Abstract

Mono-material multilayer polypropylene films were developed as light barrier structures through the incorporation of mineral-filled composite layers. Trilayer films with different layer arrangements were fabricated by thermocompression from polypropylene-based films containing 0, 1 and 5 wt.% of talc and kaolinite. A monolayer polypropylene film of equivalent total thickness was used as a control. Structural, thermal, mechanical, optical, and gas barrier properties were evaluated for all films fabricated. A well-defined trilayer structure was confirmed by SEM. FTIR analysis demonstrated negligible thermo-oxidation, with no thermal-degradation during processing. Improved thermal stability and a slight modification in crystallinity were evidenced by TGA and DSC, respectively. XRD revealed the predominance of the α-form crystalline phase and a preferential polymer crystal orientation associated with the particle presence. Regarding mechanical behavior, enhanced stiffness and tensile strength without loss of sealability or puncture resistance were observed. Trilayer films exhibited significantly reduced UV and visible light transmittance, while maintaining adequate translucency, making them suitable for photosensitive packaging applications. Gas permeabilities remained nearly unchanged, confirming that the barrier performances were preserved. Overall, these mono-material multilayer composites films offer a promising and recyclable alternative to conventional multi-material light barrier packaging, combining improved UV protection, mechanical robustness, and environmental compatibility.

1. Introduction

Packaging plays a key role in preserving product quality and extending shelf-life, particularly for those sensitive to light (UV and visible), oxygen, temperature, and humidity [1,2,3]. Light exposure, in the presence of oxygen, accelerates lipid photooxidation, leads to nutrient loss and deterioration of sensory attributes [4,5]. Therefore, selecting appropriate packaging materials is crucial, as they must fulfill the specific needs required by the product. Consequently, high barrier films have attracted significant interest in both research and industry, particularly for photosensitive products, as these alternatives offer enhanced product preservation [6,7].

Polyolefins such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), along with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polystyrene (PS), are widely used in packaging due to their ease of processing, lightweight, cost-effectiveness, and transparency [8,9]. However, monolayer polymer films can hardly provide all the properties required to protect and preserve photosensitive products. In multilayer systems, the final performance strongly depends on the processing method and the ability to control key variables that govern interlayer adhesion, polymer–polymer compatibility, as well as on the contribution of each layer to the overall structure. Such aspects are closely linked to the selected polymers, their physicochemical interactions, and the production scale [10]. Hence, the packaging industry often uses multilayer multi-material polymer films manufactured through conventional technologies, including coextrusion, lamination, and coating [10], to ensure the required high barrier properties for effective product preservation [11]. These technologies can be employed to combine different materials, such as aluminum or cardboard, requiring in certain cases the addition of a thin adhesive layer to ensure proper adhesion between the layers [12]. Specific requirements may depend on the packed product, and typically include gas and light barrier performance, as well as proper sealing. Gas barrier properties are particularly critical in food packaging, as they limit oxidation, control the internal atmosphere, and slow down ripening and spoilage processes. Key gases include oxygen, carbon dioxide and ethylene due to their direct role in oxidative degradation, microbial inhibition in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), and fruit ripening, respectively [13,14]. Additionally, good optical and mechanical properties are crucial for flexible packaging [6].

In order to improve the light barrier in multilayer films, aluminum is commonly incorporated by coating or lamination, as it blocks UV and visible light effectively. Similarly, a paper layer can be added to enhance light protection while simultaneously providing rigidity and improving printability. Another common strategy to increase light barrier and attract consumers, is printing colorful and attractive designs on the packaging [15]. Nevertheless, the combination of different materials, or the use of adhesives and inks are not sustainable solutions. Conventional recycling methods by reprocessing cannot be employed for these packaging materials [16]. Several alternative approaches have been explored, including delamination, dissolution–reprecipitation, and compatibilization techniques [17,18]. However, these methods remain economically unfeasible, leading to the frequent disposal of multilayer films through landfilling (increasing environment passive) or incineration [19].

Regulatory and market pressures have recently accelerated the transition toward sustainable packaging. For example, the European Union objective of fully recyclable multilayer packaging by 2030 underscores the urgent need for circular-design strategies [20]. That shifts the material selection toward simpler, more homogeneous structures, compatible with conventional mechanical recycling. Consequently, “design for recycling”, or eco-design, has become a central principle, guiding the development of functional packaging that can be easily reintegrated into the production cycle [21].

Within this context, mono-material multilayer films based on polymer composites offer a promising route to combine high barrier performance with improved end-of-life options. These structures employ the same polymer matrix (usually PE or PP) in all layers, while their functionality can be tailored by incorporating fillers in low loadings (below 5 wt.%) [15]. Particularly, mineral particles such as talc, kaolinite, mica and calcium carbonate can enhance mechanical, thermal and barrier properties, simultaneously reducing production costs [22,23]. These fillers influence the final mechanical performance in two main ways: (i) by acting directly as rigid particles with specific characteristics such as shape, size, and modulus; and (ii) by modifying the crystallization behavior of the polymer matrix and, consequently, the molecular structure of the semicrystalline polymer [24].

Specifically, in semicrystalline polymers like PP and PE, certain inorganic particles can act as nucleating agents, modifying crystallinity, as well as type and crystal size, and consequently influencing their barrier performance [25]. Moreover, laminar mineral fillers such as talc and kaolinite can scatter and/or absorb light, thereby limiting light transmission [26,27,28,29], and protecting the product against photooxidation when well distributed and dispersed [30]. Furthermore, these films can be easily adapted to modern industrial production technologies and due to their low particle content, they can be recycled by conventional reprocessing. Recent advances in mono-material multilayer films have primarily focused on enhancing gas barrier performance while ensuring compatibility with mechanical recycling. Most studies report on PE-based multilayer structures in which barrier improvements are achieved through the incorporation of functional additives into specific layers. For instance, Wang et al. [31] produced LDPE multilayers by blown film extrusion, with the incorporation of KMnO4, pumice and NaCl, resulting in enhanced oxygen barrier properties and ethylene-absorption capability. Other blown LDPE systems formulated with green tea extract have demonstrated simultaneous improvements in light, water vapor and oxygen barrier properties, along with antioxidant activity [32]. Other PE-based multilayer films, developed by thermocompression, combine an antimicrobial agent (S. cerevisiae) and activated carbon, or zeolite as carriers to provide protection against microbial spoilage [33].

In contrast, developments in PP-based mono-material films have mainly relied on the addition of thin inorganic coatings as barrier layers. For example, multilayer configurations incorporating AlOx as an internal barrier layer have shown substantial reductions in oxygen transmission rates [34,35]. Renoldi et al. [36] evaluated BOPP/PP structures containing an inorganic coating for semi-hard cheese packaging and reported improvements mainly in carbon dioxide retention. Overall, despite these advances, most reported efforts focus on oxygen-barrier improvement rather than light-shielding capabilities. Moreover, studies on PP-based mono-material multilayers incorporating mineral fillers remain limited, particularly those assessing a comprehensive analysis of optical, mechanical, and gas barrier properties. Such gap highlights the need for research exploring the potential of mineral-filled PP multilayers as recyclable light barrier materials.

The present work aims to develop mono-material multilayer films based on polypropylene composites acting as light barrier systems. Although industrial multilayer films are typically produced using the techniques mentioned above, thermocompression was selected in this study as a laboratory-scale method to isolate and evaluate the effects of layer configuration and particle incorporation on the barrier and mechanical properties [33,37,38]. The main objective is to analyze the influence of the presence of mineral particles (talc and kaolinite) and the multilayer configuration on the structural, mechanical, optical, and gas-barrier properties of the resulting films. Particular emphasis was devoted to the assessment of the potential of these films to combine effective UV and visible light protection with mechanical performance, contributing to the development of sustainable packaging materials for photo-sensitive products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Monolayer films based on a commercial homopolymer polypropylene (PP) (Petrocuyo 1102 H; with a melt flow index of 1.8 g/10 min at 230 °C/2.16 kg) provided by PetroCuyo (Ensenada, Argentina), were used to develop multilayer mono-material films. Composite monolayer films contain commercial mineral particles. Specifically, films contained talc (T), supplied by Dolomita SAIC (Alta Gracia, Argentina) with a median particle size (D50) of 6 µm and kaolinite (K), provided by Piedra Grande SAMICA (Avellaneda, Argentina) with a D50 of 4 µm. PP monolayer films exhibited a crystallinity degree of 42.1 ± 0.1%, whereas that of the composite monolayer films increased to 45.5 ± 0.5%.

