Abstract

Li3PO4 is an ideal precursor for synthesizing high-performance LiFePO4, as it simultaneously provides lithium and phosphorus sources. Extremely low solubility of Li3PO4 enables efficient lithium recovery from low-concentration Li-rich brine by reactive crystallization. A focused beam reflectance measurement (FBRM) system was employed to monitor the key optimization parameters for Li3PO4 crystallization, supersolubility, and metastable zone widths (MSZWs). The optimized process parameters were determined by systematically investigating the effects of operating conditions. Additionally, prediction of supersolubility and MSZWs was accomplished with theoretical models. Results demonstrate that both supersolubility and MSZWs exhibit a pronounced negative correlation with temperature. Supersolubility decreased sharply when LiCl concentration exceeded 5 mol·L−1 or Na3PO4 concentration surpassed 0.8 mol·L−1. Conversely, it increased exponentially with Na3PO4 feeding rate. The effect of impurity (NaCl/KCl) was non-monotonic, initially increasing and then decreasing supersolubility and MSZWs. Among these, Na2B4O7 most significantly enhanced both parameters, followed by Na2SO4. The supersolubility data were well-fitted by an empirical equation (R2 > 0.99). For MSZWs prediction, the self-consistent Nývlt-like model (R2 > 0.9883) and the modified Sangwal’s model (R2 > 0.994) achieved superior performance. Collectively, these findings establish a theoretical basis for optimizing lithium recovery via Li3PO4 crystallization, facilitating more efficient and sustainable production of high-purity lithium products.

1. Introduction

Driven by the global energy transition and carbon neutrality goals, the demand for lithium products in the battery industry has experienced explosive growth in recent years [1,2,3]. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) is a preferred cathode material for electric vehicles [4,5], energy storage systems [6,7], and portable electronic devices [1] owing to its high energy density, long life cycle, and excellent safety performance. Furthermore, cathode materials constitute over 45% of the total battery cost [8]. Salt lake brine is a crucial lithium resource, accounting for approximately 66% of global lithium reserves [9]. In China, it represents a major lithium resource, accounting for 12.0% of the global total [10]. Dong-Taijinaier salt lake represents one of China’s largest and highest-quality brine-type lithium deposits [10]. Typically, the cost of producing lithium from salt lake brine is 30–50% lower than that from hard-rock sources [11]. Consequently, the extraction of lithium from salt lake brine has become a major trend in the industry.

Lithium phosphate (Li3PO4), a high-value-added lithium compound, has garnered significant interest for its applications in lithium-ion batteries [12,13,14,15,16], catalysts [17,18,19], phosphors [20], glass [21] and other advanced materials. Li3PO4 serves as an ideal precursor for synthesizing high-performance LiFePO4 cathode materials because it simultaneously provides both lithium and phosphorus sources [12,13,22]. With its low solubility (Ksp = 2.37 × 10−11 at 298.15 K), Li3PO4 can precipitate efficiently from solutions even at low lithium concentration, making it a promising candidate for enhancing lithium recovery rates [23,24,25,26]. Liu et al. [24] proposed a seed-induced precipitation method for recovering lithium from brine at low temperatures, utilizing facet-engineered Li3PO4 crystals as seeds and sodium phosphate dodecahydrate (Na3PO4·12H2O) as the precipitant. Zhao et al. [26] investigated the recovery of Li3PO4 from a lithium-containing solution (2 g·L−1) using solid sodium phosphate (Na3PO4) as the precipitant. Wang et al. [27] developed a tandem electro-leaching and solvent extraction method to selectively recover metals from spent LiNixCoyMn(1−x−y)O2. In this process, over 98.0% of Ni, Co, and Mn were selectively separated from Li via solvent extraction. Subsequently, using trisodium phosphate as a precipitant, battery-grade Li3PO4 with a purity of up to 99.5% was obtained. Xiao et al. [28] investigated the thermodynamics of Li3PO4 recovery, performing a thermodynamic analysis of the Li+, Fe3+/PO43−-H2O system at 298.15 K. Emmanuel et al. [29] studied a system in which lithium chloride and sodium phosphate are simultaneously injected into a microchannel, allowing the precipitation reaction to proceed under concentration gradients. The growth kinetics of individual precipitate particles were studied by monitoring particle growth both along and transverse to the flow direction. Collectively, these studies provide a foundation for enhancing lithium resource utilization efficiency and product quality to meet diverse market demands. Li3PO4 is typically produced by precipitation from lithium-containing solutions. Although the precipitation of Li3PO4 is a well-established method, there are no engineering and scientific approaches to the mechanism of Li3PO4 precipitation from Li-rich brine. This mechanism gap limits the efficiency of the Li3PO4 precipitation process and results in poor product quality. Therefore, a fundamental study on the reaction crystallization (precipitation) process of Li3PO4 is essential.

