Abstract

Global warming has increasingly reduced winter chill accumulation in traditional fruit-growing regions, disrupting dormancy release and bloom synchrony in deciduous fruit crops such as peach (Prunus persica). To evaluate adaptation potential under subtropical conditions, a three-year field study was conducted in central Taiwan using two low-chill cultivars, ‘Tainung No.4 Ruby’ (~100 chilling units, CU) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (~77 CU). Our results demonstrate that both cultivars produced long shoots (>34 nodes), completed vegetative growth by October, and reached natural leaf fall by mid-November. Nonlinear Gompertz and Logistic models accurately described shoot elongation dynamics and growth cessation. Flowering began in mid-January for ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ and mid-February for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’. Seasonal chill accumulation strongly influenced the onset of flower budbreak between apical and basal buds: in the milder 2023–2024 winter (~120 CU), apical–basal onset lags were wider (22 days in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’), whereas in the colder 2024–2025 winter (~280 CU), these lags shortened (14 days). Notably, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ maintained a consistent apical–basal onset lag between seasons, indicating greater positional stability under variable chilling. Field-estimated CU thresholds for flower budbreak exceeded the reported chilling requirements, suggesting reduced chilling efficiency under fluctuating subtropical winter temperatures. These results demonstrate that integrating shoot growth, leaf fall timing, and chill–heat accumulation provides a phenology-informed framework for cultivar selection and orchard scheduling, thereby enhancing climate resilience of peach production in warm-winter regions.

1. Introduction

Global climate change poses a growing threat to temperate fruit production, particularly through warmer winters that reduce the accumulation of chilling needed to release bud dormancy in deciduous fruit crops [1,2]. Many species, including peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch.], exhibit cultivar-specific chilling requirements that must be met during dormancy to ensure timely and synchronized budbreak in spring. When winter chill is inadequate, trees often show delayed budbreak and erratic flowering, severely compromising productivity [3]. Insufficient winter chill is therefore increasingly recognized as a major constraint on the sustainability of temperate fruit production in warm-winter regions [4]. Central Taiwan’s lowlands have a humid subtropical climate (Köppen classification: Cfa), with mild winters and hot, wet summers, similar to other low-chill peach regions in Southeast Asia and South America [5]. In this study, we treat central Taiwan as a representative case of humid subtropical peach production, while recognizing that local climates within the broader subtropical belt remain heterogeneous. This climatic context emphasizes the need to better understand and mitigate the impacts of warming winters on deciduous fruit phenology.

Synchrony of dormancy release and flowering is critical for productivity in deciduous fruit trees. Dormancy allows trees to align bloom timing with favorable spring conditions, thereby reducing the risk of frost injury and ensuring effective pollination [6,7]. However, in subtropical climates, the bud dormancy of high-chill peach cultivars is often released only partially or unevenly, resulting in asynchronous budbreak and flowering [8]. This lack of uniformity impairs crop management and yield. Growers in mild-winter regions must therefore closely monitor phenological development and often rely on horticultural interventions to compensate for insufficient chill. Common practices include artificial defoliation in fall and the application of defoliants or bud-breaking agents such as hydrogen cyanamide to promote timely and uniform budbreak [3,9,10]. These strategies highlight the importance of achieving synchronized dormancy release and flowering in subtropical production systems. However, these chemical approaches are reactive measures and do not address the underlying mismatch between cultivar physiology and local climate.

Developing and deploying low-chill peach cultivars represents a proactive and long-term adaptation strategy. Breeding programs in Florida and southern China have released cultivars that complete dormancy with <200 chilling units (CU), expanding production into low-elevation subtropical zones [11,12,13,14]. In Taiwan, the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute (TARI) has released several low-chill cultivars—such as ‘SpringHoney’ (~180 CU), ‘Xiami’ (~125 CU), ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (~100 CU), and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (~77 CU)—enabling stable fruiting in areas where annual chill rarely exceeds 150 CU [15,16]. Comparable breeding efforts in Brazil and Thailand [13,17] highlight the global convergence toward subtropical adaptation as a response to climate warming.

Despite the increasing availability of low-chill cultivars, relatively little is known about phenological behavior and growth dynamics in low-chill cultivars under warm-winter conditions. Most classical dormancy and bloom models were developed using high-chill cultivars grown in temperate climates [18], and may not be applicable to subtropical systems. While recent efforts have aimed to develop modeling frameworks for deciduous fruit trees in tropical and subtropical climates [2], key processes such as vegetative growth flushes, leaf senescence, and reproductive timing in low-chill peaches remain poorly characterized. Specifically, few studies have quantitatively compared intra-shoot flowering synchrony and chilling–heat accumulation dynamics across subtropical low-chill peach cultivars under field conditions. This lack of empirical phenological data limits the ability of growers and researchers to optimize orchard management and cultivar deployment under changing climate scenarios.

This study aimed to elucidate the vegetative and reproductive phenology of two low-chill peach cultivars, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, grown under subtropical field conditions in central Taiwan. Specifically, we (i) modeled shoot elongation and leaf fall dynamics using nonlinear regression, and (ii) quantified chilling and heat accumulation requirements for apical and basal budbreak. Rather than evaluating yield or fruit quality, we focused on identifying phenological markers and chill–heat thresholds that can inform cultivar selection and management decisions in warm-winter orchards.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Plant Materials

The field experiment was conducted at the experimental orchard of TARI, Wufeng District, Taichung City, Taiwan (24°02′ N, 120°68′ E; elevation 91 m) (Figure S1). Four-year-old trees of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and nine-year-old trees of ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, both grafted onto ‘Kutaw’ (Prunus persica) rootstock, were used. Trees were trained to an open-center system with a spacing of 5 m × 4 m. Annual fertilizer applications included 5 kg of a commercial composted bagasse (1.5–0.9–1.5; organic matter content at 55%) (No. 11, Taiwan Sugar Corp, Tainan, Taiwan) per tree in early March and 40 kg per 0.1 ha of a compound fertilizer (15–15–15–4; N–P2O5–K2O–MgO; No. 43, Taiwan Fertilizer Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) in early June.

