1. Introduction

The evaluation of crop varieties across multiple environments is a cornerstone of plant breeding and agronomic research [

1,

2,

3]. Crop performance rarely remains constant across locations or seasons, as genetic potential interacts intricately with environmental conditions such as water availability, soil type, and temperature [

4,

5]. Understanding these genotype × environment (G × E) interactions is therefore essential for identifying genotypes that are broadly adapted or, conversely, specifically suited to given environments [

3,

6,

7].

Traditional analysis of variance (ANOVA) [

2,

8,

9,

10] remains the primary tool to quantify main effects and interactions among genotypes, environments, and management factors. Mean plots are also employed as a visual tool to complement ANOVA results. Although ANOVA can test the significance of G × E terms, it does not reveal the internal structure of the interaction or visualize the relational patterns among varieties and environments. To address this limitation, multivariate techniques such as Correspondence Analysis (CA) [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] and biplot analysis [

14,

17] have become increasingly valuable for exploratory visualization.

Biplot methods such as the GGE biplot [

1,

5,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] integrate genotype main effects (G) and genotype × environment interactions (G × E), allowing identification of high-yielding and stable cultivars across multiple environments [

23]. However, GGE and AMMI (Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction) [

20,

24] models depend on specific experimental designs and linear modeling assumptions. In contrast, Correspondence Analysis provides a model-free geometric framework that reveals associations between genotypes and environments without requiring parametric assumptions about distributions or error variance [

11,

12,

15]. This flexibility makes CA particularly suitable for secondary or aggregated data, as often encountered in agricultural or ecological studies.

Correspondence Analysis (CA) [

11,

12,

15] is a multivariate exploratory technique that reveals the association structure between the rows and columns of a data matrix containing nonnegative values. Starting from a contingency table

F = [

fij] with

k rows and

ℓ columns, where each entry

fij denotes the observed frequency of cases classified simultaneously in row category

i and column category

j, the method transforms the data into a geometric representation. CA is applied not directly on F, but on the matrix of correspondences P = [

pij] obtained by dividing each element by the grand total

N:

This matrix represents the distribution of a total mass equal to one across the cells of the contingency table. The row and column marginal proportions are called row masses and column masses, respectively [

11,

12,

15]:

The similarity between rows (or columns) is assessed using the Benzecri’s

χ2 distance. For rows

i and

i′:

with an analogous expression for columns:

The Benzécri χ

2 distance is the fundamental metric in CA, transforming statistical dependence into a geometric concept of dissimilarity. This measure weights deviations inversely by column (row) masses, emphasizing differences in rare categories that carry greater informational value [

11,

12]. The global departure from independence is measured by the inertia, which is the analog of total variance in Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and represents the dispersion of profiles around the independence model:

This is directly related to Pearson’s

χ2 statistic:

While Pearson’s χ

2 statistic quantifies the overall deviation from independence as a single scalar value, Benzécri’s χ

2 distance decomposes this global association into pairwise distances between rows (or columns) in a common low-dimensional space, specifying where and between which categories this deviation occur. If we define the standardized residuals:

CA is carried out by performing a Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [

11,

12,

13] of the matrix of standardized residuals:

where

P is the correspondence matrix,

r = [

r1,

r2, …,

rk] is the vector of row masses,

c = [

c1,

c2, …,

cl] is the vector of column masses, and

Dr,

Dc are diagonal matrices whose elements correspond to the row and column marginal sums of

P, respectively. The SVD yields the factorial axes that maximize inertia, with the first dimension typically summarizing the major contrasts between categories.

To quantify the importance and quality of the projection of each point on the factorial axes, three complementary indices are typically reported [

11,

12,

13,

15]:

CTR (Contribution),

COR (Squared Correlation, cos

2), and

QLT (Quality of Representation). The

CTR index measures how much each point contributes to the inertia of a given dimension, identifying which rows or columns define the factorial axes. Rows (columns) points with

CTR (

i,

s) ≥ 1/k (or

CTR (

j,

s) ≥ 1/

l) are usually selected, where

k (

l) is the number of rows (columns) of the simple contingency table of two variables.

COR (cos

2) expresses how well the point is represented along that axis—high values (≥0.2) indicate reliable positioning, while

QLT summarizes the overall quality of projection across retained dimensions, with values above 0.5 indicating adequate representation.

Different normalization schemes [

25] can be adopted to modify the graphical emphasis of the analysis. Symmetrical normalization (SN) provides a balanced display of rows and columns, Row Principal Normalization (RPN) highlights the variability among rows while compressing columns near the origin, and Column Principal Normalization (CPN) emphasizes the dispersion of columns while bringing rows closer together. The Principal Normalization (PN), characteristic of the French school [

12], redistributes inertia twice—once to rows and once to columns—producing the classical “French plot”. These normalizations do not alter the underlying relationships or eigenvalues but change the scale and geometry of the factorial map, allowing complementary visual perspectives.

