Influence of Deposition Conditions, Powder Feedstock, and Heat Treatment on the Properties of LP-DED NiTi Shape Memory Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, DED Process, and Heat Treatment

2.2. Microstructural, Chemical, and Phase Composition Characterization

2.3. Tensile and Superelastic Response Tests

2.4. Corrosion Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Powder Feedstocks

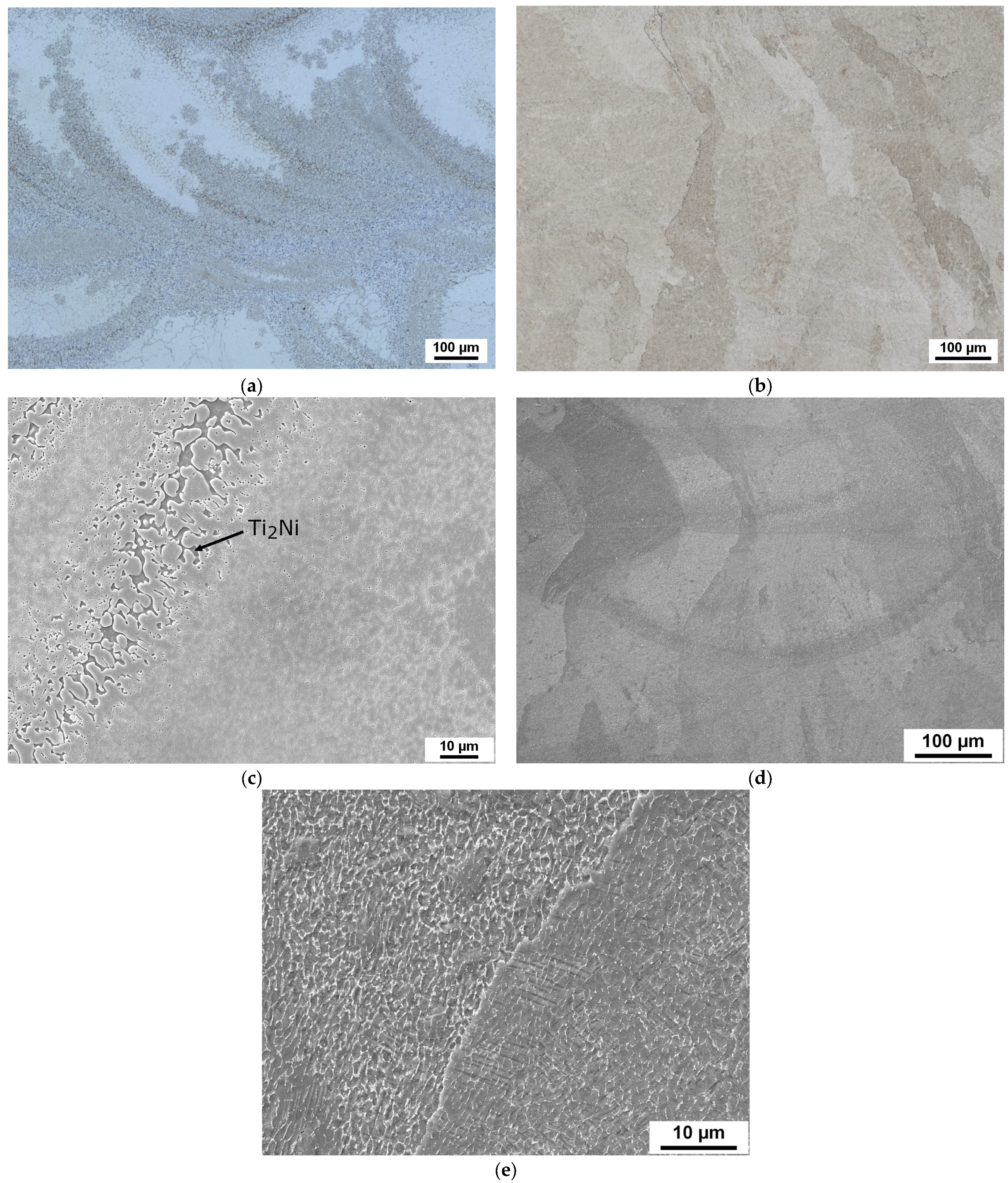

3.2. Deposition on Non-Heated Substrate

