Abstract

Three-dimensional ZnO structures were prepared by both thermal atomic layer deposition (ThALD) and plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition (PEALD) on a sacrificial cellulose template. The synthetic approach consisted of ALD of conformal ZnO nanofilms on the fibrous cellulose template, followed by thermal removal of the polymer. The resulting calcinated samples, consisting of a scaffold of fused polycrystalline ZnO nanoparticles, showed a sevenfold and ninefold increase in photocatalytic activity against methyl orange under ultraviolet-A light, for the ThALD and PEALD samples, respectively, compared to the non-calcined samples prior to cellulose removal. In addition to the improved three-dimensional surface exposure and accessible active sites, it was suggested that the amount of hydroxyl groups on the surface and the density of nanoparticle packing in 3D ZnO structures are critical parameters for improving the photoinduced degradation of the dye.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) nano- and microarchitectures based on metal oxides exhibit unique physicochemical properties that make them suitable for a variety of technological applications. Compared to planar structures, their functional advantages are directly related to their large surface area and tunable porosity, which are particularly beneficial in catalysis, adsorption, drug delivery, separation, and sensing [1,2,3]. Among various fabrication strategies, the use of sacrificial polymers has proven to be a simple and effective bottom-up method for producing 3D nanomaterials [4,5,6]. This approach typically involves the initial deposition of the ceramic material on the polymer substrate, which is subsequently removed either chemically [7,8] or thermally [9,10]. In this way, a variety of complex ceramic materials can be produced, such as nanotubes, nanofibers, nanopillars, and hollow nanostructured materials.

Different synthetic approaches have been used for the initial polymer template coating of oxide-based materials, which can generally be categorized into solution-phase [11,12] and gas-phase methods [13,14]. Although sol–gel synthesis is one of the most versatile methods for modifying polymer surfaces, its drawbacks include limited control over coating conformality and homogeneity, as well as the use of solvents that can contaminate the metal oxide surface and/or cause swelling of the polymer template, altering its conformational and structural stability for subsequent ceramic growth. On the other hand, common high-temperature evaporation processes such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [13] or physical vapor deposition (PVD) [14] can also pose challenges for uniform and conformal deposition of metal oxides on complex substrates, especially on thermally sensitive polymers.

Among vapor phase deposition techniques, atomic layer deposition (ALD) has proven to be the technique of choice for controlled and automated deposition on thermally sensitive substrates [15]. The ALD process is based on the sequential exposure of a substrate to organometallic precursor molecules and then to a counter-precursor (e.g., H2O, O3, or O2 in the case of metal oxides) from the gas phase. Self-limiting surface reactions occur during each ALD cycle, allowing a maximum amount of precursor species to chemisorb onto the surface, so the thickness of the growing layer can be controlled at the angstrom scale. Because of the self-saturating nature of the surface reactions during ALD, homogeneous and conformal film growth can be achieved even on complex 3D structures, including fiber-like interwoven polymer structures [16].

In “classical” thermally driven ALD (ThALD), surface reactions occur between nucleophilic surface-reactive functionalities or counter-precursors and electrophilic organometallic species. In the plasma-enhanced ALD (PEALD) variation, plasma generates reactive species (ions and radicals) that act as counter-precursors, enabling reactions at lower temperatures than in ThALD [17].

Three-dimensional ZnO nanostructures have recently attracted significant attention in photocatalysis, particularly for potential applications in environmental remediation of water [18,19]. ZnO is a wide bandgap (3.37 eV) semiconductor whose photocatalytic effect is based on the light-induced excitation of an electron from the ZnO valence band to the conduction band. The photogenerated electrons and holes reach the surface and react with surrounding H2O and O2, forming reactive oxygen species (ROS) responsible for the rapid and effective oxidation and degradation of most organic and biological pollutants. Compared to the mainly studied low-dimensional ZnO structures, such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, and nanoplates, 3D ZnO offers additional advantages for photocatalytic water treatment, including a porous structure, high surface-to-volume ratio, and large surface area that allows easy access of reactants and light to the photocatalyst surface. Most protocols reported in the literature for the deposition of 3D ZnO structures are based on solution-phase synthesis, usually by hydrothermal processes combined with heat treatment [20,21,22,23].

In this work, we report the preparation of 3D ZnO structures consisting of fused ZnO nanoparticles by both thermal and plasma ALD on a sacrificial cellulose template. Cellulose, the most abundant biopolymer on earth, was chosen as a template due to its cost-effectiveness and lack of toxicity. The abundance of reactive hydroxyl groups on the cellulose surface improves the initiation of ALD chemistry by ensuring strong adhesion to the polymer substrate and the formation of high-quality thin ceramic films.

Our synthetic approach consisted of two steps: (i) ALD of conformal ZnO nanofilms on the cellulose template, and (ii) thermal removal of the sacrificial polymer. After calcination, the resulting 3D ZnO arrays were tested as photocatalysts for the degradation of a model pollutant, methyl orange (MO), under UVA light irradiation. For comparison, cellulose coated with ZnO thin films deposited by ThALD and PEALD in step (i) was used as reference material and subjected to analogous photocatalytic activity measurements.

