Abstract

Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O single crystal was grown via slow solvent evaporation at room temperature. The magnetic and magnetocaloric properties were investigated. The results show that Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O exhibits paramagnetic behavior across 2–300 K. The maximum magnetic entropy change (−ΔSM) of 13.90 J kg−1 K−1 under conditions of 2 K and μ0ΔH = 5 T approaches the theoretical value of 14.58 J kg−1 K−1. In addition, the variation of −ΔSM with temperature is relatively flat, suggesting a wide working temperature range for magnetic refrigeration, which provides the possibility for the application of Co2+-based compounds in the field of low-temperature magnetic refrigeration.

1. Introduction

Cryogenic environments play a pivotal role in achieving breakthroughs in quantum computing, superconductivity, and spaceborne detector systems through precise control of low-temperature states [1,2,3]. The predominant technologies include adsorption refrigeration, dilution refrigeration, and adiabatic demagnetization refrigeration (ADR) [4]. Among these, the first two technologies require the expensive and scarce isotope helium-3 (3He). Comparatively, ADR based on magnetocaloric effect (MCE) has attracted increasing attention due to its low cost, high efficiency, and ability to operate independently of gravity without the need for scarce 3He [5], which has become an important approach for achieving ultra-low temperatures [6].

To achieve efficient cooling in sub-Kelvin temperature ranges, magnetic refrigerants, as the key material of ADR, must exhibit a large magnetic entropy change (−ΔSM) and a sufficiently low magnetic ordering temperature [7]. Paramagnetic compounds are particularly suitable for such applications due to their large magnetic moments and intrinsically low ordering temperatures [1,2]. Currently, anhydrous paramagnetic salts, such as GGG(Gd3Ga5O12) and GLF(GdLiF4), are frequently employed as magnetic refrigerants near 4 K because of their high magnetic moment density [8]. Hydrated paramagnetic salts, such as CPA (KCr(SO4)2·12H2O) and FAA (NH4Fe(SO4)2·12H2O), exhibit lower magnetic ordering temperatures due to the presence of water molecules in their crystal lattice. These hydrated salts are often used in the final stage of the ADR system to achieve extremely low temperatures of 10 mK and 30 mK, respectively [9,10].

Another representative compound, Mn(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O (MAS), has garnered attention as a low-temperature magnetic refrigerant because of its substantial theoretical entropy change, reaching Rln(6) [11]. However, the phase transition temperature of MAS (175 mK) [12] is considerably higher than those of CPA (10 mK) [9] and FAA (30 mK) [10], which prevents it from achieving lower temperatures. In recent years, Co2+-based compounds have been regarded as promising candidates for low-temperature magnetic refrigeration. For example, the maximum magnetic entropy change (−ΔSM) of La2Co3(NO3)12·24H2O (LCoN) reaches 9.45 J·kg−1·K−1 at 4 K and μ0ΔH = 7T. This compound exhibits weak antiferromagnetic interactions and a low magnetic ordering temperature [13]. Other Co2+-containing compounds, such as CoCl2 [14] and CoSO4·7H2O [15], have also demonstrated MCE performance. If Mn2+ ions in MAS are substituted by Co2+ ions, potential refrigerants with improved performance may be obtained. This motivates further exploration of hydrated Co2+-based paramagnetic salts as magnetic refrigerants. In this work, Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O crystal was grown and its magnetocaloric properties were investigated.

2. Experiment

2.1. Crystal Growth

Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O single crystal was obtained through slow evaporation. A total of 7.56 g (30 mmol) Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 7.93 g (60 mmol) (NH4)2SO4 with purity of 99.9% were weighed and dissolved in a clean 250 mL glass beaker using 150 mL deionized water to prepare a 0.2 mol/L solution. The solution was stirred at a constant temperature of 60 °C in a water bath for 1 h to ensure complete reaction, resulting in a purple–red, clear, and transparent solution. The beaker was placed on an evaporating dish to allow for slow evaporation of the solvent at room temperature, leading to the formation of abundant crystals. The small and well-shaped single crystals without visible defects were selected as seed crystals. The seed crystal was placed at the bottom of a clean 150 mL glass beaker containing the above solution. The beaker was then sealed with a layer of parafilm, and approximately 20 evenly distributed small holes were pierced in the parafilm using a needle with a diameter of 1 mm. The solvent was allowed to evaporate slowly at room temperature, ultimately yielding a large size (20 × 15 × 9.5 mm3) single crystal, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Photograph of a Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O single crystal.

