Abstract

To address the challenges of zwitterionic dissociation and steric hindrance in the esterification of α-aromatic amino acids, this study prepared the solid superacid catalyst SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 (STH) and its plasma-modified derivative SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 (STH-RF) via an aging-impregnation method. Systematic characterization revealed that plasma modification optimizes the crystal morphology and particle dispersion of the catalyst, while also achieving pore clearance and an increase in the specific surface area. Furthermore, it gradationally enhances acidic properties by increasing the abundance of strong acid and Lewis acid sites, and promotes uniform loading and stable bonding of the SO42− active component. Performance evaluation using the synthesis of L-phenylalanine methyl ester as a model reaction demonstrated that STH-RF exhibits optimal catalytic activity, affording a product yield of 85.7%, which is significantly higher than that of unmodified STH (19%) and the homogeneous catalyst H2SO4 (63%). This superior performance originates from a “structure–acidity” synergistic effect, combining the thermodynamic advantage of a lower energy barrier for the rate-determining step (12.6 Kcal·mol−1) with efficient kinetics under optimal process conditions (1.0 MPa, 2000 rpm, 170 °C). Moreover, STH-RF maintained a yield above 80% after four consecutive reaction cycles, indicating excellent stability. This work provides a novel catalytic system for the green and efficient synthesis of highly hindered α-amino acid derivatives, holding significant theoretical and practical implications.

1. Introduction

α-Amino acids are a class of important organic compounds with special spatial structures and electronic effects, serving as the defining subunits of peptides and proteins [1]. Among them, sterically hindered α-amino acids, especially aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) [2], exhibit unique values in the fields of biomedicine and chiral materials due to the steric hindrance effect of substituents on the α-carbon [3,4]. α-Amino acid derivatives, which retain the core skeleton of α-amino acids [5], are key molecules linking organic synthesis and functional applications. Among these, α-aromatic amino acid esters, as a type of amino acid ester compounds, are important building blocks for drugs, sweeteners, and fluorescent sensors [6]. L-phenylalanine methyl ester is a typical α-aromatic amino acid ester. Its molecular structure simultaneously possesses the hydrophobic aromaticity of the benzene ring, the electrophilicity of the ester group, and the nucleophilicity of α-amino acids. The L-configuration of L-phenylalanine methyl ester matches the chirality of natural amino acids, endowing it with good compatibility and recognizability in biological systems.

In terms of synthetic strategies, the synthesis of L-phenylalanine methyl ester can effectively protect the carboxyl group in L-phenylalanine [7], which can avoid unknown by-products caused by the activation of the carboxyl group and prevent the reaction between the amino group and carboxyl group of amino acids. In the reported studies on α-amino acid esterification reactions, this reaction usually needs to be completed under the catalysis of acidic catalysts [8]. The core principle of the esterification is that the carboxyl group is activated by acid catalysis, promoting the nucleophilic addition reaction between the protonated carboxyl group of α-amino acids and alcohol substrates [9], thereby generating the target amino acid ester products. Acidic catalysts are mainly divided into homogeneous catalysts (such as sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid) and heterogeneous catalysts (such as solid superacids) [10,11]. Heterogeneous catalysts stand out in liquid-phase organic synthesis reactions due to their ease of recovery, reusability, and effective avoidance of corrosion problems.

It should be noted that the esterification of α-aromatic amino acids needs to overcome the limitations imposed by amphoteric dissociation and steric hindrance effects [6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new high-efficiency catalysts with stronger acidity to promote the esterification reaction of α-aromatic amino acids. Among them, solid superacids, as catalysts with acidity far exceeding that of liquid strong acids and traditional solid acids [12], are efficient catalysts for the carboxylic acid esterification reaction of α-aromatic amino acids. The surface of TiO2 is rich in Ti4+ active sites, which can form stable coordination structures with anions such as SO42−, significantly enhancing the acid strength and acid site density of the catalyst [13]. On the other hand, TiO2 exhibits excellent chemical and thermal stability, capable of maintaining structural integrity during the high-temperature calcination process for catalyst preparation and repeated catalytic cycles [14].

Among various solid acid supports, HZSM-5 zeolite has been extensively applied in the field of heterogeneous catalysis due to its ordered microporous system, tunable acidity, and excellent hydrothermal stability [15,16]. Existing studies have confirmed that the mass transfer efficiency of HZSM-5 toward bulky substrates can be improved by regulating its Si/Al ratio, modifying the pore channels, or loading active components [17,18], thus enabling its application in the esterification, alkylation and other reactions of aromatic compounds. Parmar et al. [19] used ZSM-5 and HZSM-5 as catalysts to synthesize succinic acid and ethanol, and the conversion rates of succinic acid were 79% and 94% respectively.

To further optimize the catalytic performance of solid superacids, various modification technologies have been extensively investigated. Among these approaches, plasma modification [20] has attracted considerable attention from researchers owing to its advantages of mild operation, environmental friendliness, and precise regulation of catalyst surface properties. Numerous studies have confirmed that plasma modification can effectively modulate the physicochemical properties and catalytic performance of catalysts [21]. Jung et al. [22] treated TiO2 thin films with radio frequency (RF) plasma to improve their photocatalytic activity. They found that plasma treatment optimized the surface morphology and mass transfer of the material, regulated its surface electronic structure and active sites, inhibited carrier recombination, and enhanced catalytic activity. Raziyeh et al. [23] successfully regulated the surface activity of HZSM-5/TiO2 catalysts via plasma modification, thereby enhancing the removal efficiency of toluene vapor by the catalysts. Despite the significant advantages of plasma modification in similar catalytic systems, systematic reports on its application in modifying SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 composite catalysts to strengthen the catalytic performance for α-aromatic amino acid esterification are still lacking, which endows the design of this study with certain novelty and exploratory value.

From a physicochemical perspective, high-energy particles such as electrons and ions in plasma can bombard the catalyst surface [24], breaking some chemical bonds on the support surface. This introduces a large number of defect sites and unsaturated coordinated metal cations (e.g., Ti4+ and Al3+), which can provide more active sites for the anchoring of SO42−. In addition, the activation effect of plasma can promote the uniform dispersion of SO42− on the catalyst surface [25], avoiding the shielding of acid sites caused by the agglomeration of active components and improving the accessibility of acid sites.

In this study, a novel green solid superacid catalyst SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 was prepared by the aging-impregnation method combined with plasma modification technology. The catalytic performance of the catalyst before and after plasma modification for the esterification reaction of L-phenylalanine was systematically investigated. The effects of process parameters such as reaction temperature, stirring speed, and reaction pressure on the target esterification reaction were focused on. Meanwhile, the acidic characteristics (acid strength, acid amount, and acid type) of the catalyst were comprehensively characterized, and its cyclic performance was evaluated. This study provides a new catalytic system and technical reference for the green and efficient synthesis of L-phenylalanine ester compounds, and has important theoretical research value and practical application prospects.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Catalyst Structure and Acidic Properties

