The Effects of High Temperature Stress and Its Mitigation Through the Application of Biostimulants in Controlled Environment Agriculture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Temperature Stress Effects

2.1. Morphological Temperature Responses

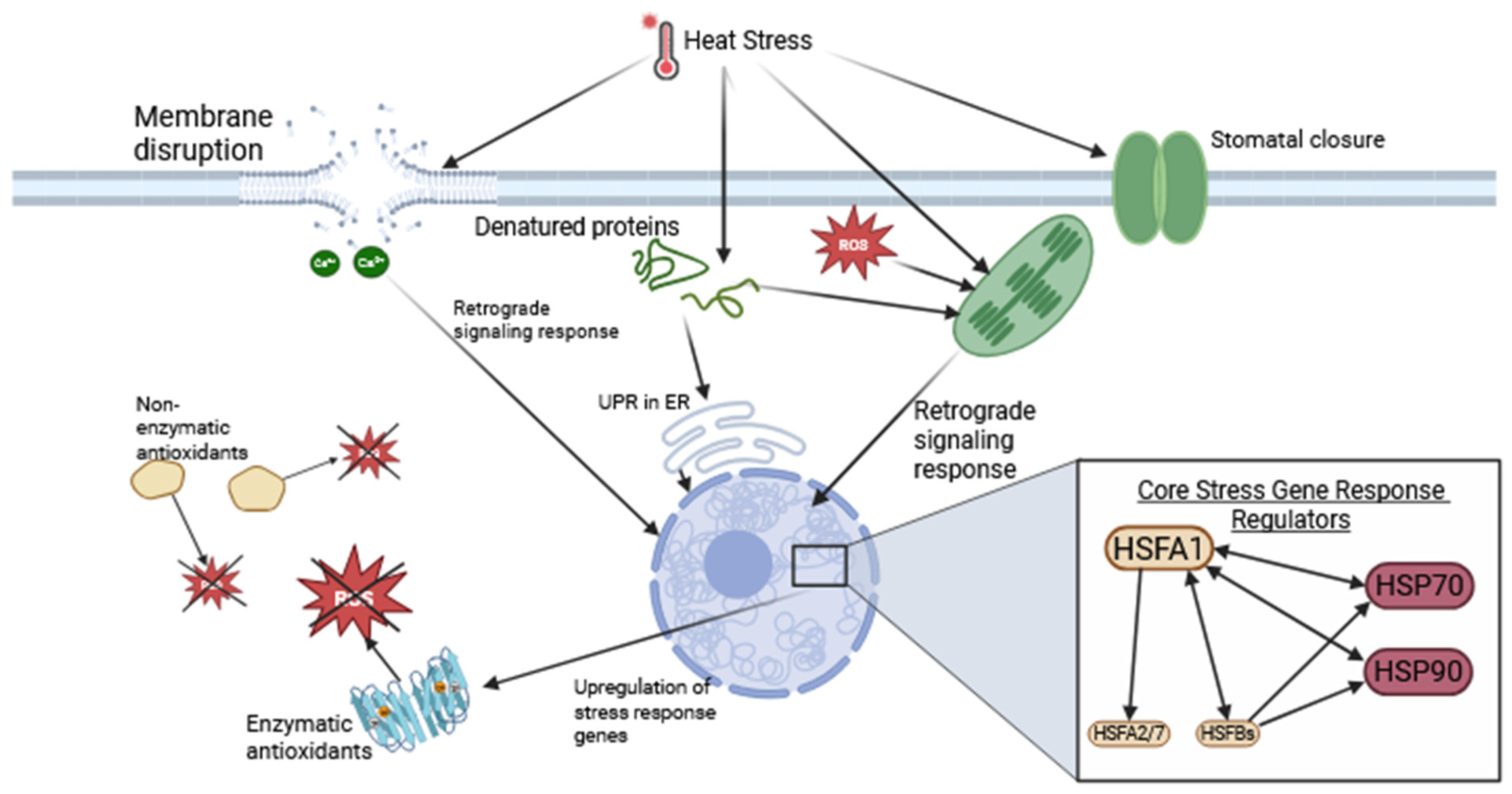

2.2. Cellular Temperature Stress Responses

2.3. Hormonal and Molecular Response

2.4. Effects of Temperature Stress on Crops and the Role of Controlled Environment Agriculture

3. Biostimulants

3.1. Seaweed Extracts

3.2. Chitin and Chitosan

3.3. Protein Hydrolysates, N-Containing Compounds, and Amino Acids

3.4. Inorganic Compounds

3.5. Beneficial Microorganisms

3.6. Humic Substances and Other Potential Biostimulants

3.7. Combined Treatments

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| APX | Ascorbate Peroxidase |

