Abstract

Fulgides are a class of organic compounds that exhibit photochromic behavior in both the solid state and in solution. These compounds have attracted considerable research interest due to their wide range of potential applications, including photochromic eyewear, smart windows, optical switches, data storage, and chemical and biological sensors. Here, we report the synthesis and crystal structures of fulgides bearing four different para-substituents on the phenyl moiety. All four molecules crystallize in space groups containing an inversion center. The distances between the two carbon atoms that would form the single C–C bond in the cyclized products fall within the range of 3.301–3.475 Å. The observed structural variations are attributed to intermolecular interactions based on Hirshfeld surface analysis. The fulgides exhibit photochromism, but they are not expected to display ferroelectric behavior due to their crystallization in centrosymmetric space groups.

1. Introduction

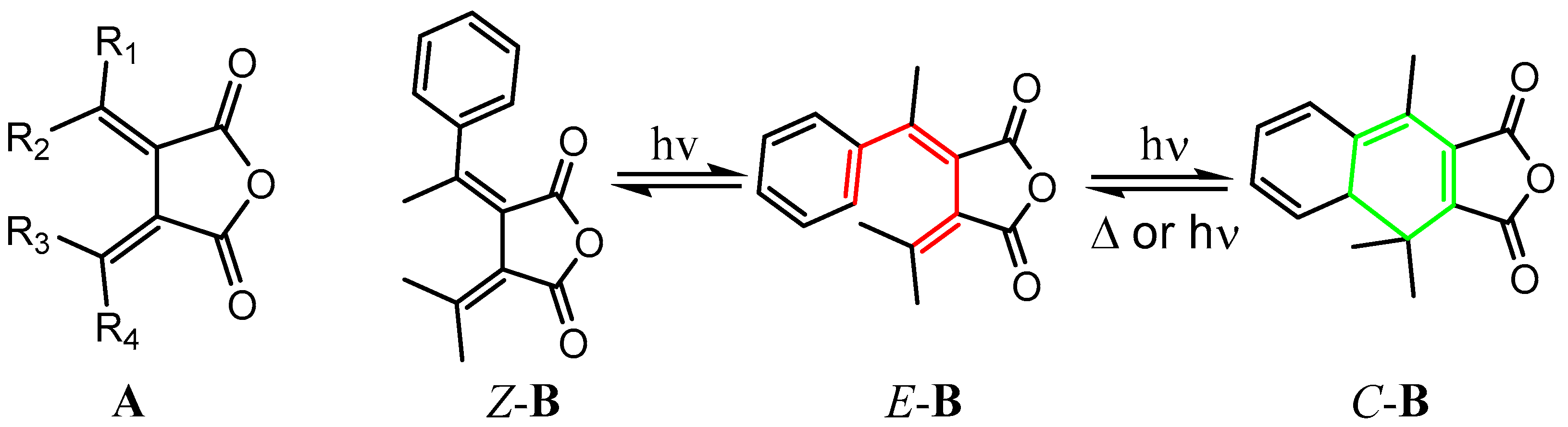

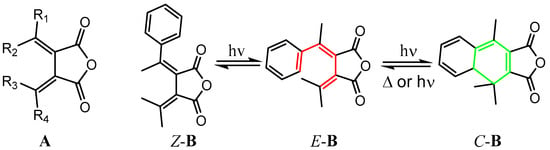

Fulgides are a class of succinic anhydride derivatives containing conjugated bis-methylene moieties, as illustrated by structure A in Figure 1A. When one or more substituents incorporate a double bond—most commonly within an aromatic group, as in E-B—the molecule can undergo a hexatriene electrocyclic reaction under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation to yield the cyclic product C-B. This transformation gives rise to photochromism: upon UV exposure, the open-form E-B cyclizes to C-B with a pronounced color change. When the UV light is removed, the color of C-B reverts to that of E-B through the thermal ring-opening reaction. The Z-B isomer can also isomerize to E-B, although the associated color change is typically much less pronounced than the E-B to C-B photochromic response [1].

Figure 1.

A: General structure of fulgides. Z-B, E-B, and C-B are isomers of a phenyl fulgide involved in photochromism.

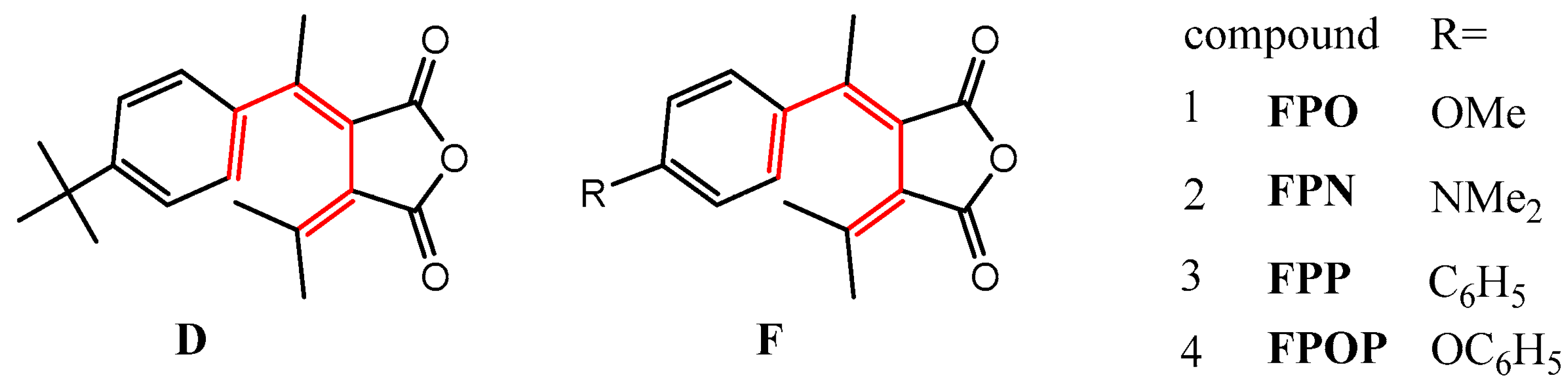

The photochromic fulgides have been attracting much research effort due to their wide potential applications, including photochromic eyewear, smart windows, optical switches, data storage, and chemical and biological sensors [2,3]. In addition to its photochromic properties, phenyl fulgide D (Figure 2) was reported by Dr. Wang and coworkers in 2023 [4] as the first fulgide compound ever discovered to exhibit ferroelectricity, marking a significant breakthrough in the field. Ferroelectric materials can retain polarization orientation, which can be switched by the application of an external electric field. This property is very important for ferroelectric RAM that can store data in its two stable polarization states, and for sensors and actuators in industrial automation [4,5]. Among ferroelectric materials, organic systems are attracting increasing research attention because of their flexibility and ease of synthesis and processing [6]. Although fulgides have been studied for a long time, phenyl fulgides like D have not attracted much attention, especially in regard to their crystal structures [7,8,9,10,11], which are essential for their photochromism and ferroelectricity. Discovering the ferroelectricity of fulgide D has inspired us to study more of its analogues. We designed, synthesized, and crystallized phenyl fulgides F with different substituents at the para position of the phenyl group. It was expected that any new fulgides would crystallize in non-centrosymmetric space groups due to their structure similarity to D and would exhibit ferroelectricity of different magnitudes because of the different electronic and size effects of the substituent groups. Their photochromism was expected for the same reasons. The designed fulgides will allow us to explore both electronic and size effects on the molecular packing in the crystals and the effects on their photochromic and ferroelectric properties. Here, we report the synthesis and crystal structures of the fulgides as our initial research results.

Figure 2.

D: Fulgide reported by Dr. Wang and coworkers [8]. F: Fulgides made and studied in this article.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instrumentation

Reagents and solvent: Compounds FPO, FPN, FPP, and FPOP were synthesized in our lab (see synthesis in Section 3). Reagents and solvents were purchased from chemical suppliers and used without further purification: the following reagents and solvents were purchased from Thermo Scientific Chemicals (Waltham, MA, USA): diethyl succinate; acetone (Certified ACS), potassium tert-butoxide, reagent grade; acetyl chloride; tert-butanol; 4-methoxyacetophenone, 99%; 4-dimethylaminoacetophenone, 99%; dichloromethane (Certified ACS); deuterated chloroform-d (99.8% atom); petroleum ether, (Certified ACS); and hexanes (98.5% Certified ACS). The following chemicals were purchased from Oakwood Chemical: toluene, 99.5%; 4′-phenoxyacetophenone, 97%; and chloroform, (Certified ACS reagent). The following chemicals were purchased from TCI: sodium hydride (60% dispersion in paraffin liquid); 4-acetylbiphenyl, 98%.

2.2. Instrumentation

1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Ascend Evo 400 MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin AG, Fällanden, Switzerland). Chemical shift in parts per million (ppm) was recorded with residual deuterated solvent (CDCl3: 7.260 ppm for 1H, and 77.16 ppm for 13C) signal as reference [12]. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) experiments were performed using a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Focus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The sample was injected into a 10 µL loop and was transferred to the mass spectrometer using a mobile phase containing 70% methanol and 30% water with 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 600 µL/min. The Q Exactive Focus HESI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) source was operated in full MS and positive mode. A XtaLAB Synergy (Rigaku, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), single source at home/near, Eiger2 1 M (Dectris, Baden-Daettwil, Switzerland), or a XtaLAB Synergy, Dualflex (Rigaku, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), HyPix diffractometer (Rigaku, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) was used for crystal data collection. Structures were solved with the ShelXT 2018/2 (Sheldrick, 2018) solution program using dual methods and Olex2 1.5 as the graphical interface.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Crystallizations

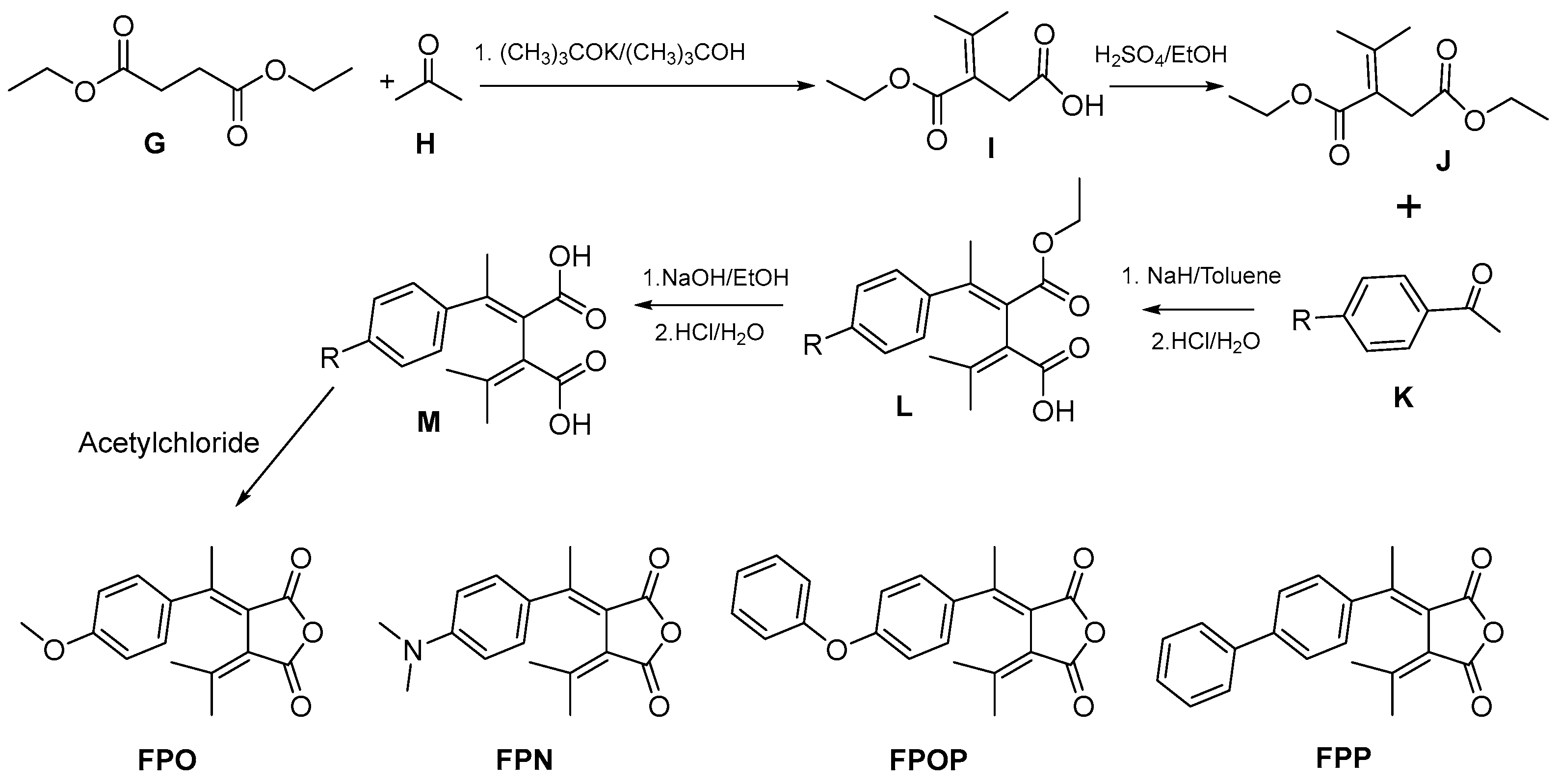

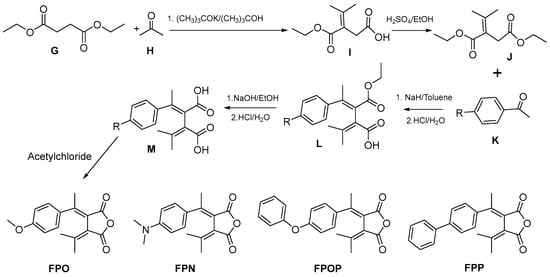

The synthesis of the fulgides was carried out following the slightly modified pathway illustrated in Scheme 1, which was reported previously.

