Abstract

Limited functional solubility of peroxidases in Escherichia coli (E. coli) remains a pervasive bottleneck for their application in biocatalytic processes such as tryptophan hydroxylation. Here, a peroxidase (Kerl) with poor solubility derived from Candidatus Entotheonella factor was selected as the model enzyme to address this bottleneck. Fusion tag screening identified NusA as the optimal solubility enhancer, enabling soluble expression with preserved activity. Structure-guided mutagenesis was performed to identify residues involved in catalytic enhancement and substrate preference. Variant I284Q exhibited a 2.67-fold increase in catalytic efficiency, and residue R275 was identified as a key determinant of substrate discrimination. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were further employed to elucidate the structural basis the improved catalytic performance. This study presents an integrated framework for solubility enhancement and functional optimization of peroxidases.

1. Introduction

Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH, E.C 1.14.16.4), a rate-limiting enzyme in serotonin biosynthesis, has attracted significant attention across the fields of neurobiology, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology [1]. The most extensively studied tryptophan hydroxylases are of eukaryotic origin, particularly from mammals [1,2,3]. These enzymes function as tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-dependent monooxygenases, catalyzing hydroxylation through continuous cofactor regeneration. However, this strict dependence on BH4 and associated electron transfer machinery poses a major obstacle for their applications in heterologous hosts and in vitro biocatalysis.

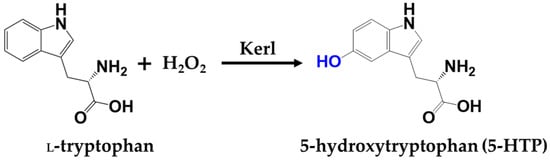

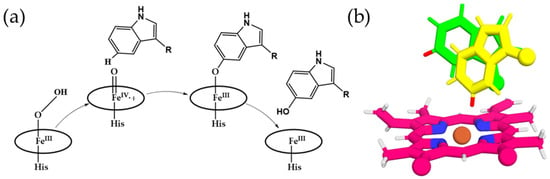

Recently, a distinct class of peroxidase was identified, which feature histidine-ligated heme cofactors and the ability to catalyze the hydroxylation of ʟ-tryptophan using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as the sole oxidant (Scheme 1) [4]. Broadly distributed in prokaryotic metabolic pathways, these enzymes bypass the need for BH4 and offer promising alternative for simplified biocatalytic systems. They operate via a heme-dependent peroxidase-like mechanism, in which H2O2 serves as terminal oxidant to generate a high-valent iron-oxo species (Compound I) that drives ʟ-tryptophan hydroxylation [5,6]. In contrast to P450s, which require NAD(P)H and redox partners, peroxidases depend solely on H2O2 as oxidant, enabling more straightforward reaction setups and higher operational simplicity [6]. Moreover, cofactors such as l-ascorbic acid or its oxidized derivatives can facilitate O2 activation and stabilize the heme center, thereby minimizing peroxide-induced degradation and enhancing catalytic efficiency [5]. In addition, peroxidases are broadly distributed across domains of life, such as bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals [7,8,9,10]. Within these systems, peroxidases mediate a broad spectrum of H2O2-driven oxidative transformations, encompassing chemically diverse substrates such as phenols, indoles, and amines [7,8,9,10]. Accordingly, identifying representative peroxidase system with tractable expression and catalytic activity provides a valuable entry point for engineering efforts.

Scheme 1.

Key transformation in this study.

Nevertheless, practical applications of peroxidase remain challenging, owing to limitations in achieving soluble and functional expression in heterologous systems. Many peroxidases are derived from poorly characterized or genetically intractable organisms, possessing complex structural features, alongside reliance on post-translational modifications. When expressed in E. coli, they undergo misfolding or aggregation, leading to inclusion body formation and loss of catalytic activity [11,12,13,14]. Although some fungal- and plant-derived peroxidases have been successfully expressed in yeast systems, their long cultivation periods remain a major obstacle for protein engineering and high-throughput optimization [15,16]. Combined with the limited success of achieving soluble and functional expression, these challenges continue to hinder the broader deployment of peroxidase.

Fusion-based expression strategies have been extensively employed to improve solubility of recalcitrant enzymes. For instance, fusion with maltose-binding protein (MBP) markedly increased the soluble yield of TPH in E. coli [17]. Other solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., transcription termination/antitermination protein (NusA), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)) have been effectively applied to facilitate the expression of structurally complex enzymes, including glycosyltransferases and dioxygenases [11,18,19,20]. However, systematic expression optimization has rarely been applied to peroxidases, leaving their tractability and catalytic potential inadequately explored.

