Abstract

In this study, the photocatalytic performance of natural clinoptilolite was enhanced through copper modification, achieved via ion exchange followed by KOH-induced precipitation, leading to materials with different copper speciation. Physicochemical characterization using WDXRF, PXRD, FTIR and N2 physisorption revealed a transition from exchanged Cu2+ species at low loading to the formation of copper-bearing phases such as brochantite, Cu(OH)2 and CuO at higher alkalinity. The Cu-modified samples were evaluated for the photocatalytic degradation of Congo red under UV irradiation. Among them, sample NZ-Cu3 exhibited the highest activity, achieving approximately 91% dye degradation within 30–40 min. Kinetic analysis demonstrated that the degradation process is better described by the pseudo-second-order model, indicating that chemisorption plays a dominant role. Radical scavenger experiments revealed that photogenerated holes (h⁺) are the primary reactive species responsible for dye degradation, while hydroxyl radicals contribute to a lesser extent. The enhanced photocatalytic performance is attributed to the synergistic effect of photocatalytic degradation, improved charge separation and the presence of surface copper species, highlighting Cu-modified clinoptilolite as a promising low-cost photocatalyst for wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have emerged as highly effective technologies for the removal of recalcitrant organic pollutants from wastewater due to their ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1], such as hydroxyl radicals, capable of non-selective oxidation and mineralization of complex contaminants [2,3]. Among AOPs, heterogeneous photocatalysis has attracted particular attention because it can operate under mild conditions and utilize solar or artificial light as a sustainable energy source [4]. Conventional photocatalysts, including TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4, have been widely investigated owing to their strong oxidative capability and chemical stability [5,6,7]. However, their practical application is often limited by drawbacks such as high production cost, particle agglomeration, low adsorption capacity toward organic pollutants, limited visible-light absorption, and difficulties associated with catalyst recovery and reuse [8,9]. In this context, natural zeolites have gained increasing interest as alternative or complementary materials in photocatalyzed AOPs. Zeolites are crystalline aluminosilicates with a three-dimensional microporous framework, high cation-exchange capacity, large specific surface area, and excellent thermal and chemical stability [10]. Among them, natural clinoptilolite is particularly attractive due to its wide availability, low cost, environmental compatibility, and strong affinity for cationic and polar organic species [11,12,13,14,15]. These characteristics make clinoptilolite an effective adsorbent and support material, capable of concentrating pollutants near reactive sites and enhancing degradation efficiency through an adsorption–photocatalysis synergy [16]. Despite these advantages, pristine natural zeolites exhibit limited intrinsic photocatalytic activity due to their wide band gap and weak light absorption in the visible region [17,18]. As a result, their direct use as standalone photocatalysts in AOPs is generally insufficient. To overcome these limitations, significant research efforts have focused on modifying natural zeolites with semiconductor phases or transition metals to improve their photoactivity [19]. Such modifications can introduce new electronic states, enhance charge separation, extend light absorption, and promote the generation of reactive oxygen species under irradiation. Transition metal modification [20,21], particularly with copper [22], has proven to be an effective strategy for enhancing the photocatalytic performance of natural zeolites [23]. Copper species, present as Cu2+ ions or CuO nanoparticles, can act as electron traps, reduce electron–hole recombination, and improve visible-light responsiveness [10,20,24,25]. When supported on clinoptilolite, copper species also benefit from strong metal–support interactions and uniform dispersion within the zeolite framework. This combination enables efficient pollutant adsorption, improved redox behavior, and enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants, including persistent azo dyes such as Congo Red [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Compared with conventional photocatalysts, Cu-modified natural clinoptilolite offers several practical advantages, including lower material cost, reduced environmental impact, improved adsorption capacity, and easier separation from treated water. At the same time, challenges such as limited intrinsic photoactivity and potential metal leaching must be carefully addressed through controlled synthesis and optimization of modification conditions. Consequently, the development of metal-modified natural zeolites represents a promising and sustainable approach within the broader framework of photocatalyzed AOPs for wastewater treatment.

The present this work presents the first systematic investigation of copper-modified natural clinoptilolite in which the evolution of copper speciation—from ion-exchanged Cu2+ to hydroxide and oxide phases induced by controlled alkalinity—is directly correlated with photocatalytic Congo red degradation performance. The study demonstrates how controlled Cu loading and phase composition govern degradation efficiency, reaction kinetics and dominant reactive species, providing new insight into the design of low-cost zeolite-based photocatalysts for wastewater treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Natural zeolite (NZ) used in this study was a clinoptilolite-rich tuff originating from the Beli Plast deposit, Bulgaria, with a particle size fraction <0.15 mm, supplied by Imerys Bulgaria (Imerys Minerals Bulgaria AD, Kardjali, Bulgaria). The mineralogical composition of the material consisted of approximately 86% clinoptilolite, 7% opal-CT, 2% mica (10 Å), 2% montmorillonite and 2% plagioclase [29].

Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, ≥99% purity) and potassium hydroxide (KOH, ≥98% purity) were used for copper modification and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Congo red (CR, analytical grade, ≥98% purity) was used as the model organic dye without further purification. Distilled water was used for the preparation of all solutions and for washing the modified zeolite samples.

2.2. Preparation of Cu-Modified Clinoptilolite

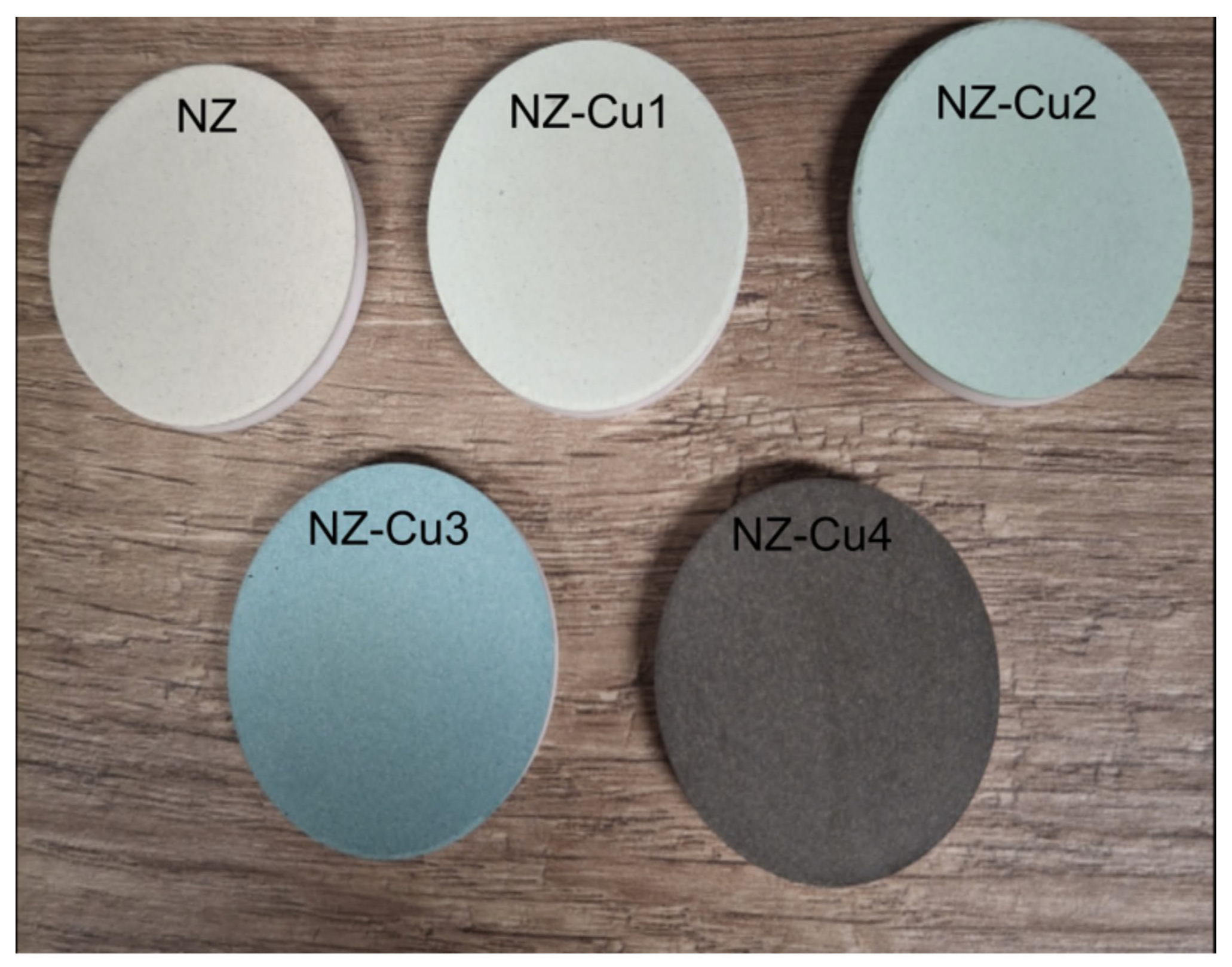

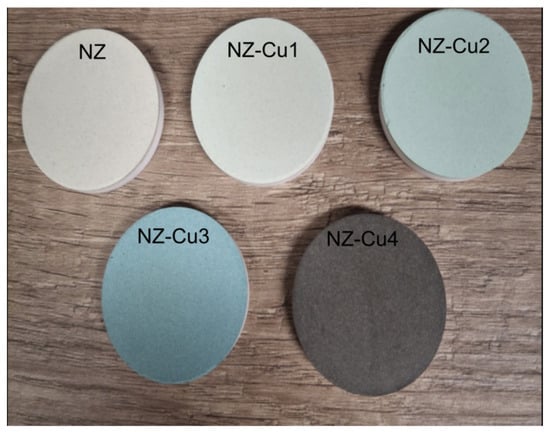

The copper modification of the natural zeolite (NZ) was achieved through an initial ion-exchange procedure (NZ-Cu1), followed by direct precipitation induced by KOH addition (NZ-Cu2 to NZ-Cu4). For the ion-exchange step, NZ was mixed with a 1 M CuSO4·5H2O solution at a ratio of 1:2.5 (w/w) at magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 2 h (NZ-Cu1). Subsequently, different amounts of concentrated KOH solution were gradually added under continuous stirring to produce samples NZ-Cu2 and NZ-Cu3. For series NZ-Cu4, KOH pellets were added directly to the mixture. After KOH addition, the suspensions were aged for 2 h under occasional stirring. An increase in KOH dosage resulted in a progressive rise in pH, which induced the precipitation of copper species. This process was accompanied by a characteristic color change of the suspension from pale blue to marine blue, and finally to black (NZ-Cu4) (Figure 1), consistent with the formation of copper hydroxide and/or oxide phases at elevated pH. The modified NZ samples were then filtered and thoroughly washed with distilled water. The compositions corresponding to each modification procedure are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Characteristic color change of the suspension from pale blue to marine blue, and finally to black (NZ-Cu4).

Table 1.

Composition of each modifying procedure.

2.3. Methods of Characterization

The chemical composition of the synthesized samples was determined on a Supermini200 WDXRF spectrometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). Data collection was performed at 50 kV and 4.00 mA. Each sample was crushed and then pressed to obtain a tablet. The sample/tablet was placed in a holder with an irradiated area of 30 mm in diameter. The weight ratio of the amount of sample to the amount of glue (Acrawax C powder) was 5:1. A semi-quantitative method (SQX) was used to determine the elemental composition.

Powder X-ray diffraction analysis was performed on Empyrean (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) diffractometer equipped with a PIXcel3D detector and copper X-ray source (CuKa = 1.5406 Å). The diffracting patterns were collected in the 3–70° 2Theta range, under operating conditions of 40 kV and 30 mA and a step size of 0.013°.

The specific surface area and porosity of NZ and Cu-modified NZ were analyzed using 3Flex surface analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). Before analysis, the samples were degassed in situ at 90 °C for 5 h under vacuum (>1.10–6 mmHg). The physisorption experiments were carried out under liquid nitrogen (77 K) using N2 probe molecule. Quantitative information for the specific surface area (S, m2·g−1), micropore volume (Vm, cm3·g−1), pore size distribution, etc., was obtained by analyzing the resulting N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms. Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) specific surface areas were calculated from adsorption data in the relative pressure range from 0.05 to 0.31 P/P0 [30]. The total pore volume was estimated based on the amount adsorbed at a relative pressure of 0.96 [31]. Micropore volumes were determined using the t-plot method [32] and the Horvath–Kawazoe micropore algorithm [33]. Pore size distributions (PSDs) were calculated from nitrogen adsorption data using an algorithm based on the ideas of Barrett, Joyner and Halenda (BJH) [34]. The mesopore diameters were determined as the maxima on the PSD for the given samples.

The samples were examined using a Tensor 37 (Bruker, Berlin, Germany) spectrometer using KBr pellets. For each sample, 128 scans were collected at a resolution of 2 cm−1 over the wavenumber region 4000–400 cm−1.

The spatial distribution of elements in the samples was examined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping in order to assess the dispersion of copper species. Images and SEM-EDS analyses were collected on a IT800SHL (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The two EDS detectors, (JED 2300) 100 mm2, enabled the possibility of high-sensitivity EDS analysis and acceleration voltage of 10 kV.

