Abstract

This study collected 820 topsoil samples from cultivated lands across Ningxia, covering the Yellow River irrigation area, the central arid zone, and the southern mountainous region. The ordinary kriging were spatially interpolated to analyze As, Hg, Cd, Cr, and Pb heavy-metal pollution spatial patterns. Pollution was evaluated using the Nemerow and geoaccumulation (I(geo)) indices, and sources quantified via Pearson correlations, PCA (Principal Component Analysis), and PMF (Positive Matrix Factorization). The results indicated that Hg and Cd posed the highest ecological risks. The overall mean concentrations (mg.kg−1) of Hg, Cd, As, Pb, and Cr were 0.04, 0.27, 9.91,23.81, and 57.34, respectively. Compared with the background values, they were 1.90, 2.41, 0.83, 1.14, 2.74 times higher, respectively. Geospatially, regions with higher pollution probabilities for Cd, Cr, Pb, Hg, and As were concentrated in the northern and central parts of Ningxia, whereas the southern region exhibited lower pollution probabilities. pH significantly influenced the accumulation and spatial distribution of heavy metals in soil. Source apportionment identified three primary contributors: transportation and natural parent materials (As, Pb, Cr), industrial activities (Hg), and agricultural practices (Cd). Hg and Cd were identified as the key risk elements requiring prioritized management. These results enhance understanding of the pollution levers of heavy metals in Ningxia cultivated soils, and also provide foundation for developing more scientific and precise soil risk control policies, offering significant practical value for environmental risk management.

1. Introduction

High-quality and sustainable agricultural development in China hinges on well-cultivated soil, which directly impacts agricultural product quality, safety, food security, and human health [1]. The initial nationwide soil pollution survey in 2014 revealed that 16.1% of farmland soil in China exceeded standards, with varying degrees of pollution: slight (11.2%), mild (2.3%), moderate (1.5%), and severe (1.1%) [2]. The main pollutants contributing to this were Cd, Hg, As, Cu, Pb, Cr, Zn, and Ni, accounting for 82.4%. Factors such as population growth, urbanization, industrialization, climate change, smelting and pesticide use may accelerate the accumulation of heavy metals in soil [3], which persist for extended periods and are absorbed by plant roots, entering the food chain and posing risks to organisms within it [4]. The accumulation of heavy metals in soil is influenced by regional environmental changes and human activities, leading to complex and unpredictable spatial distributions [5]. Heavy metal pollution in cultivated soil significantly jeopardizes agricultural product safety, with long-lasting and costly consequences once soil is contaminated [6,7]. Therefore, It is critical to proactively address and mitigate sources of heavy-metal pollution in cultivated soils to safeguard soil and agricultural-product quality, while also identifying currently unpolluted regions that are vulnerable to future contamination [8].

In recent years, various techniques and models have been employed to assess the origins of heavy metal contamination in agricultural soils. These methods can be broadly categorized into qualitative identification of pollution sources and quantitative analysis of pollution sources [9]. Qualitative identification primarily involves determining the primary pollution sources through multivariate statistical analysis and principal component analysis. On the other hand, quantitative analysis utilizes receptor models, such as positive matrix factorization (PMF), chemical mass balance (CMB), and Unmix model [10,11], to quantify the sources of contamination. Among these analytical tools, PMF analysis is commonly utilized due to its constraint of non-negative values in the factor matrix, enabling the derivation of more practical factors [12]. Initially utilized for source apportionment of atmospheric particles, PMF analysis has been increasingly applied to analyze heavy metal sources in water, soil, and sediment [13,14]. The outcomes demonstrated the model is efficacy in identifying pollution sources and determining their respective contributions to heavy metal concentrations. Consequently, the PMF model has been employed for evaluating heavy metal levels in cultivated soils.

Ningxia, located in Northwest China, represents an arid/semi-arid, irrigated agro-ecosystem with legacy coal-chemical/metallurgical activities and Yellow River irrigation. Moreover, the environmental sensibility and fragility of the area also make it of great significance. The soil quality of farmland in Ningxia is under threat from various heavy metal pollutants due to rapid urbanization and the continuous progress of modern industry and agriculture. However, prior studies seldom integrate PMF with ordinary kriging to produce spatially explicit and source-attributed risk maps for cultivated soils. Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate heavy metal pollution of typical farmland in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. This study aims to analyze the spatial distribution trends of farmland soil heavy metals As, Hg, Cd, Cr, and Pb and evaluate their associated ecological risks. It also seeks to predict and provide early warnings for the environmental quality of heavy metals across different future periods and propose corresponding prevention measures. The findings of this study are valuable for elucidating the long-term fate of cultivated soil heavy metals and offer a theoretical foundation for soil pollution prevention and management for other similar areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is located in Northwestern China, bordered by Shaanxi Province to the east, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region to the west and north, and Gansu Province to the south, spanning between 35°14′ to 39°23′ N and 104°17′ to 107°39′ E. The region has a narrow north-south terrain, with elevations higher in the south that gradually decrease toward the north, characterized by significant elevation differences in the west and gentle undulations in the east. Benefiting from irrigation by the Yellow River, Ningxia is renowned as the “frontier south of the Yangtze River, the land of fish and rice.” The cultivated land area in Ningxia spans about 1.3 million hectares, with annual precipitation ranging from 167.2 mm to 618.3 mm, decreasing from south to north and occurring mainly in summer months.

