Abstract

Aluminum nitride (AlN), diamond, and β-phase gallium oxide (β-Ga2O3) belong to the family of ultra-wide bandgap (UWBG) semiconductors and exhibit remarkable properties for future power and optoelectronic applications. Compared to conventional wide bandgap (WBG) materials such as silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN), they demonstrate clear advantages in terms of high-voltage, high-temperature, and high-frequency operation, as well as extremely high breakdown fields. In this work, numerical simulations are performed to evaluate and compare the radiative responses of AlN, diamond, and β-Ga2O3 when exposed to neutron irradiation covering the full atmospheric spectrum at sea level, from 1 meV to 10 GeV. The Geant4 simulation framework is used to model neutron interactions with the three materials, focusing on single-particle events that may be triggered. A detailed comparison is conducted, particularly concerning the generation of secondary charged particles and their distributions in energy, linear energy transfer (LET), and range given by SRIM. The contribution of the 14N(n,p)14C reaction in AlN is also specifically investigated. In addition, the study examines the consequences of these interactions in terms of electron-hole pair generation and charge deposition, and discusses the implications for the radiation sensitivity of these materials when exposed to atmospheric neutrons.

1. Introduction

Aluminum nitride (AlN), diamond and β-phase gallium oxide (β-Ga2O3) are ultra-wide bandgap (UWBG) semiconductors that are emerging as reference materials for a new generation of power and optoelectronic devices [1,2]. Their ultra-wide bandgaps—6.2 eV for AlN, 5.47 eV for diamond and approximately 4.8 eV for β-Ga2O3—enable them to operate at voltages, temperatures and frequencies that far exceed those of conventional wide bandgap (WBG) semiconductors, such as silicon carbide (SiC—bandgap of 3.2 eV) and gallium nitride (GaN—bandgap of 3.4 eV) [3,4,5]. Furthermore, these materials have remarkably high breakdown fields, reaching approximately 8 MV/cm for β-Ga2O3 and over 10 MV/cm for diamond—significantly higher than the values of SiC (2.5–2.8 MV/cm) and GaN (3.3 MV/cm) [6,7,8]. AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 have been extensively studied due to the availability of substrates for thin-film growth [9], the ability to reliably dope them, and the successful demonstration of functional devices [10,11,12,13,14]. Beyond their wide bandgap and high dielectric strength, each of these materials offers specific advantages that meet a variety of technological needs. For example, AlN is transparent in the deep ultraviolet, has excellent thermal conductivity and strong dielectric properties, and is therefore ideal for use in UV optoelectronics and radio frequency (RF) devices, as well as for GaN-based electronics substrates [15,16]. Diamond stands out for having very high thermal conductivity and remarkable electron mobility, as well as exceptional resistance to radiation. These qualities make it the semiconductor of choice for applications involving extreme power, very high frequencies and hostile environments [17,18,19]. Finally, β-Ga2O3 has the advantage of being able to produce large, high-quality substrates at low cost through melt growth. This opens up the possibility of efficiently scaling up high-voltage devices such as Schottky diodes and MOSFETs [3,5,20,21,22]. In summary, AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 associate ultra-wide bandgaps, high breakdown fields and complementary physical properties, which makes them particularly promising materials for applications where SiC and GaN reach their intrinsic limits, especially in deep ultraviolet optoelectronics and future power electronics.

The susceptibility of devices and circuits to radiation-induced failures has become a critical concern, particularly in the context of ongoing miniaturization of micro- and nanoelectronic technologies and their growing deployment in mission-critical applications, including aeronautics, automotive systems, and high-reliability communication networks. Among the radiation effects, single-event effects (SEEs) produced by atmospheric neutrons are of particular importance, as the interaction of secondary particles with semiconductor material can induce local charge generation, transient currents and, ultimately, logic errors or destructive failures [23,24,25]. While SiC- and GaN-based technologies have been extensively studied in this context [26,27,28], much less information exists on UWBG semiconductors, such as AlN, diamond, and β-Ga2O3. The dominant SEEs in WBG and especially UWBG devices are single-event burnout (SEB) and dielectric rupture. UWBG semiconductors are expected to offer greater radiation resistance, since radiation tolerance increases non-linearly with bandgap width [4]. However, several experimental studies show that UWBG diodes, particularly those made of β-Ga2O3, experience SEB at significantly lower voltages than their critical field suggests, even under low-energy ion irradiation [29,30]. Despite their high critical field, their poor thermal dissipation and induced current density result in radiation hardness comparable to that of silicon carbide (SiC) or gallium nitride (GaN) [31,32]. A simulation study of single-particle interaction mechanisms induced by atmospheric neutrons in UWBG materials is therefore an important first step to evaluate their radiation sensitivity and to determine whether their intrinsic properties can effectively translate into enhanced resilience against soft errors. Since there is still limited literature on the study of SEEs (caused by the impact of a single particle) on these materials and devices, the cumulative effects associated with atomic displacement under the action of numerous particles have been studied more extensively. This disparity is mainly due to the challenges related to the crystalline quality of UWBG materials and the constraints of their manufacturing processes [33]. These displacement effects, also known as “displacement damage”, can be caused by neutrons through interactions with the nuclei of the material. They can transfer sufficient energy to displace atoms from their lattice site, triggering a cascade of collisions and creating vacancies and interstitials within the crystal structure. These crystal defects locally alter the electronic properties of the material and can lead to a gradual degradation of device performance (e.g., increased leakage current or decreased carrier mobility). Therefore, the accumulation of this damage is a key factor in the long-term reliability of components exposed to neutron radiation [8,34,35].

Regarding SEEs, most studies focus on the effects of radiation in UWBG devices [27,36,37,38], but few address the mechanisms induced by single particles at the material level. Nevertheless, understanding the creation of single events in microelectronics requires focusing on the radiative response of a material. This includes the interaction of an incident particle with the target material, the transfer of energy through the transport of the particle through the target material, and the conversion of energy deposited by the particle into free charge, i.e., the creation of an electron-hole pair [39]. These three fundamental processes determine the formation of subsequent single events. This article studies and compares the radiative responses of the undoped semiconductor materials AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 to neutrons produced by cosmic rays in the atmosphere at ground level. The study focuses specifically on secondary ionizing particles resulting from neutron-semiconductor interactions and it particularly considers their ability to transfer energy within the materials under consideration and to generate electron-hole pairs. This latter mechanism is the source of parasitic current transients that can disrupt devices and circuits [40,41] and is at the origin of SEEs. This work therefore concerns the effects of single events (induced by a single particle) of atmospheric neutron interactions with the target material and does not address the issue of displacement effects (i.e., the cumulative effects of these interactions [42]). It is also important to note that, at ground level, muons are charged particles with an abundance comparable to that of neutrons. However, they have very low ionizing power [43] and induce much less parasitic charge in thin-film semiconductor materials than neutrons; thus, the contribution of muons is neglected here. This study is conducted at the material level, i.e., without integration into electronic devices, an area for which only limited research is available in the literature concerning the three materials considered here [44,45,46,47]. Several limitations characterize these previous studies, particularly with regard to the energy of the incident neutrons. For example, only the high-energy domain (>1 MeV) of the atmospheric neutron spectrum was considered in the simulation in [44], and monoenergetic neutrons were used in studies related to fusion reactions [45]. In studies that take into account the entire neutron spectrum [46,47], the results are limited to analyzing secondary products in terms of number and initial energy, without investigating the energy transfer of these products in the material, the penetration distance, i.e., the range, of the particles in the target or the deposited charge. Unlike studies in references [44,45], this work takes into account the impact of neutrons across the entire atmospheric spectrum, which yields results closer to real conditions. Furthermore, as will be explained later, specific nuclear reactions involving low-energy neutrons can occur and should not be neglected. Then, this paper highlights the specific radiative responses of AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 to each of the three energy domains of the atmospheric neutron spectrum at sea level. In comparison to works in [46,47], we have investigated additional key parameters, including linear energy transfer (LET), range, and the energy deposited in the material by the secondary products of neutron interactions. These quantities are essential for characterizing the ability of an ionizing product to generate transient parasitic currents capable of disturbing the circuit operation. This paper provides a detailed analysis of these quantities and conducts an in-depth comparison of the susceptibility to neutron irradiation of the three materials. The simulation of neutron-material interactions was carried out using the Geant4 Monte Carlo code [48,49,50], which provided very detailed information for each interaction, including the type and number of secondary ionizing products, as well as their energy. The SRIM code [51,52] was then used to process this information, in order to obtain the LET and the distance travelled in the material before stopping for each secondary product. The Geant4 and SRIM outputs were also used to estimate the number of electron-hole pairs likely to be created in the material by these ionizing particles and to evaluate the charge that could be deposited within the first tens of nanometers from the reaction location.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 first presents some properties of the bulk materials studied here that are necessary for studying the radiative response of these materials. It then describes the origin of atmospheric neutrons and their spectrum at sea level, as well as the possible neutron-matter interactions and the effects of these single events on devices and circuits. Section 2 ends with a presentation of the simulation codes used in this study: the Geant4 Monte Carlo code and the SRIM code. Section 3 presents the simulation results and provides a detailed analysis of reactions between neutrons and materials, with a particular focus on the 14N(n,p)14C reaction in AlN. The secondary products of these reactions are then analyzed, especially in terms of the average number per reaction, the energy distributions for the thermal, intermediate and high-energy domains of the spectrum, the histograms of linear energy transfer and of the range in the materials. This section also presents a specific study of products with sufficient energy to potentially cause errors in circuits. In Section 4 we analyze all these results and compare the sensitivity of the three materials to atmospheric neutrons for these three energy domains of the spectrum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Properties

The main characteristics of the simulated materials, including density, molar mass, number of atoms per cm3 and bandgap, are shown in Table 1 [44,53,54,55]. These characteristics were used as input parameters for the simulations performed in this study. The last line of this table refers to the mean energy required to create an electron-hole pair in the material, . This parameter is crucial for estimating the number of electron-hole pairs created in the target after an ionizing particle passes through it and transfers its energy to the material. Each material has a specific value, which is measured experimentally or obtained from simulations. If measured or simulated values are not available for a given semiconductor, the Klein model [56] can be used. This model provides an estimate of using the band gap energy of the material, assumed to be known. The values for AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 are given in Table 1 [55,57,58].

