Abstract

The exploitation of natural products as lead compounds continues to serve as a vital strategy for the discovery of novel fungicidal agents. This work designed and synthesized a series of carbamate derivatives based on the natural product physostigmine and commercial carbamate fungicides. The title compounds were synthesized from readily available aromatic aldehydes via green Curtius rearrangement. The antifungal activities of those compounds were evaluated in vitro against eight phytopathogenic fungi. Many of the carbamate compounds exhibited good fungicidal activities. Among those molecules, compounds 3a9, 3b1, 3b2 and 3b12 outperformed the potency of the positive control azoxystrobin against certain fungi. Moreover, compounds 3b2, 3b3, and 3b12 showed outstanding and broad-spectrum in vitro antifungal activities against seven fungi with an inhibition rate of over 70% at 50 μg/mL. The preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) investigations demonstrated that N-aryl carbamates bearing a chlorine atom(s) or two bromine atoms on the di-substituted phenyl ring showed superior antifungal potency. This work might lay the foundation for investigating natural-source-based green fungicides, which exhibited great potential as novel antifungal lead compounds.

1. Introduction

Plant diseases, caused by phytopathogenic fungi, lead to substantial crop yield losses and can even result in complete crop failure [1,2,3]. These pathogens infect a wide range of crops, including grains, vegetables, and fruits, damaging various plant tissues [4]. Furthermore, some fungi produce toxins that pose a significant threat to human health [5]. Currently, chemical fungicides remain crucial for crop protection, significantly reducing losses from plant diseases and ensuring crop yield and quality [6]. However, reliance on traditional chemical control can lead to negative impacts, including environmental residue issues and the development of fungal resistance due to the long-term use of single-site inhibitors [7]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to discover novel fungicides with high efficiency, environmental compatibility, and broad-spectrum activity to overcome the limitations of existing agrochemicals.

Natural products, known for their chemical diversity, potent biological activities, environmental compatibility (e.g., facile degradation, low residue and non-target selectivity), and suitability as scaffolds for structural optimization, serve as vital sources for pesticide discovery [8,9,10]. As such, they are considered crucial precursors or lead compounds for developing new pesticides [11,12].

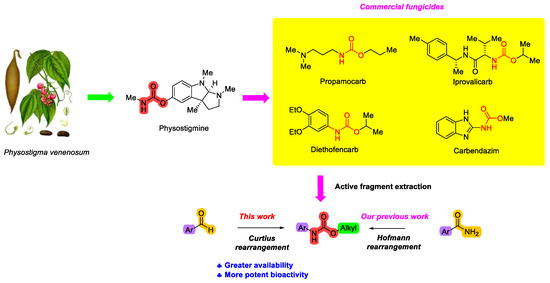

Physostigmine, a carbamate plant alkaloid isolated from Physostigma venenosum, possesses diverse biological activities, including insecticidal and medicinal properties [13,14]. Its structure has inspired the development of commercial carbamate pesticides [15] (Figure 1). The carbamate moiety is a key pharmacophore in many fungicides, often exhibiting broad-spectrum activities by targeting thio-containing enzymes in phytopathogenic fungi [16]. In addition, carbamate fungicides are generally considered to have a reduced environmental impact because they hydrolyze rapidly in the field, resulting in minimal residue [17]. This combination of efficacy and favorable environmental profile makes carbamates one of the most important classes of commercial fungicides. Several novel carbamate fungicides have been developed and commercialized in recent years, such as Pyribencarb [18], Triclopyricarb [19], Picarbutrazox [20], and Tolprocarb [21] (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Design strategy of target compounds.

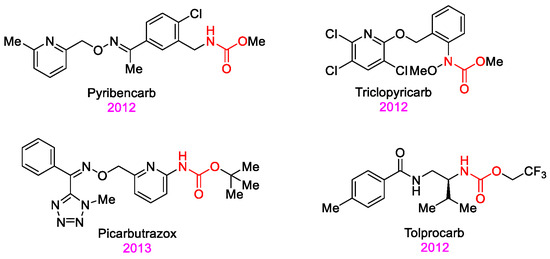

Figure 2.

Commercialized carbamate fungicides since the 2010s.

