1. Introduction

Soil heterogeneity, which is the fundamental determinant of grapevine performance, causes significant spatial variability in vine vegetative growth, nutrient uptake, and grape quality. This variability arises from a complex interplay of both inherent factors (like parent material and topography) and human-induced differences (including tillage practices, cultivation history, cultivar selection, and fertilizer application) [

1,

2,

3]. This spatial variability presents a major challenge for targeted vineyard management and necessitates the delineation of homogeneous management zones in a precision viticulture context, which facilitates more accurate, site-specific, and resource-efficient agricultural practices [

4,

5,

6]. The need to delineate homogeneous management zones to address soil heterogeneity and improve resource efficiency is critical for cultivating complex, demanding varieties like Xinomavro [

7]. Accounting for over 2000 ha mainly in the PDO regions of Northern Greece, Xinomavro is an iconic indigenous variety that is crucial to the Greek wine industry, particularly as a late-ripening variety resilient to climate change [

8]. Its grapes are chemically distinguished by a high proportion of stable anthocyanins and significant skin and seed tannins, which yield wines with characteristic dryness, astringency, and high aging potential [

7,

9].

Vineyard sampling often focuses on the shallow surface soil (typically 0−30 cm) for convenience. However, the true interface for resource uptake is the deeper, more functionally relevant active-integrated soil layer. This zone, which can extend to 75 cm or more, represents the full extent of the vine’s root system. Its actual depth is highly site-specific and is governed by soil physical properties, including compaction, texture, and mechanical resistance to root penetration [

10,

11]. By incorporating data from this biologically relevant, deeper layer, a better understanding of soil–plant interactions can be achieved, leading to a more accurate and functional delineation of management zones and therefore suggesting more precise fertilizer recommendations with reduced agricultural inputs [

12,

13].

The delineation of management zones (MZs) in vineyards typically relies on analyzing and integrating spatially variable data layers. However, the high number of variables and the high degree of correlation among numerous soil parameters often result in redundant and computationally complex datasets. The most common methodologies fall into two main categories: (a) Proximal Sensing and Geophysical Methods: This involves mapping inherent soil or vine properties quickly across the vineyard. Techniques like Apparent Electrical Conductivity (ECa) mapping (using devices like the Veris or EM38) are frequently used because ECa is strongly correlated with key soil properties (texture, water content, and depth), making it an excellent proxy for underlying variability [

14]; (b) Multivariate Statistical Analysis and Clustering: This is the primary analytical step where data layers (e.g., ECa, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), yield, topography, and soil parameters) are combined. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is often used to reduce the data dimensionality, followed by unsupervised classification techniques, most commonly k-means clustering, to group similar areas into distinct, functional management zones [

15].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a robust statistical technique for data dimensionality reduction, transforming a large set of potentially correlated variables into a smaller number of uncorrelated latent variables, known as principal components [

16,

17]. This is achieved by identifying orthogonal linear combinations of the original variables, where each new component is constructed to capture the maximum possible variance in the data. The first principal component accounts for the largest share of the variability, with each subsequent component capturing a decreasing proportion of the remaining variance. This process effectively identifies the most critical sources of variability within the dataset, providing a simplified yet highly informative representation of the underlying soil dynamics [

17,

18]. The resulting principal component scores are typically saved as new columns in the original dataset for further analysis. PCA has already been employed successfully to evaluate the underlying variability in soil properties [

13,

16].

While PCA identifies the variables and their contributions to the overall variability, it does not inherently group similar sample points. For this purpose, Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) serves as a critical complementary technique [

17,

18,

19,

20]. By applying HCA to the principal component scores, it is possible to objectively group soil samples with similar characteristics into distinct, internally homogeneous clusters [

16,

18,

19]. The hierarchical nature of the algorithm allows for the visualization of these relationships in a dendrogram, which clearly illustrates how data points are grouped together based on their similarity. This statistical clustering moves beyond simple correlations to provide a data-driven foundation for defining objective management zones by classifying vineyard sub-regions based on their integrated soil properties.

Finally, geospatial methodologies enable the practical application of statistical analysis in precision viticulture by facilitating the visualization and evaluation of the spatial distribution of soil characteristics [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Geostatistical techniques, such as spatial interpolation, are essential for translating the abstract statistical outputs of PCA and HCA into tangible, geographical maps [

13], and previous soil studies have used both these methods to present and identify soil variability [

25,

26]. By interpolating the principal component values and cluster results across the vineyard, it becomes possible to create detailed maps that visually depict the spatial extent of the potential management zones. These maps are invaluable tools for vineyard managers, providing a clear and actionable visual guide for implementing site-specific practices such as targeted irrigation, fertilizer application, and pruning strategies [

1,

27,

28]. The combination of statistical rigor and geospatial visualization ensures that the delineation of management zones is both scientifically sound and practically useful for optimizing vineyard performance.

This study aims to demonstrate that applying Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Clustering, in combination with spatial interpolation, can provide critical insights for the geospatial delineation of viticulture management zones. The study will compare soil information from both the top and integrated soil layers to assess their respective contributions to grapevine performance. Finally, integrated maps will be created, combining interpolated HCA results with laboratory data on grape characteristics. The proposed methodological framework not only establishes this study’s relevance and novelty but also provides a scalable and effective approach for delineating management zones in vineyards.

2. Materials and Methods

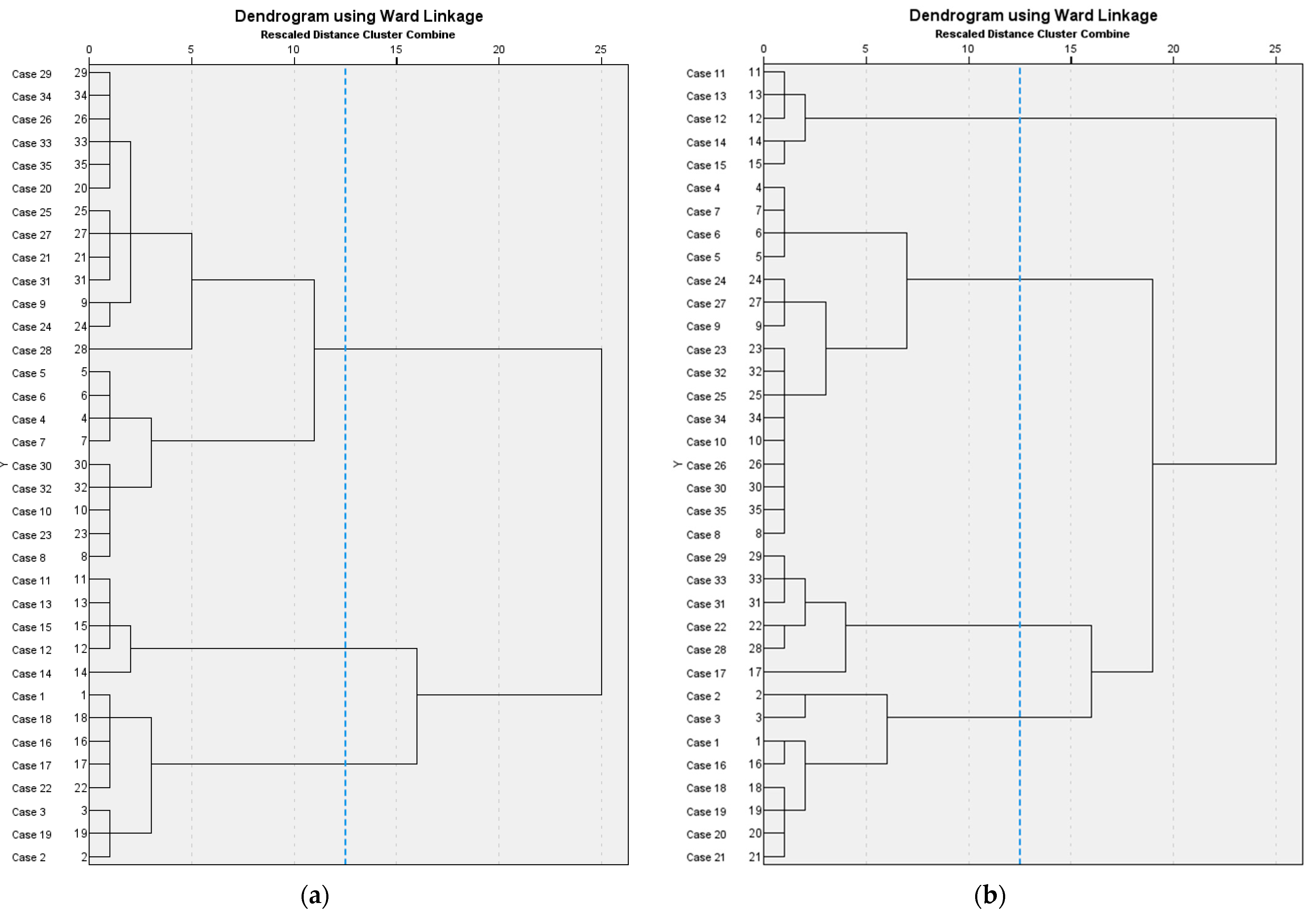

The study was conducted in a commercial vineyard located in the viticultural zone of Goumenissa, northern Greece, which produces wines of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) “Goumenissa” (

Figure 1). The experimental data were collected during the period of March to October 2004. A systematic sampling design was implemented to enable the integrated analysis of soil, root, and grape characteristics. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) on this comprehensive data highlighted the critical importance of deeper, integrated soil layer information over top-soil data for effective delineation of precision viticulture management zones.

Detailed information regarding the experiment is as follows:

Experimental vineyard and site description

The experimental field comprised a mature 1.0 ha vineyard located within the PDO viticultural zone of Goumenissa, northern Greece (40°52′24.76″ N, 22°29′10.90″ E). The vineyard was planted in 1991 with the red wine grape variety ‘Xinomavro’ (

Vitis vinifera L.), grafted onto R-110 rootstock. Vine spacing was 2.2 m between rows and 1.3 m within rows, with a north-to-south vine row orientation. The vines were pruned to 12 buds per vine and trained using a bilateral Royat system with three fixed trellising wires. Elevation ranged from 171 to 191 m above sea level, and the field was situated on a convex slope of approximately 10%, oriented eastward. The vineyard was managed under certified organic farming practices, and the standard cultivation protocols of the designated viticultural zone were applied, including drip irrigation. The soil was classified as Petric Calcisol, further subdivided into Epiclayic and Episiltic types, according to the IUSS Working Group WRB (2006) [

28].

Field Sampling Design

The sampling design aimed to obtain soil data representative of the entire field and appropriate for identifying relationships between soil properties and delineated soil management zones. The vineyard consisted of 58 rows, each containing 64 vines. A total of 35 plots were systematically selected to ensure coverage of the whole area (

Figure 1). Each plot comprised 24 vines (3 rows × 8 vines). Soil samples were collected from the center of each plot using a hand auger to a depth of 100 cm. Other terroir-related factors were not considered in the analysis, such as the limited spatial extent of the site and the uniformity in mesoclimate, slope, aspect, plant material, and management practices [

29].

Soil Data

Soil sampling was conducted in 35 plots (

Figure 1) using a hand auger to a depth of 100 cm. Soil horizons were distinguished in the field based on texture, effervescence upon reaction with 1:3 HCl, and Munsell color, and were subsequently sampled for laboratory analysis. A total of 19 soil indicators were determined, comprising 4 physical and 15 chemical parameters. The physical indicators included sand (%), silt (%), clay (%), and saturation percentage (SP, %). The chemical indicators included total calcium carbonate (CaCO

3, %), organic carbon (OC, %), pH, electrical conductivity (EC, dS/m), calcium (Ca, mg kg

−1), magnesium (Mg, mg kg

−1), potassium (K, mg kg

−1), sodium (Na, mg kg

−1), phosphorus (Olsen P, mg kg

−1), total nitrogen (TN, %), iron (Fe, mg kg

−1), manganese (Mn, mg kg

−1), copper (Cu, mg kg

−1), and zinc (Zn, mg kg

−1). Saturation percentage was determined from the saturation paste, while pH, EC, Ca, Mg, K, and Na were measured in the corresponding extract. Sample preparation and analytical procedures followed the methods described by Sparks [

2] and by Dane and Topp [

30].