Scheme 1.

The synthetic pathway to phenyl fulgide F.

Diethyl succinate G was reacted with one equivalent acetone H and one equivalent potassium tert-butoxide in tert-butanol under reflux for 8 h. After removal of solvent tert-butanol with a rotavapor under vacuum, the residue was poured into ice water. The water solution was washed with diethyl ether and then acidified to a pH of around 2 and transferred into a separatory funnel. The top layer was collected, and the aqueous phase was washed with ethyl acetate three times. The resulting ethyl acetate solution was combined with the top layer and dried with granular anhydrous sodium sulfate. 3-(ethoxycarbonyl)-4-methylpent-3-enoic acid I yielded when the ethyl acetate solution was condensed to dryness by a rotavapor under vacuum. The carboxylic acid I, without further purification, was esterified in refluxing ethanol using sulfuric acid as catalyst for 10 h to prepare crude diethyl 2-(propan-2-ylidene) succinate J after removal of solvent from the reaction mixture. The crude product was transferred to a flask and vacuum distilled to remove components of boiling point lower than 60 °C under a vacuum of 80 millitorr. The material left in the flask was distilled close to dryness to yield product J with a purity of approximately 85% based on estimation from the 1H NMR spectrum.

Each of the four para-substituted acetophenone K reacted with compound J to produce the corresponding F as detailed in the following. Sodium hydride (1.2 equivalents) was added to the solution of K in toluene, and the suspension was stirred for 24 h. The reaction mixture was poured into ice water to form a suspension, which was transferred into a separatory funnel and the top layer was removed. The aqueous solution was washed with toluene three times and then acidified to a pH of around 2 to yield compound L as precipitate. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried by a rotavapor and then transferred into a flask. To the flask containing compound L was added ethanol and sodium hydroxide (10 equivalents to L). The mixture was refluxed for 12 h, cooled down to room temperature, and then the sodium salt of M yielded as precipitate. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with chilled ethanol, dried by a rotavapor, and transferred into a beaker. Water was added to the beaker until the precipitate dissolved. The resulting solution was acidified with concentrated hydrochloric acid to a pH of around 2 to yield compound M as precipitate. The precipitate M was collected by filtration, washed with chilled water, transferred to a round-bottomed flask, and dried with a rotavapor. Acetyl chloride was added to the flask containing M (50 mL acetyl chloride per gram of M), and the resulting solution was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. The acetyl chloride was then removed by a rotavapor. The resulting solid in the flask was subjected to silica gel chromatography, and the fractions that exhibited red color on the wet TLC plate under UV detector were collected and condensed to yield the corresponding F, which was confirmed to be of E-F: FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP. FPO was synthesized previously [13], while its crystal structure has not been reported. The products of Z-F were not our primary focus and were therefore not isolated from the reaction mixture. All E-F were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and Mass Spectroscopy and the corresponding spectra are provided in Supplementary Materials.

3.1.1. (E)-3-(1-(4-Methoxyphenyl) Ethylidene)-4-(Propan-2-ylidene) Dihydrofuran-2,5-dione (FPO)

FPO yielded as yellow plate-shaped crystals with a yield of 13% based on the amount of 4-methoxyacetophenone used.

1H NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 1.07, singlet, 3 H; 2.11, singlet, 3H, 2.57, singlet, 3 H; 3.70, singlet 3 H; 6.78–6.80, doublet, 2 H; 7.16–7.18, doublet, 2H.

13C NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 22.64, 22.17, 55.48, 114.55, 119.66, 120.10, 129.37, 134.80, 154.12, 154.57, 160.27, 154.57, 160.27, 163.59, 164.13.

ESI-MS, C16H16O4, [M + H+]: 273.1115, expected: 273.1121.

3.1.2. (E)-3-(1-(4-(Dimethylamino) Phenyl) Ethylidene)-4-(Propan-2-ylidene) Dihydrofuran-2,5-dione (FPN)

FPN yielded as orange plate-shaped crystals with a yield of 14% based on the amount of 4-dimethylaminoacetophenone used.

1H NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 1.25, singlet, 3 H; 2.23, singlet, 3H, 2.67, singlet, 3 H; 3.01, singlet 3 H; 6.62–6.65, doublet, 2 H; 7.24–7.26, doublet, 2H.

13C NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 22.42, 22.63, 26.27, 40.21, 111.87, 117.64, 120.83, 129.43, 150.86, 153.23, 155.35, 164.11, 164.45.

ESI-MS, C17H19NO3, [M + H+]: 286.1430, expected: 286.1438.

3.1.3. (E)-3-(1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl) Ethylidene)-4-(Propan-2-ylidene) Dihydrofuran-2,5-dione (FPOP)

FPOP yielded as yellow block-shaped crystals with a yield of 18% based on the amount of 4-phynoxyacetophenone used.

1H NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 1.14, singlet, 3 H; 2.13, singlet, 3H, 2.57, singlet, 3 H; 2.61, singlet 3 H; 6.89–7.30, multiple peaks, 9H.

13C NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm):22.57, 22.60, 26.18, 118.59, 119.61, 119.88, 120.18, 124.27, 129.41, 130.02, 136.93, 153.41, 154.82, 158.31, 16.31, 163.93.

ESI-MS, C21H18O4, [M + H+]: 335.1269, expected: 335.1278.

3.1.4. (E)-3-(1-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl) Ethylidene)-4-(Propan-2-ylidene) Dihydrofuran-2,5-dione (FPP)

FPP yielded as yellow plate-shaped crystals with a yield of 12% based on the amount of 4-acetylbiphenyl used.

1H NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 1.08, singlet, 3 H; 2.12, singlet, 3H, 2.64, singlet, 3 H; 7.26–7.30, multiple peak 3 H; 7.34–7.38, multiple peaks, 2 H; 7.51–7.54. multiple peaks, 4 H.

13C NMR in CDCl3 (chemical shift in ppm): 22.52, 22.64, 26.28, 119.82, 120.64, 126.98, 127.62, 128.05, 128.20, 129.02, 139.68, 141.50, 141.74, 153.64, 155.32, 163.33, 163.95.

ESI-MS, C21H18O3, [M + H+]: 319.1322, expected: 319.1329.

3.2. Crystal Structure and Discussion

A single crystal was picked from the crystals of each fulgide: FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP, and was subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis. The major parameters and results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement of FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP.