The carbamate skeleton is a privileged structure in agrochemical discovery [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, conventional synthetic routes to carbamates often involve hazardous reagents, cumbersome procedures, and are not environmentally benign [31]. In response, we recently developed a green and unified method for the oxidation of amides and aldehydes using an oxone-KBr-NaN3 system, generating key intermediates (N-halo amides and acyl azides) that undergo Hofmann or Curtius rearrangements to isocyanates, which are subsequently trapped by alcohols to yield carbamates [32]. In our previous work, we applied the Hofmann rearrangement variant to synthesize carbamate derivatives with promising antifungal activities [33]. Building on these results, we herein report the design and synthesis of a new series of carbamate compounds via the green Curtius rearrangement of readily available aldehydes (Scheme 1). Their antifungal activities were evaluated against eight plant pathogenic fungi in vitro, and the structure-activity relationships were investigated. This work provides valuable insights for developing promising carbamate-based lead compounds as prospective fungicides (Figure 1).

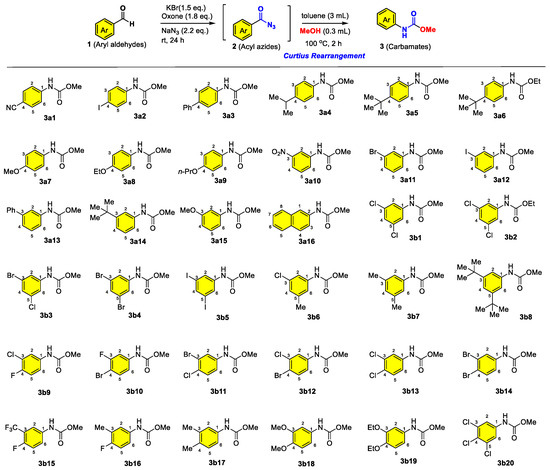

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of the target molecules.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Information

The commercially available chemical reagents and solvents were purchased from Bidepharm (Shanghai, China) and used directly without further purification. Proton and Carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on Bruker AVIII 400 MHz spectrometers (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany). 1H NMR and 13C NMR chemical shifts are reported in ppm (δ) with the solvent (chloroform-d) peaks utilized as the internal standard (7.26 ppm for 1H and 77.16 ppm for 13C). Data are documented as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, bs = broad singlet), coupling constants (Hz), and integration. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained using a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL instrument (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) via electron spray ionization (ESI).

2.2. Synthetic Procedures

General Synthetic Procedure for Carbamates 3: Aromatic aldehydes (1.0 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile (5 mL) and water (5 mL). Potassium bromide (0.2 mmol), sodium azide (1.5 mmol), and Oxone® (2.0 mmol) were added sequentially at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2–4 h (monitored by TLC). Upon completion, the resulting acyl azide intermediate was heated to 60–70 °C for 1–2 h to facilitate the Curtius rearrangement. The corresponding alcohol (methanol or ethanol, 5 mL) was then added, and the mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h. After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 10:1) to afford the pure carbamate products 3.

Carbamates 3 were synthesized in one-pot two-step reactions according to our previous report [32]. The title compounds 3a1–3a3, 3a5, 3a7, 3a10–3a12, 3a15–3a16, 3b1, 3b4, 3b9–3b10, 3b15–3b18 were known compounds and were already in store in our laboratory [32]. The remaining compounds were synthesized following the general procedure above. Twelve of these compounds (3a4, 3a6, 3a8, 3a13–3a14, 3b2–3b3, 3b6–3b8, 3b13, 3b19) were known and their corresponding references are listed. All new compounds were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS. Known compounds showed spectral data consistent with the literature values. The characterization data of newly prepared compounds are listed as follows:

3a4 [34]. 40.5 mg, 70% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.30 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.19–7.14 (2H, d, H-3, H-5), 6.68 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.77 (3H, s, OMe), 2.87 (1H, sep, J = 6.9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.23 (6H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, CH(CH3)2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.3 (C=O), 144.2 (C-4), 135.5 (C-1), 126.9 (C-2, C-6), 118.9 (C-3, C-5), 52.3 (OMe), 33.5 (CH(CH3)2), 24.1 (CH(CH3)2).

3a6 [35]. 47 mg, 71% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31 (4H, s, H-2, H-3, H-5, H-6), 6.66 (1H, bs, N-H), 4.23 (2H, q, J = 7.1 Hz, OCH2CH3), 1.43 (9H, s, C(CH3)3), 1.30 (3H, t, J = 7.1 Hz, OCH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.8 (C=O), 146.3 (C-1), 135.3 (C-4), 125.9 (C-2, C-6), 118.6 (C-3, C-5), 61.2 (OCH2), 34.3 (C(CH3)3), 31.4 (C(CH3)3), 14.6 (OCH2CH3).