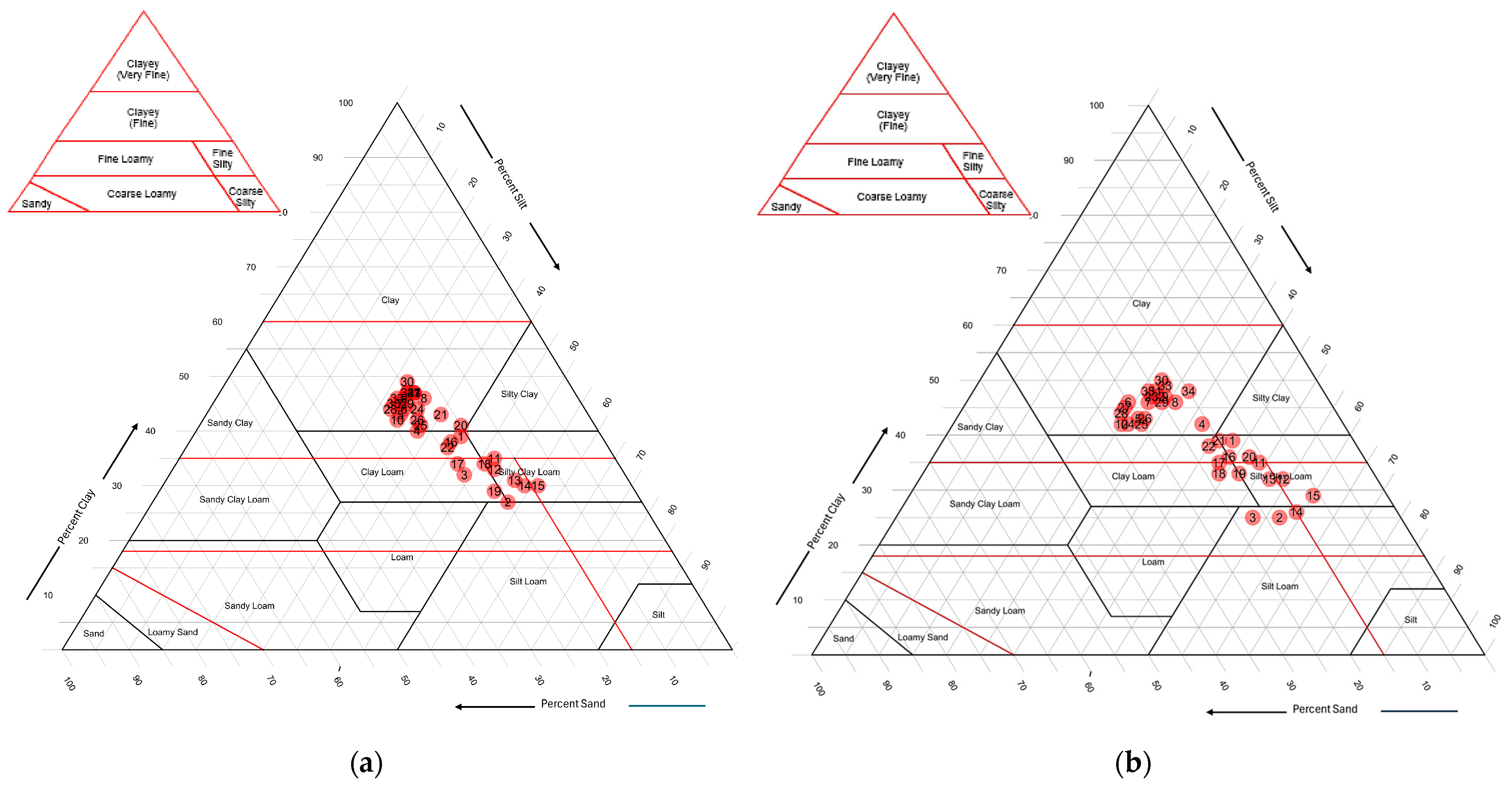

The soil physical properties in the study area for the topsoil (0–30 cm) and integrated soil layer (up to 75 cm) are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively, with the soil texture of the sampling points further illustrated in

Figure 2. The overall consistency between the two plots indicates that the soil texture across the sampling sites is relatively homogeneous, primarily consisting of medium-to-fine-textured soils.

The data collected for this study included a range of measurements: analysis of soil samples, soil penetration resistance data, assessment of the vine root system, measurements of critical grape characteristics in the laboratory, and the calculation of specific soil indicators, as detailed below:

Soil Penetration Resistance Data

Soil penetration resistance was measured to a depth of 100 cm using a hand-held penetrometer equipped with a cone base area of 129 mm

2 and a cone tip angle of 30°. Graphs of penetration resistance versus soil depth were generated using acetate overlays, following the procedure described by Lowery and Morrison [

31].

Root Data

Vine root systems are typically concentrated within the upper 60 cm of the soil profile but may extend to depths of up to 600 cm [

27]. To assess whether the recorded penetration resistance values reflected the effective rooting depth in the study site, four soil trenches were excavated following the method of Bohm [

32]. Trench locations were selected to be representative of the site based on penetration resistance measurements. Each trench measured 2.0 m in length and 1.5 m in depth and was excavated parallel to the vine rows at 30 cm from the vine trunks to expose the root architecture.

Grape Data

A random sample of 200 berries was collected from the 24 vines within each plot and weighed using an electronic balance. The berries were then crushed and filtered for further analysis of juice quality. The pH of the filtrate was measured with a calibrated pH meter, while total acidity and reducing sugars were determined via manual titration. All analyses were performed in accordance with the standards of the International Organization of Vine and Wine [

33], and descriptive statistics of grape characteristics are given in

Table 3. The phenolic content was estimated by partial extraction with hydrochloric acid, following the method of Blouin [

34]. Anthocyanins and the Total Phenolic Index (TPI) were quantified by spectrophotometry at 520 nm and 280 nm, respectively [

35].

Integration of soil indicators

Vine roots exploit with varying efficiency the soil layers where the root sphere is developed, and unfavorable soil conditions of one soil layer can be ameliorated by favorable conditions of another soil layer where vine roots will develop to a greater extent [

10,

11]. To account for the whole soil profile, we adopted a linear combination for integrating soil indicators (

SIint), in each sampling location, within all soil layers above the depth where soil penetration resistance exceeds 2 MPa/cm

2 (Equation (1)) [

31,

32,

36]:

where

is the integrated soil indicator according to penetration resistance,

is the thickness of the soil layer i (cm),

is the value of soil indicator in soil layer i,

i is the soil layer above the soil depth where penetration resistance exceeds 2 MPa/cm

2, and

is the soil depth where penetration resistance exceeds 2 MPa/cm

2.

Each soil layer contributed to the outcome proportionally according to its thickness.

2.1. Methodological Strategy

Our methodological strategy was as follows: First, we evaluated soil data from both the topsoil (TopS) and the integrated soil layer (IntS) across 35 sample sites, while measuring six grape characteristics (a total of 200 berries were sampled from each vine in the sample locations) in the laboratory from the corresponding sites. Second, principal components analysis (PCA) was adopted to identify the inter-relations among 6 selected soil variables. Subsequently, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was used to determine homogenous groups of these samples based on the samples’ scores on the most important components identified from PCA. Then, we constructed interpolated maps and graphs to visualize the results of PCA and HCA to enhance the delineation of management zones in the vineyard. Finally, interpolated maps of the integrated soil layer were used as a background, and proportional symbols representing the mean values of the six grape characteristics were overlaid, highlighting their spatial variability. To further clarify the connection between the soil and grape data, corresponding bar charts were created for each HCA cluster, displaying the mean values of the grape characteristics within each specific cluster. The flowchart of the proposed methodology is given in

Figure 3.

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS v.29.0.2.20. The significance level in all testing hypotheses was predetermined at

a = 0.05 (

p ≤ 0.05). The significance of the resulting factors was assessed by three criteria [

37]: (a) factors with eigenvalue > 1, (b) factors explaining over 60% of total variance; (c) each factor must explain more than 5% of the total variance.

2.2. Assessing the Suitability of the PCA Method’s Application

Initially, we conducted preliminary tests to achieve a data reduction and feature selection step from the initial set of 19 variables using PCA. The components were selected based on the standard Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1). Our pre-defined selection threshold was that the retained components/variables had to be responsible for explaining at least 60% or more of the total cumulative variance in the dataset for the topsoil and integrated soil layer, respectively. To ensure the independence of the final predictors and comply with the assumptions of our subsequent statistical analysis, we performed a secondary check on the variables suggested by the PCA. We then proceeded to remove several variables due to high collinearity (absolute correlation coefficients > 0.8). As a result of this two-step process (PCA followed by collinearity filtering), we ultimately selected six variables for our statistical analysis. These final six variables demonstrated acceptable levels of correlation, with absolute correlation coefficients ranging between 0.3 and 0.8. The final selection of the 6 variables was confirmed by their relevance to key soil functions and plant physiology [

36,

38]: (a) Variables for structural support: Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and silt; (b) Variables for plant nutrition: Total nitrogen (TN) and potassium (K); (c) Variables for the rhizosphere environment: pH and organic carbon (OC).

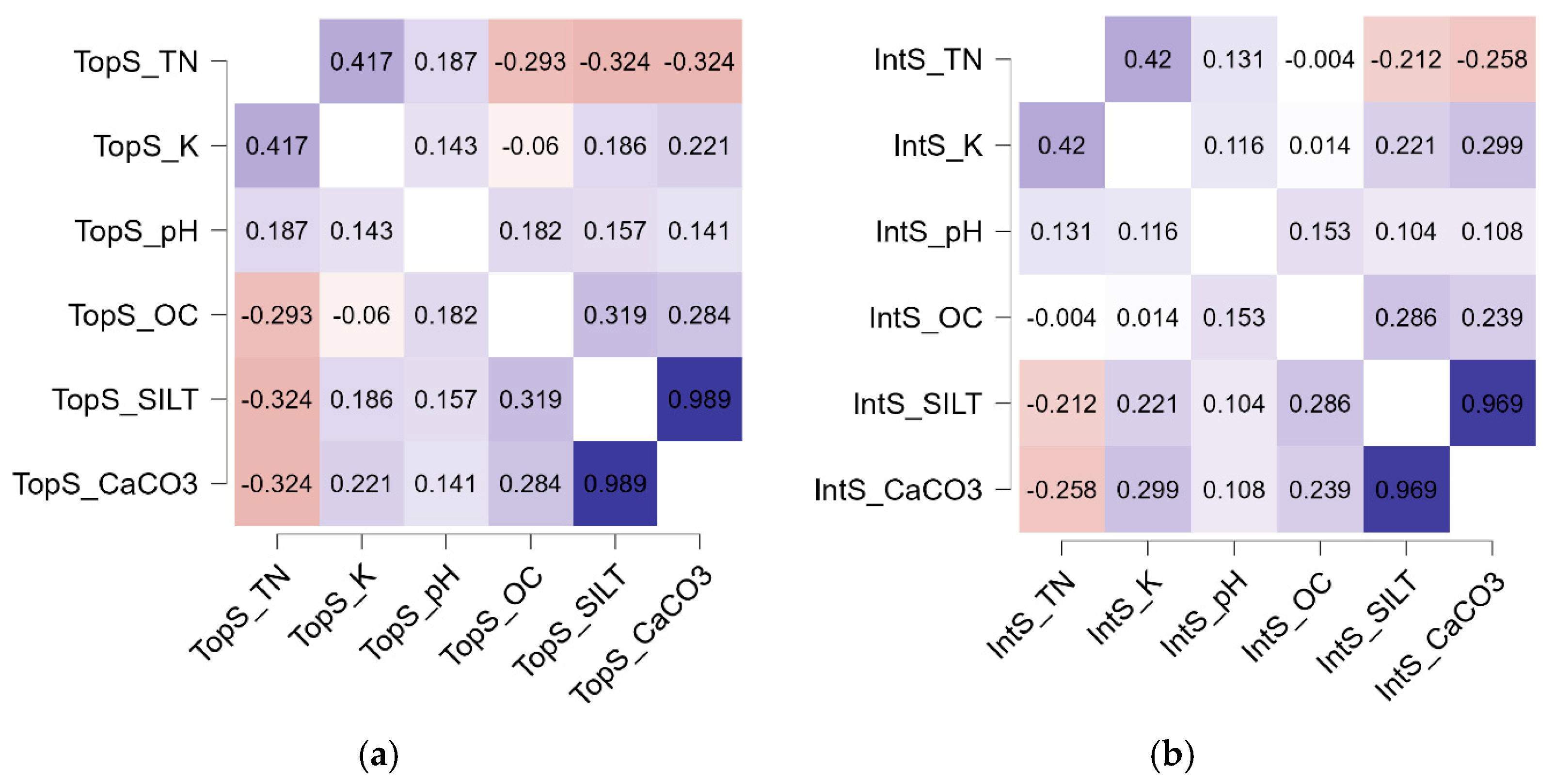

Pearson’s correlation heatmaps were generated for the selected variables in both the topsoil and integrated soil layers (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). This graphical tool serves to visually represent the correlation coefficients between variables, which allows for the rapid identification of potential relationships and the detection of multicollinearity [

37,

39]. Although several variables were initially removed to address redundancy, it was observed that the CaCO

3 and silt variables remain highly collinear. Both were retained in the analysis, however, because they collectively provide a comprehensive measure of soil structural support for the vines. Silt and CaCO

3 are critical for capturing both the physical and chemical dimensions of soil functioning; their combined influence on soil texture, aggregation, porosity, and water retention directly impacts root penetration and nutrient availability. The decision to include both variables, despite their strong correlation, is methodologically sound as it aligns with the core purpose of Principal Component Analysis. PCA is specifically designed to identify the shared variance among a set of correlated variables and condense that information into a smaller, independent set of principal components [

17,

18]. By including both variables, the analysis can more accurately capture the full extent of the underlying factors they represent.