2.2. Shoot Growth Measurement

In the summer of 2022, three trees of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and four trees of ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ were monitored, with ten representative one-year proleptic shoots per tree; in the summer of 2023 and 2024, three trees of each cultivar were monitored, with fifteen representative one-year proleptic shoots. We tagged sun-exposed, one-year proleptic shoots in the mid–upper canopy, avoiding vigorous water sprouts and heavily shaded interior branches. Observations were conducted weekly from 1 July to 16 September 2022 (12 measurements), from 21 July to 28 October 2023 (15 measurements), and every 1–2 weeks from 20 June to 17 October 2024 (13 measurements).

2.3. Shoot Growth and Leaf Fall Curve Fitting

Shoot length dynamics were modeled in JMP® Student Edition 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) using four nonlinear sigmoid functions: three-parameter Gompertz (Gompertz-3P), three-parameter Logistic (Logistic-3P), four-parameter Gompertz (Gompertz-4P), and four-parameter Logistic (Logistic-4P). The four candidate models were chosen because they are widely used to describe sigmoidal growth processes in perennial crops and allow flexible representation of asymmetry, upper asymptote, and inflection timing [19,20], corresponding to Equations (1)–(4). Model performance was compared using the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc), which penalizes excessive model complexity and is recommended over AIC when sample size is limited. For each cultivar × year combination, the model with the lowest AICc was selected as the best-fitting representation of shoot growth.

In Equations (1) and (2), y represents the shoot length or leaf fall percentage, t the time (Julian date), a the asymptote, b the growth rate, and c the inflection point of the curve. In Equations (3) and (4), y represents the shoot length or leaf fall percentage, t the time (Julian date), a the upper asymptote, b the lower asymptote, c the growth rate, and d the inflection point of the curve.

2.4. Leaf Fall and Flowering Observation

On each tagged shoot, 20–30 fully expanded mature leaves were further marked, and the total number of leaves was recorded as the baseline. Observations were conducted in fall of 2023 and 2024. In 2023, leaf counts were recorded weekly beginning on 24 August, with a total of 15 observations. In 2024, observations began on 6 September and were conducted every 1–2 weeks, for a total of 9 observations. During leaf fall, leaves on the same tagged shoots were counted at each observation date; the onset of leaf fall was defined when the average leaf number per shoot fell below 90% of the initial value, and completion of leaf fall when it fell below 10%. Leaf fall percentage was calculated as in Equation (5):

Leaf fall curves were fitted to four nonlinear models using JMP® Student Edition 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), as described in Section 2.3, and the best-fit model was selected using AICc.

For flowering observations, each tagged shoot was divided into three equal sections. Flower buds located on the distal one-third were defined as apical flower buds, while those on the basal one-third were defined as basal flower buds. Flower budbreak was defined when 10% of flower buds reached BBCH stage 53 [scales separated and green bud visible [21]]. The end of flowering was defined when the percentage of open flowers [BBCH stage 65 (full flowering)] declined below 10% due to senescence.

2.5. Calculation of Chilling and Heat Accumulation from the End of Leaf Fall to Budbreak

Hourly air temperature was recorded with HOBO MX2301A loggers (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA) installed at the site. Daily mean temperature data were obtained from the Central Weather Administration [https://codis.cwa.gov.tw/StationData (accessed on 1 July 2025); Station: G2F820].

Chilling accumulation was estimated using the Taiwan low-chill model [22,23] and expressed as chilling units (CU). In this model, each hour is weighted according to temperature as follows: ≤7.2 °C = +1; 7.3–15.0 °C = +0.5; 15.1–26.6 °C = 0; 26.7–27.8 °C = −0.5; and >27.8 °C = −1. This empirical weighting scheme was originally derived from long-term peach phenology records in Taiwan and was specifically calibrated for mild-winter environments with frequent alternation between cool nights and warm days. Under humid subtropical conditions similar to our site, the Taiwan low-chill model has since been shown to perform well under comparable subtropical conditions in southern Brazil, where it provided more realistic estimates of rest completion for low-chill peaches than temperate models such as the Utah and Dynamic models [24].

Unlike temperate chill models, the Taiwan low-chill model penalizes both moderately warm (26.7–27.8 °C) and hot (>27.8 °C) hours, thereby increasing sensitivity to the intermittent warm spells and diurnal temperature fluctuations that characterize subtropical winters. For these reasons, it is particularly suitable for quantifying effective chill in low-chill peach cultivars grown in low-latitude, mild-winter regions. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that model performance is climate-dependent and that its applicability to other subtropical zones should be evaluated against local phenological data.

Heat accumulation was calculated as growing degree hours (GDHs) according to [25], using Equation (6):

where T represents the hourly recorded air temperature.

