Abstract

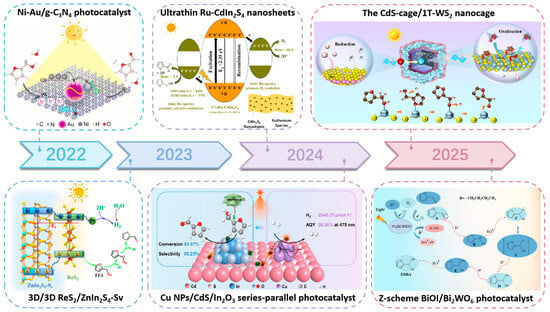

The photocatalytic conversion of biomass-derived furfural (FUR) represents a promising pathway for producing value-added chemicals and fuels in the context of sustainable energy and chemical synthesis. In this case, performance optimization and design of both traditional and novel catalysts are urgently demanded, aiming to provide theoretical guidance and technical support for efficient and selective photocatalytic conversion. This review comprehensively summarizes recent advances in the photocatalytic conversion of FUR into a range of valuable products, mainly including hydrogenation and oxidation, as well as coupling reactions. Different reaction pathways and catalytic methods are introduced, with emphasis on the performance, advantages, and disadvantages of different catalyst systems. We also outline current challenges and perspectives in this field, as well as directions to inspire further innovation in solar-driven biomass conversion toward a more sustainable chemical industry.

1. Introduction

Biomass stands as one of the most abundant renewable resources on earth, which shows considerable potential for replacing fossil resources in the production of high-value-added chemicals and green energy [1,2,3]. Hemicellulose is a major component of lignocellulose and one kind of abundant polysaccharide in nature. It can serve as the predominant renewable organic resource and be catalytically converted into liquid fuels, pharmaceuticals, and chemical intermediates. To make full use of the natural resource, efficient conversion of this biomass component is gaining considerable attention for producing energy, fuels, and chemicals [4,5,6].

FUR is one of the primary chemicals derived from the pentose sugars in lignocellulosic biomass, which can only be produced exclusively from renewable resources, with no known petroleum-based synthesis route [7,8,9]. Designated by the U.S. Department of Energy as a high-value biomass-derived platform chemical, FUR has attracted significant research interest due to its considerable economic prospects [10,11]. Its widespread application in petroleum refining, plastics, and pharmaceuticals stems from its high reactivity, imparted by the coexistence of a furan ring and an aldehyde group. This allows FUR to undergo diverse reactions, including reduction, oxidation, amination, alkylation, acetalization, acylation, etc. [12,13], facilitating the synthesis of nearly 100 distinct derivatives. Such diverse reactivity underscores the exceptional potential of FUR as a cornerstone of modern biorefining.

Photocatalytic conversion of FUR offers an attractive alternative to conventional thermocatalytic methods [14]. By employing light as an energy source, this approach activates reactions that are challenging or non-feasible under dark conditions [15], correspondingly lowering the thermal energy demand. Such characteristics align well with economic and environmental objectives, positioning photocatalysis as an energy-efficient and eco-friendly strategy for biomass valorization [16,17,18,19]. In photocatalytic processes, redox reactions are driven by photogenerated electron (e−)–hole (h+) pairs. The underlying mechanism is initiated by the absorption of photons with energies matching or exceeding the semiconductor’s bandgap, prompting e− excitation from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), and resulting in h+ generation in the VB. The e− in the CB participates in reduction reactions, while oxidation reactions are driven by the photo-induced h+ in the VB [20,21,22]. This strategy also facilitates the activation and transformation of targeted chemical bonds under exceptionally mild reaction conditions by utilizing photo-induced charge carriers or reactive species.

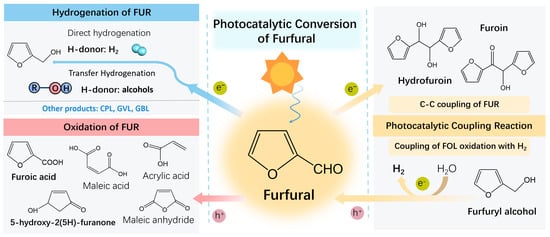

Via photocatalytic hydrogenation, FUR can be transformed into products such as furfuryl alcohol (FOL, through direct and transfer hydrogenation), γ-butyrolactone (GBL), γ-valerolactone (GVL), and cyclopentanol (CPL). Through photocatalytic oxidation, it can be converted to furoic acid (FA), 5-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone (5-HFO), maleic acid (MA), maleic anhydride (MAN), and acrylic acid (AA), among others. Furthermore, coupling reactions can also occur. FOL can be oxidized to FUR with hydrogen (H2) evolution, and FUR can undergo C–C coupling during hydrogenation to form coupling products, namely hydrofuroin (HFO) and furoin (FO) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Photocatalytic conversion of FUR to value–added chemicals.

Several excellent reviews have previously explored the catalytic conversion of FUR and its derivatives, mostly focusing on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural [12,14,20], with little research dedicated to FUR. This review presents a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the photocatalytic conversion of FUR into various high-value products. Various photocatalytic systems in this field are discussed in detail, with a focus on strategies for enhancing light absorption, charge separation, and catalytic selectivity. Despite significant progress, challenges remain in catalyst stability, scalability, and mechanistic understanding. This review also outlines future research directions, including the design of efficient, stable, and scalable photocatalysts, the elucidation of reaction mechanisms via in situ/operando techniques, and the method of enhancing product selectivity. The insights provided herein aim to inspire further innovation in the solar-driven valorization of biomass towards a sustainable chemical industry.

2. Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of FUR

FOL, the main derivative of FUR, accounts for about 65% of its downstream products. It serves as a pivotal intermediate for numerous valuable chemicals. This section reviews advancements in the photocatalytic hydrogenation of FUR to FOL and other products, categorizing them by hydrogenation methods and catalyst types, whose relevant performance metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Photocatalytic reduction in FUR to FOL via different hydrogenation methods.

2.1. Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of FUR to FOL

2.1.1. Direct Hydrogenation to FOL

Direct hydrogenation refers to the process catalyzed by a photocatalyst in which H2 acts as the direct hydrogen source to produce FOL. During this, the aldehyde group (–CHO) in FUR is reduced to a hydroxymethyl group (–CH2OH). In this process, direct hydrogenation offers several notable advantages:

- -

- High reaction activity: This method leverages H2 as a potent reducing agent, and the efficient activation and delivery of hydrogen atoms could promote the selective hydrogenation of the aldehyde group and result in elevated conversion levels and rapid kinetics of the reaction.

- -

- Mild reaction conditions: The reaction is typically performed at ambient temperature or under mild heating, offering a significant advantage in terms of energy efficiency.

- -

- Superior product selectivity: Employing catalysts with high photocatalytic responsiveness and effective hydrogen adsorption/activation capabilities allows for exceptional selectivity of the main products, thereby suppressing undesirable side reactions.

- -

- Established reaction mechanism: The mechanistic understanding is relatively well-established, providing a solid theoretical foundation for further catalyst design and kinetic analysis.

To implement this process efficiently, various advanced photocatalytic systems have been investigated. For instance, a sustainable photocatalytic procedure for the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL was reported by wang et al. [23]. The process was facilitated by a catalyst with stable Cu NPs encapsulated in a few-layered carbon, which was prepared via the pyrolysis of HKUST-1 metal–organic framework. It achieves outstanding catalytic efficiency under visible light and moderately elevated temperatures. The Cu nanoparticles can harvest visible light and generate photoexcited electrons due to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect. These electrons subsequently transfer energy to molecules absorbed on the Cu NP surface, thereby facilitating H2 dissociation and driving FUR hydrogenation.

During the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL, bimetallic oxides can provide adjustable properties by forming a heterojunction, resulting in better performance. Zhang et al. [24] developed a catalyst with Pt nanoparticles (Pt NPs) supported on a NiO-In2O3 bimetallic oxide. This is due to the excellent band structure and highly efficient internal charge transfer of 99.9% under an LED light at temperatures of 273 K and 293 K. The combination of •H dissociated from H2 and oxygen vacancy works synergistically to adsorb, activate, and convert C=O to the C–O group.

These studies highlight the importance of catalyst design and photocatalytic mechanism in enhancing the selectivity and efficiency of the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL. Both the Cu-based and Pt-based systems demonstrate promising performance under visible light-driven conditions. Although significant efforts have been recently devoted to the production of “green hydrogen” through water splitting or biomass gasification, commercial hydrogen is still predominantly sourced from non-renewable fossil fuels [35,36]. In addition, its reliance on H2 gas presents challenges in sourcing, storage, and safety, prompting the exploration of alternative hydrogenation strategies.

2.1.2. Transfer Hydrogenation to FOL

Transfer hydrogenation, discovered by Knoevenagel in the early 20th century, has recently gained increasing popularity due to its potential application in the valorization of biomass. There are several key benefits to adopting indirect hydrogen sources for transfer hydrogenation reactions, including employing milder reaction conditions. This approach simultaneously enhances process safety within biorefineries and lowers infrastructure costs by eliminating the need to handle explosive gaseous H2.

