Abstract

Long-term fertilization affects soil nutrient levels and aggregate stability, eventually altering crop yield. However, their responses to organic fertilizer application and straw returning are still unclear, particularly as the contributions of soil nutrient levels and aggregate stability on crop yields remain poorly quantified. Therefore, topsoil samples (0–20 cm) were collected from six fertilization treatments in a long-term (13-year) Shajiang black soil field experiment with no fertilization (CK), chemical fertilization (NPK), 50% NPK plus pig manure (50%NPKP), 50% NPK plus cattle manure (50%NPKC), 70% NPK plus pig manure with straw return (70%NPKPS), and 70% NPK plus cattle manure with straw return (70%NPKCS). We examined the characteristics of crop yield, soil nutrient levels, and soil aggregate stability parameters, including under different long-term fertilization treatments. The results show that long-term fertilization significantly influenced the distribution of soil nutrients and soil aggregates in Shajiang black soil. Compared to CK, organic fertilizers and straw returning significantly increased the soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP) contents but decreased soil pH, respectively, indicating the best strategies for improving soil fertility. Compared to the CK and NPK treatments, long-term organic fertilization and straw returning significantly increased the mean weight diameter (MWD) and geometric mean diameter (GMD) values and significantly decreased the fractal dimension (Dm) and mean weight-specific surface area (MWSSA) values, with the 70%NPKCS treatment showing the most pronounced effect of improving aggregate stability. A redundancy analysis revealed that SOM and TN exert significant effects on aggregate stability. Furthermore, a stepwise regression analysis showed that SOM and TN were positive factors affecting the yields of wheat and maize, while MWD and pH were negative factors affecting wheat yield, demonstrating that high crop yields are derived from soils with limited stability and high fertility. Thus, our findings indicate that the integrated application of cattle manure with straw returning was the most effective strategy to promote soil nutrient accumulation, improve aggregate stability, and enhance crop yield, albeit with the potential risk of soil acidification, which requires management in the Shajiang black soil (Vertisol) region of Northern China.

1. Introduction

Soil aggregates, as the fundamental units of soil structure, significantly influence soil fertility and quality by serving as key sites for the storage and cycling of water, air, heat, and nutrients [1,2]. Moreover, soil aggregate stability significantly influences biogeochemical cycles, soil fertility, and quality [2]. Conversely, the improvements in soil fertility resulting from the application of organic fertilizer and straw return can, in turn, further influence the distribution and stability of soil aggregates, as well as the dynamics of soil nutrients [3]. Thus, the application of organic fertilizers and the practice of straw return are vital field management strategies for enhancing soil nutrient content—particularly soil organic matter—and improving the stability of soil aggregates [3,4]. These practices play a crucial role in increasing crop productivity and supporting the sustainable use of arable land in the Shajiang black soil region of Northern Anhui. By promoting the formation and stabilization of macroaggregates, organic inputs facilitate better soil porosity and hydraulic properties, which in turn improve root development and nutrient availability. Therefore, adopting integrated organic management practices is essential for enhancing soil physical quality and ensuring long-term agricultural sustainability in this region. Investigating the effects of different manure applications and straw return on aggregate stability and crop yield and identifying optimal fertilization practices are crucial for improving soil structure and enhancing soil fertility.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the application of organic fertilizer combined with straw return can significantly improve soil aggregate stability and enhance soil fertility [5,6]. The study by Yang et al. [7] demonstrated that combining organic fertilizer application with straw return significantly promoted the formation of soil macroaggregates (>0.25 mm), thereby improving soil structure. Similarly, Ren et al. [8] reported that organic fertilizer application enhanced soil aggregate stability by increasing the concentrations of soil organic carbon (SOC), aromatic-C, and non-crystalline Fe. In contrast, Tantarawongsa et al. [9] found that long-term conventional tillage decreased aggregate stability, while practices such as crop residue incorporation effectively preserved it and increased SOC stock. Furthermore, no-till management supplemented with chemical fertilizer and cattle manure was shown to further enhance SOC sequestration. Gioacchini et al. [10] investigated the effects of long-term compost application on carbon and nitrogen in soil aggregates, and their results indicated that compost significantly altered the distribution of aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen, thereby improving aggregate stability. Thus, long-term application of organic fertilizer is considered to be a key practice for enhancing soil aggregate stability and fertility in agricultural soils. Furthermore, Chen et al. [11] revealed that the combined application of maize straw and organic fertilizer promoted the formation of macroaggregates and improved soil aggregate stability. Mehra et al. [12] demonstrated that the co-application of straw and green manure, along with NPK fertilization, significantly enhanced SOC stabilization and aggregate stability by strengthening Fe–organic associations in paddy soils. Xiong et al. [13] reported that chemical fertilizer and straw return treatments increased the proportion of large macroaggregates by elevating the content of free iron oxides in these aggregates. Zhang et al. [14] found that the combined application of straw and biochar with NPK fertilizers significantly increased the content of >2 mm aggregates and reduced the proportion of <0.25 mm aggregates compared to the control and NPK-only treatments, indicating that straw return enhances macroaggregate formation and aggregate stability. In another study, Zhang et al. [15] showed that long-term straw return improved soil structure by increasing geometric mean diameter (GMD) and mean weight diameter (MWD) after 10 years of straw return. However, the effects of straw return or its combination with biochar on soil aggregate stability vary depending on fertilization practices and soil types. Therefore, further research is needed to evaluate the impact of integrated organic fertilization and straw return on the distribution and stability of soil aggregates in the typical lime concretion black soils of Northern Anhui.

Shajiang black soil is widely distributed in the Huang–Huai–Hai Plain of Northern Anhui Province, accounting for approximately 62% of the national area of this soil type, making it one of China’s typical medium–low-yield soils [16,17]. Composed primarily of silt and clay particles, this soil exhibits poor aeration and water retention capacity, with a tendency toward acidity and structural degradation, leading to soil compaction and subsequent fertility decline [18,19]. These characteristics severely impair the growth and development of grain crops, ultimately affecting yield [20]. In the tillage layer of Shajiang black soil, the content of water-stable aggregates (0–25 mm) is relatively low (about 20%), while the subsurface layer is dense, predominantly displaying stable prismatic or angular block structures often coated with clay films, making it difficult to form water-stable aggregates and resulting in poor structural quality [21,22]. Therefore, studying the distribution and stability of aggregates in Shajiang black soil and elucidating the effects of long-term organic fertilizer application and straw incorporation on aggregate stability are of significant importance for improving soil fertility and quality in Shajiang black soil.