For the CU values, accumulation was performed over a biologically defined window from the completion of leaf fall to the onset of flower budbreak for each cultivar × bud-position × season combination. The starting point was defined as the date when natural leaf fall on tagged shoots exceeded 90% of the initial marked leaves (completion of leaf fall; Section 2.4). The endpoint was defined as the date of flower budbreak for each bud position, i.e., when ≥10% of apical or basal flower buds reached BBCH stage 53 (scales separated and green bud visible; Section 2.4). For the GDH values, the starting point was defined as the calendar date on which the reported cultivar-specific chilling requirement was first satisfied (100 CU for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and 77 CU for ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’) [15,16]. The endpoint was defined as the observed date of apical or basal flower budbreak. Thus, the reported GDH values represent the forcing heat required during ecodormancy, once nominal chill requirements had been met. The resulting CU and GDH values thus represent field-estimated chill and heat requirements for visible budbreak under natural subtropical conditions, integrating both endodormancy release and subsequent ecodormancy forcing rather than purely the minimum chill requirement for endodormancy break.

2.6. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

Shoot length, node number, and leaf fall percentage were analyzed using a two-factor completely randomized design. Fixed effects included cultivar, observation date, and their interaction (cultivar × date). Each tree was treated as an experimental unit: in 2022, three trees of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and four trees of ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ were evaluated, while in 2023 and 2024, three trees of each cultivar were observed. Because repeated measurements were conducted on the same trees over time, individual tree (replicate) was included as a random effect, and Julian date was incorporated as a continuous covariate to improve the fit of time-series models.

We did not include “Year” as a fixed factor in a combined multi-year model, because only two to three years were available and winter conditions differed strongly among seasons, particularly in chill accumulation. Under these circumstances, a cultivar × year model would have been weakly powered and difficult to interpret biologically. Instead, we treated each year as a distinct climatic scenario and emphasized season-specific cultivar responses. Cross-year differences in phenology and model parameters were therefore interpreted descriptively rather than through formal year-by-year hypothesis testing.

All statistical analyses were performed using the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) procedure in JMP® Student Edition 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Multiple comparisons were conducted with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test, with statistical significance declared at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Shoot Length

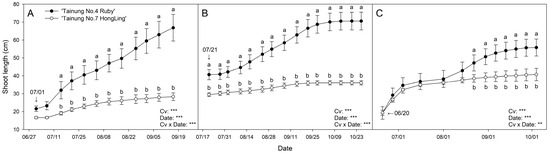

Across all years, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ exhibited more vigorous shoot elongation than ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (Figure 1). In 2022, cultivar differences became significant from July 15, as ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ increased from 21.6 to 66.9 cm (+210%), whereas ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ increased from 16.6 to 28.3 cm (+70%). In 2023, elongation of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ peaked between late July and late September before plateauing at 70.6 cm (+74%), while ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ stabilized at 36.1 cm (+22%). In 2024, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ again showed greater cumulative growth (19.3 to 55.8 cm; +189%) than ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (19.3 to 40.7 cm; +111%). Overall, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ consistently elongated more rapidly and attained longer final shoot lengths than ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ across all growing seasons.

Figure 1.

Shoot length of one-year-old shoot in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (solid symbols) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (open symbols) in summer of 2022 (A), 2023 (B) and 2024 (C). Cv, Date, and Cv × Date indicate the effect of the cultivar, time, and interaction between the cultivar and time, respectively. ** and *** indicate treatment effects are significant at p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively. Means and SE are presented. Means (n = 3–4) with different letters within each measurement day are significantly different at p < 0.05 (Fisher’s LSD test).

3.2. Node Number

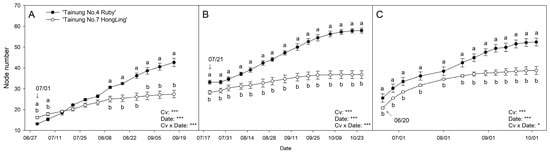

‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ consistently produced more nodes per shoot than ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ across all seasons (Figure 2). In 2022, differences became evident by August 11, with ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ increasing from 13.2 to 42.6 nodes (+223%) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ from 16.2 to 27.5 (+70%). In 2023, cultivar effects were significant from July 21, as ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ rose from 33.2 to 58.0 nodes (+75%) compared with 28.3 to 36.8 (+30%) in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’. In 2024, similar trends were observed as in 2023. Overall, node formation was faster and reached higher final counts in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ than in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’.

Figure 2.

Node number of one-year-old shoot in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (solid symbols) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (open symbols) in 2022 (A), 2023 (B) and 2024 (C). Cv, Date, and Cv × Date indicate the effect of the cultivar, time, and interaction between the cultivar and time, respectively. * and *** indicate treatment effects are significant at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively. Means and SE are presented. Means (n = 3–4) with different letters within each measurement day are significantly different at p < 0.05 (Fisher’s LSD test).

3.3. Nonlinear Model Selection for Shoot Growth

For shoot length, nonlinear models were evaluated separately for each cultivar and year. In 2022, the Gompertz-3P model produced the lowest AICc for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’, whereas the Gompertz-4P model was optimal for ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’. In 2023, the Logistic-4P model yielded the lowest AICc for both cultivars and was selected as the best-fitting model. In 2024, the Gompertz-3P model provided the lowest AICc for both cultivars (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Best-fitting nonlinear models for shoot length of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ during 2022–2024.

Table 2.

Best-fitting nonlinear models for shoot length of ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ during 2022–2024.