2.2. Preparation of Films

Three-layer films were obtained by thermocompression of composite films prepared with different mineral particles (talc and kaolinite) and particle concentrations (0, 1 and 5 wt.%). Thermocompression conditions were 180 °C and 1.96 MPa pressure for 30 s; this was followed by cooling the obtained films under pressure. These parameters were selected based on preliminary tests, aimed at ensuring adequate interlayer adhesion while preventing thermo-oxidative degradation during processing. Different three-layer configurations with respect to the order of the composite films were fabricated, always having one of the outer layers as PP (the one supposed to be in contact with the packaged product). Three-layer films were named as PP/PP (particle type) (particle concentration)/PP (particle type) (particle concentration), e.g., PP/PPT5/PPT1. In addition, control films (PP monolayer) with an equivalent thickness of three-layer films, were prepared.

2.3. Film Characterization

2.3.1. Structural and Thermal Characterization

Control and trilayer film thickness were determined using a micrometer (Mitutoyo, Mitutoyo Corporation, Takatsu-ku, Kawasaki, Japan) at different locations. The presence of the trilayers were corroborated, on the cross-sectional area of films, by Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM) with a LEO EVO 40 XVP-EDS Oxford X-Max 50 (Carl Zeiss AG, Cambridge, UK). These studies were performed on several points of cryofractured films with a gold-coated surface, using an argon plasma sputter coater (PELCO 91000, Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA).

Thermal stability of control and trilayer films and their total particle concentration were evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a TGA 5500 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Samples were heated from 30 °C up to 700 °C at a constant rate of 10 °C/min in N2 atmosphere.

Possible thermo-oxidative degradation induced by processing was evaluated semi-quantitatively by the carbonyl index employing Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) in a Thermo Nicolet Nexus spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spectra were recorded directly on the films, in transmission mode over the range of 4000–400 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 10 accumulated scans. Carbonyl index is defined as the ratio of the area under the band assigned to this group (1700–1800 cm−1) and a PP reference band, which is not affected by thermal degradation (2720 cm−1) [39].

Control and trilayer films were also analyzed by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) using a TA Instruments Discovery DSC (Discovery DSC, New Castle, DE, USA). Heating scans were carried out from 30 °C to 200 °C at 10 °C/min under nitrogen atmosphere. Peak identification and area integration were performed using Trios software (v 4.1.1.33073, 2016). Bulk degree of crystallinity (xbc) of the polymer phase was calculated based on DSC data:

where is the melting enthalpy, m represents particle mass fraction and is the theoretical melting enthalpy of 100% crystalline PP (207.1 J/g) [40].

Films crystal structure was analyzed by X-ray Diffraction (XRD), in order to evaluate a possible crystal orientation due to particle presence. Diffractograms were obtained in a Philips PW1710 X-ray diffractometer (Philips, Almelo, The Netherlands), provided with a tube, a copper anode, and a detector operating at 45 kV and 30 mA with 2θ ranging from 3 to 60°. They were performed on both outer layers of each trilayer, as well as on the two external faces of control film.

2.3.2. Mechanical Properties

Tensile mechanical properties were assessed using a universal testing machine (Instron Model 3369, ITW company, Groton, MA, USA) equipped with a 1 kN load cell. Tests were performed at 23 °C with a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min until the samples fractured, in accordance with ASTM D882 [41]. Ten specimens from control layer and trilayer films were tested (five cut in one direction and five cut perpendicularly to it). From these tests, Young’s modulus (E), tensile strength (σu) and elongation at break (εb) were determined.

Thermo-sealing capacity tests were conducted following ASTM F88 [42] in the same universal testing machine. Five sealed specimens of control and trilayer films were prepared using an impulse-wire thermosealer making sure the inner PP layers were in contact during the sealing process.

Puncture resistance was evaluated using a hemispherical probe with a penetration rate of 25 mm/min under ASTM F1306 [43], testing five specimens from control and trilayer films, using a universal testing machine. For trilayer films, the inner PP layer was positioned facing the probe during the test.

2.3.3. Light Barrier Properties

The light barrier capacity of control and trilayer films was assessed by means of a T60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (TG Instruments, Earl Shilton, Leicestershire, UK), operating in transmittance mode over a wavelength range of 190–700 nm. Rectangular samples were cut and placed in a quartz cuvette (path length: 1 cm) for the analysis. For this purpose, transmittance values at 300 nm and 600 nm, corresponding to UV and visible regions, respectively, were specifically analyzed. In addition, haze (H %) in accordance with ASTM D1003 [44], whiteness index (WI) and yellowness index (YI) under ASTM E313 [45] and ASTM D1925 [46], respectively, were analyzed using a Hunter Lab UltraScan XE colorimeter (Hunter Associates Laboratory, Inc., Reston, Virginia, USA) and Universe software (v 4.10, Service pack 2, 2001).

2.3.4. Gas Barrier Properties

Gas barrier properties were evaluated using a static permeation apparatus, at 23 °C and 0% relative humidity, according to ASTM D1434 [47] (constant volume method). Circular film samples with a diameter of 25 mm were tested, and their thickness was measured at different locations. Pure gas permeability () to oxygen, carbon dioxide and ethylene of the control and trilayer films was determined. The measurements were performed maintaining a 0.2 MPa pressure difference across the film, and the molar flux through the sample was determined from the pressure increase in the calibrated downstream chamber, applying the ideal gas law:

where : molar density flux of component i, : partial pressure difference in component i at the two sides of the film, : film thickness, A: sample area exposed to gas, R: universal gas constant, T: absolute temperature, : downstream volume and : variation in downstream partial pressure of component i with time [48]. Permeability results are reported in the non-SI units Barrer (1 Barrer = 10−10 cm3 (STP cm/s cm2 cmHg)).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted in triplicate, unless otherwise specified, to ensure the reproducibility and reliability of the results. The mean values and standard deviations were calculated based on the experimental data obtained from the replicates. Statistical differences among the means were determined through a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which allows for assessing whether the variations observed among groups are statistically significant. When significant differences were detected (p ≤ 0.05), Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied to identify which specific means differed from each other. In the tabulated results, different lowercase letters are used to indicate statistically significant differences between groups: means sharing the same letter are not significantly different, while those with different letters differ at the 95% confidence level.

