3.1. Balsa Transparent Wood

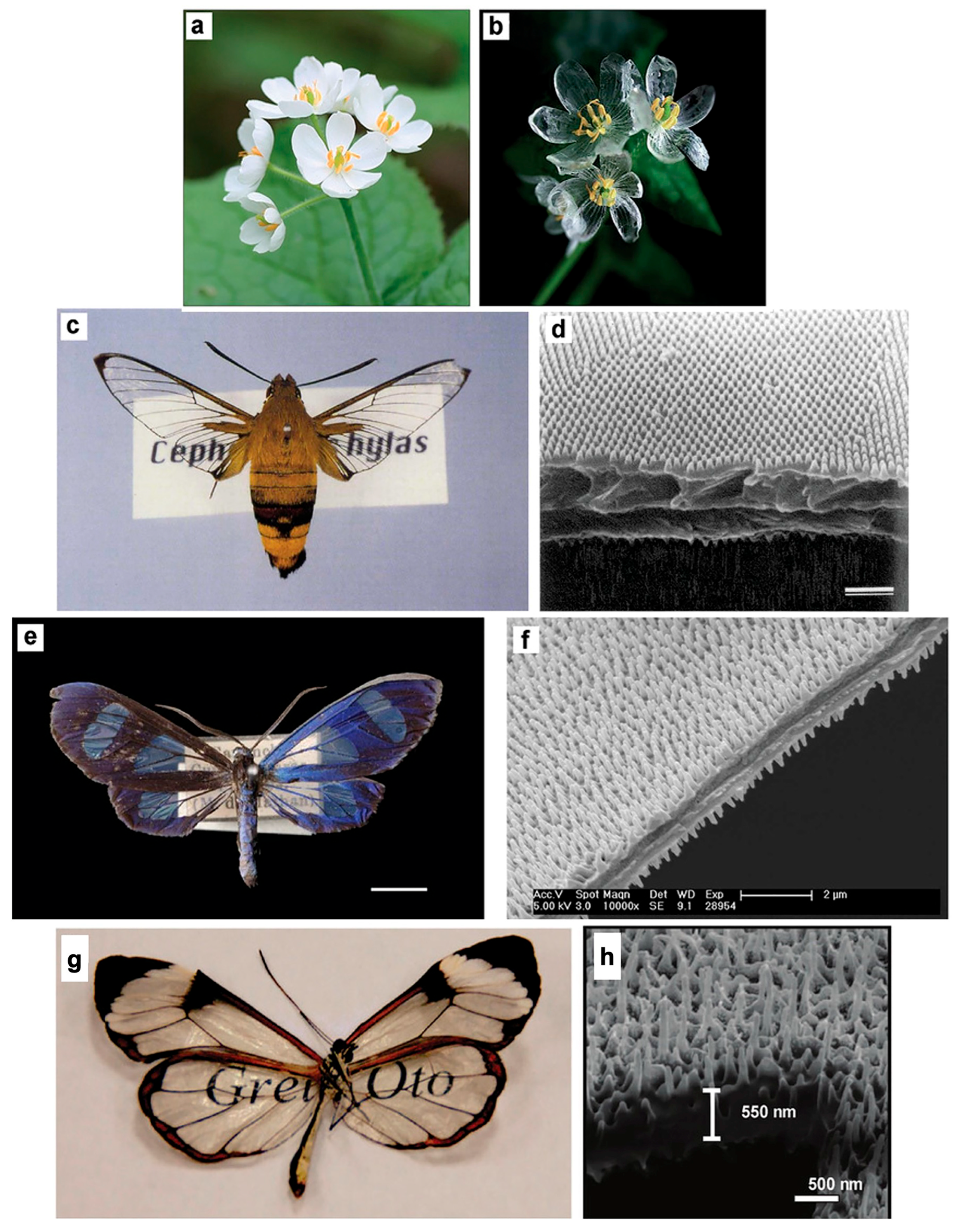

Balsa is one of the most commonly used native woods for producing TW [

29].

Fan and co-workers [

59] exploited a hydrogen peroxide solution in combination with UV radiation (employed as a catalyst) for oxidizing the chromophores of the lignin. Then, the modified balsa wood (2 mm thick) was infiltrated with a melamine formaldehyde resin containing a phosphorus-based flame retardant obtained through the reaction of a cyclic phosphate ester with low molecular weight (MW) poly(ethylene glycol). The optical properties of the final material were evaluated by measuring the optical transmittance, reflectance, absorption, and haze of the TW samples within the UV and Vis wavelength range. Despite lignin modification, the high difference in RI between air and the cell walls (1 vs. 1.53, respectively) accounted for a quite limited transmittance both in the longitudinal and transverse directions (i.e., respectively, parallel and perpendicular to the direction of wood growth), showing values below 60 and 50%, respectively. Conversely, optical transmittance values as high as 95 and 86% within 600 and 800 nm were obtained, respectively, in the longitudinal and transverse directions in the TW specimens. This finding was ascribed to the excellent matching between the RI of the infiltrated polymer and that of the wood cell walls after lignin modification. Furthermore, the TW exhibited a high haze level (approximately 96%), making it an ideal material for use in glazing applications, which provide uniform indoor lighting while ensuring privacy and visual comfort. Additionally, this high haze suggests that this TW is suitable for solar cells, which can boost the photoelectric conversion rate by enhancing the forward scattering of incident light.

