Abstract

Salt formation is a useful technique for improving the solubility of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). For instance, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, diclofenac (DIC), is used in a sodium salt form, and it has been reported to form several hydrate forms. However, the crystal structure of the anhydrous form of diclofenac sodium (DIC-Na) and the structural relationship among the anhydrate and hydrated forms have not yet been revealed. In this study, DIC-Na anhydrate was analyzed using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD). To determine the solid-state dehydration/hydration mechanism of DIC-Na hydrates based on both the present and previously reported crystal structures (4.75-hydrate and 3.5-hydrate), additional experiments including simultaneous powder XRD and differential scanning calorimetry, thermogravimetry, dynamic vapor sorption measurements, and a comparison of the crystal structures were performed. The dehydration of the 4.75-hydrate form was found to occur in two steps. During the first step, only water molecules that were not coordinated to Na+ ions were lost, which led to the formation of the 3.5-hydrate while retaining alternating layered structures. The subsequent dehydration step into the anhydrous phase accompanied a substantial structural reconstruction. This study elucidated the complete landscape of the dehydration/hydration transformation of DIC-Na for the first time through a crystal structure investigation. These findings contribute to understanding the mechanism underlying these dehydration/hydration phenomena and the physicochemical properties of pharmaceutical crystals.

1. Introduction

In drug development, improving the poor water solubility of many active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is an attractive area of research. In addition to the formulation of low-crystallinity solids such as solid dispersions [1,2] and cyclodextrin inclusion compounds [3], other methods can increase solubility through the formation of a stable multi-component crystalline state such as salt formation [4], co-crystallization [5], and salt co-crystallization [6,7,8], in which the crystal structure differs from the mother API crystal, providing an opportunity to change the solubility. Among these strategies, salt formation is a common method for enhancing the solubility of some APIs with acidic or basic functional groups (carboxy, conjugated hydroxy, amino, etc.) [9,10]. In particular, sodium salt formation is a well-known technique for increasing the solubility of poorly soluble acidic APIs in drug development, and sodium ions account for approximately 60% of the counter cations of acidic API salts [11].

Sodium API salts often form hydrate crystals in which the water coordination geometry around Na+ is more flexible than the structure of the transition metal ion hydrate owing to the s-block atomic nature of Na [12]. This “pseudo-coordination bond” property of Na+–O(water) interactions contributes the specific hydration–dehydration behaviors of sodium API salts [13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Hydrate crystals often undergo dehydration according to variations in the ambient temperature or humidity and transform into an anhydrous phase with different physicochemical properties [20,21]. Approximately one in three pharmaceutical compounds form hydrate crystals [22], and analyzing the X-ray crystal structure is essential [23] because the physicochemical properties of crystalline materials, such as their solubility [24], hygroscopicity [25,26], and tableting properties [27] depend on their crystal structure [28]. Sometimes, alternations in the crystal structure induced by a dehydration/hydration result in a color change [29,30]. For pharmaceutical hydrates, such property changes may affect their bioavailability and safety as pharmaceutical products. Therefore, the structural investigation of polymorphic transitions and the establishment of dehydration mechanisms of drug hydrates are both important processes in drug development [31].

The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac (DIC, 2-[2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl]acetic acid; Figure 1) is a widely used analgesic, and owing to its high permeability but low solubility, it is categorized as a Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II [32]. Since DIC has an acidic carboxyl group, it can be formulated as a salt with sodium or potassium to improve its solubility. Diclofenac sodium (DIC-Na) has been reported to form several hydrate crystals (Table S1, the Supplementary Materials). Until now, however, the crystal structure of the anhydrous form of DIC-Na and the structural relationship among this anhydrate and DIC-Na hydrates have not yet been elucidated. The crystal structures of DIC-Na pentahydrate, 4.75-hydrate (4.75H), and tetrahydrate were investigated independently, and the reported lattice parameters were almost identical [33,34,35], implying either that they are isostructural hydrates or that hydrate water molecules are misplaced. The trihydrate has also been recognized in the literature, but its crystal structure is still unknown, and the number of water molecules it contains is not clear [36]. In addition, a hemi-heptahydrate (3.5H) form was reported very recently [37]. Multi-component crystals of DIC-Na with organic agents such as phenanthroline [38] and l-proline [39] have also been reported. In particular, the DIC solubility achieved by forming the DIC-Na l-proline salt cocrystal was significantly higher than that of DIC-Na [39]. In the DIC-Na l-proline study, a new hydrate form was observed, but the structure was not revealed. Furthermore, in order to complete the overall picture of the DIC-Na hydrate structures, analyzing the crystal structure of the anhydrous form of DIC-Na is essential, which would also establish the complicated hydration–dehydration mechanism of DIC-Na hydrates. The elucidation of such mechanisms is important in the pharmaceutical sciences.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of diclofenac (DIC).

In this study, a novel crystalline phase, anhydrate (AH), was revealed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis, and the 4.75H and 3.5H crystal structures were re-analyzed for an accurate structural comparison under the same measurement conditions, such as temperature. Simultaneous powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were used to visualize the multi-step dehydration process of DIC-Na 4.75H. Based on the crystal structures, the dehydration mechanism of DIC-Na 4.75H is discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

DIC-Na (anhydrous) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Solvents (tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, and methanol) were obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan), and Sigma-Aldrich Japan (Tokyo, Japan), respectively.

