Abstract

This in vitro study investigated the fracture resistance of three ceramic-reinforced polymer (CRP) crowns—Cerasmart® 270 (CE; milled), VarseoSmile Crown Plus® (VS; 3D-printed) and the newly developed Hassawat-01 (HS; 3D-printed)—luted with cements of different elastic moduli. The principal hypothesis was that neither the CRP type nor the modulus of cement would significantly affect fracture resistance. Ninety-nine mandibular first molar resin dies were restored with 1 mm thick CE, VS, or HS crowns (n = 33 each) and luted with Maxcem Elite®, RelyX Unicem®, or Ketac Cem® (n = 11 per subgroup). Occlusal cement morphology was evaluated using Micro-CT. Fracture resistance was measured using a universal testing machine. Crowns luted with Maxcem or RelyX withstood forces >2000 N without visible failure. Ketac-luted crowns showed reduced fracture resistance. CE-Ketac fractured in 4 of 11 specimens. VS-Ketac exhibited cracks or complete fractures (1795.2 ± 156.7 N), whereas HS-Ketac showed only superficial cracking (1732.6 ± 127.3 N). CRP crowns luted with lower-modulus resin cements demonstrated superior fracture resistance compared with those luted with glass-ionomer. VS exhibited both cracking and occasional complete fractures, whereas HS exhibited only surface cracking. All materials withstood loads greater than typical masticatory forces, supporting HS as a promising alternative within the CRP.

1. Introduction

Ceramic-reinforced polymers (CRPs) have become an important class of hybrid restorative materials, combining the toughness, reparability, and photopolymerization advantages of cross-linked polymers with the strength, stiffness, and esthetics provided by inorganic ceramic fillers [1,2,3,4,5,6]. CRPs are typically classified into polymer-infiltrated ceramic networks (PICNs) and resin nanoceramics (RNCs). PICNs contain a porous silanized ceramic scaffold—usually leucite- or zirconia-based—into which a polymer infiltrates to form an interpenetrating network, whereas RNCs incorporate nanoscale silica or barium-glass (BG) fillers within a highly cross-linked resin matrix [4,5,7]. Among commercial RNCs, Cerasmart® 270 (CE), which contains 71 wt.% ceramic fillers (20 nm silica and 300 nm barium glass), has shown favorable mechanical behavior and clinical performance [5].

Although CAD/CAM milling of pre-polymerized CRP blocks provides consistent material quality, it is inherently wasteful and can introduce microcracks during machining. Additive manufacturing, particularly digital light processing (DLP), has therefore gained attention for its efficiency, greater control over polymerization, and potential for improved filler distribution [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Among DLP-printable CRP materials, VarseoSmile Crown Plus® (VS) incorporates 30–50 wt.% silanized ceramic fillers and is approved for single-unit restorations. However, its relatively low filler content raises concerns about long-term stability and strength [14,15,16]. To address these limitations, a novel DLP-printable CRP, Hassawat-01 (HS), was developed using alumina as the reinforcing phase. Alumina was selected because of its high hardness, wear and corrosion resistance, color stability, and established biocompatibility in polymer-ceramic medical composites [13,17,18]. Urethane acrylate (UA) was chosen as the organic matrix because of its favorable cross-link density, toughness, photoreactivity, and reduced polymerization shrinkage, characteristics that support DLP printing and load-bearing applications [19,20,21]. Previous studies indicate that incorporating nano- to microscale alumina into photocurable polymers can enhance flexural strength, modulus, hardness, and optical stability [8,9,13]. Based on these structure–property relationships, HS was formulated with 38.5 wt.% 0.7 µm alumina fillers and 61.5 wt.% UA-based resin to achieve a balance between mechanical reinforcement and printability.

Despite early concerns about their long-term mechanical reliability, several in vitro studies have shown that CRP materials can withstand clinically relevant occlusal forces [22,23,24,25]. Donmez and Okutan reported acceptable performance of CRP crowns, with mean fracture loads of 1274 ± 135 N [26]. Suksuphan et al. showed that VS crowns cemented with RelyX Unicem® had fracture resistance values of 1480 to 1747 N, whereas CE crowns exceeded 2000 N [27]. Zimmermann et al. reported fracture loads spanning 571 to 1580 N for CAD/CAM hybrid ceramics and RNCs, including CE [28]. Other studies reported similar findings, with CE crowns achieving fracture loads of 1000.9 to 1111.3 N, depending on occlusal thickness [23]. These values exceed typical adult bite forces of 315 to 806 N (men: 453 to 806 N; women: 315 to 567 N) [24,25], suggesting that CRPs, when properly luted, may be suitable for posterior restorations.

However, the mechanical performance of CRP crowns is not determined by material composition alone. The elastic modulus of the luting cement strongly influences stress distribution across the crown, cement, substrate complex, affecting both stress concentration and failure patterns [29,30]. Finite element analyses identify cement modulus as a critical factor governing intra-crown stresses, and they generally recommend intermediate-modulus or modulus-compatible cements for high-modulus ceramics [31,32,33]. These findings align with the cement-adaptation theory, which states that modulus-compatible cements transmit occlusal loads more effectively to the tooth and minimize residual stress within the crown [34]. Pairing IPS e.max CAD® with a higher-modulus resin cement (NX3®) reduced peak stress in cervical enamel, even though internal cement stress increased, which lowered the likelihood of adhesive failure [35]. Taken together, these findings support the use of intermediate-to-high modulus resin cements, with good adaptation and controlled film thickness, to optimize fracture resistance in ceramic restorations [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. However, these recommendations may not translate directly to low-modulus CRPs, whose elasticity can be five to ten times lower than that of lithium disilicate or zirconia, and for which experimental data remain limited.