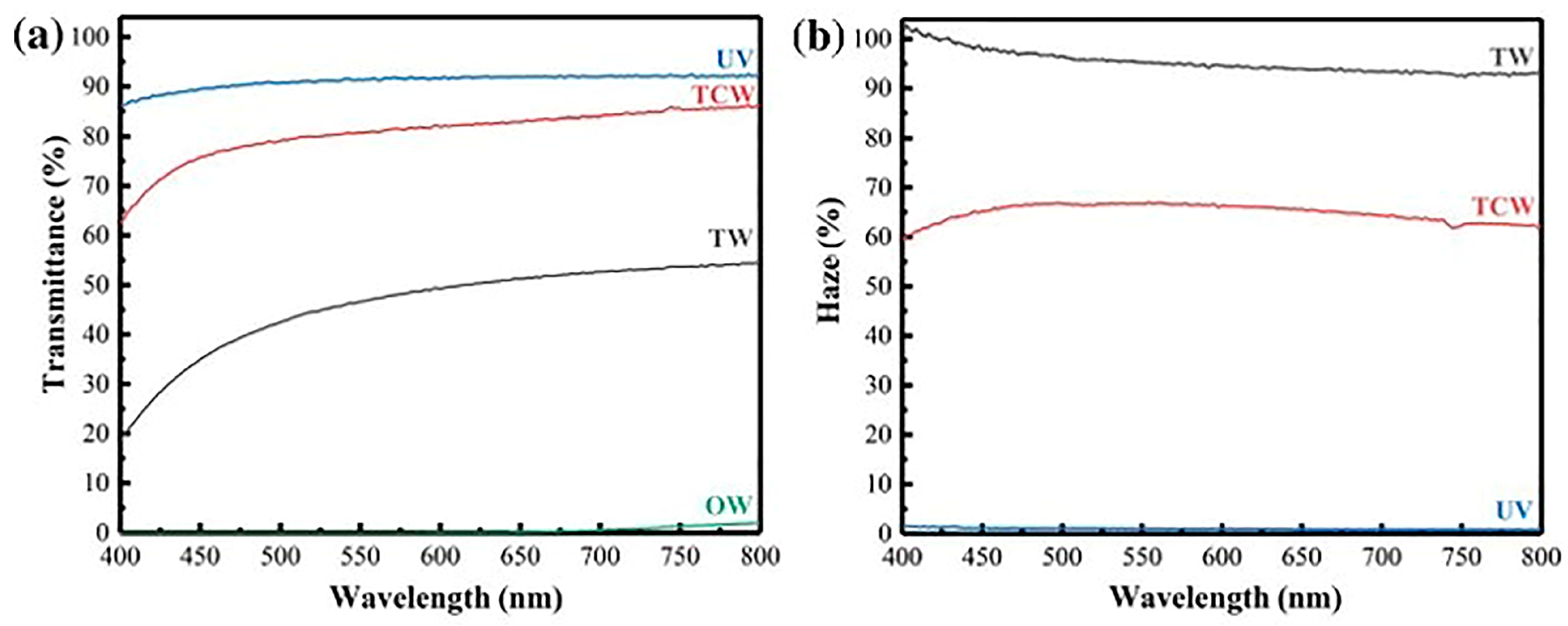

Another interesting approach for enhancing the optical behavior of TW was proposed by Wang and co-workers [

41], who first treated the native wood with NaClO

2 in acidic conditions. Then, after densification of the cell walls by applying an external pressure, a delignified wood template was obtained. Finally, the template underwent a vacuum impregnation step with a UV-curable resin to obtain, after UV-curing, the final compressed TW (thickness of about 0.7 mm). The optical transmittance and haze were measured with a visible light photometer operating between 380 and 780 nm. The optical transmittance of the transparent compressed wood at 550 nm wavelength (

Figure 3) was remarkably higher (about 81%) than that of the TW obtained using the same delignification, infiltration, and UV-curing procedures, but omitting the compression step (around 47%). This finding was attributed to the densification effect exhibited by the transparent compressed wood, in which the scattering phenomena were limited due to the reduced porosity of the wood template and, consequently, the entrapped air. This densification effect also decreased the haze, which changed from around 95 to 67% at 550 nm for TW and its compressed counterpart, respectively.

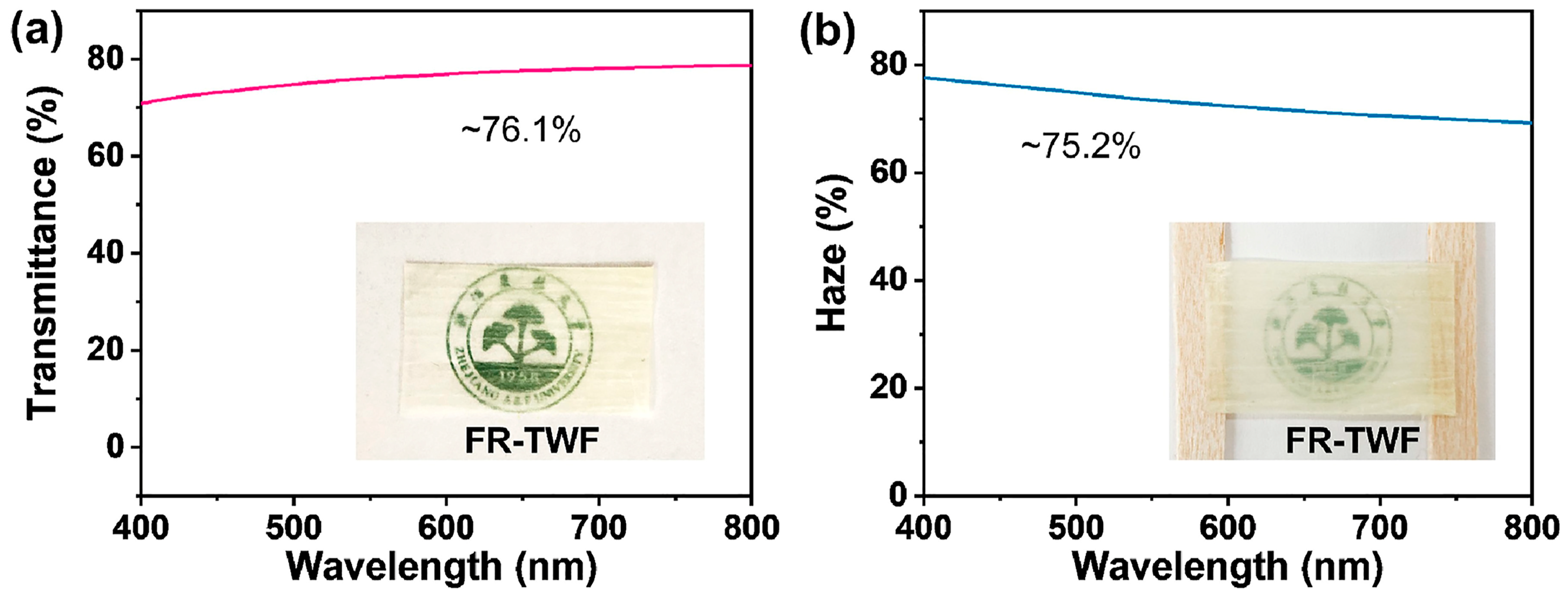

Zhou et al. [

60] exploited a top-down chemical strategy for obtaining flame retarded TW. In particular, 2 mm thick balsa slices were first treated with sodium chlorite in acidic conditions and then went through a 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl radical (TEMPO)-mediated oxidation treatment to complete the lignin removal and provide the wood channels with carboxyl groups, favoring the subsequent chelation with Al