The main suitability conditions for using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) include several key assumptions [

37], all of which are met:

Multiple variables measured on a continuous scale: 6 variables for the soil data and 6 for the grape data, based on a dataset of 35 samples.

A linear relationship among all variables has been confirmed (PCA relies on Pearson correlation coefficients, which assume linearity).

Sampling adequacy: although the dataset includes only 35 samples, the rule of thumb of at least 5 cases per variable is satisfied.

Data suitability for dimensionality reduction: there are sufficient correlations among the variables to justify reducing them to a smaller number of components, as confirmed by Bartlett’s test of sphericity [

17,

18]. Although dimension reduction is not the primary objective of this study, reducing from 6 to 3 variables helps group variables into meaningful categories that capture critical information for plants, such as structural support, nutrition, and root environment.

No significant outliers are present, avoiding disproportionate influence on PCA results.

Therefore, these key conditions are fulfilled, ensuring that PCA can produce valid and stable dimensionality reduction and extract meaningful principal components that represent most of the variance in the data.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Soil properties influence grape traits, but the effect may vary with depth. Topsoil (TopS) provides general surface conditions, while the integrated layer (IntS) represents the root zone where nutrient uptake occurs. To quantify these relationships, we conducted a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) across 35 vineyard sites.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was employed to determine the internal structure of the data for both the topsoil (TopS) and integrated soil layers (IntS). The number of components to be extracted was identified using scree plots and the corresponding Table of Total Variance Explained, generated by SPSS software (v.29.0.2.0). For this exploratory study using soil and plant data, the minimum required sample size was determined based on the guidelines for PCA. As recommended by Hair et al. [

18], a minimum of five samples per variable is necessary to ensure sufficiently stable PCA results. Based on the six input variables, a minimum sample size of 30 (6 × 5) was considered adequate. Our analysis was conducted using 35 samples.

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) was employed to identify homogeneous groups of samples using the samples’ scores on the significant components derived from the PCA. These scores are already in the form of

z-scores. The clustering process was performed using Ward’s minimum variance criterion for clusters’ joining due to its tendency to form groups of comparable sizes with approximately the same number of samples in each group [

17,

18,

19,

40]. The Euclidean distance served as the dissimilarity measure between variables. The statistical significance of the resulting cluster solution was evaluated using the upper-tailed rule [

41].

The contribution of each factor in cluster formation was assessed by examining the magnitude and the statistical significance of the corresponding coefficients of determination

R2 computed from a series of one-way ANOVAs [

20]; within this approach, cluster membership was used as the independent variable and factor scores as the dependents. The value of

R2 indicates the percentage of variance of the examined factor accounted for by the differences among the clusters, and it is equal to the value of the eta squared index (

η2), which is a measure of effect size [

19].

To facilitate the interpretation and identification of clusters, the corresponding results are presented and discussed based on the variables used to structure the three composite factors: structural support, plant nutrition, and root environment (rhizosphere).

2.4. Interpolation Process

Using the Natural Neighbor module from the spatial analyst tools (ArcGIS pro v.3.5), we constructed maps to visualize the geographical extent of each cluster as derived from HCA. The Natural Neighbor tool in ArcGIS is an interpolation method used to create a continuous raster surface from a set of discrete point features. It is particularly useful for irregularly distributed data. Unlike some other methods, the Natural Neighbor tool creates a smooth surface that passes exactly through the input sample points. It does not infer trends beyond the data and avoids creating artificial peaks or valleys. The resulting surface is continuous, making it well-suited for modeling phenomena that vary smoothly, such as elevation or rainfall [

42]. To enhance the delineation of zones based on the HCA results, we used the Natural Breaks symbology method with three classes, which reflect the corresponding clusters. To validate the Natural Neighbor interpolation method and quantify the spatial uncertainty of the generated maps, we employed the Cross-validation Error-Distance Field (CEF) technique. The complete results of this validation, including the detailed error maps, are presented in

Section 3.7.

3. Results

3.1. Variable Groupings as Indicated by PCA

Based on the PCA, three significant factors were extracted from the six variables for both the topsoil (TopS) and integrated soil layers (IntS), explaining 82.3% and 79.4% of the total variance, respectively. The statistical assessment of variable suitability for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) yielded a statistically significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (BTS) for both soil layers (TopS and IntS), which confirmed that the variables were sufficiently correlated for structure detection. This significant result, consistent with our primary objective of data reduction and maximizing explained variance, provided methodological justification to proceed with the analysis. We note that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measures of sampling adequacy were 0.512 for TopS and 0.408 for IntS. However, KMO is generally considered less critical in the context of PCA for data reduction compared to its use in Factor Analysis (FA), where the objective is to identify underlying latent constructs [

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, some researchers use lower KMO cutoff values, such as 0.5 or lower, depending on the case [

43]. The successful variance retention achieved by the PCA validates this methodological choice: the first three principal components retained 82.3% and 73.4% of the total system variance for TopS and IntS, respectively. This high retention rate, alongside the significant BTS results, demonstrates the efficacy of using PCA to condense the dataset while preserving its core variability (

Table 4).

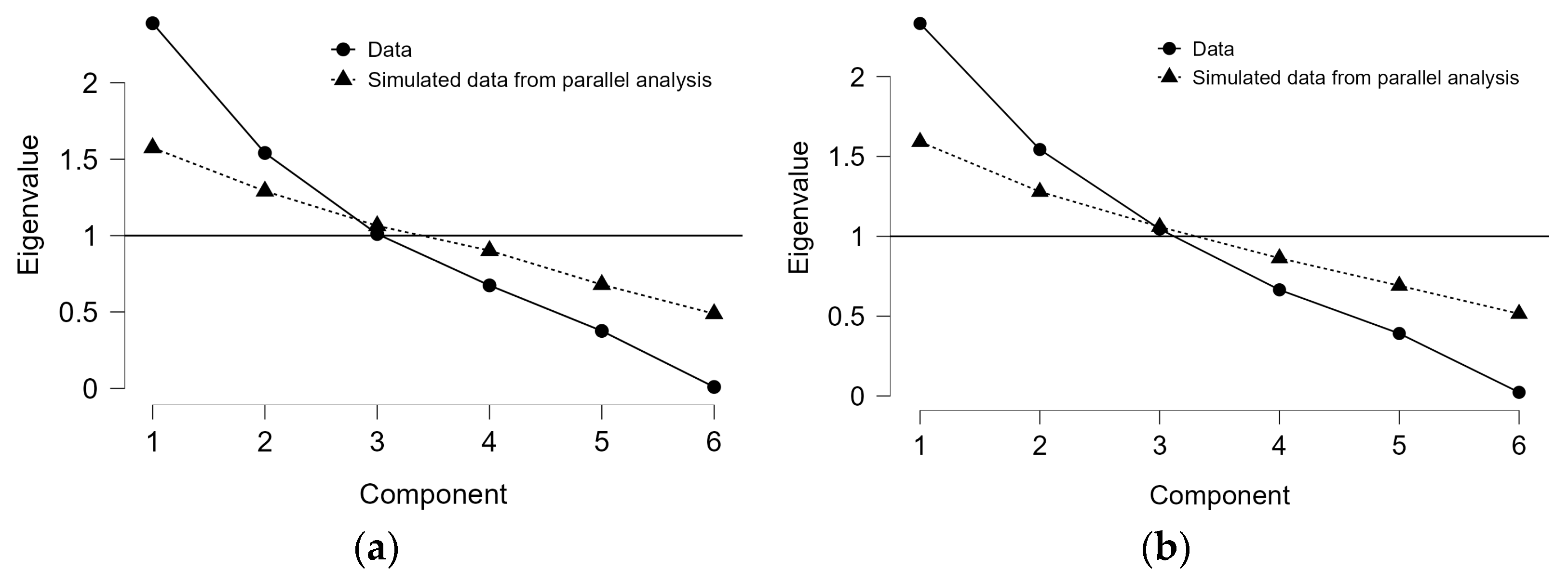

To select the optimum number of components for extraction, scree plots and parallel analysis [

44] were used to confirm the selection (

Figure 6). The inclusion of the first two factors was clear, while the third factor was marginally accepted, despite its real data component eigenvalues being slightly lower than the simulated data mean eigenvalues from the parallel analysis (

Figure 6).

The statistical assessment of variable suitability for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) yielded a statistically significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (BTS) for both soil layers (TopS and IntS), which confirmed that the variables were sufficiently correlated for structure detection. This significant result, consistent with our primary objective of data reduction and maximizing explained variance, provided methodological justification to proceed with the analysis. We note that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measures of sampling adequacy were 0.512 for TopS and 0.408 for IntS. However, KMO is generally considered less critical in the context of PCA for data reduction compared to its use in Factor Analysis (FA), where the objective is to identify underlying latent constructs [

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, some researchers use lower KMO cutoff values, such as 0.5 or lower, depending on the case [

43]. The successful variance retention achieved by the PCA validates this methodological choice: the first three principal components retained 82.3% and 73.4% of the total system variance for TopS and IntS, respectively. This high retention rate, alongside the significant BTS results, demonstrates the efficacy of using PCA to condense the dataset while preserving its core variability.

In TopS, the first factor explained 37.0% of total variance and was mainly structured by calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and silt, which represent the structural support of soil to plants. Similarly, in IntS, the first factor with an eigenvalue of 2.260 explained 35.9% of the total variance. The second factor, with 1.541 and 1.477 for the TopS and IntS, explained 25.8% and 24.0% of total variance and was mainly structured by, respectively, total nitrogen (TN) and potassium (K). The third factor, with 1.010 and 1.025 for the TopS and IntS, explained 19.5% of the total variance for both layers, and it was mainly structured by pH and organic carbon (OC).

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results reveal distinct clustering patterns for both topsoil (TopS) and deeper soil (IntS) layers, indicating a consistent grouping of soil samples based on their physicochemical properties.

3.2. Relationship Assessment Between Soil and Grape Quality Characteristics

To quantitatively assess the relationship between the underlying dimensions of soil characteristics and grape quality, we calculated the Pearson’s

r correlation matrix between the identified soil PCs (FAC1, FAC2, FAC3) and the primary grape quality characteristics component (Grapes_FAC1). The results, including

r and

p-values, are presented in

Table 5.

Only the primary factors (FAC1) for both the topsoil (r = 0.550, p < 0.001) and the integrated soil layer (r = 0.532, p = 0.001) showed a moderate and statistically significant linear association with Grapes_FAC1. The remaining four soil factors (TopS_FAC2, TopS_FAC3, IntS_FAC2, and IntS_FAC3) yielded weak correlation coefficients (r ranging from 0.103 to 0.312) that were not statistically significant (p-values > 0.05). These results indicate that most of the underlying soil variability captured by the second and third factor dimensions has no linear relationship with the primary component of grape quality characteristics.