2.1.1. Control of Crystal Structure and Dispersion

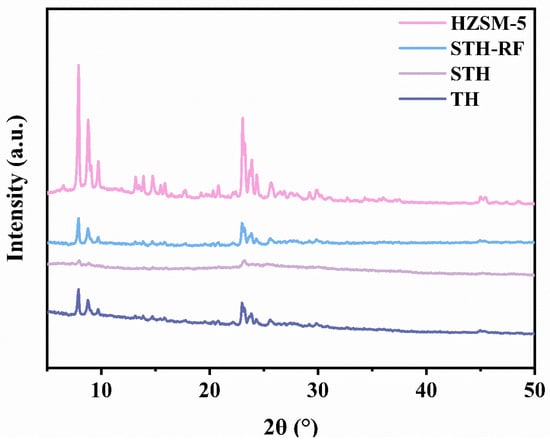

The XRD patterns of the catalysts (Figure 1) reveal that the TH precursor exhibits characteristic diffraction peaks of the HZSM-5 zeolite. The anatase phase of TiO2 at 2θ ≈ 10° and 20°, respectively, indicating the successful loading of TiO2 and the formation of a stable crystalline phase [26]. After SO42− loading, the diffraction peaks of the STH show decreased intensity and broadening. This is attributed to the deposition of SO42− species on the carrier surface, which covers part of the crystalline facets and reduces the degree of crystalline order [27]. In contrast, for the STH-RF treated with radio-frequency (RF) plasma, the diffraction peak intensity recovers significantly with sharper profiles. This improvement is attributed to the plasma treatment promoting the uniform dispersion of SO42− species through multiple mechanisms. The high-energy particles generated by the plasma impact the carrier surface, which can break SO42− aggregates and suppress their agglomeration by modulating the surface charge. Concurrently, plasma-induced surface defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies) and the increased specific surface area provide more anchoring sites for SO42−, reducing local accumulation. Furthermore, the energy input from the plasma optimizes the coordination environment between SO42− and the support, lowering the surface migration energy barrier of SO42−. Consequently, this reduces their coverage on the crystalline structure and enhances the crystalline stability of the support [28,29,30]. This modulation of the crystal structure lays the structural foundation for the subsequent formation and exposure of acidic sites.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of catalysts.

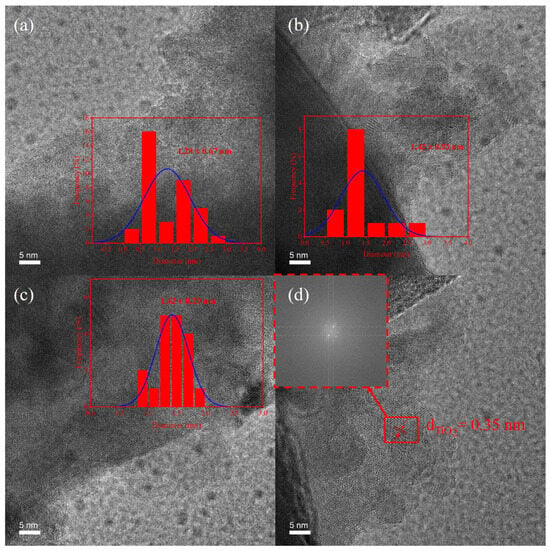

The microstructural characteristics of the TH, STH, and STH-RF samples are presented in Figure 2. Figure 2a–c display the morphological features and particle size statistics of the samples. For the TH sample (Figure 2a), it exhibits a broad particle size distribution with an average particle size of 1.28 ± 0.67 nm, indicating poor particle uniformity. As shown in Figure 2b, the modified STH sample has an average particle size of 1.42 ± 0.53 nm, with its particle uniformity significantly improved. After further regulation, the STH-RF sample Figure 2c shows the most concentrated particle size distribution, with an average particle size of 1.42 ± 0.29 nm. These results demonstrate that the modification process effectively enhances the particle dispersibility and size uniformity [31]. The STH-RF sample in Figure 2d reveals a lattice spacing of 0.35 nm, which matches well with the characteristic parameter of the anatase TiO2 (101) crystal plane [32]. These characterization results clarify the regulatory effect of modification on the sample microstructure, laying a solid experimental foundation for subsequent investigations into the correlation between material properties and structure.

Figure 2.

TEM images with corresponding particle size distribution statistics of (a) TH, (b) STH, (c) STH-RF; and (d) HRTEM image of STH-RF.

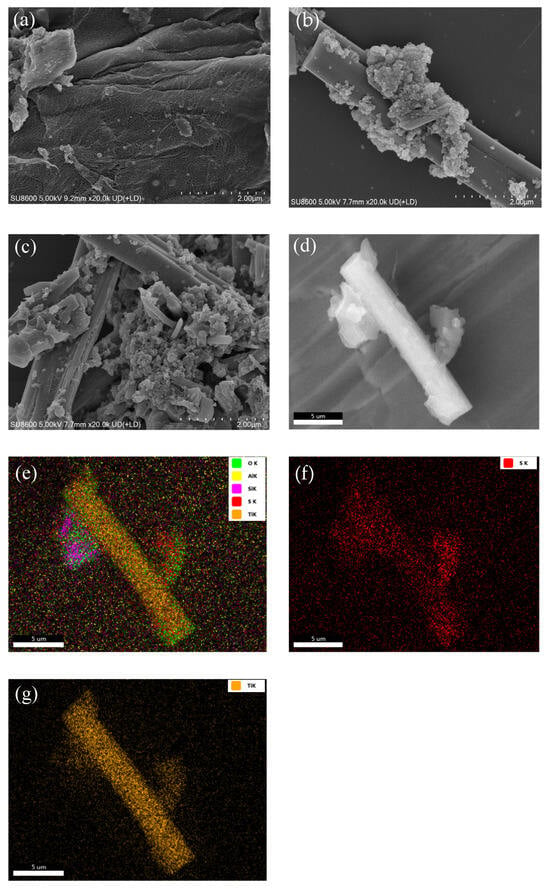

Figure 3 presents the SEM morphologies of the TH, STH, and STH-RF samples at a 2 μm scale, along with the elemental distribution characteristics of STH-RF. Figure 3a shows the unmodified TH sample, which exhibits a dense layered structure with a smooth surface and only a small number of fine particles, consistent with the initial morphology of the base material. In Figure 3b, the initially modified STH sample displays distinct particle aggregates on its surface, partially obscuring the original layered structure, reflecting the morphological modulation induced by the introduction of modified components. Figure 3c illustrates the further regulated STH-RF sample, which features a significantly higher density of surface particle aggregates with more uniform particle sizes, indicating an increased loading level of the modified components. Figure 3d–g provide the elemental mapping results of STH-RF, revealing a continuous and homogeneous distribution of C, Ti, and O elements within local regions. This finding confirms the absence of component segregation during the modification process, thereby ensuring uniform distribution of active sites across the material surface. Taken together, these results confirm that the modification process successfully tailors the surface morphology and achieves homogeneous component distribution. This outcome lays a solid structural foundation for optimizing the material’s performance [33].

Figure 3.

SEM images of (a) TH, (b) STH, (c) STH-RF; and (d–g) Elemental mapping analysis of STH-RF.

2.1.2. Optimization of Pore Structure and Mass Transfer Efficiency

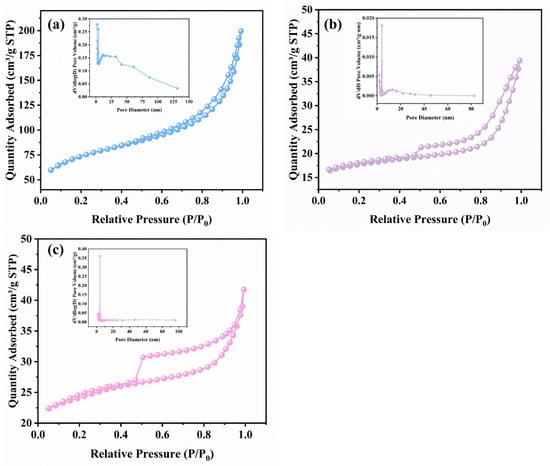

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (Figure 4, Table 1) and pore structure parameters indicate that all samples exhibit Type IV isotherms, corresponding to mesoporous structural characteristics. The TH possesses a relatively high specific surface area (244.45 m2/g) and pore volume (0.28 cm3/g), featuring a mixed pore system with an average pore diameter of 6.09 nm. This is consistent with the higher N2 adsorption capacity observed in Figure 4a, providing sufficient space for reactant adsorption and diffusion [33]. However, due to the absence of introduced SO42− active sites, its esterification activity remains limited. For the SO42−-modified STH, the loading of active species partially blocks the pores, reducing the specific surface area to 55.35 m2/g and shrinking the pore volume to 0.04 cm3/g. Although active sites are introduced, the deteriorated pore structure restricts mass transfer efficiency, preventing the esterification on activity from reaching an optimal level.

