Abstract

Based on hot-compression simulations combined with SEM and TEM analyses, the high-temperature deformation behavior and mechanisms of a new nickel-based powder superalloy FGH101 were investigated over 1020–1110 °C and strain rates of 0.001–0.05 s−1. From the experimental data, the variations in the strain-rate sensitivity index m, the apparent activation energy for hot deformation Q, and the grain-size exponent p were determined as functions of strain rate and temperature. Hot deformation processing maps and mechanism maps incorporating dislocation density were established. The processing maps clearly revealed the evolution of formable regions at different temperatures and strains, while the mechanism maps successfully predicted the dislocation evolution and its operative hot deformation mechanisms by introducing the grain size evolution corrected by Burgers-vector compensation and the rheological flow stress behavior compensated by the modulus. The results indicated an optimal processing window of 1060–1100 °C at 0.001–0.003 s−1. Within the tested regime, as the strain rate decreased, the operative mechanism for grain-boundary sliding transitioned from pipe-diffusion control to lattice-diffusion control. These findings provide a solid theoretical basis for the design and optimization of the isothermal forging process of the new FGH101 alloy.

1. Introduction

Nickel-based powder metallurgy superalloys, characterized by the absence of macroscopic segregation and excellent hot workability, attract attention in aerospace applications, particularly for components of high-performance engines’ hot sections [1,2]. Over the past five decades, the powder metallurgy superalloys have been classified into four categories based on their performance characteristics by the United States and Europe. The high-strength type, exemplified by the U.S. alloy René 95, is characterized by a relatively high γ′ phase content (typically more than 45%), sub-solvus heat treatment below the γ′ solvus temperature, fine grain size, and high tensile strength, with a service temperature of approximately 650 °C. The damage-tolerant type, represented by the U.S. René 88 DT and French N18 alloys, undergoes super-solvus heat treatment above the γ′ solvus temperature, producing coarser grains and lower tensile strength but improved creep resistance, crack growth resistance, and overall damage tolerance, with a service temperature of around 700 °C. The high-strength and highly damage-tolerant type, represented by alloys such as U.S. René 104 and Alloy 10, the U.K. RR1000, and the French N19, typically contains 45–50% γ′ phase. These alloys exhibit both high tensile strength and low crack growth rates, with a service temperature of approximately 750 °C. Europe and the United States have focused on developing new generations of powder metallurgy superalloys capable of operating at temperatures up to 815 °C in the 21st century, which offer improved strength, enhanced damage tolerance, and higher operating temperatures. Publicly reported alloys of this class include the U.S. high-Ta ME5 series [3], high-Ta alloys strengthened by γ′ + η phase synergy [4], and high-W and high-Ta TSNA-1 alloys [5,6]; the U.K. high-Co and high-Ta alloys [7]; high-Ta cost-reduced alloys [8]; and high-Nb RRHT series alloys [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The alloy investigated in the present study, designated FGH101, is a new powder metallurgy superalloy independently developed by the AECC Beijing Institute of Aeronautical Materials and designed for service at above 750 °C.

At present, the manufacturing of turbine disks primarily employs isothermal forging and powder metallurgy techniques. During forging, the hot workability of the material is critical [17]. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted on the hot deformation behavior and mechanisms of nickel-based superalloys. Kumar [18] proposed a revised constitutive model for peak stress under hot deformation. Mccarley [19] elucidated the effect of stacking fault energy on microstructural evolution during hot deformation. Kumar et al. [20] investigated the flow behavior of a Ni–25Cr–14W superalloy. Based on processing map analysis, they identified a stable hot working domain within the temperature range of 1000–1200 °C and strain rates of 0.001–0.1 s−1, with the maximum power-dissipation efficiency occurring at 1175 °C under a strain rate of 0.001 s−1. Zhou [21] characterized the hot deformation behavior of GH79, employed hot processing maps to identify optimal forming windows and flow instability regions, and further constructed an R-W-S-type deformation mechanism map. Given the high alloying levels, high γ′ volume fraction, and narrow hot workability window of new P/M superalloys, an in-depth investigation of their hot deformation behavior is imperative. Previous studies have successfully developed RWS deformation mechanism maps incorporating dislocation density for magnesium alloys, nickel-based superalloys, and NiTi alloys [22,23]. If the dislocation density within grains during the hot deformation of the FGH101 alloy could be integrated into the RWS deformation mechanism map to construct a comprehensive map that includes dislocation density, it would not only enable precise prediction of the alloy’s hot deformation mechanisms but also allow quantitative forecasting of dislocation evolution during hot deformation. This approach holds significant guiding value for in-depth research on the deformation mechanisms of powder metallurgy superalloys.

Therefore, this study focuses on FGH101, a new nickel-based powder superalloy. Hot compression simulations were conducted using a Gleeble-3500 thermomechanical simulator within a temperature range of 1020–1110 °C and strain rates of 0.001–0.05 s−1. The high-temperature deformation behavior and mechanisms of the FGH101 alloy were investigated. Based on the results, processing maps and deformation mechanism maps incorporating dislocation density were developed for the alloy’s hot deformation process. This research provides theoretical support for the design and optimization of isothermal forging processes for this alloy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The experimental material employed in this paper was FGH101, a new nickel-based powder metallurgy superalloy developed by the AECC Beijing Institute of Aeronautical Materials. This alloy is designed for service at temperatures above 750 °C. Its chemical composition is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of FGH101 alloy (mass fraction/%).

2.2. Methods

Cylindrical specimens (10 mm diameter, 15 mm height) were machined from the FGH101 alloy by wire electrical discharge machining for hot compression testing.