2. Results and Discussion

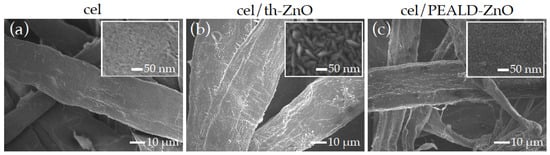

FE-SEM images of the cellulose surface before (cel) and after deposition of ZnO by ThALD (cel/th-ZnO) and PEALD (cel/PEALD-ZnO) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

FE-SEM images of (a) cel, (b) cel/th-ZnO and (c) cel/PEALD-ZnO, taken at 1000× magnification. The insets show microscopic images of the samples at 50,000× magnification.

The low magnification images in Figure 1b,c show that the morphology of pristine cellulose (cel), which consists of dense fibrous structures with heterogeneous thicknesses ranging from 1 μm to several tens of μm (Figure 1a), is preserved after thermal and PEALD of ZnO. A higher magnification SEM image shows increased surface roughness in the form of conformally distributed, rice-like nanograins with an average length of about 70 nm in the case of cel/th-ZnO (inset in Figure 1b) and round nanoparticles about 10 nm in size in the case of cel/PEALD-ZnO (Figure 1c).

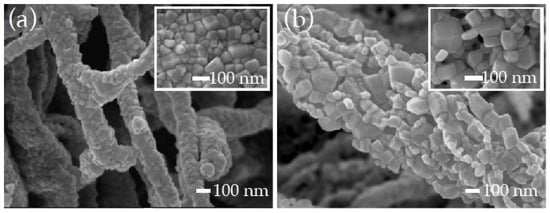

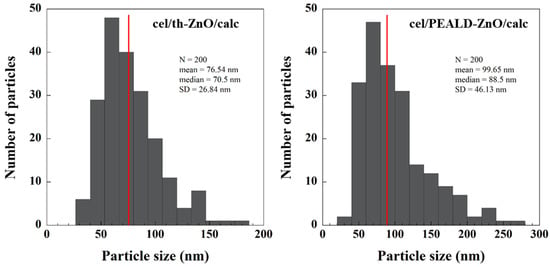

After thermal removal of the sacrificial cellulose in cel/th-ZnO (sample cel/th-ZnO/calc) and cel/PEALD-ZnO (sample cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc) at 700 °C, the ZnO nanoparticles sintered to form interconnected quasi-round ZnO particles (Figure 2a). Particle size histograms derived from FE-SEM images showed a narrower distribution of smaller cel/th-ZnO/calc nanoparticles, with an average size of approximately 77 nm, compared to the larger, more polydisperse nanoparticles of cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, which had an average size of approximately 100 nm (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

FE-SEM images of (a) cel/th-ZnO/calc and (b) cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, taken at 40,000× magnification. The insets show microscopic images of the samples at 50,000× magnification.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution of cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

The overall architecture of the resulting ZnO retained the shape of the sacrificial polymer, and solid agglomerates of tubular ZnO structures were formed. However, while the tubular structure of the calcinated cel/th-ZnO is compact and dense, the particles of the calcinated cel/PEALD-ZnO coalesce into a mesoporous, net-like microstructure (Figure 2b) with the mean pore area of approximately 60 nm2 (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material). From FE-SEM image analysis, the interparticle contact area per unit volume (SV) was determined to be 0.047 ± 0.003 nm−1 for cel/th-ZnO/calc and 0.026 ± 0.003 nm−1 for cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc. This difference reflects the more extensive particle–particle connectivity in cel/th-ZnO/calc.

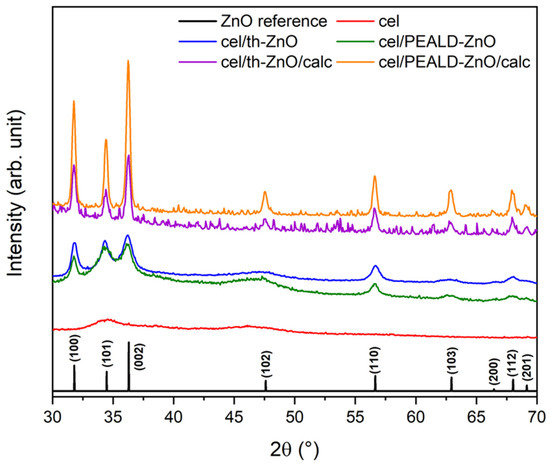

The crystallinity of cel, cel/th-ZnO, cel/PEALD-ZnO, cel/th-ZnO/calc, and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc was determined using the XRD patterns shown in Figure 4. All samples exhibit diffraction peaks at 31.8°, 34.3°, and 36.2°, which correspond to the crystal planes (100), (002), and (101), respectively, and are characteristic of the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO (reference data JCPDS-36-1451). The peak intensities match the powder reference, indicating no preferred orientation of the crystals [24], and the lattice constants agree with literature values [25]. The diffractogram of pristine cellulose (cel) shows an additional crystalline peak at 34.5°, which corresponds to the crystallographic plane (004) of the Iβ structure of natural semi-crystalline cellulose [26].