Understanding the responses of soil aggregates and nutrients to long-term fertilization and the contributions of soil aggregates and nutrients to crop yield is extremely important. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) investigate the distributions and differences in soil aggregate stability and soil nutrients and (2) understand the contributions of soil aggregates and nutrients to crop yield under the six different fertilization treatments. We hypothesized that fertilization affects crop yield by modifying the distributions of soil aggregates and soil nutrients significantly in the Shajiang black soil region of Northern Anhui.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site Description

The study area is located at the long-term experimental station of Agricultural Science Research Institute in Linquan County, Fuyang City, Anhui Province (E 115°06′, N 32°55′). The long-term experimental station was established in 2010, whereas our study was carried out during the 2022–2023 period with an average annual temperature of 15.3 °C, a maximum temperature of 41.4 °C, and an average annual precipitation of 892 mm. The experimental soil is classified as Shajiang black soil (Vertisols, USDA soil taxonomy) [23], with winter wheat (Hengguan 35) from mid-November to early June and summer maize (Zhengdan 958) from mid-June to early November as the rotation crops. Before the experiment, the initial values of soil pH, soil organic matter (SOM), alkaline-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, and total phosphorus (TP) were 5.72, 12.64 g kg−1, 80.16 mg kg−1, 16.92 mg kg−1, 116.7 mg kg−1, and 0.36 g kg−1, respectively.

2.2. In Situ Field Experiment Design

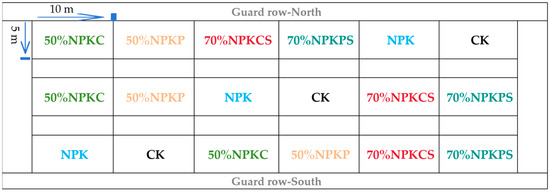

The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized block design with six treatments: (1) no fertilizer (CK); (2) local chemical fertilizer (NPK); (3) 50% of NPK plus pig manure (50%NPKP); (4) 50% of NPK plus cattle manure (50%NPKC); (5) 70% of NPK plus pig manure and straw return (70%NPKPS); (6) 70% of NPK plus cattle manure and straw return (70%NPKCS). Each treatment was replicated in three plots, and each plot (5 m × 10 m) was randomly allocated within blocks, each with an area of 50 m2 (Figure 1). The wheat cultivar was sown at 195 kg ha−1 with 15 cm row spacing. The maize cultivar was planted at 60,000 plants ha−1 with 60 cm row spacing. Other agronomic practices and pest and disease management were carried out according to local methods. All field management measures and irrigation conditions were consistent, except for the inconsistent fertilization treatments and the amounts of straw return.

Figure 1.

Distributions of experimental plots under the six fertilization treatments.

The fertilizers used in this study comprised urea (46% N), single superphosphate (16% P2O5), and potassium sulfate (50% K2O). For wheat cultivation, total nitrogen application was 300 kg ha−1 (120 kg ha−1 as basal dressing and 180 kg ha−1 as topdressing equally applied at jointing and booting stages), with basal P2O5 and K2O applied at 120 kg ha−1 and 100 kg ha−1, respectively, in a single application (Table 1). For maize, total nitrogen application was 250 kg ha−1 (100 kg ha−1 basal and 150 kg ha−1 topdressed at bell-mouth stage), with basal P2O5 and K2O both applied at 45 kg ha−1 (Table 1). The straw used for returning to the field during the wheat season and the maize season is all the straw harvested from the previous crop in this plot. Before wheat sowing, the required maize straw for each plot is crushed and evenly spread on the soil surface together with the required base fertilizer and organic fertilizer for the plot, followed by plowing and sowing. After maize sowing, the required base fertilizer, organic fertilizer, and crushed straw for the plot are applied to the soil in a furrow application method. Organic fertilizers were pig manure and cattle manure. The pig manure comes from Jiangyin Lianye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Jiangyin, China), with organic matter content of 45.5%, total N content of 2.30%, TP content of 2.90%, total K content of 1.20%, and cattle manure comes from Jiangsu Tianniang Agriculture Technology Co., Ltd. (Changshu, China), with organic matter content of 50.8%, total N content of 2.31%, TP content of 1.92%, and total K content of 2.42% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fertilizer dosage of each test plot for wheat/maize before sowing.

2.3. Soil Sampling

After maize harvest in mid-November 2023, surface soil samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected from each experimental plot using the five-point sampling method. Samples from five points within each plot were composited to form a single 2 kg bulk sample for laboratory analysis. The bulk sample was divided into two subsamples using the quartering method. Subsample 1 (for soil aggregate analysis): fresh soil was gently broken apart into fragments ≤ 8 mm, then air-dried at room temperature prior to analysis. Subsample 2 (for routine physicochemical analysis): air-dried at room temperature, then sieved through 2 mm and 0.15 mm meshes for subsequent analysis. Concurrently, wheat and maize grain yields were measured by weighing within each experimental plot. All samples were measured in triplicate.

2.4. Routine Soil Analysis

Routine soil analysis was performed as described in detail by Zhang et al. [24]. Soil pH was measured by the potentiometric method (soil–water ratio 2.5:1). SOM content was determined through a wet digestion method using potassium dichromate. Total N (TN) content was determined by the Kjeldahl method. TP content was measured by the perchloric acid–sulfuric acid–molybdenum–antimony–scandium colorimetric method. Total potassium (TK) content was quantified using the perchloric acid–sulfuric acid–flame photometric method.

2.5. Soil Aggregate Stability Analysis

The wet-sieving method was used to determine soil water-stable aggregate contents [25,26], which separated aggregates following the modified method described by Elliott et al. (1986) [27]. Tang et al. (2022) [28] described the detailed procedures of soil aggregate analysis. We finally collected four aggregate size fractions, including large macroaggregates (LMAs, 2~5 mm), macroaggregates (SMAs, 0.5~2 mm), small macroaggregates (MIAs, 0.25~0.5 mm), and microaggregates (SCAs, <0.25 mm), which were dried at 50 °C and weighed to calculate aggregate stability parameters [29,30].

Derived from the mass of aggregates in each size fraction, the mass percentage for each class was computed. Aggregate stability was employed to quantify by the content of >0.25 mm water-stable aggregates (WSAs), mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD), fractal dimension (Dm), and mean weight-specific surface area (MWSSA). The respective calculation formulas are given below [26,28,31,32,33]:

where is the mass of the >0.25 mm aggregates, and is the total mass of all aggregates.

where is the total number of fractions, is the proportion of the total aggregates in the fraction, and is the mean diameter of the sieve size.

where is the total number of fractions, is the cumulative mass of aggregates of less than size, is the total mass of all aggregates, is the aggregate size class, is the mean diameter of the largest aggregate class, and lg is decimal logarithm (log10).

where n is the number of aggregate size fractions, is the proportion of the total aggregates in the fraction, and is the mean diameter of the sieve size, and = 2.65 g cm−3.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The variance analysis of all data was conducted using SPSS 31.0 (IBM SPSS Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All figures were drawn in Origin 2025b (OriginLab Crop., Northampton, MA, USA). Significant differences in mean values were compared using the least significant difference tests and the Duncan test (p ≤ 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to explore the key factors regulating aggregate stability under different fertilization treatments using Origin 2025b. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was used to visualize the relationships between response variables (i.e., aggregate stability) and explanatory factors (soil nutrients) using Origin 2025.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Long-Term Fertilization on Soil Basic Properties