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution: (a) TH; (b) STH; (c) STH-RF.

Table 1.

Specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size parameters of different catalysts.

After radio-frequency plasma modification, the BET specific surface area of STH-RF increased to 76.15 m2/g, and the average pore diameter was refined to 5.00 nm. This structural evolution can be observed in Figure 4c, which shows a slight increase in nitrogen adsorption capacity and a notably concentrated pore size distribution. These results indicate that the plasma treatment enhanced the specific surface area by regulating particle dispersion and optimized the pore geometry while preserving the SO42− active sites. The synergy between the active sites and the modified pore structure effectively enhanced the accessibility of reactive sites and improved the mass transfer efficiency of reactants/products, thereby contributing to the optimal catalytic performance of this catalyst in the esterification of phenylalanine.

2.1.3. Gradational Enhancement of Acidic Properties

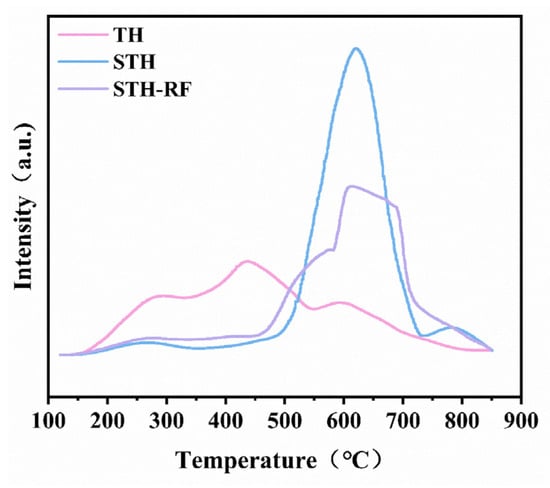

The NH3-TPD profiles (Figure 5) and the acid quantity distribution data (Table 2) reveal distinct acidic properties for the TH, STH, and STH-RF catalysts. Specifically, TH exhibits the weakest and broadest desorption signal. Its acid sites originate from the HZSM-5 zeolite framework and are distributed across weak, medium-strength, and strong acid regions. The corresponding total acid amount is only 1.150 mmol/g, indicating low acid density and strength. After modification, STH shows a significantly enhanced desorption signal with a concentrated peak in the medium-strength acid region (360–730 °C) [34,35]. The total acid amount increases to 1.658 mmol/g, with medium-strength acid sites becoming predominant. This confirms that the modification effectively introduces abundant medium-strength acid sites [36].

Figure 5.

NH3-TPD profiles of TH, STH, and STH-RF catalysts.

Table 2.

Acid Amount Distribution of TH, STH and STH-RF Catalysts from NH3-TPD.

Following plasma treatment, the total acid amount of STH-RF slightly decreases to 1.377 mmol/g. However, its desorption signal in the strong acid region (450–850 °C) becomes sharper and more concentrated. The acid sites are enriched in the strong acid region with an optimized distribution. Notably, although STH possesses a slightly higher total acid amount (1.658 mmol/g) than STH-RF (1.377 mmol/g), the acid sites of STH-RF are more concentrated in the strong acid region. The plasma modification further improves the accessibility and dispersion of these acid sites. This acidic characteristic aligns well with the requirement for strong acid sites in the esterification of L-phenylalanine—where strong acid sites are crucial for efficient carboxyl group activation. Concurrently, it helps avoid potential side reactions that may be promoted by an excess of medium-strength sites in STH. Consequently, these factors endow STH-RF with superior catalytic activity and selectivity [33,37].

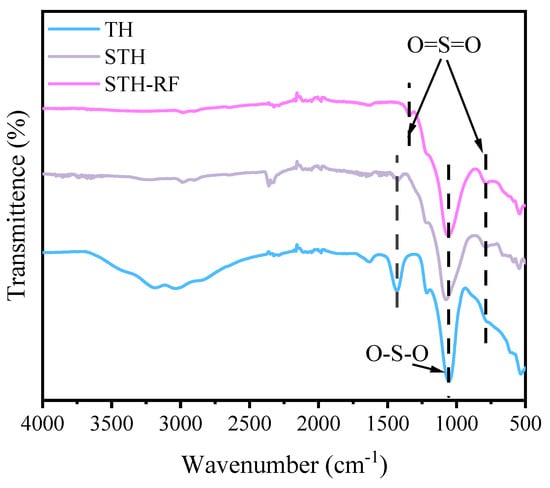

The FT-IR spectra of all catalysts are illustrated in Figure 6. The absorption peaks in the wavenumber range of 3500–2800 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of surface Si–OH and Ti–OH groups in the TH sample [38]. In contrast, this characteristic absorption signal was not detected in the STH and STH-RF samples, which can be ascribed to the impregnation of concentrated H2SO4 followed by high-temperature calcination [39]. Specifically, the strongly acidic H2SO4 undergoes esterification with surface -OH groups, resulting in the efficient consumption of Si–OH and Ti–OH species. Subsequent calcination at 450 °C further promotes the dehydration condensation of residual -OH groups, ultimately leading to the complete elimination of surface -OH and adsorbed water. This phenomenon adequately explains the absence of absorption peaks in the aforementioned spectral region. The absorption peaks in the 1300–1000 cm−1 range are primarily attributed to the framework vibrations of HZSM-5 molecular sieves [40], coupled with the asymmetric stretching vibrations of O=S=O bonds formed via the coordination of SO42− anions with surface Ti4+ [41]. These results demonstrate the successful immobilization of SO42− active components on the STH and STH-RF supports. Coordination of SO42− with the metal cations (e.g., Ti4+) in the support leads to the formation of S–OH bonds, whose dissociation generates H+, thereby creating Brønsted acid sites. Additionally, the intense absorption peak in the 800–500 cm−1 range is assigned to the stretching vibrations of Ti–O bonds within the TiO2 metal oxide phase [42]. This indicates the preservation of the TiO2 crystalline structure. Collectively, FT-IR results indicate that the TH support has abundant surface -OH. After concentrated H2SO4 loading and calcination, STH and STH-RF lose all surface -OH and successfully introduce SO42− active components (forming solid superacid sites), while the HZSM-5 framework and TiO2 structure remain stable in all samples.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of TH, STH, and STH-RF catalysts.

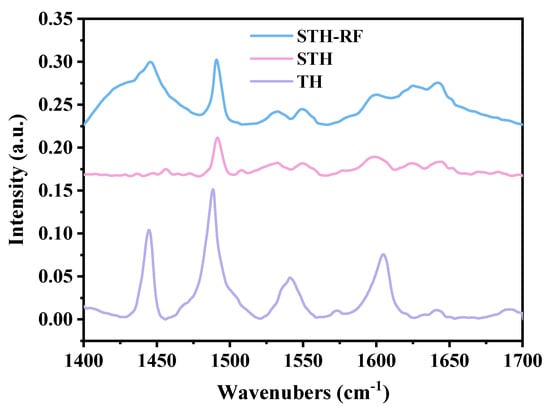

Pyridine infrared spectroscopy (Figure 7) clearly reveals the distribution characteristics of Brønsted acid (BA) sites and Lewis acid sites on the catalyst surface. STH-RF displays strong absorption bands at 1450 cm−1 (Lewis acid sites) and 1500 cm−1 (total acid sites), with significantly higher abundance and intensity of acid sites than STH and TH. STH shows only a weak band at 1500 cm−1, while the characteristic peaks of TH are extremely faint [43]. The correlation with catalytic performance indicates that the abundant Lewis acid sites provide sufficient active centers for the esterification reaction, which is a key structural factor responsible for the optimal catalytic efficiency of STH-RF. This result complements the strong-acid advantage revealed by NH3-TPD, together illustrating that plasma modification markedly enhances the acidic properties of the catalyst by optimizing the synergistic distribution of acid type, strength, and quantity [44] (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Py-IR spectra of TH, STH, and STH-RF.