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of cel, cel/th-ZnO, cel/PEALD-ZnO, cel/th-ZnO/calc, and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

The calculated crystallite sizes (D, Table 1) indicate that the rice-like ZnO grains of cel/th-ZnO observed by FE-SEM (see Figure 1b) are composed of smaller crystallites, while the estimated grain size of cel/PEALD-ZnO from FE-SEM images (see Figure 1c) closely matches the crystallite size in Table 1. After thermal treatment, both cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc show an increase in crystallite size due to thermally induced coalescence of smaller particles into larger ones. As a result, the crystallite sizes increase from 13.4 and 16.6 nm to 25.2 and 24.6 nm after calcination for cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of the calculated crystallite sizes (D) and lattice constants (a, c) with the corresponding c/a ratio.

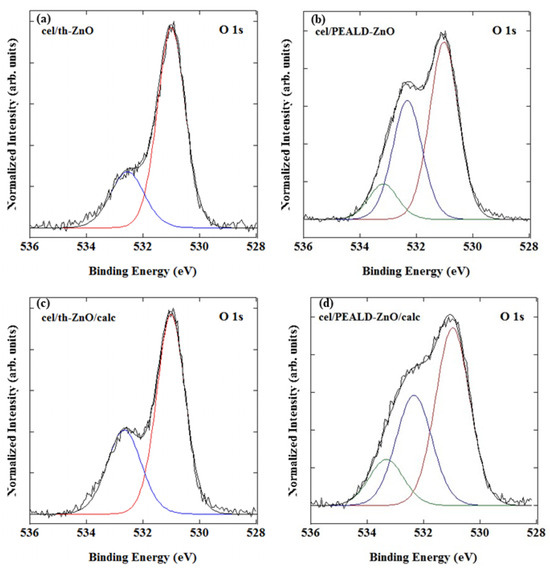

The surface composition of cel/th-ZnO, cel/PEALD-ZnO, cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc was analyzed by XPS.

After calcination of cel/th-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO, all cellulose-derived carbonaceous species are removed, and no corresponding signals are detected in the XPS survey spectra. As shown in the Supplementary Material (Figure S2), both cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc and cel/th-ZnO/calc exhibit only Zn and O photoemission peaks. The very weak C 1s contribution observed is attributed to adventitious carbon, which is commonly present on ceramic oxide surfaces exposed to ambient conditions and does not indicate residual cellulose-derived contamination. This confirms that the calcination process yields chemically clean ZnO surfaces.

The photoemission around the Zn-2p core levels shows no significant changes before and after calcination, with the symmetric Zn-2p3/2 peak centered at 1022.4 eV corresponding to Zn2+ in the ZnO crystal lattice (see Figure S3 in the Supplementary Material).

The O 1s core-level spectra of all samples (Figure 5) can be consistently deconvoluted into components corresponding to distinct oxygen environments. The dominant peak at 531.0 eV is assigned to lattice oxygen (O2−) in the crystalline ZnO structure and appears in all samples, with no significant shift in binding energy after calcination, indicating preservation of the Zn2+–O2− framework.

Figure 5.

O 1s XPS core-level spectra of (a) cel/th-ZnO, (b) cel/PEALD-ZnO, (c) cel/th-ZnO/calc and (d) cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

The higher binding energy component at approximately 532.6 eV is attributed to surface hydroxyl groups and/or chemisorbed water [27,28]. In the cel/th-ZnO samples, synthesized using H2O as the oxygen co-precursor, this contribution is especially pronounced and increases after calcination (cel/th-ZnO/calc), indicating a higher concentration of surface hydroxylated species (Figure 5a,c)

For cel/PEALD-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, an additional intermediate O 1s component at approximately 532.1 eV is observed. This peak is typically associated with non-stoichiometric or chemisorbed oxygen species [28,29] and is attributed here to residual reactive oxygen incorporated during the oxygen plasma step of the PEALD process [30,31,32,33]. The persistence of this feature after calcination, along with its presence in PEALD-ZnO films deposited on silicon reference substrates (Figure S4, Supplementary Material), indicates that these oxygen-related surface states originate from the plasma-assisted growth mechanism.

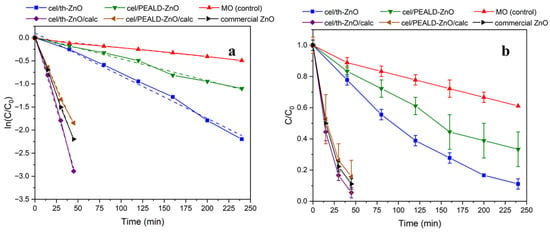

Next, the photocatalytic performances of cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc and cel/th-ZnO/calc samples were measured for the degradation of methyl orange (MO) under UVA light irradiation (Figure 6). The pre-calcination samples cel/th-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO, consisting of thin ZnO films conformally deposited on the fibrous cellulose template, were measured under the same experimental conditions.

