Abstract

The pectic polysaccharides extracted from flaxseed (Linum usitatissiumum L.) mucilage and kernel were characterized as rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I). In this study, the conformational characteristics of RG-I fractions from flaxseed mucilage and kernel were investigated, using a Brookhaven multi-angle light scattering instrument (batch mode) and a high-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) system coupled with Viscotek tetra-detectors (flow mode). The Mw of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) was 285 kDa, and the structure-sensitive parameter (ρ) value of FM-R was calculated as 1.3, suggesting that the FM-R molecule had a star-like conformation. The Mw of flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R) was 550 kDa, and the structure-sensitive parameter (ρ) values ranged from 0.90 to 1.21, suggesting a sphere to star-like conformation with relatively higher segment density. The correlation between the primary structure and conformation of RG-I was further discussed to better understand the structure–function relationship, which helps the scale-up applications of pectins in food, pharmaceutical, or cosmetic industries.

1. Introduction

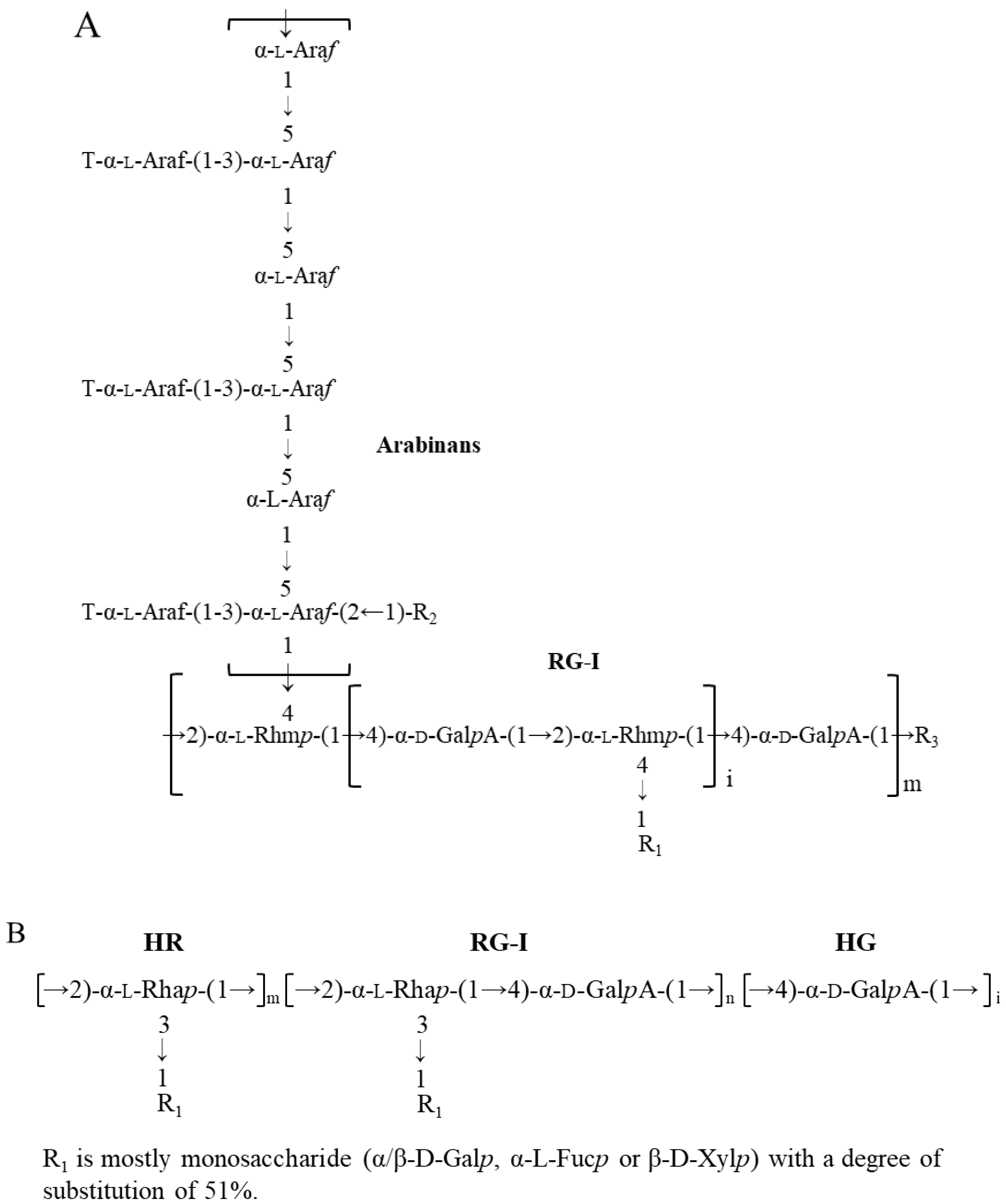

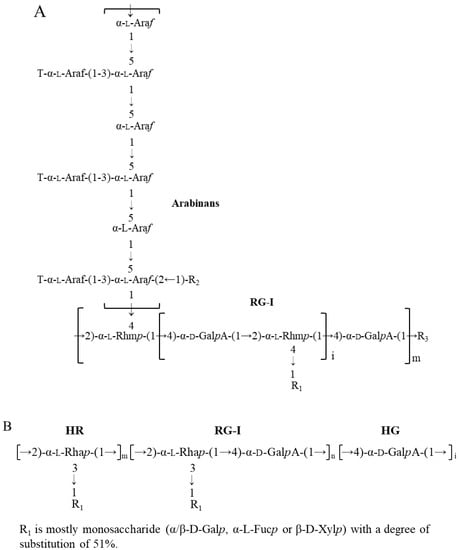

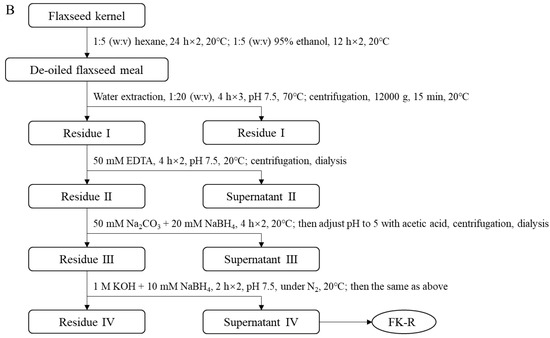

Flaxseed (Linum usitatissiumum L.) is a good source of dietary fibres (22–28%, w/w), in addition to bioactive alpha-linolenic acid (~23%, w/w), protein (~20%, w/w), and phenolic compounds (~1%, w/w) [1,2]. Pectins, arabinoxylans, and xyloglucans are the major dietary fibres in flaxseed. Arabinoxylans mainly exist in flaxseed mucilage, and xyloglucans exist in the kernel, while pectins are found to be widely distributed in both flaxseed mucilage and kernel. The primary structures of flaxseed dietary fibres have been elucidated in our previous studies [3,4,5,6,7]. The water-soluble mucilage extracted from flaxseed hulls by water soaking (yield of 9.7%) were fractionated into a neutral fraction gum and an acidic fraction gum using ion-exchange chromatography. The neutral fraction consisted of high molecular weight (Mw) (1470 kDa) arabinoxylans whereas the acidic fraction (FM-R) was mainly composed of rhamnogalacturonans with a higher Mw fraction (1510 kDa) and a lower Mw fraction (341 kDa). As shown in Figure 1A, the FM-R was highly branched, and 54 mol% of rhamnosyl units in the backbone were substituted by shorter side chains (1~3 residues containing β-D-Galp, α-L-Fucp, or β-D-Xylp units). In addition to the flaxseed hulls, 20% of dietary fibre was also found in the flaxseed kernel, which was separated into several fractions by the sequential extraction method in our previous study [5]. The fraction obtained from 1 M KOH (FK-R) also contained an RG-I fraction, from which the rhamnosyl units were substituted by much longer arabinan side chains (up to 90 arabinofuranose units), as shown in Figure 1B [4,5].