| AsA | Ascorbic Acid |

| bHLH | Basic helix–loop–helix |

| BR | Brassinosteroid |

| bZIP | Basic Leucine Zipper |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CE | Controlled Environment |

| CEA | Controlled Environment Agriculture |

| CK | Cytokinin |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ETC | Electron Transport Chain |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| GPX | Glutathione Reductase |

| HSF | Heat Shock Factor |

| HSP | Heat Shock Protein |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| PGPM | Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms |

| PGPR | Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| PIF4/7 | Phytochrome Interacting Factor 4/7 |

| POD | Peroxidases |

| PSI | Photosystem I |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| SE | Seaweed Extract |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

References

- Engler, N.; Krarti, M. Review of energy efficiency in controlled environment agriculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owino, V.; Kumwenda, C.; Ekesa, B.; Parker, M.E.; Ewoldt, L.; Roos, N.; Lee, W.T.; Tome, D. The impact of climate change on food systems, diet quality, nutrition, and health outcomes: A narrative review. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 941842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, S. NASA Finds Summer 2024 Hottest to Date. 11 September 2024. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/earth/nasa-finds-summer-2024-hottest-to-date/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Wang, L.; Norford, L.; Arkin, A.; Niu, G.; Valle de Souza, S.; Zahid, A.; Shih, P.M.; Piette, M.A.; Ganapathysubramanian, B. Finding sustainable, resilient, and scalable solutions for future indoor agriculture. npj Sci. Plants 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuela, J.; Ben, C.; Boldyrev, S.; Gentzbittel, L.; Ouerdane, H. The indoor agriculture industry: A promising player in demand response services. Appl. Energy 2024, 372, 123756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, M.-H.; Monfet, D. Analysing the influence of growing conditions on both energy load and crop yield of a controlled environment agriculture space. Appl. Energy 2024, 368, 123406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in Plant Science: A Global Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish, S.V.K.; Way, D.A.; Sharkey, T.D. Plant heat stress: Concepts directing future research. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Mu, X.R.; Gao, J.; Lin, H.X.; Lin, Y. The molecular basis of heat stress responses in plants. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1612–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, J.P.; Sharkey, T.D. Pollen development at high temperature and role of carbon and nitrogen metabolites. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 2759–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamir, M.; Mahmood, T.; Trethowan, R.; Ahmad, N. An overview of heat stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Heckathorn, S.; Mishra, S.; Krause, C. Heat Stress Decreases Levels of Nutrient-Uptake and -Assimilation Proteins in Tomato Roots. Plants 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manghwar, H.; Li, J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response Signaling in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant Responses to Heat Stress: Physiology, Transcription, Noncoding RNAs, and Epigenetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Niazi, A.K.; Akhtar, J.; Saifullah; Farooq, M.; Souri, Z.; Karimi, N.; Rengel, Z. Acquiring control: The evolution of ROS-Induced oxidative stress and redox signaling pathways in plant stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 141, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species: Generation, Signaling, and Defense Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, C. Sensitivity and Responses of Chloroplasts to Heat Stress in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Das, A.; Roy, A.R.; Khan, J.J.; Ahmad, I.; Biswas, A.; Pallob, A.T.; Mondol, M.; Yeasmin, S.T. Plant development and heat stress: Role of exogenous nutrients and phytohormones in thermotolerance. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, M.; Brini, F.; Sharma, A.; Landi, M. Role of jasmonic acid in plants: The molecular point of view. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1471–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Gull, S.; Ali, M.M.; Yousef, A.F.; Ercisli, S.; Kalaji, H.M.; Telesiński, A.; Auriga, A.; Wróbel, J.; Radwan, N.S.; et al. Heat stress mitigation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) through foliar application of gibberellic acid. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Euring, D.; Cha, J.Y.; Lin, Z.; Lu, M.; Huang, L.-J.; Kim, W.Y. Plant Hormone-Mediated Regulation of Heat Tolerance in Response to Global Climate Change. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 627969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Baek, K.-H. Jasmonic Acid Signaling Pathway in Response to Abiotic Stresses in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooam, M.; Dixon, N.; Hilvert, M.; Misko, P.; Waters, K.; Jourdan, N.; Drahy, S.; Mills, S.; Engle, D.; Link, J.; et al. Effect of temperature on the Arabidopsis cryptochrome photocycle. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Xiong, L.; Li, H.; Lyu, X.; Yang, G.; Zhao, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, B. Cryptochrome 1 Inhibits Shoot Branching by Repressing the Self-Activated Transciption Loop of PIF4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, J.J.; Balasubramanian, S. Thermomorphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, F.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Du, J. Phytonutrients: Sources, bioavailability, interaction with gut microbiota, and their impacts on human health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 960309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amengual, J. Bioactive Properties of Carotenoids in Human Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, M.; Wu, F.; Wang, F.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Du, J. ABA-mediated reprogramming of carotenoid metabolism under heat stress impairs tomato fruit ripening. Plant Sci. 2025, 362, 112755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2022, 27, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilahy, R.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Piro, G.; Lenucci, M.S.; Hdider, C. Year-to-year Variations in Antioxidant Components of High-Lycopene Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Breeding Lines. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopylov, A.T.; Malsagova, K.A.; Stepanov, A.A.; Kaysheva, A.L. Diversity of Plant Sterols Metabolism: The Impact on Human Health, Sport, and Accumulation of Contaminating Sterols. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Fu, X.; Chu, Y.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, H.; Zhu, B. Biosynthesis and the Roles of Plant Sterols in Development and Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Toward a Sustainable Agriculture Through Plant Biostimulants: From Experimental Data to Practical Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sible, C.N.; Seebauer, J.R.; Below, F.E. Plant Biostimulants: A Categorical Review, Their Implications for Row Crop Production, and Relation to Soil Health Indicators. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, V.P. Tissue therapy by biological stimulants. Med. Hyg. 1947, 5, 365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caradonia, F.; Battaglia, V.; Righi, L.; Pascali, G.; La Torre, A. Plant Biostimulant Regulatory Framework: Prospects in Europe and Current Situation at International Level. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying down Rules on the Making; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mughunth, R.J.; Velmurugan, S.; Mohanalakshmi, M.; Vanitha, K. A review of seaweed extract’s potential as a biostimulant to enhance growth and mitigate stress in horticulture crops. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, B.; Vidya, R. Application of seaweed extracts to mitigate biotic and abiotic stresses in plants. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juthery, H.; Abbas Drebee, H.; HAl-Khafaji, B.; Hadi, R. Plant Biostimulants, Seaweeds Extract as a Model (Article Review). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Al-Qadisiyah, Iraq, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.S.; Mantin, E.G.; Adil, M.; Bajpai, S.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Ascophyllum nodosum-Based Biostimulants: Sustainable Applications in Agriculture for the Stimulation of Plant Growth, Stress Tolerance, and Disease Management. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, N.; Goni, O.; Langowski, L.; O’Connell, S. Ascophyllum nodosum Extract Biostimulant Processing and Its Impact on Enhancing Heat Stress Tolerance During Tomato Fruit Set. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Nanda, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B.N.; Mukherjee, A. Seaweed extracts: Enhancing plant resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1457500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaetxea, M.; Garnica, M.; Erro, J.; Sanz, J.; Monreal, G.; Zamarreño, A.M.; García-Mina, J.M. The plant growth-promoting effect of an Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) extract derives from the interaction of its components and involves salicylic-, auxin- and cytokinin-signaling pathways. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, O.; Quille, P.; O’Connell, S. Seaweed Carbohydrates. In The Chemical Biology of Plant Biostimulants; Geelen, D., Xu, L., Stevens, C.V., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 57–95. [Google Scholar]