Table 3.

The density analysis of BA and LA over the solid superacid by Py-IR measurement.

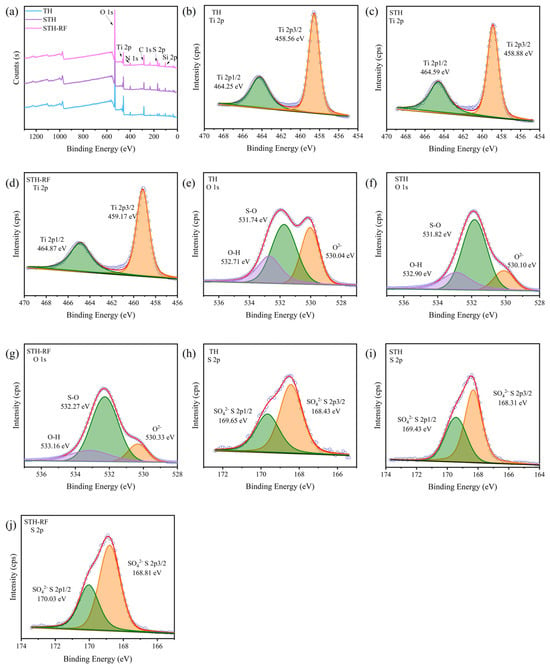

The XPS characteristic spectra of the TH, STH, and STH-RF samples are shown in Figure 8. As clearly observed in Figure 8a, all three samples contain Ti, O, and S elements. Notably, the signal intensity of the characteristic S peak in the STH and STH-RF samples is significantly higher than that in the TH sample, confirming that the modification treatment achieved the directional loading of sulfate ions on the carrier surface. Analysis of the Ti 2p spectra Figure 8b–d reveals characteristic double peaks for Ti4+, corresponding to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals in all three samples [45]. Compared to TH and STH samples, the Ti binding energy in STH-RF samples increased, reducing the electron density around Ti atoms. This enhances the electron-deficient nature of Ti4+ ions, thereby boosting their catalytic activity as Lewis acid centers [46]. Figure 8e–g display the O 1s spectra of the catalysts. The oxygen elements in the TH, STH, and STH-RF samples all fit into three characteristic peaks, corresponding to lattice oxygen (O2−), oxygen in sulfate ions (S–O), and surface hydroxyl oxygen (-OH) [47]. The S–O bond peak shows the largest area proportion, clearly indicating that the introduced sulfate ions have formed stable and abundant chemical bonds with the support surface. This further confirms that sulfate species constitute a significant proportion in the samples. Concurrently, the STH-RF sample exhibits a higher proportion of surface -OH compared to the TH and STH samples, demonstrating the effective regulation of surface-active sites through the modification process.

Figure 8.

XPS Spectra of TH, STH, and STH-RF: (a) Survey Spectrum; Ti 2p spectra of (b) TH, (c) STH, (d) STH-RF; O 1s spectra of (e) TH, (f) STH, (g) STH-RF; S 2p spectra of (h) TH, (i) STH, (j) STH-RF. Note: little circles represent acquired curves and lines represent fitted curves.

As shown in the S 2p spectra Figure 8h–j, the TH sample exhibits only the characteristic double peak of residual SO42− from the raw material. In contrast, both the STH and STH-RF samples display the characteristic double peak of modified SO42−, corresponding to the spin-split signals of the S 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals [48]. Furthermore, the S 2p characteristic peaks of the STH-RF sample exhibited narrower linewidths and higher intensities, indicating more uniform sulfate loading and higher content. In summary, XPS results confirm the successful sulfate modification of TiO2, which enhances both loading and uniformity while preserving structural stability. This optimization lays a solid foundation for improving the material’s acid catalytic performance.

2.2. Catalytic Performance and Structure–Acidity Relationship

2.2.1. Performance Variation of Different Catalysts

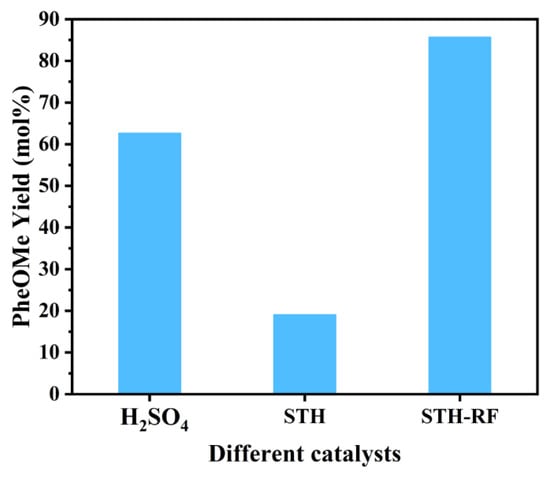

The comparative yields of PheOMe over the three catalysts (Figure 9) are as follows: approximately 63% for the H2SO4 catalytic system, a significant decrease to 19% for STH, and a high yield of 85.7% for the STH-RF catalytic system, demonstrating its optimal catalytic activity. Although STH possesses strong acid sites, its textural characteristics—such as low specific surface area and small pore volume—not only limit the accessibility of active sites and the mass transfer efficiency of the reaction system, but pore blockage further offsets the potential catalytic advantages of its acid sites [49]. Combined with the weak acid intensity peak of STH observed in NH3-TPD, it can be inferred that this high proportion of Brønsted acid sites not only readily induces undesired side reactions (reducing reaction selectivity) but also exhibits low effective utilization [50]. In contrast, for STH-RF, plasma treatment enhances the specific surface area by modulating particle dispersion and optimizes the pore structure while preserving the SO42− active sites. As a homogeneous catalyst, H2SO4 is constrained by insufficient stability in acid–substrate interactions and prone to competitive side reactions, ultimately resulting in significantly lower yields compared to STH-RF [51,52].

Figure 9.

Catalytic Performance Comparison: Yield of PheOMe over Different Catalysts. Reaction Conditions: 170 °C, 1 MPa N2, 4 h, 2000 rpm.

2.2.2. Effect of Process Parameters on Catalytic Performance

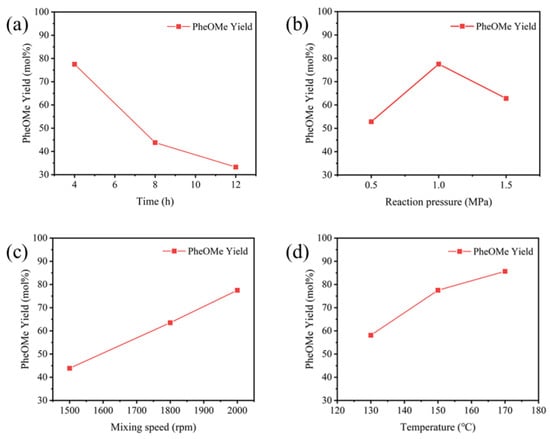

Figure 10a–d systematically investigates the influence of reaction time, pressure, stirring rate, and temperature on the yield of PheOMe. The results indicate that within 4–12 h, the yield decreased significantly from about 78% to 35%, suggesting that prolonged reaction time promotes side reactions or product decomposition [49]. Within the pressure range of 0.5 to 1.5 MPa, the yield first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum of about 78% at 1.0 MPa. Therefore, 1.0 MPa was identified as the optimal pressure. At low pressure, the poor dispersion in the liquid phase leads to the aggregation of phenylalanine, limiting the contact efficiency between the substrate and the catalyst’s active sites and restricting the esterification rate. At the moderate pressure of 1.0 MPa, the appropriate swelling effect of N2 can disrupt the aggregated state of phenylalanine, improve substrate dispersion, and facilitate the removal of the by-product H2O, thereby shifting the equilibrium of the reversible esterification reaction toward PheOMe formation. Conversely, excessively high pressure dilutes the substrate concentration, induces competitive adsorption of N2 on the active sites, promotes side reactions, and inhibits product desorption, ultimately driving the reaction equilibrium backward and resulting in a decreased PheOMe yield. As the stirring speed increased from 1500 rpm to 2000 rpm, the yield continuously rose from 45% to 78%, primarily attributed to enhanced mass transfer driving the reaction toward product formation. Within the temperature range of 120 to 180 °C, increasing the temperature raised the yield from 58% to 88%, indicating that reaction kinetics dominate in this range and higher temperatures significantly enhance reaction efficiency [52].