3+ cations. Finally, the resulting material underwent a self-densification/drying process, giving rise to a structure with fully collapsed cell walls and an elastic lumen. As shown in

Figure 4, the optical transmittance and haze at 550 nm wavelength were approximately equal to 75%; this finding was ascribed to the collapsed cell walls that provided the TW with a uniform RI (approaching 1.53).

Wang and co-workers [

61] succeeded in obtaining editable shape-memory TW materials exhibiting interesting optical features. To this aim, balsa wood slices (2 mm thick, taken from both longitudinal and transverse directions) were first treated in acidic NaClO

2 solution, freeze-dried, and subsequently infiltrated with an epoxy vitrimer (i.e., bearing exchangeable covalent bonds), and cured. Optical transmittance and haze were evaluated using a light diffusion system equipped with an integrating sphere; in addition, the material’s light scattering was assessed with a green laser (wavelength: 532 nm) irradiating the samples at a 50 cm distance. The results are presented in

Figure 5.

Both optical transmittance and haze were found independent from the cut direction of wood, and equal to 60 and 95%, respectively. Conversely, optical anisotropy was observed when the TWs were tested using the green laser: in fact, the transmitted light scattering revealed an anisotropic pattern for the longitudinal TW samples only, which showed larger angular distributions along the x-direction (that is perpendicular to the orientation of the wood channels) than those along the y-direction (that is parallel to the orientation of the wood channels). This finding was ascribed to the higher alignment of cellulose nanofibers along x-direction.

Wu et al. [

62] delignified balsa wood (thickness: 1.2 mm) via acidified NaClO

2 solution; meanwhile, they synthesized titania nanoparticles by in situ hydrolysis of tetrabutyl titanate and dispersed them in an epoxy resin, suitable for the infiltration process, at different loadings and in the presence of 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (used as a compatibilizer); finally, the infiltrated wood was cured. Haze and optical transmittance were measured using a scan UV–Vis–NIR spectrophotometer. Unlike the TW not embedding titania nanoparticles, which showed a limited transmittance (about 60%) in the visible wavelength range, the presence of increasing amounts of nanofiller accounted for a remarkable increase in the transmittance (up to 90%): this finding was attributed to the high RI of titania nanoparticles, which increased the low RI of the epoxy system, hence better matching with that of the delignified wood and increasing the optical transparency of the final material. Conversely, the incorporation of the nanofiller into the infiltrated epoxy did not affect the haze, which was around 90%.

Samanta et al. [

63] applied bleaching or delignification to balsa wood veneer (typical size: 20 × 20 × 1 mm

3). Bleaching was carried out using an aqueous solution including sodium silicate, sodium hydroxide, magnesium sulfate, hydrogen peroxide, and dimethylallyl triamine penta-acetic acid, operating at 70 °C until the treated wood achieved a white coloration. For the delignification of balsa wood veneer, an acetate buffer (pH around 4.6), including sodium chlorite, was used at 80 °C until the treated wood achieved a white coloration. Subsequently, the so-obtained materials were infiltrated with a flame-retardant, water-soluble melamine formaldehyde resin, cured at 150 °C for 15 min.

Figure 6 shows the transmittance and haze of the obtained TWs, compared with those of a birch TW infiltrated with PMMA.

It is worth noticing that the TW obtained from bleached balsa wood, where lignin chromophores were removed, exhibited a higher optical transmittance than the counterpart from delignified balsa wood: this finding was ascribed to a reduction in such optical defects as voids and debond gaps, which promote light scattering. In addition, high haze values (around 90%) were measured within the investigated wavelength range for both types of balsa TWs. Finally, the scaling up of the production of larger transparent wood samples from bleached balsa (size of 200 × 100 × 1 mm3) did not affect the optical properties of the obtained materials: indeed, the overall optical performance of large-sized specimens was similar to that of small-sized counterparts.

Tan and co-workers [

64] delignified 2 mm thick balsa wood (cut in both transversal and longitudinal direction with respect to the wood growth) by treating it at 80 °C in 1 wt.% NaClO

2 aqueous solution for several hours; the pH of the solution was adjusted to 4.6 with glacial acetic acid. Then, the so-obtained wood was infiltrated with a vitrimeric mixture made of hexamethylene diisocyanate and tris(3-mercaptopropionate) (molar ratio between the two components: 3:2) and cured up to 60 °C. The resulting TW containing exchangeable thiocarbamate bonds showed multifunctional features (i.e., outstanding mechanical behavior in the longitudinal direction, with flexural and tensile strengths of about 49 and 37 MPa, respectively, thermal conductivity as low as 0.30 W⋅(mK), and shape reprocessability and restorability). In addition, as far as the optical properties of the final material are considered (

Figure 7), high transmittance and haze over the visible wavelength range were observed (both achieving about 90% at 800 nm) for the TW cut in the transverse direction. At the same time, lower values of the two parameters were measured in the longitudinally cut counterparts (around 71 and 72% at 800 nm, respectively). This finding was attributed to a discrete RI variation along the longitudinal direction, which was promoted by the highly aligned cellulose nanofibers in the perpendicular direction (z-axis), hence resulting in an anisotropic scattering of transmitted light in the longitudinally cut samples.