The supersolubility (csp) and metastable zone widths (MSZWs) are key parameters for optimizing the reactive crystallization of Li3PO4. Industrial crystallization processes are often operated within the metastable zone to obtain products with desirable characteristics, such as a uniform particle size distribution, high purity, and high yield. The supersolubility and MSZWs are influenced by several operational parameters, including temperature, impurities, reactant concentration, feeding rate, and stirring rate. Therefore, quantifying these parameters is essential for the rational design and operation of crystallization equipment. Wang et al. [30] investigated the supersolubility and solubility of Li3PO4 in Na2CO3 solution, providing fundamental physicochemical data and theoretical insights for the efficient separation and extraction of lithium from precipitation mother liquor. Several techniques, including conductivity [31], turbidity [32,33], laser method [34], and focused beam reflectance measurement (FBRM) [34,35,36,37], are employed to determine supersolubility and MSZWs. Among these, FBRM is a real-time analytical technique that rapidly provides crystal information based on chord length distribution (CLD), typically within seconds (e.g., a 2 s interval). The principles [38,39] and applications [34,35] of FBRM technology are detailed in the relevant literature. Furthermore, predictive models for supersolubility and MSZWs are important tools for generating necessary estimates. The Qinghai–Tibet Plateau in China contains hundreds of salt lakes rich in lithium resources. Currently, the production of Li2CO3 from the Dong-Taijinaier salt lake requires concentrating the lithium-containing brine to a Li+ concentration above 20 g·L−1 prior to precipitation. However, this process is not only energy-intensive but also results in a relatively low lithium recovery rate (approximately 80%), owing to the higher solubility of Li2CO3 (13.3 g·L−1 at 293.15 K) compared to that of Li3PO4. Therefore, developing a method for the direct recovery of lithium from low concentration Li-rich brine ([Li+] = 8.9 g·L−1) in the Dong-Taijinaier salt lake via phosphate precipitation is of great significance. However, the presence of co-existing impurities (e.g., NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and Na2B4O7) in Li-rich brine can significantly influence the crystallization behavior of Li3PO4, posing a major challenge for its efficient precipitation. Our previous work investigated the dissolution thermodynamics of Li3PO4 in mixed salt solutions (LiCl-NaCl-KCl-Na2SO4-Na2B4O7) [40]. Building upon the foundation, this study employs FBRM to systematically investigate the supersolubility and MSZWs of Li3PO4 in both a synthetic mixed-salt system and an authentic Li-rich brine. The purpose of this study is to determine the optimal crystallization process parameters for the efficient recovery of Li3PO4 from Li-rich brine and to develop an accurate predictive model for the MSZWs of its reactive crystallization.

2. Theory

2.1. Metastable Zone Widths

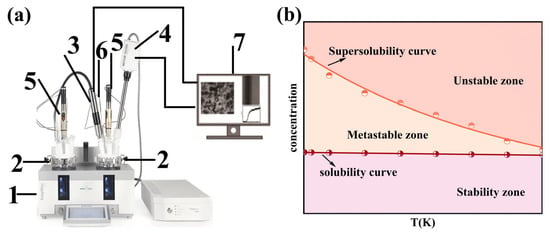

The metastable zone (Figure 1), bounded by the solubility and supersolubility curves, represents a state of supersaturation where spontaneous nucleation does not occur within a sufficiently short time. Operating within the metastable zone enables precise control over crystal quality and particle size. Exceeding it leads to uncontrolled crystallization, characterized by burst nucleation and undesirable product qualities. The supersolubility is influenced by many factors, including reactant concentration, stirring rate, feeding rate, presence of impurities, and addition of crystal seeds. Consequently, the MSZWs are a key characteristic of any crystallization system. It is quantitatively defined as the difference between the supersolubility (csp) and solubility (cs), expressed as Δc = csp − cs.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of supersolubility measurements. (1) fully automated synthesis reactor; (2) glass reactor; (3) FBRM detection system; (4) PVM detection system; (5) stirrer; (6) temperature detection probe; (7) computer. (b) Schematic diagram of the metastable zone.

2.2. Calculation of Supersolubility

Owing to the lack of activity coefficients for Li+ and PO43− in the multi-component system, the supersaturation of Li3PO4 cannot be directly calculated using the rigorous definition in Equation (1). Consequently, a simplified approach, justified by the low solubility of Li3PO4, is employed in Equation (2) [41] for practical applications. The supersolubility can then be determined using Equations (3) and (4).

where Ksp denotes the solubility product constant of Li3PO4; S, csp, cs, and Ssp represent the relative supersaturation, supersolubility (mol·L−1), solubility (mol·L−1), and the relative supersaturation at csp, respectively.

2.3. MSZWs Predictions Models

The MSZWs are influenced by process parameters and vary significantly across different chemical systems. Nývlt [42] proposed the first semiempirical model for MSZWs prediction. This model later evolved into Sangwal’s theory [43], both of which incorporate the nucleation order, system dimensions, and saturation temperature. In this work, the self-consistent Nývlt-like model, Sangwal’s theory model, and the modified Sangwal’s theory model were employed to predict the MSZWs for the reactive crystallization of Li3PO4.

Expressed in terms of concentration instead of temperature, the self-consistent Nývlt-like model, Sangwal’s theory model, and modified Sangwal’s theory model are given by Equations (5)–(7), respectively.

where U is the feeding rate of Na3PO4 solution (mL·min−1); c is the concentration of Na3PO4 solution (mol·L−1); f is the proportionality constant; K is the nucleation rate constant, m represents the apparent nucleation order; F1 represents the slope, and F represents the intercept. N represents the slope and M the intercept.

3. Experiment

3.1. Materials and Methods

All chemical reagents used in the experiments were of analytical grade, and their details are provided in Table 1. Ultrapure water (resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm at 298.15 K) was degassed by boiling prior to the preparation of all electrolyte solutions. The density and pH of the Li-rich brine were determined as described in previous studies [40]. In this study, “Li-rich brine” is defined as the unconcentrated, lithium-containing solution from the Dong-Taijinaier salt lake, used prior to Li2CO3 precipitation. Its detailed composition is listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Chemical reagents employed.

Table 2.

Major ion composition of the Li-rich brine [40].

3.2. Experiment Setup

The supersolubility was determined using FBRM (G400, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA), as illustrated in Figure 1. To ensure data reliability, particle vision and measurement (PVM) (V19, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) was employed concurrently for monitoring. The relative backscatter index (RBI) from PVM serves as a process trend indicator sensitive to particulate changes and was used to identify nucleation points [44]. The FBRM probe, with a measurement range of 0.5–2000 µm, was operated at a scan speed of 2 m/s with a 2 s measurement duration. Time averaging and chord length weighting were disabled to capture high-fidelity data during rapid nucleation events. PVM sampling was set to 1 frame per 2 s. All experiments were conducted in a 100 mL glass crystallizer within a fully automated synthesis reactor (Easymax 102, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA). The system was equipped with an internal overhead stirrer, and the temperature was controlled to within ±0.1 K throughout the experiments.