Therefore, the reduction in FUR can be achieved via transfer hydrogenation, where liquid organic molecules serve as efficient, green, and benign hydrogen donors (H-donors). Among the various alternative H-donors, short-chain aliphatic alcohols are the most extensively studied [37]. This preference stems from their direct availability from biomass, low cost, ease of handling, and the formation of oxidized products that can be readily recycled or reused. To fully leverage the potential of these sustainable H-donors in photocatalytic processes, the selection of a suitable and efficient catalyst is crucial. The most common materials in this field are TiO2-based catalysts, metal sulfide catalysts, and other composite catalysts.

TiO2-Based Catalysts

After its breakthrough in electrochemical water photolysis, the metal-oxide semiconductor TiO2 has been highly valued as the most reliable photocatalyst with cost-effectiveness, chemical inertness, exceptional photoactivity, and stability [38]. The core mechanism of TiO2-based catalysts lies in the combination of their surface properties and UV response. As a wide band-gap semiconductor, TiO2 generates electron–hole pairs under UV excitation, and its holes have strong oxidation ability, which can activate alcohol hydrogen donors and promote the accumulation of H+ and e− on the catalyst surface. TiO2 can often easily contribute to the direct degradation of organic compounds owing to its potent oxidizability [14]. In this context, TiO2 has been widely investigated as a prototypical photocatalyst for transfer hydrogenation due to its robust oxidizing power and ability to activate various H-donors.

Upon illumination, TiO2 can form a photo-induced reduced state (TiO2/e−) and remain reactive within an inert atmosphere. Qiao et al. [26] achieved selective hydrogenation of FUR to FOL over amorphous TiO2 via a cascade strategy. When employing alcohol as an H-donor, H+/e− species could accumulate on the amorphous TiO2 surface under UV light and an inert atmosphere. The hydrogenation through proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) is initiated in the “dark” upon introduction of FUR into the solution. In addition, this photocatalytic process enables the dual upgrading of both FUR and alcohol. Nakanishi et al. [25] took out the photocatalytic hydrogenation of FUR in 2-pentanol suspensions of TiO2 under metal-free and hydrogen-free conditions, and they revealed that this was a highly chemoselective process. Near-quantitative FOL production is accomplished via the selective reduction of the carbonyl group in FUR to a hydroxymethyl group. 2-pentanol is simultaneously oxidized to 2-pentanone at high stoichiometry.

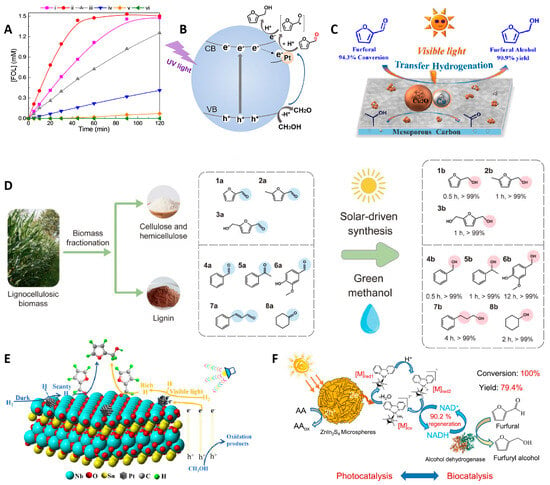

The photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2 can be further developed by regulating the physicochemical properties, loading active metals, and other modification methods. Lopes et al. [27] reported a series of TiO2 catalysts prepared by calcination at different temperatures. The TiO2 calcined at 600 °C exhibited the optimal catalytic activity under UV-LED with ethanol as the H-donor. This is due to its dominant anatase phase, high-density oxygen vacancy defects, and the anatase/rutile heterojunction structure. The concentration distribution of FOL on TiO2 calcined at different temperatures is shown in Figure 2A. The key active sites were oxygen vacancies, which could significantly enhance catalytic efficiency by inhibiting photogenerated carrier recombination and promoting intermediate adsorption. Meanwhile, precise control of phase transition temperature balances defect density and interface charge separation.

Figure 2.

(A) The concentration distribution of FOL after 2 h on TiO2 calcined at different temperatures. (i) TiO2–500, (ii) TiO2–600, (iii) TiO2–700, (iv) TiO2–800, (v) TiO2–900, and (vi) TiO2–1000 [27]; (B) the mechanism diagram of photocatalytic FUR hydrogenation to FOL over Pt/P25 (* represents free radicals) [29]; (C) the schematic of photocatalytic FUR hydrogenation to FOL over MC–supported Cu-based catalysts [34]; (D) photocatalytic hydrogenation of various biomass-derived platform molecules to renewable chemicals over CuSAs–TiO2 catalyst [30]; (E) the reaction pathway for selective hydrogenation of FUR to FOL over Pt/SN (blue represents the aldehyde group, and pink represents the hydroxyl group) [32]; (F) photocatalytic NADH regeneration and photo–enzyme coupling catalytic conversion of FUR to FOL [31].

Research has proven that the photocatalytic selective hydrogenation performance of TiO2 can be enhanced through surface modification with metal or non-metal. For instance, the combination of TiO2 with graphene facilitates the transfer of photoexcited electrons from the CB to graphene, consequently enhancing charge separation efficiency. Mekasuwandumrong et al. [28] found that the graphene-modified TiO2 photocatalytic system significantly enhances the activity of the selective hydrogenation of FUR to FOL. The formation of chemical bonds between graphene and TiO2 can prolong the e−–h+ recombination process, thereby improving charge separation efficiency. In the work of Lv et al. [29], FOL selectivity was significantly boosted by the use of a TiO2 catalyst with an ultra-low metal loading and the presence of a small amount of water. The schematic diagram of the reaction occurring on the catalyst is shown in Figure 2B. The supported metal enhances oxygen vacancy concentration on the TiO2 surface, leading to improved UV harvesting and FUR activation. This effect could be complemented by the addition of a small amount of H2O, which mediates intermediate desorption on the catalyst surface and the interfacial diffusion, thereby minimizing yields of undesired coupling products. Chen’s work [30] designed a CuSAs-TiO2 photocatalyst with a four-coordinated Cu1-O4 structure supported by ultra-thin TiO2 nanosheets, using methanol as an H-donor for hydrogenation upgrading of biomass-derived FUR (Figure 2D). The catalyst demonstrates exceptional performance, achieving a FOL production rate of 34 mol h−1 mol Cu−1 in a photochemical flow reactor and maintaining over 99% selectivity. This remarkable efficiency stems from the dynamic evolution of Cu active sites, enabling synchronous utilization of both photogenerated e− and h+ through tandem reaction pathways.

Substantial enhancement of TiO2 catalysts for selective hydrogenation can be realized through multiple strategies: precise structural control, surface defect engineering, heterojunction formation, and integration with functional materials. These approaches not only advance the fundamental understanding of photocatalytic mechanisms but also establish crucial theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for designing efficient and environmentally friendly catalysts for biomass conversion. Consequently, significant research efforts have focused on augmenting both product selectivity and visible light responsiveness in TiO2-based photocatalytic systems.

Metal Sulfide Catalysts

Although TiO2 has demonstrated impressive catalytic performance, its practical application is constrained by a wide bandgap that restricts activity primarily to the UV spectrum. This limitation would stimulate the exploration of visible-light-active alternatives. Compared with TiO2, metal sulfides have stronger carrier migration ability, and some metal sulfides have narrower bandgaps, so they can respond to photon energy in the visible light region. Zinc indium sulfide (ZnIn2S4) has emerged as particularly promising due to its suitable bandgap, non-toxicity, superior physicochemical stability, straightforward synthesis, and outstanding photocatalytic activity. Under visible light excitation, ZnIn2S4 can generate electron–hole pairs, and its unique hierarchical structure facilitates efficient separation and migration of charges. Employing ZnIn2S4-based photocatalysts in conjunction with biomass-derived feedstocks has spurred significant growth in the green synthesis of value-added oxygenated chemicals [39]. Zhao et al. [31] developed an innovative photo-enzyme coupled system, integrating the alcohol dehydrogenase with ZnIn2S4 to facilitate a reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotid (NADH) regeneration. The hierarchical ZnIn2S4 microspheres achieve excellent h+ and efficient charge separation under visible light, resulting in a NADH regeneration yield of 90.2 ± 3.28%. The coupled catalytic process yielded 79.4 ± 1.95% of FOL under optimal reaction settings (Figure 2F).