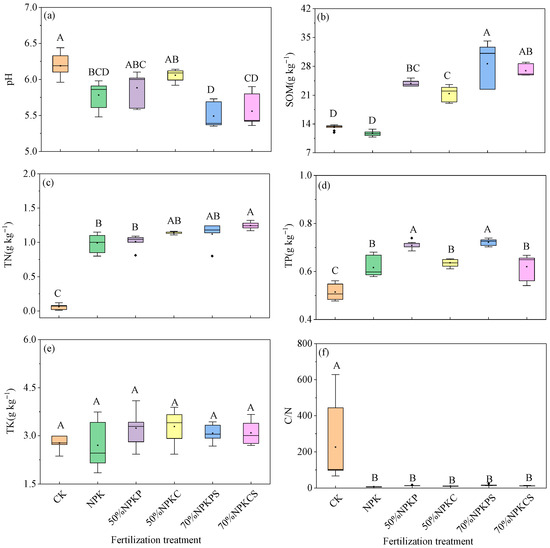

Long-term fertilization significantly affects soil chemical properties (Figure 2). Compared to the CK treatment, the NPK, 70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS treatments significantly reduced the soil pH by 6.57%, 11.27%, and 10.18% (Figure 2a), respectively. Relative to both the CK and NPK treatments, the 50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, 70%NPKPS, and 70%NPKCS treatments significantly increased the soil organic matter (SOM) content by 81.6~103.82%, 63.21~83.13%, 121.59~148.65%, and 104.41~129.36% (Figure 2b), respectively (p < 0.05). Among these, the 70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS treatments exhibited the greatest increase, indicating that the combined application of chemical fertilizers with manure or straw return effectively enhances soil fertility. Moreover, the 50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, 70%NPKPS, and 70%NPKCS treatments significantly increased the total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) contents by 0.92~1.18 g kg−1 and 0.10~0.21 g kg−1 as compared to the CK treatment, respectively (p < 0.05) (Figure 2c,d). Specifically, the 70%NPKCS treatment resulted in the highest increase in TN, while 50%NPKP and 70%NPKPS showed the greatest enhancement in TP. In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the total potassium (TK) content among the different fertilization treatments (p > 0.05) (Figure 2e). Additionally, compared to the CK treatment, the 50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, 70%NPKPS, and 70%NPKCS treatments significantly reduced the soil C/N ratio (p < 0.05) (Figure 2f). In summary, long-term fertilization increased key soil nutrients, such as organic matter, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus, and the application of manure and straw return yielded the most pronounced improvements in soil fertility, although these practices may also pose a potential risk of soil acidification.

Figure 2.

Soil basic chemical properties under the six fertilization treatments: (a) represents the values of soil pH; (b) represents the values of soil organic matter (SOM); (c) represents the values of total nitrogen (TN); (d) represents the values of total phosphorus (TP); (e) represents the values of total potassium (TK); (f) represents the ratio of soil organic carbon and total nitrogentotal potassium (C/N). CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return. Values followed by different capital letters in a column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

3.2. Distributions of Soil Aggregate Size and Soil Aggregate Stability Under Different Fertilization Treatments

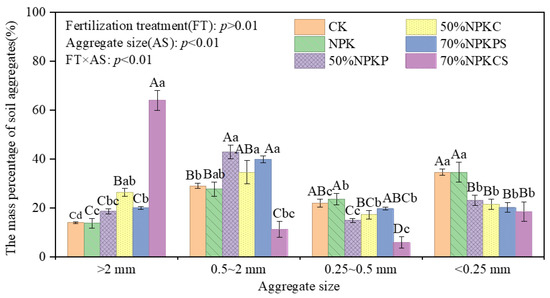

As shown in Figure 3, long-term fertilization significantly altered soil aggregate size distribution. No significant differences in the contents of the >2 mm, 0.5~2 mm, 0.25~0.5 mm, or <0.25 mm aggregates were detected between the CK and NPK treatments (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

The mass percentage of soil aggregates of different sizes as affected by fertilization treatments. CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return. Different uppercase letters in the bars represent significant differences among fertilization treatments for the same aggregate size (p < 0.05); different lowercase letters in the bars represent significant differences among aggregate sizes for the same fertilization treatment (p < 0.05).

Compared to CK and NPK, the >2 mm aggregate content was significantly elevated by 12.42~50.04% in the 50%NPKC treatment and 12.63~50.25% in the 70%NPKCS treatment. For the 0.5~2 mm aggregate, this content increased by 10.71~13.85% (50%NPKP) and 12.11~15.25% (70%NPKPS) relative to CK and NPK, but decreased by 17.80% relative to CK and 16.40% relative to NPK in the 70%NPKCS treatment. Consistently, the 0.25~0.5 mm aggregate content declined significantly by 7.13~16.14% (50%NPKP) and 8.72~17.73% (70%NPKCS) compared to CK and NPK, while the <0.25 mm fraction was reduced by 11.41~16.10% (50%NPKP; 50%NPKC) and 11.44~16.13% (70%NPKPS; 70%NPKCS) relative to these two control groups.

When comparing among the combined fertilization treatments, the >2 mm aggregate content was 7.72% higher in 50%NPKC and 45.34% higher in 70%NPKCS than in 50%NPKP, whereas 70%NPKCS showed 31.65% lower 0.5~2 mm and 9.01% lower 0.25~0.5 mm aggregate contents than 50%NPKP. Additionally, 70%NPKCS had a 37.62% higher > 2 mm aggregate content but 23.29% lower 0.5~2 mm and 11.29% lower 0.25~0.5 mm contents than 50%NPKC; in contrast, 70%NPKPS exhibited a 6.35% lower > 2 mm content than 50%NPKC. Notably, compared to 70%NPKPS, 70%NPKCS had a 43.97% higher > 2 mm aggregate content but 28.51% lower 0.5~2 mm and 13.79% lower 0.25~0.5 mm contents.

These findings indicate that (i) straw return combined with manure application—particularly the 70%NPKCMS treatment—most effectively shifted soil aggregate distribution toward the larger size fractions (>0.25 mm); (ii) pig manure preferentially stabilized aggregates in the 0.25–2 mm range, whereas cattle manure specifically promoted the formation of >2 mm macroaggregates. This size-dependent response points to distinct mechanisms of organic matter incorporation between the two manure types, with cattle manure exerting a stronger binding capacity for larger aggregates.

