Abstract

Sponge gourd belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family and Luffa genus. It is an economically valuable vegetable crop with medicinal properties. The fruit size of sponge gourd presents distinct diversity; however, the molecular insights of fruit size regulation remain uncharacterized. Therefore, two sponge gourd materials with distinct fruit sizes were selected for a comparative transcriptome analysis. A total of 1390 genes were detected as differentially expressed between long sponge gourd (LSG) and short sponge gourd (SSG) samples, with 885 downregulated and 505 upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the MAPK signaling pathway, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and plant hormone signal transduction were significantly enriched. The DEGs involved in the cell cycle and cell division, plant hormone metabolism, and MAPK signal transduction were crucial for sponge gourd fruit size regulation. Additionally, the transcription factor families of ERF, NAC, bHLH, MYB, WRKY, and MADS-box were associated with fruit size regulation. The qRT-PCR validation for selected DEGs were generally consistent with the RNA-Seq results. These results obtained the candidate genes and pathways associated with fruit size and lay the foundation for revealing the molecular mechanisms of fruit size regulation in sponge gourd.

1. Introduction

Sponge gourd (2n = 2x = 26), which belongs to the family Cucurbitaceae and genus Luffa, is an annual climbing herb originating from the subtropical and tropical regions of Asia [1]. The fruits of sponge gourd are edible and rich in nutrients, such as carbohydrates, protein, vitamin, crude fiber, and minerals [2]. Additionally, their extracts and isolated compounds have certain pharmacological effects (e.g., immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory) that are beneficial for human health [3,4].

Fruit size, which is determined by fruit length, diameter, or the length:diameter ratio, is an important quality and yield trait for vegetables. Several genes controlling fruit size have been well studied in tomato, including SUN, LC, FAS, and OVATE [5,6]. The LC and FAS genes are associated with flat shape and fruit locule formation, whereas SUN and OVATE have crucial effects on fruit elongation [7,8]. Progress has been made regarding the characterization of the molecular mechanism underlying fruit size in Cucurbitaceae crops. The CsACS2 gene, which encodes a truncated loss-of-function protein, is considered to be responsible for the development of cucumber elongated fruits [9]. The CsSUN, a homolog of tomato fruit shape gene SUN, was a candidate for FS1.2 underlying cucumber fruit size variation [10]. The SF1 (Short Fruit 1) of cucumber encodes a cucurbit-specific RING-type E3 ligase, which ubiquitinates and degrades both itself and ACS2 (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase 2) to control ethylene biosynthesis for a dose-dependent effect on fruit cell division and fruit elongation [11]. The CsFUL1A is a gain-of-function allele in long-fruited cucumber that acts as a transcriptional repressor of fruit elongation by repressing the expression of SUPERMAN and inhibiting the expression of auxin transporters PIN-FORMED1 (PIN1) and PIN7 [12]. In melon, a genome-wide association analysis identified eight fruit size-related signals overlapping selective sweep regions, with FL5.1 and FL5.2 newly detected [13].

The development and utility of ’omics’ have resulted in significant advances regarding fruit size in cucurbit crops. For example, a comparative transcriptome analysis of two pumpkin cultivars with extreme fruit size difference revealed candidate genes (e.g., MYB, bHLH, AUX/IAA, and AP2) associated with fruit morphology and size as well as genes involved in cell expansion and cell division [14]. Two bottle gourd accessions with distinct fruit size were analyzed using transcriptome sequencing technology, which identified the candidate genes related to cell wall metabolism, phytohormones, cell cycle, and cell division regulating the fruit size [15]. Additionally, the RNA-Seq technology has been applied to analyze the fruit development in cucumber [16], snake gourd [17], and melon [18,19].

Considerable diversity exists in the size and shape of sponge gourd fruits (e.g., long cudgel, short cudgel, long cylinder, short cylinder, oval, spindle, sickle, waist girdle, and snake); however, the molecular insights of fruit size regulation remain uncharacterized. In this study, two materials of sponge gourd with distinct fruit size were analyzed by RNA-Seq. The candidate genes and pathways associated with fruit size regulation were identified. The results of this study provide us with valuable information for future attempts at validating the genes and revealing their molecular mechanism of fruit size regulation in sponge gourd.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The materials of sponge gourd used in this study were long sponge gourd (LSG) and short sponge gourd (SSG) (Figure 1). Plants were grown at the Yangdu Research and Innovation Base, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, under normal field management. Three fruits in each material were collected 10 days post pollination from three different plants, and the middle part of fruits were sliced and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples from each fruit were considered as a biological replicate and three biological replicates per material were used for subsequent RNA-Seq analysis.

Figure 1.

The two materials of sponge gourd used in this study.

2.2. RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and genomic DNA was removed using DNase I (Takara, Shiga, Japan). The RNA quality was evaluated using the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), whereas the RNA quantity was determined using the ND-2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). High-quality RNA samples (OD260/OD280 = 1.8–2.2, OD260/OD230 ≥ 2.0, RIN (RNA integrity number) ≥ 6.5, 28S:18S ≥ 1.0, and >10 μg) were used to construct the sequencing libraries.