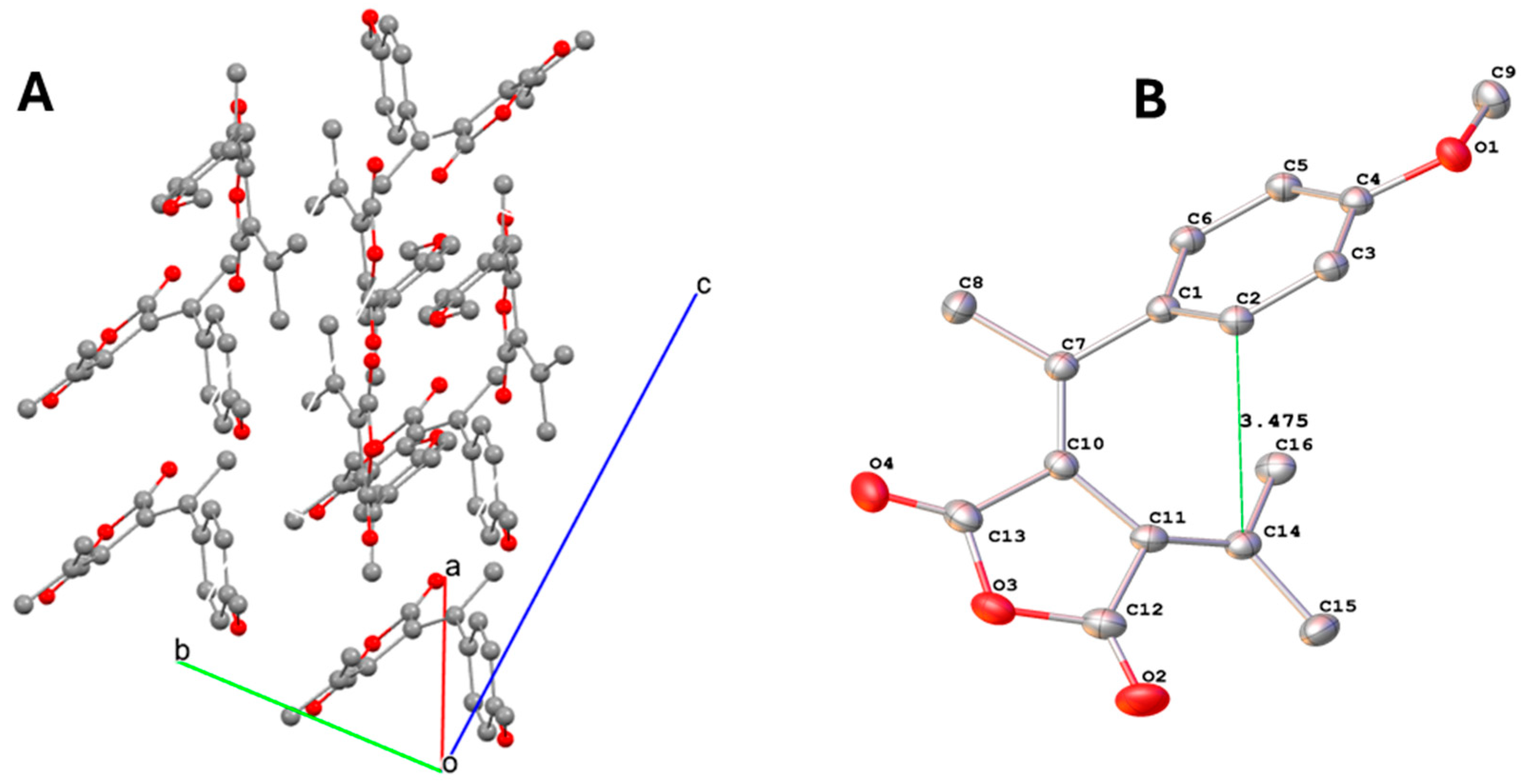

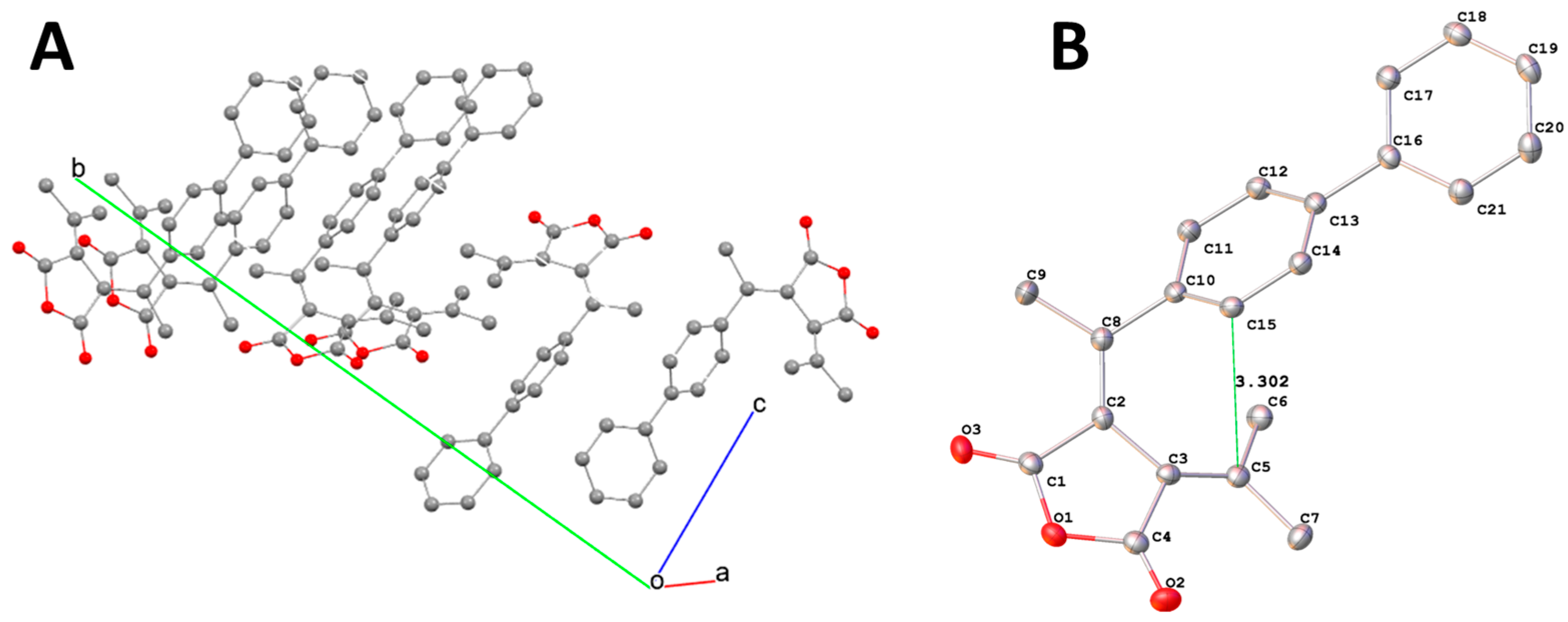

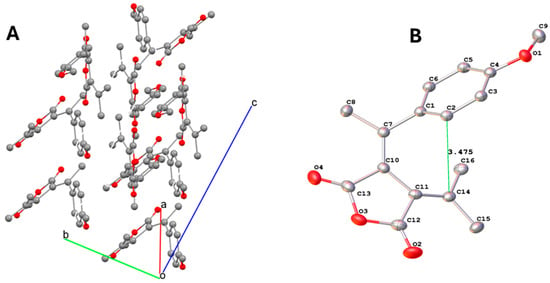

To determine the crystal structure of FPO, a suitable single yellow plate-shaped crystal with dimensions 0.20 × 0.20 × 0.10 mm3 was selected and mounted on a XtaLAB Synergy, single source at home/near, Eiger2 1M diffractometer. Data was measured using ω scans with Ag Kα radiation. The crystal was kept at a steady T = 110.00 K during data collection. The structure was solved with the ShelXT 2018/2 solution program using dual methods and Olex2 1.5 [14] as the graphical interface. The model was refined with ShelXL 2019/2 [15,16] using full matrix least squares minimization on F2. The final wR2 was 0.1426 (all data), and R1 was 0.0473 (I ≥ 2σ(I)). Major parameters and results are listed in Table 1. The structure was determined to be monoclinic with a space group of P21/n (No. 14). The molecular packing of FPO in the crystal is illustrated in Figure 3A. The structure of FPO is illustrated in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

(A) Molecular packing of FPO in the crystal; (B) ORTEP diagram of molecule FPO with hydrogen atoms omitted. Atoms are labeled differently in the other molecules. Therefore, the list of bond length, bond angle, torsion, and distance between atoms, and in the context of discussions are based on the labelling of atoms in the structure of FPO.

The bond distances of nonhydrogen atoms, selected bond angles, and torsion angles were measured and are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Bond length (Å) in molecule FPO.

Table 3.

Selected bond angles (degrees) in molecule FPO.

Table 4.

Selected torsion angles (degrees) in molecule FPO.

The structure of fulgides can be viewed as comprising three moieties: the succinic anhydride, the phenyl group, and the conjugated system of C7=C10–C11=C14. The bond lengths among carbons C1-6 in the phenyl group fall into the range 1.385–1.402 Å, which is consistent with those in a substituted benzene. The two C=C double bonds C7=C10 and C13=C14 are 1.3662 Å and 1.3578 Å, respectively, which are slightly longer than the average C=C length of 1.34 Å due to distorted conjugation. Single C–C bonds, as exemplified by C14–C15 and C14–C16, with lengths of 1.5022 Å and 1.4932 Å, are slightly shorter than the average of 1.54 Å due to being adjacent to a double bond. The torsion of C7–C10–C11–C14 is −35.8°, which shows the great distortion of the C7=C10–C11=C14 conjugated system. The torsion of C2–C1–C7–C10 is −50.76°, showing that the C11=C14 double bond is far from a perfect conjugation of 0° torsion. The torsion angles C1–C7–C10–C11 and C13–C10–C11–C12 indicate that the double bond of C7=C10 and C11=C14 are distorted by a similar extent of −11.18° and 10.42°. The significant distortions of the conjugated system and the double bonds are caused by the stereo repulsion between the methyl group of C14 and the phenyl group. The stereo strain energy drives the molecule to undergo intramolecular cyclization. The distance between the C14 and C2 was measured to be 3.475 Å.