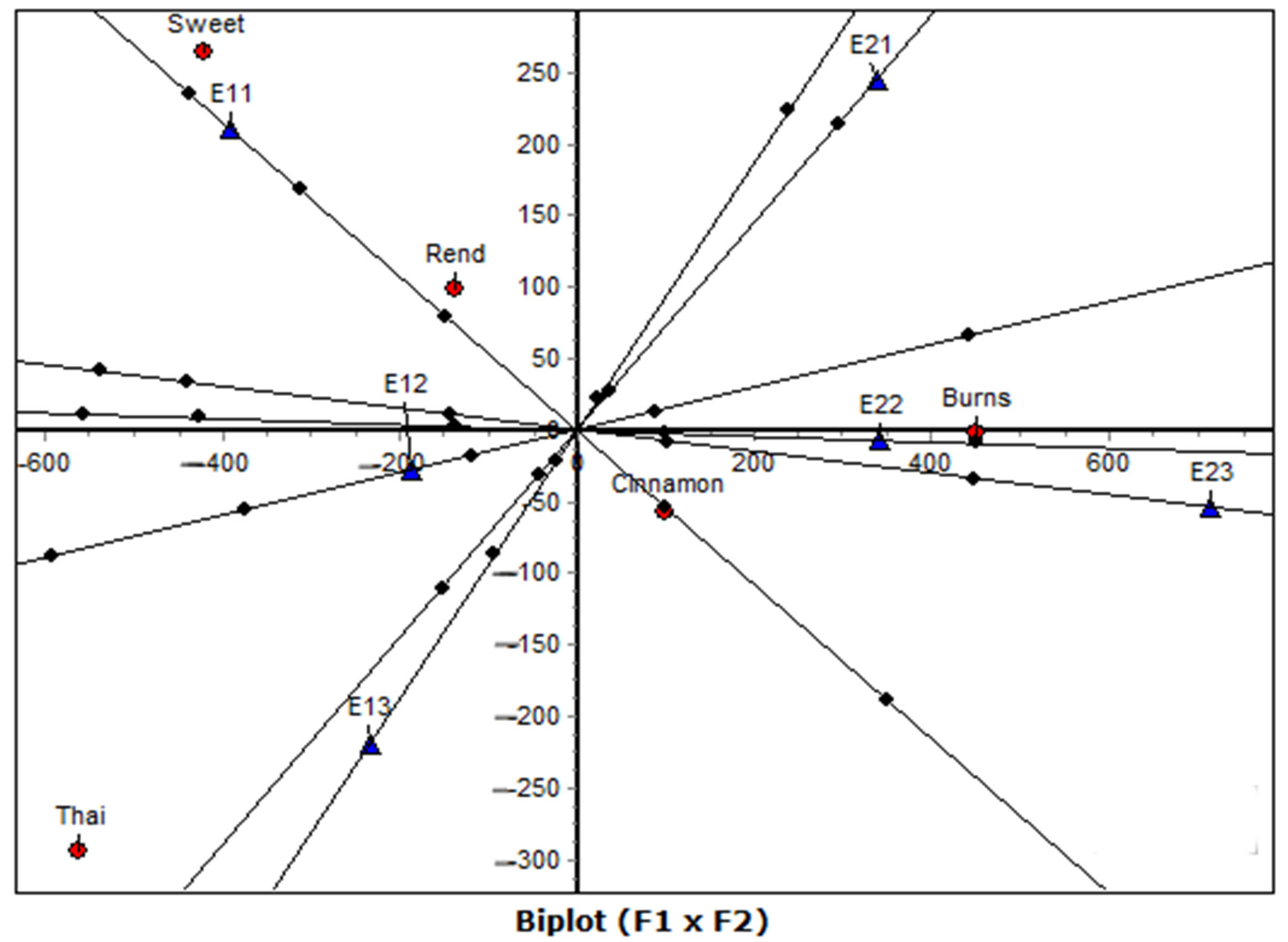

The geometric interpretation of CA relies on bi-plot axes [

12,

13]. A bi-plot axis is the straight line connecting the origin of the factorial plane with a row or column point. The opposite set of points is orthogonally projected onto this line, and the relative distances of the projections indicate the degree of association: closer projections imply stronger relationships. Thus, each axis provides a ranking of rows with respect to columns (or vice versa). The squared cosine (cos

2) of the angle formed by the axis and the point’s vector position further quantifies how well the association is represented geometrically.

Greenacre [

26] proposed a methodological adaptation of Correspondence Analysis (CA), by applying CA to the matrix of absolute frequencies rather than relative frequencies (profiles), while assigning equal weights to all rows. This approach (CA-raw) shifts the focus from proportions to absolute quantities, making the method particularly suitable for ecological, biological, and agricultural applications where total amounts or magnitudes have interpretative significance. The adjusted decomposition is given by:

which in the CA-raw adaptation becomes:

where

I, the number of rows. By preserving absolute information and assigning equal weights to rows, this approach ensures that the interaction structure is more accurately represented in contexts where quantity itself carries biological meaning.

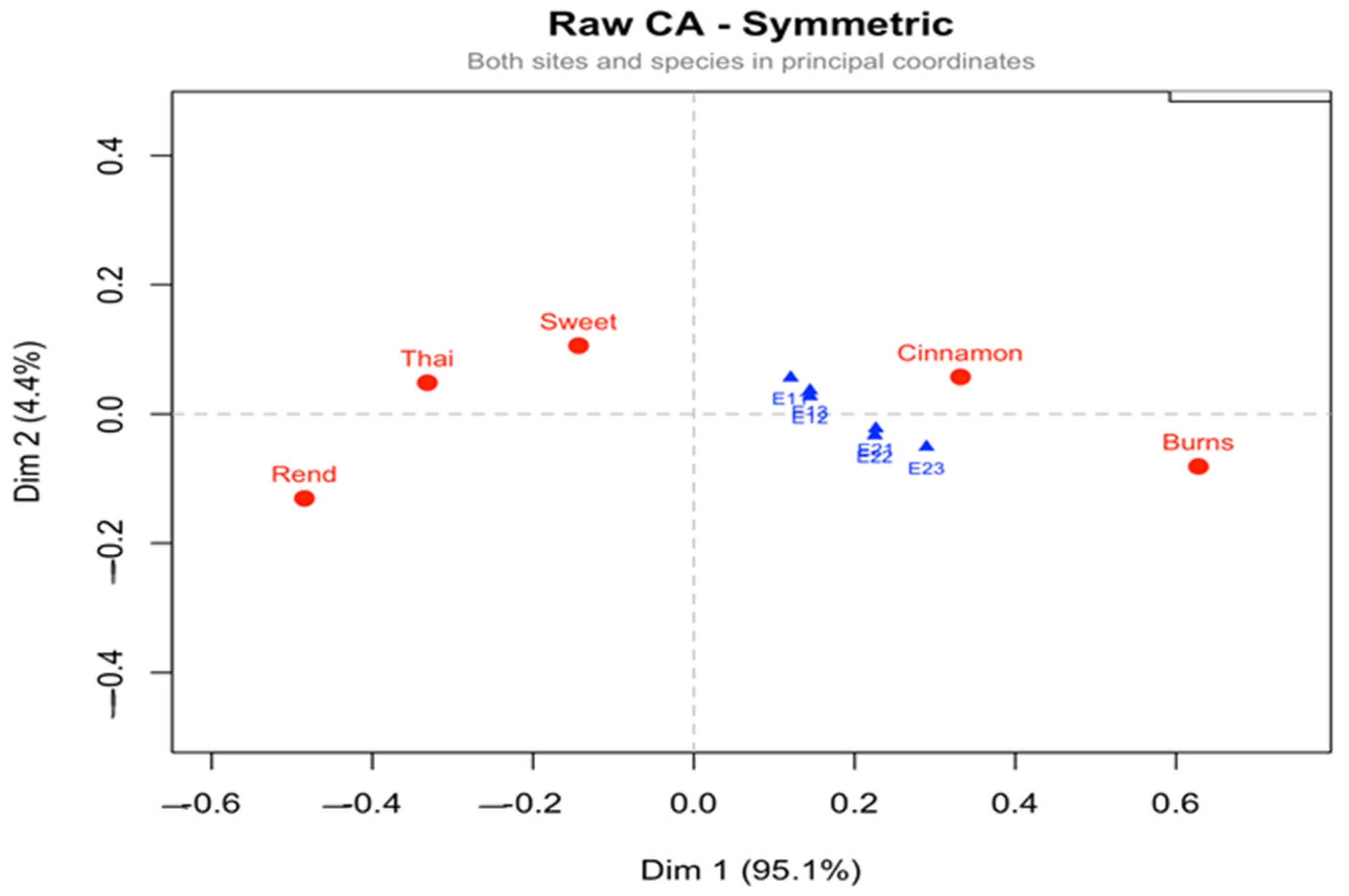

A distinctive aspect of this study is the use of Correspondence Analysis of raw data (CA-raw), following the proposal of Greenacre [

26], but with a conceptual modification. Traditionally, correspondence analysis is applied to contingency tables of absolute or relative frequencies, where rows and columns represent categorical variables and their co-occurrences. In our case, however, the data matrix consisted of quantitative yield values (total biomass per genotype × environment). Since all entries were non-negative, the matrix could be treated analogously to a frequency table, in line with the general theoretical framework of CA as outlined by Benzécri [

12] and Greenacre [

15].

The conceptual shift involved interpreting the yield values as units of frequency, for example, considering each gram of biomass as one “occurrence” in the table. To operationalize this, values were rounded to the nearest integer, thereby transforming continuous production data into a pseudo-contingency table suitable for CA decomposition. This step preserved the quantitative information embedded in the yield distribution while allowing the use of the CA algorithm in a way consistent with frequency-based interpretation.

Both the standard CA and the CA-raw used in this paper therefore represent modified applications. In the standard CA, normalization procedures (symmetrical, row-principal, column-principal) rescale the data into relative profiles and highlight association structures. In the CA-raw, decomposition is applied directly to the rounded yield matrix with equal row weights, which emphasizes absolute differences in production while retaining the correspondence framework.