Other Catalysts

The development of composite catalysts represents a strategic approach to overcoming the limitations of single-component systems by harnessing complementary material properties. By ingeniously combining multiple materials, these composites could create synergistic effects that significantly improve light absorption, charge separation efficiency, and surface reaction kinetics. Shi et al. [32,33] studied surface functionalized Pt/SnNb2O6 nanosheets (Pt/SN) and ultra-thin Pt/NiMg-MOF-74 nanosheets (MNM) for visible light-driven FUR hydrogenation to FOL. Ultra-thin SN, with a thickness of merely 4.1 nm, possesses abundant Lewis acid sites (Nb5+) on the surface. These sites selectively chemisorb and activate FUR molecules through Nb…O=C coordination. Concurrently, Pt nanoparticles accumulate photo-generated electrons, significantly enhancing the formation of active hydrogen species, which drive the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL. The synergistic interaction between SN and Pt nanoparticles substantially boosts the overall photocatalytic hydrogenation efficiency. The possible mechanism is illustrated in Figure 2E. The synergistic effect of surface-optimized NiII sites can also successfully achieve efficient and precise hydrogenation from FUR to FOL. The conversion of FUR and the selectivity of FOL both reach 99.9%. Given the affordability, abundance, and environmental compatibility of Cu and its oxides, transfer hydrogenation of FUR to FOL over Cu-based catalysts presents a promising and worthwhile research strategy. Zhang et al. [34] successfully developed a Cu/Cu2O composite supported on graphitized mesoporous carbon. The outstanding activity in visible-light-driven transfer hydrogenation of FUR to FOL is attributed to synergistic interactions between Cu2O and plasmonic metallic Cu (Figure 2C).

The structural diversity and tunable optoelectronic properties of polymeric photocatalysts make metal-free photocatalytic hydrogenation an attractive, sustainable technology. Hu et al. [40] designed a thiophene-incorporated covalent triazine polymer resulting in a unique D-A (the electron donor and acceptor units) structure that promotes the p-electron delocalization and enhances the charge separation. This metal-free system achieves the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL at a rate of approximately 0.5 mmol g−1h−1 under visible light irradiation.

As summarized in Table 1, the highest yield of FOL is achieved when using H2 as the H-donor and Pt as the active metal catalyst. This high performance is attributed to the direct hydrogenation pathway enabled by H2, and the strong synergistic effect between Pt and its support. In this system, Pt efficiently dissociates H2 into active hydrogen species, while the support facilitates FUR adsorption and activation. In contrast, using alcohols as H-donors offers reduced cost and enhanced safety. Notably, TiO2-based catalysts combined with such H-donors lead to high FOL yields. Among the reported studies on the photocatalytic hydrogenation of FUR to FOL, primary alcohols represent the most commonly employed H-donors. Compared to primary alcohols, secondary alcohols have two significant characteristics: (i) higher reduction potential, and (ii) a stronger stabilizing effect of secondary carbocations formed during hydride transfer. Secondary alcohols, especially 2-propanol and 2-butanol, are typically the most effective H-donors [41]. Therefore, in future research on transfer hydrogenation, secondary alcohols can be favored as H-donors.

Nowadays, the production of biomass-derived FUR is carried out via mineral acid-catalyzed conversion under both batch and continuous flow conditions. Formic acid has also been reported as a catalyst for the production of FUR from xylose [42]. Namhaed et al. [43] implemented a strategy wherein formic acid replaced traditional inorganic acids to reduce equipment damage, and they employed green supercritical CO2 as the extraction medium concurrently. This method enhanced FUR yield and effectively prevented its degradation. Du et al. [44] and Xu et al. [45] carried out the hydrogenation of FUR to FOL using formic acid as an H-donor through thermal catalysis. However, similar reactions in the field of photocatalysis remain imperative to be explored.

2.2. Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of FUR to Other Products

While the photocatalytic hydrogenation of FUR to FOL has been extensively explored, the selective synthesis of further reduced products represents a growing and valuable research direction. Advancing along the hydrogenation pathway beyond FOL can obtain a different suite of high-value chemicals with distinct applications. FOL is a key intermediate in this deeper reduction pathway. For instance, under suitable catalytic conditions, FUR can be reduced to FOL and then undergo ring-rearrangement and further hydrogenation to yield valuable products, CPL.

Products including GVL and CPL are recognized as promising green solvents, renewable fuel components, and key intermediates for polymer and pharmaceutical synthesis. Conventional production methods, however, typically involve energy-intensive processes and costly noble metal catalysts. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) represents a class of non-metallic organic semiconductors prized for their distinct attributes, including well-defined structure, tunable band structure, excellent physicochemical properties, non-toxicity, and economic viability [46]. Chauhan et al. [47] developed a composite photocatalyst (Ru@CP/CN) incorporating Ru-decorated g-C3N4 (CN) and phytic acid-derived carbon (CP). This composite demonstrates remarkable performance in the simultaneous conversion of levulinic acid (LA) to GVL and FUR to CPL under mild conditions, coupled with water splitting. The system delivered exceptional selectivity, 99% for GVL within 6 h and 86% for CPL within 9 h, which is attributed to enhanced electron transfer from the CN to Ru active sites.

Another significant product, GBL, serves both as a sustainable alternative to hazardous chlorinated solvents and a bio-derived monomer for synthesizing biodegradable polyesters [48]. Ghalta et al. [49] reported a photocatalytic valorization method from FUR to THFA and subsequently to GBL for the production of other valuable renewable chemicals from biomass platform chemicals. Using a 3 wt% Pd NP modified g-C3N4 catalyst under ambient temperature and 2 bar H2, the system achieved nearly complete FUR conversion and total selectivity toward THFA within 5.5 h under white LED irradiation. After the subsequent oxidation at 1 bar O2 for 8 h, THFA is converted to GBL with a selectivity close to 100%. Decoration of Pd NPs significantly enhances photoactivity and photoelectrochemical performance by hosting electrons, which prolongs the lifetime of charge carriers and promotes their separation. The catalyst also demonstrates excellent recyclability over five cycles and maintains high photostability.

This section summarizes advances in photocatalytic FUR hydrogenation, highlighting its strengths in achieving efficient and selective conversion under mild, solar-driven conditions, particularly through the transfer hydrogenation method. However, key limitations persist, including the poor visible-light response of benchmark catalysts, insufficient mechanistic understanding, and a narrow scope of H-donors, as well as the significant gap between lab-scale research and industrial application. Therefore, future efforts must prioritize developing stable, broad-spectrum-responsive catalysts and gaining deeper mechanistic insights.

3. Photocatalytic Oxidation of FUR

Photocatalytic oxidation has emerged as a promising strategy in the value-added transformation of biomass platform molecules. The oxidation products of FUR include FA, 5-HFO, MA, MAN, AA, and so on. These compounds have wide applications in pharmaceuticals, polymers, and biofuels.

3.1. Photocatalytic Oxidation of FUR to FA

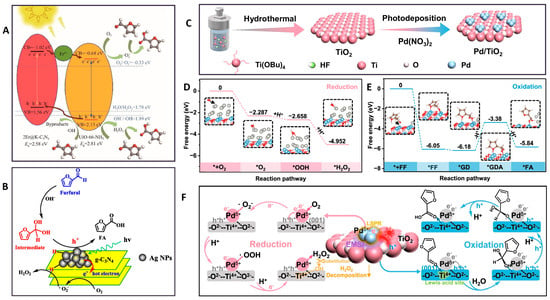

FA represents a primary and valuable oxidation product of FUR. Under the action of an oxidizing agent or photogenerated holes, the aldehyde group of FUR is oxidized to a carboxylic acid group, forming FA, while the furan ring remains intact. A notable example is the work by Wang et al. [50], who demonstrated that the Er@K-C3N4/UiO-66-NH2 catalyst exhibits exceptional efficiency in the photocatalytic oxidation of FUR to FA. Upon the optimized reaction conditions, the conversion rate of FUR reaches 89.3%, with a corresponding yield of FA at 79.8%. The primary reactive oxygen species is identified as •O2−. The incorporation of Er and K into the catalyst enhances the photogenerated carriers’ transfer rate, hence increasing the separation efficiency of photogenerated electron–hole pairs. The reaction pathway is illustrated in Figure 3A.

Another effective approach involves depositing noble metal nanoparticles to augment photocatalytic behavior. Li et al. [51] fabricated the Ag/g-C3N4 catalysts featuring small Ag NPs. The optimized Ag-CN(N2 + H2) sample exhibits superior photocatalytic activity in the oxidation of FUR compared to pristine g-C3N4. The deposited Ag NPs improve charge separation and migration, reduce electrochemical impedance, and accelerate interfacial electron transfer. This not only broadens the absorption range of sunlight but also forms “hot electrons” that activate O2 to generate the •O2− species, which can react with H-metal species to produce H2O2 or H2O, thereby driving the oxidation of FUR (Figure 3B).