2.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Experiments

The effective photocatalytic degradation of the organic dye—Congo red—in the presence of Cu-substituted NZ was evaluated using UV-Vis spectroscopy. The details of the experiments were as follows: 50 mg of zeolite NZ and NZ-Cu1-4 was added to 10 mL of a 10 µg/mL CR dye solution and stirred for 30–60 min at ambient conditions. Photocatalytic experiments were carried out using a UV-A lamp with a dominant emission wavelength of 365 nm and a nominal power of 48 W. The lamp was positioned at a fixed distance of 5 cm above the reaction vessel. Although the irradiance at the sample surface was not measured directly, all experiments were conducted under identical irradiation geometry and conditions to ensure reproducibility. The absorption resulting from the photodegradation of the dye was monitored at 498 nm for CR, using DRAWELL spectrophotometer (DRAWELL, Chongqing, China) or Cary 4000 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The kinetics of the photodegradation reactions were examined based on the change in dye concentration by measuring the characteristic absorbance peak at different irradiation times. The efficiency of photodegradation was determined using the following equation [35,36]:

where C0 and C are the solution concentration at t = 0 and after some irradiation time.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of NZ and Cu-Modified Clinoptilolite

The chemical composition of the natural clinoptilolite (NZ) and the Cu-modified samples was determined by WDXRF, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The pristine NZ sample shows a typical aluminosilicate composition, dominated by SiO2 and Al2O3, with minor contributions from alkali and alkaline-earth oxides.

Table 2.

Elemental composition, detection limits, and standard error based on WDXRF for the natural zeolite (NZ) and Cu-modified samples (NZ-Cu1-4).

Copper incorporation results in a progressive increase in CuO content from 2.71 wt.% in the ion-exchanged sample (NZ-Cu1) to values exceeding 20 wt.% in the KOH-treated samples (NZ-Cu2–NZ-Cu4). At low copper loading, the modest changes in bulk composition are consistent with ion exchange of native extra-framework cations by Cu2+, as commonly reported for clinoptilolite [37,38,39,40]. The decrease in Na2O and CaO contents in NZ-Cu1 supports this exchange mechanism, whereas the K2O content remains largely unchanged due to the low exchangeability of K⁺ ions in the clinoptilolite framework [41,42,43,44]. At higher copper loadings (NZ-Cu2–NZ-Cu4), the sharp increase in CuO content is accompanied by a relative decrease in SiO2 and Al2O3, indicating the accumulation of copper-rich secondary phases on the zeolite surface rather than further framework substitution. In sample NZ-Cu2, the elevated SO3 content suggests the formation of sulfate-containing copper phases, while the significantly lower sulfate levels in NZ-Cu3 and NZ-Cu4 reflect a transition toward hydroxide- and oxide-type copper species under increasingly alkaline conditions. These compositional trends clearly demonstrate a shift from ion exchange to alkalinity-driven precipitation as the dominant modification mechanism.

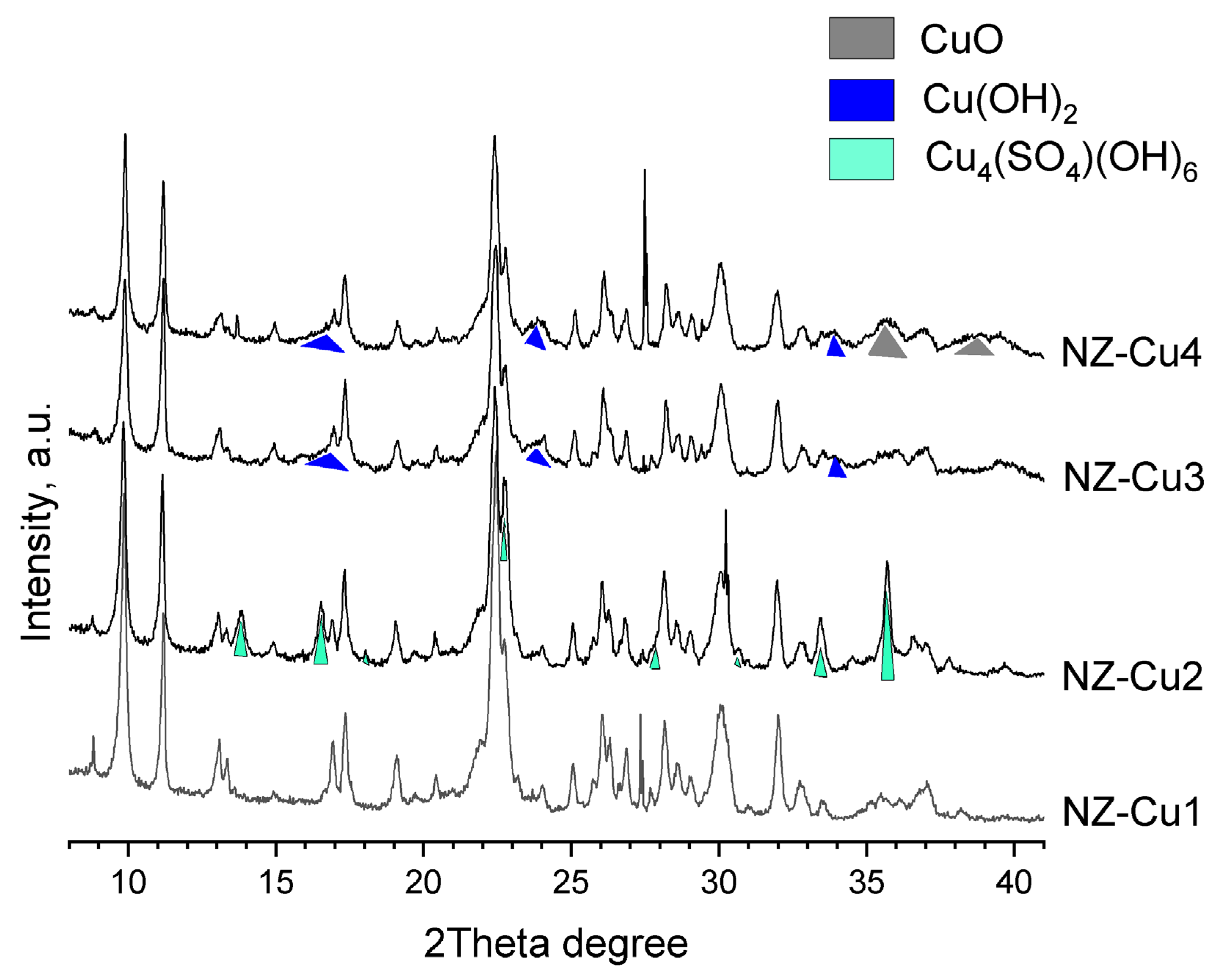

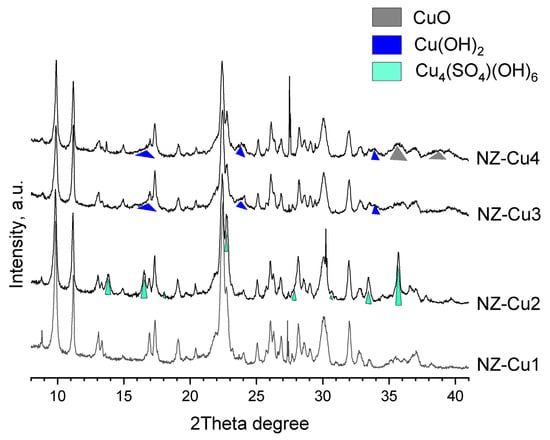

The phase composition and structural evolution of the samples were investigated by PXRD, and the diffraction patterns are presented in Figure 2. The diffraction peaks were indexed using the ICDD Powder Diffraction. The pristine NZ and the ion-exchanged sample NZ-Cu1 exhibit diffraction patterns characteristic of clinoptilolite, with no detectable structural degradation or formation of new crystalline phases, within the experimental uncertainty of the PXRD measurements, confirming that the ion-exchange process preserves the zeolite framework. In contrast, samples obtained after KOH treatment show the appearance of additional reflections associated with copper-containing phases. In NZ-Cu2, reflections corresponding to brochantite (Cu4SO4(OH)6) are clearly observed, in agreement with the elevated sulfate content detected by WDXRF. Upon further increase in alkalinity (NZ-Cu3), brochantite is replaced by copper hydroxide, Cu(OH)2, indicating sulfate removal and stabilization of hydroxide phases at higher pH [41]. For the NZ-Cu4 sample, the direct addition of KOH pellets leads to strongly alkaline and locally exothermic conditions, promoting the partial transformation of Cu(OH)2 into tenorite (CuO) [45,46,47,48]. The diffraction peaks of the copper phases are notably broadened, suggesting nanoscale crystallite size and/or reduced crystallinity. Importantly, the clinoptilolite structure remains largely intact in all samples, while the broad amorphous halo associated with opal-CT decreases in intensity for the highly alkaline samples, indicating partial dissolution of amorphous silica under strong alkaline conditions. These results confirm that controlled alkalinity enables systematic tuning of copper phase composition on the clinoptilolite surface without significant framework collapse.

Figure 2.

X-ray powder diffraction of patterns of the studied samples. File database: PDF 00-039-1383 clinoptilolite [49], PDF 01-087-0454 brochantite [50], PDF 48-1548 tenorite [51] and PDF 01-080-0656 spertiniite [52].

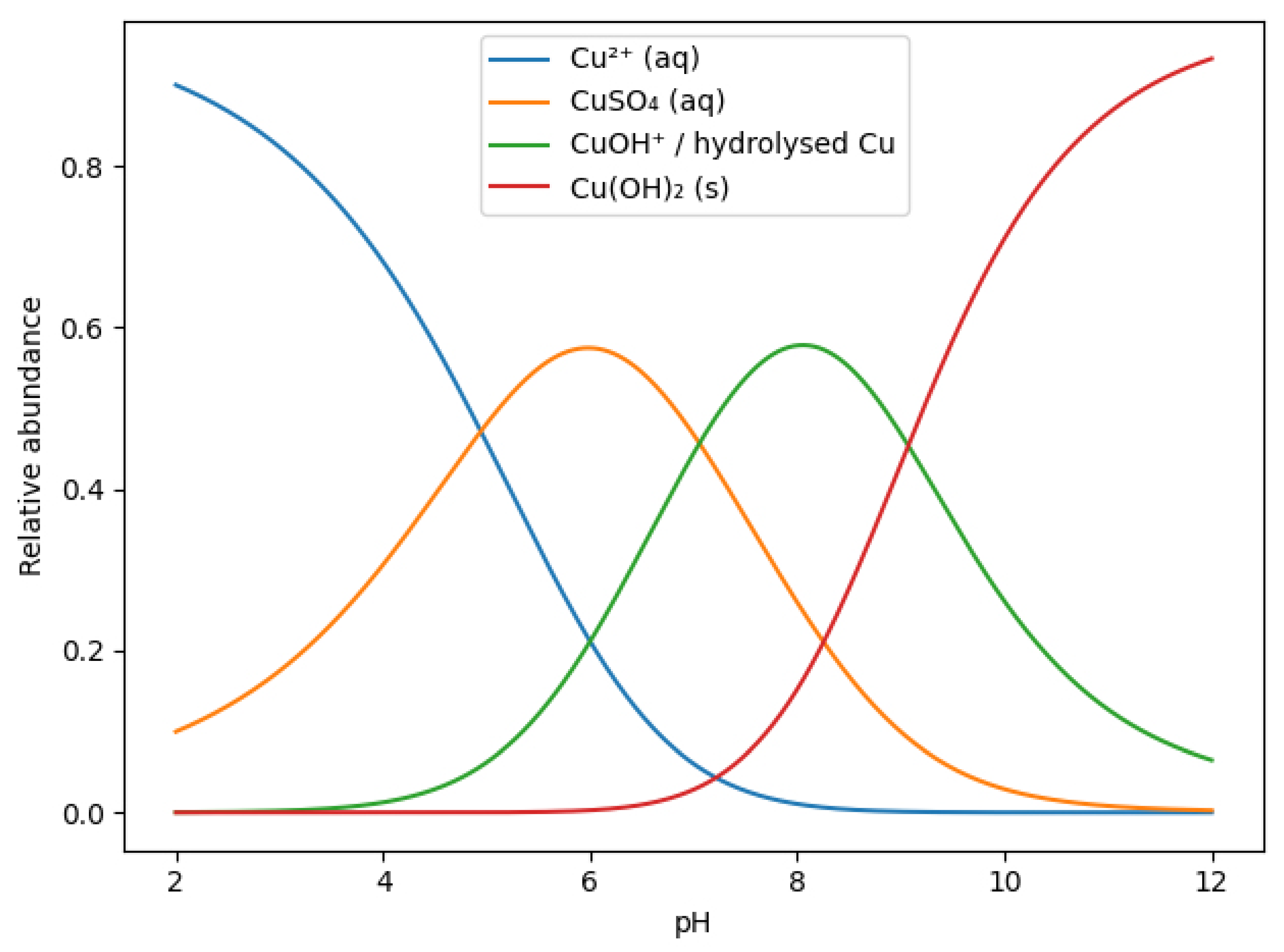

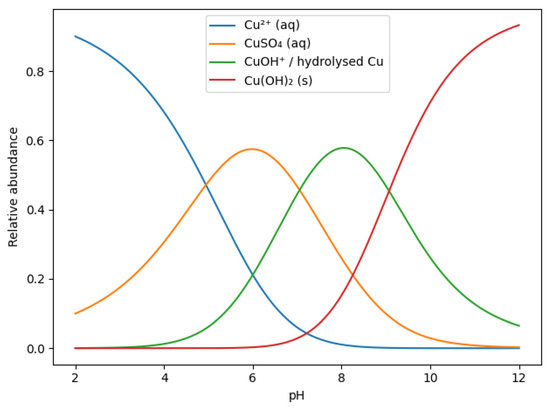

To better rationalize the pH-dependent evolution of copper-containing phases, a species distribution diagram for the Cu–SO4–OH system was considered (Figure 3) [53,54]. At low pH values, copper is predominantly present as solvated Cu2+ ions and sulfate complexes (CuSO4(aq)). With increasing pH, progressive hydrolysis of Cu2+ occurs, leading to the formation of hydrolyzed copper species (e.g., CuOH⁺), which favors the nucleation of basic copper sulfate phases such as brochantite. At higher pH values, the stability of sulfate-containing species decreases, and copper hydroxide, Cu(OH)2(s), becomes the thermodynamically favored phase, consistent with the experimental PXRD observations. Under strongly alkaline conditions, further transformation of Cu(OH)2 into CuO may occur due to dehydration, particularly under locally exothermic conditions. The species diagram thus supports the experimentally observed phase transitions and confirms the decisive role of alkalinity in controlling copper speciation and phase composition on the clinoptilolite surface.