3.3. Clusters with Similar Soil Characteristics as Indicated by HCA

The HCA was used to identify homogenous groups of samples with similar soil characteristics based on the scores of the three components identified by PCA, and revealed a three-group interpretable and statistically significant clustering of soil samples. While hierarchical cluster analysis lacks a formal, universally applicable stopping rule, a definitive cut-off point must be determined to establish the final cluster solution [

45]. The most robust methodological approach integrates the quantitative data from the Agglomeration Schedule with the visual hierarchy presented in the dendrogram [

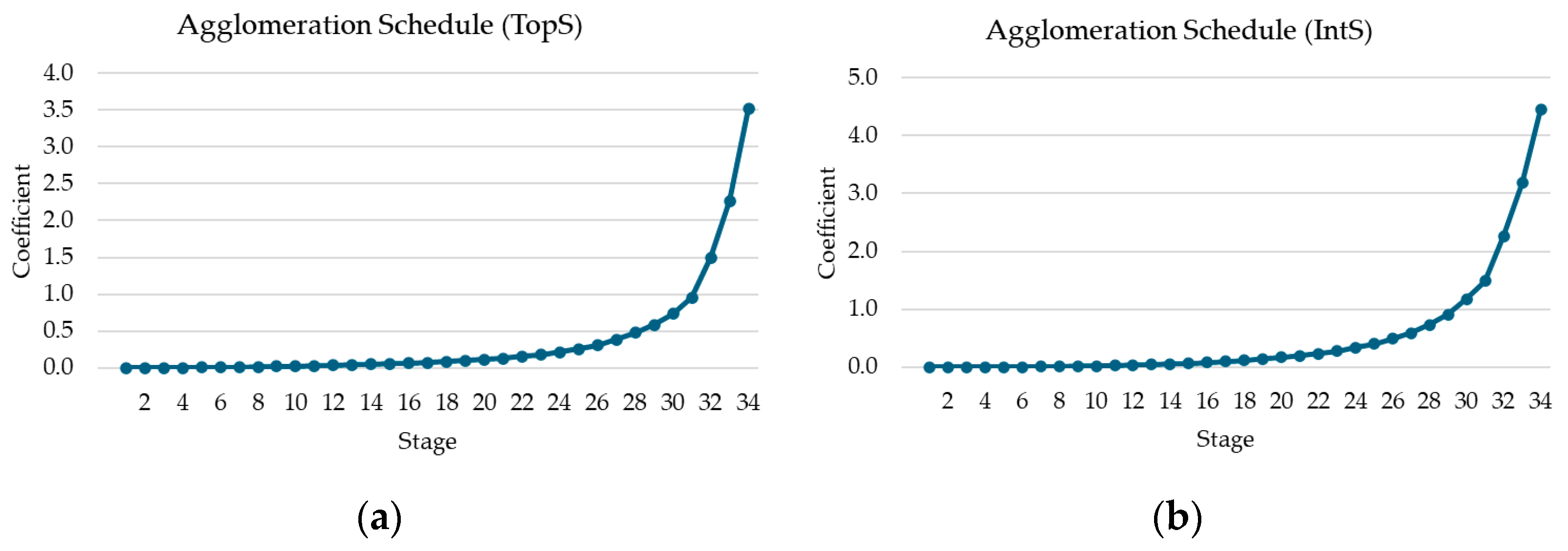

46]. The former, through an analysis of the coefficient values, identifies the stage at which the increase in cluster heterogeneity becomes unacceptably large, a critical “jump” in coefficient values.

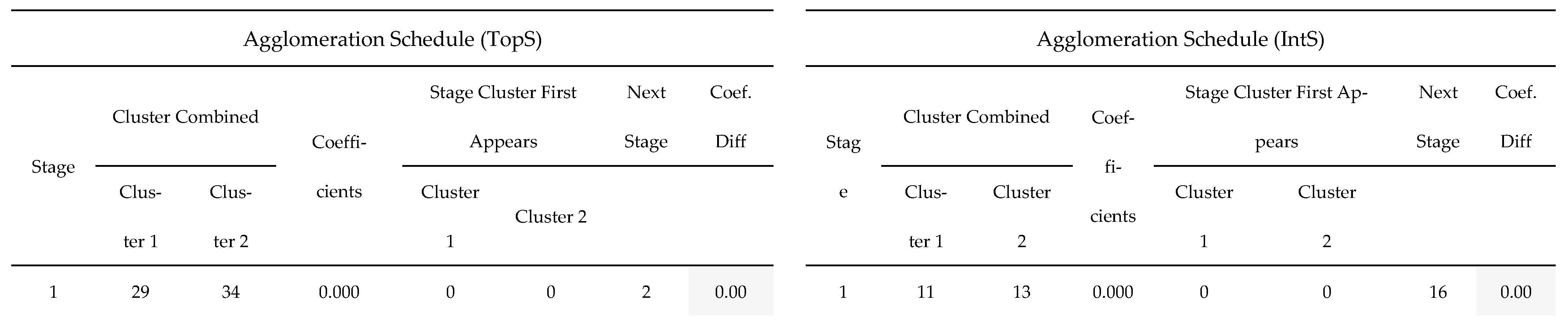

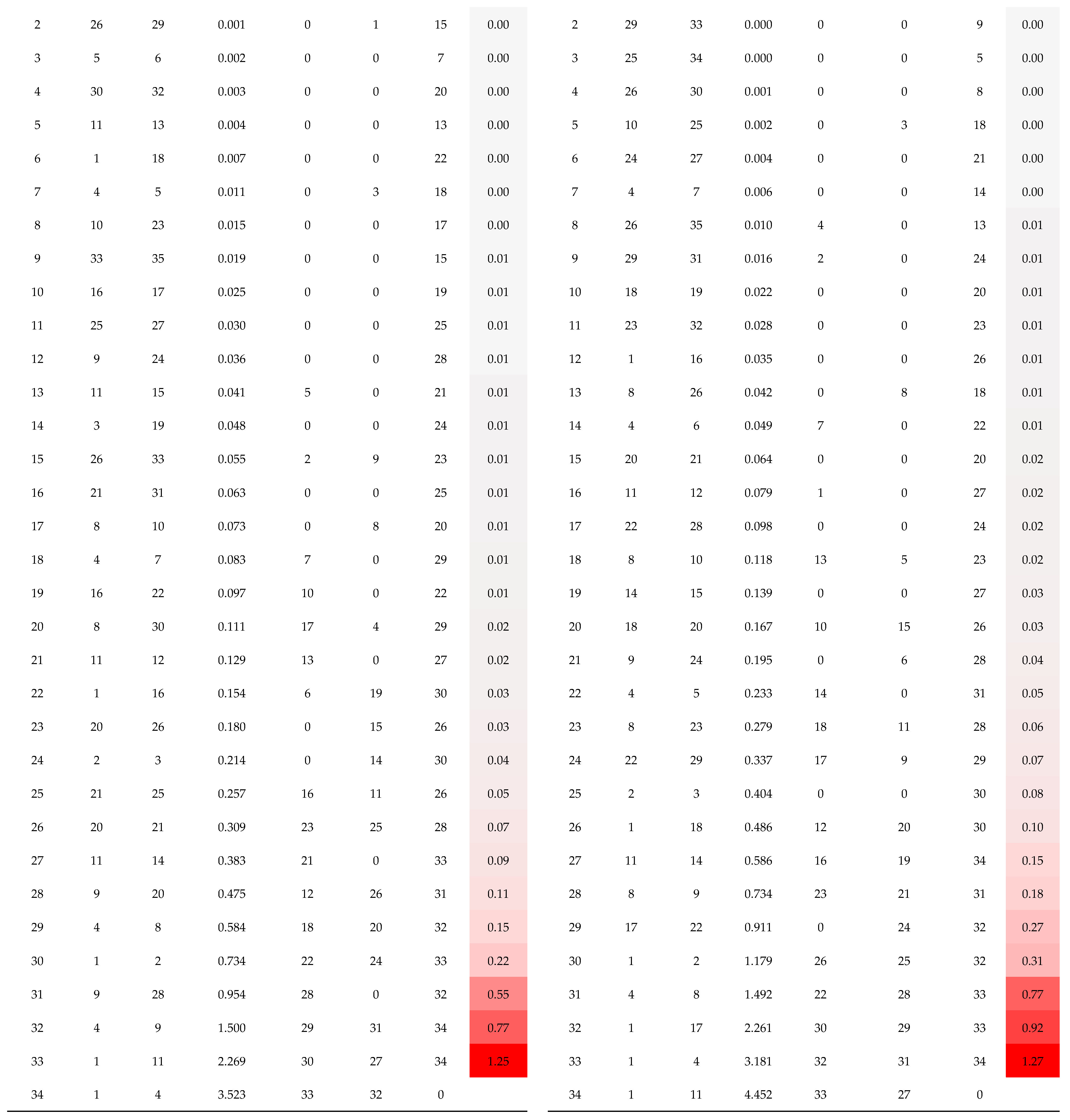

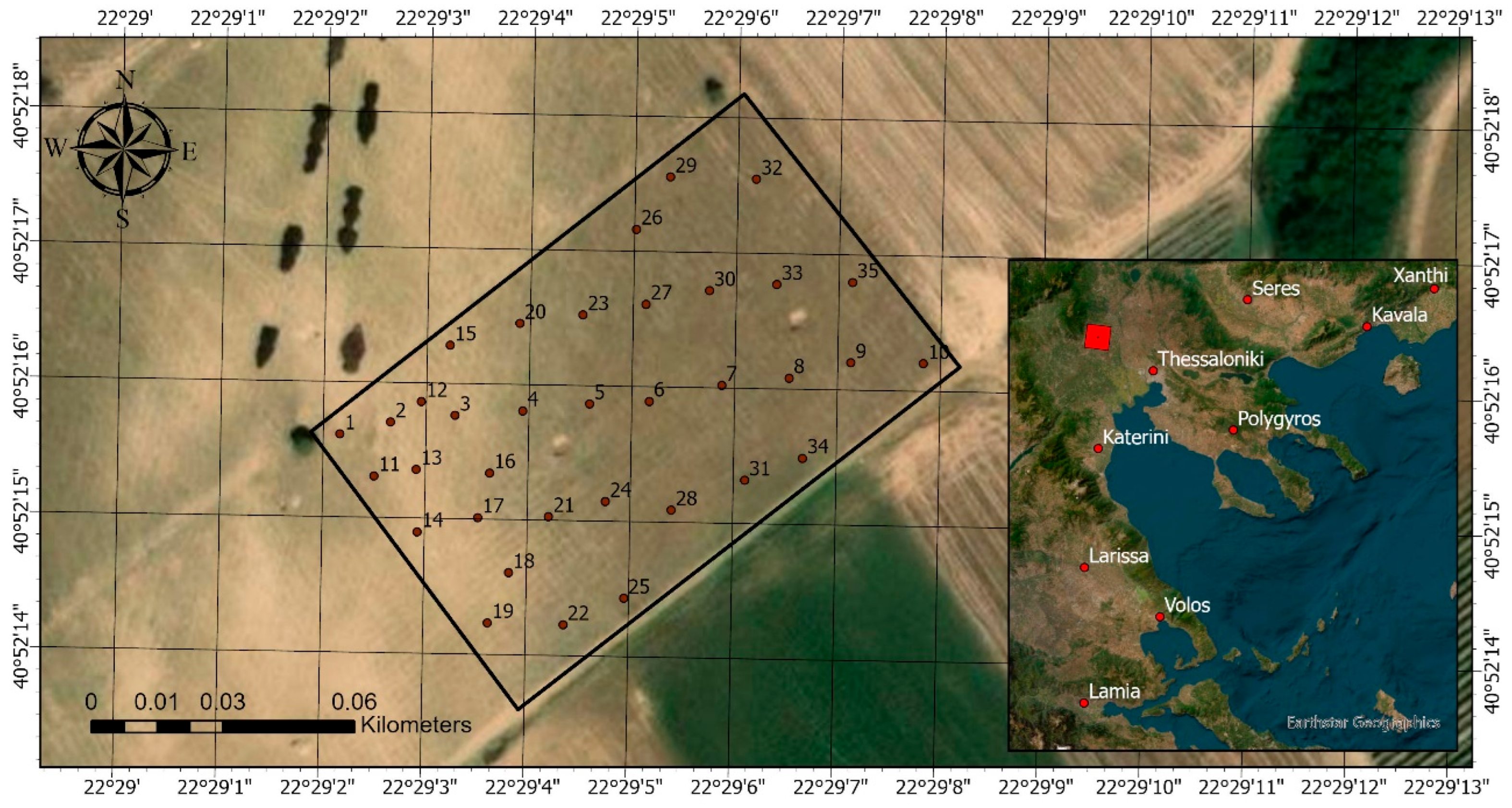

Regarding the procedure we followed to select the optimum number of clusters in HCA, we used the Agglomeration Schedule (in SPSS output for HCA), which serves as the definitive record of the hierarchical clustering process, systematically documenting the combination of cases or clusters at each progressive stage (