A central challenge in photocatalysis lies in the simultaneous utilization of both photogenerated electrons and holes for dual value-added chemicals. In recent years, a large number of studies have often employed only one type of charge carrier for a single redox transformation, leaving the complementary redox potential under-exploited. Addressing this limitation, Liu et al. [52] showed that Pd/TiO2 (the schematic illustration for the synthesis is shown in Figure 3C), featuring electronic metal–support interaction (EMSI) enables simultaneous photocatalytic H2O2 production and selective oxidation of FUR to FA. The free energy diagrams and reaction pathway are shown in Figure 3D–F. The EMSI modulates the electronic structure of Pd, forming Pdδ+ active sites with an upshifted d-band center, which enhances O2 adsorption and boosts H2O2 generation. Concurrently, photogenerated holes from TiO2 could drive FUR oxidation to FA via an aldehyde–water shift pathway by sequential breaking of O-H and C-H bonds. The optimal H2O2 and FA evolution rates of Pd/TiO2 achieve 3672.31 and 4529.08 μM h−1, respectively, with an FUR conversion of 92.66% and FA selectivity of 97.82%.

Metal-doped or metal-modified catalysts exhibit enhanced charge separation and catalytic efficiency. The metallic components enhance the formation of reactive oxygen species and improve the selective oxidation of FUR. To advance the field, subsequent studies ought to concentrate on refining interfacial charge-transfer dynamics, engineering versatile photocatalysts, and transitioning these systems toward industrial scalability.

Meanwhile, efforts on elucidating the cooperative redox mechanisms and the function of active centers at the metal–support interface should be taken to guide the rational development of advanced photocatalytic materials.

Figure 3.

(A) The reaction pathway of FUR photocatalytic oxidation over 2Er@K–C3N4/UiO–66–NH2 [50]; (B) the reaction pathway for the oxidation of FUR to FA under visible light over Ag/g–C3N4 [51]; (C) the schematic illustration for the synthesis of Pd/TiO2: it was synthesized by preparing TiO2 nanocrystals via a hydrothermal method, followed by loading Pd through a photo deposition method [52]; (D) the free energy diagrams of O2 reduction steps over 0.5% Pd/TiO2 [52]; (E) the free energy diagrams of FUR oxidation steps over 0.5% Pd/TiO2 (* represents free radicals) [52]; (F) the reaction pathway of 0.5% Pd/TiO2 for photocatalytic H2O2 evolution coupled with the oxidation of FUR to FA [52].

3.2. Photocatalytic Oxidation of FUR to 5-HFO

The formation of 5-HFO involves the oxidation and ring opening of the furan ring. The oxidation of FUR to 5-HFO was first described by Schenck [53]. They use dye sensitizers such as Rose Bengal and methylene blue to absorb sunlight and produce singlet oxygen. Using a parabolic trough with line focusing can converge sunlight and improve photon efficiency. Using Metal-TS-1 zeolite catalysts for photocatalytic FUR oxidation at ambient temperature and pressure, Liang et al. [54] achieved the selective production of C4 carboxylic acid derivatives, including maleic acid (MA), malic acid, and 5-HFO. Their work highlights the critical influence of the catalyst’s structure–property relationship on product distribution. The confined pore sizes limit further conversion of MA to malic acid, and the moderate acidity promotes malic acid yield. Meanwhile, the MA/malic acid selectivity could be directed by the valence band position.

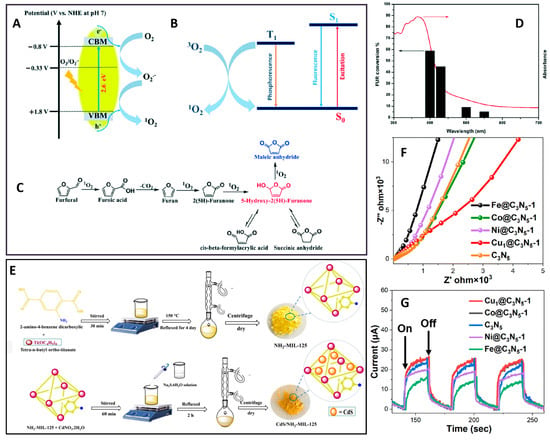

A heterogeneous photocatalytic system for the oxidation of FUR to maleic anhydride (MAN) and 5-HFO was pioneered by Chauhan et al. [55] using molecular oxygen and mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (SGCN). The activity of SGCN shows a strong correlation with its optical absorption (Figure 4D). Singlet oxygen and holes are identified as the crucial species in the process. The singlet oxygen is generated through h+ on the surface of SGCN and through triplet energy transfer, as shown in Figure 4A,B. The reasonable mechanism pathway of FUR photocatalytic oxidation is shown in Figure 4C.

Metal–organic frameworks are a new type of crystalline material with high porosity, more than 90% void volume, and a very high specific surface area. Especially, NH2-MIL-125, a MOF containing Ti as a metal node and carboxylate as an organic linker, has significant structural stability. Saki et al. [56] established the selective oxidation of FUR to MA and 5-HFO over a heterogeneous CdS (2.5%)/NH2-MIL-125 catalyst (synthetic process is shown in Figure 4E). The photocatalyst demonstrates outstanding performance, providing over 90% FUR conversion with selectivity of 52% for 5-HFO and 90% for MA under diverse conditions. The enhanced photocatalytic activity of the CdS (2.5%)/NH2-MIL-125 composite can be attributed to the synergistic interactions between the NH2-MIL-125 surface and CdS active sites. Moving beyond inorganic materials, Seo et al. [57] designed and evaluated Pd-contained porphyrin-cored amphiphilic star block copolymers for FUR photooxidation. The amphiphilic structure leads to improved efficiency because its hydrophobic interior could actively adsorb hydrophobic reagents. This approach provides a fundamental design principle for developing polymeric catalysts targeting the photooxidation of hydrophobic compounds.

Figure 4.

(A) The formation of singlet oxygen on the SGCN surface via h+ [55]; (B) the formation of singlet oxygen via triplet state energy transfer [55]; (C) the reaction pathway of FUR photooxidation [55]; (D) the real action spectrum of FUR oxidation at different wavelengths [55]; (E) the synthetic process for CdS/NH2-MIL-125 nanocomposites using the solvothermal method [56]; (F) electrochemical impedance spectra of different catalysts: Cu1@C3N5-1 has the lowest resistance value [58]; (G) transient photocurrent density response of different catalysts: Cu1@C3N5-1 has the highest photocurrent intensity [58].

The photocatalytic oxidation of FUR to valuable products such as 5-HFO has been extensively explored. Early work by Schenck employed dye sensitizers and solar light to generate singlet oxygen, while recent studies have focused on designing advanced heterogeneous catalysts. These systems are operated under mild conditions utilizing molecular oxygen and light, achieving high conversion and selectivity, which could be influenced by catalyst properties such as pore structure, acidity, band energy, and surface hydrophobicity. Critical reaction mechanisms often involve singlet oxygen and hole-mediated pathways, highlighting the role of catalyst design in steering product distribution toward targeted C4 derivatives.

3.3. Photocatalytic Oxidation of FUR to MA, MAN, and AA

Recent advances have highlighted the effectiveness of tailored catalyst design and novel synthetic strategies in steering reaction pathways toward targeted products. The following studies are focused on this direction, demonstrating how innovative approaches can achieve high conversion and selectivity under remarkably mild conditions. Ebrahimian et al. [59] repurposed expired metformin, a kind of pharmaceutical waste, as an economical nitrogen-doping precursor. This strategy significantly elevated the N/C atomic ratio in the resulting materials, yielding catalysts with optimized characteristics including expanded surface area, reduced bandgap, and suppressed e−–h+ recombination. The catalyst containing 1% metformin demonstrates outstanding performance in MA production using H2O2 as the oxidant under ambient conditions.

Nitrogen-rich graphitic carbon nitride material exhibits narrowed bandgaps compared to conventional graphitic carbon nitrides, which is attributed to its extended conjugated network of N-rich structures and p-conjugated system of heptazine groups. Furthermore, metal doping can form a π-conjugated system to shorten the bandgap by multiplying the N coordination. Li et al. [58] systematically evaluated the electrochemical impedance spectra (Figure 4F) and transient photocurrent density response (Figure 4G) of different catalysts. The Cu single-atom-anchored nitrogen-rich graphitic carbon nitride achieved an exceptional MAN yield of up to 98% from FUR under visible light irradiation at 40 °C and atmospheric oxygen pressure. Mechanistic studies revealed that O2 activation constitutes the rate-determining step, with 1O2 and •O2− playing a synergetic oxidation role in the oxidation process. The incorporated copper species facilitated oxygen activation while enhancing the kinetics of exciton dissociation and electron transfer. The incorporated Cu species facilitate oxygen activation while enhancing exciton effects and electron transfer. Hermens et al. [60] established an integrated synthetic route converting FUR to monomers MAN and AA through sequential photo-oxygenation, aerobic oxidation, and ethenolysis reactions. As a result, this method combines multiple important features of green chemistry, such as the application of catalytic reactions, minimization of waste generation, high yield, and excellent atomic efficiency.