Figure 1.

Proposed RG-I structure from flaxseed hulls ((A), adapted with permission from Ref. [5]) and flaxseed kernel ((B), adapted with permission from Ref. [4]).

The primary structure and conformation played vital roles in the functionality and thus affected the application of pectins. However, the information on the structure–conformation correlation of RG-I is limited from previously published papers, and no study was reported on the structural/conformational comparison of flaxseed RG-I fractions (from either kernel or mucilage). The RG-I fractions from flaxseed kernel and mucilage are supposed to demonstrate different conformational properties due to the different lengths of the side chain, although they possess the same backbone structures. In this study, the conformational characteristics of FM-R and FK-R were investigated using multi-angle light scattering instruments (under either batch or flow mode). The correlation between the primary structure and conformation of flaxseed RG-I was further discussed. The in-depth understanding of the structural characteristics of pectins not only provides novel knowledge on the structural–conformational–functional relationships but also helps bridge the gaps between lab results (e.g., physicochemical, structural, and bioactivity characterization) and scale-up industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

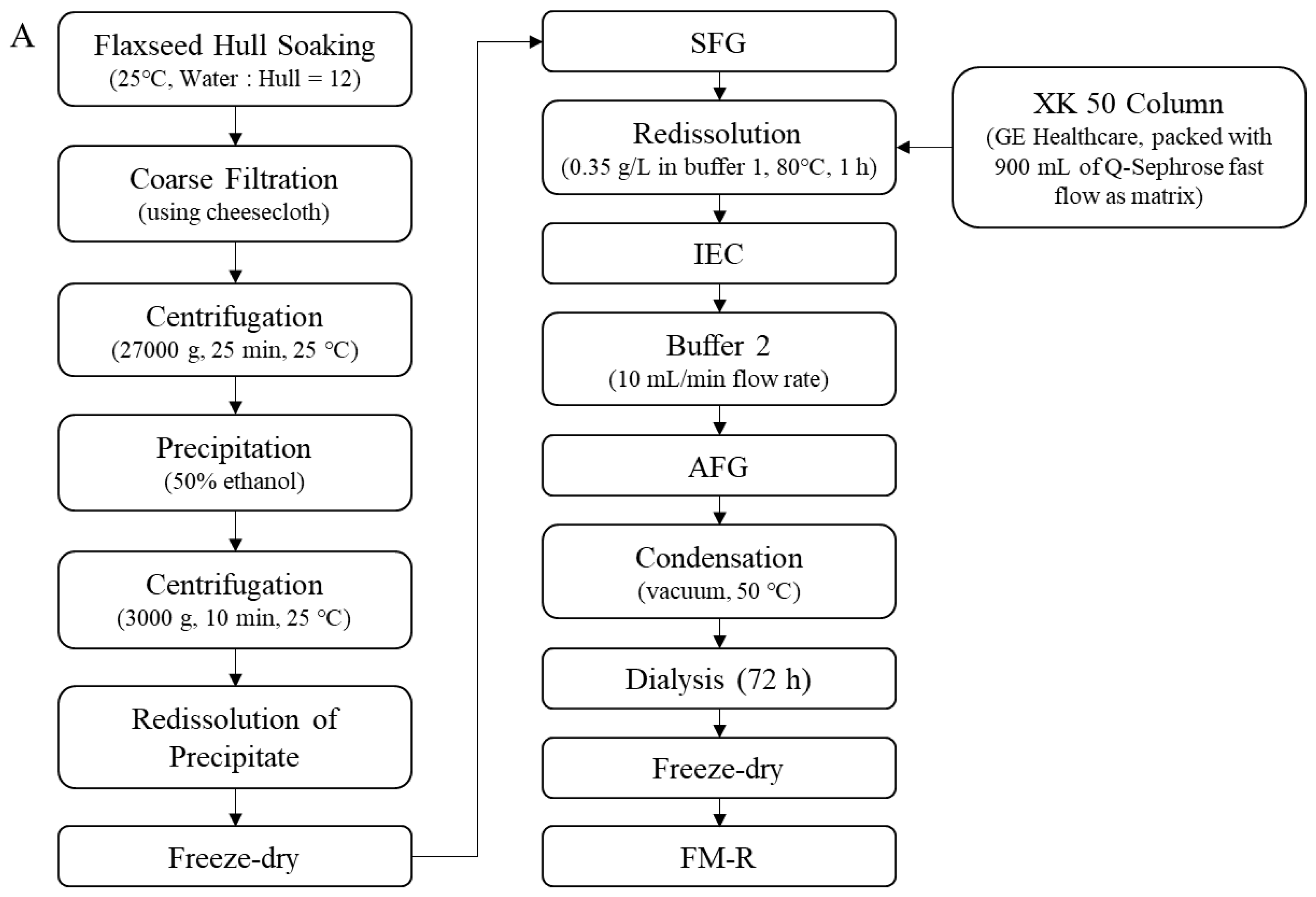

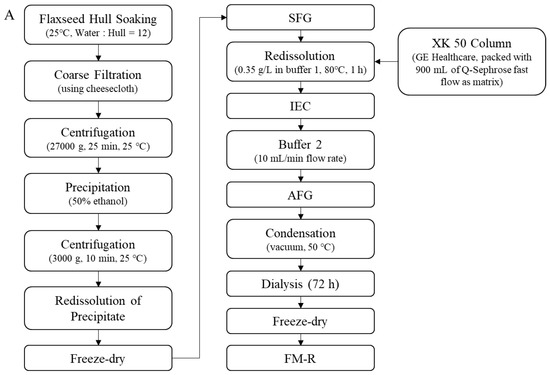

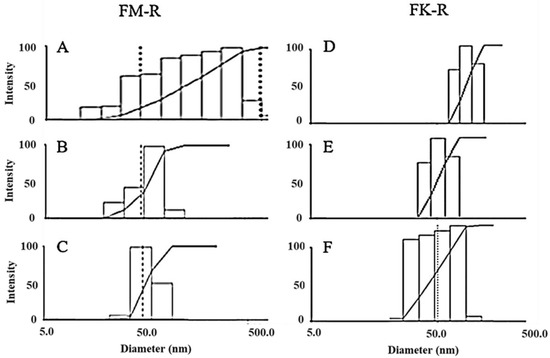

Soluble flaxseed mucilage gum was extracted from flaxseed hulls, and flaxseed mucilage RG-I fraction (FM-R) was collected after ion-exchange chromatography [8]; the extraction and purification process is shown in Figure 2A. Flaxseed kernel RG-I fraction (FK-R) was obtained from sequential extractions as described in previous studies [2,5] and shown in Figure 2B. FM-R contained 38.7 mol% galacturonic acid and the relative neutral monosaccharide composition was mainly rhamnose (38.3 mol%), galactose (35.2 mol%) and fucose (14.7 mol%). FK-R contained 14.6 mol% galacturonic acid and the relative neutral monosaccharide composition was mainly rhamnose (2.7 mol%), arabinose (64.2 mol%), galactose (11.9 mol%) and xylose (17.8 mol%). Flaxseed hulls (cultivar: Bethune) and kernels (~70% purity; cultivar: CDC Sorrel) were supplied by Natunola Health Inc. (Winchester, ON, Canada), and flaxseed kernels (>99.9% purity) were collected through further sieving and selection. The chemicals used were of reagent grade unless otherwise specified.