Appendix A.1), showing when two clusters being combined are considered too different to form a homogeneous group, when a large increase in coefficient values occurs. In our case study, given the sample size of 35 soil sites, the complete schedule inherently comprises

N stages, detailing every merger until all samples are consolidated into a single cluster. A progressive increase in these coefficient values is expected, as earlier stages combine highly similar entities, while later stages necessarily bridge larger dissimilarities, thereby reflecting the increasing heterogeneity of the resultant clusters. The coefficients listed at each stage quantify the distance between the two clusters being merged. The graph based on the data from the Agglomeration Schedule (

Figure 7) indicates that at approximately stage 31, a large increase in coefficient values is observed, thus indicating that the final three steps of the clustering process should be omitted (three vertical grouping lines in dendrograms for both TopS and IntS). Identifying the optimal number of clusters necessitates a rigorous evaluation of these coefficient values to determine the optimum stopping point of clustering in HCA as a substantial, non-linear increase in the coefficient between two consecutive stages (often visualized as the “elbow” in a Scree plot) [

46]. This “jump” in coefficient values shows that the clusters being merged have become overly distinct, suggesting that the clustering process should be terminated prior to this stage. The resulting partition before this major increase provides the most homogeneous and distinct set of final clusters, maximizing within-group similarity while maintaining meaningful separation between the identified groups (

Figure 7).

Applying this finding to the current analysis, the decision to stop the clustering procedure after stage 31 was based on the Agglomeration Schedule (

Appendix A.1), effectively omitting the final three stages that represent the most heterogeneous combinations. This critical decision from the Agglomeration Schedule is then graphically imposed upon the dendrograms (

Appendix A.2), which is a tree diagram illustrating the sequence and distance of clusters. The optimal cut-off in Dedrograms (

Appendix A.2) is represented by an added (blue dashed) line that vertically dissects the tree. Consistent with the numerical finding from the Agglomeration Schedule, this line is positioned to exclude the last three major vertical lines of the dendrogram, those representing the last three stages, thereby partitioning the data into a set of three clusters that are homogeneous and distinct based on the observed change in the coefficients. For the topsoil (TopS), a total of 8 soil samples (22.9%) were grouped in cluster 1 (C1), 22 (62.9%) in cluster 2 (C2) and 5 (14.3%) in cluster 3 (C3). Similarly, for the integrated soil layer (IntS), a total of 14 soil samples (40.0%) were grouped in cluster 1 (C1), 16 (45.7%) in cluster 2 (C2) and 5 (14.3%) in cluster 3 (C3). The “structural support” was found to make a major contribution to the formation of clusters (

Table 3).

The selection of a 3-cluster solution is also supported through the Explained Proportion within-cluster heterogeneity for both the TopS and IntS clustering models (calculated using JASP 0.95.3). This metric indicates the fraction of total variance within a solution that is uniquely accounted for by each individual cluster. In both the TopS and IntS 5-cluster outputs, a disproportionate amount of heterogeneity is contained within only three of the five clusters, clearly demonstrating diminishing returns beyond k = 3. Specifically for the TopS solution, clusters 1, 2, and 3 collectively explain 86.6% (0.317, 0.191, and 0.350, respectively) of the within-cluster heterogeneity. Conversely, the addition of clusters 4 and 5 accounts for only a marginal 13.4% of the total explained variance (0.142 and 0), despite introducing two additional, complex segments to the model. A similar pattern is evident in the IntS, where clusters 1, 3, and 4 account for 95% of the explained heterogeneity (0.690, 0.169, and 0.091, respectively). This suggests that most of the variance structure inherent in the data is captured by a smaller number of groups. Consequently, selecting k = 3 leads to retaining the most descriptively powerful segments while excluding the statistically minor and often less-defined clusters. This approach ensures the final model maintains the optimal balance between explanatory depth and actionable simplicity.

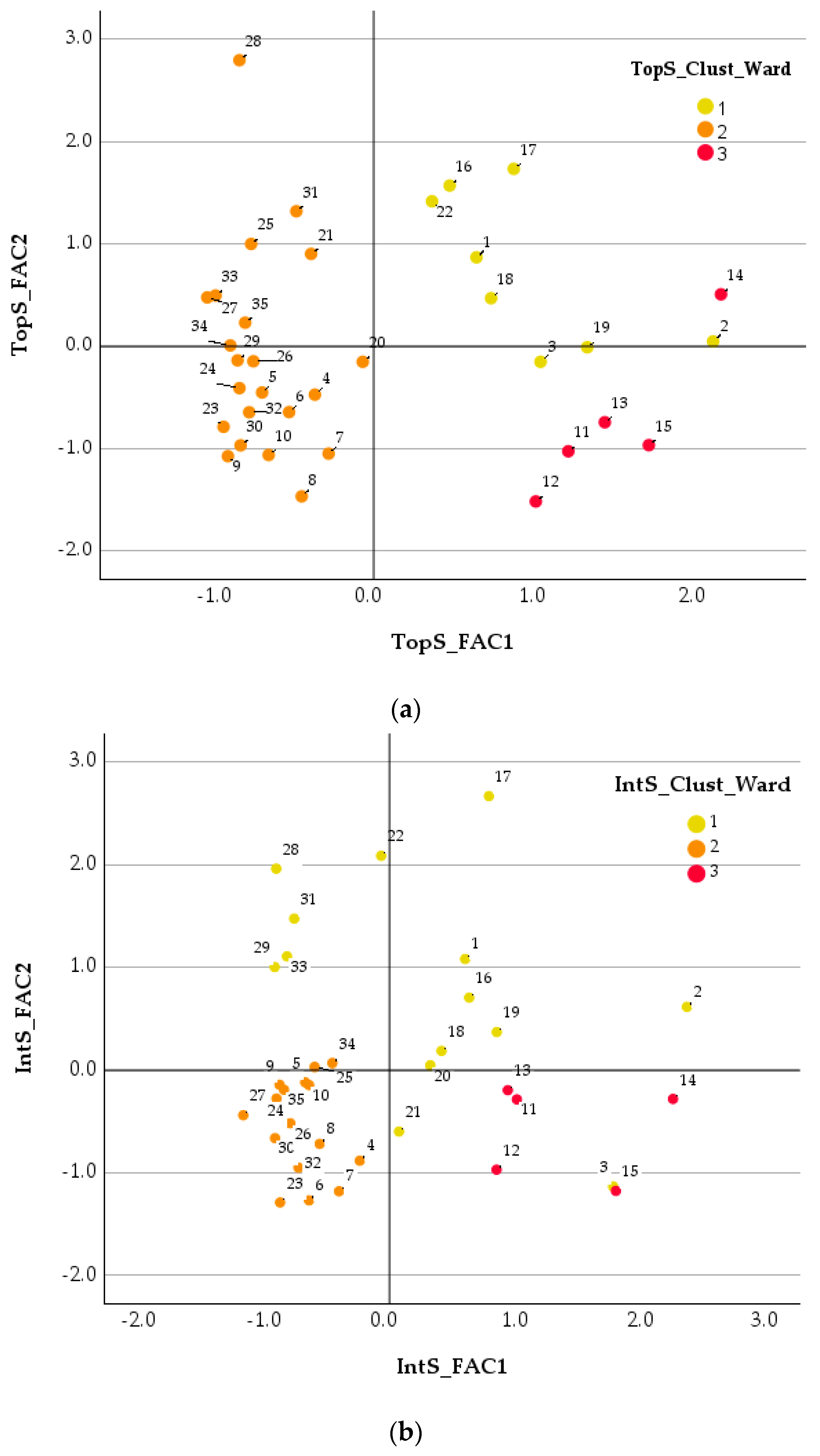

Both soil layers are partitioned into three clusters (1, 2, and 3), with similar overall spatial arrangements on the FAC1-FAC2 plane (

Figure 8). However, a closer look reveals significant differences between the two layers. The relative positions and groupings of individual samples shift from the TopS to the IntS PCA space. This is best exemplified by sample 2, which is an outlier in the TopS analysis but is clearly grouped with Cluster 1 in the IntS analysis. Similarly, sample 14, a member of Cluster 3 in TopS, becomes more isolated in IntS with a much higher FAC1 score. This suggests that the factors driving the major components of variance (FAC1 and FAC2) change with soil depth. The underlying processes influencing soil composition, such as organic matter decomposition, leaching, or parent material weathering, have a differential impact on the samples at various depths. The PCA thus serves as a powerful visualization of the vertical heterogeneity in soil properties, demonstrating that the chemical “fingerprint” of a site varies significantly between the topsoil and the deeper, integrated soil layer.

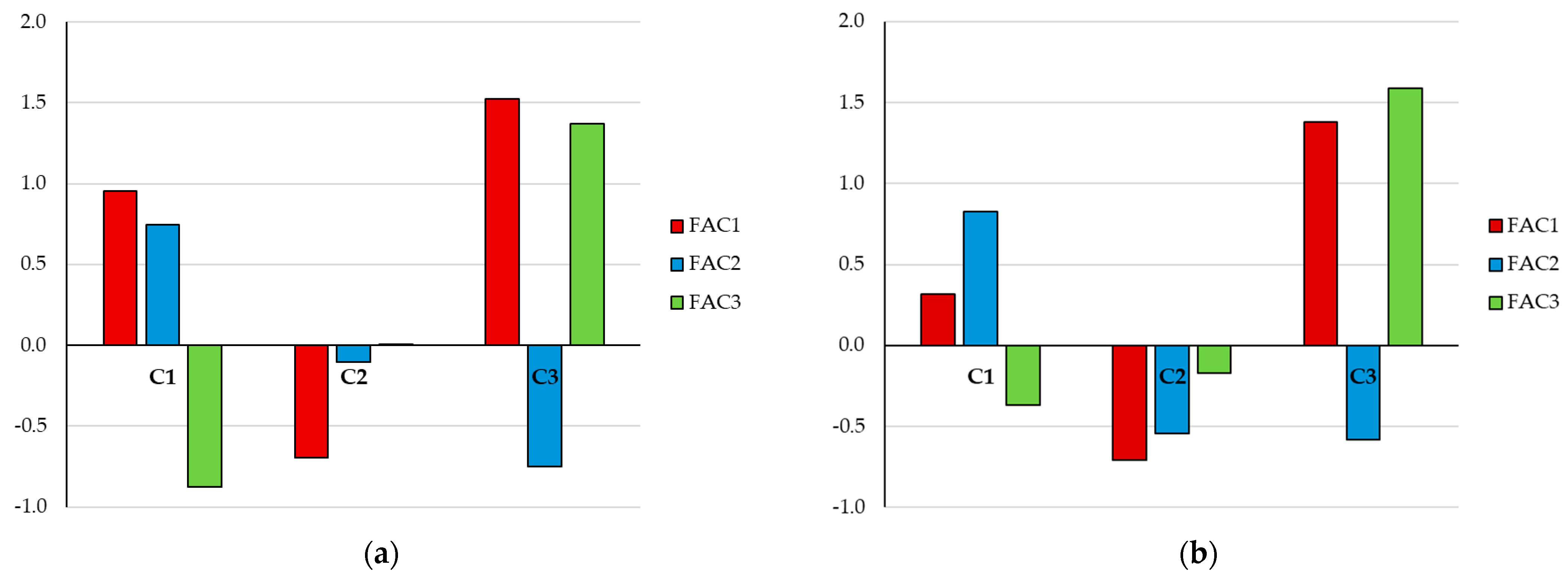

In

Figure 9, the centroid/means of the PCA components (

Table 6) were used to create bars for each HCA cluster for the TopS and IntS soil layers (FAC1: Structural support; FAC2: plant nutrition; FACT3: root environment). The following interpretation can be given:

Regarding the clusters in Topsoil (TopS):

Cluster 1 (C1): This cluster is characterized by high positive values for FAC1 (Structural Support) and FAC2 (Plant Nutrition), but a strong negative value for FAC3 (Root Environment). This suggests that soils in this cluster provide good structural stability and are rich in plant nutrients, but may have less favorable conditions for root growth, possibly due to factors like high compaction or low porosity.