- González-González, M.F.; Ocampo-Alvarez, H.; Santacruz-Ruvalcaba, F.; Sanchez-Hernandez, C.V.; Casarrubias-Castillo, K.; Becerril-Espinosa, A.; Castaneda-Nava, J.J.; Hernandez-Herrera, R.M. Physiological, Ecological, and Biochemical Implications in Tomato Plants of Two Plant Biostimulants: Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Seaweed Extract. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Lu, X.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Polysaccharides Derived from the Brown Algae Lessonia nigrescens Enhance Salt Stress Tolerance to Wheat Seedlings by Enhancing the Antioxidant System and Modulating Intracellular Ion Concentration. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, H.; Valizadehkaji, B.; Naeini, M.R. Biostimulant-induced drought tolerance in grapevine is associated with physiological and biochemical changes. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J. Seaweed Extract Improved Yields, Leaf Photosynthesis, Ripening Time, and Net Returns of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.). ACS Omega 2020, 5, 4242–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Sabbatini, P.; Tombesi, S.; Norrie, J.; Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Palliotti, A. Effects of a biostimulant derived from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum on ripening dynamics and fruit quality of grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 232, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, B.; Sarıdaş, M.A.; Çeliktopuz, E.; Kafkas, E.; Paydaş Kargı, S. Health and taste related compounds in strawberries under various irrigation regimes and bio-stimulant application. Food Chem. 2018, 263, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgan, H.Y.; Aksu, K.S.; Zikaria, K.; Gruda, N.S. Biostimulants Enhance the Nutritional Quality of Soilless Greenhouse Tomatoes. Plants 2024, 13, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, W.; Chen, X.; Li, L. Chitosan Reduces Damages of Strawberry Seedlings under High-Temperature and High-Light Stress. Agronomy 2023, 13, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesca, S.; Najai, S.; Zhou, R.; Decros, G.; Cassan, C.; Delmas, F.; Ottosen, C.O.; Barone, A.; Rigano, M.M. Phenotyping to dissect the biostimulant action of a protein hydrolysate in tomato plants under combined abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 179, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Colla, G. Combining Molecular Weight Fractionation and Metabolomics to Elucidate the Bioactivity of Vegetal Protein Hydrolysates in Tomato Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 976. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Solangi, F.; Azeem, S.; Bodlah, M.A.; Zaheer, M.S.; Niaz, Y.; Ashraf, M.; Abid, M.; Gul, H.; et al. Impact of amino acid supplementation on hydroponic lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) growth and nutrient content. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muneer, S.; Park, Y.G.; Kim, S.; Jeong, B.R. Foliar or Subirrigation Silicon Supply Mitigates High Temperature Stress in Strawberry by Maintaining Photosynthetic and Stress-Responsive Proteins. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 36, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A.L.; Imran, M.; Asaf, S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Bilal, S.; Numan, M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Lee, I.-J. Silicon-induced thermotolerance in Solanum lycopersicum L. via activation of antioxidant system, heat shock proteins, and endogenous phytohormones. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Ramezani, M.R.; Rajaii, N. Improving oxidative damage, photosynthesis traits, growth and flower dropping of pepper under high temperature stress by selenium. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Jan, R.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, I.J. Extending thermotolerance to tomato seedlings by inoculation with SA1 isolate of Bacillus cereus and comparison with exogenous humic acid application. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.; Goswami, P.; Paritosh, K.; Kumar, M.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Seafood waste: A source for preparation of commercially employable chitin/chitosan materials. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.Á.; Rodriguez, A.T.; Alfonso, L.; Peniche, C. Chitin and its derivatives as biopolymers with potential agricultural applications. Biotechnol. Appl. 2010, 27, 270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cogello-Herrera, K.; Bonfante-Álvarez, H.; Ávila-Montiel, G.; Barros, A.H.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Techno-Economic sensitivity analysis of large scale chitosan production process from shrimp shell wastes. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 70, 2179–2184. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, M.B.; Struszczyk-Swita, K.; Li, X.; Szczesna-Antczak, M.; Daroch, M. Enzymatic Modifications of Chitin, Chitosan, and Chitooligosaccharides. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kaufmann, M.; Makechemu, M.; Van Poucke, C.; De Keyser, E.; Uyttendaele, M.; Zipfel, C.; Cottyn, B.; Pothier, J.F. Assessment of transcriptional reprogramming of lettuce roots in response to chitin soil amendment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1158068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, V.; Botella, M.Á.; Hellín, P.; Fenoll, J.; Flores, P. Dose-Dependent Potential of Chitosan to Increase Yield or Bioactive Compound Content in Tomatoes. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, M.; Correia, S.; Guinan, K.J.; Sujeeth, N.; Bragança, R.; Gonçalves, B. Recent Advances in the Molecular Effects of Biostimulants in Plants: An Overview. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Tellez, L.I.; Gómez-Trejo, L.F.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. Biostimulant Effects and Concentration Patterns of Beneficial Elements in Plants. In Beneficial Chemical Elements of Plants: Recent Developments and Future Prospects; Pandey, S., Tripathi, D.K., Singh, V.P., Sharma, S., Chauhan, D.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 58–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Piccolo, E.; Ceccanti, C.; Guidi, L.; Landi, M. Role of beneficial elements in plants: Implications for the photosynthetic process. Photosynthetica 2021, 59, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofano, F.; El-Nakhel, C.; Rouphael, Y. Biostimulant Substances for Sustainable Agriculture: Origin, Operating Mechanisms and Effects on Cucurbits, Leafy Greens, and Nightshade Vegetables Species. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, G.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Tran, L.P. Silicon-mediated heat tolerance in higher plants: A mechanistic outlook. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, M.; Giovannetti, G. Borderline Products between Bio-fertilizers/Bio-effectors and Plant Protectants: The Role of Microbial Consortia. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. A 2015, 5, 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Abou Jaoude, R.; Ficca, A.G.; Ruzzi, M. Effect of microbial plant biostimulants on fruit and vegetable quality: Current research lines and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1251544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, A.M.; Mannino, G.; Contartese, V.; Bertea, C.M.; Ertani, A. Microbial Biostimulants as Response to Modern Agriculture Needs: Composition, Role and Application of These Innovative Products. Plants 2021, 10, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Regulating Growth, Enhancing Productivity, and Potentially Influencing Ecosystems under Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, F.; Sarfaraz, A.; Kama, R.; Kanwal, R.; Li, H. Structure-Based Function of Humic Acid in Abiotic Stress Alleviation in Plants: A Review. Plants 2025, 14, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, S.; Ertani, A.; Francioso, O. Soil–root cross-talking: The role of humic substances. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2017, 180, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Botton, A.; Vaccaro, S.; Vezzaro, A.; Quaggiotti, S.; Nardi, S. Humic substances affect Arabidopsis physiology by altering the expression of genes involved in primary metabolism, growth and development. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 74, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselvan, G.B.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Di Foggia, M.; Nardi, S.; Carletti, P. Biostimulant activity of humic substances extracted from leonardites. Plant Soil 2017, 420, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.Y.; Kang, S.H.; Ali, I.; Lee, S.C.; Ji, M.G.; Jeong, S.Y.; Shin, G.I.; Kim, M.G.; Jeon, J.R.; Kim, W.Y. Humic acid enhances heat stress tolerance via transcriptional activation of Heat-Shock Proteins in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Coppa, E.; Hoagland, L.; Colla, G. Using Microgranular-Based Biostimulant in Vegetable Transplant Production to Enhance Growth and Nitrogen Uptake. Agronomy 2020, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobránszki, J. From mystery to reality: Magnetized water to tackle the challenges of climate change and for cleaner agricultural production. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 139077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Full Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic | Ascorbate peroxidase | APX |