2.2. Preparation of Solid Samples

2.2.1. Diclofenac Sodium 4.75-Hydrate

Dissolving anhydrous DIC-Na (ca. 40 mg) in distilled water (5 mL) and then slowly evaporating the solution yielded plate-like DIC-Na 4.75-hydrate crystals.

2.2.2. Diclofenac Sodium Hemiheptahydrate

Anhydrous DIC-Na (ca. 50 mg) was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (5 mL), followed by the slow evaporation of the solution, which yielded plate-like 3.5H crystals.

2.2.3. Diclofenac Sodium Anhydrate

After dissolving anhydrous DIC-Na (ca. 50 mg) in a mixed acetonitrile–methanol (4:1 by volume, 5 mL) solvent, the solution was subsequently evaporated, resulting in needle-like anhydrous crystals.

2.3. Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD)

PXRD was performed using SmartLab (Rigaku, Japan) in the manner of transmission geometry. The data were collected from 2θ = 3° to 40° at an ambient temperature at step and scan speeds of 0.01° and 3°min−1, respectively, using a Cu Kα source (45 kV, 200 mA). The conditions for simultaneous PXRD and DSC measurements are discussed in Section 2.6.

2.4. Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD)

Single crystals of DIC-Na hydrates and anhydrate were prepared by the method described in Section 2.2, and the SCXRD data were collected using R-AXIS RAPID (Rigaku Tokyo, Japan) with Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71075 Å). Data reduction and correction were performed using RAPID-AUTO (Rigaku) with ABSCOR (T. Higashi Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). The space group was determined using PLATON [40]. The structure was solved using a dual-space algorithm of SHELXT [41] and then refined on F2 using SHELXL-2017/1 [42]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms attached to oxygen (water) and nitrogen atoms were found in the differential Fourier map. The water hydrogen atoms were refined using standard distance restraints and constrained isotropic thermal parameters. The hydrogen atoms attached to nitrogen were refined with lax distance restraints of 0.88 Å and thermal parameters set to 1.2 times those of the parent atom. Other hydrogen atoms were located in the geometrically calculated position and refined using the riding model. The 3D structures of the molecules were drawn using Mercury 4.3.1 [43].

2.5. Thermogravimetric (TG) Analysis

Thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) measurements were performed using a Thermo plus EVO (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). A sample of powdery 4.75H (7.856 mg) in an unsealed aluminum pan was heated at 5 °C min−1 up to 150 °C under flowing N2 gas (100 mL min−1).

2.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

PXRD and DSC measurements were performed simultaneously using an XRD-DSC (Rigaku, Japan) equipped with a D/tex Ultra detector and Cu Kα source (40 kV, 40 mA). A powdery sample of DIC-Na 4.75H was heated at +1 °C min−1 up to 120 °C in an unsealed Al pan with flowing N2 gas (100 mL min−1). The preliminary DSC measurement was performed up to 300 °C to confirm the absence of phase transformation over 150 °C (Figure S1, the Supplementary Materials).

2.7. Dynamic Vapor Sorption (DVS)

The critical relative humidity (RH) where the hydration of the anhydrous DIC-Na AH occurs was determined by dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) using a Dynamic Vapor Sorption Advantage instrument (Surface Measurement Systems Ltd., Wembley, UK) at 25 °C. The RH was increased from 0% to 90% and then decreased to 0% with a step width of 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Crystal Structure of DIC-Na Hydrates

The crystal structures of DIC-Na 4.75H, 3.5H, and AH were successfully analyzed by SCXRD, and the crystallographic data are shown in Table 1. The phase agreement between the solid powder samples obtained by the method described in Section 2.2 and the analyzed single crystals was confirmed by their PXRD patterns.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data of diclofenac sodium (DIC-Na) hydrates and anhydrate.

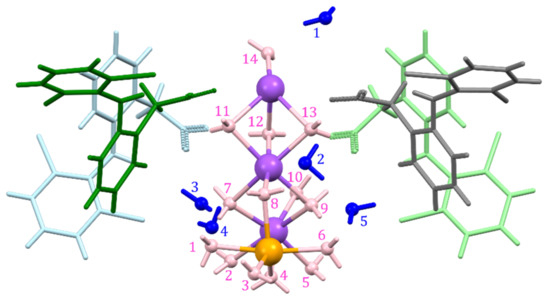

The lattice parameters of DIC-Na 4.75H shown in Table 2 are identical to those reported by Llinàs et al. (Table S1) [34]. The asymmetric unit contained four DIC anions and 19 water molecules (Figure 2). Na+ ions were surrounded by a large amount of water, and Na+ was coordinated to either six or five water molecules (6-coordination or 5-coordination, respectively), while DIC anions formed no coordination bonds with Na+ ions. Five of the 19 water molecules did not coordinate with Na+ ions and existed as crystalline water molecules in the crystal.

Figure 2.