Figure 2.

Extraction and purification process ((A), flaxseed hull mucilage gum, adapted with permission from Ref. [8]; (B), flaxseed kernel, adapted with permission from Ref. [2]).

2.2. High-Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC)

The elution profiles of flaxseed RG-I fractions were obtained using an HPSEC system (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., MD, USA) coupled with tetra detectors, including a UV detector (Viscotek 2600), and triple detectors (incl. a refractive index detector, a differential pressure viscometer, and the low-angle (7°) and right-angle (90°) light scattering detectors) (Viscotek TDA 305, Malvern, MA, USA). The columns had two AquaGel PAA-M columns and a PolyAnalytik PAA-203 column (Polyanalytik Canada, London, ON, Canada) in series. Elution was performed at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min using 0.1 M NaNO3 with 0.05% (w/w) NaN3, and the column/detector systems were maintained at 40 °C. Pullulan standards with a molecular weight ranging from 50 to 800 kDa (JM Science Inc., New York, NY, USA) were used to calibrate the detectors. Data were analyzed by OmniSEC software (ver. 4.6.1, Malvern, MA, USA), and some conformational parameters (e.g., weight average molecular weight (Mw) and radius of gyration (Rg) could be extracted.

2.3. Conformational Characterization of Flaxseed RG-I

2.3.1. Solution Preparation

As polysaccharide molecules could be easily aggregated in water, solvent selection and dust-free solutions are critical for conformational characterization. In order to eliminate molecular aggregates, different aqueous solutions (e.g., NaCl, NaNO3, NH4OH, NaOH, or KOH at various concentrations) with increasing ion strength were tested. Dust-free solutions were prepared by consecutive filtration RG-I solutions at least four times through 0.45 μm syringe filters. The total sugar contents were tracked before and after filtration, which were determined by the Phenol-H2SO4 method [9].

2.3.2. Intrinsic Viscosity Measurement

The intrinsic viscosities of flaxseed RG-I in different solutions were measured using Ubbelohde viscometer (No. 75, Cannon Institution Company, State College, PA, USA).

where ηrel is relative viscosity; η and η0 is zero-shear viscosities of the solution and the solvent, respectively; t and t0 is the time required for the solution and the solvent to pass through the Ubbelhode viscometer, respectively; ηsp is specific viscosity.

where [η] is intrinsic viscosity, calculated using the Huggins (Equation (4)) and Kraemer (Equation (5)) equations; k′ is the Huggins constant; and k″ is the Kraemer constant [10,11]. The tests were conducted at 25 °C in triplicate.

2.3.3. Light Scattering Analysis

Static light scattering (SLS) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses followed that of previous work [6]. Briefly, SLS and DLS measurements were conducted using a laser light scattering instrument (BI-200SM, Brookhaven Instruments, New York, NY, USA) with a He-Ne laser (637 nm), a photomultiplier, a precision goniometer, and a 128-channel digital autocorrelator (BI-9000AT, Brookhaven Instruments, New York, NY, USA). SLS was carried out at angular ranges of 30°–150°, and Mw and Rg were determined by the Zimm plot method [12].

where K is the optical contrast factor (calculated based on Equation (7)); c is the polymer concentration; Rθ is the Rayleigh ratio; Mw is weight average molecular weight; Rg is the radius of gyration; q is the scattering vector for vertically polarized light (calculated based on Equation (8)); A2 is the second virial coefficient.

where n0 is the refractive index of the solvent; dn/dc is the refractive index increment of the solution; N0 is Avogadro’s number, λ0 is the wavelength in vacuum; θ is the scattering angle. The dn/dc values of flaxseed RG-I in the tested solutions were measured by a differential refractometer (BI-DNDC, Brookhaven Instruments, New York, NY, USA). Instrument alignment was conducted using dust-free toluene (Rayleigh ratio: 1.40 × 10−5 cm−1) as a reference before each test.

The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of flaxseed RG-I was determined by DLS at 90°, which was calculated by the constrained regularization (CONTIN) method using Brookhaven BIC Light Scattering Software. All measurements were conducted immediately after filtration, and relatively lower concentrations (i.e., 0.1~0.2 mg/mL) of flaxseed RG-I solutions were selected in DLS measurements. The structure-sensitive parameter ρ was calculated based on Equation (9) [13].

where ρ is a structure-sensitive parameter; Rg is the radius of gyration; and Rh is hydrodynamic radius. All tests were measured in duplicate at 23 °C.

