3.1. Chemical Compositions

Soil pH is the main factor defining the decomposition of soil organic matter, among others, because it influences the composition and activity of microbial communities, including enzyme activity, and also defines the mechanisms of SOM stabilization and destabilization [

26]. According to the authors, the highest values of the effects of accelerating the decomposition of soil organic matter were common in soils with a pH between 5.5 and 7.5. In the humus horizon, the pH of the tested haplic luvisol ranged from slightly acidic to neutral and was within the pH range enabling the decomposition of organic matter. The total organic carbon (TOC) content ranged from 5.96 to 10.05 g kg

−1 (average 7.90 g kg

−1) in the soil samples collected in the first year of the study. In the next year, its content decreased on average by about 10% and ranged from 5.51 to 8.26 g kg

−1 (

Table 2).

The tested soil was classified as very low TOC soil, according to the European Soil Database [

27]. Organic matter in the soil, both natural and introduced in fertilizers, and its products resulting from the activity of microflora and mesofauna have a beneficial effect on the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil [

28]. The low organic matter content in Polish soils is primarily due to climatic and soil conditions. The main factor is drought, which inhibits the inflow of organic matter and slows the mineralization process due to water shortages in the soil [

29]. With increasing foliar fertilizer application, a decrease in the average content of both the TOC and TN was observed. The highest TOC content (10.05 g kg

−1) was determined in the treatments fertilized with the highest dose of ammonium nitrate (N

80). Similar relationships were observed in the soil. A trend of decreasing TOC content by approximately 10% and TN content by approximately 7% was also observed in the second year of the study (2022).

The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is an indicator of the degree of organic matter decomposition. In the tested soil, the C:N ratio in the topsoil was approximately 10, indicating natural mineralization. Sulfur release from soil organic compounds occurs when the C:S ratio in the substance being decomposed by microorganisms is less than 200. The N:S ratio in soils is considered an indicator of the availability of sulfur for plants [

30]. Typically, the N:S value in soils is in the range of 6.7–11.1:1. According to Brady et al. [

31], the C:N:S ratio, as an indicator describing the possibility of releasing sulfur from organic matter in mineral soils, should be 100:8:1. In the analyzed soils, the C:N:S ratio value was almost half lower than the optimal conditions enabling the mineralization of sulfur from organic matter, which indicates a low content of available sulfur in the tested soil.

In the soil environment, S occurs in significant amounts in the organic form (95–98%) [

32], but plants take up S in the form of sulfate [

31]. In soils, inorganic sulfur can occur in various oxidation states from −2 to +6 as: sulfide (S

2−), elemental sulfur (S

0), thiosulfate (S

2O

32−), tetrathionate (S

4O

62−), sulfite (SO

32−) and sulfate (SO

42−). Biological oxidation of hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) to sulfate (SO

42−) is the main S transformation in the biogeochemical sulfur cycle [

33,

34]. Prokaryotes primarily oxidize reduced inorganic sulfur, and the main by-product of this oxidation is SO

42− (VI). Microbes are primarily responsible for the mineralization, immobilization, oxidation, and reduction processes occurring in soil when sulfates are converted to other forms [

34,

35]. Under the soil and climatic conditions of Poland, the total sulfur content in mineral soils not subject to significant anthropogenic pressure generally does not exceed 2 g·kg

−1 [

36]. The sulfur content in the tested soils was in the range of 0.136–0.186 g·kg

−1 of soil. According to the classification of limiting sulfur content in the surface layer of soils (0–20 cm), the tested soils belonged to the category of soils with medium total sulfur content, which indicates that they are not enriched with sulfur from anthropogenic sources [

36].

In the first year of the study, the total sulfur content was approximately 8% higher than in the following year, and the effect of fertilization on its content was observed (

Table 3). The highest sulfur content—0.178 g·kg

−1 soil—was determined in soil collected from the plot fertilized with the highest dose of nitrogen—N

80. A higher total sulfur content was found in plots where lower doses of foliar fertilizer were applied. In the first year of the study, the highest sulfur content was found in soil collected from plots without foliar fertilization and after application of Multi-N

50%.