The testing equipment is the Gleeble-3500 produced by DSI Company in Albany, NY, USA, with the following key parameters: a maximum heating rate of 10,000 °C/s; a temperature control accuracy of ±1 °C; a maximum static tensile/compressive load of 100 kN, with a force measurement accuracy of 10 N; maximum and minimum axial movement speeds of 1000 mm/s and 0.001 mm/s, respectively; and a displacement measurement accuracy of 0.002 mm. The test was conducted in accordance with ASTM E9-19 [24], “Standard Test Methods of Compression Testing of Metallic Materials at Room Temperature.” Test conditions are summarized in Table 2, with the testing environment being a vacuum. Two thermocouples were welded 1 mm apart on the lateral surface of the specimen to enable real-time temperature control via connection to the testing machine. The specimen, with attached leads, was mounted in the specimen holder. The height and extension of the holder were adjusted to ensure the specimen was centered within the anvils during clamping. To minimize the influence of friction at the punch ends during high-temperature compression and to prevent non-uniform deformation phenomena such as barreling or tilting, graphite lubricant was applied to the specimen ends, which were also fitted with tantalum spacers. The specimen was heated to the preset deformation temperature at a rate of 10 °C/s and held for 5 min to ensure uniform heating, followed by compression at the corresponding strain rate. Immediately after compression, the specimen was water-quenched to preserve the complete high-temperature microstructure. To ensure statistical reliability of the experimental data, three valid repeat tests were conducted for each thermomechanical compression condition. The flow stress curves and related data presented in the paper represent the average values from these three repeated tests, with a standard deviation of less than 5% of the mean. The measurement uncertainty of the experimental results primarily originates from temperature control accuracy (±1 °C), load measurement accuracy (±1.0%), and strain measurement accuracy (±0.5%). All measuring instruments were rigorously calibrated prior to testing to ensure scientific validity of the data.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters of hot simulation compression.

High magnification microstructural observations were conducted using a TESCAN MIRA 3 XMU field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM), manufactured by TESCAN in Brno, Czech Republic. In order to prepare high-magnification metallographic samples, the deformed FGH101 alloy specimens were immersed in a corrosive solution of 15% sulfuric acid and potassium permanganate and boiled for 8 min. Meanwhile, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) specimens of the deformed alloy were prepared by using the TenuPol-5 twin-jet electropolisher while experimental parameters were set as a current of 40–45 mA, a voltage of 60 V, and a temperature range of −40 to −35 °C. The equipment was manufactured by Struers in Copenhagen, Denmark. Microstructure characterization was carried out using a JEM-200CX electron microscope (manufactured by JEOL in Tokyo, Japan) operating at 200 kV.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Characteristics of Hot Deformation Behavior of FGH101 Alloy

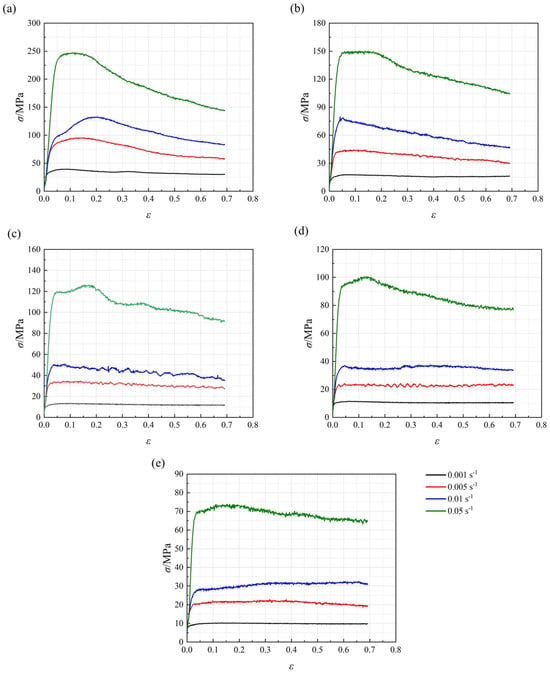

The true stress–strain curves obtained from hot compression simulation tests on the FGH101 alloy are presented in Figure 1. Overall, the evolution of flow stress with increasing strain exhibited a consistent trend across different deformation conditions. At the onset of deformation, the flow stress rose sharply with strain, reaching a distinct peak. After reaching the peak stress, the flow stress continues to decrease or remains steady with increasing deformation. Additionally, the curves demonstrate that flow stress decreased with decreasing strain rate and rising deformation temperature.

Figure 1.

True stress–strain curves of FGH101 alloy under different deformation conditions: (a) 1020 °C, (b) 1050 °C, (c) 1070 °C, (d) 1090 °C, (e) 1110 °C.

Under intermediate strain rate conditions, the curve exhibits a typical dynamic recrystallization (DRX) feature [25]: the flow stress declined and gradually approached a steady state after reaching the peak stress. This behavior was governed initially by work hardening, during which dislocations in the FGH101 alloy multiplied and moved extensively under applied strain. As strain accumulated, dynamic softening became increasingly significant, reducing the contribution of work hardening and slowing the rate of stress increase until the peak was reached. Beyond the peak, dynamic softening mechanisms, dominated by dynamic recrystallization, replaced work hardening as the prevailing process, causing the flow stress to decrease toward a steady state. With higher deformation temperatures, the transition to steady state occurred more rapidly, and the magnitude of stress drop was reduced. This could be attributed to the fact that 0.05 s−1 was located at the transition region between low and high strain rate, where the deformation mechanism reflected concurrent contributions from grain boundary sliding, dislocation slip, and DRX. The resulting curve characteristics thus represented a superposition of superplastic deformation and dynamic softening. As temperature increased, the relative contribution of grain boundary sliding became more pronounced, imparting more distinct superplastic features to the flow stress curves.

Under low strain rates and deformation temperatures of 1020 °C or 1050 °C, only the curve at 0.001 s−1 achieved a steady flow regime after the peak stress. In contrast, the curves corresponding to 0.005 s−1 and 0.01 s−1 continued to decline after reaching the peak stress. However, when the temperature reached 1070 °C, all strain rate curves exhibited steady state flow after the peak and showed clear superplastic deformation characteristics. This phenomenon was caused by grain boundary sliding initiated preferentially along boundaries in favorable orientations at the onset of deformation. Since grain shapes did not perfectly accommodate sliding, stress concentrations developed at triple junctions and similar sites. In the early stage, the stress was insufficient to fully activate the atomic diffusion and dislocation motion required to relieve these concentrations, resulting in a “hardening” response—i.e., deformation required steadily increasing stress. Once the peak stress was attained, the rates of grain boundary sliding and accommodation processes reached equilibrium, and the material entered steady state flow. As temperature increased, diffusion creep and dislocation slip were fully activated, enhancing the capacity to accommodate grain boundary sliding. This reduced the peak stress necessary to achieve coordination between sliding and diffusion, thereby allowing curves at higher strain rates to display superplastic behavior.