3. Results

3.1. Elimination of Flaxseed RG-I Molecular Aggregation in the Solutions

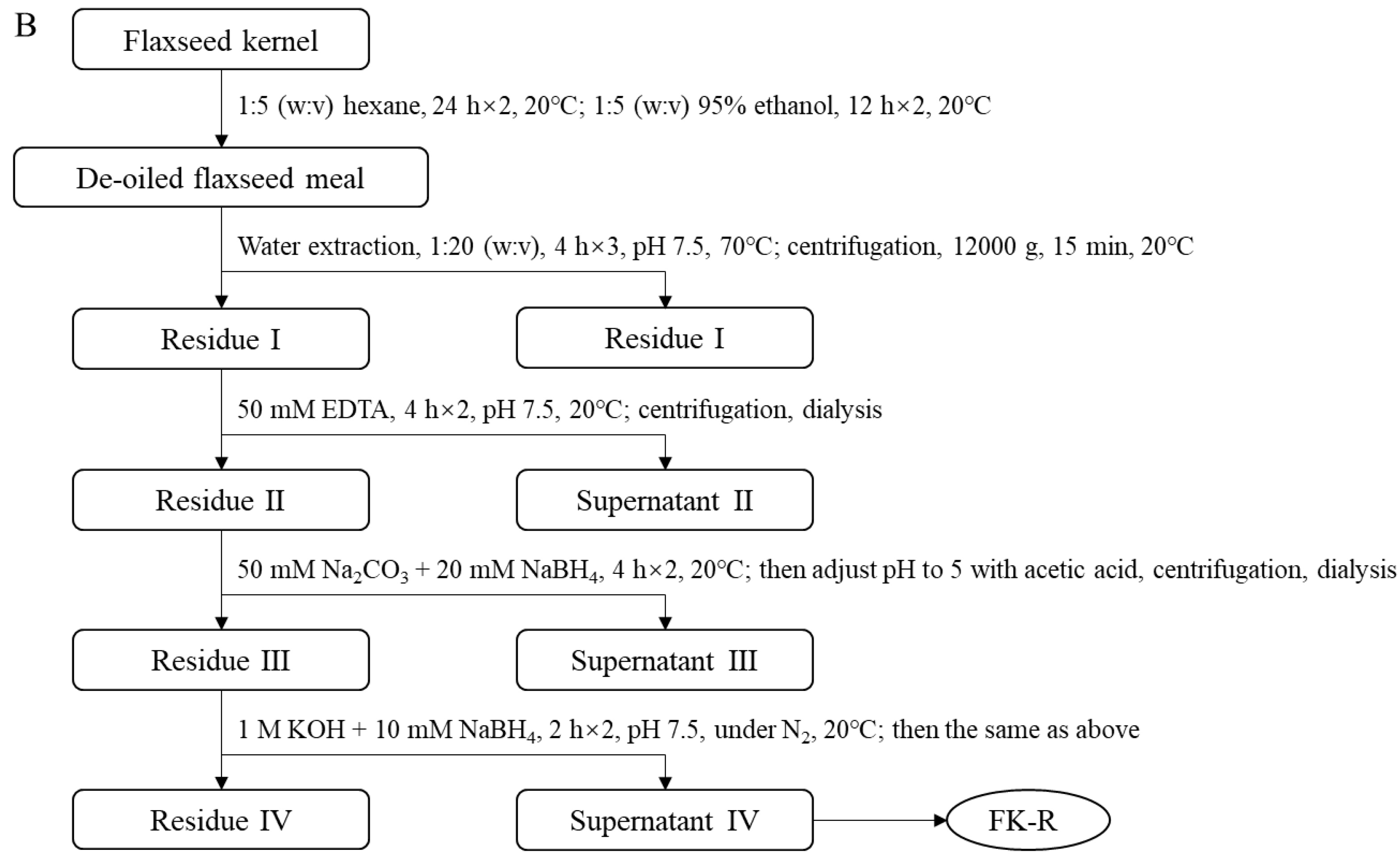

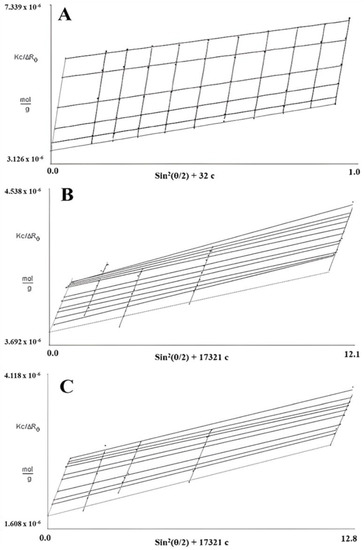

Flaxseed RG-I molecular distributions in various solutions were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 3). Polysaccharides could easily aggregate in water (Figure S1A), and various non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals force, ionic, and hydrophobic interactions) contribute to molecular aggregation. Different solutions with increasing ion strength, including 0.1 M NaNO3, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 M NaOH, 6 M NH4OH, 0.5 M NaOH, or 0.5 M KOH aqueous solutions, were utilized to eliminate the aggregation for a precise characterization of flaxseed RG-I conformation.

Figure 3.

The molecular size distribution of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) in 0.1 M NaCl (A), in 0.1 M NaOH (B), and in 0.5 M NaOH (C), and flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R) in 0.1 M NaNO3 (D), in 6 M NH4OH (E), and in 0.5 M NaOH (F) determined by dynamic light scattering (at 0.1 mg/mL solution concentrations, 23 °C).

As polysaccharide aggregates could be retained by filtration (through 0.45 μm), final concentrations could be changed, and thus the recovery rates of flaxseed RG-I before and after filtration were calculated. The recovery rates of FK-R after 4-time filtration in Milli-Q water, 0.1 M NaNO3, and 6 M NH4OH were 64.7 ± 5.2%, 79.8 ± 0.3%, and 84.4 ± 0.7%, respectively. The recovery rates of FM-R and FK-R in 0.5 M NaOH both were >95%.

The molecular size distributions of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) ranged from 20~600 nm in either 0.1 M NaCl (Figure 3A) or 0.5 M NaCl solutions (data not shown), and those in 0.1 M and 0.5 M NaOH solutions ranged from approximately 20 to 120 nm (Figure 3B) and from approximately 20 to 90 nm (Figure 3C), respectively. The mean hydrodynamic radius (Rh) reduced from 77 to 56 nm with an NaCl concentration increased from 0.1 M to 0.5 M; however, they were still much higher than those in 0.1 M or 0.5 M NaOH (~29 nm). Both of the 0.1 M and 0.5 M NaOH solution showed a stable mean Rh after filtration, while the gradual increases in the mean Rh from approximately 29 to 63 nm were detected within 6 h after filtration at higher concentrations (>0.5 mg/mL). The latter (i.e., 0.5 M NaOH) showed a better prevention of FM-R molecular aggregates in the solution, and no obvious degradation was detected within 24 h.

The molecular size distributions of the flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R) ranged from approximately 30 to 200 nm in the 0.1 M NaNO3 solution (Figure 3D), from approximately 30 to 80 nm in the 6 M NH4OH solution (Figure 3E), and from approximately 20 to 90 nm in the 0.5 M NaOH solution (Figure 3F). However, the lower mean Rh of FK-R in 0.5 M NaOH might be due to the mild hydrolysis of FK-R molecules, which was confirmed by the relatively higher polydispersity in the solution (Figure 3F). It is worth noting that relatively larger molecular aggregates (~5000 nm) were also observed in the 0.5 M KOH solution (Figure S1B), which might be caused by potassium ion-mediated aggregation, which requires further investigation.

As FK-R was more sensitive to alkali degradation, the stability of FK-R in 6 M NH4OH (stored in airtight containers at 23 °C) was also evaluated based on molecular size distribution (Figure S2A) and mean Rh (Figure S2B), which revealed that FK-R was relatively stable during 48 h storage. Moreover, the mean Rh was confirmed to be independent of the light scattering angle (Figure S3A) or RG-I concentration (Figure S3B).