Figure 3.

pH-dependent species distribution diagram of copper in the Cu–SO4–OH system, illustrating the relative abundance of aqueous Cu2+, CuSO4(aq), hydrolyzed copper species, and solid Cu(OH)2.

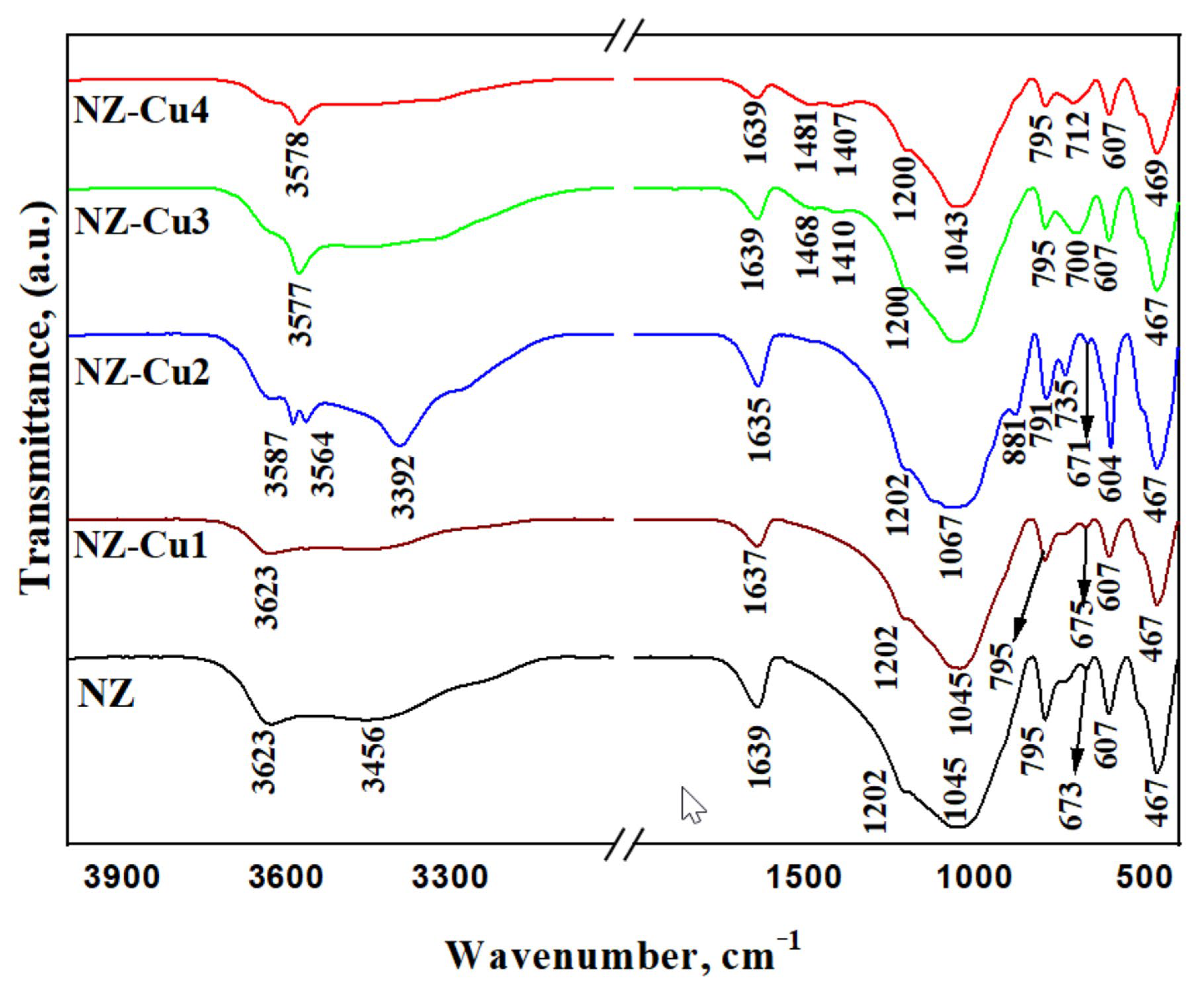

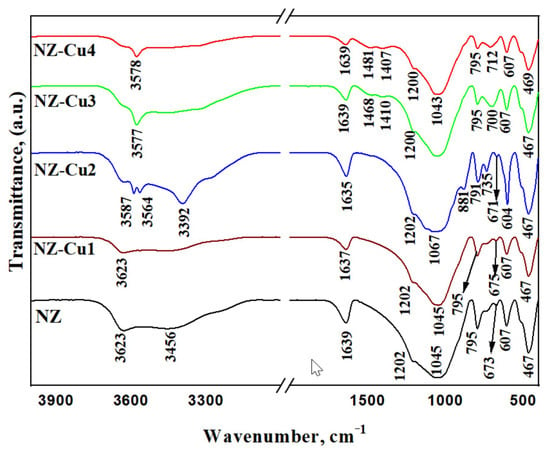

FTIR spectra of NZ and Cu-modified samples are shown in Figure 4. The spectrum of pristine NZ displays characteristic bands of clinoptilolite, including the sharp OH stretching band at ~3623 cm−1 and the broader band around 3450 cm−1 associated with adsorbed water. Upon copper modification, these bands shift and broaden, indicating perturbation of the zeolitic OH groups [55,56] and hydration environment due to Cu2+ coordination. Changes are also observed in the framework vibration region (1200–1000 cm−1), corresponding to asymmetric Si–O–(Al) stretching modes. The gradual shift and decrease in intensity of these bands with increasing copper loading suggest local framework distortion and surface coverage by copper-containing phases. Additional bands appearing in the low-frequency region (800–400 cm−1) for Cu-rich samples are attributed to metal–oxygen vibrations of copper hydroxide and oxide species, consistent with the PXRD results. Overall, the FTIR analysis supports the coexistence of exchanged Cu2+ species at low loading and precipitated copper phases at higher alkalinity.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of patterns of the studied samples.

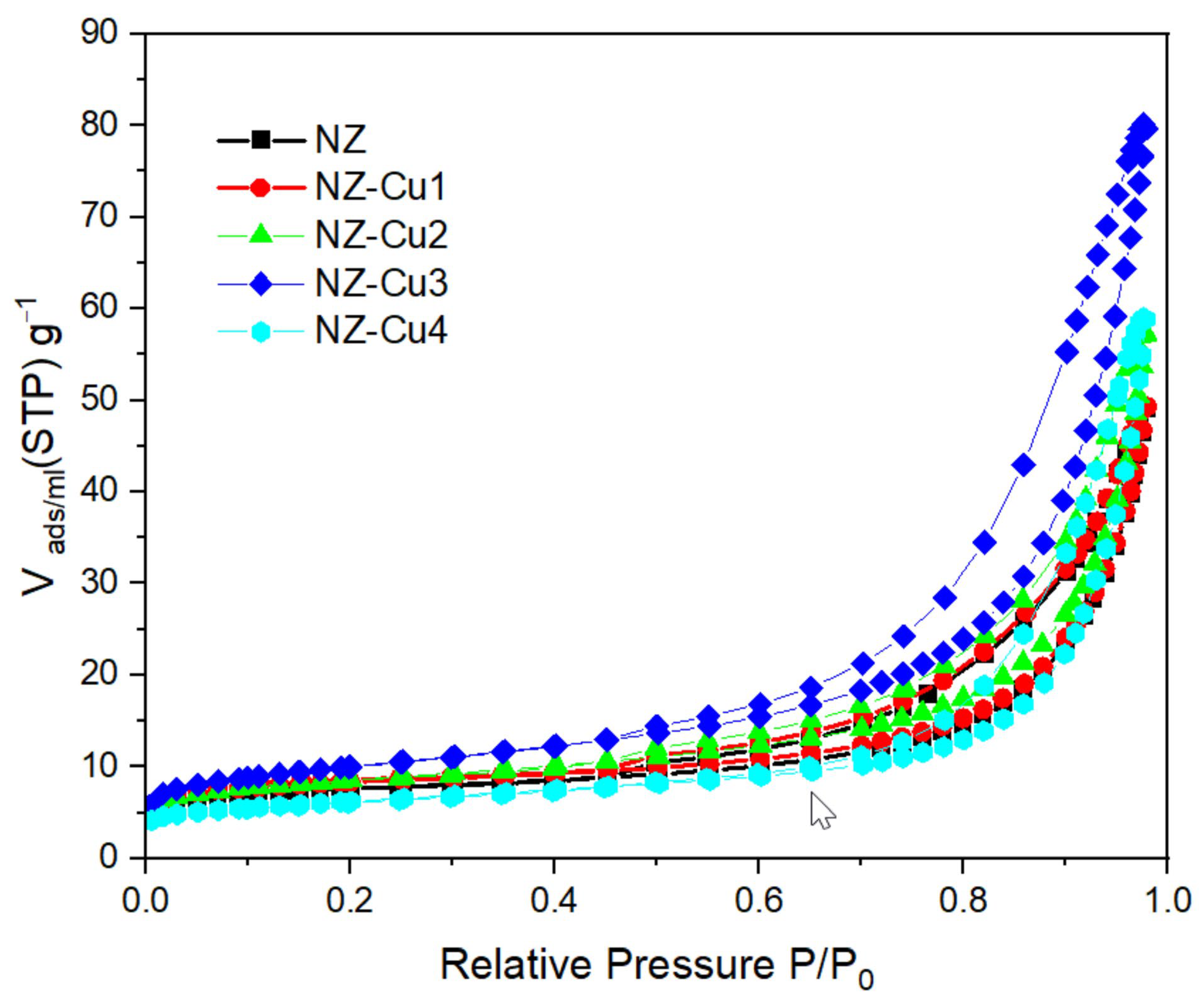

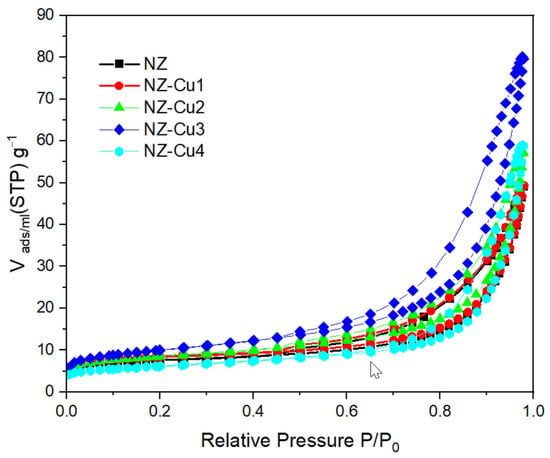

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of NZ and Cu-modified samples are presented in Figure 5, and the corresponding textural parameters are summarized in Table 3. All samples exhibit type IV isotherms with H3 hysteresis loops, characteristic of mesoporous materials with slit-like pores formed by particle aggregation [31]. Compared to pristine NZ, the Cu-modified samples show notable changes in surface area and pore structure. Moderate copper loading (NZ-Cu1 and NZ-Cu2) results in a slight increase in BET surface area, suggesting improved accessibility of mesoporous. The NZ-Cu3 sample exhibits the highest surface area and pore volume, indicating that controlled precipitation of copper phases can enhance textural properties and facilitate mass transfer during photocatalytic reactions. In contrast, the decrease in surface area observed for NZ-Cu4 suggests partial pore blockage or agglomeration at excessive copper loading. These textural trends correlate well with the observed photocatalytic performance.

