Abstract

A novel ternary transition metal chalcogenide Ba2Re6Se11, which crystallizes in the R−3c space group, was synthesized using a high-pressure and high-temperature technique. The lattice is constituted by Re6Se8 cube-octahedral clusters connected by additional apical Se anions via the Re-Se-Re pathway, while the Ba atoms reside in the cavities among the Re6Se8 units. High-pressure synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements showed that Ba2Re6Se11 maintains a trigonal structure up to a pressure of 60 GPa, with a bulk modulus of 193 GPa. The lattice stability is ascribed to the fully occupied valence bands of the molecular orbital of the Re6Se8 cluster with trivalent Re. This fully occupied orbital configuration also gives rise to the diamagnetic state of Ba2Re6Se11, which was validated through magnetic measurements. The resistivity of Ba2Re6Se11 is as low as several milliohm centimeters, and it follows the thermal activation mechanism at elevated temperatures and the three-dimensional variable-range hopping model at low temperatures, indicating that Ba2Re6Se11 is a semiconductor or insulator in close vicinity to a metal–insulator transition.

1. Introduction

Ternary transition metal chalcogenides have attracted intense attention due to their flexibility in forming versatile lattices including zero-dimensional nano particles [1], one-dimensional chains [2], two-dimensional van der Waals stacking layers [3], and three-dimensional (3D) networks [4]. Depending on the transition metals and lattice structures, ternary transition metal chalcogenides exhibit many physical properties and advanced functions such as superconductivity [5,6], semiconductivity [7], photovoltaic capability [8], energy storage [9,10], and electrocatalysis [11].

Among ternary transition metal chalcogenides, 3D ternary transition metal chalcogenides, which are constituted by transition-metal–chalcogen clusters, have important applications [12,13,14]. One of the famous examples is the Chevrel-phase superconductor AM6X8 (A = Pb, Ag, Sn, rare earth element, etc.), which has an elevated critical temperature up to 10 K and a remarkable critical magnetic field Hc2 over 40 T at 0 K [15,16]. Furthermore, 3D ternary transition metal chalcogenides also have potential applications in rechargeable batteries and electrocatalysis [17]. However, their disadvantages—including their time/energy-consuming synthesis processes and sensitivity to air—severely impede their further study [1,16].

The high-pressure synthesis technique utilizing a large-volume press (LVP) [18,19] offers a highly effective method for synthesizing ternary transition metal chalcogenides. These high-pressure conditions offer an additional degree of freedom to overcome the potential barrier of chemical reactions [20,21], providing a new pathway for producing novel transition metal chalcogenides [22,23]. Moreover, the LVP guarantees an environment isolated from air and reduces the reaction time, which is beneficial for materials that are sensitive to oxygen and humidity [24,25,26,27].

In this work, we successfully synthesized a novel 3D ternary transition metal chalcogenide, Ba2Re6Se11, under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions. It crystallizes into a trigonal structure with the space group R−3c, which is isostructural with its sulfide counterpart Ba2Re6Se11 [12,28,29]. The high-pressure synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements indicate that it maintains the trigonal lattice structure up to a pressure of 60 GPa, with a bulk modulus of 193 GPa. The crystallographic stability can be ascribed to the fully occupied molecular orbital of the Re6Se8 cube-octahedra, which also gives rise to the diamagnetic (DM) state of Ba2Re6Se11. On the other hand, the resistivity of Ba2Re6Se11 is as low as ~10 mΩ cm, and it follows the thermal activation mechanism at elevated temperatures and the 3D variable-range hopping (VRH) model at low temperatures, indicating that Ba2Re6Se11 is a semiconductor or insulator fairly near to a metal–insulator transition.