3.2. Static Light Scattering (SLS) Analysis

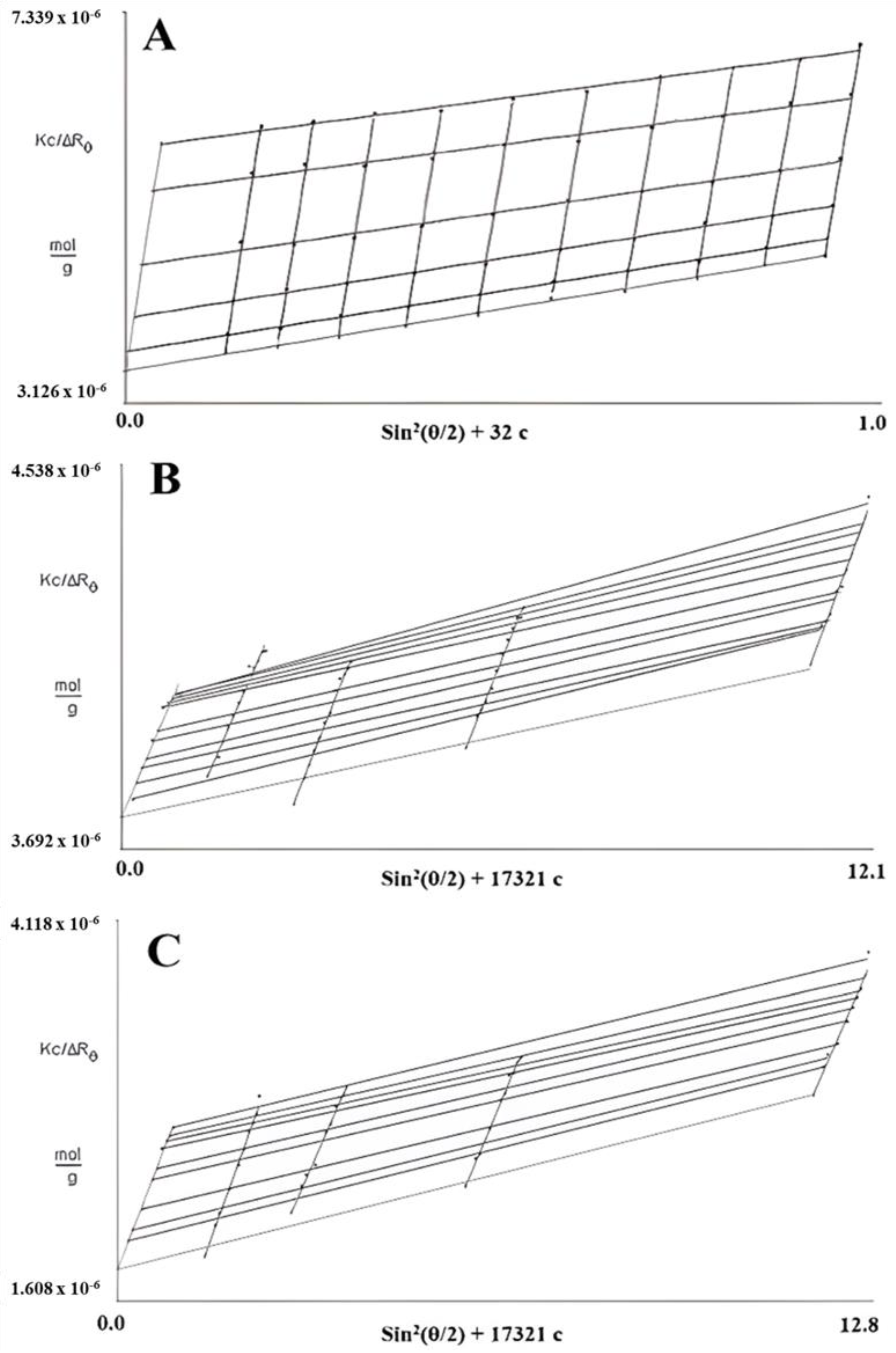

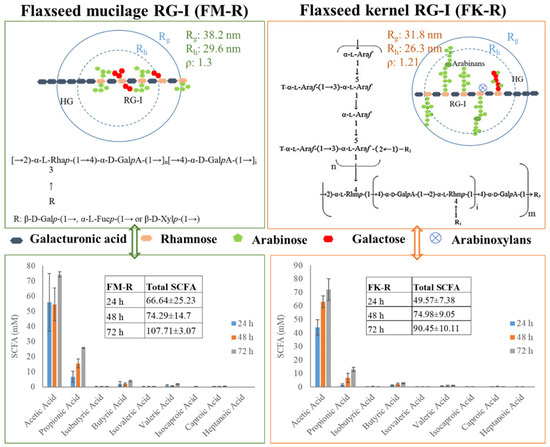

In SLS measurements, 0.5 M NaOH was selected for FM-R characterization, and two solutions (i.e., 0.5 M NaOH and 6 M NH4OH) were selected to characterize and compare the conformational characteristics of FK-R. As presented in Figure 4, the Zimm plot reveals the correlation between the radius of the gyration (Rg), weight average molecular weight (Mw), and concentration (c) of flaxseed RG-I solutions. The slope of angular dependence (θ) at c = 0 refers to the mean square radius of gyration (Rg2); the initial slope of concentration dependence at θ = 0 refers to the second virial coefficient multiplying by 2 (2A2); and the interception (θ = 0 and c = 0) refers to reciprocal molecular weight (1/Mw) [14].

Figure 4.

Zimm plots of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) in 0.5 M NaOH (A), and flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R) in 0.5 M NaOH (B) or 6 M NH4OH (C) determined by static light scattering (at various solution concentrations, 23 °C).

Based on the Zimm pilots of FM-R (Figure 4A) and FK-R in 0.5 M NaOH (Figure 4B) or in 6 M NH4OH (Figure 4C), the A2 was 9.3, 2.6, and 6.4, respectively. The positive A2 value indicates that the interaction between the molecule and the solvent is more favorable than molecular interactions in the solution (i.e., aggregation). The Mw of FM-R and FK-R was calculated to be 285 kDa and 550 kDa, respectively, and the mean Rg of FM-R and FK-R was 38.2 nm and 31.8 nm, respectively. It should be noted that not all light scattering conditions were selected in the Zimm plots analyses of FK-R solutions, as there might be some invisible scratches of the containers (i.e., quartz cuvettes) during SLS analyses, which lowered the accuracy at certain angles; instead, more FK-R concentrations were prepared, and more solvents were compared for reliable characterization.

3.3. Conformational Characteristics of Flaxseed RG-I

The conformational characteristics of FM-R and FK-R from DLS, SLS, or HPSEC analyses are summarized in Table 1. The Mw of FM-R was calculated to be 285 kDa by static light scattering analysis. There were two peaks in the elution profiles from HPSEC, with Mw of 1510 and 341 kDa, respectively. The higher-Mw fraction should be FM-R aggregates formed in 0.1 M NaNO3 (i.e., HPSEC eluent), which was confirmed by light scattering analyses. The structure-sensitive parameter (ρ) value of FM-R was 1.3, suggesting that the FM-R molecule had a star-like conformation.

Table 1.

Conformational characteristics of flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-RGI) and flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-RGI).

The Mw of FK-R was calculated to be 550 kDa from SLS, and the ρ value was 1.21 in a good solvent (i.e., 6 M NH4OH). FK-R had a longer branch and a higher percentage of “hairy region” than FM-R, and the conformation of FK-R was less extended than FM-R. The conformational characteristic of FK-R in 0.5 M NaOH (Table 1) also confirmed that FK-R was partially hydrolyzed. The Mw (266 kDa) was reduced by 52%, and the hydrolyzed FK-R molecule formed sphere-like conformation (ρ = 0.72). The intrinsic viscosity ([η]) was determined by the Ubbelohde viscometer at 23 °C (Equations (1)–(5)). The [η] of FK-R in 6 M NH4OH was 63 mL/g, which was much lower than that of FM-R in 0.1 M NaCl (333 mL/g). The correlation between [η] and the conformation of flaxseed RG-I is discussed in the following sections.

The HPSEC elution profile of FK-R is presented in Figure S4. The Mw of FK-R was calculated to be 596 kDa by the light scattering detectors (at 7° and 90°) coupled with HPSEC, which was comparable with the batch-mode multi-angle SLS result (i.e., 550 kDa). As FK-R had much lower uronic acid contents (14.59%, w/w) than FM-R (38.7%, w/w) [5,8], 0.1 M NaNO3 solution might better shield the electrostatic effects of FK-R molecules than FM-R under a relatively higher temperature and shear force in the HPSEC columns, and no aggregation was observed in the elution profile of FK-R.

HPSEC provides a fast and high-throughput option to separate the polymer fractions and evaluate the structural characteristics. However, there are still several shortcomings of the HPSEC technique: (1) there is a limited option of eluent, which is mainly dependent on the column packing material and detectors; (2) the polydispersity of polymer fractions or other mixtures, especially those within close molecular weight ranges, which could largely affect the accuracy of HPSEC results; and (3) the characterization of the primary structure (e.g., chemical composition, linkage type, backbone, branch, etc.) or some correlated analyses (e.g., intrinsic viscosity, critical concentration, rheology, etc.) should be recommended, in order to better estimate the conformational characteristics and compensate potential errors from HPSEC analyses.

3.4. Correlation between Primary Structure and Conformation, and Structure–Function Relationship of Flaxseed RG-I

The correlations between structure-sensitive parameter (ρ) value and polymer conformation have been extensively summarised in previous publications [13,14,15]. In general, the ρ value decreases with the increasing branching density of a polymer molecule: homogeneous sphere conformation (ρ = 0.788); sphere to star-like (longer branched) conformation (ρ = 0.788~1.33); star-like (shorter branched) to random coil conformation (ρ = 1.33~1.73); randomly branched conformation (ρ = 1.73~2.00); and rigid rod conformation (ρ > 2.00). It should be noted that the types of solvent and polymer polydispersity could affect the correlations.