Genotype × environment (G × E) interactions [

1,

3,

4,

5,

19,

22,

23,

24] are central to the evaluation of crop performance and stability. A widely adopted approach in this field is the GGE biplot, which integrates genotype main effects (G) and genotype × environment interactions (G × E) to facilitate the visual identification of high-yielding and stable genotypes across environments [

17,

21,

22]. While powerful, the GGE biplot is primarily tailored to yield-based data structures [

21,

22]. In contrast, Simple Correspondence Analysis (CA) [

11,

12,

13,

15] and its raw variant (CA-raw) [

26] provide a broader multivariate framework that emphasizes the association structure between genotypes and environments, accommodating different normalization schemes (row, column, symmetrical, and principal). By combining ANOVA, mean performance plots, and CA approaches, this study offers an alternative analytical perspective that complements the insights typically derived from GGE biplot analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

The dataset used in this study was derived from field experiments, based on RCBD, conducted during two growing seasons, 2015–2016 (Year 1) and 2016–2017 (Year 2). A total of 120 observations were recorded on basil plants (

Ocimum basilicum) grown under controlled irrigation treatments. Five varieties were included in the trials: Mrs Burns Lemon, Cinnamon, Sweet, Red Rubin, and Thai [

27,

28,

29]. Irrigation was applied at three levels, corresponding to 40%, 70%, and 100% of the full water requirement. The experimental layout followed a factorial structure, combining variety, irrigation level, and year. Plant growth was evaluated at three developmental stages. For the purpose of this study, we focused on the third stage of development, analyzing dry weight as response variables (

Table A1 in

Appendix A).