Photocatalytic oxidation technology provides an efficient, green, and sustainable pathway for the high-value conversion of biomass platform molecules. This technology is expected to play a more significant role in the production of bio-based chemicals, pharmaceutical intermediates, and biofuels. The following research should focus on continuous optimization of catalyst structures, enhancement of reaction selectivity and activity, and exploration of novel dopants and reaction conditions. In addition, researchers should place greater emphasis on a deeper understanding of the reaction mechanisms, the sustainable design of catalysts, and the feasibility analysis for industrial applications, in order to further advance the development of this field.

4. Photocatalytic Coupling Reaction

4.1. Photocatalytic Coupling Oxidation of FOL with H2 Evolution

The utilization of solar energy to drive simultaneous photocatalytic valorization of biomass derivatives and H2 evolution represents a sustainable strategy to address global energy challenges [61]. This integrated approach employs photogenerated h+ for oxidizing furfuryl compounds while utilizing e− for proton reduction to H2 [14]. Substantial advancements in FOL oxidation coupled with H2 evolution under mild reaction conditions have been witnessed in recent years (Figure 5).

4.1.1. Metal-Loaded Catalysts

Nowadays, metal sulfide-based photocatalysts have demonstrated exceptional promise for visible-light-driven redox reactions. Han et al. [62] developed ultra-thin CdS nanosheets functionalized with Ni co-catalysts (Ni/CdS) that efficiently generate electron–hole pairs under visible light illumination. This system achieves concurrent FOL oxidation to FUR and H2 production in neutral aqueous media. Under alkaline conditions, the reaction pathway shifts toward nearly quantitative FA formation. The Ni/CdS architecture maintains remarkable catalytic activity and structural integrity across varying pH environments, enabling selective production of either aldehydes or acids through controlled reaction engineering. Combining a semiconductor with a co-catalyst, Yang et al. [63] constructed Ru-decorated Zn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods via photo deposition, achieving simultaneous production rates of H2 and FUR as 870 and 855 µmol h−1g−1, respectively. The enhanced performance originates from optimized charge carrier separation and transport driven by strong electronic coupling between Ru nanoparticles and the Zn0.5Cd0.5S semiconductor.

Figure 5.

The investigation into mechanism of coupling oxidation of FOL with H2 evolution [64,65,66,67,68,69].

The selective oxidation of FOL is significantly promoted by the preferential adsorption between Ru sites and the hydroxyl moiety. Cadmium indium sulfide (CdIn2S4) has recently emerged as a promising visible-light-responsive material due to its narrow bandgap (2.0–2.4 eV) and efficient light absorption [70,71]. Hamza et al. [66] fabricated ultra-thin CdIn2S4 nanosheets via solvothermal synthesis with in situ Ru deposition (Ru-CdIn2S4). The incorporation of Ru co-catalyst enhanced H2 evolution rates by up to 50-fold while improving FOL conversion efficiency and FUR selectivity, primarily through enhanced spatial charge separation. When designing catalysts, the creation of more interfaces will be helpful to promote the overall reaction efficiency. Liu et al. [72] discovered that amorphous Ru-RuOx hybrid structures exhibit exceptional h+ trapping capabilities compared to metallic Ru alone. The abundant atomic interfaces in this configuration enable ultra-fast h+ capture within 100 fs, followed by efficient electron transfer within 1.73 ps. This rapid charge dynamic establishes long-lived charge separation states, ultimately boosting H2 evolution to 4240 µmol h−1g−1. Beyond single-metal systems, bimetallic modifications offer additional performance benefits [65]. Ni-Au-modified g-C3N4 photocatalyst fabricated through a step-by-step photo deposition leverages complementary functions: g-C3N4 serves as the primary light-absorbing component, Au nanoparticles generate LSPR to broaden light absorption, and Ni species function as both e− traps and H2 evolution active sites. The synergistic interplay among these components displays an H2 production rate three times higher than Au/g-C3N4.

Metal-based catalysts have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in the photocatalytic oxidation of FOL coupled with hydrogen evolution. These studies collectively underscore the critical roles of metal co-catalysts in promoting charge separation and tailoring catalytic selectivity for integrated oxidation and hydrogenation reactions under light irradiation.

4.1.2. Heterojunction Catalysts

The rational design of heterojunction catalysts extends beyond achieving mere spatial charge separation; it fundamentally governs the subsequent surface reaction pathways and product distribution. The efficacy of these systems hinges on the precise management of charge carrier dynamics at the interface, which directly influences the formation and stability of key reaction intermediates. The built-in electric field, band alignment, and interfacial coupling collectively determine the flux and energy of photogenerated e− and h+ reaching active sites. This, in turn, dictates the activation of specific chemical bonds in the reactant. Consequently, a deeper mechanistic understanding of how specific heterojunction configurations steer these charge-mediated processes is paramount for advancing selective photocatalytic transformations. The following discussion analyzes various heterostructures with an emphasis on their interfacial charge transfer mechanisms and the resulting impact on intermediate evolution and product selectivity.

The construction of heterojunctions presents an innovative approach for developing bi-functional photocatalysts, where interface engineering plays a crucial role. Li et al. [73] precisely engineered a 2D/2D LaVO4/g-C3N4 (LaVO4/CN) heterostructure through self-assembly of square LaVO4 nanosheets on thin CN layers. This configuration created abundant 2D/2D interfacial contacts that optimized e− and h+ transport pathways. The resulting composite demonstrated exceptional photocatalytic performance, achieving hydrogen evolution at 287 µmol h−1g−1, FUR production at 950 µmol h−1g−1, and an apparent quantum efficiency of 22.16% at 400 nm. Defect engineering serves as another effective strategy for the modulation of electronic structure, substantially improving visible-light absorption and charge carrier dynamics. Hu et al. [67] developed a novel 3D/3D ReS2/ZnIn2S4-Sv heterojunction featuring a unique cellular layered structure with sulfur vacancies. This design attained H2 and FUR production rates of 1080 and 710 µmol h−1g−1, respectively. This is attributed to increased surface area by ReS2 and S vacancies, which accelerate charge separation and suppress carrier recombination. The core–shell configuration facilitates the establishment of intimate interfacial connectivity and an expanded contact area, effectively promoting the separation of photogenerated carriers and providing spatially segregated active sites for redox reactions. Yang et al. [74] engineered a Mo2C@ZnIn2S4 Schottky heterojunction with a hierarchical core–shell architecture. This design leverages simultaneous consumption of photoexcited e− and h+ to achieve synergistic catalysis. The remarkable H2 and FUR production performance stems from the concerted action between the unique core–shell structure and the Mo2C co-catalyst. As a result, the tightly bonded heterointerface, high surface area, numerous charge transfer channels, and separate oxidation/reduction sites could significantly advance spatial charge separation and migration dynamics.

The step-scheme (S-scheme) heterojunctions represent an advanced design. The built-in electric field and band bending provide photogenerated electrons and holes with superior redox capabilities, exhibiting great application potential in cooperatively realizing photocatalytic overall redox reactions. Sun et al. [75] fabricated an inorganic–organic ZnIn2S4/Tp-Tta COF S-scheme heterostructure via an in situ synthesis method, forming a layered sandwich configuration that enhanced interfacial charge transfer and light utilization. The established S-scheme heterojunction exhibits a giant built-in electric field and diminished charge transfer resistance, which collectively enhance the separation and mobility of photogenerated carriers. This configuration preserves the strongest redox potentials of the electrons and holes, thereby meeting the kinetic demands for concurrent H2 evolution and FUR production. A superior and more stable photocatalytic redox performance is achieved compared to most reported photocatalysts, with a H2 production rate at 9730 µmol h−1g−1 and FUR generation at 12,100 µmol h−1g−1. In comparison, Z-scheme heterojunctions utilize a mediator, typically noble metal nanoparticles or a redox couple, to recombine electrons from two photosystems. This process spatially separates charge carriers with strong reduction and oxidation capabilities. Qu et al. [64] demonstrated that a 5% BiOI/Bi2WO6 Z-scheme photocatalyst achieved exceptional production rates of 23,000 and 21,221 µmol h−1g−1 for FUR acetalization and H2 evolution, respectively. The construction of the Z-scheme heterojunction facilitates efficient utilization of photoexcited carriers by coupling the H2 generation with the acetal reaction under visible light. The incorporation of BiOI plays a critical role in enabling efficient charge separation within the Z-scheme heterojunction. This process is synergistically enhanced by a built-in electric field that regulates the directional migration of photogenerated carriers across the interface. Although both S-scheme and Z-scheme heterojunctions achieve effective charge separation and preserve strong redox capabilities, their charge transfer mechanisms differ fundamentally. Z-scheme systems rely on specific charge recombination channels, whereas the S-scheme mechanism achieves spatial separation of superior carriers through direct interfacial charge recombination driven by the built-in electric field. This difference directly affects their charge separation kinetics, interfacial resistance, and ultimately the reaction pathway and product selectivity.