Figure 5.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherms for patterns of the studied samples.

Table 3.

Textural parameters for NZ and NZ-Cux as deduced from nitrogen adsorption isotherms.

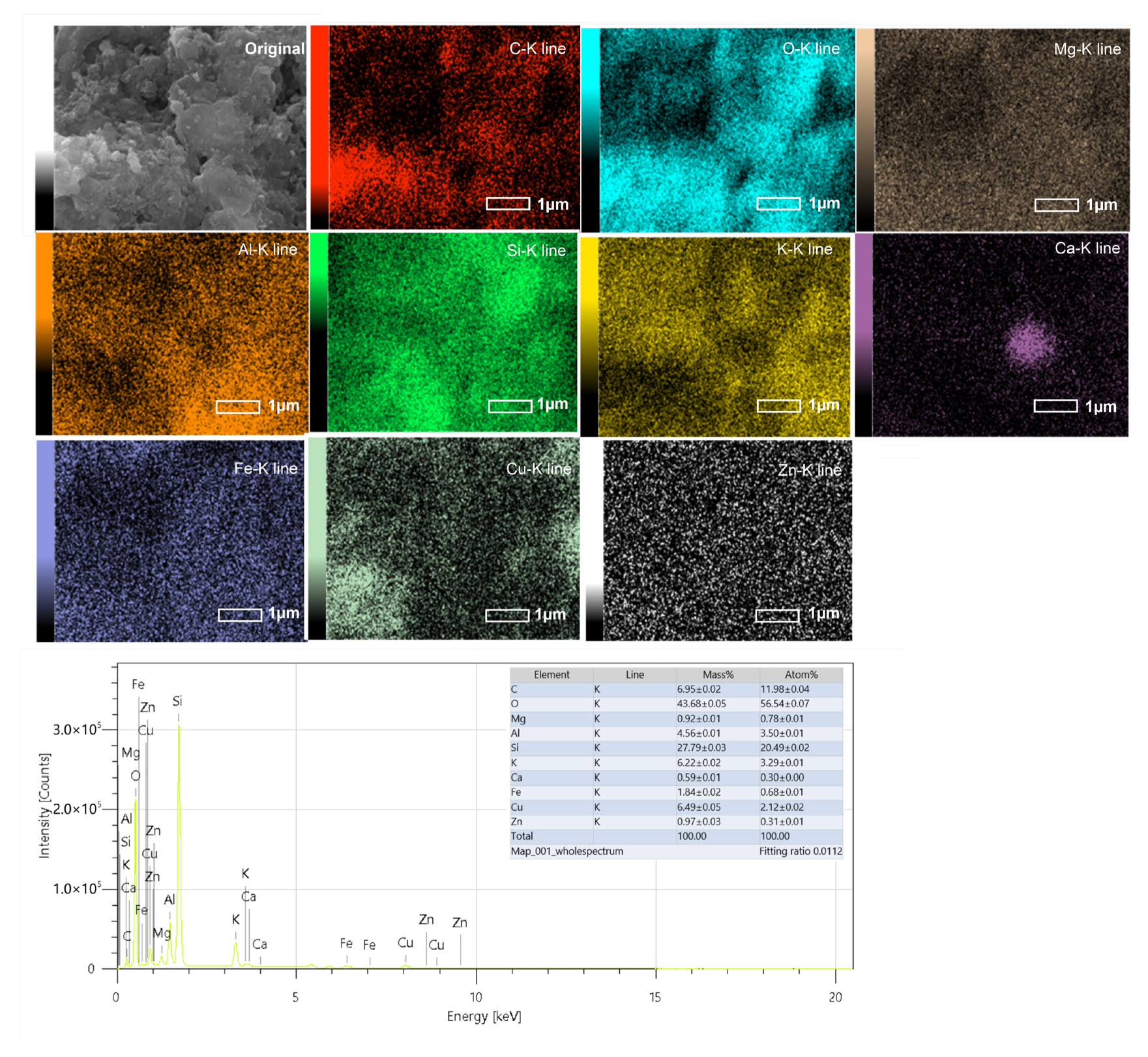

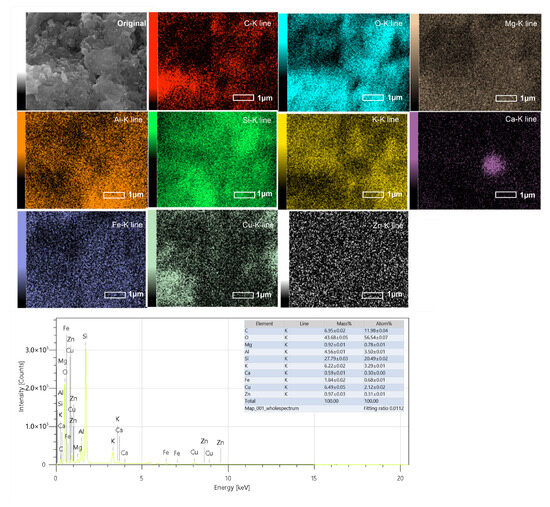

EDS elemental mapping (Figure 6) of the representative sample NZ–Cu3 confirms a homogeneous distribution of Cu across the clinoptilolite surface without the formation of pronounced Cu-rich agglomerates. This observation indicates that, at intermediate Cu loading, copper species are well dispersed and effectively associated with the zeolite surface. Such uniform Cu distribution is consistent with the enhanced photocatalytic activity observed for NZ–Cu3 and supports the claim of modified surface properties without excessive surface coverage or pore blocking.

Figure 6.

EDS elemental mapping of the NZ-Cu3 sample. MAP 1 pptx was used for the images.

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity of Patterns of the Studied Samples

3.2.1. Photodegradation of Congo Red

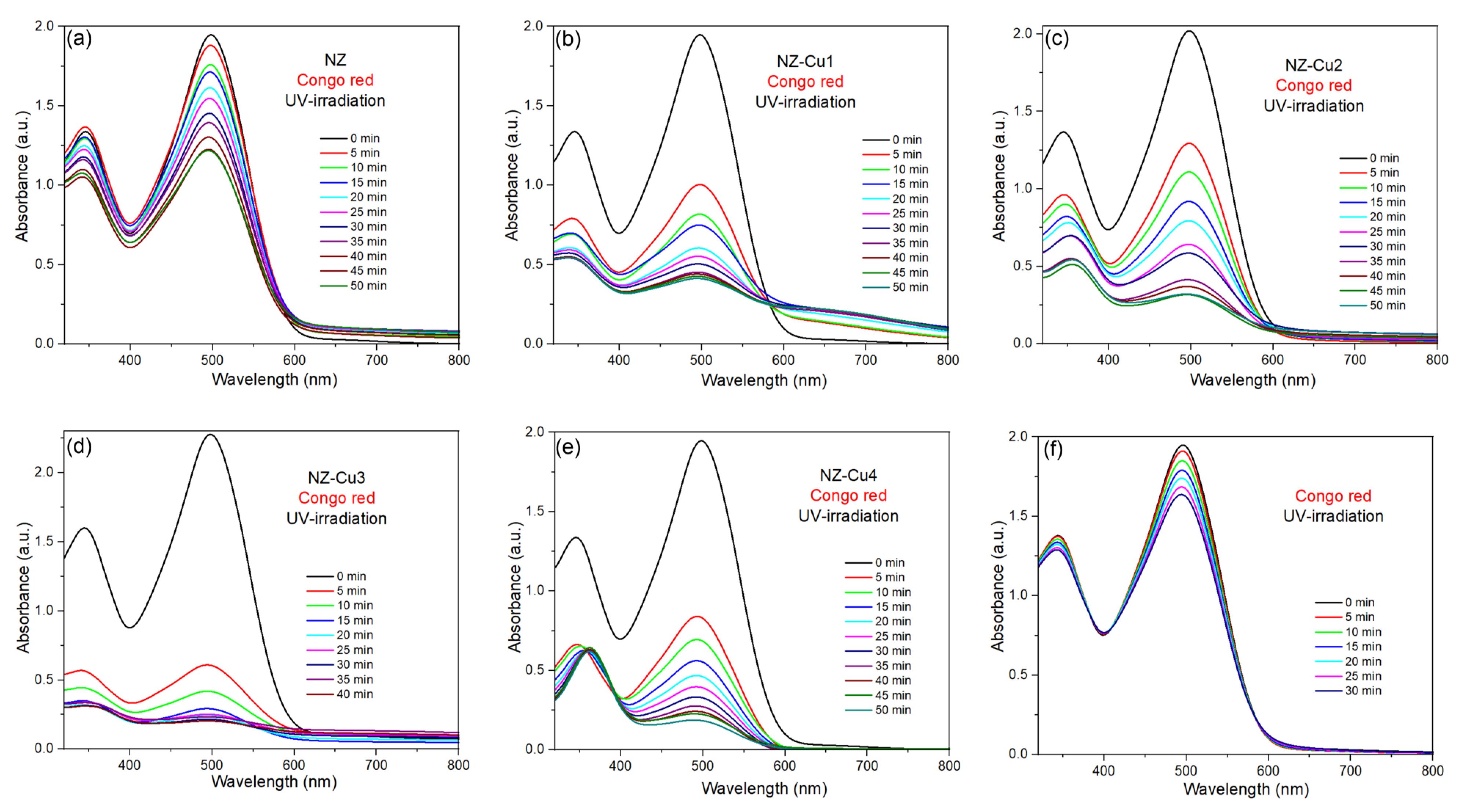

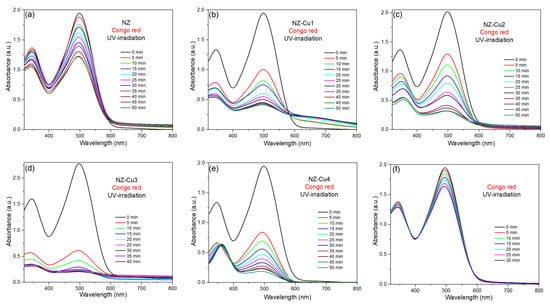

Figure 7a–f show the time-dependent UV–Vis absorbance spectra of aqueous solution of organic dye—CR—under UV—irradiation in the presence of NZ, NZ-Cu1, NZ-Cu2, NZ-Cu3 and NA-Cu4 catalysts. To evaluate the contribution of direct photolysis, control experiments were performed under UV irradiation (365 nm) in the absence of any catalyst (Figure 7). The results show that Congo Red exhibits negligible degradation under UV light alone, with only a marginal decrease in concentration over the irradiation period. This indicates that CR is not significantly photosensitive under the applied UV-A irradiation conditions. In all cases of catalist, the intensity of the characteristic absorption peaks of the dye decreases progres-sively with increasing irradiation time, indicating the photocatalytic degradation of the dye. The main absorption band correspond to the chromophore structures of dye: around 498 nm for CR. For the parent NZ catalyst, the gradual decrease in absorbance is observed for dye, demonstrating that NZ exhibits photocatalytic activity under UV—irradiation. However, complete degradation of the dye requires relatively long irradiation times (30–50 min, depending on the catalysis). After Cu incorporation in NZ catalyst the absorbance of dye decreases more rapidly compared to parent NZ, confirming that Cu doping enhances photocatalytic performance. Almost complete decolorization is achieved in a shorter time (e.g., 30–40 min for NZ-Cu3). This improvement can be attributed to enhanced UV light absorption and improved charge separation efficiency in the Cu-modified catalyst, which promotes more effective generation of reactive oxygen species responsible for dye degradation. The minimal photolytic removal confirms that the substantial degradation observed in the presence of Cu-modified clinoptilolite cannot be attributed to direct UV-induced dye decomposition. Instead, the removal of CR predominantly originates from photocatalytic processes involving the Cu-containing active phases and photogenerated charge carriers. These findings demonstrate that photolysis plays a negligible role and validate the interpretation of the degradation kinetics as true photocatalytic activity.

Figure 7.

UV-Vis analysis of the photodegradation processes of Congo red promoted by (a) NZ, (b) NZ-Cu1, (c) NZ-Cu2, (d) NZ-Cu3, (e) NZ-Cu4 and (f) only CR on UV irradiation.