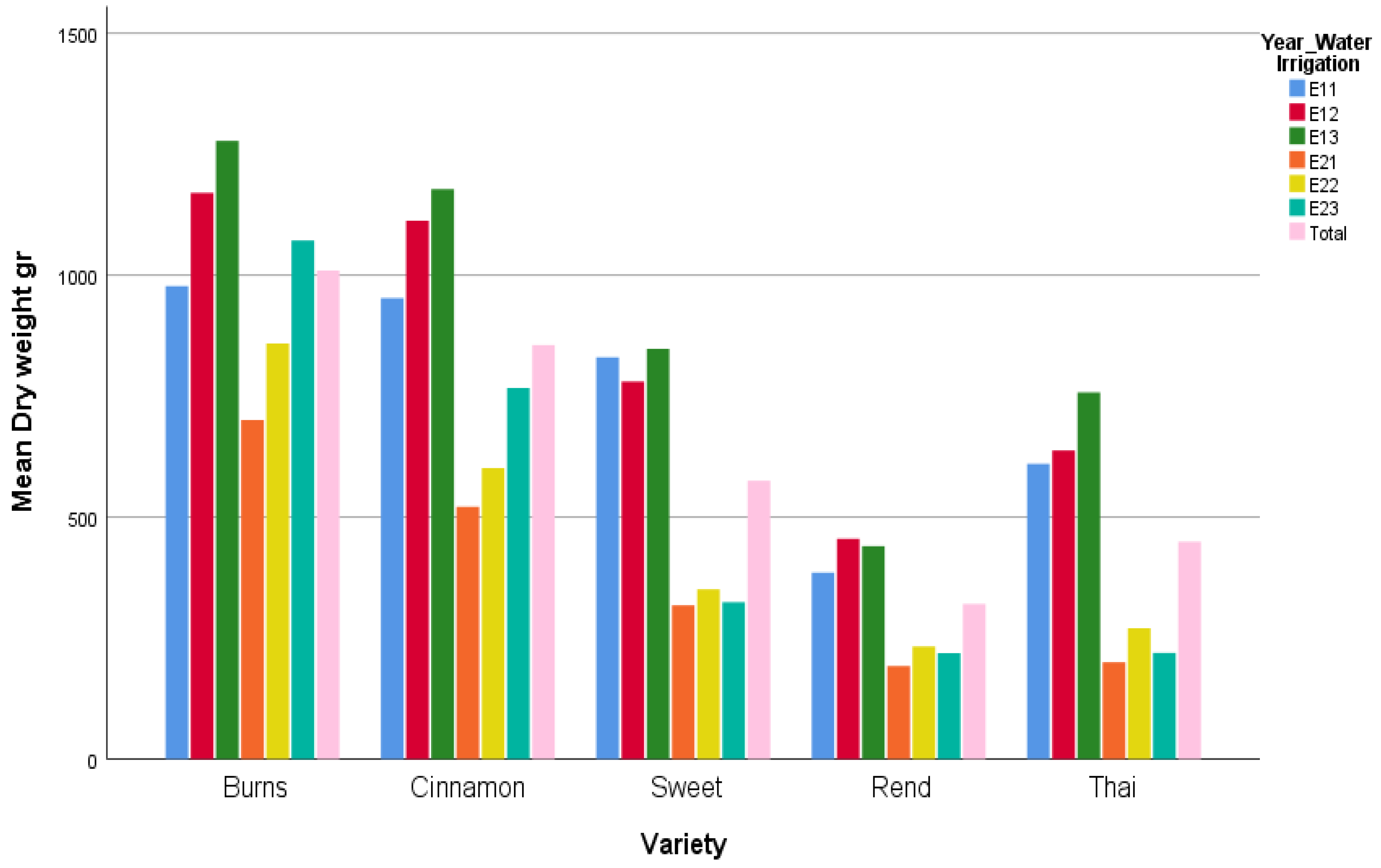

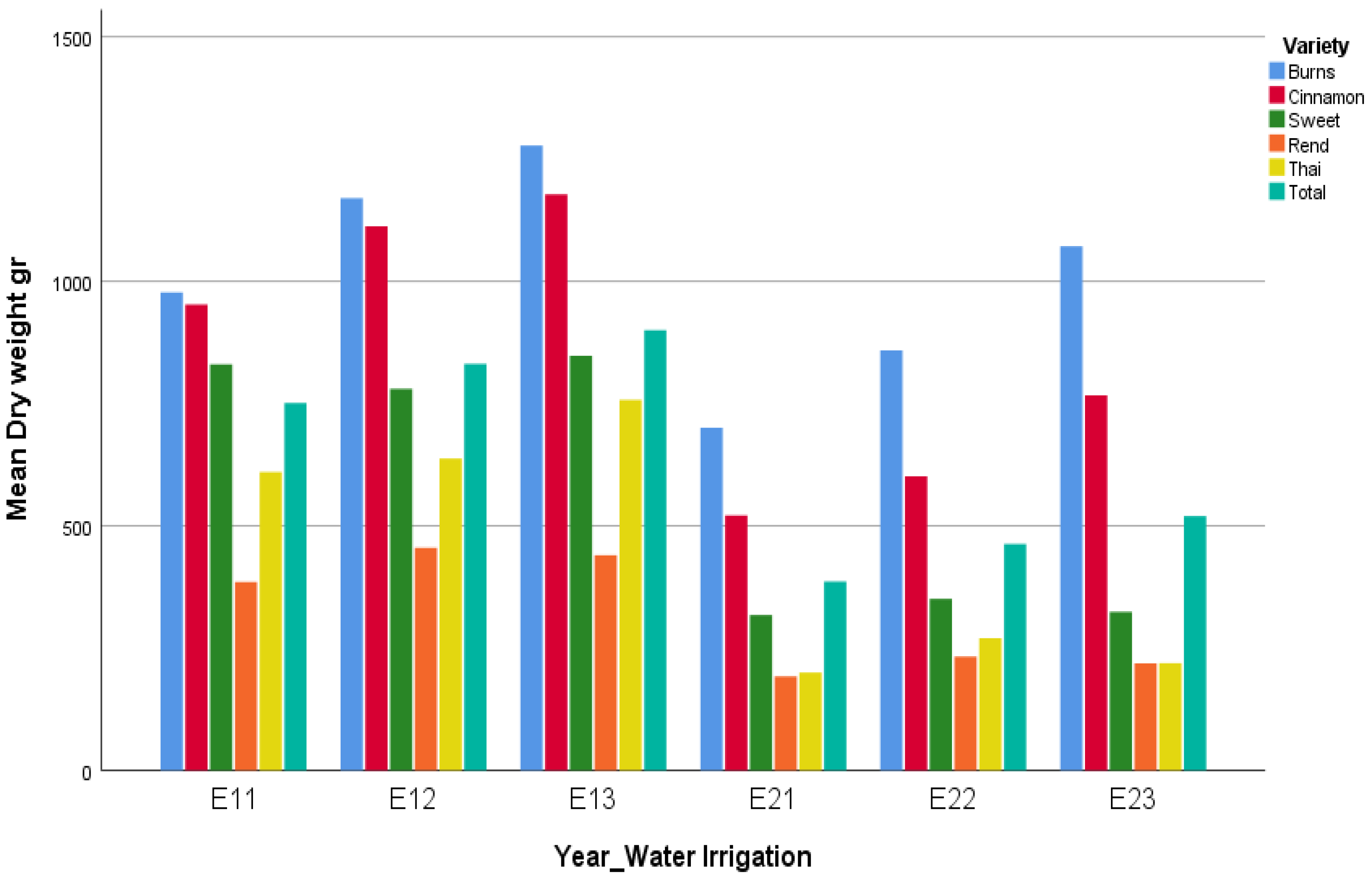

In the context of this study, the environmental factor was defined as the combination of year and irrigation level. Thus, six environments were considered in total: Y1_W1 (E11), Y1_W2 (E12), Y1_W3 (E13), Y2_W1 (E21), Y2_W2 (E22), Y2_W3 (E23). This definition allowed the joint assessment of yearly climatic variation and irrigation management as a single composite environmental factor. Such an approach provides a more comprehensive framework for evaluating genotype × environment interaction (G × E), since both temporal and water availability effects were integrated.

To assess the effect of the experimental factors, a factorial combined over years ANOVA model was applied, including the main effects of variety, irrigation level, and year, as well as their interactions. Significance was tested using

F-tests, and effect sizes were quantified using partial eta-squared (

η2). Partial eta squared (

η2 partial) is a statistical measure used in analysis of variance (ANOVA) to estimate the proportion of the total variance explained by an independent factor, taking into account only that specific effect and no other possible effects. Partial

η2 is calculated as [

30]:

where

SS_effect is the sum of squares for the factor’s effect and

SS_error is the sum of squares for the experimental error. Within the epistemological frame of Social Sciences and according to Cohen [

30], values of

η2 close to 0.01 or smaller indicate a small effect of the factor, values around 0.06 indicate a medium effect, and values of 0.14 or higher indicate a large effect of the factor. Unfortunately, there are no such norms within the frame of Agricultural Sciences.

To visualize differences among factor levels, mean plots were constructed for varieties and for the combined effect of year × irrigation level. These plots provide an exploratory representation of treatment means and possible interaction patterns. In addition to the conventional correspondence analysis (CA) applied on contingency tables, we adopted an extended approach suitable for quantitative agronomic data. Following the seminal contributions of Benzécri [

12], who argued that CA can be generalized to any matrix of positive entries and not only to frequency tables, we implemented a conceptual shift in the treatment of yield data. Specifically, dry biomass values were interpreted as frequency-like units of performance, thereby allowing the construction of a data matrix amenable to CA decomposition. To ensure compatibility with the algorithm, decimal values were rounded to integer units, reflecting the interpretation of yield as counts of productivity events.

This adjustment was applied consistently in two ways. First, in the standard CA framework (with symmetrical, row-principal, and column-principal normalizations), the performance matrix was processed as if it were a contingency table, thereby extending the scope of CA beyond its classical domain. Second, in the CA-raw version, we followed Greenacre’s proposal, applying singular value decomposition directly to the absolute frequency-like matrix with equal row weights. This modification preserved the quantitative information of yield while maintaining the formal structure of CA.

In this sense, both approaches were “re-engineered” to accommodate agronomic yield data, transforming CA from a tool of categorical association into an exploratory method for genotype × environment interactions. This methodological innovation constitutes a central contribution of the present study.

Together, these approaches provide complementary perspectives on the relationships between varieties and environments, extending beyond the results of the factorial ANOVA. This variant enhances the biological interpretability of genotype × environment structures, particularly in contexts where absolute magnitudes carry agronomic meaning.

All analyses were performed using standard statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics v26 and CHIC Analysis [

31].