Asymmetric unit of DIC-Na 4.75H, with fourteen bonded (pink) and five non-bonded (blue) water molecules and 6-coordinated (purple) and 5-coordinated (orange) Na+ ions.

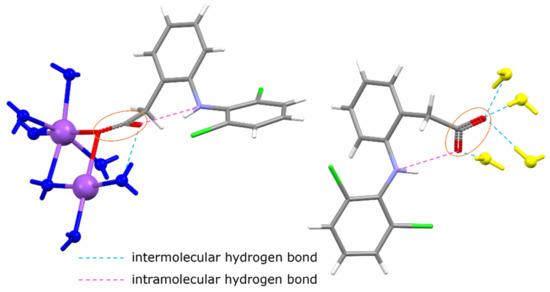

Similarly, the lattice parameters of DIC-Na 3.5H in Table 1 are the same as those reported by Nieto et al. (Table S1) [37]. DIC-Na 3.5H crystallized in the triclinic space group, and its asymmetric unit, consisted of two DIC anions, two Na+ cations, and seven water molecules (Figure 3). All water in the crystal was bound to Na+. One Na+ ion was coordinated to either five water oxygens and a carboxylate oxygen or to four water oxygens and two carboxylate oxygens of DIC, resulting in a 6-coordination configuration in both cases (Figure 4). Although the unit cell of 3.5H was relatively similar to that of 4.75H, its crystallographic symmetry was reduced from monoclinic to triclinic.

Figure 3.

Asymmetric unit of DIC-Na 3.5H (yellow water molecules are not included). One (left) DIC is connected to Na+ ions, but the other (right) forms hydrogen bonds with water and does not bond with Na+ ions.

Figure 4.

Coordination environment around Na+ ions in DIC-Na 3.5H. Na2 (purple) is connected to five H2O oxygens and one carboxylate oxygen, whereas Na1 (orange) bonds to four H2O oxygens and two carboxylate oxygens. However, in both cases, Na adopts a six-coordinated configuration.

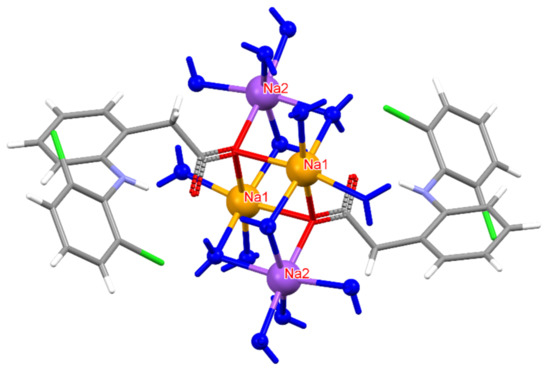

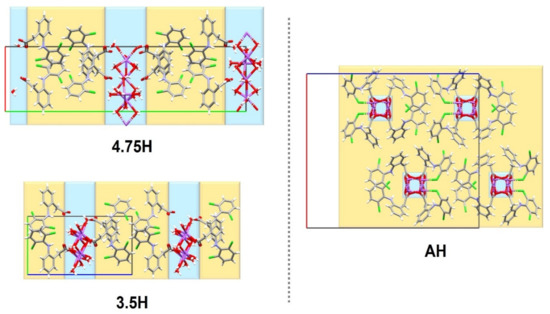

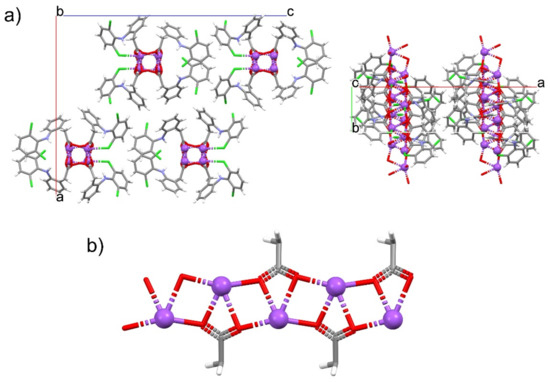

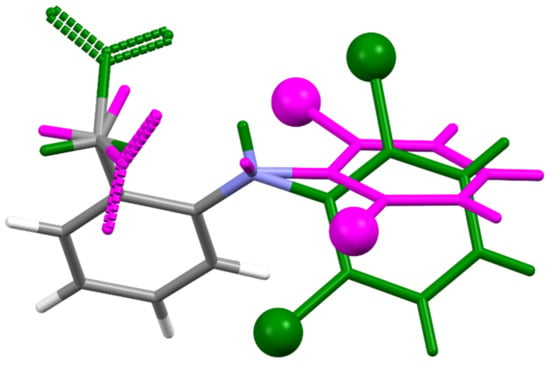

For the first time, this work elucidated the crystal structure of DIC-Na AH, which crystallizes into an orthorhombic system with the Pbca space group, wherein two DIC anions and sodium cations are independent (Figure 5). In contrast to 4.75H and 3.5H, AH does not show an alternating layered structure consisting of a hydrophilic region (Na+, water, and carboxylate) and hydrophobic region (the main part of DIC) (Figure 6). However, a one-dimensional hydrophilic Na–O chain structure appears along the b-axis in the AH crystal, where [Na–O]2 squares and [Na–OCO(carboxylate)] kites are connected alternately to form an infinite rigid chain (Figure 7). In the crystal structure, each Na+ ion is coordinated to five carboxylate oxygens (three monodentate carboxylates and one bidentate carboxylate) and adopts a 5-coordinated geometry. To visualize the conformational differences in the two independent DIC anions in the asymmetric unit, they are overlaid in Figure 8, which demonstrates great variation at the carboxylate moiety and the second aromatic ring with chlorine atoms.