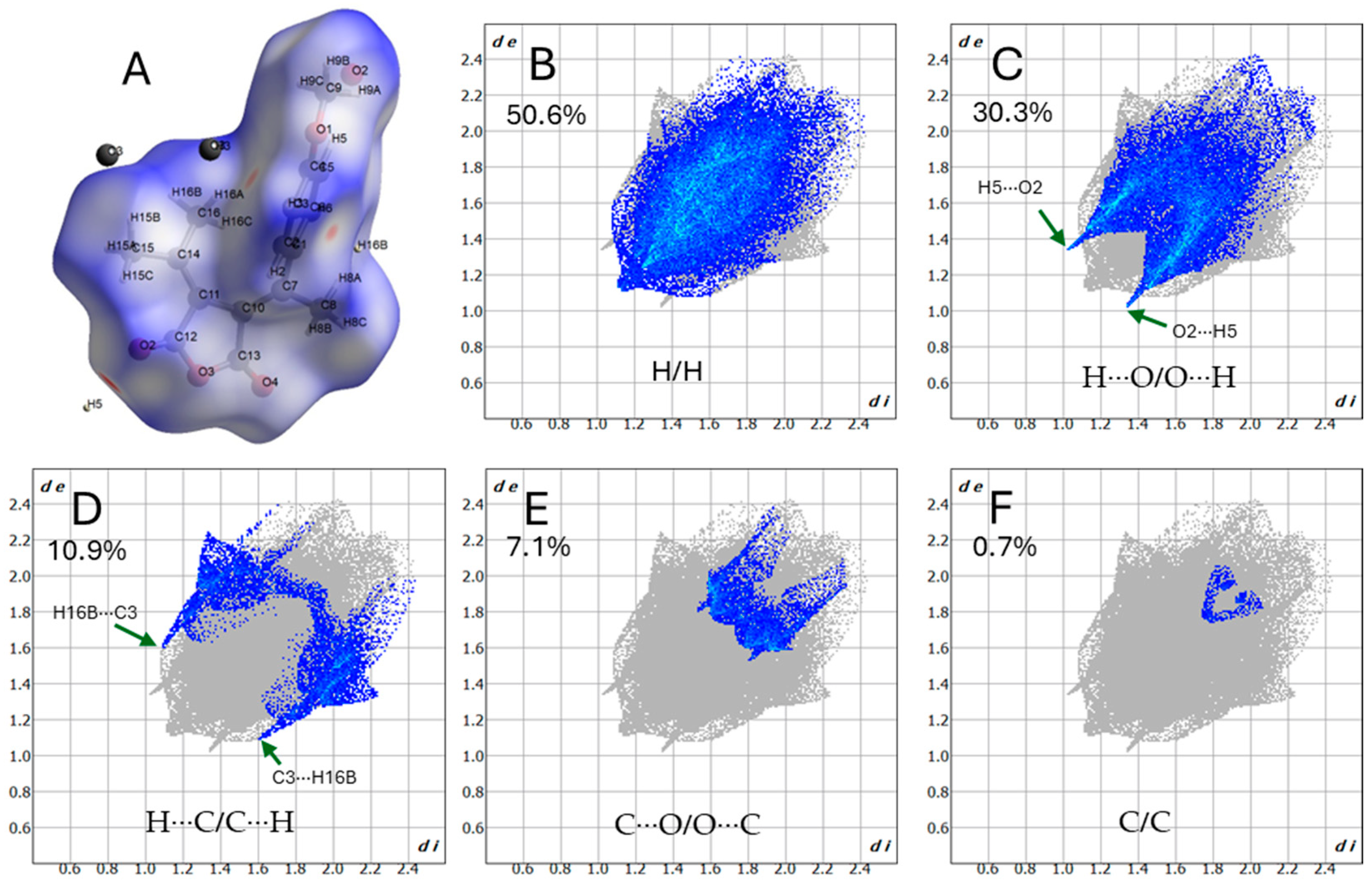

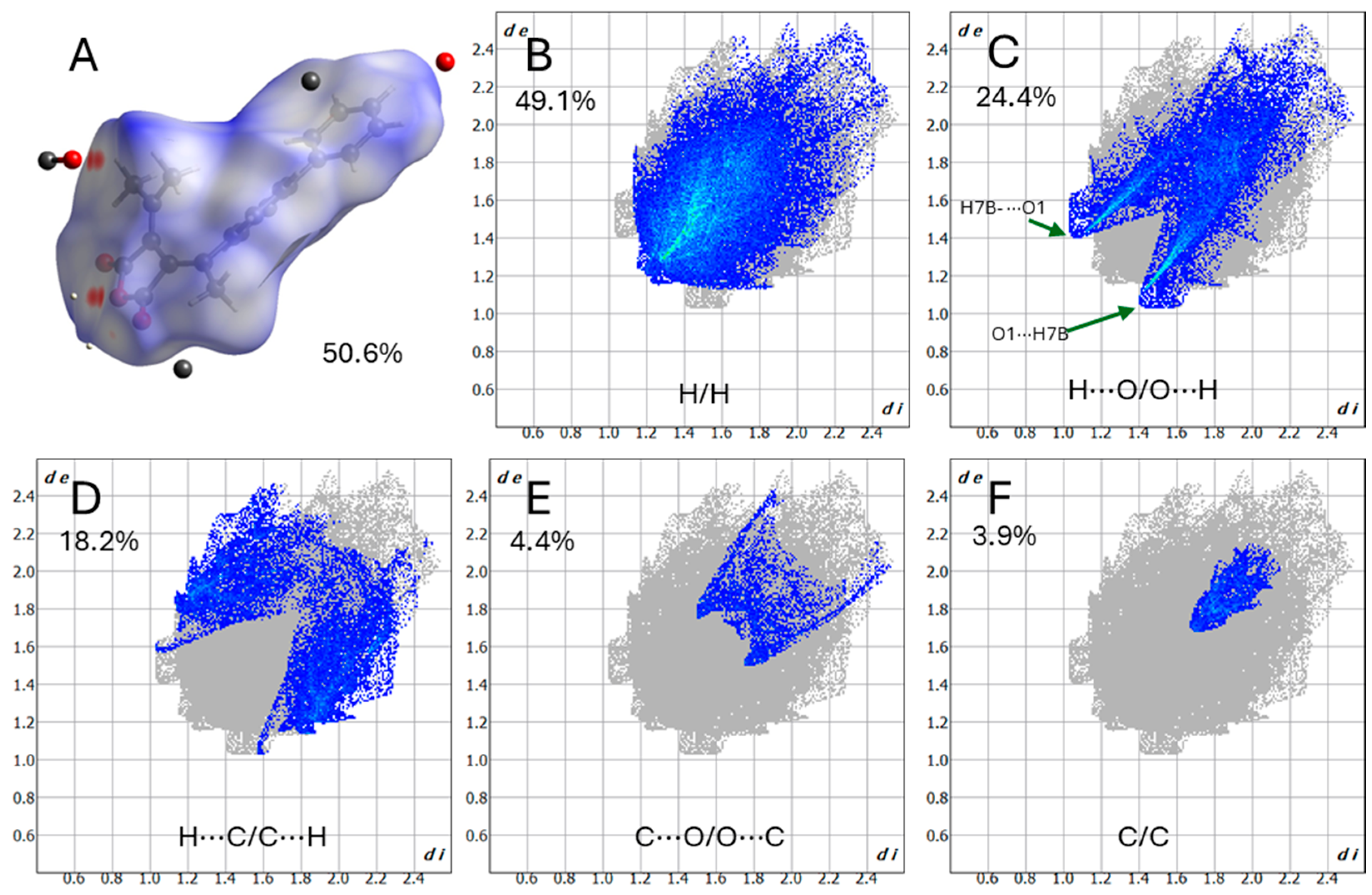

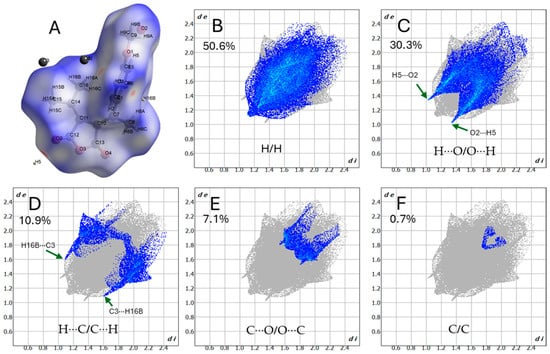

Intermolecular interactions were examined using Hirshfeld surface (HS) analysis. The molecular surface of FPO is shown in Figure 4A. Atoms outside the surface exhibit close contacts with their counterparts within the van der Waals repulsion range. The surface is dominated by H···H and H···O contacts, which contribute 50.6% and 30.3% of the total area, respectively, together accounting for 90.9% of the Hirshfeld surface as shown in Figure 4B–F. The H···C and C···O contacts contribute an additional 10.9% and 7.1%, while C···C and O···O contacts together account for the remaining ~1%, indicating negligible contributions from these interactions. A substantial number of H···H contacts fall within the 2.2–3.5 Å range associated with strong to weak van der Waals attraction, making them the largest contributors to crystal stabilization. Numerous H···O and H···C contacts, occurring in the 2.5–2.8 Å and 2.6–3.0 Å ranges, respectively, also provide meaningful stabilizing contributions. Approximately 7.1% of the Hirshfeld surface arises from antiparallel approaches of the anhydride C=O bonds at distances around 4.0 Å, close to the neutral van der Waals separation for C···O. These contacts therefore generate only negligible—if any—repulsion between the succinic moieties in the crystal. All remaining contacts are too few in number or too long in distance to exert measurable intermolecular effects.

Figure 4.

(A) Molecular surface of FPO with surrounding atoms in close contact. (B–F): Reciprocal contact fingerprint of H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O, and C···C, respectively, with the total fingerprint in the gray background.