3.4. Leaf Fall Timing and Dynamics

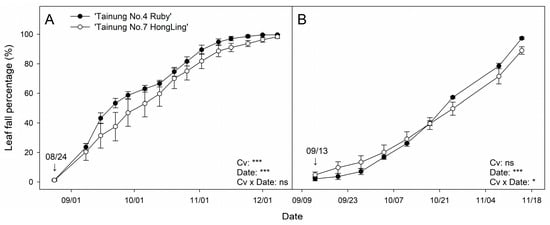

Leaf fall percentage differed between cultivars in 2023 (Figure 3; Table 3). In 2023, leaf fall for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ occurred from 8 September to 10 November (63 d), while ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ proceeded from 15 September to 16 November (62 d). In 2024, leaf fall shifted later and was shorter: ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ from 11 October to 15 November (35 d) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ from 4 October to 15 November (42 d). Relative to 2023, onset was delayed by 33 d for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and 19 d for ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, with durations shortened by 28 and 20 d, respectively.

Figure 3.

Leaf fall percentage of one-year-old shoot in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (solid symbols) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (open symbols) in 2023 (A) and 2024 (B). Cv, Date, and Cv × Date indicate the effect of the cultivar, time, and interaction between the cultivar and time, respectively. *, *** and ns indicate treatment effects are significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.001 and not significant, respectively.

Table 3.

Leaf fall period of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ in 2023 and 2024.

Trajectories differed across years: In 2023, leaf fall curves were best described by a Logistic-4P model (rapid post-inflection decline) in both cultivars, whereas 2024 patterns fit a Gompertz-3P model (smoother, gradual decline) in both cultivars (Table 4 and Table 5). Despite these differences, both cultivars consistently completed natural leaf fall around mid-November.

Table 4.

Best-fitting nonlinear models for leaf fall percentage in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ in 2023 and 2024.

Table 5.

Best-fitting nonlinear models for leaf fall percentage in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ in 2023 and 2024.

3.5. Flowering Period by Bud Position

In 2023–2024, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ apical buds flowered from 16 February to 8 March (21 d), while basal buds flowered from 23 February to 15 March (21 d) (Table 6). The apical–basal onset lag was 7 d, and both bud positions maintained similar flowering durations. ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ initiated flowering earlier and exhibited a longer duration: apical buds flowered from 15 January to 1 March (46 d), and basal buds from 6 February to 1 March (24 d), resulting in an apical–basal onset lag of 22 d.

Table 6.

Flowering period of apical and basal buds in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ in 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 season.

In 2024–2025, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ showed a slightly longer bloom period, with apical buds flowering from 14 February to 12 March (26 d) and basal buds from 21 February to 6 March (13 d). The apical–basal onset lag remained 7 d, consistent with the previous year. ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ apical buds flowered from 10 January to 21 February (42 d), while basal buds flowered from 24 January to 21 February (28 d). The apical–basal onset lag narrowed to 14 d.

Across years and cultivars, apical buds consistently preceded basal buds. ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ not only initiated flowering earlier but also maintained a longer flowering period than ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’. Notably, its apical–basal onset lag shortened from 22 d (2023–2024) to 14 d (2024–2025), but that of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ was not changed between the two seasons.

3.6. Estimated Chilling Requirements and Heat Accumulation for Apical and Basal Budbreak

Chilling units (CU) and growing degree hours (GDHs) associated with apical and basal flower budbreak, calculated over the windows defined in Section 2.5, are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Chilling units (CU) accumulated from completion of leaf fall to flower budbreak, and growing degree hours (GDHs) accumulated from satisfaction of nominal chilling requirements to flower budbreak, for apical and basal buds of in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ during 2023–2024 and 2024–2025.

In 2023–2024, both apical and basal buds of ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ accumulated 113.5 CU before budbreak, but basal buds required 2888 GDHs more than apical buds for budbreaking. In ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, apical buds accumulated 78.0 CU and 650 GDHs, whereas basal buds required 81.5 CU and 7784 GDHs.

In 2024–2025, chill accumulation increased substantially. ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ apical buds accumulated 273.5 CU and 9663 GDHs, while basal buds accumulated 274.5 CU and 12,047 GDHs. For ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, apical buds accumulated 101.0 CU and 1166 GDHs, while basal buds required 176.5 CU and 4724 GDHs.

Across cultivars and years, basal buds consistently demanded greater heat accumulation than apical buds, reflecting delayed dormancy release and slower reactivation of basal nodes. Within-year CU totals were generally similar between positions, except in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ during 2024–2025, when basal buds required markedly higher CU. The high-chill winter (2024–2025) corresponded with greater overall CU accumulation and a narrower apical–basal interval in the onset of flowering (Figure A1; Table 7), indicating that enhanced chilling promoted more synchronous bud development along the shoot.

4. Discussion

Across three warm-winter seasons, both ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ and ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ completed vegetative growth and leaf fall by mid-November and flowered reliably; however, higher winter chill compressed apical–basal onset lags, while marginal chill increased apical–basal onset lags—revealing cultivar-specific phenological strategies with direct management consequences.

4.1. Low-Chill Cultivars as a Climate-Resilient Strategy

Winter warming has become a critical constraint for temperate fruit production, as reduced chill accumulation increasingly prevents traditional high-chill cultivars from meeting chilling requirements. Such deficits have already caused severe crop losses, for example, the southeastern United States lost approximately 70% of its peach crop in 2017 due to a mild winter [26]. Modeling studies similarly predict that high-chill cultivars (>800 CU) will frequently fail to satisfy chilling needs by mid-century [4,27,28]. By contrast, low-chill cultivars reliably achieve budbreak under mild winters, thereby stabilizing production in warming climates.

Breeding programs in Taiwan, Florida, Brazil, and southern China have released cultivars fruiting with approximately 100–300 chill units [12,13,14,15,17,29,30]. Taiwan’s subtropical breeding program at TARI, for example, maintains ~200 adapted accessions and has released cultivars such as ‘SpringHoney’, ‘Xiami’, and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, which perform well at low elevations with minimal winter cold [15,16,30,31,32]. These cultivars are becoming increasingly important in the context of global warming, extending commercial peach production into regions once considered unsuitable [12].