Cluster 2 (C2): This cluster is defined by negative values for all three factors, particularly a strong negative value for FAC1 (Structural Support) and a moderate negative value for FAC2 (Plant Nutrition). This indicates that the soil in this cluster has poor structural integrity and is low in nutrients, making it the least favorable for overall soil health and productivity. The FAC3 (Root Environment) value is near zero, suggesting it is not a defining characteristic for this cluster (near mean).

Cluster 3 (C3): This cluster stands out with the highest positive values for both FAC1 (Structural Support) and FAC3 (Root Environment), and a negative value for FAC2 (Plant Nutrition). This profile suggests that these soils have excellent structural properties and a very favorable root environment, likely due to good aeration and porosity. However, they are deficient in plant nutrients.

Regarding the integrated soil layer (IntS):

Cluster 1 (C1): In contrast to the topsoil, this cluster has a low positive FAC1 (Structural Support) and a high positive FAC2 (Plant Nutrition). Similar to the topsoil, it has a negative FAC3 (Root Environment). This indicates that the deeper soils in this cluster are primarily defined by their high nutrient content, while structural support is less prominent compared to the topsoil. The negative root environment suggests that while nutrient-rich, these layers may be less conducive to deep root penetration.

Cluster 2 (C2): This cluster exhibits a similar pattern to its topsoil counterpart, with negative values for all three factors. The most negative value is again for FAC1 (Structural Support), followed by FAC2 (Plant Nutrition) and FAC3 (Root Environment), which are both moderately negative. This confirms that this cluster represents the poorest soil quality profile, consistent across both depths.

Cluster 3 (C3): This cluster maintains its distinct profile with the highest positive values for FAC1 (Structural Support) and FAC3 (Root Environment), but a negative value for FAC2 (Plant Nutrition). The consistent physical properties across both soil layers indicate that the soils in this cluster are characterized by excellent structural support and a favorable root environment, despite being nutrient-poor.

The analysis based on PCA and HCA results confirms that the three clusters have fundamentally different soil quality profiles. The most significant changes between the topsoil and deeper soil layers are observed in Cluster 1, where the dominant factor shifts from FAC1 (Structural Support) to FAC2 (Plant Nutrition). This suggests that while topsoil is often defined by a balance of structural and nutritional properties, the deeper layers in this cluster are more specifically characterized by their nutrient reserves. The other two clusters, C2 and C3, maintain remarkably consistent profiles across both depths. Cluster 2 consistently represents the poorest quality soils, while Cluster 3 consistently represents soils with superior physical properties (structural support and root environment) but with lower nutrient content.

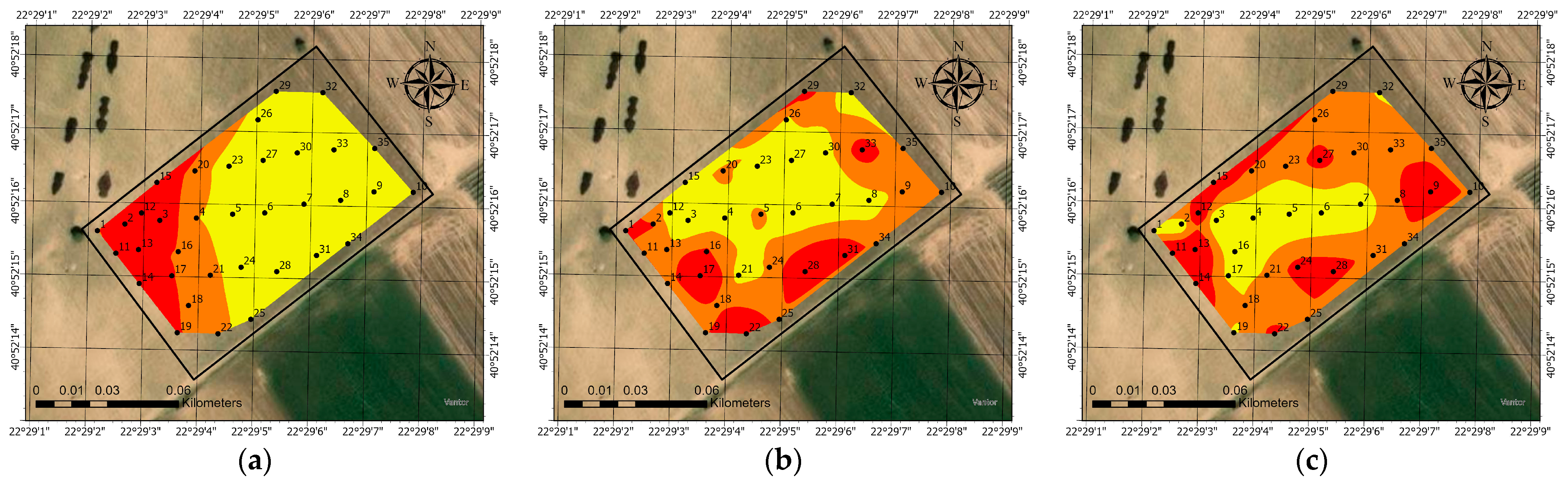

3.4. Interpolation Maps Depicting the PCA Results

The interpolated maps based on the PCA results reveal significant spatial heterogeneity and vertical stratification of soil properties within the study area (

Figure 10). While Kriging is often considered the gold standard for geostatistical interpolation due to its ability to model spatial autocorrelation and provide a measure of prediction uncertainty (variance), in this case we adopted the Natural Neighbor interpolation approach, which offers a good middle ground; Natural Neighbor interpolation finds the closest subset of input samples to an unknown point and applies weights based on the proportionate area of the Voronoi polygons [

42]. A key advantage is that it does not require the user to define a search radius or the number of neighboring points to consider, as it adapts locally to the data’s density and distribution. This method also guarantees that the interpolated values will not exceed the minimum or maximum of the input data, which can be useful for physical properties. As a result, it produces a smooth surface without the need for a variogram and the statistical assumptions required by Kriging, which can be complex to model correctly. The choice of the Natural Neighbor algorithm for interpolation was verified using the Cross-validation Error-Distance Field (CEF) technique, as outlined in

Section 2.4. This validation confirmed its suitability for the current dataset, with full statistical results and error maps detailed in

Section 3.7.

For the Topsoil (TopS):

FAC1 (Structural Support): The map shows a clear east–west gradient. The eastern part of the field exhibits high values (red/orange), indicating strong structural support, while the western part shows low values (blue/purple), suggesting poor structural integrity.

FAC2 (Plant Nutrition): This factor shows a more fragmented pattern. The southern section of the field has higher nutrient levels (red), while the central and northern areas are relatively low (blue), indicating localized nutrient enrichment.

FAC3 (Root Environment): A clear north–south gradient is visible. The northern part of the field is highly favorable for root growth (red/orange), while the southern part is less so (blue), suggesting variations in factors like aeration or porosity.

For the integrated soil layer (IntS):

FAC1 (Structural Support): The pattern is similar to the topsoil, with the eastern side having higher structural support (red) and the western side having lower values (blue). This indicates that the structural properties are consistent with depth.

FAC2 (Plant Nutrition): The pattern here is more uniformly low across the entire field, with most of the area showing low nutrient levels (blue). This suggests that nutrient enrichment, if present, is a localized topsoil phenomenon and does not extend to deeper layers.

FAC3 (Root Environment): The gradient is consistent with the topsoil, with higher values in the north (red) and lower values in the south (blue), reinforcing the finding that conditions for root growth are spatially stratified in a north–south direction throughout the soil profile.

In summary, the maps highlight distinct spatial patterns for each soil property, which are largely maintained from the topsoil to the deeper layer, especially for structural support and root environment. However, the plant nutrition factor (FAC2) shows a significant change, with localized topsoil enrichment disappearing in the deeper soil, underscoring the dynamic nature of nutrient distribution and its reliance on surface processes. This analysis provides a valuable spatial context for understanding the soil’s physical and chemical variability and can be used to inform targeted management practices.

3.5. Delineating Management Zones for Specific Applications

To support specific agronomic applications (e.g., fertilizer management), corresponding management zone maps were constructed. These maps were developed using integrated soil data based on Natural Neighbor interpolation maps, which were derived from interpolating the samples’ principal component scores. The resulting maps utilized the Natural Breaks (Jenks) classification method, grouping the data into three classes. The three maps generated through this process address critical issues regarding: structural support (

Figure 11a), plant nutrition (

Figure 11b), and root environment (

Figure 11c).

The three management zone maps (IntS_FAC1, IntS_FAC2, and IntS_FAC3) are derived from different principal components and are intended for specific, targeted applications in site-specific management (SSM).

Structural Support: This map (

Figure 11a) is based on the first principal component (PC1), which typically captures the largest amount of data variance and correlates strongly with soil physical properties important for structural integrity and water movement, such as the silt index and CaCO

3. Yellow areas identified as having poor structural support (e.g., high silt content) would be considered as having higher susceptibility to compaction for controlled traffic farming (CTF) or avoiding machinery passes during wet periods. These zones can guide variable-rate tillage (VRT), where more intensive or deeper tillage is prescribed only in compacted or hardpan-prone areas, while minimal or no-till practices are applied elsewhere to conserve structure and moisture. Areas with significantly different soil structures require zone-specific adjustments to irrigation rates or the installation of tile drainage to manage waterlogging or infiltration issues.

Plant Nutrition: This map (

Figure 11b) is based on the second principal component (PC2), which represents variables related to soil chemical properties crucial for plant growth, such as the total N and K. The zones of this map can be used as the primary tool for implementing variable-rate nutrient applications. Farmers can use these zones to apply variable-rate fertilizer (VRF). Areas identified as deficient in nutrients (e.g., the yellow zones indicating low scores) must receive higher application rates.

Root Environment: This map (

Figure 11c) is based on the third principal component (PC3), which captures variability that relates to properties that directly affect root growth and function, such as the organic carbon and pH. These management zones focus on optimizing the subsurface conditions for root development, which directly impacts yield potential and drought resilience. Areas showing evidence of a hardpan or restrictive layer may be targeted for deep ripping or subsoiling to break up the layer and allow for deeper root penetration and better water uptake. This map helps fine-tune irrigation strategies by accounting for zone-specific effective rooting depths and water storage capacity. Deeper-rooted zones might receive less frequent, but larger, irrigation events than shallow-rooted zones.

The resulting interpolation maps demonstrated that transforming PCA outputs into spatial layers enabled a more comprehensive understanding of vineyard variability in relation to specific plant functions such as structural support, plant nutrition, and the root environment. By identifying the soil factors most critical to variability and translating them into biologically meaningful principal components, the method established a solid basis for delineating functional management zones for specific applications. Interpolation into continuous surfaces further highlighted areas requiring targeted interventions. Overall, this multivariate spatial framework supports more precise and sustainable vineyard management.