The core objective of the above strategies is to optimize the separation, migration, and utilization efficiency of photogenerated electron–hole pairs. These designs facilitate efficient charge separation and transport through well-defined heterointerfaces, increased specific surface area, optimized light harvesting, and spatially separated redox sites. The synergy between tailored interfacial engineering and energy band alignment in these heterostructures underscores their potential in driving simultaneous redox reactions under visible light efficiently and sustainably. Future research should focus more on utilizing in situ techniques to reveal the actual charge behavior at heterojunction interfaces and establish structure-activity relationships with target product selectivity.

4.1.3. Other Catalysts

Hollow nanocage structures are potentially promising for advanced energy storage and conversion applications, which can provide a large surface area, abundant active sites, and tunable electronic structures to enhance reactant adsorption and activation [76,77,78]. Tang et al. [68] fabricated the nanocage space structure by a surface in situ growth strategy, and the CdS-cage/1T-WS2 nanocage achieves an efficient H2 evolution efficiency (1116.8 µmol h−1), while the FUR selectivity and FOL conversion rate reach 91.1% and 85.5%, respectively. Specifically, the nanocage structure prolongs the thermo-electron lifetime required for the reduction reaction while accelerating the kinetics of the FOL oxidative dehydrogenation process by enhancing the heat-scattering process. Meanwhile, the nanocage space structure promotes the enhancement of interfacial interactions and the adsorption of reactants at the Cd sites.

The Zn1−xCdxS solid solution prepared by combining CdS with ZnS has an adjustable band structure by adjusting the Zn2+/Cd2+ ratio, which can simultaneously possess good visible light absorption characteristics and enhance the reforming ability of biomass-derived platform chemicals. Yang et al. [79] synthesized a series of NiMoS4/Zn0.6Cd0.4S nanocomposites via a facile two-pot hydrothermal strategy. This configuration enables the concurrent utilization of photo-induced charge carriers, facilitating their simultaneous participation in photocatalytic redox processes. The 10%-NiMoS4/Zn0.6Cd0.4S nanocomposite shows excellent adsorption capacity of FOL molecules, photoelectrochemical properties, and photogenerated electron–hole pair separation capability. An Ohmic junction is formed between Zn0.6Cd0.4S and NiMoS4, and a corresponding internal electric field could derive photoexcited electrons transport from Zn0.6Cd0.4S to NiMoS4.

The localized surface plasmon resonance effect induced by metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Cu, etc.) could give rise to the hot-carrier generation, localized field enhancement, and localized photothermal heating, showing promising applications in broadening the light absorption range, refining charge separation, and facilitating the adsorption and dissociation of reactive molecules. Liu et al. [69] strategically engineered a series-parallel photocatalyst (Cu NPs/CdS/In2O3) with intrinsic capability to regulate photogenerated carrier transfer. The LSPR from Cu NPs efficiently promotes proton reduction to H2, while simultaneously photogenerated holes on In2O3 selectively activate the α–C–H bond in FOL adsorbed at Lewis acid sites, enabling FUR production through a concerted mechanism.

In summary, the photocatalytic coupling oxidation of FOL with H2 evolution exemplifies atom economy and aligns with green chemistry principles. Nevertheless, its practical implementation faces challenges: the requisite efficient separation of photogenerated e− and h+ necessitates sophisticated catalyst architectures; the inherent competition from ambient oxygen scavenger protons derived from FOL oxidation and demands strictly anaerobic environments to preserve H2 evolution efficiency. These constraints underscore the need for advanced catalyst engineering and deeper mechanistic investigations.

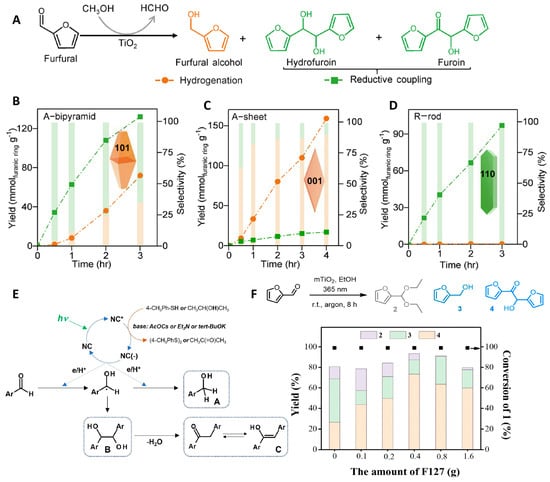

4.2. Photocatalytic C–C Coupling of FUR

Photocatalytic reductive coupling of FUR through C–C bond formation generates the long-chain products that function as precursors for high-energy-density fuels and valuable chemical intermediates [80,81,82,83]. For this aspect, Wu et al. [84] demonstrated the surface-dependent selectivity control using TiO2 nanocrystals, which effectively catalyze the photoreductive conversion of FUR to both corresponding alcohols and C–C coupled products under mild conditions (Figure 6A). This work represents a pioneering example of modulating product selectivity in the photocatalytic valorization of biomass-derived platform molecules, achieving high yields of coupling products. By adjusting the exposed crystal surface, the reaction can transition from aldehyde hydrogenation to C–C coupling, allowing for highly selective production of coupling products (Figure 6B–D). Surface oxygen vacancies are identified as critical determinants of product selectivity. The strong FUR adsorption on oxygen-vacancy-rich surfaces could promote the formation of a CH–O• intermediate, which readily undergoes hydrogenation to FOL. In contrast, surfaces lacking oxygen vacancies generate a weakly adsorbed •C-OH intermediate, whose facile desorption enables coupling to proceed.

The pursuit of environmentally benign photocatalytic materials has stimulated growing interest in cadmium-free multinary nanocrystals. Kowalik et al. [85] explored Ag-In-Zn-S quaternary nanocrystals for visible-light-mediated FUR reduction. In the presence of reducing agents and bases, this system achieved complete conversion and selectivity toward pinacol-coupled products. R nanocrystals with an energy gap of 2.0 eV exhibit a higher-lying valence band that facilitates ketyl radical formation. Combined with sufficiently high reductant concentration, this electronic structure promotes the two-step photoreduction of aldehydes to corresponding alcohols. In contrast, G nanocrystals possess a wider bandgap (Eg = 3.2 eV) and a substantially lowered valence band, which preferentially drives oxidation of the reducing agent, thereby lowering reductant concentration in the reaction mixture. Additionally, pronounced zinc enrichment on G nanocrystal surfaces further enhances pinacol yield by stabilizing ketyl radical intermediates and promoting their coupling. The proposed reaction pathway for photocatalytic aryl aldehyde reduction using Ag-In-Zn-S-alloyed nanocrystals (R and G) are illustrated in Figure 6E.

Figure 6.

(A) The structures of FUR aldehyde hydrogenation and reduction coupling products [84]; (B) the changes in product yield and selectivity with time over A-bipyramid [84]; (C) the changes in product yield and selectivity with time over the A-sheet [84]; (D) the changes in product yield and selectivity with time over R-rod [84]; (E) the proposed reaction pathway for the for photocatalytic aryl aldehyde reduction using Ag-In-Zn-S alloyed nanocrystals (R and G) [85]; (F) the photocatalytic performance of mesoporous TiO2 prepared with varying amounts of F127 as the template [86].

Surface engineering strategies have worked as effective methods to design photocatalysts. Gao et al. [86] established a photocatalytic process for the reductive coupling of FUR to deoxyfuroin using mesoporous TiO2 as the catalyst. The photocatalytic performance is shown in Figure 6F. The moderate redox capability and enhanced charge separation efficiency imparted by the well-defined mesoporous structure of mTiO2 significantly contribute to the high selectivity toward furoin formation during the photocatalytic conversion of FUR. Subsequent introduction of Cu species creates a hybrid system comprised of both dissolved and supported copper sites, which can achieve efficient photocatalytic dehydroxylation of furoin. This work expands the repertoire of surface engineering approaches for photocatalytic pinacol coupling of FUR and provides a direct synthetic pathway to deoxyfuroin from furoin.

Over the past decades, significant advances have been made in biomass valorization through C–C bond formation, particularly via aldehyde coupling strategies that yield higher molecular weight and energy-density compounds. Precise control over catalyst structure, electronic properties, and reaction conditions enables targeted synthesis of long-chain fuel precursors and chemical intermediates. Future research priorities focus more on systematic analysis of reaction mechanisms, development of sustainable catalyst systems, and rigorous assessment of industrial scalability to bridge the gap between laboratory demonstration and commercial implementation.

