Abstract

This work presents a detailed analysis of polysulfone (PSF) based mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) modified with NiMOF@MGO for water purification. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles were synthesized and incorporated into the NiMOF@GO framework, with successful formation confirmed by FT-IR, XRD, BET, TGA, and SEM analyses. Membranes were prepared via phase inversion and modified with varying NiMOF@MGO contents. SEM, AFM, and contact angle analyses demonstrated enhanced membrane hydrophilicity with increasing MOF concentration, reducing the contact angle from 59.74° (0.05 wt%) to 49.70° (0.2 wt%). The highest flux of 117.85 L/m2·h was observed for the PMM-0.2 membrane. Heavy metal removal was most efficient at pH 6, with the PMM-0.1 membrane achieving 95.97% and 95.92% rejection for Pb2+ and Cu2+, respectively. In oil-water separation, PMM-0.1 exhibited optimal performance, with a water flux of 45.84 L/m2·h. Antifouling tests showed the PMM-0.2 membrane had the highest flux recovery of 85.97%, indicating improved fouling resistance. Overall, incorporation of NiMOF@MGO significantly enhanced membrane hydrophilicity, flux, selectivity and antifouling performance, demonstrating its potential for advanced water purification applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years, water pollution driven by rapid urbanization and industrialization has emerged as a critical environmental issue, primarily due to the discharge of heavy metals that contaminate water resources and aquatic ecosystems [1]. Even at trace concentrations, heavy metals are highly toxic and tend to bioaccumulate within both aquatic and terrestrial food chains. For example, exposure to lead ions adversely affects human health by impairing the cardiovascular system, kidneys, and brain, while mercury exposure has been linked to severe immune and neurological dysfunctions [2]. Over the past decades, numerous conventional methods have been developed to remove heavy metals from wastewater [3]. However, these traditional water treatment approaches are often insufficient for complete removal, thereby necessitating the development of more advanced technologies such as membrane filtration. Compared with conventional separation and desalination methods (e.g., distillation), membrane-based processes offer several advantages, including compactness, robustness, scalability, and improved energy efficiency [4]. Consequently, membrane separation has become a cornerstone in purification technologies [5], accounting for up to 53% of global processes for producing purified water. Its wide applicability in treating brackish water, wastewater, and seawater desalination for potable reuse stems from its operational simplicity, chemical-free nature, cost-effectiveness, absence of phase change, high efficiency, and strong removal capacity [6]. Acting as selective barriers, membranes are considered environmentally benign technologies capable of eliminating a wide variety of pollutants from water streams [7,8]. The application of reverse osmosis, nanofiltration, and mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) in the separation of heavy metals has been thoroughly investigated and discussed in prior studies [9,10]. Furthermore, advancements in materials science have enabled the discovery of novel building blocks and polymers, facilitating the design of next-generation separation membranes that meet key criteria: (1) uniform and well-defined pore size, (2) narrow pore size distribution, (3) ultrathin active layers, and (4) enhanced permeability [11,12].

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline porous polymers formed through the coordination of metal ions with organic linkers. Their highly ordered and porous architectures impart exceptional stability, low density, and a remarkably large surface area [13]. In addition, the versatile synthetic routes available for MOFs enable precise control over pore size distribution, tunability of pore dimensions, and the incorporation of diverse surface functionalities. These unique attributes make MOFs highly promising for a broad spectrum of applications, particularly in separation processes [14]. Although MOFs inherently possess favorable physical and chemical properties for such applications, these characteristics can be further enhanced through various modification strategies [15]. In this context, the development of MOF-based composites with nanoparticles, such as iron oxide (Fe3O4) and silica, has been extensively reported and applied in separation technologies [16,17]. In this study, a nickel-based MOF (Ni-MOF) was selected as the filler material owing to its strong affinity for heavy metal ions and proven potential in water purification applications [18]. Ni-MOF exhibits a high specific surface area, good hydrophilicity, excellent thermal and cycling stability, and superior chemical resistance in aqueous environments compared with other commonly studied MOFs that often undergo partial degradation [19]. Furthermore, its tunable porosity and strong compatibility with polymer matrices facilitate uniform dispersion within the membrane, enhancing permeability and selective removal of toxic metal ions [20]. Moreover, the limited stability and partially inaccessible pores of MOFs restrict their full utilization. Integrating MOFs with two-dimensional (2D) materials can yield multifunctional hybrid structures that combine the advantages of both components, offering a promising route for developing advanced functional materials [21].

The aim of this research is to fabricate and characterize polysulfone (PSf) membranes modified with NiMOF@MGO for water purification. Therefore, first, magnetic nanoparticles are synthesized and combined with NiMOF@GO, and then MMMs are produced with the help of synthesized nanoparticles and used for water purification in membrane-based filtration system.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Materials

Merck provided the following list of chemicals: sodium acetate (C2H3NaO2), ferric chloride (FeCl3), ethylene glycol (C2H6O2), terephthalic acid (C8H6O4) (TA), N,N dimethylformamide (DMF), nickel nitrate (Ni(NO3)2), ethanol (C2H6O), sulphuric acid (H2SO4), potassium permanganate (KMnO4), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2), copper nitrate (Cu(NO3)2), solvent N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP > 95%), polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP > 97%), ethanol (C2H5OH), and toluene (C7H8). Following that, Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) supplied bovine serum albumin (BSA), and BASF supplied the polysulfone polymer (PSF).