Table 1.

Main characteristics of simulated materials at 300 K.

In addition to the properties presented in Table 1, the simulation codes need precise information about the isotopic composition of each material’s atoms. For this study, we considered the natural isotopic composition and abundance of carbon (Z = 6), nitrogen (Z = 7), oxygen (Z = 8), aluminum (Z = 13) and gallium (Z = 31) atoms. Three of these atoms (carbon, nitrogen and oxygen) have several isotopes, but only one of these has a high abundance, with the other isotopes being rare: carbon has two isotopes, 12C and 13C, with natural abundances of 98.93% and 1.07%, respectively; nitrogen has two isotopes, 14N and 15N, with natural abundances of 99.6% and 0.4%, respectively; oxygen has three isotopes, 16O with abundance of 99.76%, 17O and 18O with very low abundances of 0.04% and 0.2%, respectively. The last two atoms are aluminum, which has a single isotope (27Al), and gallium, which has two isotopes of comparable abundance: 69Ga (60.1%) and 71Ga (39.9%).

2.2. Atmospheric Neutrons and Their Interactions with Matter

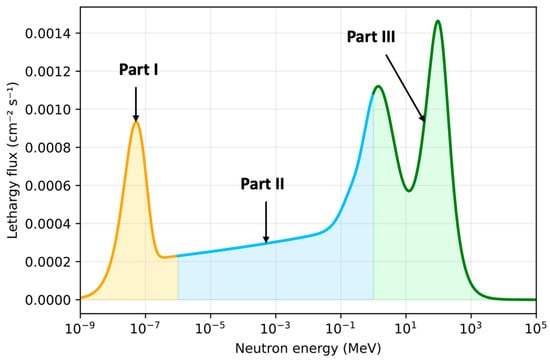

The neutron is an electrically neutral subatomic particle belonging to the baryon family. It has a slightly greater mass than the proton and is unstable in its free state, with a half-life of around 880 s [59]. Its electrical neutrality enables it to penetrate deep into matter, with which it mainly interacts via the strong nuclear force. Atmospheric neutrons are an essential component of secondary cosmic radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. They originate from primary cosmic rays, which are mainly composed of protons (around 85%), alpha particles (around 12%) and heavy nuclei [60]. When they enter the Earth’s atmosphere, these primary cosmic rays interact with nitrogen and oxygen nuclei, producing a hadronic cascade of secondary particles: pions, kaons and nucleons. Neutrons are released primarily through two mechanisms: (i) in direct nuclear reactions involving cosmic protons and atmospheric nuclei, and (ii) through the decay of neutral pions and kaons formed in these reactions [61]. An extremely broad energy spectrum is covered by these secondary neutrons, ranging from thermal neutrons (<10−2 eV) to high-energy neutrons (>109 eV) [62]. The average flux of cosmic neutrons at ground level is in the order of a few tens of neutrons/cm2/h [62]. The spectrum of atmospheric neutrons at ground level, shown in Figure 1, has three main peaks. The first one is a thermal peak, which corresponds to neutrons that have been slowed down through scattering until they reach thermal equilibrium with the surrounding materials [62]. The second peak is a so-called “nuclear evaporation” peak, centered around 1 or 2 MeV. The third peak is a high-energy peak, centered at around 100 MeV. Between the thermal and evaporation peaks, there is a plateau region in which the differential flux is approximately proportional to 1/E. Experimental measurements using ground-based detectors (such as a Bonner multisphere spectrometer) by Golhagen [63] and Gordon et al. [62] have confirmed this spectral structure. As illustrated in Figure 1, the atmospheric spectrum at sea level can be subdivided into three main parts: Part I relates to thermal and epithermal neutrons with energies below 1 eV; Part II relates to neutrons with intermediate energies between 1 eV and 1 MeV; and Part III relates to high-energy neutrons with energies above 1 MeV. Integrating this spectrum yields the total neutron flux, expressed as neutrons per square centimeter per hour; this flux is approximately 7.6 neutrons/cm2/h for Part I, 16 neutrons/cm2/h for Part II, and 20 neutrons/cm2/h for Part III.

Figure 1.

Complete spectrum of atmospheric neutrons at sea level, divided into three parts: Part I for neutron energies below 1 eV, Part II for intermediate-energy neutrons (between 1 eV and 1 MeV) and Part III for high-energy neutrons (above 1 MeV). The lethargy flux is equal to the product of the differential flux (MeV−1 cm−2 s−1) by the energy (MeV).

Although electrically neutral and difficult to detect, the neutron is a highly penetrating particle. Even if the probability of interaction between neutrons and atoms in materials is very low, the nuclear interactions of neutrons with matter are one of the main causes of random errors in modern microelectronic devices [24,64] due to a phenomenon called indirect ionization, explained below. In materials, neutrons do not interact with electrons in atomic shells, but only with atomic nuclei, essentially through two processes. The first process is scattering on nuclei, which can be either elastic or inelastic. During this process, neutrons can transfer an important amount of kinetic energy to the atoms in the lattice. The secondary products of these interactions, known as recoil nuclei, can ionize the matter along their displacement path through the direct ionization mechanism and can cause SEEs (a detailed explanation of this process can be found in Section 2.3). As explained before, the energy transferred to the material may also result in a series of atomic displacements and the formation of crystal defects, such as vacancies and interstitials, collectively referred to as “displacement damage” [34]. This study does not address displacement effects; it only focusses on SEEs, as stated in the introduction. In elastic scattering (reaction (n,n)), both the total kinetic energy and the momentum of the neutron-nucleus system are conserved. The incident neutron transfers some of its energy to the nucleus, but this energy cannot exceed the value given by [65]:

where is the energy of the incident neutron and A is the atomic number of the target nucleus. Inelastic interactions (reaction (n,n′)) are analogous to elastic interactions, except that the target nucleus undergoes an internal rearrangement, placing it in an excited state. The initial total kinetic energy is not conserved, as part of it is used to bring the nucleus into this state. However, if the energy of the incoming neutron is insufficient for the nucleus to be placed in an excited state, an inelastic interaction will be impossible [66]. The second process involves capture reactions, which can be of several types: (i) capture of the type (n,α), (n,p), (n,d), etc., which produce charged light particles (protons, alpha particles or deuterons); (ii) radiative capture reactions (n,γ), in which a neutron is captured by the nucleus, which does not disintegrate; instead, a heavier isotope is formed in an excited state and the process is accompanied by the rapid decay of the resulting nucleus to the ground state through the emission of a gamma photon; (iii) neutral reactions involving the emission of two or more neutrons; and (iv) fission reactions that result in the nucleus splitting into several fragments [66]. These capture reactions, for the most part, produce secondary charged particles such as protons, alpha particles and heavy ions. These charged particles deposit their energy through direct ionization along their trajectory, which is responsible for critical phenomena in microelectronics, such as SEEs [24,25,64], as explained in Section 2.3. All the mentioned neutron interactions (elastic and inelastic scattering, and capture reactions) are nuclear reactions.

2.3. Neutron-Induced Single-Event Effects

The charged particles produced in the various types of neutron-matter interactions described above can trigger SEEs in a circuit according to the following sequence of physical mechanisms: (i) transport of the charged particle in the material and transfer of its energy to the material; (ii) conversion of this energy into electron-hole pairs; (iii) transport and collection of this free charge by sensitive charge collection structures in the devices; (iv) response of the circuit to the resulting parasitic electric current [39,67]. This study focuses more specifically on the first two mechanisms, which are described below.

A charged particle released in the material from a neutron-matter interaction mainly interacts with atomic electrons through Coulomb interactions, and with nuclei at lower energies. The initial energy of the charged particle is transferred, either partially or entirely, to the material through electromagnetic or nuclear processes [68]. In the initial phase of its movement, energy is lost mainly through the ionization of atomic electrons, producing numerous secondary electrons (delta rays) that are capable of ionizing other atoms. This process triggers an electronic cascade. The positively charged ionized atoms reorganize their electrons, creating holes in the valence band. Gradually, the average energy of the free electrons decreases while a high-density channel of electron-hole pairs forms along the particle’s trajectory. In the final phase, the particle slows down and then stops, due mainly to collisions with nuclei. This entire process results in the formation of a column several tens of nanometers in diameter within the material, characterized by a high concentration of charge carriers.