3. Results

3.1. Film Structural and Thermal Characterization

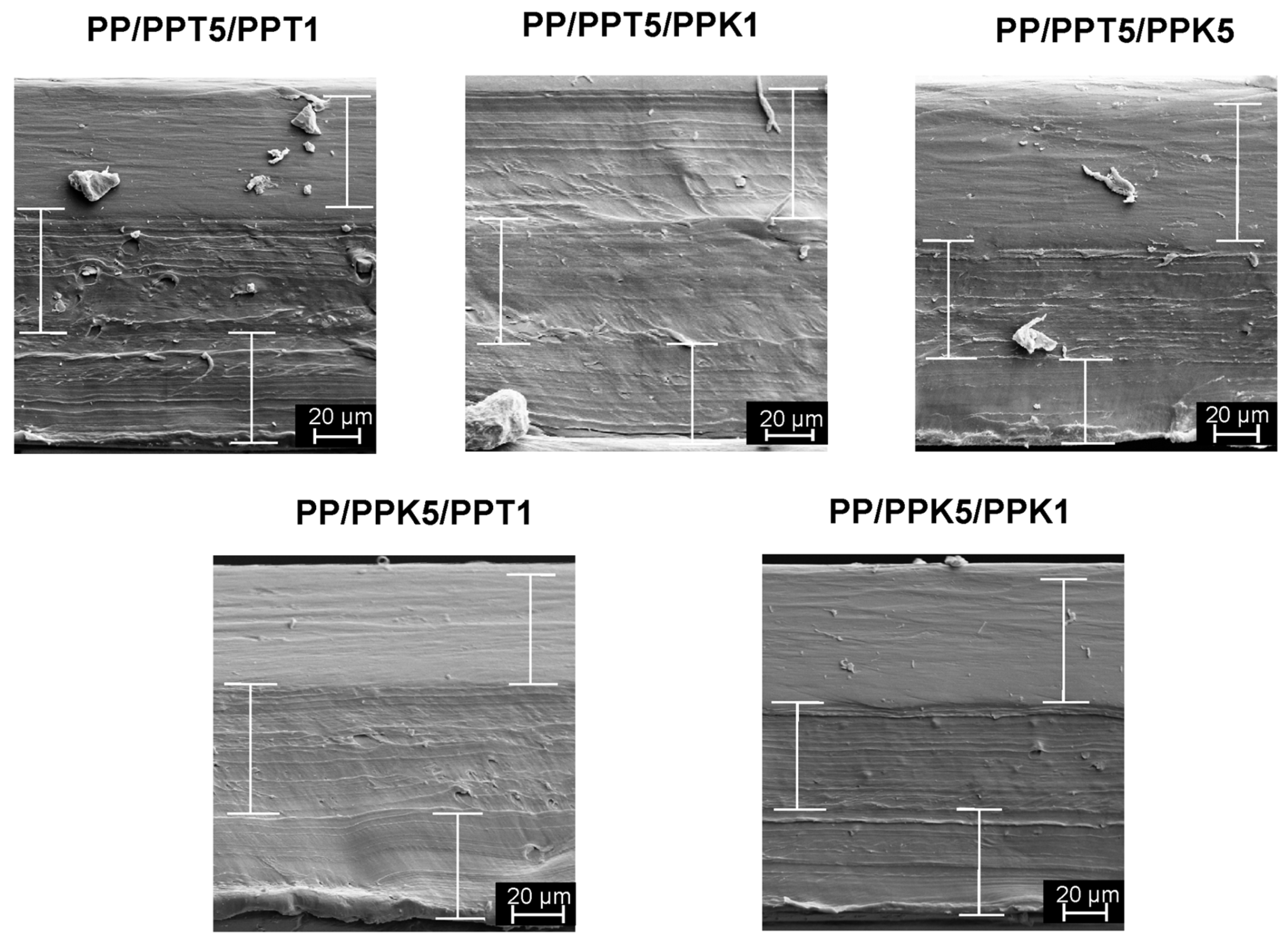

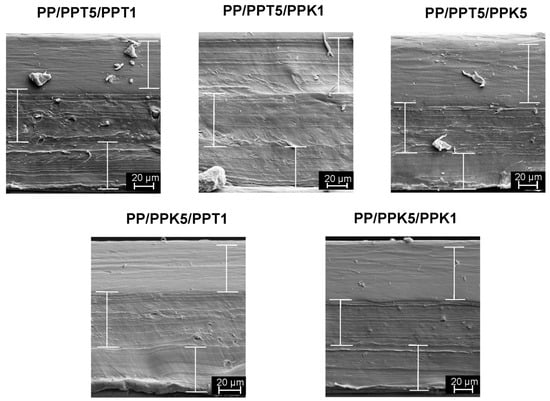

The obtained films, including control monolayer film, present a mean thickness of 150 ± 11 µm. The presence of the trilayers was confirmed by SEM analysis, inspecting the cross-sectional area of films. In this sense, Figure 1 presents the SEM micrographs of three-layer structure of films, indicating a good interlayer adhesion, with no holes or gap between layers. Relevantly, the bottom layer corresponds to PP. Additionally, mineral particles can be identified, mainly in those layers with 5 wt.% fillers. Some of these particles are evident even though they are covered by a thin polymer skin.

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs of trilayer films (1000×). The vertical bars indicate the thickness of the individual layers.

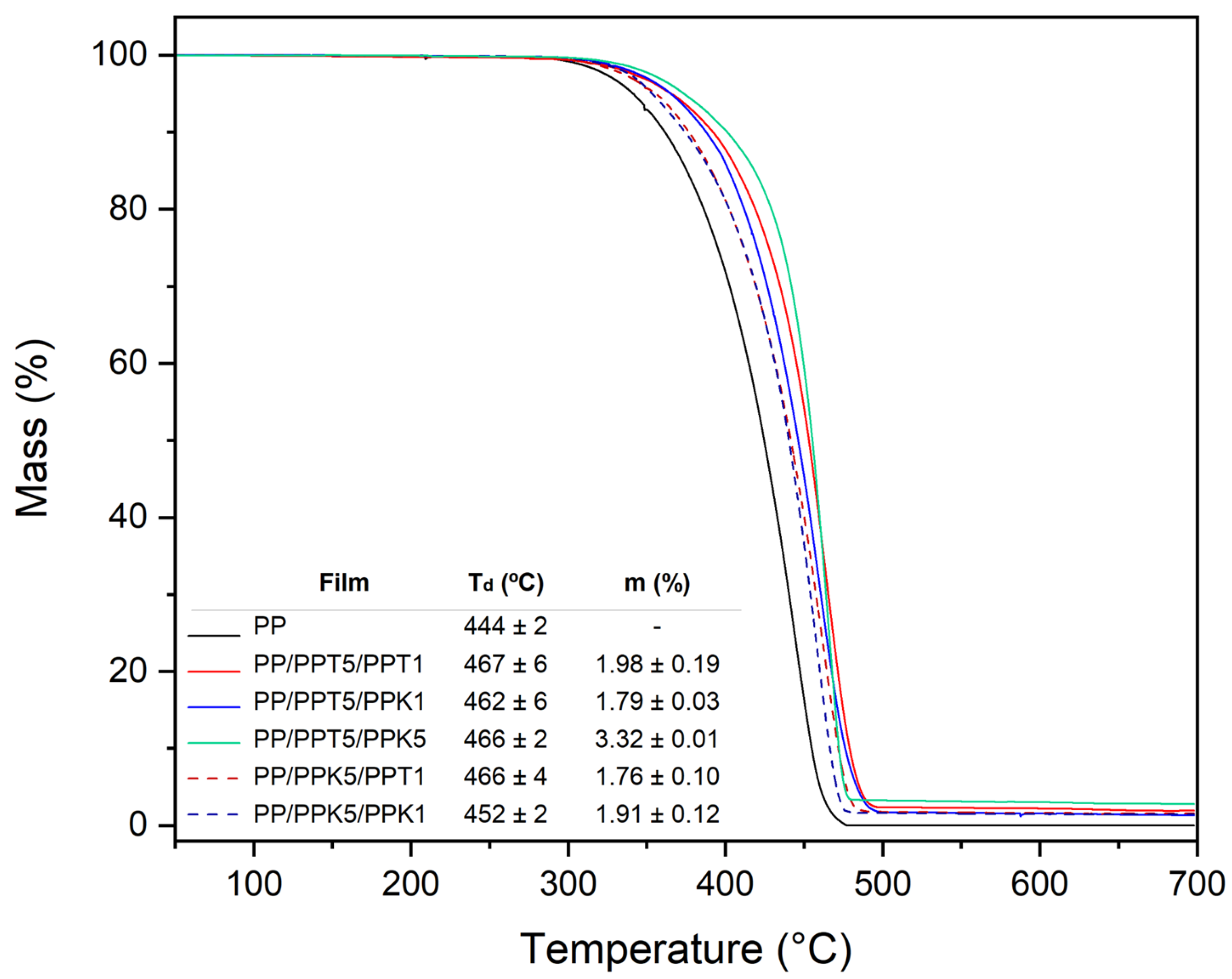

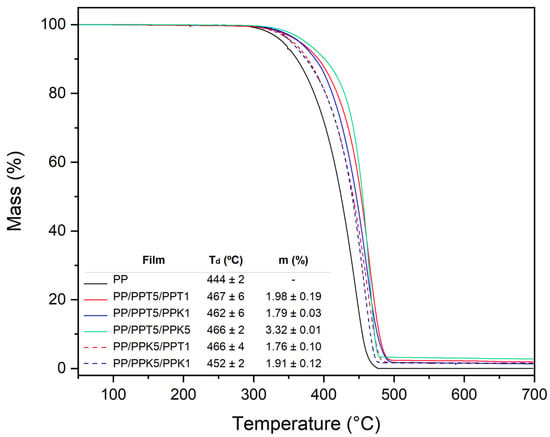

In order to determine total particle concentration and its influence on film thermal stability, Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis, TGA, was carried out. Figure 2 presents the dependence of the relative mass loss with temperature along with the decomposition temperature (Td). Specifically, Td values were determined from the maximum decomposition peak in the derivative curve of thermogravimetric data. The analysis reveals that multilayer films filled with talc (PPT5 layer) present higher thermal stability in comparison with the films filled with kaolin (PPK5 layer) or the neat polymer (control PP monolayer film). The presence of the composite layer (with talc), in the trilayer configuration increases PP decomposition temperature by at least 23 °C, indicating an enhanced thermal resistance. Such behavior has been widely reported [25,49,50], and it can be attributed to their pronounced delamination capability, which enhances the barrier effect by limiting the release of volatile degradation products and consequently delaying the decomposition process [51]. Moreover, total particle concentration in trilayer films was verified from these curves, considering residual mass (m %) values at the end of polymer matrix degradation (Figure 2, inset). The residual masses are in accordance with the nominal total particle concentration theoretically determined in trilayer configuration from layer proportion and its filler concentration.