2. Materials and Methods

High-purity polycrystalline Ba2Re6Se11 was synthesized using a high-pressure and high-temperature technique. Stoichiometric BaSe, Re (99.9%, Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China), and Se (99.9%, Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China) powders were selected as the reactants. The BaSe precursor was prepared by sintering a mixture of Ba (99.9%, Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China) and Se (99.9%, Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China) powders at 750 °C for 12 hours in a vacuum-sealed quartz tube (10−4 Pa). The reactants were finely ground in an agate mortar, pressed into pellets, and subjected to a hinge-type six-anvil LVP. The pressure was slowly increased to 5 GPa over 30 minutes, after which the temperature was increased to 1475 K over 10 minutes and maintained for 30 minutes. Then, the temperature was quenched to room temperature in a few seconds and the pressure was slowly released to ambient pressure over 1 hour. Due to the air sensitivity of Ba, Se, and BaSe, the procedures before and after the high-pressure synthesis were performed in a glove box full of argon gas. It is worth noting that—in contrast to its sulfur counterpart, which can be synthesized in a H2S gas stream [28]—a highly sealed and high-pressure environment is necessary for synthesizing stoichiometric Ba2Re6Se11 in order to prevent the volatilization of Se and decomposition of BaSe.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu-Kα radiation. Rietveld refinement [30] was conducted using the GSAS-I software package [31]. The synchrotron XRD (SXRD) measurements were carried out on the BL15U1 beamline of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) (Shanghai, China) (λ = 0.62 Å). Diamonds with a 300 µm culet and rhenium gaskets were used [32]. No pressure medium was used. The pressures were determined using the ruby fluorescence method.

The magnetic measurements were performed using a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer (MPMS-3, Quantum Design, San Diego, CA, USA). Both zero-field-cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) modes were adopted under a magnetic field of 0.1 T. The electrical resistivity was measured using a physical property measurement system (PPMS-DynaCool, Quantum Design, San Diego, CA, USA) with a standard four-probe method. The specific heat was measured using PPMS. The sample (thickness of 0.4 mm) was mounted using Apiezon N grease to ensure good thermal contact. The specific heat data were corrected by subtracting the contributions from the sample puck and the grease.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structure

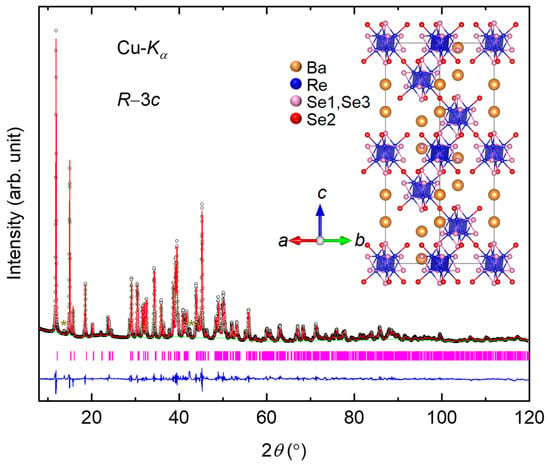

Figure 1 displays the XRD pattern of Ba2Re6Se11, which is well fitted to that of the R−3c (No. 167) space group with an a = 9.4891(9) Å and c = 33.3975(5) Å. For the Rietveld refinement, the atomic parameters of its sulfide counterpart Ba2Re6S11 [28] were adopted as the initial parameters. The refined crystallographic parameters are listed in Table 1. The refined occupancy values of all the atoms are very close to 1, so we fixed them. The variation between the calculated and the experimental XRD derives from the tiny impurities and the background (shifted Chebyshev polynomial, green line in Figure 1). It is worth noting that the thermal factor of Se1 is smaller than those of the other atoms, which is due to Se1 being coordinated with five cations; for comparison, Se2/Se3 is coordinated with four cations. Thus, the bonding of Se1 is relatively rigid, leading to a reduced thermal factor.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern and Rietveld refinement of Ba2Re6Se11. The black circles, green line, red line, and blue line indicate the observed, background, calculated, and difference, respectively. The magenta ticks indicate the allowed Bragg reflections for space group R−3c. The brown stars indicate minor unidentified impurities. The upper-right inset displays the crystal structure of Ba2Re6Se11.

Table 1.

Crystallographic parameters of Ba2Re6Se11.

As depicted in the inset of Figure 1, the building block of the structure is the cube-octahedral Re6Se8 cluster, which contains a nearly regular Re6 octahedron (shown in blue) with one Se atom capping each face, forming a Se8 cubic cage (Se1 and Se3, shown in pink). The Re6Se8 clusters are further connected by additional Se (Se2, shown in red) residing at the apical positions of the Re6 octahedra along the c direction, forming a Re–Se2–Re bond angle of 120.8732(5)°. The Ba atoms occupy the vacancies among the Re6Se8 clusters, forming BaSe10 units.