Figure 10.

Influence of different reaction conditions on PheOMe yield catalyzed by STH-RF. (a) Time: 150 °C, 1 MPa N2, 2000 rpm; (b) Pressure: 150 °C, 4 h, 2000 rpm; (c) Stirring speed: 150 °C, 1 MPa N2, 4 h; (d) Temperature: 1 MPa N2, 2000 rpm, 4 h.

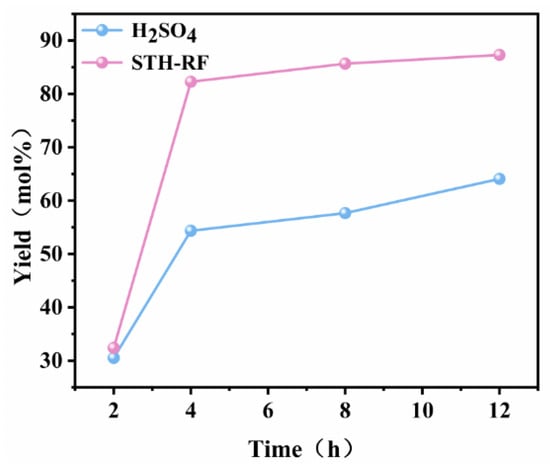

2.3. Catalytic Kinetic Characteristics

Figure 11 investigates the influence of reaction time (2–12 h) on the yield of PheOMe catalyzed by H2SO4 and STH-RF. During the initial 2 h, both catalysts exhibited comparable yields (~30%). With prolonged reaction time, the yield in the STH-RF system increased rapidly, reaching approximately 82% at 4 h, followed by a gradual increase until it stabilized. In contrast, the H2SO4 system showed a more gradual increase in yield, attaining only about 64% after 12 h-significantly lower than the final yield achieved with STH-RF (~87%). These results demonstrate the superior catalytic efficiency of STH-RF, which not only drives the reaction to a high yield within a shorter period but also maintains a consistently higher performance throughout the entire reaction duration compared to H2SO4.

Figure 11.

PheOMe yield versus reaction time over H2SO4 and STH-RF catalyst. Reaction conditions:170 °C, 1 Mpa, 2000 rpm.

2.3.1. Computational Methods and Analysis of Thermodynamic and Kinetic Characteristics of the Catalytic Reaction

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 software package [53]. Geometries were optimized using the B3LYP functional [54] and Grimme’s D3(BJ) dispersion correction [55] and a mixed basis set of LANL2DZ for Ti atom and the 6-31G(d) basis set for all other atoms. Vibrational frequencies were calculated for all the stationary points to confirm if each optimized structure is a local minimum on the respective potential energy surface or a transition state structure with only one imaginary frequency. The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations were carried out to confirm the located transition states connect the correct intermediates. All relative energies and Gibbs free energies (at 298.15 K and 1 atm) are reported in Kcal·mol−1. The optimized 3D structures are illustrated using CYLView 1.0 software [56,57].

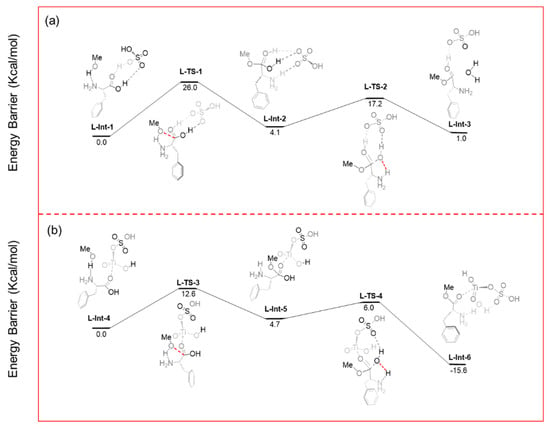

Based on the above computational approach, Figure 12 presents the free-energy profiles for the esterification of phenylalanine catalyzed by concentrated H2SO4 and by the solid superacid STH-RF. The results show that the nucleophilic attack step (transition state L-TS-3) in the STH-RF catalytic system has an energy barrier of 12.6 Kcal·mol−1 (Figure 12b), which is significantly lower than that of the corresponding step in the concentrated H2SO4 system (transition state L-TS-1, energy barrier 26 Kcal·mol−1, Figure 12a). Meanwhile, the final state (L-Int-6) in the STH-RF catalyzed pathway exhibits a negative energy barrier (−15.6 Kcal·mol−1), indicating an irreversible reaction, whereas the final state (L-Int-3) in the concentrated H2SO4 pathway shows a positive barrier (1.0 Kcal·mol−1), corresponding to a reversible process [58].

Figure 12.

Energy barrier variation diagram for the methyl esterification of phenylalanine catalyzed by (a) H2SO4 and (b) STH-RF.

2.3.2. Kinetic Advantage: Mechanism of Rate-Determining Step Barrier Reduction

Concentrated H2SO4 protonates the carboxyl group of phenylalanine via free H+ to form an R-COOH2+ intermediate [59]. This intermediate has a highly localized positive charge, which activates the carbonyl group but also leads to excessive positive charge on the carbonyl carbon [60]. As a result, methanol must overcome considerable electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance to accomplish nucleophilic attack.

In contrast, the Lewis acid site (Ti4+) of STH-RF can directly coordinate with the carbonyl oxygen, while the Brønsted acid site (surface H+) participates in protonation. This Lewis acid–Brønsted acid cooperation effectively polarizes the C=O bond and disperses the charge, avoiding excessive charge localization [61,62,63]. Moreover, as a heterogeneous catalyst, STH-RF possesses a rigid surface structure that can orient methanol molecules. Combined with the reactant adsorption and ordered arrangement effects at the solid–liquid interface (approximation and orientation effects), this further reduces steric hindrance and the effective collision barrier, ultimately leading to a significant decrease in the rate-determining step barrier [61,64].

2.3.3. Thermodynamic Advantage: Driving Mechanism of the Irreversible Reaction

H2SO4 acts as a homogeneous catalyst that only accelerates the reaction by lowering the activation energy; it cannot alter the weakly exothermic and reversible nature of the esterification itself (ΔG close to zero) [65,66]. Therefore, the final-state barrier remains positive, and removal of the by-product water is required to shift the equilibrium and improve conversion [67].

In contrast, within the STH-RF system, the produced ester can strongly adsorb on the catalyst surface (exothermic adsorption lowers the final-state energy), while the hydrophilic surface or pore structure of STH-RF efficiently removes the by-product water in situ [33,68]. This process changes the thermodynamic state of the system, turning the final-state barrier negative and making the reaction irreversible [69,70]. This feature enables the STH-RF-catalyzed esterification to proceed spontaneously to completion without external intervention, thereby achieving nearly quantitative yield [34].