Figure 2.

Mass percent versus temperature of control monolayer and trilayer films including degradation temperature values (Td) and total particle concentration (m %).

A qualitative assessment of possible thermo-oxidative degradation by film processing was carried out by FTIR spectroscopy. The presence of carbonyl groups, which may originate from the oxidation of tertiary carbons in the PP structure, serves as a reliable indicator of degradation. Therefore, the carbonyl index was calculated for all films, and reported in Table 1. These values are significantly lower than those reported by Salah et al. [52] and Espinosa et al. [53] for PP, suggesting negligible degradation levels.

Table 1.

Carbonyl Index for control monolayer and trilayer films.

Table 2 summarizes the bulk degree of crystallinity (Xbc) and melting temperature (Tm) obtained by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for control monolayer and trilayer polypropylene-based films. The control monolayer film exhibited the lowest Xbc value (47.0%), which slightly increased upon the multilayer configuration, reaching up to 49.0% for the PP/PPT5/PPK5 film. That suggests the multilayer structure with composite layers promotes a modest increase in the overall crystallinity of the system. In this regard, the overall crystallinity obtained for all multilayer films is higher than the one that would be expected from the simple combination of the individual layers. Such behavior can be attributed to a possible recrystallization induced by the processing conditions and the presence of particles in the multilayer film. It is noteworthy that films containing a higher proportion of talc exhibit a greater increase in such property, which can be ascribed to the strong nucleating effect of talc. These results are consistent with the obtained Tm values which ranged between 161 and 163 °C, with small but statistically significant differences among the formulations, indicating that the multilayer configuration and the presence of particles only slightly influence the crystalline phase stability. The observed trend is in good agreement with previous findings by Espinosa et al. [53] and Meziane et al. [54], who demonstrated that the inclusion of mineral fillers does not significantly affect Tm in PP-based composites. In addition, Leong et al. [55] analyzed this effect by evaluating the crystallization behavior of PP in the presence of kaolin and talc, confirming that these mineral particles promote the formation of crystalline nuclei during cooling, thus inducing crystallization at higher temperatures, even though the overall crystalline fraction remains unchanged.

Table 2.

Bulk crystallinity degree (Xbc) and melting temperature (Tm) obtained by DSC for control monolayer and trilayer films.

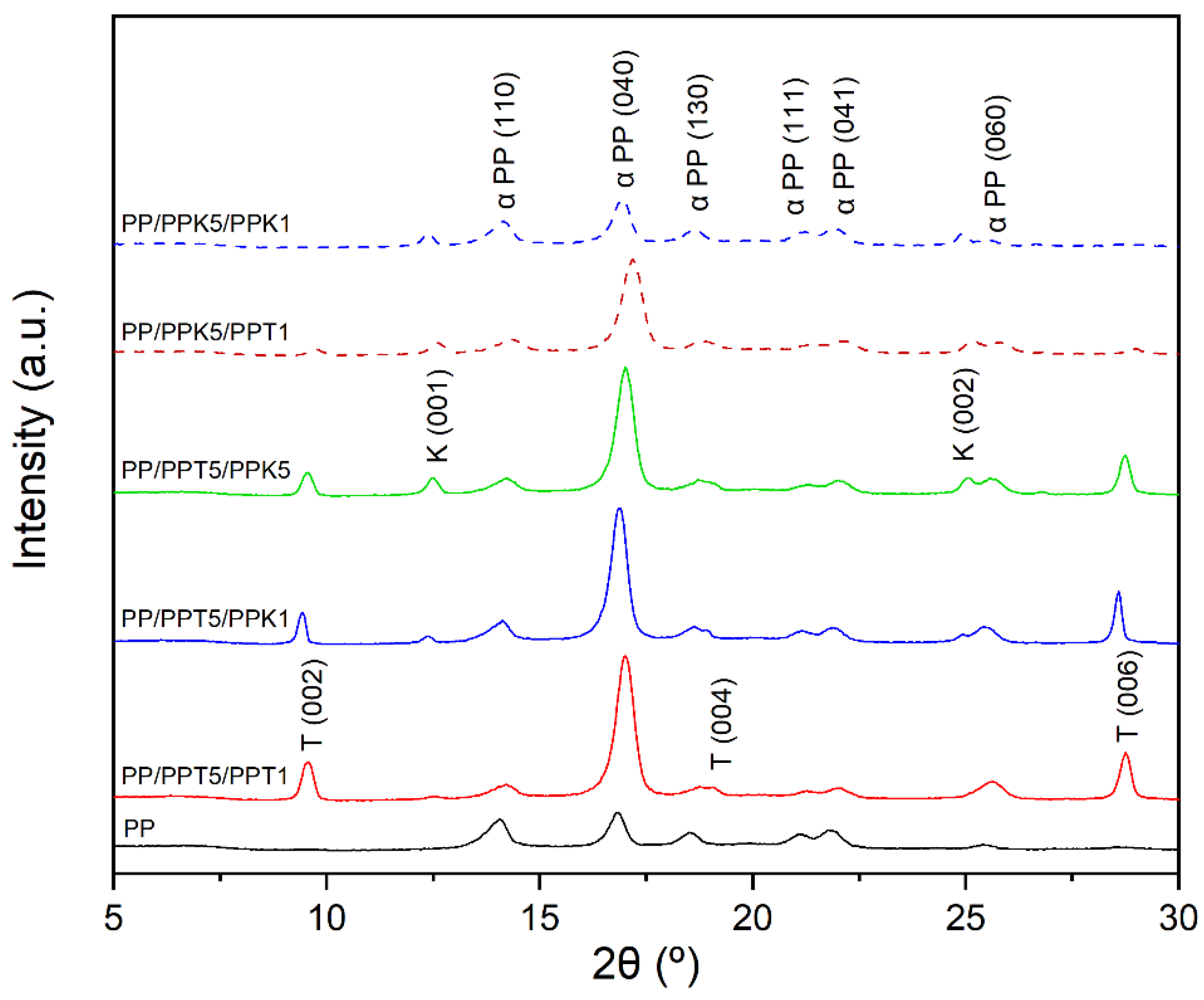

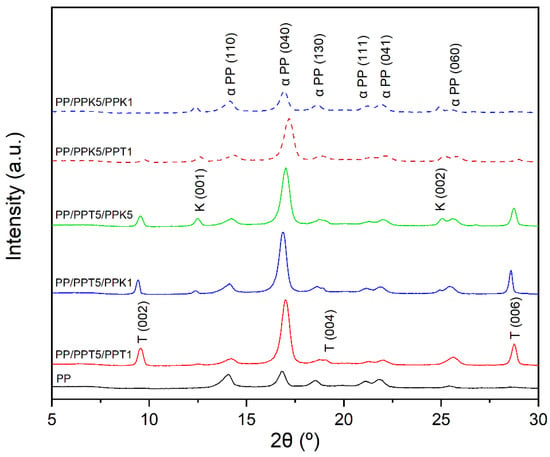

Polymer crystalline morphology is a key structural feature that strongly influences mechanical and barrier properties of composite films. In this sense, the relevant factors for composite films are the presence of filler, the loading, and particle morphology, as well as their orientation due to the monolayer processing. Particularly, in the case of laminar particles like talc and kaolinite, a macromolecular polymeric orientation is induced since particle surfaces offer active sites to crystal nucleation. Such behavior is observed in Figure 3, where diffractograms obtained by XRD are presented for all fabricated films. It is important to note that identical diffractograms were obtained regardless of which external surface of the films was exposed to the incident beam. Therefore, only one representative diffractogram per film is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

XRD spectra of control monolayer and trilayer films. Ref: T: talc, K: kaolinite, α PP: α crystal of polypropylene.

All diffractograms exhibit characteristic reflections of the stable monoclinic α-phase of PP associated with the (110), (040), (130), (111), (041), and (060) planes. The presence of talc is confirmed by its characteristic reflections at (002), (004), and (006) [56], while kaolinite is identified through its (001) and (002) planes [57]. Control monolayer film exhibited higher intensity in the (110) plane, while the (040) plane exhibited lower intensity compared to the trilayer films. The change in peak intensity suggests a preferential orientation of the b-axis of the PP crystals in (040) consistent with the alignment of laminar particles whose basal surfaces are parallel to the film surface. That can be attributed to monolayer processing and ulterior thermocompression to obtain multilayer configuration. The trend is more pronounced on trilayer films that contain a higher talc proportion in the formulation, in line with DSC results, indicating that the presence of talc particles could have a more pronounced nucleating effect than kaolinite [55].