2.2. Synthesis of NiMOF@MGO Nanoparticles

The synthesis was performed in multiple steps. Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles were prepared according to the method reported in the literature [22,23]. Graphene oxide (GO) was synthesized following the procedure described in [24,25]. Subsequently, Ni-based metal–organic framework (NiMOF) was obtained using the protocol outlined in [26].

In the last and final step, the NiMOF@GO nanoparticles were functionalized with Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles by ultrasonically dispersing 50 mg of NiMOF@GO in 4 mL of DMF (35 kHz) for two hours. Six milliliters of DMF were used to suspend 40 milligrams of FeO4@SiO2 nanoparticles in a separate container. The two mixtures were combined and constantly swirled for six hours. An external magnet was then used to separate the NiMOF@MGO hybrid, which was then washed three times with 50 mL of toluene before being dried for storage [26].

2.3. Preparation of MMMs

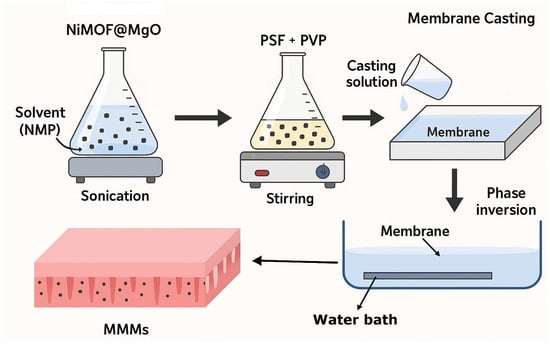

The MMMs were developed using PSF as a base polymer and NiMOF@MGO nanoparticles as filler via phase inversion method as depicted in Figure 1. The membrane-forming solution was prepared by first dissolving 0.5 wt% PVP in 82 wt% NMP under magnetic stirring for 1 h. Subsequently, 17.5 wt% PSF was introduced gradually and mixed until a homogeneous solution was obtained. The mixture was then transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask equipped with a magnetic bar and stirred continuously for one day. The solution was ultrasonically degassed at room temperature for a further 24 h to eliminate trapped air bubbles [27]. The polymer solution was uniformly applied to a 20 × 20 cm glass plate and placed in a distilled water bath at 25 °C to promote phase inversion [28]. Then, it was placed in separate distilled water bath for a day, until the remaining solvent was removed, and then stored in distilled water. To modify the membrane with NiMOF@MGO nanoparticles, all the above steps were performed and different concentrations of NiMOF@MGO nanoparticles were added to the polymer solution. Table 1 shows the conditions for the fabrication of MMMs.

Figure 1.

The schematic illustration of membrane developments steps.

Table 1.

Dope solution composition.

2.4. Characterization of Developed Materials

To investigate functional groups, an FT-IR spectrometer (VERTEX 70, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used. An atomic force microscope was used to analyze the surface as well as the structural characteristics of the membranes (AFM, JPK NanoWizard II, JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany). The water contact angle of the developed membranes was measured with an optical contact angle goniometer (CAG-20 SE, Jikan, Tehran, Iran). A field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-3400N, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used to investigate the morphologies of the nanoparticles and membranes. The thermal characteristics of the nanoparticles were evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, SDT-Q600, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA).

2.5. Evaluation of Membrane Filtration Performance

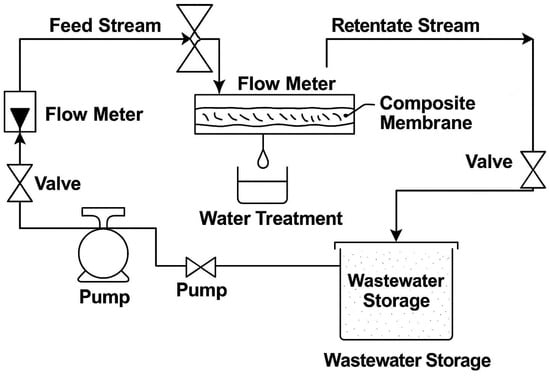

The membrane setup used to evaluate the performance of the developed membranes as shown in Figure 2, with an effective area of 14.45 cm2. The filtration performance was evaluated at 6 bar pressure, 3 L/min flow rate, for 1 h at ambient temperature. Aqueous heavy metal solutions were prepared by dissolving Pb(NO3)2, Cu(NO3)2, and Na2HAsO4·7H2O to a final concentration of 50 mg/L in deionized water. Oil with the properties described in Table 2 was used to prepare the solution for filtration.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation the membrane system for investigating the performance of developed composite membranes.

Table 2.

Oil properties.

Crude oil and distilled water were combined in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, wt%) as a surfactant. The mixture was vigorously stirred with a mechanical stirrer for 10 min to form a stable oil-in-water emulsion [29]. Water flux through the pristine as well as MMMs was calculated using Equations (1) and (2) [30].

Here, Am represents the effective membrane area, ΔV is the volume of water that permeates through the membrane, Δt is the filtration time, and ΔP denotes the applied pressure difference [30]. Similarly, Cp and Cf represent the concentrations of lead and copper in the permeate and in the feed solution, respectively. Heavy metal concentrations in the samples were determined using an atomic absorption spectrometer (280FS AA, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), while oil concentrations were measured with a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (UV-1900i, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.6. Antifouling Performance of Developed Membranes

The antifouling performance of the developed membranes was assessed using bovine serum albumin (BSA) filtration. Following preliminary measurements of the pure water flux, the membranes were filtered with the BSA solution for 120 min at 6 bar, and the permeate flux was noted. After the membranes were washed with deionized water, the flow of pure water through the cleaned membranes was measured, and Equation (4) was used to compute the flux recovery ratio (FRR). To assess membrane fouling further, the total fouling ratio (TFR), reversible fouling ratio (RFR), and irreversible fouling ratio (IFR) were calculated using the relevant Equations (5)–(7) [31].

where and denote the permeate fluxes measured before and after membrane fouling, respectively, while represents the flux recorded during the fouling process.