To address these bottlenecks, a representative peroxidase Kerl, derived from Candidatus Entotheonella factor, was selected for systematic investigation due to poor soluble expression in E. coli [4]. We developed a comprehensive engineering strategy involving the screening of multiple solubility-enhancing fusion tags to achieve functional expression. Structure-guided targeted mutagenesis was employed to identify residues critical for catalytic efficiency and substrate recognition. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations were further utilized to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving functional improvements. This work paves a foundation for effective engineering and application of peroxidases.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Enhancement of Soluble Expression Through Fusion Tag Engineering

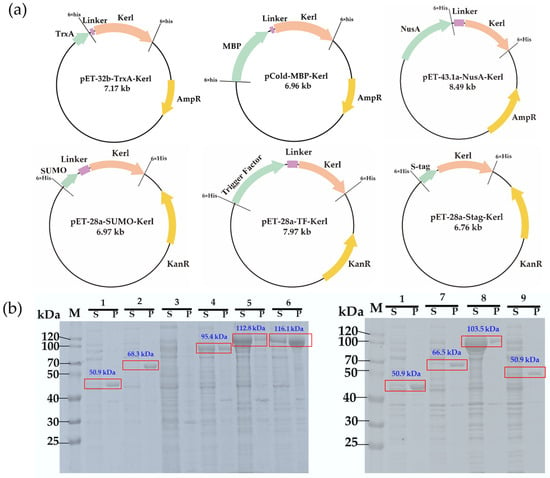

To improve the soluble expression of Kerl, six fusion tags were evaluated, including thioredoxin (TrxA), maltose-binding protein (MBP), transcription termination/antitermination protein (NusA), small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO), trigger factor (TF), and S-tag (Figure 1a). These tags have been widely applied to facilitate the expression of difficult-to-fold proteins. For instance, MBP helps prevent hydrophobic protein aggregation, TrxA promotes correct disulfide bond formation, SUMO enhances protein expression and facilitates correct folding, NusA slows the translation to support proper folding, and TF acts as a passive holding chaperones during protein folding [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Corresponding fusion constructs were designed and assembled into expression vectors (Figure 1a). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis demonstrated that the NusA and TF tag led to the most significant improvement in soluble expression, whereas TrxA, MBP, SUMO and S-tag showed only moderate enhancement (Figure 1b). The superior performance of NusA may be attributed to its larger size and strong intrinsic solubility, which likely attenuates translational elongation of Kerl during translation and folding [22]. Compared with other tags tested, only NusA–Kerl (1.15) exhibited kcat/Km values comparable to Kerl (0.93) (Figures S1 and S2), indicating this fusion strategy successfully enhanced solubility without compromising function. Additionally, the UV–visible spectrum of the NusA–Kerl fusion protein confirmed successful heme incorporation (Figure S3). Furthermore, the heme concentration in crude enzymes was quantified using a pyridine hemochrome assay, revealing 9.61 ± 0.67 μM heme in the 200 mg/mL lysate supernatant (wet weight). Under purified conditions, 20 μM enzyme contained 3.02 ± 0.09 μM heme, indicating efficient heme incorporation during expression and purification. Given its superior performance, NusA–Kerl was selected for subsequent studies.

Figure 1.

Construction and soluble expression analysis of Kerl with different solubility tags. (a) Plasmid maps of TrxA–Kerl, MBP–Kerl, NusA–Kerl, SUMO–Kerl, Trigger Factor–Kerl and Stag–Kerl. (b) SDS-PAGE analysis. Lanes: 1, Kerl (pET-24a); 2, TrxA–Kerl (pET-32b); 3, BL21(DE3) host; 4, MBP–Kerl (pCold); 5, NusA–Kerl (pET-43.1a); 6, NusA–Kerl (pET-28a); 7, SUMO–Kerl (pET-28a); 8, Trigger Factor–Kerl (pET-28a); 9, Stag–Kerl (pET-28a). M indicates marker. S indicates supernatant fraction. P indicates precipitant fraction.

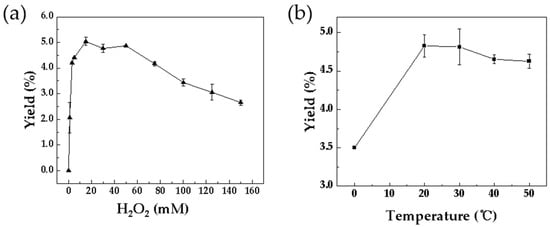

2.2. Effect of H2O2 Concentration and Temperature

H2O2 concentration is a key determinant of catalytic performance, enhancing activity at optimal levels while causing inhibition at elevated concentrations [5]. It was observed that catalytic efficiency increased significantly with rising H2O2 concentration, reaching a maximum at 15 mM (Figure 2a). Beyond this concentration, a clear inhibitory trend was observed, likely attributable to heme degradation or oxidation of active-site residues [5], resulting in a final turnover number of 15.12 before enzyme deactivation.

Figure 2.

Optimization of reaction conditions catalyzed by Kerl. (a) H2O2 concentration: 200 µL reaction solution containing 3 mM ʟ-tryptophan and 10 µM enzyme with 0–150 mM H2O2, incubated at 30 °C for 10 min. (b) Temperature: same solution with 15 mM H2O2, incubated at 0–50 °C for 10 min. Data are from three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD.