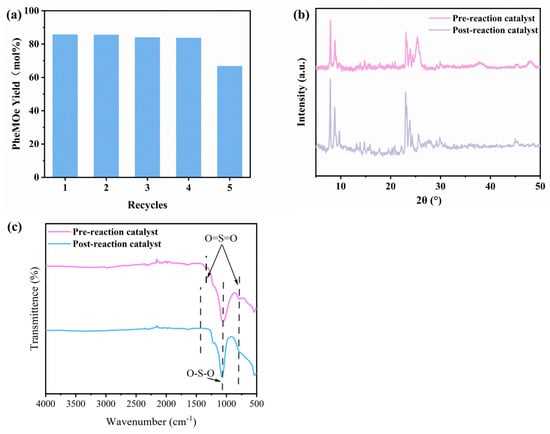

Figure 13 summarizes the cyclic stability of the STH-RF catalyst and its structural evolution before and after the reaction. As shown in Figure 13a, the catalyst maintained a stable PheOMe yield of approximately 85% over four consecutive reaction cycles, with only a slight decrease to about 65% in the fifth cycle, demonstrating good reusability. The XRD patterns in Figure 13b show sharp and high-intensity diffraction peaks for the fresh catalyst, corresponding to high crystallinity and ordered crystalline phases. In contrast, the spent catalyst exhibited significantly weakened and broadened diffraction peaks. This change indicates a reduction in crystallinity and damage to the long-range ordering of the crystal structure after reaction, although no peak shift was observed, confirming that the core phase composition was retained. The FT-IR spectra in Figure 13c further support this: distinct characteristic peaks in the 1500–1000 cm−1 region, attributable to O=S=O/O–S–O vibrations, were observed for the fresh catalyst. These peaks showed attenuation and broadening after reaction, suggesting structural distortion or loss of surface sulfur-containing functional groups. In summary, the STH-RF catalyst exhibits excellent cyclic stability [68,69,70]. However, the decrease in crystallographic ordering and the changes in surface sulfur-containing groups after reaction are the primary reasons for the slight decline in activity observed in the fifth cycle.

Figure 13.

(a) Recyclability of the STH-RF Catalyst in Phe Esterification; (b) XRD Comparison of STH-RF Catalyst Before and After Reaction; (c) FT-IR Comparison of STH-RF Catalyst Before and After Reaction. Reaction conditions: 170 °C, 4 h, 1 Mpa, 2000 rpm.

3. Experiments

3.1. Materials

Phenylalanine (Phe, purity 99%) was purchased from J&K Scientific Ltd. (Beijing, China). Methanol (MeOH, purity 99.5%), ethanol (EtOH, purity 99.8%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, purity 98%), ammonia water (NH3·H2O, 25–28 wt%) and HZSM-5 (SiO2/Al2O3 = 25) were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Titanium oxysulfate-sulfuric acid hydrate (TiSO4·xH2SO4·xH2O, purity ≥ 93%) was supplied by damas-beta (Shanghai, Beijing). L-phenylalanine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-PheOMe, purity 98%) was purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

3.2. Preparation of Catalysts

TiO2 was loaded by referring to the previously reported low-temperature aging method. Firstly, 2 g of HZSM-5 molecular sieve was placed in a 250 mL beaker, and 21.8 mL of deionized water was measured using a 100 mL beaker. 5.26 g of titanium oxysulfate-sulfuric acid hydrate was weighed with filter paper. The deionized water was added to the beaker containing the molecular sieve, and magnetic stirring was conducted at room temperature. Titanium oxysulfate was added to the beaker with a spoon until a thick paste was formed. An appropriate amount of NH3·H2O was added dropwise to liquefy the paste, then the pH value was measured, and titanium oxysulfate was added again. This process was repeated until all titanium oxysulfate was added and the pH was adjusted to 8–9 with NH3·H2O.

The treated solution was aged at room temperature for 15 h, then filtered with water-based filter paper. The solid was taken out and placed in a 50 mL beaker, followed by vacuum drying at 100 °C for 3 h to obtain the dried TiO2/HZSM-5 (TH) precursor. Subsequently, 4 mol/L H2SO4 solution was added dropwise to the precursor and stirred uniformly with a glass rod. Then, it was dried in a vacuum drying oven (DZF-6050AB, Shanghai Lichen Bangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 110 °C for 4 h, and the treated sample was calcined in a muffle furnace (DZF-6050AB, Shanghai Lichen Bangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 450 °C for 4 h to obtain the SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 (STH) catalyst.

The TH precursor was modified by radio frequency plasma treatment (TFE-1200-50-200, Anhui Kemi Instrument Co., Ltd., Hefei, China) under the conditions of 100 W, 600 °C, and 30 min. Then, 4 mol/L H2SO4 was added dropwise, followed by treatment at 110 °C for 4 h, and finally calcination at 450 °C for 4 h to obtain the plasma-modified SO42−/TiO2/HZSM-5 (STH-RF) catalyst.

3.3. Characterization of Catalysts

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using an X-ray diffractometer (ARLEQUINOX Pro, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) to evaluate the crystallinity of the solid superacids. The test conditions were as follows: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm), operating voltage of 40 kV, operating current of 40 mA, scanning range of 5–80° (2θ), and test temperature at room temperature (RT).

The microstructure of the catalysts was observed by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100, Japan Electron Optics Laboratory Co., Ltd., Akishima, Japan). The particle size and lattice spacing of the samples were calculated using ImageJ 1.54f software.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption experiments were conducted on a nitrogen physisorption analyzer (Tristar II 3020, Micromeritics Instrument Co., Ltd., Norcross, GA, USA) to characterize and analyze the pore volume, pore size, and specific surface area of the catalyst samples. The specific surface area was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, while the pore size distribution was described by the Barrett-Joiner-Halenda (BJH) model based on the adsorption branch of the isotherm data.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements of all samples were carried out using an XPS spectrometer (ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) with Al Kα radiation as the excitation source. All tests were performed in a vacuum chamber, and the obtained data were analyzed and processed using XPSPEAK 4.1 software.

The catalysts were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, INVENIO S, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). The number of acid sites (μmol/g) of the samples was determined by infrared spectroscopy of pyridine adsorbed (Py-IR). Each sample was vacuum-activated at 200 °C for 0.5 h, and then the background spectrum of the sample was recorded at 150 °C.

The acid amount of the catalysts was measured by temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia (NH3-TPD) using an automatic adsorption instrument (TP-5080, Tianjin Xianquan Industry and Trade Development Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). First, the sample was pretreated in helium (30 mL/min) by heating to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min for 1 h, then cooled to the adsorption temperature of 120 °C. After the temperature stabilized, the carrier gas/reference gas was switched to the adsorption gas, and adsorption was performed at a flow rate of 30 mL/min for 1 h. Subsequently, the carrier gas was switched back to helium (30 mL/min) and purged for 1 h. After the baseline stabilized, the temperature was raised to 850 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and the signal was recorded ten times per second.

3.4. Catalytic Esterification

0.1 g of catalyst, 0.001 mol of substrate Phe, and 0.5 mol of methanol were added into an autoclave (n(MeOH):n(Phe) = 500:1, 50 mL, SJ50Y4W6-C276-GY, Hefei Safety Instrument Co., Ltd., Hefei, China), where methanol serves as both a reactant and a solvent in the entire system. Before the experiment, the autoclave was purged with nitrogen (purity ≥ 99.9%) three times to remove residual air, and then pressurized with N2 to an absolute pressure of 1.0–1.5 MPa. The reaction was carried out under the set conditions of temperature (130–170 °C), stirring speed (1500–2000 rpm), and time (4–12 h); after the reaction, the system was placed in an ice-water bath to quench the reaction. The separation of the reaction mixture and the catalyst was completed using a 0.22 μm nylon microporous filter (Tianjin Jinteng Instrument Factory, Tianjin, China).