2.3. Library Preparation and Transcriptome Sequencing

The Illumina Truse RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to prepare the transcriptome libraries from 1 μg total RNA. First, mRNA was isolated using oligo-(dT) beads and then fragmented in fragmentation buffer. The cDNA synthesis, end repair, A-base addition, and ligation of the Illumina-indexed adapters were performed as described by the manufacturer. Size-selected libraries comprising 200 to 300 bp cDNA target fragments were prepared by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis followed by a PCR amplification (15 cycles) using Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB, Beijing, China). The libraries were quantified using the TBS-380 fluorometer (Beijing Yuanpinghao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and then sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (2 × 150 bp paired-end reads) (BIOZERON Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.4. Read Quality Control Filtering and Mapping

The raw reads were trimmed to remove the reads containing adapter, reads containing ploy-N, and low-quality reads for quality control using Trimmomatic with parameters (SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:75) [20] (version 0.36). The retained clean reads were separately aligned to the sponge gourd reference genome [21] using the default parameters of the HISAT2 software [22] (version 2.1.0). The quality of the data was assessed using Qualimap 2 software [23] (version 2.2.1). The read count of each gene was determined using HTSeq [24] (version 0.11.1).

2.5. Identification and Functional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between samples, the expression level of each gene was calculated according to the fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) method [25]. The DEGs between LSG and SSG were detected according to the following criteria: |log2(fold-change)| > 1 and p-value < 0.05. The heat map of DEGs were analyzed using log2 (FPKM + le−2) at https://www.omicstudio.cn/index (accessed on 10 October 2021). Clustering analysis was performed for DEGs using the gplots package in R software (version 3.4.2; http://www.r-project.org) (accessed on 15 November 2020).

To functionally characterize the DEGs, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using Goatools [26] and KOBAS [27], respectively. The DEGs were assigned significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways on the basis of a Bonferroni-corrected p-value < 0.05.

2.6. Validation of RNA-Seq Results by Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analysis

To verify the expression of DEGs, total RNA was extracted from sponge gourd fruit samples and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The reaction mixture for the qRT-PCR analysis consisted of the following components: 10 μL 2 × TransStart Top Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech), 2.0 μL diluted cDNA, 0.4 μL 50 × Passive Reference Dye I, 0.4 µL each primer (10 µM), and 6.8 μL ddH2O. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed in 96-well optical reaction plates and the StepOne Real-Time PCR System (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). The PCR program was as follows: 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 55 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method [28]. The UBQ was used as reference gene. Details regarding the qRT-PCR primers are listed in Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the RNA-Seq Results

A total of 358,401,220 raw reads (53.76 Gb data) were obtained from all six samples using the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Table 1). After a quality control using Trimmomatic, 349,867,096 clean reads were retained, with the Q30 percentage exceeding 88.16% and the GC content ranging from 46.55% to 47.23% (Table 1). The clean reads in each sample were mapped to the sponge gourd reference genome using HISAT2, with the mapping rates ranged from 92.96% to 95.45% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the sequencing data.

3.2. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

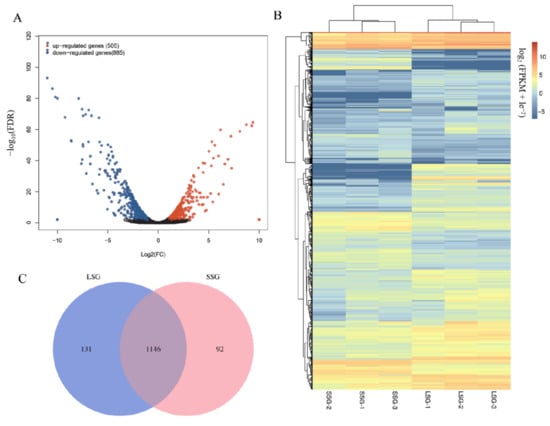

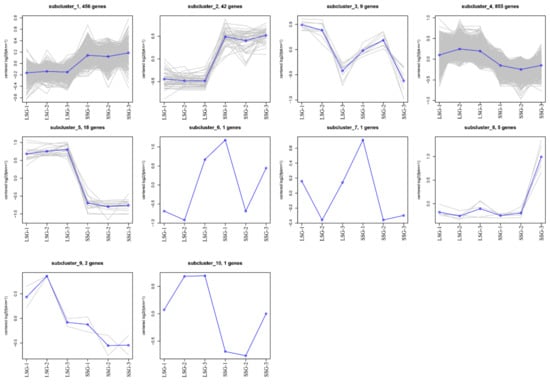

A total of 1390 genes were differentially expressed between LSG and SSG. Of these DEGs, 885 and 505 were respectively downregulated and upregulated in SSG compared with LSG (Table S2, Figure 2A,B). A Venn diagram analysis revealed 1146 DEGs commonly expressed in LSG and SSG. Moreover, 131 DEGs showed specific expression in LSG and 92 DEGs showed specific expression in SSG (Figure 2C). The DEGs were classified into 10 subclusters, with subcluster 4 (855 DEGs) and subcluster 1 (456 DEGs) the largest (Figure 3). The DEGs in subclusters 1 and 2 were upregulated in SSG for all libraries compared with LSG. However, the genes in subclusters 4 (855 DEGs), 5 (18 DEGs), and 9 (2 DEGs) had similar downregulated expression patterns in SSG compared with LSG for all libraries.

Figure 2.

Analysis of DEGs between LSG and SSG. (A) Volcano map representing the number of DEGs between LSG and SSG. (B) Heat map of DEGs between LSG and SSG; the heat map of DEGs was analyzed using log2 (FPKM + le−2) at https://www.omicstudio.cn/index (accessed on 10 October 2021). (C) Venn diagram of DEGs commonly or specifically expressed in LSG and SSG.

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis of the DEGs between LSG and SSG.

