Abstract

In the cone of positive quadratic forms , it is shown that there exists in the neighborhood the quadratic form , a large cluster of non-equivalent S0-subcones of positive volume.

1. Introduction

Quadratic forms, translation lattices, and parallelohedra play a predominant role not only in the geometry of numbers but also in crystallography, where the lattice-like arrangement of atomic building blocks is a fundamental property of regular crystals. In crystallography, the discovery of quasicrystals, the structure of which can be viewed as projected from higher dimensional translation lattices, has greatly stimulated the investigation of lattices and parallelohedra in arbitrary dimensions. A reduction in quadratic forms and classification of parallelohedra requires, with increasing complexity, a partition of the cone of positive-definite quadratic forms.

In higher dimensions, quadratic forms corresponding to special lattices of densest packings of balls were widely investigated. In a more general approach, the collective of all lattices in the open cone of positive-definite quadratic forms is considered by studying its subdivision into - and -subcones.

In order to find -classes in it is worth looking at the parallelohedra of the maximal finite irreducible subgroups of given by Plesken and Pohst [1]. In Table 1, the subgroups to are listed, each given by its order, its combinatorial type and its number of zones, whereof the number of closed zones is stated within brackets, as well as its number of belts. It becomes evident that many of these parallelohedra are minimal, having only open zones, whereof five types viz.: , , , , and are as much minimal as maximal. Of those, the exceptional lattice is well-known and was described in detail by Conway and Sloane [2]. The lattice takes a particular position as it is the first case of a non-trivial self-dual lattice in , . It also occurs in classifying Lie-algebras.

Table 1.

The parallelohedra of the maximal finite irreducible subgroups of .

In Section 2, the necessary definitions and notations are given. In Section 3, the parallelohedron belonging to the lattice is described, and its symmetry group is determined. In the following Section 4, the neighborhood of the lattice is investigated in order to find generic parallelohedra which are as much minimal as maximal. As a result, it is proven that in the neighborhood of there exists large clusters of non-equivalent -subcones which are as much minimal as maximal.

2. Basic Notations

The notations and methods developed in previous papers [3,4,5,6,7] will be applied. For convenience, the main definitions and tools will be summarized in this preliminary Section.

In Euclidean space , a translation lattice is given by

with lattice basis , , and origin O.

The Gram matrix of is defined by the inner products

Vice versa, determines up to an isometry in .

The dual basis is given by

where , , is the outer product of {. It holds that and .

The components of a lattice vector depend on the choice of the lattice basis . For any , is an equivalent lattice basis, and is called arithmetically equivalent to .

Within an infinite class of arithmetically equivalent Gram matrices, a Gram matrix is referred to as being optimal if it minimizes the magnitudes of the components of all lattice vectors within a given ball of finite radius . In [8], the concept of an optimal basis was introduced. It simultaneously reduces the Gram matrices and such that is minimal, where . We obtain

In low dimensions, reasonable results are obtained by successively applying only transpositions , , for . Note that for , in general, is not a steadily decreasing function of transpositions.

For a translation lattice having Gram matrix , its Dirichlet parallelohedron at the origin O is obtained by intersections of closed half-spaces,

and thus,

It is sufficient to consider lattice vectors only within a ball of radius 2R with center in O, where R is the radius of the largest interstitial ball that can be embedded into .

A parallelohedron in its face-to-face tiling of is denoted as being primitive or generic if in every vertex of exactly adjacent parallelohedra meet. A primitve parallelohedron in has the maximal number of facets. Voronoï [9] proved that every primitive parallelohedron is affinely equivalent to a Dirichlet parallelohedron.

A polytope consists of k-faces, . The 0-faces are the vertices, the 1-faces are the edges, the -faces are called ridges, and the -faces are called facets. The number of facets and the number of vertices define the short symbol for . Among the k-faces of a polytope exists a partial ordering with respect to the inclusion operation “⊂” which defines their hierarchical structure. The k-faces of together with the empty set determine the face lattice . Polytopes that have isomorphic face lattices are denoted as being combinatorially equivalent.