Accordingly, the present study investigated the influence of luting cement modulus on the fracture resistance of crowns fabricated from three CRP systems. Those include CE, a milled and highly filled RNC; VS, a moderately filled DLP-printable CRP; and HS, a novel alumina-reinforced DLP-printable CRP with a UA matrix. Three cements with low to high elastic moduli, Maxcem Elite® (approx. 4 GPa), RelyX Unicem® (approx. 13 GPa), and Ketac Cem® (approx. 20 GPa), were used to evaluate how modulus compatibility affects load transfer and failure behavior. Micro-CT was also used as a qualitative tool to visualize internal cement morphology and support interpretation of interfacial integrity. Beyond the primary objective, the study also compared the mechanical performance of the newly developed HS material with established commercial CRPs. The null hypothesis stated that neither the type of CRP material, including HS relative to CE and VS, nor the modulus of the luting cement would significantly affect fracture resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Ninety-nine mandibular first molar CRP crowns were fabricated using CAD/CAM technology. Three materials were tested: a milled resin nanoceramic (Cerasmart® 270; CE) and two DLP-printed CRPs (VarseoSmile Crown Plus®; VS and the experimental alumina-reinforced Hassawat-01; HS) with 33 specimens per group. CE crowns were milled using a CARES M Series unit (Straumann, Basel, Switzerland). VS and HS crowns were fabricated with a DLP printer (Freeform Pro 2; ASIGA, Sydney, NSW, Australia) from CAD-generated STL files. Printed crowns were cleaned in 96% ethanol using an ultrasonic bath, air-dried, and post-cured according to manufacturer instructions [41]. Internal surfaces were air-abraded with 50 μm Al2O3 at 1.5 bar from a distance of 10 mm for 10 s, air-dried, and treated with a silane coupling agent (RelyX Ceramic Primer®; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) [14,42]. Each group was divided into three cementation subgroups (n = 11) using luting agents of differing elastic moduli: Maxcem Elite® (approx. 4 GPa), RelyX Unicem® (approx. 13 GPa), and Ketac Cem® (approx. 20 GPa), resulting in nine experimental conditions. Sample size was calculated using G*Power v3.1 (HHU Düsseldorf) with α = 0.05 and power = 0.80. An effect size derived from a previous study [27] confirmed that 11 specimens per subgroup were adequate to detect significant differences.

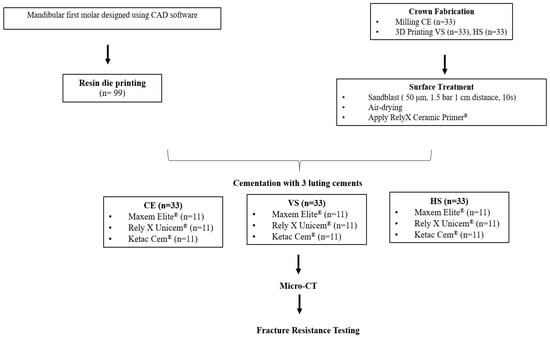

Crowns were bonded to standardized 3D-printed resin dies (Rigid 10K; Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA) and stored at 37 °C for 24 h to allow complete cement polymerization. Cement interfaces were evaluated by micro-computed tomography (SkyScan 1172; Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium), and fracture resistance was tested using a universal testing machine (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) under axial compression at 1 mm/min until failure [27]. The testing machine had a maximum force limit of 2000 N, so only specimens with measurable failure loads at or below this limit were included in the statistical analysis. Specimens exceeding 2000 N were classified as right-censored and excluded. Material compositions and the conceptual framework are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Details of the materials used in this research [27,33,42,43,44,45,46].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study design.

2.2. Virtual Design of Resin Die and CRP Crown Preparation

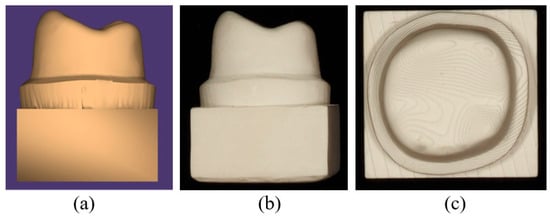

A resin-die STL file of a mandibular first molar was designed in Autodesk Fusion 360, version 2.0.16786 (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) according to standard full-crown preparation guidelines. Preparation parameters were described previously [27]. A corresponding molar crown with a 1 mm occlusal thickness was modeled in 3Shape Dental System (version 2020), with a 50 µm cement space between the crown intaglio and the die surface (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) STL file of resin die designed in Autodesk Fusion 360 CAD software; (b) distal view of the resin die; (c) occlusal view of the resin die.

2.3. Fabrication of CRP Crown Specimens and Cementation

A total of 33 CE crowns were milled using the CARES M Series system (Straumann, Switzerland) with 1.0, 1.4, and 1.8 mm burs, which were replaced after every 17 crowns. For the additively manufactured groups, 33 VS and 33 HS crowns were fabricated using a DLP-based 3D printer (Freeform Pro 2, ASIGA, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All crowns were designed as CAD models, exported as STL files, and processed using the manufacturer’s proprietary software. Printing was performed using the manufacturer’s recommended settings, including a 50 µm layer thickness, a 12.816 s exposure time, and a light intensity of 7.6 mW/cm2.

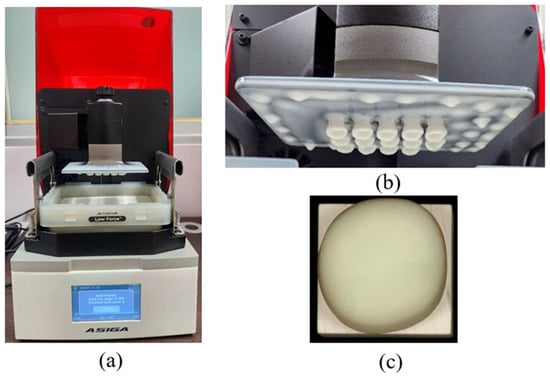

Following fabrication, the printed crowns underwent standardized post-processing. Support structures were removed using a cutting wheel or side cutters, and all surfaces were then airborne-particle abraded with 50 µm alumina powder at 1.5 bar for 10 s. All specimens were sequentially cleaned in 96% ethanol in an ultrasonic bath and air-dried. Post-curing was performed in a nitrogen atmosphere using a BEGO Otoflash device (BEGO, Bremen, Germany). equipped with two xenon stroboscopic lamps operating at 10 Hz and emitting light between 300 and 700 nm. Each printed crown underwent two post-curing cycles of 1500 flashes, followed by a 3 to 5 min cooling period until reaching room temperature [41]. To ensure methodological consistency, the experimental HS material was processed using the same equipment, post-curing protocol, and software workflow as the commercial VS material. This approach facilitates practical implementation by allowing HS to be fabricated under the same standard conditions used for clinically available DLP-printed CRP materials (Figure 3). All crowns, both milled and 3D-printed, were thermally conditioned in a heating cabinet (LEEC Ltd., Nottingham, UK) at 37 °C for 24 h before cementation.

Figure 3.

(a) The DLP-based Freeform Pro 3D printer (ASIGA; Anaheim Hills, USA). (b) The appearance of Hassawat-01 (HS) crowns after the printing process; (c) occlusal view of HS crown.