3.3. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses of DEGs

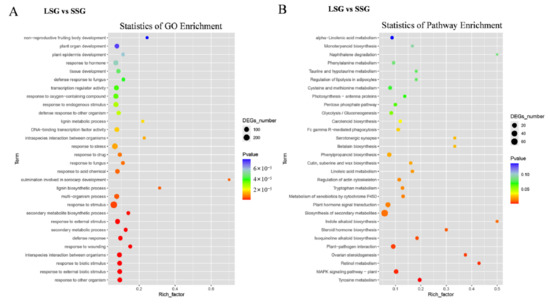

To functionally characterize the DEGs, a GO enrichment analysis was performed, which identified 247 GO terms that were significantly enriched among the DEGs. More specifically, 210, 28, and 9 enriched GO terms were from the categories of biological process, molecular function, and cellular component, respectively. In the biological process category, the enriched GO terms included response to other organism (GO:0051707), response to external biotic stimulus (GO:0043207), response to biotic stimulus (GO:0009607), interspecies interaction between organisms (GO:0044419), and response to wounding (GO:0009611). In the molecular function category, the enriched GO terms included DNA-binding transcription factor activity (GO:0003700), transcription regulator activity (GO:0140110), and oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors (GO:0016709). In the cellular component category, the enriched GO terms included actin cortical patch (GO:0030479), endocytic patch (GO:0061645), casparian strip (GO:0048226), and Arp2/3 protein complex (GO:0005885) (Figure 4A and Table S3).

Figure 4.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs between LSG and SSG. (A) GO enrichment analysis of DEGs; (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs.

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs identified 20 significantly enriched pathways. The top 10 enriched pathways were tyrosine metabolism (ko00350), MAPK signaling pathway-plant (ko04016), retinol metabolism (ko00830), ovarian steroidogenesis (ko04913), plant–pathogen interaction (ko04626), isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis (ko00950), steroid hormone biosynthesis (ko00140), indole alkaloid biosynthesis (ko00901), biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (ko01110), and plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) (Figure 4B and Table S4).

3.4. DEGs Related to Sponge Gourd Fruit Size Regulation

3.4.1. Transcription Factors (TFs) Related to Sponge Gourd Fruit Size Regulation

In this study, 75 transcription factors (TFs) genes were differentially expressed between SSG and LSG, with 56 and 19 respectively downregulated and upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. The six most represented TF families were ERF, bHLH, MYB, NAC, WRKY, and MADS-box, which included 18 ERF genes (17 downregulated and 1 upregulated), 9 bHLH genes (8 downregulated and 1 upregulated), 9 MYB genes (7 downregulated and 2 upregulated), 7 NAC genes (3 downregulated and 4 upregulated), 7 WRKY genes (all downregulated), and 6 MADS-box genes (5 downregulated and 1 upregulated) (Table 2). The expression levels for most TF genes were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG.

Table 2.

DEGs encoding transcription factors.

3.4.2. DEGs Involved in the Cell Cycle and Cell Expansion

A total of 15 DEGs related to the cell cycle and cell expansion were identified (Table 3), of which four DEGs (Maker00030282, Maker00038088, Maker00039350, and Maker00039481) encoding expansin (EXP) were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Five DEGs (Maker00006055, Maker00006010, Maker00006013, Maker00019798, and Maker00019916) encoding cyclin-dependent kinase were also downregulated in SSG compared with LSG, whereas Maker00013235, encoding cyclin, was upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Additionally, five DEGs (Maker00007464, Maker00023770, Maker00029744, Maker00029948, and Maker00038114) encoding xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes associated with the cell cycle and cell expansion.

3.4.3. DEGs Associated with Plant Hormone Metabolism

In this study, 22 DEGs related to plant hormone metabolism were identified (Table 4), among which six genes (Maker00000589, Maker00001150, Maker00014019, Maker00014874, Maker00015281, and Maker00023875) were encoding auxin-responsive protein. With the exception of Maker00023875, the remaining five auxin-responsive protein encoding genes were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Moreover, the expression levels of Maker00033389 (IAA-amino acid hydrolase), Maker00039293 (auxin transporter-like protein), and Maker00021979 (auxin-binding protein) were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG.

Table 4.

Differentially expressed genes associated with plant hormone metabolism.

Four DEGs were involved in abscisic acid (ABA) metabolism, of which three DEGs (Maker00039228 and Maker00016867 encoding abscisic acid receptor; Maker00013728 encoding abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase) were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. In contrast, the expression level of Maker00017853 (abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase) was upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Three DEGs (Maker00012983, Maker00013515, and Maker00013263 encoding salicylic acid-binding protein) and two DEGs (Maker00007121 encoding gibberellin-regulated protein and Maker00004222 encoding gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase), involved in salicylic acid and gibberellin metabolism, respectively, were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Two DEGs were involved in ethylene metabolism, with Maker00029913 (ethylene synthase) and Maker00016907 (protein reversion-to-ethylene sensitivity 1) respectively downregulated and upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Additionally, Maker00007027 (cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase) and Maker00031370 (jasmonic acid-amido synthetase), which were involved in cytokinin and jasmonic acid metabolism, respectively, were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. These results showed that most of the DEGs involved in plant hormone metabolism were repressed in SSG compared with LSG.