Let be the parallelohedron at the origin of . If the lattice vector carries onto such that is a common facet, then is called a facet vector. The set of facet vectors is denoted by .

The face lattice is used in order to determine the unified polytope scheme and the automorphism group .

The face lattice guarantees the existence of subseries of mutually subordinated k-faces

denoted as d-flag. Each k-face , , corresponds to a k-dimensional polytope . Its face lattice is given by the quotient of . (The quotient corresponds to the face lattice of the polytope .) Therefore, it is possible to number all k-faces of in a systematic way, beginning at the bottom of the d-flag as shown in [10]. This is a highly time-consuming process. The polytope scheme is obtained by writing down for each facet , , the numbers in increasing order of their subordinated vertices , . The scheme depends on the chosen d-flag. For all possible d-flags the corresponding scheme is determined and lexicographically ordered. In this lexicon, the first scheme is denoted as unified polytope scheme, There exists an isomorphism between the unified polytope scheme and the combinatorial type of the polytope .

The number of identical unified schemes corresponds to the order of the automorphism group . Each scheme in the class of identical unified schemes corresponds to a permutation of the basis vectors. There exists an isomorphism between the class of identical unified schemes and the automorphisms of . Let be a matrix with columns given by the basis vectors (Note that this is only possible for irreducible groups.) Applying the permutation to the basis vectors gives

(In the case that the group is reducible the process has to be repeated for each invariant subspace).

Zones and belts of a parallelohedron are crucial for further operations on parallelohedra.

Definition 1.

A belt B of a parallelohedron is a complete set of parallel ridges of .

A belt contains either four or six ridges and thus four or six facets. Primitive parallelohedra contain 6-fold belts only which are determined by a triplet of facet vectors that fulfills the belt conditions,

Definition 2.

A zone Z of a parallelohedron is a complete set of parallel edges of .

The edges of a zone Z are parallel to a dual zone vector . Referred to the dual basis (3), has integer components,

With respect to any zone vector the lattice vectors may be classified into layers

A zone Z is referred to as being closed if every 2-face of contains either two edges of Z or else none. Otherwise, Z is denoted as being open.

Belts and zones of a parallelohedron will prove to be of particular importance. In [4], the operation of a zone contraction , and its inverse operation, the zone extension , were introduced.

Let be a parallelohedron with s closed zones. A zone contraction is the process of contracting every edge of a closed zone by the amount of its shortest edge. and thus, the zone Z becomes open, or vanishes completely. If all zones of are open, then is denoted to be totally contracted, or minimal.

, is a zone extension of by if

Zone contractions and extensions are invariant under affine transformations.

In [3], it was proved:

Theorem 1.

A zone with zone vector is closed, or extendable if and only if all facet vectors of lie in layers , , only.

The zone vector does not necessarily belong to the zones of . Let be an extension of by . The corresponding Gram matrix is given by

If a parallelohedron allows no extensions, then is denoted to be maximal. Each maximal parallelohedron defines a zone-contraction lattice by contracting all combinations of closed zones. It is partially ordered by zone contraction. The least upper and greatest lower bounds are defined by the union and intersection of closed zones.

In , a quadratic form is defined by

where the tensor product and are represented as vectors in .

The closed cone of positive-definite quadratic forms is the set

Given a basis of , a basis of referred to the origin is obtained by the tensor products

with . Since is symmetric, , it follows that the cone can be restricted to a subspace of dimension defined by , .

The cone is partitioned into open, connected subcones of positive volume. Basic is the subdivision into -subcones of equivalent combinatorial types of parallelohedra.

Definition 3.

In the cone , the domain of a combinatorial type of primitive parallelohedron is the open, connected subcone of Gram matrices

For a primitive parallelohedron a border wall is determined by contracting an edge such that facets, having facet vectors , meet in some vertex with

Given the facet vectors , Equation (15) is solved for the , (see [3]). A necessary condition for facets to meet in is given by

The wall normal is normalized such that for , , and .

