Smart Materials for Carbon Neutrality: Redox-Active MOFs for Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Electrochemical Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental and General Principles of CO2 Electrosorption in MOFs

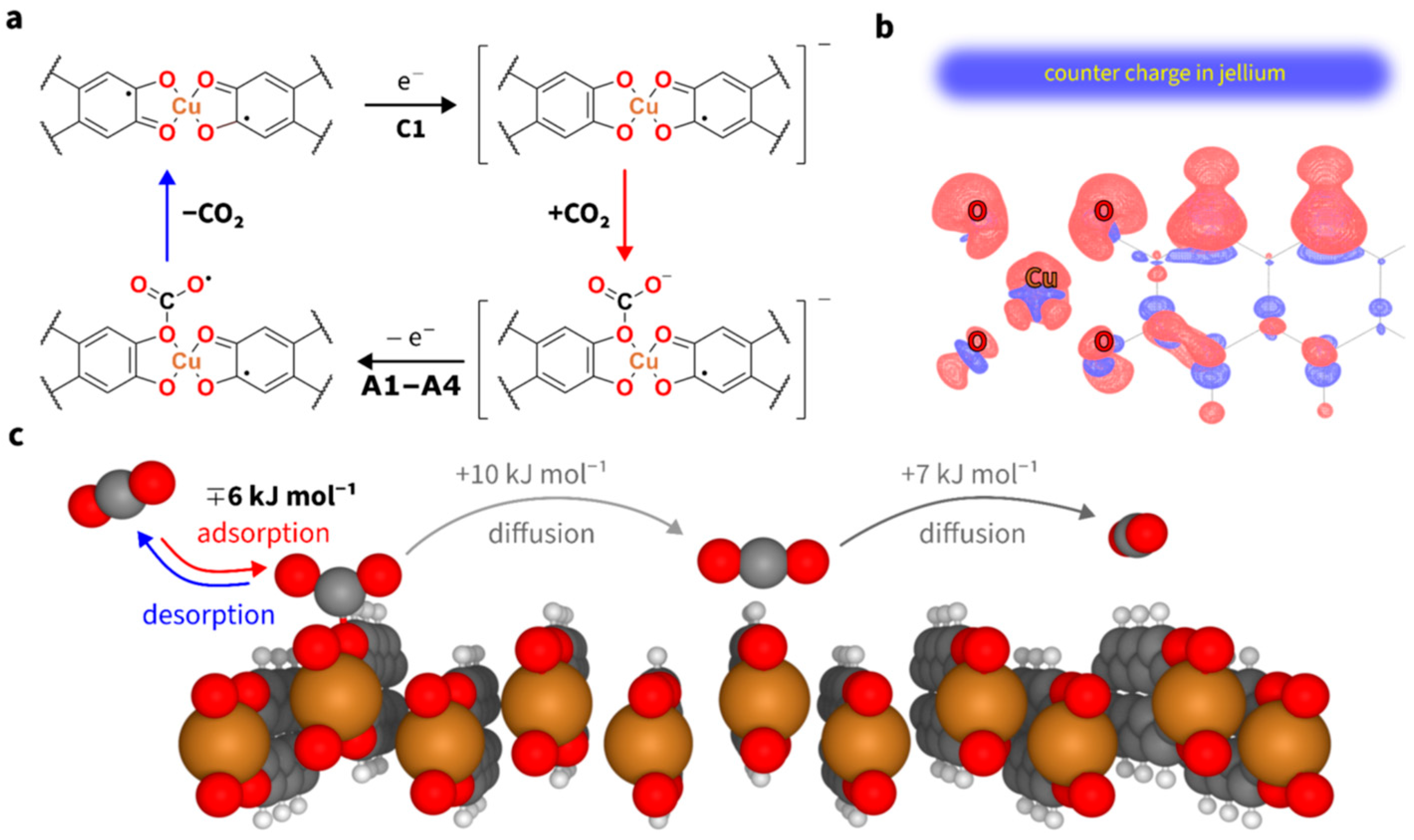

2.1. Redox-Active MOFs as a Platform for Faradaic Electrosorption

2.2. Electrochemical Techniques: Characterization of Redox Activity and Adsorption Dynamics for MOFs in CO2 Capture

2.3. Spectroscopic Techniques: Structural Correlation and Mechanistic Evidence of CO2 in MOFs

3. Redox-Active MOFs as Electrosorbents for CO2: Archetypes and Mechanisms

3.1. Classic Redox MOFs: HKUST-1 and Fe Carboxylates

3.2. Electrosorption in a Two-Dimensional MOF: Cu3(HHTP)2

3.3. Metallic Conductivity in Two-Dimensional Structures: Ni3(HITP)2

3.4. MOF with Ni-bis(Diimine) Units

3.5. Emerging Strategies: Defect Engineering and Doped ZIFs

3.6. Other Redox-Active Families: TTF MOFs, Viologens and Ferrocenes

3.7. Thin Films and Hybrids Are Integrated with MOFs

- (1)

- (2)

- MOF-COF type molecular hybrids: they combined the crystalline porosity of MOFs with the extended π conductivity of COFs, improving mechanical stability and charge mobility [84].

- (3)

- MOF-carbon based composites: dispersion of MOF particles in carbon nanotube or graphene matrices increased conductivity and increased accessibility to active sites [85].

4. Redox-Active MOFs: Proposed Mechanisms of Electrochemical Trapping

4.1. Modulation of Metallic Nodes in MOFs

4.2. Electron Redistribution in π-Conjugated Ligands in MOF-Type Systems

4.3. Strongly Redox Ligands: TTF and Viologen

- (i)

- Housing a molecular carrier within a porous structure.