Our observations reinforce this adaptation pathway. Both ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ flowered consistently under subtropical conditions, but with distinct phenological profiles. ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’s’ later and more synchronous flowering can improve pollination efficiency but may increase exposure to subtropical rainy or typhoon seasons. Conversely, ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’s’ earlier budbreak and extended flowering period may provide a market advantage by advancing harvest dates, yet this also raises the risk of flowering asynchrony or frost exposure.

4.2. Impacts of Insufficient Chill on Leaf Fall and Flowering Synchrony

Leaf fall dynamics in both cultivars followed seasonal patterns but varied across years, reflecting differences in fall temperature regimes. In 2023, Logistic-4P curves captured a rapid post-inflection decline in leaf number, while in 2024, Gompertz-3P models indicated a smoother, more gradual leaf fall, likely due to warmer late-fall conditions in 2024. Despite interannual variability, completion of leaf fall by mid-November remained a consistent phenological marker across cultivars, suggesting the onset and establishment of dormancy as reported for other deciduous fruit species [33].

Basal buds consistently showed higher GDH values at budbreak than apical buds, indicating that they needed more accumulated thermal forcing to reach the same developmental stage, consistent with a deeper residual dormancy under marginal chilling. This positional variation in dormancy status along the shoot likely reflects a combination of hormonal, carbohydrate, and vascular factors. Apical buds are known to have higher sink strength, faster vascular connectivity, and elevated cytokinin and gibberellin levels, while basal buds typically exhibit deeper dormancy and elevated ABA [34,35,36]. These differences explain both the onset lag and the extended bloom duration observed under marginal chill conditions.

Interestingly, the apical–basal lag in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ narrowed from 22 days in 2023–2024 to 14 days in 2024–2025, while ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ maintained a consistent 7-day lag. This plasticity in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ suggests a stronger environmental modulation of dormancy depth across bud positions, with higher chill accumulation promoting uniform dormancy release along the shoot. These findings indicate that adequate chilling synchronizes bud development along the shoot, while insufficient chill amplifies intra-shoot heterogeneity, consistent with prior observations in peaches and other Prunus species [1,37]. Although low-chill cultivars mitigate the risk of dormancy failure, they remain susceptible to erratic flowering under marginal chill. Many such cultivars possess shallower endodormancy and can prematurely resume growth during mid-winter warm spells [37], as observed in ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’. Its earlier and longer flowering window compared with ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ suggests genotypic differences in chill responsiveness.

Interestingly, the reported chilling requirements for ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (~100 CU) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (~77 CU) were lower than the field-estimated CU accumulated between completion of leaf fall and flower budbreak in our study (Table 7). This discrepancy likely arises from differences in methodology and environmental context. For ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’, the reported chilling requirement was inferred from its bloom synchrony with the Florida cultivar ‘Flordred’ rather than from a standardized chill model [16]. By contrast, the estimate for ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ was obtained via single-node cuttings under forcing conditions combined with the Taiwan low-chill model [15]. Field observations integrate diurnal variability, warm interruptions, and fluctuating humidity, all of which lower chilling efficiency; consequently, nominal CU values from controlled assays should be regarded as relative indices of adaptability rather than absolute thresholds.

Notably, although total chill accumulation was higher in 2024–2025 (~280 CU) than in 2023–2024 (~120 CU) (Figure A1), both cultivars required greater cumulative chill to promote budbreak. The higher field-estimated CU thresholds in 2024–2025 likely reflect lower chilling efficiency due to temperature-sequence effects: despite greater nominal CU, effective chill was fragmented by alternating warm and cool spells, as shown by the distribution of CU and GDHs over time. In such winters, buds appear to remain in a deeper residual dormancy and therefore accumulate more GDHs before visible budbreak, which manifests as higher GDH values at budbreak rather than GDHs itself being a causal driver. Such sequence sensitivity has been well documented: intermittent warming can nullify previous chill accumulation [38], while this loss of chill efficiency can be quantified using multi-environment delineation of chill-effective periods [39]. Our temperature records show similar fluctuations in winter of the 2024–2025 season (Figure A1B), suggesting the diminished chilling efficiency and delayed dormancy release. Physiological carry-over effects may have compounded this response. Increased tree age, carbohydrate depletion, or prior fruit load can deepen endodormancy and raise chilling requirements [40,41]. Together, these climatic and biological factors explain why the apparent CU thresholds were higher in the second season and reinforce that total CU does not necessarily equate to effective chill accumulation under variable subtropical conditions.

Comparable variability among Prunus cultivars has been reported elsewhere [42]. Compensatory interactions between chill and heat accumulation [43] further explain this plasticity: when chill accumulation is limited but followed by ample warmth, full bloom can still occur, though over an extended period; when both chill and subsequent heat are inadequate, flowering remains partial and erratic. Hence, integrating chill-efficiency modeling with phenology monitoring is essential for improving dormancy prediction and management in warm-winter orchards.