By contracting an edge , a closed half-space is obtained by

Let be the number of non-equivalent edges of . The closed subcone with apex in becomes (see [5]):

Not all half-spaces induce a wall of .

Next, the cone is partitioned into open, connected subcones of parallelohedra having the same set of facet vectors .

Definition 4.

The connected open domain of all parallelohedra that have the same set of facet vectors is the domain

For a primitive parallelohedron , a border wall is characterized by the loss of at least one pair of facet vectors transforming a 6-fold into a 4-fold belt. Each pair of facet vectors , , belonging to a triplet that fulfills the first two belt conditions (8), defines a closed half-space,

The wall-normal is normalized such that for , , and . For each triplet, three combinations have to be considered in order to obtain all possible half-spaces.

The closed subcone with apex in becomes (see [3]):

Not all half-spaces induce a wall of . The subcone is an aggregation of complete -subcones and contains at least one -subcone.

A Gram matrix is interior to if

Let s, , be the number of closed zones. The number s is an invariant of any primitive -class in . -classes of positive volume occur in dimensions only.

3. The Parallelohedron of the Lattice

Referred to an optimal basis the following Gram matrix is obtained.

The corresponding parallelohedron is computed by half-space intersections (5).

has 240 facets, 19,440 vertices, and 8760 zones all of which are open. Therefore, is minimal. The 120 pairs of facet vectors are listed in Table 2. Applying Equation (10), it is readily verified that for all zone vectors with components , , the facet vectors , , belong to layers , , where . Therefore, by Theorem 1 is as much minimal as maximal.

Table 2.

The facet vectors of .

The 240 facet vectors of all belong to the same equivalence class of norm 2. The group is of order . Because of the high order, the group will be determined by a variant of the method described in Section 2. We note that perpendicular to every facet vector , there exist a sublattice which is equivalent to , and its group is isomorphic to . (Note that is not normal in .) The left coset decomposition of with respect to becomes

The group is determined following the procedure described in Section 2, taking into consideration d-flags that only contain the facet . Then, for the remaining facets , we determine the scheme only up to a unified scheme in order to obtain the coset representatives , , and is the identity .

Below are given generating rotations of order 7 (), 10 (), 12 (), and 15 () which generate the group of pure rotations .

The full group is obtained by including the mirror reflection of order 2,

It holds:

It is sufficient to verify Equation (21) for the generating operations only. The set of coset representatives , , may be obtained as Supplementary Material.

4. The Neighborhood of

In the neighborhood of , a form was found whose parallelohedron is primitive and has the maximal number 510 of facets, 291,432 vertices, and 4881 zones all of which are open. Therefore, is minimal.

The Gram matrix defines the -subcone. For each in the open -subcone, the set of facet vectors is an invariant of and we may denote it by . The facet vectors are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

The facet vectors of .

Applying Equation (10), it is readily verified that for all zone vectors with components , , the facet vectors belong to layers , , where . Therefore, by Theorem 1 is as much minimal as maximal.

In order to calculate the -subcone, all triplets

that fulfill the first two belt conditions (8) are determined. Their number is and the number of half-spaces therefore becomes . Because of the high complexity of the -subcone, the direct computation of as well as of its -subcones is not practicable with small computers. Instead, existence charts may be defined which intersect the -subcone.

According to Equation (20), any further form can be found viz.:

The parallelohedron is primitive and therefore has the maximal number 510 of facets, as well as 241,956 vertices, and 7016 zones all of which are open, and it proves that lies on the boundary of .

The three forms

determine a 2-section through the -subcone. The axes , and define a cartesian coordinate system with an origin in .

Each is obtained by

The condition (20) is used to decide if is interior to . Considering that is an invariant for , the parallelohedron is easily computed.