- (ii)

- Incorporating redox-active bonds or nodes so that the structure itself acts as a sorbent.

- (iii)

- Leveraging MOF environments that pre-concentrate and activate CO2 at electrochemically polarized interfaces.

4.4. Ferrocene-Functionalized MOFs as a Redox Tracer for CO2 Capture

4.5. Formation of Intermediate Species in MOFs: Spectroscopic Evidence

4.6. The Role of Defect Engineering and Hybrid Materials in MOFs

4.7. Coordination, Electric Field and Trap Dynamics

4.7.1. Connection with Other MOF Redox Materials

4.7.2. Theoretical Approach and Energy Metrics in MOFs

4.7.3. Mechanistic Gaps and Exploration Opportunities in MOF

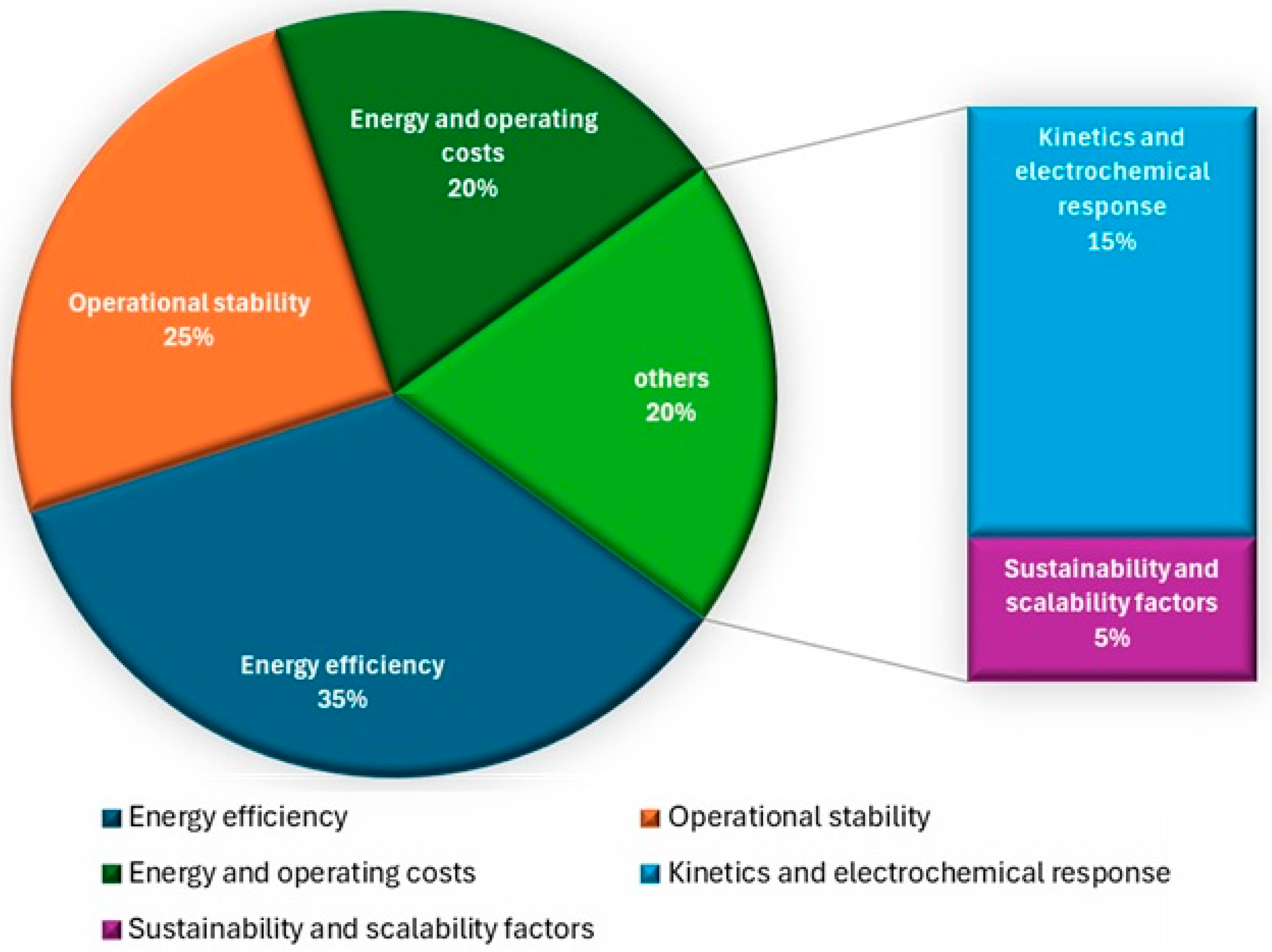

5. Prospects and Challenges of Redox-Active MOFs in CO2 Capture

5.1. Stability and Scalability in MOF for CO2 Capture

5.2. Synergy Between Capture and Electrochemical Conversion in MOFs for CO2

5.3. Standardization, Advanced Design, and Predictive Modeling of MOFs in CO2 Capture

5.4. Cross-Sectional Comparison and Sustainability of MOFs for CO2 Capture

- -

- Standardized electrochemical and spectroscopic protocols that quantify CO2 capture in a manner comparable to electrocatalysis and thermal CCS.

- -

- Design strategies that integrate nodes (monometallic or multimetallic) and redox-active ligands with stable and hydrotolerant structures.