3.4.4. DEGs Involved in MAPK Signaling Pathway

Fourteen DEGs were revealed to affect the MAPK signaling pathway (ko04016) (Table 5), of which the expression levels of the following 11 DEGs were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG: Maker00004003 (hypothetical protein), Maker00011711 and Maker00012272 (mitogen-activated protein kinase), Maker00016867 (abscisic acid receptor), Maker00009036 (STS14 protein-like), Maker00029408 (pathogenesis-related protein), Maker00029913 (ethylene synthase), Maker00023340 (ethylene-responsive transcription factor), Maker00005830 and Maker00031399 (WRKY transcription factor), and Maker00021373 (MYC2-like transcription factor). In contrast, Maker00020996 (MYC2-like transcription factor), Maker00016907 (protein reversion-to-ethylene sensitivity 1), and Maker00019397 (endochitinase 2-like) were more highly expressed in SSG than in LSG.

Table 5.

DEGs involved in MAPK signaling pathway.

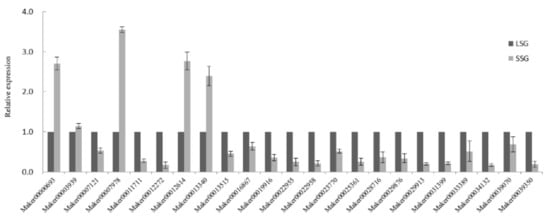

3.5. Validation of Fruit Size-Related DEGs by qRT-PCR Analysis

A total of 23 DEGs were selected for qRT-PCR validation (Figure 5). Five of the DEGs, namely, Maker00000693 (HVA22-like protein), Maker00003939 (beta-ureidopropionase), Maker00007978 (glutamate receptor), Maker00012614 (divaricata-like), and Maker00013340 (hypothetical protein Csa_018195), were expressed at higher levels in LSG than in SSG. The following 18 DEGs were expressed at lower levels in LSG than in SSG: Maker00022955 (ERF105-like), Maker00022958 (ERF106-like), Maker00029876 (NAC protein 55), Maker00034132 (bHLH30-like), Maker00039070 (MYB20-like), Maker00025361 (MYB1-like), Maker00031399 (WRKY 22-like), Maker00028716 (WRKY 34), Maker00039350 (expansin A9), Maker00023770 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 9-like), Maker00019916 (cyclin-dependent kinase C-2-like), Maker00033389 (IAA-amino acid hydrolase ILR1-like 3), Maker00007121 (gibberellin-regulated protein 1-like), Maker00016867 (abscisic acid receptor PYL2), Maker00013515 (salicylic acid-binding protein 2), Maker00011711 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 18-like), Maker00029913(ethylene synthase), and Maker00012272 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 17-like). The qRT-PCR data were generally consistent with the RNA-Seq results.

Figure 5.

qRT-PCR analysis of DEGs related to sponge gourd fruit size.

4. Discussion

Fruit size is one of the important agronomic traits affecting the quality and commercial value of horticultural crops. In recent years, RNA-Seq analyses have been applied to identify the crucial genes associated with fruit size in several cucurbit vegetables [17,18,19]. However, there has been relatively little research on sponge gourd fruit size regulation. In this study, two sponge gourd materials with distinct fruit size underwent an RNA-Seq analysis, and the candidate genes and pathways related to sponge gourd fruit size regulation were identified.

4.1. Regulatory Roles of TFs Involved in Sponge Gourd Fruit Size

Transcription factors, which are proteins containing at least one specific DNA-binding domain, regulate the expression of target genes and play important roles in plant growth and development [29]. In this study, a total of 75 genes from multiple TF families (e.g., ERF, NAC, bHLH, MYB, WRKY, and MADS-box) were differentially expressed between SSG and LSG (Table 2).

The ERF TFs are associated with plant hormone signaling, mediating plant growth, and development as well as secondary metabolism [29]. ERF TFs are responsive to ethylene signals and contribute to the feedback regulation of ethylene synthesis in plant tissues [30]. In plum, seven ERF cDNAs were cloned and revealed to be differentially expressed in various flower and fruit developmental stages [31]. In tomato, 85 ERF genes have been identified, of which 57 genes influence fruit development [32]. Additionally, the tomato ENO gene, which encodes an ERF, regulates fruit size through the floral meristem development network; a mutation in this gene results in the production of large multi-compartment fruits [33]. In the present study, 18 ERF-encoding DEGs were identified, with all but one more highly expressed in LSG than in SSG, indicating that ERF may promote longer fruit formation in sponge gourd.

The NAC proteins form one of the largest TF families in plants. The C-terminal of these TFs contains a transcriptional regulatory region, whereas the N-terminal includes a conserved DNA-binding domain, both of which observe the activity of protein binding [34,35]. In tomato, NAC proteins regulate fruit ripening through the ethylene and ABA pathways [36]. In strawberry, six NAC TFs reportedly contribute to secondary cell wall and vascular development to modulate fruit development and ripening [37]. A recent genome-wide gene expression analysis and qRT-PCR analysis indicated that NAC expression is positively correlated with kiwifruit development [38]. In this study, four NAC genes (Maker00000545, Maker00016510, Maker00017754, and Maker00039552) were upregulated in SSG compared with LSG, whereas the opposite expression pattern was detected for three other NAC genes (Maker00008337, Maker00029876 and Maker00037829). Accordingly, NAC TFs may have diverse functions related to sponge gourd fruit development.

The basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) contains a highly conserved bHLH domain with two distinct functional segments (i.e., the HLH region and the basic region) [39]. The bHLH family influences plant growth and development by regulating jasmonic acid responses, modulating light-regulated processes, and mediating cell cycle activities [40,41,42]. In Arabidopsis and rice, brassinosteroids regulate the conserved mechanism underlying plant development through HLH/bHLH [43]. In this study, eight bHLH genes (Maker00002860, Maker00003086, Maker00008080, Maker00008913, Maker00008926, Maker00024818, Maker00031926, and Maker00034132) were downregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Only one bHLH gene (Maker00012304) was upregulated in SSG compared with LSG. Therefore, bHLH might have positive effects on longer fruit formation in sponge gourd.

The MYB family, which forms one of the TF superfamilies, contains a MYB domain at its N-terminus [44]. The MYB family regulates the formation of the secondary cell wall by promoting/inhibiting the biosynthesis of xylan, cellulose, and lignin [45,46]. In Arabidopsis, the MYB-like DRMY1 can regulate cell expansion by directly affecting the cell wall structure and cytoplasmic expansion [47]. Moreover, MYB46 was reported serving as a critical regulator for the biosynthesis of all three major secondary cell wall components (hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin) [48]. In this study, the following seven MYB genes were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG: Maker00025361 (MYB1-like), Maker00039070 (MYB20-like), Maker00038509 (MYB46-like), Maker00014658 (MYB83-like), Maker00036073 (MYB86-like), Maker00029958 (MYB-related protein 308-like), and Maker00023477 (MYB103-like protein). Hence, MYB may promote longer fruit formation by regulating secondary cell wall structural changes and cytoplasmic expansion in sponge gourd.

The WRKY family contains highly conserved domains and is involved in the regulation of various physiological processes in plants [49]. In Arabidopsis, WRKY46/54/70 coordinately function with the brassinosteroid-regulated BES1 to promote the brassinosteroid signaling and affect plant growth [50]. In watermelon, ClWRKY is involved in the growth and development of different tissues, and its diverse motifs and conserved or variable WRKY domains suggest it may play a variety of regulatory roles [51]. Our results indicated that seven genes encoding WRKY were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG. Thus, WRKY may positively regulate longer fruit formation in sponge gourd.

The MADS-box family participates in many plant developmental processes, especially those related to fruit development and maturation [52]. In Arabidopsis, GORDITA encodes an MADS-box that can affect fruit size by regulating fruit cell expansion [53]. The MADS-box encoded by CsFUL1A can bind to the CsWUS promoter, thereby modulating the cucumber fruit shape, size, and internal quality [54]. In apple, MdPI encodes an MADS-box that affects the apple floral organ, and ectopic expression of this gene can alter apple fruit tissue growth and shape [55]. In this study, five MADS-box genes (Maker00034417, Maker00034410, Maker00014108, Maker00013693, and Maker00004005) were more highly expressed in LSG than in SSG, whereas only one MADS-box gene (Maker00002571) was more highly expressed in SSG than in LSG. It was predicted that MADS-box genes might be positive regulators of longer fruit formation in sponge gourd.

4.2. Cell Expansion and Cell Cycle Regulating Sponge Gourd Fruit Size

Fruit development is associated with cell expansion and the cell cycle. Cell expansion, which determines cell size, is regulated by EXPs, XTHs, and other important factors [56]. The EXPs induce cell wall extension and relaxation, leading to cell enlargement [57]. In watermelon, EXP-encoding genes (ClEXP genes) were differentially expressed in the fruit rind, fruit flesh, and seeds during various developmental stages, and their promoter regions contained many development-related elements [58]. Overexpression of cucumber EXP genes in maize grains revealed the synergistic effects of EXPs and cellulases during the deconstruction of complex cell wall substrates [59]. In addition to their cell expansion effects, XTHs also function as cell wall-loosening enzymes [60]. The Brassica campestris BcXTH1 gene regulated cell expansion and was highly expressed in the epidermal cell layer [61]. Four DEGs encoding EXPs and five DEGs encoding XTHs were identified in this study. The expression levels of all these DEGs were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG, which implied that EXPs and XTHs positively regulated longer fruit formation in sponge gourd.

The cell cycle, which regulates cell division, determines the number of cells and is controlled by cyclins and cyclin-dependent protein kinases (CDKs) [62]. There are seven classes of cyclins (A, B, C, D, H, P, and T) in plants [63]. In terms of their effects on the cell cycle, cyclins in classes A, B, and D have been the most thoroughly studied. During the G2/M transition, the A-type and specific B-type CDKs can drive cell division after they bind to A-, B-, and D-type cyclins. Additionally, the plant D-type cyclins act as sensors of the G0-to-G1 phase transition [63]. Furthermore, DNA replication and mitosis are associated with CDK activities that control phosphorylation of the serine/threonine residues in specific substrates in eukaryotes [63,64]. In the present study, four CDK-encoding DEGs were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG, whereas one DEG encoding cyclin was downregulated in LSG compared with SSG. These results imply that CDKs are positive regulators of longer fruit formation in sponge gourd. However, the functions and effects of CDK and cyclin would need to be more precisely characterized in future investigations.