3.3. Supersolubility Measurements

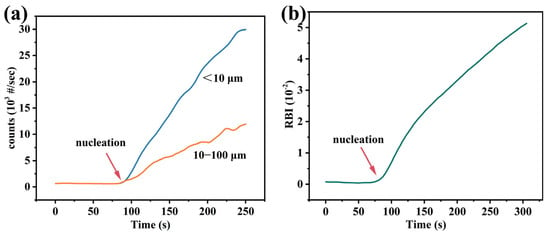

To measure supersolubility, 50 mL of a 1.3 mol·L−1 LiCl solution or Li-rich brine was added to the crystallizer. The overhead stirrer, temperature probe, FBRM, and PVM probes were then immersed in the solution adjacent to the stir rod. The system (Easymax102, iControl, version 6.0) was programmed to maintain a constant temperature and a stirring speed of 400 rpm. The experiment was initiated once the solution temperature had stabilized. An isothermal Na3PO4 solution (0.4 mol·L−1) was then titrated into the LiCl solution or Li-rich brine using a liquid dosing system at a constant rate of 0.5 mL·min−1. The initial baseline was characterized by a stable total chord count. Upon the onset of burst nucleation, indicated by a sharp increase in the total chord count (Figure 2), the dosing pump was immediately stopped. The time interval from the start of dosing to the nucleation point was recorded as the pumping time. The supersolubility was then calculated from the total amount of Na3PO4 added, which was the product of the dosing rate and the recorded pumping time. Each measurement was performed in at least triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

Figure 2.

(a) FBRM and (b) PVM data at the point of nucleation at a temperature of 308.15 K.

4. Results and Discussion

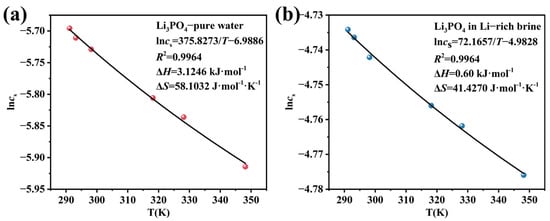

4.1. Solubility of Li3PO4

The direct determination of Li3PO4 solubility in pure water is challenging because the formation of a fine colloid impedes effective filtration [45]. Wu et al. [46] pointed to the ongoing hydrolysis of PO43− and the dissolution-conversion of Li3PO4 with increasing time, which prevents the attainment of a stable equilibrium for accurate solubility measurement. The solubility value of Li3PO4 in pure water, widely used in important manuals at present, is 0.394 g/kg at 291.15 K. In our previous study [40], the solubilities of Li3PO4 in both pure water and Li-rich brine were measured via the isothermal dissolution equilibrium method [47,48] across a temperature range of 291.15 to 348.15 K; these data are summarized in Table 3. The solubility values obtained in our previous work [40] were slightly higher than those reported by Wu et al. [46], a discrepancy likely attributable to differences in the dissolution time. The solubility data were fitted using the van’t Hoff equation, as shown in Figure 3. The high coefficient of determination (R2 > 0.996) for both systems indicates an excellent fit to the model.

where cs is the equilibrium concentration of solute (molality mol·L−1), and T is the temperature (K). ΔH is the dissolution enthalpy (kJ·mol−1), ΔS is the dissolution entropy (J·mol−1·K−1), they are obtained from the slope and intercept of the fitted line, respectively. R is the gas constant 8.314 J·K−1·mol−1.

Table 3.

The solubility of Li3PO4 at different temperatures.

Figure 3.

Correlation of Li3PO4 solubility with temperature (291.15–348.15 K) using the van’t Hoff equation for (a) pure water and (b) Li-rich brine.

4.2. Supersolubility and MSZWs

4.2.1. Impact of Temperature

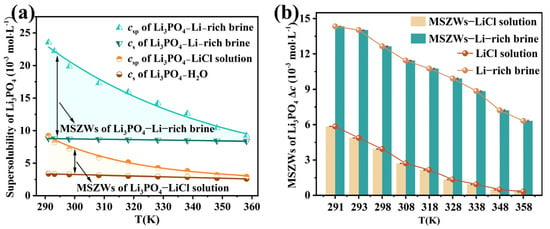

The supersolubility of Li3PO4 in LiCl solution and Li-rich brine was determined over the temperature range of 291.15 K to 363.15 K, as presented in Table 4 and Figure 4a. The supersolubility decreased markedly with increasing temperature, exhibiting a strong inverse dependence. The supersolubility results for Li3PO4 in LiCl solution are in satisfactory agreement with the literature values [30]. Specifically, the supersolubility values of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine (19.837 × 10−3 mol·L−1 at 298.15 K; 12.632 × 10−3 mol·L−1 at 338.15 K) agrees well with the values reported in a 1.3Li-0.5K-1.3Na-0.1S-0.01B mixed salt solution (20.115 × 10−3 mol·L−1 and 12.580 × 10−3 mol·L−1 at the corresponding temperatures). This agreement suggests that the supersolubility in Li-rich brine is primarily governed by the impurities KCl, NaCl, Na2SO4, and Na2B4O7, whereas the effects of other potential impurities are negligible. The metastable zone for Li3PO4 in LiCl solution and Li-rich brine is indicated by the yellow and green areas in Figure 4a, respectively. As shown in Figure 4b, the MSZWs gradually decrease with increasing temperature. Elevated temperatures reduce solution viscosity, which accelerates molecular motion, increases molecular collision frequency, and enhances mass transport. These factors collectively increase the likelihood of nucleation. Furthermore, higher temperatures lower the surface tension, thereby facilitating nucleus formation. Consequently, the MSZWs narrow with increasing temperature [49,50,51].