Temperature also plays a critical factor in peroxidase activity, primarily through its effect on protein stability during catalysis. The conversion increased progressively with temperature, peaking between 20 °C and 30 °C (Figure 2b). Further elevation beyond this range resulted in a noticeable decline in activity, presumably due to thermal destabilization of the enzyme. This observation is consistent with that of typical mesophilic peroxidases, which exhibit stable catalytic efficiency within a narrow temperature range [26,27]. Accordingly, 30 °C was selected as the optimum temperature for subsequent assays.

2.3. Identification of Key Residues

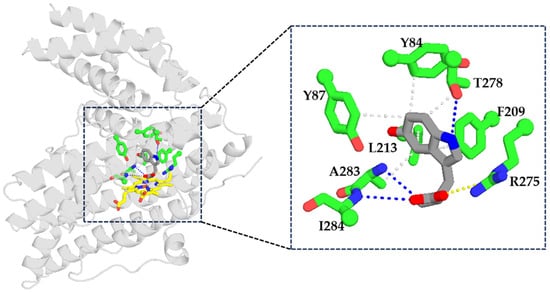

To identify key residues involved in the catalytic process, molecular docking simulations were performed (Figure 3, Table S1). The indole moiety of ʟ-tryptophan was stabilized by extensive hydrophobic interactions with Y84, Y87, F209, L213, T278, and A283. In addition, T278 formed a hydrogen bond (3.9 Å) with the indole nitrogen, while R275 established a salt bridge (5.4 Å) with the carboxylate group of substrates. Hydrogen bonds were also observed between ʟ-tryptophan and A283 (3.8 Å) as well as I284 (4.1 Å), underscoring their importance in substrate positioning. Subsequently, alanine-scanning mutagenesis was conducted to assess the catalytic contribution of these residues. Consistent with the docking results, no product formation was detected for all variants (Y84A, Y87A, F209A, L213A, I284A), with the exception of T278A, which exhibited only trace activity (0.12%). These findings confirm the essential role of these residues in the catalytic mechanism.

Figure 3.

Analysis of key interactions between Kerl and 5-hydroxytryptophan. Blue dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds, yellow dashed lines represent salt bridges, and gray dashed lines represent hydrophobic interactions. Substrates: gray sticks; residues: green sticks; heme: yellow sticks. oxygen atoms: red; nitrogen atoms: blue.

2.4. Identification of Beneficial Variants via HESI-Screening

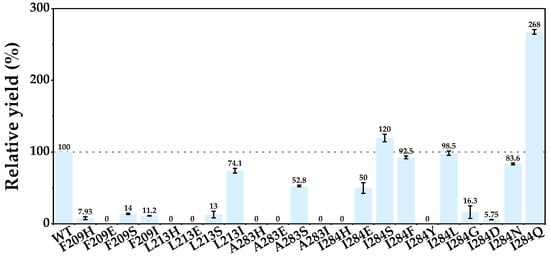

To further explore the catalytic potential of the above key residues, HESI-scanning mutagenesis was performed at positions F209, L213, A283, and I284 (Figure 4). HESI consists of four amino acids─histidine (H, basic polar), glutamate (E, acidic), serine (S, neutral polar), and isoleucine (I, hydrophobic)─each representing a distinct side-chain properties. Most variants, including F209I (11.2%), L213S (13%), and A283I (0%), exhibited significantly reduced relative conversion compared to WT, indicating that these positions are structurally constrained and sensitive to alterations in side-chain perturbations. A notable exception was L213I, which retained 74.1% relative activity, likely due to the preservation of hydrophobic and local steric compatibility.

Figure 4.

HESI scanning at F209, L213, A283, and I284 of Kerl. Reactions were conducted in 200 µL mixtures containing 3 mM ʟ-tryptophan, 10 µM purified enzyme, and 15 mM H2O2 at 30 °C for 10 min. Relative yield = Yield of variant/Yield of WT. Data are from three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD.

Among tested residues, I284 exhibited the highest mutational tolerance. Substitutions such as I284S (120%), I284E (50%), and I284F (92.5%) maintained moderate conversion despite variations in polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity. Based on this observation, saturation mutagenesis was performed at I284, leading to the identification of I284Q, which exhibited a 2.68-fold increase in conversion relative to WT. These results suggest that I284 serves as a tunable site capable of modulating catalytic efficiency through side-chain remodeling.