Figure 6.

Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange (MO) in the presence of cel/th-ZnO, cel/PEALD-ZnO, cel/th-ZnO/calc, cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, and commercial ZnO. (a) Logarithmic plots of normalized concentration, log(C/C0), versus time. (b) Normalized concentration, C/C0, versus time; data points represent the mean of three parallel experiments, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. A pure MO solution without a catalyst was used as the control.

Because mineralization—i.e., the degradation of organic molecules to harmless inorganic compounds such as water or CO2—is an important goal for the application of photocatalysts in water treatment, the photocatalytic efficiency of the materials was evaluated by observing the decrease in intensity of two peaks in the UV spectrum of MO: the most intense peak at 462 nm, which represents the cleavage of the azo bond in MO, and the peak centered at 270 nm, which reflects both the degradation of organic intermediates and the desired mineralization [34]. The disappearance of the latter is an indicator of the extensive breakdown of the MO dye.

Before irradiation with UVA light, the analyzed mixtures were kept in the dark for 40 min to establish adsorption–desorption equilibrium of the dye on the photocatalyst surface, without measuring significant changes in dye concentration in the solution. The UV-Vis absorption spectra (Figure S5 in Supplementary Material) show that within 240 min of UV light irradiation, approximately 90% and 70% azo cleavage was achieved for cel/th-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO, respectively, while no mineralization occurred. Additionally, the peak at about 462 nm decreases with irradiation time, whereas the peak at about 270 nm increases, which can be attributed to the increased number of oxidized intermediates formed during the degradation process [34]. In contrast, cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc exhibit strong photocatalytic properties, suggesting potentially near-complete mineralization of MO within 60 min.

The photocatalytic efficiency of the samples was evaluated by monitoring the peak at 462 nm. The photocatalytic degradation kinetics (Figure 6a) follows the first order reaction, described by ln(C/C0) = −kt. A summary of the calculated rate constants (k) and degradation half-lives (t1/2) can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the calculated photodegradation rate constants (kDR) and half-life times (t1/2) for different samples.

The rate constants of cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc are seven and nine times higher, respectively, than before calcination, highlighting a key advantage of the 3D materials over thin ZnO films; enhanced three-dimensional surface exposure and an increased number of accessible active sites that promote dye degradation.

To further clarify the impact of particle organization, a direct comparison was made between 3D fused ZnO networks and discrete nanoparticles. Commercial ZnO powder, consisting of discrete, separated particles with an average size of approximately 150 nm, was used as a reference and tested under the same experimental conditions. The photocatalytical degradation curves (Figure 6) show that although commercial ZnO exhibits better photocatalytic activity than cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, the highest performance is observed for cel/th-ZnO/calc, which is approximately 35% higher than cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

These observations are consistent with the structural characteristics of cel/th-ZnO/calc, whose densely packed nanoparticles are interconnected through fused junctions, forming an extensive network of internal interface regions. In contrast, cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc and commercial ZnO consist of more loosely organized or larger, well-separated particles, resulting in fewer internal interfaces and comparatively lower photocatalytic activity.

This comparison highlights that particle connectivity, rather than surface area alone, are some of the key factors in determining photocatalytic efficiency.

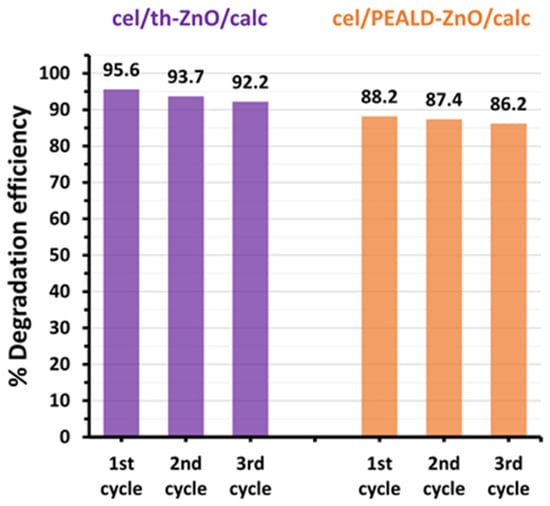

Furthermore, the stability of the photocatalysts cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc was tested by reusing them in three consecutive catalytic cycles under the same conditions described for photocatalysis. Between each cycle, the catalysts were separated by centrifugation, washed with demineralized water and ethanol, and left to dry overnight under ambient conditions. As shown in Figure 7, both photocatalysts are very stable, losing only 2–3% of their degradation efficiency after three recycling cycles.

Figure 7.

Recycling tests of photocatalysts cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc. The percentage degradation efficiency against MO was calculated as (1 − Ct/C0) × 100% after 45 min of UVA irradiation.

