Predicting Current and Future Potential Distributions of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in China Based on the MaxEnt Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

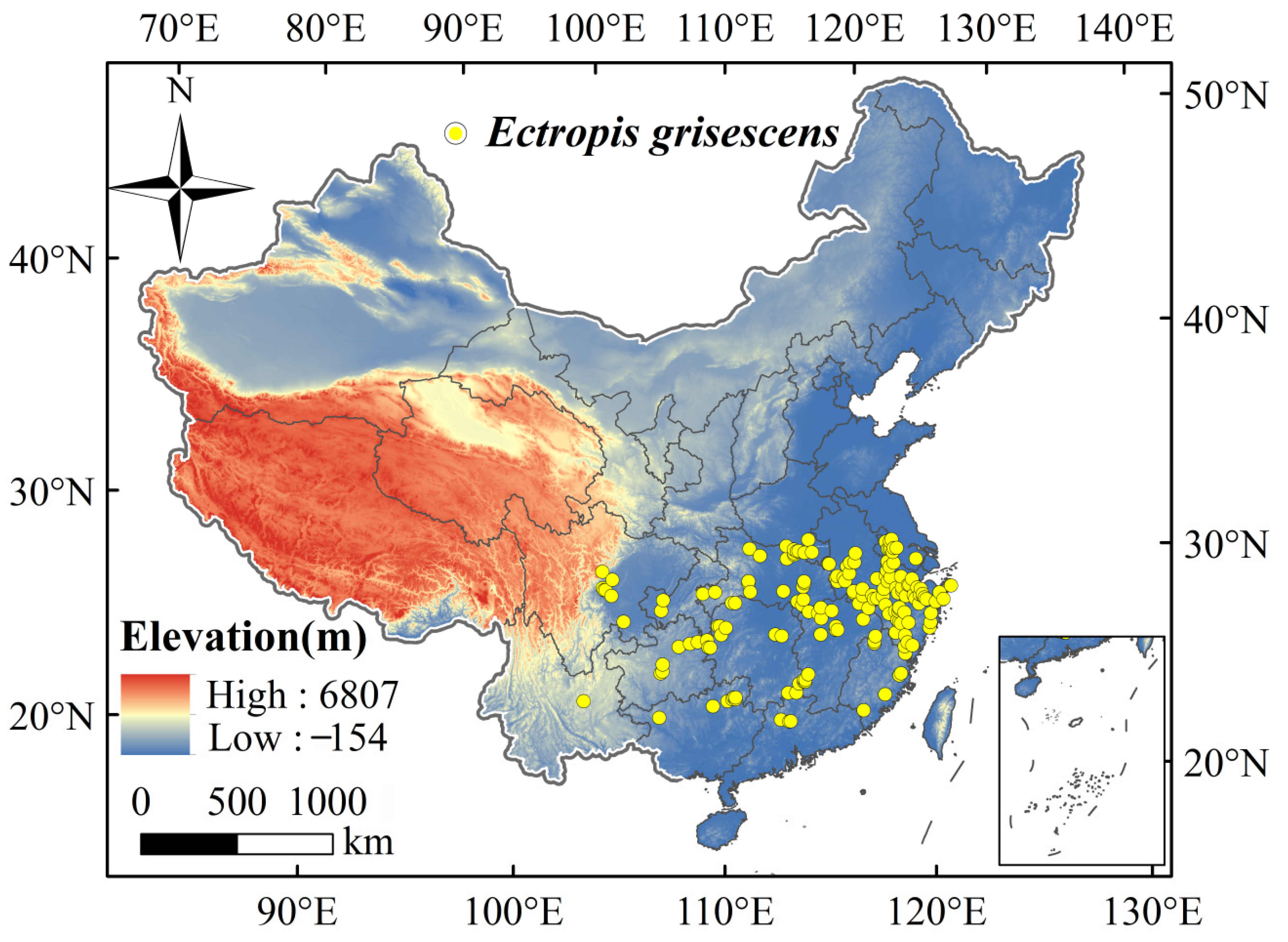

2.1. Collection of Species Occurrence Records

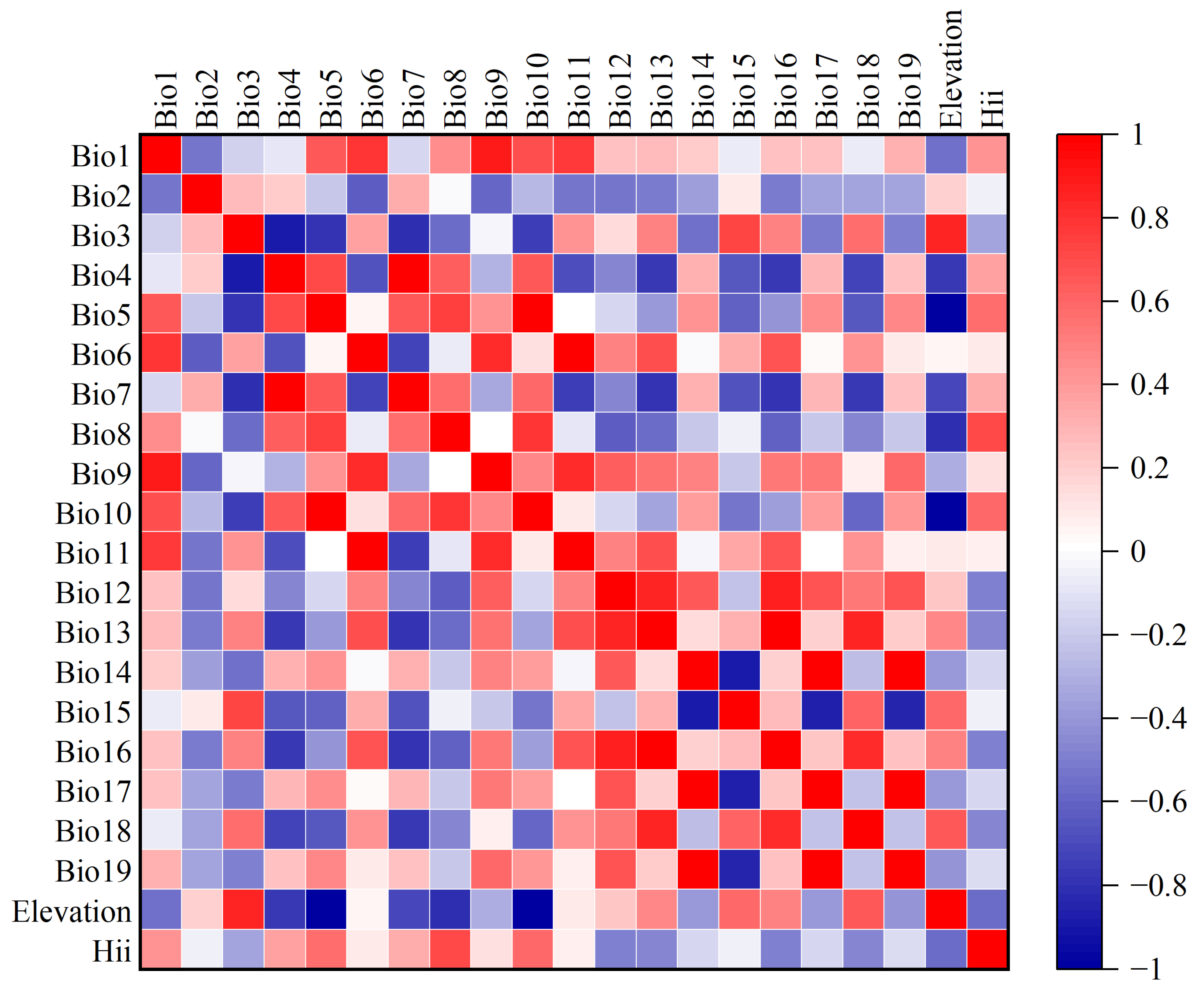

2.2. Variable Environment Selection and Data Processing

2.3. Model Construction, Optimization, and Accuracy Evaluation

2.4. Classification of Suitable Regions and Model Reliability Test

2.5. Comparison and Analysis of Current and Future Potential Distribution

2.6. Core Distributional Shifts

3. Results

3.1. Model Accuracy

3.2. Important Environmental Variables

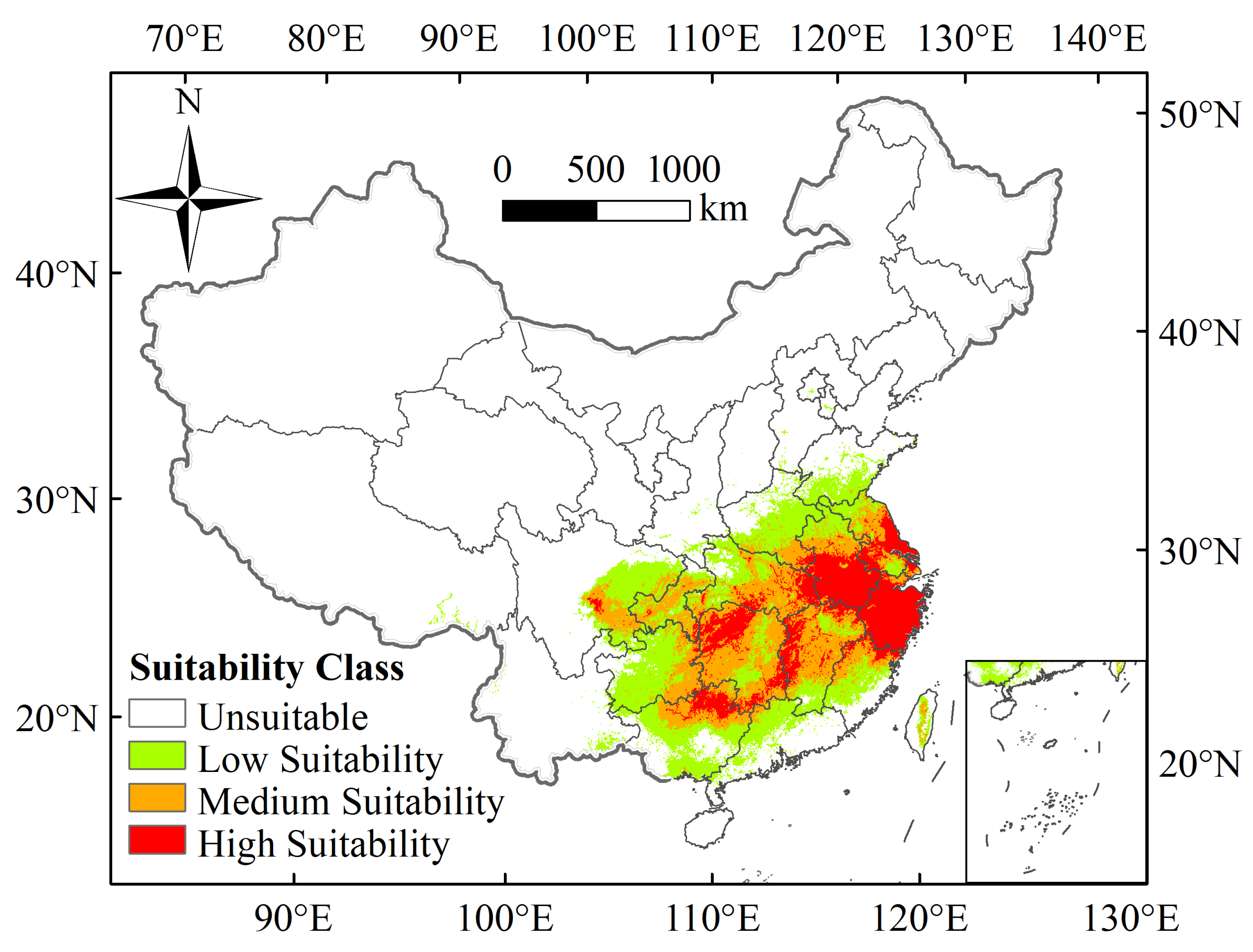

3.3. The Current Geographical Distribution of Ectropis Grisescens

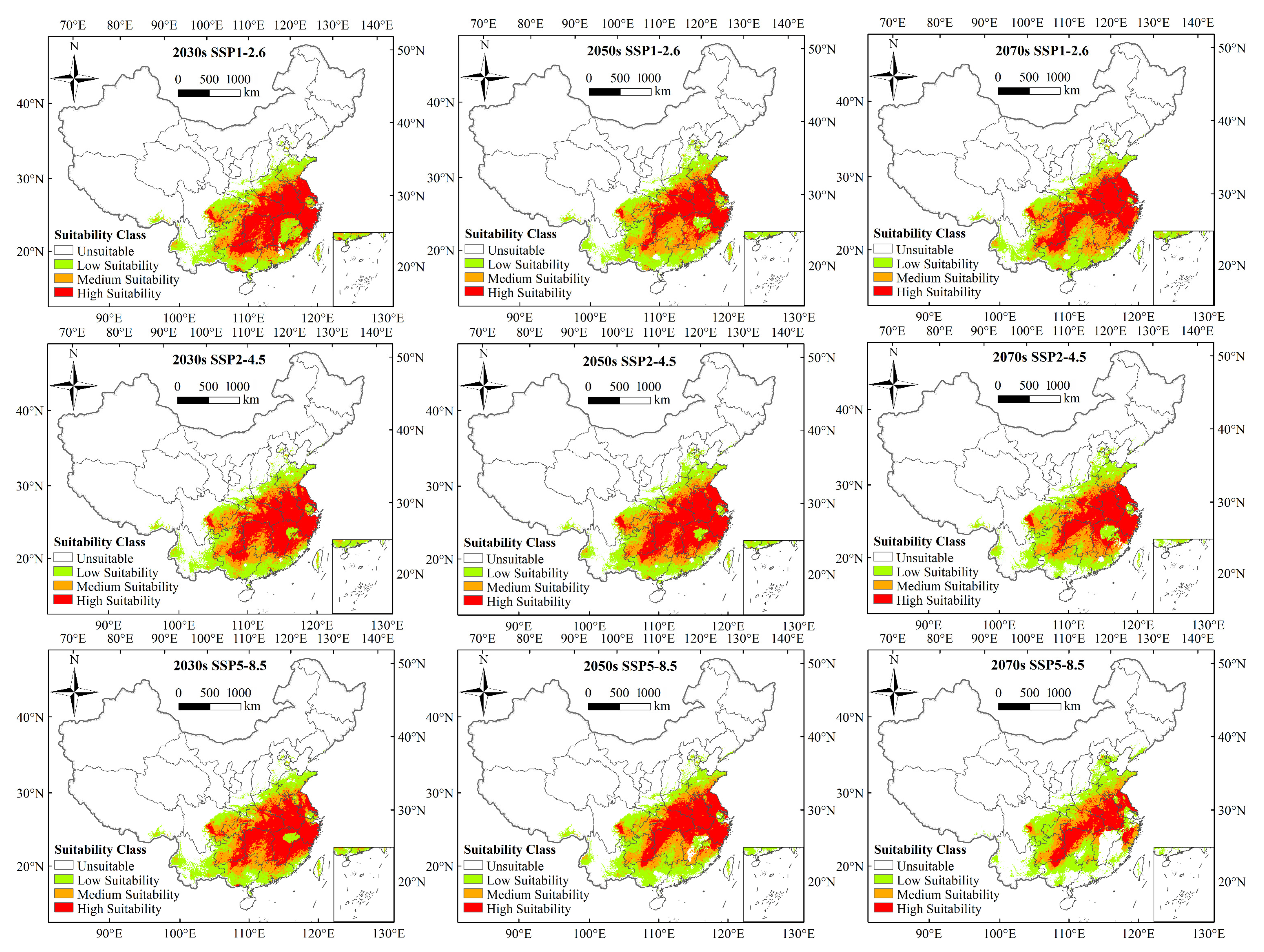

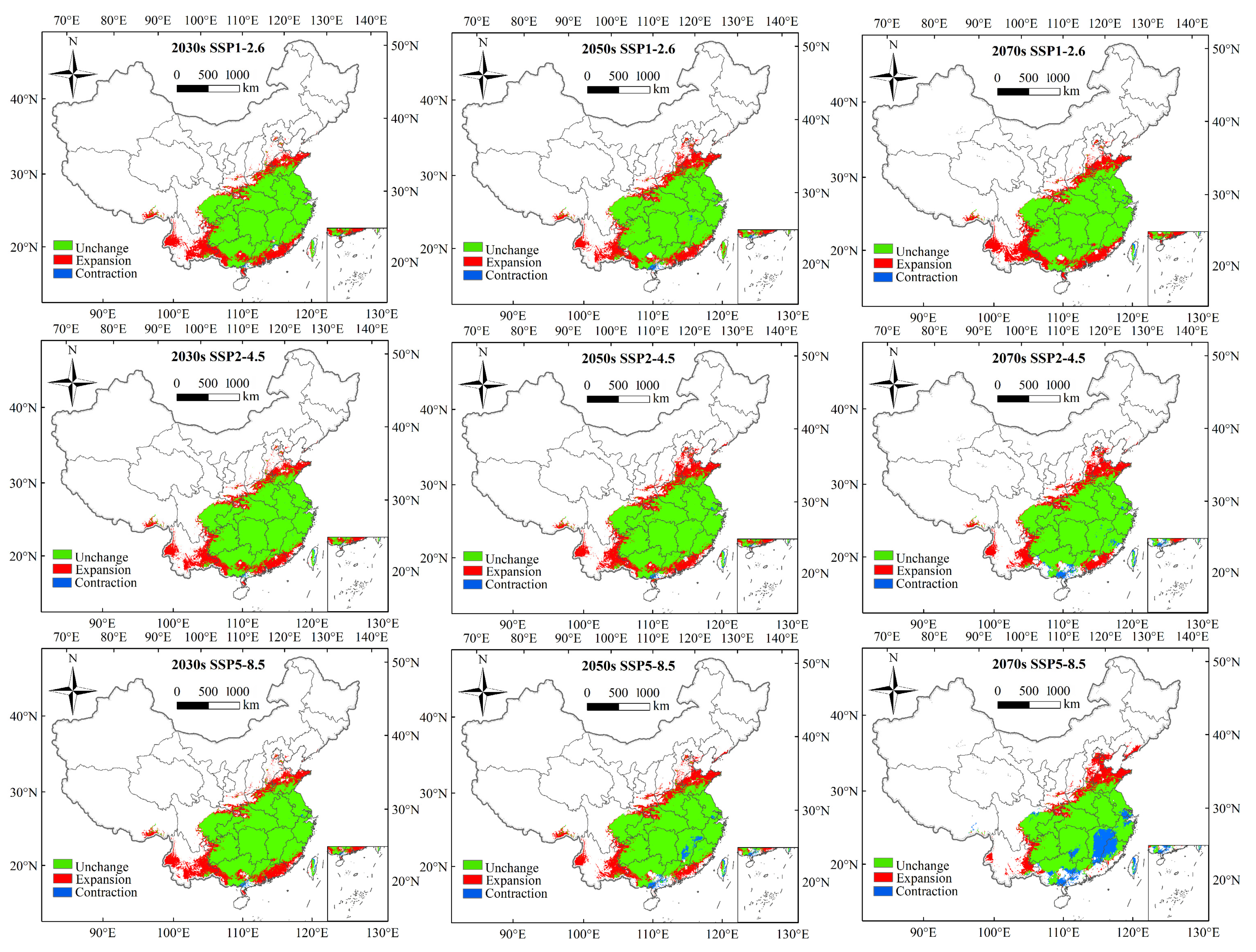

3.4. Future Potential Suitable Areas for Ectropis Grisescens

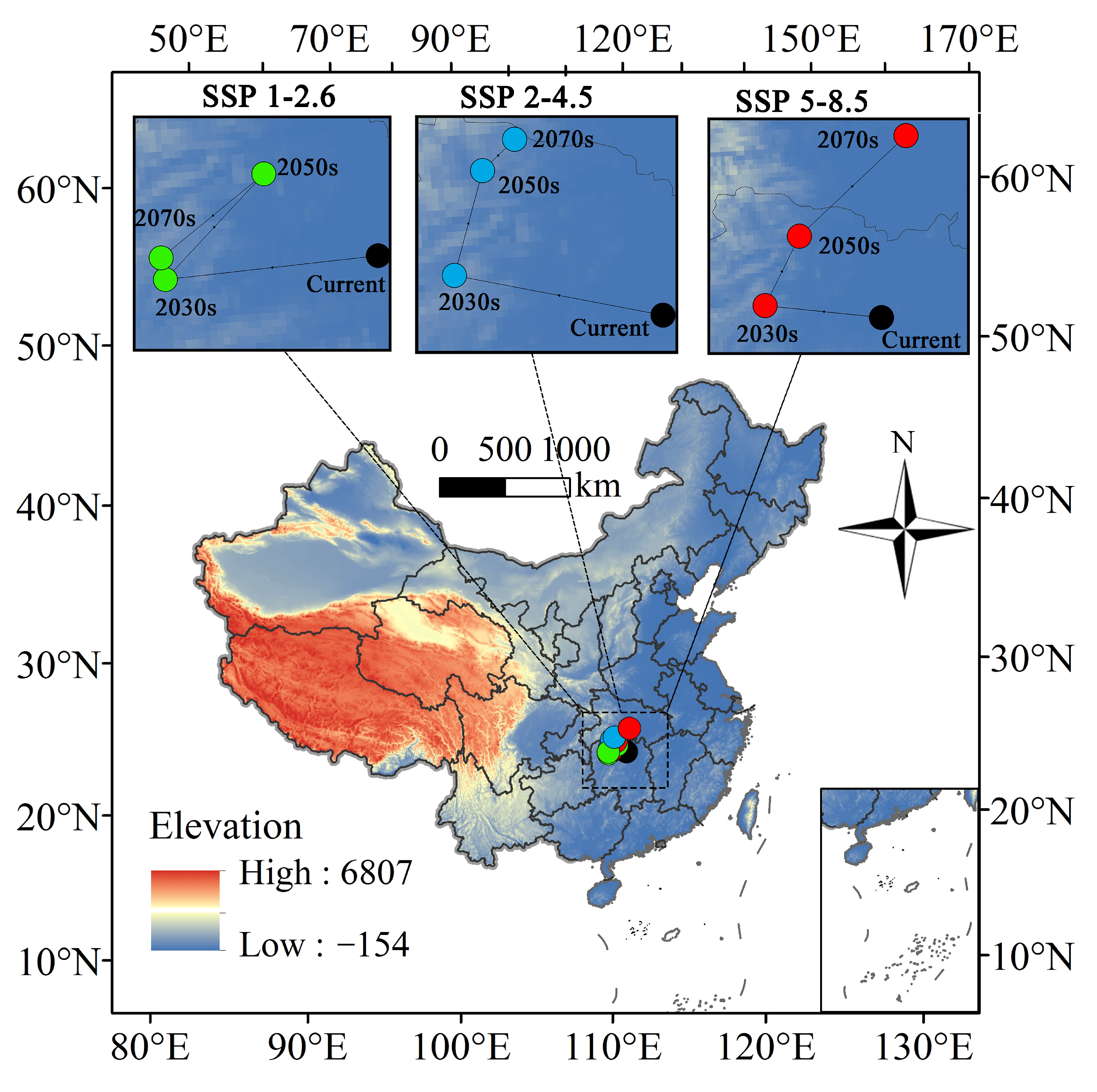

3.5. Movements of the Potential Suitable Area Centroid

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishnaraj, T.; Gajjeraman, P.; Palanisamy, S.; Chandrabose, S.R.S.; Mandal, A.K.A. Identification of differentially expressed genes in dormant (banjhi) bud of tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) using subtractive hybridization approach. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Gao, L.; Xia, E.; Lu, Y.; Tai, Y.; She, G.; et al. Draft genome sequence of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis provides insights into the evolution of the tea genome and tea quality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E4151–E4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwar, T.; Baruah, I.; Chaudhary, M.K.; Bhuyan, R.P.; Sarmah, B.K. Evaluation of genetic diversity of tea Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze germplasm of Assam based on characterization of flavour related metabolites. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 7061–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayani, G.R.P.; Tularam, G.A. The tea industry and a review of its price modelling in major tea producing countries. J. Manag. Strategy 2016, 7, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Ma, X.; Lin, C.J.; Gao, X.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Kuang, Y.-F.; Wang, L.L.; Li, S.; Lin, C.; Chen, L.L. The application of demographic characteristics of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in pest risk assessment of IPM. J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Cai, X.M.; Luo, Z.X.; Bian, L.; Xin, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Chu, B.; Chen, Z.M. Geographical distribution of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) and Ectropis obliqua in China and description of an efficient identification method. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Lin, G.F.; Batool, K.; Zhang, S.Q.; Chen, M.F.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Jin, L.; Gelbic, I.; Xu, L.; et al. Alimentary tract transcriptome analysis of the tea geometrid, Ectropis oblique (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Gao, T.; Huang, Y.P.; Li, T.T.; Jiang, X.L.; Liu, Y.J.; Gao, L.P.; Xia, T. Deep learning and targeted metabolomics-based monitoring of chewing insects in tea plants and screening defense compounds. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X. Online SPE-UPLC-MS/MS to Establish Four Pyrethroid Pesticides in Tea and Lambda-Cyhalothrin Activity Differences of Ectropis Oblique Hypulina Wehrli. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Agricultural University, Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, C.; Dunk, J.R.; Moilanen, A. Optimizing resiliency of reserve networks to climate change: Multispecies conservation planning in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunisch, V.; Coppes, J.; Arlettaz, R.; Suchant, R.; Schmid, H.; Bollmann, K. Selecting from correlated climate variables: A major source of uncertainty for predicting species distributions under climate change. Ecography 2013, 36, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, A.E.; Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Fisher-Reid, M.C.; Hua, X.; Karanewsky, C.J.; Ryu, H.Y.; Sbeglia, G.C.; Spagnolo, F.; Waldron, J.B.; Warsi, O.; et al. How does climate change cause extinction? Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20121890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, X.Q.; Zhao, H.X.; Guo, J.Y.; Zhang, G.F.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.X.; Wan, F.H. Estimation of the potential geographical distribution of a new potato pest (Schrankia costaestrigalis) in China under climate change. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2441–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.J.; Xu, D.P.; Zhuo, Z.H. Predicting the impact of climate change on the geographical distribution of leafhopper, Cicadella viridis in China through the MaxEnt model. Insects 2023, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, L.; Song, C.; Xue, Z.; Zheng, R.; Yan, X.; Hao, C. Modelling potential distribution of Tuta absoluta in China under climate change using CLIMEX and MaxEnt. J. Appl. Entomol. 2023, 147, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, O.; Settele, J.; Kudrna, O.; Klotz, S.; Kuhn, I. Climate change can cause spatial mismatch of trophically interacting species. Ecology 2008, 89, 3472–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.X.; Fu, C.X.; Comes, H.P. Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: Tracing the genetic imprints of quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2011, 59, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, H.; Moilanen, A.; Araujo, M.B.; Cabeza, M. Conservation planning with uncertain climate change projections. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Record, S.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Finley, A.O.; Veloz, S.; Ellison, A.M. Should species distribution models account for spatial autocorrelation? a test of model projections across eight millennia of climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Hernández, A.F.; Monterroso-Rivas, A.I.; Granados-Sánchez, D.; Villanueva-Morales, A.; Santacruz-Carrillo, M. Projections for Mexico’s tropical rainforests considering ecological niche and climate change. Forests 2021, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, P.A.; Kumar, L.; Da Silva, R.S.; Picanço, M.C. Global geographic distribution of Tuta absoluta as affected by climate change. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, D.H.; Jung, S.; Lee, W. Review of CLIMEX and MaxEnt for studying species distribution in South Korea. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2018, 11, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Neven, L.G.; Zhu, H.Y.; Zhang, R.Z. Assessing the Global Risk of Establishment of Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) using CLIMEX and MaxEnt Niche Models. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: New extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yackulic, C.B.; Chandler, R.; Zipkin, E.F.; Royle, J.A.; Nichols, J.D.; Grant, E.H.C.; Veran, S. Presence-only modelling using MaxEnt: When can we trust the inferences? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 4, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaud, E.; Petitpierre, B.; Broennimann, O.; Davison, A.C.; Guisan, A. Measuring the relative effect of factors affecting species distribution model predictions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhu, B.; Cheng, X.F.; Yang, L.; Gao, M.K.; Kong, R. MaxEnt modeling based on CMIP6 models to project potential suitable zones for Cunninghamia lanceolata in China. Forests 2021, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.M.; Du, Q.L.; Yan, S.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; Guan, D.X.; Ma, L.Q. Geographical distribution of As-hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata in China: Environmental factors and climate changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Feng, X.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhou, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.B. Potential suitability areas of Sitobion miscanthi in China based on the MaxEnt model: Implications for management. Crop Prot. 2024, 183, 106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.X.; Meng, F.H.; Song, Y.Z.; Li, D.L.; Ji, Q.E.; Hong, Y.C.; Lin, J.; Cai, P.M. Forecasting the expansion of Bactrocera tsuneonis (Miyake) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China using the MaxEnt Model. Insects 2024, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.N.; Zhang, J.X.; Tan, C.; Zhu, X.; Cao, S.Y.; Gao, C.Q. Forecast of current and future distributions of Corythucha marmorata (Uhler) under climate change in China. Forests 2024, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.F.; Ma, T.; Xiao, Q.; Cao, P.R.; Chen, X.; Xiong, H.P.; Qin, W.Q.; Sun, Z.H.; Wen, X.J. Choice and no-choice bioassays to study the pupation preference and emergence success of Ectropis grisescens. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 140, e58126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.J.; Fang, G.Q.; Wang, Z.B.; Cao, Y.H.; Liu, Y.J.; Li, G.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Xiao, Q.; Zhan, S. Chromosome-level genome reference and genome editing of the tea geometrid. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 2034–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhao, X.C.; Guo, S.B.; Hong, F.; Zhi, Y.A.