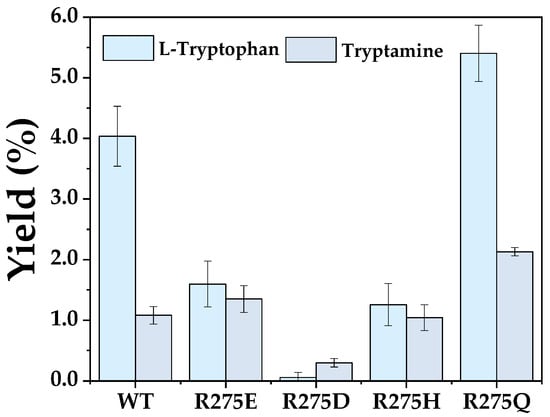

2.5. Engineering Substrate Selectivity

Within the serotonin pathway, both ʟ-tryptophan and tryptamine serve as intermediates. To ensure efficient flux toward the desired product, effective biocatalyst must discriminate between these competing substrates. Accordingly, molecular docking was conducted to elucidate the structural basis of substrate selectivity, revealing a salt bridge between the guanidinium group of R275 and the carboxyl group of ʟ-tryptophan (Figure 3). This electrostatic interaction plays a critical role in substrate positioning and stabilization. In contrast, tryptamine lacks a carboxyl group and cannot participate in this specific interaction, providing a structural rationale for the observed substrate discrimination. Consistent with this model, Kerl displayed a strong preference for ʟ-tryptophan, with only 26.8% relative yield toward tryptamine (Figure 5). To validate the functional role of R275, a series of variants differing in charge and physicochemical properties were constructed. Variants R275E and R275D, both carrying negatively charged side chains, exhibited dramatically reduced activity toward ʟ-tryptophan (1.60% and 0.06%, respectively) and tryptamine (1.35% and 0.30%, respectively), indicating that charge reversal severely disrupted substrate binding. Similarly, R275H (bearing positive charge) also abolished substrate selectivity with comparably reduced activity toward both ʟ-tryptophan (1.26%) and tryptamine (1.04%), likely due to geometric or electrostatic mismatch. In contrast, R275Q, featuring polar side chains, significantly enhanced conversion of both ʟ-tryptophan (134.1% [Relative to WT]) and tryptamine (197.3% [Relative to WT]), indicating enhanced substrate accommodation [28].

Figure 5.

Analysis of substrate preference of R275 variants between ʟ-tryptophan and tryptamine. Reactions were conducted in 200 µL mixtures containing 3 mM ʟ-tryptophan or tryptamine, 10 µM purified enzyme, and 15 mM H2O2 at 30 °C for 10 min. Data are from three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD.

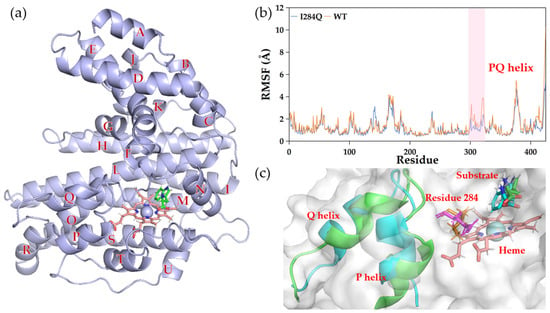

2.6. MD Simulations Analysis

To investigate the underlying mechanism of enhanced catalytic efficiency of variant I284Q, MD simulations were conducted. Peroxidase Kerl is predominantly α-helical in structure, with its helices designated A through U (Figure 6a). Compared with WT, I284Q exhibited a marked shift in RMSF values (residues 302–323), indicating altered flexibility of helices P and Q (Figure 6b,c). The changed mobility of this helical segment prompted us to investigate the changes in interactions between the I284Q mutation and the P-Q region. In WT, residue I284 engages in alkyl interactions with the P-Q region, whereas these interactions are significantly weakened in the Q284 mutant (Figure S4). This disruption likely induced a conformational shift in the P-Q region [29,30], thereby enlarging the substrate access channel and facilitating the enhanced conversion observed with the variant.

Figure 6.

Dynamic influence of I284Q on substrate channel. (a) Representative snapshot of WT from the MD simulations. (b) RMSF analysis. (c) Conformational shift of helices P and Q (residues 302–323). Residue 284 is shown as sticks: orange for I284 (WT); magenta for Q284 (variant I284Q). P-Q region is shown as cartoon: green for WT; blue for variant.