In the second year of the study, however, no effect of either soil or foliar fertilization on the total sulfur content in the soil was observed. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on soil sulfur content is multifaceted, as confirmed by numerous studies [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] Nitrogen application may limit the availability and transformation of sulfur in the soil, which is crucial for yield and quality. According to Lošák et al. [

37] and Suran et al. [

38], increasing nitrogen doses may lead to better sulfur uptake by plants, as observed in studies on onion and maize.

No effect of fertilization on the sulfate sulfur content in the studied soil was observed (

Table 3). A reduction of approximately 3% in the available sulfur content in the soil was observed in the second year of the study. The sulfur contained in the applied foliar fertilizer, in the form of sulfur trioxide and elemental sulfur, most likely intensified the processes of yield development and improved its quality, which is related to the low sulfate (VI) content for plants.

According to the proposed limit values [

12] for sulfate sulfur content in mineral soils, the tested soils with an average sulfur content of 4871 mg·kg

−1 in 2021 and 4731 mg·kg

−1 in 2022 are classified as soils with very low SO

42− content. According to Lipiński et al. [

12], the tested soil for growing

Brassicace plants should be enriched with sulfur at a dose of 100 kg·ha

−1. Nitrogen fertilization can increase the sulfur availability, while excess nitrogen without adequate sulfur can lead to imbalances, potentially worsening the soil conditions and crop quality in the long term. This highlights the importance of balanced fertilization strategies in agricultural practices.

3.2. Mustard Seed Yield

A significant effect of the different nitrogen levels of fertilization on white mustard seed yield was found (

Table 4). The highest average seed yields were obtained after soil application of 80 kg N·ha

−1—3.15 and 3.19 kg·plot

−1. These yields were higher by 21.6 and 18.6%, respectively, compared to treatments obtained using 40 kg N·ha

−1. When replacing part of the soil nitrogen dose with foliar fertilizer, a higher seed yield, in the first and second years of the study, was harvested from treatments where 50% of the total nitrogen dose was replaced with foliar fertilizer. The differences were 2.8 and 9.0%, respectively. The yield-forming effect of this dose was comparable to that of soil-applied nitrogen at 60 kg·ha

−1. Obtaining a seed yield of the highest quality requires a modern approach to fertilization. It is important to note that drought conditions often occur during plant development, making applying nitrogen to the soil pointless. Ammonium nitrate dissolves very easily, but at high temperatures it gasifies and evaporates. Complete elimination is not possible, but losses can be minimized through foliar fertilization.

Climatic conditions, particularly water availability during the vegetation period, exert a decisive influence on the efficiency of nitrogen fertilizer utilization and the yield performance of white mustard (Sinapis alba L.). The 2021 growing season, characterized by a higher cumulative precipitation, promoted improved nutrient uptake by plants and enhanced the utilization of the applied nitrogen. In contrast, the water deficit recorded in 2022 during critical developmental stages—especially flowering and seed filling—restricted both nitrogen mineralization in the soil and its translocation within the plant. Consequently, water availability constitutes a key determinant of nitrogen use efficiency. Moreover, the partial substitution of soil-applied nitrogen with foliar application appears to be an effective agronomic strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of water stress on seed yield and quality, as evidenced by the results obtained in this study.

The sulfur present in the applied foliar fertilizer probably also contributed to the increase in mustard seed yield. According to Szulc [

39], the high yielding efficiency of sulfur can only be achieved under conditions of its deficiency. The yield of cultivated plants is determined, among other things, by the interaction of sulfur and other fertilizer components. Among the studies addressing this issue, most concern the effect of sulfur and nitrogen interactions [

40,

41,

42]. Under conditions of sulfur deficiency in the soil, the yield-forming efficiency of nitrogen is reduced, and intensifying fertilization with this element deepens the sulfur deficit, which in turn inhibits nitrogen uptake by plants, limiting their growth and development [

43].

According to Motowicka-Terelak and Terelak [

44], the proper supply of sulfur to plants is important not only for production but also for ecological reasons. In conditions of deficiency of this nutrient in the soil, nitrogen fertilizer does not perform optimally, and the introduction of additional doses intensifies this deficit, causing a further reduction in yields and deterioration of their quality. Efficient use of nitrogen by plants is also important for environmental protection, because in conditions of sulfur deficiency, losses may occur as a result of nitrates (V) penetrating into groundwater, as well as the release of gaseous forms (NO

x) into the atmosphere [

45,

46].