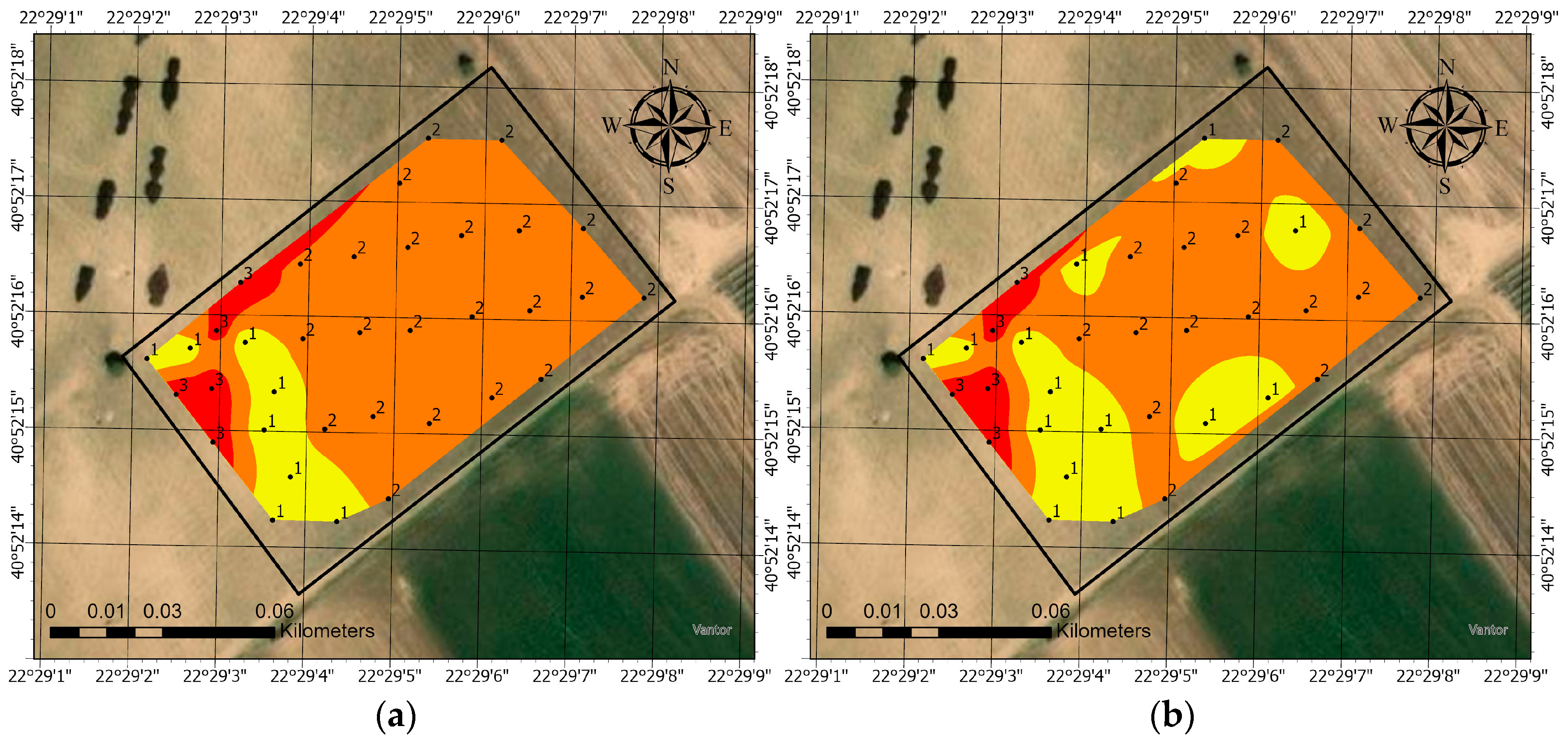

3.6. Interpolation Maps Depicting the HCA Clustering Results

The Natural Neighbor interpolation maps (

Figure 12) show the spatial distribution of soil clusters (labeled 1, 2, and 3) derived from the HCA on the PCA results. The colors likely correspond to these clusters, with yellow, orange, and red representing different groups of soil characteristics.

Cluster 1 (Yellow): This cluster is present in both maps, occupying the central and lower portions of the field. Its presence alongside Cluster 2 suggests a gradual change or a distinct zone with different soil characteristics, possibly related to topography, past land use, or microclimatic conditions.

Cluster 2 (Orange): This is the most dominant cluster in both maps, primarily in the upper and eastern parts of the field. This indicates a relatively uniform group of soil properties across a significant area. The fact that it is the most widespread suggests these characteristics are the most representative of the field’s overall soil profile.

Cluster 3 (Red): This cluster is the least common and is localized to a small area in the western part of the field in both maps. The presence of a distinct, small cluster indicates a unique set of soil properties in this specific location. This could be a “hotspot” for certain soil characteristics, such as higher or lower levels of a particular nutrient, different texture, or altered organic matter content.

A direct comparison of the two interpolation maps reveals a high degree of spatial consistency. The general patterns of Clusters 1, 2, and 3 are very similar in both the topsoil (TopS) and the integrated soil (IntS) layers. This suggests that the primary factors driving the soil variability are not just superficial but extend to a deeper profile. The soil properties that define these clusters are not confined to the top few centimeters but are characteristic of the entire sampled soil column. This indicates that the soil profile is relatively homogeneous in its overall zonation. The similar distribution of clusters also suggests that the agricultural practices or natural processes that have shaped the soil characteristics have affected both the surface and the deeper layers in a consistent manner. This is a crucial finding for land management, as it implies that a change in one layer is likely reflected in the other.

The interpolated maps derived from the HCA clustering results (

Figure 12) indicate that the field exhibits vertically consistent yet spatially heterogeneous soil properties, which are important for the delineation of management zones in precision viticulture. Although the general spatial pattern is coherent across layers, minor variations are observed in the boundaries and extent of the clusters. Notably, the integrated soil layer reveals a higher level of spatial detail compared to the individual layers. This finding suggests that the integrated layer may provide a more representative and potentially more stable characterization of key soil properties across the entire profile, rather than reflecting only surface conditions.

Figure 13 displays a series of maps showing the spatial variation in different grape characteristics and their values as proportional symbols within the vineyard plot, with cluster zones derived from a Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) for the integrated soil layer. We selected the integrated soil layer as the background because its soil profile provides a higher level of detail. The black dots and associated numbers (proportional symbols map) represent individual measurement points of each grape characteristic within the plot.

In

Figure 13, the maps on the left show the zones created by the Natural Neighbor interpolation on the HCA clustering results for the integrated (IntS) soil layer. In these maps, the numbers indicate the value of a variable, and the size of the dot corresponds to that value. The bar chart on the right displays the mean values for each grape characteristic within the corresponding cluster areas.

The mapping of the selected grape characteristics across the vineyard reveals significant spatial variability (grape characteristics compared to HCA clusters). This heterogeneity is consistent across all measured parameters, and no clear patterns can be identified, indicating that environmental factors such as soil type, water availability, sun exposure, or micro-topography are not uniform and are influencing grape development. The spatial mapping of selected grape characteristics compared to Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) clusters reveals significant variability across the vineyard. This heterogeneity is consistent across all measured parameters, and the lack of clear patterns suggests that non-uniform environmental factors, such as soil type, water availability, sun exposure, or micro-topography, are influencing grape development.

However, when considering the mean values for each grape characteristic within the corresponding cluster areas, we can see they follow a distinct pattern: (a) the mean values from the topsoil and integrated layers are similar; and (b) the HCA clustering groups align with the grouping of the grape characteristic mean values. Therefore, this analysis shows that the HCA clustering successfully identifies distinct soil zones that directly correspond to specific grape characteristics and that it can be used for the delineation of management zones in the context of precision viticulture.

These thematic maps present a visual overview of the spatial heterogeneity of the key grape quality parameters within the vineyard. Therefore, this approach, which integrates geospatial data (sample points) with HCA clustering on PCA samples’ scores along with the grape characteristics, could be considered as an effective method to provide information for delineating management zones in a precision viticulture context.

3.7. Validation of the Natural Neighbor Interpolation Results Using the Cross-Validation Error-Distance Fields Technique

Since Natural Neighbor (NN) interpolation is a deterministic method that relies on local geometric properties and does not produce an intrinsic variance model for prediction uncertainty, a specialized validation approach was necessary to quantify the spatial reliability of the interpolated surface. The Cross-Validation Error-Distance Field technique was employed to map local interpolation uncertainty across the field [

47]. This cross-validation error field method aligns with the characteristics of Natural Neighbor (NN) interpolation [

48]. The process calculates errors (

e) at each data point, like calculating cross-validation MAE. However, instead of simply averaging these errors, the technique assumes they are spatially autocorrelated and uses interpolation to generate an estimated absolute error field. This use of localized errors is highly advantageous because it is consistent with NN interpolation’s properties, allowing the error estimates to reflect local changes in the phenomenon’s spatial autocorrelation, resulting in lower estimated errors in more predictable areas and higher errors in less predictable areas.

The resulting absolute prediction error

for each sample point is normalized by its Nearest Neighbor distance

to yield the Rate of Error (

). This rate acts as a measure of the error per unit of local data scarcity. The discrete

values and the

distances can be interpolated across the study area to produce continuous surfaces for the Rate of Error Field (

) and the Distance Field (

). The final Cross-Validation Error-Distance Field (

) is then generated by multiplying these two continuous surfaces (

). This integrated field provides a robust, spatially continuous estimate of uncertainty, effectively capturing heterogeneity influenced by both local variation in the spatial autocorrelation and the density and distribution of the original sampling network. However, while the cross-validation error field indicates where interpolation errors are higher, it cannot be used as a measure of uncertainty for Natural Neighbor interpolations, as interpolation is conducted using all the data available, and given that NN is an exact interpolator, we anticipate having zero error and therefore zero uncertainty at the data cells [

47].

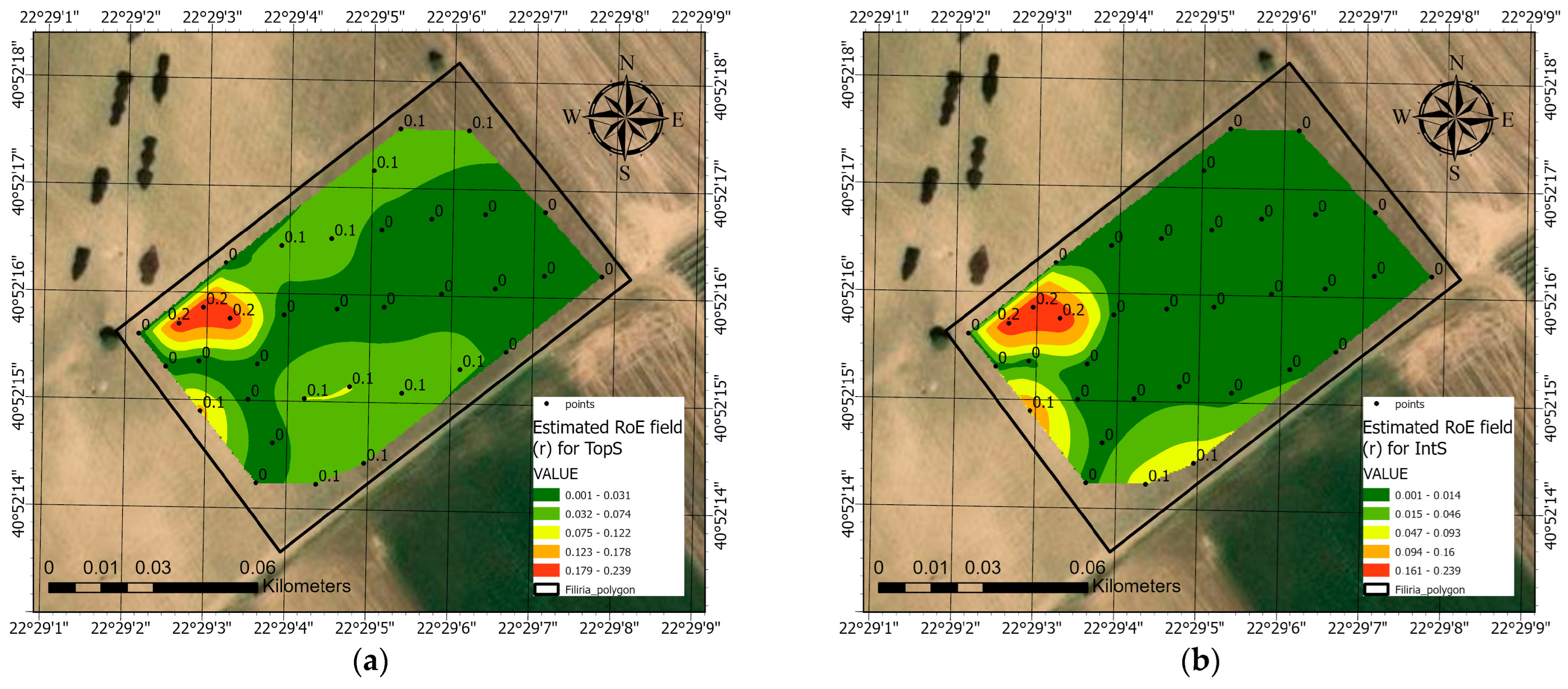

In our case study, the Rate of Error (

was calculated for all soil sampling points for the two soil layers, having as input variable the HCA clustering results to demonstrate the uncertainty associated with the implementation of NN interpolation (

Figure 14). The topsoil layer (TopS) yielded a higher mean rate of error (

) compared to the integrated (IntS) layer (

). This indicates that, on average, the prediction error for the TopS HCA clusters increases more rapidly with distance to the nearest data point. This difference reflects the greater spatial variability and lower spatial continuity of the TopS (HCA) clusters, likely due to increased heterogeneity caused by surface processes. Conversely, the lower rate for the integrated (IntS) layer suggests its clusters are more stable and predictable across the sampled domain. The final Error-Distance Field (

) maps were constructed (

) to visually depict the prediction uncertainty of the NN interpolation (

Figure 15).