3.3. Deposition on Pre-Heated Substrate

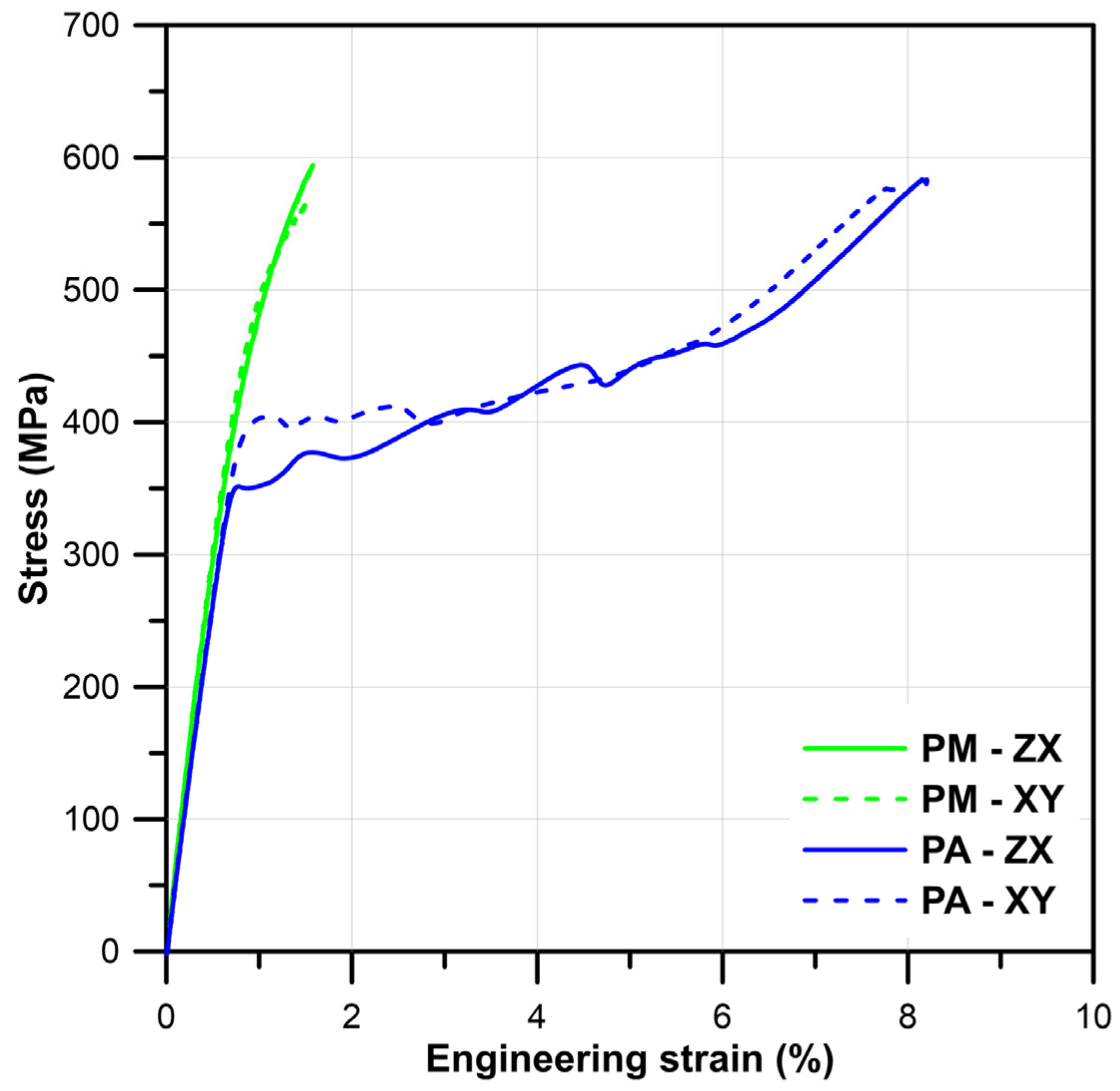

3.4. Tensile Test

3.5. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Superelastic Response

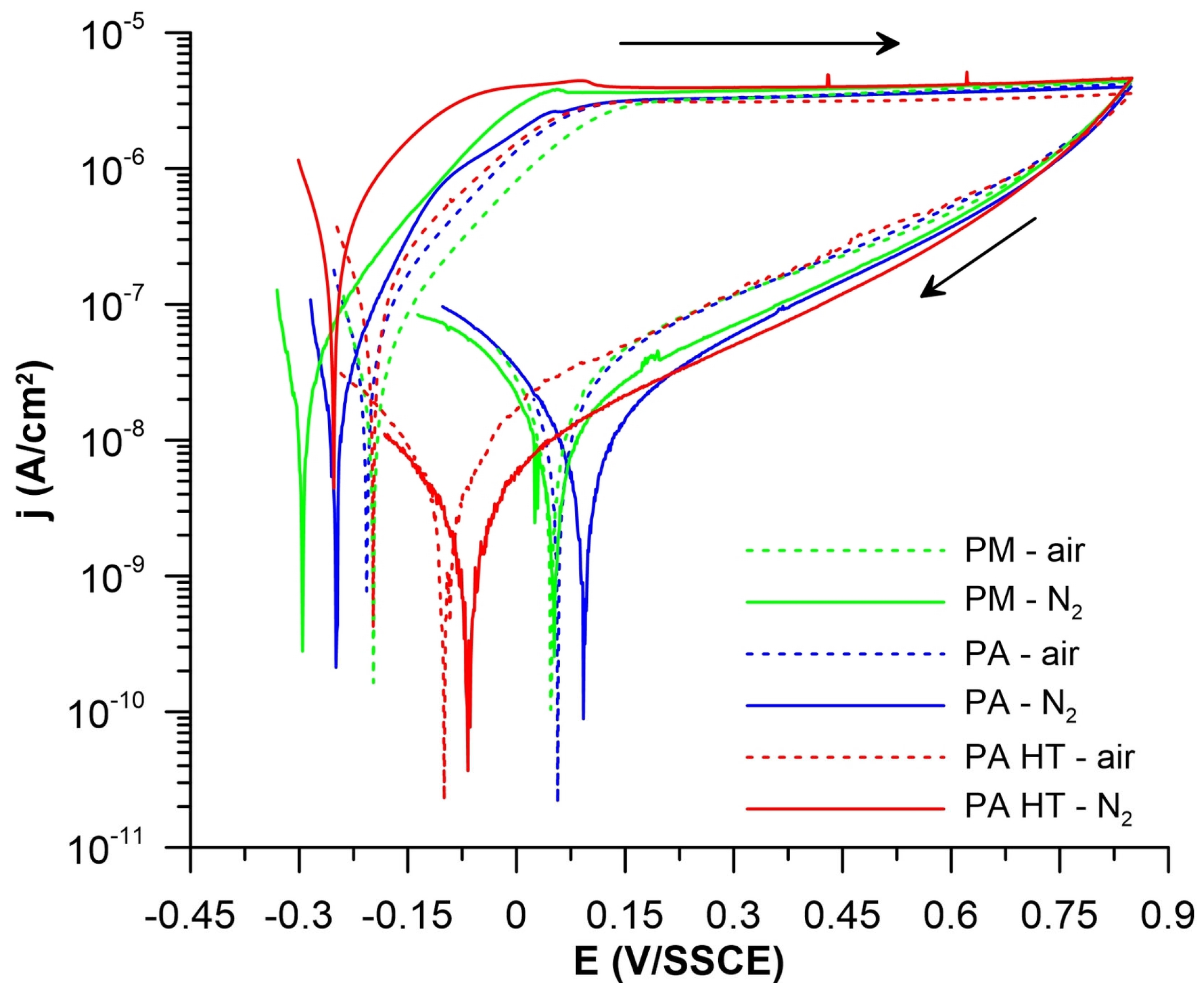

3.6. Corrosion Resistance Test

4. Conclusions

- DED fabrication using a blended elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture on a non-preheated titanium substrate proved to be unsuccessful due to severe warping, while deposition on a non-preheated NiTi substrate resulted in crack formation. To ensure process stability and crack-free fabrication, therefore, all subsequent samples were deposited onto a CP-Ti substrate preheated to 500 °C.

- The samples fabricated from the Ni and Ti elemental powder mixture contained a substantial fraction of the Ti2Ni secondary phase and exhibited significantly higher oxygen contents compared to samples produced from the pre-alloyed NiTi powder.