| Enzymatic | Catalase | CAT |

| Enzymatic | Glutathione reductase | GR |

| Enzymatic | Glutathione peroxidase | GPX |

| Enzymatic | Monodehydroascorbate reductase | MDAR |

| Enzymatic | Peroxidase | POD |

| Enzymatic | Peroxiredoxins | PRX |

| Enzymatic | Superoxide dismutase | SOD |

| Non-enzymatic | Ascorbate | n/a |

| Non-enzymatic | Ascorbic acid | AsA |

| Non-enzymatic | Carotenoids | n/a |

| Non-enzymatic | Flavonoids | n/a |

| Non-enzymatic | Glutathione | n/a |

| Non-enzymatic | Isoprenoids | n/a |

| Non-enzymatic | Tocopherols | n/a |

| Hormone | Key Effects | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Abscisic Acid (ABA) | Induction of stomatal closure to decrease transpiration rates. Increases ROS levels to enhance antioxidant capacity by elevating ROS scavenging enzyme activity. Modulates carbohydrate and energy status [19]. | Unknown. Proposed mechanism through regulation of HSFs and HSPs. Sucrose metabolism activated by ABA under heat stress; sucrose and ABA show synergistic effects for heat tolerance [19]. |

| Auxin | Thermomorphogenesis, specifically stem elongation and leaf hyponasty [19]. | Auxin Response Factors activate auxin-responsive gene expression. HSP90 required for induction of auxin-responsive genes. PIF4 controls the expression of auxin biosynthesis in thermomorphogenesis [19]. |

| Brassinosteroid (BR) | A significant increase in thermotolerance is induced by BRs. Increase protein synthesis, including membrane proteins such as ATPase and aquaporins. Promotes growth. Induces root elongation [19]. | Downstream signalling processes. Translation initiation and elongation factors higher in translational machinery of BR-treated seedlings. BZR1 regulates growth-promoting genes and activates PIF4 [19]. |