Qualitative analysis of the filtrate was performed by Infinity II high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) equipped with a G7115 ultraviolet-diode array detector (UV-DAD, Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The chromatographic conditions were set as follows: column temperature of 50 °C, mobile phase composed of acetonitrile and water with isocratic elution mode, and detection wavelength of 254 nm. Quantitative analysis of the target product was conducted by the external standard method, with the correlation coefficient R2 of the standard curve > 0.999, and the product concentration unit was mg·mL−1. The product yield was calculated by the following formula:

where Cₚ is the product concentration (g/mL); V is the volume of the mixture after the reaction (mL); Mₚ is the molar mass of the product (g/mol); n is the theoretical moles of the product (mol, 0.001 mol).

3.5. Recycling Performance Test

Referring to the previous regeneration test [6], the solid catalyst after the reaction was filtered, washed with ethanol, and then placed in a vacuum oven for drying at 60 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, it was calcined at 500 °C for 4 h to complete the recovery and regeneration. The recovered catalyst was subjected to the catalytic esterification experiment described in Section 3.4 to test its recycling performance.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the key challenges in the esterification of highly hindered α-aromatic amino acids. Solid superacid catalysts STH and STH-RF were developed using an aging-impregnation method coupled with plasma modification. Systematic characterization revealed that plasma treatment synergistically optimizes the catalyst’s crystal structure, pore architecture, and acidic properties, notably enhancing the density of strong acid sites and Lewis acid sites. Catalytic performance tests demonstrated that STH-RF achieves a yield exceeding 80% in the synthesis of L-phenylalanine methyl ester, which is superior to that of STH (19%) and H2SO4 (63%). Furthermore, STH-RF exhibits a lower energy barrier for the rate-determining step, thermodynamic favorability toward an irreversible reaction pathway, and excellent cycling stability, maintaining a yield ≥ 80% over four consecutive runs. This work provides a novel and efficient catalytic strategy for the green synthesis of highly hindered α-amino acid derivatives, offering both significant theoretical insight and practical potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z., B.T. and W.Z.; methodology, C.Z. and M.Y.; validation, C.Z., L.S. and M.Y.; formal analysis, C.Z. and L.S.; investigation, C.Z. and B.T.; resources, C.Z. and M.Y.; data curation, L.S. and M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S., M.Y. and W.X.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and C.Z.; visualization, L.S. and M.Y.; supervision, C.Z., X.L. and W.Z.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, C.Z., B.T. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 2254098) and Scientific Research Fund Projects of State Key Laboratory of Chemistry for NBC Hazards Protection (No. SKLNBC2023-06).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Suzhou Deyo Bot Advanced Materials Co., Ltd. (www.dy-test.com) for providing support on material characterization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Myers, A.G.; Gleason, J.L.; Yoon, T.; Kung, D.W. Highly Practical Methodology for the Synthesis of d- and l-α-Amino Acids, N-Protected α-Amino Acids, and N-Methyl-α-amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittard, J.; Yang, J. Biosynthesis of the aromatic amino acids. EcoSal Plus 2008, 3, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krecmerova, M. Amino acid ester prodrugs of nucleoside and nucleotide antivirals. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou, I.J.; Kapnissi-Christodoulou, C.P. Use of chiral amino acid ester-based ionic liquids as chiral selectors in CE. Electrophoresis 2013, 34, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.V.S.; Reddy, L.R.; Corey, E.J. Novel acetoxylation and c−c coupling reactions at unactivated positions in α-amino acid derivatives. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3391–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, K.; Luo, J.; Tian, B.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Zhu, W.; Zou, Z. Solid superacid SO42−-S2O82−/SnO2-Nd2O3-catalyzed esterification of α-aromatic amino acids. Mol. Catal. 2023, 535, 112833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.C.; Vimal. A mild and convenient procedure for the esterification of amino acids. Synth. Commun. 1998, 28, 1963–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejidov, F.T.; Mansoori, Y.; Goodarzi, N. Esterification reaction using solid heterogeneous acid catalysts under solvent-less condition. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2005, 240, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.E.; Goodwin, J.G.; Bruce, D.A.; Lotero, E. Transesterification of triacetin with methanol on solid acid and base catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2005, 295, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lotero, E.; Goodwin, J.G. A comparison of the esterification of acetic acid with methanol using heterogeneous versus homogeneous acid catalysis. J. Catal. 2006, 242, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilja, J.; Murzin, D.Y.; Salmi, T.; Aumo, J.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Sundell, M. Esterification of different acids over heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysts and correlation with the Taft equation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2002, 182–183, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Viswanathan, B.; Varadarajan, T.K. Esterification by solid acid catalysts—A comparison. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2004, 223, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yue, H.; Ji, T.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; She, J.; Gu, X.; Li, X. Novel mesoporous TiO2(B) whisker-supported sulfated solid superacid with unique acid characteristics and catalytic performances. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 574, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón, G.; Hidalgo, M.C.; Munuera, G.; Ferino, I.; Cutrufello, M.; Navío, J. Structural and surface approach to the enhanced photocatalytic activity of sulfated TiO2 photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2006, 63, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghili, N.; Halladj, R.; Askari, S. Advancements in synthesis methods and their effects on the physico-chemical properties and yield efficiency of ZSM-5/SAPO-34 composites: A comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2025, 41, 775–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, S.; Yu, J. Metal Sites in Zeolites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6039–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.V.; Miranda, L.S.M.; Nele, M.; Louis, B.; Pereira, M.M. Insights to achieve a better control of Silicon-Aluminum ratio and ZSM-5 zeolite crystal morphology through the assistance of biomass. Catalysts 2016, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatrin, I.; McCue, A.J.; Abdullah, I.; Krisnandi, Y.K. Structural and surface modifications of zeolite to tailor its catalytic properties. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e04324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.A.; Gandhi, D.R.; Chopda, L.V.; Rana, P.H. Esterification of bioplatform molecule succinic acid using ZSM-5 and HZSM-5 catalysts. Indian Chem. Eng. 2021, 63, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M. Plasma Technology for Deposition and Surface Modification; Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.M.; Zhang, D.; Liang, F. Progress in preparation and modification of nano-catalytic materials by low-temperature plasma. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2019, 36, 882–891. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.K.; Bae, I.S.; Song, Y.H.; Kim, T.K.; Vlcek, J.; Musil, J.; Boo, J.H. Synthesis of TiO2 photocatalyst and study on their improvement technology of photocatalytic activity. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 200, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janizadeh, R.; Kavanin, A.; Hosseini, M.S.; Yahyaei, E.; Nejad, A.M.; Mahabadi, H.A. Toluene vapors removal using cold plasma and HZSM-5/TiO2 photo catalyst. J. Health Saf. Work 2021, 11, 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Yan, D.; Li, H.; Du, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, S. Defect chemistry in heterogeneous catalysis: Recognition, understanding, and utilization. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11082–11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Bu, D. Cold plasma treatment of catalytic materials: A review. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 333001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.L.; Du, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W.J. Photocatalytic degradation of reactive brilliant red X-3B on SrTiO3 supported on HZSM-5 molecular sieve. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2016, 33, 2682–2687. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, C.; Cao, G.-P.; Li, X.-K.; Yan, Y.-Z.; Zhao, E.-Y.; Hou, L.-Y.; Shi, H.-Y. Structure of the SO42−/TiO2 solid acid catalyst and its catalytic activity in cellulose acetylation. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2017, 121, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Geiger, J.; Berdunov, N.; Luna, M.L.; Chee, S.W.; Daelman, N.; López, N.; Shaikhutdinov, S.; Cuenya, B.R. Highly stable and reactive platinum single atoms on oxygen plasma-functionalized CeO2 surfaces: Nanostructuring and peroxo effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Sun, Y.; Li, X. Plasma-assisted surface modification of heterogeneous catalysts: Principles, characterization, and applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 5635–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qi, F.; Gomez, M.A.; Su, R.; Yan, Z.; Yao, S.