Enhancing Light Absorption in Perovskite Solar Cells Using Au@Al2O3 Core–Shell Nanostructures: An FDTD Simulation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

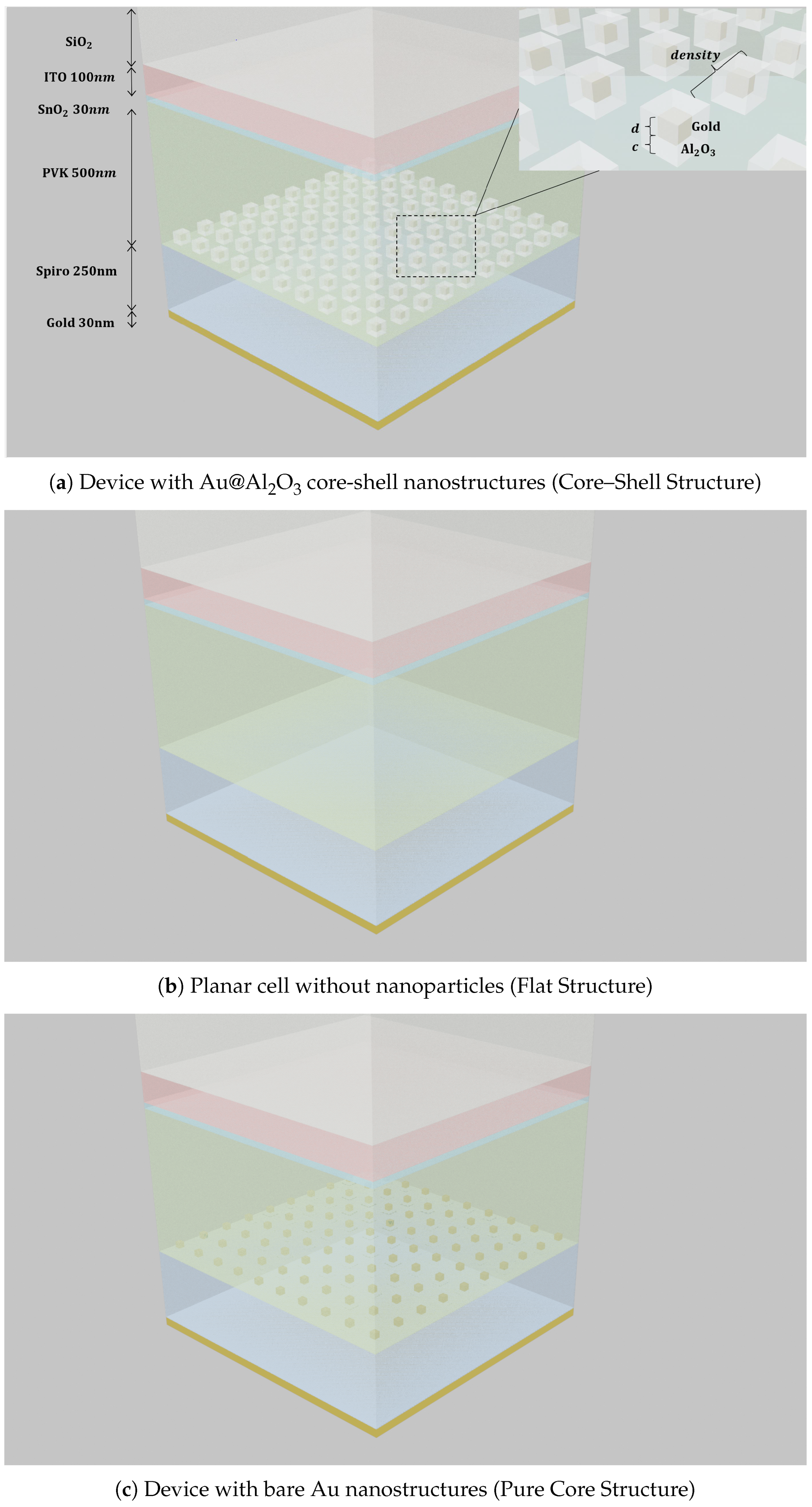

2. Simulation Methodology and Device Structure

2.1. Theoretical Framework of the FDTD Method