4.3. Adaptation Strategies for Warm-Winter Regions

Our results indicate that model-based descriptions of growth (e.g., Gompertz, Logistic) are decision-oriented summaries: they convert many observations into a few interpretable parameters (e.g., upper asymptote, rate, and inflection) that signal phase changes (e.g., onset of plateau and approach to dormancy) and allow standardized comparison across years and cultivars [20]. In perennial crops, such sigmoid models are widely recommended because many plant processes are inherently nonlinear; their parameters improve robustness and comparability relative to ad hoc linear fits, especially when seasons differ [20]. In peaches, phenology models typically pair chill and heat to predict budbreak and flowering periods [43], but vegetative shoot dynamics also condition later phenological stages by governing the timing of growth slowdown and leaf senescence. We suggest that identifying inflection timing (c) and rate (b) from Gompertz/Logistic curves therefore provides operational markers for: (i) pruning and vigor regulation (when elongation is plateauing); (ii) nutrient and water scheduling as shoots shift from extension to maturation; and (iii) anticipating the onset of bud dormancy and likely bloom synchrony in the following winter (via the link we observe between extended late-summer growth, delayed leaf fall, and subsequent CU/GDH patterns).

It should be noted that ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ (4 years old) and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ (9 years old) differed in tree age, which may have partially contributed to the observed differences in shoot vigor and growth rate in this study. Tree age can influence vegetative–reproductive balance, carbohydrate storage, and shoot elongation potential, thereby modulating apparent growth dynamics independently of genotype. Future trials should include age-matched trees across multiple orchards to better disentangle age-related effects from genotypic and climatic influences.

In addition, effective adaptation in subtropical peach production should be anchored in phenology-informed cultivar selection and season-specific management, rather than generic prescriptions. Under marginal winter chill (~120 CU, as in 2023–2024), cultivars with inherently earlier budbreak, such as ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, can ensure timely flowering but may exhibit wide apical–basal onset gaps and prolonged flowering period. In contrast, under higher chill conditions (~280 CU, as in 2024–2025), later-flowering cultivars such as ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ exhibit more synchronous bloom and a shorter flowering period. Notably, ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ maintained a consistent apical–basal onset lag between low- and high-chill seasons, suggesting greater positional stability in its developmental response to variable chilling. However, its later phenology may shift harvest closer to the rainy or typhoon period, requiring adjustments in disease control and harvest logistics.

These cultivar-specific patterns highlight the need for flexible management frameworks that align orchard design, pollination planning, and labor scheduling with each season’s chill–heat regime to sustain productivity in warm-winter regions. Shorter-term interventions include chemical bud-breaking agents such as hydrogen cyanamide and alternatives like calcium cyanamide, gibberellins, or dormancy oils, which can synchronize budbreak in insufficient-chill years [10,44]. In Taiwan, two urea foliar sprays in December significantly advanced defoliation and budbreak of ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’, performing comparably to hydrogen cyanamide [3]. Site selection (e.g., cold-air drainage zones), evaporative cooling, and rootstock choice further influence chilling microclimates [45,46]. An integrated approach combining low-chill cultivars with precise cultural practices, such as pruning, irrigation scheduling, and pollinator management, can mitigate both insufficient chill and erratic phenology.

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

This study analyzed each season independently rather than including “Year” as a fixed factor in a combined model. With only three years and strongly contrasting winter conditions, we treated each season as a distinct climatic scenario instead of fitting a cultivar × year model with limited degrees of freedom and ambiguous biological interpretation. This year-by-year framework supports the practical objective of providing season-specific guidance: for example, in low-chill winters (~120 CU), extended bloom and wider apical–basal gaps should be anticipated and compression tactics planned, whereas in higher-chill winters (>280 CU), flowering periods are shorter and more synchronous, requiring coordinated pollination and labor scheduling. However, this approach limits formal cross-year hypothesis testing, and our comparisons of seasonal differences are therefore descriptive rather than inferential.

Future work should therefore integrate phenology with productivity metrics by coupling apical–basal bloom gaps, CU/GDH trajectories, and leaf fall timing with fruit set, crop load, yield, and quality data. Such integration would allow derivation of operational phenology–yield relationships and economic thresholds for low-chill peach management under subtropical conditions. In addition, the chilling model itself merits further evaluation: although the Taiwan low-chill model is well calibrated for mild winters and has shown good performance in other low-latitude regions, its universality remains uncertain. Comparative analyses using the Taiwan low-chill model alongside the Dynamic model or locally calibrated chill models across multiple subtropical sites and years would help refine chill metrics and test their transferability.

In addition, emerging evidence shows that bud deacclimation and frost hardiness dynamics are tightly coupled with dormancy progression [47]. Incorporating frost-hardiness or bud water-potential monitoring into field phenology studies could help distinguish between incomplete endodormancy release and residual cold acclimation in marginal-chill seasons. Ultimately, these refinements will strengthen the predictive and decision-support capacity of phenology-informed cultivar selection, linking modeled growth transitions and chill–heat trajectories to orchard design, pollination scheduling, and adaptive management in subtropical peach production.