Kocoń’s [

47] study demonstrated that foliar fertilization of rapeseed with urea and microelements intensified photosynthesis and nitrogen use efficiency, ultimately leading to higher yields. Budzyński and Jankowski [

48] found that a single foliar application of nitrogen at a dose of 30 kg·ha

−1, performed at the beginning of budding, was the most yield-enhancing method of feeding white mustard. It was also demonstrated that applying a portion of the nitrogen (25 + 5 kg·ha

−1) in the form of urea produced the same yields as a single application of the entire dose of this nutrient (30 kg N·ha

−1) in soil form. A higher nitrogen dose (60 kg·ha

−1) did not increase the seed yields.

Nitrogen applied to the soil generally caused a significant reduction in the crude fat content in mustard seeds compared to the N

40 dose (

Table 4). The differences were 2.2% (N

60) and 3.0% (N

80) in the first year, respectively, and 0.9% (N

80) in the second year. Regardless of the nitrogen doses applied to the soil, foliar application of this nutrient did not significantly affect its content in mustard seeds in the first year of the study. In the second year, a statistically confirmed increase in the amount of fat in seeds was observed in the treatment where 75% of the nitrogen dose was applied foliarly, compared to the treatment without foliar fertilization. The difference was 1.7%.

Similar results were obtained by Paszkiewicz-Jasińska [

9]. Using increasing nitrogen doses (30–120 kg N·ha

−1), she found a decrease in fat content in white mustard seeds. Jarecki and Bobrecka-Jamro [

49] did not demonstrate any effect of foliar nitrogen application on the fat content in spring rapeseed.

A significant increase in the total nitrogen content in seeds was observed under the influence of soil-applied doses of this nutrient compared to the N

40 dose, as well as a result of foliar nitrogen application, compared to the treatment where foliar nitrogen was not applied (

Table 4). It is worth emphasizing that a similar total nitrogen content, of which the appropriate content in seeds is an important parameter of crop quality, was obtained after application of the N

60 dose and in the treatments where half of the soil dose was replaced with foliar nitrogen. This is ecologically beneficial. It reduces the risk of nitrogen losses in the soil, caused by leaching into groundwater or volatilization into the atmosphere, which translates into less environmental pollution. The use of fertilizers containing sulfur affects the efficiency of nitrogen use. These elements determine the seed yield and lead to changes in their chemical composition. Sulfur affects protein quality, as it is a component of sulfur amino acids. It activates enzymes and participates in enzymatic reactions, thus influencing photosynthetic activity and increasing the protein, carbohydrate, and fat content in plants [

50,

51,

52]. Sulfur also determines the fatty acid profile [

53]. Studies by Poisson et al. [

54] have shown that sulfur and nitrogen synergistically affect plant metabolism when used at optimal doses. However, excessively high doses of one of the above elements antagonistically affect the utilization of the other. Therefore, it is important to adjust sulfur doses so that this element interacts with nitrogen and stimulates high yields and seed quality achieved in a sustainable manner, especially in the context of reducing the amount of fertilizers used [

55,

56,

57].

In both years of the study, the nitrogen utilization efficiency (NUtE) was significantly the highest in the seeds of plants fertilized with a dose of 40 kg N ha

−1—amounting to 20.98 and 21.22 kg kg

−1, respectively. For the other soil-applied nitrogen doses (60 and 80 kg N ha

−1), significantly higher values of this index were recorded after the application of 60 kg N ha

−1, with the obtained values being 20.95 and 20.87 kg kg

−1, respectively. Similar nitrogen utilization was observed in treatments where half of the soil-applied nitrogen dose (N

50%) was replaced with foliar fertilization. The obtained values were 20.61 and 20.42 kg kg

−1, respectively, indicating that the plants effectively utilized the absorbed nitrogen for yield formation, and that its partial foliar application is a good method to reduce losses of this nutrient. The nitrogen utilization efficiency in the N

75% treatments was generally the lowest and did not directly translate into an increase in seed yield. A decrease in nitrogen utilization efficiency (NUtE) with increasing nitrogen availability was also reported by Roussis [

58]. High nitrogen losses in agriculture are the reason for conducting many studies aimed at improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) by developing fertilization management strategies based on better synchronization between nitrogen supply and crop demand [

59,

60].