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y. Spectroscopic study on the local structure of sulfate (SO42−) incorporated in scorodite (FeAsO4·2H2O) lattice: Implications for understanding the Fe (III)-As(V)- SO42−-bearing minerals formation. Am. Mineral. 2022, 107, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Z.; He, Y. Ultrafine Nd2O3 nanoparticles doped carbon aerogel to immobilize sulfur for high performance lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 799, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, P.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, M.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, H. Facile Fabrication of Anatase TiO2 Microspheres on Solid Substrates and Surface Crystal Facet Transformation from {001} to {101}. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5949–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.R.; Karkamkar, A.J. Temperature-programmed desorption of water and ammonia on sulphated zirconia catalysts for measuring their strong acidity and acidity distribution. J. Chem. Sci. 2003, 115, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Sastre, G.; Katada, N.; Niwa, M. Quantitative measurements of Brönsted acidity of zeolites by ammonia IRMS–TPD method and density functional calculation. Chem. Lett. 2007, 36, 1034–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropero-Vega, J.L.; Aldana-Pérez, A.; Gómez, R.; Niño-Gómez, M.E. Sulfated titania [TiO2/SO42−]: A very active solid acid catalyst for the esterification of free fatty acids with ethanol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 379, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.W.; Nguyen, P.L.T.; Huynh, L.H.; Liu, Y.-T.; Sutanto, S.; Ju, Y.-H. Catalyst free esterification of fatty acids with methanol under subcritical condition. Energy 2014, 70, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Yu, Y.; He, H. TiO2/HZSM-5 nano-composite photocatalyst: HCl treatment of NaZSM-5 promotes photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 163, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.M.; Dupont, O.; Grange, P. TiO2–SiO2 mixed oxide modified with H2SO4: I. Characterization of the microstructure of metal oxide and sulfate. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 208, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’micheva, G.M.; Domoroshchina, E.N.; Kravchenko, G.V. Design of MFI type Aluminum- and Titanium-containing zeolites. Crystals 2021, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Xia, H.; Dai, Q.; Gu, Y.; Lao, Y.; Wang, X. Chlorinated volatile organic compound oxidation over SO42−/Fe2O3 catalysts. J. Catal. 2018, 360, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plermjai, K.; Boonyarattanakalin, K.; Mekprasart, W.; Phoohinkong, W.; Pavasupree, S.; Pecharapa, W. Optical absorption and FT-IR study of cellulose/TiO2 hybrid composites. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2019, 46, 618–625. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Fan, G.; Yang, L.; Li, F. Surface Lewis acid-promoted copper-based nanocatalysts for highly efficient and chemoselective hydrogenation of citral to unsaturated allylic alcohols. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, G.T.; Pascual, J.J.C.; Delgado, M.R.; Parra, J.B.; Areán, C.O. FT-IR studies on the acidity of gallium-substituted mesoporous MCM-41 silica. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2004, 85, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouilleau, J.; Devilliers, D.; Groult, H.; Marcus, P. Surface study of a titanium-based ceramic electrode material by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. 1997, 32, 5645–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.H.; Nam, K.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, Y.-I.; Cho, D.W.; Sohn, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis of Nd2O3 nanorods. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J. Synergistic effect of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites for the synthesis of polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers over highly efficient SO42−/TiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2017, 355, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, R.; Krishnakumar, B.; Swaminathan, M. Synthesis of Pd co-doped nano-TiO2–SO42– and its synergetic effect on the solar photodegradation of Reactive Red 120 dye. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 25, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Diao, Y.; Han, J.; Yi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hou, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, M.; Ma, D.; Shi, C. Cold plasma-assisted co-conversion of polyolefin wastes and CO2 into aromatics over hierarchical Ga/ZSM-5 catalyst. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 106, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babou, F.; Coudurier, G.; Vedrine, J.C. Acidic Properties of Sulfated Zirconia: An Infrared Spectroscopic Study. J. Catal. 1995, 152, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.D.; Nair, J.J. Sulfated zirconia and its modified versions as promising catalysts for industrial processes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 1999, 33, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, Y.; Fujitani, T.; Yamashita, H. Esterification of levulinic acid with ethanol over sulfated mesoporous zircon silicates: Influences of the preparation conditions on the structural properties and catalytic performances. Catal. Today 2014, 237, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Neuman, T.; Boeglin, A.; Scheurer, F.; Schull, G. Topologically localized excitons in single graphene nanoribbons. Science 2023, 379, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Yan, H.; Zhou, X.; Yao, S.; Wang, Y.; Liang, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Feng, X.; et al. Insight into the effect of lewis acid of W/Al-MCM-41 catalyst on metathesis of 1-butene and ethylene. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 604, 117772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, C. CYLview20–Quick Guide. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345083814_CYLview20_-_Quick_Guide (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Hu, S.; Ye, G.; Zhou, X.; Coppens, M.-O. Understanding the role of internal diffusion barriers in Pt/Beta zeolite catalyzed isomerization of n-Heptane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 132, 1564–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuzem, D.; Pilepić, V. Computational study of hydrogen atom transfer in the reaction of quercetin with hydroxyl radical. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Yates, K. The position of protonation of the carboxyl group1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 4059–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Hua, R. Acid-catalyzed carboxylic acid esterification and ester hydrolysis mechanism: Acylium ion as a sharing active intermediate via a spontaneous trimolecular reaction based on density functional theory calculation and supported by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 30279–30291. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Song, J.; Tang, Y.; Sun, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Synergistic Lewis and Brønsted acid sites promote OH* formation and enhance formate selectivity: Towards high-efficiency glycerol valorization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, T.; Chen, J.; Xu, F. Synergy of Lewis and Brønsted acids on catalytic hydrothermal decomposition of carbohydrates and corncob acid hydrolysis residues to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ma, L.; Lo, P.-K.; Mak, C.-K.; Lau, K.-C.; Lau, T.-C. Cooperative activating effects of metal ion and Brønsted acid on a metal oxo species. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, P.; van de Weghe, P.; Reddy, B.V.; Yadav, J.S.; Grée, R. Unprecedented synergistic effects between weak Lewis and Brønsted acids in Prins cyclization. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9316–9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almstead, N.; Christ, W.; Miller, G.; Reilly-Packard, S.; Vargas, K.; Zuman, P. Equilibria in solutions of methanol or ethanol, sulfuric acid, and alkyl sulfates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 1627–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Bermúdez, L.M.; Monroy-Peña, C.A.; Moreno, D.; Abril, A.; Imbachi Niño, A.D.; Martinez Riascos, C.A.; Buitrago Hurtado, G.; Narváez Rincón, P.C. Kinetic model for the esterification of free fatty acids from palm oil with methanol using sulfuric acid as catalyst and sensitivity analysis in tubular reactors. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, P.; Paula, J.D.; Keeler, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, N.; Huo, K.; Jin, Y.; Liu, D.; Lin, H.; Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; He, M. Lewis and Brønsted Acid Synergistic Catalysis for Efficient Synthesis of Hydroxylamine over Heteroatom Zeolites. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 4786–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Gong, H.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Fu, H.; Li, B.; Zhu, B.; Ji, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, N.; Tang, C.; et al. Greener and higher conversion of esterification via interfacial photothermal catalysis. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F. Synergistic catalysis of Brønsted acid and Lewis acid coexisted on ordered mesoporous resin for one-pot conversion of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.