2.2. Sample Collection and Analysis

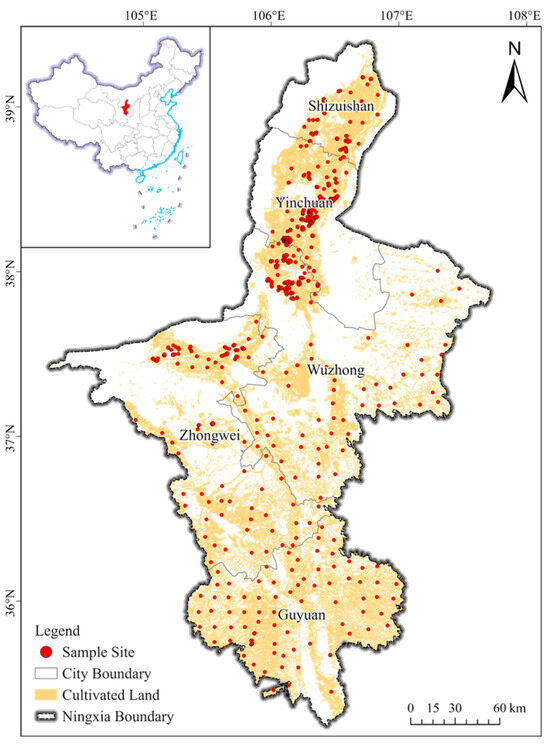

Soil samples were collected between June and August 2024 from key cultivated areas across the region, taking into account soil type, land use, cultivated area, and farming practices. Following a preliminary assessment of the farmland soil environment, areas with significant heavy-metal pollution were identified for targeted sampling. A combination of random and grid sampling was employed across Ningxia, and GPS was used to record the precise coordinates of each soil sample. In total, 820 soil samples were collected (Figure 1). At each site, five subsamples were taken at 0–20 cm from the four corners and the center of a 10 m × 10 m square using a wooden shovel and were composited. Approximately 1 kg of the composite was retained using the quartering method, properly labeled, bagged, and recorded in a dedicated data-collection application. The collected soil samples were air-dried, debris such as stones and plant roots was removed, then samples were sieved through a 2-mm mesh; a portion was further ground to pass a 0.15-mm sieve before final storage.

Figure 1.

Distribution map of cultivated soil sampling points.

All soil samples naturally air-dried and avoid direct sunlight, removing animal and plant residues, stones and plant roots. The passed soil sample was ground until it passed through a 0.149 mm sieves, and finally stored for future use. The soil samples were digested using the microwave digestion method of HCl, HNO3, HF, H2O2. The Pb, Cd, Cr, Hg and As were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, NexION300X, PE, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Each batch of sample analysis was set to 3 replicates, and the national standard soil samples (GSS-4 and GSS-6) were used for quality control and assurance. Soil salinity was measured using the conductivity method, and soil cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined using the resin method. The relative deviation of the measurement was controlled within ±10%. The pH value of the soil sample is determined by the potentiometric method (water-soil ratio is 2.5:1).

2.3. Data Processing

The soil samples were analyzed for heavy metal content using SPSS 21.0 for descriptive and qualitative analyses, EPA PMF 5.0 for quantitative analysis of heavy metals in cultivated soil, and ArcGIS 10.7 for assessing the spatial distribution characteristics of heavy metals in the cultivated soil.

2.4. Research Technique

2.4.1. Nemero Integrated Pollution Index Method

The Nemerow Integrated Pollution Index, introduced by the American researcher Nemerow, offers a comprehensive assessment of the pollution levels of various factors by considering both extreme and average values. This index effectively evaluates the overall pollution status of heavy metals at individual sampling points within the research area. Widely utilized, it stands as a prominent method for the holistic appraisal of pollution within a study area. The calculation formula is as follows:

In this study, Pi represents the pollution index of pollutant i in the soil, Ci denotes the measured content of pollutant i, and Si stands for the evaluation reference value of pollutant i. PN signifies the Nemerow comprehensive pollution index, Pimax is the maximum value of the single pollution index of heavy metal pollutant i at the sampling point, and Piave represents the average value of the single pollution index of heavy metal pollutants at the sampling point.

The evaluation standard utilized for risk screening was the Soil Environmental Quality Agricultural Land Soil Pollution Risk Control Standard (GB15618-2018). Appendix A Table A1 and Table A2 display the classification criteria for the single-factor pollution index and Nemerow index evaluation method.

2.4.2. Potential Ecological Risk Index Method

The Potential Ecological Risk Index method was introduced by the Swedish researcher Hakanson. This approach assesses the potential ecological risk posed by heavy metals in soil while accounting for their ecological toxicity [15]. The calculation formula for this method is as follows.

where, RI represents the integrated potential ecological hazard index of heavy metals, Ci denotes the concentration of heavy metal i, stands for the background concentration of heavy metal i (mg/kg) specific to Ningxia soil, signifies the pollution index of heavy metal i in soil, represents the biological toxicity response factor of heavy metal i, and indicates the potential ecological hazard index of heavy metal i in soil.

2.4.3. Geoaccumulation Index Method

The geoaccumulation index method is a crucial parameter for discerning the influence of human activities, as outlined by previous studies [16,17]. The calculation formula is presented below:

The geoaccumulation index (I(geo)) represents the concentration of heavy metal(Ci) in comparison to its background value (Bi), which is determined using the background value of heavy metal i in Ningxia soil and a correction factor of 1.5. The pollution levels are classified into seven grades based on the geoaccumulation index I(geo) ≤ 0 indicates no pollution;0 < I(geo) ≤ 1 signifies light pollution; 1 < I(geo) ≤ 2 indicates moderate-leaning pollution; 2 < I(geo) ≤ 3 indicates moderate pollution; 3 < I(geo) ≤ 4 signifies heavy-leaning pollution; 4 < I(geo) ≤ 5 indicates heavy pollution; and values exceeding 5 represents severe pollution.

2.4.4. Indicator Kriging

Journel proposed Indicator Kriging, a widely utilized method in soil pollution studies due to its ability to address extreme values and high deviation characteristics [18]. This study applied ordinary kriging to interpolate the spatial distribution of soil heavy metals. The reliability of the interpolation was evaluated through semivariogram model fitting and leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). First, empirical semivariograms for each heavy metal were computed from the sampling data and fitted with a spherical model. The predictive performance of the interpolation model was assessed using LOOCV. he final spatial distribution maps were produced in ArcGIS 10.2 with standardized legends, scale bars, and north arrows.

2.4.5. Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis-multiple linear regression (PCA-MLR) was employed to discern pollution sources in the research area. Following the determination of pollution factor quantities, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted on the concentration of individual tracer elements. This process yielded regression equations linking the concentration of heavy metals to each tracer element’s concentration. The regression coefficients were utilized to compute the relative contribution of each pollution source.

2.4.6. PMF Model

Positive matrix factorization (PMF) is a data analysis technique rooted in factor analysis principles. The PMF model decomposes the initial matrix X(i×j) into two factor matrices, F(k×j) and G(i×k), along with a residual matrix E(i×j), according to the following equation:

Let Xij represents the concentration of the jth chemical component in the ith sample, Gik denotes the contribution of the ith sample in source k (contribution rate matrix of the source), Fkj indicates the concentration of the jth chemical component in source k (source component spectrum matrix), and Eij stands for the residual matrix.

PMF defines the objective function Q as follows:

where Uij represents the uncertainty of the jth chemical component in the ith sample.

The PMF software necessitates the submission of concentration and uncertainty files. The uncertainty data files were computed in the following manner:

The uncertainty value is determined when the concentration of each element exceeds its respective method detection limit (MDL).