| Cytokinin (CK) | Protective role for developing flowers and enhancing activity of enzymatic antioxidants, including SOD and APX. CK important for long-term temperature acclimation and changes in development to recover chloroplast and photosynthetic abilities [19]. | Heat-induced CK activates transcription genes of photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism. Heat and CK response proteomes target chloroplasts. Most of the nature of CK activity remains unknown [19]. |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Reduces heat stress-related membrane damage and modulates antioxidant enzyme activities such as SOD, CAT, and POD. Improves photosynthetic efficiency and scavenging of ROS through induction of antioxidants under stress and protects PSII function [19]. | Mechanism largely not understood. Found to increase HSP expression. Increased proline content observed in treated plants [19]. |

| Jasmonic Acid (JA) | Regulates plant growth and development, flower development, leaf senescence, root formation, and stomatal opening [21]. | Largely not well understood. Suggested to be through JA-inducible TFs regulating stress response-related genes to promote specific protective mechanisms that are suppressed under normal conditions [23]. |

| Gibberellin (GA) | Regulate plant height, leaf expansion, dry matter accumulation, tissue differentiation, flower blooming, and transpiration [20]. Inhibits growth under stress conditions [21]. | Mechanisms not yet understood [21] |

| Biostimulant | Crop | Conditions | Responses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seaweed Extract (Padina gymnospora) (Root) 8 g L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of vermiculite, sand, and irrigated, natural lighting, day temperatures 27 °C ± 2 °C and night >15 °C ± 2 °C. Two treatments, once at day 1 and the other at day 15. No heat stress. | Shoot and root length increased by a total of 16%. Leaf area increased by 181%, root area by 17%, fresh weight by 150%, and dry weight by 73%. No acceleration of flowering identified. | [47] |

| Seaweed Extracts (Ascophyllum nodosum) PSI-494 (high temp extraction): 0.106% w/v C129 (low temp extraction): 0.106% w/v | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | CE growth room, soil, 31 °C long-term exposure during reproductive stage (mild heat stress) | Both treatments improved flower development, increased pollen viability and fruit production, and improved sugar retention in leaves. PSI-494 increased fruit number by 86% compared to untreated stressed plants. C129 and PSI-494 increased pollen viability reduction by 3.2 and 4.4 compared to the 80% reduction in the untreated plants. Fruit number increased in both C129 and PSI-494 by 22 and 33%, respectively. | [43] |

| Chitosan (both foliar and root in tandem) Root: 0.3 mg L−1 Foliar: 0.6 mL L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of coco coir, irrigated with nutrient solution. No temperature control—daytime 23–28 °C, night 18–20 °C. | Increased plant height (4.7%), leaf area (46.43%), and stem diameter (10.23%). Increased chlorophyll content (SPAD) (23%). Increased fruit weight and volume. Increased fruit total soluble solids, phenol content, and flavonoid content by 17%, 27%, and 46%, respectively. | [53] |

| Chitosan (Foliar) 50 mL of 100 mg kg−1 | Fragaria × ananassa (Strawberry) | CE cabinets, media not listed. High temperature (38 °C) and high light. | Post-stress chlorophyll content increased by 16.9% compared to positive control. PSII damage reduced. Reduced accumulation of H2O2 and O2−. Proline content increased by 9.9%. Reduced electrolyte leakage. Increased ascorbic acid levels. | [54] |

| Protein Hydrolysate from Sugar Cane and Yeast (Root) 3 g L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (heat tolerant LA3120 and non-heat tolerant E42) (Tomato) | Greenhouse, growth media with nutrient solution irrigation. Control day temperature: 25 °C. Control night temperature: 20 °C. Heat stress day temperatures: 31 °C. Heat stress night temperatures: 30 °C. | Variable physiological responses between cultivars. Non-tolerant benefits included an increased total AsA content and a lower reduced AsA content. Lipid peroxidation was lower and stomatal densities were reduced, indicating that leaf structure was protected from thermal stress through membrane stabilisation and water loss-preventing mechanisms. In heat tolerant variety LA3120, the reduced AsA content was increased and H2O2 content was decreased. Lipid peroxidation was higher than in other groups, stomatal density was akin to the unstressed untreated group, and lower than the untreated stressed group; however, stomatal width was significantly larger, indicating that stomatal response pathways were differentially affected, yielding little benefit to water use efficiency. | [55] |