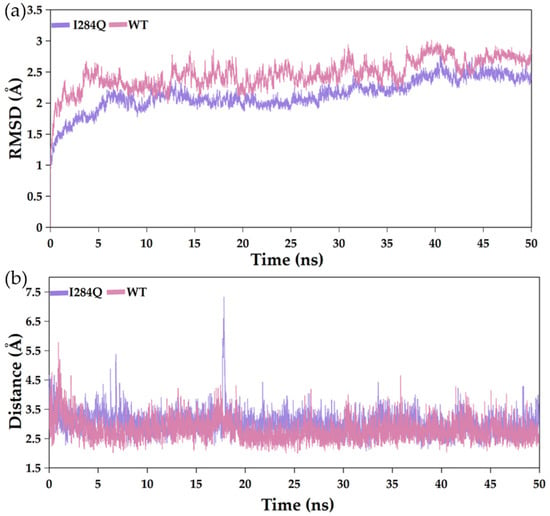

RMSD analysis revealed that both WT and I284Q reached equilibrium within 50 ns (Figure 7a). Notably, I284Q consistently exhibited lower RMSD values than those of WT throughout simulations, suggesting reduced global conformational fluctuations and more rigid overall fold. This trend indicated that I284Q adopts more rigid and conformationally stable global architecture during catalysis. In the enzymatic reaction, the high-spin iron atom of the heme cofactor oxidizes the C5 position of ʟ-tryptophan (Figure 8a). To understand the structural basis of the enzyme’s regioselectivity, the conformational changes between the heme and the ʟ-tryptophan were analyzed. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed rapid conformational rotation of ʟ-tryptophan (Figure 8b). Starting from the energy-minimized structure, the final conformation positioned the hydroxylation site closer to the iron atom, providing explanation for the strict regioselectivity of the enzyme toward 5-hydroxytryptophan over the 4- or 6-hydroxytryptophan products (Figure S5) [30]. To further probe local dynamics, the distance between the heme iron and the abstracted hydrogen atom was analyzed (Figure 7b, Figure 8 and Figure S6). Although both systems maintained relatively stable Fe–H distances, the average in I284Q (3.02 Å) was slightly longer than that of WT (2.79 Å). Such increased variability reflects enhanced flexibility within the catalytic pocket, which may promote more favorable substrate orientation toward the Fe(IV)=O intermediate by allowing more open active-site conformation.

Figure 7.

RMSD trajectories (a) and Fe–H distances (b) of WT and I284Q during 50 ns MD simulations. Fe–H: distance between heme iron and abstracted hydrogen of ʟ-tryptophan.

Figure 8.

Mechanistic insights and conformational dynamics of ʟ-tryptophan hydroxylation by the peroxidase. (a) Catalytic mechanism of the heme-dependent peroxidase [4]. (b) Conformational changes in l-tryptophan observed in molecular dynamics simulations: initial energy-minimized structure (green) and the conformation at 30 ns (yellow).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Strains and Chemicals

E. coli BL21(DE3) was employed for expression of recombinant proteins. Kerl (GenBank accession: ETX03404.1) was codon-optimized for expression and synthesized by SYNBIO Technologies (Suzhou, China). The gene was subsequently cloned into the pET-24a(+) vector between BamHI and XhoI restriction sites. 5-hydroxytryptophan was purchased from Shanghai Meryer Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and ʟ-tryptophan and tryptamine were obtained from J&K Scientific Ltd. (Beijing, China). PrimeSTAR Max DNA polymerase and PCR reagents were provided by Vazyme Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China).

3.2. Gibson Assembly

Plasmids pET-28a(+), pET-32b(+), pET-43.1a(+), and pCold I-MBP were sourced from laboratory stocks. Gibson Assembly was performed using linearized plasmid backbones and PCR-amplified inserts with 20–30 bp overlapping ends [31]. Equal volumes of vector and insert DNA were mixed and treated with T5 exonuclease (New England Biolabs, Beijing, China) at 40 °C for 30 min. The reaction facilitated exonuclease-mediated end resection, annealing of complementary overhangs, and in situ ligation. The assembled products were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells by heat shock. Positive clones were screened by colony PCR, and plasmids containing inserts of the expected size were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Primers designed for Gibson Assembly were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China, Table S2).

3.3. Saturation Mutagenesis

Saturation mutagenesis of selected residues was performed using whole-plasmid PCR using NusA-Kerl-pET-28a(+) as a template. Primers for site saturation mutagenesis were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China, Table S3). PCR amplification was carried out using PrimeSTAR Max DNA polymerase (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), with complementary primer pairs containing degenerate codons at the targeted sites.

The PCR program was carried out with initial denaturation at 98 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Final extension was performed at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were treated with 1 μL DpnI at 37 °C for 30 min to digest the methylated parental plasmids. A 10 μL aliquot of the reaction mixture was then transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells by heat shock.

Transformed colonies were selected on LB agar plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL). Positive clones were picked and grown in LB medium for plasmid isolation, and the presence of target mutations was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

3.4. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Enzymes

Recombinant strains were inoculated into 5 mL LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin or ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 12 h. The seeding cultures were transferred at 2% (v/v) into 100 mL 2 × LB medium and grown at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, final concentration 0.15 mM), ferrous sulfate (final concentration 1 mM), and 5-acetamidopentanoic acid hydrochloride (final concentration 1 mM).

After 20 h induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8228× g for 5 min at 4 °C and resuspended in lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, and 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). Cell lysis was performed by ultrasonication, followed by centrifugation at 8228× g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. Proteins were purified by gradient elution with imidazole (50–500 mM). After elution of nonspecific proteins at 50 mM, the target protein was collected at 400 mM. The eluate was further concentrated using 50 kDa cutoff centrifugal filters (Millipore, Burlington, VT, USA) at 2061× g for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein purity was analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). The UV–visible spectra of peroxidases were obtained using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (BioTEK PowerWave XS2, Winooski, VT, USA) with the Gen5 3.03 software.

3.5. Hydroxylation Assay and Product Analysis

Hydroxylation reactions were performed in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes at a total volume of 100 μL, containing 3 mM ʟ-tryptophan, 15 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and 10 μM purified enzyme in reaction buffer. The reactions were initiated by the addition of H2O2 and incubated at 30 °C for 10 min under aerobic conditions. Reactions were quenched by the addition of three volumes of methanol (300 μL), followed by vortexing for 10 s. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to remove precipitated proteins, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter prior to analysis.

