Effect of Zeolite Amendment on Growth and Functional Performance of Turfgrass Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

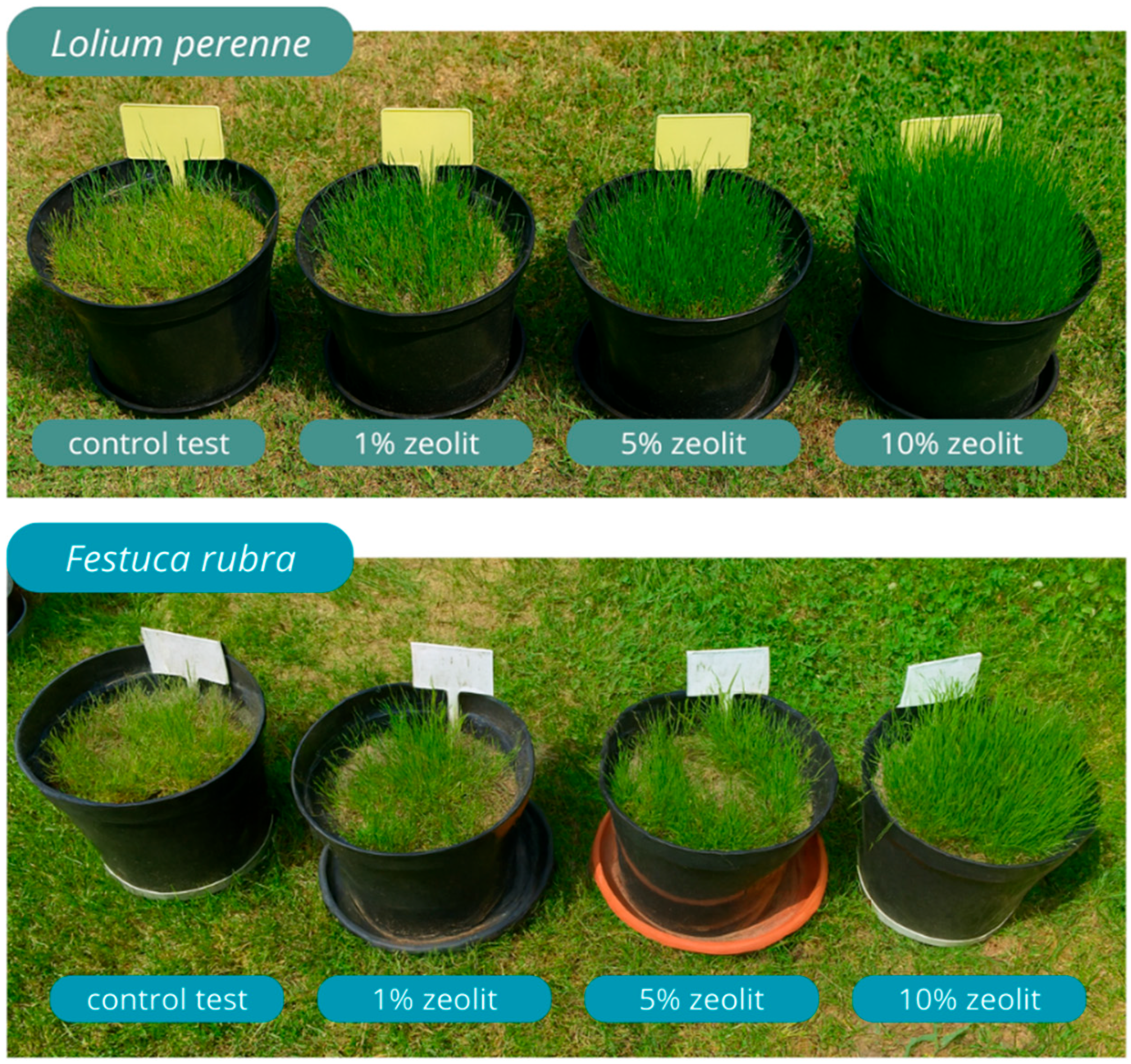

2.1. Pot Experiment—Experimental Design

2.2. Micro-Plot Experiment—Experimental Design

2.3. Weather Conditions During the Study Period

3. Results

3.1. Pot Experiment—Results and Analysis

3.1.1. Seedling Emergence

3.1.2. Seedling Height

3.1.3. Yield of Aboveground and Root Green Biomass of Grasses

3.2. Micro-Plot Experiment—Results and Analysis

3.2.1. Turf Cover

3.2.2. Share of Dicotyledonous Species

3.2.3. Overall Visual Quality of Turf

3.2.4. Green Biomass Yield

3.2.5. Winter Survival of Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinto, D.M.; Russo, D.D.; Sudoso, A.M. Optimal Placement of Nature-Based Solutions For Urban Challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A. Lawns in Cities: From a Globalised Urban Green Space Phenomenon to Sustainable Nature-Based Solutions. Land 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, R.C.; Mandal, P.; Nwachukwu, E.; Stanton, A. The role of turfgrasses in environmental protection and their benefits to humans: Thirty years later. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 2909–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Song, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, J.; Liu, J. Soil Moisture Determines Horizontal and Vertical Root Extension in the Perennial Grass Lolium perenne L. Growing in Karst Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippert, J.B.; Holdo, R.M. Challenging the maximum rooting depth paradigm in grasslands and savannas. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowska, M.; Kępkowicz, A.; Woźniak-Kostecka, I.; Lipińska, H.; Renaudie, L. Exploring the potential for development of urban horticulture in the 1960 s housing estates. A case study of Lublin, Poland. Urban For. Urban Green 2022, 75, 127689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Reddy, D.D. Zeolites and their potential uses in agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2011, 113, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, C.; Baskar, P. Zeolite and its potential uses in agriculture: A critical review. Agric. Rev. 2016, 37, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamhoseini, M.; Ghalavand, A.; Aydin Khodaei-Joghan, A.; Dolatabadian, A.; Zakikhani, H.; Farmanbar, E. Zeolite-amended cattle manure effects on sunflower yield, seed quality, water use efficiency and nutrient leaching. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 126, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudcová, B.; Osacký, M.; Vítková, M.; Mitzia, A.; Komárek, M. Investigation of Zinc Binding Properties onto Natural and Synthetic Zeolites: Implications for Soil Remediation. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2021, 317, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk-Mucha, K.M.; Lipińska, H.; Lipiński, W.; Stamirowska-Krzaczek, E.; Kornas, R.; Stryjecka, M.; Igras, J. The effect of zeolite on yield of Lactuca sativa var. capitata and chemical composition. J. Water Land Dev. 2025, 66, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifasi, N.; Ziantoni, B.; Fino, D.; Piumetti, M. Fundamental properties and sustainable applications of the natural zeolite clinoptilolite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriani, A.; Belviso, C.; Lovelli, S.; di Prima, S.; Coppola, A.; Hassan, S.B.M.; Rivelli, A.R.; Comegna, A. Impact of a Synthetic Zeolite Mixed with Soils of Different Pedological Characteristics on Soil Physical Quality Indices. Geoderma 2024, 451, 117084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, O.; Dinca, Z.; Senila, M.; Torok, A.I.; Todor, F.; Levei, E.A. Immobilization of Potentially Toxic Elements in Contaminated Soils Using Thermally Treated Natural Zeolite. Materials 2021, 14, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asghari, H.R.; Bochmann, G.; Tabari, Z.T. Effectiveness of Biochar and Zeolite Soil Amendments in Reducing Pollution of Municipal Wastewater from Nitrogen and Coliforms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E.; Konvalina, P.; Moudrý, J.; Bárta, J.; Kopecký, M.; Teodorescu, R.I.; Bucur, R.D. Comparative influence of biochar and zeolite on soil hydrological indices and growth characteristics of corn (Zea mays L.). Water 2022, 14, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA. International Rules for Seed Testing; International Seed Testing Association: Wallisellen, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron, G. Research methods used in the assessment and classification of meadow plant communities in Polish research works. Biul. IHAR 2024, 302, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, P. Systems of Research and Evaluation of lawn grasses Varieties in Poland. Biul. IHAR 1992, 183, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, E.; Salvi, L.; Paoli, F.; Fucile, M.; Masciandaro, G.; Manzi, D.; Masini, C.M.; Mattii, G.B. Application of Zeolites in Agriculture and Other Potential Uses: A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Tarafder, M.A.; Prit, M.S. Potential use of zeolites in agriculture: A review. SAARC J. Agric. 2024, 22, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhli, S.A.A.; Delkash, M.; Bakhshayesh, B.E.; Kazemian, H. Application of Zeolites for Sustainable Agriculture: A Review on Water and Nutrient Retention. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Biswas, B.; Garai, S.; Sarkar, S.; Banerjee, H.; Brahmachari, K.; Bandyopadhyay, P.K.; Maitra, S.; Brestič, M.; Skalický, M.; et al. Zeolites enhance soil health, crop productivity and environmental safety. Agronomy 2021, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girijaveni, V.; Sammi Reddy, K.; Srinivasarao, C.H.; Raju, B.M.K.; Balakrishnan, D.; Sumanta Kundu, S.; Pushpanjali; Rohit, J.; Singh, V.K. Role of mordenite zeolite in improving nutrient and water use efficiency in Alfisols. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1404077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadias, V.; Ioannou, Z.; Vavoulidou, E.; Paschalidis, C. Short-term effects of chemical fertilizer, compost, and zeolite on yield of maize, nutrient composition, and soil properties. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, M.H.; Majidi, M.M.; Pirnajmedin, F.; Maibody, S. Plant functional trait responses to cope with drought in seven cool-season grasses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mostafazadeh-Fard, S.; Samani, Z.; Shukla, M.K.; Bandini, P. Effect of Liquid Organic Fertilizer and Zeolite on Plant Available Water Content of Sand and Growth of Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 21, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.R.A. Effect of addition of sand and soil amendments to loam and brick grit media on the growth of two turf grass species (Lolium perenne and Festuca rubra). J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 9, 2485–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bandurska, H.Z.; Jóźwiak, W. A comparison of the effects of drought on proline accumulation and peroxidases activity in leaves of Festuca rubra L. and Lolium perenne L. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2010, 79, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selahvarzi, Y.; Maryam, K.; Somayeh, S.; Zabihi, M. Effect of natural zeolit and drought stress on some physiological and morphological traits of Festuca arundinacea grass. In Proceedings of the XI International Scientific Agriculture Symposium “AGROSYM 2020”, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 8–9 October 2020; Kovačević, D., Ed.; University of East Sarajevo, Faculty of Agriculture: East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020; pp. 357–362, ISBN 978-99976-78-75-1. [Google Scholar]