| Protein Hydrolysate from Legume Seed (foliar, root, and tandem) Foliar: 6 g L−1 Root: 285.71 g L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Growth chamber, vermiculite growth media. Photoperiod was 12 h. PH used contains 17 free amino acids and soluble peptides, macronutrients, and micronutrients. Compared PH and PH-fraction, which contained higher concentration of free amino acids. | Increased root length across both treatments. Metabolomic analysis identified over 250 compounds involved in secondary metabolism-related pathways influenced by treatments. Biochemical processes including N-containing secondary metabolites, phenylpropanoids, and terpenes were most influenced by treatments. PH treatment increased flavonoid accumulation. BR, CK, and JA biosynthesis-related compounds were downregulated. Gibberellins elevated in response to both treatments. PH fraction provided auxin-like activity and a decrease in cytokinins and abscisic acid accumulation. A PH containing lower quantity of free amino acids had a greater effect on root growth and micronutrient accumulation than the fractionated formula. | [56] |

| Amino Acids (foliar and root in tandem) Root: 1.76 g L−1 Foliar: 0.6 g L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of coco coir, irrigated with nutrient solution. No temperature control—daytime 23–28 °C, night 18–20 °C. | Plant height not significantly impacted, but leaf area and number increased by 33% and 73%, respectively, with chlorophyll content (SPAD) increasing by 19%. Increased total soluble solids of fruit increased by 27%, EC by 10%, and phenols and flavonoids by 19% and 174%, respectively, without significant impact on pH or titratable acidity. | [53] |

| Amino Acids (Root) Methionine: 20 mg L−1 Tryptophan: 220 mg L−1 Glycine: 200 mg L−1 | Lactuca sativa L. (Lettuce) | Glasshouse. Hydroponic (NFT) with Hoagland’s nutrient solution. Daytime temp 34 °C, night 24 °C. Photoperiod was 12 h. | Methionine treatment: leaf area increased 31.41%. Tryptophan treatment: leaf area decreased by 86.25% and height by 82.91%. Glycine treatment: leaf area decreased by 29.67%. | [57] |

| Inorganic Compound (Silicon: K2SIO3, NA2SIO3, CASIO3) (foliar, root and both) 3 Concentrations: 35 and 70 mg L−1 | Fragaria × ananassa (Strawberry) | Greenhouse, Tosilee growth media. Initial growth temperature: 25 °C. Temperature stress: 33 °C and 41 °C for 48 h in CE chambers. Photoperiod was 16 h. | Both foliar and root treatments of K2SiO3 mitigate H2O2 and O2−1 accumulation in leaves (indicative of oxidative damage mitigation). Photosynthetic components of PSI and PSII were maintained at high temperatures, somewhat maintaining photosynthesis. SOD, CAT, and APX increased under temperature stress and Si application in all forms. Most effective form of Si was K2SiO3 | [58] |

| Inorganic Compound (Silicon, NA2SIO3) (Foliar) 50 mL of 1 MM SI | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | CE chamber, peat moss. Day temperatures: 30 °C, heat stress up to 43 °C ± 0.5 °C for 6 h per 12 h day for 10 days. Night temperatures: 30 °C | Increased shoot length and shoot biomass both with (31% and 70%, respectively) and without stress (36% and 61%). Stem diameter also increased by 72% and 36% with and without heat stress. Root morphology, length, and fresh weight increased by 41%, 42%, and 28%. Chl a, Chl b, and carotenoid content increased by 38%, 38%, and 39%. O2− production comparatively reduced, indicating decreased ROS generation. Oxidative stress indicators reduced, specifically relating to lipid perodixation. CAT, SOD, and PPO activity increased in stressed treated plants by 61%, 450%, and 167% compared to normal conditions. Upregulation of antioxidant enzyme biosynthetic genes SlCAT, SlAPX, SlPOD, and SlSOD. HSF genes upregulated under stress (SlHsfA1a, SlHsfA1b, SlHsfA2, SlHsfA3, and SlHsfA7). Reduced ABA under stress and control conditions. Salicylic acid content also reduced through downregulation of biosynthetic pathway genes SlR1b1, SlPrP2, SlICS, and SlPAL. Leaf silicon levels increased but sodium levels did not significantly increase with treatment with a silicate, however potassium levels did. | [59] |