3.2. Strain Rate Sensitivity Index of FGH101 Alloy

The fundamental characteristic of the thermal deformation process in metallic materials adheres to the Backofen equation [26], expressed as

where is the flow stress during the thermal deformation process of the metallic material, is the strain rate, K is a constant determined by the material’s properties, and m is the strain rate sensitivity index. After mathematical transformation of Equation (1), could be obtained, indicating that the m-value corresponded to the slope of the lgσ-lg curve, specifically

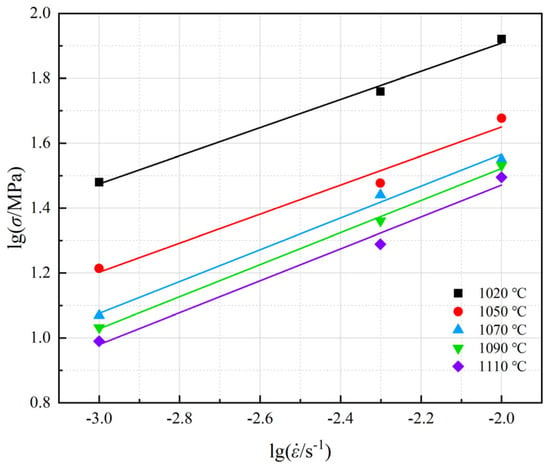

During hot deformation, the flow stress of the FGH101 alloy depended strongly on strain rate, indicating pronounced strain rate sensitivity. Accordingly, the strain rate sensitivity exponent m is a key parameter for assessing the hot formability of the alloy. Figure 2 presents the flow stress–strain rate relationships at a true strain of 0.6 under low strain rate conditions for deformation temperatures of 1020, 1050, 1070, 1090, and 1110 °C. As specified by Equation (2), the slopes of the linear fits in Figure 1 yield the strain rate sensitivity exponent m; the corresponding values are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

lgσ-lg curves of FGH101 alloy.

Table 3.

Strain rate sensitivity (m) of FGH101 alloy at different temperatures (ε = 0.69).

Table 3 shows that the m values of the FGH101 alloy were consistently greater than 0.3, suggesting that the alloy exhibited excellent superplasticity under high temperature and low strain rate. The m value increased with deformation temperature, reaching a maximum of 0.494 at 1090 °C. However, the m value decreased relative to that at 1090 °C at 1110 °C. This reduction was attributed to microstructural evolution induced by energy variations during hot deformation.

3.3. Activation Energy for Thermal Deformation of FGH101

The hot deformation of FGH101 alloy is a thermally activated process based on energy dissipation and redistribution. T.G. Langdon [27] proposed that individual deformation mechanisms exhibit strain rates governed by a general relationship dependent on stress, temperature, and grain size, expressed in the following form:

In the equation, represents the strain rate; A is a dimensionless constant; D denotes the diffusion coefficient, expressed as D0exp(−Q/RT), where D0 is a frequency factor; Q is the deformation activation energy; R stands for the ideal gas constant; G signifies the shear modulus; b is the Burgers vector; k refers to the Boltzmann constant; T indicates the deformation temperature; d represents the grain size; p is the grain size exponent; σ corresponds to the flow stress; and n denotes the stress exponent. Assuming constant grain size and strain rate, a mathematical transformation of Equation (3) yields the apparent activation energy at constant strain rate, as shown in Equation (4):

Figure 3 displays the lgσ − 1/T curve for FGH101 alloy under low strain rates during hot deformation. Table 4 presents the slopes of the fitted lines under different strain rates and their 95% confidence intervals. The slopes were deemed statistically significant as their confidence intervals did not include zero. By combining the slope of the curve with the m value calculated in Section 3.2, the thermal deformation activation energy Q value for the alloy at a strain of 0.69 could be determined, as shown in Table 5.

Figure 3.

lgσ − 1/T curves of FGH101 alloy.

Table 4.

Fitted slopes and confidence intervals of lgσ−1/T curves.

Table 5.

Values of activation energies Q during hot deformation (ε = 0.69) of FGH101 alloy (KJ/mol).

As shown in Table 5, the thermal deformation activation energy (Q) of the alloy ranged from 439.53 to 580.07 KJ/mol. With increasing deformation temperature, Q initially increased and then stabilized, reaching a maximum at 1090 °C. Ma [28] demonstrated that, at a constant strain rate, higher deformation temperatures promoted dynamic recovery and recrystallization, which facilitated the annihilation of dislocations accumulated at grain boundaries and the nucleation of new strain-free recrystallized grains. As a result, the average intragranular misorientation decreased, thereby alleviating stress concentration. The dynamic recrystallization mechanism observed in the FGH101 alloy in this paper was consistent with these findings. Under high temperature and low strain rate, both grain boundary diffusion and lattice diffusion contributed to deformation mechanisms, and grain boundary diffusion was dominant; consequently, the apparent activation energy approached the value corresponding to grain boundary diffusion. At higher deformation temperatures, lattice diffusion became increasingly significant, causing the apparent activation energy to approach that of lattice diffusion. This transition explained the observed increase in activation energy with temperature.

3.4. Microstructural Evolution During Hot Deformation of FGH101 Alloy

The microstructural evolution of metallic materials during hot deformation plays a crucial role in determining their hot forming performance. The average grain size was measured using the linear intercept method based on the ASTM E112-24 standard [29]. Grain boundary intersections were counted with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software following standardized rules: a clear intersection between a test line and a grain boundary was counted as one intersection; tangency to a grain boundary was counted as a 0.5 intersection; and a test line endpoint terminating on a grain boundary was counted as a 0.5 intersection. The grain size was calculated using Formula (5):