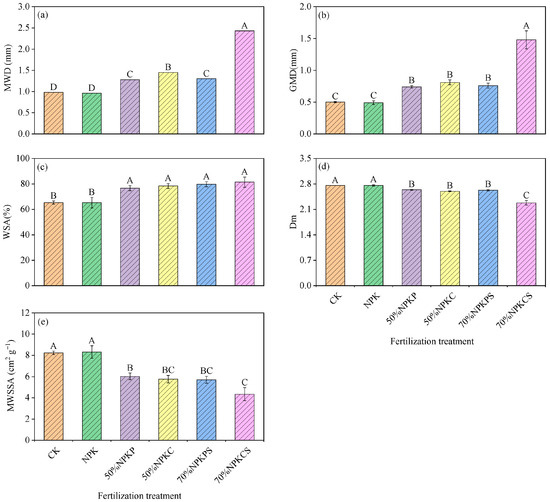

As shown in Figure 4, long-term fertilization significantly influenced soil aggregate stability parameters—including mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD), >0.25 mm water-stable aggregates (WSAs), fractal dimension (Dm), and mean weight-specific surface area (MWSSA). Compared to both the CK and NPK treatments, the MWD values in the 50%NPKPM, 50%NPKCM, 70%NPKPMS, and 70%NPKCMS treatments consistently increased by 30.18~147.40% and 32.75~152.27% (Figure 4a), and the GMD values in those treatments significantly enhanced by 48.85~197.27% and 51.54~202.64% (Figure 4b), and the WSA values in those treatments significantly increased by 17.47~24.64% and 17.52~24.69% (Figure 4c), respectively. Furthermore, the 70%NPKCMS treatment showed the greatest improvement in the MWD, GMD, and WSA values. In contrast, these four treatments reduced Dm by 4.28~17.46% and 4.40~17.57% (Figure 4d) as well as MWSSA by 26.92~47.23% and 27.57~47.70% (Figure 4e) as compared to the CK and NPK treatments, respectively. However, the 70%NPKCMS treatment experienced the most significant reduction in the values of Dm and MWSSA. In addition, compared to the 50%NPKPM and 70%NPKPMS treatments, the MWD value of the 50%NPKCM treatment increased significantly by 13.46% and 11.48%. Thus, these results confirm that combined straw return and organic fertilization—particularly the cattle manure-amended treatments—most effectively improved soil aggregate stability. This is evidenced by the maximum increases in MWD (by 67.49%) and GMD (by 82.37%) observed in the 70%NPKCMS treatment. The superior performance of cattle manure relative to pig manure highlights its stronger binding capacity for macroaggregates, which likely drives the enhanced stability in these treatments.

Figure 4.

Soil aggregate stability indexes under the six fertilization treatments: (a) represents the values of mean weight diameter (MWD); (b) represents the values of geometric mean diameter (GMD); (c) represents the values of >0.25 mm water-stable aggregate content (WSA); (d) represents the values of fractal dimension (Dm); (e) represents the values of mean weight-specific surface area (MWSSA). The error bars are three standard errors of the means (n = 3). CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return. Different uppercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

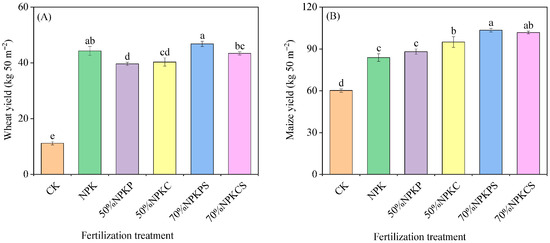

3.3. Distributions of Wheat and Maize Yields Under Different Fertilizer

As shown in Figure 5, long-term straw return and organic fertilization significantly affected the crop yields. Compared to the CK treatment, the NPK, 50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, 70%NPKPS, and 70%NPKCS treatments significantly increased the wheat yields by 297.01%, 255.22%, 261.19%, 319.40%, and 288.96%, respectively (p < 0.01) (Figure 5A), while the maize yields increased by 39.34%, 46.43%, 57.89%, 72.02%, and 69.25% (Figure 5B), respectively. Notably, the 70%NPKPS treatment exhibited the peak absolute increments, with increases of 46.83 kg 50 m−2 for wheat and 103.50 kg 50 m−2 for maize. Relative to the NPK treatment alone, 50%NPKP and 50%NPKC significantly reduced the wheat yields by 10.53% and 9.02%, respectively (p < 0.05), whereas 70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS maintained statistically equivalent wheat yields. For maize specifically, 50%NPKC, 70%NPKPS, and 70%NPKCS significantly boosted the yields by 13.32%, 23.46%, and 21.47% compared to NPK (p < 0.05), in contrast to the non-significant effect of 50%NPKP. These results indicate that integrated straw return and organic fertilization significantly enhanced maize productivity (p < 0.01) but did not consistently improve wheat yields relative to conventional NPK fertilization. Among all the treatments, 70%NPKPS achieved the optimal performance, likely driven by the synergistic nutrient supply effects of combined pig manure and straw.

Figure 5.

Crop yields under the six fertilization treatments: (A) represents the yields of wheat; (B) represents the yields of maize. The error bars are three standard errors of the means (n = 3). CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

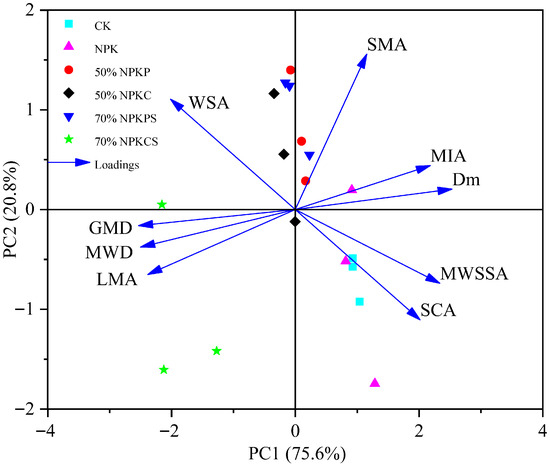

3.4. Relationship of Soil Aggregate Parameters and Soil Characteristics

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess the effects of different long-term fertilization regimes on soil aggregate characteristics (Figure 6). The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) collectively accounted for 96.38% of the total variance, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 75.58% and 20.80%, respectively, indicating that these two components effectively captured the majority of the variation in soil aggregate structure (Figure 6; Table 2). The PCA score plot revealed a clear separation among the treatments (Figure 6). The CK and NPK treatments were located in the lower-right quadrant, demonstrating similar aggregate properties. In contrast, the 70%NPKCS treatment was distinctly positioned in the lower-left quadrant, while the other organic-amended treatments (50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, and 70%NPKPS) were distributed around the x-axis (both sides) and above the y-axis.

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) on selected soil aggregate parameters and scores plotted in the plane of PC1 and PC2 in six different fertilization treatments. CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return. LMA, SMA, MIA, and SCA represent >2, 0.50~2, 0.25~0.50 mm, and <0.25 mm, respectively; MWD, mean weight diameter; GMD, geometric mean diameter; Dm, fractal dimension; WSA, >0.25 mm water-stable aggregate content; MWSSA, mean weight-specific surface area.

Table 2.

Loading factors of parameters on the first principal components (PC1 and PC2) of principal component analysis (PCA) applied to aggregate stability indices of soils subject to fertilizer treatments.

The loading analysis indicated that MWSSA and SCA were located in the lower-right quadrant, positively associated with CK and NPK. Conversely, GMD, MWD, and LMA were in the lower-left quadrant, strongly linked to the 70%NPKCS treatment. WSA was positioned in the upper-left quadrant, while SMA, MIA, and Dm were in the upper-right quadrant.

The comprehensive scores of the treatments were calculated based on the scores of PC1 and PC2 weighted by their respective variance contribution rates (Table 3). The ranking order was as follows: 70%NPKCS > 50%NPKC > 70%NPKPS > 50%NPKP > NPK > CK. This result demonstrates that the combined application of chemical fertilizers with manure and straw return, particularly the 70%NPKCS treatment, most effectively improved soil aggregate stability.

Table 3.

The scores of the first principal components (PC1 and PC2) of principal component analysis (PCA) applied to aggregate stability indices of soils subject to fertilizer treatments.