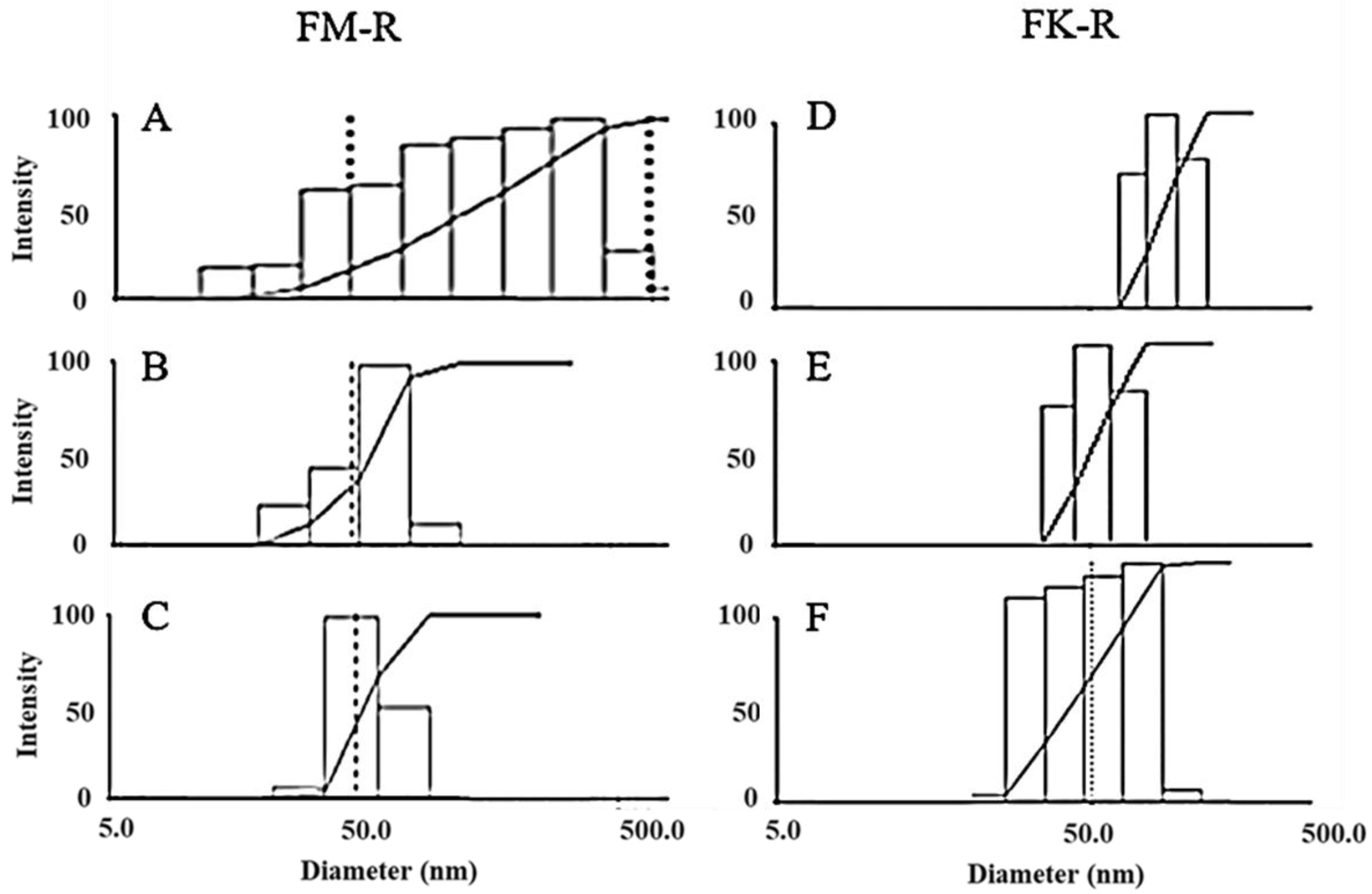

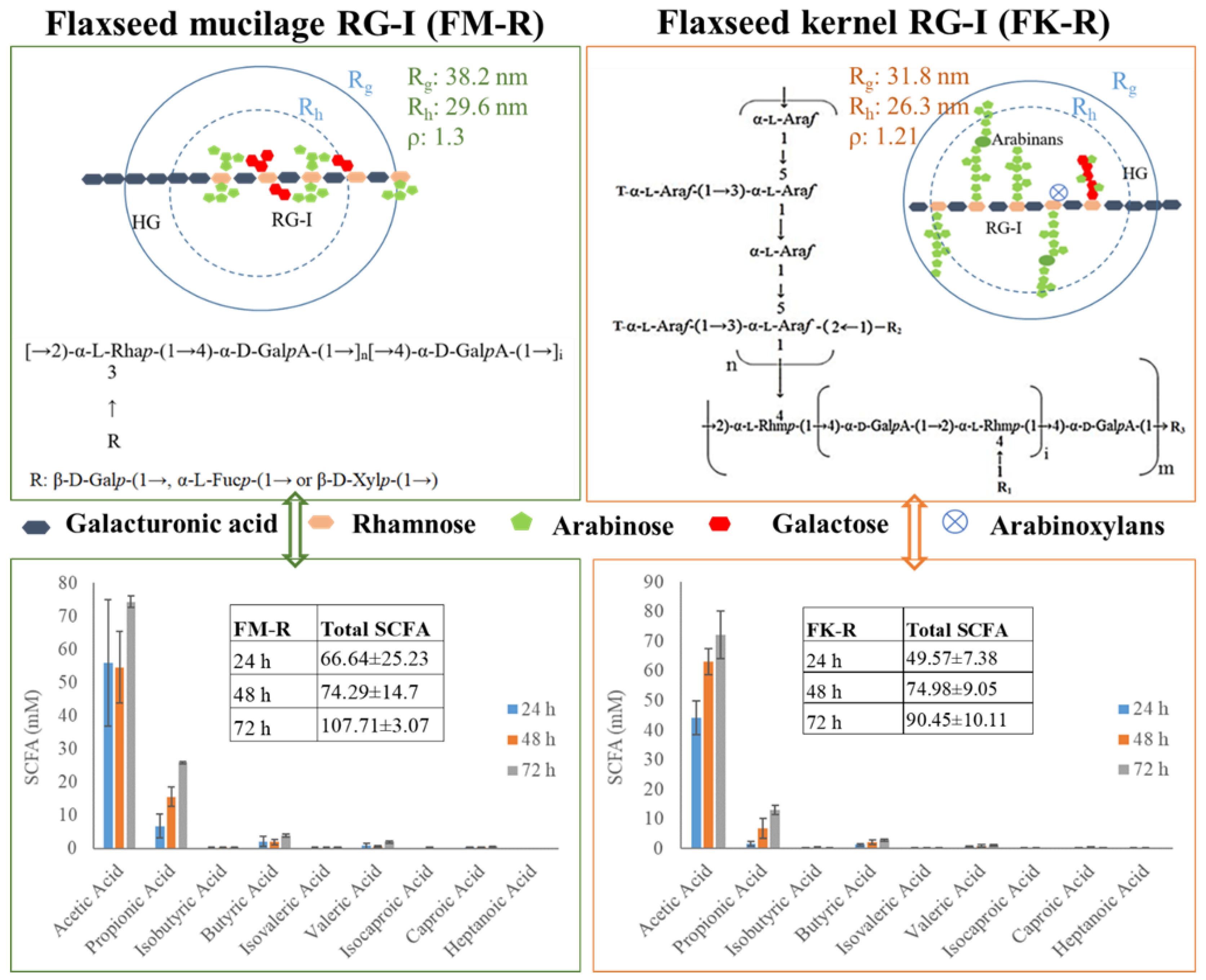

As presented in Figure 5, the ρ value of FM-R was 1.3, with Rg 38.2 nm and Rh 29.6 nm. The branches in the RG-I backbone were composed of shorter side chains, e.g., β-D-Galp-(1→, α-L-Fucp-(1→ or β-D-Xylp-(1→ residue. FM-R had relatively higher uronic acid contents (38.7%, w/w), indicating a longer homogalacturonans (HG) region compared with FK-R. The ρ value of FK-R ranged from 0.90 to 1.21, and the branches in the FK-R backbone were composed of highly branched and much longer arabinans (i.e., 30~90 arabinofuranose units), suggesting the sphere to star-like conformation and relatively higher segment density.