3.2. Crystallographic Stability

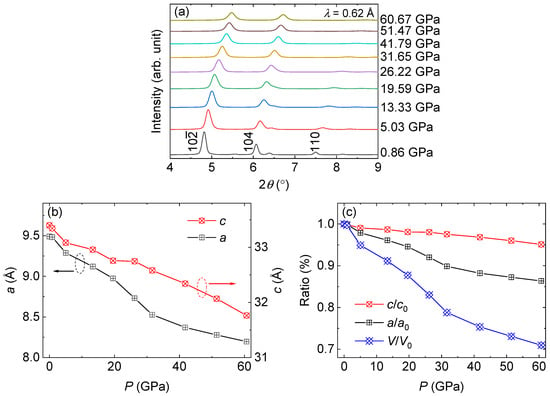

To study the structural stability of Ba2Re6Se11, we performed SXRD measurements under pressure. As shown in Figure 2a, with increasing pressure, the (1 0 −2), (1 0 4), and (1 1 0) diffraction peaks broaden and their intensities decrease, indicating gradual decrystallization under pressure. Meanwhile, all the diffraction peaks shift to a higher 2θ angle, indicating that the lattice was compressed under pressure. On the other hand, the lattice maintains its symmetry up to a pressure of 60 GPa, without any signs of a structural transition, indicating the robust crystallographic stability of Ba2Re6Se11. The non-hydrostaticity is not apparent due to the 3D lattice of Ba2Re6Se11 and the specimen being in powder form.

Figure 2.

(a) SXRD pattern of Ba2Re6Se11 under selected pressures. (b) a and c values as a function of applied pressure. (c) c/c0, a/a0 and V/V0 values as a function of applied pressure.

In order to quantitatively study the lattice parameters under pressure, we extrapolated a, c, and volume V. As depicted in Figure 2b, both a and c monotonously decrease with increasing pressure, without any indication of a phase transition. The c/c0, a/a0, and V/V0 values as a function of applied pressure are shown in Figure 2c, where the subscript “0” indicates the parameters at ambient pressure. One can observe the anisotropy between the in-plane and out-of-plane directions under pressure, with a decreasing by about 14% at a pressure of 60 GPa, whereas c only decreases by 5%, leading to a 30% reduction in V. The bulk modulus was obtained using the formula K = −dP/dV = 193(13) GPa. For comparison, the bulk modulus values for steel and diamond are ~160 GPa and ~600 GPa, respectively.

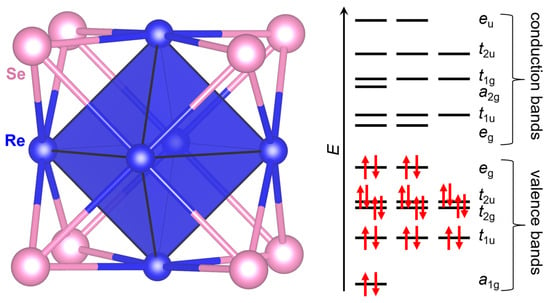

To determine the mechanism underlying the solid lattice stability of Ba2Re6Se11, we examined the Re6Se8 building block, which is reminiscent of M6X8 (M: transition metal; X: chalcogen) clusters in similar compounds [33,34,35]. The schematic representation of the molecular orbital of Re in the Re6Se8 cluster is depicted in Figure 3. When the M has a d4 configuration (e.g., Mo2+, Tc3+, or Re3+), the cluster possess 24 electrons in total and thus the valence bands are fully occupied, leading to the highly symmetrical nature of the Re6 octahedra as well as the robust lattice stability.

Figure 3.

Re6Se8 cluster in Ba2Re6Se11 and schematic representation of its molecular orbital. Each red arrow indicates one electron with spin-up/down state.