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhou, X.G.; et al. Antennal transcriptomic analysis of carboxylesterases and glutathione S-transferases associated with odorant degradation in the tea gray geometrid, Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera, Geometridae). Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1183610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.Y.; Wu, Y.K.; Tu, J.; Dong, F.; Dong, Y.; Xie, F. Cordyceps sp. WZFW1, a novel entomopathogenic fungus to control Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). Entomol. Res. 2024, 54, e12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Liu, Y.L.; Qin, H.; Meng, Q.X. Prediction on spatial migration of suitable distribution of Elaeagnus mollis under climate change conditions in Shanxi Province, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. The Research and Conservation Programme of Papaveraceae habitatsuitability Based on the Optimized Biomod2 and Zonation Model in China. Master’s Thesis, Qinghai Normal University, Xining, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Ouyang, X.; Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Lin, H. Predicting the potential distribution of pine wilt disease in China under climate change. Insects 2022, 13, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, L.; Tao, J. Impact of climate change on the distribution of Euscaphis japonica (Staphyleaceae) trees. Forests 2020, 11, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Glor, R.E.; Turelli, M. ENMTools: A toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography 2010, 33, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisz, M.S.; Pottier, J.; Kissling, W.D.; Pellissier, L.; Svenning, J.C. The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: Implications for species distribution modelling. Biol. Rev. 2013, 88, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.W.; Wei, L.B.; Yeo, D.C.J. Novel methods to select environmental variables in MaxEnt: A case study using invasive crayfish. Ecol. Model. 2016, 341, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Schapire, R.E.; Blair, M.E. Opening the black box: An open-source release of Maxent. Ecography 2017, 40, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.X.; Jiang, N.Z.Y.; Li, C.; Li, J. Prediction of the current and future distribution of tomato leafminer in China using the MaxEnt model. Insects 2023, 14, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, J.M.; Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Bohl, C.L.; Pinilla-Buitrago, G.E.; Boria, R.A.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Anderson, R.P. ENMeval 2.0: Redesigned for customizable and reproducible modeling of species’ niches and distributions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Gao, X.; Ma, J.; Jiao, Z.H.; Xiao, J.H.; Hayat, M.A.; Wang, H.B. Modeling the present and future distribution of arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus under climate change scenarios in Mainland China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.P.; Yu, X.P.; Yu, C.Q.; Tayibazhaer, A.; Xu, F.J.; Skidmore, A.K.; Wang, T.J. Impacts of future climate and land cover changes on threatened mammals in the semi-arid Chinese Altai Mountains. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Seifert, S.N. Ecological niche modeling in Maxent: The importance of model complexity and the performance of model selection criteria. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, J.M. AUC: A misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 17, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Feng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhu, C. Prediction of the spatial distribution of Alternanthera philoxeroides in China based on ArcGIS and MaxEnt. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 21, e00856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcheglovitova, M.; Anderson, R.P. Estimating optimal complexity for ecological niche models: A jackknife approach for species with small sample sizes. Ecol. Model. 2013, 269, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.F.; Liu, Q.Z.; Ma, X.Y.; Liu, J. The impacts of climate change on the potential distribution of Cacopsylla chinensis (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in China. J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, 118, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Z.; Zhao, J.Y.; Hu, C.Y.; Ma, J.G.; Deng, C.P.; Ma, L.; Qie, X.T.; Yuan, X.Y.; Yan, X.Z. Predicting the current and future distribution of Monolepta signata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) based on the Maximum entropy model. Insects 2024, 15, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Bennett, J.R.; French, C.M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: The next generation Python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Peerj 2017, 5, e4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurell, D.; Franklin, J.; König, C.; Bouchet, P.J.; Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Fandos, G.; Feng, X.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Guisan, A.; et al. A standard protocol for reporting species distribution models. Ecography 2020, 43, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Godsoe, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; Wang, H.H.; Warren, D. Niche estimation above and below the species level. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castex, V.; Beniston, M.; Calanca, P.; Fleury, D.; Moreau, J. Pest management under climate change: The importance of understanding tritrophic relations. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.J.; Xu, D.P.; Liu, Q.W.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhuo, Z.H. Predicting the potential distribution range of Batocera horsfieldi under CMIP6 climate change using the MaxEnt model. J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Sun, J. Predicting the distribution of Stipa purpurea across the Tibetan Plateau via the MaxEnt model. BMC Ecol. 2018, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. Assessment of the impact of climate change on the habitat dynamics of Tetradium ruticarpum (A. Juss.) TG Hartley in China using MaxEnt model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Ding, S.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, G. Prediction of potential distribution and response of Changium smyrnioides to climate change based on optimized MaxEnt model. Plants 2025, 14, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, C.A.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Tigchelaar, M.; Battisti, D.S.; Merrill, S.C.; Huey, R.B.; Naylor, R.L. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 2018, 361, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skendzic, S.; Zovko, M.; Zivkovic, I.P.; Lesic, V.; Lemic, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Hou, H.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Yin, J.; Qiao, L. Effect of temperature on life table parameters of Ectropis grisescens experimental populations. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 36, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.; Chen, J. Effects of cold storage on pupae of tea geometridae (Ectropis oliqua Prout). J. China Jiliang Univ. 2008, 19, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Yin, K.; Tang, M.; Xiao, Q. Developmental threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature of Ectropis grisescens. Plant Prot. 2016, 42, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Y. Effect of temperature on the developmental duration of tea geometrid (Ectropis obliqua Prout). J. Tea Sci. 1993, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhuo, Z.; Yang, H.; Hu, J.; Wang, R. Influence of climatic factors on the potential distribution of pest Heortia vitessoides Moore in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Liang, S.P.; Ma, T.; Xiao, Q.; Cao, P.R.; Chen, X.; Qin, W.Q.; Xiong, H.P.; Sun, Z.H.; Wen, X.J.; et al. No-substrate and low-moisture conditions during pupating adversely affect Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) adults. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2018, 21, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantowijoyo, W.; Hoffmann, A.A. Identifying factors determining the altitudinal distribution of the invasive pest leafminers Liriomyza huidobrensis and Liriomyza sativae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2010, 135, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Min, Q. Analysis of landscape patterns changes and driving factors of the guangdong chaoan fenghuangdancong tea cultural system in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Liu, Z. Optimized maxent model predictions of climate change impacts on the suitable distribution of cunninghamia lanceolata in China. Forests 2020, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Han, K.; Lu, Y.; Wei, J. Predicting the potential distribution of the vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus under climate change by MaxEnt. Crop Prot. 2020, 137, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: Are bioclimate envelope models useful? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lei, M.; Wei, C.; Guo, X. Assessing the suitable regions and the key factors for three Cd-accumulating plants (Sedum alfredii, Phytolacca americana, and Hylotelephium spectabile) in China using MaxEnt model. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; You, W.W.; Guo, S.B.; Zhang, T.H.; Liu, T.F.; Du, Y.Q.; Shi, H.Z. Feeding selection and adaptability of Ectropis grisescens to four host plants. China Plant Prot. 2025, 45, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Percent Contribution (%) | Permutation Importance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Annual mean temperature (bio1, °C) | - | - |