All crown internal surfaces were sandblasted with 50 µm alumina powder as described above. Each material group was divided into three subgroups and luted with Maxcem Elite®, RelyX Unicem®, or Ketac Cem®, following the respective manufacturers’ instructions. Crowns were seated on resin dies under a standardized 20 N static load using a digital force gauge (SF-500; Wenzhou Sanhe Measuring Instrument Co., Ltd., Wenzhou, China) mounted on a manual screw stand to ensure uniform pressure [27,47,48]. This load level is consistent with previous crown-cementation studies and was selected to minimize variability in cement film thickness and internal gap geometry that can occur when seating forces differ between specimens. Excess cement was removed before polymerization. For Maxcem Elite® and RelyX Unicem®, polymerization was performed using an LED curing unit (470 nm, 1000 mW/cm2; SmartLite Focus, Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA). Each specimen was light-cured for 40 s on all axial surfaces (mesial, distal, buccal, lingual) and then from the occlusal surface. For Ketac Cem®, crowns were left undisturbed for 3.5 min to allow self-setting. All specimens were stored at 37 °C for 24 h before micro-CT analysis.

2.4. Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) Analysis

Micro-CT imaging was performed to qualitatively evaluate internal cement morphology, with particular emphasis on voids or crack-like features in the occlusal region. After micro-CT acquisition, one representative specimen from the nine experimental groups was selected for descriptive comparison. All scans were obtained using a high-resolution micro-CT system (SkyScan 1172; Bruker, Belgium) with the following parameters: 67 kV, 41 μA, a 10 µm voxel size, and a 1 mm aluminum filter. Specimens were positioned perpendicular to the X-ray beam, and images were collected throughout a 360° rotation with a 0.2° rotation step. Projection images were reconstructed into cross-sectional slices using NRecon software (v1.6.9; Bruker) [27]. The reconstructed datasets were used exclusively to visualize cement distribution and internal structural morphology.

2.5. Fracture Resistance Test

Fracture testing was performed using a universal testing machine (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a 5 mm stainless steel ball positioned perpendicular to the central pit of each crown (Figure 4). A compressive load was applied at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min until either a visible crack or a complete fracture occurred, and loading was terminated at a maximum of 2000 N [27]. For each specimen, the maximum fracture load and the corresponding failure mode were recorded. An intact specimen was defined as one with no visible crack or structural discontinuity. A crack was defined as a visible line or fissure within the material without complete separation, and a fracture was defined as catastrophic failure in which the crown separated into two or more distinct fragments.

Figure 4.

Position of the CRP crown specimen in the setup for single-load fracture test.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

No failures occurred in CE, VS, or HS crowns luted with Maxcem Elite® or RelyX Unicem®, all of which withstood loads exceeding 2000 N. These specimens were treated as right-censored and excluded from statistical analysis. In the Ketac Cem® groups, four of eleven CE specimens exhibited fractures; however, all failure loads also exceeded 2000 N and were therefore also classified as right-censored. Both fracture and crack loads were recorded, and crack initiation was considered a valid failure value. Accordingly, only specimens with failure loads of 2000 N or less, whether cracked or fully fractured, were included in the statistical analysis. As a result, inferential comparisons were limited to VS and HS crowns luted with Ketac Cem®, which exhibited measurable failure within the load limit. An independent-samples t-test (α = 0.05) was used to compare their mean fracture resistance. The failure classification of each specimen (intact, cracked, or fractured) is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The number of fractured and cracked CRP crowns and means of fracture load.

3. Results

3.1. Fracture Resistance

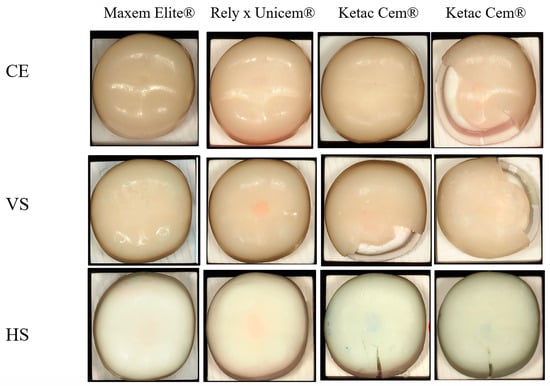

All crowns luted with Maxcem Elite® and RelyX Unicem® withstood the 2000 N load limit without visible cracks or fractures. In contrast, the Ketac groups exhibited lower fracture resistance and distinct failure modes. In the CE group, four of eleven crowns fractured slightly beyond 2000 N. Although mean values exceeded 2000 N, fractures occurred two to three seconds after the load limit was reached. VS-Ketac specimens showed seven fractures and four cracks (mean: 1795.2 ± 156.7 N), while all HS-Ketac specimens exhibited cracks without complete fracture (mean: 1732.6 ± 127.3 N) (Table 2). Representative failures are shown in Figure 5. The horizontal rows represent each ceramic material luted with different cements, whereas the vertical columns represent each ceramic material luted with the same cement. Due to the variation in fracture patterns among ceramics within the Ketac Cem® group, this group is presented in two vertical rows to clearly illustrate the differences.

Figure 5.

Post-fracture surface appearance of CRP crowns cemented with three luting agents. CE = Cerasmart® 270; VS = VarseoSmile Crown Plus®; HS = Hassawat-01. Rows represent the crown materials ((top): CE; (middle): VS; (bottom): HS), and columns represent the cement types (Maxcem Elite®, RelyX Unicem®, and two representative Ketac Cem® specimens). Each image illustrates the characteristic failure pattern for that material–cement combination. Resin-cemented groups (Maxcem Elite® and RelyX Unicem®) generally showed minimal surface disruption, whereas Ketac Cem® frequently produced visible crack lines, surface chipping, and cohesive cement remnants.

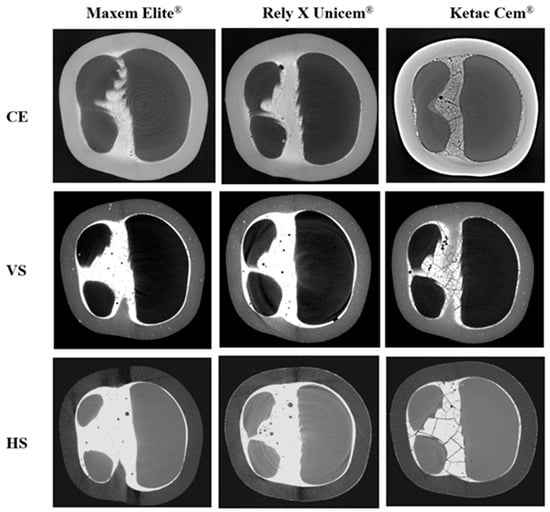

3.2. Micro-CT Analysis

Micro-CT images (Figure 6) revealed distinct differences in cement integrity. Maxcem Elite® showed dense and homogeneous layers with minimal localized voids. RelyX Unicem® displayed slightly more voids but retained a continuous and radiopaque interface. In contrast, Ketac Cem® exhibited reduced radiopacity, uneven cement distribution, and numerous voids and crack-like defects, indicating poor adaptation and compromised structural integrity.