4.3. Plant Hormones Regulating Sponge Gourd Fruit Size

Different plant hormones can form a complex network regulating various aspects of fruit development [65]. In strawberry, auxin (IAA) and ABA controlled the initial development and final ripening of fruits and the expression of underlying genes, and the IAA:ABA ratio was the main regulatory signal for fruit development [66]. In tomato, Sl-ERF.B3 (ethylene response factor) integrates ethylene and auxin signals by regulating the expression of Sl-IAA27 [67]. The interactions among gibberellins, salicylic acid, and ABA affect plant germination. Additionally, gibberellins modulate the salicylic acid pathway and influence salicylic acid biosynthesis [68]. Moreover, cytokinins interacted with TFs and phosphorylation cascades to control the expression of cytokinin target genes [69]. As a mobile signal in plants, gibberellins are involved in many developmental and adaptive growth processes [70]. Jasmonic acid is a lipid-derived stress hormone that regulates plant developmental processes (e.g., maternal control of embryo development in tomato) [71]. In this study, 21 DEGs associated with the metabolism of salicylic acid, ethylene, gibberellin, ABA, auxin, cytokinin, and jasmonic acid were identified. Most of these DEGs were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG. Therefore, it was speculated that the DEGs involved in plant hormone metabolism promoted longer fruit size formation in sponge gourd.

4.4. MAPK Signaling Pathway Regulating Sponge Gourd Fruit Size

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are ubiquitous and highly conserved signaling modules in eukaryotes. They are involved in embryogenesis, morphogenesis, senescence, abscission, and other aspects of plant growth and development [72]. The MAPK pathway consists of three major kinases: MAPK kinase kinase, MAPK kinase, and MAPK, which activate and phosphorylate downstream targets in a stepwise manner [73]. In addition to being activated during specific stages to regulate the cell cycle, MAPK cascades are also crucial for basic physiological activities, including responses to hormones and abiotic stress signals as well as defense mechanisms [74]. In Arabidopsis, MAP3K17 and MAP3K18 activated the MAP2K (i.e., MKK3), thereby activating the C-clade MAPKs (MPK1, MPK2, MPK7, and MPK14) in response to ABA [75]. The MAPK pathway is also associated with ethylene signal transduction, with the MKK9–MPK3/MPK6 module functioning downstream of ethylene receptor [76,77]. In Arabidopsis, a bHLH transcription factor (MYC2/ZBF1) negatively regulated gene expression in response to blue and far-red light, and the MKK3–MPK6–MYC2 module affected seedling development [78]. In this study, 14 DEGs involved in the MAPK pathway were revealed to encode various proteins (e.g., MAPK, abscisic acid receptor, ethylene synthase, WRKY, MYC2, and ERF). The expression levels of most DEGs were upregulated in LSG compared with SSG, suggesting that the MAPK signaling pathway is important for longer fruit size formation in sponge gourd.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the RNA-Seq analysis was performed using two sponge gourd materials with distinct fruit sizes to reveal the crucial genes and pathways associated with fruit size regulation. A total of 1390 DEGs were identified (885 downregulated and 505 upregulated in SSG, relative to the expression levels in LSG). A functional analysis of these DEGs indicated they are mainly involved in the cell cycle and cell division, plant hormone metabolism, and the MAPK signal transduction pathway. Additionally, TFs belonging to the ERF, NAC, bHLH, MYB, WRKY, and MADS-box families play important roles in fruit size regulation. The findings of this study obtained the genes and pathways regulating fruit size in sponge gourd, which lay the foundation for revealing the molecular mechanisms conferring fruit size in cucurbit crops.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy12081810/s1, Table S1: The primers of qRT-PCR analysis for selected DEGs. Table S2: DEGs between LSG and SSG. Table S3: GO enrichment analysis for DEGs between LSG and SSG. Table S4: KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for DEGs between LSG and SSG.

Author Contributions

S.Q. carried out the experiment, data analysis, interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. Y.S. conceived and designed the study, supervised the work and revised the manuscript. Y.X. carried out the experiment. Q.H., W.D., S.H. and X.Q. give suggestions to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Major Agricultural Science and Technology Projects of New Varieties Breeding (2021C02065), the Third National Census and Collection of Crop Germplasm Resources (111821301354052030), and Zhejiang Provincial Accurate Phenotypic Identification of Cucurbits and Vegetables Germplasm Resources.