To estimate the amount of energy transferred to the material by the charged particle, two quantities are usually used: the stopping power and the range of the particle in the material. The first quantity has two components: the electronic stopping power (energy lost due to collisions between the particle and atomic electrons), also known as the linear energy transfer (LET), and the nuclear stopping power (energy lost due to interactions between the particle and nuclei). For SEEs, the relevant parameter is the electronic stopping power, which relates to the creation of electron-hole pairs by ionization in the material. The LET value is an important parameter that is connected to the failure voltage of an irradiated device. Thus, the failure voltage is inversely correlated with the LET of the secondary ions produced, because a higher LET deposits more charge in the high-field region, increases the avalanche current, and lowers the voltage at which destructive breakdown occurs, as experimentally demonstrated on SiC and GaN [69]. The range is the distance that the charged particle travels in a material before stopping. The range of ionizing particles also plays a crucial role in determining the location of energy deposition and therefore the probability of triggering an SEB. For example, several studies have shown that the location of charge generation within the drift region influences the probability of reaching the breakdown threshold: complete energy deposition across this region is often necessary to trigger the phenomenon [70]. Finally, it should be recalled that both the LET and the range are specific to each particular charged particle/material couple, as discussed in Section 3.3.

2.4. Simulation Details

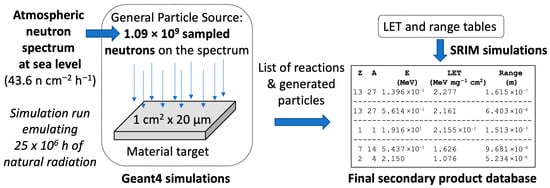

The Geant4 Monte Carlo transport code [71,72] was used to simulate interactions between atmospheric neutrons and the materials studied in this work. Figure 2 summarizes the procedure used in this simulation.

Figure 2.

Schematics of the general principle of the simulation procedure used in this work to study neutron-material interactions, as well as the secondary products resulting from these interactions.

In Geant4, bulk material targets are irradiated virtually with neutrons generated randomly over an energy distribution that follows the atmospheric spectrum (introduced into Geant4 using the General Particle Source [72]). Three parallelepiped-shaped targets made of AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 with the same dimensions (a surface area of 1 cm2 and a thickness of 20 µm, which are analogous to the typical sizes of the sensitive volume of an integrated circuit) were created in the simulation code. As shown in Figure 2, the incident neutrons arrive perpendicular to the target. Since the probability of a neutron interacting with matter is generally very low, a large number of neutron interactions must be simulated to obtain sufficient statistics and accurate results. Therefore, we considered a total of 1.09 × 109 sampled neutrons irradiating the target, and Geant4 simulates then 1.09 × 109 neutron particle histories. This is equivalent to the target being exposed to a total atmospheric neutron flux of 43.6 neutrons per cm2 per hour at sea level [73] for 25 × 106 h, i.e., approximately 2851 years (43.6 n cm−2 h−1 × 25 × 106 h = 1.09 × 109 neutrons per cm2). The target is thus subjected to 1.09 × 109 neutrons distributed across the three parts of the spectrum: 190 million neutrons in Part I, 400 million in Part II, and 500 million in Part III. Further information on the physical processes employed in the Geant4 simulations and target construction can be found in [44,45,46,74,75]. Geant4 simulates the transport of each of these 1.09 × 109 sampled neutrons within the target and records the possible interactions. Geant4 provides an extensive list of outputs about each interaction, including the interaction type, a list of secondary ionizing products and their energies, and the interaction point coordinates. The list of secondary products resulting from interactions includes particles such as neutrons, positrons, gamma photons, mesons and neutral pions, which have very low ionizing characteristics [76]. As these particles are not likely to generate significant number of electron-hole pairs and then to trigger SEEs, we have deliberately removed them from the database.

Data generated by Geant4, including the type and energy of each secondary product, is used in a second simulation with the SRIM (Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter) code [51,52] (as shown in Figure 2). This simulation provides the LET and the range for each ionizing particle produced. The final database comprises a series of files containing detailed information on interaction events between neutrons and the target material, as well as on the secondary products generated in these interactions.

Due to the stochastic nature of the Monte Carlo simulation, the statistical analysis of these Geant4 results must be addressed. In Geant4, each simulated neutron represents a random event: it can interact within the target with a certain probability or pass through it without interaction. Let represent the number of simulated neutrons incident to the target and the number of interactions (or a specific type of reaction) that are counted. Geant4 Monte-Carlo transport code calculates then the absolute statistical uncertainty in the count as

The relative statistical uncertainty (or relative statistical error) is finally given by .

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Neutron Interactions

Table 2 presents the number of interactions caused by atmospheric neutrons in AlN, diamond, and β-Ga2O3, distributed over the three parts of the spectrum. Diamond records the highest number of interactions (1,118,921), reflecting its greater sensitivity compared to β-Ga2O3 (972,017) and AlN (739,681). For all materials, Part II dominates, accounting for at least half of the total events, with β-Ga2O3 showing the strongest relative weight (62.1%). Diamond also exhibits the largest absolute counts in each spectral region, while AlN is less sensitive overall and shows a relatively balanced distribution between Part I (31.8%) and Part II (50%). These differences highlight the material dependence of interaction rates and their spectral distribution. As shown in Table 2, the statistical error of the Geant4 simulation results is very low (below 0.25%) for all materials and for all parts of the spectrum.

Table 2.

Number of interactions resulting from atmospheric neutron irradiation of target materials. The relative statistical error of the Monte Carlo simulation, as calculated by the Geant4 code, is included in brackets.

As neutrons are electrically neutral particles, they pass through matter without interacting in the vast majority of cases. This effect is particularly pronounced for very thin targets, such as the 20-µm layers considered here, where only a very small fraction of the incident neutrons interacts with the nuclei of the target material. For example, in Part I of the spectrum and for AlN, only 234,961 from 190 million incident neutrons interacted with the material. Over the entire spectrum, 739,681 neutrons produced interactions in AlN out of a total of 1.09 × 109 incident neutrons. These figures highlight the very low interaction probability per neutron, which is consistent with the small cross section of neutron–matter interactions.

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 provide more detail on these interactions by showing the main reactions that occur between neutrons and the three materials studied, as well as how frequently they occur. Table 3 summarizes the main nuclear reactions observed between atmospheric neutrons and AlN, classified according to their frequency of occurrence in the three parts of the atmospheric neutron spectrum. The dominant processes are elastic scattering reactions, in particular 14N(n,n)14N and 27Al(n,n)27Al, with Part II clearly contributing the most. Capture channels producing charged light particles are also present: the 14N(n,p)14C reaction is significant, especially in Part I, with more than 26,000 events. Radiative capture reactions such as 27Al(n,γ)28Al and 14N(n,γ)15N contribute at lower levels. Less frequent but noteworthy channels appear in Part III, involving the emission of charged particle, such as protons, alpha particles and various heavy ions. Many other inelastic reactions (not included in Table 3), with multi-particle emissions (up to 11 charged fragments), occur with lower frequencies. These results illustrate the prevalence of elastic scattering but also highlight the diversity of secondary nuclear processes (proton emission, radiative capture, and multi-particle channels) that may influence the overall neutron response of AlN, as will be explained below.

Table 3.

Main reactions (in terms of frequency of occurrence) between neutrons and AlN, and their occurrence for the three parts of the atmospheric spectrum. The relative statistical error of the Monte Carlo simulation, as calculated by the Geant4 code, is included in brackets.

Table 4.

Main reactions (in terms of frequency of occurrence) between neutrons and diamond, and their occurrence for the three parts of the atmospheric spectrum. The relative statistical error of the Monte Carlo simulation, as calculated by the Geant4 code, is included in brackets.

Table 5.

Main reactions (in terms of frequency of occurrence) between neutrons and β-Ga2O3, and their occurrence for the three parts of the atmospheric spectrum. The relative statistical error of the Monte Carlo simulation, as calculated by the Geant4 code, is included in brackets.

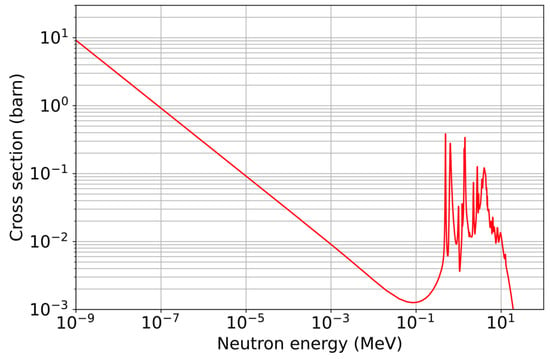

Among all these reactions, the 14N(n,p)14C reaction is of particular interest for the study of SEEs because it is one of the most critical neutron-induced processes in materials containing nitrogen [77]. This reaction has a relatively high cross section in the energy range of atmospheric neutrons, especially for the Part I of the neutron spectrum, as shown in Figure 3. This figure plots the cross-section of the neutron capture process by nitrogen following the reaction 14N(n,p)14C as a function of the neutron energy, calculated using the TENDL open nuclear data library [78]. The 14N(n,p)14C reaction produces protons with an initial energy of 584 keV and 14C ions of 42 keV. As protons are light particles, they have long ranges in materials and can easily reach sensitive regions of the device where they can deposit charge locally, leading to transient or permanent disruptions in microelectronic circuits [77]. For devices based on materials containing nitrogen, this reaction represents then a major reliability challenge.

Figure 3.

Cross-section of the neutron capture by the nitrogen atom through the 14N(n,p)14C reactions versus the neutron energy.

Table 4 presents the main neutron-induced reactions in diamond across the three parts of the atmospheric neutron spectrum. As for AlN, the dominant contribution comes from elastic scattering. In particular the elastic reaction 12C(n,n)12C reaches more than 1.07 million events overall, with the largest proportion occurring in Part II. The second most frequent reaction is 13C(n,n)13C, which occurs at a significant frequency in Part III and highlights the role of the minor isotope of carbon in neutron interactions. Other reactions occur with much lower frequency, such as radiative capture 12C(n,γ)13C or multi-particle emission processes observed mainly in Part III. These reactions illustrate the onset of more complex nuclear processes at higher neutron energies. The results confirm, similar to AlN, that elastic scattering dominates neutron-diamond interactions, while secondary channels, although less frequent, contribute to the diversity of possible reactions and secondary products generated, especially in the high-energy part of the spectrum.