5. Conclusions

Across three seasons in a subtropical lowland in Taiwan, both low-chill peaches, ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ and ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’, completed shoot growth and natural leaf fall by mid-November and flowered reliably, confirming their suitability for warm-winter production. Cultivar phenology diverged: ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ broke bud earlier and flowered longer, whereas ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ flowered later with tighter synchrony. Interannual chill strongly modulated flowering dynamics: higher chill (~280 CU) compressed apical–basal onset lags and shortened bloom windows, while marginal chill (~120 CU) widened lags and prolonged flowering. Field CU needs for budbreak exceeded previously reported chilling requirements, likely reflecting methodological differences and reduced chilling efficiency under fluctuating subtropical temperatures. These results show that nominal CU values should be treated as relative indicators, not strict thresholds. Practically, integrating phenology markers (shoot-growth inflection, leaf fall completion) with chill–heat tracking supports phenology-informed cultivar selection and scheduling of pruning, pollination, and bud-breaking treatments. Such alignment provides a pragmatic pathway to stabilize yield and enhance climate resilience in warm-winter peach orchards.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122748/s1, Figure S1: Morphological characteristics of canopy structure (A and F), leaves (B and G), one-year shoots (C and H), flowers (D and I), and fruits (E and J) in ‘Tainung No. 4 Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7 HongLing’ peach trees, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L., C.-C.H. and S.-Y.L.; methodology, H.L.; and C.-C.H.; software H.L. and C.-C.H.; validation, H.L. and C.-C.H.; formal analysis, H.L.; resources, C.-C.H.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-C.H. and S.-Y.L.; visualization, H.L.; supervision, C.-C.H. and S.-Y.L.; project administration, S.-Y.L.; funding acquisition, C.-C.H. and S.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Agriculture and Food Agency (grant number: 111AS-4.2.3-FD-Z3) and by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (grant number: 113-2313-B-005-006-MY3). The APC was funded by the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This article is derived from the Master’s thesis by Hsuan Lee, “Study on the Phenology and Flower Bud Dormancy in ‘Tainung No. 4—Ruby’ and ‘Tainung No. 7—HongLing’ Peach”, Department of Horticulture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan, 2025. We thank Ching-Cheng Chen at the Department of Horticulture, National Chung Hsing University, and Kuo-Tan Li at the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, National Taiwan University, for critical comments on the original results. During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT (https://chatgpt.com, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) in order to correct grammar and improve the structure. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content to ensure accuracy and clarity and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

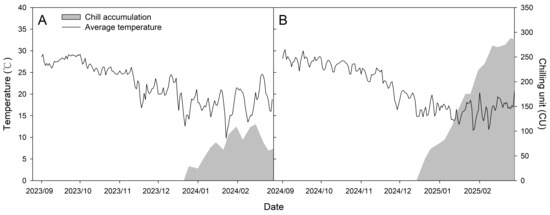

During the 2023–2024 winter, daily mean temperatures fluctuated considerably, especially from December through February of the following year. Chilling began accumulating on 21 December; due to fluctuations in daily mean temperature, four episodes of decreased chilling accumulation were observed (Figure A1). In 2024–2025, low temperatures occurred later overall; however, the start date of chilling accumulation occurred one week earlier than the previous year (14 December). Because daily mean temperatures fluctuated less than in the prior year, total chilling accumulation was higher.

Figure A1.

Comparison of average daily temperature (black line) and chill accumulation (gray area, Taiwan low-chill model) between the 2023–2024 (A) and 2024–2025 (B) winters. The second winter accumulated markedly more chilling units (~280 CU) than the first (~120 CU), reflecting a colder and more prolonged cool period.