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data from this article were deposited at the sequence read archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the accession number of SRR13618022, SRR13618023 and SRR13618024 for SSG, and SRR13618025, SRR13618026 and SRR13618027 for LSG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tyagi, R.; Sharma, V.; Sureja, A.K.; Das Munshi, A.; Arya, L.; Saha, D.; Verma, M. Genetic diversity and population structure detection in sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica) using ISSR, SCoT and morphological markers. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Moreno, L.; González, V.M.; Benjak, A.; Martí, M.C.; Puigdomènech, P.; Aranda, M.A.; Garcia-Mas, J. Determination of the melon chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences reveals that the largest reported mitochondrial genome in plants contains a significant amount of DNA having a nuclear origin. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendge, P.N.; Belemkar, S. Therapeutic potential of Luffa acutangula: A review on its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and roxicological aspects. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlel, T.B.; Belhadj, F.; Gül, F.; Altun, M.; Yağlıoğlu, A.Ş.; Demirtaş, I.; Marzouki, M.N. Variations in the bioactive compounds composition and biological activities of loofah (Luffa cylindrica) fruits in relation to maturation stages. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, G.R.; Muños, S.; Anderson, C.; Sim, S.C.; Michel, A.; Causse, M.; Gardener, B.B.; Francis, D.; van der Knaap, E. Distribution of SUN, OVATE, LC, and FAS in the tomato germplasm and the relationship to fruit shape diversity. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monforte, A.J.; Diaz, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.; van der Knaap, E. The genetic basis of fruit morphology in horticultural crops: Lessons from tomato and melon. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4625–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.H.; Jang, J.C.; Huang, Z.; van der Knaap, E. Tomato locule number and fruit size controlled by natural alleles of lc and fas. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Clevenger, J.P.; Illa-Berenguer, E.; Meulia, T.; van der Knaap, E.; Sun, L. A comparison of sun, ovate, fs8.1 and auxin application on tomato fruit shape and gene expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tao, Q.; Niu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Gong, Z.; Weng, Y.; Li, Z. A novel allele of monoecious (m) locus is responsible for elongated fruit shape and perfect flowers in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liang, X.; Gao, M.; Liu, H.; Meng, H.; Weng, Y.; Cheng, Z. Round fruit shape in WI7239 cucumber is controlled by two interacting quantitative trait loci with one putatively encoding a tomato SUN homolog. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Huang, S.; Yang, X. Genetic regulation of ethylene dosage for cucumber fruit elongation. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Jiang, L.; Che, G.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Ding, L.; Yan, S.; et al. A functional allele of CsFUL1 regulates fruit length through repressing CsSUP and inhibiting auxin transport in cucumber. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, P.; Zhu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Weng, Y.; Gao, M.; Luan, F. Resequencing of 297 melon accessions reveals the genomic history of improvement and loci related to fruit traits in melon. Plant Biotechnol. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, A.; Ganopoulos, I.; Psomopoulos, F.; Manioudaki, M.; Moysiadis, T.; Kapazoglou, A.; Osathanunkul, M.; Michailidou, S.; Kalivas, A.; Tsaftaris, A.; et al. De novo comparative transcriptome analysis of genes involved in fruit morphology of pumpkin cultivars with extreme size difference and development of EST-SSR markers. Gene 2017, 622, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tan, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, S.; Chen, X. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of two bottle gourd accessions differing in fruit size. Genes 2020, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Carr, K.M.; Grumet, R. Transcriptome analyses of early cucumber fruit growth identifies distinct gene modules associated with phases of development. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, Q.; Mu, J.; Fu, A.; Wen, C.; Zhao, X.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.; et al. The genome and transcriptome analysis of snake gourd provide insights into its evolution and fruit development and ripening. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Yi, H.; Zhai, W.; Wang, G.; Fu, Q. Transcriptome profiling of Cucumis melo fruit development and ripening. Hortic. Res. 2016, 3, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Huang, L. iTRAQ and RNA-Seq analyses revealed the effects of grafting on fruit development and ripening of oriental melon (Cucumis melo L. var. makuwa). Gene 2021, 766, 145142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ming, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Sun, K.; et al. Long-read sequencing and de novo assembly of the Luffa cylindrica (L.) Roem. genome. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Conesa, A.; García-Alcalde, F. Qualimap 2: Advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Prtoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, D.V.; Zhang, L.; Pedersen, B.S.; Ramírez, F.; Warwick Vesztrocy, A.; Naldi, A.; Mungall, C.J.; Yunes, J.M.; Botvinnik, O.; Weigel, M.; et al. GOATOOLS: A Python library for Gene Ontology analyses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Luo, J.; Wei, L. KOBAS server: A web-based platform for automated annotation and pathway identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W720–W724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Method 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Hou, X.L.; Xing, G.M.; Liu, J.X.; Duan, A.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Li, M.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Xiong, A.S. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licausi, F.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Perata, P. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: Mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, I.; Sherif, S.; Mila, I.; Bouzayen, M.; Jayasankar, S. Molecular characterization of seven genes encoding ethylene-responsive transcriptional factors during plum fruit development and ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kumar, R.; Solanke, A.; Sharma, R.; Tyagi, A.; Sharma, A. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript profiling of erf family genes during development and abiotic stress treatments in tomato. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2010, 284, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuste-Lisbona, F.J.; Fernández-Lozano, A.; Pineda, B.; Bretones, S.; Ortíz-Atienza, A.; García-Sogo, B.; Müller, N.A.; Angosto, T.; Capel, J.; Moreno, V.; et al. ENO regulates tomato fruit size through the floral meristem development network. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8187–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooka, H.; Satoh, K.; Doi, K.; Nagata, T.; Otomo, Y.; Murakami, K.; Matsubara, K.; Osato, N.; Kawai, J.; Carninci, P.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003, 10, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.N.; Ernst, H.A.; Leggio, L.L.; Skriver, K. NAC transcription factors: Structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends. Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, C.E.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chai, L.; Xue, Z. The interplay between ABA/ethylene and NAC TFs in tomato fruit ripening: A review. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 106, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, E.; Martínez-Rivas, F.J.; Blanco-Portales, R.; Molina-Hidalgo, F.J.; Ric-Varas, P.; Matas-Arroyo, A.J.; Caballero, J.L.