3. Results

The sections consist of two parts, one for the synthesized nanoparticles and the other for the developed membranes.

3.1. Characterization of Nanoparticles

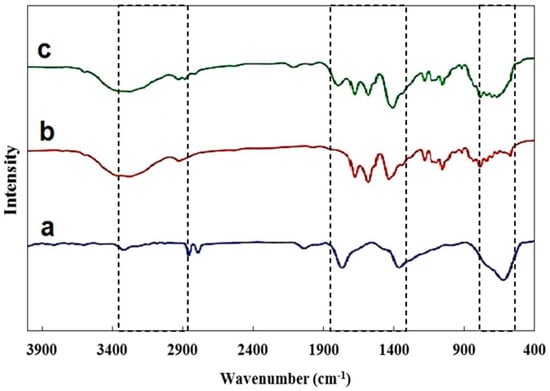

The FT-IR spectra of developed composite are shown in Figure 3. The existence of magnetic graphene oxide is confirmed by characteristic peaks seen at about 1439 cm−1, 1676 cm−1, and 2862 cm−1, which correspond to C=C, C=O, and C–H functional groups [32]. The bands at 1025 cm−1 and 1218 cm−1 are attributed to C–O stretching vibrations in the alkoxy and epoxy groups of GO [33,34]. A broad band around 3350 cm−1 indicates O–H stretching in carboxylic groups [35].

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectrum (a) Fe3O4@SiO (b) NiMOF@GO (c) NiMOF@MGO.

Additional peaks further confirm the incorporation of NiMOF: the band at 560 cm−1 is assigned to Ni–O bonds, while those at 1232 cm−1, 1234 cm−1, and 1662 cm−1 correspond to C–O stretching, aromatic C–C, and C=O stretching vibrations, respectively [36]. Peaks at 611 cm−1 and 1784 cm−1 are associated with Fe–O and Si–O groups [23,37]. Furthermore, the signals at 539 cm−1 (Ni–O) and 614 cm−1 (Fe–O) provide strong evidence for the successful incorporation of NiMOF and Fe3O4@SiO2 into GO. Finally, the band at 1780 cm−1, assigned to Si–O, confirms effective silica coating [36,38].

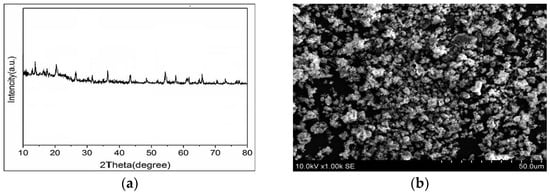

Figure 4a shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of NiMOF@MGO composite. As can be seen, Fe3O4 nanoparticles displayed unique diffraction peaks associated with the (1 1 1), (0 2 2), (1 1 3), (0 0 4), (2 2 4), (1 1 5), (0 4 4) and (5 5 3) planes [39,40,41]. Also, the peak appearing at 23° is attributed to the Si-O characteristic because of the magnetic silicate layer nanoparticles [42,43]. According to the X-ray diffraction pattern, weak peaks appeared at 2θ values around 11.4°, 13.1°, 17.8° and 24.9° which are consistent with the NiMOF structure [38], indicating the proper embedding of NiMOF on the GO surface.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD pattern, and (b) SEM image of NiMOF@MGO composite.

SEM was employed to investigate the morphology, particle size, and surface characteristics of the NiMOF@MGO nanoparticles. As shown in Figure 4b, the nanoparticles exhibit a nearly uniform morphology with well-dispersed structures. The typical particle size of the monodispersed nanoparticles is in the range of 30–55 nm, indicating a narrow and uniform size distribution.

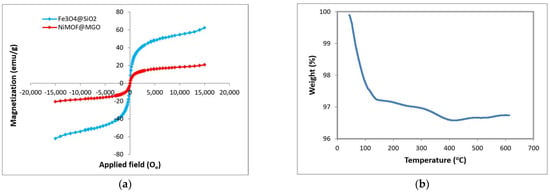

A vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) was used to assess magnetic characteristics of the nanoparticles at room temperature, and the resulting magnetic hysteresis loops, displayed as s-shaped curves, are shown in Figure 5a. The synthesized Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles exhibit higher magnetic strength compared to the NiMOF@MGO composite nanoparticles. The saturation magnetization (Mₛ) of the composite was determined to be in the range of 3.75 emu/g. Therefore, the synthesized NiMOF@MGO composite has favorable magnetic properties.

Figure 5.

(a) VSM and (b) TGA of NiMOF@MGO composite.

Figure 5b presents the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the NiMOF@MGO composite in the temperature range of 0–600 °C. An initial weight loss of approximately 2.75% around 100 °C is attributed to the evaporation of surface-adsorbed water as well as the release of water trapped within the bulk and internal sites of the composite. A further weight reduction of almost 3.47% occurs above 400 °C, which is mainly associated with the thermal degradation of organic components in the material [44].