2.2. FDTD Simulation Implementation

2.3. Operational Settings and Data Acquisition for the FDTD Simulations

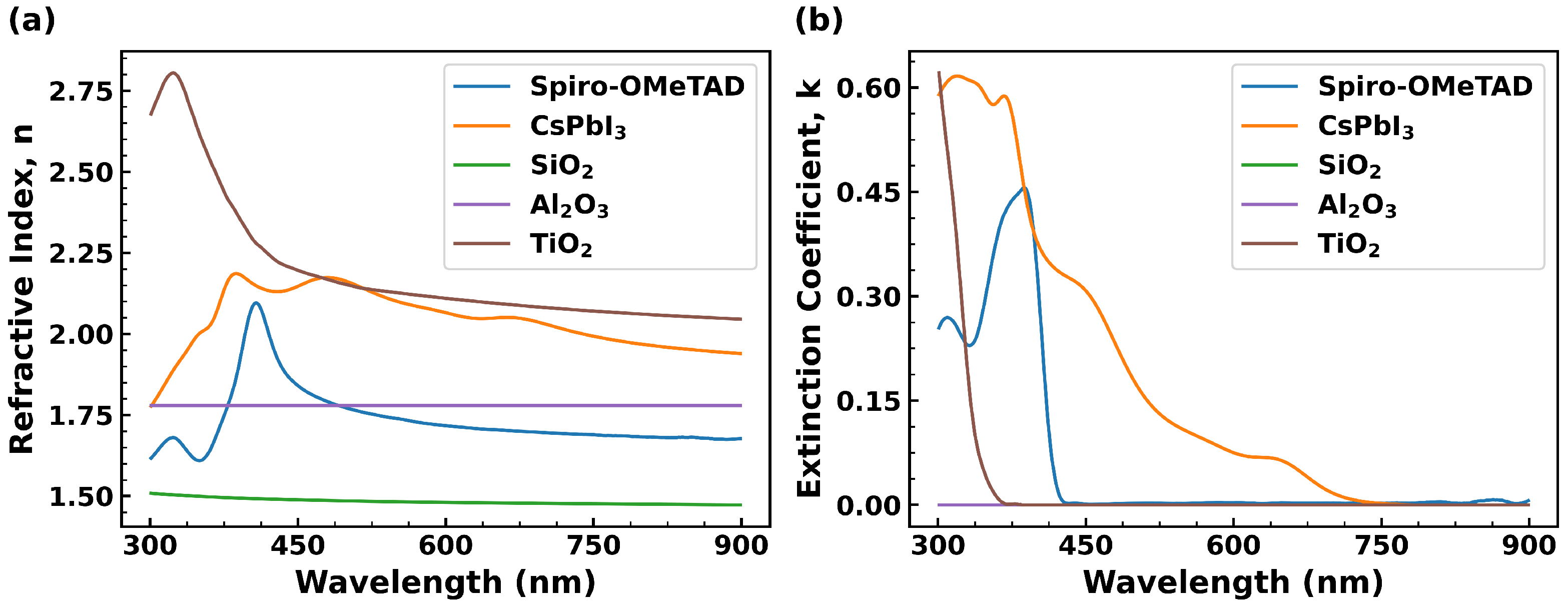

2.4. Geometrical Model and Optical Constants

2.5. Front- Versus Back-Interface Placement: Quantitative Control and Design Rationale

2.6. Simulation Parameters and Data Calculation