Table 4.

Supersolubility csp of Li3PO4 in LiCl solution and Li-rich brine at temperatures T = (291.15–363.15) K, pressure p = 0.1 MPa. a

Figure 4.

(a) Supersolubility and (b) MSZWs of Li3PO4 in LiCl solution and Li-rich brine over the temperature range of 291.15 K to 363.15 K.

To maximize crystallization yield, a higher operating temperature is generally preferable. However, the crystallization process must be controlled within the metastable zone. If the MSZWs become too narrow for precise process control, various factors must be considered when determining the optimal operating conditions.

4.2.2. Impact of Operating Conditions

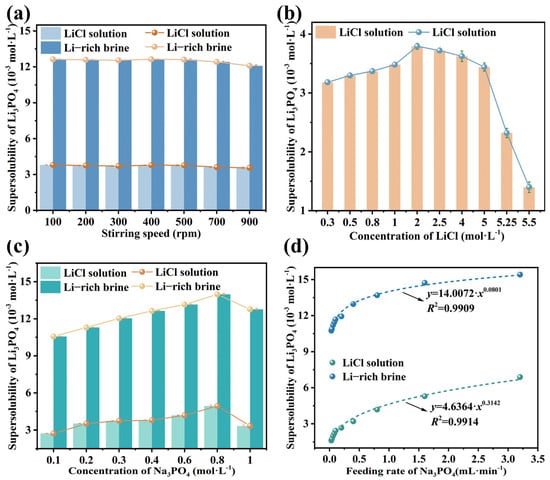

Stirring Speed: the supersolubility was determined across a stirring speed range of 100 to 900 rpm under the following conditions: a Na3PO4 solution feeding rate of 0.5 mL·min−1, with LiCl and Na3PO4 concentrations of 1.3 and 0.4 mol·L−1, respectively, as shown in Figure 5a. It can be seen that an increase in stirring speed leads to a slight decrease in supersolubility. Related studies suggest that stirring exerts two opposing effects: it accelerates mass transfer and facilitates nucleation, yet it may also disrupt crystal embryos and impede nucleus formation. The net effect on supersolubility is thus a synergy of these competing mechanisms. This dual mechanism may account for the slight increase in supersolubility observed at 400 rpm.

Figure 5.

The influence of operating conditions on the supersolubility of Li3PO4 at 338.15 K (a) impact of stirring speed; (b) impact of LiCl concentration; (c) impact of Na3PO4 concentration; (d) impact of feeding rate of Na3PO4.

LiCl Concentration: the reactive crystallization of LiCl and Na3PO4 is an important industrial process. Therefore, determining an optimal LiCl concentration range is critical. The dependence of supersolubility on LiCl concentration (0–5.5 mol·L−1) as investigated at a constant stirring speed of 400 rpm, with the Na3PO4 solution fed at 0.5 mL·min−1 and a concentration of 0.4 mol·L−1, as shown in Figure 5b. A steep decline in the supersolubility of Li3PO4 is observed when the LiCl concentration exceeds 5 mol·L−1. This decline is attributed to the significantly accelerated reaction and nucleation rates at high LiCl concentrations, which markedly reduce the supersolubility. Supersaturation levels approaching or exceeding this limit promote burst nucleation, leading to the formation of fine crystals that are difficult to filter and wash, ultimately yielding a product with suboptimal purity and morphology. Moreover, concentrating dilute raw materials to such high levels is both energy- and time-intensive. Therefore, LiCl concentrations exceeding 5 mol·L−1 should be avoided.

Na3PO4 Concentration: the dependence of supersolubility on Na3PO4 concentration (0.1–1 mol·L−1) was determined under the following conditions: a Na3PO4 feeding rate of 0.5 mL·min−1, a stirring speed of 400 rpm, and a LiCl concentration of 1.3 mol·L−1, as shown in Figure 5c. It can be seen that the supersolubility initially increased with Na3PO4 concentrations, reaching a maximum before gradually decreasing at concentrations exceeding 0.8 mol·L−1. This non-monotonic trend is governed by concentration-dependent nucleation kinetics. At lower Na3PO4 concentrations, Li3PO4 crystal nuclei may dissolve before growing to a detectable size for the FBRM probe. In contrast, higher concentrations significantly accelerate the reaction and nucleation rates, promoting rapid nucleus growth and detection, thereby reducing the supersolubility. Since a wider metastable zone width is generally desirable for process control, the Na3PO4 concentration should be maintained at or below 0.8 mol·L.

Feeding Rate of Na3PO4: the dependence of supersolubility on the feeding rate of Na3PO4 (0.03–3.2 mL·min−1) was determined at a stirring speed of 400 rpm, with LiCl and Na3PO4 concentrations of 1.3 and 0.4 mol·L, respectively, as shown in Figure 5d. It can be seen that the supersolubility of Li3PO4 increases exponentially with the Na3PO4 feeding rate. This trend is attributed to the interplay between the continuous addition of reactant and the finite induction period required for nucleation. A higher feeding rate introduces more Na3PO4 into the LiCl solution before nucleation commences, thereby generating a greater degree of supersaturation and resulting in higher supersolubility. This behavior is analogous to that observed in cooling crystallization [52,53,54], where supersolubility increases with the cooling rate. In essence, both the reactant feeding rate and the cooling rate govern the rate of supersaturation generation. Thus, it can be concluded that for a given substance, a higher supersaturation generation rate leads to a higher supersolubility. Furthermore, the experimental data were well-fitted by an exponential equation (R2 > 0.99), confirming the model’s effectiveness in predicting the supersolubility of Li3PO4.