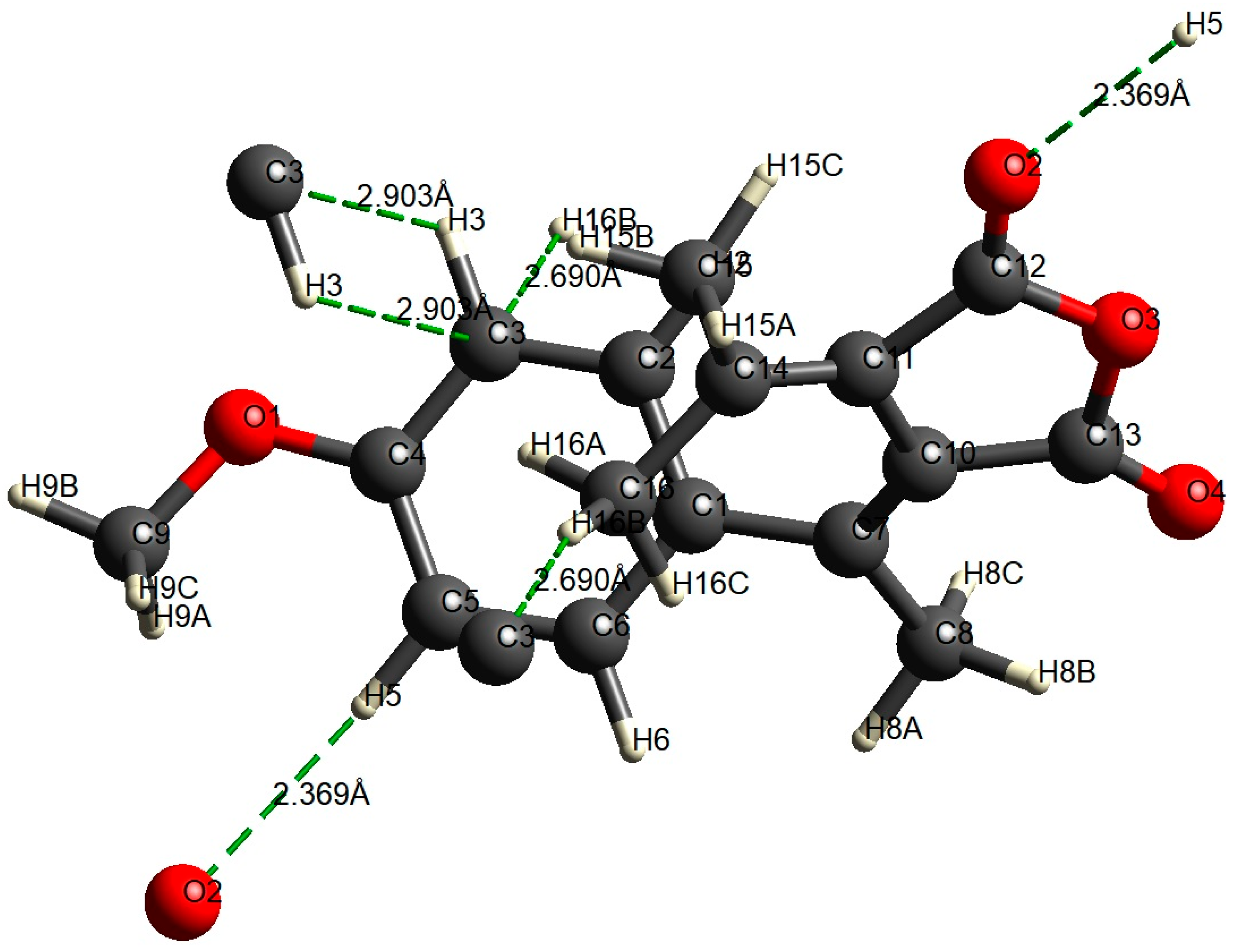

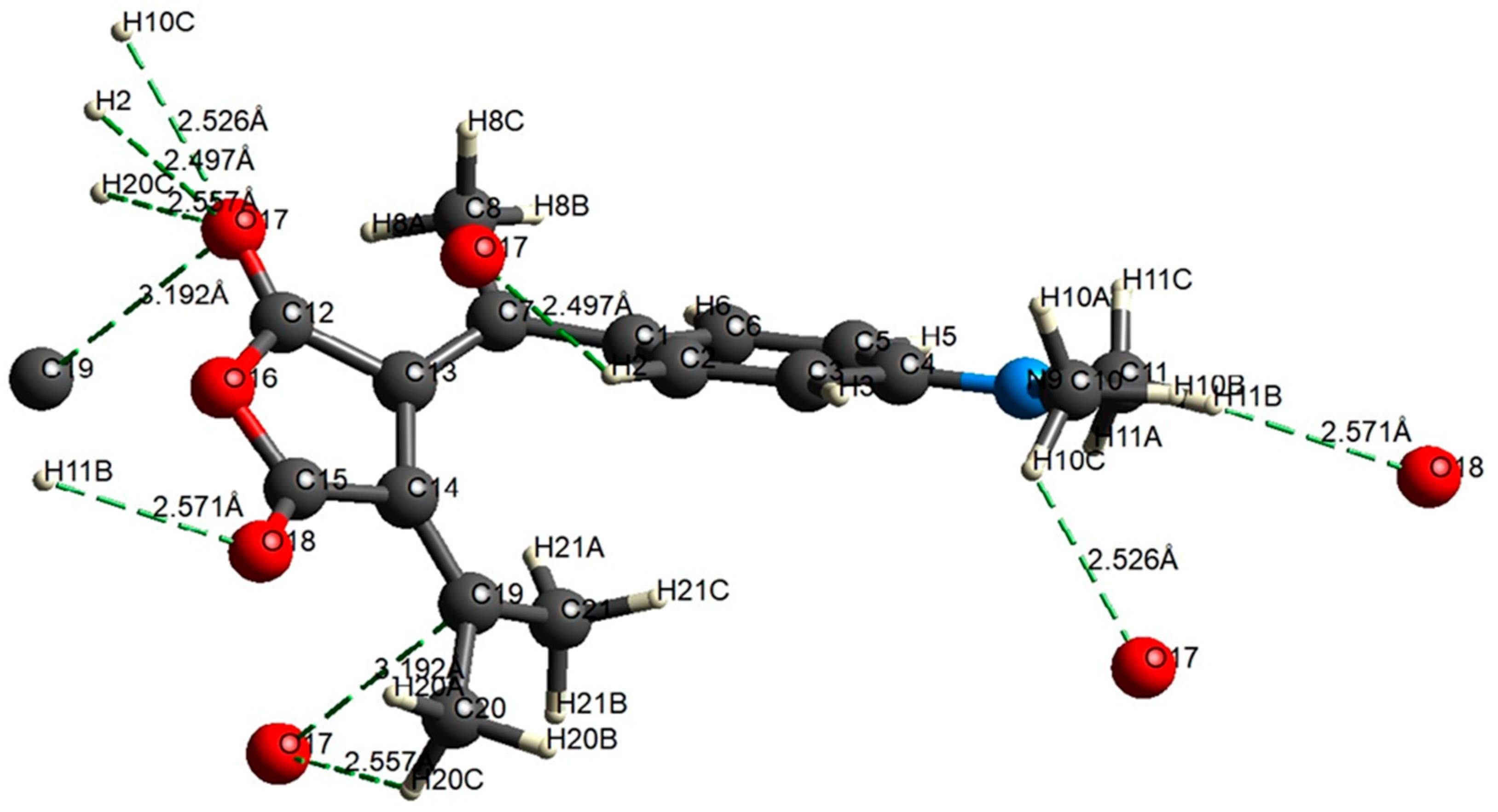

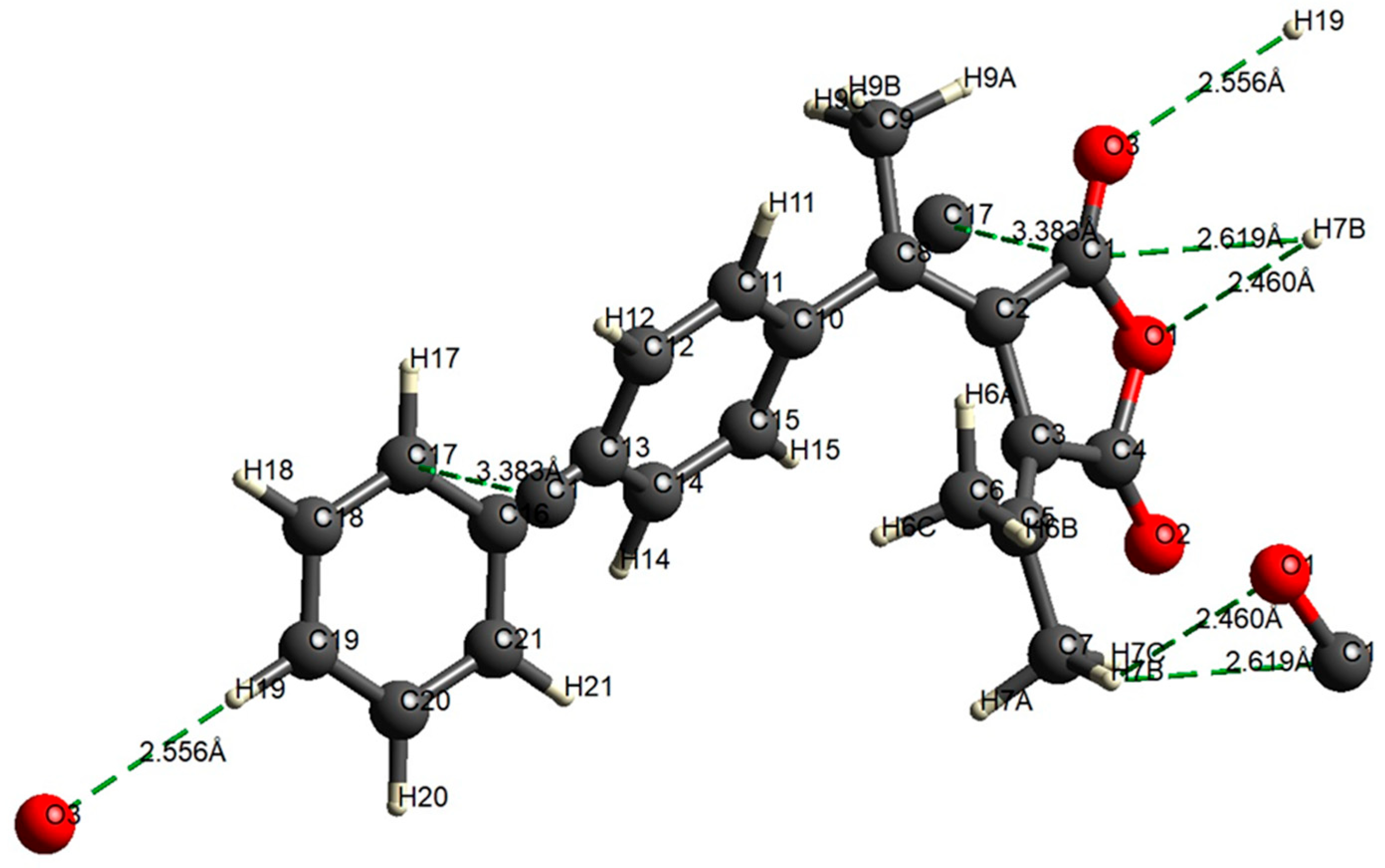

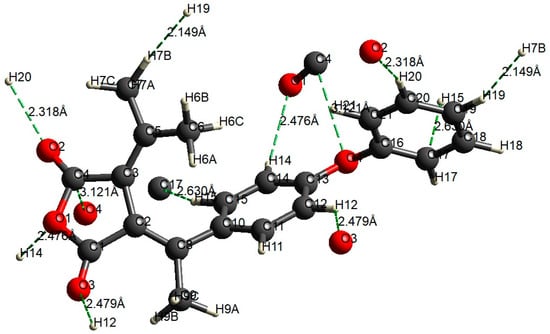

Three pairs of reciprocal contacts are identified on the Hirshfeld surface as red spots, partially shown in Figure 4A, and their corresponding distances are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Close contacts and distance between atoms of close contact in FPO crystal.

Among the close-contact red spots on the Hirshfeld surface, the two darkest ones are identified as the reciprocal H5···O2 contacts, which give rise to sharp spikes in the fingerprint plot (Figure 4C). The measured distance of 2.369 Å is substantially shorter than the neutral van der Waals separation of approximately 2.72 Å for H···O contacts, indicating strong steric repulsion. This repulsive interaction forces the phenyl moiety to tilt, thereby increasing the distance between C2 and C14 in FPO.

The two pale red spots correspond to reciprocal H16···C3 contacts, which produce curved spikes in the H···C fingerprint plot (Figure 4D). The distance of 2.690 Å lies near the transition region between weak repulsion and weak attraction and therefore does not represent a significant stabilizing or destabilizing interaction. Another pale red spot corresponds to an antiparallel overlap between two H3–C3 groups, with a separation of 2.903 Å. This value is extremely close to the neutral van der Waals distance of approximately 2.92 Å, indicating a negligible effect on crystal packing. No π–π overlap or other interactions were found to notably influence the crystal packing of FPO.

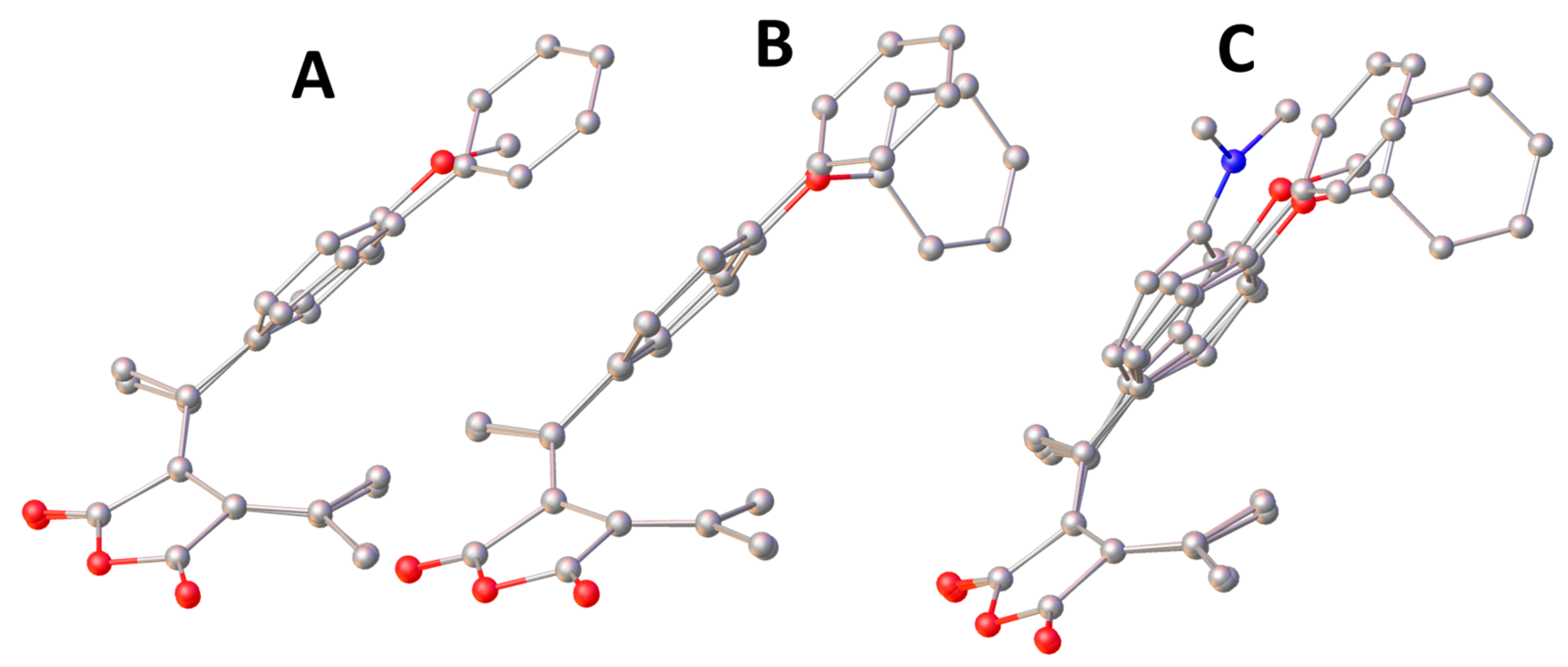

To see the effect of electron-donating groups on the structure of the fulgide, we prepared the FPO’s analogue, FPN, which has a stronger electron-donating dimethyl amino group than the methoxy group at the para position of the phenyl group in FPO. To determine the crystal structure of FPN, a suitable single orange plate-shaped crystal of dimensions 0.20 × 0.10 × 0.02 mm3 was selected from the crystalized product and mounted on a XtaLAB Synergy, Dualflex, HyPix diffractometer. Data was measured using ω scans with Cu Ka radiation. The crystal was kept at a steady T = 100.00(10) K during data collection. The structure was solved and refined as that of FPO. The parameters of determination and crystal structures are listed in Table 1. The molecular packing of FPN in the crystal is illustrated in Figure 6A. The structure of FPN is illustrated in Figure 6B. The selected bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles of FPN are listed with those of FPOP and FPP for comparison in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 (Numbers are rounded to discard uncertainty).

Figure 6.

(A) Molecular packing of FPN in the crystal; (B) ORTEP diagram of molecule FPN with hydrogen atoms omitted. (C) Overlay of FPO and FPN.

Table 5.

The selected bond lengths of FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP.

Table 6.

The selected bond angles of FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP.

Table 7.

Selected torsion of FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP.

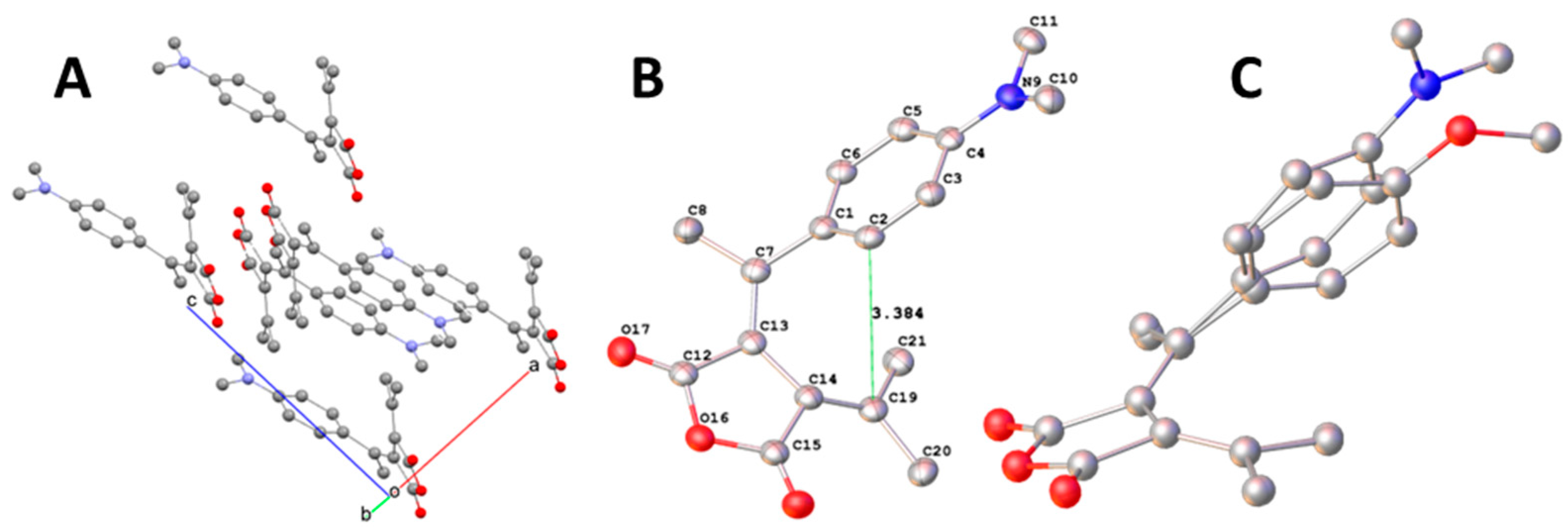

The crystallographic results show that the selected bond lengths in FPN exhibit no significant changes compared with those in FPO. In contrast, notable differences are observed in the bond angles: the C12–C11–C10 angle increases by 16.9°, from 105.6° in FPO to 122.5° in FPN. The torsion angles C2–C1–C7–C10, C1–C7–C10–C11, and C8–C7–C10–C13 also change substantially, shifting from −50.8°, −11.2°, and −17.4° in FPO to −38.2°, −17.6°, and −25.0° in FPN, respectively. Structural overlay of FPO and FPN, aligned by matching atoms C12, C11, C10, and C13, clearly indicates that these torsional differences arise from rotation about the C1–C7 single bond (Figure 6C). This rotation slightly decreases the distance between atoms C2 and C14—which form the C–C bond during the cyclization reaction—from 3.475 Å to 3.384 Å. Considering that the dimethylamino group is similar in steric size to the methoxy group, the significant differences in crystal packing are more likely to arise from electronic perturbations or intermolecular interactions.

Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed to evaluate the role of intermolecular interactions in the crystal packing of FPN. The molecular surface and fingerprint plots of the major contacts are shown in Figure 7A–F. Atoms outside the surface exhibit close contacts with their counterparts. The contributions of H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O, and C···C contacts to the surface area are 55.6%, 25.9%, 10.9%, 3.0%, and 2.7%, respectively, together accounting for 98.1% of the total area.

Figure 7.

(A) Molecular surface of FPN with surrounding atoms in close contact. (B–F): Contact fingerprint of H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O, and C···C, respectively, with the total fingerprint in the gray background.