Subsequent analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1260 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, City of Santa Clara, CA, USA) system equipped with Diamonsil C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Beijing, China). A gradient elution was employed with solvent A (water added 0.05% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile added 0.05% formic acid) at flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The gradient profile was set as follows: 0 min (5% B), 12 min (49% B), 13 min (95% B), and 14 min (5% B), held at 5% B until 19 min. The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, and detection was performed at 280 nm with an injection volume of 10 μL. All reactions were analyzed in duplicate unless otherwise stated.

The product 5-hydroxytryptophan was characterized by UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Separation was performed on the WATERS ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a BEH C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 µm) using methanol and water as mobile phase. Mass spectrometric detection was conducted on a Waters MALDI SYNAPT Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), scanning over the m/z range of 20–2000.

3.6. Optimization of Reaction Conditions

The optimal concentration of hydrogen peroxide was determined by varying H2O2 from 0 to 150 mM in 200 μL reaction mixtures containing 3 mM ʟ-tryptophan and 10 μM purified enzyme. The optimal temperature was assessed by pre-incubating the enzyme at 0–50 °C for 30 s, followed by the addition of substrate and H2O2 to initiate the reaction.

3.7. Kinetic Parameter Determination

Kinetic parameters of Kerl and the NusA–Kerl fusion protein were evaluated in 200 μL reactions consisting of 145 μL purified enzyme (10 μM final concentration), 5 μL H2O2 (15 mM final concentration), and 50 μL ʟ-tryptophan at varying concentrations (0.2–6 mM). Reactions were initiated by combining substrate and oxidant with the enzyme, incubated at 30 °C for 30 s, and terminated by the addition of three volumes of methanol. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were subjected to HPLC analysis. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to convert 1 μmol of substrate per minute under the specified assay conditions.

3.8. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MD Simulations)

The structure of Kerl was predicted using AlphaFold3 [4,32] with default monomer prediction pipeline. The full-length amino acid sequence (GenBank accession: ETX03404.1) was used as input, and multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) were automatically generated from UniRef90, MGnify, and BFD databases. Five independent models were produced, and the one with the highest predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) and predicted aligned error (PAE) confidence scores was selected for further refinement and subsequent docking studies.

Molecular docking was performed using the CDOCKER module in Discovery Studio 2019. Prior to docking, ʟ-tryptophan was energy-minimized by the CHARMm force field. CDOCKER carries out a grid-based molecular dynamics simulated-annealing search, followed by energy refinement of poses through CHARMm-based minimization. Each pose is evaluated by the CDOCKER interaction energy (the negative of the receptor–ligand interaction energy); thus, higher CDOCKER score indicates a more favorable binding conformation. Among generated poses, the one with the highest CDOCKER interaction energy (most negative binding energy) and chemically reasonable orientation toward the heme group was selected for further MD simulations.

MD simulations were conducted using GROMACS 2021 with Amber ff14SB force field. Hydrogen atoms were added at physiological pH (7.4) using the H++ server [33]. The heme Fe coordination center was parameterized using MCPB.py, and its geometry was optimized at the B3LYP/def2-SVP level of theory within the Gaussian 16 package [34,35]. Partial charges for the Fe(III)–porphyrin complex were derived from the RESP fitting of electrostatic potentials calculated at the same level of theory [34,35]. The protein–substrate complex was placed in a truncated octahedral box of TIP3P water molecules extending at least 10 Å from any solute atom, and Na+/Cl− ions were added to neutralize the system and achieve an ionic strength of 0.15 M. The system was first minimized using the steepest descent algorithm (10,000 steps), followed by the conjugate gradient method (10,000 steps). The minimized system was gradually heated from 0 K to 303 K over 200 ps under the NVT ensemble, employing position restraints (10 kcal mol−1 Å−2) on all heavy atoms. Subsequently, a 1 ns NPT equilibration at 1 atm and 303 K was carried out using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat and V-rescale thermostat. Production MD simulations were conducted for 50 ns under periodic boundary conditions with a 2 fs time step. Long-range electrostatics were treated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a cutoff of 10 Å for both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. Each system (WT and I284Q variant) was simulated in triplicate using different initial velocity seeds to ensure statistical robustness. Trajectories were analyzed using cpptraj and VMD, focusing on backbone RMSD, RMSF, Fe–H distances, and conformational changes in the P–Q helical region.