In the study by Blecharczyk et al. [

55], similar to our own research, rapeseed responded with an increase in total nitrogen content in seeds under the influence of increasing nitrogen doses. In the study by Garcia et al. [

61], foliar fertilization of winter rapeseed with nitrogen resulted in an increase in the content of this nutrient in seeds, and its content depended on the year of study.

Soil-applied nitrogen did not affect the amount of magnesium in mustard seeds (

Table 5). This relationship was observed in both years of the study. Foliar fertilization with nitrogen caused a significant reduction in the magnesium content in seeds compared to the treatment without foliar application. This reduction was significant in each year of study and occurred in all fertilization treatments.

In the first year of the study (2021), the N

60 and N

80 doses caused a significant reduction in the total phosphorus content in mustard seeds compared to the N

40 dose, which were 14.5 and 13.5%, respectively (

Table 5). In the second year (2022), these differences were 4.5 and 8%. Similar trends were found when replacing part of the soil dose with foliar fertilization in both years of the study.

In the study conducted by Rotkiewicz et al. [

62], the application of nitrogen at doses of 40, 80, and 120 kg·ha

−1 had no effect on the total phosphorus content in rapeseed.

The soil application of nitrogen did not significantly change the amount of potassium in mustard seeds (

Table 6). Significant inter-subject differences were found in 2021 between the treatments sprayed with N

50% and N

75% and the control.

Nitrogen is a fundamental yield-forming factor that modifies the quantity and quality of seed yields. A negative consequence of this nutrient’s increased yield is the “dilution effect,” which reduces the mineral content of the seeds, compromising their quality. White mustard seed yield was found to be negatively correlated with the magnesium and potassium content. However, a significant interaction was demonstrated between the nitrogen dose and application method for mustard seed yield and its chemical composition.

Brassicace seeds differ in their requirement and sensitivity to sulfur deficiency [

63]. According to De Kok et al. [

64], to ensure optimal growth and production, one part of sulfur should be used for 15–20 parts of nitrogen in plant tissue. In the first year of the study, the total sulfur content in seeds ranged from 5.708 g·kg

−1 to 15.282 g·kg

−1. In the next year, an increase in the sulfur content of approximately 26% was observed, ranging from 8.974 g·kg

−1 to 13.023 g·kg

−1. In the first year of the study, the highest sulfur content in seeds (10,919 g·kg

−1) was observed after soil application of ammonium nitrate at the lowest dose (N

40) (

Table 6).

The foliar application of nitrogen in the form of fertilizer that also contained sulfur significantly changed the content of this element in mustard seeds in both years of the study. In the first year, a 23% increase in sulfur content was observed in the treatment where 75% of the total dose was applied foliarly. In the following year, this difference was lower, approximately 15%, after the application of Multi-N

50. The sulfur content in white mustard seeds fertilized with the N

50 dose was similar to that in the treatment fertilized with the N

40 dose, which is beneficial for utilitarian and environmental reasons. The highest total sulfur content was observed in mustard seeds after foliar application of fertilizer that contained sulfur in addition to nitrogen, which likely enabled the incorporation of this element into both protein and secondary metabolites, which are sulfur-rich glucosinolates [

65].

3.3. Enzymatic Activity

The enzyme activity is presented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The results show that the applied doses and forms of mineral fertilizers significantly changed the soil enzymatic activity during the white mustard growing seasons.

Higher RDN and DH activity was found in the soil sampled in 2021. Such results can be explained, among other things, by the distribution of precipitation in the discussed growing seasons. In 2021, there was 13% higher precipitation. According to Manzoni et al. [

66] and Ren et al. [

67], soil water availability enables the mobility of dissolved substances and facilitates the supply of the substrate for organisms that decompose organic matter. Arylsulfatase activity was higher on average by about 80% in the following year of mustard cultivation. Arylsulfatase (EC 3.1.6.1) catalyzes the hydrolysis of organic sulfate esters to sulfate sulfur (VI) [

68]. The sources of this enzyme in soil are mainly fungi and bacteria but include plants and animals [

69]. Therefore, it is believed that both extracellular and intracellular arylsulfatase activity can be distinguished [

70]. Most likely, at such a low level of sulfate sulfur content in the soil, both microorganisms and cultivated mustard induced the secretion of this enzyme, stimulating a higher sulfate content in the soil.

