 ± 0.3 b | 45.12 ± 1.2 b | |

| Cd + nSe2 | 0.92 ± 0.02 b | 1.08 ± 0.03 a | 6.60 ± 0.2 b | 46.69 ± 1.4 b | |

| Cd + nSe5 | 1.31 ± 0.01 a | 1.09 ± 0.01 a | 8.10 ± 0.3 a | 55.90± 1.6 a | |

| Cd + nSe10 | 0.97 ± 0.01 b | 0.95 ± 0.02 ab | 7.11 ± 0.2 b | 47.57 ± 1.8 b | |

| Cd + nSe15 | 0.93 ± 0.01 b | 0.93 ± 0.01 ab | 6.74 ± 0.3 b | 48.99 ± 1.1 b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Lian, X.; Yao, R.; Shang, B.; Yi, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X. Synthesis, Antibacterial Properties, and Physiological Responses of Nano-Selenium in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122750

Sun H, Lian X, Yao R, Shang B, Yi S, Yu J, Zhang B, Wang X. Synthesis, Antibacterial Properties, and Physiological Responses of Nano-Selenium in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122750

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Hongyan, Xin Lian, Runge Yao, Bingjie Shang, Siyu Yi, Jia Yu, Bo Zhang, and Xiaoyun Wang. 2025. "Synthesis, Antibacterial Properties, and Physiological Responses of Nano-Selenium in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122750

APA StyleSun, H., Lian, X., Yao, R., Shang, B., Yi, S., Yu, J., Zhang, B., & Wang, X. (2025). Synthesis, Antibacterial Properties, and Physiological Responses of Nano-Selenium in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress. Agronomy, 15(12), 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122750