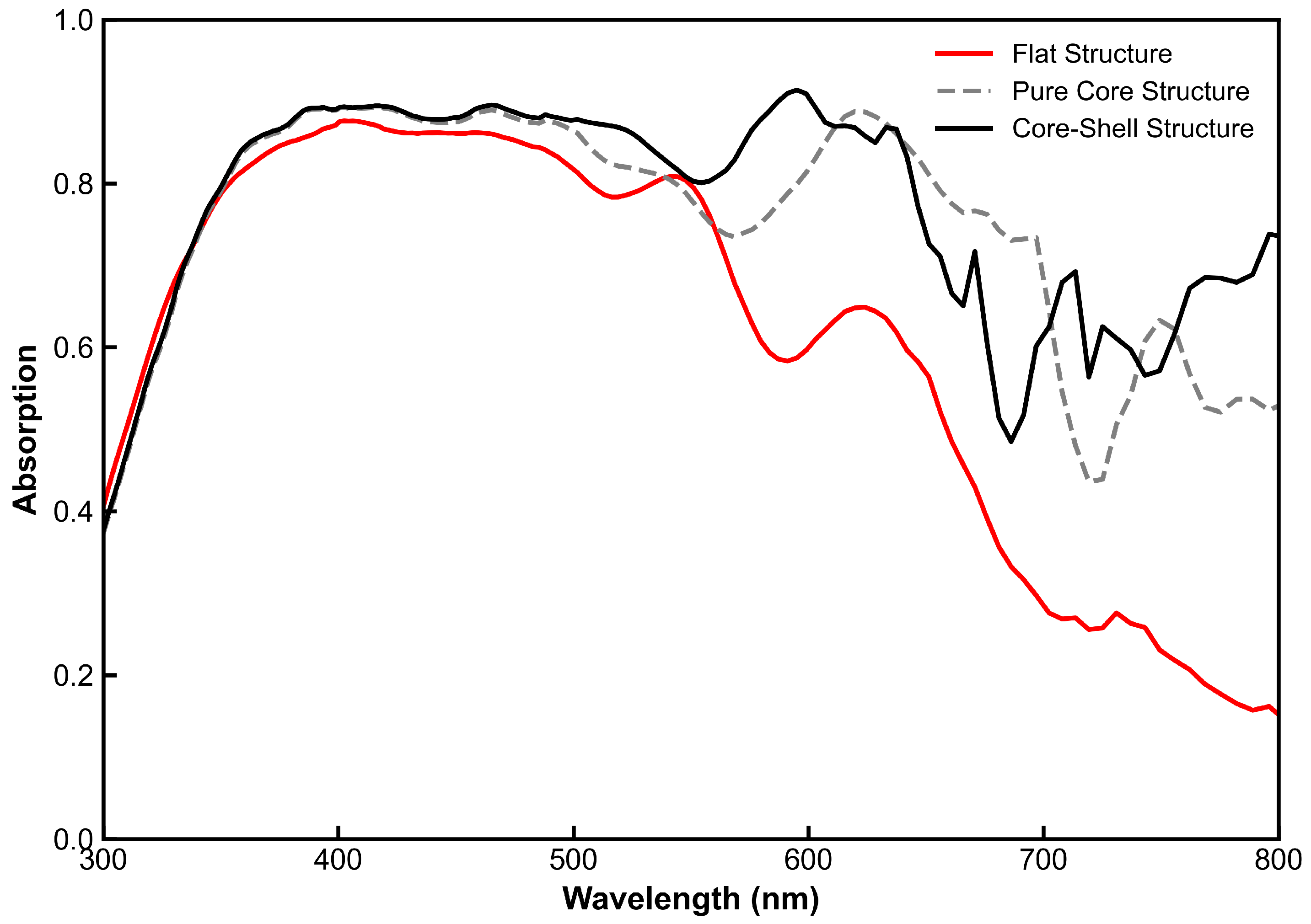

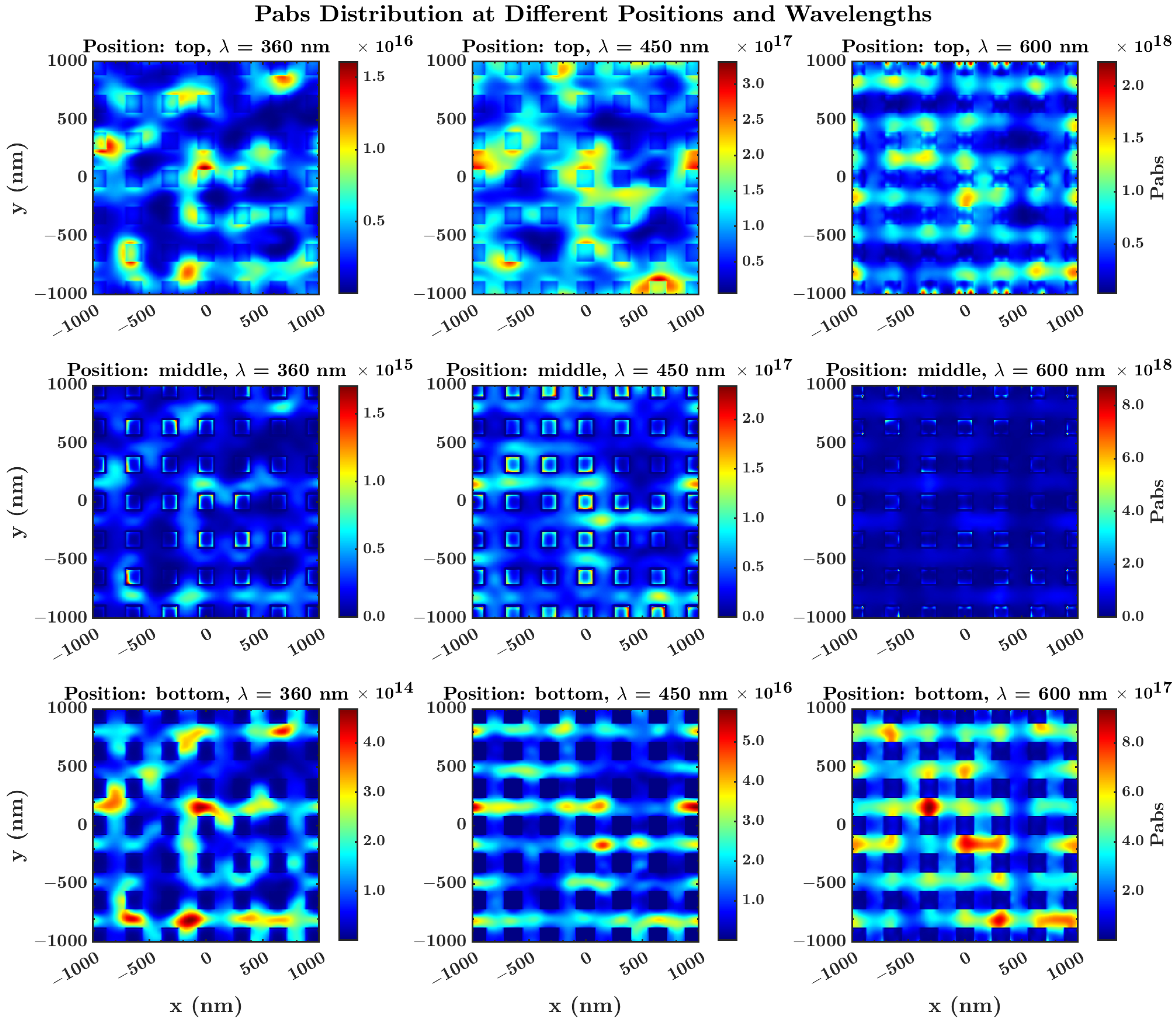

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optical Properties and the Dual-Function Role of the Al2O3 Shell

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Shell Materials for Optimal LSPR Tuning and Stability