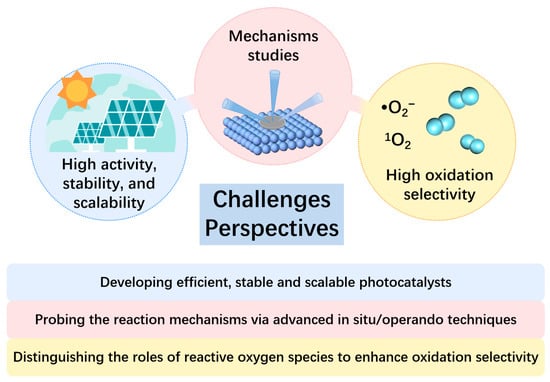

5. Challenges and Perspectives

In recent years, the photocatalytic conversion of biomass-derived FUR into high-value-added chemicals has attracted significant research attention. This review focuses on the transformation of FUR and FOL under various photocatalytic conditions, aiming to produce high-value-added products and green fuels. Each section elaborates on their reduction, oxidation and coupling, respectively. It provides a detailed introduction to the design and construction of photocatalytic systems and catalytic mechanisms. At this stage, the technology remains primarily focused on validating fundamental scientific principles. To achieve commercial success, further refinement and validation are essential to enable scaled-up production that meets industrial requirements. Despite considerable progress, numerous issues and critical challenges still need to be carefully addressed. Given the numerous advantages of photocatalytic technology, we systematically summarize the current developments and future research directions in the photocatalytic conversion of FUR (Figure 7). It is believed that this review will inspire more innovative ideas in the field.

Figure 7.

Challenges and recommended future research directions for the photocatalytic conversion of FUR.

Developing efficient, stable, and scalable photocatalysts: By optimizing the composition, structure, and surface properties of catalysts, light energy can be more effectively transformed into chemical energy. Materials should be engineered to have an optimal bandgap, customized surface chemistry, and a defined morphology. These properties collectively lead to enhanced light absorption, improved charge separation and transfer, superior catalytic activity, as well as redox capability. Beyond improving performance, rational catalyst design supports the development of cost-effective and industrially viable catalytic systems. An ideal photocatalyst should possess high durability with an operational lifespan exceeding one year, and allow straightforward recovery and reuse from reaction mixtures. The absence of unified testing procedures or consistent key performance indicators may lead to misleading comparisons and obstruct technological transfer. The economic viability of biomass processing is intrinsically linked to the photocatalytic FUR conversion scale. Enhancing conversion capacity within existing infrastructure is a pivotal strategy for improving market competitiveness. Thus, greater focus should be placed on evaluating photocatalysts under conditions representative of industrial reactor environments and increasing investment in the research of photocatalytic reactors to narrow the gap between lab-scale results and real-world applications. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are anticipated to play an expanding role in photocatalyst development. Integrating computational modeling with experimental validation will promote the optimization of catalyst structures and properties, accelerating the realization of high-performance photocatalytic systems.

Probing the reaction mechanisms via advanced in situ/operando techniques: Mechanistic investigation remains central to the advancement of novel photocatalysts. A synthesis of existing literature reveals several key insights: photogenerated electrons that are governed by the conduction band potential could drive reduction reactions, while holes in the valence band enable oxidation. Thus, precise control over band energetics is essential for selectively transforming furan-based compounds via photocatalysis. Such tuning can be realized through optimized synthesis, elemental doping, and the construction of heterojunctions. Additionally, phenomena such as surface plasmon resonance and ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) can extend photocatalytic activity into the visible-light region. To elucidate reaction pathways and structure–activity correlations—and to accelerate the rational design of high-performance catalysts—the adoption of advanced in situ characterization combined with theoretical modeling is recommended [87,88,89]. Advanced in situ characterization techniques can help elucidate the underlying mechanisms of FUR transformation: In situ Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopy allow real-time tracking of bond formation and cleavage on catalyst surfaces; in situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) reveals phase transitions under working conditions; in situ mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) aid in identifying intermediates and products dynamically; in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) provide insights into electron transfer and active site evolution; and in situ electron spin resonance (ESR) helps decipher reactant adsorption and radical-mediated steps. Together, these techniques furnish a multidimensional understanding of interfacial dynamics and active sites during FUR conversion, paving the way for the design of efficient and selective photocatalytic systems.

Distinguishing the roles of different reactive oxygen species (ROS) within oxidation systems to enhance oxidation selectivity: For instance, the hydroxyl radical (•OH), while a potent oxidant, often leads to non-selective over-oxidation of the substrate. Consequently, suppressing the generation of •OH is likely a viable strategy for enhancing product selectivity in oxidation processes. In contrast, the superoxide anion radical (•O2−) and singlet oxygen (1O2) are widely recognized as pivotal species for enabling highly selective photocatalytic oxidation reactions.

Overall, photocatalytic biomass conversion holds promising prospects. Continuous efforts are required to develop photocatalysts with higher selectivity and efficiency to achieve the upgrading conversion of FUR under mild reaction conditions. However, numerous challenges remain. This review offers a clearer developmental blueprint for the field from multiple dimensions, including catalyst design, reaction mechanisms, and practical applications. Finally, we anticipate that this work will further advance research on solar-driven catalytic conversion of FUR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and H.W.; formal analysis, S.W. and S.Y.; funding acquisition, H.W.; investigation, S.W.; methodology, S.W. and Z.Y.; project administration, H.W.; resources, H.W.; supervision, H.W.; validation, H.W.; visualization, S.Y.; writing—original draft, S.W. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China: No. 22178266.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FUR | furfural |

| FOL | furfuryl alcohol |

| GBL | γ-butyrolactone |

| GVL | γ-valerolactone |

| CPL | cyclopentanol |

| FA | furoic acid |

| 5-HFO | 5-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone |

| MA | maleic acid |

| MAN | maleic anhydride |

| AA | acrylic acid |

| HFO | hydrofuroin |

| FO | furoin |

| LA | levulinic acid |

| NP | nanoparticle |

| VB | valence band |

| CB | conduction band |

| Conv. | Conversion |

| Select. | Selectivity |

| LSPR | localized surface plasmon resonance |

| PECT | proton-coupled electron transfer |

| EMSI | electronic metal–support interaction |

| LMCT | ligand-to-metal charge transfer |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | machine learning |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| QE | quantum efficiency |