4.2.3. Impact of Impurities

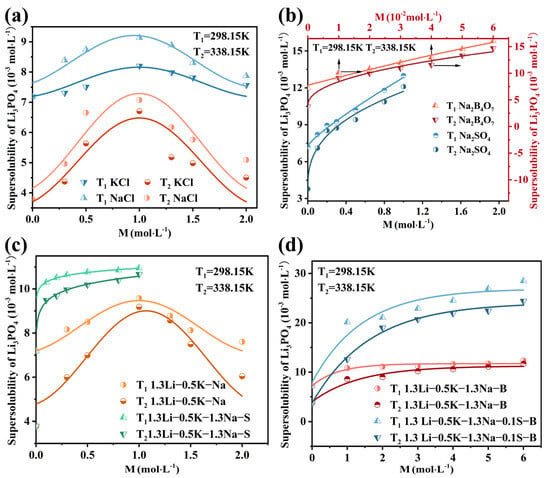

Single Salts System: the primary concomitant salts in the Li-rich brine of the Dong-Taijinaier salt lake are KCl, NaCl, Na2SO4, and Na2B4O7; thus, these were selected as representative impurities for this study. The supersolubility csp of Li3PO4 in single salt solutions KCl (0–2 mol·L−1), NaCl (0–2 mol·L−1), Na2SO4 (0–1 mol·L−1), and Na2B4O7 (0–0.06 mol·L−1) is determined at 298.15 K and 338.15 K (Figure 6a,b). A general trend of decreasing supersolubility with increasing temperature was observed across all systems.

Figure 6.

The supersolubility of Li3PO4 at 298.15 K and 338.15 K: (a,b) in single salt systems and (c,d) in the Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S mixed salt systems. The upward and rightward arrows denote the positive directions of the data’s x-axis and y-axis, respectively.

In NaCl and KCl solutions, the supersolubility of Li3PO4 initially increased, reached a maximum, and then gradually decreased with increasing salt concentration. This non-monotonic behavior can be attributed to evolving ion-pair structures. As the concentration of NaCl or KCl increases, the solution microstructure transitions from containing free hydrated ions and solvent-separated ion pairs (SIPs) to an increasing proportion of contact ion pairs (CIPs) and more complex ion associates. The initial increase in supersolubility is likely promoted by free ions and SIPs, while the subsequent decline is dominated by the effects of CIPs. In contrast, the supersolubility in Na2SO4 and Na2B4O7 solutions increased monotonically with concentration, with Na2B4O7 exerting a more pronounced effect. This indicates a dominant “salting-in” effect. Furthermore, NaCl demonstrated a stronger salting-in influence on Li3PO4 supersolubility than KCl at equivalent concentrations. These observations suggest that the impurities alter the solubility product constant via a thermodynamic mechanism, consistent with reported trends for Li2CO3 in salt solutions [41,55], implying a potentially shared thermodynamic origin.

Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S Mixed-Salt System: the supersolubility csp of Li3PO4 was determined in four mixed-salt solutions (compositions detailed in Table 5) at 298.15 K and 338.15 K. The results are summarized in Figure 6c,d. A general decrease in supersolubility was observed with increasing temperature. In the 1.3Li-0.5K-Na system, the supersolubility exhibited a non-monotonic dependence on NaCl concentration, initially increasing to a maximum before gradually decreasing. This suggests that NaCl and KCl exert a salting-in effect on Li3PO4 at low concentrations and a salting-out effect at high concentrations. The supersolubility of Li3PO4 increased monotonically with the concentration of Na2SO4 or Na2B4O7 in the 1.3Li-0.5K-1.3Na-S, 1.3Li-0.5K-1.3Na-B, and 1.3Li-0.5K-1.3Na-0.1S-B systems, indicating a dominant salting-in effect. Notably, Na2B4O7 exerted a more pronounced effect on enhancing supersolubility than Na2SO4. These results demonstrate that the supersolubility of Li3PO4 during crystallization can be effectively modulated by controlling the concentrations of specific impurities (NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and Na2B4O7) in the Li-rich brine.

Table 5.

Four solutions with different mixed-salt compositions.

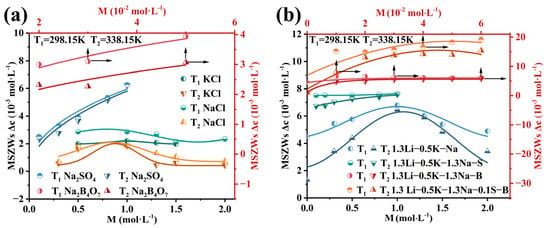

MSZWs of Li3PO4 in Single and Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S Mixed-Salt Solutions: the MSZWs were calculated from previously reported solubility data for Li3PO4 in single-salt (NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and Na2B4O7) and Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S mixed-salt solutions [40]. As shown in Figure 7a,b, the MSZWs of Li3PO4 decreased with increasing temperature across all systems. Notably, the variation in the MSZWs with solution composition closely paralleled the corresponding trends in supersolubility, indicating that the MSZWs are primarily governed by the supersolubility.

Figure 7.

The MSZWs of Li3PO4 at 298.15 K and 338.15 K in (a) single-salt systems and (b) Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S mixed-salt systems. The upward and rightward arrows denote the positive directions of the data’s x-axis and y-axis, respectively.