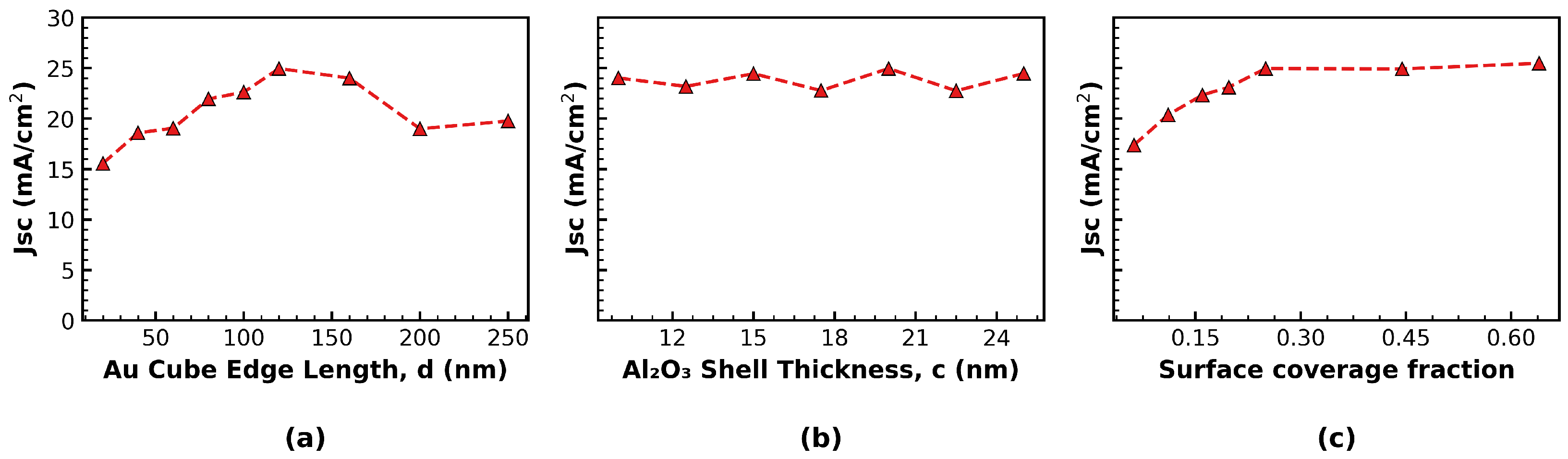

3.3. Optimization of Nanostructure Geometry

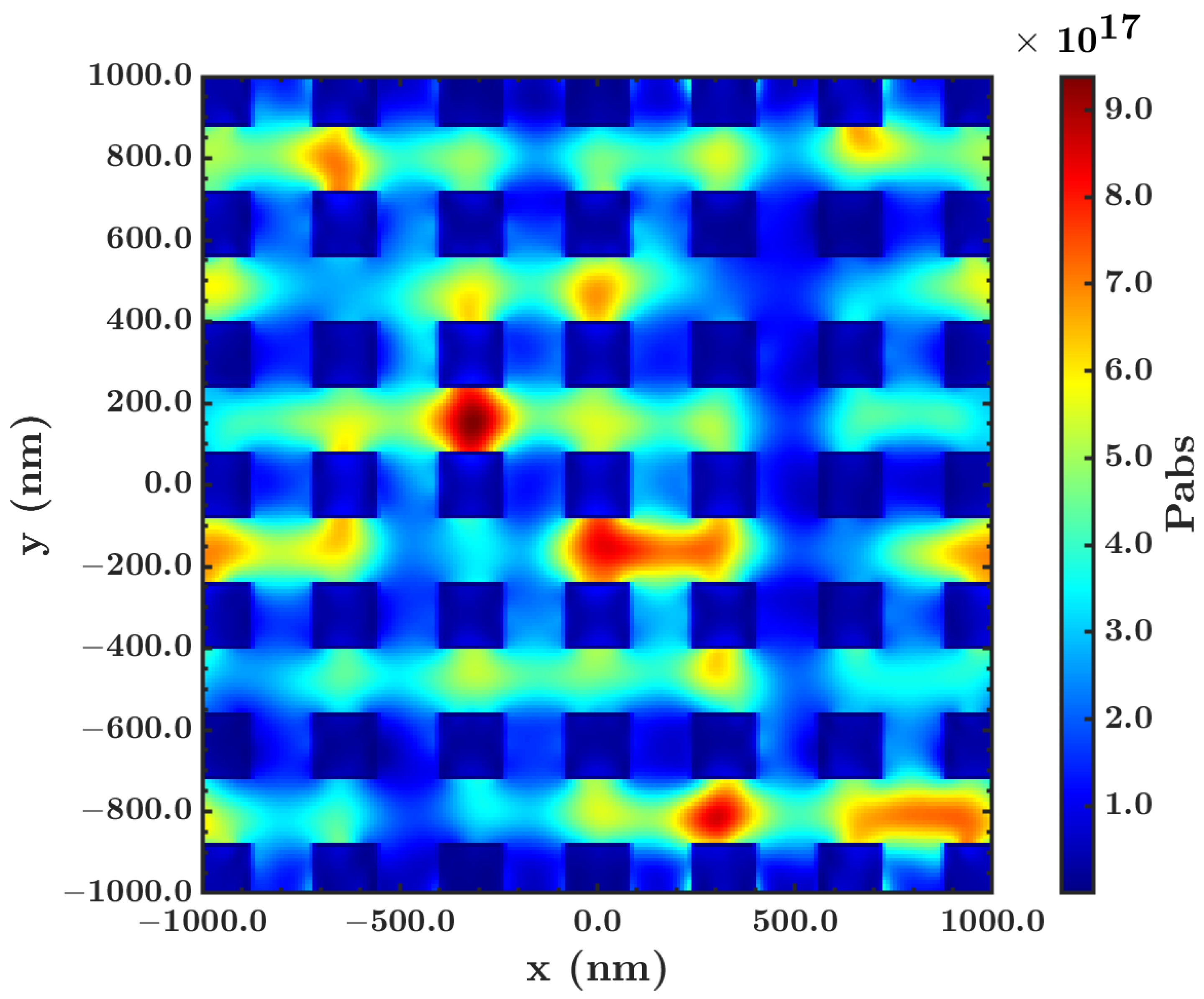

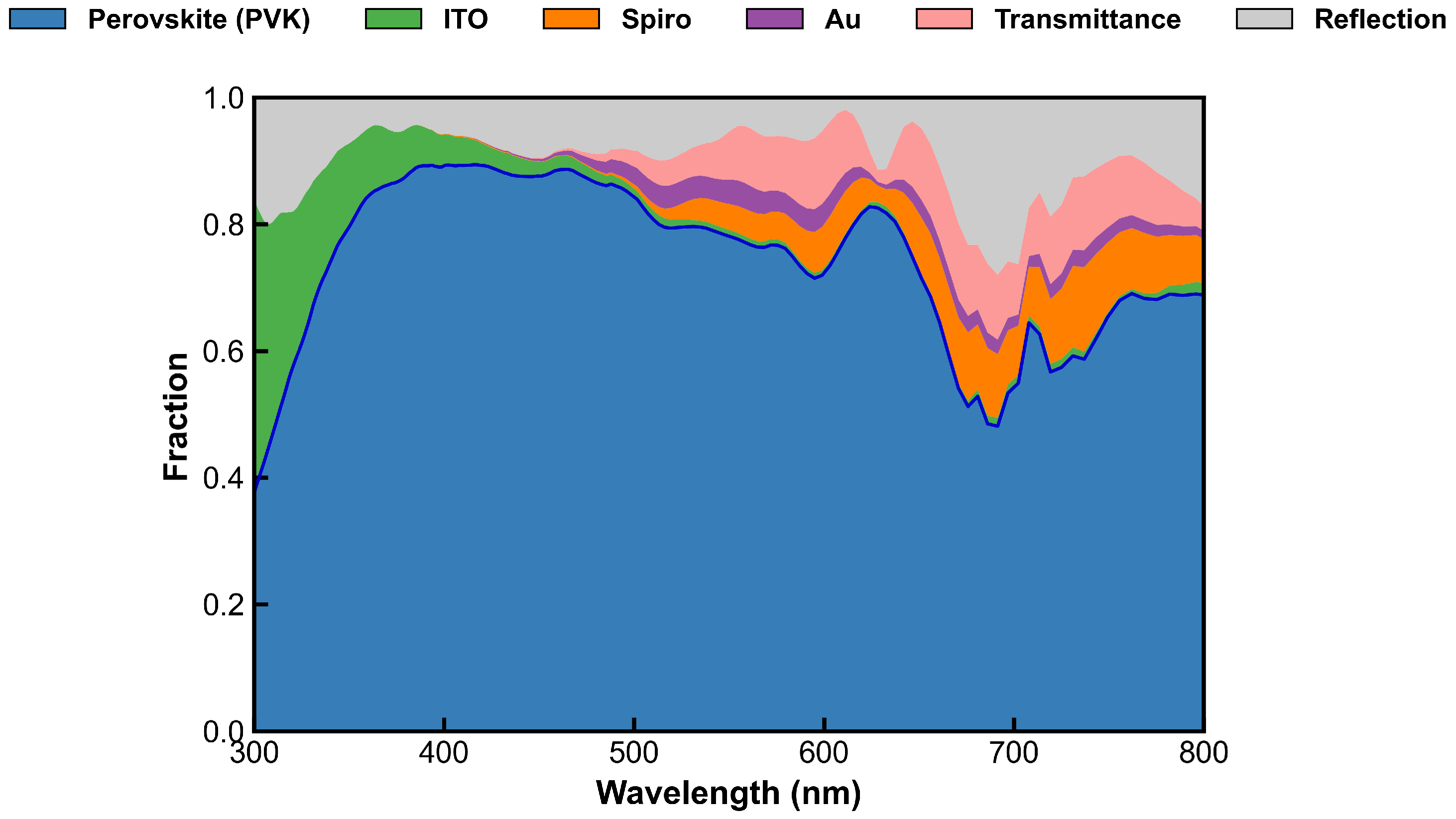

3.4. Impact on Device Performance and Energy Distribution

3.5. From Optical Behavior to Design Rules and a Testable Parameter Window

3.5.1. Design Rules Distilled from the Simulations

- (i)

- (ii)

- Packing fraction. Use an intermediate surface coverage so that useful scattering and near-field localization are maintained while near-field overlap and metal loss remain bounded; the present scans indicate an optimum near , consistent with trends observed for plasmonic light management in photovoltaics [2].

- (iii)

- Core size. Select a core dimension that provides the targeted LSPR placement without excessive linewidth broadening; within the explored parameter space, Au cubes near nm meet this condition.

- (iv)