The activity of the studied enzymes varied during the mustard growing seasons. AR activity was higher in soil collected in the first growing season by 28% and in the next by 20%. In 2022, a higher activity of rhodanese and dehydrogenases was observed in the first growing season by 14% and 22%, respectively. Dehydrogenase activity varied the least between the growing seasons—10% in the first year of the study (2021) and 1.2% in the following year. Higher enzyme activity at the beginning of the growing season may result from heavy spring rainfall and increased soil temperature and moisture, which accelerate the transformation of carbon and other organic matter components in the soil and improve the ability of soil microorganisms to metabolize enzymes [

71]. These environmental factors also indirectly regulate enzyme activity through their effects on microbial proliferation and substrate accessibility [

71]. Dehydrogenases (EC1.1.1.) are intracellular enzymes; therefore, their amount is directly related to the number of living microorganisms and is considered one of the most important parameters for the overall assessment of soil condition [

72,

73,

74].

Both soil and foliar nitrogen fertilization affected the activity of the studied enzymes. The effect of the highest soil dose of fertilizer was particularly observed, which stimulated AR activity on the first sampling date both in 2021 and especially in 2022, when it reached the highest value of 0.505 mM pNP·kg

−1·h

−1. Soil nitrogen fertilization also resulted in an increase in the enzymatic activity of dehydrogenases (

Figure 5). In both 2021 and 2022, a stimulating effect of ammonium nitrate at the N

80 dose was observed, especially on the first soil sampling date. Similar results were obtained by Rutkowski et al. [

75], who found that nitrogen fertilization had a significant effect on dehydrogenase activity in a cherry orchard in spring. Most likely, the N

80 dose was a sufficient amount of nitrogen to enable plant development, which translated into the proliferation of microorganisms in the rhizosphere. According to Sawicka et al. [

76], excessively high nitrogen doses (100 kg·ha

−1) contribute to the inhibition of dehydrogenase activity. The inhibitory effect of fertilizer was also observed in our study, in which foliar application of fertilizer in the first term inhibited DH activity.

Rhodanese (EC 2.8.1.1) is a transferase that takes part in transforming the sulfate sulfur from thiosulfate to cyanide, forming the less toxic thiocyanate and sulfite [

77]. Tukey’s analysis of variance showed that both soil and foliar nitrogen fertilization affected the RDN activity in samples collected in both years of the study. After mustard harvest, in treatments where N

80% soil nitrogen and N

75% foliar nitrogen were applied, inhibition of this enzyme activity generally occurred. Rhodanese is a sulfur transferase that catalyzes cyanide detoxification. It is synthesized by various plant and animal species, and its activity is modulated by a number of factors, including species differences, organ differences, gender, and age [

77].