Figure 5.

The correlation between the primary structure and conformation of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) and flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R), and the correlation between the structure/conformation and SCFA profiles after in vitro fermentation; the structure of flaxseed RG-I fractions were reproduced from the results of previous studies [4,5]; SCFA profiles were reproduced from previous results [19].

The ρ value of FK-R was comparable to the water soluble soybean polysaccharide (SSPS), which was calculated to be 1.1 [16]. Both FK-R and SSPS were extracted from the cotyledons of oilseed, and they shared some common structural characteristics, such as RG-I backbone, lower uronic acid contents, and long neutral side chains [5,17]. The highly branched structure contributes to the sphere of star-like conformation, which shows a relatively lower viscosity compared to citrus pectin (i.e., HG) and has excellent emulsifying capacities to stabilize acidic dairy beverages or plant-based milks. The linkage patterns of arabinans (mainly hydrolyzed from RG-I) of different plant origin, such as legume (e.g., pea, cowpea, pigeon pea, mung bean), oilseeds (e.g., flaxseed, rapeseed, soybean, olive), vegetable (e.g., cabbage, sugar beet, carrot), and fruits (e.g., apple, grape, pear), have been summarised in earlier studies [5]. Other than SSPS, the similarity in the primary structure of oilseed RG-I might contribute to some common conformational characteristics, and further studies are still required.

As aforementioned, the intrinsic viscosity ([η]) of FK-R in 6 M NH4OH or 0.1 M NaNO3 (59~63 mL/g) was much lower than that of FM-R in 0.1 M NaCl (i.e., 333 mL/g). It confirmed that FM-R (with shorter side chains) were more extended than FK-R. The [η] reflects hydrodynamic volume occupied by a polymer molecule, which is inversely proportional to molecular density, and the [η] value mainly depends on the molecular weight, chain rigidity, and solvent [18]. As RG-I molecules carry charges, the force of electrostatic expansion becomes more dominant in water or diluted salt solutions; moreover, the potential molecular aggregation also contributes to the increase in intrinsic viscosity.

The short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) profiles of FK-R and FM-R are presented in Figure 5, which were evaluated through the in vitro fermentation of pig colonic digesta [19]. Compared with psyllium fibre (i.e., arabinoxylan), flaxseed RG-I were relatively slower fermentable dietary fibres, but they had a higher level of total SCFA production than psyllium fibres after 72 h incubation. FM-R and FK-R showed similar trends in acetic acid and propionic acid production, while the cultures grown with FM-R had a higher level of SCFA production. The results indicate the uronic acid content, substitution, degree of branch, side chains, molecular weight, and conformation of dietary fibres might impact the SCFA generation and fermentation rate. The structural–conformational–functional relationships of pectin from various sources, e.g., sugar beet, citrus pectin, flaxseed, and molecular simulation [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], are summarized in Table 2. For example, the conformational properties of RG-1 or HG under different extraction and processing conditions were also compared, e.g., alkali-extracted pectins displayed a three-dimensional structure and compact folded conformation while acid-extracted pectins possessed a relatively extended conformation [22]. Moreover, ultrasound degradation changed the structural and conformational characteristics of citrus pectin, which significantly influenced its functional properties [23]. The effects of the side chain on the conformational properties of RG-I in both solution and gel have been studied and longer side chains were associated with increased entanglements for pectin molecules [24]. Using the molecular modeling method, the location and degree of acetylation on the conformation of both RG-I and RG-II were investigated, from which acetyl groups at both O-2 and O-3 of galacturonic acid in the backbone of RG-I and HG were energetically favourable [30].

Table 2.

Structural–conformational–functional relationships of pectins from various plant origins.

As non-starch polysaccharides cannot be hydrolyzed by human digestive enzymes, the influence of pH, dilution factor, and/or shear rate (in the GI tract) on the conformational characteristics in vivo still requires further studies. The high throughput characterizations (e.g., multi-detector HPSEC with improved column material, and conformational modelling by supercomputer), as well as the establishment of polysaccharide structural database, may help better predict conformational characteristics for various scenarios.