The main neutron-induced reactions observed in β-Ga2O3 are summarized in Table 5. The dominant processes are elastic scattering, particularly 16O(n,n)16O, 71Ga(n,n)71Ga, and 69Ga(n,n)69Ga, which together account for several hundred thousand interactions. As with the two other materials, the majority of these events occur in Part II, corresponding to the intermediate-energy range of the spectrum. Radiative capture reactions, such as 71Ga(n,γ)72Ga and 69Ga(n,γ)70Ga, also contribute significantly, but at lower frequencies compared to elastic scattering. Various additional capture reactions are observed in Part III, including gamma emission accompanied by multiple secondary particles, with thousands of recorded events. Some less frequent channels include the production of light elements, such as 15N and 13C, through reactions with oxygen.

3.2. Number of Secondary Products and Energy Histograms

As explained above, a wide variety of secondary products are created through interactions between atmospheric neutrons and the three target materials studied here. Table 6 shows the number of secondary products resulting from these interactions. These results indicate that the majority of these products come from Part II of the spectrum (between 46 and 60% of the total number of secondary products), corresponding to intermediate-energy neutrons. The highest total number of secondary products is generated by neutron interactions with diamond (1.17 × 106), followed by interactions with β-Ga2O3 (1.01 × 106) and with AlN (8.0 × 105). In Part I, the contributions remain significant, particularly for AlN (32.6% of the total number of secondary products), while in Part III, the proportion of secondary products is around 20% for all materials.

Table 6.

Number of secondary products resulting from neutron interactions with target materials. The relative statistical error of the Monte Carlo simulation, as calculated by the Geant4 code, is included in brackets. 1.090 × 109 neutrons are considered in simulation, following the atmospheric neutron spectrum at sea level.

In order to compare the sensitivity of the three materials to atmospheric neutrons, it is useful to consider the average number of secondary products produced by each material when it interacts with neutrons. Thus, in Figure 4, we have calculated the number of secondary products generated by 1000 neutron interactions for the three materials, separately for the three parts of the atmospheric spectrum and for the complete spectrum. It is important to recall here that we only take into account secondary products with sufficient ionizing power (as explained in Section 2.4). Thus, for elastic and inelastic reactions, as well as radiative capture reactions, only one secondary product is counted in the databases. Figure 4 shows that, regardless of the material, Part III produces the highest number of secondary products, with values ranging from 1230 to 1270 per 1000 interactions, while Parts I and II contribute fewer products. This can be explained by the fact that interactions in Parts I and II are predominantly elastic reactions, which produce a single secondary product. In addition, as shown in Section 3.1, the number of reactions with multiple product emissions is significantly higher in Part III than in Parts I and II. In Part I, diamond and β-Ga2O3 produce about 1000 secondary products (per 1000 interactions, i.e., one product per interaction), while AlN shows a slightly higher value (approximately 1110). This is due to the frequent occurrence of the 14N(n,p)14C reaction, which has a large cross section within the thermal and epithermal neutron energy ranges (Part I, Figure 3) and produces two secondary products. On average, across the entire spectrum, the three materials show comparable results (between 1050 and 1100 secondary products per 1000 interactions).

Figure 4.

Number of secondary products per 1000 interactions, issued from neutron interactions with AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 for the three energy domains and the full atmospheric spectrum.

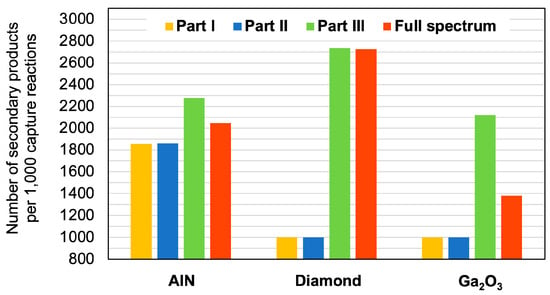

To go further, we only considered capture reactions for each material (eliminating elastic and inelastic reactions that produce a single secondary product). Figure 5 shows the number of secondary products generated in 1000 capture reactions for the three materials. Diamond clearly shows a much higher number of secondary products, particularly in Part III and across the entire spectrum, with nearly 2800 products per 1000 reactions. AlN has more moderate values, ranging from 1800 to 2200 depending on the Part of the spectrum, while β-Ga2O3 has the lowest results. In Parts I and II, AlN has the highest number of products, due to the 14N(n,p)14C reactions, as explained above.

Figure 5.

Number of secondary products per 1000 capture interactions of neutrons with AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 for the three energy domains and the full atmospheric spectrum.

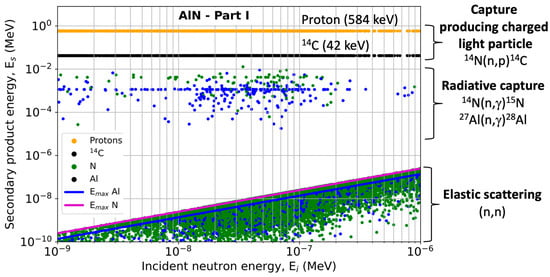

We also examined the energy distributions of these secondary products. Figure 6 shows the energy of secondary products () as a function of the energy of incident neutrons () for AlN and Part I of the atmospheric neutron spectrum. Each colored dot in this figure represents a secondary product. We have also plotted (solid lines) the maximum energy of the recoil nuclei resulting from elastic reactions (calculated using Equation (1)) as a function of the incident neutron energy , for aluminum and nitrogen. The secondary products issued from three types of interaction processes between neutrons and Al and N atoms can be identified in this figure. These products correspond to capture reactions producing charged light particles (14N(n,p)14C reactions), radiative captures (14N(n,γ)15N and 27Al(n,γ)28Al) and elastic collisions (n,n). The 14N(n,p)14C reaction results in the production of protons with a nearly constant energy of around 584 keV, accompanied by a 14C nucleus with a lower energy of about 42 keV. Radiative capture reactions generate secondary products at lower energies, typically distributed in a scattered manner in a range from 10 eV to 10 keV. Finally, as shown in the previous sections, elastic scatterings are the most numerous. In these elastic processes, the secondary products (the recoil nuclei) have low energies, which are limited, as expected, by the theoretical curves for aluminum and nitrogen. This representation once again highlights the important role of nitrogen in AlN, with the very specific 14N(n,p)14C reaction channel leading to energetic protons, which can have a significant impact on the radiation reliability of electronic devices. In contrast, although elastic interactions are very numerous, they produce only secondary products with much lower energy.

Figure 6.

Energies of secondary products generated in the AlN target by interaction with neutrons from Part I of the atmospheric spectrum as a function of the incident neutron energy. The maximum energy of secondary products in elastic reactions, , as calculated using Equation (1) is also plotted for Al and N nuclei.

Figure 7 shows the energy of the secondary products generated in AlN through interactions with neutrons from Parts II (Figure 7a) and III (Figure 7b) of the atmospheric spectrum. In Part II, the neutrons have intermediate energies (up to 1 MeV) and the observed secondary products are mainly due to elastic (n,n) scattering on N and Al atoms. These recoil nuclei have relatively low energies, between 1 meV and 0.3 MeV, while the specific capture reactions 14N(n,p)14C produce protons and 14C nuclei with fixed energies of about 584 keV and 42 keV, respectively. In contrast, Part III corresponds to incident neutrons with energies of up to several hundred MeV. The secondary products are much more diverse and have much higher energies. There is substantial production of protons reaching several hundred MeV, as well as alpha particles and other nuclei resulting from additional capture reactions open to high-energy neutrons. However elastic and inelastic collisions always occur more frequently than capture reactions.

Figure 7.

Energies of secondary products generated in AlN by interaction with neutrons from Parts II and III of the atmospheric spectrum as a function of the incident neutron energy: (a) Part II; (b) Part III; the other products in this figure correspond to secondary products with a Z greater than 2.

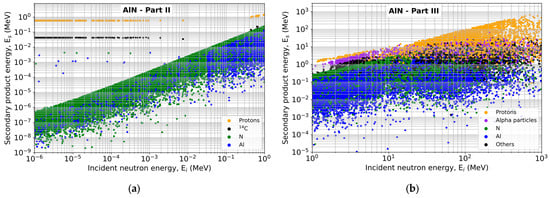

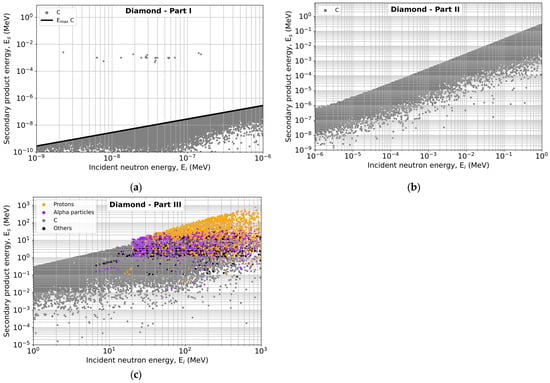

Similar behaviors are observed in neutron interactions with the two other materials: diamond (Figure 8) and β-Ga2O3 (Figure 9). In the case of diamond, in Part I (Figure 8a), the secondary products are almost exclusively carbon nuclei resulting from elastic collisions. Their energies remain very low (<1 eV) and are limited by the theoretical maximum recoil energy for carbon, which is also plotted in the figure. A much smaller number of radiative captures also occur (as indicated in Table 4), producing secondary products with higher energies ranging from 0.1 keV to 10 keV. In Part II (Figure 8b), intermediate-energy neutrons still predominantly induce elastic carbon recoil nuclei, which reach higher energies of up to 0.3 MeV. A wider dispersion of points is observed, reflecting the diversity of possible energy transfers. Finally, in Part III (Figure 8c), the results differ from those of Parts I and II. As the incident neutrons have much higher energies, many reaction channels are open. In addition to carbon nuclei, protons, alpha particles, and other secondary nuclei are produced, often with very high energies (up to several hundred MeV). Unlike Parts I and II, in this part the secondary products are much more diverse and can have very high energies, with direct implications for the reliability of diamond electronic devices. This variety of secondary products, as well as their high energies, reflects the importance of capture reactions in this part of the spectrum.