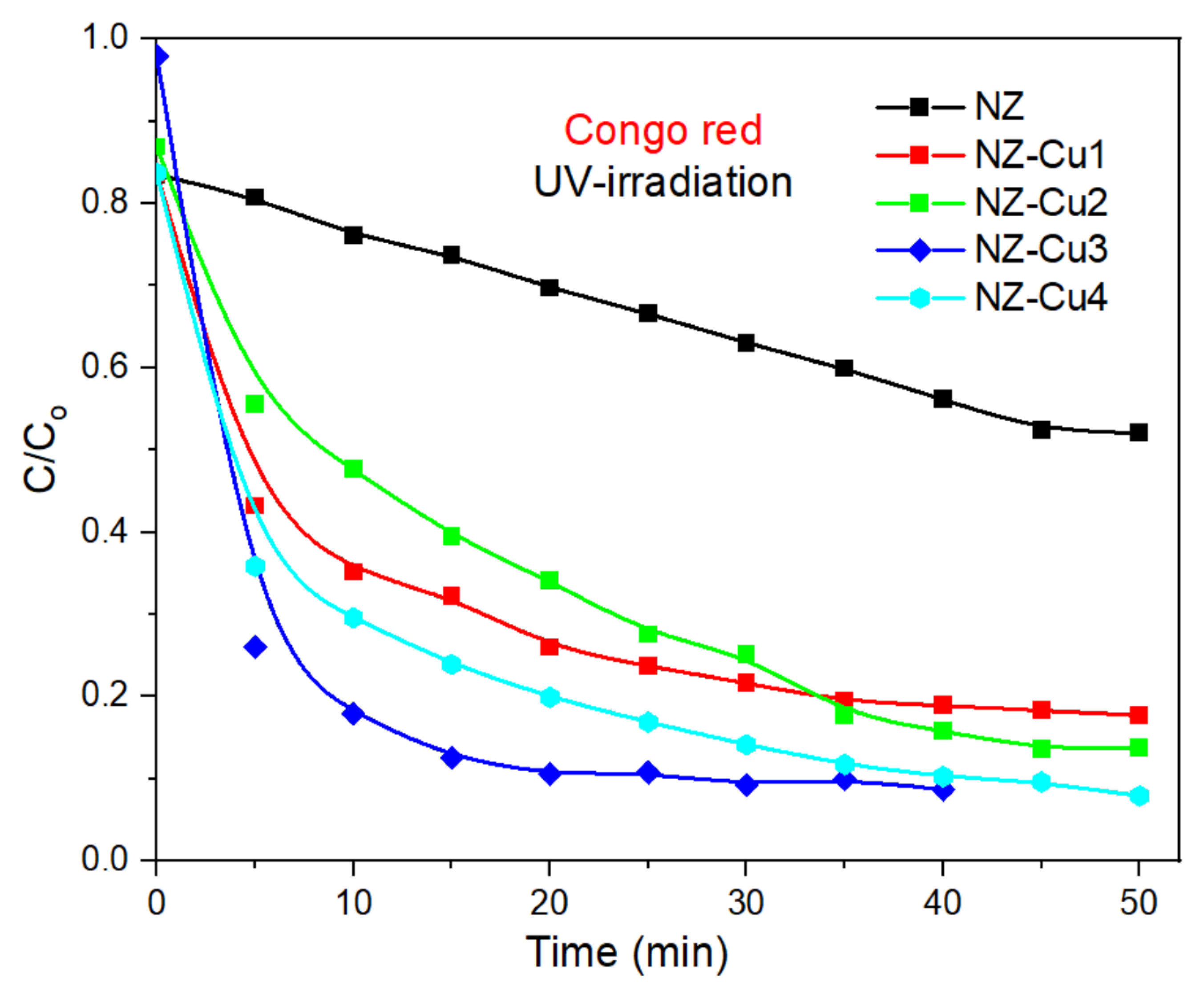

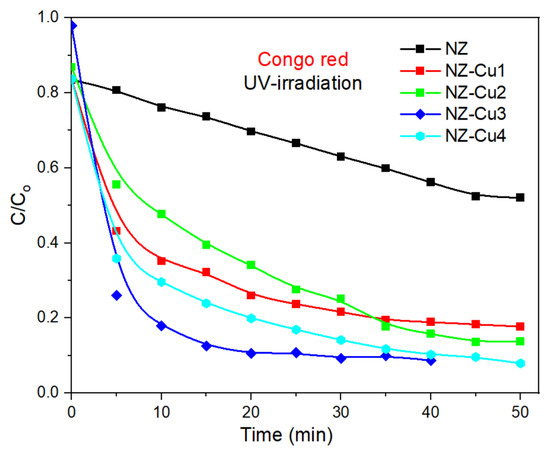

3.2.2. Photodegradation Efficiency

Figure 8 illustrates the photocatalytic degradation profile of CR under white UV—irradiation using NZ and Cu-modified NZ catalysts (NZ-Cu1, NZ-Cu2, NZ-Cu3 and NZ-Cu4). The concentration ratio (C/C0) represents the normalized dye concentration at time t, where C0 is the initial concentration and C is the concentration at a given irradiation time. In all cases, the dye concentration decreases gradually with in-creasing irradiation time, indicating successful photocatalytic degradation. The rate and extent of degradation vary depending on the type and amount of Cu incorporated into the NZ framework. Congo red (Figure 8) all catalysts show a significant decrease in C/C0 over time without the parent NZ, confirming photocatalytic activity. NZ-Cu3 exhibits the highest degradation efficiency, reaching nearly complete degradation within 30–40 min. The NZ-Cu4 sample shows a slower degradation rate, likely due to excess Cu content causing a reduction in active sites or increased charge recombination. These results suggest an optimal Cu loading (NZ-Cu3) for enhancing photocatalytic performance.

Figure 8.

Photodegradation of Congo red promoted by UV irradiation in the presence of NZ (black), NZ-Cu1 (red), NZ-Cu2 (green), NZ-Cu3 (blue) and NZ-Cu4 (cyan); the line connecting the dots is provided as a guide for the eye.

3.2.3. Kinetic Studies

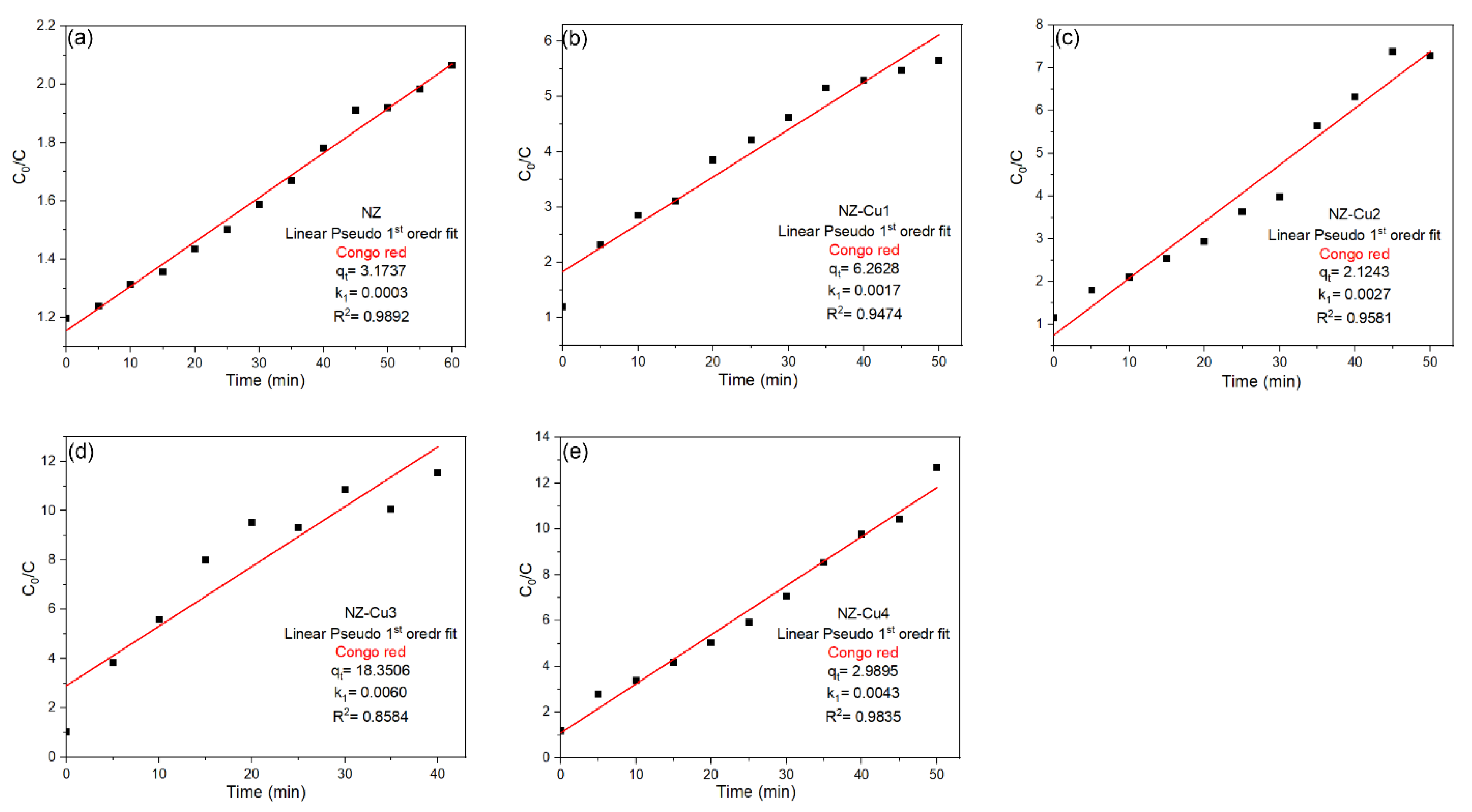

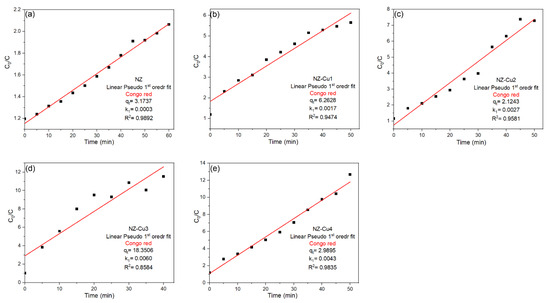

The photocatalytic degradation kinetics of CR over the NZ and Cu-modified NZ catalysts were evaluated using the linear pseudo-first-order (PFO) kinetic model, expressed as [57]:

where C0 and C are the initial dye concentration and the concentration at time t, respectively, and k1 (min−1) is the apparent rate constant. The linear fits obtained for NZ, NZ-Cu1, NZ-Cu2, NZ-Cu3 and NZ-Cu4 is presented in Figure 9. The pseudo-first-order plots ln(C0/C) vs. time show linear fits for all samples, but the quality of the fit (R2 values) varies considerably. For the pristine NZ sample, a reasonably good linear correlation was obtained (R2 ≈ 0.99), indicating that the PFO model can provide an approximate description of the degradation behavior at low activity levels. The Cu-modified samples NZ-Cu1 and NZ-Cu2 also exhibit moderate linearity (R2 ≈ 0.94–0.96), suggesting partial agreement with first-order kinetics. However, for the most active catalyst, NZ-Cu3, the PFO model shows a noticeably lower correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.858), indicating that this model does not adequately describe the degradation kinetics under conditions of enhanced photocatalytic activity. A similar deviation, although less pronounced, is observed for NZ-Cu4. These results suggest that while the PFO model may provide a preliminary approximation of the degradation process, it fails to consistently describe the kinetic behavior across all samples, particularly for systems with high copper loading and improved surface reactivity.

Figure 9.

Linear PFO kinetic models fits for the adsorption of CR on (a) NZ, (b) NZ-Cu1, (c) NZ-Cu2, (d) NZ-Cu3 and (e) NZ-Cu4.