The relative standard deviation (RSD) is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of a dataset, where the standard deviation represents the variability within the data. The elemental concentration refers to the amount of a specific element present in a sample, while the method detection limit (MDL) signifies the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected by a given method.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) serves as the primary diagnostic tool in the model, distinguishing genuine variability in measured values from data interference. A lower SNR indicates greater instability in the chemical composition within the model, reducing the likelihood of sample detection. The determination of the number of Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) factors is based on the analysis of multiple experiments, errors, and relative changes in the Q values [19,20].

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Heavy Metal Content

Table 1 presents the key statistical parameters of five heavy metals within the study area. The levels of risk were determined based on the screening and risk control values outlined in the Soil Environmental Quality Control Standard for Soil Pollution of Agricultural Land (referred to as GB15618-2018). Soil contamination in agricultural land is classified as low risk when heavy metal concentrations are at or below the risk screening value, typically considered negligible. Conversely, if heavy metal levels exceed the risk screening value but are equal to or below the risk control value, there is a medium risk of soil pollution, potentially impacting the quality and safety standards of edible agricultural products. In such cases, mitigation measures like agronomic adjustments and crop diversification are recommended [21,22]. When heavy metal concentrations surpass the risk control value, indicating a high risk of soil pollution leading to non-compliance of edible agricultural products with safety standards, conventional mitigation strategies may be insufficient. Under these circumstances, stringent measures such as banning the cultivation of edible crops and converting farmland to forested areas are advised [23].

The study indicated low levels of heavy metal pollution in the agricultural soil, with 816 areas classified as low risk for Cd, while Cr, Pb, Hg, and As were all deemed low risk (Table 1). None of the average heavy metal contents exceeded the risk screening values outlined in GB15618-2018. The coefficient of variation (CV) was utilized to assess the dispersion of heavy metal content, with a CV exceeding 0.36 indicating high variation. The variation degree of heavy metals in Table 1 ranked as Hg > Cd > Cr > As > Pb, with Hg exhibiting the highest variation (CV > 0.36), suggesting significant susceptibility to external influences and human activities. Overall, the ecological risk to cultivated soil in the study area was low, with Cd and Hg posing pollution risks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of heavy metal content in surface soil of the study area.

Table 1.

Characteristics of heavy metal content in surface soil of the study area.

| Item | Number | Number of Different Risk b Points | Background c Values (mg/kg) | MDL (mg/kg) | Max (mg/kg) | Min (mg/kg) | Mean (mg/kg) | CV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||||||||

| Cd | 820 | 816 | 2 | 2 | 0.112 | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.1 | 0.27 | 0.3 |

| Cr | 820 | 820 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 1.0 | 97.2 | 14.3 | 57.34 | 0.28 |

| Pb | 820 | 820 | 0 | 0 | 20.9 | 2.1 | 52.4 | 10.4 | 23.81 | 0.19 |

| Hg | 820 | 820 | 0 | 0 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.003 | 0.04 | 0.47 |

| As | 820 | 820 | 0 | 0 | 11.9 | 0.01 | 20.3 | 1.77 | 9.91 | 0.24 |

| PH | 820 | — a | — | — | — | — | 9.09 | 6.45 | 8.18 | 0.04 |

| OM (g/kg) | 820 | — | — | — | — | — | 61.5 | 2.31 | 14.35 | 0.43 |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 820 | — | — | — | — | — | 18.3 | 3.1 | 10.95 | 0.2 |

Note: a “—” indicates that relevant data are not monitored; b Soil environmental quality risk control standard for soil contamination of agricultural land (GB15618-2018); c National Environmental Protection Agency of China (NEPA) & China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC). (1990) [20].

3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Assessment and Risk Assessment of Cultivated Soil

3.2.1. Evaluation of Soil Comprehensive Pollution Index

The pollution levels of heavy metals at various sampling points were assessed based on Pi, PN, and RI criteria. Ecological risk assessment of heavy metal pollution in cultivated soil in Ningxia was conducted using single-factor pollution index and Nemerow comprehensive pollution index [24]. Analysis presented in Table 2 revealed that the levels of Cr, Pb, and Hg were within safe limits, while Cd and As were at warning levels in 3.17% and 0.37% of the sample points, respectively. Additionally, Cd was found to be at a light pollution level in 0.27% of the sample points. Applying the Nemerow comprehensive pollution index to evaluate heavy metal contamination in soil, it was determined that 0.49% of the soil samples in the study area fell within the warning range. Furthermore, the Nemerow comprehensive pollution index for other heavy metal samples in the cultivated soil was below 0.7, indicating a safe pollution level.

Based on the potential ecological risk index () classification for heavy metal content in soil, the distribution of ecological risk levels was as follows: 0.12% of Hg samples exhibited extremely strong ecological risk, 1.10% showed very strong ecological risk, 38.05% indicated relatively strong ecological risk. Specifically, Cd elements were present in 0.49% of samples with strong ecological risk, 30.12% with moderate ecological risk, 66.83% with medium ecological risk; other heavy metal elements posed only slight ecological risks. In terms of the comprehensive ecological risk index (RI) for soil heavy metals, among the 820 sampling points within the study area, 0.12% were classified as having strong ecological risk, 60% as medium ecological risk, no sampling points with strong or extremely strong ecological risk.

Table 2.

Presents the statistics concerning heavy metal pollution index and potential ecological risk index within the research area.

Table 2.

Presents the statistics concerning heavy metal pollution index and potential ecological risk index within the research area.

| Item | Pollution Index | Proportion of Sampling Points at Different Pollution Levels (%) | Ecological Hazard Index a | Proportion of Sampling Sites with Different Ecological Risk Levels (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safe | Alert | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Strong | Very Strong | Extremely Strong | |||

| Cd | Pi | 96.56 | 3.17 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 2.56 | 66.83 | 30.12 | 0.49 | 0 | |

| Cr | Pi | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pb | Pi | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hg | Pi | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.39 | 41.34 | 38.05 | 1.10 | 0.12 | |

| As | Pi | 99.63 | 0.37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PN | 99.51 | 0.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | RI | 39.88 | 60 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | |

Note: a Hakanson, L. (1980) [19]. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control.

3.2.2. Evaluation of Geoaccumulation Index

The accumulation index of heavy metal elements in cultivated soil within the study area was determined using the Ningxia soil background values [20]. The results indicate that the heavy metal pollution levels in cultivated soil in Ningxia are predominantly low (see Table 3), with the exception of Cd and Hg. For Cd, 74.39% as lightly polluted, and 17.70% as moderately polluted. Regarding Hg, 61.34% were lightly polluted, and 8.78% were moderately polluted. Furthermore, Cr, Pb, and As exhibited non-pollution levels in 99.76%, 96.70%, and 99.63% of the samples, respectively, while light pollution levels were observed in 0.24%, 3.30%, and 0.37% of the samples, respectively.