3.2. Membrane Characterizations

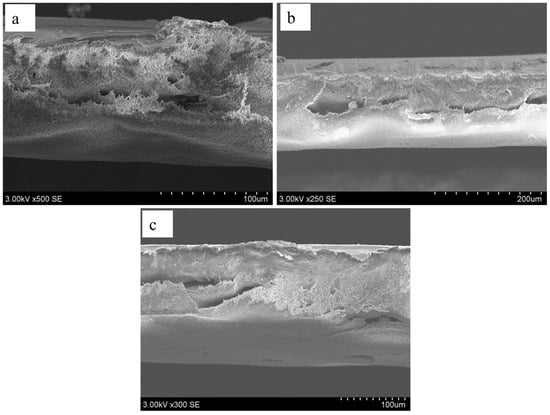

Figure 6 shows the cross-sectional view of the developed PSF and MMMs, highlighting the dominance of sponge-like morphology formed during phase inversion. This structure arises from controlled solvent–nonsolvent exchange, which ensures uniform polymer precipitation and prevents rapid demixing. Sponge-like networks, with their interconnected micropores and relatively uniform porosity, enhance mechanical stability and minimize the risk of collapse under operational conditions. Such morphology is advantageous for achieving balanced permeability and strength, as it provides adequate fluid transport pathways while maintaining structural integrity. Incorporation of NiMOF@GO further alters this morphology by acting as a pore-forming agent and disrupting polymer chain packing, resulting in increased porosity and surface roughness. SEM images confirm that NiMOF@GO-modified membranes exhibit a more open and irregular pore structure compared to pure PSF membranes. This enhanced roughness and porosity improve hydrophilicity, as MOF particles introduce polar functional groups that attract water molecules. Consequently, membranes containing NiMOF@GO demonstrate higher water flux and reduced fouling, making them highly suitable for filtration and separation applications [45,46].

Figure 6.

SEM cross-sections images of developed: (a) PSF, (b) PMM-0.1, and (c) PMM-0.2.

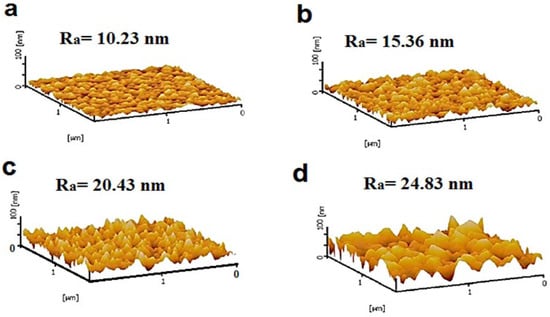

AFM was employed to characterize the surface topography of the fabricated membranes. The 3D AFM images of the developed membranes are presented in Figure 7, along with their corresponding average surface roughness (Ra) values. The results indicate that the incorporation of NiMOF@MGO increases the surface roughness of the MMMs compared to the pristine PSF membrane. Specifically, the PMM-0.2 membrane exhibits the highest Ra value of 24.83 nm. The observed increase in surface roughness correlates with the higher weight percentages of NiMOF@MGO in the polymer solutions used for membrane fabrication, which also increases the solution viscosity and the casting shear rate, both of which influence the membrane surface morphology. Higher-viscosity polymer solutions promote the formation of finer and more uniform pores, resulting in a rougher surface. This enhanced roughness contributes to increased membrane hydrophilicity and improved resistance to surface fouling [47,48].

Figure 7.

AFM images of membranes (a) PSF, (b) PMM-0.05, (c) PMM-0.1 and (d) PMM-0.2.

The hydrophilicity of the fabricated membranes was evaluated using contact angle measurements. As shown in Table 3, incorporating NiMOF@MGO into the membranes significantly reduced the water contact angle, indicating enhanced hydrophilicity. Specifically, the membrane containing 0.05 wt% composite exhibited a contact angle of 59.74°, which decreased to 17.84° (a reduction of 49.70°) when the composite concentration was increased to 0.2 wt%. This trend confirms that higher NiMOF@MGO content increases membrane hydrophilicity, attributable to the presence of hydrophilic functional groups within the NiMOF@MGO composite [49,50].

Table 3.

Contact angle measurements of developed membranes.

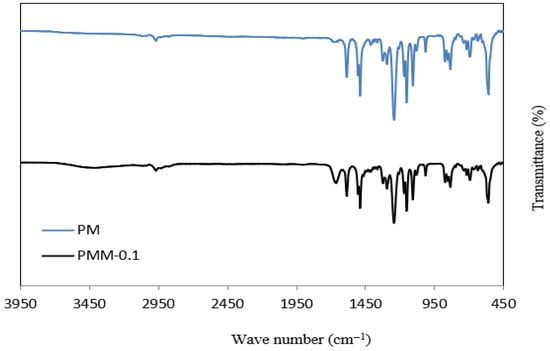

The FT-IR spectra of the PSF and PMM-0.1 membranes are shown in Figure 8. PSF groups are the source of the distinctive peaks at 1160 cm−1, 1301 cm−1, and 1403 cm−1, which represent symmetric O=S=O stretching, asymmetric O=S=O stretching, and aromatic C=C ring stretching vibrations, respectively [51,52]. Peaks in the range of 832–1111 cm−1 are attributed to Si–O functional groups and covalent bonding [53]. O-H stretching vibrations are shown by a wide band between 3200 and 3400 cm−1, which validates the existence of hydroxyl groups. The peak at 1433 cm−1 is associated with water absorption and –CH2 stretching [54], while the band at 3006 cm−1 corresponds to aromatic C–H vibrations. Furthermore, the peaks at 1522 cm−1 and 1726 cm−1 confirm strong interactions between MGO and the NiMOF@MGO composite surface [55,56].

Figure 8.

FT-IR Profiles of PSF and PMM-0.1 membranes.