3.9. Pyridine Hemochromagen Assay

Heme concentration was determined using the pyridine hemochrome assay. Cells were lysed by sonication, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (8228× g, 30 min, 4 °C). A cuvette was charged with 150 μL of lysate and 150 μL of Solution I [0.2 M NaOH, 40% (v/v) pyridine, 500 μM potassium ferricyanide]. The resulting solution was thoroughly mixed by pipetting, and the UV-vis spectrum (380–620 nm) of the oxidized FeIII state was recorded immediately. Subsequently, 3 μL of a 0.5 M aqueous sodium dithionite solution was added. After thorough mixing, the UV–visible spectrum of the reduced FeII state was recorded immediately. The heme concentration was calculated using Beer–Lambert law, with the differential extinction coefficient for heme, ε[557 nm (reduced) –540 nm (oxidized)] = 23.98 mM−1 cm−1, and by accounting for the dilution factor. The UV–visible spectra of peroxidases were obtained using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (BioTEK PowerWave XS2, Winooski, VT, USA) with the Gen5 3.03 software.

For purified enzyme, the same procedure was applied using 150 μL of the purified protein solution (20 μM enzyme in 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The assay was performed under identical conditions to ensure comparability between crude and purified samples. UV–visible spectra were recorded using a BioTEK PowerWave XS2 spectrophotometer with Gen5 3.03 software.

4. Conclusions

This study established a systematic strategy to enhance functional expression and catalytic performance of the recalcitrant peroxidase Kerl. Fusion tag screening identified NusA as the most effective solubility-enhancing partner, enabling reliable expression without loss of enzymatic activity. Optimal reaction conditions were determined to be 15 mM H2O2 and 30 °C, supporting robust catalytic performance.