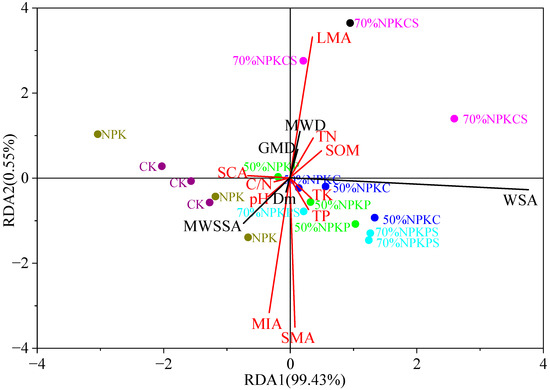

Based on the redundancy analysis (RDA), the distribution of the treatments and variables along the first two axes revealed distinct patterns driven by soil properties and aggregate characteristics (Figure 7). The first two RDA axes collectively explained 99.98% of the total variance, with RDA1 accounting for 99.43% and RDA2 for 0.55%, indicating that the variability in soil aggregate stability was overwhelmingly captured by RDA1. LMA, SOM, and TN significantly affected soil aggregate stability (p < 0.05). A significant positive correlation was observed among LMA, SOM, TN, MWD, and GMD across the six fertilization treatments (p < 0.05), and these parameters strongly responded to soil aggregate stability. Conversely, soil aggregate size, including MIA and SMA, showed a negative correlation with Dm and WSSA (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Two-dimensional sequence diagram of redundancy analysis (RDA) among aggregate stability and soil basic properties in different fertilization treatments. SOM, soil organic matter; TP, total phosphorus; TK, total potassium; TN, total nitrogen; C/N, the ratio of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen; LMA, SMA, MIA, and SCA represent >2, 0.50~2, 0.25~0.50 mm, and <0.25 mm, respectively; MWD, mean weight diameter; GMD represents the geometric mean diameter; Dm, fractal dimension; WSA, >0.25 mm water-stable aggregate content; MWSSA, mean weight-specific surface area. The numbers represent the correlation coefficients. CK, no fertilizer; NPK, chemical fertilizer; 50%NPKP, 50% of chemical fertilizer and pig manure; 50%NPKC, 50% of chemical fertilizer and cattle manure; 70%NPKPS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus pig manure and straw return; 70%NPKCS, 70% of chemical fertilizer plus cattle manure and straw return.

In the RDA biplot, the six fertilization treatments were clearly separated along RDA1. The 70%NPKCS treatment was located in the upper-right quadrant and was strongly associated with key aggregate stability parameters such as MWD and GMD, as well as LMA and soil nutrients including TN and SOM. In contrast, the 50%NPKP, 50%NPKC, and 70%NPKPS treatments clustered in the lower-right quadrant, showing closer relationships with TK and TP. The remaining treatments (CK and NPK) were distributed on the left side of the x-axis (RDA1 ≈ 0). Meanwhile, parameters such as MWSSA, Dm, pH, C/N, and MIA were grouped in the lower-left quadrant, reflecting their negative correlations with aggregate stability and association with unamended or mineral-only fertilization.

These results demonstrate that the 70%NPKCS treatment—combining reduced chemical fertilizer with cattle manure and straw—most effectively promoted the formation of water-stable aggregates, primarily by enhancing soil organic matter and total nitrogen content. In contrast, the conventional fertilization (NPK) and no-fertilizer (CK) treatments were linked to soil properties indicative of poorer structure, such as higher acidity and elevated microaggregate fractions.

3.5. Contribution of Soil Aggregate Parameters and Soil Characteristics on Wheat and Maize Yields

To further identify the aggregate size fractions influencing aggregate stability, a stepwise regression analysis was performed (Table 4). The MWD showed a highly significant positive correlation (p < 0.01) with the >2 mm, 0.50~2 mm, and 0.25~0.50 mm fractions. Among these, the >2 mm fraction had a greater influence on MWD than the 0.50~2 mm and 0.25~0.50 mm fractions. Moreover, the GMD was positively correlated (p < 0.01) with the >2 mm fraction and negatively correlated (p < 0.01) with the <0.25 mm fraction. Further, the WSA was significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.01) with the <0.25 mm fraction. On the contrary, the Dm exhibited a highly significant positive correlation (p < 0.01) with the <0.25 mm fraction and a significant negative correlation (p < 0.01) with the >2 mm fraction. In addition, the MWSSA was positively correlated (p < 0.01) with the 0.50~2 mm, 0.25~0.50 mm, and <0.25 mm fractions, with the <0.25 mm fraction being the strongest predictor. Therefore, soil aggregate stability is governed by the size distribution of the aggregates.

Table 4.

Stepwise regression equation among aggregate parameters, soil characteristics, and wheat and maize yields.

Additionally, as shown in Table 4, wheat yield was significantly positively correlated with TN but significantly negatively correlated with pH and MWD. Among these factors, TN had a greater influence on wheat yield than pH and MWD. In contrast, maize yield was significantly positively correlated with both TN and SOM, with TN exhibiting a stronger contribution than SOM. These results indicate that both aggregate stability (represented by MWD) and soil nutrients (such as TN and SOM) collectively influence wheat and maize yields.

4. Discussion

4.1. Response of Soil Nutrients to Long-Term Integrated Organic Amendment and Straw Incorporation

Our long-term fertilization experiment provides compelling evidence that the integration of organic amendments with chemical fertilizers fundamentally reshapes soil nutrient dynamics and biogeochemical cycling (Figure 1). The most pronounced enhancements in SOM and TN were observed under the combined manure and straw return treatments (70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS) (Figure 1). This phenomenon can be attributed to the inherently high carbon levels of pig manure and cattle manure [34,35]. Moreover, the dual role of organic inputs was a direct source of organic carbon and a slow-release nutrient reservoir. Consistent with the findings of several long-term studies [36,37], the incorporation of cereal straw, rich in recalcitrant lignocellulose, contributes primarily to passive and stable carbon pools, enhancing long-term carbon sequestration. In contrast, livestock manures, with a higher proportion of labile organic compounds and microbial biomass, rapidly fuel the soil food web, leading to a transient increase in microbial activity and necromass accumulation, which constitutes a significant pathway for the formation of mineral-associated organic matter [38]. Moreover, compared to the CK and NPK treatments, the 70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS treatments indirectly enhanced the soil carbon input by increasing the crop biomass (Figure 4), such as by wheat straw return, roots, and root exudates. The synergistic effect between these two types of organic materials creates a balanced input of labile and recalcitrant carbon, optimizing both immediate nutrient availability and long-term SOM stabilization [38,39]. This is powerfully corroborated by our RDA, which positioned SOM and TN as the dominant vectors, explaining the vast majority of the variance observed (Figure 6). Furthermore, the lower TN content under the CK treatment and the higher SOM and TN contents under all the treatments except CK may have caused an imbalance in the soil C:N ratio, intensifying TN limitation. Notably, we observed that the CK treatment had a lower ratio of soil organic C and TN (Figure 1). Moreover, our results show that the 50%NPKP and 70%NPKPS treatments had higher TP content as compared to the 50%NPKC and 70%NPKCS treatments (Figure 1). This can be explained by the fact that pig manure naturally contains a higher TP content (2.90%), while cattle manure has a lower TP content (1.92%). Therefore, long-term integrated organic amendment and straw incorporation can increase soil fertility by boosting the contents of nutrients, including SOM, TN, and TP.