3.2. Films’ Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties of packaging films are crucial to ensure product protection during transport and storage. To fulfill these requirements, films must exhibit adequate performance to withstand external forces and mechanical stress. In polymer composite films, mechanical properties are influenced not only by the intrinsic characteristics of the polymer matrix but also by the presence of fillers and their possible influence on crystallinity [58]. Table 3 presents the main mechanical properties of control monolayer and trilayer films.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of control monolayer and trilayer films.

Since films were obtained by thermocompression that contributes to obtaining a uniform film structure, mechanical properties measured for the two directions were similar. In addition, during mechanical tests, no separation was observed between layers at failure for trilayer films, corroborating the good adhesion between different layers.

Table 3 shows that the trilayer configuration and the presence of particles led to an increase in Young’s modulus (E) compared to the control monolayer film. Although the differences among trilayer formulations were not statistically significant, if mean values are considered, the effect of talc particles is more significant on E values (i.e., PP/PPT5/PPT1) than when only kaolinite particles (i.e., PP/PPK5/PPK1) are present in trilayer films. The behavior can be associated with multiple reinforcing mechanisms for which different factors have to be accounted for: first, the intrinsic rigidity of particles that contributes to mechanical reinforcement of the PP matrix (Etalc: 41.6 GPa [59] and Ekaolinite: 6–12 GPa [60]); additionally, the presence of mineral particles, mainly talc, which modify the crystalline structure, enhancing material stiffness. Thus, a partial replacement of PP by more rigid fillers also restricts the mobility and deformability of the matrix by the introduction of a mechanical restraint. These findings are consistent with previous studies that reported an increment in Young’s modulus in PP composites containing talc [55,61].

Regarding the tensile strength, it is observed that the trilayer films show an improved mechanical resistance compared to the control monolayer film. In particular, both elastic modulus and tensile strength are consistently higher for all trilayer configurations, indicating increased stiffness and an enhanced ability of the material to withstand applied stresses before failure. That indicates a good filler–matrix interaction, associated with the filler laminar morphology. Particles having this morphology and large aspect ratios allow a higher filler wettability by the matrix, avoiding the generation of microvoids between particles and matrix. The incorporation of mineral particles enhances the stiffness and load-bearing capacity of the films by promoting stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the rigid inorganic particles. Due to their laminar morphology, talc and kaolinite act as effective reinforcing agents that restrict the mobility of the PP chains and hinder plastic deformation under tensile load [55]. Moreover, the increment in σu values enhances further the interfacial adhesion between the layers.

Elongation at break values for all multilayer films were found to be all above 5%, indicating that none of the formulations experienced brittle fracture in the test conditions [62]. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in ductility were observed between control monolayer and composite trilayer configuration. Such decrease in elongation may be attributed to the increased stiffness imparted by the presence of particles, which restricts polymer chain mobility and introduces stress concentration points within the matrix. The behavior is consistent with the reported for polymer composites, where improvements in Young’s modulus are often accompanied by diminished elongation at break, particularly when rigid fillers are used [63].

Ensuring effective thermo-sealing is essential for multilayer films for packaging applications. In this study, all the composite films fabricated in this work demonstrated successful thermo-sealing capability, regardless of the type or concentration of mineral particles incorporated into the multilayer structure. Seal strength, defined as the maximum force required to separate two previously heat-sealed films, is the key parameter in evaluating packaging integrity. As shown in Table 3, no statistically significant differences were observed among the different formulations. The result is attributed to the fact that sealing occurred between the inner PP layers in all cases, confirming thus the quality of the three-layer structure. Consequently, appreciable variations in seal strength are not observed, even when mineral fillers are present in other layers. In terms of the failure mode, according to ASTM F88 standard, all specimens exhibited ductile failure, characterized by elongation followed by rupture within or near the sealed region indicating cohesive rather than adhesive failure, and further confirming effective sealing and a good adhesion between layers.

Puncture resistance is also critical for flexible packaging materials. In this sense, any loss of structural integrity can compromise barrier performance allowing the inflow or outflow of gases, moisture, or contaminants and consequently, shortening the shelf life of the product. In this study, puncture resistance was evaluated to assess the structural robustness of multilayer films and to examine the influence of mineral fillers and trilayer configuration on their ability to withstand localized mechanical stress. The results, presented in Table 3, show that puncture force values of trilayer films are comparable to those of the control monolayer film, with no statistically significant differences among the formulations (p > 0.05). That suggests the presence of talc and kaolinite at the studied concentrations, and the trilayer configuration did not affect the film resistance to puncture. The comparable performance across all samples indicates that filler incorporation, in the evaluated multilayer configurations, preserved the mechanical integrity of the films under localized deformation. Similar values were also expected, considering that, due to the processing, the particles are localized perpendicularly to the direction of the force during the puncture test. Thus, the contribution of mineral particles and trilayer configuration to puncture resistance was minimal under the applied test conditions. Moreover, no signs of interfacial delamination were observed after testing, confirming good adhesion between layers and the structural stability of the multilayer configuration.