Figure 8.

Energies of secondary products generated in the diamond target by interaction with neutrons from Parts I, II and III of the atmospheric spectrum as a function of the incident neutron energy: (a) Part I; the maximum energy of secondary products in elastic reactions, , as calculated using Equation (1) for carbon, is also plotted in this figure; (b) Part II; (c) Part III.

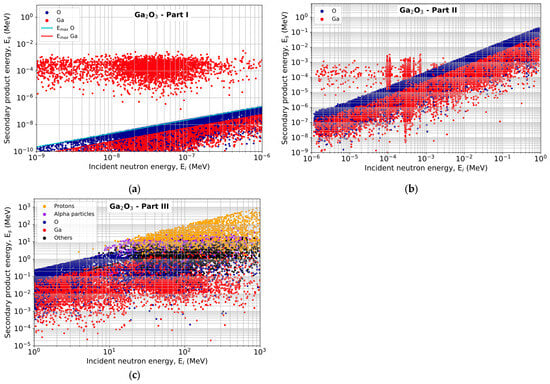

Figure 9.

Energies of secondary products generated in the β-Ga2O3 target by interaction with neutrons from Parts I, II and III of the atmospheric spectrum as a function of the incident neutron energy: (a) Part I; the maximum energy of secondary products in elastic reactions, , as calculated using Equation (1) for O and Ga, is also plotted; (b) Part II; (c) Part III.

In the case of β-Ga2O3, neutrons in Part I mainly generate elastic recoils of oxygen and gallium, with limited energies (Figure 9a), as is also the case with AlN and diamond. Radiative capture reactions also occur, with a higher frequency than AlN and diamond. The secondary products of these capture reactions also have more dispersed energies, between 0.1 eV and 5 keV. In Part II (Figure 9b), neutrons produce more energetic and more dispersed recoil nuclei, indicating the onset of inelastic reactions. In Part III, high-energy neutrons induce numerous protons, alpha particles and other ions, which have high energies, sometimes exceeding 100 MeV. This evolution illustrates the transition from dominant elastic interactions to a wide variety of capture reactions and secondary products with significant energies.

3.3. LET and Range of Secondary Products

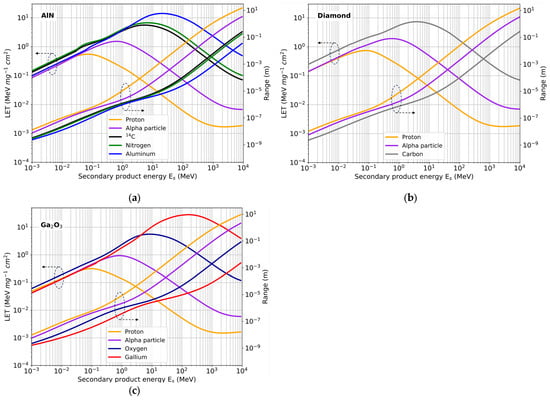

Using the complete list of secondary products resulting from all neutron interactions with each of the three materials, as well as their initial energy, we obtained the initial LET and the range in the different materials for each product. These quantities were calculated using the SRIM code [51,52], as explained in Section 2.4. For each material, we considered the protons, alpha particles, and the nuclei of the atoms that enter into the composition of each material target (Al and N for AlN, C for diamond, and Ga and O for β-Ga2O3). In the case of AlN, we also studied the 14C nucleus, which results from the specific reaction 14N(n,p)14C. It is important to note that the analysis of LETs and ranges does not consider secondary products with energies below 1 eV, since these products cannot deposit enough energy to cause errors in devices and circuits.

Figure 10 shows the LET and range of these charged secondary products in the three materials as a function of their initial energy. The LET and the range of the considered particles exhibit analogous variations as a function of energy in the three materials. At low energies, below 1 MeV, the LET is high because the particles lose their energy rapidly over very short distances, resulting in low ranges. Between 1 and 100 MeV, the LET reaches a maximum, corresponding to the Bragg peak, before decreasing. This behavior reflects the fact that charged particles deposit their energy more efficiently as they slow down. At high energies, above 100 MeV, the LET decreases because the particles interact less frequently with the material, while the range increases substantially and can overcome several millimeters, or even more for protons and alpha particles. The figure shows that protons have a moderate LET, but a very high range. Alpha particles have a larger LET than protons for the same energy, but they travel shorter distances. Heavier nuclei generally have higher LET values than protons and alpha particles, but their ranges are shorter. In general, particles with a larger Z have a higher LET, but lower range. The maximum LET value at the Bragg peak is also higher for heavy ions than for light particles.

Figure 10.

LET and range as a function of the secondary product energy for several secondary products in AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

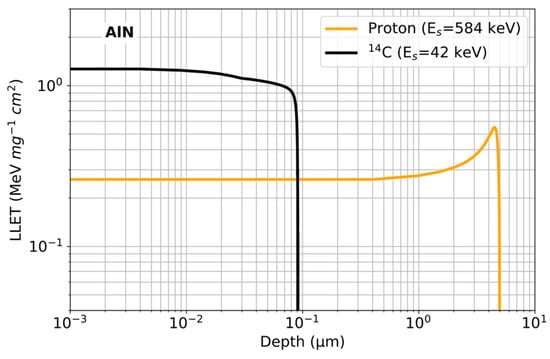

It was also interesting to conduct a more in-depth analysis of the evolution of the secondary products of the 14N(n,p)14C reaction in AlN. As previously mentioned, these products are a proton with an initial energy of 584 keV and a 14C nucleus with an energy of 42 keV. Figure 11 shows how the LET of these particles varies from the point of interaction to the end of their path in the material, calculated using SRIM tables. As shown in this figure, the 584 keV proton has an initial LET of about 0.25 MeV mg−1 cm2 and a range of about 5 μm in AlN. The curve also shows a Bragg peak located at approximately 4.5 µm with a maximum LET value of 0.55 MeV mg−1 cm2. The 14C nucleus, with an energy of 42 keV, has a larger LET of about 1.3 MeV mg−1 cm2, but its range is much smaller at about 91 nm. This reflects a very dense energy deposit at a very reduced depth, which is typical of a heavy, low-energy particle. These results show that, even if the 14C nucleus has a larger initial LET, its range may be too small to reach and deposit energy in the sensitive areas of the device. The situation is different for the 584 keV proton, which has a very large range in AlN. As it passes through the material, the proton loses energy and the LET increases. Due to its large range, it can easily reach sensitive areas of the circuit with an energy close to the Bragg peak, where the LET is maximum [77]. There, it can deposit a sufficient amount of energy to trigger errors in the circuit.

Figure 11.

Linear energy transfer (LET) as a function of depth in AlN for a proton of 484 keV and a 14C ion of 42 keV produced in a neutron reaction with a nitrogen atom (14N(n,p)14C reaction).

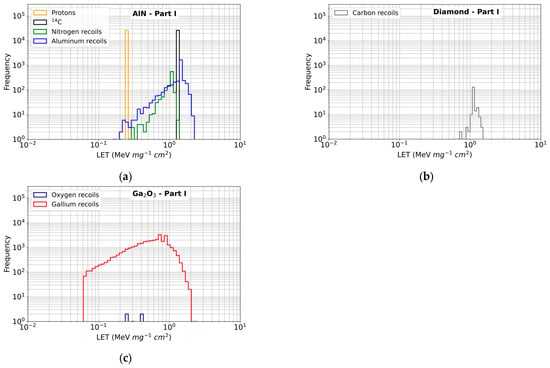

Figure 12 and Figure 13 show the LET and the range histograms of all the secondary products resulting from the reactions between neutrons in Part I of the spectrum and the three materials studied. In AlN (Figure 12a), the secondary products have LETs that cover a relatively wide range of values, from 0.1 to 2 MeV mg−1 cm2. Protons have a relatively low LET, around 0.25 MeV mg−1 cm2. Nitrogen nuclei cover a wider range, centered between 0.3 and 1 MeV mg−1 cm2. The LET values of aluminum nuclei range from 0.2 to 2 MeV mg−1 cm2, while 14C ions produced by the 14N(n,p)14C reaction reach a LET of about 1.3 MeV mg−1 cm2. For diamond (Figure 12b), the only products observed are carbon nuclei. Their LET is concentrated within a narrow range, between about 0.7 and 1.5 MeV mg−1 cm2. This indicates a simpler secondary spectrum than that of AlN, but with particles that locally deposit relatively significant energy. For β-Ga2O3 (Figure 12c), the production is dominated by gallium nuclei, whose LET extends from 0.06 to about 2 MeV mg−1 cm2, with a high frequency around 0.5–1 MeV mg−1 cm2. Oxygen nuclei, which are much less numerous, have more dispersed values within the same range. Looking at the range, in AlN (Figure 13a) the protons resulting from the 14N(n,p)14C reaction have a very long range of around 5 μm, as has been shown previously. On the contrary, the 14C ions produced in the same reaction have very short ranges of around 90 nm. The ranges of N and Al nuclei are mainly between 0.2 nm and 40 nm, reflecting very localized energy deposits. In diamond (Figure 13b), the carbon nuclei show very low ranges, between 0.7 nm and 8 nm, with a narrow distribution, which illustrates the very localized nature of the interactions. Finally, in β-Ga2O3 (Figure 13c), gallium recoils have very small ranges between 0.1 nm and 3 nm. Oxygen recoils have ranges around 1 nm.