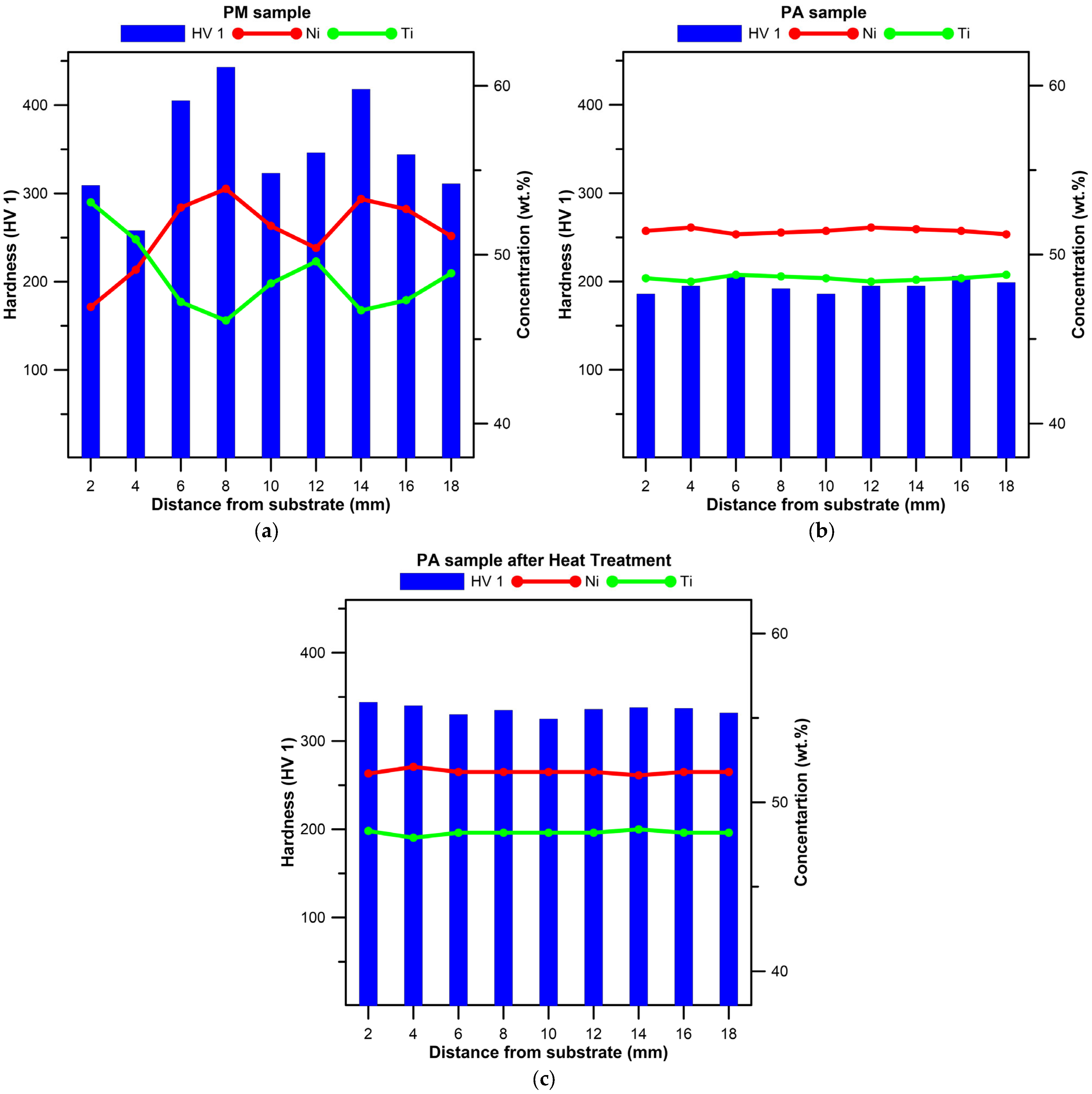

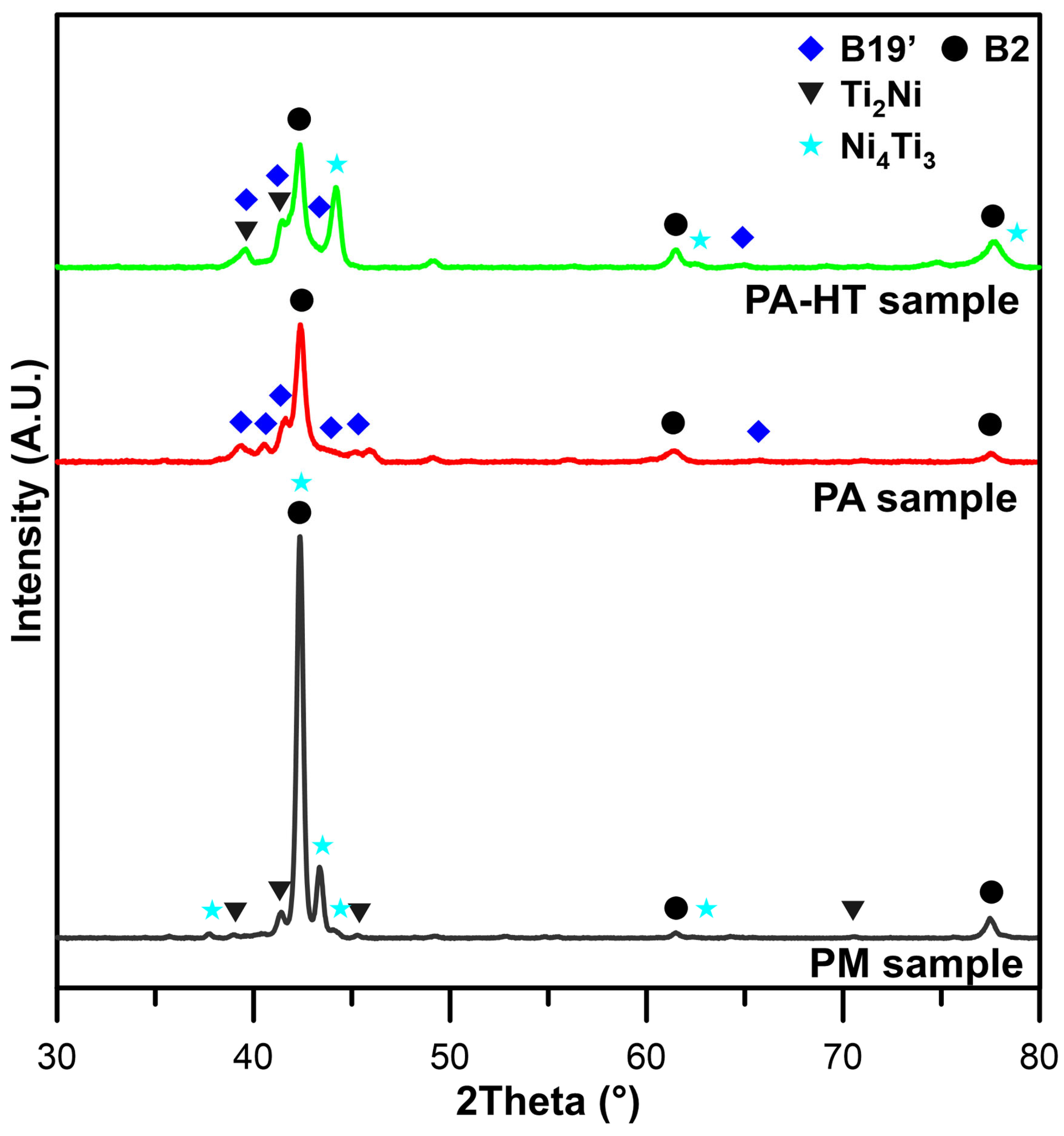

- Based on XRD analysis, the as-deposited samples fabricated from the elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture consisted of B2 austenite together with Ti2Ni and Ni4Ti3 phases, whereas the samples deposited from pre-alloyed NiTi powder contained only B2 and B19′ phases. After solution annealing followed by aging, the microstructure of the pre-alloyed material comprised B2, B19′, Ti2Ni and Ni4Ti3 phases. Samples deposited from pre-alloyed NiTi powder exhibited high chemical and hardness homogeneity along the build height, while samples fabricated from elemental powders showed pronounced fluctuations in both composition and hardness.

- The samples deposited from the elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture showed a limited total elongation to fracture of approximately 1.6% in the tensile stress–strain response without a superelastic plateau. In contrast, the samples fabricated from pre-alloyed NiTi powder exhibited a stress-induced martensitic transformation after exceeding a critical stress in the range of 350–400 MPa. The superelastic response was markedly enhanced by post-deposition heat treatment, with the recovery rate increasing from 53% in the as-built condition to 89% after heat treatment. To confirm the findings, a DSC analysis to determine Af temperature is needed.