Figure 5.

Asymmetric unit of DIC-Na AH.

Figure 6.

Structural comparison among unit cells of three DIC-Na hydrates.

Figure 7.

One-dimensional Na–O chain in DIC-Na AH. (a) Crystal packing diagrams viewed from the b- (left) and c-axes (right). (b) Infinite motif composed of Na–O–Na–O squares and Na–O–C–O kites.

Figure 8.

Structural overlay between two independent DIC molecules in DIC-Na AH shown in Figure 5.

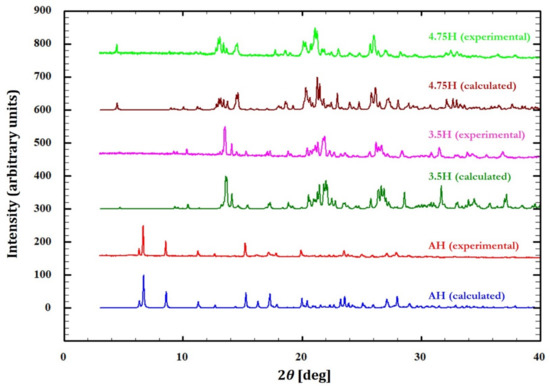

The consistency between the powdery materials used in subsequent experiments and the single-crystalline phases was confirmed using their PXRD patterns, and the patterns of the experimental samples were verified to be identical to those calculated from the crystal structure via Mercury 4.3.1 (Figure 9) [43].

Figure 9.

Experimental and calculated powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns for DIC-Na 4.75H, 3.5H, and AH forms.

3.2. Dehydration Behavior of DIC-Na 4.75H

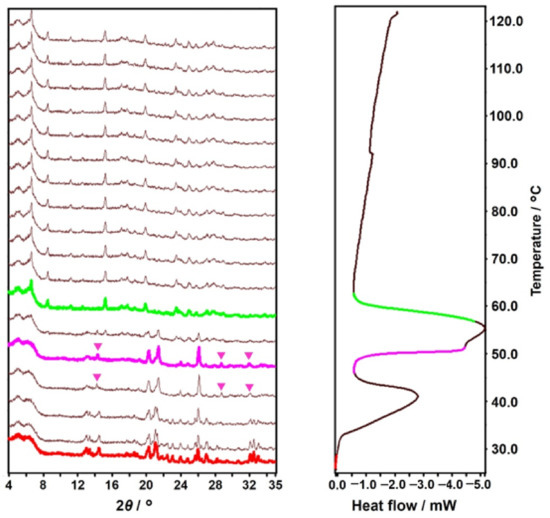

The dehydration of DIC-Na 4.75H was examined by simultaneous PXRD-DSC measurements, and the results are presented in Figure 10. The preliminary DSC measurement was performed up to 300 °C to show there was no change from the dehydration temperature (108.4 °C) to the melting point of DIC-Na (292.4 °C) (Figure S1). Therefore, the PXRD-DSC and the TG-DTA data (Figure 11) were collected up to 120 °C and 150 °C, respectively. The DSC curve showed two endothermic peaks corresponding to multi-step dehydration transitions. After the first transition, the PXRD pattern changed slightly, indicating the emergence of a hemi-heptahydrate phase (i.e., 3.5H). The second transition led to a distinct pattern derived from an anhydrous phase. Because the second peak bifurcated, the second dehydration may be a multi-step process, and 3.5H may transform into AH via intermediate phases.

Figure 10.

Simultaneously measured variable-temperature powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (left) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (right) diagrams. The colored PXRD patterns and segments in the DSC diagram correspond to the emergence of new phases.

Figure 11.

Thermogravimetric (TG) (left axis) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) (right axis) diagrams of DIC-Na 4.75H.

The TG-DTA curves in Figure 11 exhibit the dehydration behavior in further detail. Two DTA endothermic peaks appear. The first peak (42.2 °C) is accompanied by a 5.32% weight decrease, indicating partial dehydration (4.75 to 3.5, calculation: 5.58%), which is followed by the second peak (56.7 °C) with a 15.07% weight decrease, which corresponds to complete dehydration (3.5 to 0, calculation: 16.54%).