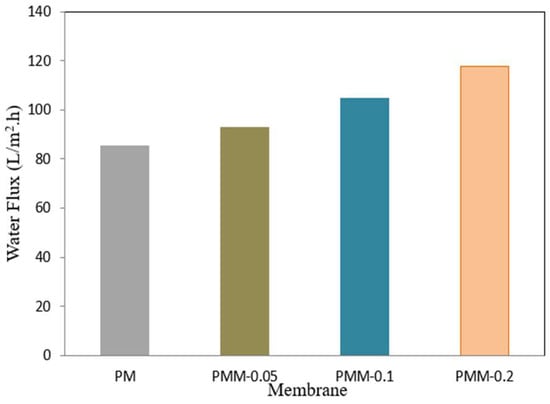

3.3. Results of Pure Water Flux Permeability of Deve006Coped MMMs

The pure water flux of the MMMs, measured during a 60 min period at a pressure of 6 bar and a flow velocity of 3 L/min, is shown in Figure 9. A key factor that sheds light on the hydrophilicity of the membranes is the water flow through the manufactured membranes [57,58]. When compared to the pristine PSF membrane, the MMMs incorporating NiMOF@MGO showed much greater water flow. The decreased hydrophilicity of the developed membrane is the reason for its comparatively low water flux (12.85 L/m2·h). PMM-0.2 showed the maximum water flux of 117.85 L/m2·h among the membranes under investigation, which is in line with its lower water contact angle and therefore higher hydrophilicity. The addition of NiMOF@MGO is responsible for the rise in water flow of these MMMs because it alters the average pore radius, increases surface microporosity, and improves membrane porosity, all of which promote increased water permeability [59].

Figure 9.

Permeation flux of pure water across developed membranes.

3.4. Separation Performance of Developed Membranes

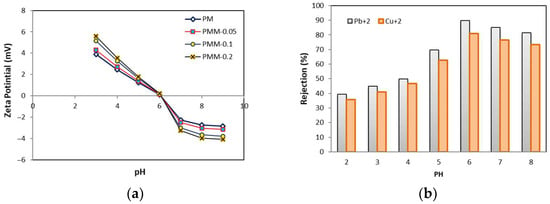

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of pH on the removal of heavy metals, specifically lead and copper. The membrane filtration experiments were conducted at a pressure of 6 bar for 60 min at ambient temperature. Solution pH is a critical parameter influencing both heavy metal separation and the surface charge of the membranes. In membrane processes, pH is often adjusted to enhance heavy metal removal efficiency [60,61]. The pH of the aqueous solution affects the surface charge of the MMMs, which becomes negative or positive at pH values above or below the membrane’s point of zero charge (pHpzc). Figure 10a shows the surface charge of the membranes at different pH values. The results indicate that the surface charge decreases from pH 2 to 6, with the pHpzc observed at approximately pH 6. Consequently, electrostatic attraction between the membrane and heavy metal ions is expected to increase as the pH rises from 2 to 6. Experiments conducted over a pH range of 3 to 8 showed that the rejection of heavy metals, including lead, mercury, and arsenic, increased with increasing pH. The highest rejection was observed at pH 6, likely due to enhanced electrostatic interactions between the membrane surface and the heavy metal ions under mildly acidic conditions [62].

Figure 10.

(a) Surface charge of composite membranes (b) Effect of pH on heavy metal rejection using PMM-0.05 membrane.

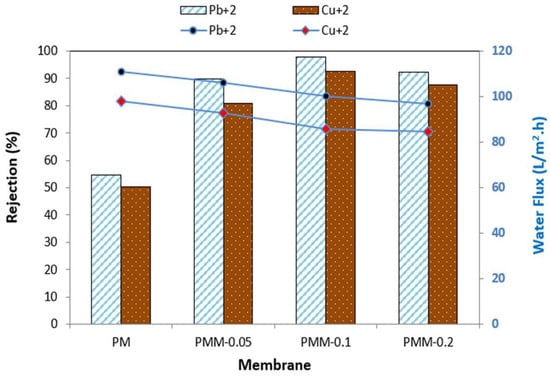

Figure 11 presents the heavy metal rejection (Pb2+ and Cu2+) and water permeation flux of the developed membranes measured at pH 6, 6 bar pressure, for 60 min at ambient temperature. The MMMs modified with NiMOF@MGO nanoparticles exhibited significantly higher rejection compared to the pristine PSF membrane. This enhanced performance is primarily attributed to the size-exclusion (sieving) and Donnan rejection mechanisms [63]. Rejection is also influenced by the hydrated radius of the ions, which affects their ability to diffuse through the membrane pores. Since Pb2+ has a larger hydrated radius than Cu2+, its rejection percentage is higher [64]. The study further demonstrated that increasing the NiMOF@MGO content in the polysulfone polymer solution improves the removal efficiency of Pb2+ and Cu2+. However, at higher loadings (0.2 wt%, PMM-0.2), the increased viscosity of the dope solution promotes the formation of an asymmetric membrane structure, which can block surface pores and reduce water permeability, resulting in lower water flux compared to the pristine PSF membrane. The optimal performance was observed for the PMM-0.1 membrane, achieving heavy metal rejections of 95.97% for Pb2+ with a water flux of 45.83 L/m2·h, and 75.92% for Cu2+ with a water flux of 78.87 L/m2·h.

Figure 11.

Heavy metal rejection and water flux across developed membranes.