- -

- Predictive models that decipher the electronic descriptors in CO2 capture performance.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, H.; Dickinson, E.J.F.; Lu, X.; Bexell, U.; Proch, S.; Moffatt, C.; Stenström, M.; Smith, G.; Hinds, G. Assessing potential profiles in water electrolysers to minimise titanium use. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaç, E.P.; Zhou, K.; Rong, W.; Salamon, S.; Landers, J.; Wende, H.; Smith, R.D.L. Identification of non-traditional coordination environments for iron ions in nickel hydroxide lattices. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Murdock, C.R.; Didas, S.A.; Jones, C.W. Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, R.; Wagterveld, R.M.; Digdaya, I.A.; Xiang, C.; Vermaas, D.A. Electrochemical carbon dioxide capture to close the carbon cycle. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 781–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, S.E.; Starr, D.E.; Strasser, P. Electrochemical Approaches toward CO2 Capture and Concentration. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 13058–13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, P.; Wang, Z.; Kang, P. Zinc Imidazolate Metal–Organic Frameworks (ZIF-8) for Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO. Chemphyschem 2017, 18, 3142–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albo, J.; Vallejo, D.; Beobide, G.; Castillo, O.; Castaño, P.; Irabien, A. Copper-Based Metal–Organic Porous Materials for CO2 Electrocatalytic Reduction to Alcohols. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.-X.; Qian, S.-L.; Bu, F.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Feng, L.-G.; Teng, Y.-L.; Liu, W.-L.; Li, Z.-W. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO by a Heterogeneous Catalyst of Fe–Porphyrin-Based Metal–Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 4662–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohland, P.; Schröter, E.; Nolte, O.; Newkome, G.R.; Hager, M.D.; Schubert, U.S. Redox-active polymers: The magic key towards energy storage—A polymer design guideline progress in polymer science. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 125, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetik, I.; Žoglo, N.; Kosimov, A.; Cepitis, R.; Krasnenko, V.; Qing, H.; Chandra, P.; Mirica, K.; Rizo, R.; Herrero, E.; et al. Advancing Electrochemical CO2 Capture with Redox-Active Metal-Organic Frameworks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.16444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, U.S.; Winter, A.; Newkome, G.R. An Introduction to Redox Polymers for Energy-Storage Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/An+Introduction+to+Redox+Polymers+for+Energy-Storage+Applications-p-9783527350902 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talin, A.A.; Centrone, A.; Ford, A.C.; Foster, M.E.; Stavila, V.; Haney, P.; Kinney, R.A.; Szalai, V.; El Gabaly, F.; Yoon, H.P.; et al. Tunable Electrical Conductivity in Metal-Organic Framework Thin-Film Devices. Science 2014, 343, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, A.A.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Aljama, H.; Montoya, J.H.; Yoo, J.S.; Tsai, C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Studt, F.; Nørskov, J.K. Understanding trends in C–H bond activation in heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheberla, D.; Bachman, J.C.; Elias, J.S.; Sun, C.-J.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Dincă, M. Conductive MOF electrodes for stable supercapacitors with high areal capacitance. Nat. Mater. 2016, 16, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Godfrey, H.G.W.; da Silva, I.; Cheng, Y.; Savage, M.; Tuna, F.; McInnes, E.J.L.; Teat, S.J.; Gagnon, K.J.; Frogley, M.D.; et al. Modulating supramolecular binding of carbon dioxide in a redox-active porous metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, U.; Siahrostami, S. Copper-based metal–organic frameworks for CO2reduction: Selectivity trends, design paradigms, and perspectives. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 3740–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doheny, P.W.; Babarao, R.; Kepert, C.J.; D’aLessandro, D.M. Tuneable CO2 binding enthalpies by redox modulation of an electroactive MOF-74 framework. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ling, J.; Lai, Y.; Milner, P.J. Redox-Active Organic Materials: From Energy Storage to Redox Catalysis. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-Y.; Lee, J.S. Challenges in Developing MOF-Based Membranes for Gas Separation. Langmuir 2023, 39, 2871–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.A.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H.-C.; Morsali, A. Tuning redox activity in metal–organic frameworks: From structure to application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 517, 216004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffo, G.; Tamo, A.K.; Fotsop, C.G.; Tchoumi, H.H.B.; Talla, D.E.N.; Wabo, C.G.; Deussi, M.C.N.; Temgoua, R.C.T.; Doungmo, G.; Njanja, E.; et al. Metal-organic framework-based materials: From synthesis and characterization routes to electrochemical sensing applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 536, 216680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Qiu, W.; Zhou, S.-H.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhu, Q.-L. First-principles calculation studies of metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives for electrochemical energy conversion and storage. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 544, 216982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.D.; Gargate, N.; Tiwari, M.S.; Nadar, S.S. Defect metal-organic frameworks (D-MOFs): An engineered nanomaterial for enzyme immobilization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 531, 216519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, L.; Liang, Y.; Hou, J.; Chen, J. Defect-containing metal–organic framework materials for sensor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 12, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaran, M.K.; Govindaraj, M.; Kogularasu, S.; Sriram, B.; Raja, B.K.; Wang, S.-F.; Chang-Chien, G.-P.; J, A.S. Recent advances in metal-organic frameworks for electrochemical sensing applications. Talanta Open 2025, 11, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, I.; Goryachev, A.; Digdaya, I.A.; Li, X.; Atwater, H.A.; Vermaas, D.A.; Xiang, C. Coupling electrochemical CO2 conversion with CO2 capture. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, T.; An, L.; Xia, C.; Zhang, X. Integration of CO2 Capture and Electrochemical Conversion. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 2840–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, K.; Yu, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, H.; Xia, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; et al. Review of electrochemical carbon dioxide capture towards practical application. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Mapstone, G.; Coady, Z.; Wang, M.; Spreng, T.L.; Liu, X.; Molino, D.; Forse, A.C. Enhancing electrochemical carbon dioxide capture with supercapacitors. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayake, K.; Kularatna-Abeywardana, D. A review of supercapacitors: Materials, technology, challenges, and renewable energy applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holze, R.F.; Béguin, E. Frąckowiak (eds): Supercapacitors—Materials, Systems, and Applications. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2015, 19, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.M.; Clarke, L.E.; Barlow, J.M.; Bím, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ripley, K.M.; Li, C.J.; Kummeth, A.; Leonard, M.E.; Alexandrova, A.N.; et al. Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Capture and Concentration. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 8069–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinhardt, J.H.; Singh, P.; Tarakeshwar, P.; Buttry, D.A. Electrochemical capture and release of carbon dioxide. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Rahimi, M.; Hatton, T.A. Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Capture and Release with a Redox-Active Amine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2164–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Ou, P.; Lee, G.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Shirzadi, E.; Dorakhan, R.; Xie, K.; Tian, C.; et al. A redox-active polymeric network facilitates electrified reactive-capture electrosynthesis to multi-carbon products from dilute CO2-containing streams. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, G.; Naruse, J.; Shingai, H.; Usami, K.; Kajino, T.; Yoto, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Inomata, T.; Masuda, H. Mechanism of CO2 Capture and Release on Redox-Active Organic Electrodes. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 2164–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederichsen, K.M.; Sharifian, R.; Kang, J.S.; Liu, Y.; Kim, S.; Gallant, B.M.; Vermaas, D.; Hatton, T.A. Electrochemical methods for carbon dioxide separations. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ott, S. The Molecular Nature of Redox-Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks. Accounts Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahayaraj, A.F.; Prabu, H.J.; Maniraj, J.; Kannan, M.; Bharathi, M.; Diwahar, P.; Salamon, J. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): The Next Generation of Materials for Catalysis, Gas Storage, and Separation. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2023, 33, 1757–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozaini, M.T.; Grekov, D.I.; Bustam, M.A.; Pré, P. Shaping of HKUST-1 via Extrusion for the Separation of CO2/CH4 in Biogas. Separations 2023, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Aulestia, A.; Trejos, V.M.; Esparza-Schulz, J.M.; Ibarra, I.A.; Sánchez-González, E. Chemically Modified HKUST-1(Cu) for Gas Adsorption and Separation: Mixed-Metal and Hierarchical Porosity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 65581–65591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Meng, Z. Solid-State Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Capture by Conductive Metal–Organic Framework Incorporating Nickel Bis(diimine) Units. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 33093–33103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-M.; Zhang, X.-D.; Huang, J.-Y.; Zheng, D.-S.; Xu, M.; Gu, Z.-Y. MOF-based materials for electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 494, 215333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, T.; Strømme, M.; Xu, C. Electrochemical Doping and Structural Modulation of Conductive Metal-Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202318387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-K.; Meng, Z.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, H.-L. Conductive MOFs for electrocatalysis and electrochemical sensor. eScience 2023, 3, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.; Lv, T.; Geng, P.; Chen, Y.; Pang, H. Recent advances in the type, synthesis and electrochemical application of defective metal-organic frameworks. Energy Mater. 2023, 3, 300022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Saha, A.; Moni, S.; Volkmer, D.; Das, M.C. Anhydrous Solid-State Proton Conduction in Crystalline MOFs, COFs, HOFs, and POMs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 5515–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Khurram, A.; Hatton, T.A.; Gallant, B. Electrochemical carbon capture processes for mitigation of CO2 emissions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8676–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.S.; Kumar, S.S.; Kulandainathan, M.A. Highly selective electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide using Cu based metal organic framework as an electrocatalyst. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 25, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, B.; Su, X.; Klemm, A.; Kim, Y.; Sharada, S.M.; Rodriguez-Katakura, A.; Kron, K.J. Perspective and challenges in electrochemical approaches for reactive CO2 separations. iScience 2021, 24, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinogami, R.; Yotsuhashi, S.; Deguchi, M.; Zenitani, Y.; Hashiba, H.; Yamada, Y. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide using a copper rubeanate metal organic framework. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 2012, 1, H17–H19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskian, S.; Hatton, T.A. Faradaic electro-swing reactive adsorption for CO2 capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3530–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmatifar, A.; Kang, J.S.; Ozbek, N.; Tan, K.-J.; Hatton, T.A. Electrochemically Mediated Direct CO2 Capture by a Stackable Bipolar Cell. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.; Jin, S.; Yang, F.; Alberts, M.; Li, L.; Xi, D.; Gordon, R.G.; Wang, P.; Aziz, M.J.; Ji, Y. A phenazine-based high-capacity and high-stability electrochemical CO2 capture cell with coupled electricity storage. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdinejad, M.; Massen-Hane, M.; Seo, H.; Hatton, T.A. Oxygen-Stable Electrochemical CO2 Capture using Redox--Active Heterocyclic Benzodithiophene Quinone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202412229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, N.A.; Pugh, S.M.; Xu, Z.; Leong, D.C.Y.; Jaffe, A.; Forse, A.C. Quinone-functionalised carbons as new materials for electrochemical carbon dioxide capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 16221–16232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, N.A.; Xu, Z.; Kress, T.; Forse, A.C. Correlating the structure of quinone-functionalized carbons with electrochemical CO2 capture performance. Mater. Today Energy 2024, 45, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Xu, Z.; Muzammil, M.; Bird, S.; Munawar, M.; Salam, F.; Hartley, N.A.; Taylor, J.; Amin, K.; Ling, J.; et al. Electrochemical CO2 Capture by a Quinone-based Covalent Organic Framework. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Bi, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, K.Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Q. Layer-by-Layer 2D Ultrathin Conductive Cu3(HHTP)2 Film for High-Performance Flexible Transparent Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Jung, Y.E.; Yoo, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, C.Y.; Jang, J.H. Facile synthesis of M-MOF-74 (M=Co, Ni, Zn) and its application as an electrocatalyst for electrochemical CO2 conversion and H2 production. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, S.S.-Y.; Lo, S.M.