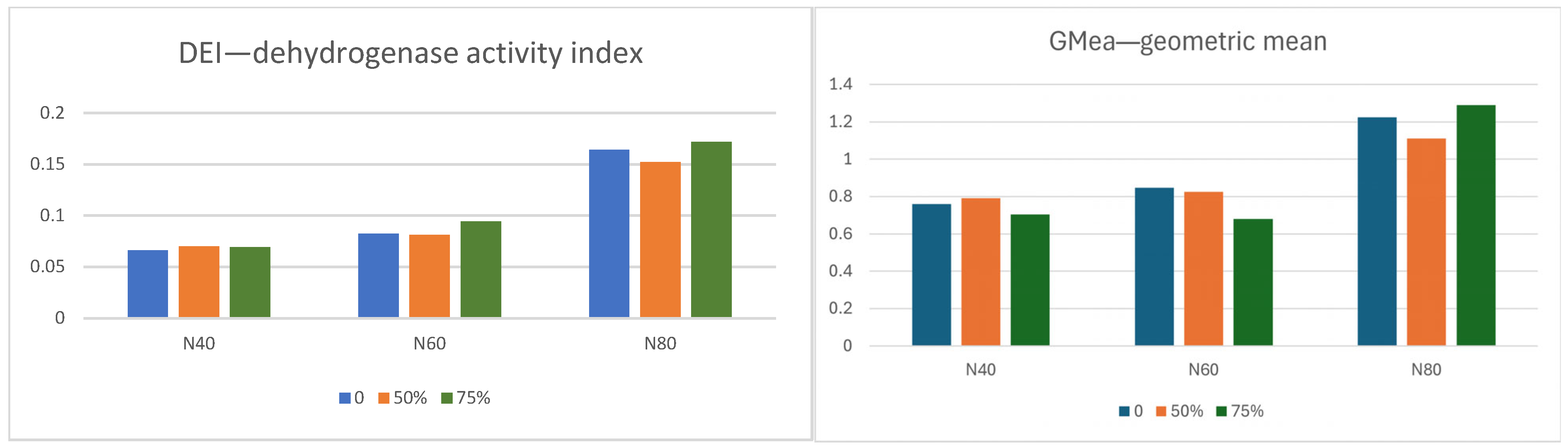

According to Muntean et al. [

22], the EI index can theoretically take values from 0 (when there is no activity in the tested samples) to 1 (when all actual individual values are equal to the maximum theoretical value of all individual activities), similarly to the DEI calculated by us. The values of the calculated DEI were in the low range of 0.067 to 0.172 (

Figure 5). Dehydrogenase activity in the soil is used as a biological indicator of the overall microbial respiratory activity of soils, because DH is used by microorganisms in the soil to break down organic matter [

78]. In our study, the highest DEI activity was obtained in foliar fertilization treatments (N

75%). These results suggest that mustard root exudates enabled the proliferation of microorganisms in the rhizosphere. The fertilizer with the highest nitrogen dose (N80) increased the DEI 1.9 and 2.3 times the value of these indicators of N60 and N40, respectively. Dehydrogenase activity is used to determine the microbiological-based respiration [

79]. Soil respiration (SR) is the main mechanism by which terrestrial ecosystems release CO

2 into the atmosphere through the oxidation of soil organic matter [

80]. The highest dose of nitrogen assessment contributed to an increase in the rate of aerobic metabolism and enhanced the basal respiration of microorganisms. The impact of the application of mineral fertilizers on soil respiration and enzyme activities was demonstrated in earlier studies [

81].The geometric mean was used to determine the medium-term rate of change. The GMea coefficient values calculated for AR and RDN activity ranged from 0.5119 to 0.9615. During the two-year study period, it was observed that the mineralization processes of organic matter containing sulfur were most intense in the treatments with the highest dose of foliar nitrogen (N

75%). This suggests a stimulating effect of foliar fertilizer application, which also included sulfur compounds. According to Kondratowicz-Maciejewska et al. [

82], higher GMea coefficient values indicate higher soil quality and can be used to determine qualitative changes in the soil, disregarding its physicochemical properties.

To assess the total enzyme activity in the tested soil, the total enzyme activity index (TEI) was calculated. Its value varied, depending on the soil and foliar fertilization applied. The highest TEI values were observed after the application of N

80 (average 4.0); other soil nitrogen doses translated into lower values of this index: N

40—2.5 and N

60—2.6, respectively (

Figure 6).

RDN activity showed a moderate correlation between the sulfate content in the soil (r = 0.49,

p = 0.05) and AR activity (r = 0.31,

p = 0.05) (

Figure 7). The study also obtained a positive correlation between the activities of individual AR and RDN enzymes (r = 0.33,

p = 0.05) as well as between RDN and DH (r = 0.33,

p = 0.05). The correlation between enzymes confirms the mutual interactions between enzymes and their participation in sulfur transformations in the soil, also found by Siwik-Ziomek and Szczepanek [

83]. According to Jat et al. [

84], interactions between enzymes have important implications for the nutrient availability to plants, because, upon decomposition, crop residues release nutrients that could help save precious nutrients applied externally, in addition to improving the overall soil quality and carbon enrichment.