4. Discussion

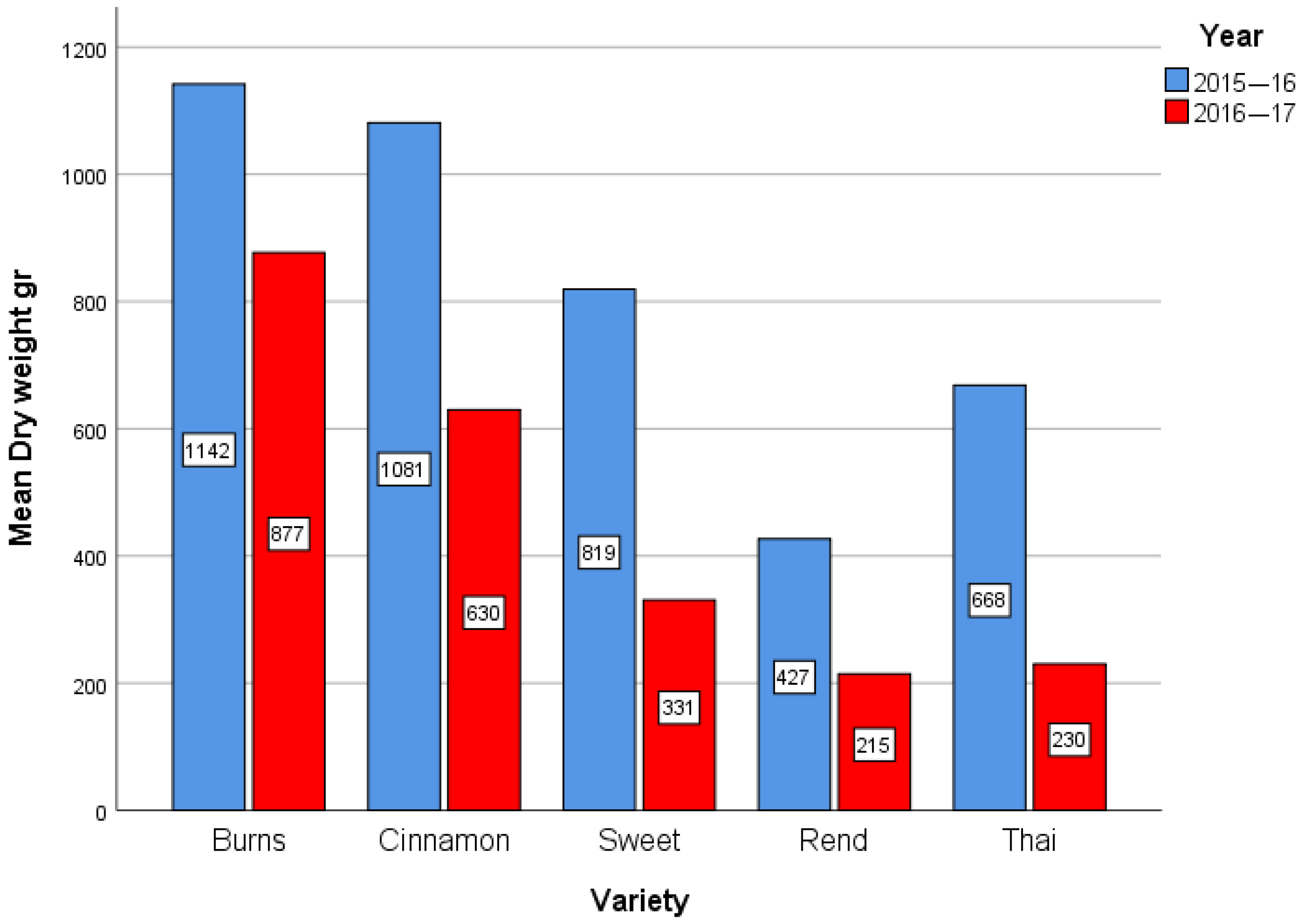

The present study provides new insights into the genotype × environment (G × E) interactions of basil varieties by combining classical ANOVA with correspondence analysis under different normalization schemes. The ANOVA clearly demonstrated that both year and variety effects were the dominant sources of variation in biomass, while irrigation had only a secondary role. This indicates that under the tested irrigation regimes, seasonal factors such as temperature, light, and cumulative growing degree days exerted a stronger influence than water availability per se. Nevertheless, the significant Variety × Year interaction highlights that genotypic responses were not uniform across seasons, emphasizing the importance of multi-environment evaluation for basil breeding and cultivation.

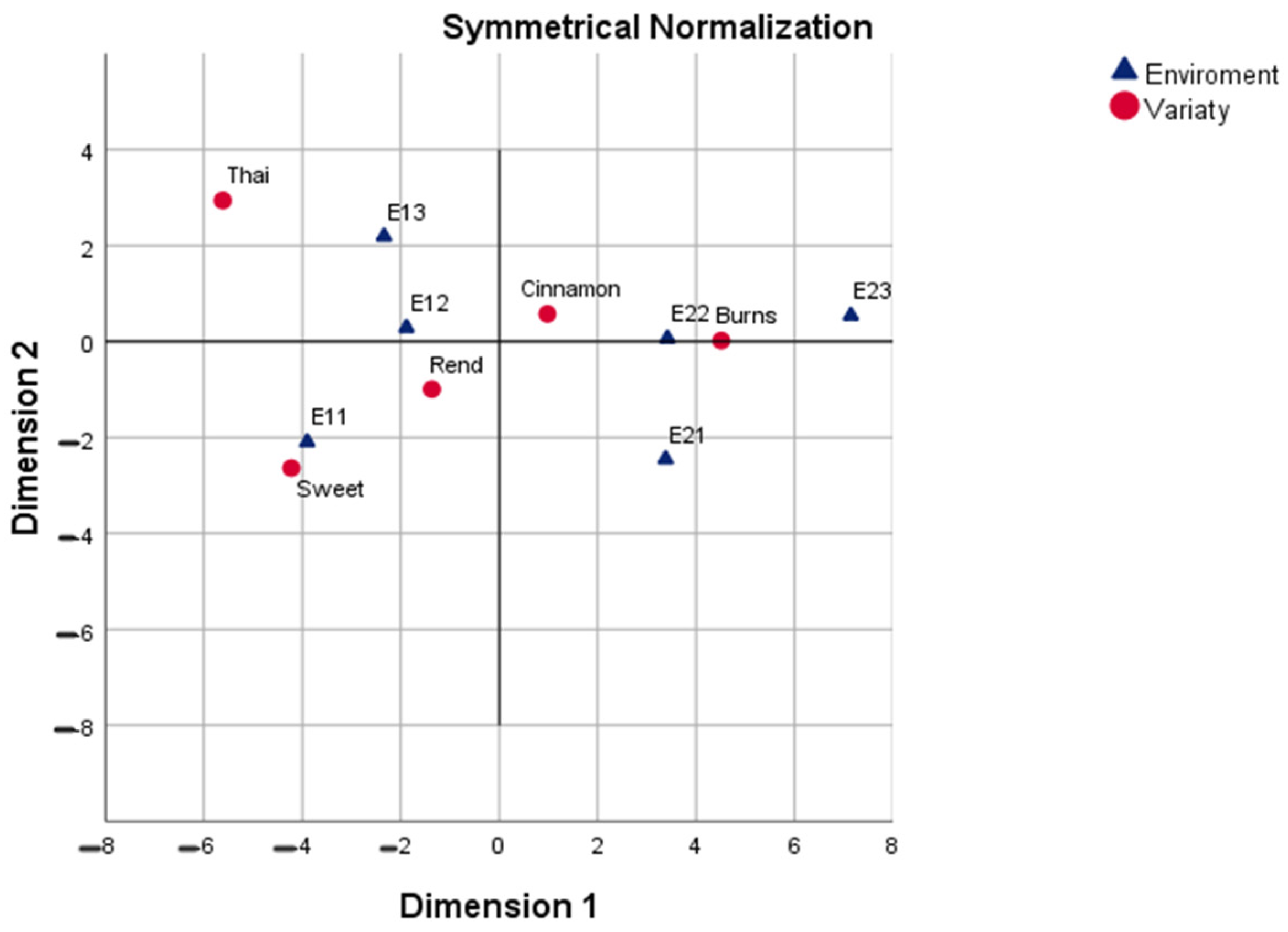

The correspondence analysis further refined the interpretation of these patterns by explicitly linking varieties with their most favorable or limiting environments. Under symmetrical normalization (CA-SN), which balances the interpretation of rows and columns, Burns was consistently aligned with second-year environments under full irrigation, reflecting its superior adaptability and responsiveness to favorable growing conditions. Conversely, Sweet and Thai were linked with first-year environments, suggesting that their performance is less sensitive to favorable inputs and possibly better suited to more stressful conditions. Rend and Cinnamon occupied intermediate positions, reflecting more generalized response patterns. This symmetric representation thus provided a holistic picture of both varieties and environments, highlighting clear polarities that underpin the G × E interaction structure.