To obtain a transparent and fireproof wood, Chu et al. [

65] infiltrated delignified balsa wood with phosphate ester-polyethylene glycol. Delignification was carried out by soaking the native wood in a 2.5 M H

2O

2 solution for 48 h. The infiltrated monomer was then cured, and the performance of the final TW was compared with the same material infiltrated with an epoxy monomer (i.e., diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A). Apart from excellent flame retardant features (i.e., self-extinction in horizontal flame spread tests and limiting oxygen index values as high as 37%), the transmittance of the TW infiltrated with phosphate ester-polyethylene glycol was around 93% within the visible wavelength range, i.e., higher than the corresponding counterpart infiltrated with the epoxy monomer (about 82%). Furthermore, the high haze of the TW infiltrated with phosphate ester-polyethylene glycol (around 98% in the visible wavelength range) suggested its potential suitability for civil engineering applications, e.g., for glazing and roofing components.

Interestingly, Sun and co-workers [

66] carried out a 24 h treatment of 1 mm thick balsa wood slices in 1 wt.% NaClO

2 solution buffered at pH = 4.6 with acetic acid, at 80 °C. Then, the delignified wood underwent TEMPO-mediated oxidation and was subsequently infiltrated with commercially available alkali lignin, resulting in the formation of “reconstructed” TW. Compared with densified natural wood (obtained through hot-pressing native wood previously soaked in acetone), the reconstructed wood showed a much higher optical transmittance (with a maximum of about 48% at 800 nm; see

Figure 8): this finding was attributed to its more densely packed structure, due to the alkali lignin infiltration.

Zhang and co-workers [

67] delignified balsa wood slices (thickness: 1 mm) by using a 2 wt.% solution of NaClO

2, buffered with glacial acetic acid at pH = 4.6, at 80 °C for 48 h. Then, poly(vinyl alcohol) incorporating 1, 2, or 3 wt.% of delaminated Ti

3C

2T

x (MXene) nanosheets was infiltrated into the delignified wood after it underwent freeze-drying for 48 h. As shown in

Figure 9, increasing amounts of MXene nanosheets accounted for color darkening, as well as the decrease in the optical transmittance and increase in the haze of the resulting TWs. This finding was ascribed to the increasing absorption and scattering of the incident radiation because of the increase in the RI gap between poly(vinyl alcohol) and cellulose (due to the incorporated nanofiller), which promoted the occurrence of broader scattering phenomena at the interface between the polymer and the wood channels.

Ding et al. [

68] delignified balsa wood (2.5 mm thick) with 2.5 wt.% NaClO

2 solution buffered at pH = 3.5 with acetic acid. The process was carried out at 70 °C for 24 h. Then, the delignified wood (about 2.7% lignin content) was infiltrated with a bisphenol A diglycidyl ether-based epoxy system, cured, and, finally, coated with a perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane coating. The latter provided the TW with high hydrophobicity, achieving water contact angles of about 113°. Additionally, the resulting TW exhibited acceptable optical transmittance and haze of around 67 and 73%, respectively, at 750 nm.

An interesting approach for obtaining a multifunctional TW was recently proposed by Wang and co-workers [

69], who designed and developed a shape-reconfigurable, thermally insulating TW through the infiltration of polythiourethane vitrimers into delignified wood (thickness: 1 or 2 mm). The latter was obtained through a treatment with 1 wt.% NaClO

2 aqueous solution (keeping the pH at 4.6 with acetic acid, working at 80 °C, and replacing the solution every 6 h). The optical transmittance of the obtained TW was about 87 and 82%, respectively, for specimens 1 and 2 mm thick. Further, the haze referred to the same thicknesses was quite high, i.e., around 73 and 89%, respectively. These results were ascribed to the microstructural roughness of the final material.

Shi et al. [

70] were among the first to provide further sustainability to TW. To this aim, balsa wood (0.8 mm thick) was first treated with a 5 wt.% NaClO

2 solution in acidic conditions (keeping the pH at 4.6 through the addition of acetic acid), at 90 °C. Then, the obtained delignified wood was further treated with 30 wt.% hydrogen peroxide solution at 90 °C for 1 h. Meanwhile, phenol was reacted with glucose, both being prepared through the catalytic degradation of the lignin and cellulose, respectively. Then, the obtained polymer was infiltrated into the delignified and bleached balsa wood operating under vacuum at room temperature and finally cured. The so-obtained TW showed a limited optical transmittance, achieving around 46% at 800 nm. This finding was attributed to the porosity resulting from the delignification process, which was not thoroughly saturated with the infiltrated polymer, probably due to interface incompatibility issues between the polymer and the delignified wood channels.