Table 3.

Presents the geoaccumulation index (I(geo)) a for heavy metal accumulation in cultivated soil in Ningxia (mg/kg).

3.3. Analysis of Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Heavy Metals and pH

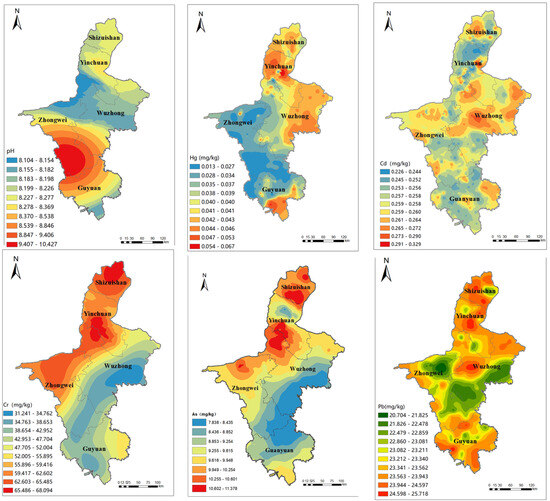

Geostatistical analysis of five heavy metals in Ningxia cultivated soil was conducted using ArcGIS 10.2 software, employing the Kriging interpolation method to map their spatial distribution [25] (Figure 2). The spatial patterns of As and Cr exhibit similarities, with elevated concentrations observed in the northern, northwestern, and central regions of Ningxia, while lower levels are found in the eastern and southern areas. High concentrations of Hg are concentrated in the northern and eastern parts of Ningxia, with additional elevated areas in the southern region, whereas lower levels are present in the central and western areas. Cd concentrations are pre-dominantly elevated in the central and eastern regions, with additional high-value areas in the north, west, and south. Pb concentrations peak in the northern and central regions of Ningxia.

Figure 2.

Spatial Interpolation distribution of heavy metals in agricultural soils.

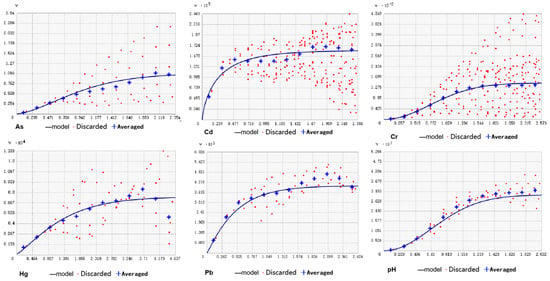

Overall, Figure 3 shows the experimental semivariogram and the fitted spherical model for soil heavy metals. The theoretical model demonstrates a good fit to the experimental data, effectively. All heavy metals exhibit elevated concentrations in the central and northern regions, with widespread high values observed for Hg and Cd. The heavy metal content is lower in the high-pH regions of cultivated soils.

Figure 3.

Semivariogram for heavy metals.

3.4. Analysis of Heavy Metal Sources

3.4.1. Correlation Analysis of Heavy Metals in Soil

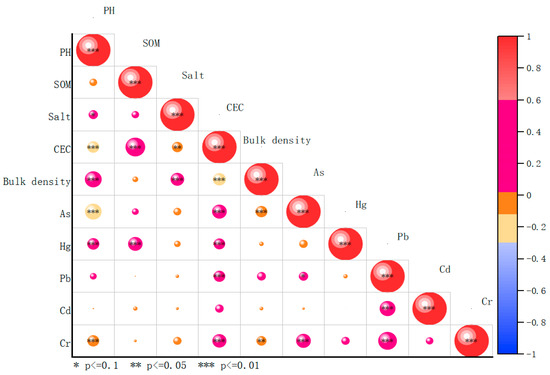

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant negative correlations between soil pH and soil organic matter, cation exchange capacity, As, Hg, Cd, and Cr. Additionally, soil pH exhibited negative correlations with As and Cr. Soil organic matter showed positive correlations with cation exchange capacity, As, Hg, Pb, and Cr. Conversely, soil salt content displayed negative correlations with cation exchange capacity, As, Hg, Pb, and Cr. Furthermore, As exhibited significant positive correlations with Pb and Cr, suggesting strong homology among these elements. Notably, Hg demonstrated an extremely significant positive correlation with Cr, indicating potential similarities in their migration patterns or sources (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pearson correlation analysis of heavy metal in agricultural land.

3.4.2. Principal Component Analysis of Heavy Metals in Soil

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to investigate the sources of heavy metals in cultivated soil in Ningxia. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value for the distribution of five heavy metals was 0.636, surpassing the significance threshold of 0.01, affirming the suitability of PCA for elucidating the correlation among heavy metal sources in Ningxia soil. Prior to PCA, data underwent averaging to account for variations in the magnitude of heavy metals. Through assessment of eigenvalues, cumulative explained variances, and factor loadings, three principal components were derived (see Table 4), collectively elucidating 71.52% of the variance. Specifically, the first principal component (PC1) explained 30.57% of the variance, followed by the second (PC2) at 21.67% and the third (PC3) at 19.28%. PC1 exhibited higher positive loadings for As and Cr, suggesting a common source for these heavy metals in agricultural soils. Cd displayed elevated positive loadings in PC2, while Hg exhibited the same in PC3.

Table 4.

Principal Component Matrix of Heavy Metals in Cultivated Soil.