Figure 6.

Micro-CT cross-sections showing internal cement morphology of CRP crowns after fracture testing. CE = Cerasmart® 270; VS = VarseoSmile Crown Plus®; HS = Hassawat-01. Rows indicate crown materials (CE, VS, HS), and columns indicate luting cements (Maxcem Elite®, RelyX Unicem®, and Ketac Cem®). Resin cements (Maxcem Elite® and RelyX Unicem®) produced uniform, low-void interfaces, while Ketac Cem® showed extensive voids, crack-like defects, and irregular distribution, especially in DLP-printed VS and HS crowns.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the influence of CRP material type and the elastic modulus of the luting cement on fracture resistance. It was hypothesized that differences in filler content, matrix composition, and modulus compatibility at the adhesive interface could affect performance under load. Both null hypotheses predicting no effect were rejected. All crowns luted with the resin-based cements Maxcem Elite® and RelyX Unicem® withstood loads greater than 2000 N without failure, whereas those luted with Ketac Cem® showed lower fracture resistance and visible failures, especially in the DLP-printed groups. These findings confirm that both the material type and the cement significantly influence fracture resistance.

Filler composition played a decisive role in the fracture behavior of the CRP crowns. CE, a milled hybrid ceramic, contains 71 wt.% nanofillers, consisting of 20 nm silica and 300 nm barium-glass (BG) particles [49]. Because BG has a refractive index compatible with the resin matrix (RI approx. 1.53), it can enhance optical homogeneity, radiopacity, and mechanical strength [50,51,52,53]. These properties likely contributed to the superior fracture resistance observed in CE-Ketac specimens. In contrast, VS is a DLP-printed composite containing 30 to 50 wt.% silanized glass fillers (approx. 0.7 µm) embedded in a UDMA/TEGDMA/Bis-EMA matrix and polymerized with diphenyl 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl phosphine oxide (TPO) initiators [50,54,55]. Although the absence of BG in VS may contribute to its lower fracture resistance, this interpretation should be viewed cautiously. CE and VS differ in both filler composition and filler loading, making it difficult to isolate the effect of any single variable. In the current HS prototype, filler composition also remains a confounding factor. The individual effects of BG and alumina on mechanical behavior cannot yet be distinguished. To clarify their roles, HS will need to be reformulated in several controlled versions, for example, with and without BG and with varying amounts of alumina, while keeping viscosity within the acceptable DLP printing range. Such targeted formulation studies are essential for identifying the contribution of each filler and should be a primary focus of future work.

HS, another DLP-printed material, comprises 38 wt.% non-silanized glass and alumina fillers with an average particle size of 0.7 µm. Although alumina reinforcement is associated with favorable wear resistance and biocompatibility [5,56], its inherently high hardness, low fracture toughness, and lack of silane coupling likely contributed to the superficial crack patterns, rather than catastrophic fractures, observed in the HS–Ketac specimens. The lower filler loading and higher resin fraction relative to CE may also explain the reduced fracture resistance of HS. Consequently, HS exhibited lower mechanical strength than CE but did not differ significantly from VS, while its fracture loads remained above the maximum physiological masticatory forces reported for natural dentition. It should be noted that although higher filler content generally enhances mechanical properties by reinforcing the resin matrix, it also increases viscosity and promotes particle agglomeration, which can impair material homogeneity and compromise mechanical reliability. HS demonstrated a printable viscosity of approximately 1.054 Pa·s, measured using a rotational Brookfield DV-E viscometer (Brookfield Viscometers Ltd., Harlow, UK; controlled RPM, room temperature conditions), which falls within the accepted viscosity window for DLP printing (0.4 to 3.5 Pa·s) [57,58,59].

In addition to filler characteristics, the polymer matrix critically influences the mechanical performance of CRP materials. CE features a cross-linked network of UDMA, Bis-MEPP, and dimethacrylates, producing a rigid yet moderately flexible matrix suitable for milled restorations [60]. This likely accounts for the delayed fractures in CE specimens, occurring seconds after peak load and suggesting gradual crack propagation and internal stress redistribution. VS, optimized for DLP printing, uses Bis-EMA, which allows low viscosity and high light transmission. Combined with TPO-based initiators, this formulation enables rapid and high-resolution curing [61,62,63]. However, the resulting resin matrix may exhibit lower cross-link density and reduced toughness, contributing to the catastrophic fractures seen in VS-Ketac specimens. HS incorporates a resin matrix dominated by Urethane acrylate (UA) and supplemented by 2-phenoxyethyl acrylate, tripropylene glycol diacrylate, and trimethylolpropane triacrylate (61.5 wt.% total resin) to improve elasticity and fracture toughness [19]. This accounts for the plastic deformation and surface cracking, rather than complete failure, observed in HS crowns. However, UA systems have reduced rigidity, limited light penetration, and poorer esthetics, particularly when combined with opaque fillers such as alumina [5,56]. These findings highlight the role of the matrix in stress absorption and redistribution. CE benefits from its stiff cross-linked network. VS prioritizes printability at the expense of strength, whereas HS achieves crack resistance through greater ductility but sacrifices rigidity. To optimize HS, matrix–filler interactions could be enhanced through zirconia co-reinforcement [64,65,66,67] or the incorporation of barium-glass (BG) fillers to boost strength, radiopacity, and esthetics [50,51,52,53]. Raising BG or bioactive filler content to 60 wt.% or more may align these materials with ADA ceramic criteria and improve overall performance [57,68,69].