Although the application of organic fertilizers and straw returning can enhance soil fertility, they also pose a risk of acidification [38]. Our study observed that the 70%NPKPS and 70%NPKCS treatments had higher SOM and TN contents but lower soil pH (Figure 1). This is mainly because microbial decomposition processes lead to the production of organic acids [40], leading to a decrease in soil pH. However, this robust nutrient enrichment was coupled with a significant decrease in soil pH, unveiling a critical trade-off in intensive organic amendment practices. The acidification phenomenon is multifactorial [41,42]. First, the nitrification of ammonium nitrogen derived from both the chemical fertilizers and the mineralizable nitrogen in manure generates H+ ions [41]. Second, the microbial decomposition of organic materials releases various low-molecular-weight organic acids and CO2, which, upon hydration, forms carbonic acid, further contributing to soil acidity [40]. Third, the plant uptake of base cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, and K+) in these high-yielding systems, if not sufficiently replenished, can accelerate the acidification process [43]. The low pH in organically amended soils, therefore, is not merely a sign of chemical fertilizer use but a complex outcome of enhanced microbial activity and nutrient cycling. This presents a significant management challenge as soil acidity can alter the availability of key nutrients like phosphorus and molybdenum and potentially increase the solubility of toxic aluminum and manganese ions. Future management strategies must, therefore, integrate practices such as the application of liming materials or the use of biochar with a high acid-neutralizing capacity to sustainably harness the benefits of integrated fertilization without compromising soil chemical health in the long term.

4.2. Effect of Organic Fertilizer Application Combined with Straw Return on Soil Aggregate Size and Stability Distributions

Our results demonstrate higher MWD and GWD values for 70%NPKCMS compared to the other treatments (Figure 3). Moreover, the 70%NPKCMS treatment had lower Dm and MWSSA values compared to the other treatments (Figure 3). These results indicate that the profound improvements in soil aggregate stability under the organic fertilizer application combined with straw return treatments, particularly 70%NPKCMS, underscore the pivotal role of organic inputs in structuring the soil physical architecture. These results are consistent with previous findings that the combination of manure and straw is most effective in promoting the formation and stabilization of macroaggregates [44,45]. This observation is central to the conceptual model of aggregate hierarchy, wherein the formation of large macroaggregates is primarily driven by transient binding agents and enmeshing by fungal hyphae [46]. The fresh organic matter from straw and manure provides the necessary energy for fungi and bacteria, whose hyphae and extracellular polymeric substances act as “sticky strings” that bind microaggregates and primary particles into stable macroaggregates [47,48]. Thus, the addition of exogenous organic matter is critical for improving soil structure and enhancing soil fertility.

Additionally, the multivariate analyses (PCA and RDA) consistently identified SOM and TN as the key factors correlating with and contributing to soil aggregate stability (Figure 6). The stability parameters (MWD and GMD) and LMA were strongly associated with these nutrients and the high-performing 70%NPKCMS treatment (Figure 6). This spatial association strongly indicates that the superior stability in this treatment is a direct consequence of enhanced macroaggregation. In contrast, Dm and MWSSA were associated with SCA in unamended soils, characterizing a poorly structured state (Figure 6). Conversely, the strong positive loading of the fractal dimension (Dm) and the mean weight-specific surface area (MWSSA) with the silt–clay fraction (SCA) in the opposite quadrant of the RDA plot provides a mechanistic explanation for poor soil structure. Thus, the reduction in these parameters in amended soils indicates an improvement in soil structure, demonstrating that integrated management fostered a positive trajectory in both soil nutrient status and physical properties. The integration of manure and straw synergistically improved the soil physical architecture by mitigating these negative indicators [49]. A higher Dm indicates a more complex and fragmented soil pore system, typical of soils dominated by fine particles and lacking in binding agents, which is characteristic of the CK and NPK treatments (Figure 6). The simultaneous reduction in Dm and MWSSA in the integrated treatments signifies a shift towards a coarser, more porous, and better-structured soil matrix. This improved architecture is critical for aeration, root exploration, and water infiltration, reducing the risks of surface crusting and erosion. The synergistic effect of manure and straw likely stems from their complementary decomposition rates: the more labile manure provides a rapid stimulus for microbial activity and binding agent production, while the more recalcitrant straw provides a longer-lasting physical matrix that supports the persistence of aggregates against disruptive forces like wetting and tillage [46,47,50]. Overall, the synergistic effect of manure and straw, mediated through enhanced soil organic matter and total nitrogen, directly improved aggregate stability by fostering a well-structured soil matrix conducive to root growth and hydrological function.

4.3. Effects of Soil Aggregates and Nutrients on Crop Yield Under Long-Term Organic Fertilization and Straw Return

Our study showed that wheat yield was significantly correlated with soil nutrients (TN and pH) and aggregate stability (MWD), while maize yield was significantly positively correlated with both TN and SOM (Table 4). The stepwise regression analysis and RDA indicated that fertilization predominantly boosted aggregate stability by increasing carbon and nitrogen inputs, which in turn resulted in increased wheat and maize yields (Table 4; Figure 6). Furthermore, the nexus between improved soil structure and enhanced crop productivity is unequivocally demonstrated in our long-term study. The significant positive correlations between crop yields (both wheat and maize) and TN firmly establish TN as the primary yield-limiting factor in this system. This finding aligns with the RDA results, which identified TN as a dominant driver of the entire soil ecosystem matrix (Figure 6). The integrated organic amendments serve as an engine for nitrogen cycling, providing a continuous supply of mineralizable N that better synchronizes with crop demand compared to the pulsed availability from chemical fertilizers alone [51]. This can lead to improved nitrogen use efficiency and reduced leaching losses. Furthermore, the 70%NPKCMS treatment promotes the formation of organic carbon, thereby facilitating the development of macroaggregates, which in turn leads to higher crop yields [52]. In addition, we founda significant negative correlation between wheat yield and MWD, which may suggest that, for wheat, an optimal, rather than a maximal, level of aggregation is beneficial. Excessively large and stable aggregates could potentially impede root penetration in some soil types or create sub-optimal conditions for seedling emergence. Furthermore, this statistical relationship might be confounded by the strong co-variation of MWD with other factors; the treatments that generated the highest MWD (e.g., 70%NPKCMS) also caused the most significant acidification, and it is possible that, for wheat, the negative effect of low pH at a critical growth stage partially offsets the positive benefits of improved soil structure. For maize, which showed no such negative correlation, a stronger taproot system might be less hindered by high aggregate stability.

Ultimately, the highest yields under treatments like 70%NPKCS are explained by a synergistic mechanism. The addition of manure and straw creates a positive feedback loop: it directly enhances the TN and SOM pools, which in turn promotes the formation of stable aggregates. This improved physical environment protects soil organic matter within aggregates, reduces erosion, enhances water retention and gas exchange, and fosters a more robust and diverse microbial community [53,54]. This “soil health complex” collectively buffers plants against abiotic stresses and facilitates more efficient capture and utilization of resources, thereby sustaining high crop productivity [54]. Thereby, our results confirm that moving beyond a purely nutrient-centric view to embrace the management of the physical and biological components of soil fertility is paramount for achieving sustainable high yields.