Figure 12.

Initial LET histograms for secondary products generated in the material targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part I of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

Figure 13.

Range histograms for secondary products generated in the material targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part I of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

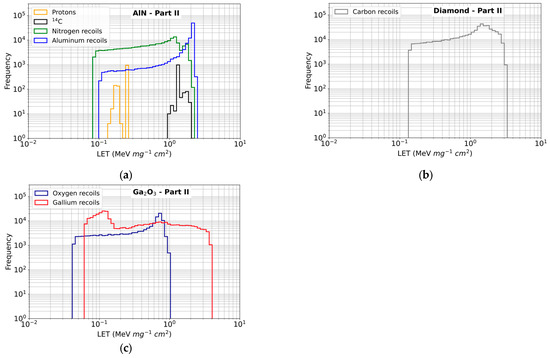

Figure 14 and Figure 15 present the LET and range histograms of the secondary products produced when neutrons from Part II of the atmospheric spectrum interact with the three materials. In AlN (Figure 14a), the protons resulting from the 14N(n,p)14C reaction have a LET range of about 0.1 to 0.3 MeV·mg−1·cm2. The LETs of the 14C ions are around 1 to 2 MeV·mg−1·cm2, while the LET values of the N and Al nuclei cover a wider range, from 0.08 to nearly 3 MeV·mg−1·cm2, with significant frequencies occurring at around 1–2 MeV·mg−1·cm2. In diamond (Figure 14b), the LET values of C nuclei are concentrated between 0.1 and 3 MeV mg−1 cm2, with a maximum frequency around 1.5 MeV mg−1 cm2. In β-Ga2O3 (Figure 14c), the LET values of both the O and Ga nuclei are also high. The LET values of the O nuclei cover a range from 0.04 to 1 MeV mg−1 cm2, while those of the Ga nuclei extend more widely, from 0.06 to 4 MeV mg−1 cm2.

Figure 14.

Initial LET histograms (100 bins) for secondary products generated in the material targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part II of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

Figure 15.

Range histograms (100 bins) for secondary products generated in the material targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part II of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

In terms of range, protons in AlN have ranges of 4 to 20 μm, much higher than those of the heavier recoil particles (N, Al, 14C) which have ranges between 0.1 and 400 nm for N and Al, and 20 to 500 nm for 14C (Figure 15a). In diamond (Figure 15b) and β-Ga2O3 (Figure 15c), the recoil nuclei have ranges between 0.1 nm and 20 μm for the Ga nucleus, and between 0.1 nm and a 300 μm for the C and O nuclei.

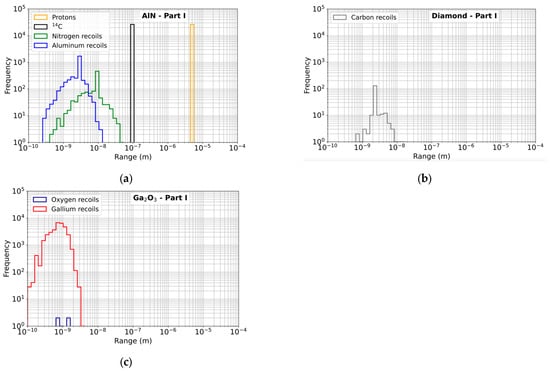

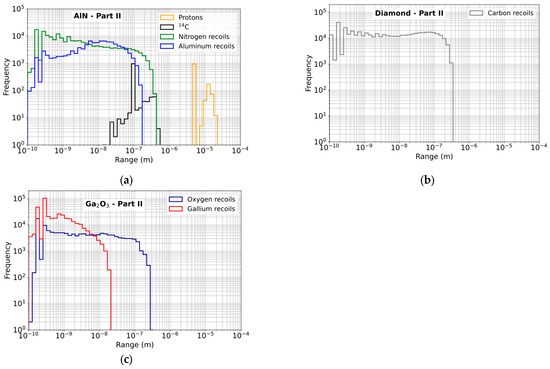

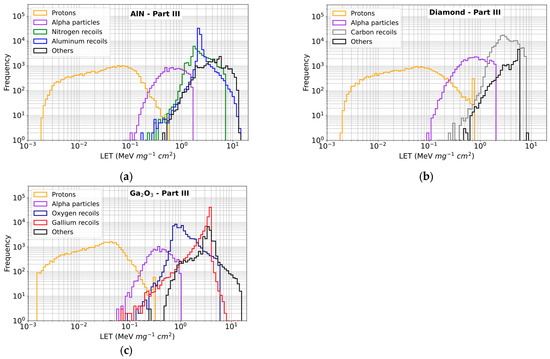

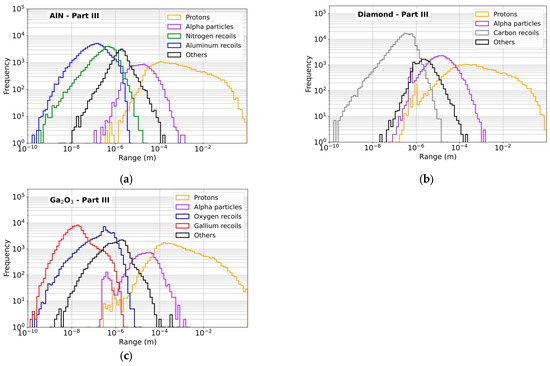

Finally, Figure 16 and Figure 17 show LET and range histograms of all secondary products issued from interaction between neutrons from Part III of the spectrum and the three materials. Concerning the LET (Figure 16), the protons in all three materials have a very low LET value, ranging from 10−3 to 0.8 MeV·mg−1·cm2, with a broad and regular distribution. Alpha particles have LET values in an intermediate range, from about 5 × 10−2 to about 2 MeV·mg−1·cm2, with a narrower curve and a well-marked maximum. The recoil nuclei (N, Al, C, O and Ga), as well as the other products, have high LET values, between 0.1 and 20 MeV·mg−1·cm2, with narrow bell-shaped distributions that indicate a concentrated energy deposition. The curves of the range of the secondary products in Part III (Figure 17) show, as expected, a strong dependence of the range on the mass of the secondary particles. Thus, light particles (protons and alpha particles) have long ranges and more spread distributions, while heavy recoil nuclei (N, C, O, Ga, Al) are confined to small distances, of the order of 0.1 nm to 1 μm. This reflects their role in localized and potentially damaging energy deposits for microelectronic devices. In all three materials, protons show the largest ranges, extending from about 0.5 μm to several millimeters, with a continuous and relatively dispersed distribution. Alpha particles occupy an intermediate range, from about 0.1 μm to a few hundred microns, with a bell-shaped curve centered around about 10 μm in AlN, and 20 μm in diamond and β-Ga2O3. Recoil nuclei and other ions are concentrated in very small ranges, with relatively narrow distributions that indicates rapid energy dissipation.

Figure 16.

Initial LET histograms for secondary products generated in the targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part III of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

Figure 17.

Range histograms for secondary products generated in the material targets by interactions of neutrons with energies in the Part III of the spectrum. (a) AlN; (b) Diamond; (c) β-Ga2O3.

3.4. Deposited Energy and Number of Electron-Hole Pairs per Interaction

As shown in Section 3.2, a large proportion of the secondary products resulting from neutron-material interactions have extremely low energies, particularly for interactions involving neutrons in Parts I and II of the spectrum. These products will not be able to deposit enough energy in the material to cause errors in microelectronic circuits or even produce detectable transient events at the discrete component, device or circuit level. To refine the comparison between materials in terms of sensitivity to neutron radiation, we have considered only the secondary products that can deposit a minimum charge of 0.5 fC in the material. This deposited value may be weak to trigger SEEs in discrete or power electronics; for digital electronics, it corresponds to an average value of the critical charge for modern static memories in sub-14 nm technology nodes, obtained from data reported in the literature and from soft-error rate scaling trends [79,80,81,82].

For a secondary product to deposit a minimum charge of 0.5 fC in the material, it must have a minimum threshold energy , obtained for each material as follows:

where is the electron charge and the energy required to create an electron-hole pair, , is given in Table 1. The values of calculated for AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 are given in Table 7.

Table 7.

Minimum energy of the secondary products required deposit a charge of 0.5 fC in the material.