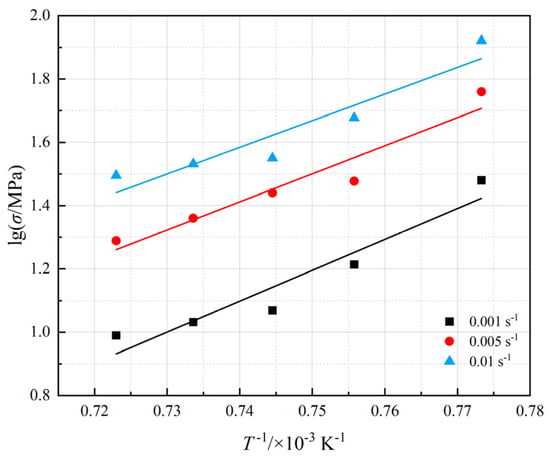

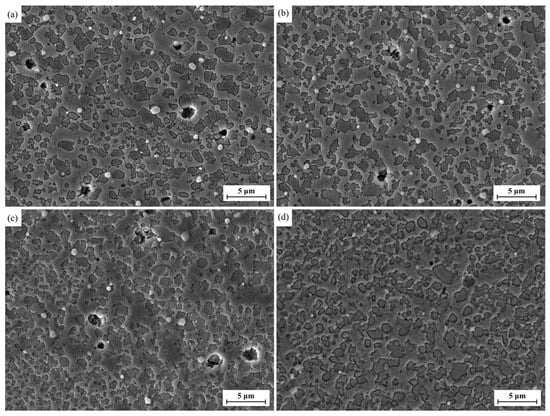

Herein, d represents the average grain size, while denotes the mean intercept length of the metallographic microstructure. Figure 4 showed the metallographic images of the alloy after deformation at 1070 °C and strain rates of 0.001 s1, 0.005 s−1, 0.01 s−1, and 0.05 s−1. The grain sizes calculated using Equation (5) and the data from Figure 4 were 3.69 μm, 2.99 μm, 2.78 μm, and 2.01 μm, respectively. The measurement uncertainty originated mainly from the inherent statistical distribution of grain sizes and statistical fluctuations in intercept counting; the standard deviation for each result was less than 0.4 μm.

Figure 4.

SEM images of FGH101 alloy deformed at 1070 °C and different strain rates (ε = 0.69): (a) 0.001 s−1, (b) 0.005 s−1, (c) 0.01 s−1, (d) 0.05 s−1.

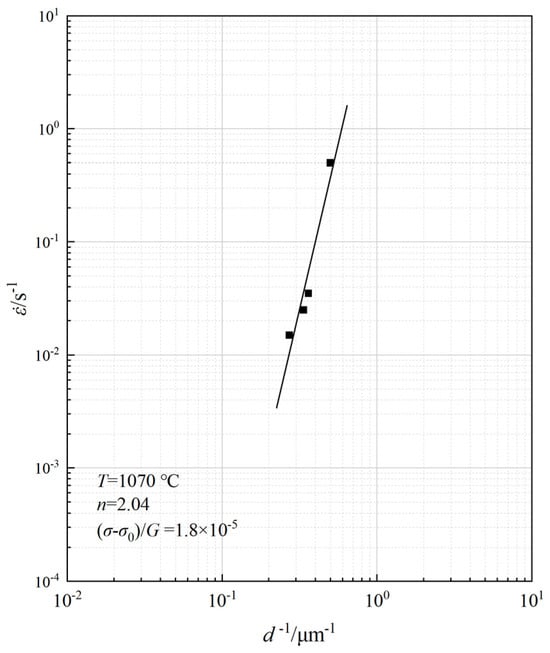

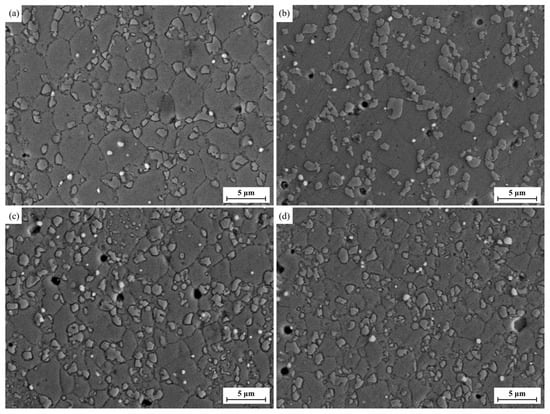

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between strain rate and grain size of the alloy at a deformation temperature of 1070 °C. According to the high-temperature deformation constitutive equation (Equation (3)), the slope of the linear fit corresponded to the grain size exponent, p, which characterized the influence of grain size on the hot workability of alloys. At 1070 °C, the grain size exponent was determined to be 2.25. The grain sizes of the alloy under various deformation conditions were determined from microstructural images obtained at other deformation temperatures by the same procedure, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Accordingly, the corresponding p-values of the alloy at different temperatures were determined, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 5.

Strain rate as a function of average grain size in FGH101 alloy.

Figure 6.

SEM images of FGH101 alloy deformed at 1020 °C and different strain rates (ε = 0.69): (a) 0.001 s−1, (b) 0.005 s−1, (c) 0.01 s−1, (d) 0.05 s−1.

Figure 7.

SEM images of FGH101 alloy deformed at 1110 °C and different strain rates (ε = 0.69): (a) 0.001 s−1, (b) 0.005 s−1, (c) 0.01 s−1, (d) 0.05 s−1.

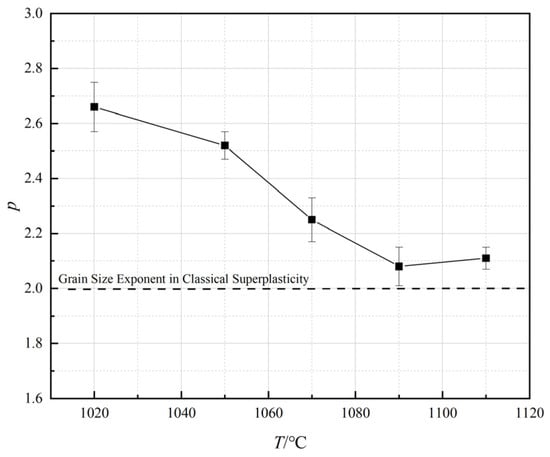

Figure 8.

p-T curve of FGH101 alloy.

As shown in Figure 8, the temperature dependence of the grain size exponent followed a trend similar to that of the stress exponent. As established in Reference [30], a p-value exceeding 2 signified that the metal had a fine, uniform grain structure devoid of abnormal grain coarsening. This condition allowed grain boundary sliding and diffusion creep—two mechanisms that greatly enhanced ductility—to become the dominant deformation modes at high temperatures. Additionally, the microstructural homogeneity acted against deformation incompatibility from large grain size differences, thus mitigating localized stress concentration. Moreover, under high-temperature deformation, grain boundary sliding was accommodated by the combined effects of grain boundary diffusion and lattice diffusion.