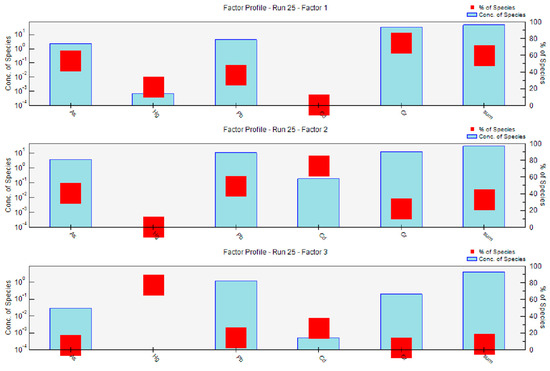

3.4.3. PMF Heavy Metal Quantitative Source Analysis

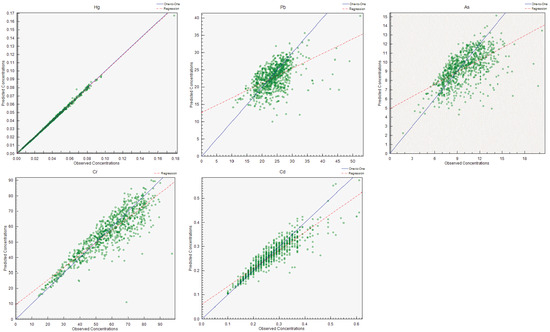

The PMF model was employed to assess the origins of heavy metals in cultivated soil in Ningxia [26]. Experimental data were inputted into the EPA PMF 5.0 software. Pollution factors with a signal-to-noise ratio exceeding 1 were considered “strong” variables. The model was configured to include 3 to 7 factors, model was iterated at least 100 times. The optimal number of factors was determined by comparing Qrob/Qexp values, where Qrob represents the optimal solution of the objective function Q obtained in Robust mode, and Qexp represents the true value of objective function Q. The model performed best with three factors, as indicated by minimal discrepancies between Qrobust and Qtrue, standard residuals of each element falling within the range of −3 to 3, and optimal fit. The fitting results of the measured values and the predicted values of the model are shown in Figure 5. The determination coefficients of all heavy metals were higher than 0.6, indicating that the PMF model has a good fitting effect. Therefore, the model meets the research needs, and the number of factors can fully explain the information contained in the original data. These findings are summarized in Table 5, demonstrating that the selected number of factors in the PMF model effectively captures the information within the original dataset.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of observed concentrations and predicted values.

Table 5.

Presents the fitting results comparing measured values with simulated predicted values of soil heavy metal content.

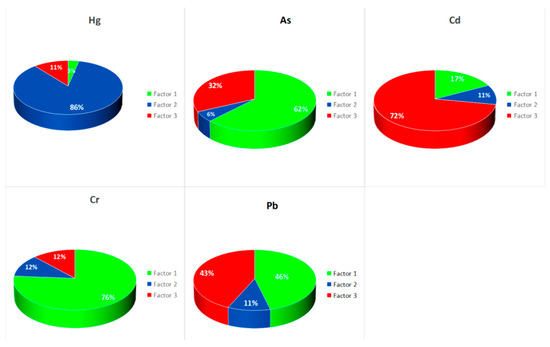

The analysis of Figure 6 and Figure 7 reveals that factor 1 significantly contributes to As, Pb, and Cr at rates of 62.5%, 46.1%, and 76.2%, respectively. These elements exhibit a strong correlation at a significance level of 1%, suggesting a common pollution source. Previous research has identified natural and anthropogenic sources of As in soil, with As-containing oxides and sulfide rocks migrating to cultivated soil layers through weathering and erosion processes [27,28]. The average As content in cultivated land in Ningxia (9.91 mg/kg) is notably lower than the regional soil’s background value for heavy metals (11.9 mg/kg), indicating a potential contribution from natural parent materials. Pb serves as a key indicator of traffic-related emissions, particularly from vehicular combustion [29]. Given the proximity of a substantial portion of cultivated land to roadways, Pb contamination in cultivated soil is plausible. Conversely, Cr is commonly associated with soil parent material composition and is typically considered a low-level pollutant [30]. Analysis in Table 3 and Table 4 indicates that the ecological risk index for Cr suggests a minor risk level, with 99.76% of samples exhibiting non-polluted levels based on the geoaccumulation index. Consequently, factor 1 is inferred to originate from a combination of transportation-related sources and natural parent materials.

Figure 6.

Illustrates the contribution rates of heavy metal pollution sources in the soils of the study area.

Figure 7.

Contribution of PMF source analysis of heavy metals.

Factor 2 significantly contributes to the presence of mercury (Hg) at a rate of 85.7%. An evaluation of potential ecological risk indicates that 38.05% of the sampled sites exhibit Hg pollution, with Hg displaying the highest coefficient of variation in the research area, suggesting substantial impact from human activities on cultivated soil. Previous research has established a correlation between Hg contamination and coal combustion [31]. The northern region of the study area is characterized by a thriving energy sector. Emissions from processing facilities, including airborne chromium compounds, lead to varying degrees of heavy metal contamination in the surrounding soil through dry and wet deposition of industrial emissions [32,33]. This contaminated soil is a primary source of pollution for crops, particularly vegetables. Field investigations and sampling in the study area have uncovered instances of unauthorized discharge of untreated or substandard industrial wastewater into agricultural channels via concealed pipelines [34]. Consequently, farmers irrigate their fields with polluted water, resulting in Hg accumulation in the soil. Furthermore, there are instances of haphazardly disposed industrial waste materials (e.g., smelting by-products and electroplating residues) near some sampled cultivated areas, facilitating Hg infiltration into the soil through runoff. Hence, Factor 2 is identified as an industrial contamination source.

Factor 3 accounted for 72.1% of the cadmium (Cd) content. The average Cd levels exceed the background levels in Ningxia soil, indicating potential influence from human activities. Previous research suggests that agricultural practices can result in Cd accumulation in soil [35,36,37,38]. The Yinchuan Plain, a significant grain-producing region in northwest China with a long history of agricultural development, exhibits substantial fertilizer usage, suggesting a plausible link between Cd levels and agricultural activities in the area. Cd, a prominent component of pesticides and fertilizers, is prone to migration and volatilization. Prolonged use of these substances can lead to Cd buildup in the soil [38]. Furthermore, certain agricultural inputs, such as livestock manure, may also contain Cd, possibly originating from feed additives [39,40]. Excessive application of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and organic fertilizers poses a significant risk of Cd pollution in cultivated lands [41]. Data from the Ningxia Statistical Yearbook indicates an annual application of approximately 900,000 tons of chemical fertilizers in cultivated soil, which can result in cumulative effects over time. Therefore, Factor 3 is identified as originating from agricultural production activities.

In summary, the apportionment of the three source factors to the presence of the five heavy metals is as follows: Arsenic (As), Lead (Pb), and Chromium (Cr) predominantly originated from a combination of transportation sources and natural parent materials, Mercury (Hg) primarily stemmed from industrial activities, and Cadmium (Cd) chiefly emanated from agricultural practices.