Chen et al. [

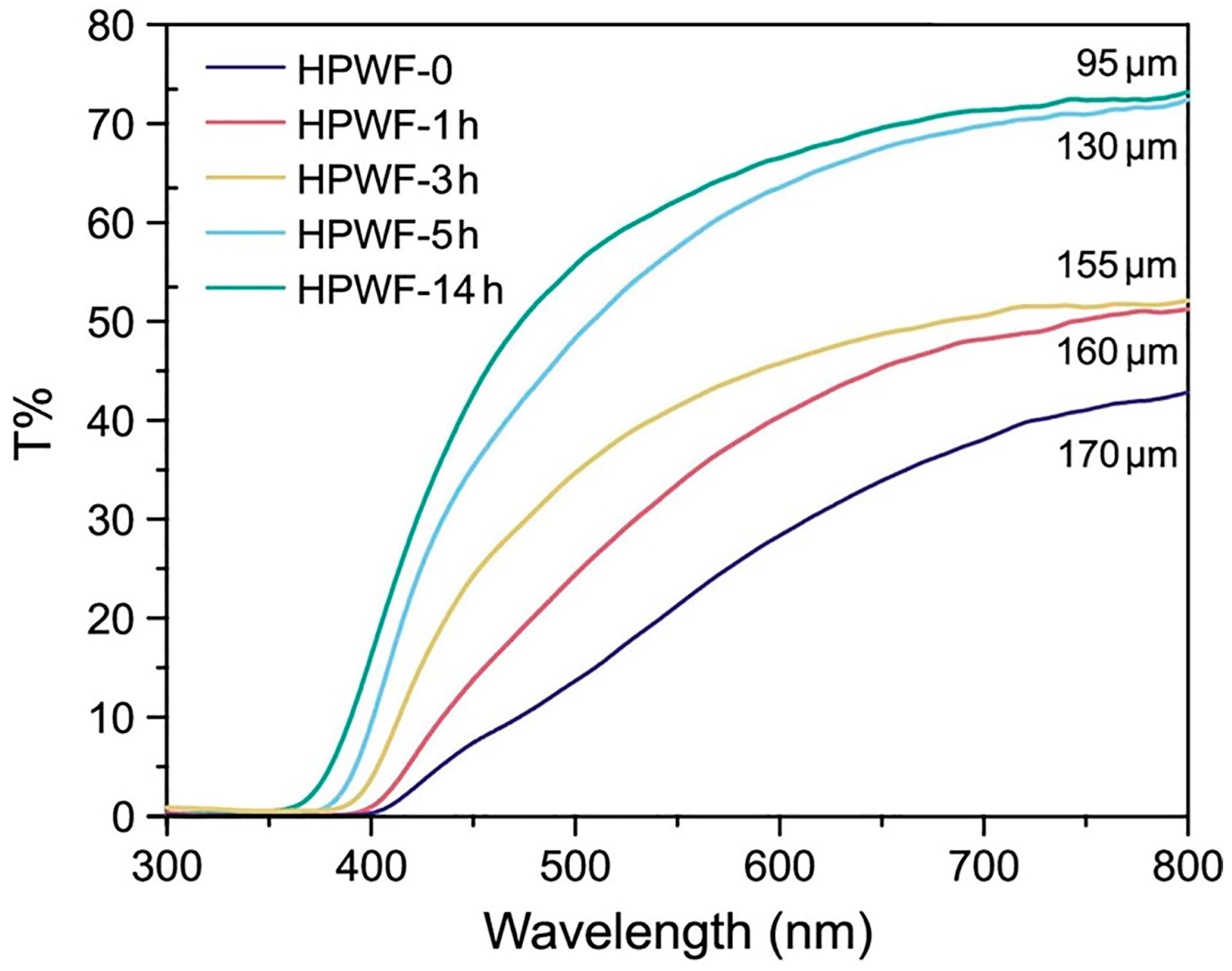

71] demonstrated that UV radiation can be successfully exploited for speeding up the lignin removal from balsa wood. For this purpose, 1 mm thick native wood samples were immersed into a solution consisting of H

2O

2, ammonia, and deionized water (keeping a ratio of 5:1:5 among the three components) for different times (from 2 up to 8 h), under continuous UV irradiation provided by a UV lamp (30 W) emitting between 385 and 395 nm. As reference materials, another set of samples underwent the same treatment in the dark (i.e., without having been UV-irradiated). The delignified materials were, then, infiltrated with an epoxy system under vacuum for 3 h and finally cured at room temperature for 1 day. As expected, the optical transmittance was remarkably affected by the duration of the delignification process. In this context, UV exposure accounted for accelerating the removal of the chromophore groups of lignin, hence leading to an overall improvement of the optical transmittance of the obtained TW (

Figure 10). Interestingly, the optical transmittance increased with the infiltration time, while the haze gradually decreased, resulting in better optical properties. These findings were attributed to a decrease in the porosity in the wood channels infiltrated by the epoxy system.