3a8 [36]. 34.5 mg, 59% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-2, H-6), 6.86–6.81 (2H, m, H-3, H-5), 6.56 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.99 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, OCH2CH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OMe), 1.39 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, OCH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.4 (C-4), 154.5 (C=O), 130.8 (C-1), 120.7 (C-2, C-6), 114.9 (C-3, C-5), 63.7 (OCH2CH3), 52.3 (OMe), 14.9 (OCH2CH3).

3a9. Methyl (4-propoxyphenyl)carbamate. 35 mg, 56% yield; white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, H-2, H-6), 6.87–6.81 (2H, m, H-3, H-5), 6.59 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.88 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, OCH2), 3.75 (3H, s, OMe), 1.83–1.74 (2H, m, OCH2CH2), 1.02 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, OCH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.6 (C-4), 154.5 (C=O), 130.7 (C-1), 120.8 (C-2, C-6), 114.9 (C-3, C-5), 69.8 (OCH2), 52.3 (OMe), 22.6 (OCH2CH2), 10.5 (OCH2CH2CH3). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C11H16O3N+ [M+H]+ 210.1125, found 210.1124.

3a13 [37]. 52 mg, 76% yield; yellowish solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.66 (1H, s, H-2), 7.62–7.57 (2H, m, H-2″, H-6″), 7.44 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, H-3″, H-5″), 7.40–7.34 (3H, m, H-4, H-6, H-4″), 7.33–7.29 (1H, m, H-5), 6.86 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.80 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.2 (C=O), 142.2 (C-1), 140.7 (C-1″), 138.3 (C-3), 129.5 (C-3″, C-5″), 128.8 (C-5, C-4″), 127.5 (C-2″, C-6″), 127.2 (C-6), 122.4 (C-2), 117.5 (C-4), 52.4 (OMe).

3a14 [34]. 47 mg, 75% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.46–7.37 (1H, m, H-5), 7.28–7.22 (2H, m, H-2, H-6), 7.15–7.09 (1H, m, H-4), 6.80 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe), 1.32 (9H, s, C(CH3)3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.3 (C=O), 152.3 (C-3), 137.6 (C-1), 128.7 (C-2, C-5), 120.6 (C-6), 116.0 (C-4), 52.3 (OMe), 34.8 (C(CH3)3), 31.3 (C(CH3)3).

3b2 [38]. 55 mg, 79% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34 (2H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.03 (1H, t, J = 1.8 Hz, H-4), 6.74 (1H, bs, N-H), 4.23 (2H, q, J = 7.1 Hz, OCH2CH3), 1.32 (3H, t, J = 7.1 Hz, OCH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.1 (C=O), 139.9 (C-1), 135.3 (C-3, C-5), 123.3 (C-2, C-6), 116.8 (C-4), 61.8 (OCH2CH3), 14.5 (OCH2CH3).

3b3 [39]. 60 mg, 76% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45 (1H, t, J = 1.8 Hz, H-2), 7.39 (1H, t, J = 2.1 Hz, H-6), 7.19 (1H, t, J = 1.8 Hz, H-4), 6.86 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.6 (C=O), 139.9 (C-1), 135.5 (C-3), 126.2 (C-5), 122.9 (C-4), 119.6 (C-6), 117.3 (C-2), 52.8 (OMe).

3b5. Methyl (3,5-diiodophenyl)carbamate. 81 mg, 67% yield; white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.98 (2H, d, J = 1.4 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.74 (1H, t, J = 1.4 Hz, H-4), 6.58 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.4 (C=O), 140.1 (C-3, C-5), 139.8 (C-1), 126.5 (C-4), 94.6 (C-2, C-6), 52.8 (OMe). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C8H8O2NI2+ [M+H]+ 403.8639, found 403.8632.

3b6 [39]. 60 mg, 72% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.27 (1H, s, H-2), 7.04 (1H, s, H-4), 6.85 (1H, s, H-6), 6.83 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.75 (3H, s, OMe), 2.26 (3H, s, CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.9 (C=O), 140.5 (C-1), 138.8 (C-3), 134.4 (C-6), 124.2 (C-4), 117.4 (C-5), 115.9 (C-2), 52.5 (OMe), 21.3 (CH3).

3b7 [40]. 39 mg, 73% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02 (2H, s, H-2, H-6), 6.73 (1H, s, H-4), 6.61 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe), 2.28 (6H, s, 3-CH3, 5-CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.1 (C=O), 138.8 (C-3, C-5), 137.7 (C-1), 125.2 (C-2, C-6), 116.5 (C-4), 52.3 (OMe), 21.4 (3-CH3, 5-CH3).