3.3. Films Barrier Properties

3.3.1. Films’ Light Barrier Properties

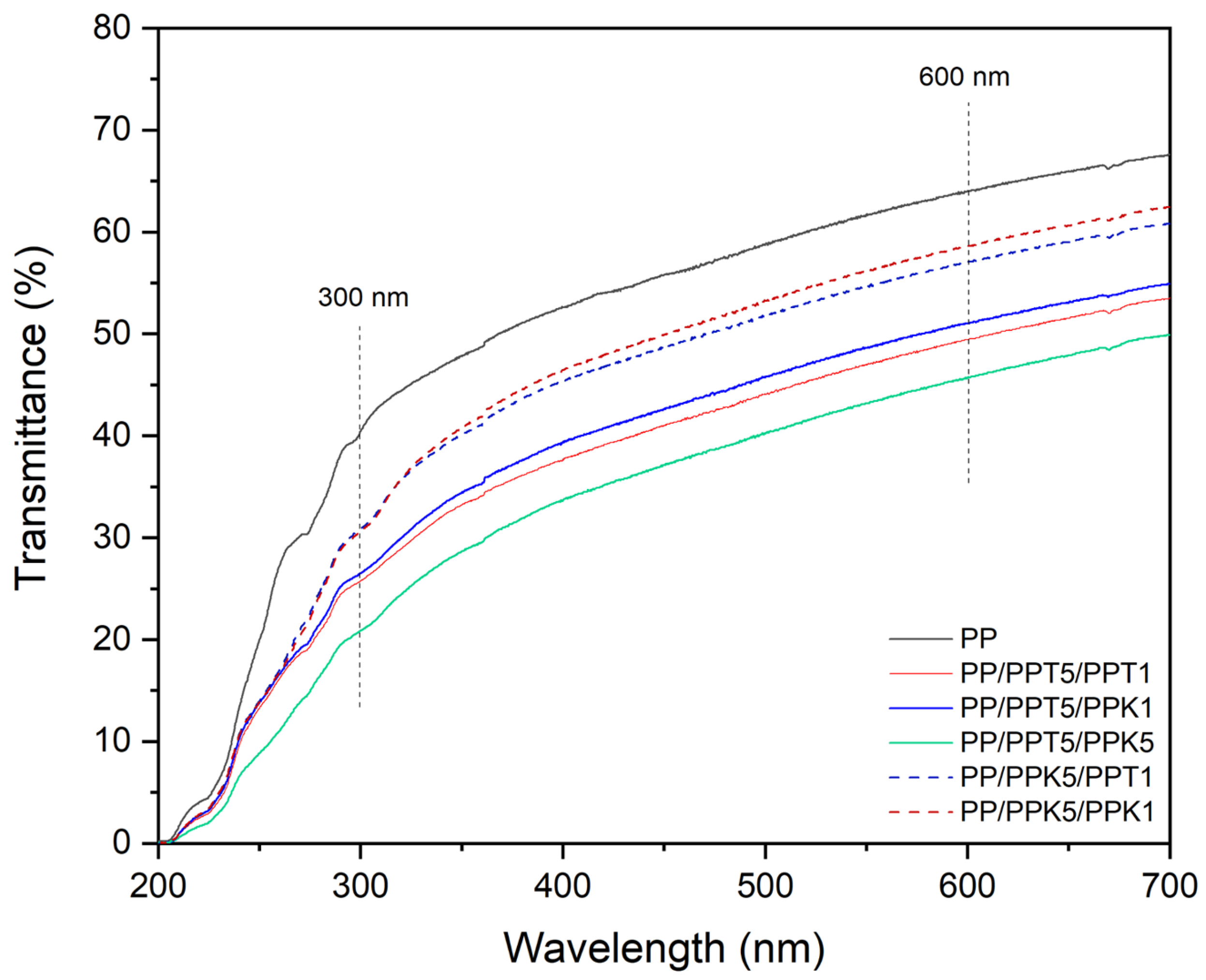

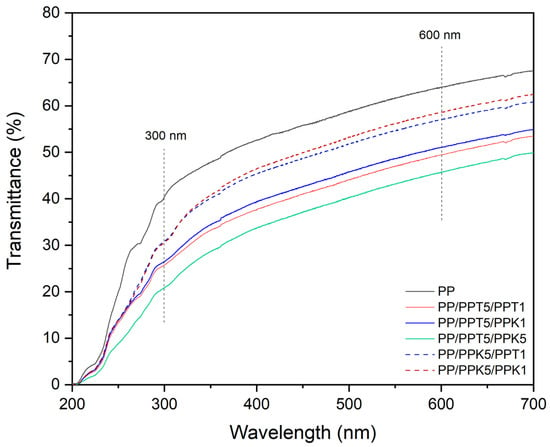

Light barrier properties are critical to reduce photo-oxidation and extending shelf-life of products, so the light transmittance of composite trilayer films at 300 nm in the UV range and 600 nm in the visible range was inspected. As shown in Figure 4, trilayer configuration containing mineral particles as fillers was more effective in enhancing light barrier performance. Regardless of the filler type, light barrier capacity increased with higher filler concentrations. Particularly, films containing a PPT5 layer further reduced light transmittance. The PP/PPT5/PPK5 formulation exhibited significant enhancement, reducing light transmittance by 31.2% at 600 nm (visible light) and a strong reduction by almost 50% at 300 nm (UV) with respect to control monolayer film. In this sense, mineral particles with laminar morphology, such as talc and kaolinite, can scatter and/or absorb light, preserving film translucency [26,27,28,29]. These fillers could also act as passive light barriers and modify polymer crystallinity during material processing, especially in semicrystalline polymers. The presence of crystals and mineral particles contributes to light scattering, creating a dual barrier effect. Such a synergistic mechanism and possible contribution of trilayer configuration significantly reduce light transmittance, enhancing light barrier properties of multilayer films [26].

Figure 4.

Transmittance spectra of control monolayer and trilayer films.

Notably, the developed trilayer composite films combine excellent UV-barrier properties with good translucency in the visible region. It proceeds from the transmittance obtained values for all films developed (control and trilayer films), ranging between 10% and 80% according to Guzmán-Puyol et al. [8]. Such a balance is highly advantageous for packaging applications: on the one hand, blocking UV radiation helps to prevent photo-oxidative degradation, on the other hand, maintaining translucency in the visible range preserves product visibility, a key attribute for consumer acceptance [64]. Consequently, the developed mono-material multilayer films represent a promising alternative for applications requiring both strong UV protection and visual appeal, without compromising recyclability.

To gain further insight into the visual appearance and light transmission behavior of the developed films, optical measurements were performed, including haze, whiteness index (WI), and yellowness index (YI). Such parameters provide valuable information on how light interacts with the polymer matrix and the incorporated fillers, influencing both the transparency and the perceived color of the films. Haze quantifies the degree of light scattering, thus indicating the level of translucency, while WI and YI describe the brightness and color tone of the samples, respectively. The evaluation of these properties is essential to understand the effect of mineral fillers and multilayer configurations on the appearance and functional optical performance of the materials. Table 4 summarizes the optical properties of control and multilayer films, including haze, WI, and YI. The monolayer PP film exhibited a haze value of 32.6%, indicating a partially translucency.

Table 4.

Optical properties of control and trilayer films.

The incorporation of mineral-filled layers led to a significant increase in haze, reaching values between 43.9% and 56.1%, depending on the layer configuration. In particular, the PP/PPT5/PPK1 and PP/PPT5/PPK5 films showed the highest haze values (52.6% and 56.1%, respectively), which can be attributed to enhanced light scattering caused by the presence of mineral particles and interfacial refractive index mismatches between layers. Correspondingly, the WI values decreased slightly with increasing haze, whereas YI exhibited a moderate rise, especially for the multilayer systems containing talc as filler, suggesting a subtle color shift toward a warmer tone.

3.3.2. Films’ Gas Barrier Properties

Understanding and optimizing gas permeation characteristics in multilayer films is essential for ensuring product protection and enhancing packaging performance. Gas permeability (P) in polymeric systems is governed by the solution–diffusion model [65]:

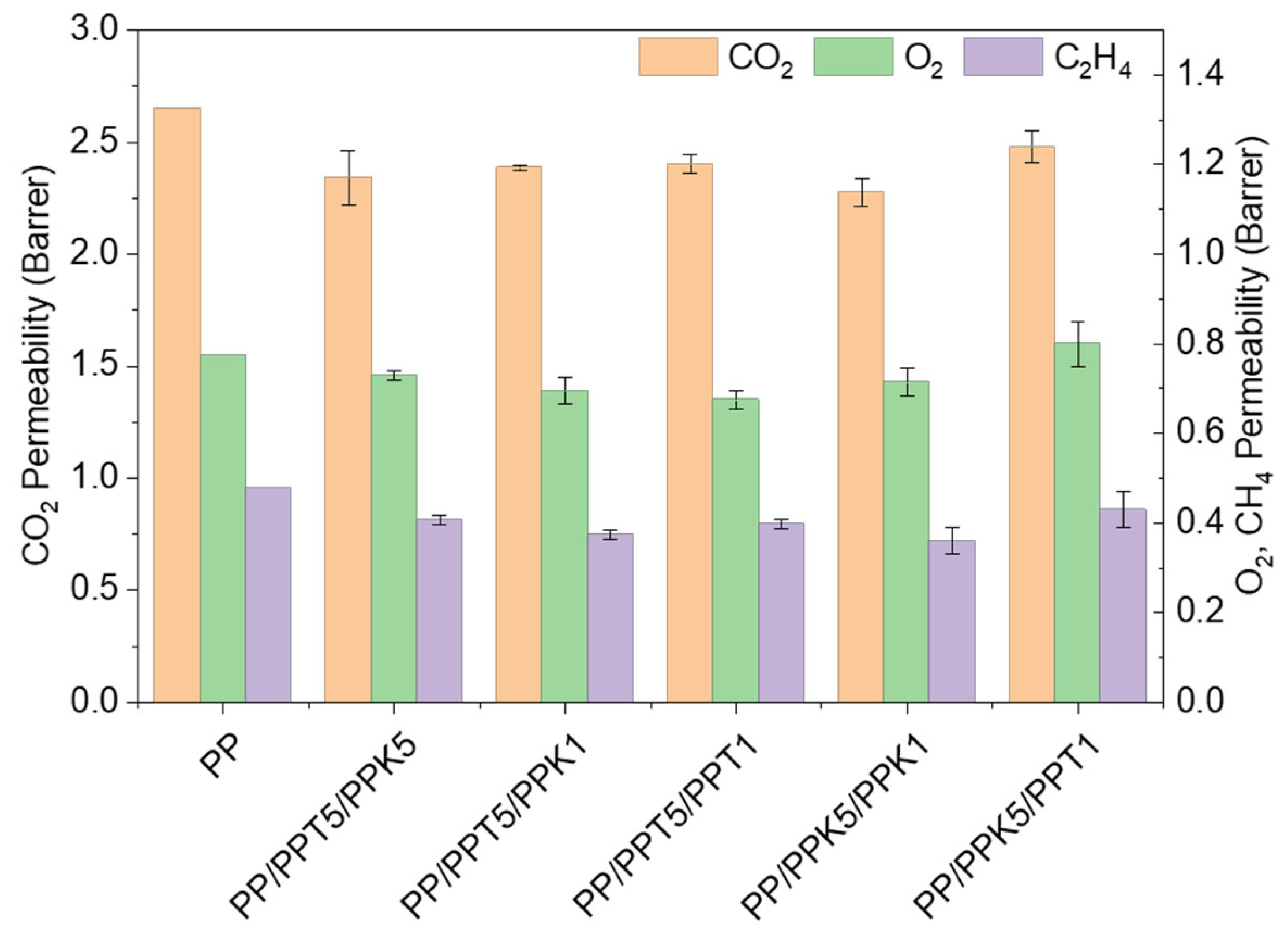

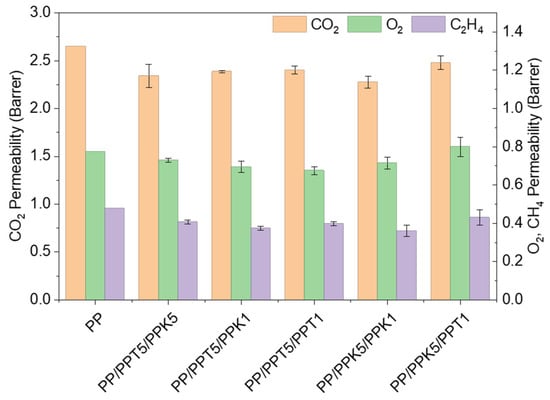

where D is the diffusivity and S is the solubility of the penetrant gas. The equation highlights how both kinetic and thermodynamic factors contribute to gas transport through the material. As shown in Figure 5, carbon dioxide (CO2) exhibited the highest permeability, followed by oxygen (O2) and ethylene (C2H4). Compared to the control film, PP-based trilayer films showed small but systematic reductions in permeability from 5% to 25%, where the largest variations were recorded for CO2 and C2H4, while O2 permeability remained nearly unchanged.