- Overall, the results demonstrate that the powder processing route strongly influenced the corrosion performance of the NiTi alloys. Processing from elemental Ti and Ni powders led to superior corrosion resistance and reduced sensitivity to oxygen availability compared to those of pre-alloyed NiTi powder.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Otsuka, K.; Ren, X. Physical Metallurgy of Ti-Ni-Based Shape Memory Alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2005, 50, 511–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, J.; George, E.P.; Dlouhy, A.; Somsen, C.; Wagner, M.F.-X.; Eggeler, G. Influence of Ni on Martensitic Phase Transformations in NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 3444–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, M.; Corbin, S.F.; Gorbet, R.B. Investigation of the Influence of Ni Powder Size on Microstructural Evolution and the Thermal Explosion Combustion Synthesis of NiTi. Intermetallics 2009, 17, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, M.; Corbin, S.F.; Gorbet, R.B. Investigation of the Mechanisms of Reactive Sintering and Combustion Synthesis of NiTi Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry and Microstructural Analysis. Acta Mater. 2008, 56, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.L.; Sung, W.Y. Synthesis of NiTi Intermetallics by Self-Propagating Combustion. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 376, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, G.; Ozler, L.; Kaya, M.; Orhan, N. A Study on Microstructure and Porosity of NiTi Alloy Implants Produced by SHS. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 487, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Veselý, T.; Marek, I.; Dvořák, P.; Vojtěch, V.; Salvetr, P.; Karlík, M.; Haušild, P.; Kopeček, J. Effect of Particle Size of Titanium and Nickel on the Synthesis of NiTi by TE-SHS. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2016, 47, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetr, P.; Kubatík, T.F.; Pignol, D.; Novák, P. Fabrication of Ni-Ti Alloy by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis and Spark Plasma Sintering Technique. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2017, 48, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetr, P.; Dlouhý, J.; Školáková, A.; Průša, F.; Novák, P.; Karlík, M.; Haušild, P. Influence of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Properties of NiTi46 Alloy Consolidated by Spark Plasma Sintering. Materials 2019, 12, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Školáková, A.; Pignol, D.; Průša, F.; Salvetr, P.; Kubatík, T.F.; Perriere, L.; Karlík, M. Finding the Energy Source for Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis Production of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 181, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgalaka, M.N.; Pityana, S.L.; Popoola, P.A.I.; Mathebula, T. NiTi Intermetallic Surface Coatings by Laser Metal Deposition for Improving Wear Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Substrates. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 363917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-Y.; Rong, L.-J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Gjunter, V.E. Fabrication of Cellular NiTi Intermetallic Compounds. J. Mater. Res. 2000, 15, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, S.; Hashemi, S.M.; Asgarinia, F.; Nematollahi, M.; Elahinia, M. Effective Parameters on the Final Properties of NiTi-Based Alloys Manufactured by Powder Metallurgy Methods: A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubášová, K.; Drátovská, V.; Losertová, M.; Salvetr, P.; Kopelent, M.; Kořínek, F.; Havlas, V.; Džugan, J.; Daniel, M. A Review on Additive Manufacturing Methods for NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Production. Materials 2024, 17, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Hashmi, A.W.; Singh, J.; Arora, K.; Tian, Y.; Iqbal, F.; Al-Dossari, M.; Khan, M.I. Innovations in Additive Manufacturing of Shape Memory Alloys: Alloys, Microstructures, Treatments, Applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 4136–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Feng, Y.; Liu, B.; Xie, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, G. Regulation of Microstructure, Phase Transformation Behavior, and Enhanced High Superelastic Cycling Stability in Laser Direct Energy Deposition NiTi Shape Memory Alloys via Aging Treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 915, 147207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wang, J.; Di, T.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Niu, F.; Wu, D. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure, Phase Transformation Behavior and Shape Memory Effect of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Manufactured by Additive Manufacturing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1035, 181340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Di, T.; Yan, X.; Niu, F.; Wu, D. Phase Transformation Behavior and Mechanical Properties of NiTi Shape Memory Alloys Fabricated by Directed Laser Deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 908, 146693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.M.; Svetlizky, D.; Das, M.; Tevet, O.; Krämer, M.; Kim, S.; Gault, B.; Eliaz, N. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Bulk NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Fabricated Using Directed Energy Deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 86, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Cao, H.; Xie, J.; Yin, F. Damping and Compressive Properties of SLM-Fabricated Rhombic Dodecahedron-Structured Ni–Ti Shape Memory Alloy Foams. Metals 2025, 15, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Cong, W. Excellent Damping Properties and Their Correlations with the Microstructures in the NiTi Alloys Fabricated by Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mann, W.; Lan, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, X.; He, B. Effect of Pre-Mixed Powders on the Microstructure and Superelasticity of Laser Directed Energy Deposited NiTiCu Shape Memory Alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 5996–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska, A. NiTi in Situ Alloying in Powder-Based Additive Manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Fan, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Teng, X. Microstructure and Elastocaloric Effect of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy In-Situ Synthesized by Laser Directed Energy Deposition Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Charact. 2024, 210, 113831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, W.-Y.; Chang, K.-C.; Wu, H.-F.; Chen, S.-W.; Yeh, A.