3b8 [41]. 46.5 mg, 59% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (2H, d, J = 4.2 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.15 (1H, t, J = 1.7 Hz, H-4), 6.75 (1h, bs, N-H), 3.77 (3H, s, OMe), 1.32 (18H, s, 3-C(CH3)3, 5-C(CH3)3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.3 (C=O), 151.7 (C-3, C-5), 137.2 (C-1), 117.7 (C-2, C-6), 113.2 (C-4), 52.3 (OMe), 34.9 (3-C(CH3)3, 5-C(CH3)3), 31.4 (3-C(CH3)3, 5-C(CH3)3).

3b11. Methyl (3-bromo-4-chlorophenyl)carbamate. 63 mg, 80% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77–7.71 (1H, m, H-2), 7.34 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-5), 7.27 (1H, dd, J = 8.7 and 2.4 Hz, H-6), 6.79 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.7 (C=O), 137.4 (C-1), 130.4 (C-5), 128.6 (C-6), 123.4 (C-4), 122.6 (C-2), 118.6 (C-3), 52.7 (OMe). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C8H8O2NClBr+ [M+H]+ 263.9422, found 263.9422.

3b12. Methyl (4-bromo-3-chlorophenyl)carbamate. 64 mg, 81% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (1H, d, J = 2.6 Hz, H-2), 7.50 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-5), 7.14 (1H, dd, J = 8.7 and 2.6 Hz, H-6), 6.74 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.6 (C=O), 138.1 (C-1), 134.9 (C-5), 133.8 (C-3), 120.2 (C-2), 118.1 (C-6), 115.8 (C-4), 52.7 (OMe). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C8H8O2NClBr+ [M+H]+ 263.9422, found 263.9418.

3b13 [42]. 53.5 mg, 81% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (1H, d, J = 2.5 Hz, H-2), 7.34 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-5), 7.20 (1H, dd, J = 8.7 and 2.5 Hz, H-6), 6.73 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.7 (C=O), 137.4 (C-1), 132.9 (C-3), 130.6 (C-5), 126.7 (C-6), 120.3 (C-4), 117.9 (C-2), 52.7 (OMe).

3b14. Methyl (3,4-dibromophenyl)carbamate. 64.5 mg, 70% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.75 (1H, s, H-2), 7.50 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-5), 7.20 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-6), 6.71 (1H, bs, N-H), 3.78 (3H, s, OMe). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.6 (C=O), 138.0 (C-1), 133.7 (C-4), 125.0 (C-5), 123.3 (C-6), 118.7 (C-3), 118.2 (C-2), 52.7 (OMe). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C8H8O2NBr2+ [M+H]+ 307.8917, found 307.8922.

3b19 [34]. 37 mg, 51% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.23–7.08 (1H, m, H-5), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H-6), 6.73 (1H, dd, J = 8.6 and 2.5 Hz, H-2), 6.59 (1H, bs, N-H), 4.06 (4H, dq, J = 10.3 and 7.0 Hz, 3-OCH2CH3, 4-OCH2CH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OMe), 1.43 (6H, dt, J = 8.3 and 7.0 Hz, 3-OCH2CH3, 4-OCH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.3 (C=O), 149.1 (C-4), 144.9 (C-3), 131.6 (C-1), 114.2 (C-6), 110.7 (C-5), 105.5 (C-2), 65.1 (4-OCH2), 64.5 (3-OCH2), 52.3 (OMe), 14.9 (4-OCH2CH3), 14.7 (3-OCH2CH3).

3b20. Methyl (3,4,5-trichlorophenyl)carbamate. 48 mg, 63% yield; colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.64 (2H, s, H-2, H-6), 3.77 (3H, s, OMe), NH (not observed). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 154.4 (C=O), 139.1 (C-1), 133.6 (C-3, C-5), 123.5 (C-4), 117.9 (C-2, C-6), 51.5 (OMe). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C8H7O2NCl3+ [M+H]+ 253.9537, found 253.9545.

2.3. Bioassays

The in vitro antifungal activity of the desired compounds against eight plant pathogenic fungi was measured by the mycelial growth inhibition method [33]. The assay was performed against the following fungi: Botrytis cinerea, Magnaporthe oryzae, Pythium aphanidermatum, Fusarium graminearum, Colletotrichum destructivum, Valsa mali, Colletotrichum siamense, and Fusarium oxysporum. Briefly, compounds were dissolved in DMSO to create stock solutions, which were incorporated into Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium to achieve a final concentration of 50 μg/mL for preliminary screening. The final DMSO concentration in the medium was 0.5% (v/v). Mycelial disks (5 mm diameter) from the edge of a freshly growing fungal colony were inoculated at the center of the compound-amended PDA plates. Plates inoculated with DMSO (0.5% in PDA) served as the negative control, and plates containing the commercial fungicide azoxystrobin at 50 μg/mL served as the positive control. All plates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark until the mycelial growth in the negative control plates nearly covered the entire plate surface. The diameter of the fungal colony was measured, and the percentage inhibition of mycelial growth was calculated using the formula: Inhibition (%) = [(C − T)/C] × 100, where C is the average diameter of fungal growth in the negative control, and T is the average diameter of fungal growth in the treatment. Each treatment was performed in triplicate.