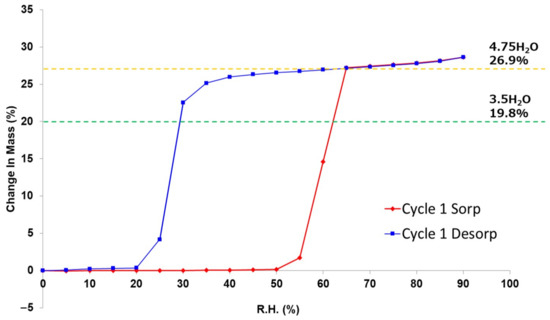

The DVS experiments performed at 25 °C revealed hysteresis between the water sorption and desorption processes (Figure 12). During the sorption process, AH started to absorb water at 60% RH and transformed into 4.75H at 65% RH. On the other hand, during the desorption process, 4.75H was almost stable down to 35% RH but started to desorb water at 30% RH and completely changed into AH at 30% RH. The intermediate 3.5H form (simulation: 19.8% mass change) was not observed during the desorption process.

Figure 12.

Dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) isotherm plot at 25 °C of DIC-Na anhydrate (AH).

4. Discussion

4.1. Verification of the Validity of the 4.75-Hydrate Crystal Structure

The published crystal structures of pentahydrate, 4.75H, and tetrahydrate have very similar lattice constants but different water contents. Moreover, the space group of 4.75H is P21, whereas those of the pentahydrate and tetrahydrate forms are both P21/m [33,35]. The crystal structure of DIC-Na 4.75H contains a pseudo-mirror plane between two corresponding DIC anions. However, the shape of the cluster of Na+ ions and water molecules is greatly distorted from the mirror symmetry, so it is not suitable to set the mirror plane on this cluster. The published pentahydrate structure was solved in the P21/m space group by employing a disordered model at the position of Na+ ions [33]. However, this assignment of the occupancy of disordered water may have been incorrect. The present study revealed that, in one unit cell, four DIC-Na molecules are associated with not 20 but 19 water molecules (4.75 water molecules for one DIC anion) in the hydrated solid state. Notably, the 4.75H structure model reported by Llinàs et al. was validated by a low R factor in their structural refinement [34].

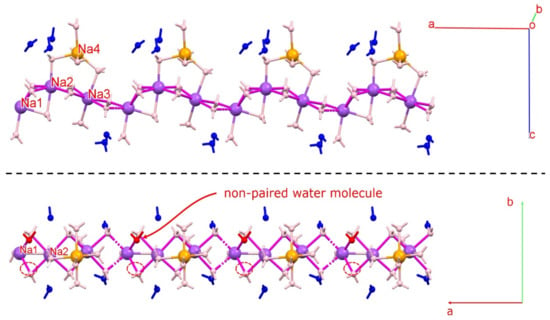

Figure 13 shows the Na–O coordination network observed in the crystal structure of DIC-Na 4.75H. Three 6-coordinated sodium ions (Na1, Na2, and Na3) form a waving [Na–O–Na–O] chain structure, while a 5-coordinated sodium ion (Na4, orange) is connected to the chain via water. The lower panel in Figure 13 displays the chain seen from the direction parallel to the pseudo-mirror plane. Although most atoms have a corresponding atom across the pseudo-mirror plane, one water molecule (red) does not. A different Fourier map exhibited a 0.36 eÅ−3 residual electron peak at the corresponding position, which might indicate a water oxygen. However, refining such a model was difficult because the occupancy factor decreased to less than 8%, and the position was unstable. Thus, we concluded that the residual error is not significant, and the phase contains 4.75 water molecules.

Figure 13.

Na–O chain observed in the crystal structure of 4.75H. Three 6-coordinated sodium ions (Na1, Na2, and Na3) form a waving [Na–O–Na–O] chain structure. Red water molecules do not have an associated atom across the pseudo-mirror plane (non-paired water molecule). Figures were drawn with crystallographic a, b, c-axis marks.

4.2. Hydration and Dehydration Mechanism 4.75H Crystal

DIC-Na AH sorbs water molecules and directly transforms into 4.75H, which does not include the 3.5H form. In contrast, DIC-Na 4.75H loses water and transforms first into 3.5H and then into AH. The difference between the hydration and dehydration behaviors can be explained based on the similarity of the crystal structures.

According to the DVS isotherm sorption plot (Figure 12, red), the DIC-Na AH form was stable in a humid environment up to 50% RH. However, it rapidly absorbed water to form DIC-Na 4.75H at 65% RH. The DIC-Na 3.5H form did not appear in the absorption process. This stoichiometric absorption behavior may be due to the large difference in the crystal structures between DIC-Na AH and 4.75H (Figure 6). In fact, the alternating layered structure of hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions in 3.5H and 4.75H forms was not observed in the AH form. Usually, a large hysteresis in the DVS isotherm plot (Figure 12) indicates a large difference in the crystalline structure. The AH form may be kinetically stable owing to such a difference that it did not rapidly change into hydrate phases. The hydration critical RH of 65% RH in the AH form exceeded the stable region of the 3.5H form (30 to 60% RH), which prevented the formation of 3.5H during the hydration of the AH form.