| Inorganic Compound (SeCl2) (Root) 4/6/8 mg L−1 | Capsicum annum (pepper) | Greenhouse then CE chamber in nutrient solution. Control temp 25/17 °C, high temp 35 ± 2 °C for 4 h/day then returned to control. Photoperiod was14 h. | Decreased flower dropping at all levels to lower than control. Shoot fresh weight increased for 4 mg, but increased for 6 & 8 mg. Fruit fresh and dry weight increased at all concentrations. A mass of 4 mg decreased negative vegetative effects most. Se more effective at low concentrations for vegetative growth and at high concentrations for fruit growth. | [60] |

| Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens (both foliar and root in tandem) Root: 1 mL L−1 Foliar: 3 mL L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of coco coir, irrigated with nutrient solution. No temperature control—daytime 23–28 °C, night 18–20 °C. | Growth parameters statistically significantly increased: 4.12% taller, 60.78% greater leaf area, and 2.88% larger stem diameter. Chlorophyll content (SPAD) increased by 20.9%. Both fruit weight and volume increased by 56%. Total soluble solids in fruit increased by 12%, 89% increased phenol content, 47% increase in flavonoid content, and 24% increase in EC, indicating broadly increased mineral nutrient accumulation. However, pH decreased, meaning that acidity increased. | [53] |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (Root) 3 g L−1 seed treatment | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of vermiculite, and sand and irrigated with nutrient solution, day temperatures 27 °C ± 2 °C and night >15 °C ± 2 °C. No heat stress. | Total length increased by 37. Fresh weight and dry weight increased by 666% and 83%, respectively. Developed five flowers where others had no other combined treated plants. | [47] |

| Humic Substances (humic acids, fulvic acids, and humins) (Root) 500 mg L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, autoclaved soil, and distilled water. HA applied at 500 mg/L. Heat stress of 37 °C applied for 14 h, dropped to 30 °C for 10 h. | Significantly reduced ABA content (1.5–2 fold). MDA increase was lower compared to untreated (187% compared to 385%). Increased APX, SOD, and reduced glutathione activity. | [61] |

| Humic Substances (fulvic acid) (both root and foliar in tandem) Root: 1.5 g L−1 Foliar: 1 g L−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of coco coir, and irrigated with nutrient solution. No temperature control—daytime 23–28 °C, night 18–20 °C. | Plant height increased by 7.65%, leaf area by, 41.14%, and stem diameter by 5.95%. SPAD-chlorophyll readings increased by 11.55%. Total soluble solids increased by 16%, pH was unchanged, but total phenolic and flavonoid content increased by 32% and 217%, respectively. | [53] |

| Seaweed Extract and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in tandem (root) SE: 8 g L−1 AMF: 3 g L−1 seed treatment | Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato) | Greenhouse, inert media of vermiculite, and sand and irrigated with nutrient solution, day temperatures 27 °C ± 2 °C and night >15 °C ± 2 °C. Nutrient deficiency. | Greater physiological responses than independent treatments, improved growth values. Increased protein, carbohydrate, and phosphorus content in leaves. Downregulation of electron transport rate on PSII indicating optimisation of energetic resources under nutrient deficiency. | [47] |

| Humic Acid and Bacillus cereus isolate HA: 500 mg L−1 isolate: 109 CFU mL−1 | Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) | Greenhouse, autoclaved soil, and distilled water. Heat stress of 37 °C applied for 14 h, dropped to 30 °C for 10 h. | Decreased ABA levels than each individual treatment, but increased SA. Increased amino acid content. Upregulated SlHsfA1a expression and reduced relative expression of heat stress-response genes WRKY and ATG under heat stress. Increased ion uptake (Fe, P and K). | [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gardiner-Piggott, A.; McAinsh, M.; Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Orr, D.J. The Effects of High Temperature Stress and Its Mitigation Through the Application of Biostimulants in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2742. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122742

Gardiner-Piggott A, McAinsh M, Toledo-Ortiz G, Orr DJ. The Effects of High Temperature Stress and Its Mitigation Through the Application of Biostimulants in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2742. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122742

Chicago/Turabian StyleGardiner-Piggott, Anna, Martin McAinsh, Gabriela Toledo-Ortiz, and Douglas J. Orr. 2025. "The Effects of High Temperature Stress and Its Mitigation Through the Application of Biostimulants in Controlled Environment Agriculture" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2742. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122742

APA StyleGardiner-Piggott, A., McAinsh, M., Toledo-Ortiz, G., & Orr, D. J. (2025). The Effects of High Temperature Stress and Its Mitigation Through the Application of Biostimulants in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Agronomy, 15(12), 2742. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122742