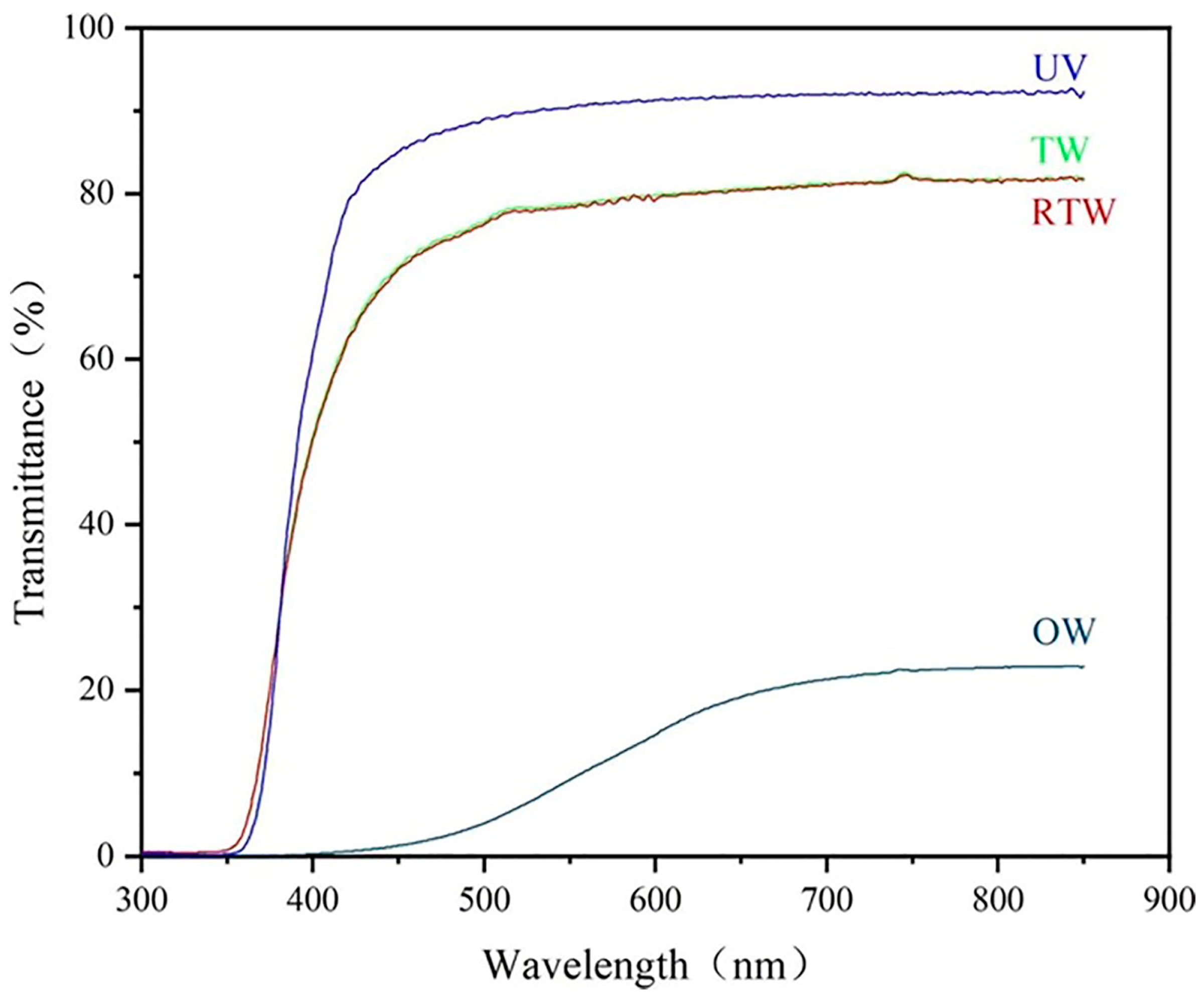

In a further research effort toward sustainability, Hai et al. [

72] proposed three different methods for the delignification of balsa wood (1 mm thick), namely: solar-assisted bleaching (employing H

2O

2/NaOH as bleaching agents and exposing the treated wood to direct sunlight), steam bleaching (treating the native balsa wood at 90 °C for 3.5 h with a H

2O

2/NaOH solution, also deposited onto the wood surface), and NaOH delignification (carried out at 90 °C for 6 h). Meanwhile, kraft lignin was converted into lignin nanoparticles, which, in turn, were incorporated into a poly(vinyl alcohol)/propylene glycol mixture at different loadings (i.e., 1, 2, and 3 wt.%), vacuum-infiltrated in the delignified wood and finally dried. As shown in

Figure 11, the method employed for the delignification step remarkably affected the optical transmittance of the resulting TWs. In particular, within 600 and 800 nm wavelength, the material derived from NaOH delignified balsa wood exhibited an optical transmittance as high as about 80%, unlike the counterparts obtained through solar-assisted or steam bleaching, for which the optical transmittance was between about 60 and 65%. Further, the incorporation of increasing amounts of lignin nanoparticles accounted for a progressive decrease in the optical transmittance: this finding was attributed to the high RI of the nanoparticles (around 1.61), which promoted light absorption/scattering phenomena.

Chen et al. [

73] delignified wood slices (1 mm thick) by treating them in an acidic solution (pH = 4.6) of sodium chlorite, working at the boiling point of the solution for 2 h. Then, the resulting delignified wood underwent an oxidation process in a 1 wt.% NaIO

4 solution at 50 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the dialdehyde-oxidized wood experienced a densification process at 60 °C for 48 h, after which it was laminated to obtain a three-ply transparent material. This material, which was about 3 mm thick, exhibited very low haze (around 20%) and high transmittance (approximately 85%) within the visible wavelength range. This is thanks to the material’s limited porosity (around 8%), which was achieved through the oxidation process of the wood cellulose. This process decreased the scattering centers (i.e., air voids) present in the laminate.

Yin et al. [

74] succeeded in manufacturing a white luminescent TW, exploiting the incorporation of graphite carbon nitride (synthesized on purpose) into an epoxy system that was infiltrated in the delignified wood. The latter was obtained by treating the wood slices (2 mm thick) in a 5 wt.% NaOH solution at 90 °C for 2 h. The final curing of the infiltrated epoxy system was carried out at room temperature for 72 h. The optical transmittance of the final material exceeded 80% within the wavelength range of 500 to 800 nm. Additionally, the very high haze (approximately 82% within the same wavelength range), combined with the luminescent features, suggested the potential suitability of the material for designing photoelectric devices.

The optical features of TW were recently exploited for the design of thermochromic materials for smart windows [

75]. In particular, balsa wood slices (1.5 mm thick) were rotary cut, subsequently brushed with hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide, and finally exposed to UV radiation for 20 min. This process was repeated about 10 times, which was the amount of time needed to deactivate the lignin chromophores sufficiently. Then, the so-obtained material was vacuum-infiltrated with pre-polymerized methyl methacrylate for 24 h; the final polymerization took place in an oven at 70 °C for 4 h. In addition, to provide thermochromic features to the TW, its surface was spin-coated with a layer of MA

4PbI

5Br

1·2H

2O halide hybrid perovskite precursor (middle layer) and a further layer of PMMA (top layer). Within the visible wavelength range, in the cold state, the optical transmittance was around 78%; it dropped down to about 25% in the hot state, hence demonstrating the suitability of the materials for the design of thermochromic devices.

A similar approach was proposed by Wang and co-workers [

76], who exploited an effective and sustainable approach for obtaining a hydrophobic TW. For this purpose, they employed a UV-assisted method for the in situ removal of the lignin chromophores: native balsa wood (1.5 mm thick) first was treated with a mixture consisting of hydrogen peroxide, ammonia, and deionized water (7:1:3 volume ratio) under exposure to UV radiation for 4–6 h. Subsequently, after a drying step, the treated wood was infiltrated under vacuum with an epoxy system and cured. The obtained TW was, then, dipped in a polydimethylsiloxane-hexane solution for 10 min and cured in a vacuum drying oven at 80 °C for up to 4 h. Apart from the high hydrophobicity achieved after the final treatment with polydimethylsiloxane (as witnessed by the very high static contact angle values with water, around 130°), as shown in

Figure 12, even the non-hydrophobic TW exhibited a high transparency. Moreover, the average optical transmittance and haze in the wavelength range of 400–700 nm were about 90 and 80%, respectively, hence indicating the potential suitability of the material for solar cells, smart windows, and energy-efficient building applications.

Wu et al. [

77] produced a three-layer TW exhibiting thermal energy storage function. To this aim, a core made of delignified balsa wood vacuum-infiltrated with polyethylene glycol (average molecular mass: 1000 g/mol)-silica for 2 h and subsequently freeze-dried for 48 h was stacked within two delignified balsa wood layers infiltrated with methyl methacrylate (successively thermally polymerized). For the delignification step, the wood slices were treated with a 2 wt.% sodium chlorite solution, maintaining the pH at 4.6 with glacial acetic acid and operating at 85 °C, until the wood turned white. The multilayered final material (about 2.2 mm thick) exhibited 45 and 76% of optical transmittance and haze, respectively, at 800 nm wavelength, as well as a very homogeneous distribution of the scattered light, notwithstanding important heat storage capacity (with a latent heat as high as 15.0 J/g) and thermal stability.