3.3. Magnetic Properties

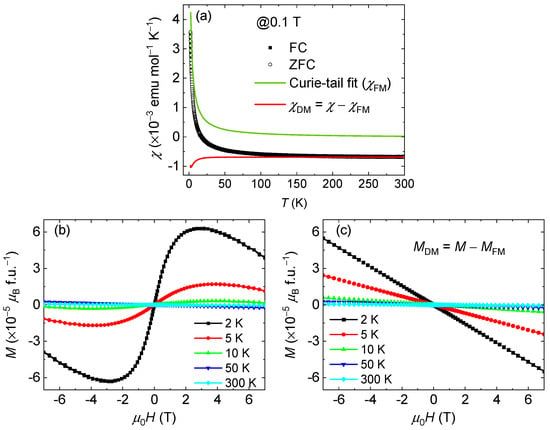

Figure 4a displays the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility (χ) of Ba2Re6Se11. Above 50 K, a negative χ value was observed, indicating a DM nature. Nevertheless, the M(T) curve shows an upturn below 50 K and changes to become positive, indicating the superposition of a paramagnetic or ferromagnetic (FM) contribution of χ = χDM + χFM. In order to distinguish these contributions, we performed Curie-tail fitting at temperatures above 50 K (χFM, green line), and the DM signal was obtained using χDM = χ − χFM (red line).

Figure 4.

(a) Temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility of Ba2Re6Se11 measured under 0.1 T. Experimental ZFC and FC data are shown as hollow circles and solid squares, respectively. Curie-tail fitting and curve are displayed as green and red lines, respectively. (b) Field dependence of magnetization at selected temperatures. (c) DM contribution extracted from field dependence of magnetization curve.

The field dependence of magnetization is displayed in Figure 4b. Above 50 K, the linear M(H) curves with a negative slope agree well with the DM state. However, at lower temperatures, the M(H) curves behave quite differently. For example, at 2 K, as the applied magnetic field increases, the M(H) curve rapidly increases to a maximum and then linearly decreases with a negative slope again. The magnetic moment at its maximum is extremely small (~10−5 μB f.u.−1), excluding the FM configuration of Re3+ (5d4, S = 1) in Ba2Re6Se11. On the other hand, the negative slope of the M(H) curve in a high magnetic field excludes the canted antiferromagnetic configuration [36,37]. Therefore, we conclude that the current Ba2Re6Se11 is DM. The upturn of the M(T) curves and the tiny magnetization of the M(H) curves at low temperatures are due to trace amounts of magnetic impurities (tens of ppm). To extract the DM contribution, we performed linear fitting of the M(H) curve in a field above 5 T. The obtained field-dependent magnetization of the DM part is depicted in Figure 4c.

The diamagnetism of Ba2Re6Se11 can be explained by the molecular orbital of the Re6Se8 cluster (Figure 3). The molecular orbital of the Re6 octahedral cluster, with a Re3+ (5d4) state, has 24 electrons at its highest occupied molecular orbital level that fully occupy the shell, giving rise to a diamagnetic state. Similar diamagnetic behavior has been observed in other compounds constituted by Re6 octahedral clusters, such as Ba2Re6S11 [28] and Tl4Re6X12 (X = S, Se) [38].

3.4. Transport Properties

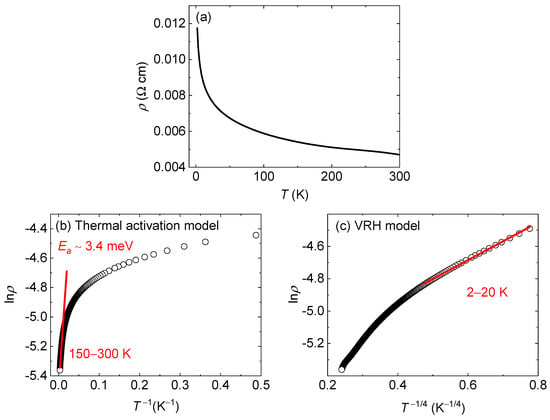

Figure 5a depicts the temperature dependence of the resistivity (ρ) of Ba2Re6Se11. The ρ value is smaller than 12 mΩ cm for the whole temperature range of 2–300 K, whereas it gradually increases with cooling. In order to quantitatively study the electrical conductivity, we fitted the ρ(T) plot using the thermal activation model at an elevated temperature range of 150–300 K and the formula lnρ = Ea/kBT + lnρ0, where kB is the Boltzmann constant (Figure 5b). The activation energy was calculated to be Ea = 3.4(1) meV and the residual resistivity is ρ0 = 4.19(1) mΩ cm. At low temperatures below 20 K, the ρ(T) plot is well fitted to the 3D VRH model with the equation lnρ = (T0/T)1/4 + lnρ0 (Figure 5c). The obtained ρ0 = 4.59(2) mΩ cm is in agreement with the values obtained from the activation model. Thus, Ba2Re6Se11 can be regarded as a semiconductor or insulator in close vicinity to a metal–insulator transition. It is worth noting that extrinsic effects, such as defect/impurity activation, grain-boundary barriers, and hopping conduction, can also contribute to the measured resistivity.