Structure-guided mutagenesis revealed several residues essential for activity, among which variants of I284 exhibited notable beneficial effects. Saturation mutagenesis yielded variant I284Q, achieving a 2.68-fold increase in conversion than that of WT. MD simulations reveal that I284Q features altered local hydrophobic packing and re-organized the P–Q helical segment conformation, resulting in increased flexibility within the catalytic pocket and improved substrate accessibility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121133/s1, Table S1: Interactions analysis of WT with 5-hydroxytryptophan using molecular docking; Table S2: Primers for Gibson Assembly; Table S3: Primers for site-directed mutagenesis; Figure S1: LC-MS analysis of 5-hydroxytryptophan produced by Kerl; Figure S2: Kinetic study of Kerl (a) and NusA–Kerl (b) with ʟ-tryptophan in the presence of H2O2 (15 mM); Figure S3: UV-visible spectra of recombinant enzyme (NusA–Kerl); Figure S4: Interactions of P-Q region with residue 284 in WT (a) and I284Q variant (b); Figure S5: HPLC analysis of Kerl with H2O2 or ascorbate, O2; Figure S6: Distance between FE and the attacked hydrogen atom of ʟ-Tryptophan; Nucleotide Sequrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and B.W.; investigation and resources, X.L. and J.D.; data curation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, B.W., U.S., R.H. and Y.N.; supervision, R.H. and Y.N.; funding acquisition, Y.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Advanced Technology Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Province (BF2025072), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22377040), the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu and supported by the Jiangsu Basic Research Center for Synthetic Biology (Grant No. BK20233003), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP202416001), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX24_2581) for the financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the support from the high-performance computing cluster platform of the School of Biotechnology, Jiangnan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, Y.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, Y. Engineering Bacterial Phenylalanine 4-Hydroxylase for Microbial Synthesis of Human Neurotransmitter Precursor 5-Hydroxytryptophan. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, P.F. Tetrahydropterin-Dependent Amino Acid Hydroxylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999, 68, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Yang, L.; Kim, S.H.; Wulff, T.; Feist, A.M.; Herrgard, M.; Palsson, B.Ø. Directed Metabolic Pathway Evolution Enables Functional Pterin-Dependent Aromatic-Amino-Acid Hydroxylation in Escherichia Coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, G.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, M.; Du, Y.-L. Hydroxytryptophan Biosynthesis by a Family of Heme-Dependent Enzymes in Bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Jiang, Z.; Kang, L.; Liao, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Li, A. An Efficient Catalytic Route in Haem Peroxygenases Mediated by O2/Small-Molecule Reductant Pairs for Sustainable Applications. Nat. Catal. 2025, 8, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, H.; Guo, D.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Koffas, M.A.G.; Xu, Z. Engineering of Redox Partners and Cofactor NADPH Supply of CYP68JX for Efficient Steroid Two-Step Ordered Selective Hydroxylation Activity. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 238, 106452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, A.; Catucci, G.; Di Nardo, G.; Sadeghi, S.J.; Gilardi, G. Peroxide-Driven Catalysis of the Heme Domain of A. Radioresistens Cytochrome P450 116B5 for Sustainable Aromatic Rings Oxidation and Drug Metabolites Production. New Biotechnol. 2020, 54, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.R.; Lamsa, M.H.; Schneider, P.; Vind, J.; Svendsen, A.; Jones, A.; Pedersen, A.H. Directed Evolution of a Fungal Peroxidase. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duroux, L.; Welinder, K.G. The Peroxidase Gene Family in Plants: A Phylogenetic Overview. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 57, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobisch, M.; Holtmann, D.; Gomez de Santos, P.; Alcalde, M.; Hollmann, F.; Kara, S. Recent Developments in the Use of Peroxygenases – Exploring Their High Potential in Selective Oxyfunctionalisations. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 51, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kang, T.J. Soluble Expression of Horseradish Peroxidase in Escherichia Coli and Its Facile Activation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 126, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, T.-P.; Shen, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhou, J.; Tang, J.; Han, R.; Xu, G.; Schwaneberg, U.; Wang, B.; et al. Rational Engineering of Self-Sufficient P450s to Boost Catalytic Efficiency of Carbene-Mediated C–S Bond Formation. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 5993–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundinger, T.; Spadiut, O. A Comparative Approach to Recombinantly Produce the Plant Enzyme Horseradish Peroxidase in Escherichia Coli. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 248, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ruiz, M.I.; Ayuso-Fernández, I.; Linde, D.; Ruiz-Dueñas, F.J. Chapter Fourteen-Ligninolytic Peroxidases: A Guide for Their Heterologous Expression in E. coli and Protocols to Evaluate Their Activity on Lignin. Methods Enzymol. 2025, 716, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Fu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zong, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Sheng, X.; et al. Engineering the Fungal Peroxygenase for Efficient and Regioselective Hydroxylation of Vitamin Ds and Sterols. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1952–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weert, S.; Lokman, B.C. Heterologous Expression of Peroxidases. In Biocatalysis Based on Heme Peroxidases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 315–333. ISBN 9783642126277. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, J.; Knappskog, P.M.; Pereira, J.; Ekern, T.; Toska, K.; Kuitert, B.B.; Levine, D.; Gronenborn, A.M.; Martinez, A.; Haavik, J. Expression and Purification of Human Tryptophan Hydroxylase from Escherichia Coli and Pichia Pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2004, 33, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Dong, J.; Ni, Y.; Han, R. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction and Semirational Engineering of Glycosyltransferase for Efficient Synthesis of Rare Ginsenoside Rh1. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 7944–7953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veggiani, G.; Giabbai, B.; Semrau, M.S.; Medagli, B.; Riccio, V.; Bajc, G.; Storici, P.; de Marco, A. Comparative Analysis of Fusion Tags Used to Functionalize Recombinant Antibodies. Protein Expr. Purif. 2020, 166, 105505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Almeida, A.; Castro, A.; Domingues, L. Fusion Tags for Protein Solubility, Purification and Immunogenicity in Escherichia Coli: The Novel Fh8 System. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raran-Kurussi, S.; Waugh, D.S. The Ability to Enhance the Solubility of Its Fusion Partners Is an Intrinsic Property of Maltose-Binding Protein but Their Folding Is Either Spontaneous or Chaperone-Mediated. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, U.; Jensen, K.F. NusA Is Required for Ribosomal Antitermination and for Modulation of the Transcription Elongation Rate of Both Antiterminated RNA and MRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12265–12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVallie, E.R.; DiBlasio, E.A.; Kovacic, S.; Grant, K.L.; Schendel, P.F.; McCoy, J.M. A Thioredoxin Gene Fusion Expression System That Circumvents Inclusion Body Formation in the E. Coli Cytoplasm. Nat. Biotechnol. 1993, 11, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.R.; Edavettal, S.C.; Hall, J.P.; Mattern, M.R. SUMO Fusion Technology for Difficult-to-Express Proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Minshull, T.C.; Radford, S.E.; Calabrese, A.N.; Bardwell, J.C.A. Trigger Factor Both Holds and Folds Its Client Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Senaidy, A.M.; Ismael, M.A. Purification and Characterization of Membrane-Bound Peroxidase from Date Palm Leaves (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 18, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed, S.; Ghaemmaghami, F.; Alemzadeh, I. Turnip (Brassica rapa) Peroxidase: Purification and Characterization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 10614–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouhar, F.; Anderson, J.L.R.; Mowat, C.G.; Vorobiev, S.M.; Hussain, A.; Abashidze, M.; Bruckmann, C.; Thackray, S.J.; Seetharaman, J.; Tucker, T.; et al. Molecular Insights into Substrate Recognition and Catalysis by Tryptophan 2,3-Dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, H.; Lin, K.; Hu, S.; Liu, S.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, A. Regioselectivity Switching in CYP107Pdh-Catalyzed VD3 Hydroxylation: A Structure-Guided Approach To Improve Calcidiol Production. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 4160–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Feng, J.; Yin, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.Z.H. Diverse Mechanisms for the Aromatic Hydroxylation: Insights into the Mechanisms of the Coumarin Hydroxylation by CYP2A6. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 16277–16286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.G.; Young, L.; Chuang, R.-Y.; Venter, J.C.; Hutchison, C.A.; Smith, H.O. Enzymatic Assembly of DNA Molecules up to Several Hundred Kilobases. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandakrishnan, R.; Aguilar, B.; Onufriev, A.V. H++ 3.0: Automating PK Prediction and the Preparation of Biomolecular Structures for Atomistic Molecular Modeling and Simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W537–W541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Merz, K.M. MCPB.Py: A Python Based Metal Center Parameter Builder. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian, version 16, revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).