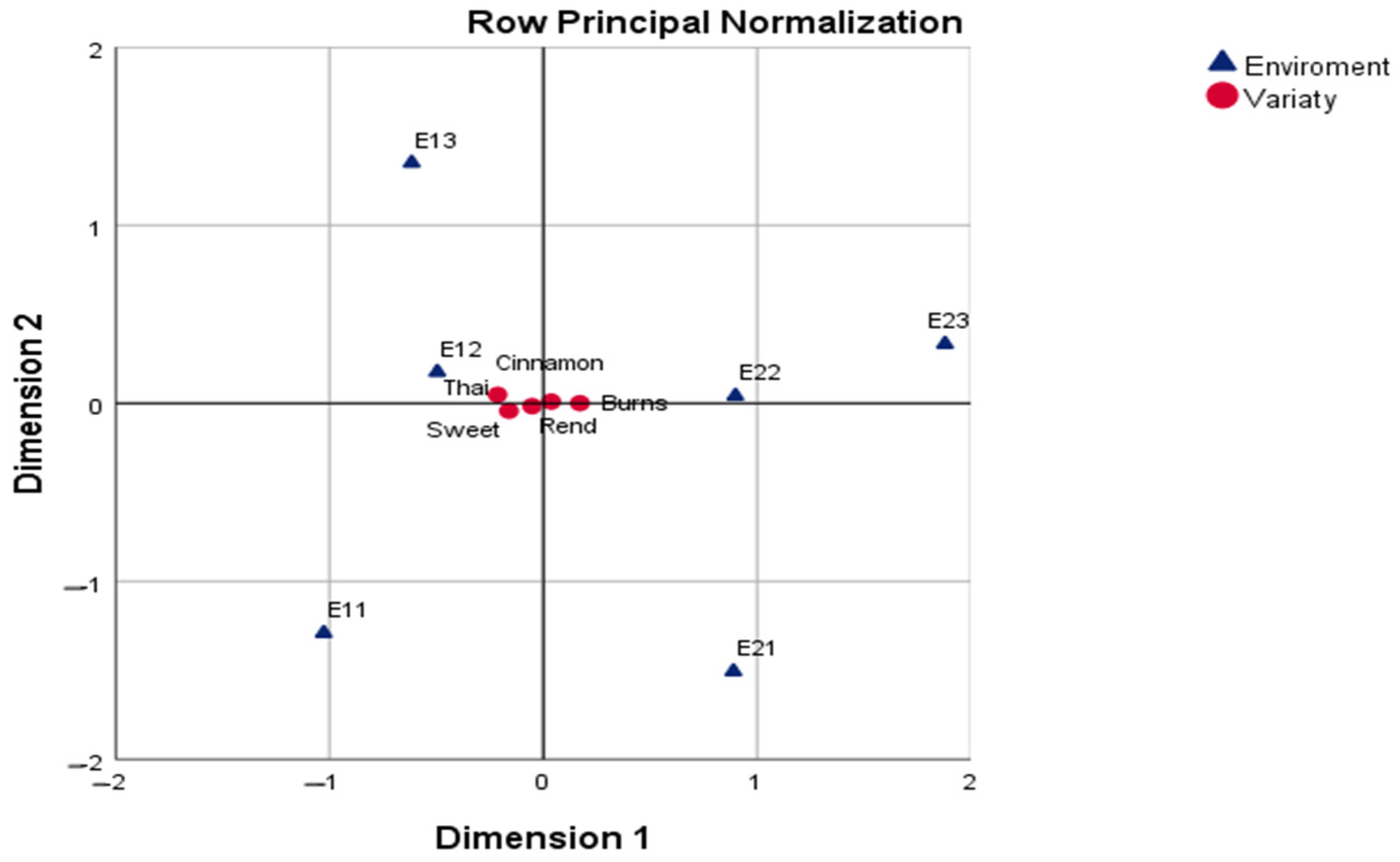

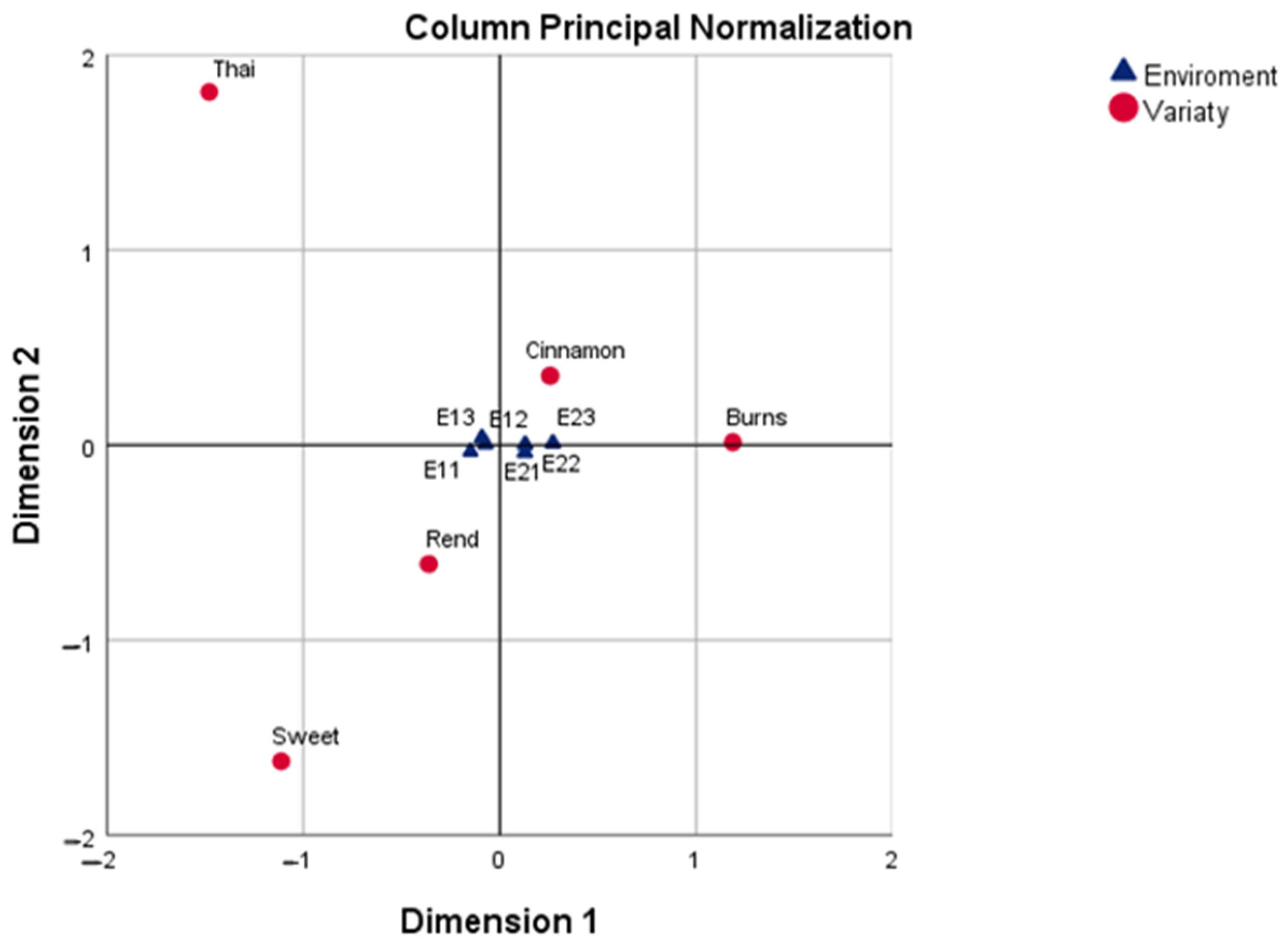

The row principal normalization (CA-RPN) emphasized varietal profiles, but the clustering of genotypes around the centroid indicated that the varieties themselves were less sharply differentiated than the environments. Here, Burns and Cinnamon again tended toward the favorable side of the first axis, while Sweet and Thai occupied the opposite pole, consistent with the SN solution but in a more compressed representation. This configuration is useful when the research objective is to compare genotypes directly, but it provides less information about environmental structuring.

By contrast, the column principal normalization (CA-CPN) placed environments at the center of the analysis, showing that E21–E23 formed a coherent cluster of favorable conditions, while E11–E13 represented contrasting, less productive environments. The varieties were projected accordingly, with Burns and Cinnamon strongly aligned with the positive pole (E21–E23) and Sweet and Thai with the negative pole (E11–E13). Rend remained near the centroid, reflecting its lack of strong specificity. This solution is particularly useful for identifying discriminating environments that can be employed in future breeding trials to reveal varietal differences efficiently.