4. Discussion

4.1. Heavy Metal Pollution Status and Risk Assessment of Cultivated Soil in Ningxia

Ningxia, a significant agricultural region in northwest China, has witnessed a notable trend towards scale and distinctive characteristics in agricultural development in recent years. However, the prolonged application of agricultural inputs and the rapid urbanization at the county level have led to the emergence of heavy metal pollution issues in cultivated soil within certain irrigation areas. The ranking of over-standard rates is as follows: Cd (98.7%) > Hg (80.1%) > Pb (77.5%) > Cr (47.6%) > As (21.5%). The notably high over-standard rates suggest varying degrees of human-induced impacts on As, Hg, Pb, Cd, and Cr, with Cd, Hg, and Pb showing particularly significant accumulation, mirroring the broader pollution scenario observed in cultivated soil across China. The study findings reveal that the heavy metal pollution in Ningxia’s cultivated land exhibits characteristics of “localized distribution and clustered occurrences.” The pollution hotspots are predominantly situated in the northwest and central regions of Ningxia, primarily around the outskirts of Shizuishan, Yinchuan, Wuzhong, and other longstanding industrial zones, as well as in areas with extensive historical high-intensity cultivation within the Yellow River irrigation zone. The sources of pollution can be attributed to past industrial discharges, sewage irrigation practices, and human activities such as excessive utilization of plastic film, pesticides, and fertilizers. These factors have led to the accumulation of heavy metals, particularly Cd and Hg, in the cultivated soil of Ningxia. Additionally, Non-point agricultural inputs of Cd (e.g., fertilizers and other agro-inputs) result in a widespread, relatively uniform uplift of background levels. By contrast, Hg and Pb arise mainly from industrial, combustion, and smelting emissions, yielding more pronounced hotspot–coldspot mosaics and lower area-wide means than Cd, Consequently, cropland soils exhibit the accumulation hierarchy Cd > Hg > Pb.

Based on the current pollution scenario, Cd and Hg are the predominant contaminants in cultivated soil in Ningxia. It is imperative to enhance ongoing monitoring of soil sites, establish prompt emergency monitoring protocols, promptly identify emerging pollution and diffusion risks, and implement tailored safety measures for the sustainable management of heavy metal-contaminated soil. These actions, informed by the ecological risks associated with heavy metal pollution in soil and the sources of such pollution, are essential for safeguarding the environmental integrity of cultivated soil in Ningxia and ensuring the safe production of agricultural goods.

4.2. Analysis of Heavy Metal Sources in Cultivated Soil of Ningxia

The fragile agricultural ecological environment in Ningxia is characterized by low soil fertility and a risk of heavy metal accumulation, making the analysis of heavy metal pollution sources in cultivated land is crucial for enhancing agricultural productivity. Through Pearson analysis, it was revealed that the salt content in Ningxia’s cultivated soil exhibited a significant negative correlation with four heavy metals [42]. This phenomenon can be attributed to certain anions present in salt can form soluble complexes with heavy metal ions, thereby decreasing the adsorption tendency of heavy metals by soil solids and increasing their solubility and mobility in the solution [43,44]. Conversely, a notable positive correlation was observed between soil organic matter and the four heavy metals, Soil particles with low organic matter content carry fewer net negative charges, making it challenging for them to bind with positively charged heavy metals [45]. This circumstance may result in some free heavy metal ions in the soil solution being absorbed by plants. Additionally, this observation aligns with the significant positive correlation between CEC and the four heavy metals as indicated by the Pearson analysis [46,47], the high CEC can capture heavy metal cations through electrostatic adsorption, thereby reducing their free concentration in the soil solution [48]. Higher pH values and alkaline cation content favor metal accumulation [49,50].

Based on Pearson analysis, PCL and PMF model analysis, 820 cultivated soils were classified into three groups based on heavy metal content [51]. The first group comprised As, Pb, and Cr, originating mainly from a combination of transportation sources and natural parent materials [52]. The findings indicated that As and Pb were primarily derived from automobile exhaust emissions and soil parent materials, entering cultivated soil through atmospheric deposition and rain leaching. Cr in cultivated soil predominantly originated from the weathering of soil-forming parent materials, explaining the spatial distribution patterns of As, Pb, and Cr in the study. In the first component (PC1), with higher loading values, the contribution rates of the three components were 62.5%, 46.1%, and 76.2%, respectively, showing significant correlations among the three heavy metals, suggesting similar migration patterns and sources. Furthermore, Cr, Pb, and As exhibited minimal spatial variation, indicating their retention of the original natural state in the soil, primarily influenced by parent materials. Category II focused on Hg, primarily sourced from industrial activities. Hg exhibited the highest factor loading (0.956) in the second component (PC2), contributing 85.70% of the variance. Hg displayed the largest coefficient of variation (0.47), indicating that Hg pollution in cultivated soil primarily stemmed from natural sources and intense human activities [52,53], posing direct threats to the safety of agricultural products. The spatial distribution of sampling points indicated the presence of numerous factories and enterprises surrounding the Hg-polluted cultivated land, particularly concentrated processing enterprise bases in highly polluted areas, attributing Hg accumulation in cultivated soil to industrial production activities [54]. The strengthening of the industrial development model of “agglomeration” in northern Ningxia, particularly the dispersion of smelting dust from coal-fired power generation, oil production, and garbage incineration enterprises into farmland through atmospheric, wet, or dry deposition, resulted in Hg accumulation, consistent with the spatial distribution characteristics of Hg. Category III focused on Cd, primarily originating from agricultural activities. In the third principal component (PC3), Cd exhibited the highest factor loading value (0.990), contributing 72.1% of the variance, with substantial spatial variation (0.30), indicating significant human-induced influences on Cd levels, widely distributed in high-value areas across the study area. The findings indicated that Cd in cultivated soil primarily resulted from agricultural practices, with excessive use of chemical and organic fertilizers leading to Cd accumulation. Long-term production of microplastics from agricultural residual film was positively correlated with heavy metal accumulation [54], contributing to Cd pollution in cultivated soil over time.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The concentrations of five heavy metals in cultivated soil in Ningxia were below the threshold values for agricultural soil pollution risk. However, the average levels of Cd, Pb, and Hg exceeded the background levels of Ningxia soil, with Cd and As approaching the threshold values for agricultural soil pollution risk. Given that heavy metals are significant contributors to adult carcinogenic risk [54], continuous long-term monitoring is essential.

- (2)

- The single-factor index method and Nemerow comprehensive pollution index method indicated that, overall, the cultivated soil in Ningxia was deemed clean. However, Cd and Hg elements still exhibited medium to high potential ecological risks. The cumulative index analysis revealed that Cd and Hg are the primary heavy metal pollutants in Ningxia’s cultivated soil, posing significant toxicity levels that can adversely impact plant health across various pollution levels [55], Particular concern is the compounded pollution of agricultural land due to the synergistic effects of emerging contaminants like microplastics and antibiotics, in addition to heavy metals, retained in the agricultural production processes.