In the case of dehydration, the DVS isotherm desorption plot (Figure 12, blue) reveals that DIC-Na 4.75H was stable down to 65% RH. Then, it gradually released water and transitioned to 3.5H, which was stable between 65% and 30% RH. Below 30% RH, the 3.5H form rapidly when transformed to the AH form. The smooth dehydration from 4.75H to 3.5H can be explained by their similar crystal structure, with analogous hydrophilic/hydrophobic alternating layers (Figure 6). In the TG-DTA curve (Figure 11), which was recorded under flowing dry N2 gas, a partial stoichiometric weight loss (5.32%) confirmed the presence of 3.5H at approximately 50 °C. Similarly, the simultaneous PXRD-DSC measurements (Figure 10) showed the first dehydration step to generate 3.5H, and a few 2θ diffraction peaks revealing the presence of 3.5H were observed at 14°, 29°, and 32° (indicated by pink markers in Figure 10). Together, these results suggested a mechanistic aspect of this transition, namely that it was not until the crystal lattice of 4.75H could no longer accommodate the void structures formed during dehydration in which another lattice emerged, which corresponded to that of 3.5H. In this manner, the reported “tetrahydrate” structure with the same cell dimensions as 4.75H [35] might arise from the partial decrease in the occupancies of water molecules.

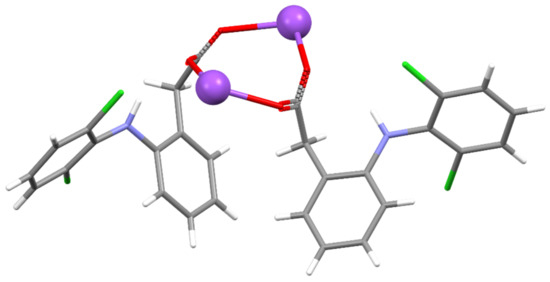

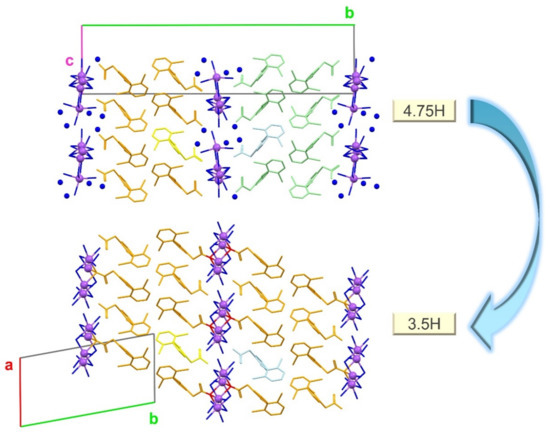

The change in the crystal structure from 4.75H to 3.5H is illustrated in Figure 14. Out of the 19 water molecules in the unit cell of 4.75H, the five that do not interact with Na+ were released during dehydration to form 3.5H (i.e., the ratio of water/DIC reduced from 19:4 (4.75) to 14:4 (3.5)). Thus, water molecules bonded to their surrounding molecules only through classical OH · · · O hydrogen bonds were preferentially lost by dehydration. This mechanism is consistent with the previous conjecture by Bartolomei et al. that some water molecules were tightly bound and immobile, while the others were highly mobile [36].

Figure 14.

Structural changes during the dehydration from 4.75H to 3.5H. Non-bonded water molecules are represented by blue spheres. Hydrogen atoms are omitted. Figures were drawn with crystallographic a, b, c-axis marks.

The release of five water molecules during the dehydration changed the coordination environment around Na+. The number of Na+ · · · O interactions is summarized in Table 2 with other crystallographic indices. During dehydration from 4.75H to 3.5H, the number of Na+ · · · O(water) interactions decreased, but new Na+ · · · O(carboxylate) interactions formed to compensate for this decrease, thereby maintaining either five or six Na+ · · · O(all) interactions per one Na+. This change in the Na+ coordination environment implies that the coordination of Na+ with O is flexible, allowing a smooth change in the coordinating atom from O(water) to O(carboxylate). In addition, a coordination number of 5 or 6 around Na+ in 4.75H is commonly observed, and more than 6-coordination is undesirable owing to steric hindrance [44].

During dehydration, the orientation of the DIC molecules changed. Both the 4.75H and 3.5H forms have hydrophobic DIC layer structures, but the directions of these layers differ. Specifically, the alternating layers in the crystal structure of 4.75H are oriented in the opposite direction (orange and light-green in Figure 14), whereas the layers in 3.5H are in the same direction (orange only). This change is highlighted by the yellow and light-blue molecules in Figure 14. During dehydration, the yellow molecule retained the same orientation in both structures, but the light blue one rotated. This rotation may have facilitated the breaking and formation of Na+ · · · O (water or carboxylate) interactions associated with structural reconstruction.

A large rearrangement in the crystal structure of the AH form was observed below 30% RH. During this change, the hydrophilic/hydrophobic alternating-layer structure disappeared, and a one-dimensional chain structure of hydrophilic (Na+ and O) formed along the b-axis (Figure 7). Although this change was large, O(carboxylate) atoms almost maintained the Na+ coordination number at five. The packing indices (Table 2) were calculated using the PLATON program [40]. The packing index of 4.75H is slightly lower than that of 3.5H, possibly due to a small void space (ca. 5.9 Å3 × 2), which would explain why the slightly unstable 4.75H starts to dehydrate to 3.5H, even in the high RH region. Meanwhile, compared with AH, the 3.5H form is more efficiently packed, utilizes a greater number of H-bonds, and has more water molecules filling spaces.