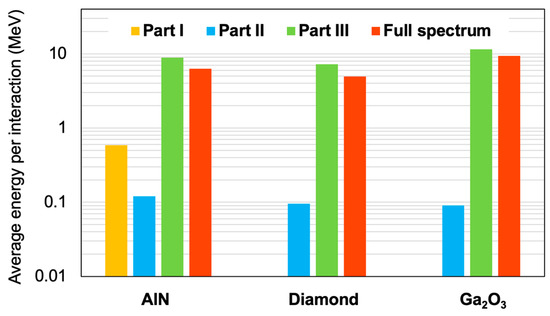

Considering this time only the reactions that generate secondary products with sufficient energy to deposit 0.5 fC in each material, we calculated the average energy deposited per interaction. These results are summarized in Figure 18 for the three materials and the three parts of the atmospheric spectrum, as well as the complete spectrum. For Part I, only AlN undergoes neutron reactions giving products that have energies higher than . These products are 584 keV protons resulting from 14N(n,p)14C reactions; therefore, as shown in Figure 18, the average energy deposited in AlN for Part I is around 0.5 MeV. In the case of diamond and β-Ga2O3, no secondary product issued from interaction with neutron from Part I has sufficient energy to exceed the threshold. Figure 18 shows that for the three materials, the deposited energy is very low in Part II (around 0.1 MeV), which reflects the fact that interactions with intermediate-energy neutrons generate low-energy secondary products. In contrast, reactions involving high-energy neutrons in Part III result in the highest deposited energies, averaging around 9 MeV. Of the three materials, β-Ga2O3 shows the highest deposited energy in this part, with a value above 11 MeV, while diamond has the lowest, at around 7 MeV. Finally, for the complete spectrum, the energies deposited by the neutron interactions remain close between the three materials, at around 7 MeV, but β-Ga2O3 still presents the highest deposited energy, approaching 10 MeV. Section 4 will provide a detailed discussion of the implications of these results for the radiative sensitivity of these materials.

Figure 18.

Average deposited energy per interaction for Parts I, II, III and the full spectrum by secondary products in AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 bulk targets. Only secondary products with initial energies above are considered in the estimation of this metric.

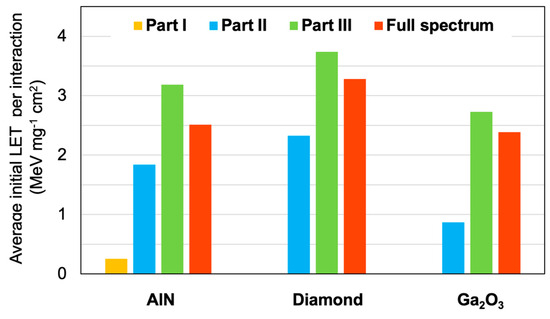

Another interesting quantity for studying the SEEs is the average initial LET of the secondary products. This is illustrated in Figure 19 for the three materials and for the three parts of the neutron spectrum, as well as the full spectrum. As before, we have only considered reactions giving products with an energy above the threshold. For Part I, the average initial LET is very low in AlN (around 0.25 MeV mg−1 cm2). This is because the protons from the 14N(n,p)14C reaction, deposit very little energy per unit length, even though they have a significant initial energy (this is due to the fact that protons are the lightest particles, as explained in Section 3.3). Like Figure 18, neither diamond nor β-Ga2O3 have products with energies above the threshold in Part I; their contribution to the average LET in Part I is zero. In Part II, the LET value of secondaries increases considerably compared to Part I, particularly for diamond (approximately 2.3 MeV mg−1 cm2), and to a smaller extent for AlN (approximately 1.8 MeV mg−1 cm2), while β-Ga2O3 is the material that is affected the least (approximately 0.9 MeV mg−1 cm2). The average LET values in Part III exceed those in the other parts, with maximum LET values reaching 3.7 MeV mg−1 cm2 for diamond, 3.2 MeV mg−1 cm2 for AlN and 2.7 MeV mg−1 cm2 for β-Ga2O3. Considering the full spectrum, the values vary between 3.3 and 2.4 MeV mg−1 cm2, with the strongest average LET being obtained for diamond and the weakest for β-Ga2O3.

Figure 19.

Average initial LET per interaction for Parts I, II, III and the full spectrum by secondary products in AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 bulk targets. Only secondary products with initial energies above are taken into account.

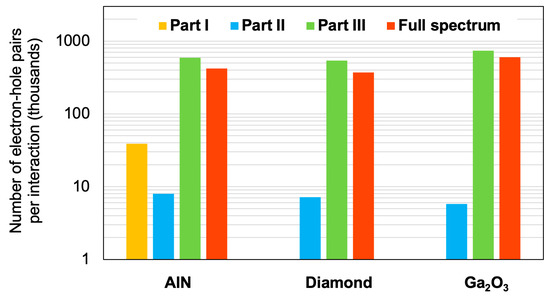

Finally, the average energy per interaction values previously calculated (Figure 18) were used to obtain an estimate of the number of electron-hole pairs that can be created in the material if the secondary product transfers all of its energy to the material. This parameter is an interesting indicator for evaluating the radiative sensitivity of materials, because the number of electron-hole pairs generated by the interactions directly affects the occurrence probability of an SEE. The number of electron-hole pairs per interaction, obtained by dividing the average energy per interaction by (Table 1), is shown in Figure 20. For all three materials, the number of electron-hole pairs is significantly higher in Part III than in Parts I and II. This is due to the higher energy of the neutrons in Part III, which produce secondary products capable of generating more charge carriers. However, AlN exhibits a significant quantity of secondary products in Part I generated in the 14N(n,p)14C reaction. In contrast, no charge is generated by the other materials in this Part of the spectrum. When the materials are compared, β-Ga2O3 appears to have the highest number of electron-hole pairs for Part III and the full spectrum, but the lowest values for Part II. AlN occupies an intermediate position with significant values, though lower than those of β-Ga2O3 for Parts III and the full spectrum. Diamond shows the lowest results for Part III and the full spectrum.

Figure 20.

Average number of electron-hole pairs per interaction for Parts I, II, III and the full spectrum by secondary products in AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 bulk targets. Only secondary products with initial energies above are taken into account.

4. Discussion

The results presented in Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 show significant differences between the three materials. For Part I, AlN exhibits the most significant response in terms of the average energy deposited per interaction, the average linear energy transfer (LET) and the number of electron-hole pairs generated by the 14N(n,p)14C reaction, which exhibits a high cross-section in the thermal and epithermal neutron range. This reflects the sensitivity of AlN to thermal neutrons, which could cause problems in highly moderated environments (such as near hydrogenated reservoirs). In comparison to AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 have better resistance to this range of low-energy neutrons. The results for Parts II and III are less obvious. Diamond shows the lowest values for both the average energy deposited per interaction and the number of electron-hole pairs, which confirms its potential as a robust material, thanks to its low interaction probability and wide band gap. However, diamond is overall the most sensitive to intermediate and fast neutrons in terms of average initial LET. Despite its structural strength, these results demonstrate that diamond can experience substantial energy deposition, suggesting potential concerns regarding its radiative reliability. β-Ga2O3 shows the highest energy deposition and number of generated electron-hole pairs in Part III, although its advantageous electronic and thermal properties. This suggests an increased vulnerability to fast neutrons. However, β-Ga2O3 is the least affected in terms of average LET by intermediate and high-energy neutrons, but still experiences high LET in Part III and under the full spectrum. Finally, AlN shows intermediate values, between those of diamond and β-Ga2O3, for all quantities in Parts II and III.

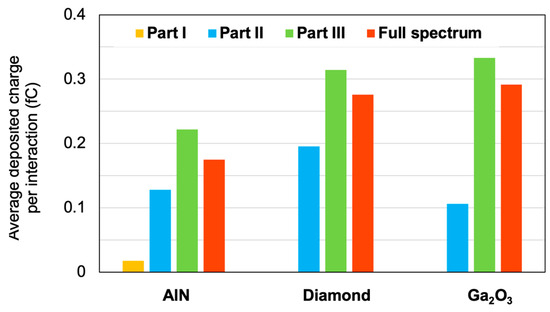

We also analyzed the charge deposited by the secondary products in the area immediately surrounding the point of interaction, over a distance of = 20 nm from the interaction site. This is an interesting metric because it combines some of the previously studied quantities, namely the initial LET of the particle and the electron-hole pair creation energy of the material, also considering its density. Then it constitutes a relevant indicator of the sensitivity of a material to the particle radiation. The deposited charge was calculated by taking into account the initial LET of the secondary product (under the assumption that the LET remains constant over the distance ), the material density , and the electron-hole pair creation energy () of each material [39,76]

where and are given in Table 1 for each material. Figure 21 shows the results for AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 as a function of the three parts of the neutron spectrum and the full spectrum. As shown in the figure, AlN has relatively low values of collected charge, ranging from approximately 0.02 fC for Part I to 0.22 fC for Part III. Diamond exhibits higher deposited charges in Parts II and III, with values around 0.2 fC and 0.32 fC, respectively. β-Ga2O3 has the lowest value in Part II (about 0.1 fC), but achieves the highest values in Part III (above 0.35 fC) and across the entire spectrum. For the full spectrum, AlN shows the lowest deposited charge (almost two times lower than that of β-Ga2O3) due to the combination of a relatively lower average initial LET, a high value of the electron-hole pair creation energy and a lower density than those of the two other materials.

Figure 21.

Average deposited charge per interaction in the first 20 nm from the interaction location for Parts I, II, III and the full spectrum in AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 bulk targets. Only secondary products with initial energies above are taken into account.