- (3)

- The spatial distribution patterns of heavy metals in cultivated soil in Ningxia exhibited distinct characteristics. Arsenic (As) and Chromium (Cr) displayed continuous high concentrations in the northern and western regions of the study area. Mercury (Hg) exhibited persistent high levels in the northern and eastern parts of the study area. Cadmium (Cd) showed continuous high concentrations in the central region, with elevated levels also observed in certain areas in the northern and southern parts of the study area. Lead (Pb) concentrations were predominantly high in the central and northern regions of the study area.

- (4)

- A notable inverse relationship was observed between soil salinity and heavy metal concentrations in cultivated soil, while a substantial positive correlation was noted between soil cation exchange capacity and heavy metal levels in the same soil [56]. Analysis using Pearson correlation, principal component analysis (PCA), and positive matrix factorization (PMF) indicated that arsenic (As), lead (Pb), and chromium (Cr) predominantly originated from a combination of transportation activities and natural parent materials [57,58], mercury (Hg) primarily originated from industrial sources [59], and cadmium (Cd) mainly originated from agricultural activities [60,61,62]. Accordingly, we recommend source-specific mitigation and long-term surveillance to manage cumulative risks.

Author Contributions

X.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, visualization. R.S.: Processed and analyzed the core experimental data, supervision. J.M. (Jianjun Ma): funding acquisition, supervision, resources. H.L.: data curation, formal analysis. T.M.: methodology, resources. J.M. (Junhua Ma): data curation, visualization. X.L.: data curation, software. C.M.: software, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2023BEG01002).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Classification standard of Nemero index evaluation method.

Table A1.

Classification standard of Nemero index evaluation method.

| Classification | Pi | PN | Pollution Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | P | P | Safe |

| II | 0.7 < P | 0.7 < P | Low |

| III | 1.0 < P | 1.0 < P | Moderate |

| IV | 2.0 < P | 2.0 < P | High |

| V | Pi > 3.0 | P | Very high |

Table A2.

Classification and hazard class of heavy metal potential ecological hazard index.

Table A2.

Classification and hazard class of heavy metal potential ecological hazard index.

| RI | Classification of Potential Ecological Risk Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| ≦40 | RI ≦ 150 | Low |

| 40 < ≦ 80 | 150 < RI ≦ 300 | Moderate |

| 80 < ≦ 160 | 300 < RI ≦ 600 | Considerable |

| 160 < ≦ 320 | 600 < RI ≦ 1200 | High |

| >320 | RI > 1200 | Very high |

References

- Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Teng, Y. Soil environmental quality in greenhouse vegetable production systems in eastern China: Current status and management strategies. Chemosphere 2017, 170, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection. Bulletin of the National Survey on Soil Pollution; Ministry of Land and Resources: Beijing, China; Ministry of Environmental Protection: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lu, Z. Assessment of ecological risks and spatiotemporal monitoring of heavy metal contamination in cultivated soils of the Liaohe River Basin, Jilin Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 968, 178870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.; Drosos, M.; Jiao, M.; Sun, J.; Li, G.; He, L.; Liu, Z. Heavy metal contamination threats carbon sequestration of paddy soils with an attenuated microbial anabolism. Geoderma 2025, 461, 117486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Kang, C.; Ren, D.; Zhang, L. Assessment of the variation of heavy metal pollutants in soil and crop plants through field and laboratory tests. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirvu, F.; Pascu, L.F.; Paun, I.; Stoica, C.; Iancu, V.I.; Niculescu, M.; Chiriac, F.L. Sorption of PAHs onto microplastics in Romanian surface waters and sediments: Environmental toxicity and human health risk with emphasis on pediatric exposure. Water Res. 2025, 287, 124483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohiagu, F.O.; Chikezie, P.C.; Ahaneku, C.C.; Chikezie, C.M. Human exposure to heavy metals: Toxicity mechanisms and health implications. Mater. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2022, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A. Investigated the impact of heavy metal contamination on agricultural soil, focusing on its effects on crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, C.; Tang, L.; Bai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, B. Priority areas identification for arable soil pollution prevention based on the accumulative risk of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R.; Biswas, B.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Singh, B.K. Bioremediation of heavy metal (loid) s in agricultural soils and crops. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhai, M.; Chen, J. Conducted a meta-analysis on the impact of metal mining on heavy metal concentrations in soils in the Kuangqu region of Southwest China. Environ. Sci. 2021, 42, 4414–4421. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Cheng, Z.; Su, L. Pollution characteristics, spatial distributions, and source apportionment of heavy metals in cultivated soil in Lanzhou, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracamonte-Terán, J.A.; Meza-Figueroa, D.; García-Rico, L.; Schiavo, B.; Meza-Montenegro, M.M.; Valenzuela-Quintanar, A.I. Agricultural abandoned lands as emission sources of dust containing metals and pesticides in the Sonora-Arizona Desert. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Hao, M.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Contamination, sources and health risks of toxic elements in soils of karstic urban parks based on Monte Carlo simulation combined with a receptor model. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 156223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetry, P.; Konwar, T.; Kumari, P.; Kalita, U. Heavy Metal Toxicity: A Challenge for Future Food Security. In Global Perspectives of Toxic Metals in Bio Environs: Volume 1: Environmental Impact, Ecotoxicology, Health Concerns, and Modelling; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, B.; Ma, T.; Wu, W.; Shi, R. A novel evaluation of farmland soil environmental risk integrating heavy metal (loid) pollution risk and industrial risk potential. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 3085–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, E.; Xu, E.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C. Temporal-spatial trends in potentially toxic trace element pollution in farmland soil in the major grain-producing regions of China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhai, J.; Yan, D.; Lin, Z. Regional disparities and technological approaches in heavy metal remediation: A comprehensive analysis of soil contamination in Asia. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanson, L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Res. 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar]