-F.; Charmant, J.P.H.; Orpen, A.G.; Williams, I.D. A Chemically Functionalizable Nanoporous Material [Cu3(TMA)2(H2O)3]n. Science 1999, 283, 1148–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoste, J.B.; Peterson, G.W. Metal–organic frameworks for air purification of toxic chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5695–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamon, L.; Serre, C.; Devic, T.; Loiseau, T.; Millange, F.; Férey, G.; De Weireld, G. Comparative study of hydrogen sulfide adsorption in the MIL-53(Al, Cr, Fe), MIL-47(V), MIL-100(Cr), and MIL-101(Cr) metal−organic frameworks at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8775–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, F.; Oggianu, M.; Auban-Senzier, P.; Novitchi, G.; Canadell, E.; Mercuri, M.L.; Avarvari, N. A highly conducting tetrathiafulvalene-tetracarboxylate based dysprosium(iii) 2D metal–organic framework with single molecule magnet behaviour. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 19247–19263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.; Tan, B.; Figueira, F.; Mendes, R.F.; Calbo, J.; Valente, G.; Escamilla, P.; Paz, F.A.A.; Rocha, J.; Dincă, M.; et al. Mixed Ionic and Electronic Conductivity in a Tetrathiafulvalene-Phosphonate Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Z.Y.; Yao, J.; Boon, N.; Eral, H.B.; Li, D.-S.; Hartkamp, R.; Yang, H.Y. Electrochemical Selective Removal of Oxyanions in a Ferrocene-Doped Metal–Organic Framework. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 29067–29077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, A.D.; Li, C.-H.; Li, S.-G.; Nguyen, T.P.; Kuo, K.-H.M.; Wooley, K.L.; Tabor, D.P.; Lutkenhaus, J.L. Electron transport kinetics for viologen-containing polypeptides with varying side group linker spacing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 31871–31882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hod, I.; Bury, W.; Gardner, D.M.; Deria, P.; Roznyatovskiy, V.; Wasielewski, M.R.; Farha, O.K.; Hupp, J.T. Bias-switchable permselectivity and redox catalytic activity of a ferrocene-functionalized, thin-film metal–organic framework compound. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheberla, D.; Sun, L.; Blood-Forsythe, M.A.; Er, S.; Wade, C.R.; Brozek, C.K.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Dincă, M. High electrical conductivity in Ni3(2,3,6,7,10,11-hexaiminotriphenylene)2, a semiconducting metal–organic graphene analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8859–8862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, T.C.; Su, T.A. Conductivity in Porous 2D Materials Made Crystal Clear. ACS Central Sci. 2020, 6, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirlikovali, K.O.; Goswami, S.; Mian, M.R.; Krzyaniak, M.D.; Wasielewski, M.R.; Hupp, J.T.; Li, P.; Farha, O.K. An Electrically Conductive Tetrathiafulvalene-Based Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Framework. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.-J.; Luo, X.-F.; Xiao, X. Promoting the spatial arrangement of TTF to optimize the photocurrent response of MOFs. J. Solid. State Chem. 2024, 339, 124933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Barman, S.; Rahimi, F.A.; Rambabu, D.; Nath, S.; Maji, T.K. Confining charge-transfer complex in a metal-organic framework for photocatalytic CO2 reduction in water. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X.-X.; Yuan, L.; Li, S.-L.; Lan, Y.-Q. A viologen-functionalized metal–organic framework for efficient CO2 photoreduction reaction. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7507–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, C.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, Q.; Sang, T.; Gai, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, K. Viologen-Based Cationic Metal–Organic Framework for Efficient Cr2O72– Adsorption and Dye Separation. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 5988–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhuo, Y.; Xie, G.; Yuan, R.; Chen, S. Ferrocene covalently confined in porous MOF as signal tag for highly sensitive electrochemical immunoassay of amyloid-β. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8330–8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty, T.; Zingl, A.; Wünschek, M.; Pichler, C.M.; Watkins, M.B.; Roy, S. Structural Reconstruction of a Cobalt- and Ferrocene-Based Metal–Organic Framework during the Electrochemical Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 40814–40824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, A.; Useini, L.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Multi-Ferrocene-Based Ligands: From Design to Applications. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 3007–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Wan, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Hussain, S.; Ye, Z.; Peng, X. Keggin-type polyoxometalates molecularly loaded in Zr-ferrocene metal organic framework nanosheets for solar-driven CO2 cycloaddition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 296, 120329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Castillo, C.; Espinoza-González, R.; Jofré-Ulloa, P.P.; Luis-Sunga, M.; Silva, N.; Suazo-Hernández, J.; Soler, M.; Isaacs, M.; García, G. Enhanced hydrogen generation through electrodeposited non-precious metal Zn/Cu-BTC metal-organic frameworks on indium tin oxide. J. Power Sources 2025, 650, 237480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaramulu, K.; Mukherjee, S.; Morales, D.M.; Dubal, D.P.; Nanjundan, A.K.; Schneemann, A.; Masa, J.; Kment, S.; Schuhmann, W.; Otyepka, M.; et al. Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Framework Hybrids for Applications in Catalysis, Environmental, and Energy Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17241–17338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-M.; Choi, S.Y.; Youn, M.H.; Lee, W.; Park, K.T.; Gothandapani, K.; Grace, A.N.; Jeong, S.K. Investigation on electroreduction of CO2 to formic acid using Cu3(BTC)2 metal–organic framework (Cu-MOF) and graphene oxide. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 23919–23930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, C.; Erucar, I.; Keskin, S. MOF/COF hybrids as next generation materials for energy and biomedical applications. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 7360–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H.; Aksu, G.O.; Gulbalkan, H.C.; Keskin, S. MOF Membranes for CO2 Capture: Past, Present and Future. Carbon. Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. Molecular redox-active organic materials for electrochemical carbon capture. MRS Commun. 2023, 13, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Rasouli, A.S.; Lee, B.-H.; Zhang, J.; Won, D.H.; Xiao, Y.C.; Edwards, J.P.; Jung, E.D.; Sargent, E. CO2 Electroreduction to Multicarbon Products from Carbonate Capture Liquid. Joule 2023, 7, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-R.; Huang, Q.; He, C.-T.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, F.-C.; Lan, Y.-Q. Oriented electron transmission in polyoxometalate-metalloporphyrin organic framework for highly selective electroreduction of CO2. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Seow, J.Y.R.; Skinner, W.S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal-organic frameworks: Structures and functional applications. Mater. Today 2019, 27, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, M.; Santiago-Portillo, A.; Palomino, M.; Vitórica-Yrezábal, I.J.; Vieira, B.J.C.; Waerenborgh, J.C.; Valencia, S.; Navalón, S.; Rey, F.; García, H.; et al. A highly stable and hierarchical tetrathiafulvalene-based metal–organic framework with improved performance as a solid catalyst. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2413–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, C.; Guo, W.; You, B.; Xia, B.Y. Efficient Electroconversion of Carbon Dioxide to Formate by a Reconstructed Amino--Functionalized Indium–Organic Framework Electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19107–19112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Lin, T.; Haq, F.; Vatsadze, S.Z.; Lemenovskiy, D.A. Ferrocene-contained metal organic frameworks: From synthesis to applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 430, 213737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, S.R.; Hall, L.A.; D’aLessandro, D.M. Mechanochemical Impregnation of a Redox-Active Guest into a Metal–Organic Framework for Electrochemical Capture of CO2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 8442–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.F.; Faust, T.B.; Turner, P.; Usov, P.M.; Kepert, C.J.; Babarao, R.; Thornton, A.W.; D’ALessandro, D.M. Enhancing selective CO2 adsorption via chemical reduction of a redox-active metal–organic framework. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 9831–9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McDonald, T.M.; Mason, J.A.; Kong, X.; Bloch, E.D.; Gygi, D.; Dani, A.; Crocellà, V.; Giordanino, F.; Odoh, S.O.; Drisdell, W.S.; et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks. Nature 2015, 519, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.S.; Skorupskii, G.; Dincă, M. Electrically Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8536–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micero, A.; Hashem, T.; Gliemann, H.; Léon, A. Hydrogen Separation Performance of UiO-66-NH2 Membranes Grown via Liquid-Phase Epitaxy Layer-by-Layer Deposition and One-Pot Synthesis. Membranes 2021, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, S.; Geppert, B.; Steinbach, F.; Caro, J. Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66 Layer: A Highly Oriented Membrane with Good Selectivity and Hydrogen Permeance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 12878–12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranchemontagne, D.J.; Mendoza-Cortes, J.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. Secondary building units, nets and bonding in the chemistry of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1257–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonzio, G.; Hankin, A.; Shah, N. CO2 electrochemical reduction: A state-of-the-art review with economic and environmental analyses. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 208, 934–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xiao, R.; Lu, F.; Ke, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, K. Conductivity enhancement mechanism and application of NiCo-MOF hollow sphere electrode materials in lithium-ion batteries. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 6674–6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudert, F.-X. Responsive metal–organic frameworks and framework materials: Under pressure, taking the heat, in the spotlight, with friends. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloni, R.; Lee, K.; Berger, R.F.; Smit, B.; Neaton, J.B. Understanding trends in CO2 adsorption in metal–organic frameworks with open-metal sites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, X.; Shi, S.; Gao, Z.; Yu, J.; Shan, B.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, B.; Shao, C.; Zuo, M.; et al. Two novel MOFs based on viologen ligand: Ammonia vapor sensing and photomagnetic properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1340, 142502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shan, L.; Sheveleva, A.M.; He, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nikiel, M.; Lopez-Odriozola, L.; Natrajan, L.S.; McInnes, E.J.L.; et al. Control of evolution of porous copper-based metal–organic materials for electroreduction of CO2 to multi-carbon products. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H.-Y.; Huang, L.; Ge, J.-Y.; Joseph, E.; Qin, J.; Cagin, T.; Zuo, J.-L.; Zhou, H.-C. Redox-switchable breathing behavior in tetrathiafulvalene-based metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, T.; Wei, Y.-L.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.-K.; Liu, X.-F.; Li, H.-Y.; Zang, S.-Q. A viologen-based multifunctional Eu-MOF: Photo/electro-modulated chromism and luminescence. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13093–13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Li, F.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Q. Metal-organic-framework-based materials as platforms for energy applications. Chem 2024, 10, 86–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Xu, M.; Kang, X.; Wan, Q.; Han, B.; Wu, N.; Zheng, L.; Ma, C. Amorphous NH2-MIL-68 as an efficient electro- and photo-catalyst for CO2 conversion reactions. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-G.; Bigdeli, F.; Panjehpour, A.; Larimi, A.; Morsali, A.; Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Garcia, H. Metal organic framework composites for reduction of CO2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaghani, A.H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, M.; Chen, Z. Promises of MOF-Based and MOF-Derived Materials for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2402278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornienko, N.; Zhao, Y.; Kley, C.S.; Zhu, C.; Kim, D.; Lin, S.; Chang, C.J.; Yaghi, O.M.; Yang, P. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14129–14135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.-L.; Dai, M.-D.; Yang, X.-F.; Yin, H.-J.; Zhang, Y.-W. Copper(II)-Doped Two-Dimensional Titanium-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks toward Light-Driven CO2Reduction to Value-Added Products. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 13981–13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åhlén, M.; Cheung, O.; Xu, C. Low-concentration CO2 capture using metal–organic frameworks—Current status and future perspectives. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.-B.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.-H.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, W.; Jiang, H.-L. Boosting Interfacial Charge-Transfer Kinetics for Efficient Overall CO2 Photoreduction via Rational Design of Coordination Spheres on Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12515–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, M.; Aziz, A.; Di Tommaso, D.; Crespo-Otero, R. Simulating excited states in metal organic frameworks: From light-absorption to photochemical CO2 reduction. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 5388–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Active System/Material | Type of Material/Mechanism | CO2 Medium | Reported Capture Metrics | Key Comment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyanthraquinone–CNT (PAQ–CNT) + PVFc–CNT (Faradaic electro-swing) | Redox polymer (quinone) supported on CNT; reactive electro-swing | Solid-state cell, electrolyte [Bmim] [Tf2N]; gas 0.6–10% v/v CO2 in N2 | Faradaic efficiency ≈ 490%; 40–90 kJ·mol−1 CO2 work; capacity virtually independent of inlet concentration; loss < 30% after 7000 cycles | Iconic demonstration of reactive electro-swing with quinones; high energy efficiency and excellent cyclability | [53] |