3.5.2. Operational Window and Testable Predictions

3.6. Model-Based Scenarios and Observable Signatures

3.7. Comparative Discussion with Representative Simulation Studies

3.8. Implications and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Luo, B.; Shi, X.; Shen, X. Plasmonics Meets Perovskite Photovoltaics: Innovations and Challenges in Boosting Efficiency. Molecules 2024, 29, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, H.A.; Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; Bartoli, F.J.; Kafafi, Z.H. Plasmonic-Enhanced Organic Photovoltaics: Breaking the 10% Efficiency Barrier. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2385–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Xiong, Q.; Deng, L.; Zhou, Q.; Meng, L.; Du, Y.; Zuo, T.; et al. Plasmon-Enhanced Perovskite Solar Cells with Efficiency Beyond 21%: The Asynchronous Synergistic Effect of Water and Gold Nanorods. ChemPlusChem 2021, 86, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, F.; Wu, Y.; Shi, B.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Xu, F.; Jia, J.; Wei, H.; Yang, T.; Cao, B. Plasmonic Au Nanooctahedrons Enhance Light Harvesting and Photocarrier Extraction in Perovskite Solar Cell. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 3201–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, G.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H. Tailored Au@TiO2 nanostructures for the plasmonic effect in planar perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 12034–12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.K.; Chander, N.; Komarala, V.K.; Sharma, R.P. Plasmonic Perovskite Solar Cells Utilizing Au@SiO2 Core-Shell Nanoparticles. Plasmonics 2017, 12, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushik, D.; Verhees, W.J.H.; Kuang, Y.; Veenstra, S.; Zhang, D.; Verheijen, M.A.; Creatore, M.; Schropp, R.E.I. High-efficiency humidity-stable planar perovskite solar cells based on atomic layer architecture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, S.; Xiong, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Xing, G.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.; et al. Surface passivation of organometal halide perovskites by atomic layer deposition: An investigation of the mechanism of efficient inverted planar solar cells. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 2305–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y.; Li, Z.; Pang, S. UV degradation of the interface between perovskites and the electron transport layer. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11551–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Xie, J.; Gao, P. Ultraviolet Photocatalytic Degradation of Perovskite Solar Cells: Progress, Challenges, and Strategies. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2022, 3, 2100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangjoy, A.; Matloub, S. Theoretical study of Ag and Au triple core-shell spherical plasmonic nanoparticles in ultra-thin film perovskite solar cells. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 19102–19115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebi, H.; Rafiei Rad, R.; Emami, F. Synergistic effects of SiO2 and Au nanostructures for enhanced broadband light absorption in perovskite solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Che, Y.; Duan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S.; Xu, D.; Fang, Z.; Lei, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.F. 21.15%-Efficiency and Stable γ-CsPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells Enabled by an Acyloin Ligand. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2210223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Fang, J.; Fan, Y.; Luo, T.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Tsetseris, L.; Anthopoulos, T.D.; Liu, S.F.; et al. Printable CsPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells with PCE of 19% via an Additive Strategy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taflove, A.; Hagness, S. Computational Electrodynamics: The Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method, 2nd ed.; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, K. Numerical solution of initial boundary value problems involving maxwell’s equations in isotropic media. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1966, 14, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Ruan, F.; Li, Z.; Ren, B.; Xu, H.; Tian, Z. FDTD for plasmonics: Applications in enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 2635–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangjoy, A.; Matloub, S. Optimizing Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Cells with Pyramidal Core-Shell Nanoparticles for High Efficiency. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumerical. Solar Cell Methodology. Ansys Lumerical Knowledge Base, 2024. Available online: https://optics.ansys.com/hc/en-us/articles/360042165634 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Rassinfosse, L.; Müller, J.; Deparis, O.; Smeets, S.; Rosolen, G.; Lucas, S. Convergence and accuracy of FDTD modelling for periodic plasmonic systems. Opt. Contin. 2024, 3, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesina, A.C.; Vaccari, A.; Berini, P.; Ramunno, L. On the convergence and accuracy of the FDTD method for nanoplasmonics. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 10481–10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jiang, X.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Fu, N. Plasmonic perovskite solar cells: An overview from metal particle structure to device design. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 25, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palik, E.D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, J.M.; Stranks, S.D.; Hörantner, M.T.; Hüttner, S.; Zhang, W.; Crossland, E.J.W.; Ramirez, I.; Riede, M.; Johnston, M.B.; Friend, R.H.; et al. Optical properties and limiting photocurrent of thin-film perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60904-3:2019; Photovoltaic Devices—Part 3: Measurement Principles for Terrestrial Photovoltaic (PV) Solar Devices with Reference Spectral Irradiance Data. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- G173-03 (Reapproved 2020); Standard Tables for Reference Solar Spectral Irradiances: Direct Normal and Hemispherical on 37° Tilted Surface. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Reference Air Mass 1.5 Spectra; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2025.