Both rate-of-error maps for the topsoil (TopS) and integrated soil layer (IntS) exhibit an area with the maximum () located in the upper-left and central-left sections of the study area. However, the comparison between the two Rate of Error maps reveals a clear distinction in the spatial behavior and heterogeneity of the HCA clusters across the two soil layers. The TopS layer consistently displays a higher prevalence of sample points with elevated values, which is quantitatively supported by its greater mean rate of error ( = 0.0515) compared to the IntS layer (= 0.0283). Since normalizes the classification error by the Nearest Neighbor distance , a higher rate signifies that the prediction error increases more rapidly as the distance from the nearest sample point grows. This steep increase in error sensitivity points to higher spatial heterogeneity and lower spatial continuity in the TopS, likely driven by active, near-surface processes that cause greater cluster variability over short distances. Conversely, the lower overall for the IntS suggests its cluster boundaries are more stable and predictable, indicating that the deeper soil properties are less susceptible to rapid change and, therefore, require less dense sampling to maintain interpolation accuracy.

The observed co-location of the maximal Rate of Error () in both the TopS and IntS horizons is a critical finding that validates the utility of the Rate of Error methodology. Since the nearest neighbor distance () is constant across both layers at that location, the shared maximum implies the absolute cross-validation error () is maximally high for both interpolations. This combined predictive failure could be indicative of an unsampled spatial discontinuity that affects the properties of both soil layers. Far from indicating a flaw in the Natural Neighbor method, this high could be considered as a geospatial indication, pinpointing the location where the current sampling network is most inadequate for resolving the sharpest spatial transition in the study area. Also, this area where the occurs could identify the primary target for future, higher-density sampling.

4. Discussion

4.1. Potentials of Adopting a Multivariate Spatial Approach for Management Zone Delineation

The combined use of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) with geospatial tools provides a rigorous framework for examining spatial variability in vineyards. Precision viticulture requires more than data collection; it depends on methods that can integrate diverse information and reveal functional relationships. Here, PCA was applied not simply for dimensionality reduction but to identify the soil variables most influential to variability and to group them into principal components (PCs) with clear agronomic meaning. These PCs capture key dimensions of vineyard productivity, such as structural support, plant nutrition, and the root environment. Focusing on the integrated soil layer (IntS), which corresponds to the active root zone, ensured that the analysis remained biologically relevant to vine performance. Component scores were interpolated to produce maps for each principal component, serving as the basis for management zone delineation. HCA was then applied to the most informative PCs to classify sampling points into homogeneous clusters, which were further interpolated into continuous surfaces. This process highlighted areas requiring closer management attention.

The results, particularly the lack of significance for four out of the six measured soil factor correlations, provide quantitative evidence that the direct, linear influence of secondary soil variability on fruit characteristics is attenuated in this perennial agricultural system. This statistical non-finding can best be explained by the physiological buffering mechanism characteristic of established perennial crops. The development of robust root systems and the accumulation of significant plant reserves allow the grapevines to effectively compensate for micro-scale or short-term variation in soil nutrient status (represented by the non-significant FAC2 and FAC3 components). Consequently, while the most fundamental dimension of soil quality (FAC1) remains critical, factors beyond the measured soil parameters, such as physiological variables or microclimatic fluctuations, become the dominant drivers of final fruit quality, thereby decoupling the secondary soil variability from the primary crop response dimension.

Overall, this multivariate spatial framework moves beyond single-variable mapping and supports a more holistic delineation of functional management zones, offering practical value for site-specific decisions in vineyard management. The visualization of both PCA component scores and HCA cluster assignments through interpolated maps is critical for the practical implementation of site-specific management strategies. Interpolation maps based on the individual PCA scores for each component (e.g., the ‘Plant Nutrition’ component or the ‘Root Environment’ component) are crucial for understanding the specific nature and spatial gradient of the underlying constraints or resources. These individual maps provide prescriptive insights, clearly showing where, for instance, nutrients are deficient or where soil structural integrity is weak, guiding targeted input applications (e.g., variable rate fertilization or deep ripping). In contrast, the interpolation map based on the HCA clustering results provides a synthesized, comprehensive overview. This thematic cluster map incorporates all significant soil variability into discrete, actionable management zones, where each zone represents a unique combination of the underlying soil properties (as defined by the PCA components). By constructing both types of maps, managers are equipped with two distinct, yet complementary, layers of information: the specific cause-and-effect variability (PCA scores) and the overall field partition into actionable areas requiring attention (HCA clusters). The final overlay of grape characteristics on the HCA map from the IntS layer further validates this delineation, providing a complete spatial picture for data-driven vineyard optimization.

4.2. The Importance of Exploring Soil Characteristics in the Integrated Soil Layer

Exploring the group of soil characteristics at deeper depth is important for several reasons:

Understanding Soil Functionality: Soil is a multi-layered system. The topsoil (TopS) is the upper soil layer, while the integrated soil (IntS) is the integrated soil layer where most biological activity, nutrient cycling, and interaction with plant roots occur. Analyzing also the integrated soil (IntS), which includes the topsoil but also extends deeper, provides a more comprehensive view of the entire root zone. Understanding the characteristics of both layers is essential for grasping the full functionality of the soil ecosystem.

Informed Agricultural Management: Different depths have different implications for management decisions. For example:

TopS Analysis: Provides critical information for short-term management, such as the application of fertilizers, pesticides, and liming, which are directly incorporated into the top layer. It also reflects recent or ongoing agricultural impacts.

IntS Analysis: Offers a long-term perspective. It is crucial for understanding nutrient reserves, water holding capacity, and potential for subsoil compaction or chemical limitations that affect deep-rooted crops. Managing for the IntS layer ensures long-term sustainability and productivity of the field.

Detecting Soil Stratification and Pedogenesis: The comparison of topsoil (TopS) and integrated soil data (IntS) can reveal whether the soil profile is stratified. If the cluster patterns were significantly different between the two maps, it would indicate distinct layering, possibly due to erosion, deposition, or specific pedogenic (soil-forming) processes. The high similarity observed here, however, suggests a relatively uniform vertical profile, which can simplify some management decisions but also highlights the need to address any issues across the entire depth.

Interpretation of Spatial Variability: Performing interpolation on the results from PCA and HCA, adopting a spatial approach, provides a more robust and complete picture of spatial variability. This can lead to more accurate delineation of management zones for precision agriculture, ensuring that inputs are applied spatially where they are needed.

In conclusion, the spatial approach provides a more complete overview of a field with spatially distinct but vertically consistent soil properties. The differences between the TopS and IntS cluster maps underscore the importance of considering the integrated soil layer and not only the topsoil for better understanding soil variability. This approach provides a holistic view of the soil profile, which is critical for developing effective, sustainable, and site-specific agricultural strategies and management zones.

4.3. Implications of Current Findings for Research and Practice

Standard practice and low budget often involve surface-only soil sampling, but the findings of this work indicate that it might be misleading. The active root zone, defined as the layer where most roots are located, reflects the complex processes occurring in the rhizosphere, such as nutrient mineralization and water uptake. This integrated layer also smooths out short-term fluctuations in moisture and nutrients, providing a more stable and meaningful metric. Including these integrated/active-layer variables in predictive models for grapevine traits and yield is crucial. These variables more effectively capture the actual supply of water and nutrients available to the vine, leading to a better model fit and more reliable predictions. For field protocols, the ideal root-zone depth should be determined empirically for each site. This can be done by identifying the depth that contains approximately 80–90% of the fine roots or by mapping the main wetting front under drip irrigation lines.

The data from the integrated root zone should be the primary basis for making management decisions related to fertilization, irrigation, and nutrient application. This is because these metrics are directly aligned with the actual conditions of resource uptake by the plant. Combining Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) can further inform these decisions by identifying patterns and relationships within the soil data. Plotting these clusters on maps can create a visual representation of soil variability, facilitating more precise, site-specific management strategies.

4.4. Boundaries and Future Avenues

Regarding soil sampling protocols, while a focus on the active root zone generally offers superior correlation with plant performance, the ideal sampling depth is inherently site-specific and context dependent. Topsoil data remain highly relevant in specific situations, such as young vineyards with shallow roots, areas susceptible to erosion, or sites where surface-level processes like salinization are dominant. Future viticultural studies should adapt their sampling strategy based on site-specific factors, including rooting depth, the irrigation method, and soil texture, to strengthen the correlation between soil properties and plant performance. The methodological choice between active versus top-soil sampling thus constitutes a critical design decision that dictates the relevance of the resulting management zones.

In terms of Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the groupings of variables and the interpretation of the derived principal components are expected to vary significantly across different study areas because they are fundamentally dependent on the unique correlation structure of the local soil dataset. This variability is not a flaw, but a natural boundary of the data-driven approach. When the objective is highly specific (e.g., delineating only nutrient management zones), and the key nutrient variables do not co-vary strongly, this PCA-based methodology should be viewed as one of several available tools. Alternative analytical strategies would then be necessary to effectively partition the management areas based on that narrow objective. Furthermore, for datasets exhibiting strong non-linear associations, techniques such as Kernel PCA or Isomap offer clear avenues to expand upon the methodology by robustly handling these complex relationships, thereby broadening the framework’s applicability.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study, derived from a specific viticultural zone in Northern Greece, may limit the direct generalizability of the delineated soil–plant relationships and management zones to other regions. Future research should therefore focus on validating these methodologies across diverse viticultural contexts with varying soil types, climates, and grape varieties to establish broader applicability.

The exploration of soil properties at deeper depths, particularly within the integrated soil layer, is not only important but essential for a comprehensive understanding of a field’s soil ecosystem. By analyzing both the topsoil and integrated soil layers, we gain a multi-dimensional perspective that is crucial for effective agricultural management. While topsoil analysis is vital for short-term decisions like fertilizer application, the integrated layer provides a long-term view of factors like nutrient reserves and the potential for a subsoil restrictive layer.

The conclusions regarding the analysis of the integrated soil layer using multivariate statistical methods and interpolation techniques are as follows:

By comparing both topsoil and integrated soil layer characteristics, the proposed methodology provides valuable information for understanding the vertically complex soil heterogeneity.

Analyzing the integrated soil layer offers a long-term perspective on nutrient reserves, water holding capacity, and potential for a subsoil restrictive layer, which is crucial for ensuring the field’s long-term sustainability and productivity.

A comparative analysis of soil clusters derived from the topsoil and the integrated layer can provide critical insights into soil stratification and pedogenesis.

By applying spatial interpolation to the results of Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis, this approach provides a more robust and complete picture of spatial variability based on the soil variables included.

HCA clustering (on PCA results) successfully identifies distinct soil zones that directly correspond to specific grape characteristics, making it a valuable tool for the delineation of management zones in precision viticulture.

The novel holistic approach adopted in this study, encompassing both multivariate data analysis methods and spatial analysis, is critical for delineating management zones in the context of precision viticulture. It ensures that agricultural strategies are not only site-specific but also account for the entire root zone, leading to more sustainable and productive outcomes.