Beyond ceramic composition, our findings confirm that the elastic modulus of the luting cement is a critical determinant of fracture resistance in CRP crowns, consistent with prior FEA studies showing that cement stiffness strongly influences intra-ceramic stress distribution [31,32,33,38]. In this study, crowns luted with resin cements of intermediate-to-high modulus, Maxcem Elite® approx. 4 GPa and RelyX Unicem® approx. 13 GPa) consistently withstood loads exceeding 2000 N. In contrast, the stiffer glass-ionomer (GI) cement (Ketac Cem® approx. 20 GPa), markedly reduced fracture resistance. The poor performance of Ketac Cem® can be attributed not only to its micromorphological behavior but also to its chemical bonding mechanism. Glass-ionomer cements rely on an acid–base reaction between polyacrylic acid and fluoroaluminosilicate glass to form ionic bonds. Although this enables limited adhesion to tooth substrates, Ketac does not bond chemically to silanized ceramic or resin-based CRP surfaces. In contrast, resin cements form covalent bonds with both ceramics and primed dentin, creating a stronger and reinforced monobloc that improves load transfer and fracture resistance [70]. In addition to weaker bonding, the relatively high elastic modulus of Ketac Cem® concentrates tensile stresses at the crown–cement interface rather than dissipating them through the restoration. This combination of insufficient adhesion and unfavorable stress distribution explains the significantly lower fracture loads observed in Ketac-luted specimens, especially in the DLP-printed CRP groups. These findings align with previous studies on lithium disilicate and zirconia-reinforced ceramics, which also reported the lowest failure loads when glass-ionomer cements were used and recommended against their use for bonded ceramic restorations [70,71]. Our results differ from those of Al-Wahadni et al., who found minimal influence of cement type when testing IPS Empress and In-Ceram crowns on natural premolars [72]. This discrepancy likely reflects the heterogeneity of natural dentin, whose variable modulus, hydration, and tubule structure can mask cement-related mechanical effects. In the present study, standardized resin dies were intentionally used to minimize substrate variability, allowing the influence of cement stiffness and bonding mechanisms to be observed more clearly. Nevertheless, validation of using natural teeth is still needed to confirm clinical relevance under more complex biomechanical conditions.

Overall, the findings indicate that resin cements with an intermediate-to-high elastic modulus improve the fracture resistance of CRP-based crowns more effectively than glass-ionomer cement. This supports the recommendations of Lia et al. [38] and Shahrbaf et al. [37], who proposed that intermediate-modulus cements reduce interfacial stress and prevent excessive deformation, whereas very low modulus cements (approx. 1.8 GPa) provide insufficient mechanical support. Importantly, our results challenge the assumption that a higher cement modulus universally improves fracture behavior. Although Dong et al. [29] reported reduced ceramic stress when stiff cements were modulus-matched to ceramic, the high-modulus Ketac Cem® increased internal stress within the cement layer and promoted cohesive failure in the present study. This outcome is consistent with Davidson et al. [73], who reported microcracking and structural disruption in thin GI layers due to shrinkage. While Ha et al. [39] reported acceptable performance of GI under zirconia crowns, the lower-modulus CRP materials used in our study (CE approx. 9.6 GPa; VS approx. 4.4 GPa; and HS approx. 4.75 GPa) performed more favorably when luted with resin cements of compatible modulus. Collectively, these results reinforce the view highlighted by Thompson et al. [34] that interfacial stiffness and adaptation are more important than reliance on highly rigid cements such as zinc phosphate [29,34,73]. Resin cements with an intermediate-to-high elastic modulus appear to provide the most favorable balance, provided that viscosity and cement thickness are properly controlled.

Micro-CT analysis provided visual confirmation that supported the observed mechanical behavior. Crowns luted with Maxcem showed the fewest internal voids, followed by those luted with RelyX, whereas Ketac displayed the highest void volume and numerous crack-like defects. These flaws likely served as stress concentrators, contributing to micromotion and weakening of the interface [74,75,76,77]. Although RelyX showed slightly more voids than Maxcem, the absence of radiographic cracks suggests that these voids were likely entrapped microbubbles rather than stress-induced failures [78,79]. In contrast, the extensive voids and cracks observed in Ketac may be attributed to its high stiffness, limited flowability, and poor chemical adhesion to low-modulus CRPs. Under thin-film conditions, GI cements are known to undergo shrinkage-induced microcracking, particularly when bonded to compliant substrates such as polymer-based ceramics [73]. Clinically, despite offering chemical bonding potential, GI cements lack sufficient fracture toughness and are susceptible to internal fracturing under functional occlusal loads [39,73]. It is also important to note that the potential chemical bonding of GI cements, typically observed when interacting with dentin, may have been limited in this study due to the use of resin dies, which do not provide ionic bonding sites like natural tooth substrates. This material mismatch may have further contributed to the weak interfacial adaptation and reduced stress distribution observed in the GI groups. Resin-based cements, by contrast, demonstrated better interfacial adaptation and internal homogeneity, reinforcing their role in enhancing the fracture resistance of CRP restorations.

Although the micro-CT assessment was qualitative, it effectively illustrated morphological differences between the cement groups that correlated with mechanical outcomes. The scanning parameters used in this study (67 kV, 41 µA, 10 µm voxel size) offer sufficient resolution for more detailed morphometric analysis. Future studies could incorporate CTAn-based three-dimensional volumetric analysis to quantify porosity-related parameters, such as void volume, void fraction, and void number density, within the cement interface. This quantitative approach will enable a more comprehensive understanding of how internal microstructure influences fracture behavior across different crown–cement systems.

In this study, VS crowns cemented with RelyX Unicem® withstood loads greater than 2000 N, markedly higher than the 1629 ± 118 N reported by Suksuphan et al. [27] for the same material-cement combination. This discrepancy may be attributable to differences in pre-testing protocols. In our study, specimens were stored dry at 37 °C before micro-CT and mechanical testing, whereas Suksuphan et al. stored their specimens in water. Water exposure can compromise the mechanical integrity of CRP materials and luting cements, particularly moisture-sensitive GI types, by accelerating cement dissolution, reducing cohesion, and weakening the filler–matrix bond [80,81,82]. Previous studies show that water storage and thermocycling induce microcrack formation and structural degradation in CRPs, primarily through polymer plasticization, swelling, and silane hydrolysis [81,82,83,84]. Materials with higher resin content are especially vulnerable, due to increased water uptake promoting microcrack propagation, filler debonding, and esthetic deterioration [85]. Thus, the absence of water immersion in our study likely preserved the structural integrity of RelyX Unicem®, which may account for the higher fracture resistance observed. These findings underscore the importance of environmental conditions and specimen handling, in addition to material and cement selection, when evaluating CRP–cement performance.

These findings highlight that both the elastic modulus of the luting cement and the ceramic composition of CRP materials critically influence fracture resistance. Within the limitations of this study, all CRP crowns luted with resin-based cements withstood forces exceeding 2000 N. HS, a newly developed CRP composite, showed high crack resistance despite its esthetic limitations, supporting its potential use as a long-term interim crown. The high fracture resistance observed may be attributed to its polymer-rich matrix, which enhances energy absorption and crack deflection. However, this in vitro study was conducted under idealized laboratory conditions that excluded water storage, thermocycling, and complex occlusal loading, which limits direct clinical extrapolation.