The H···H contacts contribute more to the total surface area than all other contacts combined. No close H···H contacts in the repulsion range were observed; instead, a considerable number fall within the van der Waals attraction range, playing a dominant role in crystal stabilization. H···O contacts account for slightly more than one quarter of the surface area, with many lying in attraction range and contributing significantly to stabilization. Five pairs of reciprocal close contacts were identified as ten red spots on the Hirsfeld surface that are partially shown in Figure 7A and totally in Figure 8 with measured distance.

Figure 8.

Close contacts and distance between atoms of close contact in FPN crystal.

Among the five pairs of reciprocal close contacts, four are H···O interactions: H2···O17, H10C···O17, H11B···O18, and H20C···O17, with distances of 2.497, 2.526, 2.571, and 2.577 Å, respectively. All are shorter than the neutral van der Waals separation of approximately 2.72 Å for H···O contacts. This indicates that the H2···O17 contact is strongly repulsive, whereas the remaining three are only weakly repulsive. The distance of C19···O17 contact is 3.129 A within the 3.0–3.2 A range of weak attraction. The H11B···O18 contact corresponds to the close repulsive H5···O2 contact in FPO. The pronounced separation of the dimethylamino phenyl moiety from the methoxy phenyl moiety in FPO can be attributed to repulsion between H11B···O18 and H10C···O17. The unusually large dihedral angle C1–C1–C7–C13 of –38.2°, compared with –50.8°, 46.5°, and –46.0° in FPO, FPOP, and FPP, respectively, may result from repulsion between O17···H2. The reciprocal C19···O17 contacts appear as two spots of very weak repulsion and have no observable structural effect. No H···C contacts exhibit repulsion, though several fall within the van der Waals attraction region and contribute slightly to stabilization. No close C···C contacts were observed. Overall, C···C and H···C interactions contribute little to stabilization due to their small surface area contributions and limited number of contacts in the attraction range.

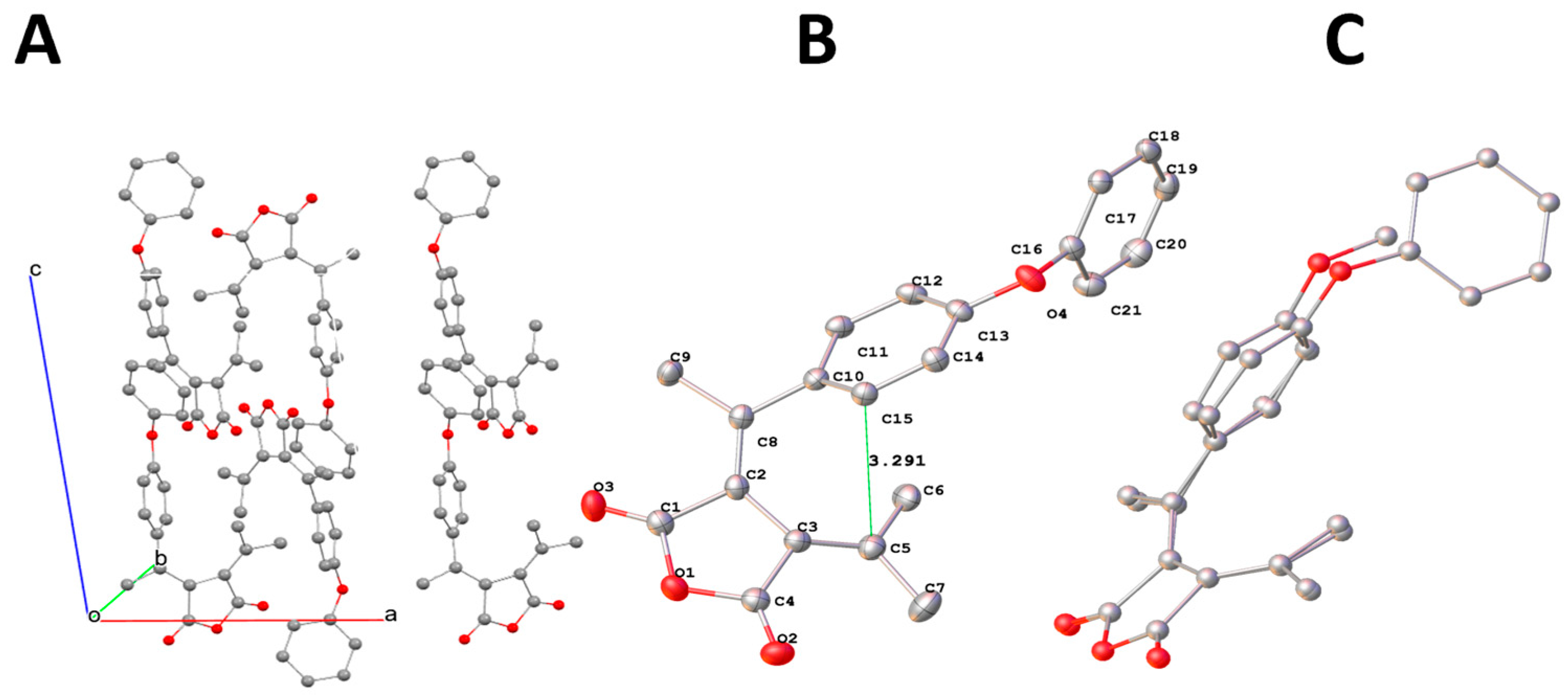

To investigate the size effect of the para-substituent, a phenyl group—larger than the methyl group in FPO—was introduced into the fulgide FPOP. X-ray crystallographic analysis was then performed to elucidate its structure. A single yellow block-shaped crystal of FPOP was subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis. A suitable crystal with dimensions 0.34 × 0.23 × 0.18 mm3 was selected and analyzed using the same diffractometer, parameters, and conditions. The structure was solved and refined as FPO. The parameters of determination and crystal structures are listed in Table 1. The molecular packing of FPOP in the crystal is illustrated in Figure 9A. The structure of FPOP is illustrated in Figure 9B.

Figure 9.

(A) Molecular packing of FPOP in the crystal; (B) ORTEP diagram of molecule FPOP with hydrogen atoms omitted. (C) Overlay of FPO and FPOP.

To highlight the structural differences caused by the size increase, selected bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles in FPOP are listed in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 for comparison. Bond lengths within the conjugated system show no difference between FPO and FPOP. Among the selected bond angles, the C12–C11–C10 angle increases to 121.8° in FPOP from 105.6° in FPO, like the change observed in FPN. For torsion angles, the most pronounced change occurs in C1–C7–C10–C11, shifting from –11.18° in FPO to –4.3° in FPOP, while C8–C7–C10–C13 changes from –17.4° in FPO to –14.3° in FPOP. These variations arise from distortion around the double bonds C7=C10 and C11–C14, as well as slight rotation about C1–C7. As a result, the interatomic distance decreases from 3.475 Å in FPO to 3.302 Å in FPOP.

The structures of FPOP and FPO were overlaid by aligning the carbon atoms of the succinic moiety, as illustrated in Figure 9C. In comparison with the overlay of FPN and FPO, it is evident that FPOP more closely resembles FPO than FPN. The phenyl moiety in FPOP slants away from that in FPO to a much smaller extent than in FPN, and in the opposite direction. Since intermolecular forces were found to play a major role in the structural differences between FPO and FPN, Hirshfeld surface analysis was also performed for FPOP, with the results shown in Figure 10.

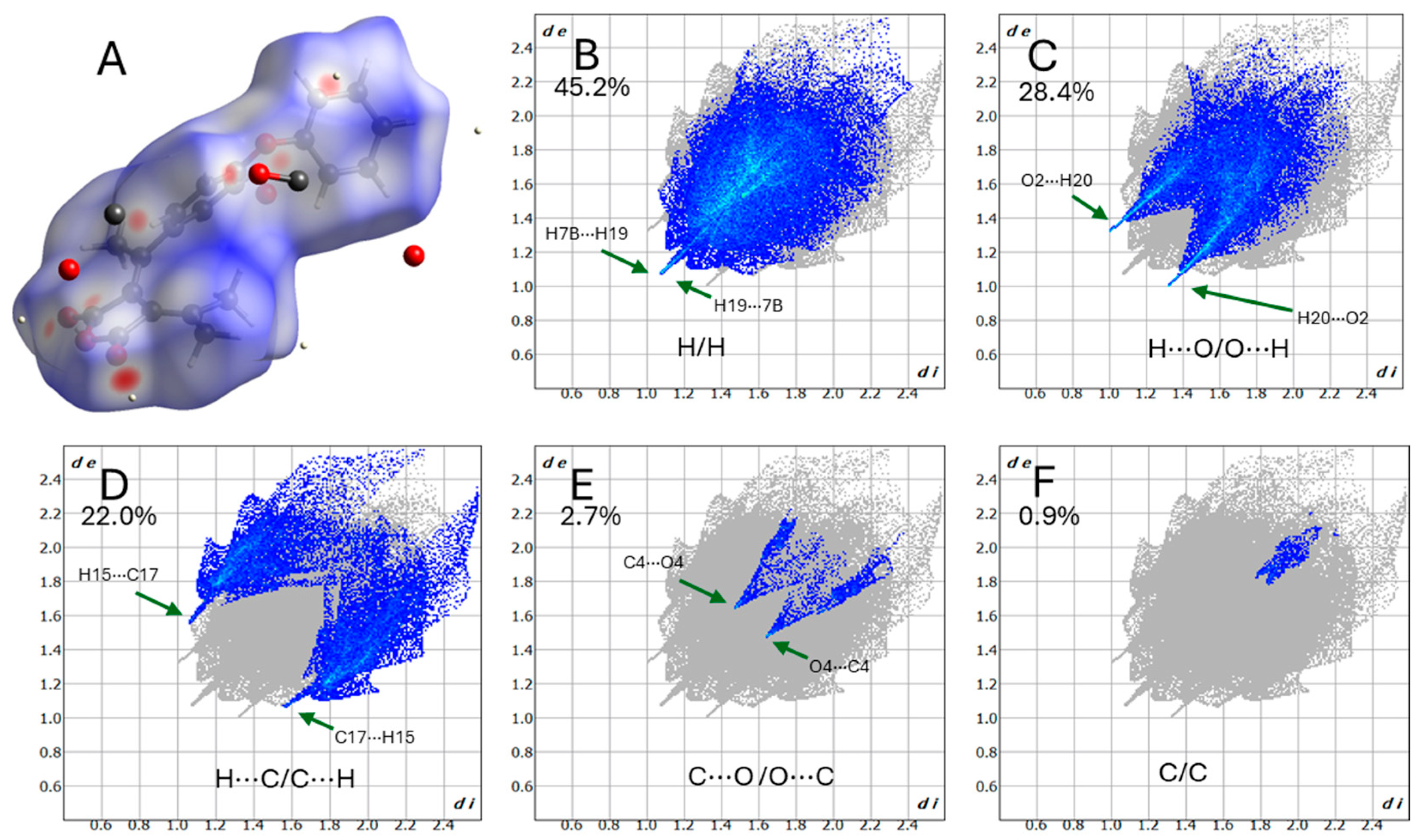

Figure 10.

(A) Molecular surface of FPOP with surrounding atoms in close contact. (B–F): Contact fingerprint of H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O, and C···C, respectively, with the total fingerprint in the gray background.

The molecular surface of FPOP is illustrated in Figure 10A. Atoms and fragments outside the surface exhibit close contact with their corresponding counterparts inside the molecule. The total surface area is dominated by H···H, H···O, and H···C interactions, contributing 45.2%, 28.4%, and 22.0%, respectively, for a combined total of 95.6%. In contrast, C···O and C···C and O···O interactions contribute 2.7%, 0.9%, and 0.8%, respectively, accounting for the remainder of the surface area. Six pairs of reciprocal close contacts are identified as red spots on the surface, partially shown in Figure 10A. All the contacts, along with their corresponding distances, are presented in Figure 11.