Figure 5.

CO2, O2 and C2H4 permeability (Barrer) at 23 °C in multilayer films.

Time-lag measurements of diffusivity revealed the following trend: (Table 5). This ordering correlates well with the molecular size of gases, if evaluated as molar volume at the critical point, O2 being the smallest and C2H4 the larger penetrant. As expected, CO2 and C2H4 exhibited higher solubility in the polymer phase due to their greater condensability and affinity for the non-polar polymer matrix, whereas O2 showed faster diffusion but lower solubility. Consequently, the observed permeability reflected the combined and gas-specific contribution of these two effects.

Table 5.

Diffusion and solubility coefficients for O2, CO2 and C2H4 in multilayer films.

The incorporation of talc and kaolinite as fillers within the polymeric matrix is expected to increase the tortuosity of the diffusive pathway, as these layered, plate-like particles act as impermeable obstacles, forcing gas molecules to take longer, more complex paths through the membrane. However, despite the large aspect ratio, low filler loading reduced the extent of this effect, leading to modest reductions in permeability, consistent with the small differences in the degree of crystallinity highlighted by the DSC analysis, upon the addition of fillers. Therefore, the multilayer configuration slightly enhanced the barrier performance of monolayer films while preserving their suitability for multilayer packaging applications.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Mono-material multilayer PP-based films containing talc- and kaolinite-filled layers were fabricated by thermocompression, achieving well-adhered structures without interfacial defects. The presence of mineral particles slightly modified polymer crystallinity and significantly enhanced thermal stability, particularly when talc was incorporated. The multilayer configuration contributed to improved stiffness and tensile strength while preserving sealability and puncture resistance, demonstrating the mechanical integrity of the system. Optical analysis revealed a notable reduction in UV and visible light transmittance together with increased haze, indicating that mineral fillers, such as talc and kaolinite, effectively enhanced light scattering and barrier performance. Gas permeability was preserved, revealing that the addition of fillers did not compromise gas barrier properties. Therefore, based on the obtained results, it is possible to state that the developed multilayer films combine an excellent light-blocking capacity and high mechanical robustness, positioning them as promising candidates for sustainable light barrier packaging applications. Future work should focus on the process optimization and scale-up of the fabricated mono-material multilayer films to enable their processing at an industrial level. In particular, the transition from thermocompression-based laboratory prototypes to continuous processes, such as melt compounding followed by blown-film coextrusion, would allow assessing the robustness of the materials under realistic manufacturing conditions. Optimization of key processing parameters, including melt temperature profile, die and barrel temperatures, shear rate, bubble stability, draw-down ratio, and cooling conditions, will be useful to ensure stable and consistent film barrier and mechanical properties during high-throughput production. Simultaneously, reprocessing trials could be carried out to evaluate property retention after multiple recycling cycles, thereby validating the circularity benefits associated with the mono-material design. Together, these research directions will support the large-scale implementation of these packaging materials, and for the assessment of the recyclability performance and long-term stability of the proposed multilayer structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; methodology, R.A.F., Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; validation, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; formal analysis, R.A.F., G.F. and R.D.C.; investigation, R.A.F., G.F. and R.D.C.; resources, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; data curation, R.A.F., G.F. and R.D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.F. and R.D.C.; writing—review and editing, G.F., Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; visualization, R.A.F.; supervision, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; project administration, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M.; funding acquisition, Y.N.A., L.A.C. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially funded by “Development of E. coli biosensors for Smart Packaging of meat products” Proyecto bilateral Ministero Degli Affari Esteri—MAECI (Italia)—SGCTeIP (Argentina) M03660. This work was also supported by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 3.1 “Fund for the realization of an integrated system of research and innovation infrastructures”-Call for tender No. 3264 of 28 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—PNRR IR0000020, Concession Decree No. 244 of 8 August 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP F53C22000560006, ECCSELLENT—Development of ECCSEL-R.I. Italian facilities: user access, services and long-term sustainability. This work was also funded by the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Project ECOSISTER, Mission 04 Component 2 Investment 1.5—NextGenerationEU, call for tender n. 3277 dated 30 December 2021 and award number: 0001052, dated 23 June 2022.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| MAP | Modified Atmosphere Packaging |

| wt.% | Weight Percent |

| KMnO4 | Potassium Permanganate |

| NaCl | Sodium Chloride |

| S. cerevisiae | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| AlOx | Aluminum Oxide |

| BOPP | Bioriented Polypropylene |

| T | Talc |

| K | Kaolinite |

| D50 | Particle size at the cumulative particle size distribution percentage of 50%. |

| SEM | Scanning Electronic Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| Xbc | Bulk Degree of Crystallinity |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| E | Elastic Modulus |

| σu | Tensile Strength |

| εb | Elongation at Break |

| H | Haze |

| WI | Whiteness index |

| YI | Yellowness index |

| Pi | Pure gas permeability |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| Td | Decomposition temperature |

| m % | Residual mass |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| C2H4 | Ethylene |