The possibility of combining good optical transmittance with luminescent features in TW was assessed by Zhou and co-workers [

78]. They first synthesized carbon quantum dots exhibiting yellow/red fluorescence from chitosan and o-phenylenediamine. The obtained material was then dispersed into a diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A-based epoxy system at a concentration of 10 g/L, vacuum-infiltrated into delignified wood for 30 min, and finally cured. For the delignification step, 1 mm thick balsa wood slices were treated with a 2 wt.% solution of sodium chlorite, keeping the pH constant at 4.6 by means of glacial acetic acid, and working at 80 °C for around 6 h. The red fluorescent TW exhibited good optical transmittance (about 70%) in the visible wavelength range, as well as effective UV blocking features. Specifically, it blocked approximately 79% of UV-B radiation and 78% of UV-A radiation.

Chen et al. [

79] succeeded in obtaining TW films by exploiting a multistep process comprising: (i) the delignification of native wood slices (starting thickness: 1 mm) treated at 80 °C for 6 h with a mixture (equal volume) of glacial acetic acid and H

2O

2; (ii) the subsequent infiltration of the delignified wood in an aqueous solution of an ionic liquid (namely, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, employed at 80 wt.% concentration) under vacuum at room temperature; (iii) the removal of the ionic liquid and the drying under vacuum in an oven at 60 °C for 4 h to attain capillary force driven self-densified TW films. The latter (around 150 μm thick) exhibited an optical transmittance and haze of about 70 and 95%, respectively.

In a further research effort toward sustainability, Zhou and co-workers [

80] first delignified native wood slices (starting thickness: 1 mm) by treating them in a 2 wt.% sodium chlorite solution buffered at pH 4.6, for 2 h at the boiling point of the solution. Then, hemicellulose was largely removed by dipping the delignified wood in 15 wt.% sodium hydroxide solution for 2 h, at 40 °C. The next step was to oxidize the obtained material using a 1 wt.% NaIO

4 solution at 50 °C for 4 h. Then, the modified wood was densified, grafted with a 0.1 wt.% gelatin solution at 60 °C for 4 h, and physically crosslinked with tannic acid at room temperature for 2 days. The densified TW (approximately 0.1 mm thick and fully biodegradable) exhibited high optical transmittance (around 86% at 600 nm), low haze (approximately 17% across the entire visible spectrum), and effective 100% UV-B blocking.

One example of thick TW showing interesting optical behavior was proposed by Liu and co-workers [

81]. To this aim, a 1 wt.% NaClO

2 aqueous solution was prepared and subsequently adjusted to a pH of 8.5 using glacial acetic acid. The wood slices (2 mm thick) were immersed in the delignification solution at a temperature of 80 °C for a period of 18 h. The delignification solution was replenished every 6 h, and the slices were left to soak until they had thoroughly changed color from their original shade to white. Then, a mixture of epoxy monomer (unspecified) and trimethylolpropane tri (3-mercaptopropionic acid) ester was employed for the infiltration process, working under vacuum, at room temperature, for 20 min, and finally cured at 120 °C for 2 h. The obtained TW exhibited soft-hard switchable behavior due to its low glass transition temperature (around 0 °C), as well as shape recovery features. Intriguingly, despite its considerable thickness, its optical transmittance averaged 70% in the visible wavelength range.