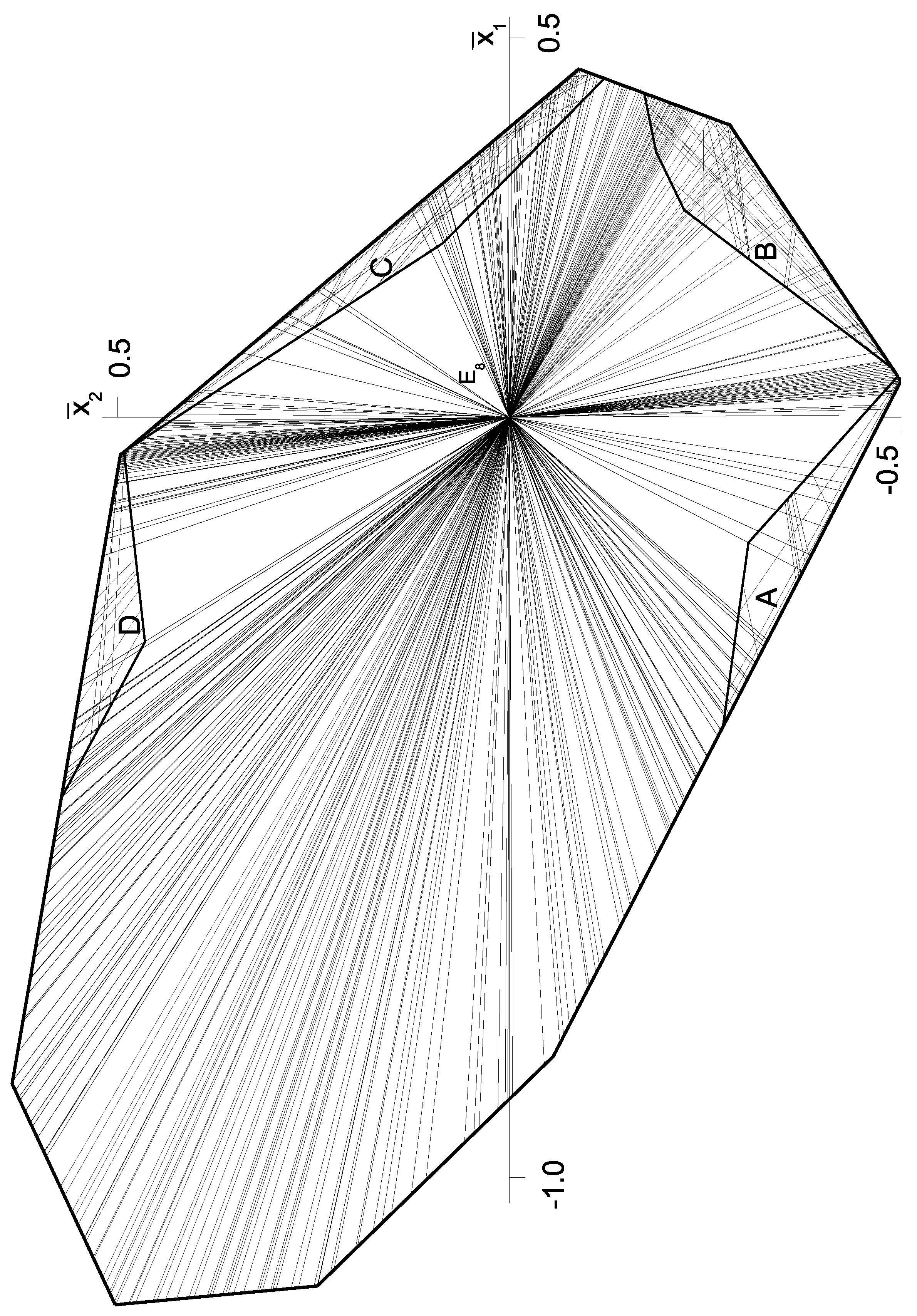

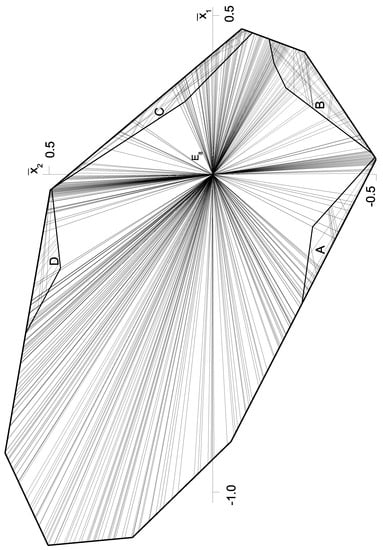

In what follows, the surrounding of the -subcone in the section will be investigated.