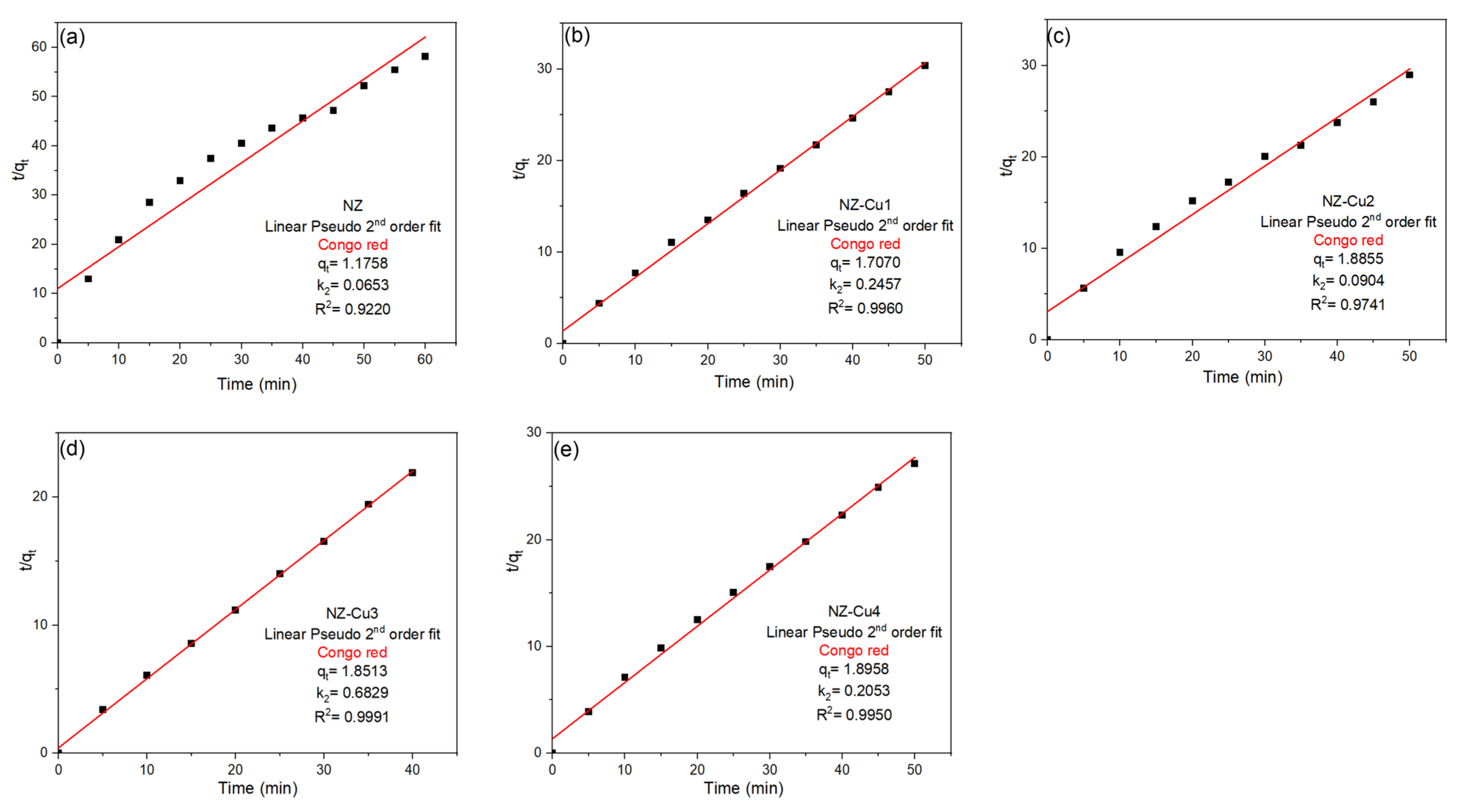

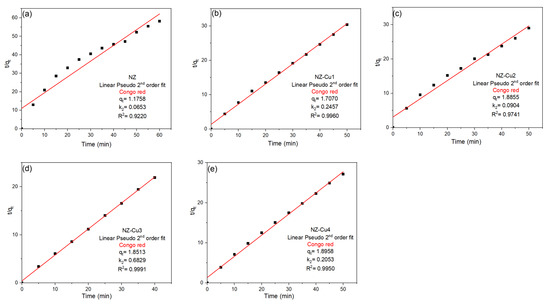

To gain deeper insight into the degradation mechanism, the experimental data were further analyzed using the pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetic model. The linear plots of t/qt versus irradiation time (Figure 10) exhibit excellent linearity for all samples, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.922 for NZ to values exceeding 0.97 for all Cu-modified materials. Notably, the highest linearity is observed for NZ-Cu3 (R2 = 0.999), indicating an almost perfect fit of the PSO model. In addition to superior correlation coefficients, the PSO model yields more consistent and physically meaningful values of the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) and rate constant (k2) compared to the PFO model. The enhanced kinetic parameters observed for the Cu-modified samples, particularly NZ-Cu3 and NZ-Cu4, reflect the increased availability of active sites and stronger interaction between Congo red molecules and the catalyst surface. The better agreement with the pseudo-second-order model suggests that the degradation process is governed primarily by chemisorption, involving electron sharing or transfer between dye molecules and surface-active sites, rather than by simple physical adsorption or diffusion-controlled processes. Similar kinetic behavior has been reported for dye degradation on metal-modified zeolites and oxide-based photocatalysts [57,58]:

where qt and qe (mg g−1) represent the amount of dye adsorbed at time t and at equilibrium, respectively, and k2 (g mg−1 min−1) is the rate constant.

Figure 10.

Linear PSO kinetic models fits for the adsorption of CR on (a) NZ, (b) NZ-Cu1, (c) NZ-Cu2, (d) NZ-Cu3 and (e) NZ-Cu4.

Overall, the kinetic analysis demonstrates that copper modification significantly enhances both the degradation rate and adsorption capacity, with NZ-Cu3 exhibiting the most favorable kinetic performance. The dominance of pseudo-second-order kinetics is consistent with the proposed photocatalytic mechanism involving strong surface interactions and efficient charge carrier utilization.

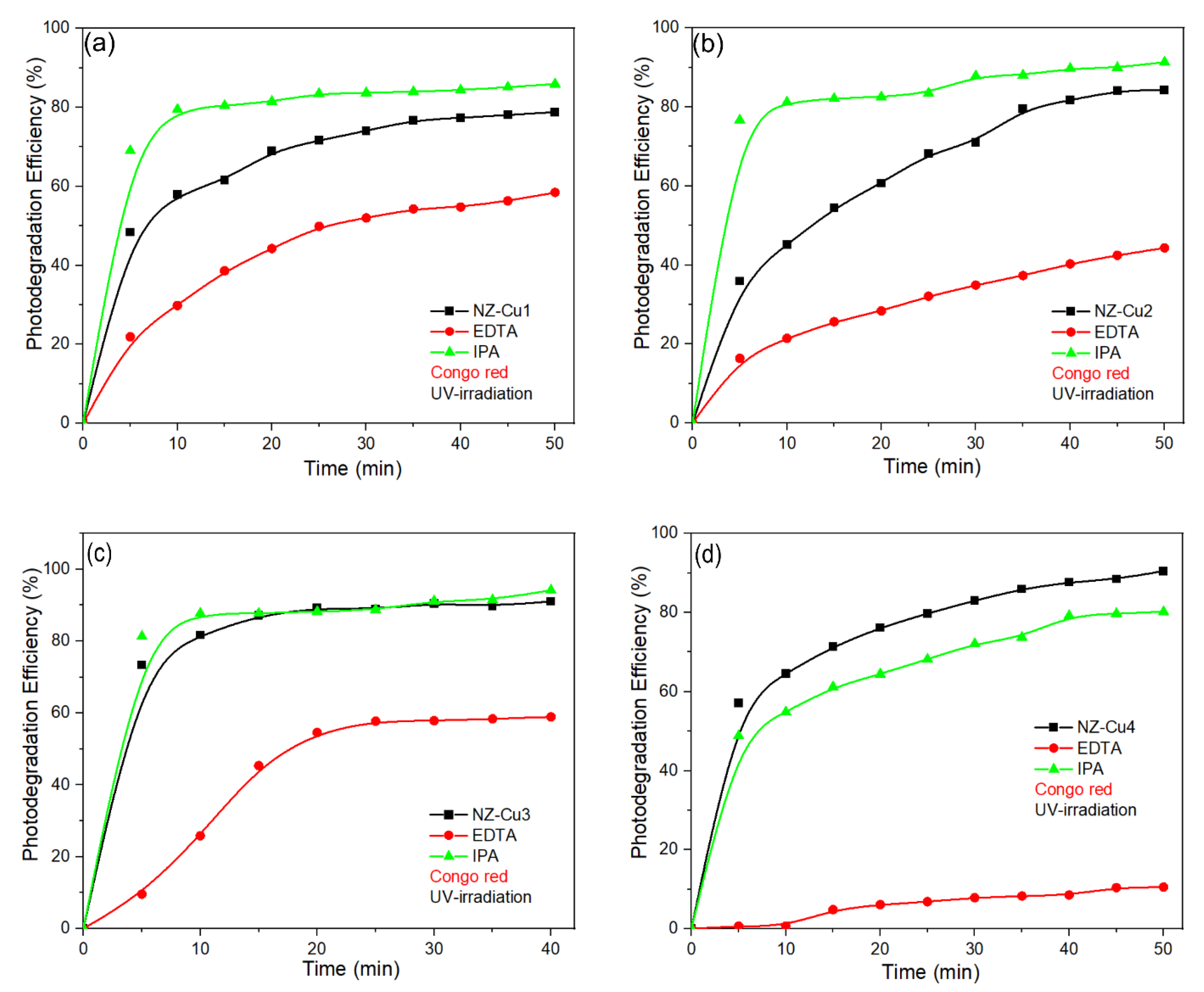

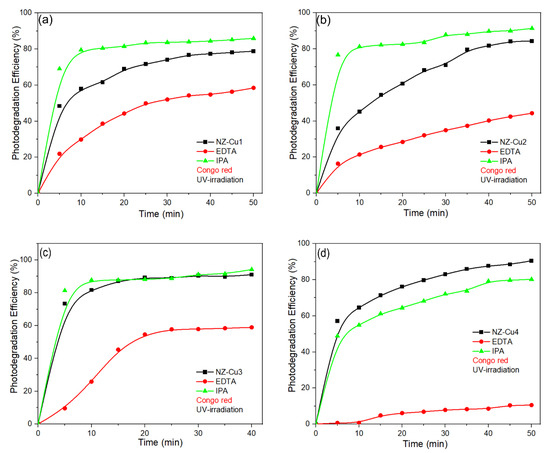

3.2.4. Photocatalytic Reaction Mechanism of Congo Red on NZ and NZ/Cux

The scavenger experiments provide important insight into the photocatalytic mechanism and can be rationalized by considering the electronic properties and interfacial charge-transfer processes in the Cu-modified clinoptilolite system (Figure 11). Although clinoptilolite itself is not a semiconductor in the classical sense, it acts as a high-surface-area support that promotes dispersion of Cu-containing phases and provides adsorption sites for dye molecules, thereby facilitating interfacial charge reactions. Upon irradiation, Cu-containing species (Cu2+/Cu(OH)2/CuO, depending on the sample) act as the primary photoactive components. According to literature reports, CuO is a narrow-band-gap p-type semiconductor (Eg ≈ 1.2–1.7 eV) with a valence band position sufficiently positive to enable direct oxidation of organic molecules by photogenerated holes, while the conduction band lies close to or below the O2/•O2− redox potential, limiting superoxide formation. Similar band alignments and charge-transfer behavior have been reported for Cu oxide–based photocatalysts forming type-II heterojunctions with oxide supports, where holes accumulate on the Cu-containing phase and dominate the oxidation pathway. In the present system, the drastic suppression of photocatalytic activity in the presence of EDTA for all Cu-modified samples clearly demonstrates that photogenerated holes (h⁺) are the main oxidative species responsible for Congo Red degradation. This observation is consistent with a hole-driven oxidation mechanism occurring at the Cu-containing surface domains, which act as anodic sites. In contrast, the relatively weak effect of isopropanol indicates that hydroxyl radicals (•OH) play only a secondary role, likely originating from surface-bound hydroxyl groups rather than bulk radical generation. In contrast, the addition of IPA caused only a moderate reduction in photocatalytic activity, indicating that hydroxyl radicals contribute to the degradation process but are not the primary reactive species. For samples with lower Cu loading, the addition of IPA can improve charge separation by partially scavenging photogenerated holes and suppressing electron–hole recombination, leading to a slight increase in degradation efficiency. At higher Cu loadings (NZ–Cu3 and NZ–Cu4), hole-driven oxidation pathways dominate, and the scavenging effect of IPA does not enhance photocatalytic performance. Among the catalysts, NZ–Cu3 demonstrated the highest intrinsic activity, which remained relatively high even in the presence of IPA. Among the investigated samples, NZ–Cu3 exhibits the highest activity, which can be attributed to an optimal balance between Cu dispersion, interfacial charge separation, and availability of surface oxidation sites. Excessive Cu loading, as in NZ–Cu4, likely introduces recombination centers and partial surface coverage, reducing the number of accessible anodic sites despite higher Cu content. Overall, the experimental results are consistent with a photocatalytic mechanism dominated by direct dye oxidation by photogenerated holes on Cu-containing phases, analogous to Cu oxide–based type-II heterojunction systems reported in the literature [59,60,61].

Figure 11.

The effect of EDTA and IPA scavengers on the degradation process of CR on (a) NZ-Cu1, (b) NZ-Cu2, (c) NZ-Cu3 and (d) NZ-Cu4, the line connecting the dots is provided as a guide for the eye.

The negligible photolysis of CR under UV-A irradiation further supports a hole-driven photocatalytic mechanism, where dye oxidation occurs primarily at the catalyst surface rather than via direct photon absorption by the dye molecules.