2.2. Characterization

The powder X-ray diffraction analysis of the single crystal was performed at room temperature using a Bruker D8 X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) over the range 10° ≤ 2θ ≤ 70°. The step size and scan rate were 0.02° and 0.1 °/step, respectively.

A transparent single crystal was selected and ground into a 14.24 mg powder sample for magnetic measurements. A superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer was employed to perform zero-field cooling (ZFC), field cooling (FC), and isothermal magnetization (M(μ0H)) measurements. The M(T) curves were measured at a sweep rate of 1 K/min in the temperature range 2–300 K, while the M(μ0H) curves were recorded from 0 to 9 T in the temperature range 2–10 K.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structure

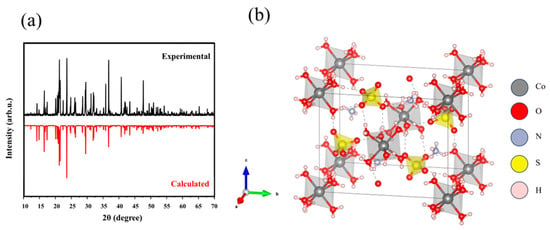

Figure 2a shows the experimental and calculated XRD patterns of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O crystal. The experimental results are in good agreement with the reference pattern (ICSD No. 14347). Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c. Rietveld refinement of the powder XRD data was performed using the GSAS-II software version 5.4.6, and the relevant parameters are listed in Table 1. The compound shares the same structure as Mn(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O (MAS), belonging to the Tutton salt family with the general formula [MI2MII(SO4)2·6H2O]. In its structure, Co2+ and NH4+ ions occupy distinct lattice sites and are linked to sulfate groups and water molecules through ionic and hydrogen bonding. Each Co2+ ion is surrounded by six H2O molecules to form [Co(H2O)6]2+ octahedra, while NH4+ groups share oxygen atoms with sulfate tetrahedra, providing interlayer connections. Within the unit cell, SO42− anions form a three-dimensional hydrogen-bond network with Co2+ ions and water molecules through oxygen atoms [16,17]. The distance between magnetic Co2+ ions is 6.23 Å, which is shorter than that of Mn2+ ions (6.26 Å) in MAS.

Figure 2.

(a) Experiment and calculated XRD patterns of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O at room temperature. (b) Unit cell of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O. a, b, and c denote the crystallographic lattice vectors (unit-cell axes): a (red), b (green), and c (blue).

Table 1.

Crystallographic data of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O obtained by powder diffraction, where Z is the number of chemical formulas in a unit cell, is the density, and R is the residual factor.

Structurally, Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O is isomorphous with other M2+ Tutton salts (M = Mn, Fe, Ni, and Cu), all crystallizing in the monoclinic P21/c (or equivalent P21/a) symmetry with similar hydrogen-bonding frameworks [18]. The thermal decomposition and dehydration behavior of this class of salts, including the cobalt analogue, have been investigated previously by thermogravimetric analysis [19,20]. Figure 2b illustrates the structure of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O.

3.2. Magnetic Measurements

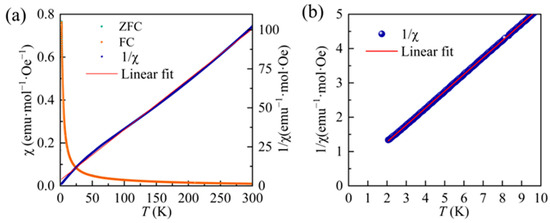

The temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility (χ) of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O was measured under zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) protocols in the range of 2–300 K with an external field of μ0H = 1 T, as shown in Figure 3a. The complete overlap of the ZFC and FC curves demonstrates negligible thermal hysteresis, and no clear signatures of magnetic phase transitions are detected within this temperature interval, confirming the paramagnetic nature of the compound. To further elucidate the magnetic ground state, the inverse susceptibility χ−1(T) was analyzed according to the Curie–Weiss law,

where C is the Curie constant, and is the Curie–Weiss temperature. The effective magnetic moment was derived from the fitted Curie constant using the following:

with C in emu·K·mol−1 and in Bohr magnetons (). A linear fit in the low-temperature region (2–10 K), shown in Figure 3b, yields a Curie–Weiss temperature of = −0.60 K, indicative of weak antiferromagnetic interactions. The Curie constant obtained from the fit is C = 2.03 emu·K·mol−1, from which the effective magnetic moment is calculated as . This value slightly exceeds the theoretical spin-only moment of 3.87 expected for a high-spin Co2+ ion with a electronic configuration (n = 3 unpaired electrons, ). Such an enhancement is commonly attributed to the residual orbital angular momentum that is only partially quenched by the octahedral crystal field. Similar behavior has been observed in other Co2+ systems, where values exceed the spin-only prediction due to unquenched orbital contributions and spin–orbit coupling effects [21].