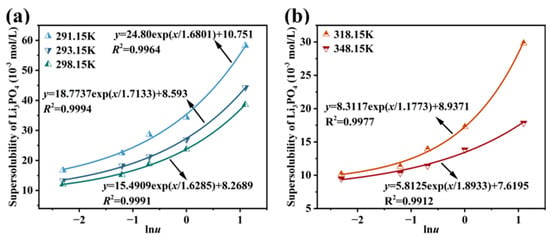

4.3. Supersolubility and MSZWs Predictions

4.3.1. Supersolubility Predictions

Based on experimental results identifying temperature and Na3PO4 feeding rate as the primary factors influencing supersolubility, the supersolubility of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine was modeled as a function of these two variables. The experimental conditions were as follows: Li-rich brine with a LiCl concentration of 1.3 mol·L−1, a temperature range of 291.15 K to 348.15 K, and Na3PO4 feeding rates of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0 mL·min−1. The supersolubility data were fitted to an empirical equation, as shown in Figure 8a,b. The high coefficient of determination (R2 > 0.99) confirms that the equation effectively predicts supersolubility within the experimental range. Furthermore, the model demonstrates better accuracy at lower temperatures compared to higher temperatures.

Figure 8.

Correlation of Li3PO4 supersolubility using an empirical equation at different temperatures: (a) 291.15 K, 293.15 K, and 298.15 K; (b) 318.15 K and 348.15 K.

4.3.2. MSZWs Predictions

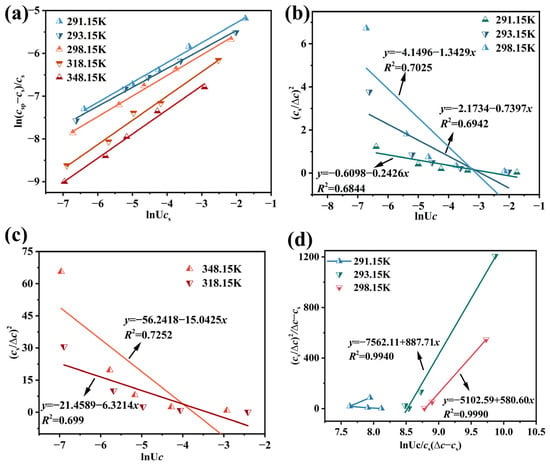

The linear solubility of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine indicates a constant temperature coefficient (dcs/dT)T, independent of the saturation temperature. This relationship justifies the application of both Nývlt’s and Sangwal’s theories to correlate the MSZWs data and estimate the nucleation kinetics [56]. Figure 9 presents the corresponding fitting results obtained from the self-consistent Nývlt-like model, Sangwal’s model, and the modified Sangwal’s model.

Figure 9.

Correlation between feeding rate and MSZWs of Li3PO4 as described by different models: (a) self-consistent Nývlt-like model, (b,c) Sangwal’s theory, and (d) modified Sangwal’s theory.

Self-consistent Nývlt-like Model: the MSZWs data were fitted using the self-consistent Nývlt-like model (Equation (5)), which establishes a linear relationship between ln(Δc/cs) and lnUc. The fitting results at different temperatures are presented in Figure 9a and Table 6. The slope of the linear regression, corresponding to 1/m, increased with temperature, indicating a corresponding decrease in the apparent nucleation order m. Concurrently, the intercept φ decreased from −4.3534 to −5.0622. The derived parameter f/K decreased from 0.008546 to 0.004027. The coefficients of determination (R2) for all fits were high, ranging from 0.9883 to 0.9954, confirming the model’s reliability. The overall strong agreement between the model and experimental data demonstrates that the Nývlt-like model is a reliable tool for predicting the MSZWs of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine.

Table 6.

Estimated nucleation kinetics parameters and coefficient of determination from the self-consistent Nývlt-like model.

Sangwal’s Theory Model: according to Sangwal’s theory (Equation (6)), a linear correlation between (cs/∆c)2 and lnUc was evaluated, as shown in Figure 9b,c. However, the coefficients of determination (R2) for these fits were relatively low, ranging from 0.6844 to 0.7252 (Table 7), indicating a poor fit to the experimental data. Consequently, Sangwal’s theory is not suitable for predicting the MSZWs of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine. This discrepancy is likely because Sangwal’s theory was developed for systems with fixed composition and is less applicable to reactive crystallization, where the solution composition changes over time [56]. This evolving composition affects the fundamental parameter F in the model, thereby compromising its predictive accuracy.

Table 7.

Estimated nucleation kinetics parameters and coefficient of determination from Sangwal’s theory.

Modified Sangwal’s Theory Model: the modified Sangwal’s theory (Equation (7)) was applied, which posits a linear relationship between (cs/∆c)2/(∆c − cs) and lnUc/cs(∆c − cs), as illustrated in Figure 9d. The corresponding coefficients of determination (R2) were exceptionally high, ranging from 0.994 to 0.999 (Table 8), confirming the model’s excellent fit and its suitability for predicting the MSZWs of Li3PO4 in Li-rich brine within the studied temperature range (293.15 K to 348.15 K). However, the modified theory has a significant limitation: the term (∆c − cs) can attain negative values under certain conditions. When this occurs, the mathematical formulation of the model breaks down, preventing a physically meaningful prediction. This situation typically arises when the metastable zone width is too narrow for the model’s assumptions to hold, thereby limiting its practical application.

Table 8.