| Molecular redox-active amine | Dissolved redox organic molecule (electrochemically mediated capture) | Electrochemical cell with amine redox in organic electrolyte; simulated CO2 currents | Electronic utilization (mol CO2/mol e−) up to 1.25; reversible capture and release over multiple cycles | It shows that a molecular carrier can overcome the 1 CO2/e− limit through chemical design of the amine | [54] |

| 1,8-ESP (phenazine bis-sulfonate) | Phenazine redox molecule; pH-swing cell coupled to electrical storage | Highly soluble aqueous solution (>1.35 M) over a wide pH range; captures from concentrated and dilute streams | Capacity 0.86–1.41 mol CO2·L−1; energy cost 36–55 kJ·mol−1 CO2; capacity degradation < 0.01% per day | Complete CO2 capture with electrochemical storage; key reference in pH-swing cells | [55] |

| BDT-Q (benzodithiophene-quinone) | Redox heterocyclic quinone; stable electrochemical capture in the presence of O2 | Cells with BDT-Q in electrolytes containing O2; CO2 currents with O2 | High stability in the presence of O2; maintains virtually unchanged capture capacity after prolonged cycling (values detailed in the article) | Overcomes one of the bottlenecks of quinones: O2 deactivation | [56] |

| Quinones grafted on porous carbon (f-CMK-3 and others) | Mesoporous carbons covalently functionalized with anthraquinone | Functionalized carbon electrodes in organic/ionic media; CO2 in flow | Significant increase in electrochemical capture capacity compared to non-functionalized carbon; simultaneous improvement in charge storage (specific capacities and faradaic efficiencies reported) | First systematic family of quinone-functionalized carbons for ECC; basis for optimizing structure-performance | [57] |

| Quinone-functionalized carbons (structure-performance study) | A series of porous carbons with varying porosities/surface areas, functionalized with anthraquinone. | Electrodes in different electrolytes; CO2 atmosphere. | All materials exhibit reversible electrochemical capture; capacity and kinetics are correlated with the pore environment; capture energies and kinetic parameters are detailed in the paper. | Clear relationships are established between electrode structure and capture performance. | [58] |

| Anthraquinone COF (COF-AQ) | Conductive organic covalent framework with anthraquinone units | COF electrodes in ionic liquid electrolyte and aqueous media; CO2 in flow | Electrochemical capacity > 2.6 mmol CO2 g−1 COF (≈50% of theoretical capacity); energy ~31 kJ·mol−1 CO2; stable capture for 500 cycles with 99.6% coulombic efficiency | First demonstration of electrochemical CO2 capture with a COF; very high capacity and good stability | [59] |

| Materials | Dominant Mechanism | Main Advantages | Critical Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porous carbons | Capacitive electrosorption (double layer) | High cyclic stability; low cost; wide availability | Limited selectivity; low gravimetric capacity | [4,49] |

| Redox polymers | Faradaic electrosorption on quinone, viologen, etc. groups. | Chemical modularity; high reversibility; selectivity potential | Long-term chemical degradation; limited conductivity | [86,87] |

| Redox-active MOFs | Electron redistribution in metallic nodes and ligands | Molecular selectivity; structural tunability; possibility of integrating capture and conversion | Structural stability; expensive synthesis; limited scalability | [15] |