For the active compounds, the median effective concentration (EC50) was determined. A series of concentrations (e.g., 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125 μg/mL) of the test compounds was prepared in PDA, and the bioassay was conducted as described above. The EC50 values and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated using SPSS 22.0 software (Probit analysis). The detailed experimental procedure is described in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Chemistry

In this work, two sets of novel carbamate derivatives, which were prepared from readily and/or commercially available aldehydes, were designed and synthesized via green oxidation of aldehydes and subsequent Curtius rearrangement. The synthetic routes and chemical structures of the target compounds are presented in Scheme 1. The starting material, aromatic aldehydes 1, are easily prepared or readily available from commercial sources. Upon treatment of our oxone-KBr-NaN3 system, the corresponding acyl azides 2 were generated from aromatic aldehydes via a green and sustainable approach, enabling the subsequent heat-prompted Curtius rearrangement and capture with alcohols (methanol or ethanol), which led to the synthesis of the target compounds 3 characterized with the carbamate motif. Two series of structural diversity-guided target compounds were secured and characterized through 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS analyses. The corresponding data are presented in the manuscript.

3.2. In Vitro Antifungal Activity

The in vitro fungicidal potential of all target derivatives was systematically assessed against eight plant pathogenic fungi by the mycelial growth inhibition method. Preliminary evaluations were carried out at a concentration of 50 μg/mL with the commercialized broad-spectrum fungicide azoxystrobin as a positive control. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Preliminary in vitro antifungal activity of compounds against eight fungi at 50 μg/mL.

Key findings from the preliminary screening are summarized as follows:

Broad-Spectrum Activity: Compounds 3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b11, and 3b12 exhibited notable broad-spectrum activity, showing high inhibition rates (>70–80%) against most of the eight fungi tested.

Activity against Specific Fungi:

Against B. cinerea, 14 compounds showed >60% inhibition, with five compounds (3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b11, 3b12) exceeding 80% inhibition, outperforming azoxystrobin (54.4%). Against M. oryzae, 13 compounds showed >60% inhibition; compounds 3b1, 3b3, and 3b12 were particularly active (>80%). Against P. aphanidermatum, seven compounds (3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b11, 3b12, 3b13, 3b14) showed >80% inhibition, significantly higher than azoxystrobin (56.4%). Against F. graminearum, six compounds (3b2, 3b3, 3b11, 3b12, 3b13, 3b14) demonstrated remarkable activity (>80%), with 3b3 and 3b13 achieving 98.4% and 94.1% inhibition, respectively. Against C. destructivum, compound 3a9 was the most active (>80% inhibition), and ten compounds showed >60% inhibition. Against V. mali, compounds 3b2, 3b3, and 3b11 showed >80% inhibition. Against C. siamense, seven compounds showed >80% inhibition, with 3b11 and 3b12 being the most potent (90.7% and 97.9%, respectively). Against F. oxysporum, seven compounds showed >70% inhibition, with 3b2, 3b3, and 3b12 exceeding 80%. In summary, the screening identified several potent compounds, with 3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b11, and 3b12 showing particularly promising broad-spectrum activity.

Based on the preliminary screening results, the EC50 values of the most active compounds (showing >80% inhibition at 50 μg/mL) were determined against the eight fungi (Table 2).

Table 2.

EC50 values (μg/mL) of selected compounds against eight fungi in vitro.

The EC50 results revealed the following key points. Several compounds demonstrated potency superior or comparable to azoxystrobin against specific fungi. Against B. cinerea, compounds 3b1 (EC50 = 12.94 μg/mL) and 3b2 (17.21 μg/mL) were more potent than azoxystrobin (18.06 μg/mL). Against F. graminearum, compound 3b2 (EC50 = 9.53 μg/mL) was more effective than azoxystrobin (10.35 μg/mL). Against C. destructivum, compound 3a9 (EC50 = 16.70 μg/mL) was significantly more active than azoxystrobin (30.41 μg/mL). Against C. siamense, multiple compounds, particularly 3b12 (EC50 = 15.48 μg/mL), showed higher potency than azoxystrobin (22.12 μg/mL). While the title compounds showed good activity against V. mali (EC50 = 17.04–21.83 μg/mL for top compounds), their activity was lower than that of azoxystrobin (4.70 μg/mL). Compounds 3b2, 3b3, and 3b12 emerged as the most promising broad-spectrum candidates, exhibiting significant activity against seven of the eight fungi.