As a first-generation prototype, HS still lacks comprehensive characterization data essential for material validation, including degree of conversion, filler–matrix interfacial bonding, polymer network quality, and long-term stability. This study focused on evaluating the fracture resistance of HS relative to two commercially available CRP crown materials as an initial step toward determining the viability of alumina-reinforced CRPs. Although alumina was incorporated to enhance mechanical and optical properties, further investigation is needed to clarify its role in improving long-term strength, dimensional stability, and interfacial integrity, particularly under aging conditions that better simulate clinical use. Continued material optimization is necessary to achieve properties comparable to those of established CRP systems. Future studies should also assess the biomechanical behavior, optical performance (e.g., translucency, gloss, and color stability), and biocompatibility of HS. Potential strategies include alumina–zirconia co-reinforcement, incorporation of bioactive or radiopaque fillers, enhancement of filler–matrix bonding, and improvements in esthetic properties. In addition, testing on natural teeth is recommended, because resin dies do not replicate the biomechanical behavior of dentin. Complementary approaches such as finite element analysis (FEA), long-term fatigue testing, and clinical trials are also warranted to more comprehensively evaluate functional performance and clinical applicability.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, fracture strength depended on both the ceramic type and the modulus of the luting cement. High-modulus cements were unsuitable for low-modulus CRP crowns due to increased interfacial stress and promoted void formation. CE and VS showed adequate strength for definitive restorations, whereas HS, with its alumina fillers and UA matrix, appeared more suitable for long-term provisional use. Although alumina reinforcement enhanced strength, it reduced the translucency, color stability, and surface gloss of HS.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization, T.R., N.S., P.P.D., T.W. and N.K.; Methodology, T.R., N.S., P.P.D., T.W. and N.K.; Formal Analysis, T.R., N.S. and N.K.; Investigation, N.S. and T.W.; Resources, T.R. and T.W.; Data Curation, N.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, N.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, T.R. and N.S.; Visualization, N.S.; Supervision, T.R. and P.P.D.; Project Administration, T.R.; Funding Acquisition, N.S. and T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty of Dentistry, Thammasat University, Thailand, grant number DTGG 3/2567.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Dentistry, Thammasat University, for laboratory facilities and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRP | Ceramic-Reinforced Polymer |

| CE | Cerasmart® 270 |

| VS | VarseoSmile Crown Plus® |

| HS | Hassawat-01 |

| BG | Barium-glass |

| UA | Urethane acrylate |

| GI | Glass ionomer cement |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

References

- Naffah, N.; Ounsi, H.; Ozcan, M.; Bassal, H.; Salameh, Z. Evaluation of the adaptation and fracture resistance of three CAD-CAM resin ceramics: An in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 571–576. [Google Scholar]