3.5. Processing Map of FGH101 Alloy

To prevent internal defects during the hot working of alloys, it is essential to activate dynamic softening mechanisms and avoid flow instability during hot deformation. Based on energy dissipation theory, Prasad [31] et al. developed hot processing maps by superimposing flow instability maps onto power dissipation efficiency maps. In this approach, the systemic energy (P) during the hot deformation of metallic materials is divided into the dissipative component (G) and the dissipative co-component (J), with their mathematical definitions given by Equation (6):

Using theoretical derivation and mathematical transformation, a dimensionless parameter termed the dissipation factor η was developed to characterize the energy dissipation and redistribution in materials during thermal deformation. This factor was formulated as the ratio of the J-integral value to that of an ideal linear dissipator, given in Equation (7). A contour map that plotted the variation in η against deformation temperature and strain rate then formed the power dissipation efficiency diagram.

To assess the thermal deformation performance of metallic materials, Prasad et al. proposed a criterion for rheological instability in the thermal deformation process of metals based on the principle of maximum entropy production, as shown in Equation (8):

In the hot processing map, regions where is less than 0 indicate the occurrence of flow instability in metals. However, the dissipation factor η calculated by Equation (7) is only valid when the flow stress adheres to a power-law relationship. To extend the analysis to metallic flow behaviors that deviate from such functional regularity, Murty [32] et al. derived an instability criterion applicable to any flow stress pattern, as expressed in Equation (9):

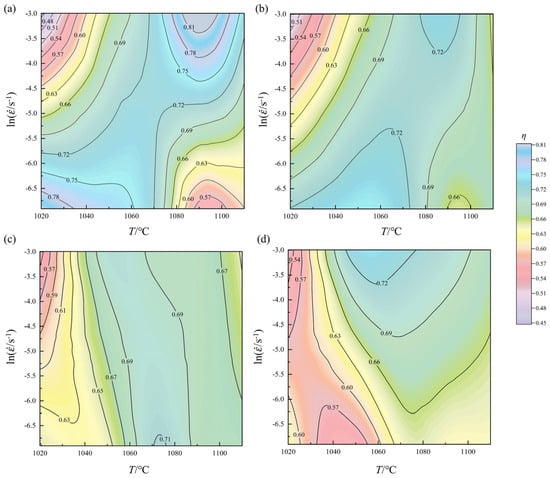

Consequently, processing maps of the FGH101 alloy during hot deformation were constructed based on different instability criteria (Figure 9). In these maps, the variation in the dissipation factor η was shown as contour curves, with shaded areas marking rheological instability zones. According to computational results that incorporated the established instability criteria, the thermal processing map under the chosen deformation conditions showed no evidence of rheological instability.

Figure 9.

Processing maps of the FGH101 alloy under different strains: (a) ε = 0.2, (b) ε = 0.4, (c) ε = 0.55, (d) ε = 0.69.

Analysis of the hot processing maps revealed that the dissipation efficiency factor (η) of FGH101 alloy during high-temperature deformation ranged from 0.45 to 0.81. The peak energy dissipation rates occurred predominantly in regions of low and high strain rates. With increasing strain, the maximum η value decreased from 0.83 to 0.74, while the minimum value increased from 0.44 to 0.52. Regions with η < 0.6 extended from low-temperature/high-strain-rate zones toward high-temperature/low-strain-rate zones, whereas areas with η > 0.7 diminished progressively. For nickel-based superalloys, deformation in low-η regions tended to induce defects such as adiabatic shear bands, voids, and microcracks. Conversely, high energy dissipation rates indicated superior workability. The existing literature suggested that regions with η > 0.3 were generally suitable for hot processing [33]. Thus, within the studied processing window, FGH101 alloy exhibited favorable hot workability. At a strain of 0.2, high energy dissipation zones spanned primarily from 1020–1060 °C/0.001–0.0015 s−1 to 1070–1110 °C/0.015–0.05 s−1. At ε = 0.4, these zones shifted to 1040–1070 °C/0.001–0.0025 s−1 and 1080–1100 °C/0.025–0.05 s−1. When ε = 0.55, the high-η region expanded to 1050–1100 °C/0.001–0.05 s−1, and at ε = 0.69, it narrowed further to 1060–1110 °C/0.003–0.05 s−1. High-strain regions imposed stringent demands on equipment capabilities, temperature accuracy, and strain rate control. Excessively high strain rates could trigger deformation instability. Therefore, the optimal processing parameters for FGH101 alloy were determined to be 1060–1100 °C with strain rates of 0.001–0.003 s−1.

3.6. Deformation Mechanism Map of FGH101 Alloy Incorporating Dislocation Quantities

Based on the deformation mechanism map of R-W-S, the dislocation model is incorporated through constitutive equations to establish a deformation mechanism map that integrates variables such as dislocation density, grain size, strain rate, and flow stress [34].

3.6.1. Construction of the Deformation Mechanism Map

During the hot deformation process of metallic materials, the rate controlling deformation mechanism can be described by the following form as a constitutive equation [35]:

In the equation, εi represents the steady state creep mechanism; Ai, n, p are material constants, whose values vary according to different mechanisms; σ is the creep stress; G is the shear modulus, which can be converted from the Young’s modulus E; di is the grain size; b is the Burgers vector; and D is the diffusion coefficient, mainly including lattice diffusion coefficient DL, dislocation pipe diffusion coefficient DP, and grain boundary diffusion coefficient Dgb [36]. When constructing the constitutive model for deformation mechanism diagrams, Dgb and DP are numerically equivalent [34].

The equation for calculating the number of dislocation lines per unit area within a single grain is [37]

In the equation, ni is the density of dislocations within the grain, v is Poisson’s ratio, τi is stress (MPa), and τi = 0.5σi. The compression test data of the alloy at 1020 °C, 1070 °C, and 1110 °C were substituted into Equation (10) to solve the constitutive equation. Subsequently, the vertex coordinate data from different regions of the obtained mechanism map were substituted into Equation (11) to calculate the dislocation density. The R-W-S deformation mechanism map was then plotted with the stress compensated by the E modulus as the horizontal axis and the grain size compensated by the Burgers vector as the vertical axis, incorporating dislocation quantities. The necessary physical parameters for the calculation process are shown in Table 6 [36].

Table 6.

Physical parameters of nickel-based superalloys.