Figure 3.

(a) The temperature dependent magnetic susceptibility (χ-T) for Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O. The blue curve reveals the inverse magnetic susceptibility (χ−1) and the red one is the linear fitting line of experimental data. (b) Zoom of inverse magnetic susceptibility near T = 0 K.

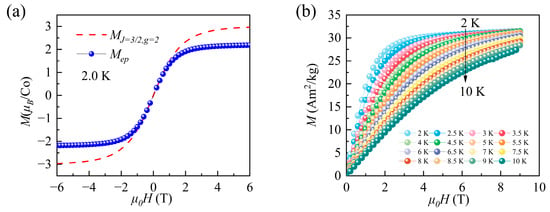

The dashed line in Figure 4a represents the theoretical M(H) curve at 2.0 K, calculated using the Brillouin function. At this temperature, the saturation magnetic moment of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O is 2.23μB per Co2+ ion, corresponding to 74.3% of the theoretical value of 3 μB expected for a system of non-interacting Co2+ ions with J = 3/2 and g = 2. The reduction relative to the ideal paramagnetic value can be ascribed either to the presence of a small fraction of non-magnetic impurities or to net antiferromagnetic interactions among Co2+ ions. Figure 4b shows the isothermal magnetization curves M(H) recorded between 2 and 10 K under applied fields up to 9 T. At 2.0 K, the magnetization increases continuously and approaches saturation at around 4 T, suggesting the existence of weak magnetic coupling in the system. With an increasing temperature above 8.5 K, the M(H) curves become nearly linear, reflecting that thermal fluctuations dominate and the applied field is insufficient to fully align the magnetic moments [22].

Figure 4.

(a) The magnetization versus applied field at 2.0K. (b) Isothermal M-μ0H curves of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O crystal.

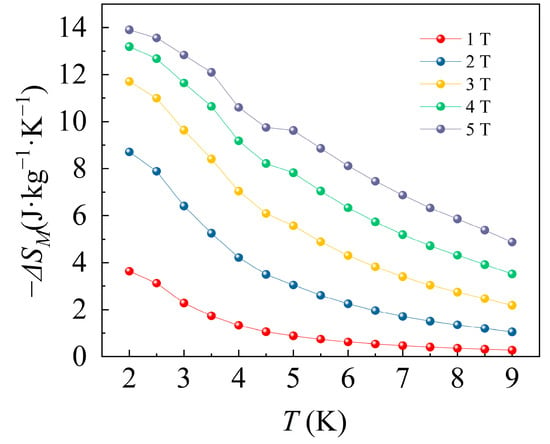

The magnetocaloric effect (MCE) of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O is characterized by the magnetic entropy change (−ΔSM), calculated from isothermal magnetization curves using the Maxwell equation.

Figure 5 presents the −ΔSM −T curves for selected ΔH values. As the temperature decreases, −ΔSM gradually increases, reaching a maximum value of −ΔSM = 13.90 J kg−1 K−1 at T = 2 K and μ0ΔH = 5 T. For paramagnetic systems containing Co2+ ions, the theoretical maximum entropy change () can be determined by the formula:

where is the number of magnetic ions, is the gas constant, and is the angular momentum quantum number. For Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O, the theoretical upper limit is 14.58 J kg−1 K−1, and the experimental −ΔSM value achieves 95% of this theoretical maximum. The discrepancy between the experimental and theoretical values may be attributed to the presence of AFM coupling. Furthermore, Figure 5 indicates that the −ΔSM value shows relatively small variation with temperature under a fixed magnetic field, suggesting that the magnetic refrigeration system based on Co2+ ions has abroad operational temperature ranges. From Table 2, the maximum magnetic entropy change of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O is higher than that of CoCl2, CoSO4·7H2O, and LCoN, exhibiting potential application prospect.

Figure 5.

−ΔSM(T) curves for different magnetic field changes μ0ΔH.

Table 2.

Comparison of the relevant parameters for Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O with the abovementioned hydrated salts, where Tt is the temperature at which the maximum magnetic entropy change is achieved during the experimental process, and is the maximum magnetic entropy change. Data compiled from Refs. [12,13,14].