5. Conclusions

Our long-term study demonstrates that the application of organic fertilizer, particularly in combination with straw return, significantly improves soil aggregate stability, increases soil nutrients, and enhances crop yield in the winter wheat–summer maize double-cropping system. Organic fertilizers and straw returning (70%NPKCS) significantly increased the soil nutrients (SOM, TN, and TP) and aggregate stability (MWD and GMD) contents but decreased soil pH, indicating that the synergistic enhancement of soil fertility (chemical) and structure (physical) facilitates greater nutrient use efficiency, ultimately translating into sustained crop yield increases. The multivariate analyses (PCA and RDA) confirmed that these improvements were primarily driven by increases in SOM and TN, which act as key binding agents for soil particles. A significant consequence of these intensive organic amendment practices was soil acidification. Total nitrogen was identified as the primary nutrient limiting crop yields for both wheat and maize in this system, underscoring the importance of managing the nitrogen cycle for achieving high productivity. In conclusion, we recommend the widespread adoption of integrated fertilization strategies combining cattle manure with straw returning to enhance soil health and crop yield. However, we should adopt the best appropriate measure to mitigate acidification risks and ensure the long-term viability of this highly beneficial practice in the Shajiang black soil (Vertisol) region of Northern China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and X.T.; investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; visualization, formal analysis, Y.T., Y.Q., S.C., F.W., X.L. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, J.Z. and X.T.; funding acquisition, X.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Anhui Provincial Department of Education Key Project (2024AH050335) and Anhui Science and Technology University Talent Introduction Program (ZHYJ202203).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| MWD | Mean weight diameter |

| GMD | Geometric mean diameter |

| WSA | >0.25 mm water-stable aggregate content |

| Dm | Fractal dimension |

| MWSSA | Mean weight-specific surface area |

| LMA | Large macroaggregate (2~5 mm) |

| SMA | Small macroaggregate (0.5~2 mm) |

| MIA | Microaggregate (0.25~0.5 mm) |

| SCA | Small microaggregate (<0.25 mm) |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| TK | Total potassium |

| C/N | The ratio of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| RDA | Redundancy analysis |

| CK | No-fertilizer treatment |

| NPK | Conventional chemical fertilizer treatment |

| 50%NPKP | 50% of conventional chemical fertilizer with pig manure |

| 50%NPKC | 50% of conventional chemical fertilizer with cattle manure |

| 70%NPKPS | 70% of conventional chemical fertilizer with pig manure and straw return |

| 70%NPKCS | 70% of conventional chemical fertilizer with cattle manure and straw return |