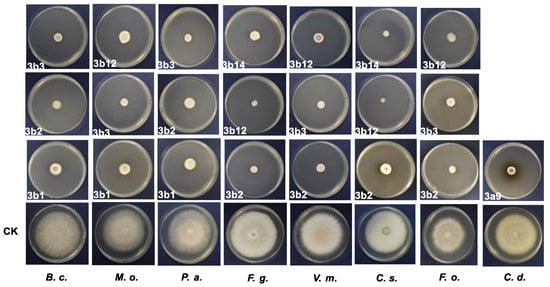

To further sustain the measured EC50 values, the inhibitory effects (>80%) at 50 μg/mL of the most potent compounds were shown in Figure 3. For C. destructivum, only one compound, 3a9, exhibited inhibitory effects higher than 80%, which was different from other fungi and depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects (>80%) of the most potent compounds on eight different plant pathogenic fungi at 50 μg/mL with blank control.

4. Discussion

The chemical structures of compounds 3a1–3a16, 3b1–3b20 were confirmed by attentively analyzing the aromatic region of proton NMR spectra, referring to the chemical structure of precursors, i.e., aromatic aldehydes, while the methyl carbamate moiety was easily interpreted by the methoxy peak and broad single peak of amide NH. The chemical structure was further substantiated by carbon NMR spectra with the characteristic peaks of carbonyl carbon and OMe as well as the fingerprint peaks of aromatic moiety. Furthermore, the chemical structures of compounds 3a6 and 3b2 were secured by comparing the corresponding spectra with those of 3a5 and 3b1, for the ethoxy peaks were characteristic while the aromatic moiety was the same.

Based on the in vitro screening results listed in Table 1 and Table 2, a preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis was performed. The analysis is structured by compound series and substitution patterns.

A-Series (Mono-substituted N-aryl carbamates):

Para-substitution: Activity against C. destructivum was enhanced by strong electron-donating alkoxy groups (3a8, 3a9). Other substituents at the para-position, regardless of electronic nature, generally resulted in moderate or low activity.

Meta-substitution: Introducing a phenyl group at the meta-position (3a13) conferred broad-spectrum activity. Other meta-substituents led to low or moderate activity. Replacing the phenyl ring with a bulkier β-naphthyl group did not improve activity.

B-Series (Di- or Tri-substituted N-aryl carbamates):

Halogen Substitution is Critical: The incorporation of chlorine atoms or two bromine atoms on the phenyl ring significantly enhanced antifungal potency, as seen in compounds 3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b4, 3b11, 3b12, 3b13, and 3b14. This underscores the positive role of specific halogens (Cl, Br).

Electronic Effects: Electron-donating groups or the replacement of Cl/Br with other halogens (F, I) or groups like CF3 diminished potency.

Steric Effects: Introducing a third chlorine atom (3b20) did not further enhance activity compared to the di-substituted analogues, suggesting an optimal substitution pattern.

5. Conclusions

In summary, thirty-six carbamate derivatives have been designed and synthesized via a green Curtius rearrangement route inspired by physostigmine and commercial carbamate fungicides. The compounds were fully characterized, and their antifungal activities were systematically evaluated in vitro against eight plant pathogenic fungi. The bioassay results identified several potent compounds. Specifically, compounds 3b1 and 3b2 showed superior antifungal activity against B. cinerea, compounds 3b2 exhibited higher activity against F. graminearum, compound 3a9 significantly inhibited C. destructivum, and compound 3b12 was most effective against C. siamense, all outperforming azoxystrobin. Furthermore, compounds 3b1, 3b2, 3b3, 3b11, and 3b12 demonstrated outstanding broad-spectrum in vitro fungicidal activities, making them promising leads for further development. The preliminary SAR study highlighted that di-substituted phenyl rings bearing chlorine or bromine atoms are crucial for high antifungal potency.