3.5. Investigation of the Antifouling Properties of Developed Membranes

An essential parameter for assessing antifouling capabilities of membranes is the flow recovery ratio (FRR). Based on BSA filtration experiments, the reversible fouling ratio (RFR), irreversible fouling ratio (IFR), total fouling ratio (TFR), and FRR were calculated to evaluate the fouling behavior of the developed membranes, as shown in Table 4. Better flux restoration is associated with higher FRR values, whereas more efficient overall fouling management is indicated by lower IFR values. Due to the enhanced hydrophilicity imparted by the NiMOF@MGO modification, all MMMs exhibited higher flux recovery compared to the pristine PSF membrane. Another important factor influencing fouling behavior is membrane surface roughness; a rougher membrane has more surface area accessible for foulant adsorption, which can affect water flow [65,66]. While irreversible fouling arises from the stable adsorption of foulants on the membrane surface or inside the pores, causing pore obstruction and decreased flow, reversible fouling is associated with contaminants that may be eliminated by washing [67]. The inclusion of NiMOF@MGO into the membranes successfully minimized irreversible fouling. With a flux recovery of 97.85%, PMM-0.2 had the greatest antifouling performance among the developed MMMs.

Table 4.

Antifouling properties of developed membranes.

4. Conclusions

MMMs comprising PSF and NiMOF@MGO were fabricated and characterized analytically to study water purification performance. Incorporation of NiMOF@MGO significantly enhanced membrane hydrophilicity, as evidenced by the decrease in contact angle from 59.74° for 0.05 wt% composite to 17.84° (49.70°) for 0.2 wt%. When compared to the pristine PSF membrane, the MMMs showed a greater pure water flow, with the highest flux observed for the PMM-0.2 membrane (117.85 L/m2·h). Heavy metal removal was most effective at pH 6, with the PSF membrane demonstrating superior rejection compared to MMMs. The PMM-0.1 membrane achieved the best heavy metal rejection, with 95.97% (83.45 L/m2·h) for Pb2+ and 92.75% (87.78 L/m2·h) for Cu2+. For antifouling performance, the PMM-0.2 membrane exhibited the highest flux recovery at 97.85%, highlighting the beneficial effect of Ni-MOF@MGO incorporation on membrane stability and resistance to fouling.

These results indicate that incorporating NiMOF@MGO into the PSF membrane enhances its separation efficiency, antifouling behavior, and degradation performance, making it well-suited for industrial wastewater treatment and heavy metal removal applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., A.J. and G.J.; methodology, J.H. and A.J.; validation, A.B., H.S. and A.P.; formal analysis, J.H. and G.J.; investigation, J.H., A.J., A.B., H.S., A.P. and G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, H.S., A.P. and G.J.; visualization, J.H., A.J. and A.B.; supervision, G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant No. S-PD-24-28 from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMM | Mixed Matrix Membrane |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Frameworks |

| PSf | Polysulfone |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscope |

| CAG | Contact Angle Goniometer |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| VSM | Vibrating Sample Magnetometer |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| FRR | Flux Recovery Ratio |