Estimated nucleation kinetics parameters and coefficient determination from the modified Sangwal’s theory.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the crystallization behavior of Li3PO4 from Li-rich brine by measuring its supersolubility and MSZWs using FBRM. The effects of key operating parameters, including temperature, stirring speed, LiCl concentration, Na3PO4 concentration, and feeding rate, and impurities were systematically examined. The results demonstrate that supersolubility and MSZWs exhibit a strong inverse dependence on temperature. An increase in stirring speed caused a slight decrease in supersolubility. A steep decline in supersolubility was observed at LiCl concentrations exceeding 5 mol·L−1 and at Na3PO4 concentrations above 0.8 mol·L−1. In contrast, supersolubility increased exponentially with the Na3PO4 feeding rate. The influence of NaCl and KCl impurities was non-monotonic, initially increasing and then decreasing supersolubility with concentration. Among the impurities, Na2B4O7 had the most significant effect on enhancing supersolubility, followed by Na2SO4. Consequently, to optimize the reaction crystallization process, we recommend maintaining LiCl and Na3PO4 concentrations below 5 mol·L−1 and 0.8 mol·L−1, respectively, with a stirring speed of 400 rpm. This confines the crystallization to a controllable metastable zone, effectively suppressing burst nucleation and thereby facilitating precise control over product quality. Moreover, concentrating dilute raw materials to such high levels is both energy- and time-intensive. Furthermore, supersolubility can be tuned by controlling impurity levels. An empirical equation (R2 > 0.99) effectively predicted supersolubility. For MSZWs prediction, the self-consistent Nývlt-like model (R2 > 0.9883) and the modified Sangwal’s model (R2 > 0.994) demonstrated superior accuracy. This study provides critical insights for the industrial implementation of an efficient crystallization process to recover Li3PO4 from Li-rich brine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and X.D.; methodology, J.F.; Software, J.F. and X.H.; validation, J.F., G.X. and W.M.; formal analysis, G.X. and Z.H.; investigation, C.Z. and B.L.; resources, X.D. and B.L.; data curation, X.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, W.M. and X.H.; visualization, X.H.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, X.D.; funding acquisition, X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Major Demonstration Project of CAS (The funder: Chinese Academy of Sciences; Funding number: IAGM-2019-A04) and the Hong Guang Special Project of CAS (The funder: Chinese Academy of Sciences; Funding number: KFJ-HGZX-008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely expresses gratitude to all co-authors for their invaluable theoretical contributions and steadfast support throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had a role in the design of the study, writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Saasi, A.; Colosi, L.; Geise, G.; Koenig, G. Lithium capture from simulated geothermal brine via chemical reduction of iron phosphate in a packed bed reactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Karamat, S.; Numan, A. Progress and challenges in metal oxide-based flexible Li-ion batteries for robust and wearable applications. J. Power Sources 2025, 657, 238164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Fan, S.; Ma, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhou, W.; Wen, G.; Huang, X. Tailored active solid electrolyte interphase realizing the high-capacity flexible lithium storage electrode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthami, C.; Venu Vinod, A.; Pandey, M.; Kumar, H.; Vijay, R.; Anandan, S. Ultra high-rate performance LiFePO4 cathode material for next generation fast charging Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 660, 238537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y. External pressure effects on thermal runaway in prismatic LiFePO4 batteries: Mechanistic insights for safer battery systems in electric vehicles. eTransportation 2025, 26, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’Amar, K.; Sajid, M.; Bicer, Y.; Al-Ansari, T. Thermal assessment of pole-integrated LiFePO4 energy storage system for arid and non-maintainable locations—A case study in Qatar. J. Power Sources 2025, 660, 238444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkardouch, S.; Abouricha, S.; Sabi, N.; Aziam, H.; Bouharras, F.; Oukhrib, A.; Lahcini, M.; Oueldna, N.; Ben Youcef, H. Chitosan-phosphate enhanced solid electrolytes for safer, electrochemically stable all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 656, 238030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhang, Q. Research progress and prediction of lithium iron phosphate cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Technol. Chem. Ind. 2024, 32, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disu, B.; Rafati, R.; Sharifi Haddad, A.; Mendoza Roca, J.; Iborra Clar, M.; Soleymani Eil Bakhtiari, S. Review of recent advances in lithium extraction from subsurface brines. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 241, 213189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Han, W.; Zhang, H. Source Analysis of Lithium Deposit in Dong-Xi-Taijinaier Salt Lake of Qaidam Basin, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yun, R.; Xiang, X. Recent advances in magnesium/lithium separation and lithium extraction technologies from salt lake brine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Wu, X. Green Phosphate Route of Regeneration of LiFePO4 Composite Materials from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, T.; Ren, G.; Zhao, Z.; He, L.; Xu, W.; You, X. A novel approach for the direct production of lithium phosphate from brine and the synthesis of lithium iron phosphate. Desalination 2024, 587, 117952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, F.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ma, X.; Zi, Z. Effect of Particle Size of Li3PO4 on LiFePO4 Cathode Material Properties Prepared by Hydrothermal Method. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.; Haufe, L.; Zhang, J.; Wenzel, M.; Kremer, T.; Urbano, J.; Balducci, A.; Du, H.; Weigand, J. A closed process for recycling and re-synthesis of spent LiFePO4 cathode material. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 223, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershina, S. Compatibility between Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3-based solid electrolyte and LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode. Solid State Ion. 2025, 427, 116896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, X.; Wu, D.; Xiao, P. Sustainable activation of sulfite by oxygen vacancies-enriched spherical Li3PO4-Co3O4 composite catalyst for efficient degradation of metronidazole. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Ma, W. Enhanced activity for gas phase propylene oxide rearrangement to allyl alcohol by Au promotion of Li3PO4 catalyst. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 279, 120922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Ma, W. Facile Fabrication of Hollow Li3PO4 Catalyst via Ostwald Ripening. Nano 2018, 13, 1850004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahare, P.; Bai, B.; Sahare, A.; Chen, H. Study of Li3PO4:Dy3+ TLD phosphor for its application in high-temperature environment dosimetry of UV, X-rays and γ-rays. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 182473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, C.; Fan, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of various nucleating agents on the crystallization and properties of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2025, 133, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, G.; Liu, L.; Li, P.; Xu, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, L. Facile fabrication of compact LiFePO4/C composite with excellent atomically-efficient for high-energy-density Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2021, 496, 229759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiong, J.; Xu, W.; He, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z. Lithium selective extraction from lithium-enriched solution by phosphate precipitation. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2021, 31, 2541–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.; He, L.; Zhao, Z. Facet engineered Li3PO4 for lithium recovery from brines. Desalination 2021, 514, 115186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; He, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, X. Separation and recovery of lithium from Li3PO4 leaching liquor using solvent extraction with saponified D2EHPA. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 229, 115823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, H.; Zheng, X.; Van Gerven, T.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Z. Dataset of lithium phosphate recovery from a low concentrated lithium-containing solution. Data Brief 2019, 25, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Shen, J.; Zhang, F.; Qi, H.; Jin, W. Selective metal recovery from spent LiNixCoyMn(1−x−y)O2 battery via the tandem electro-leaching and solvent extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 375, 133761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zeng, L. Thermodynamic study on recovery of lithium using phosphate precipitation method. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 178, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, M.; Horváth, D.; Tóth, Á. Flow-driven crystal growth of lithium phosphate in microchannels. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 4887–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Ge, H.; Luo, Z.; Wang, M. Supersolubility and solubility of lithium phosphate in sodium carbonate solution. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22376–22385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Qian, H.; Wang, Z.; Qian, W.; Wu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z. Thermodynamic properties of evaporative crystallization of high-salt wastewater. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 196, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, R.; Yin, H.; Yuan, S. Study on the nucleation kinetics of DL-methionine based on the metastable zone width of unseeded batch crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 2023, 601, 126941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkian, M.; Manteghian, M.; Safari, M. Caffeine metastable zone width and induction time in anti-solvent crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 2022, 594, 126790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Yin, S. Nucleation metastable zone and induction time analysis of Li2CO3 in reactive crystallization: Effects of process parameters and impurities. Desalination 2025, 616, 119407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Alivand, M.; Hu, G.; Stevens, G.; Mumford, K. Nucleation kinetics of glycine promoted concentrated potassium carbonate solvents for carbon dioxide absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ulrich, J. Nucleation Behavior in a Transformation of the Amorphous State to the Crystalline State during Antisolvent Crystallization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 7052–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsamai, P.; Wantha, L.; Flood, A.; Tangsathitkulchai, C. In-situ measurement of the primary nucleation rate of the metastable polymorph B of L-histidine in antisolvent crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 2019, 525, 125209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoumi, A.; Nguyen, T.; Le, T.; Kraiem, H.; Cescut, J.; Anne-Archard, D.; Gorret, N.; Molina-Jouve, C.; To, K.; Fillaudeau, L. Comparison of methods to explore the morphology and granulometry of biological particles with complex shapes: Interpretation and limitations. Powder Technol. 2023, 415, 118067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Shan, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huo, Y.; Xu, Q. Crystal measurement technologies for crystallization processes: Advances, applications, and challenges. Measurement 2024, 231, 114672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ma, W.; He, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xu, G.; He, Z.; Zhu, F.; Deng, X. Solubility, Correlation and Thermodynamic Properties of Li3PO4 in Li-Na-K-B-Cl-S System and Its Application; SRRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, J. Unseeded Supersolubility of Lithium Carbonate: Experimental Measurement and Simulation with Mathematical Models. J. Cryst. Growth 2009, 311, 4714–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nývlt, J.; Söhnel, O.; Matuchová, M.; Broul, M. The Kinetics of Industrial Crystallization; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. 350. [Google Scholar]