- Głąb, T.; Gondek, K.; Mierzwa–Hersztek, M. Biological effects of biochar and zeolite used for remediation of soil contaminated with toxic heavy metals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehakova, M.; Cuvanova, S.; Dzivak, M.; Rimar, J.; Gavalova, Z. Agricultural and agrochemical uses of natural zeolite of theclinoptilolite type. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Roussis, I.; Mavroeidis, A.; Stavropoulos, P.; Kanatas, P.; Pantaleon, K.; Folina, A.; Beslemes, D.; Tigka, E. Effects of Zeolite Application and Inorganic Nitrogen Fertilization on Growth, Productivity, and Nitrogen and Water Use Efficiency of Maize (Zea mays L.) Cultivated Under Mediterranean Conditions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelletti, S.; Meloni, F.; Freppaz, M.; Viglietti, D.; Lonati, M.; Enri, S.R.; Motta, R.; Nosenzo, A. Effect of zeolitite addition on soil properties and plant establishment during forest restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 132, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; Alghamdi, A.G. Effect of the particle size of clinoptilolite zeolite on water content and soil water storage in a loamy sand soil. Water 2021, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Liang, Y.; Sun, B.; Wu, Y.; Mao, X.; Lin, Y. Combination of artificial zeolite and microbial fertilizer to improve mining soils in an arid area of Inner Mongolia, China. J. Arid. Land 2023, 15, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzam, M.; Alami, H.; Khakzar, A.; Golkarian, A. How soil conditioners and planting methods influence the cost of seedling establishment. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e70193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuqoni, H. Effect of zeolite soil amendment on growth, productivity, and economic value of Zea mays. Radikula J. Ilmu Pertan. 2025, 4, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatanik-Kloc, A.; Szerement, J.; Adamczuk, A.; Józefaciuk, G. Effect of Low Zeolite Doses on Plants and Soil Physicochemical Properties. Materials 2021, 14, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Replication | Mixture (M1) | Mixture (M2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% |

| 2 | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% |

| 3 | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% |

| 4 | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% | Z 0 | Z 1% | Z 5% | Z 10% |

| Grass Species and Turf Variety | Proportion in Turf (%) |

|---|---|

| L. perenne cv. Bokser | 20 |

| L. perenne cv. Nira | 20 |

| L. perenne cv. Stadion | 15 |

| L. perenne cv. Elegana | 5 |

| F. rubra cv. Magitte | 10 |

| F. rubra cv. Rossinante | 10 |

| F. rubra cv. Nista | 10 |

| F. rubra cv. Nimba | 10 |

| Scale | Trait | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General Aspect | Turf Cover | Winter Survival | |