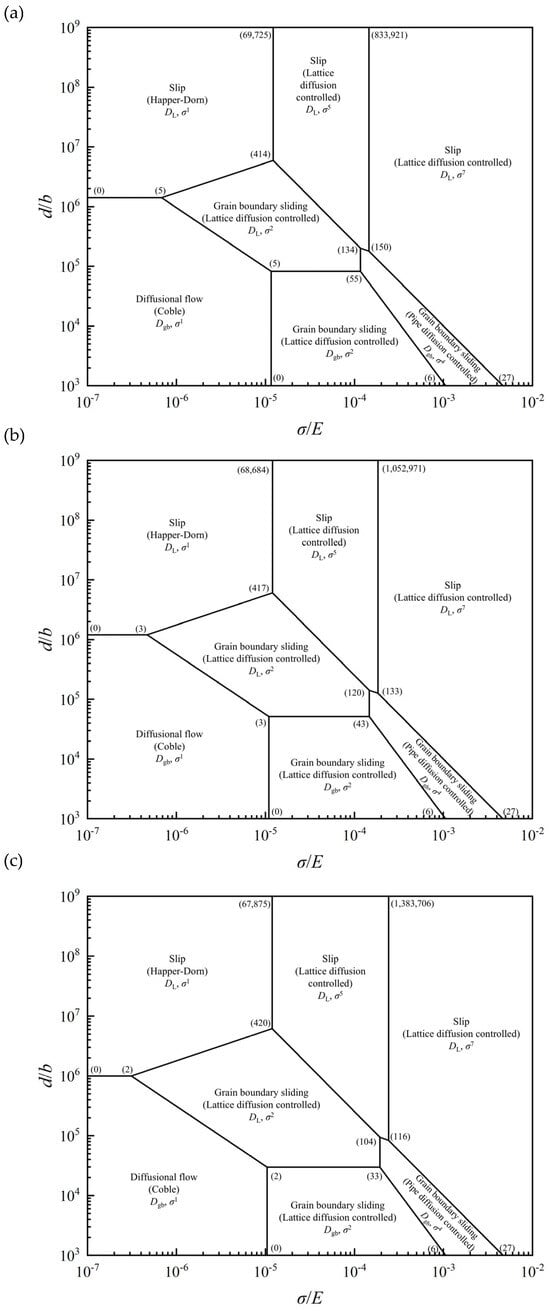

3.6.2. Application of the Deformation Mechanism Map

Figure 10 shows the R-W-S deformation mechanism map incorporating dislocation quantities at 1020, 1070, and 1110 °C. As shown, the deformation mechanisms could be categorized into three primary types: diffusional flow, grain boundary sliding, and slip. The deformation mechanism map was divided into seven distinct regions based on the stress exponent n, with each region representing a specific mechanism defined by its corresponding stress exponent value. The boundaries between adjacent regions were determined by simultaneously solving the constitutive equations of the two corresponding mechanisms. Additionally, the number of dislocations present at the vertices of the deformation mechanism regions was indicated in the map. Calculations of the normalized grain size (d/b) compensated by the Burgers vector and the normalized flow stress (σ/E) compensated by the E modulus for FGH101 alloy at the aforementioned deformation temperatures are shown in Table 7.

Figure 10.

Deformation mechanism maps for FGH101 alloy under different temperatures: (a) 1020 °C, (b) 1070 °C, (c) 1110 °C.

Table 7.

Calculated results for hot compression deformation of FGH101 alloy.

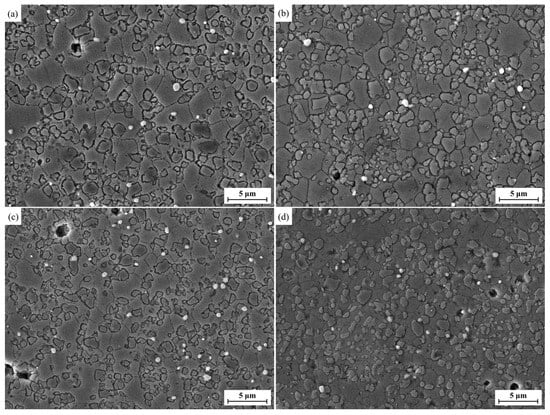

Based on Figure 10a and Table 7, at 1020 °C, the FGH101 alloy lay within the grain boundary sliding region governed by pipe diffusion, characterized by a stress exponent of 4 and occurring under higher strain rates. The corresponding dislocation numbers at the vertices of region were (150), (134), (55), (27), and (6). As the strain rate decreased, the dominant mechanism transitioned to grain boundary sliding controlled by lattice diffusion, with a stress exponent of 2; the dislocation numbers at the vertices of this region were (55), (6), (5), and (0).

At 1070 °C (Figure 10b, Table 7), the FGH101 alloy under higher strain rates also lay within the pipe-diffusion-controlled grain boundary sliding region with a stress exponent of 4. The dislocation numbers at the vertices were (133), (120), (43), (27), and (6). With decreasing strain rate, the mechanism shifted to the lattice-diffusion-controlled grain boundary sliding region with a stress exponent of 2, where the vertex dislocation numbers were (43), (6), (3), and (0).

At 1110 °C (Figure 10c, Table 7), the alloy remained in the grain boundary sliding region governed by pipe diffusion under higher strain rates, exhibiting a stress exponent of 4. The dislocation numbers corresponding to the vertices were (116), (104), (33), (27), and (6). As the strain rate further reduced, the dominant mechanism transformed to grain boundary sliding controlled by lattice diffusion, characterized by a stress exponent of 2, with vertex dislocation numbers of (33), (6), (2), and (0).