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature dependence of resistivity of Ba2Re6Se11. (b) lnρ–T−1 plot of experimental data (black circles) and fitting result (red line) of thermal activation model. (c) lnρ–T−1/4 plot of experimental data (black circles) and fitting result (red line) of 3D VRH model.

The semiconductivity of Ba2Re6Se11 can also be explained by the molecular orbital of the Re6 cluster depicted in Figure 3. The valence bands are fully occupied and the conducting bands are empty, with the Fermi level located at the top of the valence state. The close vicinity to a metal–insulator transition can be ascribed to the delocalization of the molecular orbital due to Re-Se covalency [23,24].

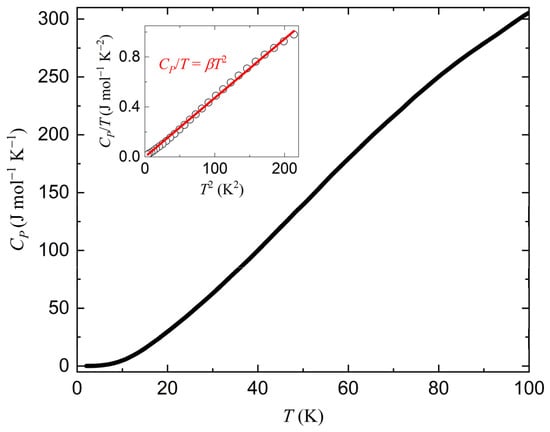

3.5. Heat Capacity

Figure 6 displays the temperature dependence of the heat capacity of Ba2Re6Se11. In order to determine the components of the heat capacity, we plotted the CP/T–T2 plot at 2–15 K (inset of Figure 6). It forms a linear curve with a zero intercept at the vertical axis, indicating that only the phonons contribute to the heat capacity. This behavior is consistent with Ba2Re6Se11 being diamagnetic and semiconductive. The CP/T–T2 curve is well fitted to the formula CP/T = βT2, where β = 4.72 mJ mol−1 K−4 (inset of Figure 6). The Debye temperature was found to be ΘD = (12nπ4R/5β)1/3 = 199 K, where n = 19 is the number of atoms per chemical formula and R = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1 is the ideal gas constant.

Figure 6.

Temperature dependence of heat capacity of Ba2Re6Se11. Inset displays CP/T–T2 plot at 2–15 K. Experimental data and fitting result are displayed as black circles and a red line, respectively.