Table 2.

Number of Na+–O interactions and packing indices.

Table 2.

Number of Na+–O interactions and packing indices.

| 4.75H | 3.5H | AH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of water molecules per four DIC molecules | 19 | 14 | 0 |

| Na+–O(all) interactions | 6 or 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Na+–O(water) interactions | 6 or 5 | 5 or 4 | 0 |

| Na+–O(carboxylate) interactions | 0 | 1 or 2 | 5 |

| Packing index | 70.3 | 73.3 | 71.9 |

5. Conclusions

The novel crystalline phase of DIC-Na AH was revealed by SCXRD. The re-determination of the crystal structure and crystallographic investigation of 4.75H showed that the presence of non-coordinated water molecules caused pseudo-symmetry and structural complexity. The multi-step dehydration mechanism of DIC-Na 4.75H was successfully elucidated using simultaneous PXRD-DSC, TG, and DVS, as well as a comparison of the crystal structures. During the first dehydration step, only water molecules that were not coordinated to Na+ ions were lost, which led to the generation of 3.5H. The second dehydration step into the anhydrous phase (AH) was accompanied by a large structural change. For the first time, this work successfully elucidated the solid-state dehydration transition landscape of DIC-Na, which is a commercially available form of this API, using X-ray crystallographic analysis. These findings help understand the dehydration/hydration mechanism as well as the physicochemical properties of pharmaceutical crystals.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst11040412/s1, Figure S1: DSC diagram of DIC-Na 4.75H, Table S1: Crystal structures of diclofenac sodium (DIC-Na) hydrates published thus far.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.O., T.M. and H.U. Structural analysis, H.O. and T.M. Investigation, H.O., T.M. and I.N. Writing—original draft preparation, H.O. and T.M. Writing—review and editing, H.O., A.S. and H.U. Visualization, H.O. Supervision, A.S. and H.U. Project administration, H.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18H04504 and 20H04661 (H.U.).