-C. Formation Mechanism of Ni2Ti4O in NITI Shape Memory Alloy. Materialia 2019, 5, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska, A.; Wysocki, B.; Kwaśniak, P.; Kruszewski, M.J.; Michalski, B.; Zielińska, A.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B.; Krawczyńska, A.; Buhagiar, J.; Święszkowski, W. Heat Treatment of NiTi Alloys Fabricated Using Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) from Elementally Blended Powders. Materials 2022, 15, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, S.; Palani, I.A.; Mishra, S.K.; Paul, C.P.; Kukreja, L.M. Investigations on the Influence of Composition in the Development of Ni–Ti Shape Memory Alloy Using Laser Based Additive Manufacturing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2015, 69, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Cong, W. Multi-Scale Pseudoelasticity of NiTi Alloys Fabricated by Laser Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 821, 141600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahinia, M.; Shayesteh Moghaddam, N.; Taheri Andani, M.; Amerinatanzi, A.; Bimber, B.A.; Hamilton, R.F. Fabrication of NiTi through Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 83, 630–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.F.; Palmer, T.A.; Bimber, B.A. Spatial Characterization of the Thermal-Induced Phase Transformation throughout as-Deposited Additive Manufactured NiTi Bulk Builds. Scr. Mater. 2015, 101, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkiewicz, J.; Rogal, Ł.; Kalita, D.; Kawałko, J.; Węglowski, M.S.; Kwieciński, K.; Śliwiński, P.; Danielewski, H.; Antoszewski, B.; Cesari, E. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Martensitic Transformation in NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Fabricated Using Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing Technique. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hou, H.; Huang, A.; Chen, F. Thermodynamic Ripening Induced Multi-Modal Precipitation Strengthened NiTi Shape Memory Alloys by Directed Energy Deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 92, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kang, N.; Wang, P.; El Mansori, M. Thermal Effects on Wear Behavior of Additively Manufactured NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-N.; Zhu, W.; Borisov, E.; Yao, X.; Riemslag, T.; Goulas, C.; Popovich, A.; Yan, Z.; Tichelaar, F.D.; Mainali, D.P.; et al. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Functional Properties of Additively Manufactured NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 967, 171740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Contreras-Almengor, O.; Ordoño, J.; Aguilar Vega, C.; Zapata Martínez, R.; Echeverry-Rendón, M.; Díaz-Lantada, A.; Molina-Aldareguia, J. The Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Nitinol Manufactured by LPBF: Differences between Ni-Rich and Ti-Rich Compositions. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2476006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastuti, K.; Hamzah, E.; Hashim, J. Effect of Annealing on the Microstructures and Deformation Behaviour of Ti–50.7at.%Ni Shape Memory Alloy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2016, 230, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, Y. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of NiTi Shape Memory Alloys Fabricated by Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 892, 162193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrami, M.B.; Tocci, M.; Brabazon, D.; Cabibbo, M.; Pola, A. Effects of Direct Aging Heat Treatments on the Superelasticity of Nitinol Produced via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2024, 55, 3889–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S.; Turabi, A.S.; Taheri Andani, M.; Haberland, C.; Karaca, H.; Elahinia, M. The Influence of Heat Treatment on the Thermomechanical Response of Ni-Rich NiTi Alloys Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 677, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, L.; Yang, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. High-Superelasticity NiTi Shape Memory Alloy by Directed Energy Deposition-Arc and Solution Heat Treatment. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2024, 37, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristianová, E.; Novák, P. Composite Materials NiTi-Ti2Ni. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 16, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, M.; Annamalai, A.R.; Muthuchamy, A.; Jen, C.-P. A Review of the Latest Developments in the Field of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Crystals 2021, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adharapurapu, R.R.; Jiang, F.; Vecchio, K.S. Aging Effects on Hardness and Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Ti–55Ni (at.%) Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Du, D.; Zhang, D.; Xi, R.; Wang, X.; Chang, B. Study on the Role of Carbon in Modifying Second Phase and Improving Tensile Properties of NiTi Shape Memory Alloys Fabricated by Electron Beam Directed Energy Deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 75, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Hayat, M.D.; Chen, G.; Cai, S.; Qu, X.; Tang, H.; Cao, P. Selective Electron Beam Melting of NiTi: Microstructure, Phase Transformation and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 744, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liang, T.; Wang, C.; Dong, L. Surface Corrosion Enhancement of Passive Films on NiTi Shape Memory Alloy in Different Solutions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 63, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, H.-H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.-Q. Influence of Ni4Ti3 Precipitation on Martensitic Transformations in NiTi Shape Memory Alloy: R Phase Transformation. Acta Mater. 2021, 207, 116665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ren, D.; Ji, H.; Ma, A.; Daniel, E.F.; Li, S.; Jin, W.; Zheng, Y. Study on the Corrosion Behavior of NiTi Shape Memory Alloys Fabricated by Electron Beam Melting. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferi, D.; Hybášek, V.; Novák, P.; Fojt, J. Corrosion Behaviour of the NiTiX (X = Si, Mg, Al) Alloy Prepared by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. Koroze a Ochr. Mater. 2021, 65, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojt, J.; Alferi, D.; Hybasek, V.; Edwards, D.W.; Laasch, H.-U. Corrosion Failure of Nitinol Stents in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract: The Role of Surface Finishes and the Importance of an Appropriate Test Environment. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 309, 128390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element (wt.%) | C | N | O | H | Fe | Co | Cu | Nb | Cr | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | <0.01 | X | 0.22 | X | 0.21 | X | X | X | X | Ni |