References

- Ya, Z.; Li, M.; Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.B. Asymmetric Atomic Pt-B Dual-Site Catalyst for Efficient Photoreforming of Waste Polylactic Acid Plastics in Seawater. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 16011–16023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Yang, Y.S.; Wang, S.; Li, X.L.; Feng, H.S.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, X.; Wei, M. Pt atomic clusters catalysts with local charge transfer towards selective oxidation of furfural. ACB-Environ. 2021, 295, 120290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Toda, H.; Tanaka, A.; Kominami, H. Bromine Substitution of Organic Modifiers Fixed on a Titanium(IV) Oxide Photocatalyst: A New Strategy Accelerating Visible Light-Induced Hydrogen-Free Hydrogenation of Furfural to Furfuryl Alcohol. Chemcatchem 2022, 14, e202101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.X.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Ma, X.B.; Yan, N. Photorefinery of Biomass and Plastics to Renewable Chemicals using Heterogeneous Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202408504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.S.; Zhang, S.D.; Li, K.N.; Yang, Q.; Wang, M.; Cai, D.; Tan, T.W.; Chen, B.Q. Furfuryl Alcohol Production with High Selectivity by a Novel Visible-Light Driven Biocatalysis Process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 15980–15988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, L.T.; Cséfalvay, E.; Németh, A. Catalytic Conversion of Carbohydrates to Initial Platform Chemicals: Chemistry and Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 505–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; De, S.; Saha, B.; Alam, M.I. Advances in conversion of hemicellulosic biomass to furfural and upgrading to biofuels. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 2025–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal, R.; Maireles-Torres, P.; Ojeda, M.; Sádaba, I.; López Granados, M. Furfural: A renewable and versatile platform molecule for the synthesis of chemicals and fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamman, A.S.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.C.; Hwang, I.T.; Park, N.J.; Hwang, Y.K.; Chang, J.S.; Hwang, J.S. Furfural: Hemicellulose/xylosederived biochemical. Biofuel Bioprod. Bior. 2008, 2, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozell, J.J.; Petersen, G.R. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates-the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.C.; Chai, J.; Tang, T.; Ding, L.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, J.J.; Chang, X.X.; Xu, B.J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.S.; et al. Manipulating hydrogenation pathways enables economically viable electrocatalytic aldehyde-to-alcohol valorization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2423542122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, A.; Singh, P.P.; Mondal, T. Furfural—A versatile, biomass-derived platform chemical for the production of renewable chemicals. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 510–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Peng, C. A review on renewable energy: Conversion and utilization of biomass. Smart Mol. 2024, 2, e20240019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gu, B.; Fang, W. Sunlight-driven photocatalytic conversion of furfural and its derivatives. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6261–6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, D. Photocatalysis: From Fundamental Principles to Materials and Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 6657–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, W.; Fan, Z.; Chen, Z. Recent Advances in Furfural Reduction via Electro-and Photocatalysis: From Mechanism to Catalyst Design. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 15263–15289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, G. State-of-the-Art Advancements in Photocatalytic Hydrogenation: Reaction Mechanism and Recent Progress in Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Catalysts. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Qin, L.; Yang, P.; Vlachos, D.G. Recent Advances in the Photocatalytic Conversion of Biomass-Derived Furanic Compounds. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 11336–11359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Lei, T.; Jiang, W.; Pang, H. Research progress on photocatalytic, electrocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 10739–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Paone, E.; Rodríguez-Padrón, D.; Luque, R.; Mauriello, F. Recent catalytic routes for the preparation and the upgrading of biomass derived furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4273–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ravi Anusuyadevi, P.; Aymonier, C.; Luque, R.; Marre, S. Nanostructured materials for photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Muñoz-Batista, M.J.; Fernández-García, M.; Luque, R.; Colmenares, J.C. Thermo-Photocatalysis: Environmental and Energy Applications. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2098–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; Zheng, Z. Plasmon-enhanced furfural hydrogenation catalyzed by stable carbon-coated copper nanoparticles driven from metal–organic frameworks. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 6483–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; He, Z.H.; Miao, R.Q.; Sun, Y.C.; Tian, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z.T. Photocatalytic reduction of biomass-derived aldehydes over Pt-loaded on NiIn bimetallic oxides under light-emitting diode lighting at mild conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 38, e7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Tanaka, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Kominami, H. Photocatalytic selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol over titanium(IV) oxide under metal-free and hydrogen-free conditions at room temperature. Chem. Lett. 2018, 47, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. Selective hydrogenation via cascade catalysis on amorphous TiO2. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 6585–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.C.; Sampaio, M.J.; Silva, C.G.; Faria, J.L. Selective Conversion of Furfural to Furfuryl Alcohol by Heterogeneous TiO2 Photocatalysis. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekasuwandumrong, O.; Richaroenkij, S.; Praserthdam, P.; Panpranot, J. Photocatalytic liquid-phase selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol without external hydrogen on graphene-modified TiO2 with different polymorphs. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F. Water promoted photocatalytic transfer hydrogenation of furfural to furfural alcohol over ultralow loading metal supported on TiO2. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 73, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Fu, C.; Zhang, W.; Gong, W.; Ma, J.; Ji, X.; Qian, L.; Feng, X.; Hu, C.; Long, R.; et al. Solar-driven production of renewable chemicals via biomass hydrogenation with green methanol. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Q.; Zhu, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhan, P.; Qi, Y.N.; Ren, W.Q.; Si, Z.H.; Cai, D.; Yu, S.S.; Qin, P.Y. Hierarchical ZnIn2S4 microspheres as photocatalyst for boosting the selective biohydrogenation of furfural into furfuryl alcohol under visible light irradiation. Green Chem. Eng. 2022, 3, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, C.; Shen, M.C.; Wu, T.K.; Wu, L. Surface functionalized Pt/SnNb2O6 nanosheets for visible-light-driven the precise hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 66, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, T.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Bi, J.; Wu, L. Photocatalytic precise hydrogenation of furfural over ultrathin Pt/NiMg-MOF-74 nanosheets: Synergistic effect of surface optimized NiII sites and Pt clusters. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 616, 156553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Z. Cu/Cu2O-MC (MC = Mesoporous Carbon) for Highly Efficient Hydrogenation of Furfural to Furfuryl Alcohol under Visible Light. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11458–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortright, R.D.; Davda, R.R.; Dumesic, J.A. Hydrogen from catalytic reforming of biomass-derived hydrocarbons in liquid water. Nature 2002, 418, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Yu, I.K.M.; Xiong, X.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Zhang, S.; Clark, J.H.; Hu, C.; Ng, Y.H.; Shang, J.; Ok, Y.S. Biorenewable hydrogen production through biomass gasification: A review and future prospects. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Li, J. Recent advances in the catalytic transfer hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol over heterogeneous catalysts. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 1780–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Mei, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, R.; Amal, R.; Yin, Z.; Zeng, Z. ZnIn2S4-Based Photocatalysts for Energy and Environmental Applications. Small Methods 2021, 5, 2100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; He, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Metal-Free Photocatalytic Hydrogenation Using Covalent Triazine Polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14378–14382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Long, J.; He, J.; Li, H. Alcohol-mediated Reduction of Biomass-derived Furanic Aldehydes via Catalytic Hydrogen Transfer. Curr. Org. Chem. 2019, 23, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, P.; Bo, D.; Chang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, T. Optimization of furfural production from D-xylose with formic acid as catalyst in a reactive extraction system. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 133, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namhaed, K.; Pérès, Y.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Triquet, T.; Camy, S.; Cognet, P. Integrated supercritical carbon dioxide extraction for efficient furfural production from xylose using formic acid as a catalyst. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 210, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Jia, W.; Si, Z.; Gao, H.; Tang, X.; Zeng, X.; Lei, T.; Liu, S.; et al. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation of biomass-derived furfural to furfuryl alcohol over in-situ prepared nano Cu-Pd/C catalyst using formic acid as hydrogen source. J. Catal. 2018, 368, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Nie, R.; Lyu, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, X. Selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol without external hydrogen over N-doped carbon confined Co catalysts. Fuel Process Technol. 2020, 197, 106205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, Z.; Tang, L.; Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. Photoreforming of waste plastic by B-doped carbon nitride nanotube: Atomic-level modulation and mechanism insights. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Ghalta, R.; Srivastava, R. Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid and Furfural to Fuel Additives over Ru-Decorated Carbon-Channelized Catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 3119–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, W. Ru/TiO2-photocatalysed synthesis of γ-butyrolactone from a furfural derivative under mild conditions. Fuel 2025, 405, 136437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalta, R.; Srivastava, R. Photocatalytic selective conversion of furfural to γ-butyrolactone through tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol intermediates over Pd NP decorated g-C3N4. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Bian, J.; Li, C. Enhancing photo-generated carriers transfer of K-C3N4/UiO-66-NH2 with Er doping for efficient photocatalytic oxidation of furfural to furoic acid. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2024, 52, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, Y.J.; Xia, H.A. Visible-light-driven photocatalytic oxidation of furfural to furoic acid over Ag/g-C3N4. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2025, 458, 115998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Ye, J.; Yu, T. Simultaneous value-added utilization of photogenerated electrons and holes on Pd/TiO2. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, P.; Pohlmann, B.; Scharf, H.D. The Photochemical Synthesis of Fine Chemicals with Sunlight. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 33, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Xu, G.; Fu, Y. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of furfural to C4 compounds with metal-TS-1 zeolite. ACB 2023, 340, 123220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.K.; Battula, V.R.; Giri, A.; Patra, A.; Kailasam, K. Photocatalytic valorization of furfural to value-added chemicals via mesoporous carbon nitride: A possibility through a metal-free pathway. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, S.; Hosseini-Sarvari, M.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, T. Photoswitchable Catalytic Aerobic Oxidation of Biomass-Based Furfural: A Selective Route for the Synthesis of 5-Hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone and Maleic Acid by Using the CdS/MOF Photocatalyst. IECR 2024, 63, 8933–8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Kim, J.E.; Je Kwon, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.; Choi, D.H.; Cho, K.Y.; Baek, K.-Y. Porphyrin-cored amphiphilic star block copolymer photocatalysts: Hydrophobic-layer effects on photooxidation. Mater. Lett. 2021, 311, 131577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, W.; Cao, X.; Xu, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, K.; Jiang, J.; Lu, G.-P. Single atom Cu anchored graphitic-C3N5 for photocatalytic selective oxidation of biomass-derived furfurals to maleic anhydride. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 23897–23909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, M.R.; Tavakolian, M.; Hosseini-Sarvari, M. From expired metformin drug to nanoporous N-doped-g-C3N4: Durable sunlight-responsive photocatalyst for oxidation of furfural to maleic acid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, J.G.H.; Jensma, A.; Feringa, B.L. Highly Efficient Biobased Synthesis of Acrylic Acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 61, e202112618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.-Y.; Xu, Y.-J. Photoredox-catalyzed biomass intermediate conversion integrated with H2 production over Ti3C2Tx/CdS composites. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Jin, Y.-H.; Burgess, R.A.; Dickenson, N.E.; Cao, X.-M.; Sun, Y. Visible-Light-Driven Valorization of Biomass Intermediates Integrated with H2 Production Catalyzed by Ultrathin Ni/CdS Nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15584–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Liu, S.; Tang, T.; Yao, S.; An, C. Visible-light driven H2 evolution coupled with furfuryl alcohol selective oxidation over Ru atom decorated Zn0.5Cd0.5S nanorods. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 2469–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, T.; Han, F.; Zheng, Z.; Xing, B.; Li, B. Bimetal-modified g-C3N4 photocatalyst for promoting hydrogen production coupled with selective oxidation of biomass derivative. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 897, 163177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]