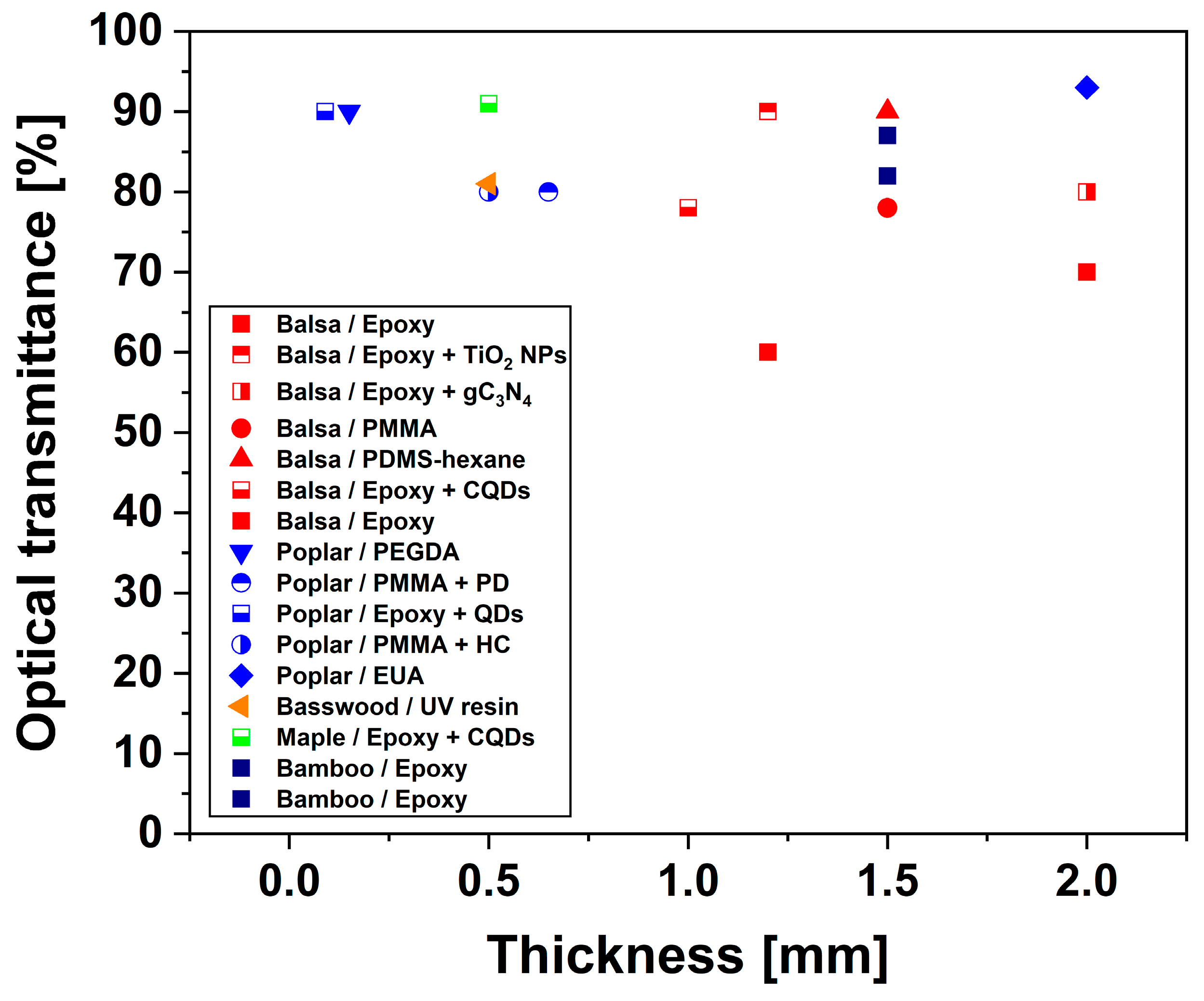

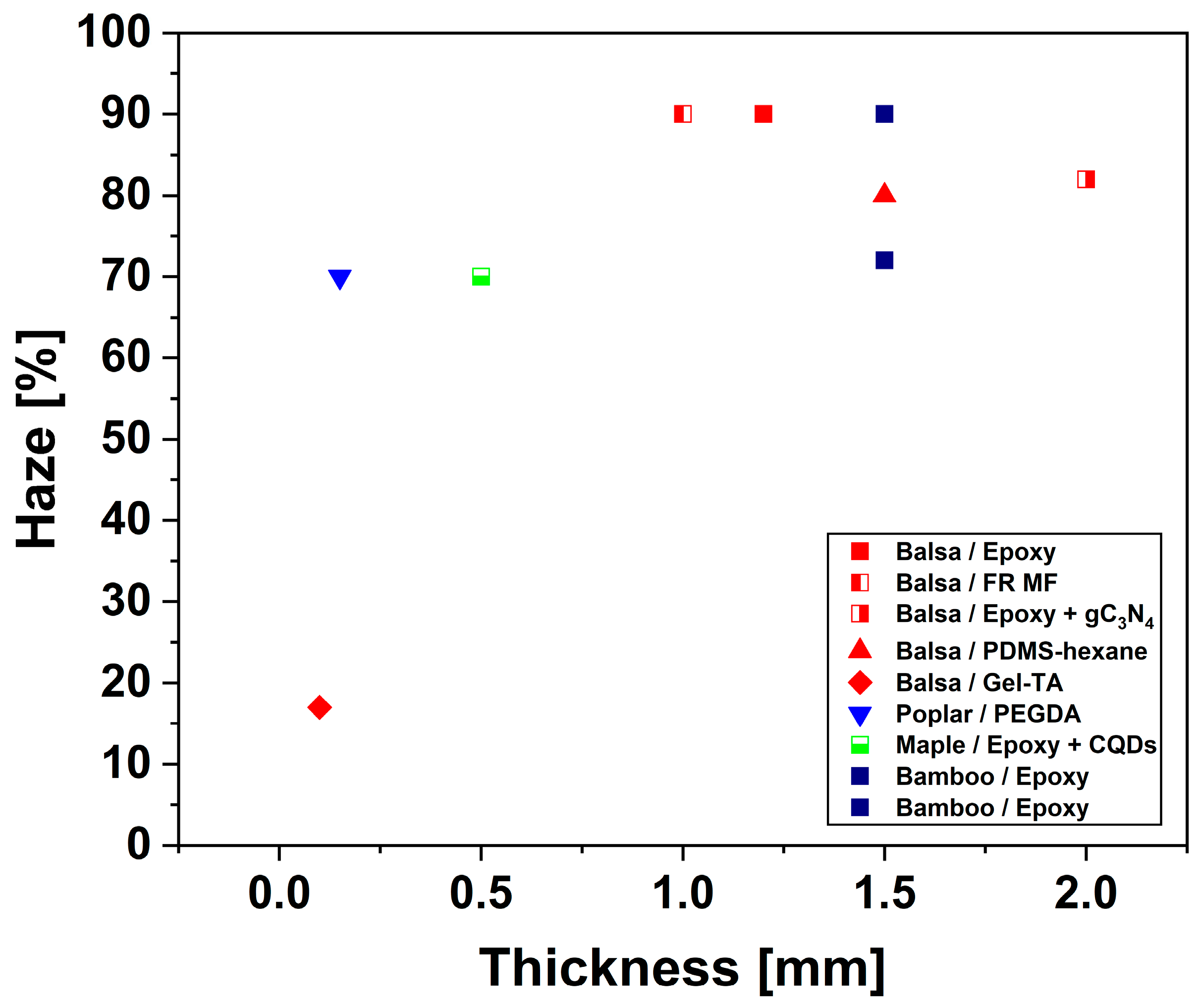

In a very recent paper, Wu and co-workers [

82] demonstrated the feasibility of preparing multifunctional (i.e., UV-shielding and thermally insulated) TW samples with high optical transmittance (around 90%) and low haze (about 55%) in the visible wavelength range. To this aim, wood slices (5 × 5 cm

2; the thickness ranged from 0.5 to 2 mm) were first immersed in an aqueous peroxyacetic acid solution with a pH of 4.8, adjusted using sodium hydroxide, at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 and at 80 °C. After about 2–4 h, the wood chips turned white, indicating the completion of the delignification process. Then, the delignified wood was immersed in a mixture of pre-polymerized methyl methacrylate and 4-vinylphenyl boronic acid (mass ratio up to 8:100) under vacuum for 30 min. Finally, it was cured under UV radiation for 1 h.

Table 1 summarizes the main optical outcomes related to the different TW systems discussed in the section.