| 1 | Poor | poor (no leaves) | Poor |

| 3 | Weak | weak | Weak |

| 5 | Fair | fair | Average |

| 7 | Good | good | Good |

| 9 | very good | very good (perfectly uniform turf) | very good |

| Year | Month | Period | Annual | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | IV–X | ||

| Mean air temperature [°C] | ||||||||||||||

| 2020 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 14.3 | 9.6 |

| 2021 | −2 | −3 | 2 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 21 | 17 | 12 | 8 | 3 | −2 | 13.7 | 7.8 |

| 2022 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 11 | 10 | 3 | −1 | 14.1 | 8.9 |

| 2023 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 15.3 | 9.8 |

| 1991–2020 | −2 | −2 | 2 | 9 | 12 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 13 | 9 | 3 | −1 | 13.9 | 8 |

| Mean precipitation [mm] | ||||||||||||||

| 2020 | 25 | 45 | 35 | 9 | 85 | 220 | 35 | 75 | 65 | 55 | 15 | 25 | 544 | 689 |

| 2021 | 55 | 15 | 15 | 55 | 45 | 76 | 90 | 200 | 55 | 10 | 35 | 30 | 531 | 681 |

| 2022 | 20 | 35 | 20 | 40 | 55 | 45 | 130 | 70 | 105 | 30 | 20 | 65 | 475 | 635 |

| 2023 | 70 | 30 | 45 | 40 | 90 | 65 | 110 | 70 | 15 | 55 | 60 | 40 | 445 | 690 |

| 1991–2020 | 30 | 34 | 45 | 40 | 65 | 70 | 80 | 70 | 55 | 43 | 45 | 50 | 423 | 627 |

| Harvest | Zeolite Dose (%) | Yield Mixture 1 (g·pot−1) ± SD | Yield Mixture 2 (g·pot−1) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0 | b 38.08 ± 3.69 | b 24.29 ± 7.81 |

| 1 | a 64.15 ± 15.75 | a 44.1 ± 7.55 | |

| 5 | a 71.29 ± 13.99 | a 39.3 ± 15.69 | |

| 10 | a 57.96 ± 2.93 | a 41.4 ± 3.45 | |

| II | 0 | a 56.74 ± 7.34 | b 27.11 ± 11.25 |

| 1 | b 39.57 ± 6.7 | a 50.78 ± 6.25 | |

| 5 | a 64.45 ± 5.4 | a 56.29 ± 6.71 | |

| 10 | b 43.46 ± 12.63 | a 49.48 ± 1.23 | |

| III | 0 | a 55.1 ± 3.27 | b 33.48 ± 5.94 |

| 1 | b 38.96 ± 11.0 | a 50.7 ± 10.42 | |

| 5 | a 63.75 ± 2.91 | a 56.21 ± 10.87 | |

| 10 | b 43.29 ± 16.66 | a 49.4 ± 5.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lipińska, H.; Adamczyk-Mucha, K.; Michalik-Śnieżek, M.; Krukow, E.; Lipiński, W.; Stamirowska-Krzaczek, E.; Kornas, R.; Zarzecka, M.; Kamińska, W.; Karbowniczek, P. Effect of Zeolite Amendment on Growth and Functional Performance of Turfgrass Species. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112554

Lipińska H, Adamczyk-Mucha K, Michalik-Śnieżek M, Krukow E, Lipiński W, Stamirowska-Krzaczek E, Kornas R, Zarzecka M, Kamińska W, Karbowniczek P. Effect of Zeolite Amendment on Growth and Functional Performance of Turfgrass Species. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112554

Chicago/Turabian StyleLipińska, Halina, Kamila Adamczyk-Mucha, Malwina Michalik-Śnieżek, Ewelina Krukow, Wojciech Lipiński, Ewa Stamirowska-Krzaczek, Rafał Kornas, Maria Zarzecka, Weronika Kamińska, and Piotr Karbowniczek. 2025. "Effect of Zeolite Amendment on Growth and Functional Performance of Turfgrass Species" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112554

APA StyleLipińska, H., Adamczyk-Mucha, K., Michalik-Śnieżek, M., Krukow, E., Lipiński, W., Stamirowska-Krzaczek, E., Kornas, R., Zarzecka, M., Kamińska, W., & Karbowniczek, P. (2025). Effect of Zeolite Amendment on Growth and Functional Performance of Turfgrass Species. Agronomy, 15(11), 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112554