| TFR | Total Fouling Ratio |

| RFR | Reversible Fouling Ratio |

| IFR | Irreversible Fouling Ratio |

| Ra | Average Surface Roughness |

References

- Eke, J.; Yusuf, A.; Giwa, A.; Sodiq, A. The global status of desalination: An assessment of current desalination technologies, plants and capacity. Desalination 2020, 495, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, K.Y. Characteristics of heavy metal separation and determination of limiting current density in a pilot-scale electrodialysis process for plating wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Karim, Z.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Jamil, A.; Said, K.A.M.; Ali, A. Tuneable molecular selective boron nitride nanosheet ultrafiltration lamellar membrane for dye exclusion to remediate the environment. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.B.; Iftekhar, S.; Maqbool, T.; Pramanik, B.K.; Tabraiz, S.; Sillanpää, M.; Zhang, Z. Two-dimensional nanoporous and lamellar membranes for water purification: Reality or a myth? Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 432, 134335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, K.; Karunakaran, G.; Yadav, S.; Padaki, M.; Zadorozhnyy, V.; Pai, R.K. Al-Ti2O6 a mixed metal oxide based composite membrane: A unique membrane for removal of heavy metals. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 348, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-W.; Sun, T.-J.; Hu, J.-L.; Wang, S.-D. Composites of metal–organic frameworks and carbon-based materials: Preparations, functionalities and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3584–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, Y.; Wang, H. Recent advances in polymer and polymer composite membranes for reverse and forward osmosis processes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 16, 104–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, T.S.; Mansor, E.S.; Abdallah, H.; Shaban, A.M.; Souaya, E.R. Novel anti-fouling mixed matrix CeO2/Ce7O12 nanofiltration membranes for heavy metal uptake. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3273–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Chowdhury, H.; Miskat, M.I.; Rahman, M.S.; Hossain, N. Membrane-based technologies for industrial wastewater treatment and resource recovery. In Membrane-Based Hybrid Processes for Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, P.; Modak, S.; Ray, S.; Adupa, V.; Reddy, K.A.; Karan, S. Fast water transport through sub-5 nm polyamide nanofilms: The new upper-bound of the permeance–selectivity trade-off in nanofiltration. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 20714–20724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Qiao, S. Hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks: Design, applications, and prospects. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 3680–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.H.; Oh, P.C.; Mukhtar, H.; Jamil, A. Fabrication of NH2-MIL-125(Ti)/polyvinylidene fluoride hollow fiber mixed matrix membranes for removal of environmentally hazardous CO2 gas. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 107, 104794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, H.-L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, R.-S.; Lin, J.-M. Recent advances in graphene-based magnetic composites for magnetic solid-phase extraction. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 102, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; He, Y.; Lei, Z.; Gao, C.; Xie, Q.; Tong, P.; Lin, Z. Preparation of core–shell structured magnetic covalent organic framework nanocomposites for magnetic solid-phase extraction of bisphenols from human serum sample. Talanta 2018, 181, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M.; Shahlaei, M.; Yamini, Y.; Shakorian, M.; Arkan, E. Magnetic framework composite as sorbent for magnetic solid-phase extraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography for simultaneous extraction and determination of tricyclic antidepressants. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1034, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif, B.; Wang, C.; Chuan, D.; Shuang, S. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4 coated on APTES as carriers for morin-anticancer drug. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 6, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dief, A.M.; Hamdan, S.K. Functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and their application in water purification. Am. J. Nanosci. 2016, 2, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Ma, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, C.; Teng, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Shen, L. A novel flower-like nickel-metal-organic framework (Ni-MOF) membrane for efficient multi-component pollutants removal by gravity. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Vikrant, K.; Kim, K.H.; Kumar, V.; Kailasa, S.K. Critical role of water stability in metal–organic frameworks and advanced modification strategies for the extension of their applicability. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 1319–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, G.; Mohan, S.; Balakrishna, R.G. Engineering Ni-MOF/g-C3N4 Composite-Infused Polysulfone Membranes with Optimal Rejection, Flux, Antifouling, and Photocatalytic Properties for Wastewater Treatment. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 4454–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, S.I.; Shah, S.S.; Helal, A.; Aziz, M.A.; Yoo, D.Y. Unveiling the limitless potential: Exploring metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)/MXene based construction materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, M.; Hao, Y. High efficient removal of Pb(II) by amino-functionalized Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 191, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmah, A.; Taufiq, A.; Hidayat, A. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4/SiO2 nanocomposites. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 276, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.T.; LaChance, A.M.; Zeng, S.; Liu, B.; Sun, L. Synthesis, properties, and applications of graphene oxide/reduced graphene oxide and their nanocomposites. Nano Mater. Sci. 2019, 1, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.N.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, L. Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO) by modified Hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene 2017, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.-Y.; Wang, G.; Yan, X.-P. MOF-5 metal–organic framework as sorbent for in-field sampling and preconcentration in combination with thermal desorption GC/MS for determination of atmospheric formaldehyde. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asempour, F.; Emadzadeh, D.; Matsuura, T.; Kruczek, B. Synthesis and characterization of novel cellulose nanocrystals-based thin film nanocomposite membranes for reverse osmosis applications. Desalination 2018, 439, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, F.; Emadzadeh, D.; Dubé, M.A.; Kruczek, B. Modifying cellulose nanocrystal dispersibility to address the permeability/selectivity trade-off of thin-film nanocomposite reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination 2022, 538, 115900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, B.; Li, D.; Yao, J. Enhancing TFC membrane permeability by incorporating single-layer MSN into polyamide rejection layer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 509, 145397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, A.; Jahanshahi, M.; Mollahosseini, A.; Rajaeian, B. Structural and performance properties of UV-assisted TiO2 deposited nanocomposite PVDF/SPES membranes. Desalination 2012, 285, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.A.A.; Alam, J.; Shukla, A.K.; Alhoshan, M.; Ansari, M.A.; Al-Masry, W.A.; Rehman, S.; Alam, M. Evaluation of antibacterial and antifouling properties of silver-loaded GO polysulfone nanocomposite membrane against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and BSA protein. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 140, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surekha, G.; Krishnaiah, K.V.; Ravi, N.; Suvarna, R.P. FTIR, Raman and XRD analysis of graphene oxide films prepared by modified Hummers method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1495, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanathan, T.; Prasad, K.; Ostrikov, K.; Saravanan, A.; Mohana Krishna, V. Graphene oxide synthesis from agro waste. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoratne, C.; Rosa, S.; Kottegoda, I. XRD-HTA, UV visible, FTIR and SEM interpretation of reduced graphene oxide synthesized from high purity vein graphite. Mater. Sci. Res. India 2017, 14, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, S.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Asghari, M. A novel fabrication of a high performance SiO2–graphene oxide (GO) nanohybrid: Characterization of thermal properties of epoxy nanocomposites filled with SiO2–GO nanohybrids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 493, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaee, M.; Sheikhshoaie, I. Synthesis of CoFe2O4@ZnMOF/Graphene nanoflake for photocatalytic degradation of diazinon under visible light irradiation: Optimization and modeling using a fractional factorial method. 2022; unpublished/preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-L.; Shi, Y.; Zhong, S.; Lin, H.; Chen, J.-R. Facile synthesis of Fe3O4–graphene@mesoporous SiO2 nanocomposites for efficient removal of Methylene Blue. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 378, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterary, S.S.; AlKhamees, A. Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructure. Green Process Synth. 2021, 10, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Indrea, E.; Cretu, C. Assessing Fe3O4 nanoparticle size by DLS, XRD and AFM. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2012, 14, 460. [Google Scholar]