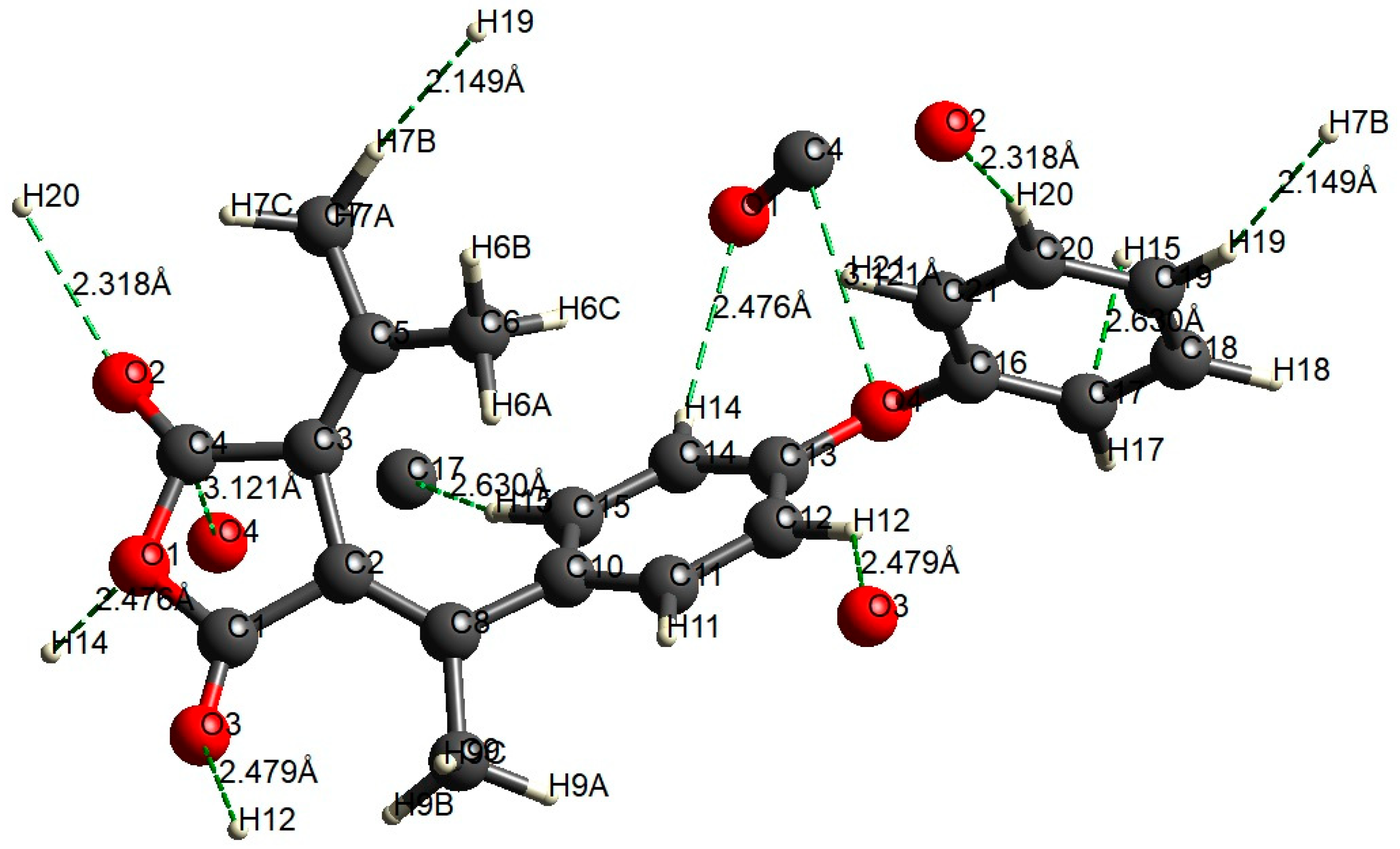

Figure 11.

Close contacts and distance between atoms of close contact in FPOP crystal.

A substantial number of H···H contacts fall within distances of van der Waals attraction range, contributing appreciably to the stabilization of the crystal. Numerous H···O and notable H···C contacts also lie within the attractive van der Waals regime and further support crystal stabilization. The close contact between H7B and H19 appears as a red spot on the Hirshfeld surface and as a distinct spike in the H···H fingerprint plot. The H···H distance of 2.149 Å is profoundly shorter than the van der Waals limit of 2.20 Å for two hydrogen atoms. This indicates a strongly repulsive contact. Three H···O close contacts—H20···O2, H14···O1, and H12···O3—with distances of 2.318, 2.476, and 2.479 Å, respectively, appear as red spots on the Hirshfeld surface. The reciprocal H20···O2 contact is markedly shorter than the neutral van der Waals separation of approximately 2.7 Å and produces a distinct spike in the H···O region of the fingerprint plot, indicating a strongly repulsive contact. In contrast, the distance H14···O1 and H12···O3 contacts deviate only slightly from the neutral distance and therefore represent weakly repulsive close contacts. The H15···C17 contact is the only H···C close contact that appears as a red spot on the Hirshfeld surface. Its measured distance of 2.630 Å within the weakly attractive range 2.6–2.9 A of H···C contact. A pale red spot is also observed for the C4···O4 contact, with a distance of 3.121Å, slightly shorter than the neutral value of 3.22 Å. This contact likely reflects a weak repulsive interaction. The combined influence of the H14···O1, H12···O3, H15···C17, and C4···O4 contacts may contribute to the slight positional difference observed for the phenyl moiety of FPOP relative to FPO and FPN in the molecular overlay. Among these, the strongly repulsive H20···O2 contact together with the H15···C17 repulsion appears to play a dominant role in determining the orientation of the phenoxy group.

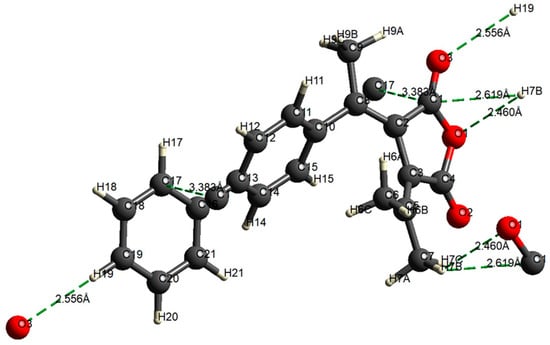

The fulgide FPP contains a phenyl substituent with negligible electron-donating ability, in contrast to its analogue FPO, which bears a small methoxy group of moderate electron-donating character. Comparison of the crystal structures of FPP and FPO is therefore expected to provide insight into both electronic and steric substituent effects on crystal-packing patterns. Accordingly, FPP was synthesized, crystallized, and subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis. A yellow block-shaped single crystal of FPP (0.62 × 0.50 × 0.32 mm3) was selected and analyzed using the same diffractometer. The structure was solved and refined in an analogous manner to FPOP. The crystallographic parameters and structural details are summarized in Table 1. The molecular packing of FPP is shown in Figure 12A, and the molecular structure is depicted in Figure 12B.

Figure 12.

(A) Molecular packing of FPP in the crystal; (B) ORTEP diagram of molecule FPP with hydrogen atoms omitted.

For convenient comparison of the structures, the selected bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles are summarized in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. The bond lengths associated with the conjugated system show no discernible differences among the analyzed structures. The C12–C11–C10 bond angle in FPP increases to 122.9°, similar to the values observed in FPN and FPOP, compared with 105.6° in FPO. The selected torsion angles in FPP closely resemble those in FPOP but differ significantly from those in FPO and FPN.

The distance between C15 and C5 was measured to be 3.302 Å in comparison to those of 3.475 Å, 3.384 Å, and 3.291 Å in FPO, FPN, and FPOP, respectively. The changes can be easily observed in the overlay of structures of FPO to FPP and FPOP to FPP, as shown in Figure 13A,B. The phenyl group in FPP tilted a little closer to the carbon involved in cyclization than in FPO, as shown in Figure 13A. Phenyl and phenoxy groups of similar size as substituents led to almost the exact overlap of the phenyl moieties, although the substituents oriented quite differently in the crystal. This result suggests that the substituent size plays a role in crystal packing.

Figure 13.

(A) Overlay of FPO and FPP. (B) Overlay of FPOP and FPP. (C) Overlay of FPO, FPOP, and FPP with hydrogen atoms omitted.

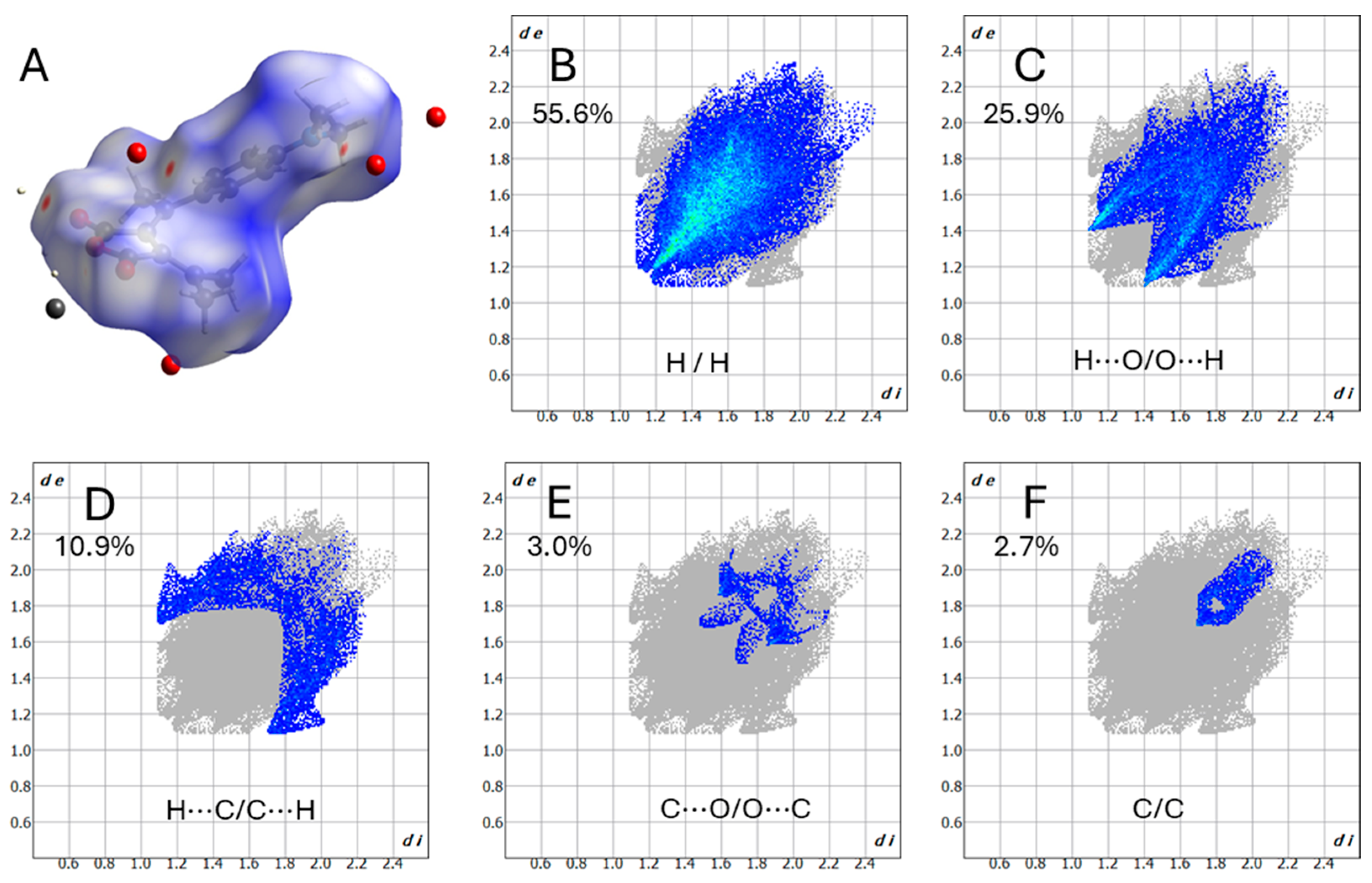

The intermolecular interaction environment of FPP was examined using Hirshfeld surface analysis, and the results are presented in Figure 14. The molecular surface of FPOP, highlighting surrounding atoms in repulsive contact, is shown in Figure 14A. The corresponding contact fingerprint plots for H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O, and C···C interactions are displayed in Figure 14B–F, with the total fingerprint shown in gray as the background.

Figure 14.

(A) Molecular surface of FPP with surrounding atoms in close contact. (B–F): Contact fingerprint of H···H, H···O, H···C, C···O and C···C, respectively, with the total fingerprint in the gray background.

The analysis shows that H···H, H···O, and H···C contacts contribute 49.1%, 24.4%, and 18.2% of the total Hirshfeld surface area, respectively, together accounting for 91.7% of the surface. A measurable number of C···O and C···C contacts contribute an additional 4.4% and 3.9%, respectively, while the remaining fraction arises from other minor interactions. Crystal stabilization is dominated by the large number of H···H contacts within the van der Waals attraction range, with smaller but notable contributions from C···O and C···C contacts. Five reciprocal close contacts are indicated by red spots on the Hirshfeld surface, shown partially in Figure 14A and fully in Figure 15, together with their measured distances.