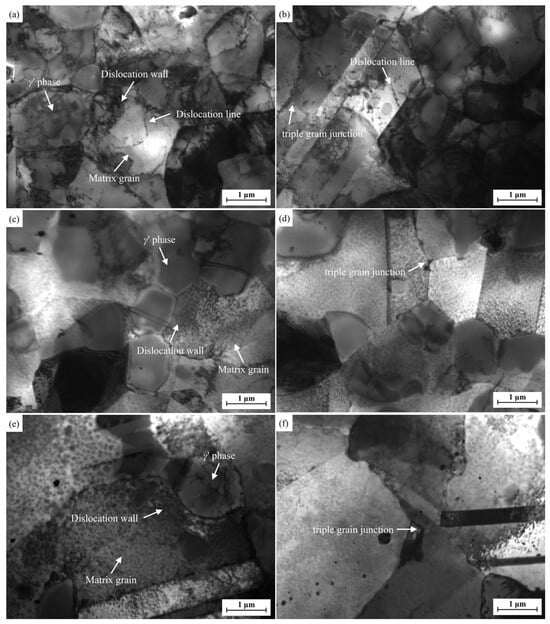

Figure 11 shows TEM micrographs of grain boundary γ′ precipitates and triple junctions in the FGH101 alloy deformed at various temperatures under a strain rate of 0.001 s−1. As shown in the figure, dislocations primarily accumulated at the interfaces between the matrix grains and γ’ phases, as well as at triple junctions, while distinct dislocation lines pinned by intragranular precipitates were observed within the grains. At a deformation temperature of 1020 °C, significant dislocation pile-ups formed dislocation walls at the grain boundary γ’ phases; moderate dislocation tanglings occurred at triple junctions; only sparse dislocation lines were visible elsewhere. Under 1070 °C deformation, although dislocation walls persisted at grain boundary γ’ phases, almost no dislocation pile-ups were observed at triple junctions, and the number of distinct dislocation lines pinned by intragranular precipitates decreased substantially. This trend became more pronounced at 1110 °C, where clear dislocations were nearly absent in all regions of the matrix grains except at the grain boundary γ’ phases.

Figure 11.

Transmission electron microscopy images of FGH101 alloy under a strain rate of 0.001 s−1 at different deformation temperatures: (a) 1020 °C, grain boundary γ’ phase; (b) 1020 °C, triple grain junction; (c) 1070 °C, grain boundary γ’ phase; (d) 1070 °C, triple grain junction; (e) 1110 °C, grain boundary γ’ phase; (f) 1110 °C, triple grain junction.

These observations, together with the preceding analysis, indicated that hot deformation in FGH101 was governed by superplastic grain boundary sliding accommodated by grain boundary diffusion and dislocation pipe diffusion. According to the Ball–Hutchison model, obstacles at the leading edge of a sliding boundary cause stress concentrations that activate dislocation sources in adjacent grains. In FGH101, stress concentrations arose along the sliding path; dislocation activity was required to relax these stresses and enable smooth boundary motion. The stress concentration was more pronounced at grain boundary γ′ precipitates than at triple junctions, leading to substantial dislocation pile-ups near the γ′ at boundaries. With further increases in temperature, the overall dislocation density continued to decline, as evidenced by the progressive reduction in both intragranular dislocation lines and entangled dislocations at triple junctions. At 1110 °C, clearly defined dislocation lines pinned by intragranular precipitates were scarcely observable, consistent with the deformation mechanism maps for FGH101.

4. Conclusions

In the present research, the deformation behavior and mechanisms of the new nickel-based powder superalloy FGH101 during hot deformation were systematically investigated through hot compression tests. The findings provide critical theoretical guidance for the subsequent development and process optimization of this alloy. The principal conclusions are drawn as follows:

(1) The key constitutive parameters for the FGH101 alloy during hot deformation were quantified. Within the temperature range of 1020–1110 °C and strain rates between 0.001 s−1 and 0.01 s−1, the strain rate sensitivity index m varies from 0.434 to 0.494. The corresponding activation energy Q lies between 439.53 and 580.07 KJ/mol, while the grain size exponent p ranges from 2.08 to 2.66. It is noteworthy that at 1090 °C, both the m and Q values reach their maxima, whereas p reaches its minimum.

(2) The dynamic DMM thermal processing analysis of FGH101 alloy revealed that its optimal processing window lay within the temperature range of 1060–1100 °C and strain rate range of 0.001–0.003 s−1. With increasing deformation, the maximum value of the dissipation factor η during high-temperature deformation decreased from 0.83 to 0.74, while its minimum value increased from 0.44 to 0.52. The region with η values below 0.6 expanded from the low-temperature and high-strain-rate zone toward the high-temperature and low-strain-rate zone. Concurrently, the area where η exceeded 0.7 progressively diminished.

(3) R-W-S deformation mechanism maps incorporating dislocation density were successfully established. The maps clearly elucidated the intrinsic correlation between dislocation population and grain size under modulus-compensated stress as well as Burgers-vector compensation. Simultaneously, it was confirmed that across the tested temperature range (1020–1110 °C), the operative deformation mechanism was observed to transition from pipe-diffusion-controlled to lattice-diffusion-controlled grain boundary sliding as the strain rate was reduced from 0.05 s−1 to 0.001 s−1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; methodology, Y.L. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, Y.L. and X.M.; investigation, J.Y., X.W., Y.Z., K.Z. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., W.X. and Y.Y.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the Advanced Materials-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0600300).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of the National Science and Technology Major Project.