- Blatz, M.B.; Conejo, J. The current state of chairside digital dentistry and materials. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, T.A. Materials in digital dentistry—A review. Dent. Clin. 2020, 32, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, F.; Boldt, J.; Gierthmuehlen, P. CAD/CAM ceramic restorative materials for natural teeth. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktarova-Valjakova, E.; Korunoska-Stevkovska, V.; Kapusevska, B.; Gigovski, N.; Bajraktarova-Misevska, C.; Grozdanov, A. Contemporary dental ceramic materials, a review: Chemical composition, physical and mechanical properties, indications for use. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.Y.; Pang, R.; Yang, J.; Fan, D.; Cai, H.; Jiang, H.B.; Han, J.; Lee, E.-S.; Sun, Y. Overview of several typical ceramic materials for restorative dentistry. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8451445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzatto, L.V.; Meneghetti, D.; Di Domênico, M.; Facenda, J.C.; Weber, K.R.; Corazza, P.H.; Borba, M. Effect of the type of resin cement on the fracture resistance of chairside CAD-CAM materials after aging. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2023, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshbabu, A.P.; Mohanty, S.; Bankoti, K.; Ghosh, P.; Dhara, S. Effect of alumina, silk and ceria short fibers in reinforcement of Bis-GMA/TEGDMA dental resin. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 70, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, M.; Nie, J.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Xing, Z. Synergy of solid loading and printability of ceramic paste for optimized properties of alumina via stereolithography-based 3D printing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 11476–11483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.-K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.-L.; Song, Y.-H.; Sun, K.; Xu, H.-P.; Dang, Z.-M. Particle packing theory guided multiscale alumina filled epoxy resin with excellent thermal and dielectric performances. J. Mater. 2022, 8, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Lim, Y.J.; Kwon, H.B.; Kim, M.J. Effect of post-curing time on the color stability and related properties of a tooth-colored 3D-printed resin material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126, 104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intralawan, N.; Wasanapiarnpong, T.; Didron, P.P.; Rakmanee, T.; Klaisiri, A.; Krajangta, N. Surface Discoloration of 3D Printed Resin-Ceramic Hybrid Materials against Various Stain Beverages. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2022, 15, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharif, S.O.; Akil, H.B.M.; El-Aziz, N.A.A.; Ahmad, Z.A.B. Effect of alumina particles loading on the mechanical properties of light-cured dental resin composites. Mater. Des. 2014, 54, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, T.; Erdelt, K.-J.; Güth, J.-F.; Edelhoff, D.; Schubert, O.; Schweiger, J. Influence of pre-treatment and artificial aging on the retention of 3D-printed permanent composite crowns. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebieluch, W.; Kowalewski, P.; Grygier, D.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Printable and machinable dental restorative composites for cad/cam application—Comparison of mechanical properties, fractographic, texture and fractal dimension analysis. Materials 2021, 14, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, E.; Hey, J.; Beuer, F.; Yassine, J.; Hesse, B.; Weitkamp, T.; Gerber, J.; Schmidt, F. Microstructural investigation of hybrid CAD/CAM restorative dental materials by micro-CT and SEM. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K.; Okido, M. Osteoconductivity control based on the chemical properties of the implant surface. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L.M.; Parnas, R.S.; King, S.H.; Schroeder, J.L.; Fischer, D.A.; Lenhart, J.L. Investigation of the thermal, mechanical, and fracture properties of alumina–epoxy composites. Polymer 2008, 49, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, J.-J.; Yang, T.-S.; Lee, W.-F.; Chen, H.; Chang, H.-M. Mechanical properties and biocompatibility of urethane acrylate-based 3D-printed denture base resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idrees, M.; Yoon, H.; Palmese, G.R.; Alvarez, N.J. Engineering toughness in a brittle vinyl ester resin using urethane acrylate for additive manufacturing. Polymers 2023, 15, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, G.; Bakhshi, H.; Meyer, W. Urethane-acrylate-based photo-inks for digital light processing of flexible materials. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, A.B.; Prochnow, C.; Pereira, G.K.; Segala, R.D.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Valandro, L.F. Fatigue performance of adhesively cemented glass-, hybrid-and resin-ceramic materials for CAD/CAM monolithic restorations. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, R.; Nagasawa, Y.; Infelise, A.; Bonadeo, G.; Ferrari, M. In vitro analysis of the fracture resistance of CAD-CAM Cerasmart molar crowns with different occlusal thickness. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2018, 3, 3074–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Utreja, A.K.; Sandhu, N.; Dhaliwal, Y.S. An innovative miniature bite force recorder. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu, R.A.M.; Pereira, M.D.; Furtado, F.; Prado, G.P.R.; Mestriner, W., Jr.; Ferreira, L.M. Masticatory efficiency and bite force in individuals with normal occlusion. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, M.B.; Okutan, Y. Marginal gap and fracture resistance of implant-supported 3D-printed definitive composite crowns: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2022, 124, 104216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksuphan, P.; Krajangta, N.; Didron, P.P.; Wasanapiarnpong, T.; Rakmanee, T. Marginal adaptation and fracture resistance of milled and 3D-printed CAD/CAM hybrid dental crown materials with various occlusal thicknesses. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 68, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Ender, A.; Egli, G.; Özcan, M.; Mehl, A. Fracture load of CAD/CAM-fabricated and 3D-printed composite crowns as a function of material thickness. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 2777–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.D.; Wang, H.R.; Darvell, B.W.; Lo, S.H. Effect of stiffness of cement on stress distribution in ceramic crowns. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 19, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yucel, M.T.; Yondem, I.; Aykent, F.; Eraslan, O. Influence of the supporting die structures on the fracture strength of all-ceramic materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lu, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Arola, D.; Zhang, D. The effects of adhesive type and thickness on stress distribution in molars restored with all-ceramic crowns. J. Prosthodont. Implant Esthet. Reconstr. Dent. 2011, 20, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadogiannis, Y.; Boyer, D.; Helvatjoglu-Antoniades, M.; Lakes, R.; Kapetanios, C. Dynamic viscoelastic behavior of resin cements measured by torsional resonance. Dent. Mater. 2003, 19, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saskalauskaite, E.; Tam, L.E.; McComb, D. Flexural strength, elastic modulus, and pH profile of self-etch resin luting cements. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 17, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. Microscopic and energy dispersive x-ray analysis of surface adaptation of dental cements to dental ceramic surfaces. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1998, 79, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, M.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, W. Influence of restorative material and cement on the stress distribution of endocrowns: 3D finite element analysis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusavice, K.; Tsai, Y. Stress distribution in ceramic crown forms as a function of thickness, elastic modulus, and supporting substrate. In Proceedings of the 16th Southern Biomedical Engineering Conference, Biloxi, MS, USA, 4–6 April 1997; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrbaf, S.; Van Noort, R.; Mirzakouchaki, B.; Ghassemieh, E.; Martin, N. Fracture strength of machined ceramic crowns as a function of tooth preparation design and the elastic modulus of the cement. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lia, Z.C.; White, S.N. Mechanical properties of dental luting cements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1999, 81, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.-R. Biomechanical three-dimensional finite element analysis of monolithic zirconia crown with different cement type. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrbaf, S.; Vannoort, R.; Mirzakouchaki, B.; Ghassemieh, E.; Martin, N. Effect of the crown design and interface lute parameters on the stress-state of a machined crown–tooth system: A finite element analysis. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, e123–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEGO Bremer Goldschlägerei Wilh. Herbst GmbH & Co. KG. VarseoSmile Crown Plus: Instructions for Use; BEGO: Bremen, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CERASMART™. The New Leader in Hybrid Ceramic Blocks; GC International AG: Luzern, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Izhack, G.; Shely, A.; Naishlos, S.; Glikman, A.; Frishman, L.; Meirowitz, A.; Dolev, E. The Influence of Three Different Digital Cement Spacers on the Marginal Gap Adaptation of Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Crowns Fabricated by CAD-CAM System. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, T.; Erdelt, K.J.; Raith, S.; Schneider, J.M.; Stawarczyk, B.; Beuer, F. Effects of differing thickness and mechanical properties of cement on the stress levels and distributions in a three-unit zirconia fixed prosthesis by FEA. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, A.; Stellini, E.; Alageel, O.; Alhotan, A. Comparison of mechanical and surface properties of two 3D printed composite resins for definitive restoration. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 839.e1–839.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassila, L.; Novotny, R.; Säilynoja, E.; Vallittu, P.K.; Garoushi, S. Wear behavior at margins of direct composite with CAD/CAM composite and enamel. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallis, K.; Griggs, J.A.; Woody, R.D.; Guillen, G.E.; Miller, A.W. Fracture resistance of three all-ceramic restorative systems for posterior applications. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2004, 91, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Harada, A.; Inagaki, R.; Kanno, T.; Niwano, Y.; Milleding, P.; Örtengren, U. Fracture resistance of monolithic zirconia molar crowns with reduced thickness. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2015, 73, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkian, P.; Mortazavi Najafabadi, S.; Ghashang, M.; Grzelczyk, D. Glass-Ceramic Fillers Based on Zinc Oxide–Silica Systems for Dental Composite Resins: Effect on Mechanical Properties. Materials 2023, 16, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Balbinot, G.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Ogliari, F.A.; Collares, F.M. Niobium silicate particles as bioactive fillers for composite resins. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, A.; Palin, W.; Burtscher, P. Refractive index mismatch and monomer reactivity influence composite curing depth. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.C. Radiopacity vs. composition of some barium and strontium glass composites. J. Dent. 1987, 15, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R. X-Ray-Opaque Reinforcing Fillers for Composite Materials: Progress Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-M.; Lai, Y.-L.; Lee, S.-Y. Mechanical properties, accuracy, and cytotoxicity of UV-polymerized 3D printing resins composed of Bis-EMA, UDMA, and TEGDMA. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattera, A.C.A.; Morganti, F.A.; de Souza Balbinot, G.; Della Bona, A.; Collares, F.M. The influence of filler load in 3D printing resin-based composites. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfakhri, F.; Alkahtani, R.; Li, C.; Khaliq, J. Influence of filler characteristics on the performance of dental composites: A comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 27280–27294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, P.V.; Sayed Ahmed, A.; Alford, A.; Pitttman, K.; Thomas, V.; Lawson, N.C. Characterization of materials used for 3D printing dental crowns and hybrid prostheses. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 36, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo-Pereira, R.; Carpio, D.; Torres, O.; Carvalho, O.; Silva, F.; Henriques, B.; Özcan, M.; Souza, J.C.M. The influence of inorganic fillers on the light transmission through resin-matrix composites during the light-curing procedure: An integrative review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5575–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.-M. Synthesis and Formulation of PCL-Based Urethane Acrylates for DLP 3D Printers. Polymers 2020, 12, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GC. CERASMART™270. Force Absorbing Hybrid Ceramic CAD/CAM Block. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gc.dental%2Findia%2Fsites%2Findia.gc.dental%2Ffiles%2Fproducts%2Fdownloads%2Fcerasmart270%2Fleaflet%2FLFL_CERASMART270_en.pdf&psig=AOvVaw2XtN_4TvLccOMbzEyjQ7la&ust=1743678127901000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CAYQrpoMahcKEwiYycW_mbmMAxUAAAAAHQAAAAAQBA (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Mudhaffer, S.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J. Effect of print orientation on sorption, solubility, and monomer elution of 3D printed resin restorative materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 134, 461.e1–461.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacarne, J.; Carvalho, R.M.; de Goes, M.F.; Svizero, N.; Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R.; Yiu, C.K.; de Oliveira Carrilho, M.R. Water sorption/solubility of dental adhesive resins. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghaus, E.; Klocke, T.; Maletz, R.; Petersen, S. Degree of conversion and residual monomer elution of 3D-printed, milled and self-cured resin-based composite materials for temporary dental crowns and bridges. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2023, 34, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, N.M.; Badawi, M.F.; Fatah, A.A. Effect of reinforcement of high-impact acrylic resin with zirconia on some physical and mechanical properties. Arch. Oral Res. 2008, 4, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ellakwa, A.E.; Morsy, M.A.; El-Sheikh, A.M. Effect of aluminum oxide addition on the flexural strength and thermal diffusivity of heat-polymerized acrylic resin. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 17, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Hu, X.; Yu, G.; Deng, X. Preparation and properties of dental zirconia ceramics. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing Miner. Met. Mater. 2008, 15, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, A.K.; Song, H.-Y.; Lee, B.-T. Microstructure and mechanical properties of porous yttria stabilized zirconia ceramic using poly methyl methacrylate powder. Scr. Mater. 2006, 54, 2081–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, P.V.; Lawson, N.C.; Givan, D.A.; Arce, C.; Roberts, H. Enamel wear and fatigue resistance of 3D printed resin compared with lithium disilicate. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 523.e1–523.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszewski, Z.; Kulbacka, J.; Nowakowska-Toporowska, A. Mechanical properties, cytotoxicity, and fluoride ion release capacity of bioactive glass-modified methacrylate resin used in three-dimensional printing technology. Materials 2022, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, F.; Altwaim, M.; Alshuwaier, A.S.; Al Deeb, M.; Alfawaz, Y.; Alrabiah, M.; Abduljabbar, T. Influence of Bioactive, Resin and Glass Ionomer luting cements on the fracture loads of dentin bonded ceramic crowns. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addazio, G.; Santilli, M.; Rollo, M.L.; Cardelli, P.; Rexhepi, I.; Murmura, G.; Al-Haj Husain, N.; Sinjari, B.; Traini, T.; Özcan, M. Fracture resistance of Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic crowns cemented with conventional or adhesive systems: An in vitro study. Materials 2020, 13, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wahadni, A.M.; Hussey, D.L.; Grey, N.; Hatamleh, M.M. Fracture resistance of aluminium oxide and lithium disilicate-based crowns using different luting cements: An in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2011, 10, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; Van Zeghbroeck, L.; Feilzer, A. Destructive stresses in adhesive luting cements. J. Dent. Res. 1991, 70, 880–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzun, İ.H.; Malkoç, M.A.; Keleş, A.; Öğreten, A.T. 3D micro-CT analysis of void formations and push-out bonding strength of resin cements used for fiber post cementation. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandini, S.; Goracci, C.; Monticelli, F.; Borracchini, A.; Ferrari, M. SEM evaluation of the cement layer thickness after luting two different posts. J. Adhes. Dent. 2005, 7, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Wang, H.-W.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, C.-L. Evaluation of early resin luting cement damage induced by voids around a circular fiber post in a root canal treated premolar by integrating micro-CT, finite element analysis and fatigue testing. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, H.; Lin, C.-L. Early resin luting material damage around a circular fiber post in a root canal treated premolar by using micro-computerized tomographic and finite element sub-modeling analyses. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 51, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinell, T.; Schedle, A.; Watts, D.C. Polymerization shrinkage kinetics of dimethacrylate resin-cements. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroudi, K.; Saleh, A.M.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Shrinkage behaviour of flowable resin-composites related to conversion and filler-fraction. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojon, P.; Kaltio, R.; Feduik, D.; Hawbolt, E.B.; MacEntee, M.I. Short-term contamination of luting cements by water and saliva. Dent. Mater. Dent. Mater. 1996, 12, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egilmez, F.; Ergun, G.; Cekic-Nagas, I.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L.V. Does artificial aging affect mechanical properties of CAD/CAM composite materials. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, N.; Gultekin, P.; Turp, V.; Akgungor, G.; Sen, D.; Mijiritsky, E. Evaluation of five CAD/CAM materials by microstructural characterization and mechanical tests: A comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauvahutanon, S.; Takahashi, H.; Shiozawa, M.; Iwasaki, N.; Asakawa, Y.; Oki, M.; Finger, W.J.; Arksornnukit, M. Mechanical properties of composite resin blocks for CAD/CAM. Dent. Mater. J. 2014, 33, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druck, C.C.; Pozzobon, J.L.; Callegari, G.L.; Dorneles, L.S.; Valandro, L.F. Adhesion to Y-TZP ceramic: Study of silica nanofilm coating on the surface of Y-TZP. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2015, 103, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassila, L.; Uctasli, M.B.; Wada, K.; Vallittu, P.K.; Garoushi, S. Effect of different beverages and polishing techniques on colour stability of CAD/CAM composite restorative materials. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2024, 11, 40591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.