Beyond its descriptive power, CA provides diagnostic measures—contribution (CTR), correlation (COR), and quality of representation (QLT)—that help assess the stability and reliability of the projected points. In this study, only dimensions and points with

QLT > 0.50 and

COR > 0.20 were interpreted, following Greenacre [

15]. These criteria ensure that conclusions are based on geometrically well-represented points and not on random low-variance patterns.

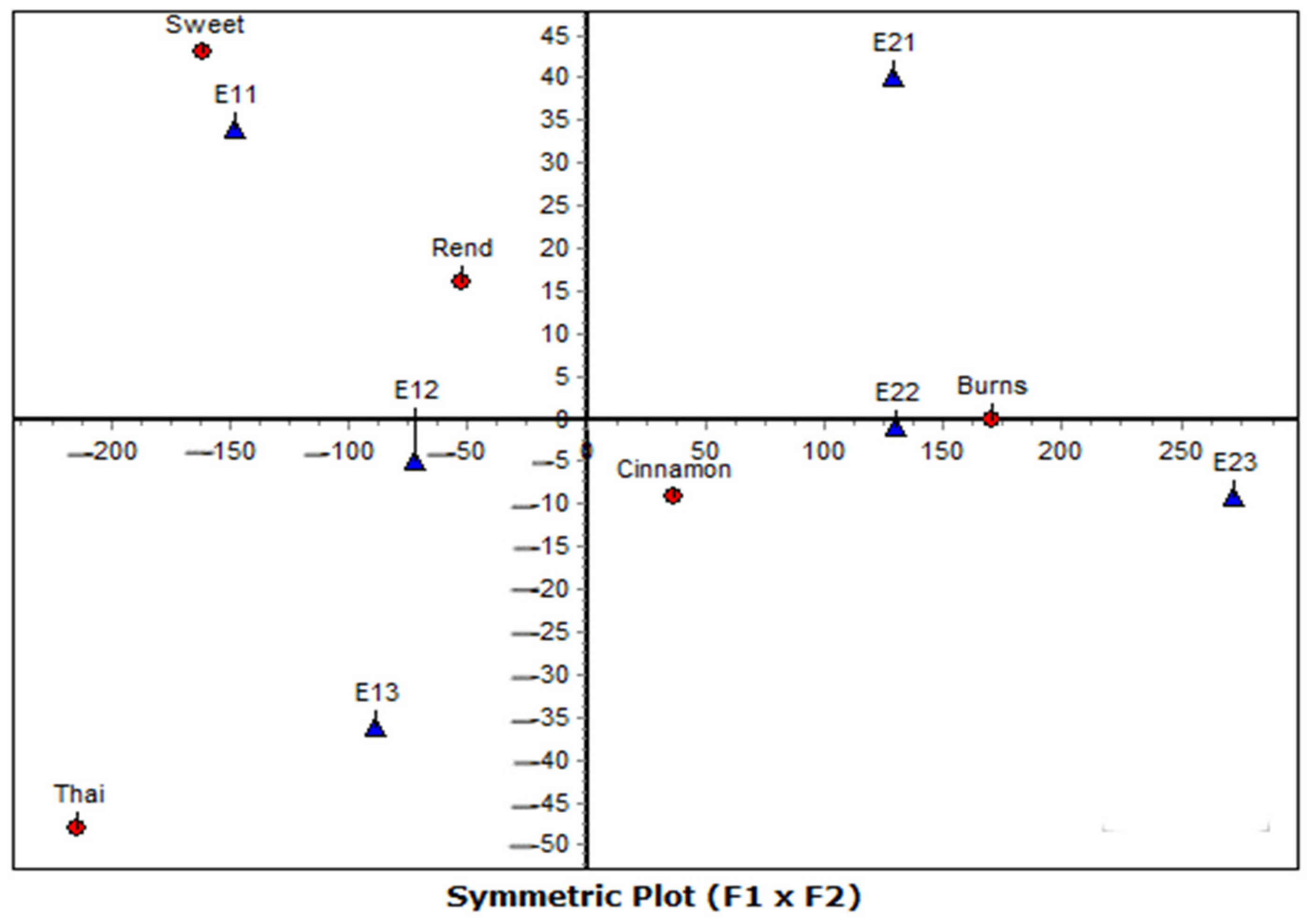

The Correspondence Analysis of raw data (CA-raw) provided the most striking contrasts, with the first axis alone capturing over 95% of the inertia. Compared with the normalized solutions, CA-raw stretched the configuration, thereby amplifying the major differences between genotypes and environments. This revealed clearer polarities, particularly the alignment of Burns with high-yielding environments versus Thai and Rend with low-yielding ones. While normalized CA is useful for balanced interpretation, the raw approach is valuable when the primary goal is to expose dominant structures in the data with maximum clarity.

In addition to the overall stretching effect of CA-raw, the decomposition of row and column inertias clarified which varieties and environments were most influential in shaping the factorial map. The varieties Burns and Rend emerged as the principal drivers, each contributing disproportionately to the first dimension, whereas Sweet remained centrally located with minimal inertia, indicating its more neutral profile. On the environmental side, Year 1 conditions (E11–E13) accounted for the highest inertias, confirming that temporal effects dominated the factorial solution. By contrast, the environments of Year 2 contributed relatively less, with E23 in particular exerting minimal influence on axis formation. These results reinforce the earlier conclusion that the CA-raw captures dominant structures with maximum clarity, but also show that the contrasts are not evenly distributed, they are concentrated around specific variety–environment combinations that polarize the map.

CA-raw is especially valuable when the research aim is to identify which factors drive the strongest divergences, rather than to maintain a balanced representation of all categories. In this context, the method provided sharper insights into the interaction structure, revealing that the primary contrast is defined by Burns under favorable (Year 1) environments versus Thai and Rend under less productive (Year 2) environments.

From a biological perspective, the results consistently show that Burns Lemon is the most stable and high-performing genotype, capable of exploiting favorable environments such as Year 2 under full irrigation. Cinnamon displayed broader adaptability, performing moderately well across environments without the strong specificity of Burns. Sweet and Thai, on the other hand, were more environment-dependent, performing relatively better under the harsher first-year conditions but lacking consistency under more favorable ones. Rend emerged as a low-yielding and non-discriminating genotype, with no clear adaptation pattern. These findings highlight the diversity of adaptive strategies within basil and suggest that breeding for high yield and stability could prioritize Burns and Cinnamon, whereas Sweet and Thai may be better suited for stress-prone environments or niche cultivation.