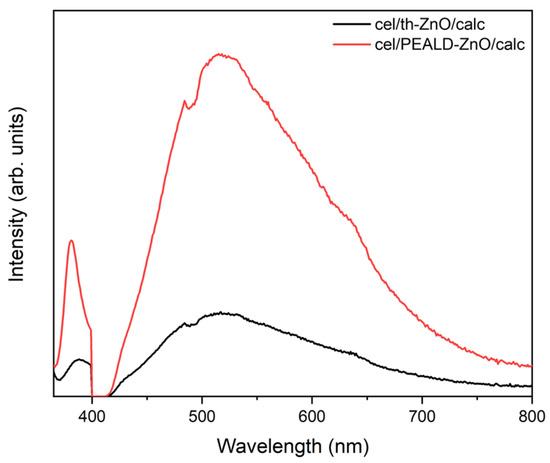

Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy provides complementary insight into the photocatalytic behavior of cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc (Figure 8). Both samples exhibit two main emission features at approximately 391 nm and 508 nm, corresponding to near-band-edge (NBE) recombination and defect-related radiative transitions within the ZnO bandgap, respectively [35,36]. In cel/th-ZnO/calc, the intensity of both PL peaks decreased compared to cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, indicating more efficient charge-carrier separation and suppressed electron–hole recombination. This behavior is consistent with previous reports showing that simultaneous reduction in both UV and visible PL emissions in ZnO-based materials correlates with enhanced photocatalytic activity [35,36,37]. Improved charge separation increases the number of electrons and holes available for surface redox reactions, facilitating the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that drive the degradation of organic compounds [38,39,40,41].

Figure 8.

Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of cel/th-ZnO/calc and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

The improved charge-carrier separation in cel/th-ZnO/calc can be attributed to its surface chemistry and nanoparticle organization. XPS in Figure 5 shows that cel/th-ZnO/calc contains more surface –OH groups than cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc; these hydroxyls can adsorb water and oxygen and act as hole traps, thereby promoting ROS formation and suppressing electron–hole recombination [37,39,41,42,43]. FE-SEM images indicate that cel/th-ZnO/calc consists of densely fused nanoparticles (inset Figure 2a) with interparticle contact area per volume (SV) almost twice as large as that of cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc, which exhibits a looser, net-like mesoporous morphology (inset Figure 2b). The higher area of interparticle junctions in cel/th-ZnO/calc is expected to enhance electronic connectivity and facilitate charge migration, also consistent with reports linking improved grain fusion to higher photocatalytic activity [38,39,40].

The difference in nanoparticle fusion and defect chemistry likely arises from the respective ALD processes. Thermal ALD yields uniform ZnO films that calcine into well-connected nanoparticles, whereas the more reactive PE ALD process can introduce non-stoichiometric oxygen species and less uniform particle fusion [39,40,41]. Such defects may create mid-gap states that act as recombination centers, diminishing the pool of charge carriers available for surface redox reactions [44,45]. Together with broader particle-size distributions and reduced interparticle connectivity, these factors limit charge migration and ROS generation in PE-ALD ZnO. Overall, the dense nanoparticle packing, high interparticle connectivity, and surface –OH coverage of cel/th-ZnO/calc collectively provide efficient charge transport and suppress recombination, explaining its superior photocatalytic performance relative to the mesoporous cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. ALD Processing

Cellulose samples (cel) used as substrates for ALD of ZnO thin films, were prepared by cutting dry cellulose paper (Södra Green T, Södra, Sweden) into small discs with a diameter of 6 mm and thickness of 2 mm.

The ZnO thin films were synthesized using a Beneq TFS 200 ALD instrument (Beneq, Espoo, Finland). The processing parameters for ZnO deposition were adapted from experiments on a silica wafer substrate, where analogous film thicknesses were obtained by thermal and PEALD synthesis.

ThALD deposition of ZnO films on cellulose substrate (cel/th-ZnO) was performed in 250 cycles using diethylzinc (DEZ, <95%, STREM Chemicals, Inc., Bischheim, France) as the precursor and deionized water as the counter-precursor. Nitrogen (purity 6.0) was used as the carrier and purge gas.

Each cycle consisted of 180 ms DEZ pulsing, 1 s N2 purge, 180 ms H2O pulsing and 1 s N2 purge. The processing temperature was maintained at 120 °C.

PEALD of ZnO films on cellulose substrate (cel/PEALD-ZnO) was carried out in 150 cycles using diethylzinc (DEZ, 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and oxygen plasma generated by a capacitively coupled plasma source operated at 13.56 MHz and 150 W and the processing temperature of 120 °C. Each cycle consisted of 250 ms DEZ pulses, 1.25 s N2 purging, 3 s oxygen plasma pulses and 6 s N2 purging.

3.2. Post-Deposition Calcination

Thermal annealing of the cel/th-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO samples was performed in air to prevent carbon contamination from degradation of the sacrificial cellulose template. The samples were placed in a ceramic boat for pyrolysis and heated to 700 °C in a programmable Carbolite Gero tube furnace at a heating rate of 10 °C/min for 1 h. The samples were then cooled slowly to room temperature overnight in the oven and stored in a desiccator.