| Mean diurnal range (bio2, °C) | 37.3 | 2.9 |

| Isothermality (bio3) | - | - |

| Temperature seasonality (standard deviation × 100, bio4) | 1.8 | 8.6 |

| Max temperature of warmest month (bio5, °C) | - | - |

| Min temperature of coldest month (bio6, °C) | - | - |

| Temperature annual range (bio7, mm) | - | - |

| Mean temperature of wettest quarter (bio8, °C) | - | - |

| Mean temperature of driest quarter (bio9, °C) | 13.6 | 48.6 |

| Mean temperature of warmest quarter (bio10, °C) | - | - |

| Mean temperature of coldest quarter (bio11, °C) | - | - |

| Annual precipitation (bio12, mm) | - | - |

| Precipitation of wettest month (bio13, mm) | - | - |

| Precipitation of driest month (bio14, mm) | 25.0 | 15.7 |

| Precipitation seasonality (bio15) | - | - |

| Precipitation of wettest quarter (bio16, mm) | - | - |

| Precipitation of driest quarter (bio17, mm) | - | - |

| Precipitation of warmest quarter (bio18, mm) | 0.9 | 4.3 |

| Precipitation of coldest quarter (bio19, mm) | - | - |

| Human influence index (Hii) | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| Elevation (m) | 18.8 | 18.7 |