- Chaki, S.; Malek, T.J.; Chaudhary, M.; Tailor, J.; Deshpande, M. Magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesis by wet chemical reduction and their characterization. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfadji, A.; Bennabi, L.; Giannakis, S.; Marrani, A.G.; Bellucci, S. Sono-synthesis and characterization of next-generation antimicrobial ZnO/TiO2 and Fe3O4/TiO2 bi-nanocomposites for antibacterial and antifungal applications. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 39097–39108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Rajesh, Y.; More, M. Synthesis and characterization of SiO2 nanoparticles via sol–gel method for industrial applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 3575–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Rohmawati, L.; Faaizatunnisa, N.; Taufiq, A. The effect of silica mass ratio on pore structure and magnetic characteristics of Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanoparticles. Sci. Iran. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi Malekshah, R.; Fahimirad, B.; Khaleghian, A. Synthesis, characterization, biomedical application, molecular dynamic simulation and molecular docking of Schiff base complex of Cu(II) supported on Fe3O4/SiO2/APTS. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 2583–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheripour, E.; Moghadassi, A.; Parvizian, F.; Hosseini, S.; Van der Bruggen, B. Tailoring the separation performance and fouling reduction of PES based nanofiltration membrane by using a PVA/Fe3O4 coating layer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 144, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Rahbari-Sisakht, M.; Mansourizadeh, A. Anti-fouling polysulfone–graphene oxide ultrafiltration membrane with high capability in water/oil emulsion separation. J. Clust. Sci. 2024, 35, 2787–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.T.; Pham, T.D.; Verheyen, D.; Nguyen, M.K.; Pham, T.T.; Zhu, J.; Van der Bruggen, B. Fabrication of thin film nanocomposite nanofiltration membrane incorporated with cellulose nanocrystals for removal of Cu(II) and Pb(II). Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 228, 115998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zou, Q.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L. Effects of GO and MOF@GO on the permeation and antifouling properties of cellulose acetate ultrafiltration membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 569, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, L.; Shan, B.; Xie, C.; Liu, C.; Cui, F.; Li, G. Preparation and characterization of SLS–CNT/PES ultrafiltration membrane with antifouling and antibacterial properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Kashkouli, Y.; Rahbari-Sisakht, M.; Ghadam, A.G.J. Thin film nanocomposite nanofiltration membrane incorporated with cellulose nanocrystals with superior anti-organic fouling affinity. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Biswas, P.; Fortner, J.D. Graphene oxides as nanofillers in polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes: Shape matters. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 581, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadipour, A.; Shakiba, M.; Bozorg, A.; Foroozandeh, A.; Pahnavar, Z.; Abdouss, M. Benzenesulfonamide-functionalized electrospun polysulfone as an antibacterial support layer of thin-film composite pressure-retarded osmosis membrane: Fabrication and performance evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, M.; Pei, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, F.; Dlamini, D.S.; Cui, Z.; He, B.; Li, J.; Matsuyama, H. Improved water permeability and structural stability in a polysulfone-grafted graphene oxide composite membrane used for dye separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 595, 117547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Pei, H.; Pei, Y.; Li, T.; Li, J.; He, B.; Cheng, Y.; Cui, Z.; Guo, D.; Cui, J. Preparation and characterization of polysulfone-graft-4′-aminobenzo-15-crown-5-ether for lithium isotope separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 3473–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtan, U.; Baykal, A. Fabrication and characterization of Fe3O4@APTES@PAMAM–Ag highly active and recyclable magnetic nanocatalyst: Catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 60, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.F.S.; da Silva Neto, O.C.; Dias, T.G.; Reis, A.S.; Pedrochi, F.; Steimacher, A.; Barboza, M.J. The role of MgO on physical and bioactive properties of borophosphate glasses for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 17532–17543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Ingole, P.G. Development of polymer-based new high performance thin-film nanocomposite nanofiltration membranes by vapor phase interfacial polymerization for the removal of heavy metal ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Peng, N.; Li, J.; Zhao, F. Performance enhancement of polyvinyl chloride ultrafiltration membrane modified with graphene oxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 480, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yu, Y.; Qu, J.; Hu, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Q. Flexible, durable, and anti-fouling nanocellulose-based membrane functionalized by block copolymer with ultra-high flux and efficiency for oil-in-water emulsions separation. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 5665–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaedi, A.M.; Panahimehr, M.; Nejad, A.R.S.; Hosseini, S.J.; Vafaei, A.; Baneshi, M.M. Factorial experimental design for the optimization of highly selective adsorption removal of lead and copper ions using metal–organic framework MOF-2 (Cd). J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 272, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, N.; Azizian, S. Adsorption of copper ion from aqueous solution by nanoporous MOF-5: A kinetic and equilibrium study. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 206, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, H.A.; Ahmad, M.B.; Hussein, M.Z.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Musa, A.; Saleh, T.A. Nanocomposite of ZnO with montmorillonite for removal of lead and copper ions from aqueous solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 109, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Kong, X.; Wang, S.; Xiang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. Removal of heavy metals from electroplating wastewater by thin-film composite nanofiltration hollow-fiber membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 17583–17590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, P.; Smits, O.R.; Pyykkö, P. The periodic table and the physics that drives it. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.C.; Isloor, A.M.; Lakshmi, B.; Marwani, H.M.; Khan, I. Polyphenylsulfone/multiwalled carbon nanotubes mixed ultrafiltration membranes: Fabrication, characterization and removal of heavy metals Pb2+, Hg2+, and Cd2+ from aqueous solutions. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 4661–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, D.; Lau, W.; Rahbari-Sisakht, M.; Daneshfar, A.; Ghanbari, M.; Mayahi, A.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A. A novel thin film nanocomposite reverse osmosis membrane with superior anti-organic fouling affinity for water desalination. Desalination 2015, 368, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, R.S.; Keenan, R.J. The mechanisms of integral membrane protein biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.