References

- Bao, Z.R.; Dai, W.N.; Li, H.; An, Z.F.; Lan, Y.; Jing, H.; Meng, J.; Liu, Z.Q. Long-Term biochar application improved aggregate K availability by affecting soil organic carbon content and composition. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 5137–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Zhang, M.; Han, X.Z.; Lu, X.C.; Chen, X.; Feng, H.L.; Wu, Z.M.; Liu, C.Z.; Yan, J.; Zou, W.X. Evaluation of the soil aggregate stability under long term manure and chemical fertilizer applications: Insights from organic carbon and humic acid structure in aggregates. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 376, 109217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.C.; Zhang, S.R.; Sun, Z.Q.; Liu, Z.H.; Liu, S.L.; Ding, X.D. Straw incorporation and nitrogen fertilization enhance soil organic carbon sequestration by promoting aggregate stability and iron oxide transformation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ai, Z.P.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Leng, P.F.; Qiao, Y.F.; Li, Z.; Tian, C.; Cheng, H.F.; Chen, G.; Li, F.D. Influence of long-term inorganic fertilization and straw incorporation on soil organic carbon: Roles of enzyme activity, labile organic carbon fractions, soil aggregates, and microbial traits. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 392, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Bol, R.; Wang, T.; Zhu, P.; An, T.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Long-Term Fertilization mediatesmicrobial keystone taxa to regulate straw-derived 13C incorporation in soil aggregates. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Shutes, B.; Hou, S.N.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhu, H. Long-term organic fertilization increases phosphorus content but reduces its release in soil aggregates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 203, 105684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.B.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Y.P.; Cai, Z.J.; Li, D.C.; Wu, L.; Meersmans, J.; Colinet, G.; Zhang, W.J. Long-term manuring facilitates glomalin-related soil proteins accumulation by chemical composition shifts and macro-aggregation formation. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.J.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Han, Y.Y.; Zou, H.T.; Zhang, Y.L. Organic fertilizer enhances soil aggregate stability by altering greenhouse soil content of iron oxide and organic carbon. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantarawongsa, P.; Chidthaisong, A.; Aramrak, S.; Yagi, K.; Tripetchkul, S.; Sriphirom, P.; Onsamrarn, W.; Nobuntou, W.; Amornpon, W. Impacts of long-term tillage and fertilization on soil carbon stockand aggregate stability in tropical agriculture. Agric. Environ. Lett. 2025, 10, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioacchini, P.; Baldi, E.; Montecchio, D.; Mazzon, M.; Quartieri, M.; Toselli, M.; Marzadori, C. Effect of long-term compost fertilization on the distribution of organic carbon and nitrogen in soil aggregates. Catena 2024, 240, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Hao, Y.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, M.J.; Mehmood, I.; Fan, M.S.; Plante, A.F. Maize straw-based organic amendments and nitrogen fertilizer effects on soil and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen. Geoderma 2024, 443, 116820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, M.; Huang, L.; Geng, M.J.; Gan, Y.F.; Cheng, J.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Ali-Ahmad, I.; Haider, S.; Mustafa, A. Co-utilization of green manure with straw return enhances the stability of soil organic carbon by regulating iron-mediated stabilization of aggregate-associated organic carbon in paddy soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 252, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.H.; Gao, Z.Y.; Lu, J.W.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, X.K. Straw return combined with potassium fertilization improves potassium stocks in large-macroaggregates by increasing complex iron oxide under rice–oilseed rape rotation system. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wei, Y.X.; Liu, J.Z.; Yuan, J.C.; Liang, Y.; Ren, J.; Cai, H.G. Effects of maize straw and its biochar application on organic and humic carbon in water-stable aggregates of a Mollisol in Northeast China: A five-year field experiment. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 190, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.H.; Yang, L. Continuous straw returning enhances the carbon sequestration potential of soil aggregates by altering the quality and stability of organic carbon. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Sun, X.; Jiang, W. Long-term tillage alters soil properties and rhizosphere bacterial community in lime concretion black soil under Winter wheat-summer maize double-cropping system. Agronomy 2023, 13, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.J.; Zhang, S.W.; Chen, F.K.; Zhou, S.Y.; Hu, R.X. Effects of modified coal gangue addition on CO2 release and organic carbon sequestration in Shajiang black soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Ning, Q.; Li, W.J.; Zhang, J.B.; Ma, D.H.; Zhang, C.Z. Organic amendment mitigates the negative impacts of mineral fertilization on bacterial communities in Shajiang black soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 150, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.B.; Gao, L.; Guo, Z.C.; Xiong, P.; Jiang, F.H.; Peng, X.H. Pore shrinkage capacity of Shajiang black soils (Vertisols) on the North China Plain and its influencing factors. Pedosphere 2024, 34, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.H.; Duan, Y.; Li, M.H.; Tang, C.G.; Kan, W.J.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhong, W.L.; Wu, L.F. Manure substitution improves maize yield by promoting soil fertility and mediating the microbial community in lime concretion black soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Wang, Z.Z.; Gu, F.X.; Liu, H.; Kang, G.Z.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.H.; Guo, T.C. Tillage and irrigation increase wheat root systems at deep soil layer and grain yields in lime concretion black soil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.Y.; Guo, Z.C.; Qian, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.K.; Jiang, F.H.; Zhang, Z.B.; Peng, X.H. Interaction between POM and pore structure during straw decomposition in two soils with contrasting texture. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 245, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.Y.; Guo, Z.C.; Hua, K.K.; Yu, Z.Z.; Li, J.Q.; Chen, Y.M.; Guo, Z.B.; Wang, D.Z.; Liu, J.L.; Peng, X.H. Effects of legume-cover crop rotations on soil pore characteristics and particulate organic matter distributions in Vertisol based on X-ray computed tomography. Geoderma 2025, 461, 117464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Gong, Z.T. Soil Survey Laboratory Methods; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.S.; Chen, S.; Hui, R.G.; Li, Y.Y. Aggregate stability and size distribution of red soils under different land uses integrally regulated by soil organic matter, and iron and aluminum oxides. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 167, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Shaghaleh, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, T.; Li, B.; Lu, Y. Responses of soil labile organic carbon on aggregate stability across different collapsing-gully erosion positions from Acric Ferralsols of South China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.T. Aggregate structure and carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in native and cultivated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1986, 50, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Qiu, J.C.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, J.H.; Chen, J.H.; Li, B.; Lu, Y. Responses of soil aggregate stability to organic C and total N as controlled by land-use type in a region of south China affected by sheet erosion. Catena 2022, 218, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zheng, F.L.; Li, G.F.; Bian, F.; An, J. The effects of raindrop impact and runoff detachment on hillslope soil erosion and soil aggregate loss in the Mollisol region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 161, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.Y.; Shang-Guan, Z.P.; Deng, L. Soil aggregate stability and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen in natural restoration grassland and Chinese red pine plantation on the Loess Plateau. Catena 2017, 149, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Zhao, J.S.; Shi, Z.H.; Wang, L. Soil aggregates are key factors that regulate erosion-related carbon loss in citrus orchards of southern China: Bare land vs. grass-covered land. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 309, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagar, A.A.; Adamowski, J.; Memon, M.S.; Do, M.C.; Mashori, A.S.; Soomro, A.S.; Bhayo, W.A. Soil fragmentation and aggregate stability as affected by conventional tillage implements and relations with fractal dimensions. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Jiang, X.X.; Ji, X.N.; Zhou, L.T.; Li, S.Y.; Chen, C.; Li, P.Y.; Zhu, Y.C.; Dong, T.H.; Meng, Q.F. Distribution of water-stable aggregates under soil tillage practices in a black soil hillslope cropland in Northeast China. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhang, R.; Sun, N.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, F.; Xu, W. Patterns and driving factors of soil organic carbon sequestration efficiency under various manure regimes across Chinese croplands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, B.; Liang, Y.; Yang, L.; Song, J.; Li, T. Combined application of balanced chemical and organic fertilizers on improving crop yield by affecting soil macroaggregation and carbon sequestration. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; E, S.; Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Bai, L.; Wu, C.; Zeng, X. Long-term manure application enhances the stability of aggregates and aggregate-associated carbon by regulating soil physicochemical characteristics. Catena 2021, 203, 105342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Machado, S.; Bista, P. Decline in soil organic carbon and nitrogen limits yield in wheat-fallow systems. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wu, X.; Gao, H.; Jia, A.; Gao, Q. Long-term conservation tillage increases soil organic carbon stability by modulating microbial nutrient limitations and aggregate protection. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Ren, T.; Tian, Z.; Wang, G.; He, X.; Tian, C. Short-term effect of tillage and crop rotation on microbial community structure and enzyme activities of a clay loam soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 50, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.R.; Liu, W.X.; Liu, W.S.; Lal, R.; Dang, Y.P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stability and its response to no-till: A global synthesis and perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.K.A.; Gonzatto, R.; Aita, C.; Lupatini, M.; Jacques, R.J.S.; Kuramae, E.E.; Antoniolli, Z.I.; Roesch, L.F.W. Temporalvariability of soil microbial communities after application of dicyandiamide-treated swine slurry and mineral fertilizers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 97, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, C.C.; Coblentz, W.K.; Moore, P.A., Jr.; Akins, M.S. Effect of poultry litter application method and rainfall and delayed wrapping on warm-season grass baleage. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Lin, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Bolan, N.; Fan, J.; Ding, W. Long-term application of manure over plant residues mitigates acidification, builds soil organic carbon and shifts prokaryotic diversity in acidic Ultisols. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 133, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Han, X.; Li, X. Soil organic carbon and humus characteristics: Response and evolution to long-term direct/carbonized straw return to field. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Hu, X.; Shah, S.A.A.; Abrar, M.M.; Maitlo, A.A.; Kubar, K.A.; Saeed, Q.; Kamran, M.; Naveed, M.; Boren, W.; et al. Long-term fertilization alters chemical composition and stability of aggregate-associated organic carbon in a Chinese red soil: Evidence from aggregate fractionation, C mineralization, and 13C NMR analyses. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 2483–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.D.; Lu, S.G. Effects of five different biochars on aggregation, water retention and mechanical properties of paddy soil: A field experiment of three-season crops. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xin, X.; Zhu, A.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Mu, L.; Shao, L. Linking macroaggregation to soil microbial community and organic carbon accumulation under different tillage and residue managements. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 178, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sainju, U.M.; Li, C.; Fu, X.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J. Long-term chemical and organic fertilization differently affect soil aggregates and associated carbon and nitrogen in the Loess Plateau of China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Meng, Q.; Du, W. Soil aggregates stability and storage of soil organic carbon respond to cropping systems on Black Soils of Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Prakash, V.; Kundu, S.; Srivastva, A.K.; Gupta, H.S.; Mitra, S. Long term effects of fertilization on carbon and nitrogen sequestration and aggregate associated carbon and nitrogen in the Indian sub-Himalayas. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2010, 86, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Wang, Z.H.; Miao, Y.F.; Li, S.Q. Soil organic nitrogen and its contribution to crop production. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 2061–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Guo, R.; Qian, R.; Cai, T.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; et al. Soil aggregates and aggregateassociated carbon and nitrogen in farmland in relation to long-term fertilization on the Loess Plateau, China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Xin, X.L.; Zhu, A.N.; Zhang, J.B.; Yang, W.L. Effects of tillage and residue managements on organic C accumulation and soil aggregation in a sandy loam soil of the North China Plain. Catena 2017, 156, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikha, M.M.; Rice, C.W. Tillage and manure effects on soil and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).