However, this study has limitations. The evaluations are preliminary and conducted solely in vitro. Future work should focus on the following: (1) in vivo efficacy studies to confirm activity in plant systems, (2) more detailed mechanistic investigations to elucidate the mode of action, and (3) further structural optimization of the lead compounds (e.g., 3b2, 3b3, 3b12) to improve potency and physicochemical properties. Despite these limitations, these results are anticipated to provide critical insights for the design and development of novel antifungal agents, theoretically supporting the development of environmentally friendly agrochemicals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122741/s1, Supplementary File S1: Detailed operation process of biological assays; and 1H NMR, 13C NMR, HRMS spectra of target compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., Z.H., X.D., J.Z., Y.C. and M.G.; methodology, X.L., Z.H., X.D., J.Z., Y.C. and M.G.; investigation, X.L., Z.H., X.D., J.Z., Y.C. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., Z.H., X.D., J.Z., Y.C., M.G. and B.H.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and R.L.; supervision, L.S., B.H. and R.L.; project administration, L.S., B.H. and R.L.; funding acquisition, X.L., B.H. and L.S.; design of the work, L.S., B.H. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, grant number 2020J05225, 2024J01375, and 2024J01374; Agriculture Research System of China, grant number CARS-44.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The administrative support of Jiangtao Gao and technical support of Zongwen Wang is greatly acknowledged. The authors appreciate their continuous solid support for the work in the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fones, H.N.; Bebber, D.P.; Chaloner, T.M.; Kay, W.T.; Steinberg, G.; Gurr, S.J. Threats to Global Food Security from Emerging Fungal and Oomycete Crop Pathogens. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberth, C.; Jeanmart, S.; Luksch, T.; Plant, A. Current Challenges and Trends in the Discovery of Agrochemicals. Science 2013, 341, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Henk, D.A.; Briggs, C.J.; Brownstein, J.S.; Madoff, L.C.; McCraw, S.L.; Gurr, S.J. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 2012, 484, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, M.; Han, J.; Pang, X. Fungal and mycotoxin occurrence, affecting factors, and prevention in herbal medicines: A review. Toxin Rev. 2022, 41, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrod, J.P.; Bundschuh, M.; Arts, G.; Brühl, C.A.; Imfeld, G.; Knäbel, A.; Payraudeau, S.; Rasmussen, J.J.; Rohr, J.; Scharmüller, A.; et al. Fungicides: An overlooked pesticide class. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3347–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheuk, F.; Basiouni, S.; Shehata, A.A.; Dick, K.; Hajri, H.; Lasram, S.; Yilmaz, M.; Emekci, M.; Tsiamis, G.; Spona-Friedl, M.; et al. Status and prospects of botanical biopesticides in Europe and Mediterranean countries. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, T.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Siddaiah, C.N.; Dai, X.F.; Chen, J.Y.; Wang, D.; Kong, Z.Q. Overview of the control of plant fungal pathogens by natural products derived from medicinal plants. Plant Prot. Sci. 2023, 59, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.-R.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Jin, Y.-S. Natural Products as Antifungal Agents against Invasive Fungi. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 1859–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.C.; Hahn, D.R.; Garizi, N.V. Natural products, their derivatives, mimics and synthetic equivalents: Role in agrochemical discovery. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.C.; Sparks, J.M.; Duke, S.O. Natural product-based crop protection compounds-origins and future prospects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 2259–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K.; Rashwan, E.K.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Shaheen, H.; Wasef, L. Physostigmine: A Plant Alkaloid Isolated from Physostigma venenosum: A Review on Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacological and Toxicological Activities. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2020, 10, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenocak, A.; Tümay, S.O.; Makhseed, S.; Demirbas, E.; Durmuş, M. A synergetic and sensitive physostigmine pesticide sensor using coppercomplex of 3D zinc (II) phthalocyanine-SWCNT hybrid material. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 174, 112819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, R.L.; Fukuto, T.R.; Frederickson, M.; Peak, L. Insecticide Screening, Insecticidal Activity of Alkylthiophenyl N-Methylcarbamates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1965, 13, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F. Fungicides. In Agrochemicals: Composition, Production, Toxicology, Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 383–494. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Carbamate Pesticides: A General Introduction; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki, M.; Ozaki, M.; Fujimoto, S.; Fukumoto, S. Development of a novel fungicide, pyribencarb. J. Pestic. Sci. 2014, 39, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, S.; Sun, F.; Sun, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, B.; Zou, N.; Lin, J.; Mu, W.; Pang, X. Residual analysis of QoI fungicides in multiple (six) types of aquaticorganisms by UPLC-MS/MS under acutely toxic conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 12075–12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichinari, D.; Nagaki, A.; Yoshida, J. Generation of hazardous methyl azide and its application to synthesis of a key-intermediate of picarbutrazox, a new potent pesticide in flow. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 6224–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, H.; Ezaki, R.; Hamada, T.; Tsuda, M.; Ebihara, K. Development of a novel fungicide, tolprocarb. J. Pestic. Sci. 2019, 44, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, F.-X.; Wang, J.-H.; Shi, Y.-H.; Niu, L.-Z.; Jiang, L. Design, Synthesis and Antifungal Activity of Novel Benzoylcarbamates Bearing a Pyridine Moiety. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-H.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C.-X.; Li, P.-H.; Jiang, L. Synthesis and fungicidal activity of 2-(methylthio)-4-methylpyrimidine carboxamides bearing a carbamate moiety. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2023, 198, 655–658. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Luo, F. Synthesis and Antifungal Activities of Alkyl N-(1,2,3-Thiadiazole-4-Carbonyl) Carbamates and S-Alkyl N-(1,2,3-Thiadiazole-4-Carbonyl) Carbamothioates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3872–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Wang, S.; Du, L.; Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H.; Dong, Y. Synthesis, bioactivity and 3D-QSAR of azamacrolide compounds with a carbamate or urea moiety as potential fungicides and inhibitors of quorum sensing. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 3048–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yang, W.; Meng, F. Design and synthesis of novel totarol derivatives bearing carbamate moiety as potential fungicides. Monatshefte Chem. 2023, 154, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Yang, D.; Che, C.; Ma, Y.; Rui, C.; Yan, X.; Qin, Z. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, Insecticidal and FungicidalActivity of (1H-1,2,4-Triazol-5-yl) carbamates. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2016, 37, 892–901. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Synthesis and fungicidal activity of (2-chloropyridin-5-yl) methyl carbamates. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 17, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- You, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, P.; Guo, Q.; Xu, Z. Synthesis and biological activity of N-substituted phenyl-1-1(2,4-difluorophenyl)-2-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)ethylcarbamate. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2022, 24, 723–731. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lei, N.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y. Synthesis and bacteriostatic activity of ten-, twelve- and sixteen-membered azalactone compounds containing phenoxymethyl and chloromethyl group. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2024, 26, 870–882. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, D.; Mishra, N.; Mishra, V. Various approaches for the synthesis of organic carbamates. Curr. Org. Synth. 2007, 4, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, T.; Liu, L.; Pan, X.; Huang, B.; Yao, H.; Lin, R.; Tong, R. Unified and green oxidation of amides and aldehydes for the Hofmann and Curtius rearrangements. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, L.; Duan, X.; You, S.; Yu, B.; Pan, X.; Guan, X.; Lin, R.; Song, L. Green synthesis and antifungal activities of novel N-aryl carbamate derivatives. Molecules 2024, 29, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, H.; Miyagi, M.; Nitta, S.; Takahashi, S. Production Method for Amidate Compound. U.S. Patent US 2020/0024237 A1, 23 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karapetyan, V.; Mkrtchyan, S.; Schmidt, A.; Gütlein, J.-P.; Villinger, A.; Reinke, H.; Jiao, H.; Fisher, C.; Langer, P. Synthesis of 3,4-benzo-7-hydroxy-2,9-diazabicyclo [3.3.1]non-7-enes by cyclization of 1,3-bis(silyl enol ethers) with quinazolines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 2961–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiffen, M.; Hoffmann, R.W. Zur Reaktion von Amidacetalen mit Heterocumulenen. Chem. Berichte 1977, 110, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.-H.; Lei, H.; Chen, M.; Ren, Z.-H.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.-Y. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation of Amines: Switchable Approaches to Carbamates and N,N’-Disubstituted Ureas. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Kumar, D.; Mishra, N.; Tiwari, V.K. An efficient one-pot synthesis of N,N′-disubstituted ureas and carbamates from N-Acylbenzotriazoles. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 84512–84522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Ablajan, K. Synthesis of N-Phenylcarbamate by C-N Coupling Reaction without Metal Participation. Synthesis 2023, 55, 3113–3120. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Xue, M.; Yan, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, K.; Zhang, S. Electrochemical Hofmann rearrangement mediated by NaBr: Practical access to bioactive carbamates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4615–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, Y.; Matsuo, M. The Hofmann Reaction of 3,5-Di-tert-butylbenzamide. J. Soc. Chem. Ind. 1967, 70, 931–934. [Google Scholar]

- Fra, L.; Millán, A.; Souto, J.A.; Muňiz, K. Indole Synthesis Based On A Modified Koser Reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7349–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).