3.3. Characterization

The chemical composition of the surface was analyzed using a SPECS X-ray photoemission spectrometer (XPS) equipped with a Phoibos MCD 100 electron analyzer (Berlin, Germany) and a monochromated Al Kα X-ray source at 1486.74 eV. The typical pressure in the ultra-high vacuum chamber was in the range of 10−7 Pa, and the pass energy of the spectrometer was set to 10 eV, providing an energy resolution of about 0.8 eV. The experimental photoemission curves were deconvoluted with the mixture of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions, using commercial UNIFIT 2018 software.

Surface morphology was investigated using a Jeol JSM-7800F field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Tokyo, Japan) with an electron beam accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

The particle size distribution was determined using Smile View software (version 2.1), based on measurements of 200 individual particles. The maximum Feret diameter, defined as the longest distance across each particle, was used as the representative particle size in the analysis.

Interparticle contact area per unit volume (SV) was quantified from plan-view SEM micrographs using standard stereological principles. For each sample, four SEM images were analyzed. Interparticle contacts were identified and traced manually in ImageJ (version ImageJ.JS) using the Freehand Line tool. Only true particle–particle interfaces were included in the measurement, while contacts adjacent to pores, voids, or particle-free regions were excluded, as these do not represent actual interparticle contacts. To avoid double counting, each contact segment was traced only once, following a systematic left-to-right and top-to-bottom procedure across the image.

The total interparticle contact length in each image (L, in nm) was obtained using the Measure function after calibration. The analyzed image area (A, in nm2) was identical for all images. The interparticle contact area per unit volume was then calculated using the stereological relation:

which relates the contact length per unit area in 2D to the contact surface area per unit volume in 3D. For each sample, the final SV value is reported as the mean ± standard deviation from the four independent micrographs.

Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were performed at room temperature using a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a Xe lamp at an excitation energy of 3.87 eV (wavelength 320 nm).

Structural analysis was conducted using grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD). Measurements were performed with a diffractometer equipped with a Cu X-ray tube (λ = 1.5406 Å) and a W/C multilayer for monochromatization and beam shaping (D5000, Siemens, Karlsruhe, Germany). A curved position-sensitive detector (RADICON) collected the diffracted spectra in the angular range 2θ = 30–85°. A fixed grazing incidence angle of αi = 1.5° was used for all measurements. The JCPDS 36-1451 card was used for the crystallographic analysis of ZnO. The average crystallite size (D) was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer formula.

3.4. Measurements of the Photocatalytic Activity

An aqueous solution (2.5 mL, 8.0 × 10−6 M) of methyl orange (MO) in deionized water and 2 mg of ZnO photocatalyst were added to a quartz Suprasil cuvette (the same series of cuvettes was used for parallel measurements) sealed with quartz windows. The cuvette was kept in the dark for 40 min to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium and then irradiated with UVA light (glass filter for wavelengths < 315 nm) in a Unitron International Intelli-Ray 600 curing system (light intensity 35%, estimated irradiance ~20 mW/cm2). In parallel, control experiments were carried out using the MO solution in the absence of catalyst, and with 2 mg of commercial ZnO powder (Fluka, average particle size ≈ 150 nm). Additionally, the photocatalytic activity of the ZnO thin films on cellulose was measured using one disk taken from the same ALD batch. The average masses for a set of three disks were 19.7 mg for cel/th-ZnO and 19.9 mg for cel/PEALD-ZnO. The absorption spectra of the upper solution were measured at specific intervals using a Thermo Scientific Evolution 201 UV/Vis spectrophotometer. The peak maximum at about 460 nm was used to monitor the MO concentration. All photocatalytic degradation experiments were performed in three parallels, and the results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we used both thermal ALD (ThALD) and plasma-enhanced ALD (PEALD) to conformally coat bulk cellulose fibers with ZnO thin films. Using different precursor chemistries affected the morphology of the crystal grains, as well as surface composition. Subsequent removal of cellulose by thermal treatment of the hybrid materials at 700 °C produced 3D ZnO structures with high stability and enhanced photocatalytic properties against methyl orange under UVA irradiation. Both structures consist of fused wurtzite nanoparticles; however, differences in morphology, surface composition, and photoluminescence result from differences in the samples before calcination. Accordingly, a noticeable difference in photocatalytic performance between the calcinated samples was observed. Since there are only a limited number of reports directly comparing ThALD and PEALD, careful studies are needed to understand the correlation between processing conditions, the chemical mechanisms of the film growth reactions, and the material properties. Nevertheless, this study highlights the potential of using an inexpensive template such as cellulose in combination with ALD technology to prepare 3D ZnO materials with enhanced photodegradative properties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010017/s1, Figure S1. FE-SEM images of cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc (a) before and (b) after ImageJ-based pore analysis. Image processing included pixel-size calibration, image segmentation, morphological filtering, and visual verification of segmentation accuracy. (c) Corresponding pore-size distribution histogram with the calculated mean pore area and porosity.; Figure S2. XPS survey spectra of cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc and cel/th-ZnO/calc; Figure S3. Photoemission spectra recorded around the Zn 2p3/2 core-level of (a) cel/th-ZnO/calc and (b) cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc Figure S4. XPS spectrum measured around the O 1s core-level of a PEALD-deposited ZnO film on a silicon wafer; Figure S5. Time-dependent UV-Vis absorption spectra of MO upon UV irradiation in the presence of (a) cel/th-ZnO and cel/th-ZnO/calc, and (b) cel/PEALD-ZnO and cel/PEALD-ZnO/calc.