Figure 15.

Close contacts and distance between atoms of close contact in FPP crystal.

No repulsive H···H close contacts were observed. The reciprocal H19···O3 contacts have a distance of 2.556 Å, which is significantly shorter than the van der Waals limit of 2.8 Å. Together with the nearly linear C19–H19···O3 angle of 156°, these contacts are therefore best interpreted as weakly attractive. Four prominent red spots correspond to close approaches between H17B and the adjacent O1 and C1 atoms, which are directly bonded within the succinic moiety. The H17B···O1 and H17B···C1 contact distances are 2.460 and 2.619 Å, respectively, compared with neutral van der Waals separations of 2.72 and 2.80 Å. This suggests the contacts are strongly repulsive. Consequently, these interactions represent significant repulsion between the C17 methyl group and its intermolecularly adjacent succinic fragment.

All four crystal structures were overlaid by matching the positions of the four carbon atoms in the succinic moiety, as shown in Figure 13C. The succinic fragment exhibits excellent overlap across all structures. The C2···C14 distances are 3.475, 3.384, 3.291, and 3.302 Å in FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP, respectively, and these variations correlate well with rotation around the C10=C11 double bond, accompanied by the corresponding displacement of the C8 methyl group and the phenyl moiety. The abnormal separation of the dimethylamino group from the other three substituents is attributed to intermolecular repulsive close contacts between two hydrogen atoms of the corresponding methyl groups and the two oxygen atoms of the adjacent anhydride fragment, as revealed by the Hirshfeld surface analysis. The long distance between C2 and C14 in FPO is attributed to strong repulsive interactions between H2 and an oxygen atom of the adjacent anhydride fragment, as revealed by the Hirshfeld surface analysis. In FPN, the increase in the distance expected from the slanting of the phenyl moiety is counteracted by a similarly strong H2 and O repulsion, resulting in a shorter separation than that observed in FPO. No conclusive evidence was found to indicate that electronic effects influence the molecular structures of the fulgides in the crystals examined. The phenyl moieties in FPOP and FPP overlap almost perfectly, whereas those in FPO and FPN deviate from this alignment in different ways. These observations suggest that the size and configuration of the substituents influence the crystal structures of the fulgides, although in a manner that is not straightforward to predict.

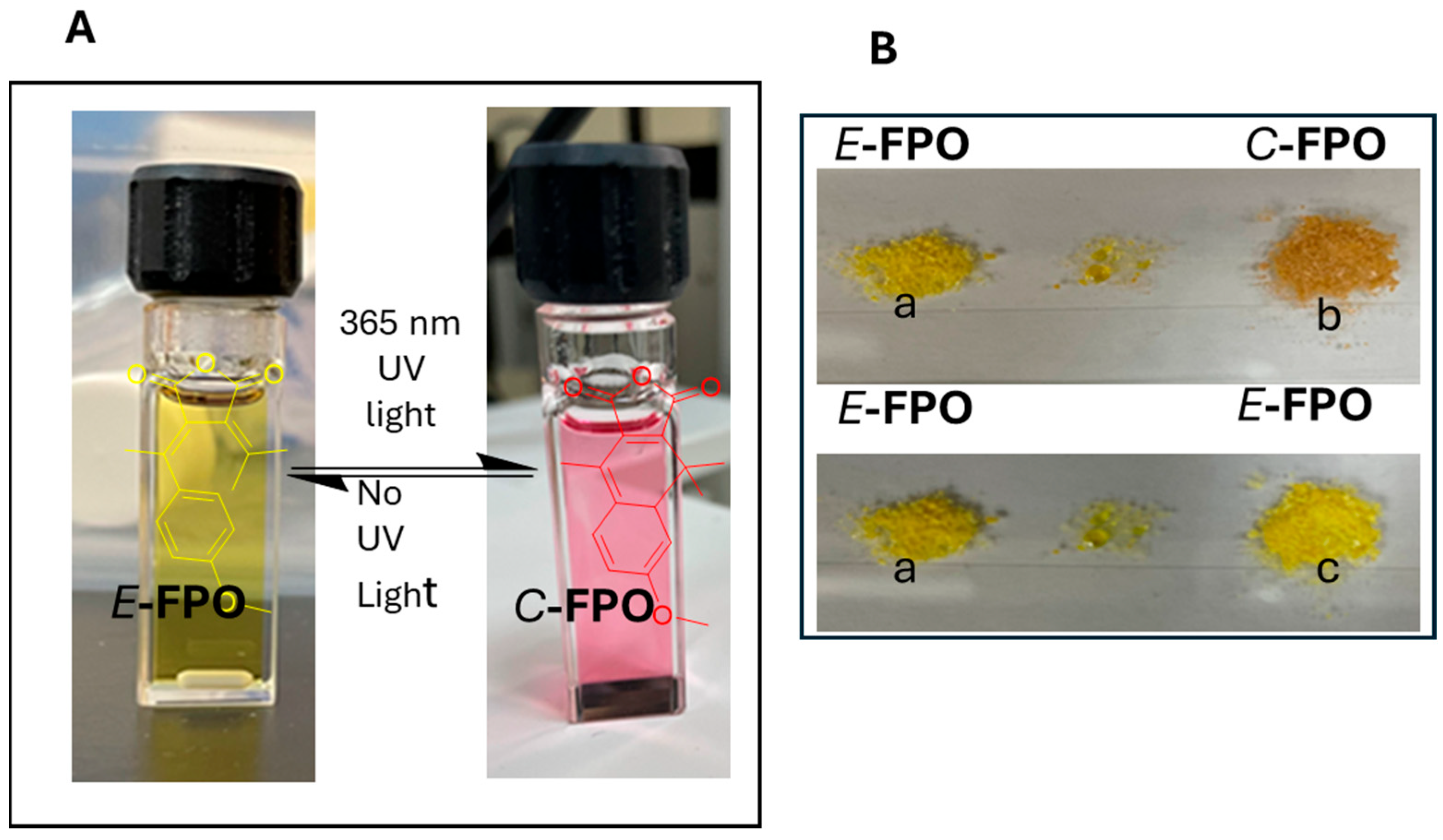

All four fulgides exhibited photochromic properties in the purification process of each compound. All the fulgides were isolated in pure form by column chromatography. Fractions that contain the E form of fulgides exhibited a color change on wet thin-layer chromatography plates under a UV (365 nm) detector. The results of our early-stage study on photochromism are shown in Figure 16 using E-FPO as an example. The color of E-FPO in methylene dichloride changed from yellow to red upon UV irradiation and recovered to its original state within 5 min after the irradiation was stopped (see Figure 16A). This phenomenon is attributed to the formation of C-FPO under UV irradiation, which subsequently converted back to E-FPO once the irradiation ceased. Photochromism of fulgides in the solid state was also observed, as illustrated in Figure 16B. In this figure, piles a and b consist of small amounts of E-FPO (the material between them is a minor spill). Pile a was not exposed to UV light, whereas pile b was irradiated with 365 nm UV light for 2 min, resulting in a color change from yellow to brown. Pile c represents pile b five minutes after cessation of UV irradiation. The reversible color change observed in pile b provides clear evidence of photochromism in the solid state of E-FPO.

Figure 16.

(A) Photochromism of FPO in solution. (B) Photochromism of FPO in solid state: a. E-PFO without UV irradiation, b. E-PFO after UV irradiation for 1 min, c. E-FPO 5 min after UV irradiation ceased.

The crystallographic results showed that all four fulgides F—FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP—packed into centrosymmetric space groups of P21/n, P-1, P21/c, and P21/c, respectively, in contrast to structural analogue D, which crystallized in a non-centrosymmetric space group Pc and exhibited ferroelectricity [8]. Such a crystal packing difference among fulgides of very similar molecular structures was beyond our expectation and needs to be understood. The results suggest that the new crystalized fulgides should not be spontaneously ferroelectric, which requires crystals of a non-centrosymmetric space group.

4. Conclusions

A small group of phenyl fulgides—FPO, FPN, FPOP, and FPP—has been synthesized and characterized. A single crystal of each compound was selected for X-ray crystallographic analysis, and the corresponding crystal structures were determined. Hirshfeld surface analysis was employed to evaluate the intermolecular effects governing the crystal structures. The observed structural variations among the fulgides are attributed to intermolecular interactions, as revealed by the Hirshfeld analysis, with no clear evidence for contributions from substituent electronic properties. All fulgides studied here crystallize in centrosymmetric space groups and are therefore not expected to exhibit ferroelectric behavior. Photochromic responses were observed, and preliminary results of these studies are presented. A comprehensive quantitative investigation of the photochromism is currently in progress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst16010038/s1, 1H and 13C NMR and Mass Spectra of the compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, synthesis, crystallization, writing original draft Y.L., synthesis S.A., X-ray crystallography, data collection, structure solving, refining, N.B. and J.R. Photochromic study Y.L. and Z.Y. Draft reviewing and correction, all the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Faculty RISE Program of Prairie View A&M University.

Data Availability Statement

The crystal data has been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC). CCDC 2505338-2505340 and 2505410 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (or from the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; Fax: +44-1223-336033; E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk). For any other information, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ESI-MS | Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectroscopy |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

| FPO | (E)-3-(1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethylidene)-4-(propan-2-ylidene) dihydrofuran-2,5-dione (FPO) |

| FPN | (E)-3-(1-(4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) ethylidene)-4-(propan-2-ylidene) dihydrofuran-2,5-dione |

| FPOP | (E)-3-(1-(4-phenoxyphenyl) ethylidene)-4-(propan-2-ylidene) dihydrofuran-2,5-dione |

| FPP | (E)-3-(1-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl) ethylidene)-4-(propan-2-ylidene) dihydrofuran-2,5-dione |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

References

- Fan, M.-G.; Yu, L.; Zhao, W. Fulgide Family Compounds: Synthesis, Photochromism, and Applications. In Organic Photochromic and Thermochromic Compounds: Volume 1: Main Photochromic Families; Crano, J.C., Guglielmetti, R.J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 141–206. [Google Scholar]

- Irie, M. Photochromism: Memories and SwitchesIntroduction. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1683–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, Y. Fulgides for Memories and Switches. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1717–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wang, B.; Gao, X.; Damjanovic, D.; Chen, L.-Q.; Zhang, S. Ferroelectric materials toward next-generation electromechanical technologies. Science 2025, 389, eadn4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Youn, S.; Kim, H. Recent advances in ferroelectric materials, devices, and in-memory computing applications. Nano Converg. 2025, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Wen, W.; Jiang, S. Ferroelectricity in organic materials: From materials characteristics to de novo design. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 13676–13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftory, M. Photochromic and thermochromic compounds. I. Structures of (E) and (Z) isomers of 2-isopropylidene-3-[1-(2-methyl-5-phenyl-3-thienyl)ethylidene]succinic anhydride, C20H18O3S, and the photoproduct 7,7a-dihydro-4,7,7,7a-tetramethyl-2-phenylbenzo[b]thiophene-5,6-dicarboxylic anhydride (P), C20H18O3S. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 1984, C40, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Huang, C.-R.; Xu, Z.-K.; Hu, W.; Li, P.-F.; Xiong, R.-G.; Wang, Z.-X. Photochromic Single-Component Organic Fulgide Ferroelectric with Photo-Triggered Polarization Response. JACS Au 2023, 3, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.D.; Kaufman, H.W.; Sinnreich, D.; Schmidt, G.M.J. Photoreactions of di-p-anisylidenefulgide (di-p-anisylidenesuccinic anhydride). J. Chem. Soc. B Phys. Org. 1970, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeyens, J.C.A.; Denner, L.; Perold, G.W. Rotamers and isomers in the fulgide series. Part 1. Stereochemistry and conformational analysis of bis-(3,4-dimethoxybenzylidene)succinic anhydrides by X-ray crystallography and molecular mechanics. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1988, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeyens, J.C.A.; Allen, C.C.; Perold, G.W. Rotamers and isomers in the fulgide series. Part 3. Structures of the bis(4-methoxy-3-methylbenzylidene)succinic anhydrides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, G.R.; Miller, A.J.M.; Sherden, N.H.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Nudelman, A.; Stoltz, B.M.; Bercaw, J.E.; Goldberg, K.I. NMR Chemical Shifts of Trace Impurities: Common Laboratory Solvents, Organics, and Gases in Deuterated Solvents Relevant to the Organometallic Chemist. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ming, Y.; Gong, F.; De, Y.; Yun, L. Synthesis and Photocroism of Aryl Substituted Fulgide. Acta Chim. Sin. 1996, 54, 716–721. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.