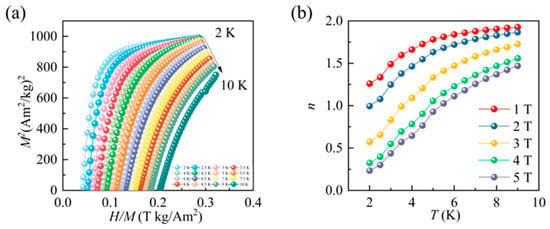

Belov–Arrott plots and the field exponent n are widely employed to determine the order of magnetic phase transitions. Figure 6a presents the Belov–Arrott curves obtained from the M2-H/M relations in the temperature range of 2–10 K. None of the curves intersect the origin, indicating that the critical temperature lies outside the investigated window, and, thus, no phase transition occurs within the measured range. According to Banerjee’s criterion [24], all the curves exhibit positive slopes, suggesting that if a transition occurs at lower or higher temperatures, it should be of second-order character. In addition, Law [25] proposed another method to determine the type of magnetic phase transition, which is to calculate the field exponent n to determine the order of the magnetic phase transition. Figure 6b illustrates the distribution of the exponent n in the temperature range of 2–9 K. The magnetic entropy change (ΔSM) as a function of the applied magnetic field (H) can be described by a power-law relation:

where the exponent n is a parameter that depends on both temperature and magnetic field. Its calculation formula is given by the following:

Figure 6.

(a) The Belov–Arrott plot of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O. (b) The n-T curves of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O at different magnetic field changes.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the temperature dependence of n provides a quantitative criterion for identifying the type of magnetic phase transition. For a second-order phase transition (SOPT), n approaches one well below the Curie temperature and tends toward two well above it. As shown in Figure 6b, the maximum value of n remains below two across the entire investigated temperature range, and no overshoot beyond this threshold is observed. This behavior is consistent with the scenario expected for a second-order transition, suggesting that although no critical point is reached within the measured 2–9 K window, the eventual transition of Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O should be of second-order character. Compared with FOPT materials, SOPT materials generally exhibit smaller thermal hysteresis, which enhances the stability of the refrigeration cycle and allows for a broader operating-temperature range [26].

4. Conclusions

In summary, a Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O single crystal with the size of 20 × 15 × 9.5 mm3 was successfully grown by the slow evaporation method at room temperature. Magnetic susceptibility measurements revealed that Co(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O exhibits paramagnetic behavior within the measured temperature range, and the fitted Curie–Weiss temperature was = −0.60 K, indicating weak antiferromagnetic (AFM) interactions among the magnetic ions in this compound at low temperatures. The maximum magnetic entropy change was 13.90 J kg−1 K−1 at 2 K and 5 T, which is close to the theoretical prediction of 14.58 J kg−1 K−1 and exceeds those reported for CMN and LCoN under similar conditions. Additionally, the smooth temperature dependence of −ΔSM suggests a broad operational temperature window for magnetic refrigeration, thereby enhancing its application potential. This work indicates that the Co2+-based compounds may be promising candidates for low-temperature magnetic refrigeration.