References

- Akter, M.; Islam, M.N.; Yasmin, S.; Mahomud, M.S. Development of an intelligent packaging material incorporating betacyanin from red beetroot extract into polyvinyl alcohol films. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, T.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, S.; Fang, C.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Qu, J.-P. Self-enhancement of food packaging film based on regulable microstructure evolution via circumfluent synergistic blow molding. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 47, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudir, M.; Ait Mesbah, Z.; Lerari, D.; Issad, N.; Djenane, D. Development of eco-friendly biocomposite films based on Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes powder blended with gum arabic and xanthan envisaging food packaging applications. Foods 2023, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerritore, M.; Olivieri, F.; Castaldo, R.; Avolio, R.; Cocca, M.; Errico, M.E.; Galdi, M.R.; Carfagna, C.; Gentile, G. Recyclable-by-design mono-material flexible packaging with high barrier properties realized through graphene hybrid coatings. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Jiménez, F.J.; Abellán-Dieguez, C.; Oliver-Simancas, R.; Rodríguez-García, A.M.; Alañón, M.E. Sustainable materials for novel food packaging based on alginate, methylcellulose and glycerol films functionalized with gallic acid. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-D.; Ren, P.-G.; Zhong, G.-J.; Olah, A.; Li, Z.-M.; Baer, E.; Zhu, L. Promising Strategies and New Opportunities for High Barrier Polymer Packaging Films. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 144, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viacava, G.E.; Ansorena, M.R.; Marcovich, N.E. Multilayered Films for Food Packaging. In Nanostructured Materials for Food Packaging Applications; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Puyol, S.; Benítez, J.J.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A. Transparency of polymeric food packaging materials. Food Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 111792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, S.; Trigo-López, M.; Arnaiz, A.; Miguel, Á.; Muñoz, A.; Mendía, A.; García, J.M. From classical to advanced use of polymers in food and beverage applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadowiec, D.; Matykiewicz, D.; Szostak, M.; Andrzejewski, J. Overview of the Cast Polyolefin Film Extrusion Technology for Multi-Layer Packaging Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, E.; Vargas, M.; Torres-Giner, S. Quality and shelf-life stability of pork meat fillets packaged in multilayer polylactide films. Foods 2022, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anukiruthika, T.; Sethupathy, P.; Wilson, A.; Kashampur, K.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Multilayer packaging: Advances in preparation techniques and emerging food applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1156–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, A.R.; Samarakoon, H.C.; Pranamornkith, T.; Bronlund, J.E. A Review of Ethylene Permeability of Films. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Meng, X.; Bhandari, B.; Fang, Z.; Chen, H. Recent Application of Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) in Fresh and Fresh-Cut Foods. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.-S.; Tacker, M.; Uysal-Unalan, I.; Cruz, R.M.S.; Varzakas, T.; Krauter, V. Recyclability and redesign challenges in multilayer flexible food packaging—A review. Foods 2021, 10, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Grau, L.; Auer, M.; Maletz, R.; Woidasky, J. Multilayer Packaging in a Circular Economy. Polymers 2022, 14, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Távora de Mello Soares, C.; Ek, M.; Östmark, E.; Gällstedt, M.; Karlsson, S. Recycling of multi-material multilayer plastic packaging: Current trends and future scenarios. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hissein, A.; Yousfi, M.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. Recycling of multilayer polymeric barrier films: An overview of recent pioneering works and main challenges. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2025, 310, 2400414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, G.; Li, J.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. A Journey from Processing to Recycling of Multilayer Waste Films: A Review of Main Challenges and Prospects. Polymers 2022, 14, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhan, S.; Zhou, M.; Xu, X.; You, F.; Zheng, H. A Powerful Strategy for Carbon Reduction: Recyclable Mono-Material Polyethylene Functional Film. Polymers 2024, 16, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, G.; Touil, I.; Masghouni, E.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. Multi-Micro/Nanolayer Films Based on Polyolefins: New Approaches from Eco-Design to Recycling. Polymers 2021, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Kumar, S.; Kona, B.; Houcke, D. Gas barrier properties of polymer/clay nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 63669–63690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, C.; Duraccio, D.; Cimmino, S. Food packaging based on polymer nanomaterials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1766–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S. Effect of kaolin on the mechanical properties of polypropylene/polyethylene composite material. Diyala J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 5, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajdek-Bieda, A.; Wróblewska, A. The Use of Natural Minerals as Reinforcements in Mineral-Reinforced Polymers: A Review of Current Developments and Prospects. Polymers 2024, 16, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, Y.N.; Castillo, L.A.; Barbosa, S.E. Nanocomposite flexible packaging to increase tomatoes shelf life without refrigeration. J. Packag. Technol. Res. 2022, 6, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.F.N.; Kamil, M.S.A.; Mahmud, S. Applied Nanoscience: Using Nano Zinc Oxide to Enhance Ultraviolet Protection of Commercial Talcum Powder. APEC Youth Sci. J. 2011, 3, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rabello, M.S.; White, J.R. Photodegradation of Talc-Filled Polypropylene. Polym. Compos. 1996, 17, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mouzahim, M.; Eddarai, E.M.; Eladaoui, S.; Guenbour, A.; Bellaouchou, A.; Zarrouk, A.; Boussen, R. Food packaging composite film based on chitosan, natural kaolinite clay, and Ficus carica leaves extract for fresh-cut apple slices preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Polymer nanocomposites for food packaging applications. In Functional and Physical Properties of Polymer Nanocomposites; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 30–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ajji, A. Development and application of low-density polyethylene-based multilayer film incorporating potassium permanganate and pumice for avocado preservation. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.M.; Andrade, M.A.; Vilarinho, F.; Sanches Silva, A.; Rodrigues, P.V.; Castro, M.C.R.; Machado, A.V. Mono and multilayer active films containing green tea to extend food shelf life. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotopoulou, I.; Stamatis, H.; Barkoula, N.-M. Exploitation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as an alternative microencapsulation strategy of thymol via β-glucan based matrix for the development of multilayer LDPE active packaging films—Comparison with zeolite- and activated carbon-based carriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; De Luca, L.; Basile, G.; Lambiase, G.; Romano, R.; Pizzolongo, F. A Recyclable Polypropylene Multilayer Film Maintaining the Quality and the Aroma of Coffee Pods during Their Shelf Life. Molecules 2024, 29, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, G.; De Luca, L.; Calabrese, M.; Esposito, M.; Sorrentino, G.; Romano, A.; Pizzolongo, F.; Lambiase, G.; Romano, R. Study of lipid oxidation and volatile component of roasted peanuts stored in high-barrier packaging. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, vvaf038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renoldi, N.; Calligaris, S.; Nicoli, M.C.; Marino, M.; Rossi, A.; Innocente, N. Effect of the shifting from multi-layer systems towards recyclable mono-material packaging solutions on the shelf-life of portioned semi-hard cheese. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 46, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Dicastillo, C.; Garrido, L.; Velásquez, E.; Rojas, A.; Gavara, R. Designing Biodegradable and Active Multilayer System by Assembling an Electrospun Polycaprolactone Mat Containing Quercetin and Nanocellulose between Polylactic Acid Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tampau, A.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Release kinetics and antimicrobial properties of carvacrol encapsulated in electrospun poly-(ε-caprolactone) nanofibres: Application in starch multilayer films. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Kong, M.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, G. Outdoor and accelerated laboratory weathering of polypropylene: A comparison and correlation study. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 112, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, B. Thermal Analysis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Method D882-00; Standard Test Methods for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Method F88/F88M-21; Standard Test Method for Seal Strength of Flexible Barrier Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Method F1306-21; Standard Test Method for Slow Rate Penetration Resistance of Flexible Barrier Films and Laminates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Method D1003-21; Standard Test Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Method E313-20; Standard Practice for Calculating Yellowness and Whiteness Indices from Instrumentally Measured Color Coordinates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Method D1925; Standard Test Method for Yellowness Index of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Method D1434-82; Standard Test Method for Determining Gas Permeability Characteristics of Plastic Film and Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Giacinti Baschetti, M.; Minelli, M. Test methods for the characterization of gas and vapor permeability in polymers for food packaging application: A review. Polym. Test. 2020, 89, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govorčin Bajsić, E.; Rek, V.; Ćosić, I. Preparation and Characterization of Talc Filled Thermoplastic Polyurethane/Polypropylene Blends. J. Polym. 2014, 2014, 289283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Rangari, V.; Mahfuz, H.; Jeelani, S.; Mallick, P.K. Experimental Study on Thermal and Mechanical Behavior of Polypropylene, Talc/Polypropylene and Polypropylene/Clay Nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 402, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Wang, M.; Hao, Y.; Guo, S. The effect of talc orientation and transcrystallization on mechanical properties and thermal stability of the polypropylene/talc composites. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 58, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hadj Salah, H.; Daly, H.; Denault, J.; Perrin, F. UV degradation of clay-reinforced polypropylene nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2016, 56, 24273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, K.R.; Castillo, L.A.; Barbosa, S.E. Blown nanocomposite films from polypropylene and talc. Influence of talc nanoparticles on biaxial properties. Mater. Des. 2016, 111, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziane, O.; Bensedira, A.; Guessoum, M.; Haddaoui, N. Polypropylene-modified kaolinite composites: Effect of chemical modification on mechanical, thermal and morphological properties. Rev. Sci. Fondam. Appl. 2016, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leong, Y.W.; Abu Bakar, M.B.; Ishak, Z.A.M.; Ariffin, A.; Pukanszky, B. Comparison of the mechanical properties and interfacial interactions between talc, kaolin, and calcium carbonate filled polypropylene composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 91, 3315–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCPDS Card No. 29-1493; Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards, Talc (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2). International Centre for Diffraction Data: Swarthmore, PA, USA, 1988.

- JCPDS Card No. 00-005-0143; Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards, Kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4). International Centre for Diffraction Data: Swarthmore, PA, USA, 1955.

- Castillo, L.A.; Barbosa, S.E. Comparative analysis of crystallization behavior induced by different mineral fillers in polypropylene nanocomposites. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2020, 10, 184798042092275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, E.; Holloway, J. Experimental determination of elastic properties of talc to 800 °C, 0.5 GPa; calculations of the effect on hydrated peridotite, and implications for cold subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2000, 183, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanorio, T.; Prasad, M.; Nur, A. Elastic properties of dry clay mineral aggregates, suspensions and sandstones. Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 155, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, O.; Bouaziz, Y.; Haddar, N.; Mnif, N. Talc as reinforcing filler in polypropylene compounds: Effect on morphology and mechanical properties. Polym. Sci. 2017, 3, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ouchiar, S.; Stoclet, G.; Cabaret, C.; Georges, E.; Smith, A.; Martias, C.; Addad, A.; Gloaguen, V. Comparison of the influence of talc and kaolinite as inorganic fillers on morphology, structure and thermomechanical properties of polylactide based composites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 116–117, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, R.; Alonso, Y.; Barbosa, S.; Castillo, L. Light barrier properties of flexible films. Adv. Mater. Sci. Res. 2023, 64, 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wijmans, J.G.; Baker, R.W. The solution–diffusion model: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 107, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).