4. Conclusions

Using a high-pressure synthesis technique, a novel ternary transition metal chalcogenide, Ba2Re6Se11, was synthesized. It crystallizes in the R−3c space group with an a = 9.4891(9) Å and c = 33.3975(5) Å. The structure is constituted by Re6Se8 cube-octahedral clusters connected by additional apical Se anions via the Re-Se-Re pathway, and the Ba atoms reside in the cavities between the Re6Se8 units. The Re has a valence state of +3, with four electrons occupying the 5d orbital for each Re atom. Consequently, the Re6 octahedron possesses 24 electrons at its molecular orbital level and forms a full-shell electron occupation configuration, giving rise to the robust lattice stability with a bulk modulus of 193 GPa. The fully occupied molecular orbital also gives rise to a diamagnetic state for Ba2Re6Se11, which was validated through magnetic measurements. The resistivity of Ba2Re6Se11 is as low as several milliohm centimeters, and it follows the thermal activation mechanism at elevated temperatures and the three-dimensional variable-range hopping model at low temperatures, indicating that Ba2Re6Se11 is a semiconductor or insulator in close vicinity to a metal–insulator transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. (Wenmin Li); methodology, Z.Z., X.W., F.Y. and W.L. (Wenmin Li); validation, X.W. and W.L. (Wenmin Li); formal analysis, G.L. and X.W.; investigation, G.L., X.Y., Z.D. and W.L. (Wenhui Liu); resources, G.L.; data curation, G.L. and W.L. (Wenmin Li); writing—original draft preparation, G.L.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and W.L. (Wenmin Li); visualization, X.W. and W.L. (Wenmin Li); supervision, W.L. (Wenmin Li); project administration, W.L. (Wenmin Li); funding acquisition, X.W. and W.L. (Wenmin Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Joint Fund of Henan Province Science and Technology R&D Program (Project No. 245200810084), the High-Level Talent Research Start-Up Project Funding of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project Nos. 241827046, 242027151, and 20251827005), the Fundamental Research Fund of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project No. 240627005), the Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics (Project No. 2023BNLCMPKF006), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12304159).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility of Experiment Assist System (https://cstr.cn/31124.02.SSRF.LAB) (accessed on 13 October 2025) for their assistance with the BL15U1, BL14B1 and BL17UM beamlines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aldakov, D.; Lefranςois, A.; Reiss, P. Ternary and Quaternary Metal Chalcogenide Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 3756–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipina, L.Y.; Wei, J.; Sorokin, P.B. Unlocking the Potential of 1D M2X3Y8 Ternary Transition Metal Chalcogenides: A Review. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 7195–7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Zhai, T. 2D Ternary Chalcogenides. Adv. Optical. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, B.W. Ternary Transition Metal Sulfides. In Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; Karlin, K.D., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; Volume 42, pp. 139–237. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, O.; Maple, L.B. Superconductivity in Ternary Compounds II: Superconductivity and Magnetism; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Telford, E.J.; Russell, J.C.; Swann, J.R.; Fowler, B.; Wang, X.; Lee, K.; Zangiabadi, A.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Nuckolls, C.; et al. Doping-Induced Superconductivity in the van der Waals Superatomic Crystal Re6Se8Cl2. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, B.J.; Choi, K.H.; Jeon, J.; Yoon, S.O.; Chung, Y.K.; Sung, D.; Chae, S.; Kim, B.J.; Oh, S.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Ternary Transition Metal Chalcogenide Nb2Pd3Se8: A New Candidate of 1D van der Waals Materials for Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, R.S.; Vengatesh, P.; Shyju, T.S. Review on ternary chalcogenides: Potential photoabsorbers. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Dong, S.; Gu, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Han, P.; et al. Highly Reversible Cuprous Mediated Cathode Chemistry for Magnesium Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11477–11482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fecher, G.H.; Kroder, J.; Borrmann, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-E.; Chen, C.-T.; Chen, K.; et al. Easy-Cone Magnetic Structure in (Cr0.9B0.1)Te. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.P.; Novak, T.G.; Bu, X.; Ho, J.C.; Jeon, S. Layered Ternary and Quaternary Transition Metal Chalcogenide Based Catalysts for Water Splitting. Catalysts 2018, 8, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronger, W. Ternary Rhenium and Technetium Chalcogenides Containing Re6 or Tc6 Clusters. In Metal Clusters in Chemistry; Braunstein, P., Oro, L.A., Raithby, P.R., Eds.; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1591–1611. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, A.; Perrin, C. The Molybdenum and Rhenium Octahedral Cluster Chalcohalides in Solid State Chemistry: From Condensed to Discrete Cluster Units. Comptes Rendus Chimie 2012, 15, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, J.T.; Velázquez, J.M. Design Principles for Multinary Metal Chalcogenides: Toward Programmable Reactivity in Energy Conversion. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 7133–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A.; Perrin, C.; Chevrel, R. Chevrel Phases: Genesis and Developments. Struct. Bond. 2019, 180, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Tan, J.; Tang, Y.; Gao, Q. Chevrel Phases: Synthesis, Structure, and Electrocatalytic Applications. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 5500–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lv, G.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Kong, L.; Tian, L.; Rao, W.; Li, Y.; Liao, L.; Guo, J. Chevrel Phase: A Review of Its Crystal Structure and Electrochemical Properties. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2023, 33, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, E. Multi-Anvil Cells and High Pressure Experimental Methods. In Treatise on Geophysics, 2nd ed.; Price, G.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Liu, Z.; Long, Y. High-Pressure Synthesis and Research Progress of Multi-Order Perovskite Oxides. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 3470–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Temnikov, F.; Ye, X.; Pi, M.; Pan, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Chen, C.-T.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Dong, C.; et al. CuCu3Fe2Os2O12: A Room-Temperature Ferrimagnet with Reduced Thermal Conductivity. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 20796–20803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafees, M.W.; Wang, X.; Yan, L.; Wang, F.; He, L.; Lu, J.; Zhao, T.; Hu, F.; Shen, B.; Long, Y. Magnetoelectric and Converse Magnetoelectric Effects in DyCrO4 Probed by Electron Spin Resonance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 385802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bither, T.A.; Bouchard, R.J.; Cloud, W.H.; Donohue, P.C.; Siemons, W.J. Transition Metal Pyrite Dichalcogenides. High-Pressure Synthesis and Correlation of Properties. Inorg. Chem. 1968, 7, 2208–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Komarek, A.C.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Peng, W.; Wang, X.; et al. High-Pressure Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Properties of Iron-Based Spin-Chain Compound Ba9Fe3Se15. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 054606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.-W.; Ye, X.; Liu, Z.; Nishikubo, T.; Sakai, Y.; Shen, X.; Liu, Q.; et al. Mixed Anion Control of Enhanced Negative Thermal Expansion in the Oxysulfide of PbTiO3. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 5394–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Fang, Y.-W.; Nikolaev, S.A.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Ye, M.; Liu, J.; Ye, X.; Wang, X.; Nishikubo, T.; et al. Anion-Mediated Unusual Enhancement of Negative Thermal Expansion in the Oxyfluoride of PbTiO3. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 6804–6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Bai, Y.; Yin, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Ye, X.; Lu, D.; Zhang, J.; Pi, M.; Hu, Z.; et al. CaCu3Mn2Te2O12: An Intrinsic Ferrimagnetic Insulator Prepared Under High Pressure. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 21233–21239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Dong, C.; Bian, Y.; Ding, W.; Sheng, Z.; Azuma, M.; et al. Formation of ZnO4 Tetrahedra and ZnO6 Octahedra in TeZnO3 Synthesized under High Pressure. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 6716–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronger, W.; Miessen, H.-J. Synthesis and Crystal Structures of Ba2Re6S11 and Sr2Re6S11, Compounds Containing [Re6S8] Clusters. J. Less-Common Met. 1982, 83, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, E.; Aurbach, D. Lattice Strains in the Ligand Framework in the Octahedral Metal Cluster Compounds as the Origin of Their Instability. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 1901–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, H.M. A Profile Refinement Method for Nuclear and Magnetic Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Dreele, R. Quantitative Texture Analysis by Rietveld Refinement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, S.; Shi, Z. High-Pressure Studies on Quasi-One-Dimensional Systems. Chin. Phys. B 2025, 34, 088104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughbanks, T.; Hoffmann, R. Molybdenum Chalcogenides: Clusters, Chains, and Extended Solids. The Approach to Bonding in Three Dimensions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluzet, A.; Duclusaud, H.; Sautet, P.; Borshch, S.A. Electronic Structure of Diamagnetic and Paramagnetic Hexanuclear Chalcohalide Clusters of Rhenium. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 2537–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaifulina, V.K.; Gaifulin, Y.M.; Ryzhikov, M.R.; Ulantikov, A.A.; Yanshole, V.V.; Naumov, N.G. Introduction of Niobium in the Chemistry of Octahedral Chalcogenide Clusters: Synthesis and Detailed Study of Compounds Based on Condensed and Discrete {Re5NbQ8} (Q = S or Se) Cores. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 15863–15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Ye, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Lu, D.; Pi, M.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. High-Pressure Single Crystal Growth and Magnetoelectric Properties of CdMn7O12. J. Phys. Condens. Mater. 2023, 35, 254001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Z.; Lu, D.; Pi, M.; Ye, X.; Dong, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Radu, F.; et al. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopic Study of the Transition-Metal-Only Double Perovskite Oxide Mn2CoReO6. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 15668–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, G.; Greaney, M.; Tsai, P.P.; Greenblatt, M. Tl4Re6X12 (X = S, Se): Crystal Growth, Structure, and Properties. Inorg. Chem. 1989, 28, 2448–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.