Author Contributions

Software, Z.L.; Validation, T.W. and Z.C.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Investigation, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, G.Z.; Project administration, H.T.; Funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by by the National Key Research and Development Program of China grant number 2022YFB3505102.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shen, J.; Mo, Z.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Sun, H.; Xie, H.; Liu, R. Development of magnetic refrigeration materials and technology. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 2021, 51, 067502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shen, J.; Hu, F.; Sun, J.; Shen, B. Research progress in magnetocaloric effect materials. Acta Phys. Sin. 2016, 65, 217502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, M.H.; Purcell, E.M. A Theoretical Study of Magnetic Cooling Experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 1937, 5, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessoli, R. Chilling with Magnetic Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, H.; Li, X.; Yu, N.; Pan, M.; Yu, Y.; Fang, J.; Hu, X.; Ge, H.; et al. Review of the research on oxides in low-temperature magnetic refrigeration. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 6665–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, H.; Liu, S. Research Progress of High Efficiency Magnetic Refrigeration Technology and Magnetic Materials. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2025, 38, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gimaev, R.; Kovalev, B.; Kamilov, K.; Zverev, V.; Tishin, A. Review on the materials and devices for magnetic refrigeration in the temperature range of nitrogen and hydrogen liquefaction. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2019, 558, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numazawa, T.; Kamiya, K.; Shirron, P.; DiPirro, M.; Matsumoto, K. Magnetocaloric Effect of Polycrystal GdLiF4 for Adiabatic Magnetic Refrigeration. AIP Conf. Proc. 2006, 850, 1579–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, J.M.; Kurti, N.; Simon, F.E. The thermal and magnetic properties of chromium potassium alum below 0·1 °K. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1954, 221, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Vilches, O.E.; Wheatley, J.C. Measurements of the Specific Heats of Three Magnetic Salts at Low Temperatures. Phys. Rev. 1966, 148, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.J.; Clark, J.T.; Cesarano, J. Magnetic and thermodynamic properties of Mn(NH4)2(SO4)2⋅6H2O below 1 °K and at fields up to 24,000 G parallel to the b axis. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 62, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuru, K.; Uryû, N. Spin Reorientation in Manganese Tutton Salt Mn(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 40, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wu, L.; Zhang, G.; Tu, H.; Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Wang, D. Large cryogenic magnetocaloric effect in transition metal-based double dinitrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 262403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Liu, W.; Guo, S.; Gong, W.J.; Lv, X.K.; Zhang, Z.D. Field-induced reversible magnetocaloric effect in CoCl2. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 507, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Giauque, W.F.; Hornung, E.W.; Fisher, R.A.; Brodale, G.E. The Measurement of Magnetic Induction in High Magnetic Fields at Low Temperatures. CoSO4·7H2O. J. Chem. Phys. 1962, 37, 2952–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Neto, J.G.; Viana, J.R.; Abreu, K.R.; da Silva, L.F.L.; Lage, M.R.; Stoyanov, S.R.; de Sousa, F.F.; Lang, R.; Dos Santos, A.O. Tutton salt (NH4)2Zn(SO4)2(H2O)6: Thermostructural, spectroscopic, Hirshfeld surface, and DFT investigations. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fender, B.E.F.; Figgis, B.N.; Forsyth, J.B.; Mason, R. Spin density and bonding in Mn(H2O)2+6 in ammonium manganese Tutton salt. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1986, 404, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, H.; Morosin, B.; Natt, J.J.; Witkowska, A.M.; Lingafelter, E.C. The Crystal Structure of Tutton’s Salts. VI. Vanadium (II), Iron (II) and Cobalt (II) Ammonium Sulfate Hexahydrates. Acta Crystallogr. 1967, 22, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, V.T.; Hacaloglu, J. Thermal Behaviour and Kinetic Analysis of the Thermogravi-metric Data of Double Ammonium Sulphate Hexahydrate Salts of Mn (II), Fe (II), Co (II), Ni (II) and Cu (II). Thermochim. Acta 1994, 236, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Manomenova, V.L.; Nikolaeva, N.V.; Shlyapnikova, E.A.; Buchneva, O.N.; Kovaleva, I.Y.; Kruchinin, S.E. The Ammonium Cobalt Sulfate Hexahydrate (ACSH) Crystal Growth from Aqueous Solutions and Some Properties of Solutions and Crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 2020, 533, 125463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, Y.M.; Cava, R.J. The Effective Magnetic Moments of Co2+ and Co3+ in SrTiO3 Investigated by Temperature-Dependent Magnetic Susceptibility. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 122, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaker, S.F. Investigation of Nuclear Effects in Paramagnetic Single Crystals at Very Low Temperatures. Phys. Rev. 1951, 84, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Hornung, E.W.; Brodale, G.E.; Giauque, W.F. Magnetothermodynamics of Ce2Mg3(NO3)12·24H2O. II. The evaluation of absolute temperature and other thermodynamic properties of CMN to 0.6 m °K. J. Chem. Phys. 1973, 58, 5584–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebenin, N.G.; Zainullina, R.I.; Ustinov, V.V.; Mukovskii, Y.M. Magnetic properties of La0.7−xPrxCa0.3MnO3 single crystals: When is Banerjee criterion applicable? J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 354, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.Y.; Franco, V.; Moreno-Ramírez, L.M.; Conde, A.; Karpenkov, D.Y.; Radulov, I.; Skokov, K.P.; Gutfleisch, O. A quantitative criterion for determining the order of magnetic phase transitions using the magnetocaloric effect. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutfleisch, O.; Gottschall, T.; Fries, M.; Benke, D.; Radulov, I.; Skokov, K.P.; Wende, H.; Gruner, M.; Acet, M.; Entel, P.; et al. Mastering hysteresis in magnetocaloric materials. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2015, 374, 20150308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).