- National Environmental Protection Agency of China (NEPA); China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC). Background Values of Soil Elements in China; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sulieman, M.M.; Kaya, F.; Keshavarzi, A.; Hussein, A.M.; Al-Farraj, A.S.; Brevik, E.C. Spatial variability of some heavy metals in arid harrats soils: Combining machine learning algorithms and synthetic indexes based-multitemporal Landsat 8/9 to establish background levels. Catena 2024, 234, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Li, T.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Current status of agricultural soil pollution by heavy metals in China: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 3034–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravish, S.; Setia, B.; Deswal, S.; Puri, V.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.; Yadav, A.K. Improving the estimation precision of the mapping of groundwater salinity by employing the Indicator Kriging Technique. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shi, Z.; Yu, L.; Fan, H.; Wan, F. Soil Quality and Heavy Metal Source Analyses for Characteristic Agricultural Products in Luzuo Town, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qian, H.; Xu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Hou, K.; Chen, Y. Distribution characteristics, source identification and risk assessment of heavy metals in surface sediments of the Yellow River, China. Catena 2022, 216, 106376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zha, T.; Guo, X.; Meng, G.; Zhou, J. Spatial distribution of metal pollution of soils of Chinese provincial capital cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Pan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, R.; Shen, Z.; Dong, S. Risk assessment of soil heavy metals associated with land use variations in the riparian zones of a typical urban river gradient. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 181, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bi, Z.; Yu, Y.; Shi, P.; Ren, L.; Shan, Z. The impact of land use changes and erosion process on heavy metal distribution in the hilly area of the Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Hou, D.W.; Li, F.Z.; Bao, G.J.; Deng, A.P.; Shen, H.J.; Sun, H. Assessment and spatial characteristics analysis of human health risk of heavy metals in cultivated soil. Environ. Sci. 2020, 41, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, J.; Li, W.; Diao, C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Haider, G.; Chen, H. Microplastics drive microbial assembly, their interactions, and metagenomic functions in two soils with distinct pH and heavy metal availability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Cheng, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, D. Effects of natural factors on the spatial distribution of heavy metals in soils surrounding mining regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygın, F. Determination of heavy metal concentrations in cultivated soils and prediction of pollution risk ındices using the ANN approach. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2024, 35, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, S.; Chen, Y.; Shao, S.; Wu, J.; Fan, M.; Gao, C. Machine learning-based source identification and spatial prediction of heavy metals in soil in a rapid urbanization area, eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyiramigisha, P.; Komariah; Sajidan. Harmful effects of heavy metal contamination in soil and crops near landfill sites. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2021, 9, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Xue, N.; Han, Z. A meta-analysis of heavy metals pollution in farmland and urban soils in China over the past 20 years. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 101, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, J.; Chen, X.; Guo, X.; Guo, S.; Xu, L.; Lin, Z. Environmental risk and source analysis of heavy metals in tailings sand and surrounding soils in Huangshaping mining area. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2024, 36, 2395559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. Accumulation and health risks of heavy metals in the surface soil of cultivated land. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jia, Z.; Li, S.; Hu, J. Assessment of heavy metal pollution, distribution and quantitative source apportionment in surface sediments along a partially mixed estuary (Modaomen, China). Chemosphere 2019, 225, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Cao, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, D.; Wu, D. Sources analysis and risk assessment of heavy metals in soil in a polymetallic mining area in southeastern Hubei based on Monte Carlo simulation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y. Determining the priority control factor of toxic metals in cascade reservoir sediments via source-oriented ecological risk assessment. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.J.; Li, J.Q.; Li, C.X.; Liao, Z.Y.; Mei, N.; Luo, C.Z.; Wang, D.-Y.; Zhang, C. Pollution source apportionment of heavy metals in cultivated soil around a red mud yard based on APCS-MLR and PMF models. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, X.; Chen, T.; Liao, X.; Song, J.; Wu, B. Heavy metal pollution of soils and vegetables in the midstream and downstream of the Xiangjiang River, Hunan Province. J. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 18, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, H.; Fei, Y.; Wang, C.; Mo, L.; Shu, M. Identification of soil heavy metal sources in a large-scale area affected by industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.Q.; Zeng, X.M.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y.R. Characteristics and assessment of heavy metal contamination in soils of industrial regions in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Environ. Sci. 2022, 43, 2062–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, B.N.; Wang, C.; Shi, H.D.; Li, M.Q. Analysis of heavy metal pollution sources in cultivated land soil based on receptor model and geostatistics. Res. Environ. Sci. 2021, 34, 2962–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liao, X.; Zhao, F.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Q. Precise and differentiated solutions for safe usage of Cd-polluted paddy fields at regional scale in southern China: Technical methods and field validation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Chen, F.; Liu, G.J.; Raveloaritiana, E.; Wanger, T.C. Fallow priority areas for spatial trade-offs between cost and efficiency in China. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Hu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Guo, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, G. Geo-detection of factors controlling spatial patterns of heavy metals in urban topsoil using multi-source data. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Feng, H.; Bao, L.; Zhang, Y. Distribution Characteristics and Risk Assessment of Soil Heavy Metals in Northwest Chongqing. J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2018, 40, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Heavy metal pollution risk of cultivated land from industrial production in China: Spatial pattern and its enlightenment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, R.; Kalaiyarasi, G.; Saritha, B. Heavy metal contamination in soils: Risks and remediation. Soil Fertil. Plant Nutr. 2024, 141, 141–255. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.J.; Opp, C.; Prume, J.A.; Koch, M.; Chifflard, P. Meso-and microplastic distribution and spatial connections to heavy metal contaminations in highly cultivated and urbanised floodplain soilscapes–a case study from the Nidda River (Germany). Microplastics Nanoplastics 2022, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, W.; Chen, J. Multivariate statistical analysis and risk assessment of dissolved trace metal (loid) s in the cascade-dammed Lancang River. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 172, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Wu, G. Impact of coal power generation on the characteristics and risk of heavy metal pollution in nearby soil. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1787092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaszczyk, W.; Szlachta, A.; Łyszczarz, S.; Szymański, N.; Jasik, M.; Żelazny, M.; Błońska, E. The effect of soil chemical properties and ecological implications on the distribution of heavy metals in different types of peatland. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Dai Jie, L.I.; Zhang, F.; Deng, L. Classification and Risk Management of Cultivated Land Environmental Quality Based on Evaluation of Soil Heavy Metal Pollution and Accumulation. Ecol. Environ. 2025, 34, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Cai, L.M.; Wen, H.H.; Luo, J.; Wang, Q.S.; Liu, X. Spatial distribution and source apportionment of heavy metals in soil from a typical county-level city of Guangdong Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, Y. Probabilistic-fuzzy risk assessment and source analysis of heavy metals in soil considering uncertainty: A case study of Jinling Reservoir in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 222, 112537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Sun, J.; Shaghaleh, H.; Jiang, X.; Yu, H.; Zhai, S.; Hamoud, Y.A. Environmental assessment of soils and crops based on heavy metal risk analysis in Southeastern China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selahvarzi, M.; Sobhan Ardakani, S.; Hemmasi, A.H.; Taghavi, L.; Ghoddousi, J. Analysis, spatial distribution and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in surface soils, the case of Khorramabad, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 104, 8955–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Chakraborty, S. Influence of soil characteristics and agricultural practices on microplastic concentrations in sandy soils and their association with heavy metal contamination. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 197, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).