First, all walls , containing are determined along the four straight line segments

forming a quadrangle around the center . Applying the method of nested intervals, the border point between two neighboring - and -subcones is easily determined within an -limit. The value of is chosen to be

The point corresponds to a limiting parallelohedron which is characterized to have some vertex where at least d+1 facets meet. Thus, the wall normal perpendicular to the wall can easily be calculated by Equation (16).

Next, the walls , are determined along a radial straight line in going out from the center and lying between two neighboring border lines corresponding to walls and . Applying the method of nested intervals, the border point between two neighboring - and -subcones is easily determined within an -limit. Thus, the wall normal perpendicular to the wall can easily be calculated by Equation (16). This process is continued until at some a is reached. This step has to be repeated along radial straight lines in various directions in order to fix in the border of the cluster . Thereby, the sectors A, B, C, and D were discovered which are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Existencechart through the -cluster in .

5. Results

In Section 3, an optimal basis was used in order to compute the parallelohedron . This has the effect that the components of the facet vectors of as well as of lie in the set only as can be seen from Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Therewith, the computing time is considerably reduced.

A generic -subcone first occurs in . In [7], it was shown that there exists just one class of arithmetically equivalent -subcones. The subcone itself contains at least combinatorial types of -subcones of positive volume. In several, non-equivalent clusters can be found each of which contains a large number of non-equivalent -subcones of positive volume. It shows that there exists a highly complex cluster of -subcones. In Figure 1, the section through is shown. Only the border lines of the -subcones are drawn. Each border line corresponds to a wall having wall normal of a certain -subcone, and therefore, has a representation as a tensor product

There exist two kinds of walls. Walls that separate two adjacent -subcones, and walls that separate a -subcone from a adjacent -subcone. In order to determine all walls, it would require computing a huge number of -subcones which at present is far out of reach.

The walls containing all belong to the class of order 3780 under the group , whereof 607 intersect within the -cluster. A representative wall normal of is given by the tensor product

(see Table 3). Although the walls are equivalent, the -subcones in the -cluster are not equivalent.

The border lines in the -section do not necessarily extend over the whole cluster. When several border lines intersect then some border lines may end at the point of intersection. In Figure 1, it is seen that many of the walls end in the center . We have not investigated this behavior in detail because the substructure in sectors A, B, C, and D proved to be highly complicated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst13020246/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Plesken, W.; Pohst, M. The eight dimensional case and complete description of dimensions less than ten. Math. Comp. 1980, 34, 277–301. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.H.; Sloane, J.A. The Cell Structures of Certain Lattices, Miscelanea Matematica; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 71–107. [Google Scholar]

- Baburin, L.A.; Engel, P. On the enumeration of the combinatorial types of primitive parallelohedra in Ed, 2 ≤ d ≤ 6. Acta Cryst. A 2013, 69, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P. The contraction types of parallelohedra in E5. Acta Cryst. A 2000, 56, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P. On Fedorov’s parallelohedra—A review and new results. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2015, 50, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P. On a special class of parallelohedra in E6. Acta Cryst. A 2019, 75, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P. On the Σ-classes in E6. Acta Cryst. A 2020, 76, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P. Mathematical problems in modern crystallography. Comput. Math. Appl. 1988, 16, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Voronoï, G.M. Nouvelles applications des paramètres continus à la théorie des formes quadratiques. Deuxième mémoire. recherches sur les paralléloèdres primitifs. J. Reine Angew. Math. 2009, 1908, 198–287, Erratum in J. Reine Angew. Math. 2009, 1909, 67–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P. On the enumeration of four-dimensional polytopes. Discret. Math. 1991, 91, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).