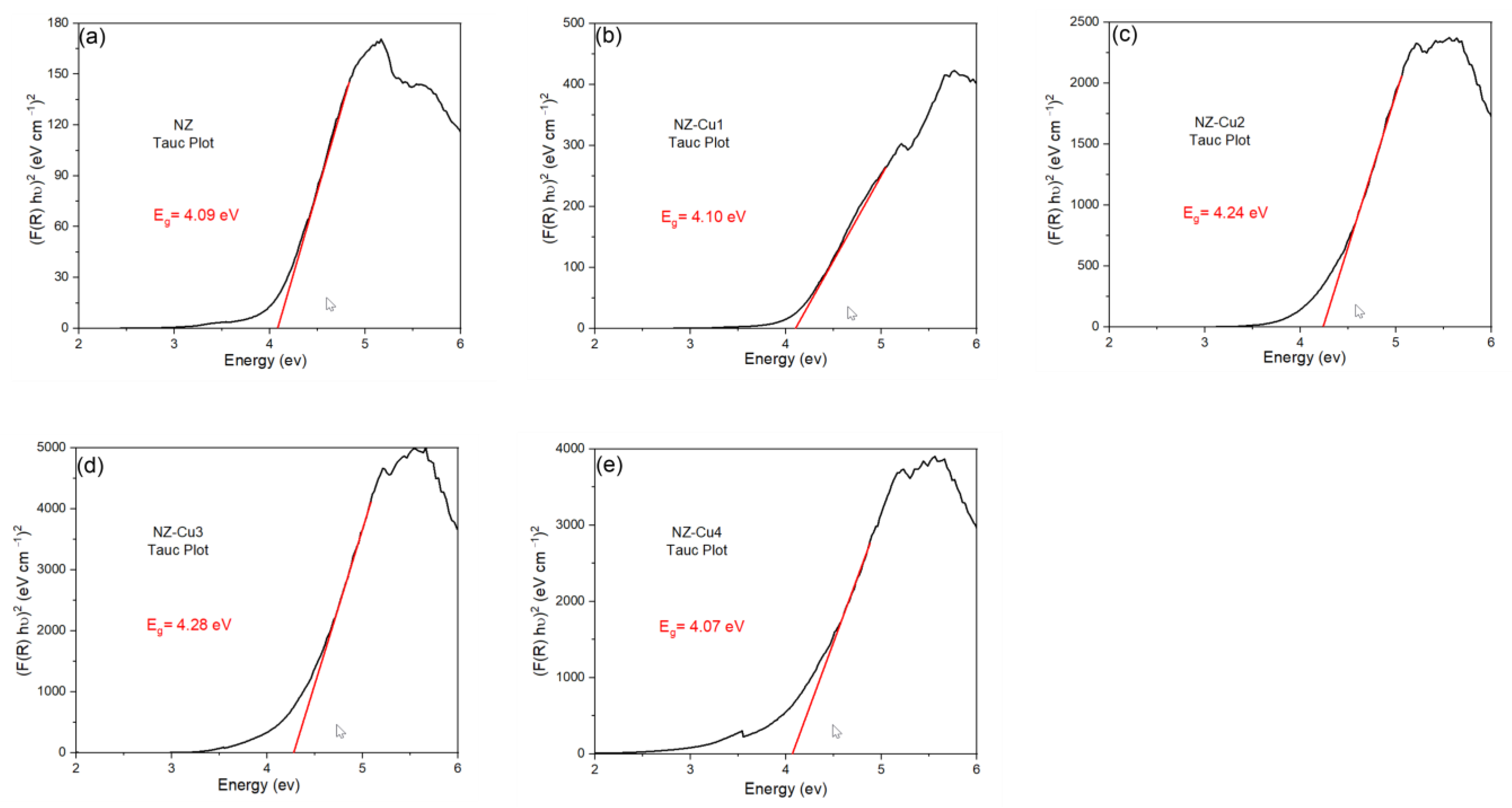

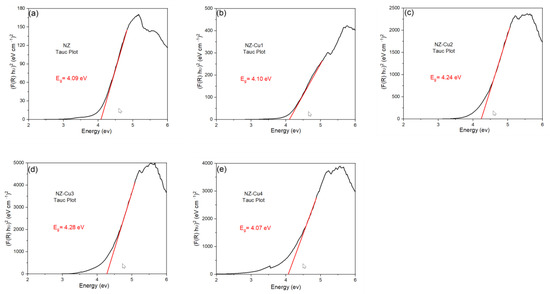

Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) was employed to evaluate the optical properties and determine the band gap energies of the as-synthesized samples. The band gap values were estimated from the DRS data using the Kubelka–Munk function, which relates the reflectance of a powdered sample to its absorption characteristics (Figure 12) [62]. The band gap energy (Eg) of natural clinoptilolite was determined to be 4.09 eV, which is characteristic of wide-bandgap insulating aluminosilicates. These variations indicate that Cu incorporation causes minor modifications of the electronic structure. The slight increase in Eg for some samples (e.g., NZ-Cu3) may be associated with the formation of CuOₓ species or changes in local coordination within the zeolite framework. The slightly lower Eg for NZ-Cu4 suggests stronger interaction between Cu species and the substrate or the presence of defect states. Although the band gaps remain relatively high, the introduction of Cu enhances photocatalytic activity by generating additional surface redox sites and improving charge separation rather than by significantly narrowing the optical band gap.

Figure 12.

Energy band gap for (a) NZ, (b) NZ-Cu1, (c) NZ-Cu2, (d) NZ-Cu3 and (e) NZ-Cu4 samples obtained from Tauc plots.

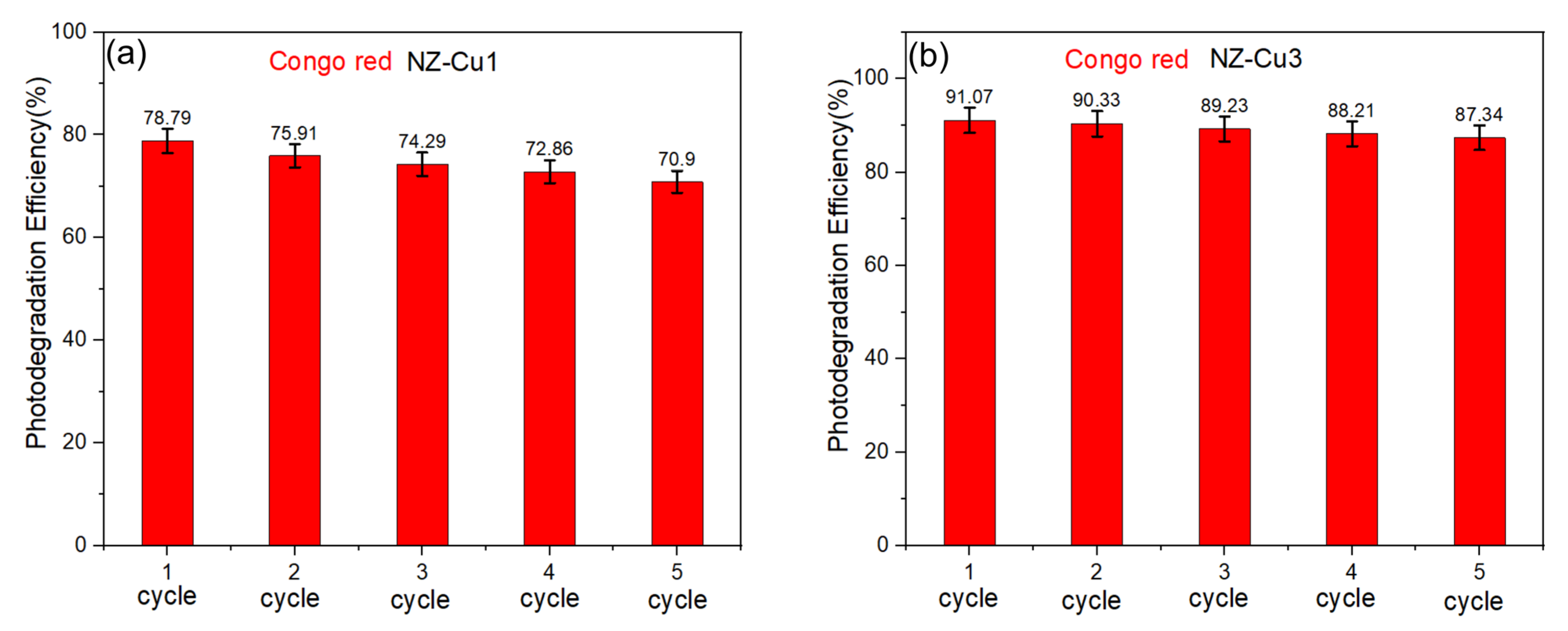

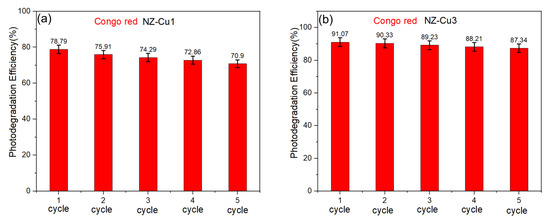

The reusability and stability of the photocatalysts were evaluated through five consecutive photocatalytic degradation cycles using NZ–Cu1 and NZ–Cu3. After each cycle, the catalysts were recovered by filtration, thoroughly washed with distilled water, dried, and thermally treated at 150 °C prior to reuse under identical experimental conditions. As shown in Figure 13, both samples exhibit good stability over repeated cycles. For NZ–Cu1, the degradation efficiency decreases gradually from 78.79% in the first cycle to 70.90% after the fifth cycle, corresponding to a retention of approximately 90% of the initial activity. In contrast, NZ–Cu3 shows superior stability, with the degradation efficiency decreasing only slightly from 91.07% to 87.34% after five cycles, retaining more than 95% of its initial activity. The mild thermal treatment at 150 °C likely contributes to the removal of adsorbed reaction intermediates and partial regeneration of active sites, thereby limiting catalyst deactivation. The remaining minor activity loss can be attributed to slight surface reconstruction of Cu-containing species or gradual changes in surface chemistry during repeated irradiation. Overall, these results demonstrate the good operational stability and reusability of the Cu-modified clinoptilolite photocatalysts.

Figure 13.

Reusability and regeneration potential of (a) NZ-Cu1 and (b) NZ-Cu3 of Congo red.

The photocatalytic performance of the natural zeolite clinoptilolite catalysts developed in this work was evaluated against previously reported materials for Congo red degradation (Table 4). The pristine NZ sample exhibited a relatively low degradation efficiency of 37.5%, comparable to some reported nanostructures such as nanoleaves (48%) and nanosheets (12%). Upon Cu modification, however, the NZ–Cu composites demonstrated markedly enhanced activity. NZ-Cu1 and NZ-Cu2 achieved efficiencies of 78.8% and 85.1%, respectively, outperforming several conventional photocatalysts including mesoporous TiO2 (40%), NiCo2O4/g-C3N4 (65%), and Cu/CuO@C (88.4%). Notably, NZ-Cu3 reached 91.0% degradation, comparable to high-efficiency systems such as 3% Cu-doped TiO2 (91%) and Pani@rGO/CuO (91.7%), and approaching the performance of the best-reported materials, including CuS-Bi2CuxW1−xO6−2x (95%) and Pb0.10Cu0.90Bi2O4 (99.2%). These results clearly demonstrate that Cu incorporation significantly improves the catalytic activity of NZ, placing NZ-Cu composites among the more efficient photocatalysts reported for Congo red degradation.

Table 4.

Comparative degradation efficiencies of various catalysts toward CR.

4. Conclusions

Copper-modified natural clinoptilolite catalysts were successfully synthesized via ion exchange followed by alkalinity-induced precipitation, enabling the controlled tuning of copper speciation on the zeolite surface. Physicochemical characterization confirmed a clear transition from exchanged Cu2+ species at low copper loading to the formation of copper hydroxide and oxide phases at higher alkalinity, while preserving the structural integrity of the clinoptilolite framework. The Cu-modified samples exhibited significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity toward Congo red degradation under UV irradiation compared to pristine clinoptilolite. Among them, the NZ-Cu3 sample demonstrated the best performance, achieving approximately 91% dye degradation within 30–40 min, which is attributed to its favorable combination of copper phase composition, increased surface area and improved pore structure. Kinetic analysis revealed that the degradation process is not adequately described by a pseudo-first-order model, whereas the pseudo-second-order model provides an excellent fit for all samples, indicating that chemisorption governs the rate-limiting step. Radical scavenger experiments further demonstrated that photogenerated holes (h⁺) are the dominant reactive species responsible for dye degradation, while hydroxyl radicals play a secondary role. Diffuse reflectance analysis showed only minor variations in band gap energy upon copper modification, suggesting that the improved photocatalytic performance primarily arises from enhanced surface redox activity and more efficient charge separation rather than significant changes in the electronic band structure. Overall, this study highlights Cu-modified clinoptilolite, particularly NZ-Cu3, as an efficient, low-cost and environmentally friendly photocatalyst with strong potential for wastewater treatment applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and A.N.; methodology, H.L.; validation, H.L., L.T., S.A.-V. and B.B.; formal analysis, L.T., S.A.-V. and B.B.; investigation, H.L., L.T. and A.N.; data curation, H.L., B.B., S.A.-V. and L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, A.N. and L.T.; visualization, H.L., L.T. and A.N.; project administration, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Research equipment of the project № BG16RFPR002-1.014-0006 “National Centre of Excellence Mechatronics and Clean Technologies” was used for experimental work financially supported by European Regional Development Fund under “Research Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation” program 2021–2027.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NZ | Natural clinoptilolite |

| CR | Congo red |

| PFO | Pseudo-first-order |

| PSO | Pseudo-second-order |

| WDXRF | Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray Diffraction Analysis |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