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2065083, 2065085, and 2065086 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper (3.5H, 4.75H, and AH, respectively). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Etsuo Yonemochi (Hoshi University) for the DVS measurement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Leuner, C.; Dressman, J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Müller, F.; Huang, S.; Lowinger, M.; Liu, X.; Schooler, R.; Williams, R.O., III. Influence of Carbamazepine Dihydrate on the Preparation of Amorphous Solid Dispersions by Hot Melt Extrusion. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikas, Y.; Sandeep, K.; Braham, D.; Manjusha, C.; Budhwar, V. Cyclodextrin complexes: An approach to improve the physi-cochemical properties of drugs and applications of cyclodextrin complexes. Asian J. Pharm. 2018, 12, S394. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H.; Sun, Y.-B.; Zhou, J.-W.; Xie, M.-J.; Lin, H.; Yong, Y.; Chen, L.-Z.; Fang, B.-H. Pharmaceutical Salts of Enrofloxacin with Organic Acids. Crystals 2020, 10, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Jafari, M.; Padrela, L.; Walker, G.M.; Croker, D.M. Creating Cocrystals: A Review of Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Preparation Routes and Applications. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 6370–6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, S.L.; Chyall, L.J.; Dunlap, J.T.; Smolenskaya, V.N.; Stahly, B.C.; Stahly, G.P. Crystal Engineering Approach to Forming Cocrystals of Amine Hydrochlorides with Organic Acids. Molecular Complexes of Fluoxetine Hydrochloride with Benzoic, Succinic, and Fumaric Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13335–13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, N.; Tanida, S.; Nakae, S.; Shiraki, K.; Tozuka, Y.; Ishigai, M. Tofogliflozin Salt Cocrystals with Sodium Acetate and Potassium Acetate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 66, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Bu, F.-Z.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Yan, C.-W. A Sulfathiazole–Amantadine Hydrochloride Cocrystal: The First Codrug Simultaneously Comprising Antiviral and Antibacterial Components. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 3236–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.L. Salt selection for basic drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 1986, 33, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serajuddin, A.T.M. Salt formation to improve drug solubility. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulekuhn, G.S.; Dressman, J.B.; Saal, C. Trends in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Salt Selection based on Analysis of the Orange Book Database. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 6665–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzidic, I.; Kebarle, P. Hydration of the alkali ions in the gas phase. Enthalpies and entropies of reactions M+(H2O)n−1 + H2O = M+(H2O)n. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, G.A.; Diseroad, B.A. Structural relationship and desolvation behavior of cromolyn, cefazolin and fenoprofen sodium hydrates. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 198, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Bhatt, P.M.; Kirchner, M.T.; Desiraju, G.R. Structural studies of the system Na(saccharinate)·nH2O: A model for crystallization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2515–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.D.; Cornett, C.; Larsen, F.H.; Qu, H.; Raijada, D.; Rantanen, J. Structural basis for the transformation pathways of the sodium naproxen anhydrate-hydrate system. IUCrJ 2014, 1, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dračínský, M.; Šála, M.; Hodgkinson, P. Dynamics of water molecules and sodium ions in solid hydrates of nucleotides. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 6756–6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberg, E.T.; Campbell, P.S.; Szeto, K.C.; Mallick, B.; Schaumann, J.; Mudring, A. Sodium Salicylate: An In-Depth Thermal and Photophysical Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 15638–15648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, H.S.; Chaturvedi, K.; Zeller, M.; Bates, S.; Morris, K. A threefold superstructure of the anti-epileptic drug phenytoin sodium as a mixed methanol solvate hydrate. Acta Cryst. 2019, C75, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.; Su, W.; Huang, X.; Tian, B.; Cheng, X.; Mao, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, H.; Hao, H. Understanding the Role of Water in Different Solid Forms of Avibactam Sodium and Its Affecting Mechanism. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Aoki, M.; Uekusa, H. Solid-State Hydration/Dehydration of Erythromycin an Investigated by ab Initio Powder X-ray Diffraction Analysis: Stoichiometric and Nonstoichiometric Dehydrated Hydrate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 2060–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi, R.; Uekusa, H. Elucidating the Dehydration Mechanism of Ondansetron Hydrochloride Dihydrate with a Crystal Structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 6142–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesser, U.J. The Importance of Solvates. In Polymorphism in the Pharmaceutical Industry; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; pp. 211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Jurczak, E.; Mazurek, A.H.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Pisklak, D.M.; Zielińska-Pisklak, M. Pharmaceutical Hydrates Analysis—Overview of Methods and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietveld, I.B.; Céolin, R. Rotigotine: Unexpected Polymorphism with Predictable Overall Monotropic Behavior. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 4117–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, K.; Uekusa, H.; Itoda, N.; Hasegawa, G.; Yonemochi, E.; Terada, K.; Pan, Z.; Harris, K.D.M. Physicochemical under-standing of polymorphism and solid-state dehydration/rehydration processes for the pharmaceutical material acrinol, by ab initio powder X-ray diffraction analysis and other techniques. J. Phys. Chem. 2010, 114, 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T.; Terada, K. Elucidation of the crystal structure-physicochemical property relationship among polymorphs and hydrates of sitafloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone antibiotic. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 422, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomane, K.S.; More, P.K.; Raghavendra, G.; Bansal, A.K. Molecular understanding of the compaction behavior of indo-methacin polymorphs. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Grant, D.J.W. Crystal structures of drugs: Advances in determination, prediction and engineering. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakon, A.; Sekine, A.; Uekusa, H. Powder Structure Analysis of Vapochromic Quinolone Antibacterial Agent Crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 4635–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, O.D.; Pettersen, A.; Yonemochi, E.; Uekusa, H. Structural origin of physicochemical properties differences upon de-hydration and polymorphic transformation of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride revealed by structure determination from powder X-ray diffraction data. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2020, 22, 7272–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skomski, D.; Varsolona, R.J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Teller, R.; Forster, S.P.; Barrett, S.E.; Xu, W. Islatravir Case Study for Enhanced Screening of Thermodynamically Stable Crystalline Anhydrate Phases in Pharmaceutical Process Development by Hot Melt Extrusion. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2874–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, T.; Ramachandran, C.; Bermejo, M.; Yamashita, S.; Yu, L.X.; Amidon, G.L. A provisional biopharmaceutical classification of the top 200 oral drug products in the United States, Great Britain, Spain and Japan. Mol. Pharm. 2006, 3, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangsin, N.; Prajaubsook, M.; Chaichit, N.; Siritaedmukul, K.; Hannongbua, S. Crystal Structure of a Unique Sodium Distorted Linkage in Diclofenac Sodium Pentahydrate. Anal. Sci. 2002, 18, 967–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinàs, A.; Burley, J.C.; Box, K.J.; Glen, R.C.; Goodman, J.M. Diclofenac Solubility: Independent Determination of the Intrinsic Solubility of Three Crystal Forms. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, G.; Faust, G.; Dietz, G. X-ray crystallographic studies of diclofenac-sodium—Structural analysis of diclofenac-sodium tetrahydrate. Die Pharm. 1988, 43, 771–774. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei, M.; Rodomonte, A.; Antoniella, E.; Minelli, G.; Bertocchi, P. Hydrate modifications of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac sodium: Solid-state characterisation of a trihydrate form. J. Pharm. Biochem. Anal. 2007, 45, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, I.A.; Bernès, S.; Pérez-Benítez, A. Crystal structure of a new hydrate form of the NSAID sodium diclofenac. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2020, 76, 1846–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.R.; Shah, Z.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, A.; Sohani; Hussain, J.; Csuk, R.; Anwar, M.U.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sodium, Potassium, and Lithium Complexes of Phenanthroline and Diclofenac: First Report on Anticancer Studies. ACS Omega 2019, 25, 21559–21566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugrahani, I.; Kumalasari, R.A.; Auli, W.N.; Horikawa, A.; Uekusa, H. Salt Cocrystal of Diclofenac Sodium-L-Proline: Structural, Pseudopolymorphism, and Pharmaceutics Performance Study. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, D65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifen, J.J.; Agmon, N. Structure and Spectroscopy of Hydrated Sodium Ions at Different Temperatures and the Cluster Stability Rules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 1656–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).