Author Contributions

R.R.: Investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. M.K.M.: Supervision, investigation, data curation, methodology, validation. R.P.: investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, validation. I.K.P.: formal analysis, validation, data curation, methodology. K.S.; formal analysis, validation. G.A.: supervision, conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been mainly supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project IP-2016-06-3568, and by the University of Rijeka under the project numbers uniri-iskusni-prirod-23-22 and uniri-mzi-25-55. The characterization instruments applied in this work were acquired through the European Fund for Regional Development and Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of the Republic of Croatia under the project Research Infrastructure for Campus based Laboratories at the University of Rijeka (grant number RC.2.2.06-0001).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Verma, C.; Berdimurodov, E.; Verma, D.K.; Berdimuradov, K.; Alfantazi, A.C.; Hussain, M. 3D Nanomaterials: The future of industrial, biological, and environmental applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 156, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lei, Y. 3D Nanostructures for the Next Generation of High-Performance Nanodevices for Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M. Hierarchical photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Pan, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, J. Atomic Layer Assembly Based on Sacrificial Templates for 3D Nanofabrication. Micromachines 2022, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Goebl, J.; Yin, Y. Templated synthesis of nanostructured materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Khan, A.M.; Shujait, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Ikram, M.; Imran, M.; Haider, J.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 300, 10259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotosho, K.D.; Gurung, V.; Banerjee, P.; Shevchenko, E.V.; Berman, D. Self-Cleaning Highly Porous TiO2 Coating Designed by Swelling-Assisted Sequential Infiltration Synthesis (SIS) of a Block Copolymer Template. Polymers 2024, 16, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ghazzal, M.N.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Pan, D.; Wu, W. A Facile Strategy for the Preparation of N-Doped TiO2 with Oxygen Vacancy via the Annealing Treatment with Urea. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatidoye, O.; Thomas, D.; Bastakoti, B.P. Facile synthesis of mesoporous TiO2 film templated by block copolymer for photocatalytic applications. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 15761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Polymer Template Synthesis of Soft, Light, and Robust Oxide Ceramic Films. iScience 2019, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borilo, L.; Kozik, V.; Vorozhtsov, A.; Klimenko, V.; Khalipova, O.; Agafonov, A.; Kusova, T.; Kraev, A.; Dubkova, Y. The Low-Temperature Sol-Gel Synthesis of Metal-Oxide Films on Polymer Substrates and the Determination of Their Optical and Dielectric Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Illia, G.J.A.A.; Crepaldi, E.L.; Grosso, D.; Sanchez, C. Mesoporous hybrid and nanocomposite thin films. A sol–gel toolbox to create nanoconfined systems with localized chemical properties. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, S.; Di Maggio, F.; Shujah, T.; Blackman, C. Chemical Vapour Deposition of Gas Sensitive Metal Oxides. Chemosensors 2016, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.; Silva, F.; Porteiro, J.; Míguez, J.; Pinto, G. Sputtering Physical Vapour Deposition (PVD) Coatings: A Critical Review on Process Improvement and Market Trend Demands. Coatings 2018, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Ahn, C.; Jeon, S.; Park, J. Atomic Layer Deposition of Inorganic Thin Films on 3D Polymer Nanonetworks. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mežnarić, S.; Jelovica Badovinac, I.; Šarić, I.; Peter, R.; Kolympadi Marković, M.; Ambrožić, G.; Gobin, I. Superior UVA-photocatalytic antibacterial activity of a double-layer ZnO/Al2O3 thin film grown on cellulose by atomic layer deposition (ALD). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääriäinen, T.O.; Lehti, S.; Kääriäinen, M.-L.; Cameron, D.C. Surface modification of polymers by plasma-assisted atomic layer deposition. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2011, 205, S475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Zhou, D.; Xiang, L. A Review on the Fabrication of Hierarchical ZnO Nanostructures for Photocatalysis Application. Crystals 2016, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.E.; Agarwal, S.P.; An, S.; Kazyak, E.; Das, D.; Shang, W.; Skye, R.; Deng, T.; Dasgupta, N.P. Biotemplated Morpho Butterfly Wings for Tunable Structurally Colored Photocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Jung, P.-H.; Park, J.; Chae, D.; Huh, D.; Byun, M.; Ju, S.; Lee, H. Customizable 3D-printed architecture with ZnO-based hierarchical structures for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 21696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlazan, P.; Ursu, D.H.; Irina-Moisescu, C.; Miron, I.; Sfirloaga, P.; Rusu, E. Structural and Electrical Properties of TiO2/ZnO Core-Shell Nanoparticles Synthesized by Hydrothermal Method. Mater. Charact. 2015, 101, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Khanian, N.; Rashid, U.; Choong, T.S.Y. Core-Shell ZnO-TiO2 Hollow Spheres Synthesized by in-Situ Hydrothermal Method for Ester Production Application. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Nayem, S.M.A.; Alam, M.S.; Islam, M.I.; Seong, G.; Chowdhury, A.-N. Hydrothermal ZnO Nanomaterials: Tailored Properties and Infinite Possibilities. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti, B.; Zhafirah, A.; Carieta, V.A.; Hamid, N.; Marwoto, P.; Sugianto; Nurbaiti, U.; Ratnasari, F.D.; Putra, N.M.D.; Aryanto, D. X-Ray Diffraction Studies of ZnO:Cu Thin Films Prepared Using Sol-Gel Method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1567, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, Ü.; Alivov, Y.I.; Liu, C.; Teke, A.; Reshchikov, M.A.; Doğan, S.; Avrutin, V.; Cho, S.-J.; Morkoç, H. A Comprehensive Review of ZnO Materials and Devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, L.; Milotskyi, R.; Sharma, G.; Takahashi, K. Cellulose Processing in Ionic Liquids from a Materials Science Perspective: Turning a Versatile Biopolymer into the Cornerstone of Our Sustainable Future. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, H. On the wrong assignment of the XPS O1s signal at 531–532 eV attributed to oxygen vacancies in photo- and electro-catalysts for water splitting and other materials applications. Surf. Sci. 2021, 712, 121894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankcombe, T.J.; Liu, Y. Interpretation of Oxygen 1s X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy of ZnO. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintcheva, N.; Aljulaih, A.A.; Wunderlich, W.; Kulinich, S.A.; Iwamori, S. Laser-Ablated ZnO Nanoparticles and Their Photocatalytic Activity toward Organic Pollutants. Materials 2018, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Valle, N.; Guillot, J.; Bour, J.; Adjeroud, N.; Fleming, Y.; Guennou, M.; Audinot, J.-N.; El Adib, B.; Joly, R.; et al. Elucidating the growth mechanism of ZnO films by atomic layer deposition with oxygen gas via isotopic tracking. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, H.; Mohandoss, S.; Balasubramaniyan, N.; Loganathan, S. Non-Thermal Plasma-Assisted Synthesis of ZnO for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Plasma 2025, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappim, W.; Testoni, G.; Miranda, F.; Fraga, M.; Furlan, H.; Saravia, D.A.; Sobrinho, A.d.S.; Petraconi, G.; Maciel, H.; Pessoa, R. Effect of Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition on Oxygen Overabundance and Its Influence on the Morphological, Optical, Structural, and Mechanical Properties of Al-Doped TiO2 Coating. Micromachines 2021, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardas Babić, D.; Peter, R.; Perčić, M.; Salamon, K.; Vengust, D.; Radošević, T.; Podlogar, M.; Omerzu, A. Photocatalytic properties of thin ZnO films synthesised with plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition at room temperature. Vacuum 2025, 240, 114504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Dong, J.; Sun, P.; Yan, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, B. An Efficient Strategy for Full Mineralization of an Azo Dye in Wastewater: A Synergistic Combination of Solar Thermo- and Electrochemistry plus Photocatalysis. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 36246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. Photoluminescence and photocatalytic properties of ZnO nanostructures: Correlation of NBE and defect emission with charge-carrier dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 11673. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, C. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanostructures: Insights from PL spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 359, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Yu, H.; Ho, W.; Jiang, Z. Defect and band-edge emission in ZnO: Relation to photocatalytic efficiency. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 408, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Senthamizhan, A.; Prabukumar, S.; Valarmathi, S.; Ramasamy, P.; Chinnusamy, C. Highly Stacked ZnO Nanograins with Superior Photocatalytic Activity. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 11575. [Google Scholar]

- Kedruk, Y.Y.; Baigarinova, G.A.; Gritsenko, L.V.; Cicero, G.; Abdullin, K.A. Facile Low Cost Synthesis of Highly Photocatalytically Active Zinc Oxide Powders. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 869493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthamizhan, A.; Balusamy, B.; Aytac, Z.; Uyar, T. Grain Boundary Engineering in Electrospun ZnO Nanostructures as Promising Photocatalysts. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2016, 18, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X. Nanomaterial ZnO Synthesis and Its Photocatalytic Applications: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, K.; Rauwel, E.; Estephan, E.; Soares, M.R.; Rauwel, P. Significance of Hydroxyl Groups on the Optical Properties of ZnO Nanoparticles Combined with CNT and PEDOT:PSS. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Zhai, L.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Hu, D.; Pei, F.; Wang, Y.; Miao, K. Morphology Effect on the Piezocatalytic Performance of Zinc Oxide: Overlooked Role of Surface Hydroxyl Groups. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 182, 115620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Fundamentals of zinc oxide as a semiconductor. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantò, F.; Dahrouch, Z.; Saha, A.; Patanè, S.; Santangelo, S.; Triolo, C. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by porous zinc oxide nanofibers prepared via electrospinning: When defects become merits. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.