References

- Bai, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, R.; Dong, J.; Yang, H. Enhancement of Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Performance via Generation and Diffusion of ROS. Sci. Energy Environ. 2024, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.-H.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.-H. Recent progress in catalytically driven advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, E.H.; Muslim, S.A.; Saady, N.M.C.; Ali, N.S.; Salih, I.K.; Mohammed, T.J.; Albayati, T.M.; Zendehboudi, S. Recent advances in photocatalytic advanced oxidation processes for organic compound degradation: A review. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Y.; Raj, R.; Ghangrekar, M.; Nema, A.K.; Das, S. Critical assessment of advanced oxidation processes and bio-electrochemical integrated systems for removing emerging contaminants from wastewater. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1912–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.-M. Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Fundamentals and applications to the removal of various types of aqueous pollutants. Catal. Today 1999, 53, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.; Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.-J.; Tan, L.-L.; Ng, Y.H.; Yong, S.-T.; Chai, S.-P. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based photocatalysts for artificial photosynthesis and environmental remediation: Are we a step closer to achieving sustainability? Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7159–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, O.; Vaiano, V.; Sannino, D. Main parameters influencing the design of photocatalytic reactors for wastewater treatment: A mini review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2608–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M.; Nolan, N.T.; Pillai, S.C.; Seery, M.K.; Falaras, P.; Kontos, A.G.; Dunlop, P.S.; Hamilton, J.W.; Byrne, J.A.; O’shea, K. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 125, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, F.; Shen, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Liang, J. Removal of emerging organic pollutants by zeolite mineral (Clinoptilolite) composite photocatalysts in drinking water and watershed water. Catalysts 2024, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Xu, J.; Shen, B. A Mini-Review of Recent Progress in Zeolite-Based Catalysts for Photocatalytic or Photothermal Environmental Pollutant Treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iznaga, I.; Shelyapina, M.G.; Petranovskii, V. Ion exchange in natural clinoptilolite: Aspects related to its structure and applications. Minerals 2022, 12, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzicka, A.; Sulikowski, B.; Ruggiero-Mikołajczyk, M. Catalytic and physicochemical properties of modified natural clinoptilolite. Catal. Today 2016, 259, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifasi, N.; Ziantoni, B.; Fino, D.; Piumetti, M. Fundamental properties and sustainable applications of the natural zeolite clinoptilolite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 27805–27840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.C.; Maneesha, P.; Datta, S.; Dukiya, K.; Sasmal, D.; Samantaray, K.S.; BR, V.K.; Dasgupta, A.; Sen, S. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water using copper oxide (CuO) nanosheets for environmental application. JCIS Open 2024, 13, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpo, M.; Kamat, P.V. Environmentally Benign Photocatalysts: Applications of Titanium Oxide-Based Materials; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva Soriano, G.L. Evaluación de TiO2/Clinoptilona en Suspensión y Película en la Degradación Fotocatalítica de Metilvioleta. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidi, M.; Kondarides, D.I.; Verykios, X.E. Pathways of solar light-induced photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous TiO2 suspensions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2003, 40, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, J.; Rajić, N. Use of natural zeolite clinoptilolite in the preparation of photocatalysts and its role in photocatalytic activity. Minerals 2024, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Kakhki, R.; Zirjanizadeh, S.; Mohammadpoor, M. A review of clinoptilolite, its photocatalytic, chemical activity, structure and properties: In time of artificial intelligence. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 10555–10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtpeyma, G.; Shabanian, S.R. Efficient photocatalytic oxidative desulfurization of liquid petroleum fuels under visible-light irradiation using a novel ternary heterogeneous BiVO4-CuO/modified natural clinoptilolite zeolite. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 445, 115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapawe, N.; Jalil, A.; Triwahyono, S.; Sah, R.; Jusoh, N.; Hairom, N.H.H.; Efendi, J. Electrochemical strategy for grown ZnO nanoparticles deposited onto HY zeolite with enhanced photodecolorization of methylene blue: Effect of the formation of SiOZn bonds. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 456, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.M.; Aroosh, K.; Meng, D.; Ruan, X.; Akhter, M.; Cui, X. A review on modified ZnO to address environmental challenges through photocatalysis: Photodegradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Today Energy 2025, 48, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, J.; Hrenović, J.; Povrenović, D.; Rajić, N. Advances in the applications of Clinoptilolite-Rich Tuffs. Materials 2024, 17, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, S.; Lin, X. New insights on degradation of methylene blue using thermocatalytic reactions catalyzed by low-temperature excitation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, M.; Sharma, M.; Pathania, K.; Jena, P.K.; Bhushan, I. Degradation of synthetic dyes using nanoparticles: A mini-review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 49434–49446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, H.B.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Pourhassan, Z.; Alenezi, F.N.; Silini, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Oszako, T.; Luptakova, L.; Golińska, P.; Belbahri, L. Diversity of synthetic dyes from textile industries, discharge impacts and treatment methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetanova, Y.; Tacheva, E.; Dimowa, L.; Tsvetanova, L.; Nikolov, A. Trace elements in the clinoptilolite tuffs from four Bulgarian deposits, Eastern Rhodopes. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2023, 84, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippens, B.C.; De Boer, J. Studies on pore systems in catalysts: V. t method. J. Catal. 1965, 4, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Terzyk, A.P.; Gauden, P.A.; Solarz, L. Numerical analysis of Horvath–Kawazoe equation. Comput. Chem. 2002, 26, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The determination of pore volume and area distributions in porous substances. I. Computations from nitrogen isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Chang, T.-F.M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Sone, M.; Hsu, Y.-J. Mechanistic insights into photodegradation of organic dyes using heterostructure photocatalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.; Abukhadra, M.R.; Khan, A.A.P.; Jibali, B.M. Removal of Congo red, methylene blue and Cr (VI) ions from water using natural serpentine. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 82, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabalan, R.T. Thermodynamics of ion exchange between clinoptilolite and aqueous solutions of na+ k+ and na+ ca2+. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 4573–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudoh, Y.; Takéuchi, Y. Thermal stability of clinoptilolite: The crystal structure at 350 C. Mineral. J. 1983, 11, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaalddin, A.D. Ammonium and Lead Exchange in Clinoptilolite Zeolite Column. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University (Turkey), Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dimowa, L.; Tzvetanova, Y. Powder XRD study of changes of Cd2+ modified clinoptilolite at different stages of the ion exchange process. Minerals 2021, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmons, W. XVII. On Brochantite and its associations. Mineral. Mag. J. Mineral. Soc. 1881, 4, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimowa, L.; Petrova, N.; Tzvetanova, Y.; Petrov, O.; Piroeva, I. Structural features and thermal behavior of ion-exchanged clinoptilolite from Beli Plast deposit (Bulgaria). Minerals 2022, 12, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabalan, R.T.; Bertetti, F.P. Experimental and modeling study of ion exchange between aqueous solutions and the zeolite mineral clinoptilolite. J. Solut. Chem. 1999, 28, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulos, K.P. The relationship between the thermal behavior of clinoptilolite and its chemical composition. Clays Clay Miner. 2001, 49, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, C.H.; Agee, T.; Ginion, K.; Hofmann, A.; Ewanichak, J.; Schaeffer, C., Jr.; Carroll, M.; Schaeffer, R.; McCaffrey, P. The relative stabilities of the copper hydroxyl sulphates. Mineral. Mag. 2007, 71, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittlau, A.H.; Shi, Q.; Boerio-Goates, J.; Woodfield, B.F.; Majzlan, J. Thermodynamics of the basic copper sulfates antlerite, posnjakite, and brochantite. Geochemistry 2013, 73, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, I.F.; Heuss-Aßbichler, S. Recovery of Different Cu-Phases from Industrial Wastewater. Minerals 2024, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marani, D.; Patterson, J.W.; Anderson, P.R. Alkaline precipitation and aging of Cu(II) in the presence of sulfate. Water Res. 1995, 29, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, W.S.; Nokleberg, W.J.; Kokinos, M. Clinoptilolite and ferrierite from Agoura, California. Am. Mineral. 1969, 54, 887–895. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, M.; Smith, J.V. Brochantite. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 1997, 53, 1369–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.I.; Louer, D. High-resolution powder diffraction studies of copper(II) oxide. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991, 24, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, H.R.; Reller, A.; Schmalle, H.W.; Dubler, E. Structure of copper(II) hydroxide, Cu(OH)2. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 1990, 46, 2279–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; He, Y.; Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, F.; Xie, G.; Sheng, J. Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Bi-Based photocatalysts: Synthetic strategies, surface defects, and reaction mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.A. The solubility of crystalline cupric oxide in aqueous solution from 25 °C to 400 °C. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2017, 114, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, E.B. Investigating the Chemical and Thermal Based Treatment Procedure on the Clinoptilolite to Improve the Physicochemical Properties. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. B Chem. Eng. 2022, 5, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Perraki, T.; Orfanoudaki, A. Mineralogical study of zeolites from Pentalofos area, Thrace, Greece. Appl. Clay Sci. 2004, 25, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revellame, E.D.; Fortela, D.L.; Sharp, W.; Hernandez, R.; Zappi, M.E. Adsorption kinetic modeling using pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws: A review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robati, D. Pseudo-second-order kinetic equations for modeling adsorption systems for removal of lead ions using multi-walled carbon nanotube. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2013, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasineh Khiavi, N.; Katal, R.; Kholghi Eshkalak, S.; Masudy-Panah, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Jiangyong, H. Visible Light Driven Heterojunction Photocatalyst of CuO–Cu2O Thin Films for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, M.; Zava, M.; Grande, T.; Prina, V.; Monticelli, D.; Roncoroni, G.; Rampazzi, L.; Hildebrand, H.; Altomare, M.; Schmuki, P.; et al. Enhanced Photocatalytic Paracetamol Degradation by NiCu-Modified TiO2 Nanotubes: Mechanistic Insights and Performance Evaluation. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, K.; Kaushal, S.; Lal, B.; Joshi, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Singh, P.P. Fabrication of CuO/ZnO heterojunction photocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline and ciprofloxacin under direct sun light. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023, 20, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, S., Jr.; Segundo, I.R.; Freitas, E.; Vasilevskiy, M.; Carneiro, J.; Tavares, C.J. Use and misuse of the Kubelka-Munk function to obtain the band gap energy from diffuse reflectance measurements. Solid State Commun. 2022, 341, 114573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Shah, S.S.; Muhammad, F.; Siddiq, M.; Kiran, L.; Aldossari, S.A.; Mushab, M.S.S.; Sarwar, S. Cu-doped mesoporous TiO2 photocatalyst for efficient degradation of organic dye via visible light photocatalysis. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, Y.P.; Pradhan, S.R.; Behera, C.; Mishra, B. Visible light driven efficient photocatalytic degradation of Congo red dye catalyzed by hierarchical CuS–Bi 2 Cu x W 1− x O 6− 2x nanocomposite system. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 35589–35601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitkari, G.; Chowdhary, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Motghare, A. Potential of Copper-Zinc Oxide nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2022, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadollahkhani, A.; Ibupoto, Z.H.; Elhag, S.; Nur, O.; Willander, M. Photocatalytic properties of different morphologies of CuO for the degradation of Congo red organic dye. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 11311–11317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.-L.; Liu, X.; Luan, J.; Jiao, G.-R.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Yan, F. Preparation, structure and photocatalytic degradation property of a copper-based complex and its derivative material. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 322, 123995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Bibi, I.; Majid, F.; Dahshan, A.; Jilani, K.; Taj, B.; Ghafoor, A.; Nazeer, Z.; Alzahrani, F.M.; Iqbal, M. Cu and Fe doped NiCo2O4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite ferroelectric, magnetic, dielectric and optical properties: Visible light-driven photocatalytic degradation of RhB and CR dyes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haqmal, E.; Pan, J.; Ahmed, A.; Ullah, R.; Khan, J. Synthesis of PbxCu1− xBi2O4 composites with enhanced visible-light-responsive photocatalytic degradation performance. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustgeer, M.R.; Jilani, A.; Ansari, M.O.; Shakoor, M.B.; Ali, S.; Imtiaz, A.; Zakria, H.S.; Othman, M.H.D. Reduced graphene oxide supported polyaniline/copper (II) oxide nanostructures for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of Congo red and hydrogen production from water. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurenko, J.; Sijo, A.; Kaykan, L.; Kotsyubynsky, V.; Gondek, Ł.; Zywczak, A.; Marzec, M.; Vyshnevskyi, O. Synthesis and Characterization of Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. J. Nanotechnol. 2025, 2025, 8899491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, S. Hydrothermal synthesis, growth mechanism, optical properties and photocatalytic activity of cubic SrTiO3 particles for the degradation of cationic and anionic dyes. Optik 2018, 175, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Sabahat, S.; Aftab, M.; Sun, J.; Shah, N.S.; Rahim, A.; Abdullah, M.M.; Imran, M. Synergistic degradation of toxic azo dyes using Mn-CuO@ Biochar: An efficient adsorptive and photocatalytic approach for wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 302, 120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, P.; Boruah, P.K.; Darabdhara, G.; Sengupta, P.; Das, M.R.; Boronin, A.I.; Kibis, L.S.; Kozlova, M.N.; Fedorov, V.E. Microwave assisted synthesis of CuS-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite with efficient photocatalytic activity towards azo dye degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4600–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.