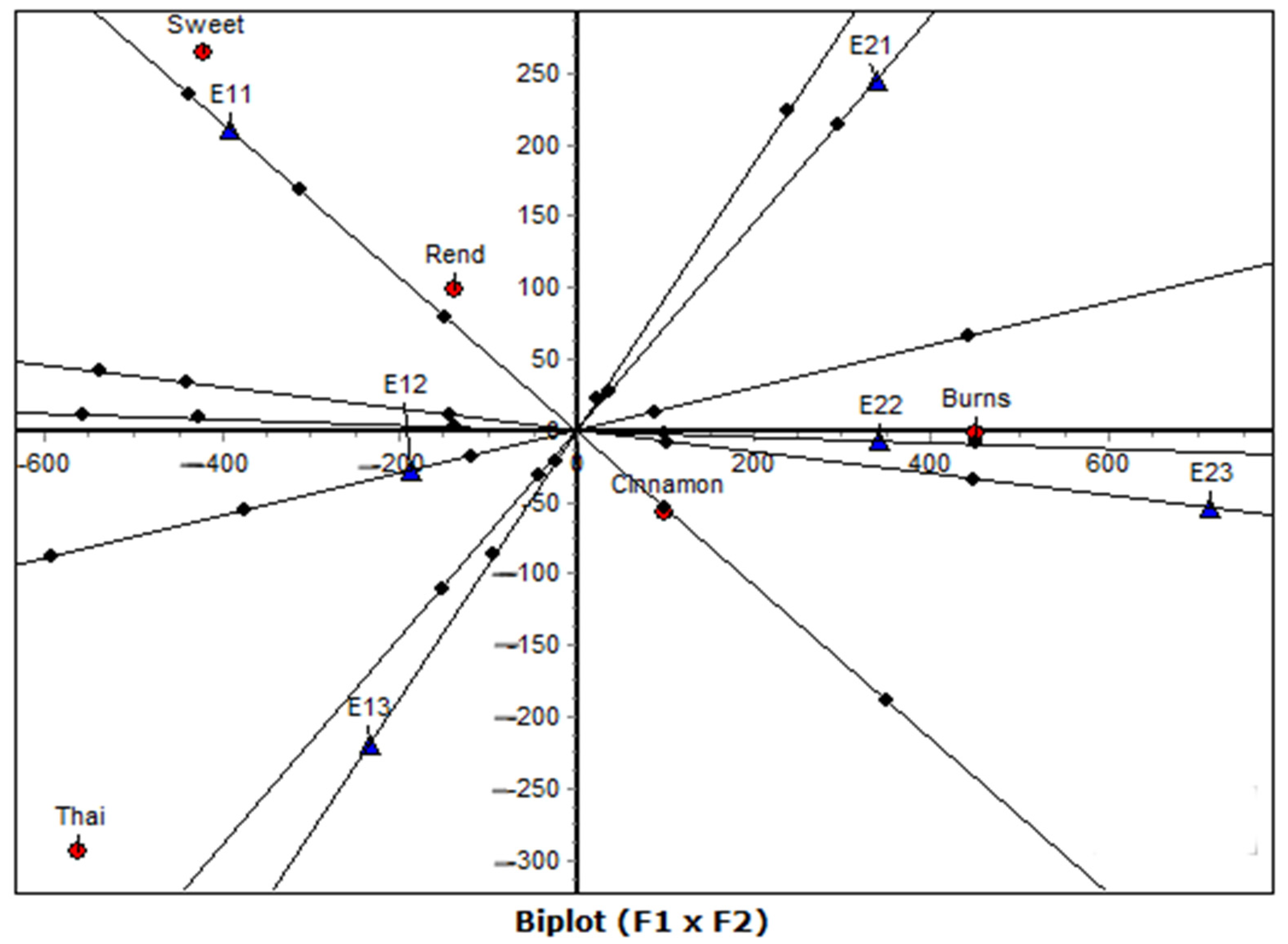

Beyond the conventional factorial maps, the biplot-axis analysis provided a finer quantitative interpretation of genotype–environment associations through the examination of distances and squared cosine (cos2) values. This complementary step transforms the graphical representation into a numerically grounded ranking system, allowing the identification of the most influential pairings. In this study, the Burns–E22 and Burns–E23 associations exhibited the highest cos2 values (≥0.99), confirming that these environments were most representative of the genotype’s performance profile. Similarly, Cinnamon showed strong associations with both early (E11) and late (E22–E23) environments, reflecting its wider adaptability. Conversely, Thai and Rend displayed high cos2 values for specific, less favorable environments (E13 and E21), indicating narrow adaptation and environmental sensitivity.

The biplot-axis framework, provides two complementary advantages. First, it quantifies the proximity relationships suggested visually in the factorial map, enhancing interpretability and reproducibility. Second, it distinguishes between geometric closeness (small Euclidean distance) and representational quality (high cos2), thereby clarifying which genotype–environment pairs are truly meaningful rather than coincidental. By combining these two measures, the analysis yields a more robust interpretation of adaptability, stability, and specific interaction patterns. This approach is especially valuable in agronomic datasets with moderate replication, where visual inspection alone may lead to over-interpretation.

In this context, the biplot-axis analysis reinforced the geometric conclusions from both CA and CA-raw, confirming that Burns and Cinnamon are the most stable and discriminating genotypes, while Sweet and Thai exhibit higher environmental dependency. The convergence of graphical and quantitative evidence underscores the reliability of the correspondence analysis framework for dissecting G × E interactions.

An important aspect emerging from this study is the contrast between model-based and model-free approaches for analyzing G × E interactions. GGE biplots and AMMI models [

20,

24] remain the standard tools for breeders, as they allow the partitioning of variance into main and interaction effects, while also enabling formal statistical testing. However, their reliance on specific experimental designs, linear model formulations, and distributional assumptions constrains their applicability, particularly when only aggregated or published datasets are available. By contrast, the CA-based solutions presented here are inherently model-free, relying solely on the geometric decomposition of the data matrix. This independence from model structure enhances flexibility and robustness, while also extending applicability to contexts where raw data are unavailable. Moreover, CA-based maps and rankings provided interpretable insights into both varietal and environmental contributions, often aligning with, but also complementing, the patterns revealed by GGE or AMMI.

Together, these findings suggest that CA methods should not be viewed as substitutes but rather as complementary alternatives: GGE and AMMI remain indispensable for hypothesis-driven inference, whereas CA offers a versatile exploratory framework that excels in visualization, ranking, and secondary data analysis.

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

While the proposed Correspondence Analysis (CA) adaptations proved effective for revealing genotype × environment structures, some methodological limitations should be acknowledged. CA is inherently sensitive to extreme or unbalanced values, as large deviations in row or column totals can disproportionately affect the χ

2 distances and hence the geometric configuration. Although this effect was mitigated here through the rounding and scaling procedures applied in the CA-raw transformation, outliers may still influence the position of points with small masses. Furthermore, the interpretation of low-explained-variance dimensions should be treated with caution. These secondary axes often capture minor residual structures, which, although potentially meaningful, may not be statistically robust. As recommended by Greenacre [

15], only dimensions with substantial inertia contributions and satisfactory quality of representation (QLT > 0.50, COR > 0.20) were considered in this study. Finally, the model-free nature of CA implies that results are exploratory rather than inferential, emphasizing relational geometry rather than hypothesis testing. Despite these limitations, the complementary use of CA-raw and normalized CA provides a robust and interpretable framework for exploratory G × E analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that both seasonal conditions and genetic background are the dominant determinants of basil biomass, with irrigation playing only a secondary role within the tested range. Among the evaluated varieties, Burns Lemon consistently outperformed the others and showed the strongest association with favorable environments, while Cinnamon exhibited broad adaptability across environments. By contrast, Sweet and Thai were more environment-dependent, aligning with less favorable conditions, and Rend displayed low and non-specific performance.

The application of correspondence analysis under multiple normalization schemes provided complementary perspectives on the genotype × environment interaction structure. Symmetrical normalization offered a balanced view of varieties and environments, row and column normalizations highlighted specific profiles, and raw CA amplified the dominant contrasts, yielding sharper discrimination. Importantly, the factorial projections allow not only visualization but also a ranking of varieties across environments and, conversely, of environments relative to each variety, offering interpretable and actionable insights.

Taken together, these findings suggest that Burns Lemon and Cinnamon are promising candidates for breeding programs targeting yield stability, while Sweet and Thai may be better suited to stress-prone or marginal environments. Moreover, the integration of raw and normalized CA approaches with classical ANOVA represents a powerful framework for the analysis of complex G × E datasets in basil and potentially other aromatic crops.