| MOF/Material | Metal Anode/Redox Ligand | Electrochemical Configuration | CO2 Capture Metrics | Comment on the Role of the MOF | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu3(HHTP)2 (conducting MOF) | Redox-active Cu(II) node; aromatic 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydroxytriphenylene (HHTP) ligand | Cu3(HHTP)2 electrodes in aqueous electrolyte; dissolved and gas-phase CO2; CV, GCD, and DEMS | Capacity of ≈2 mmol CO2 g−1; ΔH_ads ≈ −20 kJ·mol−1; reversible capture/release in redox cycles in water | First MOF to switch its CO2 capture capacity in aqueous electrolytes; The combination of Cu redox + conjugated π-ligand governs electrosorption | [10] |

| Hybrid MOF/quinone (Wenger–D’Alessandro) | Stable MOF framework (Mg-MOF-74 type or other robust analog) mechanochemically impregnated with a redox quinone molecule | MOF + quinone cathode electrodes; potential-dependent controlled capture, studied by spectroelectrochemistry | Reversible electrochemical capture of CO2 is demonstrated; faradaic currents associated with the quinone/CO2 reaction and in situ spectroscopic changes are reported (capacities and energies detailed in the paper) | First explicit demonstration of a redox-active MOF-based adsorbent for electroswing; the MOF acts as a porous scaffold and stabilizes the redox host | [94] |

| Zn(NDC) (DPMBI) and its reduced forms | Zn(II) node; redox-active benzenenotetracarboxidiimide ligand (DPMBI) | Controlled chemical/electrochemical reduction (Na+ introduction) of the framework; static CO2 adsorption measurements | Increased CO2 capacity and increased reduction degree up to a certain limit; also improved CO2/N2 selectivity compared to the neutral MOF | Qₛₜ | [95] |

| Ni2(dobdc) and functionalized derivatives (e.g., pip-Ni2 (dobdc)) | Ni(II) node; dobdc ligand with open sites and grafted amines | Adsorption cells where oxidation/reduction in the framework (or ligands) modulates CO2 affinity; primarily studied by adsorption + T/P stimulation and redox | Higher CO2/N2 selectivity and even higher after functionalization; changes in affinity have been explored by adjusting the metal’s redox state and the density of basic sites | Qst | [96] |

| Various redox-active MOFs (TTF, NDI, etc.) with CO2 response | Frameworks with tetrathiafulvalene (TTF), naphthalenediimide (NDI), or other π-redox systems ligands | SURMOF-type thin films and single crystals; spectroelectrochemical studies under CO2 atmospheres | Changes in UV-Vis-NIR spectra and adsorption capacity upon switching between redox states; in some cases, an increase in Qst and CO2 adsorbed charge | These studies demonstrate how redox ligands on MOFs can serve as a platform for gas electrosorption, although they are not always quantified as complete ECC cells. | [97] |

| Cu- and Ni-MOFs functionalized for CO2 capture/activation | Different nodes (Cu, Ni, Co) and ligands with basic/redox sites | MOF or MOF-derivative electrodes in electrochemical cell configurations (sometimes coupled to CO2 reduction) | CO2 adsorbed onto the MOF prior to reduction; some studies report enhanced capture capabilities under polarization and correlation with electrocatalytic activity | Bridge examples between capture and conversion; useful for your integrated capture+reduction section | [98] |

| MOF | Main Redox Unit | Characteristic | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKUST-1 (Cu) | Cu2+/Cu+ at carboxylate nodes | Lewis affinity modulation with CO2 | [106] |

| Fe-carboxylates | Fe3+/Fe2+ | Redox states of more than one redox state; strong interaction with CO2 | [63] |

| Cu3(HHTP)2 | π-conjugated ligands (HHTP) | Intrinsic conductivity; reversible 2D MOF pores | [15] |

| TTF-MOFs | Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF/TTF+•) | Reversible oxidation; electron density control | [107] |

| Viologen-MOFs | Viologeno (dication/radical catión) | Selective adsorption by modulated polarizability | [67,108] |

| Ferrocene-MOFs | Fe2+/Fe3+ in ligand | Stable redox signal; switchable selectivity | [68,69] |

| Parameter | Description/Importance | Indicative Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGads (kJ mol−1) | Free energy of adsorption under applied potential | −20 to −40 kJ mol−1 CO2 for selectivity without irreversibility | [3,99] |

| Energy efficiency | Electrical energy consumed per mole of captured CO2 | <100 kJ mol−1 CO2 | [38,49] |

| Adsorption kinetics (t90) | Time to reach 90% capacity | <60 s under applied potential | [34] |

| Cyclical stability | Number of adsorption/desorption cycles without significant loss | ≥104 cycles | [34] |

| Specific cost | Estimated cost per ton of captured CO2 | <50 USD/ton CO2 | [100] |

| Volumetric capture density | Normalized capacity per electrode volume | >2 mmol cm−3 | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Castillo, C.; Suazo-Hernández, J.; Espinoza-González, R.; Garcia, G. Smart Materials for Carbon Neutrality: Redox-Active MOFs for Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Electrochemical Methods. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121134

Castro-Castillo C, Suazo-Hernández J, Espinoza-González R, Garcia G. Smart Materials for Carbon Neutrality: Redox-Active MOFs for Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Electrochemical Methods. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121134

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Castillo, Carmen, Jonathan Suazo-Hernández, Rodrigo Espinoza-González, and Gonzalo Garcia. 2025. "Smart Materials for Carbon Neutrality: Redox-Active MOFs for Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Electrochemical Methods" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121134

APA StyleCastro-Castillo, C., Suazo-Hernández, J., Espinoza-González, R., & Garcia, G. (2025). Smart Materials for Carbon Neutrality: Redox-Active MOFs for Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Electrochemical Methods. Catalysts, 15(12), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121134