References

- Campoy, J.A.; Ruiz, D.; Egea, J. Dormancy in temperate fruit trees in a global warming context: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.-M.; Ezzat, A.; El-Ramady, H.; Alam-Eldein, S.M.; Okba, S.K.; Elmenofy, H.M.; Hassan, I.F.; Illés, A.; Holb, I.J. Temperate fruit trees under climate change: Challenges for dormancy and chilling requirements in warm winter regions. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.; Lin, S.-Y. Foliar Urea sprays induce budbreak in peach via rapid non-structural carbohydrate metabolism—A lower-toxicity alternative to hydrogen cyanamide. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 349, 114267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedeling, E. Climate change impacts on winter chill for temperate fruit and nut production: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 144, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.H. Trends and progress of low chill stone fruit breeding. In Production Technologies for Low-Chill Temperate Fruits, Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 19–23 April 2004; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2005; pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, M.; Erez, A.; Rowland, L.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Norman, H.A. Bud dormancy in perennial fruit trees: Physiological basis for dormancy induction, maintenance, and release. HortScience 1997, 32, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.A.; Early, J.D.; Martin, G.C.; Darnell, R.L. Endo-, para-, and ecodormancy: Physiological terminology and classification for dormancy research. HortScience 1987, 22, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scariotto, S.; Citadin, I.; Raseira, M.D.C.B.; Sachet, M.R.; Penso, G.A. Adaptability and stability of 34 peach genotypes for leafing under Brazilian subtropical conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 155, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clavijo-Herrera, J.; Sarkhosh, A. Subtropical Peach Defoliation and Chill Hours; EDIS; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chhajed, S.; Vashisth, T.; Olmstead, M.A.; Olmstead, J.W.; Colquhoun, T.A. Transcriptomic study of early responses to the bud dormancy-breaking agent hydrogen cyanamide in ‘TropicBeauty’ peach. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2019, 144, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, I.; Sherman, W.B. Evaluation and breeding of peaches and nectarines for subtropical Taiwan. Acta Hortic. 2002, 592, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, B.L.; Sherman, W.B.; Raseira, M.C.B. Low-chill cultivar development. In The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses; Layne, D.R., Bassi, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 106–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sobierajski, G.R.; Harder, I.C.F.; Xavier, D.; Anoni, C.O. Breeding peaches for low-chill in São Paulo State, Brazil. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1127, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Zhu, G.; Fang, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Zhao, P.; Guo, J.; Ding, T.; Guan, L.; et al. Genomic analyses of an extensive collection of wild and cultivated accessions provide new insights into peach breeding history. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Wen, I.-C.; Lin, S.-Y. Tainung No. 7 HongLing: A Low-chill peach cultivar for early fresh market. HortScience 2024, 59, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, I.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Breeding of Peach Cultivar “Tainung No. 4 (Ruby)”. J. Taiwan Agric. Res. 2014, 63, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Promchot, S.; Boonprakob, U.; Byrne, D.H. Genotype and environment interaction of low-chill peaches and nectarines in subtropical highlands of Thailand. Thai J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 41, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fadón, E.; Herrera, S.; Guerrero, B.; Guerra, M.; Rodrigo, J. Chilling and heat requirements of temperate stone fruit trees (Prunus sp.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agehara, S.; Carrubba, A.; Sarno, M.; Marceddu, R. Phenological assessment of hops (Humulus lupulus L.) grown in semi-arid and subtropical climates through BBCH scale and a thermal-based growth model. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archontoulis, S.V.; Miguez, F.E. Nonlinear regression models and applications in agricultural research. Agron. J. 2015, 107, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, V.U.; Graf, H.; Hack, H.; Heß, M.; Kennel, W.; Klose, R.; Mappes, D.; Seipp, D.; Stauß, R.; Steif, J.; et al. Phänologische entwicklungsstadien des kernobstes (Malus borkh und Pyrus communis L.), des steinobstes (Prunus arten), der johannisbeere (Ribes arten) und der (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.). Nachrichtenbl. Deut. Pflanzenschutzd 1994, 46, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, S.-K.; Chen, C.-L. Estimation of the chilling requirement and development of a low-chill model for local peach trees in Taiwan. J. Chin. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2000, 46, 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.-T.; Song, C.-W.; Ou, S.-K.; Chen, C.-L. A model for estimating chilling requirement of very low-chill peaches in Taiwan. Acta Hortic. 2012, 962, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.O.D.; da Silveira Pasa, M.; Sezerino, A.A.; Mello-Farias, P.; Petri, J.L.; Herter, F.G. A Survey of eight chilling models for apple trees in southern Brazil under mild winters. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2023, 51, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.A.; Seeley, S.D.; Walker, D.R.; Anderson, J.L.; Ashcroft, G.L. Pheno-climatography of spring peach bud development. HortScience 1975, 10, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.E.; Abatzoglou, J.T. Warming winters reduce chill accumulation for peach production in the Southeastern United States. Climate 2019, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedeling, E.; Zhang, M.; Girvetz, E.H. Climatic Changes lead to declining winter chill for fruit and nut trees in California during 1950–2099. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luedeling, E.; Girvetz, E.H.; Semenov, M.A.; Brown, P.H. Climate change affects winter chill for temperate fruit and nut trees. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milech, C.G.; Dini, M.; Franzon, R.C.; Raseira, M.d.C.B. Chilling requirement of four peach cultivars estimated by changes in flower bud weights. Rev. Ceres 2022, 69, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Wen, I.-C.; Lin, S.-Y. Tainung No.9 HongJin: The first yellow-fleshed, low-chill peach cultivar release from Taiwan. HortScience 2024, 59, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.-K.; Song, C.-W. ‘Xiami’ peach. HortScience 2006, 41, 1362–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.-K.; Wen, I.-C. ‘SpringHoney’ peach. HortScience 2003, 38, 633–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshev, A.V.; Beil, I.; Zohner, C.M.; Garrigues, R.; Campioli, M. The clockwork of spring: Bud dormancy timing as a driver of spring leaf-out in temperate deciduous trees. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 349, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Watermeyer, P.J.; Styrdom, D.K. Aspects of winter rest in apple trees. Crop Prod. 1981, 10, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Reig, C.; González-Rossia, D.; Juan, M.; Agustí, M. Effects of fruit load on flower bud initiation and development in peach. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, M.; Liu, D.; Wang, S.Y.; Stutte, G.W. Involvement of apical dominance in winter dormancy of apple buds. Acta Hortic. 1995, 395, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citadin, I.; Pertille, R.H.; Loss, E.M.S.; Oldoni, T.L.C.; Danner, M.A.; Júnior, A.W.; Lauri, P.-É. Do low chill peach cultivars in mild winter regions undergo endodormancy? Trees 2022, 36, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedeling, E.; Guo, L.; Dai, J.; Leslie, C.; Blanke, M.M. Differential responses of trees to temperature variation during the chilling and forcing phases. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 181, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Krefting, P.; Kunz, A.; Do, H.; Fadón, E.; Luedeling, E. Boosting statistical delineation of chill and heat periods in temperate fruit trees through multi-environment observations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 310, 108652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, O.M.; Prestrud, A.K. Low temperature, but not photoperiod, controls growth cessation and dormancy induction and release in apple and pear. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.A. Climate change challenges in temperate and sub-tropical fruit tree cultivation. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 558–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutiti, K.; Bellil, I.; Khelifi, D. A Study of chill and heat requirements of resilient apricot (Prunus armeniaca) varieties in response to climate change. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Carvajal, A.; Chaves-Córdoba, B.; Vinson, E.; Coneva, E.D.; Chavez, D.; Salazar-Gutiérrez, M.R. Modeling the budbreak in peaches: A basic approach using chill and heat accumulation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, I.A.; Møller, B.L.; Sánchez-Pérez, R. Chemical control of flowering time. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 68, erw427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, A. Means to compensate for insufficient chilling to improve bloom and leafing. Acta Hortic. 1995, 395, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghrab, M.; BenMimoun, M.; Masmoudi, M.M.; BenMechlia, N. Chilling trends in a warm production area and their impact on flowering and fruiting of peach trees. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 178, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, C.; Charrier, G.; Kovaleski, A.P.; Raymond, P.; Deslauriers, A.; Rossi, S. Is it cold enough? Effects of artificial and natural chilling on budbreak and frost hardiness in Acer Saccharum (Marsh.). Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).