- Sangwal, K. Novel Approach to Analyze Metastable Zone Width Determined by the Polythermal Method: Physical Interpretation of Various Parameters. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G. Dynamic floc characteristics of flocculated coal slime water under different agent conditions using particle vision and measurement. Water Environ. Res. 2020, 92, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertesin, A. Solubility Data Series, Jitka Eysseltová; Dirkse, T.P., Ed.; IUPAC: Oxford, UK, 1988; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zan, C.; Zhou, H. Process of Deep Recovery of Lithium from the Mother Liquor of Lithium Carbonate by Phosphate Precipitation. J. Tianjin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S. Development of a thermodynamic model for the Li2CO3-NaCl-Na2SO4-H2O system and its application. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2018, 123, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, Z.; Cheng, F. Solubility of Li2CO3 in Na–K–Li–Cl brines from 20 to 90 °C. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2013, 67, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairu, A.; Huang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, B.; Hao, H. Metastable zone width and nucleation kinetics of vanillyl alcohol crystallization in various solvents. J. Cryst. Growth 2024, 648, 127890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Lv, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. How to intensify nucleation of ultra-wide metastable zone widths: Case study of 4,4′-Oxydianiline. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 375, 133828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Yan, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X. Insight into the nucleation behavior of tiamulin hydrogen fumarate methanol solvate in methanol-ethyl acetate binary mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 398, 124179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, G.; Huang, B.; Wen, Z.; Li, W.; Luo, L. Nucleation thermodynamics and nucleation kinetics of (NH4)2SO4 under the action of NH4Cl. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, M.; Vashishtha, M.; Walker, G.; Kumar, K. Process Analytical Technology Obtained Metastable Zone Width, Nucleation Rate and Solubility of Paracetamol in Isopropanol-Theoretical Analysis. Pharmaceuticacls 2025, 18, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wu, B.; Ji, L. Study on Dissolution Thermodynamics and Cooling Crystallization of Rifamycin S. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 3752–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Du, B.; Wang, M. Study of the Solubility, Supersolubility and Metastable Zone Width of Li2CO3 in the LiCl–NaCl–KCl–Na2SO4 System from 293.15 to 353.15K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, C.; Gao, J.; Yang, H.; Tang, W.; Gong, J.; Zhou, F.; Gao, Z. Artificial Neural Network Prediction of Metastable Zone Widths in Reactive Crystallization of Lithium Carbonate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 7765–7776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).