- Afzal, A.; Habib, A.; Ulhasan, I.; Shahid, M.; Rehman, A. Antireflective Self-Cleaning TiO2 Coatings for Solar Energy Harvesting Applications. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 687059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.; Hoang, T.B.; McGuire, F.; Mock, J.J.; Ciracì, C.; Smith, D.R.; Mikkelsen, M.H. Control of Radiative Processes Using Tunable Plasmonic Nanopatch Antennas. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 4797–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y.; Ren, C.; Song, J. Efficiency enhancement of perovskite solar cells based on Al2O3-passivated nano-nickel oxide film. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 13881–13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Gutiérrez Álvarez, S.; Meng, J.; Zheng, K.; Sá, J. Role of the Metal Oxide Electron Acceptor on Gold–Plasmon Hot-Carrier Dynamics and Its Implication to Photocatalysis and Photovoltaics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, M.; Leng, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.x.; Wang, W.; Zhou, L.; Huang, H.; et al. Plasmonic Metal Nanoparticles with Core–Bishell Structure for High-Performance Organic and Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5397–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycenga, M.; Xia, X.; Moran, C.H.; Zhou, F.; Qin, D.; Li, Z.Y.; Xia, Y. Generation of Hot Spots with Silver Nanocubes for Single-Molecule Detection by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5473–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křápek, V.; Konečná, A.; Ligmajer, F.; Dvořák, P.; Křápek, F.; Šikola, T.; Bšonka, M. Plasmonic lightning-rod effect. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.09454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbieta, M.; Barbry, M.; Zhang, Y.; Koval, P.; Sánchez-Portal, D.; Zabala, N.; Aizpurua, J. Atomic-Scale Lightning Rod Effect in Plasmonic Picocavities: A Classical View to a Quantum Effect. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.; Carretero Palacios, S.; Anaya, M. Synergetic Near- and Far-Field Plasmonic Effects for Optimal All-Perovskite Tandem Solar Cells with Maximized Infrared Absorption. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 2632–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- nanoComposix. Gold Nanoparticles: Optical Properties (Effect of Local Refractive Index). 2024. Available online: https://nanocomposix.com/pages/gold-nanoparticles-optical-properties (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Miah, M.H.; Rahman, M.B.; Nur-E-Alam, M.; Islam, M.A.; Shahinuzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.R.; Ullah, M.H.; Khandaker, M.U. Key degradation mechanisms of perovskite solar cells and strategies for enhanced stability: Issues and prospects. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 628–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero-Palacios, S.; Jiménez-Solano, A.; Míguez, H. Plasmonic Nanoparticles as Light-Harvesting Enhancers in Perovskite Solar Cells: A User’s Guide. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, H.; Wittenberg, N.J.; Lindquist, N.C.; Oh, S.H. Atomic layer deposition: A versatile technique for plasmonics and nanobiotechnology. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 27, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Peng, W.; Mao, K.; Cai, F.; Meng, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, T.; Yuan, S.; Xu, Z.; Feng, X.; et al. Reducing nonradiative recombination in perovskite solar cells with a porous insulator contact. Science 2023, 379, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Yang, J.; Shen, X. Modeling the performance of perovskite solar cells with inserting porous insulating alumina nanoplates. Chin. Phys. B 2024, 33, 038501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivriq, S.B.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Davidsen, R.S. Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency in Half-Tandem MAPbI3/ MASnI3 Perovskite solar cells with triple core-shell plasmonic nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babicheva, V.E.; Evlyukhin, A.B. Interplay and coupling of electric and magnetic multipole resonances in plasmonic nanoparticle lattices. MRS Commun. 2018, 8, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrakis, G.; Kakavelakis, G.; Tasolamprou, A.C.; Alharbi, E.A.; Petridis, K.; Kenanakis, G.; Kafesaki, M. Plasmonic Nanoparticles’ Impact on Perovskite–Perovskite Tandem Solar Cells’ Thickness and Weight. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 8954–8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushik, D.; Hazendonk, L.; Zardetto, V.; Vandalon, V.; Verheijen, M.A.; Kessels, W.M.; Creatore, M. Chemical Analysis of the Interface between Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Perovskite and Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 5526–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmany, S.; Etgar, L. Semitransparent Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarillo Abad, E.; Joyce, H.J.; Hirst, L.C. Light management for ever-thinner photovoltaics: A tutorial review. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 011101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, B.; Fan, Z.; Wong, Z.J. Plasmonic–perovskite solar cells, light emitters, and sensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scenario | Simulation Outputs | Expected Spectral Signature |

|---|---|---|

| Semitransparent (BIPV concept) | for AVT; | AVT preserved at fixed thickness; red/NIR rise of near the tuned LSPR. |

| Ultrathin opaque | ; via Equation (5) under AM1.5G | Upper-bound from AM1.5G integration; bounded Au loss. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Li, C. Enhancing Light Absorption in Perovskite Solar Cells Using Au@Al2O3 Core–Shell Nanostructures: An FDTD Simulation Study. Crystals 2025, 15, 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121023

Jiang Y, Li C. Enhancing Light Absorption in Perovskite Solar Cells Using Au@Al2O3 Core–Shell Nanostructures: An FDTD Simulation Study. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121023

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yunwei, and Congyi Li. 2025. "Enhancing Light Absorption in Perovskite Solar Cells Using Au@Al2O3 Core–Shell Nanostructures: An FDTD Simulation Study" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121023

APA StyleJiang, Y., & Li, C. (2025). Enhancing Light Absorption in Perovskite Solar Cells Using Au@Al2O3 Core–Shell Nanostructures: An FDTD Simulation Study. Crystals, 15(12), 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121023