These results indicate that diamond and β-Ga2O3 are more sensitive to environments where high-energy neutrons dominate, such as in aerospace environments or in experimental nuclear fusion facilities. In contrast, AlN appears more robust since the deposited charge is lower than that of diamond and β-Ga2O3, which provides better intrinsic immunity against high-energy neutrons in Part III of the spectrum. These results are slightly different from those of references [46,47], which showed a good behavior of β-Ga2O3 under high-energy neutrons. However, as explained in the introduction, the results in [46,47] were based exclusively on the analysis of the number of interactions between neutrons and the material. In contrast, the analysis presented in this work is much more accurate, since it is based on more rigorous metrics taking into account both the linear energy deposited and the number of electron-hole pairs created in the material following the interactions. For neutrons with intermediate energies (part II of the spectrum), diamond is the more sensitive, but deposited charges for the three materials are lower in this part than for high-energy neutrons. Finally, for thermal or epithermal neutrons (Part I), the deposited charges are negligible in diamond and β-Ga2O3, while for AlN this charge is low but not entirely negligible.

Finally, it is important to note that these results should be interpreted with caution. A more accurate analysis would require taking other essential factors into account when making tentative projections at the device level. Phenomena such as charge carrier recombination and the effect of the electric field, which influences both the amount of collected charge and the generated transient currents, should be considered. Furthermore, the design of the device itself, the presence of defects, and leakage currents all play a crucial role in radiation tolerance. A complete evaluation would therefore require dedicated simulations of real structures, which is beyond the scope of this study. And finally, these predictions would need to be confirmed by experimental analysis once components fabricated from these materials are available for testing in a neutron radiation environment.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this work was to evaluate and compare the radiative response of AlN, diamond and β-Ga2O3 when subjected to the full spectrum of atmospheric neutrons at ground level. The results obtained from simulation performed with the Geant4 and SRIM codes were used to analyze the secondary products generated by neutron interactions in detail, as well as their energy distributions, LET, range, and charge deposited in the first nanometers. These results show that AlN is the most sensitive to thermal neutrons due to the 14N(n,p)14C reaction, while diamond and β-Ga2O3 are almost insensitive in this range. For intermediate and fast neutrons, diamond has the lowest deposited energies but a high initial LET, indicating a potential risk of significant SEEs. β-Ga2O3 deposits the most energy and charge for fast neutrons, making it more vulnerable in environments where this component dominates. AlN shows an intermediate response but remains overall the most robust material in terms of charge deposited in a sensitive volume. With all the precautions mentioned previously, these results provide quantitative information and metrics concerning the sensitivity of these materials to atmospheric neutrons. Future work should focus on simulations of realistic structures, particularly at the device level, to refine the understanding of the effects of neutron interactions on the circuit reliability. It should also involve the experimental testing of components made from these materials. Furthermore, the study and optimization of neutron shielding solutions could be a promising approach to further enhance the radiation tolerance of these components, especially for the most critical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and J.-L.A.; methodology, D.M. and J.-L.A.; software, D.M. and J.-L.A.; formal analysis, D.M. and J.-L.A.; investigation, D.M. and J.-L.A.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and J.-L.A.; visualization, D.M. and J.-L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.; Shen, D. Recent advances in optoelectronic and microelectronic devices based on ultrawide-bandgap semiconductors. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2022, 83, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.P.; Tyagi, R. Wide bandgap compound semiconductors for superior high-voltage unipolar power devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1994, 41, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiwaki, M.; Sasaki, K.; Murakami, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Koukitu, A.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Recent progress in Ga2O3 power devices. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.Y.; Chowdhury, S.; Hollis, M.A.; Jena, D.; Johnson, N.M.; Jones, K.A.; Kaplar, R.J.; Rajan, S.; Van de Walle, C.G.; Bellotti, E.; et al. Ultrawide-Bandgap Semiconductors: Research Opportunities and Challenges. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2018, 4, 1600501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.J.; Yang, J.; Cary, P.H.; Ren, F.; Kim, J.; Tadjer, M.J.; Mastro, M.A. A review of Ga2O3 materials, processing, and devices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiwaki, M.; Sasaki, K.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Gallium oxide (Ga2O3) metal-semiconductor field-effect transistors on single-crystal β-Ga2O3 (010) substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 013504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Shao, G.; Chen, G.; He, S.; Wang, W.; Bu, R.; Wang, H.-X. High Breakdown Electric Field Diamond Schottky Barrier Diode with SnO2 Field Plate. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2002, 12, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikanthababu, N.; Sheoran, H.; Siddham, P.; Singh, R. Review of Radiation-Induced Effects on β-Ga2O3 Materials and Devices. Crystals 2022, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.H.; Bierwagen, O.; Kaplar, R.J.; Umezawa, H. Ultrawide-bandgap semiconductors: An overview. J. Mater. Res. 2021, 36, 4601–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.H.; Higashiwaki, M. Vertical β-Ga2O3 power transistors: A review. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2020, 67, 3925–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabak, K.D.; Leedy, K.D.; Green, A.J.; Mou, S.; Neal, A.T.; Asel, T.; Heller, E.R.; Hendricks, N.S.; Liddy, K.; Crespo, A.; et al. Lateral β-Ga2O3 field effect transistors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 35, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Yaita, J.; Kato, H.; Makino, T.; Ogura, M.; Takeuchi, D.; Okushi, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Hatano, M. 600 V diamond junction field-effect transistors operated at 200 °C. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2014, 35, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masante, C.; Rouger, N.; Pernot, J. Recent progresses in deep-depletion diamond metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 233002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtadi, S.; Hwang, S.M.; Coleman, A.; Asif, F.; Simin, G.; Chandrashekhar, M.V.S.; Khan, A. High electron mobility transistors with Al0.65Ga0.35N channel layers on thick AlN/sapphire templates. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2017, 38, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniyasu, Y.; Kasu, M.; Makimoto, T. An aluminium nitride light-emitting diode with a wavelength of 210 nanometres. Nature 2006, 441, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Baines, Y.; Beam, E.; Borga, M.; Bouchet, T.; Chalker, P.R.; Charles, M.; Chen, K.J.; Chowdhury, N.; Chu, R.; et al. The 2018 GaN power electronics roadmap. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, H. Recent advances in diamond power semiconductor devices. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2018, 78, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isberg, J.; Hammersberg, J.; Johansson, E.; Wikström, T.; Twitchen, D.J.; Whitehead, A.J.; Coe, S.E.; Scarsbrook, G.A. High carrier mobility in single-crystal plasma-deposited diamond. Science 2002, 297, 1670–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikata, S. Single crystal diamond wafers for high power electronics. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2016, 65, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Yuan, L.; Jia, R.; Peng, B.; Zhang, Y. A state-of-art review on gallium oxide field-effect transistors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 383003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Yao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, W.; Guo, Y.; Tang, W. β-Ga2O3-Based Power Devices: A Concise Review. Crystals 2022, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; He, Q.; Jian, G.; Long, S.; Pang, T.; Liu, M. An Overview of the Ultrawide Bandgap Ga2O3 Semiconductor-Based Schottky Barrier Diode for Power Electronics Application. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messenger, G.C.; Ash, M.S. Single Event Phenomena; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T.; Ibe, E.; Baba, M.; Yahagi, Y.; Kameyama, H. Terrestrial Neutron-Induced Soft Error in Advanced Memory Devices; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, P.E.; Shaneyfelt, M.R.; Schwank, J.R.; Felix, J.A. Current and Future Challenges in Radiation Effects on CMOS Electronics. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2010, 57, 1747–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Zhu, H. A review of ultra-wide-bandgap semiconductor radiation detector for high-energy particles and photons. Nanotechnology 2025, 36, 152002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.; Aitkaliyeva, A.; Xian, M.; Ren, F.; Khachatrian, A.; Ildefonsorosa, A.; Islam, Z.; Rasel, M.; Haque, A.; Polyakov, A.; et al. Review—Radiation Damage in Wide and Ultra-Wide Bandgap Semiconductors. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasica, M.J.; Wampler, W.R.; Vizkelethy, G.; Hehr, B.D.; Bielejec, E.S. Photocurrent from Single Collision 14-MeV Neutrons in GaN and GaAs. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2020, 67, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Peng, C.; Zhang, X.; Liang, X.; Fu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, Z.; et al. Single-event burnout in β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diode induced by high-energy proton. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 092101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, R.M.; Ball, D.R.; Zhang, E.X.; Islam, S.; Senarath, A.; McCurdy, M.W.; Farzana, E.; Speck, J.S.; Karom, N.; O’Hara, A.; et al. Low-Energy Ion-Induced Single-Event Burnout in Gallium Oxide Schottky Diodes. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2023, 70, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Lin, D.; Lv, L.; Cao, Y.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Study on the single-event burnout mechanism of GaN MMIC power amplifiers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 082105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grome, C.A.; Ji, W. A Brief Review of Single-Event Burnout Failure Mechanisms and Design Tolerances of Silicon Carbide Power MOSFETs. Electronics 2024, 13, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, D.; Fu, K.; Mudiyanselage, H.D.; Fu, H.; Zhao, Y. A review of ultrawide bandgap materials: Properties, synthesis and devices. Oxf. Open Mater. Sci. 2022, 2, itac004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Was, G.S. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science: Metals and Alloys; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kotomin, E.A.; Kuzovkov, V.N.; Lushchik, A.; Popov, A.I.; Shablonin, E.; Scherer, T.; Vasil’chenko, E. The Annealing Kinetics of Defects in CVD Diamond Irradiated by Xe Ions. Crystals 2024, 14, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Tan, X.; Han, Y.; Ren, L. Simulation study on single-event burnout in field-plated Ga2O3 MOSFETs. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 149, 115227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, P.; Dang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Xiang, H.; Su, J.; Liu, Z.; Si, M.; Gao, J.; et al. Ultra-wide bandgap semiconductor Ga2O3 power diodes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]