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Franco, A. Genome-wide analysis of the NAC transcription factor family and their expression during the development and ripening of the Fragaria × ananassa fruits. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, H.; Chen, L.; Liao, G.; He, Y.; Huang, C.; Xu, X. Genome-wide identification and comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes involved in fruit development in kiwifruit (Actinidia). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Huang, Z.N.; Duan, W.K.; Ren, J.; Liu, T.K.; Li, Y.; Hou, X.L. Genome-wide analysis of the bHLH transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, J.; Mertens, J.; Goossens, A. Role and functioning of bHLH transcription factors in jasmonate signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Oh, E.; Choi, G.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Z.Y. Interactions between HLH and bHLH factors modulate light-regulated plant development. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yang, S.; Kang, X.; Lei, W.; Qiao, K.; Zhang, D.; Lin, H. The bHLH transcription factor gene AtUPB1 regulates growth by mediating cell cycle progression in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 518, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Bai, M.Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3767–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.F.; Yang, W.J.; Wu, Y.M.; Huang, Y.B.; Tang, Y.X. Biochemical and molecular characterization of plant MYB transcription factor family. Biochemistry 2009, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Li, H.; Lu, H. MYB transcription factors and its regulation in secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis during xylem development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Ko, J.H.; Kang, H.; Han, K.H. Identification of direct targets of transcription factor MYB46 provides insights into the transcriptional regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 85, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Peng, M.; Li, Z.; Yuan, N.; Hu, Q.; Foster, C.E.; Saski, C.; Wu, G.; Sun, D.; Luo, H. DRMY1, a myb-like protein, regulates cell expansion and seed production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.H.; Jeon, H.W.; Kim, W.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, K.H. The MYB46/MYB83-mediated transcriptional regulatory programme is a gatekeeper of secondary wall biosynthesis. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nolan, T.M.; Ye, H.; Zhang, M.; Tong, H.; Xin, P.; Chu, J.; Chu, C.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y. Arabidopsis WRKY46, WRKY54, and WRKY70 transcription factors are involved in brassinosteroid-regulated plant growth and drought responses. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1425–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X. Identification and expression analyses of WRKY genes reveal their involvement in growth and abiotic stress response in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Guo, X.; Tian, S.; Chen, G. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box transcription factor family in solanum lycopersicum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Ambrose, B.A. Shaping up the fruit: Control of fruit size by an Arabidopsis B-sister MADS-box gene. Plant Signal Behav. 2010, 5, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Che, G.; Gu, R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Song, X.; Zi, H.; Cheng, Z.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; et al. Gene regulatory network controlling carpel number variation in cucumber. Development 2020, 147, dev184788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.L.; Xu, J.; Tomes, S.; Cui, W.; Luo, Z.; Deng, C.; Ireland, H.S.; Schaffer, R.J.; Gleave, A.P. Ectopic expression of the PISTILLATA homologous MdPI inhibits fruit tissue growth and changes fruit shape in apple. Plant Direct 2018, 2, e00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D. The plant cell cycle—15 years on. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J.; Li, L.C.; Cho, H.T.; Hoffmann-Benning, S.; Moore, R.C.; Blecker, D. The growing world of expansins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Li, D.; Fan, X.; Sun, Y.; Han, B.; Wang, X.; Xu, G. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the expansin gene family in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Devaiah, S.P.; Choi, S.E.; Bray, J.; Love, R.; Lane, J.; Drees, C.; Howard, J.H.; Hood, E.E. Over-expression of the cucumber expansin gene (Cs-EXPA1) in transgenic maize seed for cellulose deconstruction. Transgenic Res. 2016, 25, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, V.S.; Suslov, D.; Verbelen, J.P.; Vissenberg, K. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase activity loosens a plant cell wall. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.K.; Yum, H.; Kim, E.S.; Cho, H.; Gothandam, K.M.; Hyun, J.; Chung, Y.Y. BcXTH1, a Brassica campestris homologue of Arabidopsis XTH9, is associated with cell expansion. Planta 2006, 224, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jones, L.; McQueen-Mason, S. Expansins and cell growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, P.C.; Mews, M.; Moore, R. Cyclin/Cdk complexes: Their involvement in cell cycle progression and mitotic division. Protoplasma 2001, 216, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stals, H.; Casteels, P.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D. Regulation of cyclin-dependent kinases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 43, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Khurana, A.; Sharma, A.K. Role of plant hormones and their interplay in development and ripening of fleshy fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4561–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Puche, L.; Blanco-Portales, R.; Molina-Hidalgo, F.J.; Cumplido-Laso, G.; García-Caparrós, N.; Moyano-Cañete, E.; Caballero-Repullo, J.L.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Franco, A. Extensive transcriptomic studies on the roles played by abscisic acid and auxins in the development and ripening of strawberry fruits. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2016, 16, 671–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shin, J.H.; Mila, I.; Audran, C.; Zouine, M.; Pirrello, J.; Bouzayen, M. The tomato Ethylene Response Factor Sl-ERF.B3 integrates ethylene and auxin signaling via direct regulation of Sl-Aux/IAA27. New Phytol. 2018, 219, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-San Vicente, M.; Plasencia, J. Salicylic acid beyond defence: Its role in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3321–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Zheng, H.X.; Zhang, X.S.; Sui, N. Cytokinins as central regulators during plant growth and stress response. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binenbaum, J.; Weinstain, R.; Shani, E. Gibberellin localization and transport in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, L.; Song, S. Jasmonate action in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in signaling plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.J.; Yang, W.X. Kinesins in MAPK cascade: How kinesin motors are involved in the MAPK pathway? Gene 2019, 684, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, G.; Asai, T.; Chiu, W.L.; Sheen, J. Plant mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2001, 4, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zelicourt, A.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. The role of MAPK modules and ABA during abiotic stress signaling. Trends. Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.D.; Sheen, J. MAPK signaling in plant hormone ethylene signal transduction. Plant Signal Behav. 2008, 3, 848–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Ethylene signaling: The MAPK module has finally landed. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.; Raghuram, B.; Sinha, A.K.; Chattopadhyay, S. A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade module, MKK3-MPK6 and MYC2, is involved in blue light-mediated seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3343–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).