| Climate Scenario | Decades | Predicted Area (km2) and % of the Corresponding Current Area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Suitable Area | Low Suitability Area | Medium Suitability Area | High Suitability Area | ||||||

| 1970–2000 | 1.969 × 106 | – | 5.121 × 105 | – | 7.385 × 105 | – | 7.185 × 105 | – | |

| SSP1-2.6 | 2030s | 2.174 × 106 | 110.39% | 7.450 × 105 | 145.50% | 5.322 × 105 | 72.07% | 8.963 × 105 | 124.75% |

| 2050s | 2.139 × 106 | 108.63% | 7.856 × 105 | 153.41% | 6.614 × 105 | 89.56% | 6.919 × 105 | 96.30% | |

| 2070s | 2.210 × 106 | 112.21% | 7.153 × 105 | 139.69% | 6.584 × 105 | 89.16% | 8.358 × 105 | 116.32% | |

| SSP2-4.5 | 2030s | 2.140 × 106 | 108.70% | 6.931 × 105 | 135.35% | 5.548 × 105 | 75.13% | 8.925 × 105 | 124.21% |

| 2050s | 2.187 × 106 | 111.08% | 7.189 × 105 | 140.40% | 5.512 × 105 | 74.64% | 9.170 × 105 | 127.63% | |

| 2070s | 2.096 × 106 | 106.42% | 7.970 × 105 | 155.65% | 5.667 × 105 | 76.74% | 7.318 × 105 | 101.85% | |

| SSP5-8.5 | 2030s | 2.144 × 106 | 108.90% | 7.142 × 105 | 139.48% | 5.835 × 105 | 79.01% | 8.467 × 105 | 117.83% |

| 2050s | 2.073 × 106 | 105.26% | 7.901 × 105 | 154.30% | 5.415 × 105 | 73.33% | 7.410 × 105 | 103.13% | |

| 2070s | 1.806 × 106 | 91.72% | 8.569 × 105 | 167.35% | 4.353 × 105 | 58.94% | 5.139 × 105 | 71.52% | |

| Climate Scenario | Decades | Predicted Area (km2) and % of the Corresponding Current Area | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Suitable Region | Contraction | Unchanged | Expansion | Range Change | Contraction Percentage | Expansion Percentage | ||

| 1970–2000 | 1.969 × 106 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| SSP1-2.6 | 2030s | 2.174 × 106 | 8.100 × 103 | 1.638 × 106 | 5.085 × 105 | 10.39% | 0.41% | 25.82% |

| 2050s | 2.139 × 106 | 1.630 × 104 | 1.630 × 106 | 5.073 × 105 | 0.09 | 0.83% | 25.76% | |

| 2070s | 2.210 × 106 | 6.500 × 103 | 1.653 × 106 | 5.508 × 105 | 0.12 | 0.33% | 27.97% | |

| SSP2-4.5 | 2030s | 2.140 × 106 | 6.800 × 103 | 1.639 × 106 | 4.967 × 105 | 0.09 | 0.35% | 25.22% |

| 2050s | 2.187 × 106 | 1.260 × 104 | 1.634 × 106 | 5.528 × 105 | 0.11 | 0.64% | 28.07% | |

| 2070s | 2.096 × 106 | 4.620 × 104 | 1.613 × 106 | 4.801 × 105 | 0.06 | 2.35% | 24.38% | |

| SSP5-8.5 | 2030s | 2.144 × 106 | 1.080 × 104 | 1.636 × 106 | 5.057 × 105 | 8.90% | 0.55% | 25.68% |

| 2050s | 2.073 × 106 | 5.090 × 104 | 1.595 × 106 | 4.740 × 105 | 5.26% | 2.58% | 24.07% | |

| 2070s | 1.806 × 106 | 2.446 × 105 | 1.416 × 106 | 3.839 × 105 | −8.28% | 12.42% | 19.49% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, C.-F.; Liu, Q.-Z.; Ma, X.-Y.; Liu, J.; He, F.-L. Predicting Current and Future Potential Distributions of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in China Based on the MaxEnt Model. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112546

Song C-F, Liu Q-Z, Ma X-Y, Liu J, He F-L. Predicting Current and Future Potential Distributions of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in China Based on the MaxEnt Model. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112546

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Cheng-Fei, Qing-Zhao Liu, Xin-Yao Ma, Jiao Liu, and Fa-Lin He. 2025. "Predicting Current and Future Potential Distributions of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in China Based on the MaxEnt Model" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112546

APA StyleSong, C.-F., Liu, Q.-Z., Ma, X.-Y., Liu, J., & He, F.-L. (2025). Predicting Current and Future Potential Distributions of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in China Based on the MaxEnt Model. Agronomy, 15(11), 2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112546