| Ti | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.002 | 0.04 | X | X | X | X | Ti |

| NiTi | 0.04 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 55.75wt.% Ni; Ti balance |

| Designation | PM-1 | PM-2 | PM | PA | PA-HT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powder feedstock | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture | Pre-alloyed NiTi powder | Pre-alloyed NiTi powder |

| Deposition module | SDM400 | SDM400 | SDM800 | SDM800 | SDM800 |

| Substrate | Non-preheated CP-Ti | Non-preheated NiTi | Preheated CP-Ti | Preheated CP-Ti | Preheated CP-Ti |

| Protective atmosphere | Ar (full chamber) | Ar (full chamber) | Ar (meltpool shielding) | Ar (meltpool shielding) | Ar (meltpool shielding) |

| Heat Treatment | - | - | - | - | SA+A |

| Sample | PM-2 Cube | PM Cube | PA Cube | LPBF [26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deposition | DED | DED | DED | LPBF |

| Powder feedstock | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture | Pre-alloyed NiTi powder | Elemental Ni and Ti powder mixture |

| Protective atmosphere | Ar (full chamber) | Ar (meltpool shielding) | Ar (meltpool shielding) | Ar |

| Oxygen content (wt.%) | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.096 | 0.52 |

| Sample | Orientation | UPS | UTS | εf |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (MPa) | (%) | ||

| PM | ZX | X | 580 ± 30 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| XY | X | 571 ± 35 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | |

| PA | ZX | 408 ± 9 | 596 ± 13 | 8.2 ± 0.6 |

| XY | 405 ± 4 | 610 ± 33 | 10.3 ± 2.3 |

| Sample | Orientation | UPS | UTS | εf |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (MPa) | (%) | ||

| PA-HT | ZX | 399 ± 13 | 627 ± 5 | 6.1 ± 0.4 |

| XY | 361 ± 13 | 611 ± 14 | 6.7 ± 0.2 |

| Sample | Ecorr (mV/SSCE) | Rp (Ω·cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| PM air | −197 | 5.46 × 105 |

| PA air | −207 | 3.46 × 105 |

| PA-HT air | −198 | 1.82 × 105 |

| PM N2 | −295 | 5.69 × 105 |

| PA N2 | −268 | 3.72 × 105 |

| PA-HT N2 | −250 | 6.26 × 104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Salvetr, P.; Fousek, J.; Kubášová, K.; Fojt, J.; Brázda, M.; Drátovská, V.; Kratochvíl, A.; Losertová, M.; Havlas, V.; Daniel, M.; et al. Influence of Deposition Conditions, Powder Feedstock, and Heat Treatment on the Properties of LP-DED NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Crystals 2026, 16, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020098

Salvetr P, Fousek J, Kubášová K, Fojt J, Brázda M, Drátovská V, Kratochvíl A, Losertová M, Havlas V, Daniel M, et al. Influence of Deposition Conditions, Powder Feedstock, and Heat Treatment on the Properties of LP-DED NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Crystals. 2026; 16(2):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalvetr, Pavel, Jakub Fousek, Kristýna Kubášová, Jaroslav Fojt, Michal Brázda, Veronika Drátovská, Adam Kratochvíl, Monika Losertová, Vojtěch Havlas, Matej Daniel, and et al. 2026. "Influence of Deposition Conditions, Powder Feedstock, and Heat Treatment on the Properties of LP-DED NiTi Shape Memory Alloys" Crystals 16, no. 2: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020098

APA StyleSalvetr, P., Fousek, J., Kubášová, K., Fojt, J., Brázda, M., Drátovská, V., Kratochvíl, A., Losertová, M., Havlas, V., Daniel, M., & Džugan, J. (2026). Influence of Deposition Conditions, Powder Feedstock, and Heat Treatment on the Properties of LP-DED NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Crystals, 16(2), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020098