Conflicts of Interest

Jie Yang, Yaliang Zhu, and Xiaofeng Wang were employed by the AECC Beijing Institute of Aeronautical Materials. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.H.; Zhang, B.Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Wang, X.X.; Sun, J.S. Modeling and simulation of grain growth for FGH96 superalloy using a developed cellular automaton model. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 32, 055011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Zhang, B.Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Wang, X.X.; Feng, Y.K.; Su, L.D.; Liang, Z.F.; Liu, Y.F. Using a Combined FE-CA Approach to Investigate Abnormally Large Grains Formed by the Limited Recrystallization Mechanism in a Powder Metallurgy Nickel-Based Superalloy. Crystals. 2025, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Bain, K.; Wessman, A.; Wei, D.; Hanlon, T.; Mourer, D. Advanced supersolvus nickel powder disk alloy DOE: Chemistry, properties, phase formations and thermal stability. In Proceedings of the 13th Intenational Symposium of Superalloys (Superalloys 2016), Seven Springs, PA, USA, 11–15 September 2016; pp. 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P.L. Superalloy Compositions, Articles, and Methods of Manufacture. U.S. Patent Application No. 8,147,749, 10 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.M.; Gabb, T.P.; Wertz, K.N.; Stuckner, J.; Evans, L.J.; Egan, A.J.; Mills, M.J. Enhancing the creep strength of next-generation disk superalloys via local phase transformation strengthening. In Minerals Metals and Materials Series, Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Superalloys, Seven Springs, PA, USA, 12–16 September 2021; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 726–736. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.M. Producing Next Generation Superalloys Through Advanced Characterization and Manufacturing Techniques. In Proceedings of the Case Western Reserve University Seminar Series, Cleveland, OH, USA, 28 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christofidou, K.A.; Hardy, M.C.; Li, H.Y.; Argyrakis, C.; Kitaguchi, H.; Jones, N.G.; Mignanelli, P.M.; Wilson, A.S.; Messé, O.M.D.M.; Pickering, E.J.; et al. On the effect of Nb on the microstructure and properties of next generation polycrystalline powder metallurgy Ni-based superalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2018, 49, 3896–3907. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, M.C.; Argyrakis, C.; Kitaguchi, H.S.; Wilson, A.S.; Buckingham, R.C.; Severs, K.; Yu, S.; Jackson, C.; Pickering, E.J.; Llewelyn, S.C.H.; et al. Developing alloy compositions for future high temperature disk rotors. In Minerals Metals and Materials Series, Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Superalloys, Seven Springs, PA, USA, 12–16 September 2021; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Antonov, S.; Detrois, M.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.; Helmink, R.C.; Goetz, R.L.; Sun, E.; Tin, S. Comparison of thermodynamic database models and APT data for strength modeling in high Nb content γ–γ′ Ni-base superalloys. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, S.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Sun, E.; Helmink, R.C.; Seetharaman, V.; Tin, S. γ′ phase instabilities in high refractory content γ-γ′ Ni-base superalloys. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Superalloys, Seven Springs, PA, USA, 11–15 September 2016; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Antonov, S.; Huo, J.; Feng, Q.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Helmink, R.C.; Sun, E.; Tin, S. The effect of Nb on grain boundary segregation of B in high refractory Ni-based superalloys. Scr. Mater. 2017, 138, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, S.; Huo, J.; Feng, Q.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Helmink, R.C.; Sun, E.; Tin, S. σ and η Phase formation in advanced polycrystalline Ni-base superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 687, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, S.; Huo, J.; Feng, Q.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Sun, E.; Tin, S. Comparison of Thermodynamic Predictions and Experimental Observations on B Additions in Powder-Processed Ni-Based Superalloys Containing Elevated Concentrations of Nb. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, S.; Chen, W.; Huo, J.; Feng, Q.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Sun, E.; Tin, S. MC carbide characterization in high refractory content powder-processed Ni-based superalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 2340–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, A.J.; Rao, Y.; Viswanathan, G.B.; Smith, T.M.; Ghazisaeidi, M.; Tin, S.; Mills, M.J. Effect of Nb alloying addition on local phase transformation at microtwin boundaries in nickel-based superalloys. In Minerals Metals and Materials Series, Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Superalloys, Seven Springs, PA, USA, 12–16 September 2021; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 640–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lilensten, L.; Antonov, S.; Gault, B.; Tin, S.; Kontis, P. Enhanced creep performance in a polycrystalline superalloy driven by atomic-scale phase transformation along planar faults. Acta Mater. 2021, 202, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.D.; Meng, Q.Q.; Ning, Y.Q.; Huang, S.; Zhang, W.Y.; Zhang, B.J. Interfacial microstructure evolution behavior during plastic deformation bonding of GH4065A superalloy. J. Mater. Eng. 2025, 53, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.S.S.; Raghu, T.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; Rao, G.A.; Borah, U. Constitutive modeling for predicting peak stress characteristics during hot deformation of hot isostatically processed nickel-base superalloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 6444–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccarley, J.; Alabbad, B.; Tin, S. Influence of the starting microstructure on the hot deformation behavior of a low stacking fault energy Ni-based superalloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2018, 49A, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Singh, R.K.; Florist, V.; Pai, N.; Anoop, C.R.; Tripathy, D.; Murty, S.N. Effect of temperature and strain rate on the hot workability behaviour of Ni–25Cr–14W superalloy: An approach using processing map and constitutive equation. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 2397–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Yu, X.M.; Liu, L.R.; Chen, L.J. Elevated Temperature Compression Deformation Behavior and Mechanism of GH79 Superalloy. Rare Metal Mat. Eng. 2019, 48, 3939–3947. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G. Study on the Deformation Behavior and Microstructure Evolution Mechanism at Elevated Temperatures in High Superalloys. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Yang, Z.Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, H.Y.; Chen, L.J.; Guan, L. Thermocompression Deformation Behavior and Mechanism of Ni60Ti40 Alloy. Rare Metal. Mat. Eng. 2021, 50, 2385–2392. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E9-19; Standard Test Methods of Compression Testing of Metallic Materials at Room Temperature. American Society for Testing Material: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Kumar, S.S.; Raghu, T.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; Rao, G.A.; Borah, U. Evolution of microstructure and microtexture during hot deformation in an advanced P/M nickel base superalloy. Mater. Charact. 2018, 146, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Liu, W.C. Effect of the δ phase on the hot deformation behavior of Inconel 718. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2005, 408, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, T.G. A unified approach to grain boundary sliding in creep and superplasticity. Acta Metall. Mater. 1994, 42, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.D.; He, Y.J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.Y.; Zhu, L.H.; Guo, J.Z. Superplastic deformation behavior of nickel-based powder superalloy during isothermal hot compression. Rare Metal. Mat. Eng. 2022, 51, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E112-24; Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size. American Society for Testing Material: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Umemoto, M.; Hiramatsu, A.; Moriya, A.; Watanabe, T.; Nanba, S.; Nakajima, N.; Anan, G.; Higo, Y. Computer modelling of phase transformation from work-hardened austenite. ISIJ Int. 1992, 32, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Y.V.R.K. Processing maps: A status report. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2003, 12, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana Murty, S.V.S.; Nageswara Rao, B.; Kashyap, B.P. Instability criteria for hot deformation of materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 2000, 45, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundinya, N.T.B.N.; Sri Bharadwaj, K.; Nandha Kumar, E.; Narayana Murty, S.V.S.; Kottada, R.S. Understanding the hot working behavior of a Ni-base superalloy XH 67 via processing map approach. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2020, 9, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.R.; Cui, J.Z.; Wen, J.L. Deformation mechanism maps of magnesium lithium alloy and their experimental application. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2002, 12, 1146–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Ruano, O.A.; Wadsworth, J.; Sherby, O.D. Deformation mechanisms in an austenitic stainless steel (25Cr-20Ni) at elevated temperature. J. Mater. Sci. 1985, 20, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.R. Preparation of Ultralight Magnesium Alloys and Their Deformation Mechanism at Elevated Temperatures. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S.; Rüsing, J.; Herzig, C. Grain boundary self-diffusion of 63Ni in pure and boron-doped Ni3Al. Intermetallics 1996, 4, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).