4. Conclusions

The molecular size distributions of flaxseed mucilage RG-I (FM-R) ranged from approximately 20 to 90 nm in 0.5 M NaOH solutions with a mean hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of 29.6 nm, and the molecular size distributions of the flaxseed kernel RG-I (FK-R) ranged from approximately 30 to 80 nm in 6 M NH4OH solution with a mean Rh of 26.3 nm. The weight average molecular weight (Mw) of FM-R and FK-R was calculated to be 285 kDa and 550 kDa, respectively, and the mean radius of gyration (Rg) of FM-R and FK-R was 38.2 nm and 31.8 nm, respectively. The structure-sensitive parameter (ρ) value of FM-R was calculated as 1.3, suggesting that FM-R molecules had star-like conformation, while FK-R molecules had a relatively higher segment density showing sphere to star-like conformation. Based on short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profiles after in vitro fermentation, the primary structure (e.g., monosaccharide composition, uronic acid content, substitution, degree of branch, or side chains) and conformational characteristics (e.g., molecular weight or molecular shape) all impacted the SCFA generation and fermentation rate. In addition, the structural–conformational–functional relationships of pectin from various sources, e.g., sugar beet, citrus pectin, flaxseed, and molecular simulation, are also summarized. The correlations, such as the effects of the side chain (galactan chain), the location and degree of acetylation, and the extraction/processing conditions on the conformation of both RG-I and RG-II, helps better understand pectins at the molecular level, and could guide scale-up the applications of pectins from various plant sources.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polym14132667/s1, Figure S1: Molecular size distribution of flaxseed kernel RG-I: (A) Milli-Q water, and (B) 0.5 M KOH determined by dynamic light scattering (concentration: 0.1 mg/mL, temperature: 23 °C); Figure S2: Stability of flaxseed kernel RG-I in 6 M NH4OH: (A) HPSEC elution profile of KPI-ASF dissolving in 6 M NH4OH after 0 h, 24 h & 48 h (concentration: 1 mg/mL), and (B) hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of KPI-ASF dissolving in 6 M NH4OH after 1 h, 2 h, 4h, 24 h, & 48 h (concentration: 0.1 mg/mL); Figure S3: The mean hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of flaxseed mucilage RG-I: (A) the angular dependence (concentration: 0.2 mg/L) and (B) concentration dependence (at 90°) tests; Figure S4: HPSEC elution profile of flaxseed kernel RG-I in 0.1 M NaNO3 (concentration: 1 mg/mL, temperature: 40 °C).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G. and H.H.D.; methodology, K.Q. and H.H.D.; formal analysis, Q.G., K.Q. and H.H.D.; investigation, Q.G., Z.S. and H.H.D.; data curation, Q.G., Z.S., Y.S., K.Q. and H.H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G., Z.S., N.W. and H.H.D.; writing—review and editing, Q.W., S.W.C. and H.H.D.; supervision, Q.G., S.W.C., H.D.G. and H.H.D.; funding acquisition, Q.G. and N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Cathy Wang and Tracy Guo at Agricultural and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) for their technical assistance. The funding supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 32072173 and 32101901) and Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Program (21ZYQCSY00050) are also highly appreciated.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Morris, D.H. Flax—A Health and Nutrition Primer, 4th ed.; Flax Council of Canada: Winnipeg, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.H.; Cui, S.W.; Goff, H.D.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Han, N.F. Soluble polysaccharides from flaxseed kernel as a new source of dietary fibres: Extraction and physicochemical characterization. Food Res. Int. 2014, 56, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.W.; Mazza, G.; Biliaderis, C.G. Chemical Structure, Molecular Size Distributions, and Rheological Properties of Flaxseed Gum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 429, 1891–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.Y.; Cui, S.W.; Nikiforuk, J.; Goff, H.D. Structural elucidation of rhamnogalacturonans from flaxseed hulls. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 362, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.H.H.; Cui, S.W.; Goff, H.D.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Han, N.F. Arabinan-rich rhamnogalacturonan-I from flaxseed kernel cell wall. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 47, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.H.; Cui, S.W.; Goff, H.D.; Chen, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Q. Xyloglucans from flaxseed kernel cell wall: Structural and conformational characterisation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.H.; Qian, K.; Goff, H.D.; Wang, Q.; Cui, S.W. Structural and conformational characterization of arabinoxylans from flaxseed mucilage. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.Y.; Cui, S.W.; Wu, Y.; Goff, H.D. Flaxseed gum from flaxseed hulls: Extraction, fractionation, and characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 282, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 283, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, M.L. The Viscosity of Dilute Solutions of Long-Chain Molecules. IV. Dependence on Concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1943, 6411, 2716–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, E.O. Molecular weights of celluloses and cellulose derivates. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1938, 3010, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimm, B.H. Apparatus and Methods for Measurement and Interpretation of the Angular Variation of Light Scattering; Preliminary Results on Polystyrene Solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1948, 1612, 1099–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchard, W. Light Scattering from Polysaccharides. In Polysaccharides: Structural Diversity and Functional Versatility, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.W.; Wang, Q. Understanding the conformation of polysaccharides. In Food Carbohydrates; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burchard, W. Light scattering techniques. In Polysaccharides: Physical Techniques for the Study of Food Biopolymers; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 151–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Nakamura, A.; Burchard, W.; Hallett, F.R. Molecular characterisation of soybean polysaccharides: An approach by size exclusion chromatography, dynamic and static light scattering methods. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 34017, 2637–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akihiro, N.; Hitoshi, F.; Hirokazu, M.; Yasunori, N.; Akihiro, Y. Analysis of Structural Components and Molecular Construction of Soybean Soluble Polysaccharides by Stepwise Enzymatic Degradation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 6510, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.W. Food carbohydrates. Structure analysis of polysaccharides. In Food Carbohydrates; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.H.H.; Cui, S.W.; Goff, H.D.; Gong, J. Short-chain fatty acid profiles from flaxseed dietary fibres after in vitro fermentation of pig colonic digesta: Structure–function relationship. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 2015, 62, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.F.; Zhao, C.Y.; Zhao, S.J.; Tian, G.F.; Wang, F.; Li, C.H.; Wang, F.Z.; Zheng, J.K. Alkali + cellulase-extracted citrus pectins exhibit compact conformation and good fermentation properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 106079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.F.; Wang, F.; Zhao, C.Y.; Zhou, S.S.; Zheng, J.K. Orange Pectin with Compact Conformation Effectively Alleviates Acute Colitis in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 705, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Ren, W.; Zhao, C.; Gao, W.; Tian, G.; Bao, Y.; Lian, Y.; Zheng, J. The structure-property relationships of acid- and alkali-extracted grapefruit peel pectins. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qiu, W.Y.; Chen, T.T.; Yan, J.K. Effects of structural and conformational characteristics of citrus pectin on its functional properties. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 128064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.G.; Nielsen, H.L.; Armagan, I.; Larsen, J.; Sørensen, S.O. The impact of rhamnogalacturonan-I side chain monosaccharides on the rheological properties of citrus pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 47, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Q.; Chen, J.L.; Zhang, H.L.; Wu, D.M.; Ye, X.Q.; Linardt, R.J.; Chen, S.G. Gelling mechanism of RG-I enriched citrus pectin: Role of arabinose side-chains in cation- and acid-induced gelation. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.X.; Qi, J.R.; Huang, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.Q. Emulsifying properties of high methoxyl pectins in binary systems of water-ethanol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, R.H.; Wang, L.H.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.M. Alkylated pectin: Synthesis, characterization, viscosity and emulsifying properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 50, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Guo, X.J.; Liang, R.H.; Liu, W.; Chen, J. Alkylated pectin: Molecular characterization, conformational change and gel property. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 69, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cros, S.; Penhoat, C.H.; Bouchemal, N.; Ohassan, H.; Imberty, A.; Pérez, S. Solution conformation of a pectin fragment disaccharide using molecular modelling and nuclear magnetic resonance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1992, 146, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouwijzer, M.; Schols, H.; Pérez, S. Acetylation of rhamnogalacturonan I and homogalacturonan: Theoretical calculations. Biotechnol. Prog. 1996, 14, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst, M.; Cros, S.; Hoffmann, R.; Mackie, W.; Pérez, S. Modelling a pentasaccharide fragment of rhamnogalacturonan I. Biotechnol. Prog. 1996, 14, 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- Boutherin, B.; Mazeau, K.; Tvaroska, I. Conformational statistics of pectin substances in solution by a Metropolis Monte Carlo study. Carbohydr. Polym. 1997, 323, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurjanov, O.P.; Gorshkova, T.A.; Kabel, M.; Schols, H.A.; van Dam, J.E.G. MALDI-TOF MS evidence for the linking of flax bast fibre galactan to rhamnogalacturonan backbone. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 671, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromer, A.; Kirby, A.R.; Gunning, A.P.; Morris, V.J. Interfacial structure of sugar beet pectin studied by atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 2009, 2514, 8012–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.A.; Ralet, M.C. The effect of neutral sugar distribution on the dilute solution conformation of sugar beet pectin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 884, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, G.A.; Ralet, M.C.; Bonnin, E.; Thibault, J.F.; Harding, S.E. Physical characterisation of the rhamnogalacturonan and homogalacturonan fractions of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) pectin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 824, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bindereif, B.; Karbstein, H.P.; Zahn, K.; Schaaf, U.S. Effect of Conformation of Sugar Beet Pectin on the Interfacial and Emulsifying Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zareie, M.H.; Gokmen, V.; Javadipour, I. Investigating network, branching, gelation and enzymatic degradation in pectin by atomic force microscopy. J. Food Sci. Technol. Mys. 2003, 402, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Makshakova, O.N.; Gorshkova, T.A.; Mikshina, P.V.; Zuev, Y.F.; Perez, S. Metrics of rhamnogalacturonan I with beta-(1→4)-linked galactan side chains and structural basis for its self-aggregation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 158, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikshina, P.V.; Makshakova, O.N.; Petrova, A.A.; Gaifullina, I.Z.; Idiyatullin, B.Z.; Gorshkova, T.A.; Zuev, Y.F. Gelation of rhamnogalacturonan I is based on galactan side chain interaction and does not involve chemical modifications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 171, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikshina, P.V.; Idiyatullin, B.Z.; Petrova, A.A.; Shashkov, A.S.; Zuev, Y.F.; Gorshkova, T.A. Physicochemical properties of complex rhamnogalacturonan I from gelatinous cell walls of flax fibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makshakova, O.N.; Faizullin, D.A.; Mikshina, P.V.; Gorshkova, T.A.; Zuev, Y.F. Spatial structures of rhamnogalacturonan I in gel and colloidal solution identified by 1D and 2D-FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Zou, M.Y.; Shao, Y.C.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P. Structural characteristics of a highly branched and acetylated pectin from Portulaca oleracea L. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 116, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).